Abstract

This paper examines how agents inscribed their persona in buildings during the Renaissance in Scania in present-day Sweden. Through an analysis of stone tablets and timber beams with inscriptions, images, and dates, questions of identity and individuality are highlighted. The objects were often placed above doors in noble country residences or in buildings belonging to the urban elite. The paper discusses who was able to see and understand the messages communicated by the buildings, and when, how, and why the tradition of putting up this type of object on buildings emerged in a Scandinavian context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

When walking along Adelgatan in Malmö, once the main street of the medieval town, one passes a two-storey brick building, called the “Rosenvinge House.” Above the entrance door to one of the two original apartments in the house there is a large sandstone tablet. On it one can read a text in German placed above two coats of arms, to the left of the Rosenvinge family, to the right that of the Liljefeldt family. Between the coats of arms is the monogram of Christ (IHS) within a laurel wreath. Below the monogram, the year 1534 dates the tablet (Fig. 1). In English translation the text reads; O, human, think of your fate, how God made you of out of dust, How Death sneaks, like the thief in the night, and takes both rich and poor.

About a hundred years later, the nobleman Palle Rosencrantz and his wife Lisbeth Lunge had a stone tablet put up at their manor, Högestad, in the countryside outside Ystad in southern Scania. The text on the tablet, in Danish, which was placed above the entrance door, reads in English translation: In the year 1635 Palle Rosenkrantz of Krenkerup and his wife Lisbet Lunge of Eskier had this house built, The Lord will preserve your entrance and exit. On the façade of the building, a two-storey stone building, we can also read the initials PRK, HR, ERS, and LL, as well as the year 1635, formed by iron anchors along the whole façade facing the courtyard. While the inscription mentions Palle’s present wife, Lisbeth Lunge (LL), the initials also reveal, at least to a viewer with personal knowledge of the individuals involved, the name of the owner’s two former wives, Hedvig Rantzau (HR) and Elisabeth Rosensparre (ER) (Kjellberg 1966c:120). The two stone tablets seem to have a lot in common, in that both date the building and reveal its owner, but their location is quite different. The tablet in Malmö was visible and readable to anyone passing on the town’s busiest street, while the other one was only readable and visible to those who went to visit Högestad.

The purpose of this paper is to discuss how agents inscribed their persona in buildings during the Renaissance in Scania in present-day Sweden. Until 1658 Scania was a central part of Denmark. Scanian noblemen and Scanian towns had important social, political, and economical roles in the Danish society. The transfer from Denmark to Sweden after the peace treaty in Roskilde in 1658 has been used to delimit the study in time. How and to which effect this transfer affected the Scanian society has been debated, but the transfer nevertheless meant that parts of the Danish nobility sold their estates in Scania to incoming Swedish noblemen, others stayed and became Swedish. The tradition of putting up texts and images in buildings did not end in 1658, but since later examples need to be studied in a somewhat different historic context, the year 1658 has in this case been used as an upper chronological limit. This also means that the material presented in this study needs to be understood in a Danish context. The paper will discuss who was able to see and understand the messages the buildings communicated; who understood this coded language? The focus will be on:

-

1.

stone tablets with coats of arms, dates, texts, and proverbs;

-

2.

timber beams from gateways and doors from urban buildings, with names, initials, personal marks, and proverbs; and

-

3.

iron anchors formed as letters creating initials and dates.

While the former type of stone tablet normally is found in residences, both urban and rural, connected to the nobility, the latter categories are more often found in buildings belonging to the urban elite. These type of inscriptions and images raise many questions. When, how and why did the tradition of putting up this type of object on buildings emerge? What type of messages did the inscriptions communicate and what kind of persons figured? In what languages were the texts written and what does this say about literacy and the intended audience? What was the meaning of inscribing your persona in a building? The paper focuses on secular buildings and does not discuss inscriptions in churches.

Research History

The concept of putting up inscriptions, images, and dates in buildings is well known from late medieval and Renaissance Europe, but it is a tradition that can be found already in antiquity. In the Roman world emperors and members of the elite erected different types of monuments with inscriptions and images to commemorate various gods, successful events, and themselves (Bruun and Edmondson 2015). After the decline of the Roman Empire inscriptions are associated with churches, where we occasionally can find this type of tablet (Wienberg 1993:164). Inscriptions on secular buildings, however, first start to emerge in the Middle Ages. The tradition of placing inscribed stones on secular buildings can, for example, be found in Germany, where some inscriptions were put up in the early fourteenth century, even if the tradition seems to have become more common in the fifteenth century. The inscriptions were placed above doors and openings, or under the roof. Inscriptions are found in many parts of present-day Germany, but also in Austria and the German-speaking parts of Switzerland. They seem to be less common in the Catholic parts than in the Protestant parts of Germany (Schaefer 1920; Widera 1990:12–14). In France examples date royal residences to the early sixteenth century (Ronnes and Westra 2011).

Studies of English castles have shown the presence of heraldic shields, especially at the gatehouses or entrances to castles and manor houses, dating from the late fourteenth century onward. They seem to become more common from the fifteenth century. Heraldry at the gatehouses or above entrances clarified the identity of the lord and was used to link together different monuments and places in the landscape (Johnson 2000:221, 2002:74; King 2003:117–118). In England, date stones, stones with a carved year, started to become widespread in the early sixteenth century, becoming much more common in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Sometimes the initials or names of the owner of the house supplemented the dates (Mytum 2007:385–394).

In Scandinavia the topic of inscriptions on buildings has so far not aroused any great scholarly interest. In Denmark, a comprehensive inventory of inscriptions in buildings is lacking. That this type of inscription was present in both urban environments and on manors in the countryside in the sixteenth century is well-known. Examples are known from many parts of Denmark, such as the town Odense and the manor Hesselagergård, both on Funen. When commented on, inscriptions have been viewed as reflecting the influence of Renaissance culture, as a way for the nobility and urban elite to inscribe their persona in history (Lorenzen 1921:88; Smed 2017; Troels-Lund 1903a:98–99, 1903b:63–70). The focus in Scandinavian research has rather been on the inscriptions from a linguistic point of view, and not so much on the context of where the inscriptions were found. When that has been the case, the emphasis has rather been on inscriptions on grave monuments (cf. Bӕksted 1968; Blennow 2016; Gardell 1945; Staecker 2003). Before the fifteenth century, coats of arms and inscriptions in Scandinavia are mainly found in a sacral context, on gravestones and painted on church walls (cf. Blennow 2016; Gardell 1945).

However, in Denmark there has been no attempt to treat this type of memorial in a comprehensive way. Earlier researchers have often noted and discussed the inscriptions, but inscribed tablets have been used as a way of dating buildings and acquiring knowledge of the persons behind the construction in the individual example (cf. Beckett 1897, 52–53; Lorenzen 1921; Troels-Lund 1903a:98–99, 1903b:63–70). The focus has been on the nobility. Less attention has been paid to inscriptions and images connected to burghers’ houses, even though, as will be shown, they are contemporary to noble inscriptions. The same research gap applies, and can be found in a European perspective, where scholars either have studied inscriptions in castles and country houses or in urban buildings, seldom analyzing them in a common context.

Research into memorials of different kinds is quite a large scholarly topic today. Memorials are seen either as a materialization of something successful, or as a reaction to a crisis, created to prevent or limit the consequences of a negative development (Frykman and Ehn 2007; Wienberg 2007). In Scandinavia, the most traditional topic concerning memorials is perhaps the study of runic stones from the Viking Age. Runic stones were raised to commemorate family members of different genders, as a way to immortalize heritage, but also as a way to commemorate various achievements, large building projects or long-distance travels. The runic stones were a way to mark the importance of the family affairs in periods of transition (Imer 2016; Sawyer 2002; Zachrisson 1998, 2002).

Theoretical Background

This article deals with classical problems of historical archaeology: how to combine text, images, and material culture in order to make an interpretation. The materials studied have the advantage that all three types of source material are present on the same type of object, the inscriptions and images on the tablet or beam are all on the building. There is thus no question of whether or not they should be seen in a joint context.

Connecting material culture to a specific agent is normally a problem; most of the archaeological record is anonymous and silent, even though we are well aware that it was made by people, individually or as members in a group. Even when we know the names of the persons who once lived at a specific site, we can seldom link individual objects to a specific person (Dobres and Robb 2000:11; Gilchrist 2009:388; Giles 2007; Knapp and van Dommelen 2008; Moreland 2001, 2006; Robb 2010). In this case, the connection between person and object is often obvious. The persons involved are mentioned on the object of study. This raises the question of how and when a more modern form of individuality was born.

Individuality has traditionally been seen as a consequence of the fifteenth-century Renaissance in Italy, ever since Jacob Burckhardt's (1995) study of the subject was first published in the mid-twentieth century. Burckhardt argued that during the Renaissance humans became aware of themselves as objects, partly as a consequence of the rediscovery of antiquity. The individual was now seen as an independent, creative, and acting subject separated from the Creation. Although the perspectives have broadened since Burckhardt's study, the Renaissance is still regarded as an important period in the development toward a modern form of individualism (Johnson 2000: 215; Olin 2005: 428). An awareness arose within the educated classes that within each individual there was an individuality that he/she would strive to realize, in actions, in art, and in poetry (Johannesson 1996:10).

Autobiographies, personalized grave slabs, and portraits are evidence of this development (Burckhardt 1995; Burke 1998; Hansson 2010; Johnson 2000:215). The tradition of putting up memorial tablets on buildings fits this trend. In the same way, the text and images in burghers’ houses can be seen as a reflection of the growth in the social and economic importance of the urban bourgeoisie (Thomasson 1997, 2004). In the social competition between nobility and merchants, buildings and their messages were tools.

The topic also raises other questions; one is the problem of visuality, another the emergence of literacy. Visuality often concerns a situation when someone views a space of some sort. This space can be more or less empty or filled with a combination of objects, ranging from large landscapes to single objects, objects that – as is the case in this article – are filled with images and/or texts. How the individual perceives, interprets, and understands what he or she sees, depends on personal factors such as age, gender, social status, and level of education (Biernoff 2002; Camille 2000; Foster 1988; Frieman and Gillings 2007; Giles 2007; Graves 2007). In addition, factors connected to the moment when the observation is made, whether it is made in solitude or together with others and in what circumstances it is made (during day/night [light conditions], during a ritual, etc.) affect the perception. Much of the research on visuality has so far focused on the intentions of the sender of the message in question, while fewer studies have been done regarding for whom the images in question were intended (cf. Giles 2007: 117; Hansson 2010; 2016; Richardson 2003:150–151). When the objects in question also contain text, questions of literacy arise.

Writing is a technology efficient not only in the production and transformation of social relations; it has also been argued that it changes the way we think. The implication of this is that the context where written messages turn up is important (Andrén 1997:152–153, 158–161; Goody 1986; Moreland 2001:85, 2006:140–141; Ong 1986, 2002). How and where texts were created, found, and used was part of the process of decoding the messages.

How large a proportion of the population could both read and write during the Late Middle Ages in different parts of Europe is not known. Literacy is generally seen as being connected to the religious and secular elite. Several scholars point to the importance of the invention of the printing press in the fifteenth century, as well as the Reformation and its emphasis on individual studies of the Holy Bible, as important factors in the spread of literacy in Europe (Harasimovicz 2011; Houston 1988:155–158; Moreland 2001:54–58). Medieval texts were for a long time mainly written in Latin, texts in vernacular languages only started to appear in the late Middle Ages (Blennow 2016; Houston 1988:130–140). For Scandinavia it is likely that most people belonging to the aristocracy were literate in the sixteenth century. We must also assume that members of the bourgeoisie also could read and write to manage their businesses. It is also more likely that a larger group of people in the population could read, rather than write texts themselves (Söderberg 2010:16–17).

In the context of this article it is thus interesting to note where stone tablets with inscriptions were placed (who was likely to have the possibility to view them?), and in what language the texts were written (who was able to understand them?). The coat of arms of the lord, or the owner’s mark of the merchant, placed on the gatehouse, of the castle, or above another type of entrance on a building, functioned as a type of liminal zone of a specific individual, marking the presence of that person, whether or not he or she was present. Supplemented with texts, the tablet both transmitted and stored information in a liminal position. At the same time as the tablet stored and communicated information, it also lost information once the audience started to forget all the details about the persons involved (Heck 2002:18, 22–23). The inscriptions and images were thus statements and had a form of secondary agency since, when decoded, their messages could lead to specific actions and behavior (Gell 1998:16–17, 22).

Material

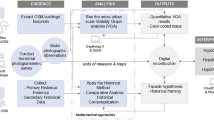

The study has been undertaken as an inventory of secular inscriptions in buildings dating from before 1658 in Scania. All inscriptions have been mentioned in older scholarly and topographic literature, held by museums, and still sitting in preserved buildings. Most of the latter have been visited (Fig. 2). All the examples found have been entered into a database.

Scania is situated in the southernmost part of Sweden. The map shows the location of the entries in the database. Numbers in the circles shows the number of entries on each site. Dots without numbers represent individual objects on a site. Numbers in black rectangles are entries in towns. Map M. Hansson

The material can be divided into different categories in terms of source criticism. The highest value is assigned to tablets which are still preserved in standing buildings and in their original position. Second come those still present in buildings, but where it is obvious that they have been moved. A third group are those in museum collections, sometimes with rather good information on where these objects once were situated in the buildings. The fourth group consists of tablets known only from older written descriptions/images. Here, both the content of the text/images and the spatial context of the tablets are often difficult to evaluate. It should also be noted that graffiti-style inscriptions have been excluded. Graffiti can be seen as something personal and spontaneous, made on the spur of the moment, whereas tablets with texts and images in buildings, the topic of this article, are the result of planned actions (Champion 2015; Kraack 1997:12).

The database consists of 153 entries, objects with inscriptions, dates, coat of arms, or owner’s marks and initials. Sometimes these categories are combined where we find an inscription with a name and a date, as well as initials in the form of anchors, on the same building. In other cases, it is a stone with only a coat of arms, or just a date. Most of the entries in the database are from manors in the countryside (93), the rest from towns (60). Of the urban examples, 70% come from the largest town, Malmö (Table 1). This probably reflects the relative economic and social importance of Scanian towns in the early modern period, but it is also a reflection of the state of preservation.

Of all 153 objects, a large majority (125) were/are originally outside the buildings, on the facades, or facing streets or courtyards. This was equally common in the countryside and in urban areas. There seems, however, to be a difference between the countryside and towns when it comes to interior tablets or entries. Of the 30 objects that are known to have been placed inside buildings, only four come from urban houses. Interior inscriptions are mainly to be found on the mantelpiece of fireplaces or above a doorway, and can consist of a short text, and/or names and/or coats of arms of the persons involved.

The material, of course, lacks representativity. Preserved secular buildings dated before 1658 are quite rare in Scania, and those that exist are dominated by noble manor houses situated in the countryside. From towns the number of preserved buildings is small, and many houses have been demolished without proper documentation. We can be fairly certain that the tradition of putting up this type of inscription was more widespread in the towns than this compilation shows. Of the objects known from Malmö, only a few are still in their original position in preserved buildings. Thanks to the documentation of the local historian Einar Bager (1971), it is sometimes possible to determine the town plot location of objects that are missing today, even if we sometimes lack information on where in the building the inscription was placed.

That the material from noble houses is overrepresented, and that urban inscriptions were probably much more common and widespread, is a safe assumption. It should be noted, however, that no examples dating from before 1658 have been found from peasant farms in the countryside. Considering that preserved buildings from before 1658 are very rare in Scania, this might not be so strange. However, older topographical literature does not mention this type of inscription from ordinary peasant milieus, farms in hamlets, and villages. The current state of knowledge suggests that the tradition of putting up inscriptions on buildings seems to be connected to either urban milieus or manor houses and not to the peasantry.

The materiality of the inscriptions varies from different types of stone material, timber, and iron anchors formed as letters or Arabic numerals. The latter thus create initials of owners and dates. No geological identification of the type of stone in the tablet has been undertaken, but judging by previous information it seems as if sandstone is the predominant material. Other stone types used are limestone and chalk. In many cases the type of stone used is not known with certainty.

Chronology

The 125 objects that can be dated by an exact date, or indirectly by the context of the inscription, shows that this tradition in Scania seems to have started at the end of the fifteenth century. Two stone tablets from Glimmingehus castle are the oldest. Here, two inscriptions are dated before 1500, one above the entrance to the castle (1499), the other on a probable garden table, today in a secondary position (1487) (Hansson 2016). Otherwise, inscriptions started to be inserted in buildings in the first quarter of the sixteenth century. During the sixteenth century, it seems as if the tradition was shared by members of the nobility and members of the urban elite. In this respect the nobility does not seem to be a forerunner that urban lay people later followed. On the contrary, if one dares to use the scarce material to draw any conclusions, it seems as if the trend was as strong in towns in the early sixteenth century. It was not until the first quarter of the seventeenth century, when the tradition seems to have exploded in popularity within the nobility, that they overtook the towns in the number of inscriptions (Fig. 3). Most of these noble inscriptions are to be found in manors in the countryside. The late sixteenth and early seventeenth century was a prosperous time for the Scanian nobility. The rising price of grain, the base for the economy of the nobility, led to expanded exports and increased wealth, which was invested in large-scale building projects (Jespersen 2001:372–373).

The castle Glimmingehus in Scania is one of the oldest buildings in Denmark dated by an inscription (1499). At the manor of Palsgård, in Jutland, a date stone that today is missing is said to have borne the year 1412. This has been used to date the construction of the manor, but the buildings are probably much younger, and therefore the existence of this early date stone has been cast in doubt (Hansen 1992:11–12). In present-day Denmark the town hall in Ribe, built in 1496, held two short inscriptions of a religious type, “Christus Vincit” and “Christus Regnat” (Christ conquers/Christ rules). A similar inscription is also found on a beam from a porch in Ribe, with the date 1529. This is the oldest timber-framed house in present-day Denmark dated by an inscription (Atzbach 2017:357). From Malmö, the earliest known date stones/beams date buildings to 1519, 1520, and 1525. In Germany there are examples of dated buildings as early as the fourteenth century, 1323 in Dambach and 1328 in Boersch (Schaefer 1920:10). This chronological distribution of the Scanian material fits rather well with what has been seen elsewhere in Europe. It is contemporary with much of the English and French material, but perhaps a bit later than the German. It also seems to connect to what is known from other parts of Denmark. Houses dated by inscriptions in Scania are thus part of a general European trend.

Texts

Beside the date, many of the stone tablets and dated door and porch beams, also bore inscriptions or proverbs of different types. While the noble inscriptions on stone tablets could be rather long, the ones connected to the bourgeoisie were shorter, showing the initials of the owners, husband and wife, and sometimes a religious proverb or a quotation from the Bible. Fifty-one of the stone tablets and timber beams have a longer text of some kind inscribed, not just initials and dates. Of the longer texts, 28 are written in Danish, 14 in Latin, nine in German and one in French. Danish is, as can be expected, the most common language, followed by Latin (Table 2). The third most common language is German, and it is interesting to note that German inscriptions were most common in an urban context. Only one text in German can be found in the countryside, where there is a clear dominance of Danish. A tentative interpretation could be that the Scanian nobility preferred to communicate in Danish, perhaps since this was the language they mastered best. In the towns, merchants and artisans were equally comfortable communicating in Danish or German. The slight dominance for German is probably a reflection of the long tradition of German trading contacts and the presence of German merchants in the late medieval towns.

In a study of sixteenth-century Danish graveslabs, Jörn Staecker (2003) has shown that there was a significant shift, from Latin to the vernacular, Danish, as the preferred language. While graveslabs over clerics were written in Latin throughout the sixteenth century, graveslabs over noblemen and burghers are mostly in Danish from the 1520s onward.

Most Latin inscriptions in buildings are short, indicating the date (Anno Domini), or of religious character (KRS Imperator). Longer Latin inscriptions are connected to the noblemen Sivert Grubbe and Tycho Brahe. Both these individuals were Renaissance intellectuals in the true sense in the late sixteenth/early seventeenth centuries. While Grubbe put up long inscriptions in Latin on his castles Torup and Hovdala, Brahe filled his now destroyed palace/observatory Uranienborg and Stjärneborg on the island of Ven in the Öresund Strait with a large number of inscriptions. Apart from some fragments and one stone that has been moved to the mainland, most of this material is long gone (Bergman 1934; Hansson 2019; Jern 1976:18, 61; Vellev 2017). Already in the late sixteenth century, Latin was a language mainly used by an intellectual elite.

When it comes to the messages of the texts, the inscriptions can be divided into different categories according to their meaning and message, what they actually say. Here the inscriptions have been divided into five categories (Table 3).

-

1.

Construction work

-

2.

Religious texts

-

3.

Events

-

4.

Family/inheritance

-

5.

Proverbs of wisdom.

The divisions between the categories are not sharp, as many texts belong to more than one category. Most common are religious messages concerning how the house should be protected by Christ. Others were made to celebrate Him. Thirty texts with a religious meaning can be found. One example from Ystad, written in Danish, states that “In 1575, on the 2nd of April, Lavrens Goldsmith built this house. Christ preserve it from fire and violence” (Sandblad 1949:394, 406; translation by author).

This type of religious messages can be compared with the prayers that were said when a church or monastery was inaugurated. The religious messages probably had an apotropaic function, protecting both the building and its inhabitants. A similar function was served by religious images and symbols. Some of the religious texts were also quotations from the Bible. One example is the text about the Lord preserving someone’s entrance and exit, used in Högestad and mentioned in the introduction, which comes from the Psalter (Pernler 2014).

The second most common type of message in the inscriptions deals with construction work. Twenty-four examples of someone taking credit for having had something built, or rebuilt, can be found. This message is present in inscriptions made by both nobles and burghers. It is interesting to see that inscriptions of this type were almost all written in Danish, the vernacular language. Of literate people in Scania, most were probably able to read Danish, and this was a type of message that the sender really wanted a large audience to understand.

Apart from construction work or religious messages, other texts mention what can be said concerning a family business or to commemorate special events connected to family history. Others are more to be seen as presenting “proverbs of wisdom.” The latter are often long texts in Latin, like that of the previously mentioned Sivert Grubbe. One inscription from 1632 sitting above the entrance to his residence Torup east of Malmö, tells a long story of how he remodeled the castle and tried to the best of his ability to administer the inheritance from his forefathers. He also reflects on who will take over the estate when he is gone. When the text was set up, all his children were dead, and his only heir was an infant granddaughter (Hansson 2019).

Events that are mentioned are, for example, a failed Swedish attack on Hovdala castle in 1612. Sivert Grubbe put up a commemorative text in 1633, more than 20 years after the event took place (Olsson 1922a:31–32). The attack is described in a long inscription in Latin, sitting on two different stone tablets on the inside of the great gate tower. The text is only visible from the courtyard, after a visitor has passed through the gateway of the tower and turned back to admire the gate tower. From the outside, when entering, a visitor could see another text, also in Latin, above the gateway. This text mentions how one should not be a fool longing for immortality. It is undated and placed below the coat of arms of Sivert Grubbe and his mother Else Laxmand, who died in 1575.

The tower was probably built ca. 1600, which has been shown both by dendrochronology and by the numbers displayed by the anchors on the tower (Hansson 2019:45).This means that Sivert Grubbe thought that his mother and her family were still so important that he wanted to make their relationship visible to visitors 25 years after her death. It is interesting to note the contradiction of the message of the text on the outside of the tower, “you should not long for immortality,” and the way in which Grubbe acted. By putting up these tablets he actually tried to ensure his own immortality.

Many of the German inscriptions in urban contexts are varieties of proverbs well-known at the time. Collections of proverbs began to be printed in the sixteenth century, in Latin or a vernacular language. The Proverbia of Peder Laales contained some 1,200 medieval proverbs in Latin, with a Danish translation. It was first printed in 1506 and was used as a schoolbook in Latin (Brugge 1951; Hansen 1991). This and other printed collections seem to have functioned as role models for artists and carpenters when creating texts on beams and tablets. For example, an inscription on a beam from the house of Hans Sukkerbager in Malmö, dated 1581 bears a common proverb also found on buildings in Germany (Fig. 4) (Brugge 1951:57, 60).

The timber beam from the house of “Hans Sukkerbager” in Malmö, 1581 with the inscription WER GODT WERTRAWET DER HAT WOL GEBAWET HEBBE GODT VOR OGEN IN ALLEN DINGEN SO WERT IDT DI NVMMER MISGELINGEN (He who trust in God, has built well. Keep God for your eyes and you shall not fail; translation by author). After Bager 1971:352

Longer inscriptions are almost exclusively to be found on the façade of buildings, often at an entrance, above either a door or a gateway into a courtyard of some sort. Interior inscriptions were much shorter, often had a religious focus, and were not explicit when it came to telling stories of building projects. They were often placed on the mantelpiece (Bager 1971:316–317). The audience for these interior messages must have been the immediate family and friends within the social circle where the instigator of the inscription mixed.

Images

The inscriptions are often accompanied by different types of images. On the stone tablets it is often, apart from the coat of arms of the persons involved, different types of floral ornaments and arcades and pillars that frame the composition. The coat of arms, the text, and the year are the most important features. Other elements can be branches of trees and even skulls. More elaborate stone tablets are clearly made in the classicizing style of the Renaissance.

One motif that seems to have been popular, especially in the mid and late sixteenth century, was the Holy Trinity, an ageing, enthroned God holding the Son on the cross, with a dove above his right shoulder (Fig. 5). This motif can be found in the central parts of the stone tablets of the castles of Vittskövle (1553), Skarhult (1562), and Bjersjöholm (1576). The Trinity motifs from Vittskövle and Bjersjöholm have striking similarities despite the chronological difference between them, which emphasizes the timelessness of this motif. Just like similar motifs, such as the Arma Christi, the wounds of Christ, which can be found above entrances in Scottish castles, this type of religious motifs can be interpreted as having an apotropaic meaning, giving divine protection to the persons entering the building (Dransart 2015; Pernler 2014).

Imaginative motifs, apart from carved flowers, are less common on timber beams with inscriptions. Beside lines framing the text, the decoration normally consists of geometrical figures. In some cases the owner’s marks on the timber beams are set within a frame, sometimes a circle or some lines, but in many cases they are definitely framed by a shield, to imitate the typical noble coat of arms. Just as the coat of arms of the nobility was specific for the individual noble family, there are, at least within the urban elite in Malmö, specific marks used by families for generations (Bager 1937). Anders Reisnert (2008:631) has highlighted how the urban elite, especially the members of the town councils in towns in north Germany, often had noble-style coats of arms.

One example is from the beam above the gateway of a house in Södergatan in Malmö. Here, the mayor of Malmö, Rasmus Ludvigsson and his wife, had their marks made in 1597 inside a shield on a beam with a text that explained that humans always should think of their distress, for tomorrow they will be dead, a somewhat similar message to the “momento mori” theme that could be found on the Rosenvinge house (Bager 1971:352). The use of the shield was probably an attempt by the instigators to distinguish themselves within the group of leading figures in the town council; appropriating the “shield” was perhaps an attempt to equate themselves with the nobility (Hansen 2020).

Another type of decoration interesting in this context can be seen when parts of a noble family’s coat of arms were incorporated on a building’s façade. For those familiar with heraldry this was a way of manifesting status and ownership of a building even from a distance. In Scania this phenomenon is known from two manors in the countryside, Krapperup in the northwest and Karsholm in the northeast. In both cases, it concerns the Gyllenstierna family. Their coat of arms consists of a seven-pointed star, and at Krapperup one can see how white seven-pointed stars, made of chalk, were added secondarily to the western façade and southern and northern gables of the main brick building of the castle. Forty-two stars are visible on the western facade, at least six on the southern, and 15 on the northern gable (Fig. 6). The stars are placed regularly on all the facades facing outward, to the adjacent park and garden.

The present main building of the castle, with the stars in the façade, was built in the last quarter of the sixteenth century, replacing an earlier medieval castle (Carelli 2003:146–147; Ranby 2003). The Gyllenstierna family gained control of Krapperup at the beginning of the seventeenth century when Henrik Gyllenstierna married Lisbeth Podebusk. At Karsholm, white stars surrounded the windows when the castle was completed in the 1620s by the same Henrik Gyllenstierna (Olsson 1922b:187). The stars on the façade were a visible materialization of the changed ownership.

The Individuals Behind

The examples of Krapperup and Karsholm show the close connection between agents and this type of material culture. The agents come from one of two groups, either the nobility or the urban elite. The connection between the tablets and the urban elite is evident if we look at the distribution of the locations in the town of buildings with this type of messages. In Malmö, most messages can be found in buildings along the main street, Adelgatan, running east to west along the shore (Fig. 7). Especially many examples can be found in the area close to the medieval square and the town church. Södergatan, running from south to north from the southern town gate to the sixteenth-century square, was lined with buildings with many inscriptions. These were the two main streets in Malmö, where the most prosperous town members had their houses judging by sixteenth-century tax registers (Rosborg 2016:329). The inscriptions on the buildings underlined this social topography of the town.

If we look at the noble families mentioned in Scanian inscriptions, we may note that 44 different Danish noble families are present on these tablets, either by name, or by their coats of arms. While the former is directly linked to a single individual, the coat of arms is a way to present the whole family. Of these noble families, 16 are present only once, on a single tablet, another 12 families are present twice. This means that 28 of 44 families are only presented once or twice.

Seven noble families are present at least five times, and yet another five families are present on ten occasions or more. The Ulfstand family has most appearances, 15, followed by the Gyllenstierna and Thott families with 12 each, and the Brahe and Rosencrantz families with 11.

That the noble families which occur most often belong to the upper echelon of the aristocracy is of course not a surprise. They all belonged to the elite of the Scanian nobility in the middle of the seventeenth century (Ullgren 2004: 94, 99). They were the ones with most economic resources, involved in many large building projects, which gave them the opportunity to manifest themselves.

It seems as if the tradition of putting up this type of memorial concerned the whole nobility. There were also families connected to the lesser nobility who put up memorials. One example was the Rosenvinge house in Malmö, mentioned at the beginning. If we consider the fact that 44 different families are represented in the material, and compare that to the 53 noble families that existed Scania in 1652 (Ullgren 2004:67), it might seem as if most noble families took part in this tradition. Setting up an inscription on your house was part of the noble way of life.

Looking at how the connections between different families emerge on the tablets, one can see that the upper echelon of the aristocracy often mixed with each other. The Thott family was connected to the Gyllenstierna family on four occasions, to the Rosencrantz family on three occasions. The Scanian elite families intermarried (Ullgren 2004:99). They used the buildings to show their network of important connections. Examples where someone from the high aristocracy manifested a connection to someone from the lower strands of the nobility are rare. One might perhaps say that the tablets were used to create and demarcate a group identity within the elite nobility.

Some examples also show that it is not only the married couple that is presented; in several cases more than one generation of the family lines is presented. When Otte Brahe in 1551 had a tablet put up at his manor Knutstorp, the text not only commemorated his efforts and those of his wife, Beate Bille, as builders. It also mentioned that Beate was the daughter of Claus Bille of Lyngsgård (Hahr 1922:10; Kjellberg 1966a:143–144). The Bille family was one of the most prominent Danish noble families at this time, and Claus Bille, Otte’s father-in-law, was one of the richest men in Denmark. His cousin Jens Brahe had a similar text placed on his castle Vittskövle in 1553. This tablet states that Jens and his wife Anna Bille had the castle built, and that the estate had come into the possession of the Brahe family after Jens’s father had bought it from the king. The text ends by stating that the castle should never leave the Brahe family (Hahr 1922:10, 18–19; Kjellberg 1966b:267–268). Their right to own Vittskövle was immortalized above the entrance to the castle and the legality of their possession, by purchase, was underlined.

The use of the status of previous generations and of a dead partner is not as apparent within the urban elite. One example to be mentioned is from Lauritz Hatmaker’s house in Malmö. The stone tablet on the house is badly preserved, and today not in its original place, but it once sat above the entrance to the house. On the tablet, a lion is holding a small shield with a deer. Below the figure a timber beam with the year 1531 (in Latin) and two owners’ marks are seen, one with the initials D A. The latter have been identified as belonging to David Albritsen, a prominent merchant in Malmö, who owned the plot in 1543. The other mark is probably connected to his wife Karine. She had previously been married to Lauritz Hatmaker, and probably continued to use his mark after his death, in 1527 or 1528. In 1530, the property left by Lauritz was divided between his widow and their three children. The document states that Karine had had a house built with money that was left for the children. Karine continued to use her dead husband’s mark even after she had remarried (Bager 1955; Reisnert 1999:65–66).

In an urban context, we can see that some individuals had their full name written, but mostly they are only identified by their initials and/or owner’s mark. One of the former is “Hans Sukkerbager” (baker) (Fig. 4). From other sources Hans is known as mayor of Malmö (Bager 1971:322). This is also one of very few instances when a profession is actually mentioned in the text. Even though their profession/status is not directly mentioned in the inscription, the social position of the individuals involved was probably well known to the contemporary society. A contemporary reader/viewer could probably decode who the persons behind the initials and owner’s marks were.

This mix of nobility and bourgeoisie is clearly expressed in the building complex of Jørgen Kock, built in brick in Malmö around 1525. This is the best-preserved urban residence from the sixteenth century in Scania and thus can cast some light on how coat of arms and other decorations was placed in detail in a residence of the urban elite. In this building, both the owner’s mark, and the coat of arms of the builder, Jörgen Kock, are present. The same applies to the coat of arms of Kock’s wife Citze Kortsdatters (van Nuland). Coat of arms and owner’s marks can be found both inside and outside the building. Kock was ennobled in 1526, and then received a coat of arms. His wife Citze already had her own coat of arms, belonging to a noble family. A recent analysis of the building shows that Kock used different types of personal markings in different parts of his building complex. Once ennobled, he did not erase his old owner’s marks and had them replaced by his new personal symbol. His two different personal insignias were rather used contemporaneously. In the parts of the building where his owner’s mark was visible, he signalled his position as mayor and leading merchant of Malmö. In other parts of the building with his noble coat of arms, he showed himself as nobleman (Hansen 2020:161–164).

A recent study by Kenth Hansen (2020), concerning the urban elite in medieval Scanian towns has shown how the urban elite annexed noble insignia and titles, for use in different social contexts. The dividing line between burgher and nobleman thus sometimes ran within a single individual which the example of Jörgen Kock shows. The burgher’s use of the shield form for their owner’s marks is a similar way of trying to bridge a social divide.

Gender

Recently, inscriptions have been used to discuss the role of noble women as builders in sixteenth-century Denmark (Smed 2017). Noble women were responsible for a considerable number of major transformations and newly erected manors in Denmark in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Women acted as builders, as widows, and when their husbands, for example, were imprisoned. Both men and women are present on the tablets and beams in Scania. Some are mentioned by name, others are represented by their initials or coats of arms. Most often women are presented as wives, as a form of appendix to the husband who is manifested as the active instigator. Sometimes the women mentioned are dead, as shown by the example in the introduction of Högestad, with the initials of Palle Rosencrantz’s dead wives. The best-known of this type of category of “dead wives” is perhaps the example from Glimmingehus, where Jens Holgersson Ulfstand, on a tablet dated 1499, is presented standing in full figure between his current wife Margareta Trolle and his dead wife Holgerd Brahe (Hansson 2016). The emphasis on the dead wives underlines the women’s role in creating a social network for the nobility (Fig. 8). For Jens Holgersson, his first wife from the Brahe family, from the nearby castle of Tosterup close to Glimmingehus, was still important in maintaining his social network, despite the fact that she had been dead for several years when the castle at Glimmingehus was built (Wallin 1979:21).

Noble women were thus important for creating and maintaining the social network of the aristocracy. Sometimes they also had a more active role, instigating or finalizing building projects. One of the most prominent female builders was Görvel Fadersdotter Sparre who, according to a now missing inscription from Torup, is said to have laid the foundation stone of the castle. She was most probably also responsible for the construction of the “Borgska Huset” in Lund, part of her urban residence, even though this is not commemorated by an inscription (Hahr 1922:47; Johansson 1985). Another example is the Rosenvinge house mentioned in the introduction, which was probably built by Anne Pedersdotter Liljefeldt. In 1534, the date on the tablet, she was a widow, which also is symbolized by the dead branches of a tree placed on the tablet. A dead tree without leaves symbolizes death (Hansen 2020:170). The example of Anne Pedersdotter Liljefeldt shows that female builders were probably more active than the tablets suggest. The role of the women as builders is clearly underestimated. To what extent they actually led construction work in the absence of the male is hard to determine. That the manor of Svenstorp was built by Beate Hvitfeldt in 1596, widow of Knut Ulfeldt, is stated explicitly on the stone tablet over the elaborate doorway (Kjellberg 1966a:263).

In contrast to noble women, burgher women are more anonymous. There is no clear example of them being an active partner in a building project in the same way as can be seen for noble women. Just like their husbands, they are most often represented by their initials or their owner’s mark. Nevertheless, as the example of Lauritz Hatmaker’s houses showed (above), rich urban widows also had the opportunity to act as builders. However, they do not seem to have been as explicit about their achievements as noble widows.

Conclusion

Even if the presented material in some parts has problems with representativity, some tentative conclusions can be drawn. It seems apparent that the tradition of putting up this type of messages on buildings is connected to topics such as religion, identity, social status, and self-esteem. By putting up one’s name, coat of arms, or owner’s mark, the individual became eternally present in a liminal, transitional zone at an opening of some sort. The building became a part of the person, and the person became represented by the building. More or less explicitly, the texts and images commemorate an individual and his/her achievements for posterity, achievements that simultaneously were made in order to please the Lord. In this respect, comparisons to Viking Age runic stones, which often had Christian prayers and in a similarly way heralded the efforts of individuals, can be made. Perhaps the tablets were just a new way of continuing an old tradition?

Religious messages are manifold and often combined with other statements. Sometimes text and images functioned as a kind of divine insurance against misfortune and showed the individuals as devout Christians. Quotations from the Bible have often been interpreted, as mentioned before, as an example of the influence of the Reformation, with its general emphasis on the Bible as the holy role model. This might be true, even if an explicit connection to the Reformation is hard to see in this material. The idea of combining religious texts with other images and messages was also present on runic stones many centuries earlier. Here, the Christian formulae acted as some manner of divine insurance, and promoted the instigator as a Christian as early as the eleventh century. In this respect the sixteenth-century inscriptions connect to old traditions.

The tradition of putting up inscriptions on your house was also connected to the top strata in society, the nobility and the urban elite. It was a way of distancing the elite from people of lower rank, materializing their status, and making it indisputable. The higher aristocracy showed their network by adding the armorial bearings of living and dead ancestors, and distinguished families, socially and economically, showed their intimate relationships with each other on the buildings. In some ways, this can also be compared to runic inscriptions commemorating several generations of the same family (Zachrisson 2002).

However, a comparison between the nobility and the bourgeoisie shows differences regarding the accessibility of the messages. While bourgeois relations and identities were explicitly stated in the urban center, the nobility sent messages, with some exceptions, only at their manorial center. To be able to read and visualize the tablets on the residence, the audience had to come close, into the courtyard, close to the house, and sometimes also inside. These were not messages visible to those passing by, only to invited guests and family members. Aristocratic messages were thus rather introvert, while the bourgeois messages were more extrovert and public. We can envisage an intimate connection between the material culture as represented by the inscriptions and the persons involved. Perhaps the owner of the castle of Glimmingehus received guests standing in the doorway under the large stone tablet with the long inscription that told the story of his efforts as a builder and presented his present and former wife. The guests were probably gathered on the courtyard below. The person, the building, and the stone tablet became one representation, in this case of a successful nobleman and his social network.

In contrast to the nobility, the burghers’ messages were available in what can be said to be the urban living room, the street. That they also were made in the vernacular languages, Danish and German, helped to make their messages more accessible to an urban audience. It might also reflect the high degree of literacy within the urban elite. The symbols on the tablets, the initials and owner’s marks, were probably difficult to interpret if an audience was not familiar with the senders behind the message. Despite their public position, to some extent they were still aimed at a limited audience, individuals in the same group as the senders, the urban elite. In this way the individuality expressed by both groups was not individuality in a modern sense, but rather an individuality that was underlined and stressed within a group of equals. Putting up a tablet with a text and a date can thus be seen as a reflection of a mentality where traditional ideas where combined with new thoughts about identity and individuality.

References

Andrén, A. (1997). Mellan ting och text: en introduktion till de historiska arkeologierna. Symposium, Eslöv.

Atzbach, R. (2017). Reformationens spor i hverdagslivet. In Høiris, O. and Ingesman, P. (eds.), Reformationen: 1500-tallets kulturrevolution. Bind 2, Danmark. Aarhus Universitetsforlag, Aarhus, pp. 351–369.

Bӕksted, A. (1968). Danske Indskrifter: En inledning til studiet af dansk epigrafik. Dansk historisk fӕllesforenings håndbøger, København.

Bager, E. (1937). Ett bidrag till bomärkenas historia. Malmö Fornminnesförenings Årsskrift, 7–16.

Bager, E. (1955). Gleerupska skulpturerna och Lauritz Hattemagers bomärke. Malmö Fornminnesförenings Årsskrift, 37–49.

Bager, E. (1971). Malmö Stads byggnadshistoria till 1820. In Bjurling, O. (ed.), Malmö Stads Historia, Första delen. Malmö, pp. 254–406.

Beckett, F. (1897). Renaissancens og Kunstens Historie i Danmark: Studier i de bevarade mindesmærker. København.

Bergman, E. (1934). Inskriptionsstenar rörande Tycho Brahes papperskvarn. Fornvännen, 118–121.

Biernoff, S. (2002). Sight and Embodiment in the Middle Ages. Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Blennow, A. (2016). Sveriges medeltida latinska inskrifter 1050–1250: Edition med språklig och paleografisk kommentar. The Swedish History Museum Studies 28, Stockholm.

Brugge, E. (1951). Lågtyska inskrifter på borgarhus i Malmö. Malmö Fornminnesförenings Årsskrift, 52–64.

Bruun, C. and Edmondson, J. (2015). The Oxford Handbook of Roman Epigraphy. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Burckhardt, J, (1995). The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy. 3d ed. Phaidon, London.

Burke, P. (1998). The European Renaissance: Centres and Peripheries. Blackwell, Oxford.

Camille, M. (2000). Before the gaze: the internal senses and late medieval practices of seeing. In Nelson, R. (ed.), Visuality Before and Beyond the Renaissance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 197–223.

Carelli, P. (2003). Krapperup och det feodala landskapet: Borgen, bygden och den medeltida bebyggelseutvecklingen i en nordvästskånsk socken. Gyllenstiernska Krapperupstiftelsen, Lund.

Champion, M. (2015). Medieval Graffiti, the Lost Voices of England’s Churches. Ebury, London.

Dobres, M-A. and Robb, J. E. (2000). Agency in archaeology: paradigm or platitude? In Dobres, M-A. and Robb, J. E. (eds.), Agency in Archaeology. Routledge, London, pp. 3–17.

Dransart, P. (2015). Arma Christi in the Tower Households of North-Eastern Scotland. In Oram, R. (ed.), Tower Studies, 1 & 2: “A house that Thieves Might Knock at.” Shayn Tyas, Donington, pp. 154–173.

Foster, H. (1988). Vision and Visuality. Bay Press, Seattle.

Frieman, C. and Gillings, M. (2007). Seeing is perceiving? World Archaeology 39(1): 4–16.

Frykman, J. and Ehn, B. (eds.) (2007). Minnesmärken: Att tolka det förflutna och besvärja framtiden. Carlssons Förlag, Stockholm.

Gardell, S. (1945). Gravmonument från Sveriges medeltid, 1 Text. Kungl. Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Akademiens Handlingar, Stockholm.

Gell, A. (1998). Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory. Clarendon, Oxford.

Gilchrist, R. (2009). Medieval archaeology and theory: a disciplinary leap of faith. In Gilchrist, R. and Reynolds, A. (eds.), Reflections: 50 years of Medieval Archaeology, 1957–2007. Maney, Leeds, pp. 385–408.

Giles, K. (2007). Seeing and believing, visuality and space in pre-modern England. World Archaeology 39(1): 105–121.

Goody, J. (1986). The Logic of Writing and Organization of Society. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Graves, P. (2007). Sensing and believing, exploring worlds of difference in pre-modern England, a contribution to the debate opened by Kate Giles. World Archaeology 39(4): 515–531.

Hahr, A. (1922). Skånska borgar: Uppmätningsritningar, Fotografiska avbildningar samt beskrivande text. Norstedts, Stockholm.

Hansen, A. (1991). Om Peder Laales danske ordsprog. Udgivet af Merete K. Jørgensen og Iver Kjær. Historisk-filosofiske Meddelelser 62, Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab, København.

Hansen, K. (2020). Medeltida stadsaristokrati: Världsligt frälse i de skånska landskapens städer. Lund studies in historical archaeology 21, Lund.

Hansen, S-I. (1992). Senmiddelalderlige herregårdsbygninger: Senmiddelalderlige, grundmurede herregårds-hovedbygninger i kongeriget Danmark. En redogørelse for typer, planer og funktioner på baggrund av bevarade bygningsrester. “Afd. For Middelalderarkæologi” og “Middelalder-arkæologisk Nyhedsbrev,” Aarhus Universitet, Århus.

Hansson, M. (2010). Byggherrar och porträttmotiv: Ett arkeologiskt perspektiv på aktörer och individer i det senmedeltida och tidigmedeltida Norden. In Lihammer, A. and Nordin, J. M. (eds.), Modernitetens Materialitet: Arkeologiska Perspektiv på det Moderna Samhällets Framväxt. Museum of National Antiquities, Stockholm, pp. 131–150.

Hansson, M. (2016). Stone tablets, memorial texts and agency in late medieval Scandinavian castles: the examples of Glimmingehus and Olovsborg. Medieval Archaeology 60:2: 311–331.

Hansson, M. (2019). Tunga ting med text. Sivert Grubbe och eftermälet. In Ljung, C., Andreasson Sjögren, A., Berg, I., Engström, E., Hållans Stenholm, A-M., Jonsson, K., Klevnäs, A., Qviström, L. and Zachrisson, T., eds., Tidens landskap: En vänbok till Anders Andrén. Nordic Academic Press, Lund, pp. 48–50.

Harasimovicz, J. (2011). Wort – Bild – Wort. Die Rhetorik der Lutherischen Kirchenkunst Nordeuropas im 16. Und 17, Jahrhundert. In Andersen, M., Bøggild Johannsen, B., and Johannsen, H. (eds.), Reframing the Danish Renaissance: Problems and Prospects in a European Perspective, Papers from an International Conference in Copenhagen, 28 September – 1 October 2006. National Museum, København, pp. 104–116.

Heck, K. (2002). Genealogi als Monument und Argument: Der Beitrag dynastischer Wappen zur politischen Raumsbildung der Neuzeit. Deutscher Kunstverlag, München.

Houston, R. A. (1988). Literacy in Early Modern Europe: Culture and Education 1500–1800. Longman, London.

Imer, L. (2016). Danmarks Runesten: En fortælling. Nationalmuseet & Gyldendal, København.

Jern, C. H. (1976). Uraniborg: Herresäte och himlaborg, Studentlitteratur, Lund.

Jespersen, L. (2001). Adel, hof og embede i adelsvældens tid. In Ingesman, P. and Jensen, V. J. (eds.), Riget, magten og æren: Den danske adel 1350–1660. Aarhus Universitetsforlag, Århus, pp. 369–397.

Johannesson, K. (1996). Renässansens bildvärld. In Alm, G. (ed.), Signums svenska konsthistoria: Renässansens konst. Signum, Lund, pp. 9–31.

Johansson, S. (1985). Det Borgska huset i Lund. Bygningsarkæologiske Studier, 23–31.

Johnson, M. (2000). Self-made men and the staging of agency. In Dobres, M.-A. and Robb, J. E. (eds.), Agency in Archaeology. Routledge, London, pp. 313–231.

Johnson, M. (2002). Behind the Castle Gate: From Medieval to the Renaissance. Routledge, London.

King, C. (2003). The organization of social space in late medieval manor houses: an East Anglian study. Archaeological Journal 160(1): 104–124.

Kjellberg, S. (1966a). Slott och herresäten i Sverige: ett konst- och kulturhistoriskt samlingsverk. Skåne, Bd 1, Malmöhus län, Norra delen. Allhem, Malmö.

Kjellberg, S. (1966b). Slott och herresäten i Sverige: ett konst- och kulturhistoriskt samlingsverk. Skåne, Bd 3 Kristianstads län. Allhem, Malmö.

Kjellberg, S. (1966c). Slott och herresäten i Sverige: ett konst- och kulturhistoriskt samlingsverk. Skåne, Bd 2, Malmöhus län, Södra delen. Allhem, Malmö.

Knapp, B. and van Dommelen, P. (2008). Past practices: rethinking individuals and agents in archaeology. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 18(1): 15–34.

Kraack, D. (1997). Monumentale Zeugnisse der Spätmittelalterlichen Adelsreise: Inschriften und Graffiti des 14–16 Jahrhunderts, Abhandlungen der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen. Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, Göttingen.

Lorenzen, V. (1921). Studier i Dansk Herregaards Arkitektur i 16. og 17. Aarhundrede. Udgivet af Den Danske Historiske Forening, H Hagerups Forlag, København.

Moreland, J. (2001). Archaeology and Text. Duckworth, London.

Moreland, J. (2006). Archaeology and texts: subservience or enlightenment? Annual Review of Anthropology 35: 135–151.

Mytum. H. (2007). Materiality and memory: an archaeological perspective on the popular adoption of linear time in Britain. Antiquity 81: 381–396.

Olin, M. (2005). Porträtt. In Christensson, J. (ed.), Signums svenska kulturhistoria. Renässansen. Signum, Lund, pp. 427–463.

Olsson, P.-A. (1922a). Hofdala. In Hahr, A. (ed.), Skånska borgar: Uppmätningsritningar, Fotografiska avbildningar samt beskrivande text. H11/12, Sandby och Hofdala. Norstedts, Stockholm, pp. 24–42.

Olsson, P.-A. (1922b). Skånska herreborgar: Ur synpunkten av deras fortifikatoriska anordningars betydelse för arkitekturen. Gleerups, Lund.

Ong, W. (1986). Writing is a technology that restructures thought. In Baumann, G. (ed.), The Written Word: Literacy in Transition. Clarendon, Oxford, pp. 23–50.

Ong, W. (2002). Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. Routledge, London.

Pernler, S-E. (2014). Latinet som inte finns – om “stavfel”, en osannolik inskrift och ett manipulerat utlåtande. In Stobaeus, P., ed., Gutagåtor: Historiska problem och tolkningar. Arkiv på Gotland 9, Visby, pp. 47–63.

Ranby, C. (2003). Krapperup mellan renässans och skiftesreformer: Vol. 1 Borgen och byarna 1550–1850. Gyllenstiernska Krapperupsstiftelsen, Nyhamnsläge.

Reisnert, A. (1999). Människor och byggnader i 1500-talets Malmö. In Magnusson Staaf, B., Reisnert, A., and Björklund, E. (eds.), Malmös möte med renässansen. Malmö Museer, Malmö, pp. 52–82.

Reisnert, A. (2008). Luxury in Malmö in the medieval period. In Gläser, M. (ed.), Lübecker Kolloquium zur Stadtarchäologie im Hanseraum VI: Luxus und Lifestyle. Bereich Archäeologie unde Denkmalpflege der Hansestadt Lübeck, Lübeck, pp. 627–640.

Richardson, A. (2003). Gender and space in English royal palaces c. 1150–c. 1547: a study in access analysis and imagery. Medieval Archaeology 47: 131–165.

Robb, J. (2010). Beyond agency. World Archaeology 42(4): 493–520.

Ronnes, H. and Westra, A. (2011). An age of autography: the English sixteenth-century country house and its dated inscriptions. Explorations in Renaissance Culture 37(2): 39–64.

Rosborg, S. (2016). Det medeltida Malmö: Detektivarbeten under mer än ett sekel i en gammal stads historia. Publikum, Belgrad.

Sandblad, N.G. (1949). Skånsk stadsplanekonst och stadsarkitektur intill 1658, Skånsk senmedeltid och renässans 2. Skrifter utgivna av Vetenskapssocieteten i Lund, Lund.

Sawyer, B. (2002). Runstenar och förmedeltida arvsförhållanden. In Agertz, J. and Varenius, L. (eds.), Om runstenar i Jönköpings län. Småländska kulturbilder, Jönköping, pp. 55–78.

Schaefer, W.-M. (1920). Hausinschriften und Haussprüche. Allgemeine und Analytische Untersuchungen zur deutschen Inschriftenfunde. Hessische Blätter für Volkskunde. Herausgegeben im Auftrage der hessischen Vereinigung für Volkskunde. Band XIX. Marburg, pp. 1–114.

Smed, M. (2017). Jeg byggede dette hus. Renæssancens adelskvinder som herregårdsbyggere. In Jacobsen, G. and Jørgensen, N. (eds.), Kvindernes Renæssance og Reformation. Museum Tusculanum Forlag, København, pp. 161–179.

Söderberg, B. (2010). Introduktion. In Larsson, I., Jansson, S.-B., Palm, R., and Söderberg, B. (eds.), Den medeltida skriftkulturen i Sverige: Genrer och texter. Sällskapet Runica et Mediævalia, Stockholms universitet, Stockholm, pp. 9–19.

Staecker, J. (2003). A Protestant habitus: 16th century Danish graveslabs as an expression of changes in belief. In Gaimster, D. and Gilchrist, R. (eds.), The Archaeology of Reformation 1480–1580. Maney, Leeds, pp. 415–436.

Thomasson, J. (1997). Private life made public: one aspect of the emergence of the burghers in medieval Denmark. In Andersson, H., Carelli, P., and Ersgård, L. (eds.), Visions of the Past: Trends and Traditions in Swedish Medieval Archaeology. Stockholm, pp. 697–728.

Thomasson, J. (2004). Out of the past: the biography of a 16th-century burgher house and the making of society. Archaeological Dialogues 11(2): 165–189.

Troels-Lund, F. (1903a). Dagligt liv i Norden på 1500-talet: II, Bønder- og Købstadsboliger. Anden udgave. Gyldendals, København.

Troels-Lund, F. (1903b). Dagligt liv i Norden på 1500-talet: III, Herrgårdar och Slott. Anden udgave. Gyldendals, København.

Ullgren, P. (2004). Lantadel: Adliga godsägare i Östergötland och Skåne vid 1600-talets slut. Sisyfos, Lund.

Vellev, J. (2017). Et industrianlæg og en votivsten på Hven fra Renæssancen: Om Tycho Brahes papirmølle. Renæssanceforum 12: 107–129.

Wallin, C. (1979). Jens Holgersen Ulfstand och Glimmingehus. Österleniana, Tomelilla.

Widera, J. (1990). Möglichkeiten und Grenzen volkskundlicher Interpretationen von Hausinschriften. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main.

Wienberg, J. (1993). Den gotiske labyrint: Middelalderen og kirkerne i Danmark. Almqvist and Wiksell International, Stockholm.

Wienberg, J. (2007). Kanon og glemsel. Arkæologiens mindesmærker. Kuml, Årbog for Jysk arkæologisk Selskab, pp. 237–282.

Zachrisson, T. (1998). Gård, gräns, gravfält: Sammanhang kring ädelmetalldepåer och runstenar från vikingatid och tidigmedeltid i Uppland och Gästrikland. Stockholm.

Zachrisson, T. (2002). Ärinvards minne − om runstenen i Norra Sandsjö. In Agertz, J. and Varenius, L. (eds.), Om runstenar i Jönköpings län. Småländska kulturbilder, Jönköping, pp. 35−54.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Professor Jes Wienberg, Lund University, and two anonymous reviewers for valuable comments on an earlier draft of this paper. The research was funded by a grant from Gyllenstiernska Krapperupsstiftelsen and by Lund University. The English was revised by Alan Crozier.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Lund University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hansson, M. Inscriptions and Images in Secular Buildings: Examples from Renaissance Scania, Sweden, ca. 1450–1658. Int J Histor Archaeol 26, 623–646 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-021-00616-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-021-00616-5