Abstract

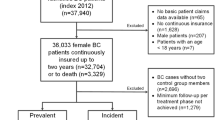

The Massart (J Cancer Policy 15:70–71, 2018) testimonial illustrates the difficulties faced by patients having survived cancer to access mortgage insurance securing home loan. Data collected by national registries nevertheless suggest that excess mortality due to some types of cancer becomes moderate or even negligible after some waiting period. In relation to the insurance laws passed in France and more recently in Belgium creating a right to be forgotten for cancer survivors, the present study aims to determine the waiting period after which standard premium rates become applicable. Compared to the French and Belgian laws, a waiting period starting at diagnosis (as recorded in national databases) is favored over a waiting period starting at the end of the therapeutic treatment protocol. This aims to avoid disputes when a claim is filed. Since diagnosis is often recorded in the official registry database, as is the case for the Belgian Cancer Registry, its date is reliable and unquestionable in case of claim. Based on 28,994 melanoma and thyroid cancer cases recorded by the Belgian Cancer Registry, the length of the waiting period is assessed with the help of widely-accepted tools from biostatistics, including relative survival models and time-to-cure indicators. It turns out for instance that a waiting period of 4 years after diagnosis is enough for 30-year-old thyroid cancer patients. This appears to be similar to the 3-year period starting at the end of treatment protocol according to the Belgian law in such a case.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Amico M, Van Keilegom I (2018) Cure models in survival analysis. Annu Rev Stat Appl 5:311–342

Andersson TM, Dickman PW, Eloranta S, Lambert PC (2011) Estimating and modelling cure in population-based cancer studies within the framework of flexible parametric survival models. BMC Med Res Methodol 11(1):96

Bailar JC III, Smith EM (1986) Progress against cancer? N Engl J Med 314(19):1226–1232

Balch CM, Soong S-J, Gershenwald JE, Thompson JF, Reintgen DS, Cascinelli N, Urist M, McMasters KM, Ross MI, Kirkwood JM et al (2001) Prognostic factors analysis of 17,600 melanoma patients: validation of the american joint committee on cancer melanoma staging system. J Clin Oncol 19(16):3622–3634

Belot A, Ndiaye A, Luque-Fernandez M-A, Kipourou D-K, Maringe C, Rubio FJ, Rachet B (2019) Summarizing and communicating on survival data according to the audience: a tutorial on different measures illustrated with population-based cancer registry data. Clin Epidemiol 11:53–65

Berkson J, Gage RP (1950) Calculation of survival rates for cancer. In: Proceedings of the staff meetings. Mayo Clinic, vol 25, p 270

Berkson J, Gage RP (1952) Survival curve for cancer patients following treatment. J Am Stat Assoc 47(259):501–515

Berrino F, Capocaccia R, Estève J, Gatta G, Hakulinen T, Micheli A, Sant M, Verdecchia A (1999) Survival of cancer patients in europe: the eurocare-2 study. In: Survival of cancer patients in Europe: the EUROCARE-2 study, pp 1–CD

Boag JW (1949) Maximum likelihood estimates of the proportion of patients cured by cancer therapy. J R Stat Soc Ser B (Methodological) 11(1):15–53

Bolard P, Quantin C, Esteve J, Faivre J, Abrahamowicz M (2001) Modelling time-dependent hazard ratios in relative survival: application to colon cancer. J Clin Epidemiol 54(10):986–996

Boussari O, Romain G, Remontet L, Bossard N, Mounier M, Bouvier A-M, Binquet C, Colonna M, Jooste V (2018) A new approach to estimate time-to-cure from cancer registries data. Cancer Epidemiol 53:72–80

Buckley J (1984) Additive and multiplicative models for relative survival rates. Biometrics 40:51–62

Bureau du suivi de la tarification (2018) Rapport sur l’activité 2017. https://www.bureaudusuivi.be/images/docs/RapportAnnuel_2017.pdf

Chang AE, Ganz PA, Hayes DF, Kinsella T, Pass HI, Schiller JH, Stone RM, Strecher V (2007) Oncology: an evidence-based approach. Springer, Berlin

Chauvenet M, Lepage C, Jooste V, Cottet V, Faivre J, Bouvier A-M (2009) Prevalence of patients with colorectal cancer requiring follow-up or active treatment. Eur J Cancer 45(8):1460–1465

Chen M-H, Ibrahim JG, Sinha D (1999) A new Bayesian model for survival data with a surviving fraction. J Am Stat Assoc 94(447):909–919

Clements M, Liu X-R (2019) rstpm2: Smooth Survival Models, Including Generalized Survival Models. R package version 1(5):1

Clerc-Urmès I, Grzebyk M, Hédelin G, CENSUR working survival group (2020) flexrsurv: An R package for relative survival analysis. R package version 1(4):5

Cleveland WS, Grosse E (1991) Computational methods for local regression. Stat Comput 1(1):47–62

Cleveland WS, Devlin SJ, Grosse E (1988) Regression by local fitting: methods, properties, and computational algorithms. J Econometr 37(1):87–114

Cleveland W, Grosse E, Shyu M (1992) A package of c and fortran routines for fitting local regression models. In: Chambers JM (ed) Statistical methods. S. Chapman and Hall Ltd., London

Coleman MP, Babb P, Damiecki P, Grosclaude P, Honjo S, Jones J, Knerer G, Pitard A, Quinn M, Sloggett A et al (1999) Cancer survival trends in England and Wales, 1971–1995: deprivation and NHS region. Stationery Office Books

Dal Maso L, Guzzinati S, Buzzoni C, Capocaccia R, Serraino D, Caldarella A, Dei Tos A, Falcini F, Autelitano M, Masanotti G et al (2014) Long-term survival, prevalence, and cure of cancer: a population-based estimation for 818 902 italian patients and 26 cancer types. Ann Oncol 25(11):2251–2260

Danieli C, Remontet L, Bossard N, Roche L, Belot A (2012) Estimating net survival: the importance of allowing for informative censoring. Stat Med 31(8):775–786

Dickman PW, Sloggett A, Hills M, Hakulinen T (2004) Regression models for relative survival. Stat Med 23(1):51–64

Dodd EO, Streftaris G, Waters HR, Stott AD (2015) The effect of model uncertainty on the pricing of critical illness insurance. Ann Actuar Sci 9(1):108–133

Eilers PH, Marx BD (1996) Flexible smoothing with b-splines and penalties. Stat Sci 11(2):89–102

Enstrom JE, Austin DF (1977) Interpreting cancer survival rates. Science 195(4281):847–851

Esteve J, Benhamou E, Croasdale M, Raymond L (1990) Relative survival and the estimation of net survival: elements for further discussion. Stat Med 9(5):529–538

Esteve J, Benhamou E, Raymond L et al (1994) Statistical methods in cancer research. volume iv. descriptive epidemiology. IARC Sci publ 128(1):302

Fauvernier M, Remontet L, Uhry Z, Bossard N, Roche L (2019a) survpen: an r package for hazard and excess hazard modelling with multidimensional penalized splines. J Open Sour Softw 4(40):1434

Fauvernier M, Roche L, Uhry Z, Tron L, Bossard N, Remontet L, and in the Estimation of Net Survival Working Survival Group C (2019b) Multi-dimensional penalized hazard model with continuous covariates: applications for studying trends and social inequalities in cancer survival. J R Stat Soc Ser C (Applied Statistics)

Geskus RB (2015) Data analysis with competing risks and intermediate states, vol 82. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Giorgi R, Payan J, Gouvernet J (2005) Rsurv: a function to perform relative survival analysis with s-plus or r. Comput Methods Progr Biomed 78(2):175–178

Haberman S, Renshaw A (1990) Generalised linear models and excess mortality from peptic ulcers. Insur Math Econ 9(1):21–32

Hakulinen T, Tenkanen L (1987) Regression analysis of relative survival rates. J R Stat Soc Ser C (Appl Stat) 36(3):309–317

Jooste V, Grosclaude P, Remontet L, Launoy G, Baldi I, Molinié F, Arveux P, Bossard N, Bouvier A-M, Colonna M et al (2013) Unbiased estimates of long-term net survival of solid cancers in france. Int J Cancer 132(10):2370–2377

Kaplan EL, Meier P (1958) Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc 53(282):457–481

Lambert PC, Thompson JR, Weston CL, Dickman PW (2006) Estimating and modeling the cure fraction in population-based cancer survival analysis. Biostatistics 8(3):576–594

Latouche A, Allignol A, Beyersmann J, Labopin M, Fine JP (2013) A competing risks analysis should report results on all cause-specific hazards and cumulative incidence functions. J Clin Epidemiol 66(6):648–653

Legrand C, Bertrand A (2019) Cure models in oncology clinical trials. Textb Clin Trials Oncol Stat Perspect 1:465–492

Lemaire J, Subramanian K, Armstrong K, Asch DA (2000) Pricing term insurance in the presence of a family history of breast or ovarian cancer. N Am Actuar J 4(2):75–87

Lenner P (1990) The excess mortality rate: a useful concept in cancer epidemiology. Acta Oncol 29(5):573–576

Maller RA, Zhou X (1996) Survival analysis with long-term survivors. Wiley, Oxford

Massart M (2018) A long-term survivor’s perspective on supportive policy for a better access to insurance, loan and mortgage. J Cancer Policy 15:70–71

Mounier M (2015) Apport des méthodes de survie nette dans le pronostic des lymphomes malins non hodgkiniens en population générale. PhD thesis, Université Claude Bernard-Lyon I

Oksanen H (1998) Modelling the survival of prostate cancer patients. University of Tampere

Othus M, Barlogie B, LeBlanc ML, Crowley JJ (2012) Cure models as a useful statistical tool for analyzing survival. Clin Cancer Res 18(14):3731–3736

Pavlič K, Pohar Perme M (2019) Using pseudo-observations for estimation in relative survival. Biostatistics 20(3):384–399

Percy C, Stanek E 3rd, Gloeckler L (1981) Accuracy of cancer death certificates and its effect on cancer mortality statistics. Am J Public Health 71(3):242–250

Perme MP, Pavlič K (2018) Nonparametric relative survival analysis with the R package relsurv. J Stat Softw 87(8):1–27

Perme MP, Stare J, Estève J (2012) On estimation in relative survival. Biometrics 68(1):113–120

Perme MP, Estève J, Rachet B (2016) Analysing population-based cancer survival-settling the controversies. BMC Cancer 16(1):1–8

Pohar M, Stare J (2006) Relative survival analysis in r. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 81(3):272–278

Quantin C, Abrahamowicz M, Moreau T, Bartlett G, MacKenzie T, Adnane Tazi M, Lalonde L, Faivre J (1999) Variation over time of the effects of prognostic factors in a population-based study of colon cancer: comparison of statistical models. Am J Epidemiol 150(11):1188–1200

R Core Team (2017) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria

Remontet L, Uhry Z, Bossard N, Iwaz J, Belot A, Danieli C, Charvat H, Roche L, Group C W S (2019) Flexible and structured survival model for a simultaneous estimation of non-linear and non-proportional effects and complex interactions between continuous variables: Performance of this multidimensional penalized spline approach in net survival trend analysis. Stat Methods Med Res 28(8):2368–2384

Renshaw AE (1988) Modelling excess mortality using glim. J Inst Actuar 115(2):299–315

Ries L, Eisner M, Kosary C, Hankey B, Miller B, Clegg L, Edwards B (2002) Seer cancer statistics review, 1973–1999. bethesda, md: National cancer institute. https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1973-1999

Schaffar R, Rachet B, Belot A, Woods LM (2017) Estimation of net survival for cancer patients: relative survival setting more robust to some assumption violations than cause-specific setting, a sensitivity analysis on empirical data. Eur J Cancer 72:78–83

Schvartsman G, Taranto P, Glitza IC, Agarwala SS, Atkins MB, Buzaid AC (2019) Management of metastatic cutaneous melanoma: updates in clinical practice. Ther Adv Med Oncol 11:1758835919851663

Shang K (2019) Individual Cancer Mortality Prediction. Fundaciòn Mapfre

Silversmit G, Jegou D, Vaes E, Van Hoof E, Goetghebeur E, Van Eycken L (2017) Cure of cancer for seven cancer sites in the Flemish region. Int J Cancer 140(5):1102–1110

The Belgian Cancer Registry (2012) Cancer survival in belgium. https://kankerregister.org/media/docs/publications/CancerSurvivalinBelgium.PDF

Tsodikov A, Ibrahim J, Yakovlev A (2003) Estimating cure rates from survival data: an alternative to two-component mixture models. J Am Stat Assoc 98(464):1063–1078

Tsodikov AD, Yakovlev AY, Asselain B (1996) Stochastic models of tumor latency and their biostatistical applications, vol 1. World Scientific, Singapore

Yue JC, Wang H-C, Leong Y-Y, Su W-P (2018) Using Taiwan national health insurance database to model cancer incidence and mortality rates. Insur Math Econ 78:316–324

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by a UCLouvain grant. The three first authors express their sincere gratitude to the university for making such a research project possible. The support of the Belgian Cancer Registry is gratefully acknowledged for providing access to the data and for research assistance. The authors also thank the two anonymous referees for comments that have been very helpful for revising previous versions of the present work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Soetewey, A., Legrand, C., Denuit, M. et al. Waiting period from diagnosis for mortgage insurance issued to cancer survivors. Eur. Actuar. J. 11, 135–160 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13385-020-00254-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13385-020-00254-x