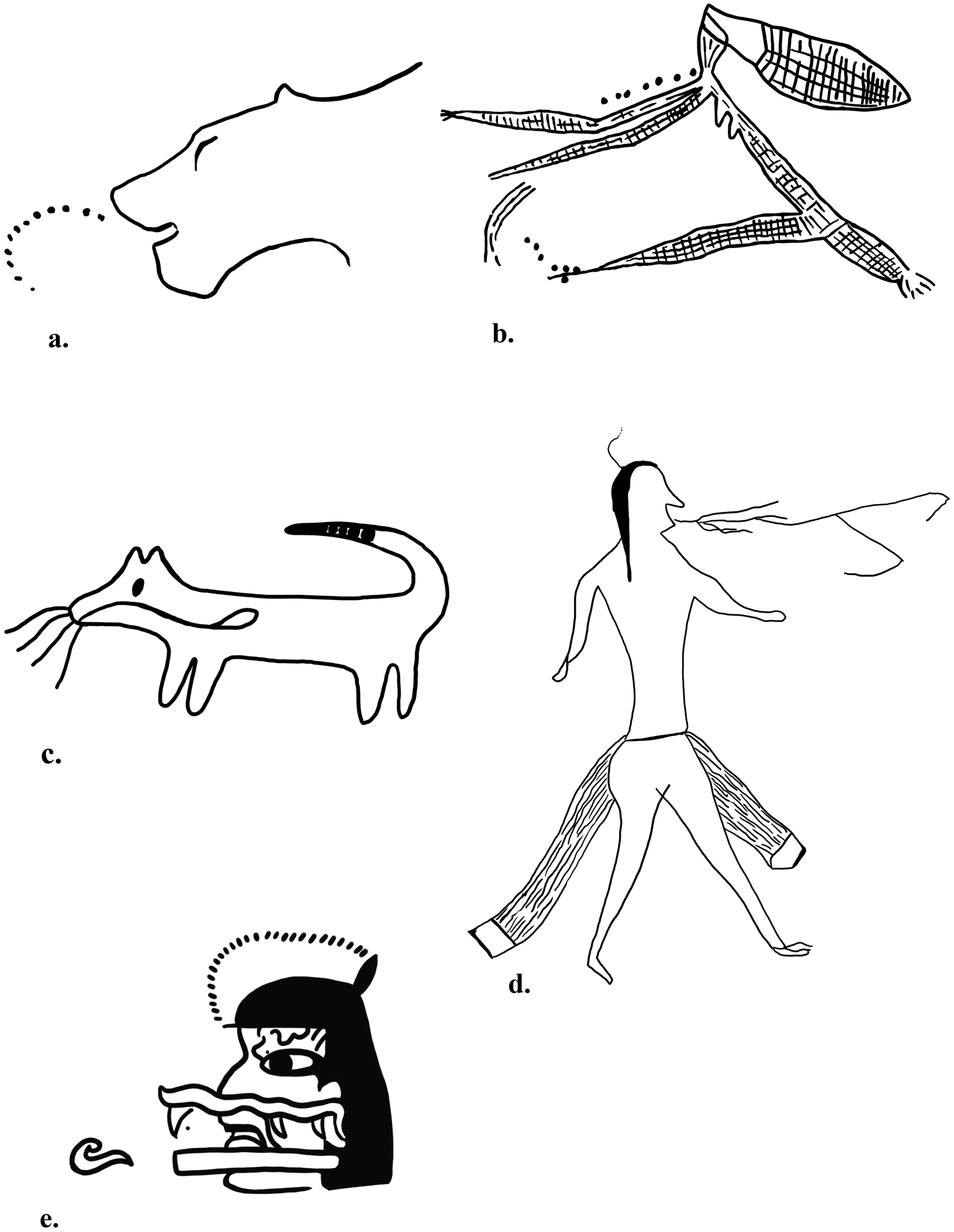

In Houston and Taube's seminal article “An Archaeology of the Senses,” they write that the “sensations of the past cannot be retrieved, only their encoding in imperishable media” (Reference Houston and Taube2000:263). Rock art produced through the millennia and preserved in deep caves and dry rockshelters around the world encode these sensations of the past. As far back as 36,000 years ago during the Upper Paleolithic in Europe, artists used graphic devices at Chauvet Cave to signify and activate the senses (Jean-Michel Geneste, personal communication 2020; Figure 1a). Approximately 10,000 years ago in Australia's Western Arnhem Land, artists used dots and dashes to convey speech and breath in rock art (Taçon and Chippindale Reference Taçon and Chippindale1994:217; Figure 1b). In the American Southwest and across the Great Plains of the United States, artists used lines, dots, and other imagery to portray vocalization and to render breath visible (Conner Reference Conner1980:7–9; Mallery Reference Mallery1893:717–719; Stephen Reference Stephen and Parsons1936:639–640; Taube Reference Taube, Fields and Zamudio-Taylor2001; Figure 1c, d). But it is in the artistic traditions of Mesoamerica that we find the broadest use of graphic devices to denote sound and breath. As noted by Hajovsky (Reference Hajovsky2015:60), “It would be an extensive project to catalog all instances of this ubiquitous glyph in Mesoamerica and to identify its significance across a wide geographic area, among different linguistic groups, and through a very long period.”

Figure 1. Global examples of speech-breath (drawings by Carolyn E. Boyd): (a) red dots emerge from the face of a lion at Chauvet Cave, France; (b) dots denoting speech emanate from the face of a figure found in a shelter near the Mann River, Northern Territory, Australia (after Taçon Reference Taçon1994:31); (c) Hopi ritualist used lines to denote breath in this nineteenth-century Hopi sandpainting of a lion (after Stephen Reference Stephen and Parsons1936:Figure 350); (d) lines representing speech in a letter written by a Southern Cheyenne during the late 1800s (after Mallery Reference Mallery1893:Figure 472); and (e) Olmec speech scroll (after Grove Reference Grove1970:Figure 19).

In Mesoamerica, the earliest examples of glyphs denoting speech and breath were produced by the Olmec during the Middle Formative period (ca. 900–100 BC; Grove Reference Grove1970; Houston and Taube Reference Houston and Taube2000:265). On the wall of Oxtotitlan Cave in Guerrero, Mexico, an artist painted a profile image of a human head wearing a helmet and serpent mask. Ten centimeters in front of the figure's mouth is a small scroll representing speech (Figure 1e). This and similar artistic conventions continued for more than 2,000 years, becoming highly elaborated through the Postclassic and into the colonial period (AD 1521–1821). Artists used these visual stimuli to trigger auditory and olfactory responses in the viewer (Houston and Taube Reference Houston and Taube2000:261). Sound and scent, in the form of song, heated oratory, and aromatic fragrances, were agentive and intimately associated with creation and concepts of the soul.

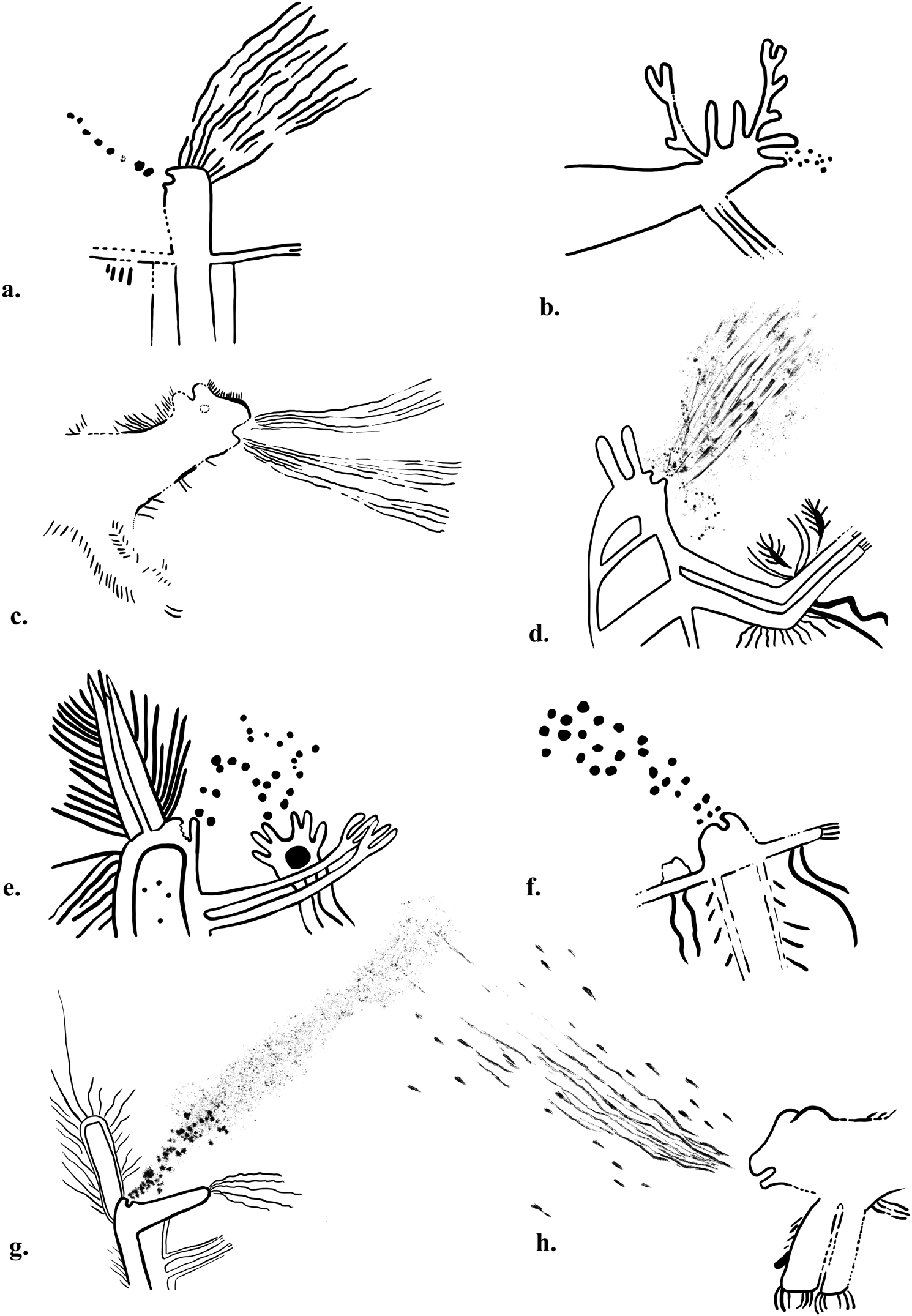

Hunter-gatherer artists living in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands of southwest Texas and northern Mexico used similar visual stimuli to transform the ephemeral and intangible qualities of hearing and smell into something enduring and palpable. Radiocarbon assays obtained for Pecos River style (PRS) paintings place production of the art to at least 1700 cal BC (Steelman, Boyd, and Allen Reference Steelman, Boyd and Allen2021), centuries before the earliest known graphic representation of speech-breath in Mesoamerica. In this article, we examine a recurring motif in PRS rock paintings: dots and lines exiting or entering the mouth of anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures (Figure 2a–h and Figure 3).Footnote 1 We propose that Lower Pecos artists used these graphic devices not only to denote speech and breath but to transmit vital forces heavenward through images infused with life. Through our analysis of the speech-breath element, we provide insight into the artists’ conception of the senses, how they perceived and categorized reality, and how they experienced the art and the information encoded in it.

Figure 2. Examples of PRS speech-breath (drawings by Carolyn E. Boyd): (a) anthropomorph with a row of dots denoting speech-breath (41VV83); (b) deer with dotted speech-breath (41VV76); (c) feline with lines representing sound or breath (41VV696); (d) multicomponent speech-breath combining dots and lines (41VV83); (e) amorphous arrangement (41VV128); (f) circumscribed arrangement radiating outward at an acute angle (41VV696); (g) expedient dots and splatter paint emitted from the anthropomorph's mouth combine to display forceful action (41VV696); (h) feline with forceful speech-breath combining long, thin, undulating lines and short, thicker brushstrokes; the short brushstrokes move toward the feline's face (41VV612).

Figure 3. Rattlesnake Canyon (41VV180). The forceful speech or breath of two anthropomorphs intersects to form an X (drawing by Carolyn E. Boyd). (Color online)

Lower Pecos Canyonlands

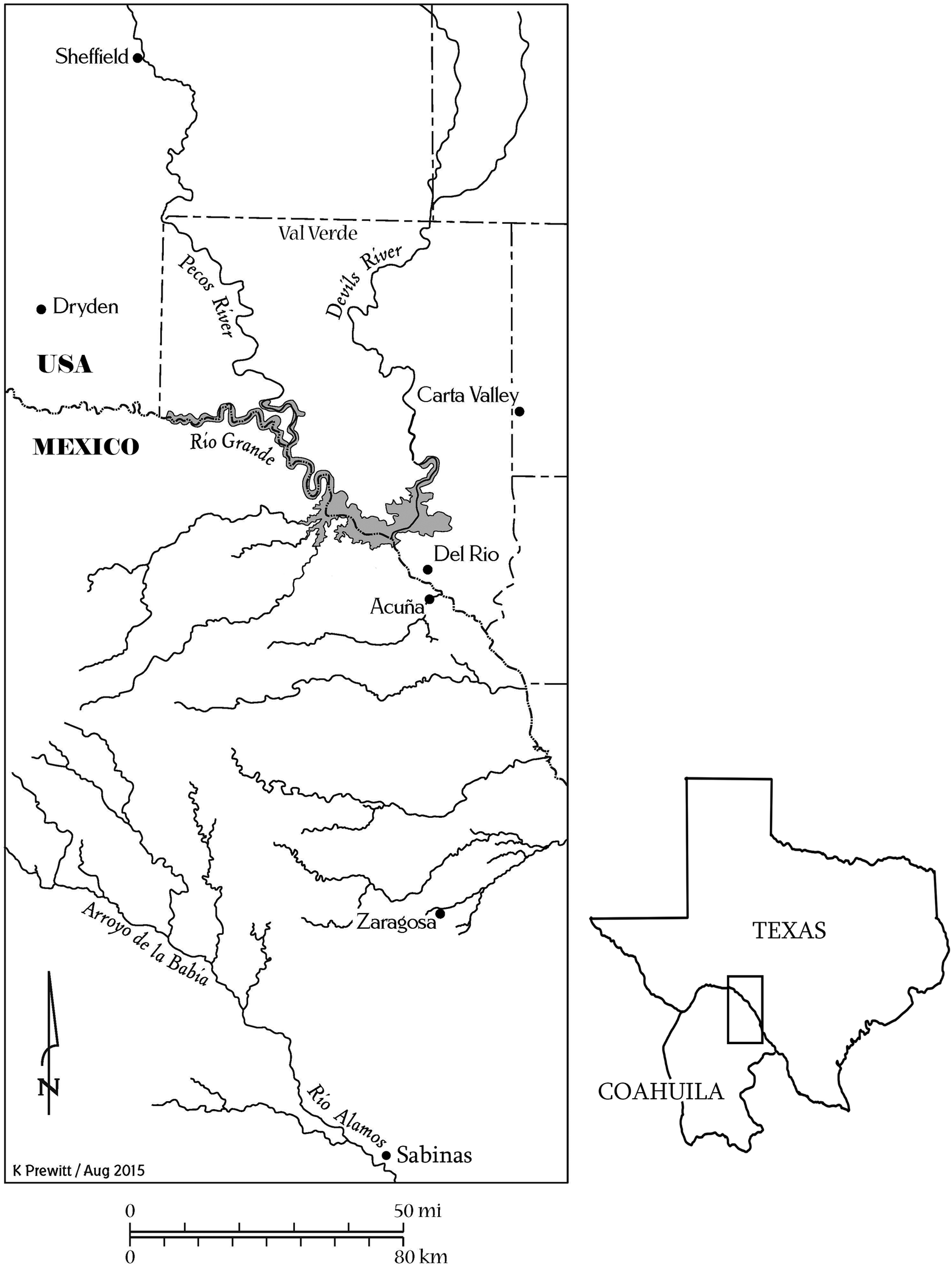

The Lower Pecos Canyonlands are situated within the Gran Chichimeca at the edge of the Edwards Plateau and the Chihuahuan Desert (Figure 4).Footnote 2 The northern half of the Lower Pecos lies in southwest Texas and the southern half in Coahuila, Mexico. Near the region's center, the Pecos and Devils Rivers converge with the Rio Grande. Over the millennia these rivers and their tributaries have sliced through masses of gray and white limestone rock to create a dramatic landscape incised by deep, narrow gorges housing rockshelters. The rockshelters contain a rich record in deep deposits of food remains, medicinal plants, wood, fiber, and bone and stone implements, and on the walls, there are hundreds of multicolored pictographs (Boyd Reference Boyd2003; Boyd and Cox Reference Boyd and Cox2016; Boyd and Dering Reference Boyd and Phil Dering1996; Shafer Reference Shafer2013; Terry et al. Reference Terry, Steelman, Guilderson, Phil Dering and Rowe2006; Turpin Reference Turpin and Perttula2004).

Figure 4. Map of the Lower Pecos Cultural Area indicating the geographic extent of PRS pictographs.

The Archaic period in the Lower Pecos lasted from about 7550 cal BC to AD 650, ending with the introduction of ceramics and the bow and arrow (McCuistion Reference McCuistion2019; Turpin and Eling Reference Turpin and Eling2017). It refers to an archaeological culture defined by a mobile, foraging subsistence pattern consisting of a broad diet of seasonally available wild plants and small game. During the entire history of the region, Archaic period inhabitants were hunters of game, gatherers of wild plants, and fishers (Dering Reference Dering1999). About 4,000 years ago, these foragers began transforming the Lower Pecos region into a painted landscape. The complex murals they created are changing our perception of the past and providing a window into the lifeways of Archaic period people living millennia ago in the Lower Pecos.

The Pecos River style (PRS) is by far the most abundant and visually impressive rock art in the region (Kirkland and Newcomb Reference Kirkland and Newcomb1967). Easily recognized by its multicolored designs and striking anthropomorphic (humanlike) and zoomorphic (animal-like) figures, PRS murals are often ambitious in their scale and deliberate in their execution (Supplemental Figure 1). They are the defining archaeological phenomenon of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands.

Pecos River Style

We know of more than 300 sites containing PRS imagery north of the Rio Grande. South of the river in Coahuila, Mexico, 35 murals have been identified, but there are likely far more in the secluded canyons of the Serranías del Burro (Turpin Reference Turpin2010:41). Direct dates obtained for four PRS figures exhibiting speech-breath range from 1700 BC to AD 600, placing production of the speech-breath motif within the Middle to Late Archaic periods (Steelman, Boyd, and Allen Reference Steelman, Boyd and Allen2021; Steelman, Boyd, and Bates Reference Steelman, Boyd and Bates2021).

PRS panels range considerably in size and complexity. Some are quite small, less than a meter in length and height, and contain only a few figures. Others span up to 150 m long and 15 m tall, and they contain hundreds of figures. Using a digital microscope, Boyd has analyzed 525 locations of intersecting paint layers across six sites. Almost 98% of the locations analyzed follow a strict painting order. Artists applied black paint first, followed by red, then yellow, and finally white. As a result, elements of one figure are painted over and under elements of another figure, weaving them together to form a complex composition. The painting sequence reveals a sophisticated network of relationships within and among rock art figures at a single site. The larger context of mural stratigraphy provides evidence for deliberately planned and executed compositions (Boyd and Cox Reference Boyd and Cox2016).

Pictographic elements in PRS murals include anthropomorphs, zoomorphs, a wide range of geometric imagery, and enigmatic figures that are not identifiable as either human or animal. Anthropomorphs are the most frequently depicted element. They typically range in size between 1 and 2 m; however, some are monumental, towering more than 6 m tall. The most frequently depicted animals in PRS paintings are deer and felines; images of canines are rare, and bear are conspicuously absent from the assemblage. Birds are present but are usually small in size. We often encounter sinuous, snakelike figures, and some imagery resembles insects, such as caterpillars, dragonflies, and moths or butterflies.

As with Mexica pictography from central Mexico (see Boone Reference Boone, Bedos-Rezak and Hamburger2016:33), Pecos River paintings are ideoplastic and accretive. Although images may bear some resemblance to what they signify, they are not realistic reproductions of things perceived by sight. Instead they are conventional signs that serve as graphic abstractions of divine and mortal beings, things, places, sensations, and experiences. Production of the PRS images was an accretive process. Human and animal forms provide a framework to which artists added semantically charged visual attributes, selecting from a wide range of meaning-filled pictographic elements to construct a message. Among anthropomorphs, these elements include headdresses of varying types; adornments attached at the wrist, elbow, waist, or hip; and paraphernalia, such as atlatls (spear-throwers), darts, staffs, and rabbit sticks. The attributes function as a graphic vocabulary, and their arrangement in the mural, not unlike syntax, conveys meaning.

Archaic Core

In 1974, J. Charles Kelley (Reference Kelley, King and Traylor1974) identified parallels between PRS portrayals of anthropomorphs with their distinctive attributes and accoutrements and the elaborate codex depictions of Mesoamerican warrior-hunter deities. Based on these parallels, he suggested that PRS anthropomorphs represent deities or their deity surrogates.

Building on more than 25 years of research, Carolyn Boyd also has identified similarities between Mesoamerican symbolism and PRS iconography (Reference Boyd1996, Reference Boyd, Chippindale and Taçon1998, Reference Boyd2003, Reference Boyd2010, Reference Boyd and Shafer2013, Reference Boyd, Abadía and Porr2021; Boyd and Cox Reference Boyd and Cox2016). Her research reveals patterns in PRS imagery that correspond in detail to the myths and rituals of Uto-Aztecan-speaking peoples, most notably the ancient Aztec (Nahua) and the present-day Huichol. These patterns formed the basis of Boyd and Cox's (Reference Boyd and Cox2016) interpretation of the White Shaman Mural, which they propose is a complex visual narrative detailing the birth of the sun and the establishment of time. Unlike Kelley, who attributed these parallels to the diffusion of ideas from Mesoamerica to the Lower Pecos, Boyd ascribes them to the existence of a more ancient, highly complex, and widely shared cosmovision.

Scholars long have maintained that concepts at the core of Mesoamerican religious traditions have persisted across time and across cultural, linguistic, and geographical boundaries (Gossen Reference Gossen and Gossen1986:5–8; Joralemon Reference Joralemon1976:58–59). These perceptions of reality are of tremendous antiquity, dating to at least the Archaic and perhaps as old as the earliest migrations into North America (López Austin Reference López Austin1997, Reference López Austin, Broda and Báez-Jorge2001; Rice Reference Rice2020). According to López Austin (Reference López Austin, Broda and Báez-Jorge2001:59) these enduring concepts formed a “núcleo duro” (hard core) with elements persisting into today's Indigenous communities despite the tremendous impact of the Spanish conquest. Although Boyd does not claim that the canyons of southwest Texas and northern Mexico are the birthplace of these concepts, she does suggest that Archaic period rock art in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands may contain their oldest surviving and documented graphic expressions.

Native American peoples, north and south of the U.S.–Mexico border, perceived a universe in which a vital life force or essence imbues all things, including art (Cajete Reference Cajete1994; Maffie Reference Maffie2014:21–22). Boyd has argued that the artists of the PRS murals shared in this perception of reality (Boyd Reference Boyd, Abadía and Porr2021; Boyd and Cox Reference Boyd and Cox2016). She maintains that PRS anthropomorphic figures represent ancestral deitiesFootnote 3 or mythological characters, and like later Mesoamerican artists, PRS artists animated and differentiated these characters by means of semantically charged attributes, such as colors, body adornments, paraphernalia, and body postures. One of the most ubiquitous attributes of PRS anthropomorphs is the subject of this article: speech-breath.

Methods and Results

Since 2016, personnel at Shumla Archaeological Research & Education Center (www.shumla.org) have conducted baseline documentation of 233 sites in Val Verde and Terrell County, Texas. More than half of these sites contain PRS imagery. Shumla's baseline documentation includes production of 3D models using structure from motion (SfM), high-resolution GigaPanoramas of the murals and a georeferenced, searchable iconographic database (Koenig et al. Reference Koenig, Castañeda, Roberts, Roberts, Boyd and Steelman2019). The iconographic database reports the presence or absence of physical attributes associated with anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures, including the presence or absence of speech-breath.

Within the PRS sites documented by Shumla, we identified 90 figures displaying speech-breath distributed across 30 sites in the region, including sites along the Devils River, Pecos River, and the Rio Grande (Supplemental Table 1). Of these occurrences, 69 are associated with anthropomorphs and 21 with zoomorphs, including felines (8), deer (9), snakes (2), canine (1), and one unidentified quadruped. For each, we recorded the color, shape, arrangement, and action of the graphic device. We also documented information about the anthropomorph or zoomorph displaying speech-breath and examined the broader graphic context, noting interactions between the speech-breath attribute and other imagery in the mural. We began our study with a formal analysis of the artistic or mark-making process used by artists to create graphic devices denoting speech-breath.

Artistic Process

Every mural is first conceived in the mind of the painter, but the physical painting can only begin by selecting a method of application. To produce speech-breath, artists chose two types of application: (1) casting paint and (2) painting directly on the rock panel with a brush tool. Direct contact with the rock wall via a paintbrush was the dominant way of composing speech-breath in PRS pictography. Artists selected their paintbrushes, such as a brush made from supple animal hair versus coarse plant fibers, according to the desired shape, size, and texture of speech-breath. For splatter painting, artists stood near the wall, casting paint with energetic movements onto the rock support. Density, direction, and path took precedence over the creation of individual marks or shapes.

Color

Artists of PRS paintings used a range of earth colors. Red paint varies from purplish red to reddish orange, and yellow from bright yellow to almost brown. White paint ranges from light gray to pure white, and black from blue black to dark gray. For this study, we categorized speech-breath color simply as black, red, yellow, or white. Overwhelmingly, red was the color of choice for the artist in the production of speech-breath. Of the 90 figures analyzed, 87 have red speech-breath. The three outliers combine red with either black or yellow. We did not identify any figures with white speech-breath.

Shape

Speech-breath in PRS pictography presents in two ways: dots and lines (Figure 2a–h). In some cases, artists combined dots and lines to form multicomponent speech-breath. Dots include splatter paint, empty spheres, and infilled circles of varying sizes and application methods. Lines include unbroken or dashed lines and straight or undulating lines. Of the 90 speech-breath examples identified, 69 comprise or include dots. They were the predominant shape used by PRS artists in the production of speech-breath for anthropomorphs and deer. In contrast, speech-breath for felines consists of lines almost exclusively.

Arrangement

Artists arranged speech-breath shapes into either loosely organized constellations of marks or tight clusters. We refer to these arrangements as either amorphous or circumscribed, respectively. In amorphous arrangements, shapes are spatially dispersed and lack identifiable boundaries (Figure 2e), as opposed to circumscribed arrangements in which marks are constrained within a defined spatial region. In circumscribed arrangements, shapes radiate outward from the figure's mouth to create an acute angle or are organized into single or multiple rows of dots or lines (Figure 2a, f). With few exceptions, artists arranged shapes in circumscribed clusters. Rarely was the arrangement of shapes amorphous.

Action

We can see the hand of the artists—the physical act of mark-making—in the images they created. Whether produced using aggressive or carefully articulated brushstrokes, the painting reveals the artist's movement. We classified the action engaged in mark-making into two broad categories: measured and forceful. Measured action is reflected in carefully rendered shapes of approximately the same size, typically produced with a soft-bristled brush loaded with paint (Figure 2a–b, e–f). Despite applying paint to an uneven, rough surface, artists created uniform shapes with crisp outlines. Shapes made with measured action rarely overlap.

Forceful action refers to images produced expediently. The artist applied the paint aggressively to the wall, forming dots by jabbing the brush against the rock canvas or rapidly dragging the brush from its point of impact to create a line (Figure 2d, g–h). Forceful dots have frayed edges and frequently overlap, with little effort made to preserve spacing between the shapes. Forceful lines are rough, uneven, and brushy in appearance, suggesting the artist's choice of a paintbrush made from stiff plant fibers. The direction of the brushstroke is often apparent. Paint was applied thickly at the point of initial contact with the wall, but as the brush was pulled to form the lines, the paint was expended and the mark dissipated. Speech-breath created through casting paint conveys a dispersed and chaotic energy that has a strong directional force, extending for large portions of the panel and often overlapping with other figures in the scene (Figure 2g). This quick and forceful way of applying marks conveys speed and movement.

Speech-breath for anthropomorphs and for deer exhibits measured and decisive action. A series of unhurried, precise brushstrokes using a supple paintbrush created these images. However, there are notable exceptions. The painter of an anthropomorph at Cedar Springs (41VV696) created multicomponent speech-breath incorporating expedient dots and splatter paint with a strong directional focus (Figure 2g). Through this mark-making technique, the artist conveys tension and force.

When producing speech-breath for felines, artists often placed less focus on the precision of the shape and more attention on the force and movement of the mark. The path of the brushstroke is often visible, indicating the direction of the action. For example, the speech-breath associated with a feline at Mystic Shelter (41VV612; Figure 2h; Supplemental Figure 2) consists of both short, broad lines and long, thin lines. Our analysis of the brushstrokes indicates that the short lines move toward the face of the feline, and the long, thin lines move in both directions, possibly indicating inhalation and exhalation.

Interaction

The speech-breath of anthropomorphs and zoomorphs often interacts with other imagery in the mural. Examples of interaction include figures with speech-breath facing one another and figures whose speech-breath connects with other anthropomorphs, zoomorphs, or enigmatic imagery (Figure 3). The speech-breath of more than half of the figures interacts with other imagery in the mural.

The artists’ choices in paint application technique, color, shape, arrangement, action, and placement within the mural were intentional. Our analysis identified patterns in these choices, which provide us with important clues not only about the function and meaning of the motif but also about how these marks were meant to be visually read and experienced. Although cosmogonic myths and the Indigenous art of populations living north of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands afford some insights into the significance of breath among these communities, the patterns most closely mirror cosmological concepts of life and creation expressed in the art and myths of Mesoamerica. Even though there are marked cultural differences between nomadic foragers and sedentary agriculturalists, López Austin (Reference López Austin, Broda and Báez-Jorge2001:59) and Rice (Reference Rice2020) remind us that the religious traditions of Mesoamerican agriculturalists were, at least in part, an outgrowth of the worldview of Archaic hunter-gatherers. Rice (Reference Rice2020) notes that some of the cosmological concepts and perceptions of reality may not only be pan-Mesoamerican but also pan-New World. By looking for the similarities and patterns within the diversity, we begin recognizing components of the núcleo duro that are most resistant to change, those that may be pan-New World, such as the breath-soul.

Discussion

Indigenous peoples throughout the Americas place an enormous significance on breath (Cajete Reference Cajete1994; Taube Reference Taube, Fields and Zamudio-Taylor2001). For the Hopi, it constitutes all of life. It is that aspect of humanity that “can experience the first primordium, the totality that existed before their emergence” (Loftin Reference Loftin2003:59). When expressed in ritualized speech and song, breath is a powerful force engaged in both creation and maintenance of the cosmos (Erdoes and Ortiz Reference Erdoes and Ortiz1984; Leeming and Page Reference Leeming and Page2000; McNeley Reference McNeley2009; Tyler Reference Tyler1964). Breath also is intimately associated with the sun and with concepts of an animating life force or soul, which is blown into an infant at birth or conception and provides a vital, enduring connection between the individual, the deities, and all elements of the living world (Cajete Reference Cajete1994; Furst Reference Furst1995; Hubáčková Reference Hubáčková2009; Hultkrantz Reference Hultkrantz1998; López Austin Reference López Austin1988:218; Mathiowetz Reference Mathiowetz2011:299, 740; Newcomb Reference Newcomb1961; Taube Reference Taube, Fields and Zamudio-Taylor2001:102, 105). Stevenson (Reference Stevenson1904:24, 78) reports that the Zuni inhale “sacred breath” from the light of day (sun), but they also transmit sacred breath by blowing upon objects and through “breath prayers” to the gods. The breath of their prayers merge with the breath of the gods (Stevenson Reference Stevenson1904:172). Speech and song transmit this life force to others, mingling with the breath of others and enduring in place to influence those who came after (Houston and Taube Reference Houston and Taube2000:290; Hubáčková Reference Hubáčková2009:92–93). Among the Rarámuri, breath is the soul essence of life, and through it everyone and everything are bound together (Salmón Reference Salmón1999:225).

Mathiowetz (Reference Mathiowetz2011:745) reports that the earliest graphic evidence of the breath-soul in the American Southwest appears in Mimbres art no earlier than AD 1000. By the fourteenth century, however, breath symbolism and its association with the soul and solar forces are evident in the art of the Casas Grandes, Pueblo, and Mimbres cultures (Mathiowetz Reference Mathiowetz2011; Taube Reference Taube, Fields and Zamudio-Taylor2001). Jones and Drover (Reference Jones, Drover, Hedges and McConnell2018) have identified elements in Pueblo III and IV petroglyphs that they associate with breath, and in the 1880s, Alexander Stephen (Reference Stephen and Parsons1936:Figure 350; Figure 1c) documented a Hopi ritualist using lines in a sand painting to denote breath exhaled from felines. Depictions of speech-breath in Archaic period rock art north of the Lower Pecos are rare,Footnote 4 but to the south, in the lowlands of Mexico, Olmec artists began using graphic devices during the Middle Formative (ca. 900–100 BC).

Conventions used to denote vocalization and breath in Mesoamerican iconography included scrolls, dots, or lines emanating from the mouths of humans and animals (Figure 5a–h; Houston and Taube Reference Houston and Taube2000). For example, a Late Classic Maya vessel portrays speech and breath as a single line of dots emerging from the speaker's mouth, and in the Bonampak Murals, a singer glyph incorporates a series of dots to represent the sound of song (Figure 5a–b). Dots combine to take on the form of a speech scroll in Late Postclassic Mixtec codices, as well as in the early post-conquest manuscript Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca (Figure 5c–d). Speech or song scrolls pour forth from the open mouths of both humans and animals at Teotihuacan and in Maya, Mixtec, and Nahua codices (Figure 5e–f). Often these develop into complex motifs, with elements placed inside or affixed to the outside of the volute. Elaborating the form or changing the color of the graphic devices identifies the nature of the portrayed speech activity, such as song or prayer (Hajovsky Reference Hajovsky2015:60). Mesoamerican art also included representations for breath and aromatic fragrances. Breath hovers before the nose or mouth as a single bead or pair of beads in Olmec and Maya art or is elaborated into a complex motif (Figure 5g–h). Hunter-gatherer artists used similar graphic devices to denote speech and breath in murals of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands. In this section, we describe several examples of PRS speech-breath and explore how the marks convey concepts akin to those expressed in Mesoamerican cosmology and iconography.

Figure 5. Mesoamerican speech-breath (drawings by Carolyn E. Boyd): (a) Late Classic Maya dotted speech scroll (after Houston and Taube Reference Houston and Taube2000:Figure 9d); (b) Classic Maya singer glyph, Bonampak Mural (after Houston and Taube Reference Houston and Taube2000:Figure 10b); (c) Late Postclassic Mixtec figure from the Codex Bodley (after Codex Bodley, p. 28); (d) Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca (after Leibsohn Reference Leibsohn2009:Plate 16); (e) Teotihuacan speech scroll, Tepantitla compound (after a photograph by Carolyn E. Boyd); (f) singing and drumming dog from the Codex Madrid (after Codex Madrid, p. 37); (g) Olmec breath bead (after Houston and Taube Reference Houston and Taube2000:Figure 3a); (h) breath bead from Codex Dresden (after Codex Dresden, p. 9b).

Soul Receptacles

The dominant graphic expression used by PRS artists to depict speech-breath was red circles placed before the mouths of anthropomorphs and zoomorphs (Figures 2 and 6). Their choices of color (red), shape (spherical), action (measured), and context (emanating from the mouth) are analogous to Mesoamerican conceptions of the soul expressed through measured breathing, ritualized speech, and song.

Figure 6. Dotted speech-breath associated with a PRS anthropomorph at Parida Cave (41VV187; photo courtesy Shumla Archaeological Research & Education Center).

Mesoamerican people did not perceive the soul as immaterial but as matter with weight and form (Carrasco Reference Carrasco1999:14). Among the Nahua, tonalli—the soul placed in the child's head—was considered hot (Chevalier and Sánchez Bain Reference Chevalier and Bain2003:46) and equated with the color red (Dupey García Reference Dupey García, Garciá and de Ágredos Pascual2018:203–204). The word tonalli is derived from tona, which means “to irradiate or make warm with sun” (Carrasco Reference Carrasco1998:68). Tonalli, as “forces emanating from the gods, were conceived to be round bodies and depicted graphically as circles” (López Austin Reference López Austin1988:210, Reference López Austin2019:25–28). The soul that was ignited in the child's chest, yolia, was considered hot during life. Yolia, along with tonalli, was a vital, animating life force; the word derives from yol, which means “life” (López Austin Reference López Austin1988:230). Yolia refers to the physical heart and its animating qualities. As with tonalli, yolia was described as round, and by virtue of its heat and association with life, it was equated with red (Furst Reference Furst1995:18).Footnote 5 Breath expressed to produce ritualized speech or song conveyed tonalli and yolia (Furst Reference Furst1995:156). Among the principal goals of these orations were to create, sustain, or renew order in the cosmos. Vocalizations produced through measured breathing, akin to the measured breathing required to kindle a fire, “transmit creative and transformative energy from humans to the cosmos” (Maffie Reference Maffie2014:287).

We propose that carefully formed red dots emanating from the mouths of anthropomorphs and zoomorphs in PRS pictography are graphic devices denoting visible breath and the soul: hot, solar life forces expressed through breath in the form of speech and song (Figure 6). The red dots are soul receptacles, the material presence of breath. The measured action conveyed by artists through the mark-making process reflects the measured breathing that transmitted vital life forces from humans to the cosmos.

Soul Sacrifice

In the Fate Bell Shelter Mural (41VV74), two anthropomorphs stand in profile with their heads turned sharply upward (Figure 7). Other than the interior portion of their bodies, they are mirror images of one another, similarly adorned and wielding similar paraphernalia. They flank a tall, frontally facing anthropomorph, their arms reaching forward as if in supplication to this figure. A stream of red dots pours forth from the mouths of the two flanking figures at the same angle and coalesce around the U-shaped head of the central anthropomorph, which stands 2.3 m tall. The red dots appear elongated, as if in motion. The artist applied paint thickly and with urgency, allowing the marks to accumulate in an upward path. A large ovoid shape intersects with the central anthropomorph's head. This is the distal end of an accoutrement referred to in PRS iconography as a power-bundle.Footnote 6 Using compositional arrangement, action, and symmetry, the artist directed the viewer's attention to this clear focal point.

Figure 7. Fate Bell Shelter (41VV74). Flanking anthropomorphs exhale heated offerings in the form of speech or breath to the central figure (drawing by Carolyn E. Boyd). (Color online)

In Mesoamerican art, speech or breath scrolls emanating from the mouths of figures with sharply upturned heads graphically represented the exhalation of breath (Saturno et al. Reference Saturno, Taube and Stuart2005:22). The transmission of breath and acts of speech were closely aligned with acts of sacrifice and self-sacrifice, all essential components of the creation process. Humans were obliged to worship the creators by reproducing the primal sacrifice—the gifting of breath from the gods to humanity—through song and prayer (Olivier Reference Olivier and Besson2003:12–13). Fragrant breath was a favorite food of the gods and of the ancestors (Taube Reference Taube2004:73). It denotes soul sacrifice in the form of speech and song rising skyward as a spiritually heated offering (King Reference King, Boone and Mignolo1994:107).

A repeated theme in Maya art is the portrayal of a central figure receiving offerings from flanking supplicants. The supplicants could be ancestors, deities, or subordinates (Carter Reference Carter, Carter, Houston and Rossi2020:101). For example, on Monument 65 at Kaminaljuyu, a Late Preclassic sculpture illustrates a frontally facing central figure flanked by two individuals offering themselves in supplication. Kaplan (Reference Kaplan2000:191) identifies the central figure as a “world or cosmos creator and sustainer” and the flanking figures as twin proxies of the central figure. Their sacrifice constitutes the primordial sacrifice that gave birth to creation, the social order, and order in the cosmos. Creation required both breath and autosacrifice (Maffie Reference Maffie2014:286).

The Fate Bell Shelter composition vividly expresses this concept of adoration, supplication, and sacrifice of the breath-soul. The two flanking figures, virtually identical in posture and physical attributes, may represent ancestral spirits or deities exhaling fragrant breath as a heated offering to the central figure.

Transmitting Vital Forces

In PRS pictography, speech-breath frequently interacts with other imagery in a mural. Dots and lines expressed from one figure purposefully extend to touch and interact with another, sometimes creating an apparent chain reaction. When this occurs, the speech-breath of one figure triggers speech-breath in another or, in some cases, several figures, including nonfigurative imagery, such as weaponry and accoutrements. An example of this is found in the 30 m long mural of Rattlesnake Canyon Shelter (41VV180; Figure 8; Supplemental Figure 1). Here, a seemingly simple, small, red anthropomorph standing only 28 cm tall is portrayed with a headdress resembling a single rabbit ear. It wields no weaponry and, other than its headdress, lacks body adornments and paraphernalia. Its head is in profile, facing a larger (1.3 m tall) anthropomorph wearing an elaborated version of the rabbit-ear headdress. The small anthropomorph expels a long, narrow stream of tightly clustered, often overlapping, and highly energized red dots. These extend into the body of the taller figure, which releases a gentle stream of precisely painted red dots toward an atlatl in its right hand. A stream of red dots flows from the distal end of a dart loaded in the atlatl. In the anthropomorph's opposite hand is a power-bundle, which also emits a stream of measured, red dots.

Figure 8. Rattlesnake Canyon (41VV180): transference of animating energies through the forceful breath of the small, red anthropomorph into the tall black and red figure wielding an atlatl and power-bundle (drawing by Carolyn E. Boyd). (Color online)

In Mesoamerican thought, powerful animating forces could interact with and be transferred between people and material objects through speech and breath (Colas Reference Colas2011:16; López Austin Reference López Austin1988:220; Maffie Reference Maffie2014:14).Footnote 7 Central Mexican sources liken speech and breath to wind, which was believed to be a primordial force. It was “the tool by which the highest god creates” and was an instrument of power (Brundage Reference Brundage1982:76). In the Nahua story of creation, Ehecatl, the god of Wind, “arose and exerted himself fiercely and violently as he blew,” instilling movement and life into the newly born sun (Maffie Reference Maffie2014:286). His “hurricane breath” and his “stentorian voice” transmitted the vital forces required to put the sun and time into motion (Brundage Reference Brundage1982:72, 76).

The Rattlesnake Canyon Mural example is reminiscent of the Mesoamerican stories of creation in which ancestral deities instigated movement and the transference of creative energies through hurricane-force winds and powerful voices. Artists of the mural conveyed dynamic movement through the mark-making process. The tightly clustered dots ejected from the mouth of the small anthropomorph convey intensity and movement, like the strong voice and violent wind that transmitted the forces required to put the sun into motion. We are not suggesting that the Rattlesnake Canyon Mural portrays this mythic event, but that the action instilled in the graphic device expresses the concept of violent wind, powerful voice, and the transference of vital forces. The creative and transformative energies infuse the larger anthropomorph, which then transmits the animating force into its accoutrements and weaponry. Now, however, the movement is measured, lacking the ferocity of the initiating action.

Mesoamerican speech scrolls not only graphically represented communication and the transmission of animating energies but also served to connect actors in visual narratives. For example, Hajovsky (Reference Hajovsky2015:64) writes, “In Codex Selden the oracle Lady 9 Grass speaks through the deer headdress of Lord 10 Wind, which connects to Lady 6 Monkey, the protagonist of the story.” The line of speech volutes connected the actors in the narrative, indicating interaction between and among characters in the story. Like the artist of Codex Selden, the artist of the Rattlesnake Canyon Mural used the speech-breath element to bind together figures into an ever-expanding narrative containing 15 anthropomorphs and one zoomorph exhibiting speech-breath (Supplemental Figure 1).

Dialogic Interactions

In addition to the transference of forces between multiple beings and objects, we have identified the exchange of breath or words between two figures facing each other in profile. One of the most striking examples, found at Frost Felines (41VV2326), portrays two anthropomorphic figures standing approximately 1 m tall and facing one another (Figure 9). Both possess feline attributes. The figure on the right holds an elaborate power-bundle and a spear-thrower loaded with a fletched dart. On its right arm is a wrist adornment, and on its left are lines indicating the presence of an elbow adornment. The anthropomorph on the left is predominantly infilled and lacks paraphernalia and body adornments. Both anthropomorphs have open mouths. Speech-breath, in the form of large, well-defined red dots, floats between the two figures. The dots are spaced at consistent intervals and maintain about the same size from one figure to the other, indicating a relationship between the two facing figures. The shape, color, and context of the speech-breath of this PRS example allude to dialogue and the transmission of energies between two entities.

Figure 9. Frost Felines (41VV2326): two anthropomorphs engaged in speech or singing (drawing by Carolyn E. Boyd). (Color online)

In Mesoamerican codices, speech glyphs could indicate dialogic interaction between individuals facing one another in profile (Boone Reference Boone, Bedos-Rezak and Hamburger2016:42; Hajovsky Reference Hajovsky2015:63).Footnote 8 For example, in the colonial period manuscript Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca, wispy speech scrolls link two Chichimec men inside the origin cave of Chicomoztoc. Outside the cave, Chichimec warriors engage in conversation with Toltec holy men (Leibsohn Reference Leibsohn2009:43, 119–120, Plate 5). However, in most precolumbian manuscripts, speech glyphs conjured the prayers or songs experienced during the events represented in the pictorial narrative (Hajovsky Reference Hajovsky2015:66–67). That which was seen was simultaneously heard. Houston and Taube (Reference Houston and Taube2000:263) suggest that speech scrolls signaled the presence of sensations that a person would generally only receive by the ear. Sight and hearing were linked in a “near-synaesthetic fashion,” whereby “stimulus in one modality—sight—triggered perception in another—hearing” (Houston and Taube Reference Houston and Taube2000:261). In other words, images of speech scrolls were loaded with sound; they carried the voice and breath of the ancestors engaged in the mythic events portrayed in visual narratives.

We propose that the red dots passing between the two figures at Frost Felines represent measured words of ritualized speech, soul-breath loaded with potency and with sound. Rather than rising heavenward, measured words pass between them. The dots are large, heavy, and pregnant with energy. It is also possible that the intended recipient of the soul-breath is the power-bundle, or perhaps it is the power-bundle that is the conveyor of vital forces. Unlike speech-breath formed from lines, it is difficult to determine the path of speech-breath formed from dots.

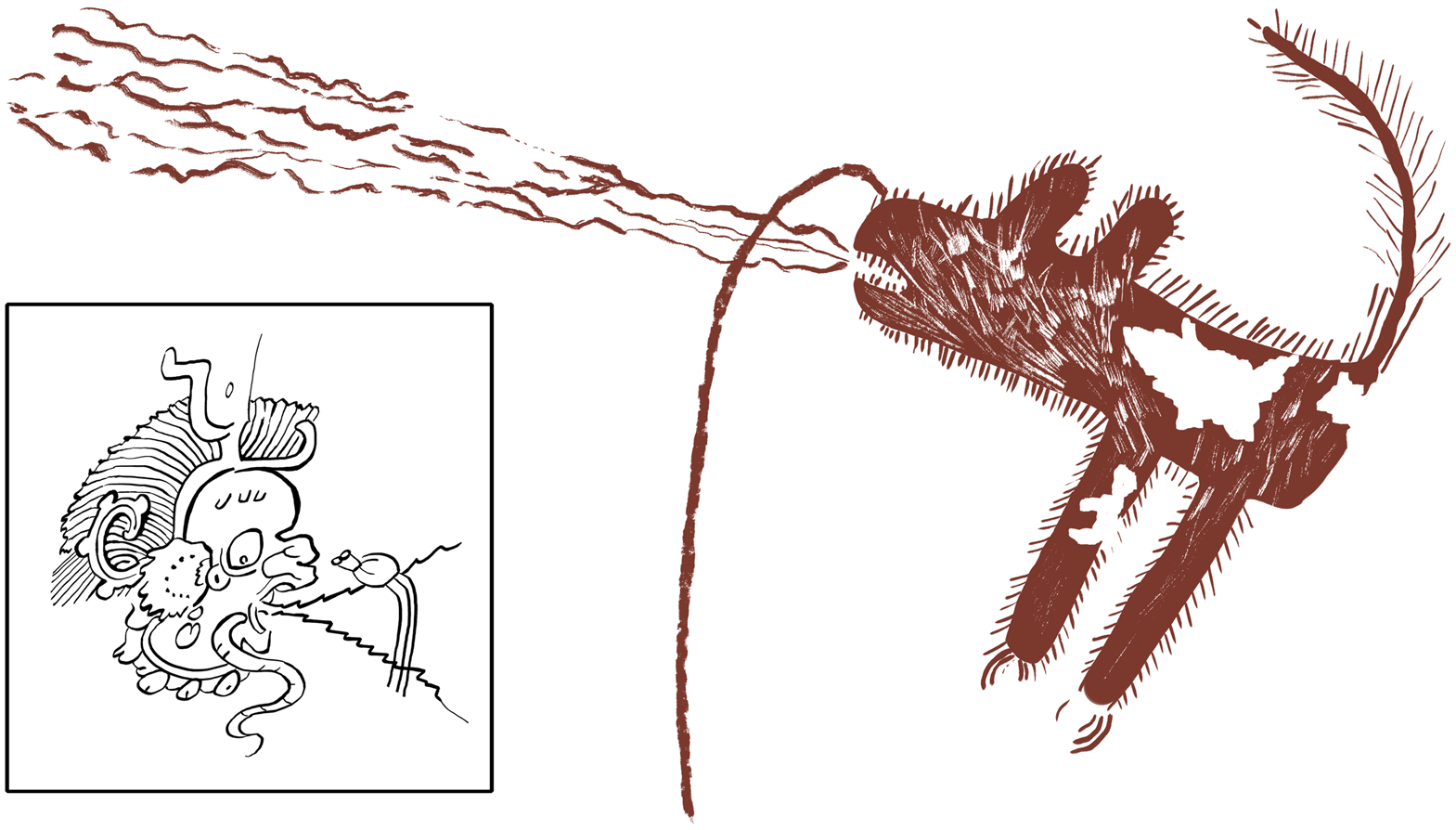

Thunderous Sounds

At Halo Shelter (41VV1230), a red two-legged feline (60 cm long) emits a series of long, undulating red lines from its toothed mouth (Figure 10). The arrangement of the speech-breath lines forms a tightly constrained, acute angle. The feline's fur is standing on end, and its tail arches over its back. A long, thick red line emerges from its nose before turning downward to intersect the undulating lines below. The painting of the feline has been heavily abraded and incised. This form of Indigenous postpainting modification is common in the Lower Pecos, but it is especially pronounced on this figure.

Figure 10. Halo Shelter (41VV1230; drawings by Caroyln E. Boyd): thunderous sound and breath of a feline; (inset) Chaak, lightning and rain god of the Classic Maya (after Kerr Reference Kerr2021:K2208). (Color online)

In Mesoamerica, speech, song, and breath glyphs appear not only with anthropomorphs but also with zoomorphs.Footnote 9 The shape and elaboration of glyphs, however, are context dependent, varying according to the type of figure with which they are associated (Colas Reference Colas2011:16). For example, at Teotihuacan the scrolls of birds differ from the scrolls of humanlike figures. Hajovsky (Reference Hajovsky2015:60) states that, although the animating power of wind lies behind the speech glyph, its identification as breath, smoke, mist, sound, or smell changes according to context and qualifying attributes. By adding elements to the glyph or by changing its shape or color, the artist clarified the type of speech act that the glyph engenders.

For ancient Mesoamerica, jaguars and pumas are closely associated with concepts pertaining to the underworld, caves, and rain; their mighty roar is reminiscent of reverberating thunder (Olivier Reference Olivier and Besson2003:98, 106). Houston and Taube (Reference Houston and Taube2000:280) propose that, in Classic Maya art, undulating or jagged lines represent powerful, rumbling sounds. They offer as an example images of Chaak, the rain and lightning god, whose thunderous voice spews forth from the deity's gaping mouth as undulating and zigzag lines (Figure 10 inset).

As in Mesoamerican iconography, the shape and elaboration of PRS speech-breath are context dependent and vary according to the figure with which it is displayed. We identified eight feline figures with speech-breath in PRS pictography. In each case the artist used red lines as opposed to dots to denote sound, breath, or smell. We suggest that the long, undulating lines expressed from the Halo Shelter feline represent the cat's thunderous roar. The single red line projecting from the feline's nose might be analogous to graphic devices denoting nasal exhalation or blood.

As opposed to dots and lines emanating from the mouth, nasal exhalations in Mesoamerican iconography commonly hover before the nose (Houston and Taube Reference Houston and Taube2000:265). In the image of Chaak discussed earlier, these exhalations are graphically portrayed by the lines descending from a nasal element resembling a shuttlecock (Kettunen Reference Kettunen2005:116). It is also possible that the red line represents blood flowing from the nose of the feline. Blood, like breath, symbolized the essence of life. Cosmogonic myths in Mesoamerica commonly feature the transformation of humans and gods into jaguars. Bleeding from the nose, whether through bloodletting or trance, was associated with such transformations. Given the two-legged attribute of the Halo Shelter feline, the likelihood of the imagery representing human–jaguar transformation is plausible.

Conclusions

As López Austin notes, “In studying systems of thought, one can never expect to find a total congruence, an unchanged tradition, nor all the information. One looks for clues. Finding the keys to indigenous thought allows the necessary hypotheses to be formulated” (Reference López Austin1993:310). The importance of breath and of its association with an indwelling, solar life force is widespread temporally and geographically. Outside the Lower Pecos, the oldest graphic codification of this concept is in the artistic traditions of Mesoamerica. It is here that we find examples closest in age, proximity, and abundance to PRS pictography. And it is here that we find the clues needed to formulate hypotheses about the function and meaning of the speech-breath motif.

The choices made by PRS artists to denote speech-breath reflect their cosmology and the framework of ideas and beliefs through which they interpreted and interacted with the world. It was a reality in which speech and song were intimately tied to creation and human origins, to the establishment of all things. Color, shape, and context infused graphic devices with meaning, sound, and life. The color red vitalized speech-breath with hot, solar life forces, the warm breath and blood of living beings. With intentionality, artists incorporated movement and emotion into images through the choice of tool and technique. Measured dots, pregnant with sound and potency, deliver ritualized speech, song, or poetry heavenward as heated fragrant offerings. Highly energized red lines convey thunderous sounds that reverberate across the mural and into the ears of onlookers. Through the mark-making process, artists infused images with forceful winds that put creation and time into motion. Speech-breath transmits, combines, and multiplies vitalizing forces. It connects, directs, and organizes compositions. And, for those who were adept at reading the art and were familiar with its stories, speech-breath triggered the senses such that, what one saw, one also heard, felt, and smelled.

We suggest that the artists of the Lower Pecos lived in a universe in which everything was alive and equally real. In this perception of reality, everything—including art—possessed the ability to make things happen. The role of the Lower Pecos painter was an embodied one, translating the sensory experience into a system of ordered movements and expressions. In the process of painting, these speech-breath patterns were activated on the panel, bringing concepts of body and creation into the present for the viewer who experiences them. PRS murals were not passive backdrops painted along shelter walls, but rather active mechanisms that “spoke” or “sang” through oration and performance. Viewers experienced events told through the images as if occurring in the present. For Indigenous communities today, the art is not simply a reflection of their past heritage but is part and parcel of their contemporary lives. Images continue to be animated, empowered, and vivified.Footnote 10 And, because of this, the ancestors continue to provide spiritually heated offerings—soul sacrifices—through images of speech and breath infused with sound and scent.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Geographic Society for its support of the rock art documentation project that made this research possible. We are grateful to Shumla Archaeological Research & Education Center for its invaluable assistance and ongoing work in the Lower Pecos. A special thanks to Jean-Michel Geneste and Paul S. C. Taçon for sharing examples of speech-breath from their rock art assemblages, and to Alfredo López Austin for sharing helpful insights into the shape of tonalli. We would like to thank Nancy Kenmotsu, Nicholas Carter, Jessica Hamlin, Charles Lohrmann, Elton and Kerza Prewitt, Missy Harrington, J. Phil Dering, and Bennett Dampier for their helpful comments and edits of this article. We greatly appreciate the constructive critiques offered by the reviewers of our original manuscript. Most especially, we thank the landowners and site managers who graciously allowed us access to the sites and for their ongoing stewardship of this remarkable legacy.

Data Availability Statement

Data are archived at Shumla Archaeological Research & Education Center and available from the corresponding author on request by e-mail.

Supplemental Material

To view supplemental material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2021.47.

Supplemental Table 1. Speech-Breath Data for PRS.

Supplemental Figure 1. Rattlesnake Canyon (41VV180). GigaPan photo by Rupestrian Cyberservices (courtesy of Shumla Archaeological Research & Education Center).

Supplemental Figure 2. Mystic Shelter Feline (41VV612; photo courtesy of Shumla Archaeological Research & Education Center).