Abstract

Objectives

Few studies have evaluated Nagin and Pogarsky’s (2004) proposed distinction between impulsivity and discounting. This study evaluates and expands upon their framework to consider distinct discounting rationales, perceived age-at-death (PAAD) and expected social value (ESV), and whether impulsivity conditions the effects of these discounting rationales on offending; both in the short-term and over time.

Methods

Negative binomial and group-based trajectory modeling strategies are used in conjunction with a sample of high-risk males from the Pathways to Desistance Study to assess Nagin and Pogarsky’s framework.

Results

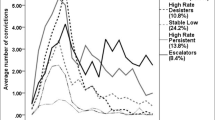

In the negative binomial models, impulsivity and PAAD influence offending, while ESV does not. Impulsivity level also does not condition the effects of discounting. In the trajectory models, PAAD and impulsivity influence offending, while ESV does not. Here, impulsivity level moderates the effect of ESV, but not PAAD.

Conclusions

Findings support Nagin and Pogarsky’s general framework of inter-temporal choice but also encourage scholars to focus more closely on the diverse rationales for temporal-orientation. Further, consideration of these mechanisms within a developmental perspective is necessary. Implications for theory and future research are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

An inter-temporal choice is a decision in which the costs and/or benefits occur at two different points in time.

Nagin and Pogarsky (2001) provided an example of how discounting could affect the perceived cost of crime from a deterrence perspective. Imagine an individual is faced with a fine. If the individual devalues paying the fine in the future (e.g., paying the fine 30 days from now relative to paying today), the fine may be perceived as less severe as a result of the individual’s tendency to discount future costs. The same logic can be applied to delayed rewards, such as perceived future benefits, which will be our focus in this manuscript.

Impulsivity is often considered one dimension of self-control. The low self-control-offending relationship also provides general support for the impulsivity-offending relationship (e.g., Arneklev et al. 1993; Cochran et al. 1998; Grasmick et al. 1993; Hay 2001; Nagin and Paternoster 1993; Piquero and Tibbetts 1996; Pratt and Cullen 2000).

A discount factor \({\delta }_{t}={\left(\frac{1}{\left(1+r\right)}\right)}^{t}\) allows a weight to be added to future costs or benefits. The weight is dependent on the number of time periods a cost/benefit is delayed (t) and an individual’s discount rate (r). The discount rate is the extent to which a person decreases future values. Those with a high discount rate are more present oriented and devalue the future (see Nagin and Pogarsky 2001).

Missing cases are the result of missing values on the following variables (frequency and percentage in parentheses): impulsivity (3, < 1%), PAAD (72, 6%), ESV (9, < 1%), certainty (2, < 1%), personal rewards (1, < 1%), neighborhood conditions (2, < 1%), family arrest (3, < 1%).

To create annual recall measures, 6-month consecutive waves were combined, where any indication of a crime in either of the 6-month recall periods was considered an indication of that crime for the year. This is often done with the Pathways data to create uniform recall periods (Monahan et al. 2009, 2013; Piquero et al. 2012).

To create annual follow-ups, again, consecutive 6-month waves were combined for years 1, 2, and 3 by using a summated average of non-missing values. This measure was included as a control variable in the Year 1 analysis.

Additional post-estimation procedures were used to assess the accuracy of the trajectory model. First, the average posterior probability of group assignment (AvePP) is reported. Nagin (2005, p. 88) suggests all groups reach a minimum AvePP threshold of .7, which all groups exceed (ranging from .85 to .96). Second, the odds of correct classification (OCC) was evaluated. The OCC is the ratio of the odds of a correct classification into group j based on the AvePP value, to the odds of correctly classifying individuals into group j based on the estimated proportion of the sample belonging to group j. The OCC values in our model are well above 5 (group values range from 11 to 226), which Nagin (2005, p. 89) suggests is the threshold required for a model to demonstrate high assignment accuracy.

Our PAAD measure is open-ended. Respondents indicated their PAAD without an age threshold referenced in the question. This operationalization differs from measures available in the Add Health data (Brezina et al. 2009; Borowsky et al. 2009; Nguyen et al. 2012), which asks respondents to indicate: (1) their “probability of being killed by 21”; or their “chances of living to age 35.” While there are various ways to operationalize and conceptualize PAAD, the measures and studies that have implemented them all similarly focused on temporal decision-making and individuals’ views of their future.

The forthcoming results do not change substantively when evaluating the expected number of years left (PAAD – current age) rather than the PAAD.

Analyses evaluating the relationships between baseline covariates and Year 1 offending have a smaller sample size than the trajectory analyses. This is because inclusion in the negative binomial models requires respondents to be a part of the analytic sample required for the trajectory analyses and offending information at the first annual follow-up. Descriptive statistics for this subsample are available upon request.

We also considered analyzing only the top 25% of the impulsivity scale as “high impulsivity” and the bottom 25% of the impulsivity scale as “low impulsivity.” When doing this, results are substantively similar. However, we decided against this because restricting the sample causes at least one of our SRO trajectory groups to fall below 5% of the sub-sample and meaningful comparisons can no longer be made between groups (Nagin 2005).

The maximum changes per wave (9 = (|6–1| +|1–6| +|5–2| +|2–5| +|4–3| +|3–4|) / 2) times the number of wave transitions (7).

A total of 6 maximum rank changes per wave, times 7 transitions.

To put these values into context, a score of 9 indicates an individual’s perceived likelihood that the events would happen to them was “good = 3” and he perceived these events as at least “somewhat important = 3,” on average. A score of 25 suggests all events were perceived as “very important” and having “excellent” likelihoods of occurring.

This moderation finding is consistent if impulsivity is dichotomized at different thresholds or if impulsivity is measured continuously.

There is no evidence that these findings are the result of multicollinearity given the weak-to-moderate correlations among temporal orientation measures: (Impulsivity-PAAD r = −0.14; Impulsivity-ESV r = −0.14; PAAD-ESV r = 0.34).

All controls are have been omitted from output for parsimony. Full results are available upon request.

Predicted probabilities were computed by hard classifying individuals into trajectories and conducting multinomial logistic estimation.

References

Abderhalden FP, Baker T, Gordon JA (2020) Futurelessness, risk perceptions, and commitment to institutional rules among a sample of incarcerated men and women. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 64:591–608

Ainslie G (1975) Specious reward: A behavioral theory of impulsiveness and impulse control. Psychol Bull 82(4):463–496

Åkerlund D, Golsteyn BHH, Grönqvist H, Lindahl L (2016) Time discounting and criminal behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113(22):6160–6165

Allison PD (2009) Fixed effects regression models. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Anderson E (1999) Code of the street. W.W. Norton & Company, New York, NY

Anderson LS, Chiricos TG, Waldo GP (1977) Formal and informal sanctions: a comparison of deterrent effects. Social Problems 25:103–114

Anwar S, Loughran TA (2011) Testing a Bayesian learning theory of deterrence among serious juvenile offenders. Criminology 49(3):667–698

Arneklev BJ, Grasmick HG, Tittle CR, Bursik RJ Jr (1993) Low self-control and imprudent behavior. J Quant Criminol 9(3):225–247

Baumeister RF (2002) Yielding to temptation: Self-control failure, impulsive purchasing, and consumer behavior. J Consum Res 28(4):670–676

Baumeister RF, Tierney J (2012) Willpower: rediscovering the greatest human strength. Penguin, New York, NY

Bechtold J, Cavanagh C, Shulman EP, Cauffman E (2014) Does mother know best? Adolescent and mother reports of impulsivity and subsequent delinquency. J Youth Adolesc 43(11):1903–1913

Becker GS (1968) Crime and punishment: An economic approach. J Polit Econ 76:169–217

Belin D, Mar AC, Dalley JW, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ (2008) High impulsivity predicts the switch to compulsive cocaine-taking. Science 320(5881):1352–1355

Black RA, Serowik KL, Rosen MI (2009) Associations between impulsivity and high risk sexual behaviors in dually diagnosed outpatients. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 35(5):325–328

Blokland AA, Nagin D, Nieuwbeerta P (2005) Life span offending trajectories of a Dutch conviction cohort. Criminology 43(4):919–954

Borowsky IW, Ireland M, Resnick MD (2009) Health status and behavioral outcomes for youth who anticipate a high likelihood of early death. Pediatrics 124(1):81–88

Brezina T, Tekin E, Topalli V (2009) Might not be a tomorrow: A multimethods approach to anticipated early death and youth crime. Criminology 47:1091–1129

Burke JD, Loeber R, White HR, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Pardini DA (2007) Inattention as a key predictor of tobacco use in adolescence. J Abnorm Psychol 116(2):249–259

Burt CH, Simons RL, Simons LG (2006) A longitudinal test of the effects of parenting and the stability of self-control: negative evidence for the general theory of crime. Criminology 44(2):353–396

Cacioppo JT, Petty RE, Feinstein JA, Jarvis WBG (1996) Dispositional differences in cognitive motivation: The life and times of individuals varying in need for cognition. Psychol Bull 119(2):197–253

Caldwell RM, Wiebe RP, Cleveland HH (2006) The influence of future certainty and contextual factors on delinquent behavior and school adjustment among African American adolescents. J Youth Adolesc 35(4):591–602

Chao LW, Szrek H, Pereira NS, Pauly MV (2009) Time preference and its relationship with age, health, and survival probability. Judgm Decis Mak 4(1):1–19

Chen P, Vazsonyi AT (2011) Future orientation, impulsivity, and problem behaviors: A longitudinal moderation model. Dev Psychol 47(6):1633–1645

Clarke D (2006) Impulsivity as a mediator in the relationship between depression and problem gambling. Personality Individ Differ 40(1):5–15

Clinkinbeard SS (2014) What lies ahead: An exploration of future orientation, self-control, and delinquency. Crim Justice Rev 39(1):19–36

Cochran JK, Wood PB, Sellers CS, Wilkerson W, Chamlin MB (1998) Academic dishonesty and low self-control: An empirical test of a general theory of crime. Deviant Behav 19(3):227–255

Cornish DB, Clarke RV (1987) Understanding crime displacement: An application of rational choice theory. Criminology 25:933–948

Evenden JL (1999) Varieties of impulsivity. Psychopharmacology 146(4):348–361

Farrington DP, Loeber R, Van Kammen WB (1990) Long-term criminal outcomes of hyperactivity-impulsivity-attention deficit and conduct problems in childhood. In: Robins LN, Rutter M (eds) Straight and devious pathways from childhood to adulthood. Cambridge University Press, New York, NY, US, pp 62–81

Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Nagin DS (2000) Offending trajectories in a New Zealand birth cohort. Criminology 38(2):525–552

Fine A, van Rooij B (2017) For whom does deterrence affect behavior? Identifying key individual differences. Law Hum Behav 41(4):354–360

Frederick S, Loewenstein G, O’Donoghue T (2002) Time discounting and time preference: A critical review. J Econ Literature 40(2):351–401

Furstenburg F, Kennedy S, McLoyd V, Rumbaut R, Settersten R (2004) Growing up is harder to do. Contexts 3:33–41

Gardner H (1993) Frames of mind. Basic Books, New York, NY

Giordano PC, Cernkovich SA, Rudolph JL (2002) Gender, crime, and desistance: Toward a theory of cognitive transformation. Am J Sociol 107(4):990–1064

Gottfredson MR, Hirschi T (1990) A general theory of crime. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA

Grasmick HG, Tittle CR, Bursik RJ Jr, Arneklev BJ (1993) Testing the core empirical implications of Gottfredson and Hirschi’s general theory of crime. J Res Crime Delinq 30(1):5–29

Hay C (2001) Parenting, self-control, and delinquency: A test of self-control theory. Criminology 39:707–736

Hay C, Forrest W (2006) The development of self-control: Examining self-control theory’s stability thesis. Criminology 44(4):739–774

Higgins GE, Jennings WG, Tewksbury R, Gibson CL (2013) Exploring the link between low self-control and violent victimization trajectories in adolescents. Crim Justice Behav 36(10):1070–1084

Hill EM, Ross LT, Low BS (1997) The role of future unpredictability in human risk taking. Hum Nat 8(4):287–325

Hirschi T (1969) Causes of delinquency. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA

Hoffman JS (2004) Youth violence, resilience, and rehabilitation. LFB, New York

Huizinga D, Esbensen F, Weihar A (1991) Are there multiple paths to delinquency? J Crim Law Criminol 82:83–118

Jevons WS (1871/1911). The theory of political economy. Press, London

Kahneman D (2011) Thinking, fast and slow. Ferrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, NY

Katz J (1988) Seductions of crime: Moral and sensual attractions of doing evil. Basic Books, New York

Lee CA, Derefinko KJ, Milich R, Lynam DR, DeWall CN (2017) Longitudinal and reciprocal relations between delay discounting and crime. Personality Individ Differ 111:193–198

Long JS (1997) Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

Loughran TA, Paternoster R, Weiss D (2012) Hyperbolic time discounting, offender time preferences and deterrence. J Quant Criminol 28:607–628

Lynam DR, Caspi A, Moffit TE, Wikström PO, Loeber R, Novak S (2000) The interaction between impulsivity and neighborhood context on offending: The effects of impulsivity are stronger in poorer neighborhoods. J Abnorm Psychol 109(4):563–574

Mahler A, Simmons C, Frick PJ, Steinberg L, Cauffman E (2017) Aspirations, expectations, and delinquency: The moderating effect of impulse control. J Youth Adolesc 46(7):1503–1514

Mamayek CM, Loughran T, Paternoster R (2015) Reason taking the reins from impulsivity: The promise of dual-systems thinking for criminology. J Contemp Crim Justice 31(1):426–448

Mamayek CM, Paternoster R, Loughran TA (2017a) Temporal discounting, present orientation, and criminal deterrence. In: Bernasco W, Elffers H, van Gelder JL (eds) Handbook on offender decision making. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 209–227

Mamayek CM, Paternoster R, Loughran T (2017b) Self-control as self-regulation: A return to control theory. Deviant Behav 38(8):895–916

Menard S, Elliott DS (1996) Prediction of adult success using stepwise logistic regression analysis. A report prepared for the MacArthur Foundation by the MacArthur Chicago-Denver Neighborhood Project.

Moffitt TE (1993) Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychol Rev 100(4):674–701

Moffitt T, Caspi A, Rutter M, Silva PA (2001) Sex differences in antisocial behavior: Conduct disorder, delinquency, and violence in the Dunedin longitudinal study. Cambridge University Press, New York

Monahan KC, Steinberg L, Cauffman E, Mulvey EP (2009) Trajectories of antisocial behavior and psychosocial maturity from adolescence to young adulthood. Dev Psychol 45(6):1654

Monahan KC, Steinberg L, Cauffman E, Mulvey EP (2013) Psychosocial (im) maturity from adolescence to early adulthood: Distinguishing between adolescence-limited and persisting antisocial behavior. Dev Psychopathol 25:1093–1105

Mulvey EP, Steinberg L, Fagan J, Cauffman E, Piquero AR, Chassin L, Knight GP, Brame R, Schubert CA, Hecker T, Losoya SH (2004) Theory and research on desistance from antisocial activity among serious adolescent offenders. Youth Violence Juvenile Justice 2:213–236

Nagin DS (2005) Group-based modeling of development. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Nagin DS, Land KC (1993) Age, criminal careers, and population heterogeneity: Specification and estimation of a nonparametric, mixed Poisson model. Criminology 31:327–362

Nagin DS, Paternoster R (1993) Enduring individual differences and rational choice theories of crime. Law Soc Rev 27(3):467–496

Nagin DS, Paternoster R (1994) Personal capital and social control: The deterrence implications of a theory of individual differences in criminal offending. Criminology 32(4):581–606

Nagin DS, Pogarsky G (2001) Integrating celerity, impulsivity, and extralegal sanction threats into a model of general deterrence: Theory and evidence. Criminology 39(4):865–892

Nagin DS, Pogarsky G (2004) Time and punishment: Delayed consequences and criminal behavior. J Quant Criminol 20(4):295–317

Nguyen QC, Hussey JM, Halpern CT, Villaveces A, Marshall SW, Siddiqi A, Poole C (2012) Adolescent expectations of early death predict young adult socioeconomic status. Soc Sci Med 74:1452–1460

Nurmi JE (1993) Adolescent development in an age-graded context: The role of personal beliefs, goals, and strategies in the tackling of developmental tasks and standards. Int J Behav Dev 16(2):169–189

Oquendo MA, Galfalvy H, Russo S, Ellis SP, Grunebaum MF, Burke A, Mann JJ (2004) Prospective study of clinical predictors of suicidal acts after a major depressive episode in patients with major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 161(8):1433–1441

Ottaviani C, Vandone D (2011) Impulsivity and household indebtedness: Evidence from real life. J Econ Psychol 32(5):754–761

Petrich DM, Sullivan CJ (2020) Does future orientation moderate the relationship between self-control and offending? Insights from a sample of serious young offenders. Youth Violence Juvenile Justice 18(2):156–178

Piquero AR (2008) Taking stock of developmental trajectories of criminal activity over the life course. In: Liberman AM (ed) The long view of crime: A synthesis of longitudinal research. Springer, New York, NY, pp 23–78

Piquero AR (2016) 'Take my license n’ all that jive, I can’t see … 35’: Little hope for the future encourages offending over time. Justice Q 33(1):73–99

Piquero AR, Jennings WG, Farrington DP (2018) Money now, money later: Linking time discounting and criminal convictions in the Cambridge Study in delinquent development. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 62(5):1131–1142

Piquero AR, Monahan KC, Glasheen C, Schubert CA, Mulvey EP (2013) Does time matter? Comparing trajectory concordance and covariate association using time-based and age-based assessments. Crime Delinq 59(5):738–763

Piquero AR, Paternoster R, Pogarsky G, Loughran T (2011) Elaborating the individual difference component in deterrence theory. Ann Rev Law Soc Sci 7:335–360

Piquero A, Tibbetts S (1996) Specifying the direct and indirect effects of low self-control and situational factors in offenders’ decision making: Toward a more complete model of rational offending. Justice Q 13(3):481–510

Pratt TC, Cullen FT (2000) The empirical status of Gottfredson and Hirschi’s general theory of rime: A meta-analysis. Criminology 38(3):931–964

Pulkinnen L (1986) The role of impulse control in the development of antisocial and prosocial behavior. In: Olweus D, Block J, Radke-Yarrow M (eds) Development of antisocial and prosocial behaviors: Theory, Research, and Issues. Academic Press, New York, pp 149–175

Rachlin H (2000) The science of self-control. Harvard University Press

Rae J (1834) The sociological theory of capital. Macmillan, London

Ramsey FP (1928) A mathematical theory of saving. Econ J 38:543–559

Ray JV, Jones S, Loughran TA, Jennings WG (2013) Testing the stability of self-control: Identifying unique developmental patterns and associated risk factors. Crim Justice Behav 40(6):588–607

Robbins RN, Bryan A (2004) Relationships between future orientation, impulsive sensation seeking, and risk behavior among adjudicated adolescents. J Adolesc Res 19(4):428–445

Sampson R, Laub JH (1993) Crime in the making: Pathways and turning points through life. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Sampson R, Raudenbush S (1999a) Systematic social observation on public spaces: A new look at disorder in urban neighborhoods. Am J Sociol 105(3):603–651

Sampson RJ, Laub JH (1997) A life-course theory of cumulative disadvantage and the stability of delinquency. In: Thornberry T (ed) Developmental theories of crime and delinquency. Transaction Publishers, New York, NY, pp 1–29

Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW (1999b) Systematic social observation of public spaces: A new look at disorder in urban neighborhoods. Am J Sociol 105(3):603–651

Samuelson PA (1937) A note on measurement of utility. Rev Econ Stud 4:155–161

Schag K, Schönleber J, Teufel M, Zipfel S, Giel KE (2013) Food-related impulsivity in obesity and Binge Eating Disorder–a systematic review. Obes Rev 14(6):477–495

Slutske WS, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Poulton R (2005) Personality and problem gambling: A prospective study of a birth cohort of young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62(7):769–775

Steinberg L, Graham S, O’Brien L, Woolard J, Cauffman E, Banich M (2009) Age differences in future orientation and delay discounting. Child Dev 80(1):28–44

Sweeten G (2012) Scaling criminal offending. J Quant Criminol 28(3):533–557

Taylor SE (1981) The interface of cognitive and social psychology. In: Harvey J (ed) Cognition, social behavior, and the environment. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, N J, pp 189–211

Toby J (1957) Social disorganization and stake in conformity: Complementary factors in the predatory behavior of hoodlums. J Crim Law Criminol 48(1):12–17

Topalli V, Wright R (2004) Dubs, dees, beats, and rims: Carjacking and urban violence. In: Dabney D (ed) Criminal behaviors: A text reader. Wadsworth Publishing, Belmont, CA

Vitaro F, Arseneault L, Tremblay RE (1999) Impulsivity predicts problem gambling in low SES adolescent males. Addiction 94(4):565–575

Weinberger DA, Schwartz GE (1990) Distress and restraint as superordinate dimensions of self-reported adjustment: a typological perspective. J Pers 58(2):381–417

Whiteside SP, Lynam DR (2001) The five factor model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality Individ Differ 30(4):669–689

Williams K, Hawkins G (1986) Perceptual research on general deterrence: a critical review. Law Soc Rev 20:545–572

Wilson M, Daly M (1997) Life expectancy, economic inequality, homicide, and reproductive timing in Chicago neighbourhoods. BMJ 314(7089):1271–1274

Wilson JQ, Herrnstein RJ (1985) Crime and human nature. Touchstone, New York, NY

Wilson WJ (1987) The truly disadvantaged: The inner city, the underclass, and public policy. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL

Zelazo PD, Carter A, Reznick JS, Frye D (1997) Early development of executive function: A problem-solving framework. Rev Gen Psychol 1(2):198–226

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Kate Doubler and Bryanna Fox for their valuable feedback on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Figs.

4,

Trajectories of impulsivity. Note After determining a 6-group solution was optimal, the order of the trajectories were selected (BIC = −9305.73): Group 1 (quadratic, AvePP = 0. 90); Group 2 (quadratic, AvePP = 0.82); Group 3 (intercept-only, AvePP = 0.77); Group 4 (quadratic, AvePP = 0.77); Group 5 (linear, AvePP = 0.87); Group 6 (quadratic, AvePP = 0.86)

5,

6,

Trajectories of expected social value (ESV). Note After determining a 5-group solution was optimal, the order of the trajectories were selected (BIC = −22,402.35): Group 1 (intercept-only, AvePP = 0. 89); Group 2 (intercept-only, AvePP =0 .81); Group 3 (quadratic, AvePP = 0.77); Group 4 (quadratic, AvePP = 0.77); Group 5 (quadratic, AvePP = 0.91)

7, Tables

7,

8,

9, and

10.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jaynes, C.M., Moule, R.K., Hubbell, J.T. et al. Impulsivity or Discounting? Evaluating the Influence of Individual Differences in Temporal Orientation on Offending. J Quant Criminol 38, 831–859 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-021-09518-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-021-09518-5