Abstract

Major advances in our understanding of the functional heterogeneity of enteric neurons are driven by the application of newly developed, innovative methods. In contrast to this progress, both animal and human enteric neurons are usually divided into only two morphological subpopulations, “Dogiel type II” neurons (with several long processes) and “Dogiel type I” neurons (with several short processes). This implies no more than the distinction of intrinsic primary afferent from all other enteric neurons. The well-known chemical and functional diversity of enteric neurons is not reflected by this restrictive dichotomy of morphological data. Recent structural investigations of human enteric neurons were performed by different groups which mainly used two methodical approaches, namely detecting the architecture of their processes and target-specific tracing of their axonal courses. Both methods were combined with multiple immunohistochemistry in order to decipher neurochemical codes. This review integrates these morphological and immunohistological data and presents a classification of human enteric neurons which we believe is not yet complete but provides an essential foundation for the further development of human gastrointestinal neuropathology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Prologue: from past to present

The earliest approaches to identify nerve structures in the gut resulted in the description of different ganglionic enteric nerve networks (Meissner 1857; Auerbach 1862; Schabadasch 1930) and the subsequent distinction of enteric neuron types (Dogiel 1899). The latter phase in particular was embroiled in decades of dispute between followers of two rival theories concerning the basic structure of the nervous system, the reticular versus the neuron theory, the latter mainly based on the works of Ramón y Cajal (Garcia-Lopez et al. 2010). This conceptual discord was only decided in favor of the neuron theory in the 1950s by electron microscopy (Clarke and O’Malley 1996).

The Russian histologist Dogiel was a rather inconsistent follower of the reticular concept because he distinguished neural processes into long and short ones, namely axons and dendrites (Brehmer et al. 1999a). Although his descriptions of three neuron types contained the hidden potency for further development, “collapsing of the classifications” (Furness and Costa 1987) led to a simplified morphological two-type concept (Brehmer et al. 1999a). For numerous contemporary researchers in the field of the enteric nervous system (ENS), the distinction between Dogiel type II and Dogiel type I neurons is mainly useful for separating primary afferent from all other enteric neurons (Nurgali 2009; Carbone et al. 2014; Fung and Vanden Berghe 2020; Spencer and Hu 2020; Smolilo et al. 2020; Yuan et al. 2021). The occasional identification of non-Dogiel type I or II but filamentous neurons (Furness et al. 1988; Carbone et al. 2014) indicated both the possibility and the need for a more solid morphological classification reminiscent of Dogiel’s original tree-type system.

Three original types of Dogiel

Although Dogiel (1899) reported that he also considered submucosal neurons, his three types are obviously concerned with myenteric neurons (based on specimens from human infants, guinea pigs and other mammals). Of his depictions, only samples of type I and II neurons are derived from humans (Brehmer 2006).

Type I neurons had one axon and up to 20 dendrites which were, in simple terms, short with broad or lamellar endings. Axons of these neurons were observed to run through adjacent ganglia, occasionally into the muscle coat.

Type II neurons had one axon and up to 16 long dendrites leaving the ganglion of origin and resembling axons—a distinctive ambiguity (see below).

Type III neurons had one axon and up to 10 (seldom more) dendrites which were many times longer than those of type I neurons, ramified and had tapering endings within the ganglion of origin (in contrast to the processes of type II neurons). Only two examples derived from guinea pig large intestine were depicted by Dogiel (1899).

Following the categories of the recent International Neuroanatomical Terminology (FIPAT. Terminologia Neuroanatomica. 2017), all these Dogiel types of neurons would be called multipolar neurons displaying one (long or short) axon and several dendrites.

Additional criteria of Stach

Based mainly on investigations on silver-impregnated whole mounts of the pig small intestine, two general, conceptual advances as to morphological classification schemes were achieved by Stach in the 1980s.

First, he strictly considered the combination of two (at first glance independent) morphological features, namely the dendritic architecture and the axonal course in Dogiel’s types. This resulted in the clear distinction between (pig) type I neurons with short, lamellar dendrites, and orally running axons as well as (pig) type III neurons with long, branched, tapering dendrites and anally running axons (Stach 1980, 1982a). This conceptual progress forced a numerical extension beyond Dogiel’s three types. Stach type IV neurons (in the pig) had short, tapering dendrites and axons running vertically towards the mucosa (Stach 1982b; Brehmer et al. 1999b).

Secondly, Stach specified the generally used term “multipolar” for neurons displaying numerous processes. On the one hand, “multipolar type I, III, IV neurons” (and also further types V, VI: Stach 1985, 1989) were termed multidendritic uniaxonal neurons. On the other hand, “multipolar type II neurons” were characterized as multiaxonal neurons (Stach 1981; there are both non-dendritic and dendritic ones, see below). This distinction within the category “multipolar neurons” is not considered in the recent neuroanatomical terminology (FIPAT. Terminologia Neuroanatomica. 2017).

Enteric neuron classifications in different mammalian species

Our conceptual understanding of enteric circuits in general is derived mainly from the guinea pig (Furness and Costa 1987; Furness 2006). That is, intrinsic afferent neurons, several types of ascending and descending interneurons or various muscle or mucosal motor neurons were first identified in this species. The immunohistochemical detection of the presence or absence of neuronal substances (i.e., the chemical coding of enteric neurons) became an effective and easily applicable tool for distinction of enteric neuron types in the guinea pig and, subsequently, in other species. In contrast, morphological correlates of this chemical and functional heterogeneity were hardly searched for.

Detailed knowledge on neurochemical classes of neurons is available from various gut segments of the guinea pig, e.g. the small intestine (Costa et al. 1996; Brookes 2001), the colon (Lomax and Furness 2000) and the stomach (Schemann et al. 2001). Considerable data also exist from the mouse (Sang et al. 1997; Nurgali et al. 2004; Qu et al. 2008; Mongardi Fantaguzzi et al. 2009), the rat (Sayegh and Ritter 2003; Mitsui 2010), the pig (Brown and Timmermans 2004; Brehmer 2006; Petto et al. 2015; Mazzoni et al. 2020) and other mammals (Freytag et al. 2008; Chiocchetti et al. 2009; Noorian et al. 2011).

It was recognized early on that the transfer of single findings from one species to another (including human) is hampered by species differences. Furthermore, the concept “one neuron–one function” has been refuted. Intrinsic primary afferent neurons (IPANs, see below) can also be regarded as interneurons (Wood 1994; Furness et al. 1998), and non-IPANs have also been shown to be (mechano-)sensory (Spencer and Smith 2004; Spencer and Hu 2020), even in the human ENS (Kugler et al. 2015).

Because of the restricted access to human tissues, our knowledge of human enteric morphochemical classes is much more limited than that of some animal species. Therefore, the following assignment of functions to morphochemical phenotypes remains partly putative and certainly incomplete. The aim of this review is to integrate findings of morphological and immunohistological features of human enteric neurons and to stimulate further search for both physiological features and pathohistological alterations in the human ENS. It has been shown that both dendritic architecture (Brehmer et al. 2001) and chemical coding of neurons (Schemann and Neunlist 2004) may change under experimental and pathological conditions, respectively.

Structure of human myenteric neurons

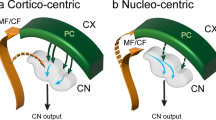

Recent attempts to identify and characterize the structure and main functions of human enteric neuron populations followed two methodical approaches.

One method aimed at the representation of dendrites and proximal axonal segments of neurons (Table 1). Classically, this has been achieved by silver impregnation (Stach 1980, 1989; Stach et al. 2000). Presently, this capricious method is being replaced by immunostaining with cytoskeletal markers which depicts neurons almost equivalently (Vickers and Costa 1992; Brehmer et al. 2002b, 2004a) but is a more reliable and combinable staining method. We used neurofilaments (NF; Brehmer et al. 2004a) in human myenteric and peripherin (PERI; Kustermann et al. 2011) in human submucosal neurons. These markers represent the morphology of the cytoskeleton but not that of the whole, membrane-covered neuron. They allowed us, by co-staining with other neuronal markers, to differentiate neurons based on their morphochemical phenotype. That is, neurons displaying different dendritic architectures and, simultaneously, different chemical codes were distinguished from each other. In this context, application of the panneuronal marker human neuronal protein HuC/D (HU) enabled estimation of proportions of enteric subpopulations (Ganns et al. 2006).

The other method deciphered target tissues of axonal projections by tracing techniques (most successful with the carbocyanine tracer DiI; Wattchow et al. 1995, 1997; Porter et al. 1997, 2002; Humenick et al. 2019, 2021). These studies demonstrated projection distances for motoneurons of about 1 to 2 cm (for ascending and descending pathways to circular and longitudinal muscle, respectively) as well as for interneurons of about 4 to 7 cm (for ascending and descending interneurons, respectively).

Since both approaches were combined with multiple immunohistochemistry for neuronal substances, correlation of the results is possible to some degree.

Dogiel type II neurons

Also, with regard to the entire human (and mammalian) nervous system, Dogiel type II neurons (Dogiel 1899) are unique. Already the Russian histologist was apparently uncertain in his own interpretation when distinguishing between one axon and (up to) 16 dendrites in this type (Brehmer et al. 1999a). Stach (1981) introduced the term “multiaxonal” because, neurohistologically, all processes of these neurons look like axons. Hendriks et al. (1990) showed that all these processes conduct action potentials; thus, electrophysiologically, they behave like axons. Altogether, they were characterized in the guinea pig small intestine as intrinsic primary afferent neurons (IPANs), the only ones known so far in a peripheral organ (Furness et al. 1998). Individual features of the equivalent neurons in various species were shown to differ. The electrophysiological afterhyperpolarization (AHP) phenomenon of IPANs in the guinea pig could barely be proven in humans (Brookes et al. 1987), and the chemical coding between IPAN-candidates of other species varied considerably, apart from their common cholinergic phenotype. In the guinea pig, calbindin (CALB) is an effective marker for IPANs (Furness et al. 1990; Song et al. 1994). Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) is, among other additional markers, immunohistochemically demonstrable in putative IPANs of pigs (Scheuermann et al. 1987; Wolf et al. 2007), mice (Furness et al. 2004; Melo et al. 2020), lambs (Chiocchetti et al. 2006) and rats (Mitsui 2009).

In the human small intestine, Dogiel type II neurons (Fig. 1a), the putative IPANs, amount to about 10% of the whole myenteric neuron population. Immunohistochemical co-labelling of calretinin (CALR), somatostatin (SOM) and substance P (SP) is characteristic for these neurons (Brehmer et al. 2004b; Weidmann et al. 2007), whereas both CALB and CGRP are only detectable in a minority of type II neurons (Brehmer 2007).

In the human stomach, less than 1% of myenteric neurons could be morphologically identified as type II neurons, and most of them were SOM-reactive, with weak or no co-reactivity for CALR (Anetsberger et al. 2018).

In the human colon, co-labelling of CALR and SOM is, similar to the small intestine, highly indicative for type II neurons; however, about one third of CALR+/SOM- neurons and about half of SOM+/CALR- neurons were also NF-reactive, multiaxonal type II neurons (own unpublished observations).

Next to these non-dendritic Dogiel type II neurons there are dendritic type II neurons (Fig. 1b). These also have more than one axon and additional dendrites and were originally described in the pig (Stach 1989). In the guinea pig, they were characterized as IPANs (Bornstein et al. 1991; Brookes et al. 1995). In humans, they were occasionally identified in the small intestinal myenteric plexus (Stach et al. 2000) and are non-nitrergic, probably cholinergic neurons (Brehmer 2006).

As pointed out above, a key criterion for identifying IPANs in various species is their “Dogiel type II” (i.e. multiaxonal) morphology as opposed to the “Dogiel type I” morphology of neurons with short dendrites and a single axon. Actually, quite different human myenteric neurons are distinguished that fit into this overall category (Figs. 2 and 3).

a Two “Dogiel type I” neurons (filled arrowheads) stained for neurofilaments (NF). The left one is a spiny neuron, its axon (ax) runs to the right (i.e. anally); the right one is a stubby neuron with an axon (ax) running to the left (i.e. orally). b Corresponding demonstration of staining for neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS). The spiny neuron is positive, the stubby one negative (filled and empty arrowhead, respectively). c The spiny neuron is co-reactive for vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), the stubby neuron is negative (filled vs. empty arrowhead). d The spiny neuron is negative for choline acetyltransferase (ChAT), the stubby neuron is positive (empty vs. filled arrowhead). (From ascending colon of a 104-year-old woman; body donated to the Institute of Anatomy) Bar = 50 µm. (Antibodies: NF: Sigma-Merck N0142; nNOS: Novus Biologicals NB120-3511; VIP: Dianova T-5030; ChAT: Merck-Millipore AB144P)

a A short-dendritic (“Dogiel type I”) neuron immunopositive for neurofilaments (NF; enlarged in b) whose axon (ax) runs from the myenteric plexus (MP) into a typically coiled interconnecting strand towards the external submucosal plexus (ESP). (Myenteric whole mount with adhering remnants of circular muscle strips and submucosal connective tissue, derived from the transverse colonic segment resected from a female patient aged 21 years suffering from colon carcinoma. Composition of four subsequent z-series following the marked axon, each depicted as extended focus image.) Bar = 50 µm

Stubby type I neurons

Due to the shapes of their “short” processes, demonstrated by NF-immunohistochemistry, these human myenteric neurons most likely match Dogiel’s original descriptions of type I neurons (Fig. 4a). They have short, partly stubby (more likely in the small intestine), partly lamellar dendrites (more likely in the colon). In the small intestine, their NF-stained axons start to run preferentially in the oral direction (about 50% vs. 30% anally; Brehmer et al. 2005). Immunohistochemically, they contain choline acetyltransferase (ChAT), leu-enkephalin (ENK) and, partly, SP (Brehmer et al. 2005; Beck et al. 2009). These chemical characteristics correspond to ascending motor and interneurons identified by Porter et al. (1997) and Humenick et al. (2021).

a Drawings of three stubby (type I) neurons; the two left ones are from the small intestine, the right one from the large intestine. b Four spiny (type I) neurons; the two upper left ones are from the small intestine, the upper right one from the large intestine. The lower one with a main dendrite is from duodenum. c Two hairy (type I) neurons from the human stomach. (ax = cut ends of axons) Bar = 50 µm

Spiny type I neurons

With their short processes, these NF-stained neurons also correspond to Dogiel type I neurons. Occasionally, the dendrites have widened, lamellar endings or branching points, but their main appearance is spiny or thorny (Fig. 4b). In contrast to stubby neurons, the dendrites of spiny neurons also frequently emerge from the luminal somal surface, and the whole cell has a hedgehog-like appearance (Lindig et al. 2009). The axons preferentially start running anally; they are immunopositive for neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) and vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP; Brehmer et al. 2006), and partly (maybe additionally?) for nNOS and ChAT (Beck et al. 2009). This corresponds to the chemical codes of circular muscle motor neurons (Wattchow et al. 1997; Porter et al. 1997) and descending interneurons (Porter et al. 2002; Humenick et al. 2021), respectively.

Hairy type I neurons

Uniaxonal, short-dendritic neurons (“Dogiel type I”) which project from the myenteric plexus to the mucosa were not included in Dogiel’s classification. These Stach type IV neurons were first observed in pigs and guinea pigs (Stach 1982b, 1989; Furness et al. 1985; Brehmer et al. 1999b). Human myenteric, uniaxonal neurons projecting to the mucosa were suggested by Stach et al. (2000) using classical silver staining, while the results of target-specific tracing studies in the human gut were ambiguous (Wattchow et al. 1995; Hens et al. 2001). The latter authors found SOM+/SP± and VIP+ myenteric neurons traced from the jejunal mucosa of four infants. In the human stomach, myenteric neurons innervating mucosal cells were characterized immunohistochemically, and these neurons were found to contain ChAT, VIP, gastrin-releasing peptide and neuropeptide Y (Anetsberger et al. 2018; Furness et al. 2020). Their NF-morphology resembled a “hairy head”, and they had short, extremely thin dendrites (Fig. 4c, Anetsberger et al. 2018). Subsequently, such myenteric neurons co-reactive for NF+/ChAT+/VIP+ were also seen in the small intestine (unpublished observations). A colonic myenteric neuron projecting directly towards the external submucosal plexus is depicted in Fig. 3. It displayed short, thin dendrites, but overall, and in contrast to gastric hairy neurons, it resembled a less hairy head.

Long-dendritic, uniaxonal neurons

Both human myenteric type III and type V neurons have been observed so far, based on silver staining and NF-immunohistochemistry, in the small intestine only (Stach et al. 2000; Brehmer et al. 2004a). Their type-specific immunohistochemical characterization awaits more detailed analysis. Although objectifying morphometric evaluations of enteric dendritic tree patterns are rare (Brehmer and Beleites 1996) and still pending in the human gut, the difference between neurons with short (Fig. 4a–c) and with long dendrites (Fig. 5a, b) is impressive at first glance.

Type III neurons (Fig. 5a). Dogiel‘s (1899) depictions of two myenteric type III neurons derived from the guinea pig large intestine. Nearly a century later, type III neurons were rediscovered and precisely described in the pig upper small intestine (Stach 1982a). In humans, their unequivocal representation using NF-immunohistochemistry succeeded especially in the small intestinal myenteric plexus (Brehmer et al. 2004a). These radial long-dendritic neurons are non-nitrergic and mostly cholinergic (Brehmer et al. 2004a; Beck et al. 2009), which is in sharp contrast to pig nitrergic long-dendritic (type III) neurons (Timmermans et al. 1994; Brehmer and Stach 1997). This difference indicates that an appropriate comparative morphology, i.e. the definition of functionally equivalent enteric neurons across species, cannot be established by pure transfer of superficial shape criteria from one species to another. Human type III neurons display immunoreactivity for CALB (Zetzmann et al. 2018), and CALR reactivity was demonstrated in some of them (Brehmer et al. 2004b). Tracing studies in the human colon have assigned neurons with ChAT+/CALB+ and ChAT+/CALR+ immunoreactivity to ascending and descending interneurons, respectively (Humenick et al. 2021). However, on the one hand, long-dendritic neurons in the human colon have not yet been successfully demonstrated by NF-staining (apart from single exceptions; Beck et al. 2009), and on the other hand, a specific chemical code of type III neurons in the human small intestine is not yet defined (Zetzmann et al. 2018).

Type V neurons (Fig. 5b). These polar long-dendritic myenteric neurons were first described as a peculiar population in the pig lower small intestine, where they occur in two forms: as single cells and in aggregates (Stach 1985; Brehmer et al. 2002a, b). Their putative functional equivalence with ChAT+/SOM+ co-reactive interneurons of the guinea pig (Portbury et al. 1995) has been discussed (Brehmer et al. 2004b; Brehmer 2006). Human type V neurons, in striking contrast to human “multipolar” type III neurons, appear as “unipolar” neurons mostly displaying a single stem process from which both several long, branched, tapering dendrites and the single axon emerge. With this architecture of processes, they resemble “monopolar invertebrate motor neurons” (Smarandache-Wellmann 2016). Human type V neurons are non-nitrergic and cholinergic; a minority (16%) display additional SOM-reactivity (Brehmer et al. 2004a).

Regional proportions of myenteric neurons

Overall, myenteric neurons can be immunohistochemically grouped into two large populations, namely neurons reactive for nNOS or for ChAT, as well as into two smaller populations immunoreactive for both or for neither of these markers, respectively. Data based on this categorization were provided for the human stomach by Pimont et al. (2003) and Anetsberger et al. (2018), for the human small intestine by Beck et al. (2009) and for the human colon by Murphy et al. (2007) and Beck et al. (2009).

For the stomach, data from Anetsberger et al. (2018) are graphically summarized in Fig. 6. Nitrergic neurons included mainly two groups: nNOS+/VIP+ neurons were mostly spiny neurons, whereas nNOS+/VIP− neurons displayed, apart from a few spiny neurons, no specific dendritic architecture (each about 12%). Such morphologically “unspecific”, “simple” or “small” neurons are also known from other species (Stach 1989; Qu et al. 2008). Cholinergic neurons included ChAT+/VIP+ hairy neurons (about 13%) as well as several different ChAT-only neurons (about 40%), namely stubby neurons, “unspecific” neurons without distinct dendritic trees, and a few multiaxonal type II neurons (less than 1%).

Morphochemically defined myenteric neuron populations in the human stomach (data from Anetsberger et al. 2018). The proportions of cholinergic subtypes were not yet estimated. (1: VIP+ neurons, 1.4%; 2: cChAT+/nNOS+ neurons, 1.3%; 3: cChAT+/nNOS+/VIP+ neurons, 0.7%)

In the small intestine, the morphological diversity of myenteric neurons is most pronounced. Besides short-dendritic (stubby and spiny) and non-dendritic type II neurons, long-dendritic neurons are common in this longest gut segment. Type III neurons are present in all small intestinal subregions, while type V neurons are conspicuous mainly in the duodenum and upper jejunum. In Fig. 7, results of several studies were combined to show that the morphological diversity is greatest among cholinergic neurons. These include stubby (type I) as well as type II, III and V neurons. The nitrergic spiny (type I) neurons are depicted as two separate nitrergic populations (+VIP vs. +ChAT), although they may overlap.

Morphochemically defined myenteric neuron populations in the human small intestine. Undefined cholinergic neurons are illustrated in yellow. Proportions of type III and type V neurons were not yet estimated; the latter are mainly present in the upper small intestine (asterisk). Data from Brehmer et al. (2005, 2006), Weidmann et al. (2007), Beck et al. (2009), Schuy et al. (2011), Zetzmann et al. (2018)

Colonic putative IPANs were identified by NF-immunohistochemistry. These multiaxonal type II neurons are common in the large intestine (Beck et al. 2009; Zetzmann et al. 2018) but have so far only been focused on in the small intestine in terms of their chemical coding and proportion (Weidmann et al. 2007).

Colonic interneurons were identified by DiI-tracing, with four ascending and descending populations each distinguished (Humenick et al. 2021). Among the ascending populations, three contain ChAT and ENK and correspond immunohistochemically to stubby neurons (Brehmer et al. 2005). Among the descending populations, ChAT+/nNOS+ interneurons chemically correspond to spiny neurons (Beck et al. 2009), whereas nNOS-only neurons may be unspecific neurons without conspicuous dendritic trees. Colonic ChAT+/CALB+ ascending or ChAT+/CALR+ and ChAT+/5HT+ descending interneurons have not yet been identified as to their NF-morphology.

Colonic circular muscle motor neurons included ascending, ChAT+ neurons and descending nNOS+/VIP+ neurons (Porter et al. 1997), the latter corresponding to nNOS+/VIP+ spiny neurons (Brehmer et al. 2006).

Colonic longitudinal muscle motor neurons included ChAT+ ascending as well as nNOS+ and nNOS+/VIP+ ascending and descending neurons (Humenick et al. 2019). nNOS+/VIP+ and nNOS+/ChAT+ spiny neurons, from stomach to colon, may be overlapping populations (we have observed neurons co-reactive for nNOS, VIP and ChAT but not yet estimated quantitatively). They may be both inter- and motor neurons.

Colonic and small intestinal myenteric neurons projecting outside the muscle coat have to be further investigated. By DiI-tracing, such neurons were identified by Wattchow et al. (1995) in both the small and large intestine as well as by Hens et al. (2001) in the jejunum of infants. These may include type II neurons with axons running towards the submucosa (Brehmer et al. 2004b) as well as hairy neurons (subtype I of Dogiel, type IV of Stach) in the stomach (Anetsberger 2018) and in the colon (Fig. 3).

Structure of human submucosal neurons

Historically, the first categorizations of submucosal neurons were published by authors other than Dogiel (Kustermann et al. 2011). These were Koelliker (1896) in the dog, Ramón y Cajal (1911) in the guinea pig, Rossi (1929) in the pig, Sokolova (1931) in cattle and Stöhr (1949) in humans. A general structural dichotomy into multipolar and unipolar (and occasionally also bipolar) neurons was detected and could be, to some degree, also correlated with the chemical codes of neuron populations in human small and large intestinal submucosal neurons (Fig. 8, Table 2).

Although the human submucosal plexus, similar to that of other medium-sized mammals, consists of two topographically distinct networks (reviewed in Brehmer et al. 2010), there seem to be only quantitative differences in neuronal composition between them (Jabari et al. 2014). This is in striking contrast, for example, to the pig submucosa, where qualitative differences between the external and the internal submucosal plexus (ESP, ISP) are conspicuous (Stach 1977; Timmermans et al. 2001; Kapp et al. 2006; Petto et al. 2015). The demonstration of human submucosal neuron morphology was more successful using PERI- instead of NF-antibodies (Ganns et al. 2006; Kustermann et al. 2011).

Submucosal unipolar (pseudouniaxonal) neurons

These neurons (Kustermann et al. 2011) have a small round or oval cell body with a single (seldom two or three) process, most likely an axon. Occasionally, the process could be traced until its branching point; thus these neurons may be pseudouniaxonal. Immunohistochemically, they contain ChAT, SOM and, partly, SP (Beyer et al. 2013). Based on the structure and the localizations of ChAT+/SOM+/SP+ endings in the mucosa, we suggest a sensory function. To some extent, the identification of mechanosensitive ChAT+/SP+ neurons (Filzmayer et al. 2020) supports this assumption.

Submucosal multipolar (dendritic, uniaxonal) neurons

In contrast to the unipolar neurons described above, these obviously have numerous processes, most of which being dendrites (Kustermann et al. 2011). Based on their PERI-staining, we observed these neurons to be mostly uniaxonal (seldom bi- or tripolar), a finding supported to some extent by the descriptions by Porter et al. (1999). Furthermore, they are co-immunoreactive for ChAT, CALR and VIP. It has to be considered that the colocalization rate of CALR and VIP is almost 100% in colonic submucosal neurons, whereas in the small intestine, up to 16% of VIP-reactive neurons do not co-stain for CALR (Beuscher et al. 2014). Boutons co-stained for VIP and CALR were found exclusively in the colonic mucosa (Beuscher et al. 2014); therefore, a mucosal effector function has been suggested (Jabari et al. 2014). Contrary to these results, Porter et al. (1999) found VIP+ submucosal neurons projecting to the circular muscle.

Submucosal nitrergic and other neurons

nNOS+ neurons represent a small submucosal population (1–4%; Beuscher et al. 2014), and an even smaller one is represented by nNOS+/VIP+ colocalization (max. 1%, in the external submucosal plexus; Beuscher 2014; Porter et al. 1999). It is supposed that these neurons are dendritic and uniaxonal, though this has not yet been investigated in detail.

Moreover, Beuscher et al. (2014) found that more than 30% of small intestinal and more than 10% of colonic submucosal neurons were only stained by HU. Thus, there may be three or more populations in the human submucosa as found in the mouse (Wong et al. 2008; Mongardi Fantaguzzi et al. 2009) and guinea pig (Furness et al. 2003), respectively, which remain to be further characterized.

Regional proportions of submucosal neurons

In the stomach, no continuous submucosal plexus could be found and, as compared with the intestines, very few submucosal neurons were present (Anetsberger et al. 2018). Morphologically, both neuron types (non-dendritic and dendritic, see above) were identified, although no clear morphochemical correlation could be proved.

In the intestines, so far, we have found no qualitative differences in neuronal composition, either between the small intestine and colon or between the ESP and the ISP (Kustermann et al. 2011; Beyer et al. 2013; summarized and graphically illustrated by Beuscher et al. 2014). Basically, four populations, three larger and one smaller, were identified. All of them may include subpopulations. The most striking difference between the small intestinal and the colonic submucosa is the proportion of VIP+ neurons, though it has to be emphasized that the variability is enormous.

VIP+/ChAT±/CALR± dendritic uniaxonal neurons amounted to 32–39% (ISP-ESP) in the small intestine and 72–74% in the colon.

SOM+/ChAT+/SP± pseudouniaxonal neurons accounted for 36–24% (ISP-ESP) in the small intestine and 14–10% in the colon.

nNOS+ neurons were between 1 (ISP of both segments) and 4% (colonic ESP). Here, up to 1% nNOS+/VIP+ neurons were additionally identified.

Immunohistochemically uncharacterized (HU+ only) neurons amounted to 11–34%.

Epilogue: from present to future

Here, we tried to emphasize the importance of morphological analysis of the processes of human enteric neurons. Dendritic architecture is one cornerstone for evaluating synaptic connectivity, and axonal projection is more than a symbolic link to the function of a neuron. Both the omnipresence of, e.g., stubby and spiny type I neurons from stomach to colon and the limited occurrence of, e.g., type V neurons only in the upper small intestine indicate general principles as well as local characteristics of the neuronal composition of the human ENS. Such regional differences should also exist in the human colon, as indicated by differences in motor patterns between the upper and lower colon in the mouse (Costa et al. 2021). The further classification of human enteric neurons must also consider regional peculiarities. This is a basic requirement for understanding physiological functions, pathological processes and, ultimately, options for therapeutic interventions in different regions of the gastrointestinal tract. To this end, all methodical approaches available may contribute, both “classical” and “modern” ones.

References

Anetsberger D, Kurten S, Jabari S, Brehmer A (2018) Morphological and immunohistochemical characterization of human intrinsic gastric neurons. Cells Tissues Organs 206(4–5):183–195. https://doi.org/10.1159/000500566

Auerbach L (1862) Ueber einen Plexus myentericus, einen bisher unbekannten ganglio-nervösen Apparat im Darmkanal der Wirbelthiere. In. Morgenstern, Breslau, pp 1–13

Beck M, Schlabrakowski A, Schrödl F, Neuhuber W, Brehmer A (2009) ChAT and NOS in human myenteric neurons: co-existence and co-absence. Cell Tissue Res 338(1):37–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-009-0852-4

Beuscher N, Jabari S, Strehl J, Neuhuber W, Brehmer A (2014) What neurons hide behind calretinin immunoreactivity in the human gut? Histochem Cell Biol 141(4):393–405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00418-013-1163-0

Beyer J, Jabari S, Rau TT, Neuhuber W, Brehmer A (2013) Substance P- and choline acetyltransferase immunoreactivities in somatostatin-containing, human submucosal neurons. Histochem Cell Biol 140(2):157–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00418-013-1078-9

Bornstein JC, Hendriks R, Furness JB, Trussell DC (1991) Ramifications of the axons of AH-neurons injected with the intracellular marker biocytin in the myenteric plexus of the guinea pig small intestine. J Comp Neurol 314(3):437–451

Brehmer A (2006) Structure of enteric neurons. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol 186:1–94

Brehmer A (2007) The value of neurofilament-immunohistochemistry for identifying enteric neuron types - special reference to intrinsic primary afferent (sensory) neurons. In: Arlen RK (ed) New research on neurofilament proteins. Nova Science Publishers, New York, pp 99–114

Brehmer A, Beleites B (1996) Myenteric neurons with different projections have different dendritic tree patterns: a morphometric study in the pig ileum. J Auton Nerv Syst 61(1):43–50

Brehmer A, Stach W (1997) Morphological classification of NADPHd-positive and -negative myenteric neurons in the porcine small intestine. Cell Tissue Res 287(1):127–134

Brehmer A, Schrödl F, Neuhuber W (1999a) Morphological classifications of enteric neurons–100 years after Dogiel. Anat Embryol (berl) 200(2):125–135

Brehmer A, Schrödl F, Neuhuber W, Hens J, Timmermans JP (1999b) Comparison of enteric neuronal morphology as demonstrated by Dil-tracing under different tissue-handling conditions. Anat Embryol (berl) 199(1):57–62

Brehmer A, Frieser M, Graf M, Radespiel-Tröger M, Göbel D, Neuhuber W (2001) Dendritic hypertrophy of Stach type VI neurons within experimentally altered ileum of pigs. Auton Neurosci 89:31–37

Brehmer A, Schrödl F, Neuhuber W (2002a) Correlated morphological and chemical phenotyping in myenteric type V neurons of porcine ileum. J Comp Neurol 453(1):1–9

Brehmer A, Schrödl F, Neuhuber W (2002b) Morphological phenotyping of enteric neurons using neurofilament immunohistochemistry renders chemical phenotyping more precise in porcine ileum. Histochem Cell Biol 117(3):257–263

Brehmer A, Blaser B, Seitz G, Schrödl F, Neuhuber W (2004a) Pattern of lipofuscin pigmentation in nitrergic and non-nitrergic, neurofilament immunoreactive myenteric neuron types of human small intestine. Histochem Cell Biol 121(1):13–20

Brehmer A, Croner R, Dimmler A, Papadopoulos T, Schrödl F, Neuhuber W (2004b) Immunohistochemical characterization of putative primary afferent (sensory) myenteric neurons in human small intestine. Auton Neurosci 112(1–2):49–59

Brehmer A, Lindig TM, Schrödl F, Neuhuber W, Ditterich D, Rexer M, Rupprecht H (2005) Morphology of enkephalin-immunoreactive myenteric neurons in the human gut. Histochem Cell Biol 123(2):131–138

Brehmer A, Schrödl F, Neuhuber W (2006) Morphology of VIP/nNOS-immunoreactive myenteric neurons in the human gut. Histochem Cell Biol 125(5):557–565

Brehmer A, Rupprecht H, Neuhuber W (2010) Two submucosal nerve plexus in human intestines. Histochem Cell Biol 133(2):149–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00418-009-0657-2

Brookes S (2001) Retrograde tracing of enteric neuronal pathways. Neurogastroenterol Motil 13(1):1–18

Brookes SJ, Ewart WR, Wingate DL (1987) Intracellular recordings from myenteric neurones in the human colon. J Physiol 390:305–318. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016702

Brookes SJ, Song ZM, Ramsay GA, Costa M (1995) Long aboral projections of Dogiel type II, AH neurons within the myenteric plexus of the guinea pig small intestine. J Neurosci 15(5 Pt 2):4013–4022

Brown DR, Timmermans JP (2004) Lessons from the porcine enteric nervous system. Neurogastroenterol Motil 16(Suppl 1):50–54

Carbone SE, Jovanovska V, Nurgali K, Brookes SJ (2014) Human enteric neurons: morphological, electrophysiological, and neurochemical identification. Neurogastroenterol Motil 26(12):1812–1816. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.12453

Chiocchetti R, Grandis A, Bombardi C, Lucchi ML, Dal Lago DT, Bortolami R, Furness JB (2006) Extrinsic and intrinsic sources of calcitonin gene-related peptide immunoreactivity in the lamb ileum: a morphometric and neurochemical investigation. Cell Tissue Res 323(2):183–196

Chiocchetti R, Bombardi C, Mongardi-Fantaguzzi C, Venturelli E, Russo D, Spadari A, Montoneri C, Romagnoli N, Grandis A (2009) Intrinsic innervation of the horse ileum. Res Vet Sci 87(2):177–185

Clarke E, O´Malley CD (1996) The human brain and spinal cord. A historical study illustrated by writings from antiquity to the twentieth century. Norman Publishing, San Francisco

Costa M, Brookes SJ, Steele PA, Gibbins I, Burcher E, Kandiah CJ (1996) Neurochemical classification of myenteric neurons in the guinea-pig ileum. Neuroscience 75(3):949–967

Costa M, Keightley LJ, Hibberd TJ, Wiklendt L, Dinning PG, Brookes SJ, Spencer NJ (2021) Motor patterns in the proximal and distal mouse colon which underlie formation and propulsion of feces. Neurogastroenterol Motil. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.14098

Dogiel AS (1899) Ueber den Bau der Ganglien in den Geflechten des Darmes und der Gallenblase des Menschen und der Säugethiere. Arch Anat Physiol Anat Abt (Leipzig):130–158

Filzmayer AK, Elfers K, Michel K, Buhner S, Zeller F, Demir IE, Theisen J, Schemann M, Mazzuoli-Weber G (2020) Compression and stretch sensitive submucosal neurons of the porcine and human colon. Sci Rep 10(1):13791. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-70216-6

FIPAT (2017) Terminologia Neuroanatomica. FIPAT.library.dal.ca. Federative International Programme for Anatomical Terminology

Freytag C, Seeger J, Siegemund T, Grosche J, Grosche A, Freeman DE, Schusser GF, Hartig W (2008) Immunohistochemical characterization and quantitative analysis of neurons in the myenteric plexus of the equine intestine. Brain Res 1244:53–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2008.09.070

Fung C, Vanden Berghe P (2020) Functional circuits and signal processing in the enteric nervous system. Cell Mol Life Sci 77(22):4505–4522. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-020-03543-6

Furness JB (2006) The enteric nervous system. Blackwell, Oxford

Furness JB, Costa M (1987) The enteric nervous system. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh

Furness JB, Costa M, Gibbins IL, Llewellyn-Smith IJ, Oliver JR (1985) Neurochemically similar myenteric and submucous neurons directly traced to the mucosa of the small intestine. Cell Tissue Res 241(1):155–163

Furness JB, Bornstein JC, Trussell DC (1988) Shapes of nerve cells in the myenteric plexus of the guinea-pig small intestine revealed by the intracellular injection of dye. Cell Tissue Res 254(3):561–571

Furness JB, Trussell DC, Pompolo S, Bornstein JC, Smith TK (1990) Calbindin neurons of the guinea-pig small intestine: quantitative analysis of their numbers and projections. Cell Tissue Res 260(2):261–272

Furness JB, Kunze WA, Bertrand PP, Clerc N, Bornstein JC (1998) Intrinsic primary afferent neurons of the intestine. Prog Neurobiol 54(1):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0301-0082(97)00051-8

Furness JB, Alex G, Clark MJ, Lal VV (2003) Morphologies and projections of defined classes of neurons in the submucosa of the guinea-pig small intestine. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol 272(2):475–483. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.a.10064

Furness JB, Robbins HL, Xiao J, Stebbing MJ, Nurgali K (2004) Projections and chemistry of Dogiel type II neurons in the mouse colon. Cell Tissue Res 317(1):1–12

Furness JB, Di Natale M, Hunne B, Oparija-Rogenmozere L, Ward SM, Sasse KC, Powley TL, Stebbing MJ, Jaffey D, Fothergill LJ (2020) The identification of neuronal control pathways supplying effector tissues in the stomach. Cell Tissue Res 382(3):433–445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-020-03294-7

Ganns D, Schrödl F, Neuhuber W, Brehmer A (2006) Investigation of general and cytoskeletal markers to estimate numbers and proportions of neurons in the human intestine. Histol Histopathol 21(1):41–51

Garcia-Lopez P, Garcia-Marin V, Freire M (2010) The histological slides and drawings of Cajal. Front Neuroanat 4:9. https://doi.org/10.3389/neuro.05.009.2010

Hendriks R, Bornstein JC, Furness JB (1990) An electrophysiological study of the projections of putative sensory neurons within the myenteric plexus of the guinea pig ileum. Neurosci Lett 110(3):286–290

Hens J, Vanderwinden JM, De Laet MH, Scheuermann DW, Timmermans JP (2001) Morphological and neurochemical identification of enteric neurones with mucosal projections in the human small intestine. J Neurochem 76(2):464–471

Humenick A, Chen BN, Lauder CIW, Wattchow DA, Zagorodnyuk VP, Dinning PG, Spencer NJ, Costa M, Brookes SJH (2019) Characterization of projections of longitudinal muscle motor neurons in human colon. Neurogastroenterol Motil 31(10):e13685. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.13685

Humenick A, Chen BN, Wattchow DA, Zagorodnyuk VP, Dinning PG, Spencer NJ, Costa M, Brookes SJH (2021) Characterization of putative interneurons in the myenteric plexus of human colon. Neurogastroenterol Motil 33(1):e13964. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.13964

Jabari S, de Oliveira EC, Brehmer A, da Silveira AB (2014) Chagasic megacolon: enteric neurons and related structures. Histochem Cell Biol 142(3):235–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00418-014-1250-x

Kapp S, Schrödl F, Neuhuber W, Brehmer A (2006) Chemical coding of submucosal type V neurons in porcine ileum. Cells Tissues Organs 184(1):31–41

Koelliker A (1896) Handbuch der Gewebelehre des Menschen. 2. Bd.: Nervensystem des Menschen und der Thiere. Engelmann, Leipzig

Kugler EM, Michel K, Zeller F, Demir IE, Ceyhan GO, Schemann M, Mazzuoli-Weber G (2015) Mechanical stress activates neurites and somata of myenteric neurons. Front Cell Neurosci 9:342. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2015.00342

Kustermann A, Neuhuber W, Brehmer A (2011) Calretinin and somatostatin immunoreactivities label different human submucosal neuron populations. Anat Rec (hoboken) 294(5):858–869. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.21365

Lindig ML, Kumar V, Kikinis R, Pieper S, Schrödl F, Neuhuber WL, Brehmer A (2009) Spiny versus stubby: 3D reconstruction of human myenteric (type I) neurons. Histochem Cell Biol 131:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00418-008-0505-9

Lomax AE, Furness JB (2000) Neurochemical classification of enteric neurons in the guinea-pig distal colon. Cell Tissue Res 302(1):59–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004410000260

Mazzoni M, Caremoli F, Cabanillas L, de Los SJ, Million M, Larauche M, Clavenzani P, De Giorgio R, Sternini C (2020) Quantitative analysis of enteric neurons containing choline acetyltransferase and nitric oxide synthase immunoreactivities in the submucosal and myenteric plexuses of the porcine colon. Cell Tissue Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-020-03286-7

Meissner G (1857) Über die Nerven der Darmwand. Z Ration Med N F 8:364–366

Melo CGS, Nicolai EN, Alcaino C, Cassmann TJ, Whiteman ST, Wright AM, Miller KE, Gibbons SJ, Beyder A, Linden DR (2020) Identification of intrinsic primary afferent neurons in mouse jejunum. Neurogastroenterol Motil 32(12):e13989. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.13989

Mitsui R (2009) Characterisation of calcitonin gene-related peptide-immunoreactive neurons in the myenteric plexus of rat colon. Cell Tissue Res 337(1):37–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-009-0798-6

Mitsui R (2010) Immunohistochemical characteristics of submucosal Dogiel type II neurons in rat colon. Cell Tissue Res 340(2):257–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-010-0954-z

Mongardi Fantaguzzi C, Thacker M, Chiocchetti R, Furness JB (2009) Identification of neuron types in the submucosal ganglia of the mouse ileum. Cell Tissue Res 336(2):179–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-009-0773-2

Murphy EM, Defontgalland D, Costa M, Brookes SJ, Wattchow DA (2007) Quantification of subclasses of human colonic myenteric neurons by immunoreactivity to Hu, choline acetyltransferase and nitric oxide synthase. Neurogastroenterol Motil 19(2):126–134

Noorian AR, Taylor GM, Annerino DM, Greene JG (2011) Neurochemical phenotypes of myenteric neurons in the rhesus monkey. J Comp Neurol 519(17):3387–3401. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.22679

Nurgali K (2009) Plasticity and ambiguity of the electrophysiological phenotypes of enteric neurons. Neurogastroenterol Motil 21(9):903–913. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01329.x

Nurgali K, Stebbing MJ, Furness JB (2004) Correlation of electrophysiological and morphological characteristics of enteric neurons in the mouse colon. J Comp Neurol 468(1):112–124

Petto C, Gabel G, Pfannkuche H (2015) Architecture and Chemical Coding of the Inner and Outer Submucous Plexus in the Colon of Piglets. PLoS ONE 10(7):e0133350. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0133350

Pimont S, Bruley Des Varannes S, Le Neel JC, Aubert P, Galmiche JP, Neunlist M (2003) Neurochemical coding of myenteric neurones in the human gastric fundus. Neurogastroenterol Motil 15(6):655–662

Portbury AL, Pompolo S, Furness JB, Stebbing MJ, Kunze WA, Bornstein JC, Hughes S (1995) Cholinergic, somatostatin-immunoreactive interneurons in the guinea pig intestine: morphology, ultrastructure, connections and projections. J Anat 187(Pt 2):303–321

Porter AJ, Wattchow DA, Brookes SJ, Costa M (1997) The neurochemical coding and projections of circular muscle motor neurons in the human colon. Gastroenterology 113(6):1916–1923

Porter AJ, Wattchow DA, Brookes SJ, Costa M (1999) Projections of nitric oxide synthase and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide-reactive submucosal neurons in the human colon. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 14(12):1180–1187

Porter AJ, Wattchow DA, Brookes SJ, Costa M (2002) Cholinergic and nitrergic interneurones in the myenteric plexus of the human colon. Gut 51(1):70–75

Qu ZD, Thacker M, Castelucci P, Bagyanszki M, Epstein ML, Furness JB (2008) Immunohistochemical analysis of neuron types in the mouse small intestine. Cell Tissue Res 334(2):147–161

Ramón y Cajal (1911) Histologie du système nerveux de l’homme et des vertébrés. Maloine, Paris

Rossi O (1929) Contributo alla conoscenza degli apparati nervosi intramurali dell’ intestino tenue. Arch Ital Anat 26:632–644

Sang Q, Williamson S, Young HM (1997) Projections of chemically identified myenteric neurons of the small and large intestine of the mouse. J Anat 190(Pt 2):209–222

Sayegh AI, Ritter RC (2003) Morphology and distribution of nitric oxide synthase-, neurokinin-1 receptor-, calretinin-, calbindin-, and neurofilament-M-immunoreactive neurons in the myenteric and submucosal plexuses of the rat small intestine. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol 271(1):209–216. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.a.10024

Schabadasch A (1930) Intramurale Nervengeflechte des Darmrohrs. Z Zellforsch Mikrosk Anat 10:320–385

Schemann M, Neunlist M (2004) The human enteric nervous system. Neurogastroenterol Motil 16(Suppl 1):55–59

Schemann M, Reiche D, Michel K (2001) Enteric pathways in the stomach. Anat Rec 262(1):47–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0185(20010101)262:1%3c47::AID-AR1010%3e3.0.CO;2-1

Scheuermann DW, Stach W, De Groodt-Lasseel MH, Timmermans JP (1987) Calcitonin gene-related peptide in morphologically well-defined type II neurons of the enteric nervous system in the porcine small intestine. Acta Anat (basel) 129(4):325–328

Schuy J, Schlabrakowski A, Neuhuber W, Brehmer A (2011) Quantitative estimation and chemical coding of spiny type I neurons in human intestines. Cells Tissues Organs 193:195–206. https://doi.org/10.1159/000320542

Smarandache-Wellmann CR (2016) Arthropod neurons and nervous systems. Curr Biol 26(20):R960–R965. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2016.07.063

Smolilo DJ, Hibberd TJ, Costa M, Wattchow DA, De Fontgalland D, Spencer NJ (2020) Intrinsic sensory neurons provide direct input to motor neurons and interneurons in mouse distal colon via varicose baskets. J Comp Neurol 528(12):2033–2043. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.24872

Sokolova ML (1931) Zur Lehre von der Cytoarchitektonik des peripherischen autonomen Nervensystems. II. Die Architektur der intramuralen Ganglien des Verdauungstrakts des Rindes. Z Mikrosk Anat Forsch 23:552–570

Song ZM, Brookes SJ, Costa M (1994) All calbindin-immunoreactive myenteric neurons project to the mucosa of the guinea-pig small intestine. Neurosci Lett 180(2):219–222

Spencer NJ, Hu H (2020) Enteric nervous system: sensory transduction, neural circuits and gastrointestinal motility. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 17(6):338–351. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-020-0271-2

Spencer NJ, Smith TK (2004) Mechanosensory S-neurons rather than AH-neurons appear to generate a rhythmic motor pattern in guinea-pig distal colon. J Physiol 558(Pt 2):577–596. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2004.063586

Stach W (1977) The external submucous plexus (Schabadasch) in the small intestine of the swine. I. Form, structure and connections of ganglia and nerve cells. Z Mikrosk Anat Forsch 91(4):737–755

Stach W (1980) Neuronal organization of the myenteric plexus (Auerbach) in the small intestine of the pig. I. Type I neurons. Z Mikrosk Anat Forsch 94(5):833–849

Stach W (1981) The neuronal organization of the plexus myentericus (Auerbach) in the small intestine of the pig. II. Typ II-neurone (author’s transl). Z Mikrosk Anat Forsch 95(2):161–182

Stach W (1982a) Neuronal organization of the myenteric plexus (Auerbach) in the swine small intestine. III. Type III neurons. Z Mikrosk Anat Forsch 96(3):497–516

Stach W (1982b) Neuronal organization of the plexus myentericus (Auerbach) in the small intestine of the pig. IV. Type IV-Neurons. Z Mikrosk Anat Forsch 96(6):972–994

Stach W (1985) Neuronal organization of the myenteric plexus (Auerbach’s) in the pig small intestine. V. Type-V neurons. Z Mikrosk Anat Forsch 99(4):562–582

Stach W (1989) A revised morphological classification of neurons in the enteric nervous system. In: Singer MV, Goebell H (eds) Nerves and the gastrointestinal tract. Kluwer, Lancaster, pp 29–45

Stach W, Krammer HJ, Brehmer A (2000) Structural organization of enteric nerve cells in large mammals including man. In: Krammer HJ, Singer MV (eds) Neurogastroenterology from the basics to the clinics. Kluwer, Dordrecht, pp 3–20

Stöhr P (1949) Mikroskopische Studien zur Innervation des Magen-Darmkanales V. Z Zellforsch Mikrosk Anat 34:1–54

Timmermans JP, Barbiers M, Scheuermann DW, Stach W, Adriaensen D, Mayer B, De Groodt-Lasseel MH (1994) Distribution pattern, neurochemical features and projections of nitrergic neurons in the pig small intestine. Ann Anat 176(6):515–525

Timmermans JP, Hens J, Adriaensen D (2001) Outer submucous plexus: an intrinsic nerve network involved in both secretory and motility processes in the intestine of large mammals and humans. Anat Rec 262(1):71–78

Vickers JC, Costa M (1992) The neurofilament triplet is present in distinct subpopulations of neurons in the central nervous system of the guinea-pig. Neuroscience 49:73–100

Wattchow DA, Brookes SJ, Costa M (1995) The morphology and projections of retrogradely labeled myenteric neurons in the human intestine. Gastroenterology 109(3):866–875

Wattchow DA, Porter AJ, Brookes SJ, Costa M (1997) The polarity of neurochemically defined myenteric neurons in the human colon. Gastroenterology 113(2):497–506

Weidmann S, Schrödl F, Neuhuber W, Brehmer A (2007) Quantitative estimation of putative primary afferent neurons in the myenteric plexus of human small intestine. Histochem Cell Biol 128(5):399–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00418-007-0335-1

Wolf M, Schrödl F, Neuhuber W, Brehmer A (2007) Calcitonin gene-related peptide: a marker for putative primary afferent neurons in the pig small intestinal myenteric plexus? Anat Rec (hoboken) 290(10):1273–1279. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.20577

Wong V, Blennerhassett M, Vanner S (2008) Electrophysiological and morphological properties of submucosal neurons in the mouse distal colon. Neurogastroenterol Motil 20(6):725–734

Wood JD (1994) Physiology of the enteric nervous system. In: Johnson LR (ed) Physiology of the gastrointestinal tract. Raven Press, New York, pp 423–482

Yuan PQ, Bellier JP, Li T, Kwaan MR, Kimura H, Tache Y (2021) Intrinsic cholinergic innervation in the human sigmoid colon revealed using CLARITY, three-dimensional (3D) imaging, and a novel anti-human peripheral choline acetyltransferase (hpChAT) antiserum. Neurogastroenterol Motil 33(4):e14030. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.14030

Zetzmann K, Strehl J, Geppert C, Kuerten S, Jabari S, Brehmer A (2018) Calbindin D28k-Immunoreactivity in Human Enteric Neurons. Int J Mol Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19010194

Acknowledgements

Many thanks go to Karin Löschner and Stephanie Link for excellent technical assistance, to Winfried Neuhuber, Lars Fester and Steve Dunne for critically reading the manuscript and to Siegfried Richter for help with the graphics (all Erlangen, Germany). Furthermore, I am thankful for previous financial support by the Johannes and Frieda Marohn-Stiftung (Breh/99) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (BR 1815/3; /4). I am grateful to all patients and body donors who permitted us to study human tissues. Related procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Erlangen-Nürnberg (reference number 2550). Together with friends and relatives, I mourn and remember Bernhard Beleites (Rostock, Germany).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

No conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Brehmer, A. Classification of human enteric neurons. Histochem Cell Biol 156, 95–108 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00418-021-02002-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00418-021-02002-y