Abstract

A recurring discussion in recent health studies relates to knowledge translation (KT), which deals with the questions of how to ensure and measure the uptake of knowledge from one medical situation to another and of how to move the right form of knowledge from one situation to another. Recently, however, this way of understanding KT has received criticism for presenting too basic an understanding of knowledge and not fully grasping the potential of the term translation. Based on qualitative material from a randomised controlled trial (RCT) and a follow-up study, this article takes the current discussion of KT one step further, focussing on how KT happens among healthy citizens participating in a lifestyle intervention. The overall argument is that even current critical understandings of KT often ignore the fact that the translation of medical knowledge does not stop at the clinical encounter but extends into the everyday health practices of the population. A more nuanced understanding of how and in which forms medical knowledge is adopted by people in their everyday health practices will give new insights into the complex mechanisms of KT and the encounter between medical knowledge and practice and everyday life. Hence, this article discuss how knowledge from a clinical trial—focussing on muscular training and increased protein intake—is translated into meaningful health practices. The article concludes the following points: First, constant, and often precarious, work is required to maintain the content of ‘medical knowledge’ in a complex social order. Second, focussing on translation work in everyday life emphasises that KT is an open-ended process, wherein the medical object of knowledge is contested and renegotiated and needs alliances with other objects of knowledge in order to remain relevant. Last, from an everyday life perspective, medical knowledge is just one rationale making up the fabric of people’s health practices; other rationales, such as time, feasibility, logistics and social relations, are just as relevant in determining how and why people pursue healthy living or comply with a medical regimen. CALM trial registration ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02034760. Registered on 10 January 2014; ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02115698. Registered on 14 April 2014; Danish regional committee of the Capital Region H-4-2013-070. Registered on 4 July 2013; Danish Data Protection Agency 2012-58-0004–BBH-2015-001 I-Suite 03432. Registered on 9 January 2015.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A recurring subject of discussion in recent health studies is that of knowledge translation (KT). This discussion deals with the questions of how to ensure and measure the uptake of knowledge from one medical situation to another and of how to move the right form of knowledge from one situation to another (Straus et al., 2010). Typically, this is presented as the challenge of moving evidence-based research into clinical practice without altering or distorting the core content of the research while also making the knowledge practically useful. In this depiction of KT, knowledge is presented as a given that can and should be transported and, hence, adopted in clinical practice. Recently, however, this way of understanding KT has received criticism for presenting too basic an understanding of knowledge and not fully grasping the potential of the term translation. It has therefore been argued that our understanding and practices of KT should be broadened to allow for different kinds of knowledge and a more situated way of viewing translation (see Engebretsen et al., 2017; Greenhalgh and Wieringa, 2011).

According to Greenhalgh and Wieringa (2011), KT relies on some misunderstood—or at least contested—assumptions regarding the nature of knowledge. First, KT takes knowledge to be translatable due to its objective qualities. In this line of thought, knowledge is separate from the research process and, hence, can be transferred and translated unproblematically across practices due to its objectivity. Second, KT assumes that knowing and doing are two distinct actions, whereas others would view doing as something that creates practice-specific knowledge (i.e., know-how). Third, KT takes practice as informed by rational decisions based on knowledge, which does not account for the social dynamics, power relations and situatedness of both knowledge and its translation into practice (Greenhalgh and Wieringa, 2011). The critique of KT raised by Greenhalgh and Wieringa points to a reorientation towards a more situated understanding of knowledge, wherein knowledge should not be viewed as merely transported from bench to bedside but as undergoing a series of translations in the process. These translations are situation-specific and rely on practical wisdom that is currently not part of the primarily medical research on KT but that plays a crucial role in determining how a layperson will negotiate and translate the knowledge provided by medical doctors.

As such, KT is not just an endeavour to seek optimal pathways for the transportation of knowledge from one medical source to another but is a field for exploring and discussing, in detail, the reformations of knowledge and the involved translation practices. While Greenhalgh and Wieringa’s (2011) analysis is indeed necessary in developing a more adequate and practically sensitive understanding of KT, the discussion still mostly focusses on the relationship between the clinical practitioner of medicine and evidence-based research. In this regard, it is important to note that KT occurs in many situations and medical practices. It is performed not only in encounters between patients and medical doctors at general practitioners’ (GPs’) offices or hospitals focussed on treatment but also in health prevention programmes, in chronic disease management, in health campaigns, in domestic health care practices and in trials, although these practices have been less studied as cases of KT. The point is that wherever there is a health-oriented practice, this practice is scaffolded by knowledge translated through implicit, divergent and ambiguous pathways.

With this article, we propose the inclusion of analyses of other spheres wherein KT occurs, to include other stances towards the relations between medicine and practice, and to broaden the scope to not just critique the notion of knowledge applied by current understandings of KT, but also its notion of translation.

Based on qualitative material from a randomised controlled trial (RCT) and a follow-up study, we take the current discussion of KT one step further and focus on how the ‘uptake’ of knowledge happens among healthy citizens participating in a lifestyle intervention focussing on physical activity. Our overall argument is that even current critical understandings of KT often ignore the fact that the translation of medical knowledge does not stop at the clinical practice/encounter but extends into the everyday health practices of the population. We recognise that our case is not a classic KT case, as our material stems from a research project; however, what our case offers is a crucial additional part of the translation of medical knowledge. A more nuanced understanding of how and in which forms medical knowledge is adopted by people in their everyday health practices will give new insight into the complex mechanisms of KT. Hence, in this article, we discuss how knowledge from a clinical trial is translated into the meaningful health practices of research participants in a Danish clinical trial.

After presenting the theoretical, methodological and contextual considerations, we describe this kind of translation using qualitative data deriving from an RCT in Denmark. The RCT focussed on the protein and meals as well as the muscular exercise practices of Danish retirees. We map how these specific intervention formats are translated and converted in very different ways into everyday practices. First, we show how the focus on protein in the project is translated into a broader focus on healthy food in seemingly arbitrary ways linked to participants’ everyday lives. Second, we show how the emphasis on muscular exercise leads to a general highlighting of physical activity, coupled with an increased interest in muscular exercise among participants. We argue that the different ways in which these two foci are translated into everyday life by the participants is linked to the different ways the recommendations and activities are attached to or detached from their pre-existing health practices.

Compliance, concordance and attachment: the complex relation between biomedicine and everyday life

The translation of clinical guidelines and GPs’ advice to citizens regarding their everyday lives and habits have been dealt with in various ways within medicine. In particular, the concept of compliance has been used to describe the degree to which a patient complies with a medical regimen (Haynes et al., 1979). More recently, the concept of concordance—in line with current tendencies to emphasise patient empowerment and doctor–patient negotiation—has gained ground as a more appropriate way to label the dynamics between healthcare professionals, individuals and communities (World Health Organization [WHO], 2003). However, both these notions have been criticised for suggesting the possibility of a unidirectional transfer of biomedical knowledge into everyday life and for configuring lifestyles as being composed of measurable, modifiable risk factors (Niewöhner et al., 2011) that can be singled out and correlated with the prevailing health standards (Cohn, 2014). According to the criticism, compliance and its related concepts tend to overlook the way in which the uptake of medical advice and treatment regimens in everyday life is made possible through and constrained by heterogeneous compositions of diverse actors (Moreira, 2004; Jespersen et al., 2014); the fact that everyday life is techno-scientifically saturated and entangled in various ways (Kontopodis et al., 2011); and the fact that health standards themselves are amenable to modifications and re-configurations (Timmermans and Epstein, 2010).

In a study focussing on the amount of practical work required of the research participants in a clinical trial, the compliance figure is described as being dependent upon the situational and shifting possibilities of everyday life practices (Winther, 2017, 2018). The ongoing and often hidden work that research participants undertake in adhering to the requirements of a trial in order to ensure its success has only recently come into focus and, perhaps more importantly, has only recently been acknowledged as key to understanding the complex relationship between biomedical knowledge and everyday life. With this paper, we aim to provide a more sensitive understanding and acknowledgement of the workings of everyday life as key to developing KT and clinical practices.

The reasons KT is seen as relevant for studies of medicine in everyday life relate to its invocation of the concepts of both knowledge and translation. Both concepts have been central to the formation of the field of science and technology studies (STS); the field has contributed to these concepts by offering a more complex notion of translation and by showing how knowledge is always situated, negotiated and in-the-making (Latour, 1987; Mol, 2008; Mol et al., 2010) and how translation always entails a transformation. And according to John Law the process of transformation also inevitably entails some sort of ‘trahison’, that is a more or less subtle shift of meaning of the translated object, evidence or practice. The ideal of similarity from one situation to another embedded in translation is impossible. Difference between the original and the translation is inevitably evoked and trahison necessarily occurs in this process (Law, 2003). By emphasising the transformation and trahison aspects, translation is described as a form of mediation that simultaneously transports and disrupts a signal. As such, it is an event in which an entity (e.g., an object, actor, knowledge or system) is moved and changed, and this process creates patterns of order and disorder (Brown, 2002).

Thus, what we wish to contribute to KT is to show that when medical knowledge is translated into everyday practices, it changes (once more). The process of translation is an active modification of the biomedical knowledge. When knowledge changes site, it is resituated and renegotiated. The ‘new’ practices, of which the renegotiated knowledge will be part, are active partners in the modification. Understanding KT in this sense thus emphasises the active engagement and entanglement of biomedical practice with the everyday life practices of the patients, citizens and/or research participants.

The process of appropriating and domesticising new health practices following a medical intervention has been proposed by Moreira (2004) to be mediated through a process of first attaching to the intervention regimen and its requirements. When the intervention stops and is withdrawn from participants’ everyday practices, a process of detachment and reattachment to everyday life takes over. Moreira suggests that when the subject is detached from the intervention -in this case, during surgical rehabilitation—a shift in the conditions for agency occurs. In other words, when the research participants are detached from the trial, they use their new knowledge to act in the world and attach their new knowledge to existing practices when it partly corresponds with those practices.

Based on this, we propose that the process of appropriating and domesticising new health practices could be seen as a form of detachment, attachment and reattachment. In the RCT analysed in this study, the research participants are momentarily detached from their existing practices—in this case their eating and exercise practices—and attached to the specific kinds of knowledge related to the RCT. When the participants are done with the RCT protocol, they are detached from the RCT and reattached to their existing practices. A different kind of KT occurs, wherein the research participants attach the knowledge from the RCT to their know-how and knowledge related to their existing practices. In this reattachment, the knowledge from the RCT is negotiated, translated and thus transformed. With this approach to KT, we are inspired by the sociology of attachment (Gomart and Hennion, 1999), which views subjects as networks emerging through their attachments to, for example, social relationships, techniques, abilities, objects and events (such as clinical trials). Hence, when the participants are detached from the trial and reattached to their daily practices, the knowledge from the RCT becomes part of a (new) network of attachments and embark on processes of translation, that renegotiate the knowledge in the context of everyday life. As such, the focus on attachment highlights how the process of translation relies on a multitude of connections and networks in everyday life.

In the following analysis, we apply these dynamic processes of attachment and detachment to our material, as this enables us to describe the specific socio-material networks, conditions and strategies developed for adopting the knowledge and experience gained from participating in a health intervention into health practices in everyday life.

Methods

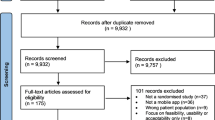

This paper is based on data from a Danish interdisciplinary research project, CALM, which investigated how to counteract age-related loss of skeletal muscle mass before the onset of age-related diseases. As a project centred on an RCT focussing on the health outcomes of improved physical activity and dietary practices in everyday life, CALM can be viewed as part of a widespread health promotion effort to produce robust health interventions together with rigid evidence that can be translated into the ‘real world’ of the population (Winther, 2017). In the CALM RCT, 205 research participants over the age of 65 years were randomised into 5 groups focussing on physical activity and protein intake. The trial took place at the Institute for Sports Medicine, Bispebjerg Hospital, in Copenhagen; hence, it was medical doctors and students from the health sciences who did the daily procedures related to the trial and the participants.

The participants were enroled through a 12-month intervention and a follow-up study that took place 6 months after the intervention. Participants were recruited through newspapers, social media, and networking at senior centres in the greater Copenhagen area. There were 18 exclusion criteria, which ensured that only relatively healthy participants, who at the same time did not exercise vigorously, were included. Moreover, the participants represent a sub-group of the older Danish population with a higher level of education, income and health than average (see Bechshøft et al., 2016; Lassen et al., 2020 for a detailed description).

During the intervention and follow-up, the participants were subject to physiological and microbiological tests, as well as ethnological analyses (Bechshøft et al., 2016). Furthermore, CALM included an innovation project that challenged and tested knowledge and assumptions from the RCT in a range of experimental workshops, together with a subsample of the research participants and other retirees, focussing on health perceptions and practices, daily routines and rhythms, physical activity, food and perceptions of protein (Lassen et al., 2020).

We participated in the CALM study as ethnologists, exploring the impact of the trial on the participants’ everyday health practices and investigating the ongoing work and negotiations between the trial researchers and apparatus and the participants, which was needed to keep the intervention on track. Our participation began at the time of the project proposal, and hence, the ethnographic approach was integrated in various ways in the design of the RCT and follow-up study, and we were leading partners in the innovation project. As qualitative researchers, we were particularly interested in understanding the logics and practices of the trial and how they impacted the participants’ trajectories and experiences. Furthermore, as ethnographic methods are agile and mobile, we were able to follow the participants in other settings and practices outside the RCT in order to observe how the particular regimens and requirements of the RCT were handled in the participants’ everyday life. At the follow-up study, we were in particular interested in understanding how the participants viewed their participation in hindsight, and how (if at all) their exercise and eating practices had changed.

The qualitative material from CALM consists of a varied data sample. All participants (n = 205) in the RCT were interviewed at baseline and at follow-up, 6 months after the intervention. The interviews lasted between 5 and 15 min, following standardised interview guides—one for the baseline and one for the follow-up—and were conducted by the trial staff as part of the test days at the clinic. As part of the intervention, we conducted ethnographic fieldwork, observations and semi-structured interviews, with a sub-sample of participants (n = 84) focussing on health perceptions, ageing processes and everyday life (Otto, 2019). The innovation part of the study was organised around six experimental workshops: three focussed on eating practices and protein, and three focussed on physical activity practices. For each theme, one workshop contained participants from the RCT. The material from the workshops consisted of focus group interviews, fieldnotes, drawings from the participants and photos. At the follow-up, we conducted ethnographic fieldwork (participant observations and interviews) with a small sub-sample from the training groups (n = 5), focussing on the participants’ training and eating practices after CALM. Informed consent were obtained in writing from the informants and the project was reported to and approved by the regional ethics committee.

All the qualitative data was transcribed verbatim, and was manually coded and thematised using an inductive approach (Creswell and Poth, 2017), in which major underlying patterns and themes were identified. We tested that the intercoder reliability was sufficiently high. In this paper, we draw on the qualitative data from the training groups only (n = 70)—that is, 2 of the 5 intervention groups—and we primarily use material from the baseline interviews and follow-up study (i.e., interviews and fieldwork). For this paper we focus on coded themes such as continuation strategies, barriers to maintaining the exercise regimen, translation strategies regarding muscle-training and protein, changes in eating practices, social support related to exercise and eating, participants assessment of potential benefits of participating, and participants criticism of the trial. The quotes in the article refers to the analytical themes and were chosen as particular illustrative for our analytical points. The participants quoted in this article are referred to using pseudonyms.

CALM: adhering to the requirements of an RCT

One way of approaching the types of knowledge that are produced, negotiated and translated in the CALM case is to first understand the requirements of the trial and how the participants were recruited, enroled and disciplined in the trial process (see Fig. 1)—in other words, how the participants became attached to the trial and how the biomedical requirements and the specific intervention formats (muscular exercise and protein) were presented to them. The following figure is an overview of the CALM process.

After the initial screening, testing and randomisation, the two exercise groups—that is, the heavy resistance training and whey supplement group (HRTW) and the light-intensity resistance training and whey supplement group (LITW)—each had to follow their exercise scheme. The participants in the HRTW group had to conduct centre-based heavy resistance training three times a week, focussing on both lower- and upper-body exercises. The participants were invited to use the facilities at the trial campus in groups, and the training sessions were supervised by a physiotherapist. The participants in the LITW group had to perform the training at home and alone, phasing in workouts over the first month with weekly instructions and adaptations. The participants in this group were instructed to use training rubber bands, as well as furniture and walls, as tools for the exercises, and they were expected to train between three and five times a week (with an average of four times) (Bechshøft et al., 2016). Every 3 months (i.e., at month 0, 3, 6, 9 and 12), the participants were approached by the trial staff (either by invitation to the campus or by receiving letters containing the material) to conduct different types of biomedical and other tests, such as functional tests, blood and faecal samples, biopsies, questionnaires and interviews. In both groups, participants were taking 20 grams of whey protein via protein powder twice daily. The protein was consumed in a shake (resolved in water or juice) prior to meals or immediately after training sessions (Bechshøft et al., 2016).

On one hand, CALM adhered to the gold standard of RCTs by using a rigid methodology of principles and procedures such as randomisation, testing and monitoring, which enabled the project to measure and validate specific biomedical outcomes of the induced regiments (Timmermans and Berg, 2003). On the other hand, CALM intervened in the participants’ everyday lives, as do many other current health interventions, making the trial dependent on the disciplined compliance of the participants. This ambiguity between rigid methodology and complex, sometimes unpredictable, everyday life requires ongoing conversation, negotiation and relation work between the trial and the participants. This is maintained through a set of monitoring tools and points of contact such as test days, accelerometers, training schemes, email contact and phone calls. On test days, the participants’ engagement—or, in clinical terms, compliance—was evaluated through different biomedical measurements, compliance data and dialogue between the research staff and the participants. Typically, the dialogue focussed on the participants’ motivation or lack thereof, the obstacles to meeting the requirements and the possible solutions to these challenges. This ongoing monitoring, tinkering and care work was a constant reaffirmation of the attachments between the trial and the participants, and a crucial part of this was the sanctioning of the key objects of knowledge (i.e., muscular exercise and protein) (Jespersen et al., 2014). However, this constant reaffirmation of the ‘contract’ between the participants and the trial does not in itself guarantee success. The participants must also perform what Mattingly et al. (2011) describe as ‘homework’, highlighting the situated and creative ways the participants actively participated in the attachment process, by making the requirements of the trial fit into their lives. CALM, as a health intervention, extends into and interfere with the participants’ everyday lives, and the development of strategies for knowledge translation are therefore involved from the onset of the trial.

When the intervention period ended, after 12 months, the monitoring set-up, testing and dialogue stopped. The participants were left alone with the decision to continue the regimen, transform it into something else or discontinue it altogether. At this point, the requirements of the trial had to be translated into feasible and meaningful parts of the participants’ daily activities. In the following analysis, we provide an account of the strategies and practical work that the participants developed and enacted when the responsibility to maintain the knowledge and experience gained by being part of CALM was left to themselves. We follow the two major objects of interest (and knowledge) in the trial—namely, that related to protein and muscular exercise—in order to observe how these were transported and reshaped to become meaningful health practices for the participants.

Results

Translating/transforming protein

When knowledge and guidelines about protein from the RCT was situated in the everyday practices of participants, both during and after the trial, it was detached from the clinical setting and attached to the pre-existing ways in which the participants managed their diet, food and meals.

For many participants in both groups, the focus on protein was understood as and transformed into a more general focus on healthy food. Because the participants’ idea of healthy food was, for many, informed by the Danish general food recommendations and the current cultural ideal of a varied and green diet, many participants had begun to eat more vegetables during and after the trial. One participant, Tina, explained the following: ‘I buy more organic, as much as I can afford. And I think a lot about having meat-free days, and only some days with meat…. I eat greener [after the trial]’ (Tina, follow-up interview).

Other strategies in our data was to eat more fish or to eat smaller meals throughout the day. As such, the message about eating more protein, especially as part of breakfast and lunch, did not translate into radically new eating practices. Participants highlighted eating more varied foods as an important aspect of a healthy diet, a message that did not stem from the RCT but from decades of health campaigns. Another strategy was to increase the consumption of organic products, which was also not part of the trial. Moreover, the majority of participants already saw themselves as eating healthy, varied diets and did not change this during or after the trial. As such, protein was eclipsed by the pre-existing focus of participants on a healthy and varied diet.

In both groups, the protein powder was regarded as the most challenging and unpleasant aspect of the trial because of its taste and the way it made participants feel full. In a few cases, consuming the protein powder was even seen as being as unpleasant as the painful muscle biopsies. The increased protein intake had unintended impacts on other parts of the participants’ diets, as they reported that they had difficulties eating their usual breakfast following their protein intake. Participants raised concerns about gaining weight due to the protein powder, as they risked increasing their calorie intake as a result of the protein powder. This concern shows that to use the category of calories to measure the quality and content of food was seen as more relevant and important than other categories, such as protein. It also reveals a specific economisation of food intake, wherein the avoidance of a specific quality is considered more important than is the optimisation of another. A lower calorie intake was seen as more important than a greater protein intake.

A few of the participants did report an increase in their protein intake after the trial and as a result of the endorsement of the importance of protein. One participant, Karsten, changed to a more protein-rich diet after the trial but without being particularly systematic about it. He had never been particularly engaged in his diet, and as such, introducing more protein was quite straightforward. Another participant, Mogens, also became more focussed on protein during and after the trial. He now reads the protein content on all groceries he considers purchasing and calculates the amount of protein in his meals.

Despite the fact that a majority of the participants did not adopt more protein into their diet, as was presented to them in the trial, and mainly saw protein as part of and a confirmation of a healthy and varied diet, the cases of Karsten and Mogens nevertheless show that some specific strategies were developed to attach protein to the daily practices of participants. If knowledge is to be translated into practice, it requires particular ways of fitting the knowledge into existing practices; accordingly, it requires particular kinds of practices to which the knowledge can be attached. In line with the argument presented by Moreira (2004), the conditions for agency shift when the subject is attached and detached from the trial. While the research staff endeavoured to support participants during the trial, in the process of detachment the translation of protein changed.

The fact that Karsten found the introduction of more protein to be rather straightforward was the result of a previous lack of engagement in his diet, which we found was uncommon for the trial participants. For most, food was an integral and important part of their daily social life and health practices, and attaching new items or practices to their diet required great effort and had to be both meaningful and feasible. For Mogens, introducing protein caused some friction, as it required negotiations and quarrels with his wife, as she did most of the cooking of the protein-rich foods that he began to purchase. Also, his calculations of the protein content in the meals challenged her existing cooking practices, as protein was introduced as a new category she had to address, along with her many other considerations (e.g., health, taste, varied ingredients, vitamins, fat, sugar, carbohydrates, additives and sustainability).

The uptake and attachment of protein in Mogens’ eating practices became inadvertently attached to a wider issue regarding the division of labour between him and his wife. It was common that the male stated that they had minimal influence on the content of their meals, as these were cooked and controlled by their wives. While this division of labour within the household might be different for younger generations, many participants had more traditional gender roles. Mogens insisted on the importance of increasing the intake of protein in his daily diet, but he had to negotiate with and convince his wife that this requirement should also become attached to her cooking practices. However, Mogens is a deviant case in this regard, as most of the men who described this division of labour as a reason for not introducing more protein in their diet did not challenge the division of labour or negotiate the content of the diet with their wives.

Another reason to highlight this example is the fact that, from a trial perspective, Mogens was a participant and, thus, the intended recipient of the health knowledge and strategies; however, this very typical medical and health focus on the individual clashes with the fact that intervening in people’s eating and health practices is intervening in a socio-material and collective practice, involving and affecting a wider network of actors (Bønnelycke et al., 2019).

From our initial screening interviews, when asked about their motivations for participating in the trial, it became clear that the participants had not enroled in the trial due to the protein focus. On the contrary, they had enroled because of a wish to engage in more physical activity. They perceived good fitness and health as qualities obtained through exercise rather than through diet. Part of this bias towards the exercise aspect of the trial could be explained by the arrangement of the RCT. Located at the Institute for Sports Medicine, the physical environment of the trial was filled with visual and material queues related to exercise. Furthermore, the trial staff who the participants had contact with during the trial were mostly physiologists and physiotherapists and, as such, were particularly interested in and knowledgeable about exercise. The participants became attached to a specific exercise agenda.

While these institutional and epistemological attachments eased participants into focussing more on exercise, the wider networks and attachments of the participants also supported the focus on exercise. Meals and food are heavily populated social categories, attached to many parts of participants’ lives. As such, it was difficult for the protein aspect of the RCT to become part of the everyday lives of participants, as meals were already heavily invested in by the participants. In a sense, there was no empty space for protein to occupy. The message of optimising protein intake was difficult to translate into practice. On the contrary, and as we show in the following section, many participants did not have stable exercise routines prior to the RCT, as this was part of the inclusion criteria. There was an empty space that participants wanted to fill, and as such, there was a larger realm of possibility for the translation and dis/attachment of exercise than there was for that of protein.

Translating/transforming muscular exercise

While the LITW and HRTW groups underwent the same intervention in terms of protein, they were engaged in different exercise regimes (see above). Due to this, the findings regarding the ways in which the two groups attached the trial to their everyday lives also differed. However, in general, the participants transformed the focus on muscular training to a more general focus on physical activity after the intervention period. Whereas, in general, the participants did not seem to change their protein intake, participants in both groups increased their focus on muscular training after the intervention.

In the LITW group, only a few participants continued a muscular training regimen resembling the intervention. However, almost all participants started exercising more than they did prior to the intervention, and a wish to exercise more was also part of their reason for participating. The new kinds of exercise they engage in were diverse and included activities mostly focussed on cardiovascular exercise, such as table tennis, cycling or running, as well as on activities that also exercise the muscles, such as going to the gym or rowing. One strategy adopted by the participants who, following the trial, mostly engaged in cardiovascular exercise, was to use the elastics from the trial at home. Others merely started that although they had not started exercising their muscles more, they would like to and have become more aware of the importance of muscular training.

As described, the LITW group trained at home during the intervention and, thus, were expected to train alone, although this was not a requirement. While training alone could be a barrier to continued motivation to train, the way in which the training was made simple and accessible—using elastics in the home—could also ease the attachment to the existing practices of participants. Those who succeeded in continuing their muscular training after the intervention did so through attaching their muscular training routine to social networks and routines. These participants found training communities, and those who did not continue training were also, in general, those who did not look for ways in which to attach their training routines to their social relationships.

One participant, Elisabeth, enroled in the project through her husband, who wanted to participate. The couple did all things together, and it was therefore a given that they should participate in the trial together. However, Elisabeth’s husband had recently received a new hip, and the researchers were uncertain whether he could comply with the trial if he was picked for one of the training groups. When Elisabeth then ended up in the LITW group, he followed the same training programme as she did: ‘The only thing he did not get was documentation for his development’ (Elisabeth during semi-structured interview). After the trial, the couple had already arranged to continue their training regimen at the local fitness centre:

There was no transition period…. At the end of the trial, I had that muscle biopsy taken, which took a couple of days to get over…, but then we had made an agreement to go over there and become members…. I think we lacked a bit of the harder cardio training in the trial, like the cross trainer and the treadmill. (Elisabeth, during semi-structured interview)

Elisabeth and her husband inserted their participation and their continuation of the training into their existing routines, in which they did everything together. The trial became attached to their marriage, and when it became detached, the couple immediately looked for a new kind of attachment. However, this new attachment was transformed in its translation to the fitness centre. The couple had become aware of the importance of muscular training during the trial but had been concerned about the lack of cardiovascular exercise. As demonstrated in this case, reattachment entails transformation.

Another participant, Per, did not find that the rubber bands used in the LITW group facilitated training that was hard enough. However, he felt that exercise did make him stronger, so he wanted to continue. He requested a few extra rubber bands from the staff and was given them. As he ended the trial when summer started, and was busy in the garden all summer, at the time of the follow-up interview, he was starting his new exercise regimen. He had biked three to four times a week all summer and now wanted to start using the rubber bands one to two times daily. As he found the exercises too light, his idea was to take shorter breaks between sets and do the entire programme twice daily. As such, his way of translating his exercise to everyday life circumvented the advice from the trial staff, and he attached it to both his everyday rhythm—where it would fit in between other activities in the morning and the evening—and to his sense that he needed more strenuous exercise.

In the HRTW group, most participants continued to train their muscles more than they did prior to the RCT. However, compared to their training regimes during the intervention, all participants from this group trained less following the RCT than they did during the intervention. Participants stated that their exercise after the trial was ‘not as intense as it was during the trial’ (Dorthe, follow-up interview) and that the project left them without ‘a training programme so I could move on’ (Jens, follow-up interview).

Those HRTW participants who did not continue to train their muscles mostly ceased to do so due to injuries and disease, such as the case of Karina, who had to stop training due to pain caused by the training regimen, and of Hanne, who had to pause her training for half a year due to a severe eye condition. This pause was partly caused by the participant’s GP, who told to slow a bit down due to her age (74) and that no other patients her age engaged in muscular training. Participants were often shifting between periods of training and periods of injuries caused by overtraining and by certain social expectations towards age-appropriate behaviour—even among medical experts. The shifts in the conditions for agency occur not only as participants become attached or detached from the trial, but also as they encounter diverging clinical guidelines and expectations.

Participants from the HRTW described the social training session at the RCT location as the best part of participating in the study, as during this time, they ‘met some lovely people’ (Jørgen, follow-up interview); according to Ulrik, ‘the best thing, besides getting some muscles, have been all the social contacts I got in the group’ (Ulrik, follow-up interview). These positive side effect seemed to be a result of the structure that the HRTW routine provided to participants’ days and weeks—‘it is steady, three times a week” (Tina, follow-up interview)—and of participants’ experience of the fast progression and increase in muscle mass caused by the intense training regimen.

Participants described the positive benefits of the social community that they created around the HRTW training days. During the trial, a group of members established a Friday bar, where they would gather after training and drink Lumumba (a hot drink with cocoa and cognac), with their protein powder added. A group of four men were afraid that they could not continue their regimen after the trial, so as the trial ended, they asked one of the staff members to provide them with some guidance about how to continue. The staff member made a training regimen for them and suggested that they take an introductory lesson at the gym where he also worked. They did so and have trained at the gym since, but they adjusted their training so that it was twice rather than three times a week; they also continuously adjusted the exercises they did in their sessions. They became friends and held Christmas gatherings and other social events together. They used their training community to commit themselves to each other and to hold each other accountable for training when they needed to.

Participants explained that their retirement transition was made easier by the trial, as their participation became part of their self-perception and identity:

Through training, I have gained a new identity as a retiree, which my acquaintances are interested in. In work life, it is always work that my acquaintances ask about, but now it was suddenly this trial they asked about. That was great. (Jens, follow-up interview)

Amongst the former HRTW participants, the training regimen from the RCT facilitated attachments to their routinised everyday life, to new communities and social practices, and their embodied practices. As such, centre-based training became attached to everyday life precisely because of its invasiveness. While this might have been driven by a greater willingness to exercise muscles than to boost protein intake, in the accounts described, it was driven just as much by the lack of prior muscular training routines. While increased protein intake clashed, for most participants, with existing eating practices, we found that muscular training could often be attached to existing exercise practices.

Conclusion

In this paper, we followed two related lines of enquiry. First, we explored what happens if the current understanding of KT is extended from a mainly medical sphere—exemplified in the phrase ‘from bench to bedside’—out into the everyday life of the population. Second, we explored the following question: if translation, as proposed in STS, is to be understood as a sequence of mediation, transportation and change, then what happens to the medical knowledge when it meets the pre-existing health practices in people’s everyday lives?

As a result of our involvement in the CALM project and the unique opportunity to re-visit the participants months after the end of the intervention, we described the dynamics of KT processes by applying the terms of attachment/detachment and we described the development of different adaptation strategies rendering protein intake and muscular exercise into feasible and meaningful health practices.

We have shown that the RCT’s ability to translate knowledge and change existing practices relied a great deal on the ways the RCT became attached to—or remained detached from—those practices, and the extend to which the points of intervention (i.e., protein intake and muscular exercise) are already part of the fabric of everyday life. Even though a majority of the participants prior to the RCT had a focus on both healthy eating and exercise practices, the analysis shows a significant difference in the attitudes towards and appropriation of exercise and protein after the RCT. As already explained, one way of understanding this difference is due to the arrangement of the RCT combined with the reasons for the participants to engage in the trial, i.e. their motivation for doing more exercise. The differences in the ways knowledge of protein intake and muscular exercise were translated into practice thus relied on the level of change expected in the RCT and the supportive measures conducted in the RCT as a result of such expectations. While there were many measures installed in terms of changing exercise routines, and the entire RCT evolved around staff and facilities focussed on muscular exercise, the eating patterns of participants (including their protein intake habits) were largely left untouched. The participants were only expected to add protein powder to their eating patterns during the trial, and as such, little was done to change existing practices. This resulted in a very different translation of knowledge at the time of follow-up than that which was observed in relation to muscular exercise. If the hope of the study was to change eating patterns, this needed to be approached in a different way than merely adding powder during a 12-month intervention. Rather, the same level of attention needed to be directed towards the ways in which protein intake was attached to the everyday lives of the participants. With the protein powder, protein was easily detached from the existing practices of the participants after the intervention, while in terms of muscular exercise, the participants had exerted great effort during the trial to attach this to their daily practices.

A few points can be highlighted from our analysis. First, our analysis exposes the precariousness and constant work required in maintaining the content of ‘medical knowledge’ in a complex social order. We recommend that the way knowledge is translated, transformed and negotiated be considered when defining the stakeholders of medical knowledge. While current models of KT—such as the Knowledge-to-Action (KTA) Framework (Graham et al., 2006) and the WHO’s Knowledge Translation Framework (WHO, 2012)—point to the time from knowledge to action or to empirical evidence as key problem points within KT, we suggest that neglecting to consider the configurations of everyday practices of laypeople leaves medical knowledge with little chance to actually become attached or relevant to the lives in which it is supposed to intervene. Alternatively, it may become attached to such lives in uncontrollable and arbitrary ways.

Second, understanding the translation work that occurs in everyday life emphasises that KT is an open-ended process in which the medical object of knowledge is contested and renegotiated and needs attachments to other objects of knowledge in order to stay relevant. We suggest that future studies of KT endeavour to understand and delineate such objects of knowledge and their attachments.

Third, from an everyday life perspective, medical knowledge and rationale is but one rationale making up the fabric of people’s health practices; other rationales, such as time, feasibility, logistics and social relations are just as relevant for understanding how and why people pursue healthy living or comply with a medical regimen. Developing a detailed understanding of the ways in which medical knowledge forms part of the fabric of people’s health practices should be given more attention if KT is to move beyond the bedside.

Thus, the findings of the present paper demonstrate that the situated translation of knowledge does not stop at the bedside or in the clinic. The embodied health practices and adaptation strategies that people have developed prior to the clinical encounter also contribute to the possibilities and abilities of KT. While we do not deem KT an impossible mission, we do call for a much more nuanced and far-stretching understanding of the practices by which medical knowledge becomes attached to everyday life.

Data availability

The dataset generated and analysed during the current study is not publicly available due to the sensitive nature of the content and the use/consent agreed with informants. Selected anonymized extracts and summaries are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and signing of a MOU to ensure the ethical use of data.

References

Bechshøft RL, Reitelseder S, Højfeldt G, Castro-Mejia JL, Khakimov B, Ahmad HFB, Kjær M, Engelsen SB, Johansen SMB, Rasmussen MA, Lassen AJ, Jensen T, Beyer N, Serena A, Perez-Cueto FJA, Nielsen DS, Jespersen AP, Holm L (2016) Counteracting Age-related Loss of Skeletal Muscle Mass: a clinical and ethnological trial on the role of protein supplementation and training load (CALM Intervention Study): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 17:397

Brown SD (2002) Michel Serres: science, translation and the logic of the parasite. Theory Cult Soc 19(3):1–27

Bønnelycke J, Sandholdt CT, Jespersen AP (2019) Household collectives: resituating health promotion and physical activity. Sociol Health Illn 41(3):533–548

Cohn S (2014) From health behaviours to health practices: an introduction. Sociol Health Illn 36(2):157–162

Creswell JW, Poth CN (2017) Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. Sage publications

Engebretsen E, Sandset TJ, Ødemark J (2017) Expanding the knowledge translation metaphor. Health Res Policy Sys 15:19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-017-0184-x

Gomart E, Hennion A (1999) A sociology of attachment: music amateurs, drug users. Sociol Rev 47:220–247

Graham ID, Logan JO, Harrison MB, Straus SE, Tetroe J, Caswell W, Robinson N (2006) Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Profession 26:13–24

Greenhalgh T, Wieringa S (2011) Is it time to drop the ‘knowledge translation’ metaphor? A critical literature review. J R Soc Med 104:501–509

Haynes RB, Taylor DW, Sackett DL (eds) (1979) Compliance in Health Care. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore

Jespersen AP, Bønnelycke J, Eriksen HH (2014) Careful science? Bodywork and care practices in randomised clinical trials. Sociol Health Illn 36(5):655–669

Kontopodis M, Niewöhner J, Beck S (2011) Investigating emerging biomedical practices: zones of awkward engagement on different scales. Science Technol Human Val 36(5):599–615

Latour B (1987) Science in action: how to follow scientists and engineers through society. Open University Press, Milton Keynes

Lassen AJ, Mertz K, Holm L, Jespersen AP (2020) Retirement rhythms: retirees’ management of time and activities in Denmark. Societies 10(3):68. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc10030068

Law J (2003) Traduction/Trahison: notes on ANT, published by the Centre for Science Studies, Lancaster University, Lancaster LA1 4YN, at https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/fass/resources/sociology-online-papers/papers/law-traduction-trahison.pdf

Mattingly C, Grøn L, Meinert L (2011) Chronic homework in emerging borderlands of healthcare. Cult Med Psychiatry 35(3):347–327

Mol A (2008) The logic of care: health and the problem of patient choice. Routledge

Mol A, Moser I, Pols J (2010) Care: putting practice into theory. In: Mol A, Moser I, Pols J (eds.) Care in practice. On tinkering in clinics, homes and farms, MatteRealities/VerKörperungen. Perspectives from Empirical Sciences Studies. transcript Verlag, Bielefeld, pp. 7–27

Moreira T (2004) Self, agency and the surgical collective: detachment. Sociol Health Illn 26(1):32–49

Niewöhner J, Döring M, Kontopodis M et al. (2011) Cardiovascular disease and obesity prevention in Germany: an investigation into a heterogeneous engineering project. Science Technol Human Val 36(5):723–751

Otto M (2019) Aldringsforsøg. Kliniske interventioner, aldrende kroppe og hverdagslivets domesticeringer. Ph.D Dissertation, University of Copenhagen

Straus SE, Tetroe J, Graham I (2010) Defining knowledge translation. CMAJ 181:165–168

Timmermans S, Berg M (2003) The gold standard, the challenge of evidence-based medicine and standardization in health care. Temple University Press, Philadelphia

Timmermans S, Epstein S (2010) A world of standards but not a standard world: toward a sociology of standards and standardization. Ann Rev Sociol 36:69–89

WHO (2003) Adherence to long term therapies. Evidence for action. World Health Organization, Geneva

WHO (2012) Knowledge Translation Framework for Ageing and Health. World Health Organization, Geneva

Winther J (2017) Making It Work. Trial Work between Scientific Elegance and Everyday Life Workability. Ph.D Dissertation, University of Copenhagen

Winther J (2018) Routines on trial. the roadwork of expanding the lab into everyday life in an exercise trial in Denmark. Ethnol Scand 48:98–122

Acknowledgements

The study is funded by the University of Copenhagen Excellence Programme for Interdisciplinary Research 2016 (CALM project; www.calm.ku.dk) and hosted by Copenhagen Centre for Health Research in the Humanities, Department of Biomedical Sciences and Department of Food Science at University of Copenhagen, and Institute of Sports Medicine at Bispebjerg Hospital. The study was carried out with support of prof. Lars Holm, prof. Dennis Sandris Nielsen and researchers at the CALM project. Special thanks are also extended to all the participants in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jespersen, A.P., Lassen, A.J. & Schjeldal, T.W. Translation in the making: how older people engaged in a randomised controlled trial on lifestyle changes apply medical knowledge in their everyday lives. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8, 154 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00835-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00835-5