Abstract

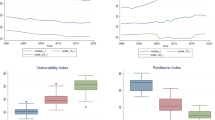

Climate change poses an existential threat to the global economy. While there is a growing body of literature on the economic consequences of climate change, research on the link between climate change and sovereign default risk is nonexistent. We aim to fill this gap in the literature by estimating the impact of climate change vulnerability and resilience on the probability of sovereign debt default. Using a sample of 116 countries over the period 1995–2017, we find that climate change vulnerability and resilience have significant effects on the probability of sovereign debt default, especially among low-income countries. That is, countries with greater vulnerability to climate change face a higher likelihood of debt default compared to more climate resilient countries. These findings remain robust to a battery of sensitivity checks, including alternative measures of sovereign debt default, model specifications, and estimation methodologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Climate refers to a distribution of weather outcomes for a given location, and climate change describes environmental shifts in the distribution of weather outcomes toward extremes.

In a recent article, for example, Cochrane (2021) presented a skeptic view of climate-related risks to financial stability.

In this paper, we focus on countries’ exposure to physical risks that correspond to the potential economic and financial losses caused by climate change. However, it should be noted that transition risks related to the process of adjusting toward a low-carbon economy, such as stranded asset exposures in the financial system, can also amount to a sizable burden.

There is also literature on the recovery rate after a debt restructuring process. See e.g. Edwards (2015) for a study on the Argentine case.

Tol (2018) provides a recent overview of this expanding literature.

The list of countries is presented in Appendix Table 4.

Since 1960, 147 governments have defaulted on their obligations—well over half the current universe of 214 sovereigns. Defaults had the biggest global impact in the 1980s, peaking at US$450 billion, or 6.1% of world public debt, by 1990. The scale of defaults has fallen substantially since then. Over the past decade, it has ranged between 0.3 and 0.9% of world public debt, and in 2019 it was an estimated 0.4%.

The analysis of the determinants of sovereign defaults depends on the very definition of debt defaults. It is common in many empirical studies to use debt crises synonymously with debt defaults for simplicity. However, this can be problematic especially in the post-1990s period, as pointed out by Pescatori and Sy (2007). Ams and others (2018) suggest several other ways to define sovereign debt default, including the database used in this paper.

The ND-GAIN database, covering 184 countries over the period 1995–2017, is available at https://gain.nd.edu/.

The ND-GAIN database refers to this series as “readiness” for climate change, which we use as a measure of resilience against climate change. In this context, it should also be noted that the ND-GAIN indices do not reflect fiscal insurance schemes for natural disasters that may occur due to climate change.

King and Zeng (2001) describe rare events as “dozens to thousands of times fewer ones […] than zeroes.”

References

Acevedo S, Mrkaic M, Novta N, Pugacheva E, Topalova P (2018) The effects of weather shocks on economic activity: what are the channels of impact? In: IMF Working Paper No. 18/144. International Monetary Fund, Washington

Aguiar M, Gopinath G (2006) Defaultable Debt, Interest Rates and the Current Account. J Int Econ 69(1):64–83

Arellano C (2008) Default risk and income fluctuations in emerging economies. Am Econ Rev 98:690–712

Bansal R, Kiku D, Ochoa M (2016) Price of Long-Run Temperature Shifts in Capital Markets. In: NBER Working Paper No. 22529. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge

Beers D, de Leon-Manlagnit P (2019) The BoC-BoE sovereign default database: What’s new in 2019? In: Bank of Canada Staff Working Paper No. 2019–39. Bank of Canada, Ottawa

Bernstein A, Gustafson M, Lewis R (2019) Disaster on the horizon: the Price effect of sea level rise. J Financ Econ 134:253–272

Burke M, Tanutama V (2019) Climatic Constraints on Aggregate Economic Output. In: NBER Working Paper No. 25779. National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge

Burke M, Hsiang S, Miguel E (2015) Global nonlinear effect of temperature on economic production. Nature 527:235–239

Catão L, Kapur S (2004) Missing Link: Volatility and the Debt Intolerance Paradox. In: IMF Working Paper No. 04/51. International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC

Catão L, Sutton B (2002) Sovereign Defaults: The Role of Volatility. In: IMF Working Paper No. 02/149. International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC

Cevik S, Jalles J (2020) This Changes Everything: Climate Shocks and Sovereign Bonds. In: IMF Working Paper No. 20/79. International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC

Cline W (1992) The economics of global warming. New York University Press, New York

Cochrane J (2021) Don’t let financial regulators dream up climate solutions. City Journal 24:2021 https://www.city-journal.org/dont-let-financial-regulators-dream-up-climate-solutions

Cohen D, Valadier C (2015) Endogenous Debt Crises. J Int Money Financ 51:337–369

Cuaresma J (2010) Natural Disasters and Human Capital Accumulation. World Bank Econ Rev 24:280–302

Dell M, Jones B, Olken B (2012) Temperature shocks and economic growth: evidence from the last half century. Am Econ J Macroecon 4:66–95

Edwards S (2015) Sovereign Default debt restructuring and recovery rates: was the Argentinean “haircut” excessive? Open Econ Rev 26:839–867

Gallup J, Sachs J, Mellinger A (1999) Geography and economic development. Int Reg Sci Rev 22:179–232

Gao S, Shen J (2007) Asymptotic properties of a double penalized maximum likelihood estimator in logistic regression. Statistics and Probability Letters 77:925–930

Gassebner M, Keck A, Teh R (2010) Shaken, Not Stirred: The Impact of Disasters on International Trade. Rev Int Econ 18:351–368

Hansen S (1989) Debt for nature swaps — overview and discussion of key issues. Ecol Econ 1:77–93

Hilscher J, Nosbusch Y (2010) Determinants of sovereign risk: macroeconomic fundamentals and the pricing of sovereign debt. Review of Finance 14:235–262

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2007) Fourth assessment report, intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press, New York

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2014) Climate change in 2014: mitigation of climate change. Working group III contribution to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press, New York

International Monetary Fund (2020) Physical Risk and Equity Prices. In: Global Financial Stability Report, Chapter 5. International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC

Kahn M, Mohaddes K, Ng R, Pesaran M, Raissi M, Yang J-C (2019) Long-Term Macroeconomic Effects of Climate Change: A Cross-Country Analysis. In: IMF Working Paper No. 19/215. International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC

Kaminsky G, Vega-García P (2016) Systemic and idiosyncratic sovereign debt crises. J Eur Econ Assoc 14:80–114

King G (2001) Proper nouns and methodological propriety: pooling dyads in international relations data. Int Organ 55:497–507

King G, Zeng L (1999a) Logistic Regression in Rare Events Data. In: Department of Government Working Paper. Harvard University, Cambridge

King G, Zeng L (1999b) Estimating Absolute, Relative, and Attributable Risks in Case-Control Studies. In: Department of Government Working Paper. Harvard University, Cambridge

King G, Zeng L (2001) Explaining rare events in international relations. Int Organ 55:693–715

Kohlscheen E (2007) Why are there serial defaulters? Evidence from Constitutions. J Law Econ 50:713–730

Manasse P, Roubini N (2009) Rule of thumb for sovereign debt crises. J Int Econ 78:192–205

Nordhaus W (1991) To slow or not to slow: the economics of the greenhouse effect. Econ J 101:920–937

Nordhaus W (1992) An optimal transition path for controlling greenhouse gases. Science 258:1315–1319

Nordhaus W (2006) Geography and macroeconomics: new data and new findings. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:3510–3517

Noy I (2009) The macroeconomic consequences of disasters. J Dev Econ 88:221–231

Painter M (2020) An inconvenient cost: the effects of climate change on municipal bonds. J Financ Econ 135:468–482

Panizza U, Sturzenegger F, Zettelmeyer J (2009) The economics and law of sovereign debt and default. J Econ Lit 47:651–698

Pescatori A, Sy A (2007) Are debt crises adequately defined? IMF Staff Pap 54:306–337

Raddatz C (2009) The wrath of God: Macroeconomic Costs of Natural Disasters. In: World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 5039. World Bank, Washington, DC

Rasmussen T (2004) Macroeconomic Implications of Natural Disasters in the Caribbean. In: IMF Working Paper No. 04/224. International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC

Reinhart C, Rogoff K (2009) This time is different: eight centuries of financial folly. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Reinhart C, Trebesch C (2016) Sovereign debt relief and its aftermath. J Eur Econ Assoc 14:215–251

Reinhart C, Rogoff K, Savastano M (2003) Debt Intolerance. Brook Pap Econ Act 34:1–74

Skidmore M, Toya H (2002) Do natural disasters promote long-run growth? Econ Inq 40:664–687

Stern N (2007) The economics of climate change: the Stern review. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Sturzenegger F, Zettelmeyer J (2006) Debt defaults and lessons from a decade of crises. MIT Press, Cambridge

Tol R (2018) The economic impacts of climate change. Rev Environ Econ Policy 12:4–25

Vaugirard V (2005) Crony capitalism and sovereign default. Open Econ Rev 16:77–99

Wooldridge J (2002) Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT Press

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the editor, George Tavlas, and two anonymous referee for their insightful comments that led to marked improvements in the paper. An earlier version of this article benefited from comments and suggestions by Cristian Alonso, Pierre Guerin, Mick Keen, Yuko Kinoshita, Roberto Piazza, and Aleksandra Zdzienicka. This work was supported by the FCT (Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia) [grant numbers UID/ECO/00436/2019]. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the IMF, its Executive Board, or its management (Cevik) and the University of Lisbon’s School of Economics and Management (Jalles).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cevik, S., Jalles, J.T. An Apocalypse Foretold: Climate Shocks and Sovereign Defaults. Open Econ Rev 33, 89–108 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-021-09624-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-021-09624-8