Abstract

To control agronomic N losses and reduce environmental pollution, biological nitrification inhibition (BNI) is a promising strategy. BNI is an ecological phenomenon by which certain plants release bioactive compounds that can suppress nitrifying soil microbes. Herein, we report on two hydrophobic BNI compounds released from maize root exudation (1 and 2), together with two BNI compounds inside maize roots (3 and 4). On the basis of a bioassay-guided fractionation method using a recombinant nitrifying bacterium Nitrosomonas europaea, 2,7-dimethoxy-1,4-naphthoquinone (1, ED50 = 2 μM) was identified for the first time from dichloromethane (DCM) wash concentrate of maize root surface and named “zeanone.” The benzoxazinoid 2-hydroxy-4,7-dimethoxy-2H-1,4-benzoxazin-3(4H)-one (HDMBOA, 2, ED50 = 13 μM) was isolated from DCM extract of maize roots, and two analogs of compound 2, 2-hydroxy-7-methoxy-2H-1,4-benzoxazin-3(4H)-one (HMBOA, 3, ED50 = 91 μM) and HDMBOA-β-glucoside (4, ED50 = 94 μM), were isolated from methanol extract of maize roots. Their chemical structures (1–4) were determined by extensive spectroscopic methods. The contributions of these four isolated BNI compounds (1–4) to the hydrophobic BNI activity in maize roots were 19%, 20%, 2%, and 4%, respectively. A possible biosynthetic pathway for zeanone (1) is proposed. These results provide insights into the strength of hydrophobic BNI activity released from maize root systems, the chemical identities of the isolated BNIs, and their relative contribution to the BNI activity from maize root systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nitrogen (N), a macronutrient required for crop plant growth, is an essential component of fertilizer for sustaining food production in modern productive agriculture (White and Brown 2010). Urea, anhydrous NH3, (NH4)2SO4, and NH4NO3 are commonly used as ammonium-based fertilizer in global agricultural fields (Halvorson et al. 2014). Currently, total global consumption of N fertilizer accounts for 50% among the world’s three highest-production cereals, rice (16%), wheat (18%), and maize (16%) (Coskun et al. 2017; Ladha et al. 2016). Despite their benefits, approximately half of applied N fertilizers are leached from agricultural fields, which results in economic loss because of excess fertilizer application and low N use efficiency of crop plants (Halvorson et al. 2014; Lassaletta et al. 2014; Mueller et al. 2014). These major N losses from fertilized soil are caused by two microbial biochemical reactions: nitrification and denitrification (Bock et al. 1995; Zumft 1997). Nitrification is a series of oxidation reactions from NH4+ through hydroxylamine (NH2OH) and nitrite (NO2−) to nitrate (NO3−), where the first key step is catalyzed by the ammonia monooxygenase enzyme from ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (e.g., Nitrosomonas europaea and Nitrobacter sp.) and ammonia-oxidizing archaea (e.g., Nitrososphaera viennensis and Nitrosopumilus maritimus) (Konneke et al. 2005; Kowalchuk and Stephen 2001; Morimoto et al. 2011; Tourna et al. 2011; Treusch et al. 2005). Because NH4+ (electropositive) can be attracted to the negatively charged surface of soil particles, the NH4+ form of N can be retained in soil (Hommes et al. 1998; Meier and Kahr 1999). Upon nitrification of NH4+, highly mobile NO3− (electronegative) is produced and leached through the soil particles (Oelmann et al. 2007). The leaching of mobile NO3− out of agricultural fields can cause serious environmental pollution affecting groundwater and human health (Rivett et al. 2008; Ward et al. 2018). Meanwhile, NO3− undergoes denitrification to form gaseous N2O that is released from soil into the air as a greenhouse gas that is 310 times more potent than CO2 (Lubbers et al. 2013; Ravishankara et al. 2009). Thus, excess nitrification can directly or indirectly give rise to major N loss involving not only environmental problems but also economic damage. In other words, controlling nitrification to keep NH4+ as an available N source can achieve effective N fertilization for crop plants along with the reduction of environmental pollution.

Biological nitrification inhibition (BNI) shows great potential as a component of sustainable agriculture because it uses the natural nitrification inhibitory potential of field crops (Coskun et al. 2017; Subbarao et al. 2013b; Subbarao and Searchinger 2021; Wendeborn 2020). BNI is a specific ecological phenomenon that occurs in the plant rhizosphere, where secondary metabolites emitted from plant roots inhibit nitrification of nitrifying microbes. Secondary metabolites, also known as plant specialized metabolites, have diverse biological activities that influence the growth, survival, germination, and reproduction of other organisms in nature, such as allelopathy, antibiotics, and innate immunity (Bednarek 2012; Cheng and Cheng 2015; Morrissey and Osbourn 1999; Sirikantaramas et al. 2007).

Since Munro (1966) first reported the nitrification inhibition of tropical grass Hyparrhenia filipendula, many scientists (Pancholy, Schmidt, Mccarty, and others) have investigated the effects of phytochemicals on nitrification activity in soil over more than half a century (Bremner and Mccarty 1988; Mccarty et al. 1991; Rice and Pancholy 1973). In 2009, BNI was first reported for signalgrass (Brachiaria humidicola) with inhibitory effects as well as the discovery of a bioactive diterpenoid, brachialactone (Subbarao et al. 2009; Fig. S1). Furthermore, several BNI compounds have been identified from plant roots (Fig. S1): sorgoleone, sakuranetin, and methyl 3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)propionate from sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) (Subbarao et al. 2013a; Zakir et al. 2008) and 1,9-decanediol from rice (Oryza sativa) (Sun et al. 2016).

We have previously categorized the BNI compounds of root exudate into “hydrophobic” and “hydrophilic” fractions based on their interactions with water (Subbarao et al. 2013a, b). In the rhizosphere, hydrophilic BNI compounds, having a strong affinity for water, can be easily diffused with water. In contrast, hydrophobic compounds will be retained around the root surface because of their water‐insolubility. Accordingly, it is important to select suitable extraction solvents depending on water-solubility of BNI compounds. Dichloromethane (DCM) has been used as an extraction solvent to obtain hydrophobic BNI compounds from root surface of sorghum, termed the “DCM-wash” extract (Subbarao et al. 2013a, b). In particular, the hydrophobic BNI compound sorgoleone was identified in root-DCM-wash, which was prepared by washing roots with acidified DCM for 30 s (Subbarao et al. 2013a, b).

In addition to root exudates, plants generally produce and accumulate abundant metabolites inside roots. We assumed that the BNI compounds inside roots act as precursors for the BNIs released from root surface; however, there have been no reports on BNI compounds inside maize roots. Then, we expected that identification of BNI compounds from not only root surface but also root inside might lead to the understanding of total BNI activities in maize roots.

Despite being the most widely produced crop in the world, not much is known about BNI function in maize, with almost no published knowledge on chemical identities of BNI compounds produced from maize root systems. Indeed, our preliminary investigations detected significant levels of BNI activity released from maize root systems—both hydrophobic and hydrophilic BNI activities were detected in sufficient strength from maize root systems.

In this paper, we describe the isolation and identification of hydrophobic BNI compounds from the surface of maize roots which were recovered from the DCM-wash, together with BNI compounds inside maize roots using root tissue after the DCM-wash procedure and recovered by two different extraction solvents: DCM extract and methanol (MeOH) extract. Furthermore, we propose a BNI mechanism in maize based on our findings.

Material and methods

Planting and collection of maize seeds

Sweetcorn (Zea mays L. cv Honey bantam) seeds purchased from Sakata Seed Corp. (Kanagawa, Japan) were used. Ninety seeds were soaked in a plastic bottle containing 200 mL diluted water with bubble aeration under dark conditions at 25 °C for 24 h. The seeds were rinsed twice with fresh distilled water, then wrapped in a moistened paper towel and kept in a growth chamber in the dark at 25 °C for 24 h. To grow roots, germinated seeds were held between a rectangular filter paper with a supporting hard-plastic plate, then stood up in a growth box containing 1.0 L 200 μM CaSO4 aqueous solution; the bottom part of each filter paper was soaked in the solution to continuously supply solution to seeds. The incubator boxes were set at 29 °C/25 °C (max/min) with the photoperiod of 13 h/11 h (day/night) and supplied daily with the 200 μM CaSO4 solution to keep filter papers moist. The grown seedlings were collected at 12 days after planting (Fig. S2). A total of 8579 plants were raised in six rounds of seed germination (collections No. 1–No. 6).

DCM washing and extraction of maize roots

To collect root surface metabolites, shoot and seed were cut off from the root section of maize (Fig. S2c). The fresh maize roots (approximately 106 g dried weight equivalent) were soaked and agitated in 1.0 L DCM [containing 1.0% acetic acid (AcOH) as a solubilizing agent] for 1 min. The wash solution was then filtered and evaporated in vacuo at 40 °C, and the concentrate was named the “DCM-wash.” The residue of root tissue was soaked with another 1.0 L DCM (1.0% AcOH) for 48 h, filtered, and concentrated to obtain the “DCM extract.” After removal of DCM in a fume hood, the remaining tissue was lyophilized, pulverized, extracted with 500 mL MeOH for 48 h, and evaporated to give the “MeOH extract.” From 8579 maize roots, three concentrates of DCM-wash (220 mg), DCM extract (395 mg), and MeOH extract (10 g) were obtained.

Chemicals

Thin layer chromatography (TLC) and preparative TLC (PTLC) were carried out on 0.25-mm silica gel 60 F254 plates (Merck Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). Extraction solvents including DCM, MeOH, ethyl acetate (EtOAc), n-hexane, and AcOH were reagent grade. The standard 6-methoxy-3H-1,3-benzoxazol-2-one (6-MBOA; MBOA) was purchased from FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corp. (Osaka, Japan). The β-glucosidase, α-glucosidase (from rice), and β-amylase were purchased from Toyobo Co., Ltd. (Osaka, Japan), Sigma-Aldrich Corp. (St. Louis, MO, USA), and FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corp. (Osaka, Japan), respectively. If not specifically mentioned, water used was purified by a Milli-Q system (Merck Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). Compounds and fractions isolated from maize roots were stored at 4 °C under dark conditions.

Instrumentation

One-dimensional (1D) and two-dimensional (2D) nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) experiments were recorded on a Bruker AVANCE III HD 800 MHz spectrometer equipped with a cryoprobe unit, or a Bruker AVANCE III HD 500 MHz spectrometer. Chemical shifts δ (ppm) were referenced to the residual solvent signals of 1H- or 13C-NMR: acetone-d6 (δH 2.05 ppm; δC 29.9 ppm), CD3OD (δH 3.31 ppm; δC 49.0 ppm), CDCl3 (δH 7.24 ppm; δC 77.0 ppm), and pyridine-d5 (δH7.22, 7.58, 8.74; δC 123.9, 135.9, 150.3). High-resolution electrospray ionization Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectra (HR-ESI FT-ICR MS) were obtained on a Thermo Fisher Orbitrap Velos Pro. Liquid chromatography–ESI mass spectrometry (LC–ESI–MS) analyses were carried out on Shimadzu LCMS-2020 (Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan) using a TSKgel Super-ODS column (4.6 mm I.D. × 50 mm, 2.3 μm; Tosoh Corp., Tokyo, Japan) with a linear gradient of the binary solvent system consisting of H2O (0.1% formic acid) and acetonitrile at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. The analytical and preparative (prep.) reverse phase (RP-) HPLC were performed on a Shimadzu prominence LC-20AT instrument (Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan) with Shimadzu SPD-M20A photodiode array (PDA) detector (Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan), accompanied by a TSKgel Super-ODS column (4.6 mm I.D. × 50 mm, 2.3 μm) or a Cosmosil πNAP column (4.6 mm I.D. × 250 mm, 5.0 μm; Nacalai Tesque Inc., Kyoto, Japan). Solid-phase extraction was performed on a Sep-Pak Plus C18 solid phase cartridge (360 mg sorbent per cartridge; Waters, Milford, MA, USA).

Separation and purification of BNI compounds

A DCM-wash concentrate (220 mg) was developed on a Sep-Pak Plus C18 solid phase cartridge eluting with H2O, 50% MeOH/H2O, 70% MeOH/H2O, MeOH, EtOH, and 50% DCM/MeOH, successively, where each eluent was collected as a fraction. After two high BNI active 50% and 70% MeOH aqueous fractions were combined (162 mg dry weight), the resulting concentrate was further purified by RP-HPLC on a TSKgel Super-ODS column using a linear gradient [1% acetonitrile/H2O (0.1% formic acid) (start) to 30% acetonitrile/H2O (0.1% formic acid) (13 min) to 100% acetonitrile (18 min), 1.5 mL min−1] to give five fractions (DCMw-1–DCMw-5). Fraction DCMw-3 (27.5 mg, tR 7.6–10.5 min) was separated by TSKgel Super-ODS column [1% acetonitrile/H2O (0.1% formic acid) (start) to 30% acetonitrile/H2O (0.1% formic acid) (13 min), 1.5 mL min−1], resulting in the isolation of compound 1 (0.1 mg, tR 9.8–10.1 min). A part of fraction DCMw-2 (15 mg/120 mg, tR 5.6–7.5 min) was purified by PTLC using DCM/MeOH = 10:1 as solvent system, giving compound 5 (7.0 mg).

A part of the DCM extract (30 mg/395 mg) was separated by a TSKgel Super-ODS column [1% acetonitrile/H2O (0.1% formic acid) (start) to 30% acetonitrile/H2O (0.1% formic acid) (13 min), 1.0 mL min−1], giving a target fraction containing only compound 2. The target solution (tR 7.8–8.5 min) was directly extracted thrice by EtOAc, followed by concentration of the EtOAc layer under vacuum at 25 °C to yield compound 2 (10 mg). The DCM extract (395 mg) was separated by TSKgel Super-ODS column [1% acetonitrile/H2O (0.1% formic acid) (start) to 30% acetonitrile/H2O (0.1% formic acid) (13 min), 1.5 mL min−1], yielding compound 1 (0.05 mg, tR 9.8–10.1 min).

A part of the MeOH extract (2.3 g/10 g) was partitioned between EtOAc and 30% MeOH aqueous solution. The EtOAc layer was concentrated under reduced pressure to a brown syrup (415 mg) and further partitioned between n-hexane and 10% MeOH aqueous solution. The 10% MeOH fraction (Fr. 10 M) was separated by RP-HPLC on a TSKgel Super-ODS column [1% acetonitrile/H2O (0.1% formic acid) (start) to 30% acetonitrile/H2O (0.1% formic acid) (13 min) to 100% acetonitrile (18 min), 1.5 mL min−1], giving five fractions 10 M-1–10 M-5. Fraction 10 M-2 (30 mg, tR 5–10 min) was separated using RP-HPLC on a πNAP column [20% acetonitrile/H2O (0.1% formic acid), 1.0 mL min−1] to furnish five fractions 10 M-2–1–10 M-2–5. Fraction 10 M-2–4 (5.8 mg, tR 8–10 min) was divided into two fractions by a πNAP column [10% acetonitrile/H2O (0.1% formic acid), 1.0 mL min−1]. Compounds 3 (3.0 mg) and 4 (20 mg) were isolated as single components of fractions 10 M-2–4-1 (tR 8.2–9 min) and 10 M-2–4-2 (tR 9.1–9.8 min), respectively.

HPLC analysis for degradation of compound 2 in DCM-wash

The dried DCM-wash sample (1.5 mg) was dissolved in 100 μL MeOH. An aliquot of this solution (1 μL) was added to 49 μL MeOH. Five microliters of sample solution was analyzed by Shimadzu LCMS-2020 on a TSKgel Super-ODS [1% acetonitrile/H2O (0.1% formic acid) (start) to 100% acetonitrile/H2O (0.1% formic acid) (13 min), 0.4 mL min−1, ultraviolet (UV) absorption at 210 nm]. The degradation was monitored at 0 and 24 h after adding MeOH.

Preparation of calibration curves

To quantitate the amount of compound 2 present in samples, a standard curve for the conversion of the chromatogram peak area into the amount of sample was prepared. The purified compound 2 was dissolved in acetonitrile (1% acetone) at different concentrations (0–100 ppm). These samples were applied to the Shimadzu LCMS-2020 on a TSKgel Super-ODS column [1% acetonitrile/H2O (0.1% formic acid) (start) to 30% acetonitrile/H2O (0.1% formic acid) (13 min) to 100% acetonitrile (18 min), 0.4 mL min−1]. The peak area of 2 was determined from the resulting chromatogram monitoring at 210 nm. The obtained peak areas were plotted against the concentrations of compound 2 for all samples (Fig. S3). Similarly, compounds 1, 3, and 4 were dissolved in MeOH and quantified by HPLC analyses (Fig. S3).

HPLC analyses of extracts of maize

Each DCM-wash dried sample (one batch) was dissolved in 2.0 mL acetone. An aliquot of the solution (1 μL) was added to 49 μL acetonitrile. Then, 5 μL of each sample was analyzed by Shimadzu LCMS-2020 on a TSKgel Super-ODS [1% acetonitrile (start) to 100% acetonitrile (13 min), 0.4 mL min−1, UV 210 nm]. Similarly, DCM extract (39.5 mg/395 mg) was prepared, and its sample solution (5 μL) was analyzed. The 10% MeOH extract (15 mg/200 mg) was dissolved in 1.0 mL MeOH, and an aliquot of 1 μL was added to 49 μL MeOH. The following HPLC analysis of sample (5 μL) was carried out in the same manner as that for DCM-wash and DCM extract.

Nitrification inhibition bioassay

A detailed description of the method is described in previous work (Iizumi et al. 1998; Subbarao et al. 2006). In brief, the recombinant strain of N. europaea was used, which expresses luciferases of luxA and luxB genes from the marine bacterium Vibrio harveyi and produces a specific luminescence pattern with two distinct peaks during a measurement period (30 s). The key functional relationship between bioluminescence emission and NO2− production is linear when using the synthetic nitrification inhibitor, allylthiourea (AT), as a standard. The inhibition caused by AT of 0.22 μM, ED80 in bioluminescence and NO2− production, is defined as 1 allylthiourea unit (ATU). The inhibitory activities of organism extracts and compounds are expressed in ATU based on dose–response standard curve of AT.

Results

Isolation of BNI compound from DCM-wash

To collect hydrophobic compounds from the root surface of maize, “DCM-wash” was prepared based on a previous study of sorghum (Subbarao et al. 2013a, b). The total BNI activity of DCM-wash (220 mg) of maize roots was estimated at 7700 ATU based on the bioassay. To isolate the BNI compounds while reducing loss of sample, we applied a specific activity strategy (biological activity per unit weight of the compounds or fractions) to a bioassay-guided fractionation method. This method enabled us to focus on the target fraction by analysis of the bioassay result of each fraction.

Initially, we separated the DCM-wash concentrate (220 mg, 7700 ATU) by Sep-Pak C18 cartridge to obtain the most specific active BNI in 50% and 70% MeOH aqueous fractions (162 mg, 5000 ATU). Other fractions (H2O, MeOH, EtOH, and 50% DCM/MeOH) exhibited relatively much weaker inhibition (2800 ATU by four fractions). The 50–70% MeOH aqueous fraction was then separated by prep. HPLC into five fractions DCMw-1–DCMw-5 (Fig. 1).

Through purification of the most specific active fraction DCMw-3 by prep. HPLC, the target compound 1 (0.1 mg, 2233 ATU) was isolated (27.5 mg, 2300 ATU; Fig. 2).

Structural elucidation of compound 1

The molecular formula of compound 1 was elucidated as C12H10O4 with eight degrees of unsaturation by HR-ESI FT-ICR MS at m/z 219.0658 [M + H]+ (calculated 219.0652 for C12H11O4; Fig. S4a). The UV absorptions at 266 (π–π* transition), 293 (π–π* transition) nm, and the long tail band at 358 nm reaching far into the visible band for the pale yellow color of compound 1 suggested an oxygenated 1,4-naphthoquinone system, such as 2-methoxy-1,4-naphthoquinone (Little et al. 1948; Fig. S4b). The 1H-NMR spectrum of compound 1 showed six signals assignable to a dimethoxylated 1,4-naphthoquinone, two methoxy singlets at δH 3.92 and 3.87, a quinone proton at δH 6.08 (s), three aromatic protons at δH 8.00 (d, J = 8.6 Hz), 7.54 (d, J = 2.6 Hz), and 7.19 (dd, J = 8.6 and 2.6 Hz), to which their corresponding six 13C signals (δC 128.5, 120.8, 110.0, 109.8, 56.3, and 55.9) were attributed based on Heteronuclear Single Quantum Correlation (HSQC) correlations (Fig. 3, Fig. S5a, and Table 1). The remaining six carbon signals in the 13C NMR spectrum of compound 1 were assigned as two carbonyl carbons on 1,4-benzoquinone (δC 184.2 and 180.3), two methoxy groups attached carbons (δC 163.7 and 160.2), and two ring-condensation positional carbons (δC 132.9 and 125.4), respectively. The planar structure of compound 1 was elucidated as 2,7-dimethoxy-1,4-naphthoquinone by Heteronuclear Multiple Bond Correlation (HMBC) correlations of 2-OCH3/C-2; 7-OCH3/C-7; H-3/C-2, C-4, C-4a; H-5/C-4, C-7; H-6/C-4a; and H-8/C-1, C-8a (Fig. S5b and Fig. S5c). The 1H-NMR spectral data of compound 1 were in accordance with those of reported data for a synthetic compound; however, 13C-NMR spectral data and 2D-NMR data were not reported for that compound (Table 1; Guay and Brassard 1986). In the present study, we completely assigned the spectral data of compound 1 based on 2D-NMR correlations (HSQC and HMBC). Because this was the first isolation of naturally occurring 2,7-dimethoxy-1,4-naphthoquinone, we named this compound “zeanone” (Fig. 4a).

The 1H-NMR (800 MHz, CDCl3) (a) and 13C-NMR (201 MHz, CDCl3) (b) spectra of compound 1. Chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (ppm) relative to the solvent residual peak of CDCl3 (δH 7.24 ppm, δC 77.0 ppm). a In 1H-NMR, a total of six signals of 1 were observed. A broad singlet peak at 1.56 ppm was caused by residual H2O. Enlarged view of split peaks of 1 was shown. b In 13C-NMR, a total of 12 signals of 1 were observed

Chemical structure (a) and dose–response curve (b) of zeanone (1). a Common name was listed in square brackets. Physiochemical data of compound 1: pale-yellow powder, Rf = 0.33 (silica, hexane/EtOAc = 2:1), HR-ESI-FT-ICR MS (positive) m/z 219.0658 [M + H]+. b BNI activity of compound 1: ED50 = 2 μM, ED80 = 8 μM

Zeanone (1) exhibited BNI activity with ED50 value of 2 μM and ED80 value of 8 μM (Fig. 4b), which was higher than those of earlier reported compounds, methyl linoleate (ED80 = 27 μM), sorgoleone (ED80 = 13 μM), and brachialactone (ED80 = 10.6 μM) (Subbarao et al., 2008, 2009, 2013a).

Isolation of BNI compound from DCM extract

Specific activity-based fractionation led to the isolation of zeanone (1) (0.1 mg, 2233 ATU) from DCM-wash (220 mg), but at low yield. Considering the remaining nearly 2700 ATU in the residue fractions DCMw-1, DCMw-2, DCMw-4, and DCMw-5, we inferred that high-content BNI compounds might exist within those fractions. With this hypothesis, we re-analyzed the HPLC data for DCM-wash (a stock sample before separation) and DCM extract. As a result, the dominant peak 2 was observed in both extracts (Fig. S6a and Fig. S6b). Furthermore, peak 2 had been fractionated in the fraction DCMw-2 (120 mg, 2300 ATU) from DCM-wash (Fig. 1); therefore, candidate compound 2 was expected to be a major BNI compound.

We then attempted to isolate compound 2 from fraction DCMw-2 (Fig. 1). However, the dominant peak 2 was undetected in DCMw-2, while a new peak 5 was strongly observed. Compound 5, suspected to be a degradation product of compound 2, was tentatively isolated by PTLC, and then established as a known benzoxazole MBOA (6-methoxy-2(3H)-benzoxazolone) by comparing the TLC and LC/MS results with those of commercially available MBOA (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corp., Osaka, Japan) (Fig. S7 and Fig. S8). A previous report described that labile benzoxazinoids chemically decompose to give MBOA (5) and formic acid in vitro (Atkinson et al. 1991; Kosemura et al. 1994). Additionally, the UV absorption of compound 2 at 262 and 290 nm showed the characteristic pattern for benzoxazinoids (Fig. S9a). These data strongly suggested that compound 2 might be a degradable benzoxazinoid.

Next, we developed the isolation method for unstable compound 2 using a part of the DCM extract, which showed a similar HPLC chromatogram to that of DCM-wash before purification (Fig. S6). A part of the DCM extract (30 mg/395 mg) was fractionated using RP-HPLC to obtain a fraction containing pure compound 2. Then, the aqueous solution of 2 was directly extracted by EtOAc followed immediately by concentration of the organic layer to provide purified compound 2 (10 mg). Comprehensive analyses of NMR and MS spectra determined the structure of compound 2 as a known benzoxazinoid, 2-hydroxy-4,7-dimethoxy-2H-1,4-benzoxazin-3(4H)-one (HDMBOA) (Fig. 5a, Fig. S9b, and Table S1) (Maresh et al. 2006).

HDMBOA (2) was assayed to determine the BNI activity, which resulted in ED50 = 13 μM and ED80 = 70 μM (Fig. 5b). The natural benzoxazinoids, which are mainly distributed in Poaceae families including maize and wheat, showed a wide range of biological activities (allelopathy, regulating immune immunity, antimicrobial activity, etc.) (Ahmad et al. 2011; de Bruijn et al. 2018; Neal et al. 2012; Niemeyer 2009; Rice et al. 2012; Zhou et al. 2018). The biosynthetic pathway of benzoxazinoids has been extensively established and shares the same precursor indole-3-glycerol phosphate with primary metabolism in the biosynthesis of an essential amino acid tryptophan (Fig. S10) (Frey et al. 2009; Jonczyk et al. 2008; von Rad et al. 2001; Wright et al. 1992).

Following that, we confirmed the degradation of HDMBOA (2) into MBOA (5) in MeOH by HPLC analysis (Fig. S11). This result was consistent with a previous observation, in which compound 5 was the only aromatic compound detected in a MeOH solution of compound 2 after 12-h incubation (Escobar et al. 1997). Therefore, compound 2 in DCM-wash was confirmed to undergo degradation into compound 5 during the separation procedures by a Sep-Pak C18 column and prep. HPLC, followed by concentration.

The total weight of HDMBOA (2) accounted for 50 wt% of the original DCM-wash sample (110 mg, 2541 ATU) by quantification experiments (Fig. S6c). This result confirmed that compound 2 was a major constituent of maize roots in accordance with a previous report (Zhang et al. 2000).

Isolation of BNI compounds from MeOH extract

Next, we confirmed BNI activity of the MeOH extract and attempted to isolate responsible compounds based on the bioassay-guided fractionation method. The MeOH extract was partitioned between EtOAc and 30% MeOH aqueous solution by liquid–liquid distribution. The BNI active compounds were then concentrated in the EtOAc layer, so the EtOAc portion was further partitioned between n-hexane and 10% MeOH aqueous solution. Because the BNI activity was condensed into the 10% MeOH fraction (200 mg), this fraction was separated by prep. HPLC to yield two BNI compounds 3 (3.0 mg) and 4 (20 mg). Their structures were established as known benzoxazinoids, 2-hydroxy-7-methoxy-2H-1,4-benzoxazin-3(4H)-one (HMBOA, 3) (Fig. 6a, Fig. S12, and Table S2) and 2-hydroxy-4,7-dimethoxy-2H-1,4-benzoxazin-3(4H)-one-β-glucoside (HDMBOA-β-glucoside, 4) (Fig. 6c, Fig. S13, and Table S3), respectively. Both compounds were structural analogs of HDMBOA (2), namely, compound 3 carries an amine instead of the N-OMe group of 2 and compound 4 is the glucoside form of 2.

Compounds 3 and 4 showed BNI activities of ED50 = 91 μM, ED80 > 100 μM and ED50 = 94 μM, ED80 > 200 μM, respectively (Fig. 6b and d).

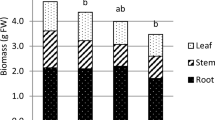

Quantification of BNI compounds in DCM-wash, DCM extract, and MeOH extract

We quantified four BNI compounds 1–4 in three extracts: DCM-wash, DCM extract, and MeOH extract (Fig. 7). The most specific BNI active zeanone (1) isolated from DCM-wash (220 mg) was also detected in DCM extract (395 mg) by RP-HPLC analysis, which was quantified as 0.05 mg (Fig. 7a, b, and d). We eventually isolated 0.05 mg of zeanone (1) from DCM extract by prep. HPLC. The amount of HDMBOA (2) in DCM-wash (220 mg) and DCM extract (395 mg) was quantified as 110 mg (50 wt%) and 132 mg (33 wt%), respectively. HMBOA (3) and HDMBOA-β-glucoside (4) identified in MeOH extract (10 g) were undetected in DCM-wash and DCM extract (Fig. 7c and d).

RP-HPLC profiles for three extracts prepared from maize roots (a–c) and quantity of BNI compounds in the three extracts (d). Each HPLC chromatogram (a–c) was monitored at 210 nm. a HPLC chromatogram of DCM-wash, an enlarged view (tR 7.5–10 min), and UV spectra of peaks 1 and 2 were shown. b HPLC chromatogram of DCM extract, an enlarged view (tR 7.5–10 min), and UV spectra of peaks 1 and 2 were shown. c HPLC chromatogram of MeOH extract, an enlarged view (tR 7.5–10 min), and UV spectra of peaks 3 and 4 were shown. d The amount of each compound was quantified based on the peak area in HPLC chromatogram monitored at 210 nm, or weighed after isolation

Discussion

Relative contribution of isolated BNI compounds to the BNI activities

The DCM-wash solution extracted hydrophobic compounds localized on the surface of maize roots. We also observed that maize accumulated abundant metabolites inside the root, and then recovered them in DCM extract and MeOH extract. Following these results, we calculated the BNI contribution of each compound in three extracts based on specific BNI activities and the quantity of the four identified compounds: zeanone (1), HDMBOA (2), HMBOA (3), and HDMBOA-β-glucoside (4).

Compounds 1 and 2 were identified from DCM-wash. Their contributions to the BNI activity in DCM-wash (7700 ATU) were 33% and 29%, respectively (Fig. 8a). Compounds 1 (21% contribution) and 2 (22% contribution) were also identified from DCM extract (47,400 ATU) (Fig. 8b). Compounds 3 (13% contribution) and 4 (26% contribution) were identified as BNI compounds only from the MeOH extract (Fig. 8c).

BNI activity breakdown for three extracts (a–c) and maize roots (d). a DCM-wash was composed of root surface hydrophobic compounds as depicted in right panel. Zeanone (1) and HDMBOA (2) were identified as major BNI compounds in DCM-wash. b DCM extract contained DCM-soluble compounds inside the root. Two BNI compounds 1 and 2 were identified in DCM extract. c MeOH extract contained MeOH-soluble compounds inside the root. Two BNI compounds 3 and 4 were identified in MeOH extract. d Maize roots contained a combined total of BNI activities of the three extracts (a–c) as depicted in the right panel

In order to reveal the contribution of identified BNI compounds in maize roots (approximately 106 g dried weight equivalent), we combined the total BNI activities for three extracts (Fig. 8d). Because compounds 1 (12,187 ATU) and 2 (12,969 ATU) accounted for 39% of total BNI activity in maize roots (65,100 ATU), we assigned both compounds 1 and 2 as major BNI components in maize roots (Fig. 8d). The contribution of compounds 3 (2%) and 4 (4%) to total BNI activity in maize roots was 6%; consequently, we revealed that 45% of total BNI activity in maize roots was due to compounds 1–4 (Fig. 8d).

Given that the total BNI activity in maize roots can be divided into the root surface part (12% BNI activity, DCM-wash) and the internal root part (88% BNI activity, DCM extract and MeOH extract), and hydrophobic compounds released from the root surface can be maintained in the rhizosphere because of their lack of affinity with water, we predict that zeanone (1) and HDMBOA (2) on the root surface act as the major hydrophobic BNI compounds in soil. In addition to this, BNI activities inside root might not be effective in soil unless they are released through decomposition or leached out from roots. In contrast, we predict that some of the BNI inactive metabolites inside the root might behave as precursors of BNI compounds until transportation to the root surface, regardless of whether they are hydrophobic or hydrophilic BNI compounds. Further research on the hydrophilic BNI compounds of maize roots will enhance our knowledge into the BNI function in maize as well as the chemical structure–BNI activity relationship.

Zeanone (1)—a possible biosynthetic pathway

Zeanone (1) as a naturally occurring new compound is categorized as a 1,4-naphthoquinone. Natural 1,4-naphthoquinones have been found in numerous plants and serve as multifunctional bioactive compounds mainly because of their redox-active bicyclic structure (Widhalm and Rhodes 2016). Among well-known bioactive 1,4-napthoquinones, 2-methoxy-1,4-naphthoquinone (MNQ) is a highly fungistatic substance from garden balsam (Impatiens balsamina) and 5-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone (juglone) is an allelochemical of black walnut (Juglans nigra) (Little et al. 1948; Soderquist 1973). In contrast, the biosynthetic pathway of 1,4-naphthoquinones is still not completely understood (Foong et al. 2020; McCoy et al. 2018; Widhalm and Rhodes 2016). Thus, the biosynthetic pathway of compound 1 was proposed based on the structural similarity between compound 1 and MNQ (Fig. 9). Recent reports showed that the shikimate pathway and 1,4-dihydroxy-2-naphthoic acid (DHNA) pathway contributed to the biosynthesis of MNQ (Foong et al. 2020; Widhalm and Rhodes 2016). The naphthoquinone scaffold of DHNA is formed through a Dieckmann condensation of o-succinyl benzoic acid (OSB). An oxidation reaction for substitution of the C-2 carboxyl group of DHNA with a hydroxy group results in 2-hydroxy-naphthoquinone, a precursor of MNQ. After the production of MNQ through O-methylation at C-2 of 2-hydroxy-naphthoquinone, an additional hydroxylation and O-methylation at C-7 could generate compound 1.

Is HDMBOA-β-glucoside (4) a possible precursor for BNI active HDMBOA (2)?

Considering our identification of another major BNI compound HDMBOA (2) and weak BNI compound HDMBOA-β-glucoside (4) inside the root, it should be noted that endogenous BNI benzoxazinoid-glucoside can be hydrolyzed to form the more active BNI compound agricone regardless of auto-conversion or enzymatic reaction in nature. Specifically, once roots or root residues are wounded or cut open by external factors, the internal root compound 4 will be leached out (Fig. 8c). Then, compound 4 will be rapidly hydrolyzed to the more active BNI compound 2 in the rhizosphere by soil microbes or maize roots themselves. In fact, our enzymatic experiments showed that compound 2 was generated from compound 4, which was catalyzed by β-glucosidase and β-amylase, respectively (Fig. S14). Following Hiradate’s total activity concept, when 100 μM solution of compound 4 (ED50 = 94 μM) was completely hydrolyzed to 100 μM compound 2 (ED50 = 13 μM) and glucose (no activity), the total activity of 2 [100 μM/13 μM = 7.7 (no unit)] was approximately 7.7-fold higher than 4 [100 μM/94 μM = 1.1 (no unit)] (Hiradate 2006). Hence, the precursor compound 4 inside maize roots (or root residues) might play a role as an effective driving force of BNI compound 2. At the same time, we need to consider that the biological and/or chemical fate of BNI compounds might affect the total BNI activities produced from maize root systems.

Proposed BNI mechanism in maize

From the results obtained in this study, we propose the following BNI mechanism in maize (Fig. 10). Initially, two major BNI compounds zeanone (1) and HDMBOA (2) are biosynthesized and accumulated on the surface of maize roots (Fig. 8a, Fig. 9, and Fig. S10). Because the surface of developing roots is first in contact with soil particles, BNI will inevitably occur in the rhizosphere. Because of the retention of N as NH4+ in soil, primary metabolism in maize is stably activated, involving growth and development. Then, maize produces abundant bioactive secondary metabolites made from primary metabolites as substrate. Subsequently, usage of these secondary metabolites will allow maize to exhibit biological phenomena, including phytoalexins, antibiotics, and BNI. Ecologically, these phytochemical responses might provide an advantage for maize survival and improve the growth environment.

Proposed BNI mechanism in maize. Zeanone (1) and HDMBOA (2) are produced from the root surface, exhibiting BNI activity in the rhizosphere. When BNI compounds inside the root are leached out, they might show BNI activity. The precursor HDMBOA-β-glucoside (4) might act as an effective driving force for production of BNI compound 2

Natural products with BNI activity released from maize roots can reduce soil-NO3− formation and have implications for NO3− pollution of ground waters and N2O emissions from maize farming. Hence, the efficient application of BNI by maize and N fertilizer could help control agronomic N losses and reduce environmental pollution. Deeper understanding of BNI function and the chemical identification of BNI compounds produced by crops is expected to contribute to the construction of novel sustainable agricultural systems.

Conclusion

We discovered zeanone (1, ED50 = 2 μM), a new naphthoquinone in nature, in maize root exudates as one of the major BNI components. Furthermore, we identified another major BNI compound HDMBOA (2, ED50 = 13 μM) from both the root surface and inside the root. From inside the root, we also obtained two BNI compounds, HMBOA (3, ED50 = 91 μM) and HDMBOA-β-glucoside (4, ED50 = 94 μM); the latter compound could act as a precursor for the more active BNI compound 2. We revealed that compounds 1–4 contributed 45% of the total BNI activity in maize roots. Our research led to the proposal of a possible biosynthetic pathway of compound 1 and the BNI mechanism in maize. The study presented here highlights the novel bioactivity of naphthoquinones and benzoxazinoids. Identified BNI compounds from maize roots can lead to further characterization of genetic stocks for using the BNI function in maize production systems. Our findings on BNI in this study open the gates for developing modern productive agriculture systems with BNI.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ahmad S, Veyrat N, Gordon-Weeks R, Zhang Y, Martin J, Smart L, Glauser G, Erb M, Flors V, Frey M, Ton J (2011) Benzoxazinoid metabolites regulate innate immunity against aphids and fungi in maize. Plant Physiol 157:317–327. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.111.180224

Atkinson J, Morand P, Arnason JT, Niemeyer HM, Bravo HR (1991) Analogs of the cyclic hydroxamic acid 2,4-dihydroxy-7-methoxy-2H-1,4-benzoxazin-3-one (DIMBOA): decomposition to benzoxazolinones and reaction with β-mercaptoethanol. J Org Chem 56:1788–1800. https://doi.org/10.1021/jo00005a025

Bednarek P (2012) Chemical warfare or modulators of defence responses – the function of secondary metabolites in plant immunity. Curr Opin Plant Biol 15:407–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbi.2012.03.002

Bock E, Schmidt I, Stuven R, Zart D (1995) Nitrogen loss caused by denitrifying Nitrosomonas cells using ammonium or hydrogen as electron-donors and nitrite as electron-acceptor. Arch Microbiol 163:16–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/Bf00262198

Bremner JM, Mccarty GW (1988) Effects of terpenoids on nitrification in soil. Soil Sci Am J 52:1630–1633. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1988.03615995005200060023x

Cheng F, Cheng Z (2015) Research progress on the use of plant allelopathy in agriculture and the physiological and ecological mechanisms of allelopathy. Front Plant Sci 6:1020. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2015.01020

Coskun D, Britto DT, Shi W, Kronzucker HJ (2017) Nitrogen transformations in modern agriculture and the role of biological nitrification inhibition. Nat Plants 3:17074. https://doi.org/10.1038/nplants.2017.74

de Bruijn WJC, Gruppen H, Vincken JP (2018) Structure and biosynthesis of benzoxazinoids: plant defence metabolites with potential as antimicrobial scaffolds. Phytochemistry 155:233–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2018.07.005

Escobar CA, Kluge M, Sicker D (1997) Syntheses of 2-hydroxy-4,7-dimethoxy-2H-1,4-benzoxazin-3(4H)-one: a precursor of a bioactive electrophile from Gramineae. Tetrahedron Lett 38:1017–1020. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0040-4039(96)02492-6

Foong LC, Chai JY, Ho ASH, Yeo BPH, Lim YM, Tam SM (2020) Comparative transcriptome analysis to identify candidate genes involved in 2-methoxy-1,4-naphthoquinone (MNQ) biosynthesis in Impatiens balsamina L. Sci Rep 10:16123. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72997-2

Frey M, Schullehner K, Dick R, Fiesselmann A, Gierl A (2009) Benzoxazinoid biosynthesis, a model for evolution of secondary metabolic pathways in plants. Phytochemistry 70:1645–1651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.05.012

Guay V, Brassard P (1986) Synthesis of (+/–)-7- and 8-hydroxydunnione. J Nat Prod 49:122–125. https://doi.org/10.1021/np50043a015

Halvorson AD, Snyder CS, Blaylock AD, Del Grosso SJ (2014) Enhanced-efficiency nitrogen fertilizers: potential role in nitrous oxide emission mitigation. Agron J 106:715–722. https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2013.0081

Hiradate S (2006) Isolation strategies for finding bioactive compound: specific activity vs. total activity. Nat Prod Pest Manag 927:113–126

Hommes NG, Russell SA, Bottomley PJ, Arp DJ (1998) Effects of soil on ammonia, ethylene, chloroethane, and 1,1,1-trichloroethane oxidation by Nitrosomonas europaea. Appl Environ Microbiol 64:1372–1378. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.64.4.1372-1378.1998

Iizumi T, Mizumoto M, Nakamura K (1998) A bioluminescence assay using Nitrosomonas europaea for rapid and sensitive detection of nitrification inhibitors. Appl Environ Microbiol 64:3656–3662. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.64.10.3656-3662.1998

Jonczyk R, Schmidt H, Osterrieder A, Fiesselmann A, Schullehner K, Haslbeck M, Sicker D, Hofmann D, Yalpani N, Simmons C, Frey M, Gierl A (2008) Elucidation of the final reactions of DIMBOA-glucoside biosynthesis in maize: characterization of Bx6 and Bx7. Plant Physiol 146:1053–1063. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.107.111237

Konneke M, Bernhard AE, de la Torre JR, Walker CB, Waterbury JB, Stahl DA (2005) Isolation of an autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing marine archaeon. Nature 437:543–546. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03911

Kosemura S, Yamamura S, Anai T, Hasegawa K (1994) Chemical studies on 2,4-dihydroxy-7-methoxy-2H-1,4-benzoxazin-3(4H)-one in connection with 6-methoxy-2-benzoxazolinone, an auxin-inhibiting substance of Zea mays L. Tetrahedron Lett 35:8221–8224. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-4039(94)88287-8

Kowalchuk GA, Stephen JR (2001) Ammonia-oxidizing bacteria: a model for molecular microbial ecology. Annu Rev Microbiol 55:485–529. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.485

Ladha JK, Tirol-Padre A, Reddy CK, Cassman KG, Powlson DS, van Kessel C, Richter D de B, Chakraborty D, Pathak H (2016) Global nitrogen budgets in cereals: A 50-year assessment for maize, rice and wheat production systems. Sci Rep 6:19355. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep19355

Lassaletta L, Billen G, Grizzetti B, Anglade J, Garnier J (2014) 50 year trends in nitrogen use efficiency of world cropping systems: the relationship between yield and nitrogen input to cropland. Environ Res Lett 9:105011. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/9/10/105011

Little JE, Sproston TJ, Foote MW (1948) Isolation and antifungal action of naturally occurring 2-methoxy-1,4-naphthoquinone. J Biol Chem 174:335–342

Lubbers IM, van Groenigen KJ, Fonte SJ, Six J, Brussaard L, van Groenigen JW (2013) Greenhouse-gas emissions from soils increased by earthworms. Nat Clim Change 3:187–194. https://doi.org/10.1038/Nclimate1692

Maresh J, Zhang J, Lynn DG (2006) The innate immunity of maize and the dynamic chemical strategies regulating two-component signal transduction in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. ACS Chem Biol 1:165–175. https://doi.org/10.1021/cb600051w

Mccarty GW, Bremner JM, Schmidt EL (1991) Effects of phenolic acids on ammonia oxidation by terrestrial autotrophic nitrifying microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 85:345–450. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6968.1991.tb04761.x

McCoy RM, Utturkar SM, Crook JW, Thimmapuram J, Widhalm JR (2018) The origin and biosynthesis of the naphthalenoid moiety of juglone in black walnut. Hortic Res 5:67. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41438-018-0067-5

Meier LP, Kahr G (1999) Determination of the cation exchange capacity (CEC) of clay minerals using the complexes of copper(II) ion with triethylenetetramine and tetraethylenepentamine. Clay Clay Miner 47:386–388. https://doi.org/10.1346/Ccmn.1999.0470315

Morimoto S, Hayatsu M, Takada-Hoshino Y, Nagaoka K, Yamazaki M, Karasawa T, Takenaka M, Akiyama H (2011) Quantitative analyses of ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA) and ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) in fields with different soil types. Microbes Environ 26:248–253. https://doi.org/10.1264/jsme2.me11127

Morrissey JP, Osbourn AE (1999) Fungal resistance to plant antibiotics as a mechanism of pathogenesis. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 63:708–724. https://doi.org/10.1128/Mmbr.63.3.708-724.1999

Mueller ND, West PC, Gerber JS, MacDonald GK, Polasky S, Foley JA (2014) A tradeoff frontier for global nitrogen use and cereal production. Environ Res Lett 9:054002. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/9/5/054002

Munro PE (1966) Inhibition of nitrite-oxidizers by roots of grass. J Appl Ecol 3:227–229. https://doi.org/10.2307/2401247

Neal AL, Ahmad S, Gordon-Weeks R, Ton J (2012) Benzoxazinoids in root exudates of maize attract Pseudomonas putida to the rhizosphere. PLoS One 7:e35498. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0035498

Niemeyer HM (2009) Hydroxamic acids derived from 2-hydroxy-2H-1,4-benzoxazin-3(4H)-one: key defense chemicals of cereals. J Agric Food Chem 57:1677–1696. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf8034034

Oelmann Y, Kreutziger Y, Bol R, Wilcke W (2007) Nitrate leaching in soil: tracing the NO3– sources with the help of stable N and O isotopes. Soil Biol Biochem 39:3024–3033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2007.05.036

Ravishankara AR, Daniel JS, Portmann RW (2009) Nitrous oxide (N2O): the dominant ozone-depleting substance emitted in the 21st century. Science 326:123–125. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1176985

Rice EL, Pancholy SK (1973) Inhibition of nitrification by climax ecosystems. II. Additional evidence and possible role of tannins. Am J Bot 60:691–702. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1537-2197.1973.tb05975.x

Rice CP, Cai G, Teasdale JR (2012) Concentrations and allelopathic effects of benzoxazinoid compounds in soil treated with rye (Secale cereale) cover crop. J Agric Food Chem 60:4471–4479. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf300431r

Rivett MO, Buss SR, Morgan P, Smith JW, Bemment CD (2008) Nitrate attenuation in groundwater: a review of biogeochemical controlling processes. Water Res 42:4215–4232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2008.07.020

Sirikantaramas S, Yamazaki M, Saito K (2007) Mechanisms of resistance to self-produced toxic secondary metabolites in plants. Phytochem Rev 7:467–477. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11101-007-9080-2

Soderquist CJ (1973) Juglone and allelopathy. J Chem Educ 50:782–783. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed050p782

Subbarao GV, Searchinger TD (2021) A “more ammonium solution” that mitigates nitrogen pollution, boosts crop yields. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118:e2107576118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2107576118

Subbarao GV, Ishikawa T, Ito O, Nakahara K, Wang HY, Berry WL (2006) A bioluminescence assay to detect nitrification inhibitors released from plant roots: a case study with Brachiaria humidicola. Plant Soil 288:101–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-006-9094-3

Subbarao GV, Nakahara K, Ishikawa T, Yoshihashi T, Ito O, Ono H, Ohnishi-Kameyama M, Yoshida M, Kawano N, Berry WL (2008) Free fatty acids from the pasture grass Brachiaria humidicola and one of their methyl esters as inhibitors of nitrification. Plant Soil 313:89–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-008-9682-5

Subbarao GV, Nakahara K, Hurtado MP, Ono H, Moreta DE, Salcedo AF, Yoshihashi T, Ishikawa T, Ishitani M, Ohnishi-Kameyama M, Yoshida M, Rondon M, Rao IM, Lascano CE, Berry WL, Ito O (2009) Evidence for biological nitrification inhibition in Brachiaria pastures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:17302–17307. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0903694106

Subbarao GV, Nakahara K, Ishikawa T, Ono H, Yoshida M, Yoshihashi T, Zhu YY, Zakir HAKM, Deshpande SP, Hash CT, Sahrawat KL (2013a) Biological nitrification inhibition (BNI) activity in sorghum and its characterization. Plant Soil 366:243–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-012-1419-9

Subbarao GV, Sahrawat KL, Nakahara K, Rao IM, Ishitani M, Hash CT, Kishii M, Bonnett DG, Berry WL, Lata JC (2013b) A paradigm shift towards low-nitrifying production systems: the role of biological nitrification inhibition (BNI). Ann Bot 112:297–316. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcs230

Sun L, Lu Y, Yu F, Kronzucker HJ, Shi W (2016) Biological nitrification inhibition by rice root exudates and its relationship with nitrogen-use efficiency. New Phytol 212:646–656. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.14057

Tourna M, Stieglmeier M, Spang A, Könneke M, Schintlmeister A, Urich T, Engel M, Schloter M, Wagner M, Richter A (2011) Nitrososphaera viennensis, an ammonia oxidizing archaeon from soil. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:8420–8425. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1013488108

Treusch AH, Leininger S, Kletzin A, Schuster SC, Klenk HP, Schleper C (2005) Novel genes for nitrite reductase and Amo-related proteins indicate a role of uncultivated mesophilic crenarchaeota in nitrogen cycling. Environ Microbiol 7:1985–1995. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00906.x

von Rad U, Huttl R, Lottspeich F, Gierl A, Frey M (2001) Two glucosyltransferases are involved in detoxification of benzoxazinoids in maize. Plant J 28:633–642. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01161.x

Ward MH, Jones RR, Brender JD, de Kok TM, Weyer PJ, Nolan BT Villanueva CM, van Breda SG (2018)Drinking water nitrate and human health: an updated review.Int J Environ Res Public Health 15https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15071557

Wendeborn S (2020) The chemistry, biology, and modulation of ammonium nitrification in soil. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 59:2182–2202. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201903014

White PJ, Brown PH (2010) Plant nutrition for sustainable development and global health. Ann Bot 105:1073–1080. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcq085

Widhalm JR, Rhodes D (2016) Biosynthesis and molecular actions of specialized 1,4-naphthoquinone natural products produced by horticultural plants. Hortic Res 3:16046. https://doi.org/10.1038/hortres.2016.46

Wright AD, Moehlenkamp CA, Perrot GH, Neuffer MG, Cone KC (1992) The maize auxotrophic mutant orange pericarp is defective in duplicate genes for tryptophan synthase beta. Plant Cell 4:711–719. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.4.6.711

Zakir HA, Subbarao GV, Pearse SJ, Gopalakrishnan S, Ito O, Ishikawa T, Kawano N, Nakahara K, Yoshihashi T, Ono H, Yoshida M (2008) Detection, isolation and characterization of a root-exuded compound, methyl 3-(4-hydroxyphenyl) propionate, responsible for biological nitrification inhibition by sorghum (Sorghum bicolor). New Phytol 180:442–451. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02576.x

Zhang J, Boone L, Kocz R, Zhang C, Binns AN, Lynn DG (2000) At the maize/Agrobacterium interface: natural factors limiting host transformation. Chem Biol 7:611–621. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00007-7

Zhou S, Richter A, Jander G (2018) Beyond defense: multiple functions of benzoxazinoids in maize metabolism. Plant Cell Physiol 59:1528–1537. https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcy064

Zumft WG (1997) Cell biology and molecular basis of denitrification. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 61:533–616. https://doi.org/10.1128/.61.4.533-616.1997

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Ikuko Maeda at the NARO for the NMR measurement and also Ms. Tomoko Sato at the NARO for the HR-MS measurements. We are grateful to Ms. Yukiko Ishikawa for the maintenance of Nitrosomonas cultures used for bioassay, and Ms. Hiroko Aoki, Ms. Yoko Koizumi, Ms. Masami Aoyama, Ms. Sanae Suzuki, Mr. Makoto Yamamoto, Dr. Gao Xiang, and Mr. Raphael Obias Mubanga for raising maize plants for the BNI activity isolation work at JIRCAS. We thank Catherine Dandie, PhD, from Edanz Group (https://en-author-services.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Funding

This paper reports results obtained within a research project entitled: “Development of ecologically sustainable agricultural systems through practical use of the BNI function,” supported by JIRCAS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.O., G.V.S., and T.Y. designed the experiments. J.O. carried out planting, extraction, analysis, and isolation compounds from maize roots. G.V.S. performed biological studies. J.O., H.O., and T.Y. identified chemical structures of compounds. All authors have contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Otaka, J., Subbarao, G.V., Ono, H. et al. Biological nitrification inhibition in maize—isolation and identification of hydrophobic inhibitors from root exudates. Biol Fertil Soils 58, 251–264 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-021-01577-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-021-01577-x