Abstract

In most post-socialist cities modernist mass housing comprises a remarkable share of urban housing with a substantial population living there. Therefore, socialist large housing estates (LHEs) have been a fruitful source for research to gather systematic knowledge concerning segregation and housing preferences. Less is known, however, of contemporary LHE-related urban policies and planning interventions. This study asks how in the post-privatisation era, when former governance structures had disappeared, did new urban governance arrangements related to LHEs begin to emerge. We take a closer look at two LHE areas in post-Soviet cities: Annelinn (Tartu, Estonia) and Žirmunai Triangle (Vilnius, Lithuania). The research is based on expert interviews and document analysis exploring the formation of governance networks in both cities since the 2000s and the rationale behind recent planning initiatives. A common new spatial expectation for housing estates’ residents and contemporary urban planners seems to be a perceptible differentiation of the public, semi-public and private spaces, instead of the former modernist concept of free planning and large open areas between buildings. As the heightened planning interest came at a time when European cohesion measures supported urban budgets, it also has led to tangible investments, and builds the consensus that the public sector should return to post-privatised LHEs. We argue that public space has been a great medium for modern governance networks and bringing LHEs back to the urban agenda in post-socialist cities and that the lessons learned in the post-socialist context provide an insight for the wider global marketization debate.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In the early 1990s most of Europe’s formerly socialist countries made a strategic choice to privatise almost entirely the existing urban housing stock (Broulíková and Montag 2020, 65–66). After decades of socialist supply-based public provision of standard urban housing, individual responsibility for a personal housing unit was now considered to be the backbone of the emerging market economy and the only realistic solution when it came to coping with dramatically reduced public funding. Interestingly, this coincided with a period in which public housing provision drastically contracted elsewhere in European welfare states. There is a great deal of research today that sharply criticizes the trends of marketization and commodification of housing in European welfare states (Jacobs 2019; Byrne 2020). At the same time, Central and Eastern European housing markets with their two-decade long experience of almost fully privatised housing, i.e. post-privatized context, have not been sufficiently involved in these discussions on new market-based urban governance models.

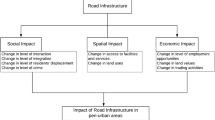

In this article we study the governance networks in post-privatised, post-socialist large housing estates (LHEs). We define urban governance as a process driven by the relationships and interactions between different public, private and civil actors targeted towards urban policies concerning LHEs. We define governance networks as the essential parties in the governance process and how they change through the developed governance arrangements, meaning the new policies and planning measures.

Housing estates are being focused upon for good reason. European post-socialist countries have a remarkable proportion of their urban population living in modernist mass housing that was built from the end of the 1950s, and was often planned as part of a larger district. In many cities such construction comprises the majority of urban housing and, therefore, contemporary governance practices influence the quality of life for a great many urban residents. Research on post-socialist LHEs is growing too, but much of the recent contributions have tended to study the changing position of the LHEs in urban segregation landscapes (Hess et al. 2018; Tammaru et al. 2016; Leetmaa et al. 2015). Detailed studies on LHE-related urban policies and planning interventions, however, are less systematic and, unfortunately, have not found resonance as a comparison in the global literature tackling the issues of (post)-marketization housing.

Geographically, our focus is on the Baltic countries, which represent ‘fast-track privatisers’, even in the post-socialist privatisation landscape. For those countries that are under study, Estonia and Lithuania, urban housing was almost fully privatised by the end of the 1990s (in the case of socialist-era housing being privatised to the benefit of sitting state tenants). We study governance networks in the post-privatisation period (since about 2000) in two cities: Tartu, the second-largest city in Estonia, which today is a university city that is rapidly becoming internationalised but which, during the Soviet period, was a semi-closed military city (96,123 inhabitants in 2020); and the Lithuanian capital city of Vilnius, the country’s major economic hub (562,030 inhabitants in 2020). As governance research has been dominated by single case studies (da Cruz et al. 2019), we aim to answer the call for a more comparative approach to understand urban policies and governance.

Our research is focused on two questions. First, what urban governance arrangements have emerged via interventions targeted to LHEs and who were the main actors in this process after the almost complete post-socialist privatization of housing. We describe clear gaps in super-homeownership societies’ governance networks, i.e. the missing actors as well as the necessary arrangements, that inevitably occurred after the decade-long institutional vacuum which followed the changes in the political and economic landscape. Second, what mediums and how they helped to fill these initial governance gaps in the post-privatisation period. To understand new governance systems, we zoom in on changes in the governance arrangements during the economically more stable 2010s, and more specifically on the debates about public space between socialist-era blocks. Our fieldwork led us to recognize that it is the public space debate and recent interventions on LHE public spaces that have brought the residential quality of LHEs back on to the public agenda.

Methodologically, we have conducted qualitative field work in Tartu and Vilnius from 2016 to 2020. We started with 13 semi-structured interviews with politicians, high-ranking officials, freelance planners and architects, urban researchers, community activists, and NGO leaders in Tartu in 2016 to understand recently-activated debates concerning Annelinn housing estate. The interviews gave insight on how the governance networks have emerged and functioned following the full privatisation of apartments. Since it also became clear that the core of the discussions pertaining to current governance arrangements was centred on the Annelinn Vision Competition (2014) along with its follow-up activities, we looked more closely at reflections by the interviewees on the results of the vision competition. Along with the interviews we benefited a great deal from desk research with materials related to the competitions (official report of results and conceptual designs), and media coverage helping us to form a better understanding of the competition process, results and reception. We continued our fieldwork in 2017–2020 in the Baltic capitals, focusing on finding a tangible and large-scale intervention similar to the Annelinn Vision Competition for comparison. While fieldwork in all capitals helped to shape our understanding of typical governance peculiarities in fully privatised housing markets (cf. Leetmaa et al. 2018), in this article we present the case of Vilnius and its recent public space initiative in Žirmūnai Triangle under the EU URBACT networking project ‘RE-Block’. Five individual and three group interviews in Vilnius were carried out in 2019 and 2020, addressing the same target group as that for the interviews in Tartu. In addition, the written documents on the Local Action Plan for Žirmūnai Triangle in Vilnius (Vilnius City Municipality 2015) as well as public statements and local media articles became a valuable source of information. All above mentioned interviews were recorded, transcribed and analysed following the principles of open coding.

We start with the literature overview on how the socialist-built housing estates were touched by the globally dominant neoliberal agenda. Next we provide a description of the market experiment (Tammaru et al. 2015), the logic behind it in terms of governance of LHEs within the context of full-homeownership and a resource-and-vision-poor public sector, thus emphasizing the inevitably emerging governance gaps. This is continued by presenting the case studies of Tartu and Vilnius, in which recent initiatives on public space quality have made public urban policies for LHEs more ambitious. Finally, we discuss what path dependencies and discourses affect the formation of governance networks in post-privatised LHEs and also, how it could inform the research on market-based urban governance in modernist estates globally.

1.1 Neoliberalism meets post-socialist conditions in large housing estates

The turn towards ‘super-homeownership societies’ (Chelcea and Druţǎ 2016) in most post-socialist countries in the early 1990s took place at a time when western welfare regimes and urban planning systems were undergoing profound changes (Watt and Minton 2016; Savini 2017). Since the 1980s and 1990s, the trend towards marketization of housing has been rather universal all across Europe and even worldwide (Jacobs 2019; Gillespie et al. 2018). Post oil-crisis conservative governments took the direction in which homeownership was promoted, the formerly strictly regulated rental sector was liberalised, and various market-based solutions were introduced when it came to providing affordable housing (Hochstenbach and Ronald 2020; Jacobs 2019). Even though it soon became obvious that such austerity policies served to reduce the access of vulnerable groups to adequate housing, neoliberalism in housing provision had by this time replaced generous post-war Keynesian welfare regimes that previously shaped urban landscapes in many cities on the western side of the Iron Curtain.

Considering this spirit of the era, it was no wonder that alternatives to the rapid privatisation of housing in Central and Eastern European cities were disregarded in the early 1990s. Francis Fukuyama announced in 1992 (Fukuyama 1992) that the failure of the socialist system was the final proof of the supremacy of liberal democracy and the market economy. Post-socialist European countries attempted to demonstrate their geopolitical belonging to the ‘West’ at any price (Kuus 2002). The dominant discourses ‘back to normality’ and ‘back to Europe’ (Lagerspetz 1999) reflected endeavours to radically move away from a state-controlled economy. According to Broulíková and Montag (2020, 65–66), Lithuania accomplished 95% of apartment privatization already in 1995, while Estonia reached privatization of about 85–90% of the public housing stock by 2001. Some authors (Hirt et al. 2013) criticize the extreme speed of reforms, including the rush towards housing privatisation, since an immeasurable amount of responsibility without the corresponding resources was put on the private owners overnight. Furthermore, when privatisation principles were being set up in the early 1990s, no one was able to predict how decisions being made then would structurally shape urban inequalities and the fortunes of residential environments in the coming decades.

Housing privatisation, as one of the major institutional reforms, most profoundly affected the LHEs as they formed a remarkable share of urban housing stock in post-socialist cities. These residential districts were originally designed with the presumption that housing is the right of urban residents rather than an asset, and that public funding plays a considerable role both in the construction of districts and buildings as well as in their later maintenance (Hess et al. 2018). The former funding schemes, however, faded away completely after the piecemeal privatisation of individual dwellings. The principles for organising the common management of apartment blocks were determined only on a step-by-step basis. Besides, there was no vision regarding how comprehensive urban- and district-level spatial planning should be reorganised. Although successful reforms of the 1990s moved rapidly-privatising countries firmly onto the internationally-approved track of marketization, they also led to a good deal of confusion about how the post-privatised LHEs should further be managed and spatially planned.

What seems to have been a general problem regarding housing estates is their pathological underfunding after the initial construction phase. The reputation and social decline of mass housing districts was, in many European countries, related to a shift of focus in terms of urban planning towards urban renewal programmes in run-down inner-city districts (Murie and van Kempen 2009), leaving LHEs without essential post-construction improvements (Wassenberg 2018). Interesting parallels can be found in contemporaneous socialist cities, where austerity measures were typically applied from the very beginning of mass housing construction. The planned infrastructure and the design of common open areas was never properly finished to the levels shown in the initial plans (Leetmaa and Hess 2019). Furthermore, years-long underfunding in the socialist period was now followed by a complete funding vacuum in the early transition period. Under these circumstances, the infrastructure and public space projects that had been postponed by socialist planners were never finished, and what had been completed now underwent physical aging without any prudent intervention. There was no vision regarding who should be responsible for buildings, the spaces in between the buildings, or the district’s infrastructure.

In addition to terminating public expenditure for housing provision, public social spending was also kept to a minimum at a time when economic restructuring caused employment insecurity and communal costs were rising rapidly. Therefore, the newly-created class of homeowners lacked the resources to improve their housing conditions, and residential buildings on housing estates were left lacking any major investments for a long period of time. The post-privatised situation can be illustrated with three key observations. First, there was no tradition of who was responsible for what. Second, owning did not automatically define upkeep. For example, unreformed State land was not maintained until it was passed on to the municipality during 2010s. Third, none of the owners (municipality, home owners associations, private owners) had the capacity to come beyond their designated ownership borders. For example, for decades, private owners worried only about maintenance within the borders of their apartment. Although the curtailment of welfare programs, including social housing provision, in traditional European welfare states has been much criticized, the governance vacuum in the early transition years in Central and Eastern Europe demonstrates the difference between the neoliberal austerity policies, on the one hand, and the complete collapse of the existing welfare regime and governance system on the other. In post-socialist countries the previous system was now completely discredited.

Market-based arrangements have mainly been criticized from the perspective of declining access to affordable housing (Jacobs 2019). It is noteworthy that during the last three decades the question of affordable housing has never been at the centre of housing debates in Central and Eastern European cities. With some exceptions, e.g. the German rental system (Kitzmann 2017) or late-privatisation countries like Russia (Pachenkov et al. 2019), the affordable housing model that has been applied in post-privatised, post-socialist cities is based mainly on fully-privatised housing stock. The remarkably low share of social housing in post-socialist countries is well-known (Hegedüs 2012). Low-income groups or households without previous assets start or continue their housing careers as homeowners in the cheapest segment of the housing market, with this increasingly being the LHEs. The continuously discredited reputation of social housing ideally corresponds to the phenomenon that Chelcea and Druţǎ (2016) refer to as ‘zombie socialism’—many strategic directions in ultraliberal ex-socialist societies continue to be indisputable because of the fear that alternative decisions may be associated with the former regime.

After the initial fundamental reforms, the global neoliberal agenda has accompanied the evolvement of housing policies and urban planning in post-socialist European countries. We know from literature that both the reputation (Kovács and Herfert 2012) as well as the social composition (Kährik et al. 2019) of various residential environments has changed during the post-socialist decades, or has even reversed when comparing the relative housing market position of the LHEs. This is an expected result of non-interventional urban planning that has been supporting the ‘natural’ dynamics of urban development. Firstly, the urban planning apparatus in metropolitan regions has been busy with planning new up-market housing segments (such as the formation of new suburban districts and the revitalisation of inner cities). Secondly, no strategy has been put in place that would address ongoing stigmatisation, a change in social composition, or the physical deterioration of post-privatised LHEs. Although there is a global consensus that the market does not serve to solve the housing crisis for low-income residents, this discussion has not yet been opened up in Central and Eastern European super-homeownership societies.

To conclude, the ‘full-market experiment’ (Tammaru et al. 2015; Aidukaite 2014) in housing soon met the resource and vision-free urban governance of post-privatised LHEs in Central and Eastern European cities. In parallel with the general growth in welfare, the demand for better living conditions was growing, leaving the fortunes of LHEs—the remnants of the former housing system—to be shaped by market forces, which literally meant neglect. In the global context of the marketization of housing provision, there were also no good governance practices in place to be followed (these being acceptable as the ‘Western’ ones), except in terms of the rhetoric of celebrating homeownership.

1.2 After the vacuum – the emerging governance system in post-privatised LHEs

As a rule, the post-socialist Eastern and Central European cities have not applied any ambitious public urban regeneration programmes. Although there are quite optimistic assessments of the social stability of post-socialist housing estates (Ouředníček 2016), many recent segregation studies demonstrate that LHEs gradually lose their high social-status residents, attract low-income groups and newcomers, including immigrants from less affluent countries (Kährik et al. 2019; Valatka et al. 2016; Přidalová and Hasman 2018). In multi-ethnic housing estates of post-Soviet cities, the emerging socio-economic segregation patterns increasingly overlap with ethnic segregation lines (Tammaru et al. 2016; Burneika and Ubarevičienė 2016).

Yet, it still seems that socialist-era housing estates are considered ‘too big to fail’. Our fieldwork in Estonia and Lithuania showed that concerns about the changing segregation landscape in cities have mainly remained in academic circles and the political players tend to perceive this as a somewhat inflated topic. As an interviewee who is an experienced consultant in urban spatial issues in Vilnius has put it: ‘Since there is no real data to show the problem, no one is talking about it, saying look, people are segregated, they lack this or that. And since no one is saying that, the politicians simply ignore it.’ Similarly, in Estonia the LHEs are treated politically as any other urban neighbourhood where living conditions are ‘gradually improving’ as the municipality increasingly invests in infrastructure, public facilities, and services across the city. Although there is some discussion on ‘unfair stigmatisation’, the discourse that LHEs may be threatened by a real social downward spiral has not reached the political agenda.

There is indeed some basis for the claim of policymakers that cities are constantly improving the living conditions in LHEs since the municipal investment capacities have increased. Because socialist-era apartment districts make up a large part of the electorate, ignoring these areas when making improvements in terms of streets, public transport, recreation facilities, kindergartens etc. is impossible. Simultaneously, we must consider that society itself, its needs, demands and understanding of a good quality residential environment have changed. Moderate investments in modernist apartment building areas do not put them on an equal footing with popular upmarket districts of today. What’s more, in a typical neoliberal atmosphere, financial resources for major urban development projects mainly originate from private investors and the trend of commercialisation increasingly shapes the spatial milieu of the post-privatised LHEs. New shopping malls, recreation centres, and housing projects are often built in the LHEs as infills due to larger consumer population density and available land. On a positive side, new developments serve as the previously-missing infrastructure and help to open up LHEs to the rest of the city. Therefore, indeed, serving to ‘diversify the LHEs functionally’. On a negative side, the densification of LHEs disrupts the former spatial structure of these master-planned areas, for example by absorbing green spaces or reducing walkability. New nearby housing projects often emphasise the presence of schools and kindergartens (built already in the socialist-era) in their marketing process, but at the same time distance themselves consciously from the image of a socialist-era estate.

The initial confusion with house-level management has been resolved to an extent over time by clarifying the rules for majority decisions. In Estonian cities, the establishment of homeowner associations (HOAs), where every single apartment owner is a voting member, has been encouraged since the mid-1990s and has also been made obligatory from January 2018. The leaders of the HOAs were often chosen from the residents themselves, mostly without any previous experience in house management or legal issues. Initially merely responsible for collecting contributions for maintenance and handling urgent building repairs, the HOAs have become strong non-profit players that undertake full responsibility for complicated building renovation processes and in applying mortgages from commercial banks. The respective national legal framework has evolved since the 1990s, and great efforts have been made in terms of capacity building (such as the systematic training of HOA leaders), with the Estonian Union of Co-operative Housing Associations (founded in 1996) being the key player in this institutional landscape. In Lithuania the goals of HOAs fall in line with their Estonian counterparts, but the forming process has been somewhat slower and not obligatory. The legislation for HOAs was adopted as early as 1995, however there is no national level comparable organisation for the Estonian counterpart, as the HOAs are managed by market-led administrative organisations that have monopolized the market. Lithuanian interviewees emphasised the lack of motivation of residents to take up the responsibility for their building and a psychological barrier when it comes to considering the possibility of one building belonging to everyone. Yet procedures for majority decisions (50% flat owners plus one) have also settled down in Lithuania when it comes to initiating refurbishment work by their owners on apartment blocks that are 40–60 years old.

Despite the relative stabilisation of the organisational landscape, e.g. the forming of HOAs, structural inequalities of the ownership market still remain. Gathering owners’ financial contributions, applying loans from banks, managing refurbishment projects, and applying for public renovation grants all require professionalism from the association leaders and administrators as well as solvency from homeowners (Lihtmaa et al. 2018). These capacities, however, are unequally distributed in urban space. Adding to that, the link between tenants that rent from private owners and house-level management is non-existent in both countries. Because owners are the members of HOAs, the private tenants tend to only communicate with the owners, not with the HOA, resulting in systematic exclusion of tenants (estimated at 20 percent in the LHEs of both cities) in districts from which former owners have departed at a higher rate. Theoretically tenants may have a say in the changes of their immediate surroundings. However, as renting is usually a temporary housing choice, tenants are often less motivated to systematically care about what happens outside their apartment door. In the background of all these arrangements, however, is the neoliberal principle of non-intervention.

The understanding that LHEs are actually a structural problem has begun to emerge from two subject areas. Firstly, the EU-level energy efficiency goals and the role of housing stock in achieving them, which has already found some coverage in research literature (Kuusk and Kurnitski 2019). While cities have been able to give only minor grants for building improvements, the 2010s marked the period in both countries in which the structural need to invest in energy efficiency for socialist-era residential buildings has been acknowledged at the national level. Secondly, in connection with the debate on the quality of public space in the LHEs. The increasingly recognised need to improve and modernise public space between the apartment blocks in the LHEs has so far received relatively little attention in research literature (Kilnarová and Wittmann 2017; Vasilevska et al. 2014). In the following case studies, we emphasise how the public space discussions have helped to fill gaps in post-privatisation governance networks in the LHEs.

1.3 Turning attention to public spaces – Annelinn Vision Competition and Žirmūnai Triangle Action Plan

The purely market-led process under neoliberal consensus has overlooked some important issues in organising daily life and space in the LHEs. For a very long time, public space in between the apartment blocks seemed to be a left-over domain for which there was no institutional interest (Figs. 1, 2). The rather resource-poor apartment owners were busy maintaining the buildings in a satisfactory condition. At the time when the LHEs were constructed, a collective management model was envisaged both for buildings and districts. The local government authority as a new public power at the local level was in no hurry to take responsibility either, due to limited financial resources, but certainly also because there was no vision about what should be the future of the LHEs—any communal property or collective responsibility was out of the question in the neoliberal age.

Both in Lithuania and in Estonia, however, the 2010s demarcate the period in which discussions about public space in cities in general began to gain momentum. This often coincided with nascent neighbourhood activism (Kljavin and Kurik 2016), standing for good quality public spaces and the comfort of pedestrians and cyclists, or maintaining the human dimension in new construction projects during the economic boom years. A clear spatial imbalance occurred in these discussions. First of all, the upmarket segments, urban districts that received high-income and younger residents (gentrification and low-density quarters), pushed the new discourses, while the LHE communities initially remained passive (Holvandus and Leetmaa 2016). With a degree of time-lag, both Tartu and Vilnius in the mid-2010s saw more comprehensive initiatives being undertaken with a clear aim of revitalising public spaces in LHEs.

1.4 Vision competition for Annelinn in Tartu, Estonia, 2014–2015

Annelinn (with 26,755 inhabitants, making up 27% of the total urban population) is the main LHE district in Tartu, which is often portrayed as the equivalent of the socialist spatial legacy of the city. The district was built in the 1970s and 1980s. It was meant to consist of four mikrorayons, out of which only two were finished prior to the collapse of the USSR. The district consists mainly of five and nine-storey prefabricated panel blocks (Figs. 3, 4). The master plan divided Annelinn into radial sectors by streets, along with the provision of a comfortable network of pedestrian paths that connected the mikrorayons. Together with schools and kindergartens that were close to homes, these made Annelinn a walkable district, a prestigious place for families in the late Soviet decades. As Annelinn was built in times which saw intensive immigration, the proportion of Russian-speakers is somewhat higher here (in Tartu as a whole it is 17%, while in Annelinn it is 25%). Today the LHE experiences parallel processes of ageing and inflow of younger transitory households (students and other private tenants). Compared to the late Soviet years, the social reputation of the district has reversed (Leetmaa et al. 2015), as high social-status homeowners and Estonian-speakers leave Annelinn more frequently.

In the 1990s and 2000s urban policy discussions did not touch Annelinn as a specific target area. Although unfinished, the buildings, infrastructure, and outer spaces in Annelinn were still relatively fresh. The first organised debate on the future of Annelinn was organised by the Estonian Centre of Architecture in 2011 within the wider series of ‘Stone City Forums’ in various Estonian cities. The forums were held on the notion that since the erection of LHEs in Estonia, these vast mass constructed areas have been ignored by public policies until today (2012) with no strong vision for comprehensive development. Interestingly, this debate was being initiated by professional architects, with urban researchers from other disciplines and representatives of the municipality both on board. The organisers carried out preparatory meetings with local residents to ‘develop community activism in otherwise passive LHEs and to facilitate cooperation between local residents and architects’ (Estonian Centre of Architecture 2011). A young architect with living experience in a LHE neighbourhood commented upon the emerging professional interests:

‘Architects have always been interested in LHEs... Today you rarely have a chance to design and create such vast areas... Like in every discipline, you have sample tasks or problems: stone cities are sample problems of urban planning... Certain architects created these areas some time ago and now we should sort out the mess they made. [Stone cities] are our professional responsibility.’

It seems as if the architectural community feels a kind of professional debt, understanding the need for more systematic action when dealing with LHEs. These forums and other similar activities from the same period succeeded in extending the interest towards LHEs from small professional circles to a wider public discussion. Even though the subject was not yet part of the political agenda, architects and officials in city offices of the new era became involved. This collaboration led to perhaps the most influential project in recent decades in Annelinn or in LHEs in Estonia for that matter. In the years 2014–2015, Tartu City Government, with strong professional support from the Estonian Association of Architects, organised the Annelinn Vision Competition with the aim of improving public spaces between the blocks.

The city had pre-decided that the proposals should deal with the plots that were owned by the city, where it could later legally intervene with moderate investments. This spatial focus reflects the mess that was created by the land privatisation process (which paralleled the privatisation of homes). Some HOAs privatised larger areas of land while others only privatised a few metres around the buildings, leaving the remaining land within the LHE area either as ‘unreformed state land’ (without any systematic care for a considerable period of time) or municipal land. Concerning the immediate surroundings of buildings and internal courtyards, the municipality has leaned towards a position in which it would rather ‘wait and see how far from their staircases and car parks the owner associations are motivated to proceed with their arrangements’ (Tartu municipality planning official). Therefore, even the municipality could not ignore the mosaic of post-privatisation land ownership holdings.

A total of nineteen visions were submitted, and three winning projects—Anne Garden City, Delta, and Fresh Air—were chosen for further elaboration and design of a public space renovation project, but ideas from other proposals were also used in the follow-up discussions. Anne Garden City emphasised gardening activities that could potentially bridge social distances (including ethnic divides), and create personalised ‘islands’ instead of a ‘collective’ space. Delta turned attention towards a network of comfortable and logical pedestrian paths. Fresh Air proposed a diverse set of activity pockets to functionally diversify outside activities. A common key idea in many visions was to turn the courtyards between the blocks into semi-public zones in order to better differentiate between private, semi-public, and fully public spaces. Furthermore, almost all of the visions longed for a human-scale landscape in place of the socialist planning which devoted its attention to large scales.

The competition’s sub-goal was to activate the local community. This became a reality in the follow-up activities. Following the competition’s conclusion, discussions were held with the inhabitants at local meeting places, but also elsewhere in the city. Again, the professional community played a remarkable role in this process. The Estonian Centre of Architecture organised a seminar for Estonian urbanists and other active citizens in Tartu, together with an exhibition of the competition posters in Annelinn’s local library and in a shopping mall so that it could reach a wider urban audience. One of the key organisers of the vision competition initiated the creation of a website which, besides carrying competition materials, contained information about the history of Annelinn and activities that were going on locally. As such, the competition not only produced new design ideas, but also provided a good experience of cooperation for active people and organisations, both at the local and city-wide levels.

The key outcome of the vision competition was the refurbishment of the socialist-planned pedestrian arc in 2017 using the competition winners’ ideas for inspiration (Figs. 5, 6). The municipality used EU funding for the sustainable development of urban regions to finance the work—1.8 million euros—one of the largest recent investments to be made into public spaces in Tartu and also into public spaces in any Estonian LHE. Another interesting development after the competition had finished was the establishment of Annelinn Neighbourhood Association in 2016. Although direct cause-and-effect relationships are difficult to prove, according to our observations the activation of spatial discussions by external experts played an important role in activating the local community. Today Annelinn Neighbourhood Association represents an important link in the LHE governance network by dealing with issues that fall outside the scope of the HOAs, such as, for example, communicating with the city government, organising neighbourhood festivals, or proposing interesting local ideas to the annual city-level participatory budget.

1.5 Local Action Plan for Žirmūnai Triangle in Vilnius, Lithuania, 2013–2015

Žirmūnai Triangle (with 12,000 inhabitants, making up 2% of the urban population) in Vilnius was built between 1965 and 1968. It is one of the mikrorayons of the Žirmūnai eldership, which was nominated for the USSR State Prize in 1968. The Triangle serves as a typical self-contained socialist mikrorayon with clear residential areas, local educational infrastructure, and shops and green areas (Vilnius City Municipality 2015), surrounded by major streets that diminished traffic inside the residential zone. The housing stock is now almost sixty years old. Žirmūnai Triangle is also multi-ethnic: containing 60% Lithuanians, 17% Russians, and 14% Poles. Compared to other peripheral LHEs in Vilnius, Žirmūnai is located very close to the historical city centre (at a distance of three kilometres).

More or less in the same period as the competition in Tartu, Vilnius City decided to participate in the EU URBACT II networking project, ‘RE-Block, REviving high-rise Blocks for cohesive and green neighbourhoods’. Žirmūnai Triangle was selected as the target area. The goal for Vilnius City was to elaborate a ‘local integrated action plan’ (using the URBACT vocabulary) for the revitalisation of Žirmūnai Triangle. As there are many other LHEs in Vilnius, this revitalisation project was supposed to serve as a model of good practice that could be transferred to other LHEs in the city. Participation in a European network brought in a lot of external expertise for the project and pre-defined the participatory approach: a diverse URBACT Local Support Group was formed, consisting of representatives of the city government and other public bodies (such as the local school, kindergarten, and library, along with local politicians, business owners, active residents, researchers, students, and others. The most innovative aspect of Žirmūnai Triangle action plan, in the midst of non-interventional approaches being practised in the post-privatisation period, was probably its level of detail. The project defined which individual projects should be realised in which years, while also determining funding sources and responsible bodies (Vilnius City Municipality 2015).

As in the case of Annelinn, the focus in Žirmūnai Triangle was on public space. Vilnius City had previously defined ‘integrated urban development areas’ which also included Žirmūnai eldership as being an attractive area that was close to the city centre. This included efforts to encourage the practise of retrofitting socialist-era apartment buildings in Žirmūnai, but this process has not taken place as quickly as expected. Working with Žirmūnai Triangle in the URBACT network brought about a new approach, with the city taking the position that the LHEs needed a more comprehensive solution when it came to combining building retrofits with the revitalisation of areas around the buildings. The URBACT-guided local action plan in Žirmūnai Triangle determined new standards for good quality public space in modernist LHEs.

Although clearly initiated by the municipality in Vilnius, the city hired external experts to moderate events and debates of the Local Support Group, and also to prepare scenarios and document results. In the first project phase, state-of-the-art processes were formulated. It was stated that the Triangle itself has good connections but the internal network of roads and pedestrian paths is illogical. Also, despite there being a good many green spaces, there is a lack of good quality spaces that would serve to make local people feel safe and allow them to identify themselves with their home surroundings. Although the day-care and school infrastructure is sufficient, today there should be more facilities for the elderly. As the area was densified with new residential buildings during the economic boom years, attention was also placed on the desire that in-fills, if possible at all, should not dismantle the neighbourhood’s spatial structure.

The external experts were able to propose three alternative spatial scenarios based on collected ideas from the formed URBACT Local Action Groups, a survey that was conducted amongst residents under the project (Vilnius City Municipality 2015, 22–23), and on site observations. Out of the scenarios participants preferred the one entitled Neighbourhood, which proposed the creation of mini-neighbourhood units (based on small groups of apartment buildings) out of the previous socialist mikrorayon (Fig. 7). This spatial reorganisation was supposed to motivate people to participate in taking care of their immediate courtyards, because it made it possible to more clearly divide up the anonymous ‘collective’ space (the much-criticised ‘no-man’s-land’) by turning it into recognisably private, semi-public, or public spaces. With this alternative, they also addressed spontaneous ‘gating’ that had already occurred in the area (Fig. 8). Some of the HOAs had surrounded their land with fences to better mark the territory they own. On the one hand, it surely deepens the sense of ownership, but on the other, it contradicts the ideas of collective space, enhancing the apparent conflicts between the manifestation of socialist and neoliberal ideas in physical space. This, however, was not only meant to be a model of spatial portioning, the proposal also included the idea of administrative decision-making at the level of the new units.

New spatial division in Žirmūnai Triangle (2015)

Many other new solutions were proposed on top of that. A new public space system was supposed to include a main square, as well as other smaller squares and activity pockets; an internal street was designed to connect the new small neighbourhoods, with priority for pedestrians and cyclists; parking was partially relocated along the major streets to relieve parking pressure in the courtyards; and better access to the adjacent River Neris was emphasised. Many new ideas included novel proposals for diversifying housing stock, such as allowing separate entrances and terraces for ground floor flats, and designed extensions for balconies and penthouses to extend top floor flats. All of these proposals had a wider aim of supporting the systematic revitalisation of the area rather than renovating only single buildings, and in the longer run the aim was to change the reputation of the LHE, as well as its social composition. The European project ended with a detailed funding schedule, and many smaller sub-projects were supposed to receive funding in the 2015–2020 period.

Most of the planned activities, however, have so far remained on paper. An external consultant in the project who was interviewed by us argued that one of the reasons may be the top-down decision about undertaking this detailed European project in the Žirmūnai Triangle:

‘That was the weakest part of the project and is probably why it has not been implemented... There are LHE areas in Vilnius that have far deeper issues. The first question for me was why are we here? ...With the final presentation to the city council we went directly to the mayor, but in the next month we had elections (in 2015) and a new mayor was elected who asked exactly the same question: why Žirmūnai Triangle? ...and so, the project implementation was put on hold.’

Therefore, although community engagement was carried out with unprecedented depth, there was no political consensus on funding. Also, in regard to communications with the local community, some members of the former Local Support Group admitted that post-project communications with local people had not been ideal: ‘People have the feeling that the project is dead and buried and nothing has changed’ (interview with a former politician). In 2020 the city has finally begun building a new cycle lane in Žirmūnai Triangle, but the implementation was temporarily put on hold, because a number of locals expressed surprise that so much of the existing greenery was due to be cut down. This illustrates the need for continuity in community involvement in order to be able to achieve any real change in the residential environment.

Although we have not yet seen any extensive revitalisation of Žirmūnai Triangle, the act of participating in the international URBACT network and the action plan that had to be prepared has had a tangible impact on Vilnius' urban policies in relation to LHEs. The city is increasingly targeting comprehensive urban renewal projects in which the refurbishment of the buildings and the outdoor space should go hand-in-hand. The most recent policy tool, the Vilnius Municipal Neighbourhood Programme, was launched in 2017. This programme contributes to the development of a hitherto non-existent neighbourhood-level governance model. A group of neighbouring blocks of flats (forming mini-neighbourhoods) with common facilities and courtyards can jointly apply for financial support (up to 10 euros per square metre) to reorganise and renovate their outdoor spaces, infrastructure, and greenery. Vilnius City has allocated a long-term budget to this process and has appointed a public body to coordinate these neighbourhood-level renovation projects.

1.6 Public space as a medium for governance networks

As in the West, so in socialist countries the criticism towards uniform and unfinished public space was raised already during the heyday of mass housing construction (Leetmaa and Hess 2019; Wassenberg 2013, 15, 34, 134). Whilst the supply of plentiful free space was originally meant to be highlighted as a key quality of modernist housing areas (Sendi et al. 2009), actual practice showed that this was one of the reasons for their failure (Wassenberg 2013; 2018). It seems that in the LHEs some of the key roles of any public space (Fincher and Iveson 2008; De Chiara et al. 1995) were ignored: collectively owned open areas did not serve as spaces for social interaction and failed to support place-connectedness. Privatisation, unfortunately, did not exactly remedy the situation, since the notion of public space became unclear in the fragmented landscape of post-privatisation land ownership. The task of sharing responsibilities and investing in public spaces became a complicated one. The LHEs were really left without any particular care: municipalities treated LHEs as any other urban districts that may be in need of some infrastructure-related improvement. Minimal and short-term interventions, unfortunately, have not resolved the planning problems, but deepened them—the need for more parking spaces and better connectivity with other neighbourhoods or smaller and more defined spaces for encounters. Although studies that cover residential satisfaction usually place green areas and public space—especially in housing estates—quite high in terms of place satisfaction (Kilnarová and Wittmann 2017), it has taken almost three decades for public space planning to become one of the key topics in post-socialist, post-privatised LHEs. Even now, we have evidence of how market-oriented projects still ignore the need for public space (Vasilevska et al. 2014), or how architects are hired for marketing purposes to carefully design community elements (Majerowitz and Allweil 2019).

Because LHEs were continuously overlooked on the policy agenda, the governance networks were disconnected and no successful arrangements yet formed during the 1990s. By the late 2000s, the state’s capacity to provide finance for retrofitting of buildings had grown, with the support of external funding (EU and emissions trading). Although HOAs struggled with block-level administration duties, the energy efficiency of buildings, as well as their physical appearance, began to change for the better. Our analysis of two successful public space interventions attests that against growing national level capacity, these emerging governance networks and arrangements were linked together at the neighbourhood level in Tartu and Vilnius. We argue that it was the architects and other urban professionals who were able to stimulate community activism and raise urban planning interest towards post-privatised LHEs to new levels. Interventions that took place in Tartu were managed for the most part by architects, while in Vilnius it was by the city government. In both cases, however, the professional community of architects brought their knowledge, skills, and capacity into the process.

It appears that finding new and comprehensive solutions to this modernist challenge is considered by the younger generation of the same professional community as being a challenge of today. The main focus of contemporary urbanists is on how to bring more human scale to existent spaces. Interestingly, the most remarkable spatial concept that was developed by the experts in both cities was the new proportioning of outer spaces in the LHEs, better differentiating to whom various LHE zones belong (private—semi-public—public). The solution is not new. Similar purposeful gating and design principles have been applied elsewhere, for example in the résidentialisation approach of French LHEs (Lelévrier 2013). In addition, as some spontaneous gating has anyway occurred in post-privatised Estonian and Lithuanian LHEs, it seems to be a natural expectation of LHE residents.

Based on our analysis, we are convinced that debates on public space helped to bring the LHEs into the public agenda. After decades-long neglect and single policies, the Neighbourhood Programme in Vilnius, launched in 2017, is a superb advancement towards a more integrated approach in public LHE policies in post-socialist cities. As a comparison, the much more comprehensively-discussed segregation topic (Tammaru et al. 2016) has not yet turned LHEs into priority areas in urban planning. We suggest that segregation will likely become a more relevant issue in the future, to fill the gap in more systematic people-based approaches in policies (Hess et al. 2018), tackling the increasing needs of households that use LHEs as a springboard when moving to the city, or who do not have any previous property assets. Systematic attention to spatial qualities may also serve as a gateway into this world. For example, when, in super-homeowner societies’, private tenants are ‘naturally’ excluded from decisions on improving residential buildings, there is no legal basis to exclude tenants from public space discussions. Also, since public space and living environment issues seem to engage residents more and more (Kljavin et al. 2020), i.e. we care where we live and how the environment is perceived, neighbourhood activism has begun to be less passive in LHEs compared to 5–10 years ago (Holvandus and Leetmaa, 2016). Furthermore, since public space interventions have been able to bring together different level governance actors, signalling to public bodies the collaboration interest of local communities, the public sector has been given a clear sign of the need for it to help manage the fragmented post-privatised urban landscape.

2 Conclusions

Compared to the West, marketization hit the post-socialist LHEs only in the 1990s. The complete privatisation of the housing stock has been an extraordinary experiment in marketization discourse. The global neoliberal agenda, combined with the post-socialist discourse of ‘returning to normality’, has meant marketization at any price. No one stopped to imagine the full outcomes of such new path dependencies that could result from turning into a super-homeownership society. Although three decades have passed since privatisation was started in post-socialist cities, in some aspects the impacts of socialism in the form of the ‘zombie’ (Chelcea and Druţǎ 2016) are still perceivable, be it, for example, the issue of affordable housing or resistance to dealing with anything that is ‘collective’.

The governance experiences of the post-socialist, post-privatised LHEs help to envision the possible future of the ongoing marketization of housing on a global basis. When there will be more single owners and the tenure composition becomes diverse and fractured in LHEs, the efforts of coordinating spatial planning and urban revitalisation become far more complicated. It has taken three decades in the post-privatised LHEs of Central and Eastern European cities to build new and more-or-less balanced governance networks. Also, the recent Baltic lessons show us that the long-lasting governance vacuum and extreme austerity measures may have serious consequences: the longer the period of neglect, the worse will become the condition of the buildings and the public spaces, and the more difficult it will be to build up local, inclusive governance networks.

It became evident from our case studies that the return of the public sector is an expected process. Stabilisation of public budgets and external funding sources have brought new levels of confidence to post-privatised, post-socialist LHEs. However, compared to post-socialist cities, the western austerity policies have been less extreme, because almost full-privatisation has never been achieved nor been the aim (Hess et al. 2018). Even now, when we witness the resurgence of the State in LHE related urban policies, the western austerity measures have historically still been more generous than in post-privatised cities now. Nevertheless, it has been acknowledged on a municipal level that LHEs need long-term and thought-out vision, where the interventions aim at providing both retrofitting of modernist apartment blocks and neighbourhood-level public space renewal arrangements.

Path-dependency in post-socialist cities has usually been conceptualised in terms of continuities from the preceding socialist period. Less discourse exists about the possible path-dependencies of the privatisation tracks that are chosen. In comparison, for example in the UK, Ireland and Spain, marketization has led to financialization and the growth of unregulated rental sector (Byrne 2020), in Belgium we can differentiate policies targeted at publicly and privately owned LHEs (Costa and de Valk 2018). On a challenging aspect, privatisation created a confusing mosaic of private owners in post-socialist housing districts, which can be difficult to solve later and determining that future urban planning tiptoes around these arrangements. Another possible and more interesting dependency of the full privatisation decision, the effects of which are yet to be seen, is related to global financialization of housing (Kitzmann 2017). A very fragmented landscape of private owners might form a far less attractive target for corporate investors compared to institutional property owners (Jacobs 2019). In this context, many post-socialist, post-privatised housing estates may have an advantage today when it comes to the shortcomings of the financialization process in the housing sector in many other countries. Firstly, the effects and challenges of financialization are postponed in a post-privatized context. Secondly, since LHEs still today and in the foreseeable future make up a much larger share of the housing sector in post-socialist cities than in their western counterparts, they are still not as marginalized as in western cities. Thirdly, we believe that the newly created governance arrangements provide the necessary incentive to objectively improve the living environment in post-privatized LHEs. Thus, new models for market-based urban governance serve as a good lesson for other urban environments where (full-)marketization is nowadays an unavoidable reality.

References

Aidukaite, J. (2014). Housing policy regime in Lithuania: Towards liberalization and marketization. GeoJournal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-014-9529-y

Broulíková, H. M., & Montag, J. (2020). Housing privatization in transition countries: Institutional features and outcomes. Review of Economic Perspectives. https://doi.org/10.2478/revecp-2020-0003

Burneika, D., & Ubarevičienė, R. (2016). Socio-ethnic Segregation in the Metropolitan Areas of Lithuania. Sociologický Časopis. Czech Sociological Review, 52(6), 795–819.

Byrne, M. (2020). Generation rent and the financialization of housing: A comparative exploration of the growth of the private rental sector in Ireland, the UK and Spain. Housing Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1632813

Chelcea, L., & Druţǎ, O. (2016). Zombie socialism and the rise of neoliberalism in post-socialist Central and Eastern Europe. Eurasian Geography and Economics. https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2016.1266273

De Chiara, J., Panero, J., & Zelnik, M. (1995). Time-saver Standards for Housing and Residential Development. Mcgraw Hill.

Costa, R., & de Valk, H. (2018). Sprouted all around: The emergence and evolution of housing estates in Brussels, Belgium. In D. Hess, T. Tammaru, & M. van Ham (Eds.), Housing Estates in Europe Poverty, Ethnic Segregation and Policy Challenges (pp. 145–166). Berlin: Springer.

da Cruz, N. F., Rode, P., & McQuarrie, M. (2019). New urban governance: A review of current themes and future priorities. Journal of Urban Affairs. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2018.1499416

Estonian Centre of Architecture. (2011). Tartu Kivilinnafoorum (Stone City Forum in Tartu). Retrieved May 24, 2020 from, https://annelinnaportaal.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/tartu-klf-esitlus11.pdf.

Fincher, R., & Iveson, K. (2008). Planning and diversity in the City. Palgrave Macmillan.

Fukuyama, F. (1992). The End of History and the Last Man. Free Press.

Gillespie, T., Hardy, K., & Watt, P. (2018). Austerity urbanism and Olympic counter-legacies: Gendering, defending and expanding the urban commons in East London. Society and Space. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775817753844

Hegedüs, J. (2012). The transformation of the social housing sector in Eastern Europe: A conceptual framework. In J. Hegedüs, M. Lux, & N. Teller (Eds.), Social housing in transition countries.Taylor and Francis.

Hess, D., Tammaru, T., & van Ham, M. (2018). Lessons learned from a pan-european study of large housing estates: Origin, trajectories of change and future prospects. In D. Hess, T. Tammaru, & M. van Ham (Eds.), Housing Estates in Europe Poverty, Ethnic Segregation and Policy Challenges.Springer.

Hirt, S., Sellar, C., & Young, C. (2013). Neoliberal doctrine meets the eastern bloc resistance appropriation and purification in post-socialist spaces. Europe-Asia Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2013.822711

Hochstenbach, C., & Ronald, R. (2020). The unlikely revival of private renting in Amsterdam: Re-regulating a regulated housing market. Environment and Planning A Economy and Space. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X20913015

Holvandus, J., & Leetmaa, K. (2016). The views of neighbourhood associations on collaborative urban Governance in Tallinn Estonia. Planext Next Generation Planning, 3, 49–66.

Jacobs, K. (2019). Neoliberal housing policy: An international perspective. Routledge.

Kilnarová, P., Wittmann, M. (2017). Open Space between Residential Buildings as a Factor of Sustainable Development – Case Studies in Brno (Czech Republic) and Vienna (Austria). IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci., https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/95/5/052008

Kitzmann, R. (2017). Private versus state-owned housing in Berlin: Changing provision of low-income households. Cities. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2016.10.017

Kljavin, K., Kurik, K.-L. (2016). Searching for baltic urbanism – from Ad Hoc Planning to Soft Urbanism. Estonian Urbanists’ Review U 19. Retrieved May 20, 2020 from, https://www.urban.ee/issue/en/19#

Kljavin, K., Pirrus, J., Kurik, K.-L., Pastak, I. (2020) Urban activism in the co-creation of public space. Estonian Human Development Report. SA Eesti Koostöö Kogu: Tallinn. Retrieved Jan 8, 2021 from, https://inimareng.ee/en/urban-activism-in-the-co-creation-of-public-space.html

Kovács, Z., & Herfert, G. (2012). Development pathways of large housing estates in post-socialist Cities: An international comparison. Housing Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2012.651105

Kuus, M. (2002). European integration in identity narratives in Estonia: A quest for security. Journal of Peace Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343302039001005

Kuusk, K., & Kurnitski, J. (2019). State-Subsidised Refurbishment of Socialist Apartment Buildings in Estonia. In D. Hess & T. Tammaru (Eds.), Housing Estates in the Baltic Countries (pp. 339–355). Springer.

Kährik, A., Kangur, K., & Leetmaa, K. (2019). Socio-economic and ethnic trajectories of housing estates in Tallinn, Estonia. In D. Hess & T. Tammaru (Eds.), Housing Estates in the Baltic Countries (pp. 203–223). Springer.

Lagerspetz, M. (1999). Postsocialism as a return: Notes on a discursive strategy. East European Politics and Societies. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888325499013002019

Leetmaa, K., & Hess, D. B. (2019). Incomplete service networks in enduring socialist housing estates: Retrospective evidence from local centres in Estonia. In D. Hess & T. Tammaru (Eds.), Housing Estates in the Baltic Countries (pp. 273–299). Springer.

Leetmaa, K., Holvandus, J., Mägi, K., & Kährik, A. (2018). Population shifts and urban policies in housing estates of Tallinn, Estonia. In D. Hess, T. Tammaru, & M. van Ham (Eds.), Housing Estates in Europe Poverty, Ethnic Segregation and Policy Challenges (pp. 389–412). Berlin: Springer.

Leetmaa, K., Tammaru, T., & Hess, D. B. (2015). Preferences toward neighbor ethnicity and affluence: Evidence from an inherited dual ethnic context in post-soviet Tartu Estonia. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2014.962973

Lelévrier, C. (2013). Social mix neighbourhood policies and social interaction: The experience of newcomers in three new renewal developments in France. Cities. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2013.03.003

Lihtmaa, L., Hess, D., & Leetmaa, K. (2018). Intersection of the global climate agenda with regional development: Unequal distribution of energy efficiency-based renovation subsidies for apartment buildings. Energy Policy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.04.013

Majerowitz, M., & Allweil, Y. (2019). Housing in the neoliberal city: Large urban developments and the role of architecture. Urban Planning. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v4i4.2298

Murie, A., & van Kempen, R. (2009). Large housing estates, policy interventions and the implications for policy transfer. In S. Musterd, R. Rowlands, & R. van Kempen (Eds.), Mass Housing in Europe: Multiple Faces of Development, Change and Response (pp. 191–210). Palgrave Macmillan.

Ouředníček, M. (2016). The relevance of “Western” theoretical concepts for investigations of the margins of post-socialist cities: The case of Prague. Eurasian Geography and Economics. https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2016.1256786

Pachenkov, O., Chernysheva, L., Korableva, E., Shirobokova, I., & Gizatullina, E. (2019). Governance Analysis. Research project: ‘Estates After Transition’ report on work package 2. Retrieved May 20, 2020 from, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1KBMKnJuW2QjaKP9gMp0OS84zd6CEQTGn/view.

Přidalová, I., & Hasman, J. (2018). Immigrant groups and the local environment: socio-spatial differentiation in Czech metropolitan areas. Geografisk Tidsskrift-Danish Journal of Geography. https://doi.org/10.1080/00167223.2017.1370382

Savini, F. (2017). Planning uncertainty and risk: The neoliberal logics of Amsterdam urbanism. Environment and Planning A Economy and Space. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X16684520

Sendi, R., Aalbers, M. B., & Trigueiro, M. (2009). Public space in large housing estates. In R. Rowlands, S. Musterd, & R. van Kempen (Eds.), Mass Housing in Europe: Multiple Faces of Development, Change and Response (pp. 131–156). Palgrave Macmillan.

Tammaru, T., Kährik, A., Mägi, K., Novák, J., & Leetmaa, K. (2015). The ‘market experiment’: increasing socio-economic segregation in the inherited bi-ethnic context of Tallinn. In T. Tammaru, S. Marcińczak, M. van Ham, & S. Musterd (Eds.), Socio-Economic Segregation in European Capital Cities (pp. 333–357). Routledge.

Tammaru, T., Musterd, S., van Ham, M., & Marcińczak, S. (2016). A multi-factor approach to understanding socio-economic segregation in European Capital Cities. In T. Tammaru, S. Marcińczak, M. van Ham, & S. Musterd (Eds.), Socio-Economic Segregation in European Capital Cities (pp. 1–29). Routledge.

Valatka, V., Burneika, D., & Ubarevičienė, R. (2016). Large social inequalities and low levels of socio-economic segregation in Vilnius. In T. Tammaru, S. Marcińczak, M. van Ham, & S. Musterd (Eds.), Socio-economic segregation in European Capital cities: East meets West (pp. 313–332). Routledge.

Vasilevska, L., Vranic, P., Marinkovic, A. (2014). The effects of changes to the post-socialist urban planning framework on public open spaces in multi-story housing areas: A view from Nis, Serbia. Cities, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2013.10.004

Vilnius City Municipality (2015). RE-Block Žirmūnai triangle Local Action Plan, Vilnius. Retrieved May 24, 2020 from, https://urbact.eu/files/re-block-vilnius-action-plan

Wassenberg, F. (2018). Beyond an ugly appearance: Understanding the physical design and built environment of large housing estates. In D. Hess, T. Tammaru, & M. van Ham (Eds.), Housing Estates in Europe Poverty, Ethnic Segregation and Policy Challenges (pp. 35–55). Springer.

Wassenberg, F. (2013). Large Housing Estates: Ideas, Rise, Fall and Recovery: The Bijlmermeer and beyond. TUD doctoral thesis.

Watt, P., & Minton, A. (2016). London’s housing crisis and its activisms. City. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2016.1151707

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the EU COST Action Programme CA18137 MCMH – ‘Middle Class Mass Housing’; ERA.Net RUS Plus MOBERA14 – ‘Estates After Transition’; and the Estonian Research Council (Institutional Research grant number PUT PRG306) – ‘Understanding the Vicious Circles of Segregation. A Geographic Perspective’. The views expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. All interview data for this research was used with consent.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pirrus, J., Leetmaa, K. Public space as a medium for emerging governance networks in post-privatised large housing estates in Tartu and Vilnius. J Hous and the Built Environ 38, 17–37 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-021-09864-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-021-09864-7