Abstract

This article examines the trends and determinants of temporary movement of foreign workers (viz., mode 4 or movement of natural persons under trade ambits) into the United States (U.S.), with a special focus on the role of policy. The study makes use of an alternative dataset, i.e., a subset of the immigration statistics of the U.S., the other available proxies of mode 4 being unreliable. As revealed by the leading and growing share of high-skilled and preferential visa categories, the mode 4 admission in U.S. is significantly influenced by the policy factors than the actual market conditions. The augmented gravity equation validates the preferential policy of U.S. towards the neighboring countries and countries with bilateral trade arrangements. In category-wise regressions, with consistent negative effect of distance and positive effects of membership in North American Free Trade Agreement and Visa Waiver Program, we get stronger evidence for the policy prejudice. The positive network effect, which is declining due to the growingly strict temporary nature of mode 4 movements, and negative impact of the economic crisis in 2008 are the other major findings. Bringing out the insignificance of various push and pull forces like source country working-age population and unemployment levels in U.S., the findings clearly suggest that the structure of mode 4 admissions in U.S. is determined more by policy factors (trade barriers), than the economic factors. The study carries important implications for the trade negotiators from third world countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

WTO -World Trade Organisation, GATS-General Agreement on Trade in Services.

Though GATS have special provisions for protecting the trade interests of developing countries (Articles IV, X, XIX: 2 and XXV), a prominent area of their comparative advantage, i.e., mode 4, remains an unfinished business of globalization.

The term ‘temporary’ itself is not clearly stated while defining mode 4 under GATS and it generally varies between 3 months and 5 years. While Article I of the GATS deals with “presence of natural persons”, the Annex to the agreement deals with “movement of natural persons” supplying services. In Article I:2 (d), mode 4 is defined so vaguely as "the supply of a service by a service supplier of one member, through presence of natural persons of a member in the territory of any other member". The only clarification stated in the Annex is that GATS does not apply to measures affecting individuals seeking access to the employment market of a member nor to measures regarding citizenship, residence or employment on a permanent basis.

There is also a traditional notion in the gravity literature that the import data is better than the export data since the former will be more accurate, owing to the restrictions imposed (Baldwin & Taglioni, 2006).

If factor supplies are totally divergent between two countries, trade may not lead to complete convergence of factor prices and thus a reduction in migration incentives (Rotte & Vogler, 1998).

According to Winters et al. (2002), even casual observations reveal that factor-price equalization cannot occur in reality and the study lists a number of reasons for this.

Ethier tries to develop a theory of international trade and labour mobility, albeit only from the host- country perspective, by bringing in the relations between production, labour markets and international trade.

As Nayyar notes, during the second half of the twentieth century, there had been rapid liberalization of trade in goods along with removal of restrictions on the international movement of capital, whereas restrictions on the movement of labour only intensified. Hence, economists started assuming that determinants of international labour movements are mainly non-economic and hence did not attempt to analyse them, whereas they focused on the effects of migration.

Migration theories may however fail to capture some special features of mode 4 service suppliers, like their immobility between sectors or specificity of the task being performed, as different from the general labour migrants (WTO, 1998).

According to Francois and Hoekman (2009), since services are non-storable, their exchange generally requires proximity between the producer and the consumer and hence factors like distance lead to a transaction cost for service delivery. While technological developments can weaken the proximity burden for other modes of service delivery, this may not be closely applicable in the case of mode 4 movements. This is because, for labour movements, it is not only the physical distance that matters, but the related social and cultural inhibitions. Thus, as noticed by Helliwell (1997), there is a higher border effect for migration, compared to that for trade.

In line with Rotte and Vogler (1998), the present study considers all influences which may stimulate overall demand as pull factors and those which augment the overall supply as push factors.

The UN Population Division (2008) data, comparing between the age structure of India and U.S., clearly shows that the working age population is declining in U.S. since 2000, while it is steadily growing in India. As the Hindu (2012, 2013) reports, in line with the findings of the Economic Survey 2011–12, India will become the youngest country in the world by 2020, with 64% of its population in the working age group.

Foreign AffiliaTes Statistics.

The corresponding visa categories are given in parentheses.

Though there have been a number of attempts to quantify services trade barriers, using methods like frequency indices or other trade restrictiveness indices like price-based or quantity-based measures (Raychaudhuri & De, 2012), such indices are not independently meaningful, but useful only for comparative purposes (Francois & Hoekman, 2009). It is indeed almost impracticable to identify whether some domestic regulation measures are meant to achieve legitimate policy objectives than pure protectionism. Faced with this obscurity, Dihel and Shepherd (2007) point out that there is statistical uncertainty while using these indices for welfare calculations.

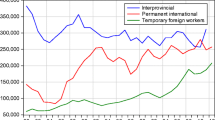

The temporary foreign workers helps in alleviating sectoral labour shortages, increases the flexibility of the labour market according to needs, and avoid the welfare costs associated with permanent immigration. However, a good proportion of temporary labour migration occurs among the OECD countries themselves, which is a pertinent point to note.

Calculations based on data from OECD Website and OECD (2010, 2011).

According to Pritchet (2007), in future, more than half of the U.S. job growth—about five million new jobs per year—will be low-skilled service jobs. Occupational projections from the Bureau of Labour Statistics (BLS) also reveal that the top 20 occupations, with the fastest employment growth in U.S. during 2002–2012, include mainly low skilled jobs like janitors, waiters, security guards, home health aides and truck drivers (Karoly & Panis, 2009). Such a growing demand for low skilled service workers in U.S. is not reflected in the composition of mode 4 admissions in U.S.

By ‘preferential’ or ‘bilateral’ visa categories or country partners, the study implies those related to FTAs, visa waiver programs, reciprocal exchange programs or some other form of specialised arrangements. To note, irrespective of the exact form of the bilateral relationship, the study concentrates on the fact that U.S. provides preferential access for service providers from certain countries, which tend to be partners in some bilateral/regional arrangements with U.S.

Being reserved for the NAFTA members, i.e., Canada and Mexico, there are many benefits accompanying the TN visa, like cost savings (no discriminatory types of fees, unlike the regular H1B visa), lesser time to issuance, lower eligibility requirements and no maximum stay limitations (Ganguly, 2005).

The selected countries together constitute 60% of total mode 4 admissions in U.S. in 2010.

Huge representation of Mexico in the less and medium-skilled segment of U.S. mode 4 market signifies obvious demand for such workers in U.S., though they remain relatively insignificant in total mode 4 entries. More importantly, it gets revealed that such categories, which are becoming increasingly prominent, are exclusively set aside for preferred nations or groupings.

The foreign artist or entertainer seeking a P2 visa needs neither to possess special skills nor to achieve domestic or international recognition. But, the conditions are that the foreign artists and/or entertainers traveling to the U.S. must be of similar caliber to the U.S. artists traveling abroad; the terms and conditions of employment for the foreign and the U.S. artists and/or entertainers participating in the exchange program must be similar and the number of entertainers/artists involved in the exchange must also be similar on both sides.

This is the simplest and most commonly used measure for distance between nations, among various measures followed (Baldwin & Taglioni, 2006).

Migration studies generally use the lagged migrant ‘stock’ for signifying network effects. However, just like Mayda (2007), we have used lagged migrant ‘flows’, as migration flows are highly correlated over time. Indeed, the present study focuses on the determinants and future prospects of the temporary ‘flows’ of workers.

However, as studies like Helliwell (1996) note, the variables of per capita incomes (a direct measure of economic situation) and relative unemployment rates are independently significant in econometric modeling.

All the economic and labour market variables are taken in ‘relative’ terms, to account for the disparities between the origin and the destination countries. Such relative indicators incorporate the push and the pull factors simultaneously.

According to Mayda (2007), a higher per worker GDP in the destination country does not necessarily mean better income opportunities (on average) for an immigrant worker, since this could also be due to a highly skilled labour force in the destination country’s population. To address this concern, she runs a robustness check where the average skill level is controlled. In similar vein, the incorporation of relative work participation rate in the present model may control for the changes in the per capita GDP due to variation in the skill/labour force supply.

Strictly exogenous variables are those independent variables whose (past, current and future) values are unaffected by the dependent variable and third factors in the error term. Although relative wage levels could be affected by immigration (due to its labour market effects), we do not expect any direct (immediate and explicit) impact of immigration on relative income levels in U.S. (i.e., the extent of global inequality). Though mode 4 movements are expected to result in net welfare gains for the world economy, there is no unanimity in the literature regarding the merits of trade liberalization (Copeland & Mattoo, 2008).

The Sargan test of whether over-identifying restrictions (where number of instruments are more than number of endogenous variables) are valid indicates whether the instruments as a group are exogenous (uncorrelated with the error term). Arellano and Bond developed a test for second-order autocorrelation in first differenced errors (AR (2) test), which, if present, can render some lags invalid as instruments. The presence of autocorrelation indicates that the lags of the dependent variable are in fact endogenous, and therefore are bad instruments.

However, according to Clark et al. (2004), the (lagged) immigrant ‘stock’ variable more or less attenuates the coefficients of other variables, since this variable has embedded in it the influence of previous economic and demographic fundamentals that are correlated with present fundamentals.

This finding is similar to that of Clark et al. (2004). That is, when the origin country is relatively unequal, an increase in its relative inequality will reduce the migration rate and when the source country is relatively equal an increase in its inequality will increase the migration rate.

In Mayda (2007), country-specific or fixed effects dummies are used to account for the heterogeneity of the sample, which results in varied (biased) estimates like this. However, under the dynamic panel estimation, such time-invariant dummies get eliminated with first-differencing.

The gravity analysis is performed for 35 top mode 4 sending countries into U.S. and for 5 years, i.e., 2006 to 2010. India and Guatemala were excluded from the list of countries covered under dynamic panel analysis, owing to data gaps. However, the remaining countries account for a significant portion (84%) of mode 4 admissions in U.S. and hence the conclusions can still be generalised.

Under migration studies (for e.g., Helliwell, 1997), per capita GDP is used for representing income levels, since it is more relevant than the aggregate GDP, which may get influenced by the country size. Moreover, as emphasized in migration theories, it is the ‘relative’ affluence (wage differences) rather than the ‘absolute’ income levels that matter, while capturing the economic incentive for migration.

Studies like Anderson and van Wincoop (2001) recommends accounting for third country (trade diversion) effects or country-specific heterogeneity, for theoretical consistency while applying gravity model. However, as mentioned in ‘ARTNeT Interactive Gravity Modelling Database Tutorial’, supplied under the aegis of Trade and Investment Division of UNESCAP (Draft Version 1.0), including such country/pair-specific dummies is not only optional, but also prevents capturing partner-specific characteristics like distance and language in the model (due to perfect collinearity with dummies). The issue has been mentioned in studies like Baldwin and Taglioni (2006), Eicher et al. (2008) and Ortega and Peri (2009). In the present study, gravity results emerged consistent with dynamic panel results, where unobserved country-specific effects were effectively controlled. To add, our cross-section regressions showed robust standard errors, addressing the heteroscedasticity problem.

According to Winters (2008), temporary migrants may be less effective in building up foreign networks or perpetuating the network effect, compared to the permanent ones. Still, as Winters notes, the spill-over effect of temporary migration is a matter that needs to be empirically assessed.

It is also possible that shortages exist in specific sectors or occupations, despite general unemployment in the economy (IOM/World Bank/WTO 2004).

According to Harris and Mátyás (1998), the introduction of dynamics may wipe out the significance of most structural parameters of gravity equations; but they also emphasise that exports are strongly autoregressive. In the present study too, it is due to the possible significant role of immigrant networks in influencing the mode 4 flows that we use the dynamic version of the model.

(Exponential of 0.4)– 1 = 0.49 (i.e., 49%), as per the formula mentioned in studies like Shepherd (2012).

It was revealed from Sect. 3 that Mexico and Canada are the topmost countries sending mode 4 workers into U.S. Moreover, the ‘TN’ visa category, meant for NAFTA professional workers, is fast emerging as a prominent category of mode 4 admissions in U.S.

The significant positive co-efficient of network/‘friends and family’ effect is in conformity with the migration literature. As Chiswick and Hatton (2002) note, this variable turned out to be the single most important determinant of immigration flows in certain studies.

For J1 visa, there is a small rise in the role of immigrant networks, which could be due to the market information received from previous participants of the exchange-visitor program.

Under source-country working age population, highly significant positive co-efficients are noticed for H2B and J1 categories, both of which are supplied largely by OECD members like Mexico and Canada.

Since this finding could be due to the non-inclusion of India, who leads in the supply of H1B workers, in the sample, we analysed the determinants of H1B admissions by including India and Guatemala (and removing the variable of unemployment, due to continuous non-availability of data). But it was revealed that our conclusions are only corroborated, than contradicted (See Table 8 in appendix).

While Canada and Mexico can obtain a highly liberal bilateral visa, viz., TN, for their professional workers, countries like India struggle to obtain the H1B visas, which is subject to an annual quota of 65,000 world-wide.

It was evident from Sect. 3 that Mexico accounts for almost one-third of B1 admissions and more than two-thirds of H2B admissions in 2010.

The U.S. annually publishes a list of countries from which the H2B workers are received, and about half of them are VWP members.

China is considered as a developing country, though Hong Kong is a newly industrialized Asian economy. While information on independent variables is collected only for People’s Republic of China (owing to data gaps), for the dependent variable, China covers People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong and Macau. Similar are the cases of Australia, Denmark, France, Netherlands, New Zealand and U.K.

References

Anderson, K. & van Wincoop, E. (2001). Gravity with Gravitas: A Solution to the Border Puzzle. NBER Working Paper No 8079, January, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. The Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277–297.

Baldwin, R. & Taglioni, D. (2006). Gravity for Dummies and Dummies for Gravity Equations. NBER Working Paper 12516, September, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Baltagi, B. H. (2005). Econometric analysis of panel data. John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87(1), 115–143.

Chanda, R. (1999). Movement of natural Persons and Trade in Services: Liberalising Temporary Movement of Labour under the GATS. Working Paper No 51, November, Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations.

Chiswick, B. R. & Hatton, T. J. (2002). International Migration and the Integration of Labour Markets. IZA Discussion Paper No 559, August, Institute for the Study of Labor.

Clark, X., Hatton, T. J. & Williamson, J. G. (2004). Explaining U.S. Immigration 1971–98. Policy Research Working Paper No 3252, March, World Bank.

Clemens, M. (2010). A Labor Mobility Agenda for Development. CGD Working Paper No 201, January, Center for Global Development.

Copeland, B., & Mattoo, A. (2008). The basic economics of services trade. In A. Mattoo, R. Stern, & G. Zanini (Eds.), A Handbook of international trade in services (pp. 84–129). Oxford University Press Inc.

Deardorff, A. V. (2001). International Provision of Trade Services, Trade and Fragmentation. Policy Research Working Paper No 2548, February, World Bank.

Dihel, N. & Shepherd, B. (2007). Modal Estimates of Services Barriers. OECD Trade Policy Working Paper No 51, April, OECD publishing.

Eicher, T., Henn, C. & Papageorgiou, C. (2008). Trade Creation and Diversion Revisited: Accounting for Model Uncertainty and Natural Trading Partner Effects. IMF Working Paper No WP/08/66, March, European Department.

Ethier, W. J. (1985). International trade and labour migration. The American Economic Review, 75(4), 691–707.

Francois, J. & Hoekman, B. (2009). Services Trade and Policy. Wiiw Working Paper No 60, December, The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies, Vienna.

Frankel, J. A., Stein, E., & Wei, S. J. (1998). Continental trading blocs: Are they natural and supernatural? In J. A. Frankel (Ed.), The Regionalization of the world economy (pp. 91–120). University of Chicago Press.

Ganguly, D. (2005). Barriers to Movement of Natural Persons: A Study of Federal, State, and Sector-specific Restrictions to Mode 4 in the United States of America. Working paper No 169, September, Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations.

Harris, M. N. & Mátyás, L. (1998). The Econometrics of Gravity Models. Working Paper No 5/98, February, Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, The University of Melbourne.

Hatton, T. J. & Williamson, J. G. (2009). Vanishing Third World Emigrants? NBER Working Paper No 14785, March, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Head, K. (2000). Gravity for Beginners. Material presented at Rethinking the Line: The Canada-U.S. Border Conference, Vancouver, British Columbia, 22 October.

Helliwell, J. F. (1996). Convergence and migration among canadian provinces. Canadian Journal of Economics, 29, S324–S330.

Helliwell, J. F. (1997). National Borders, Trade and Migration. NBER Working Paper No 6027, May, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Hugo, G. J. (1981). Village-community ties, village norms, and ethnic and social networks: A review of evidence from the third world. In G. F. Dejong & R. W. Gardner (Eds.), Migration decision making: Multidisciplinary approaches to micro level studies in developed and developing countries (pp. 186–225). Pergamon Press.

IOM/World Bank/WTO. (2004). Background Paper. Prepared for Trade and Migration Seminar, Geneva, 4–5 October.

Jansen, M. & Piermartini, R. (2005). The Impact of Mode 4 Liberalization on Bilateral Trade Flows. Staff Working Paper No ERSD-2005-06, November, Economic Research and Statistics Division, World Trade Organization.

Karemera, D., Oguledo, V. I., & Davis, B. (2000). A Gravity model analysis of international migration to North America. Applied Economics, 32(13), 1745–1755.

Karoly, L. A., & Panis, C. W. A. (2009). Supply of and demand for skilled labor in the United States. In J. Bhagwati & G. Hanson (Eds.), Skilled immigration today: Prospects, problems and policies (pp. 15–52). Oxford University Press.

Krugman, P. (1991). The Move toward Free Trade Zones. Presented at Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Symposium on Policy Implications of Trade and Currency Zones, Jackson Hole, Wyoming, 22–24 August.

McGuire, G. (2002). Trade in services: Market access opportunities and the benefits of liberalization for developing economies. UNCTAD Study Series on Policy Issues in International Trade and Commodities No 19, UNCTAD/ITCD/TAB/20, United Nations.

Markusen, J. R. (1983). Factor movements and commodity trade as complements. Journal of International Economics, 14(3–4), 341–356.

Martínez-Zarzoso, I. & Horsewood, N. (2005). Regional Trading Agreements: Dynamic Panel Data Evidence from the Gravity Model. September, viewed on 23 May 2014 (http://www.etsg.org/ETSG2005/papers/inma.pdf)

Massey, D. S., Arango, J., Hugo, G., Kouaouci, A., Pellegrino, A., & Taylor, J. E. (1993). Theories of international migration: A review and appraisal. Population and Development Review, 19(3), 431–466.

Mayda, A. M. (2007). International Migration: A Panel Data Analysis of the Determinants of Bilateral Flows. CReAM Discussion Paper No 07/07, April, Centre for Research and Analysis of Migration.

Mitchell, J. & Pain, N. (2003). The Determinants of International Migration into the UK: A Panel Based Modelling Approach. NIESR Discussion Paper No 216, May, National Institute of Economic and Social Research.

Nayyar, D. (2000a). Globalisation and migration: Retrospect and prospect. Yojana, 44(5), 18–27.

Nayyar, D. (2000b). Cross Border Movements of People. Working Paper No 194, August, United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research.

Nielson, J. & Cattaneo, O. (2002). Current Regimes for Temporary Movement of Service Providers-Case study: the United States of America. Joint WTO-World Bank Symposium on Movement of Natural Persons (Mode 4) under the GATS, 11–12 April.

OECD. (2002). International Migration Outlook, SOPEMI. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Office of Immigration Statistics (2011). Yearbook of Immigration Statistics. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

Ortega, F. & Peri, G. (2009). The Causes and Effects of International Migrations: Evidence from OECD Countries 1980–2005. NBER Working Paper No 14833, April, National Bureau of Economic research.

Pritchett, L. (2007). Bilateral Guest Worker Agreements: A Win-Win Solution for Rich Countries and Poor People in the Developing World. CGD Brief, March, Center for Global Development.

Raychaudhuri, A., & De, P. (2012). International trade in services in India: Implications for growth and inequality in a globalizing world. Oxford University Press.

Rotte, R. & Vogler, M. (1998). Determinants of International Migration: Empirical Evidence for Migration from Developing Countries to German. IZA Discussion Paper No 12, June, Institute for the Study of Labor.

Shepherd, B. (2012). The gravity model of international trade: A user guide. United Nations Publications.

Summers, L. (1991). Regionalism and the World Trading System. In Policy Implications of Trade and Currency Zones, A Symposium Sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City (pp. 295–302). Jackson Hole, Wyoming: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

The Hindu. (2012). India to Be a Youngest Nation by 2020. 16 March.

The Hindu. (2013). India is set to Become the Youngest Country by 2020. 17 April.

UNCTAD. (1999). Assessment of Trade in Services of Developing Countries: Summary of Findings. Background note by the UNCTAD secretariat, UNCTAD/ITCD/TSB/7, 26 August, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

UN Population Division. (2008). World Population Prospects: The 2008 Revision Population Database. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations. Retrieved February 02, 2010 from http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/database/index.shtm

Winters, L. A. (2008). The temporary movement of workers to provide services (GATS Mode 4). In A. Mattoo, R. Stern, & G. Zanini (Eds.), A Handbook of international trade in services (pp. 480–541). Oxford University Press Inc.

Winters, L. A., Walmsley, T. L., Wang, Z. K. & Grynberg, R. (2002). Negotiating the Liberalisation of the Temporary Movement of Natural Persons. Discussion Papers in Economics No 87, October, University of Sussex.

Wonnacott, P. & Lutz, M. (1989). Is there a case for free trade areas? In J. Schott (Ed.), Free trade areas and U.S. trade policy (pp. 59–84). Institute for International Economics.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2002). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT Press.

WTO. (1998). Presence of Natural persons (Mode 4): Background Note by the Secretariat. S/C/W/75, 8 December, World Trade Organisation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Countries included in regression analysis

1.1.1 Developed Countries

Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Singapore, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and U.K.

1.2 Developing Countries

Argentina, Brazil, Chile, China,Footnote 52 Columbia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Guatemala, India, Jamaica, Mexico, Peru, Philippines, Russia, South Africa, Turkey, and Venezuela.

1.3 OECD Countries

Those listed as developed countries, plus Chile, Mexico and Turkey, but without Singapore.

1.4 Members of U.S. visa waiver program included in regression analysis

Australia, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Singapore, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, U.K.

About this article

Cite this article

Karayil, S.B. Movement of natural persons and the sieve of immigration policy: Evidence from United States. Rev World Econ 157, 853–879 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-021-00419-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-021-00419-0