Abstract

Evaluating the exact first derivative of a feedforward neural network (FFNN) output with respect to the input feature is pivotal for performing the sensitivity analysis of the trained neural network with respect to the inputs. In this paper, a novel method is presented that computes the analytical quality first derivative of a trained feedforward neural network output with respect to the input features without the need for backpropagation. To this end, the complex step derivative approximation is illustrated, and its implementation in the framework of the feedforward neural network is described. Artificial datasets are generated, and the efficacy of the proposed method for both regression and classification tasks is demonstrated. The results obtained for the regression task indicated that the proposed method is capable of obtaining analytical quality derivatives, and in the case of the classification task, the least relevant features could be identified.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multilayer feedforward neural networks (FFNN) are parameterized nonlinear models that approximate a mathematical mapping between the input features and the output target variables [1]. Although FFNNs are known to possess the potential for approximating various functions [2, 3], they are often treated as black-box models because of the complexity involved in generating the closed-form expression of the learned function. Sensitivity analysis can be performed to understand the relationship and influence of each input on the output of a problem [4,5,6,7]. Sensitivity analysis is performed by examining the change in the target output when one of the input features is perturbed. In other words, performing sensitivity analysis involves the computation of partial derivatives of the outputs with respect to the inputs. While a larger magnitude of partial derivative suggests a drastic change in output with a small variation in the input, a smaller magnitude of partial derivative suggests smaller sensitivity of the output to the input [4].

In FFNNs the first derivative (i.e., \(\frac{\partial y}{\partial {x}_{k}}\)) of the output \(y\) with respect to the \({k}^{th}\) input \({x}_{k}\) is evaluated employing the backpropagation algorithm, which involves the application of derivative chain rule [8,9,10,11]. Application of chain rule in this context is similar to the one employed during the training of an FFNN where \(\frac{\partial E}{\partial {w}_{ij}}\) is evaluated for backpropagating the error with respect to the parametric weights \({w}_{ij}\) of the network [12,13,14,15]. The goal of this work is to evaluate the derivatives of the FFNN outputs with respect to the inputs without the need for backpropagation employing numerical differentiation techniques.

Finite difference schemes are employed for evaluating numerical derivatives [16,17,18]. In finite difference schemes, the input features are perturbed one at a time (e.g. \({x}_{k}\)) with a finite step size (\(h)\) and the change in the output of a trained FFNN is obtained. Popularly employed finite difference schemes include finite difference approximation (FDA) (see Eq. 1) and central finite difference approximation (CFDA) (see Eq. 2) methods, which are given as follows.

Finite difference approximation (FDA)

Central finite difference (CFDA)

where \({\varvec{x}}=({x}_{1}, {x}_{2},\ldots {x}_{k},\ldots {x}_{q})^{\prime}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{q\times 1}\) are the inputs, \(q\) is the number of inputs, \(f(.)\) is the function mapping the inputs to the output variable and, \({f}^{\prime}\left(.\right)\) is the first partial derivative approximation of \(f(.)\) with respect to the input \({x}_{k}\). However, finite difference schemes are prone to subtractive cancellation errors [19, 20]. Subtractive cancellation errors are caused by subtracting two close numbers whose difference could be in the order of the precision of the calculations. This scenario is inevitable in the case of finite difference schemes due to the subtractive operation as seen in the numerators of Eq. 1 and Eq. 2 and the use of very low \(h\) values to lower the truncation errors [19]. With this, an additional computational step to evaluate the ideal \(h\) value to minimize the truncation error without increasing the subtractive cancellation error is necessary when finite difference schemes are evaluated. A novel differentiation scheme is necessary to avoid this additional step and to achieve analytical quality derivatives by minimizing both truncation and subtractive cancellation errors.

In this study, a novel method for determining the analytical quality first derivative of feedforward neural network outputs is proposed and implemented. To this end, the concept of complex-step derivative approximation (CSDA) is described, and its ability to circumventing the subtractive cancellation errors associated with other numerical differentiation techniques is illustrated in "Complex-step derivative approximation (CSDA)" section. Implementing CSDA in the framework of FFNN for regression and classification tasks is demonstrated in "Implementation of CSDA in feed-forward neural networks" section, and future areas of improvement are mentioned in "Summary and future work" section.

Complex-step derivative approximation (CSDA)

CSDA is a numerical differentiation technique proposed by Lyness and Moler [21]. CSDA was successfully implemented in various fields of engineering, including aerospace [22,23,24,25], computational mechanics [26,27,28], estimation theory (e.g., second-order Kalman filter) [29], etc., for performing sensitivity analysis and evaluating the first-order derivatives. In this section, the mathematical description of CSDA to estimate analytical quality first-order derivative of a single scalar variable scalar function is provided [30].

Let \(f\) be an analytic function of a complex variable \(z\). Also, assume that \(f\) is real on the real axis. Then \(f\) has a complex Taylor series expansion which is expressed as

where, \(h\) is the step size and \({i}^{2}=-1\). By taking the imaginary component of \(f\left(x+ih\right)\), dividing it by the step size and truncating the higher-order terms in the Taylor series, the CSDA for the first derivative can be expressed as

where Imag (*) denotes the imaginary component and \(\mathcal{O}({h}^{2})\) is the second-order truncation error. It is interesting to note that there are no subtractive operations in Eq. 4, which are inevitable in the finite difference approximations (see Eq. 1 and Eq. 2). The absence of subtractive operations in the numerator ensures that the CSDA is not prone to subtractive cancellation errors. Hence, a very small value of \(h\) can be chosen in order to eliminate the truncation errors without the fear of subtractive cancellation errors. A simple example is provided next, which illustrates the accuracy of CSDA over finite difference schemes.

Illustrative example

Consider a smooth function \(f(x)\) provided in Eq. 5. The exact first-order derivative of the function computed at \(x=\frac{\pi }{4}\) is given as 2.65580797029498.

The numerical first-order derivative of the above function is evaluated using all three approximation methods, namely, finite difference approximation (Eq. 1), central finite difference approximation (Eq. 2), and CSDA (Eq. 4). The step size \(h\) employed for the purpose of computation ranged from \({10}^{-1}\) to \({10}^{-16}\). The absolute error \((\varepsilon\)) for each step size is then evaluated using Eq. 6, and the results are shown in Fig. 1.

Illustration of the subtractive cancellation errors in finite difference methods and the CSDA. Both FDA and CFDA suffer from subtractive cancellation errors unlike CSDA. The truncation errors in CSDA can be minimized by choosing a very low \(h\) value. (CSDA: Complex-Step Derivative Approximation; FDA: Finite Difference, and CFDA: Central Finite Difference Approximation)

where \(\widehat{{f}^{\prime}\left(x\right)}\) is the approximate first derivative at \(x=\frac{\pi }{4}\) for a chosen step size \(h\) and, \({f}^{\prime}\left(x\right)\) is the exact first derivative of function \(f(x)\) at \(x=\frac{\pi }{4}\).

From Fig. 1, it can be noticed that the absolute error decreased initially for both FDA and CFDA with the reduction in the step size. However, for step sizes less than \(h={10}^{-8}\) for FDA and \(h={10}^{-5}\) for CFDA, the absolute error was found to increase. The increase in the absolute error after a certain step size can be attributed to the subtractive operation in the numerator of finite difference schemes. On the contrary, in the case of CSDA, the absolute error was not only found to decline with a reduction in step size but approached a double float precision (~ \({10}^{-16}\)) with a further decrease in the step size beyond \(h={10}^{-7}\). In other words, no subtractive cancellation errors were observed, and hence analytical quality derivatives with errors reaching the precision employed were obtained.

Implementation of CSDA in feed-forward neural networks

Obtaining a closed-form expression in feedforward neural networks (FFNN) is not only challenging but also a tedious task. Nevertheless, CSDA can be implemented in the framework of the feedforward neural network (FFNN) for evaluating the variation of the output variable \(y\in {\mathbb{R}}\) with respect to the change in an input \({x}_{k}\in {\mathbb{R}}\), where the subscript \(k\) represents the \({k}^{th}\) input. The extended form of CSDA (see Eq. 4) applied to a multivariate function can be expressed as

where \({\varvec{x}}=({x}_{1}, {x}_{2},{x}_{k},{x}_{q})^{\prime}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{q\times 1}\) are the input features, \(q\) is the number of input features, \(f(.)\) is the function mapping the input features to the output target variable and, \({f}^{\prime}\left(.\right)\) is the first-order derivative approximation of \(f(.)\) with respect to the input feature \({x}_{k}\).

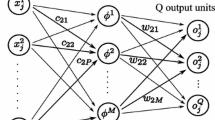

Implementation of CSDA in FFNN involves three steps (see Fig. 2): (1) configure and train the FFNN for a given dataset, (2) perturb the input feature \({x}_{k}\) one at a time (see Eq. 7) with an imaginary step size of \(ih\) (\({\text{where}}\, h\ll {10}^{-8}\)) and perform the feedforward operation on the trained FFNN and (3) obtain the output neuron's imaginary component with respect to the perturbed input and divide this component with the step size \((h)\). Configuring the FFNN is a trial-and-error process that involves finding the appropriate number of neurons and hidden layers in a network. A network is said to be configured when it is capable of learning an approximate mathematical mapping between the input features and the associated target variable such that it could be generalized to the unseen data instances. Guidelines for choosing trial configurations of FFNN can be found elsewhere [31]. For training the feedforward neural network, the backpropagation algorithm, in conjunction with the Levenberg–Marquardt optimization technique, is employed in this study [32]. Note that the code for implementing the CSDA in FFNN was written and executed in the MATLAB® environment.

Illustrative example

For illustrating the effectiveness of the CSDA in computing the first order derivative of FFNN, a single variable function (see Eq. 8) commonly employed in CSDA literature is chosen. A single hidden layer with 100 neurons is configured to train the FFNN and the first order derivative is obtained at \(x=\frac{\pi }{4}\) for step size of \(h={10}^{-15}\). Both FDA and CFDA are also employed on the same trained FFNN and first order derivative is obtained for same step size. The results along with the exact solution is provided in Table 1. From the Table 1 it is evident that the proposed methods result in least error (i.e., 2.9e−5) when compared to existing methods FDA (i.e., 0.145) and CFDA (i.e., 2.2e−3).

Furthermore the derivatives are evaluated for all the \(x\) values using CSDA, FDA and CFDA and is provided in Fig. 3. Comparison of exact solution and the first order derivatives evaluated using CSDA, FDA and CFDA. From Fig. 3 it can inferred that the proposed CSDA method predicts the analytical quality derivative that coincides with the exact solution. However in the case of FDA and CFDA the derivatives are found to be inaccurate due to subtractive cancellation errors.

In what follows, the implementation of CSDA is demonstrated for regression and classification tasks using artificial datasets consisting of more than one variable.

Regression

The process of generating artificial datasets (from a known analytic function) for performing regression is described in this subsection. The first-order derivative results are then obtained from the CSDA implemented FFNN (see Eq. 7) and are compared with the exact analytical derivatives of the known function.

Datasets and FFNN Configurations

Three different single scalar-valued functions are employed in this study to generate artificial datasets for the regression task (see Table 2). While the first two functions \({R}_{1}, {R}_{2}\) have 3 input features \({x}_{1}, {x}_{2}\, {\text{and}}\, {x}_{3}\), the third function \({R}_{3}\) is chosen to have 4 input features \({x}_{1}, {x}_{2}, {x}_{3}\, {\text{and}}\, {x}_{4}\), wherein the feature \({x}_{4}\) represents the uniformly distributed random noise added to the function \({R}_{2}\). Since the added noise \({x}_{4}\) has no significant contribution in evaluating the output of the function \({R}_{3}\), the mean of the first-order derivative with respect to \({x}_{4}\) computed using CSDA would be expected to be zero. In other words, the purpose of adding noise is to verify the proposed method’s ability to identify the least relevant feature. The input features employed in the dataset are real-valued and are independent of each other. In total, 2000 instances are randomly generated for each dataset from a uniform distribution of the feature values. The range of the values chosen for each input feature for all three datasets is summarized in Table 3. These randomly generated input features are then substituted in the respective functions \({R}_{1},{R}_{2}\text{ and} {R}_{3}\) to obtain the associated target variables \(y\) for each dataset.

For obtaining a suitable FFNN configuration for each dataset, numerous trial configurations with varying numbers of neurons and hidden layers were examined beforehand. The trial configuration that resulted in a mean squared error (MSE) less than 1e−6 on the validation dataset is chosen as the suitable configuration for training the datasets. The final configuration of FFNN that was adapted to train dataset 1 is 1st hidden layer (HL) (8 neurons)—2nd HL (5 neurons); dataset 2 is 1st HL (10 neurons)—2nd HL (5 neurons); and dataset 3 is 1st HL (10 neurons)—2nd HL (5 neurons). Note that a soft plus function (see Fig. 4a) (\(\mathrm{ln}(1+\mathrm{exp}(\Sigma ))\), where, \(\Sigma\) is the net input function of a neuron) is used as an activation function for all the neurons in the hidden layers. The MSE of trained FFNN associated with dataset 1, dataset 2, and dataset 3 are determined to be 8.2e−7, 5.6e−8, and 4.3e−7, respectively.

Comparison of CSDA-FFNN output and the exact analytical derivative

CSDA is implemented on the trained FFNNs to evaluate the change in the predicted output variable \(\widehat{y}\) with respect to the input feature \({x}_{j}\) where \(j=1, 2,\, {\text{and}}\, 3\) for dataset 1 and dataset 2; and \(j=1, 2, 3,\text{ and} 4\) for dataset 3. Note that in CSDA implemented FFNN, the predicted output (\(\widehat{y}\)) is a complex variable. According to Eq. 7, only the imaginary component of \(\widehat{y}\) is required for obtaining the first-order derivative. More precisely, if \({g}_{1}, {g}_{2}\) and \({g}_{3}\) indicates the approximate function (mapping \({\varvec{x}}\) to \(\widehat{y}\)) learned by FFNN for dataset \(\mathrm{1,2}\) and \(3\), respectively, then the first-order derivative of \({g}_{1}, {g}_{2}\) and \({g}_{3}\) with respect to the feature \({x}_{j}\) are computed as

where, \(q=3\) for dataset 1 and dataset 2, and \(q= 4\) for dataset 3. Since there are 2000 instances in each dataset, the number of first-order derivatives evaluated with respect to each feature \({x}_{j}\) is also 2000. The comparison between the first-order derivative evaluated (for all 2000 instances) using CSDA implemented FFNN, and the exact analytical derivatives are provided in Figs. 5 and 6. From Fig. 5, it is evident that the derivatives of the approximation function \({g}_{1}\) (for dataset 1) evaluated with respect to features \({x}_{1}, {x}_{2}\, {\text{and}}\, {x}_{3}\) using CSDA are in good agreement with the exact analytical derivatives \(\frac{\partial {R}_{1}}{\partial {x}_{1}}, \frac{\partial {R}_{1}}{\partial {x}_{2}}\) and \(\frac{\partial {R}_{1}}{\partial {x}_{3}}\), respectively. Among all the data points for features \({x}_{1}, {x}_{2} \,{\text{and}}\, {x}_{3}\), the maximum absolute error (\(\varepsilon\)) (see Eq. 6) was found to occur at \({x}_{1}=1, {x}_{2}=0.006074\, {\text{and}}\, {x}_{3}=-1\). Similarly, from Fig. 6 (a)-(c), it is evident that the derivatives of the approximation function \({g}_{2}\) evaluated with respect to \({x}_{1}, {x}_{2},\, {\text{and}}\, {x}_{3}\) using CSDA are also in good agreement with the exact analytical derivatives \(\frac{\partial {R}_{2}}{\partial {x}_{1}}, \frac{\partial {R}_{2}}{\partial {x}_{2}}\) and \(\frac{\partial {R}_{2}}{\partial {x}_{3}}\). Among all the data points for features \({x}_{1}, {x}_{2}\, {\text{and}}\, {x}_{3}\), the maximum absolute error (\(\varepsilon\)) was found to occur at \({x}_{1}=0.9855, {x}_{2}=1 \,{\text{and}}\, {x}_{3}=0.0005\) As mentioned earlier, in the case of function \({R}_{3}\) (see Fig. 6d) where the input feature \({x}_{4}\) is least relevant, the first derivative with respect to all values of \({x}_{4}\) are found to be scattered above and below the exact analytical derivative which is zero.

Classification

Unlike the regression task, evaluating the derivatives in the case of the classification task may not be feasible since the output of the FFNN is discrete (e.g., SoftMax activation function outputs). However, considering the fact that the inputs fed to the SoftMax activation neurons in the output layer are not discrete, the first-order derivatives of such inputs could still be evaluated. These first-order derivatives will aid in providing information about the importance of the input features. In this subsection, the process of generating an artificial dataset for demonstrating the implementation of CSDA for classification tasks is described, and its significance in determining the top features is illustrated.

Dataset and CSDA implementation

A binary class artificial dataset with input features \({x}_{1}, {x}_{2}\) and \({x}_{3}\) is generated such that all the instances belonging to class label 1 are enclosed within a cylinder of unit radius, and the rest of the instances belonging to class label 2 are outside the cylinder (see Fig. 7). In total, 1000 instances are generated for each class label. Note that the feature \({x}_{3}\) is randomly chosen from a uniformly distributed noise with a zero mean, which has the least relevance in determining the class label. The purpose of including feature \({x}_{3}\) is to demonstrate that the proposed approach has the ability to identify the least significant features. The parametric equations used to generate the datasets are.

where \({r}_{1}\sim U\left(0, 1\right)\) and \({\theta }_{1}\sim U\left(0, 2\pi \right)\)

where \({r}_{2}\sim U\left(1, 2\right)\) and \({\theta }_{2}\sim U\left(0, 2\pi \right)\)

It is important to note that all three input features are independent of one another. Similar to the regression task, numerous trail configurations with a varying number of neurons and hidden layers were examined beforehand to obtain a suitable FFNN configuration, i.e., a configuration that has prediction accuracy > 98%. The configuration of FFNN that was chosen to train the dataset is 1st HL (8 neurons)—2nd HL (5 neurons). Note that Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) (see Fig. 4(b)) (\(\mathrm{max}(0,\Sigma )\), where \(\Sigma\) is the net input function for a neuron) is used as an activation for all the neurons in the hidden layers and SoftMax function is used as an activation function for the neurons in the output layer.

The first derivative of the two net input functions in the output layer (i.e. \({\Sigma }_{{o}_{1}}\) and \({\Sigma }_{{o}_{2}}\)) in FFNN with respect to input features \({x}_{1}, {x}_{2}\) and \({x}_{3}\) are obtained for all the data points using CSDA, and the sum of their absolute values (i.e., the sum of all 2000 data points) are provided in Table 4. Considering that the first derivative (i.e. \(\frac{\partial {\Sigma }_{{o}_{m}}}{\partial {x}_{j}}\)) with respect to each input feature \({x}_{j}\) represents the proxy measure of its significance, the least relevant feature can be determined. In other words, the input feature that results in the lowest magnitude of the first derivative will be considered as the least relevant feature. From Table 4, it can be observed that the input feature \({x}_{3}\) has the lowest magnitude when compared to features \({x}_{1}\) and \({x}_{2}\). Therefore feature \({x}_{3}\) can be said to be the least relevant feature. In order to verify if the feature \({x}_{3}\) is irrelevant, the FFNN is trained again with the exclusion of feature \({x}_{3}\) and the confusion matrix is shown in Table 5. From the confusion matrix, it is evident that the exclusion of feature \({x}_{3}\) does not influence the accuracy of classification. Furthermore the precision and recall were also determined i.e., 0.99 and 0.98 respectively, and were noticed to be uninfluenced by the exclusion of feature \({x}_{3}\).

Summary and future work

In this study, a novel method is proposed to compute the analytical quality first derivative of the FFNN output with respect to the input features. The major drawback of popularly used finite difference approximation schemes is highlighted, and the concept of CSDA is introduced in the context of neural network differentiation. The significance of CSDA in circumventing subtractive cancellation errors is then illustrated using a simple example wherein analytical quality first derivative was obtained along with a normalized relative error approaching the double float precision. A step-by-step procedure involved in extending CSDA to FFNN is provided, and its implementation in regression and classification tasks is demonstrated by employing artificial datasets generated from known functions. FFNN’s are configured and trained using the trial-and-error process for all the artificial datasets. The first derivative results that are obtained from the CSDA implemented FFNN output for the regression task was found to be in good comparison with the exact analytical derivatives of the known function. Owing to the discrete output in the classification task, the CSDA was used only to obtain the derivatives of net input function in the output neurons, and the least relevant features are identified. Note that the advantage of the proposed method is that it evaluates the derivative only in one feedforward operation and does not require the evaluation of derivatives used in the backpropagation. Hence, the derivatives can be obtained even after the neural networks are deployed for specific applications.

It is important to note that feed-forward neural network was trained with the artificially generated data to learn these analytical functions so that the first-order derivatives could be verified. Standard regression/classification datasets were not included in this study since the closed form expression of the function that maps the input variables to the target output is unknown in feed-forward neural networks which may make it difficult to verify the analytical quality derivative. However, the authors are currently working on implementing the proposed method on standard datasets. Furthermore, in the future work, the authors intend to extend the proposed method to the multiple output regression problems and investigate the influence of different activation functions. In addition, the derivatives evaluated using the proposed method will be employed to perform feature selection on real datasets and validate using the currently available methods.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Zhang Z, Beck MW, Winkler DA, Huang B, Sibanda W, Goyal H. Opening the black box of neural networks: methods for interpreting neural network models in clinical applications. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6:216–216. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2018.05.32.

Hornik K, Stinchcombe M, White H. Multilayer feedforward networks are universal approximators. Neural Netw. 1989;2:359–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/0893-6080(89)90020-8.

Takahashi Y. Generalization and approximation capabilities of multilayer networks. Neural Comput. 1993;5:132–9. https://doi.org/10.1162/neco.1993.5.1.132.

Nourani V, Sayyah FM. Sensitivity analysis of the artificial neural network outputs in simulation of the evaporation process at different climatologic regimes. Adv Eng Softw. 2012;47:127–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advengsoft.2011.12.014.

Cao M, Alkayem NF, Pan L, Novák D. Advanced methods in neural networks-based sensitivity analysis with their applications in civil engineering. Artif Neural Netw Model Appl. 2016. https://doi.org/10.5772/64026.

Kowalski PA, Kusy M. Sensitivity analysis for probabilistic neural network structure reduction. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2018;29:1919–32. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2017.2688482.

Cortez P, Embrechts MJ. Using sensitivity analysis and visualization techniques to open black box data mining models. Inf Sci (Ny). 2013;225:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2012.10.039.

Engelbrecht AP, Cloete I. Sensitivity analysis algorithm for pruning feedforward neural networks. IEEE Int. Conf. Neural Networks - Conf. Proc., vol. 2, IEEE; 1996, p. 1274–8. https://doi.org/10.1109/icnn.1996.549081.

Nguyen-Thien T, Tran-Cong T. Approximation of functions and their derivatives: a neural network implementation with applications. Appl Math Model. 1999;23:687–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0307-904X(99)00006-2.

Hornik K, Stinchcombe M, White H. Universal approximation of an unknown mapping and its derivatives using multilayer feedforward networks. Neural Netw. 1990;3:551–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/0893-6080(90)90005-6.

Hashem S. Sensitivity analysis for feedforward artificial neural networks with differentiable activation functions, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE); 2003, p. 419–24. https://doi.org/10.1109/ijcnn.1992.287175.

Christopher MB. Neural networks for pattern recognition. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1995.

Ruck DW, Rogers SK, Kabrisky M. Feature selection using a multilayer perceptron. J Neural Netw Comput. 1990;2:48–8.

Bo L, Wang L, Jiao L. Multi-layer perceptrons with embedded feature selection with application in cancer classification. Chin J Electron. 2006;15:832–5.

Gasca E, Sánchez JS, Alonso R. Eliminating redundancy and irrelevance using a new MLP-based feature selection method. Pattern Recognit. 2006;39:313–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2005.09.002.

Montaño JJ, Palmer A. Numeric sensitivity analysis applied to feedforward neural networks. Neural Comput Appl. 2003;12:119–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-003-0377-9.

Güne¸ A, Baydin G, Pearlmutter BA, Siskind JM. Automatic differentiation in machine learning: a survey. J Mach Learn Res. 2018;18.

Jerrell ME. Automatic differentiation and interval arithmetic for estimation of disequilibrium models. Comput Econ. 1997;10:295–316. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008633613243.

Driscoll TA, Braun RJ. Fundamentals of Numerical Computation. 2017.

Boudjemaa R, Cox MG, Forbes AB, Harris PM. Report to the National Measurement Directorate, Department of Trade and Industry From the Software Support for Metrology Programme Automatic Differentiation Techniques and their Application in Metrology. 2003.

Lyness JN, Moler CB. Numerical Differentiation of Analytic Functions. SIAM J Numer Anal. 1967;4:202–10. https://doi.org/10.1137/0704019.

Martins J, Sturdza P, Alonso J, Martins JR, Alonso JJ. The complex-step derivative approximation. ACM Trans Math Softw Assoc Comput Mach. 2003;29:245–62. https://doi.org/10.1145/838250.838251.

Conolly J, Lake M. Geographical information systems in archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006. p. 338.

Campbell AR. Numerical Analysis of Complex-Step Differentiation in Spacecraft Trajectory Optimization Problems. 2011.

Lai KL, Crassidis JL. Extensions of the first and second complex-step derivative approximations. J Comput Appl Math. 2008;219:276–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cam.2007.07.026.

Kiran R, Khandelwal K. Automatic implementation of finite strain anisotropic hyperelastic models using hyper-dual numbers. Comput Mech. 2015;55:229–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00466-014-1094-1.

Kiran R, Li L, Khandelwal K. Complex perturbation method for sensitivity analysis of nonlinear trusses. J Struct Eng. 2017;143:04016154. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)st.1943-541x.0001619.

Kiran R, Khandelwal K. Complex step derivative approximation for numerical evaluation of tangent moduli. Comput Struct. 2014;140:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruc.2014.04.009.

Lai KL, Crassidis JL, Cheng Y, Kim J. New complex-step derivative approximations with application to second-order Kalman filtering. Collect. Tech. Pap. - AIAA Guid. Navig. Control Conf., vol. 2, 2005, p. 982–98. https://doi.org/10.2514/6.2005-5944.

Squire W, Trapp G. Using complex variables to estimate derivatives of real functions. SIAM Rev. 1998;40:110–2. https://doi.org/10.1137/S003614459631241X.

Hagan MT, Demuth HB, Beale MH, De Jesus O. Neural network design. 2nd ed. Oklahoma: Martin Hagan; 2014.

Hagan MT, Menhaj MB. Training feedforward networks with the Marquardt Algorithm. IEEE Trans Neural Netw. 1994;5:989–93. https://doi.org/10.1109/72.329697.

Acknowledgements

Research presented in this paper was supported by the National Science Foundation under NSF EPSCoR Track-1 Cooperative Agreement OIA #1946202. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Funding

National Science Foundation under NSF EPSCoR Track-1 Cooperative Agreement OIA #1946202.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RK: Conception, design of work, interpretation of results, revising the manuscript, and acquiring funding. DLN: execution, data generation, coding, first draft preparation, interpretation of results, and revision of manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kiran, R., Naik, D.L. Novel sensitivity method for evaluating the first derivative of the feed-forward neural network outputs. J Big Data 8, 88 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-021-00480-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-021-00480-4