Abstract

Non-voluntary migration has been demonstrated to have an impact on family relationships as a result of children acculturating to the host country faster than their parents. Studies have reported on immigrant parents’ perceptions of their parenting in host countries. However, less is known about how both children and parents view and make sense of their relationships in new contexts. This exploratory qualitative study aims to capture the dialectical processes in parent-child relationships among Somali families in Sweden. Data were collected using focus group discussions with youth (n = 47) and their parents (n = 33). The data were analysed using a thematic analysis. Two themes, each with three themes of their own, were identified from the analysis: finding a balance between hierarchical and egalitarian relationships and sharing of spaces. Youth and parents described different factors, including contextual changes, generational gaps, peer pressure and lack of a father figures, as affecting their relationships with each other and sometimes creating conflicts between them. Both perceived themselves as active agents in contributing to family life after migrating to Sweden. In general, the youth expressed their emotional needs, the motivations desired from their parents and their desire to be equally treated as sons and daughters. Overall, this study demonstrates that there is a need to offer immigrant families culturally tailored parenting support programmes, thereby strengthening parent-child relationships.

Highlights

-

This study aimed to describe the dialectical processes in parent-child relationships among Somali families in Sweden.

-

There was a discrepancy between the parents’ and youths’ narratives of the dialectical processes in their relationship.

-

An acculturation gap, peer pressure and a lack of a father figure were perceived to have negative impacts on parent-youth relationships.

-

Both youth and parents described themselves as active agents.

-

The youth stressed their emotional needs and the desire for sons and daughters to be treated equally.

Similar content being viewed by others

After the 1991 civil war in Somalia, many Somalis emigrated from their homeland to different countries around the world, including Sweden. Previous studies have shown that post-immigration factors such as acculturation dissonance and loss of social networks bring about several challenges for Somali parents raising their children in Western countries. These challenges include insufficient knowledge of parenting practices and social obligations as parents in their new host countries. In turn, parenting difficulties have been shown to have an impact on their confidence in parenting and their relationships with their children (Bowie et al., 2017; Lewig et al., 2010; Mohamed & Yusuf, 2012; Osman et al., 2016). Positive effects of culture-sensitive parenting education (including education about societal structure, parental values and children’s rights) have been documented. These effects include improved mental health and a sense of competence in parents, as well as decreased social, attention and behaviour-externalisation problems in children (Osman et al., 2019; Osman et al., 2017a, 2017b; Renzaho & Vignjevic, 2011).

However, less is known about children’s perspectives on the enhanced knowledge their parents acquire from parenting support programmes and how these perspectives correspond to parents’ views on their own parenting. By examining the interview reports of Somali youth and parents, we can gain knowledge about the nature of the dialectical processes in parent-child relationships, knowledge that can be used to support parents’ and children’s acculturation processes.

Family Change Models

Currently, nearly 100,000 Somalis live in Sweden, meaning Somalis are the host country’s largest immigrant group from Africa. More than two-thirds were born in Somalia, and one-third were born in Sweden but have two Somali-born parents (Statistics Sweden, 2018). Somalia has a traditional society, characterised by its collectivistic orientation and extended families, with children valued for both economic and emotional dependencies. The family structure is built on hierarchy, obedience and an authoritarian parenting style, and it is organised according to patrilineal kinship with strong familial ties (Luling, 2006). In Somali culture, extended family and social connectedness provide support in child-rearing and the maintenance of family values (Heger Boyle & Ali, 2010). According to Kagitcibasi’s (2013) family change theory, this family type is called a model of interdependence.

When coming to Sweden, Somali parents encounter a different culture, typical of Western, industrial and middle-class societies, characterised by individualism and independence of families from each other. This family type is called a model of independence (Kagitcibasi, 2013), where autonomy is highly valued, lower economic and (to some degree) emotional interdependencies are present and reasons for having children are emotional. Compared with women in other countries, their Swedish counterparts have more opportunities to combine work and family responsibilities early in their children’s lives (Bergman & Hobson, 2002). It is also a strong belief that both mothers and fathers should take equal responsibility for parenting (Allard, 2007). Equality is also reinforced in the relationships between parents and children, where youth and adults are treated equally (Harkness et al., 2011). An international study finds that Swedish parents differ from parents in other countries in the ways and the frequency with which they emphasise children’s rights in the family and in family life (Harkness et al., 2011).

When the Somali family model of interdependence meets the Swedish family model of independence, the family change theory suggests that this does not necessarily mean that Somali parents need to adopt the independent Western family model (Kagitcibasi, 2013). Instead, the family model of psychological or emotional interdependence is expected to emerge, assuming that material interdependencies weaken, whereas psychological or emotional interdependencies are maintained. This model demonstrates emotional interdependence at both family and individual levels but calls for independence at both levels in material aspects. The model also assumes a coexistence of, on the one hand, an authoritarian parenting style, relatedness and control and, on the other hand, an orientation toward autonomy and permissive childrearing (Kagitcibasi, 2013). However, many Somali immigrants have left the collectivist societal support they had in their home country, which is central to the extended family system (Degni et al., 2006), and they lack the support for child rearing that the extended family and the collective society originally provided (Degni et al., 2006; Heger Boyle & Ali, 2010; Nilsson et al., 2012; Osman et al., 2016). The absence of both the extended family and collective society creates loneliness and stress in parenting as well as conflicts between parents and between parents and children. In several studies, Somali immigrants reported a dual challenge in their host countries: to acculturate themselves to the new country and culture and to make a decent living for their family (Bowie et al., 2017; Degni et al., 2006; Heger Boyle & Ali, 2010; Nilsson et al., 2012; Osman et al., 2016).

Acculturation and Parent-child Relationship

Refugees who flee their native countries for social or political reasons usually encounter stressful experiences in engaging with different cultures and in facing psychological and family changes that challenge their beliefs, values, family relations and practices (Kuczynski et al., 2013). Of course, challenges to and changes in people’s values and beliefs might occur in other situations, but for immigrant families transitioning from collective to individualistic society, acculturation dissonance has a much stronger presence. Immigrant families may have experienced social disorder, war and violence in their homelands, which can have an impact on family relationships (Hart et al., 2006). As a result of immigration to a new country, parents may encounter difficulties in adopting a new culture and may feel that their relationship with their children has changed and that their parenting ability is under stress in a number of ways (Fleck & Fleck, 2013). For instance, children learn the host country language from school and peer interactions (Tyyskä, 2007), which in turn causes an intergenerational gap in communication, adoption of the host culture and transmission of identity (Anisef & Kilbride, 2000). Furthermore, studies show that youths’ rapid language learning contributes to role reversal as parents become dependent on their children for communicating with service agencies, interpreting (e.g. serving as interpreters for school), paying bills and even making financial decisions on behalf of their families (Putman, 1993; Tyyskä et al., 2007). In this way, immigrant children are acculturated and navigate the system faster than their parents (Lau et al., 2005). This is also true for Somali children, and Somali parents have reported an acculturation gap between themselves and their children due to (among other reasons) the latter’s more efficient language learning and understanding of the host country’s values, norms and systems (Mohamed & Yusuf, 2012), factors that have contributed to the conflicts between parents and children (Degni et al., 2006; Heger Boyle & Ali, 2010; Nilsson et al., 2012; Osman et al., 2016).

Acculturation gaps may give rise to role reversal (Trickett & Jones, 2007) and conflict between parents and children as a result of the children’s rejection of their parents’ authority (Bowie et al., 2017; Osman et al., 2016; Roche et al., 2015). As children take on new roles and responsibilities, some parents may feel the loss in their leadership role and struggle to restore their authority over their children, which may result in family conflict (Creese et al., 1999) and higher levels of psychological distress (Trickett & Jones, 2007). Furthermore, role reversal may escalate, as children learn that certain disciplines from their parents’ culture are considered abusive in the host culture and consequently resist their parents’ cultural disciplinary practices (Mohamed & Yusuf, 2012), whereas parents consider adolescents’ resistance to be a loss of respect and challenge to parents’ authority (Heger Boyle & Ali, 2010; Nilsson et al., 2012). The disagreement persists as a result of the conflicting desires of adolescents seeking autonomy and parents struggling to maintain family harmony by upholding obedience, hierarchy, loyalty and attachment (Kwak, 2003).

Dialectical Processes in the Parent-child Relationship

Studies by Kuczynski et al. (2013) and Kwak (2003) surmise that parent-child conflicts cannot merely be due to the acculturation gap but also to the intergenerational gap. Kuczynski et al. (2013) describe the parent-child relationship as a bidirectional and dialectical socialisation process in which both parents and children are equal agents affecting each other and their common relationship. This means that parents and children have the capacity to construct and make sense of their experiences and to exercise their agency in the culture and context in which they live. According to Kuczynski and Mol (2015), parents’ and children’s actions depend on three categories of power resources: individual, relational and cultural. In terms of individual resources, parents and children use their expertise, cognitive abilities or physical strength to bring about their desired outcomes in the parent-child relationship. Parents and children employ relational resources when they use the resources provided by others to influence their agency. A parent may seek the alliance of his/her spouse, friends or extended family to achieve his/her goals in the relationship. Youth may also seek to enhance their agency by using external relational resources, such as a teacher or other family member who is responsive to their requests. Parents and children act upon their agency depending on the cultural resources they have. The embedded cultural practices, such as rights, customs and entitlements, are important sources that affect parent-child agency. For instance, in a cultural context where children are expected to show total obedience to and respect for adults, youth have fewer cultural resources with which to amplify their agency. However, this is not always the case: in some contexts and situations, children’s agency is not totally rejected (Santah, 2020). In societies where children have the right to express their autonomy, they exercise their power due to the existing norms and rules in these societies (Kagitcibasi, 2013; Kuczynski & Mol, 2015).

According to the social relational theory of family acculturation (Kuczynski et al., 2013), parents and children form their working models based on the context in which they live. When parents live in their own country, the intergenerational transmission of cultural values and parenting practices may be easy since parents are supported by the external environment. However, in the context of immigration, parents’ and children’s adaptation to the new context and culture may not be synchronised, and children may have more power in the parent-child relationship (Kuczynski & Knafo, 2013). Parents’ working models are not the same as those of their children (Kuczynski et al., 2013). In the new context and culture, parents are separated from their social and cultural resources, and their children’s working models are formed through interaction with peers and adaptation to the new culture.

The social relational theory (Kuczynski et al., 2013; Kuczynski & Mol, 2015) is an effective framework for studying immigrant families’ relationships in the acculturation process because it takes into account the perspectives of both parents and children and also highlights the impacts of several dynamics on individuals and relationships. Furthermore, it considers the process of change that individuals and families encounter as a result of immigration.

The Present Study

Altogether, previous studies in Sweden (Osman et al., 2016; Osman et al., 2019) involving Somali-born parents report that they encounter a number of challenges in raising their children, such as insufficient knowledge of parenting practices and parental social obligations in the host country. Furthermore, parents have poor confidence in their parenting ability and lack a good relationship with their children (Mohamed & Yusuf, 2012; Osman et al., 2016). The purpose of this study is therefore to capture the dialectical processes in the parent-child relationship among Somali families in Sweden and, by doing so, gain knowledge that can be used to better support immigrant parents’ and adolescents’ acculturation processes.

Methods

An exploratory qualitative approach using focus group discussions (FGDs) (Creswell, 2013) was used in this study. The present work is part of a larger study that evaluated the impact of Ladnaan (2015), a culturally tailored parenting support programme for Somali-born parents living in a Swedish middle-sized town. The Ladnaan programme aimed to improve the mental health of children and parents and to strengthen the parent-child relationship (Osman et al., 2017a, 2017b). The Ladnaan programme consisted of two components: the evidence-based parenting programme Connect, which is based on attachment theory (Moretti et al., 2009), and societal information, which was developed through qualitative findings from Somali-born parents living in Sweden (Osman et al., 2016). It comprised 12 weekly sessions with 12–17 parents, each session lasting 1–2 h. This present study sought to capture and describe the current parent-child relationships three years after parents participated in the Ladnaan programme. A detailed description of the research project was published elsewhere (Osman, 2017).

Participants

The participants were Somali youth living in Sweden (the Somali youth participants indicated that they preferred to be called “Somali” rather than “Somali-Swedish”), the parents of whom participated in the Ladnaan programme. These families were contacted by phone and informed about the study’s purpose and procedures. Those who were interested were given written and oral information and were invited to participate in an FGD. All youth gave their consent for participation; for those under 15 years old, consent was obtained from their parents. In almost every FGD, 1 or 2 siblings from the same families participated together. In total, 6 FGDs with 47 youth (25 girls and 22 boys) were conducted.

The participants also included the parents of the Somali youth in this study. The Somali parents were also asked if they wanted to participate in group discussions with other parents. All parents consented to participate in the FGDs, although 4 participants could not join 2 FGDs due to sickness or other personal reasons. In total, 6 FGDs with 33 parents (23 mothers and 10 fathers) were held.

The age of the youth was between 14 and 18 years, and almost half of the youth had lived in Sweden for less than five years. Some youth had come to Sweden with their parents, and some had joined their parents in Sweden after the parents had already arrived. Approximately 60% were in lower secondary school. The parents were of a mean age of 45 years. At the time of the study, 39% of the parents had lived in Sweden for up to five years. None of the parents or youth in our sample had lived in any other Western country before arriving in Sweden. The number of children living at home ranged between 2 and 13, and 26 of the parents were married and lived with their spouses. The majority of the parents had lower secondary education.

Data Collection

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala, Sweden (DNR 2014/048/2). The data were collected in 2018 using a semi-structured, pre-defined interview guide, which was pilot tested with the first of each FGD group (youth and parents). The interview guide was not revised after the pilot test. Conducting FGDs has both advantages and disadvantages. FGDs can enable the collection of rich data in which the participants describe their experiences and build on their thinking, contributing to both general and in-depth discussions. Additionally, one strength of this study is that the data were collected from both the youth and their parents in the same household. Both the youth and parent FGDs inquired about parenting practices, the current relationships between the parents and their children, and what might contribute to the improvement of the parent-child relationships. The FGD participants were asked probe questions and were requested to give examples of their relationship. All FGDs were tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data Analysis

All transcribed data were analysed inductively using the six-phase approach of Braun and Clarke’s (2012) thematic analysis. The FGDs with the parents and the youth were analysed separately. The analysis started with a general data familiarisation by reading the responses several times to obtain an overview of the content. This first phase included taking notes and highlighting sentences and paragraphs that captured or related to the concept of a dialectical process in the parent-child relationship. In the second phase, codes were systematically extracted from the data to a table, which was used to devise a coding scheme to apply to the data. The codes explicitly focused on the core object of the analysis and were on a descriptive level—the parents’ and youths’ experiences and perceptions of the dialectical processes in the parent-child relationship. In the third phase, when the entire text was coded, the authors reviewed and clustered the codes based on their similarities and differences. Several themes were identified and then clustered under different subthemes. In the fourth phase, the authors compared and discussed the potential subthemes that had been identified from the codes. The potential subthemes were then refined so that each theme was broad enough to capture a set of the participants’ experiences and perceptions. All the subthemes were merged and arranged into themes that encapsulated and summarised the core of the subthemes. In the last step of the analysis, the authors reviewed the themes and the subthemes and compared them to the codes. To ensure the findings’ credibility and confirmability, all authors discussed the findings until they reached a consensus on the themes.

Results

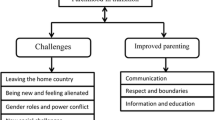

The analysis identified two themes: 1) finding a balance between hierarchical and egalitarian relationships and 2) sharing of spaces. These two overarching themes were further broken down, each consisting of three subthemes.

Finding a Balance between Hierarchical and Egalitarian Relationships

The theme finding balance between hierarchical and egalitarian relationships includes three subthemes: describing past and present relationships between parents and youth, demanding changes that influence the relationship and creating mutual influence in agency.

Past and Present Relationships

The study identified a discrepancy between parents’ and youths’ narratives of the dialectical processes in parent-child relationships. The parents discussed the relationship between themselves and their children based on the Ladnaan programme, while the youth compared Somali parents with Swedish parents.

The youth discussed how Somali parents used authoritarian parenting in general and how this led to conflicts and non-disclosure. As one participant expressed, “They [Somali parents] know only how to shout at the child; they say to do that and that, then the child pretends to obey just to satisfy the parents” (FGD1, female youth (FY) 1). Some youth, particularly those who had lived in Sweden for a short period only, argued that the authoritarian way of parenting could be useful for some youth and that Somali parents want what is best for their children:

“But it is in our interest when parents are shouting at us because if we are at home using our mobile phones all the time, boys are playing videogames, so no one does their homework, but if the parents shout at us and take the mobile phones from us, then we take the books” (FGD1, FY 3).

Furthermore, the youth highlighted the importance of setting rules and boundaries and how their lack could lead to problems for boys:

“To discipline the child, this means taking him to good places like mosques and advising him. I saw other children going with bad friends, and then going to buy or sell drugs. Parents should ask the child how school was today, but some children are going out, coming back and then sleeping” (FGD2, male youth (MY) 5).

However, other youth who were against the authoritarian style of parenting described the importance of balancing authoritarian and relational parenting:

“So let them grow as a person so they can explore themselves. It is they who are growing, then you have a friendly relationship with your daughter, and you ask her, for example, what is happening today? What did you do in school?” (FGD3, FY 1).

On the other hand, parents attributed the improvement of their relationship with their children to the parenting programme they attended. All parents in this study reported changing their parenting practices and switching from the authoritarian way of parenting to authoritative parenting. Moreover, due to this shift, many parents reported being amenable and vulnerable to their children’s emotional needs:

“I do much more now, try to understand why my child is angry, what made him angry, understand what makes him happy, respect his opinion and talk gently with him. This is not something we did before the course, and this made our relationship much better” (FGD2, father 4).

Demanding Changes that Influence the Parent-child Relationship

Somali youth and their parents described different factors affecting their relationship and sometimes creating conflicts between them. From the youths’ perspective, the parent-child relationship was influenced by contextual changes, generational gaps, peer pressure and lack of a father figures. In these youths’ experiences, immigration to a new country contributed to power imbalances and conflicts between parents and children. Some youth reported that their Somali peers understood the rights of children in the new context in erroneous ways and began to refuse to listen to their parents:

“When you come to Sweden, you hear things like, ‘you can decide what you want. It is a free country, and nobody [parents] can tell you what to do. You can live as you want’. And then this goes to their heads, and they think they can do whatever they want” (FGD5, FY 1).

Power imbalances and conflicts were caused by youths’ more rapid adaptation to the new societal context than their parents, which resulted in youth becoming both language and cultural brokers for their parents:

“When parents and children come to this country, they do not understand each other, especially when parents are not integrated in the country. Children learn the language faster” (FGD6, FY 2).

“And you become an interpreter for your mom. You read even letters [from authorities] to her. You do all those things. Technically… you grow up faster, reading letters or paying the bills, and we are their interpreters, and this creates the relationship imbalance” (FGD3, FY 1).

Peer pressure and lacking/missing father figures were reported by the youth, particularly the boys, to cause power conflicts negatively affecting their parent-child relationships. Both the boys and girls explained that single mothers had difficulties since they needed to be both a mother and a father to their children:

“Most of the foreign-born kids – their mothers are single mothers. When the children reach a certain age, and they need their fathers, I think that is why you do not listen to her [mother], and most of the foreign-born kids have no fathers” (FGD5, MY 3).

Like their children, the parents explained that the contextual change, moving from their home country to the host country, introduced acculturation gaps to the parent-child relationship. However, adapting to the new context was also perceived as an opportunity to improve the relationship between them. One parent explained, “As the Somali saying [goes], ‘Be and behave like everybody in that context [When in Rome, do as the Romans do],’ and we need to raise our children the way one does in this context” (FGD1, mother 1).

Creating Mutual Influence in Agency

This subtheme captures two active agencies in the relationship: both the youth and parents had the responsibility and possibility to affect their relationships in positive and negative ways. The youth were aware they had control over the relationships with their parents and could influence these relationships in ways they perceived would be beneficial for them. They expressed their agency in two different ways: first, by taking into consideration their parents’ moods and calming down or stepping back when their parents were upset, and second, by confronting or reasoning with their parents when they felt that their parents were not looking at an issue from their children’s perspectives. For example:

“I tell them [my parents] that I cannot be what they want me to be. I cannot do and have no capacity to achieve it, so if I take [their] choice, I may fail. I tell them how I feel” (FGD2, MY 1).

Like the youth, the parents also constructed their agency in the new context, meaning that changed their parenting methods to accommodate the Swedish norms. Somali parents reported that they stepped back and gave their children more freedom to articulate their needs and ideas. However, the parents’ motivation came from a belief that their positive interactions with their children would change the latter’s behaviours:

“I came up with different ideas and ways to behave with my children, and when the children saw change in [my] parenting, they changed” (FGD1, mother 6).

“Parents must change themselves if they do this and behave kindly with their children. I believe children come closer to them. Now there is harmony, and the relationship has changed; there are satisfaction, happiness and good communication” (FGD6, father 1).

Sharing of Spaces

The theme sharing of spaces describes parents’ and youths’ desire to improve their relationships. This overarching theme includes three subthemes: fulfilling emotional needs, communicating and being available and trusting and sharing decisions.

Fulfilling Emotional Needs

Youth and parents understood the emotional needs of the former in different ways. The youth generally expressed that they wanted their parents to motivate them in becoming empowered and accepted. The boys in particular emphasised the need for emotional support from their parents and described how this would make them mentally strong. As one boy expressed:

“In my view, there is a lack of mental and emotional support given to the Somali youth. This means if the Somali parents give emotional support to their child, he/she will develop mentally” (FGD6, MY 1).

In two of the FGDs, the girls described receiving emotional support, but they also reported gender bias in their parents. The girls felt that they received emotional support but less freedom to be independent. The freedom granted to the boys resulted in their being in trouble as reported by the girls. The girls felt that parents took their daughters to vacations abroad, while the boys stayed with other relatives in Sweden. According to the girls from these two FGDs, parents were afraid of the shame and what the Somali community might say about their daughters if they displayed any bad behaviour or brought shame to their families. However, in these same two FGDs, youth of both genders reported that for Somali parents, the fear of shame over their child committing criminal acts or abusing substances was the same for both daughters and sons.

As opposed to the youth, the parents never mentioned differentiating between their daughters and sons. However, in two of the FGDs, the fathers discussed how they softened their treatment of their sons and started becoming friends with them. Somali parents described how they increased their understanding of their children’s emotional needs due to their more sensitive parenting. The parents explained that they made a conscious decision to try to improve their relationship with their children by understanding and meeting their emotional needs.

“The strategy I used to improve our relationship was to be more empathetic and humble. Because having empathy is the only way you can improve your relationship with your children, no one benefits from being strict” (FGD1, mother 6).

Communicating and Being Available

The Somali youth and their parents agreed on the importance of spending time with each other and having regular communication. For the youth, communication and interaction involved parents asking their children about their feelings and their day, not for interrogation but as a way to understand and help them. The youth emphasised the importance of spending time with each other. “Parents must spend time with their children, talk to and go outside with them; then the child will see his/her parents as caring persons” (FGD6, FY 1). The youth also discussed their hopes for themselves as future parents. One girl said, “Always talk with them, have contact with them, do things together” (FGD4, FY 3).

The parents explained that communication with their children had improved. They also perceived communication as a way to avoid conflicts and ameliorate their own stress.

“The stress will be gone if you have good communication, listen to your child, ask how his/her day was. So this gives all of us mental wellbeing, stability at home, love and compassion” (FGD3, mother 2).

Trusting and Sharing Decisions

The youth described trust and shared decisions from the point of view of becoming parents themselves. They also reported that mutual trust had a positive impact on their relationship with their parents. The youth underlined that trusting each other would make them disclose to their parents the difficulties they were going through. Regarding decision-making, the youth had different opinions. While some emphasised the importance of parents giving them a choice, others argued that parents always consider what is best for their children. These were some of the ways youth wanted to parent.

As future parents, they would want to be their children’s best friends and have trust in each other. “Good relationship and trust each other. Become their best friend” (FGD4, FY 6). Somali parents saw sharing decisions and asking for feedback from their children as symptoms of increased trust between them. The parents indicated that due to their growing reflectiveness and awareness, they started looking at things from their children’s point of view.

“I have made many changes in my parenting practices. For example, I didn’t reflect previously that children had a role and [their] viewpoint of family matters, but now, I have started to listen to their ideas and suggestions. I have begun to consult with my children, consider what they like and do not like” (FGD2, father 2).

Another father, in agreement with this view, said, “Parents and youth are friends, and the home is stable now. We began to discuss and consult on every issue” (FGD2, father 6).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to capture the dialectical processes in parent-child relationships among Somali families in Sweden. Our analysis showed that youth and parents had different narratives of these dialectical processes. Neither the youth nor the parents talked about their current relationship, except in 1 of the youth FGDs, in which they described their current relationships with their parents and how they saw their parents as role models. The parents discussed parent-child relationships in terms of the parenting support programme that they had attended previously, while the youth discussed their views of the ideal parent-child relationship.

Contextual Change Requires a New Way of Parenting

As anticipated, the youth raised issues having to do with moving to a new country, the impact of the change on family relations and their social position relative to their parents insofar as the children often served as brokers to the new society. The generation gap weakened the possibility of support for both parents and children because of the loss of family networks and generational chains. Family separation—that is, spatial dispersion of the nuclear family—has been shown to be a post-migration stressor that negatively affects the mental health of family members. In particular, the presence or absence of a father figure plays an important role in mental health (Löbel, 2020). Several of the youth lived in the new country with only one parent, usually a single mother, and the lack of a father figure influenced their relations and put pressure on the single parent. Thus, adjustments in the parental role were required in the new country, and elements of a more individualistic, interactive parenting role emerged. The youth compared their parents to Swedish parents, which is certainly natural in a new context. Adolescent years comprise an intense time of socialisation and identity-seeking, when comparisons among young people are constantly made (Pfeifer & Berkman, 2018) and the reception of positive or negative attention becomes especially important for adolescents’ self-image and wellbeing (Randell et al., 2016).

The youth described their parents as having undergone changes in their parenting style, from being highly demanding and maintaining hierarchical positions and control to becoming responsive, understanding, and involved parents. The parents explained that changes in their parenting style occurred after participating in the parenting programme; they were listening more to their children’s signals and were more emotionally present. Furthermore, they had learned to listen and solve problems instead of deciding for their children. According to Kagitcibasi’s (2013) family change theory, the changing context and culture deemphasised the family model of interdependence to which the Somali immigrants were accustomed. In the new context, material interdependencies weakened and psychological or emotional interdependencies increased. The Somali-born parents explained that after completing the parenting programme, their responsiveness increased, and their eyes were opened to the emotional needs of their children. Several of the youth in the study expressed the importance of open communication with their parents and being listened to.

Changes in Positions and Gender

After coming to Sweden, the Somali-born parents underwent a transformation of the power relations within their families. The assumption of unequal power between parents and children is fundamental when describing parent-child relationships (Kuczynski et al., 2013). Children’s acculturation process is faster than that of their parents, and culture has been demonstrated as an important source of children’s power (Kuczynski et al., 2013). The youth in this study learned many of their attitudes, values and behaviours from Swedish culture and language, allowing them to assist their parents in reading letters from authorities, served as brokers between parents and Swedish cociety and take on more adult roles. Their language skills and more adult roles contributed to a changing power balance in their families that gave youth in their new country power they had not had previously.

Differences in the parents’ treatment of their children were gender based, and the youth experienced certain inequalities between boys and girls. The girls in the study reported that their parents had stricter boundaries than they did for the boys. At the same time, the girls received more emotional support than the boys. Increased control alongside increased emotional support may be experienced by the girls as contradictory. While the boys were described as possessing more freedom but receiving less emotional support, some boys could not manage their freedom responsibly. Unclear boundaries and lack of control and support could lead some boys to trouble. Several of the youth underscored the importance of not only clear behavioural boundaries but also emotional support.

Thus, gender seemed to be an important underlying factor in the parent-child relationship, producing more restrictions for the girls and fewer for the boys. There were some differences in the parents’ and the youths’ descriptions of gender. The parents explained that they did not differentiate between their daughters and sons, while the youth highlighted gender differences in their parents’ treatment of them. This discrepancy may be due to the traditional gender norms such as more control for girls than boys that are deeply embedded in thinking, behaviour and culture, something that adults rarely reflect on. Shame was an important emotion-shaping social behaviour and a factor in setting boundaries for girls. Emotions, such as shame is an indicator of the quality of a social bond, signalling a threatened bond and alienation (Scheff, 2003). One study conducted among adolescent boys showed that experiencing secure relationships within the family and with close friends who can provide emotional support is vital for boys’ health and wellbeing (Randell et al., 2016).

However, a couple of fathers described how they had softened their parenting style and developed friendships with their sons. This is an example of adopting broader gender norms in parental behaviours due to contextual changes.

Agency and Emotional Interaction

In line with the theories of Kagitcibasi (2013) and Kuczynski et al. (2013), the youth in this study acculturated faster in the new society, and the families were forced to find new ways of functioning between two cultures. The parents struggled to find a balance between hierarchical and egalitarian approaches. The parents felt that they could no longer decide for their children, as they did in the home country, where their power was a given and not questioned. New skills were required to cope with their family life and children in a new cultural context, such as negotiating with the children and making decisions together. Thus, new dialectical practices were developed, and new reciprocal relationships were established. This new parenting style aligns with the model of emotional/psychological interdependence, which synthesises traditional Western individualistic values that reinforce autonomy and the family model of interdependence that is prevalent in rural societies. This new model reinforces both intergenerational interdependence and collectivistic values (Kagitcibasi, 2013).

The parents explained that they eventually came to understand the emotional needs of their children due to their increased consciousness and communication with their children. Responses emphasised dynamic processes in parent-child relationships, processes to which both children and parents contributed. They shared a common space where the views of both the youth and parents mattered and were communicated. Mutual trust and the ability to decide together were underlined. Trust was a prerequisite for having confidence in each other and holding open discussions. The parents expressed their awareness of the interconnectedness between their own behaviour and the behaviour and the emotions that their children displayed. The parents explained that they tried to improve their relationship with their children by understanding and meeting their emotional needs. Their ability to communicate well, ask questions and negotiate with their children helped them manage conflicts and avoid getting angry. Likewise, the youth stressed the importance of their parents asking questions about their daily lives and feelings. The youth asserted that as future parents, they would emphasise giving emotional support, being present for their children and asking their children many questions.

This study shows that both youth and parents are active agents contributing to family life after immigration to a new country. Being parents in a new country poses many challenges, but having insight into children’s emotional needs and fostering communication skills with children provides a basis for improved interaction and increased sociocultural competence.

Conclusion and Implications for Practice

This study’s findings revealed that Somali parents and youth encountered challenges and changes that had impacts on their relationships, such as unequal power between them. However, an encouraging finding is that both the parents and youth constructed and made sense of their relationship, so both perceived themselves as active agents. Parents found a way to balance hierarchical and egalitarian approaches, thereby developing and establishing new dialectical processes and reciprocal relationships. Despite positive changes in their relationship, the youth experienced gender-based differences in their parents’ treatment of them, and they sought more equal treatment of sons and daughters. The youth expressed a desire for both boys and girls to be independent and, at the same time, receive emotional support. Nonetheless, the changes reported by parents and youth in this study demonstrate an ability to adapt and construct their relationship, but it also suggests that more efforts should be made to offer immigrant families culturally tailored parenting support programmes. This support would contribute to strengthening parent-child relationships and improving parents’ and children’s mental health and acculturation processes.

References

Allard, K. (2007). Toward a working life. Solving the work-family dilemma. Göteborg: Geson.

Anisef, P., & Kilbride, K. M. (2000). The needs of newcomer youth and emerging” Best practices” to meet those needs-final report. Toronto: Joint Centre of Excellence for Research on Immigration and Settlement, CERIS Virtual Library.

Bergman, H., & Hobson, B. (2002). Compulsory fatherhood: the coding of fatherhood in the swedish welfare state. I B Hobson (red.) Making men into fathers: Men, masculinities and the social politics of fatherhood. West Nyack, NY: Cambridge university press.

Bowie, B. H., Wojnar, D., & Isaak, A. (2017). Somali families’ experiences of parenting in the United States. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 39(2), 273–289.

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol 2: Research designs: quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological. (pp. 57–71). Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association.

Creese, G., Dyck, I., & McLaren, A. (1999). Reconstituting the family: negotiating immigration and settlement. Vancouver: RIIM Working Paper No. 99–10.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. California, USA: Sage publications.

Degni, F., Pöntinen, S., & Mölsä, M. (2006). Somali parents’ experiences of bringing up children in finland: exploring social-cultural change within migrant households. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research on Social Work Practice, 7(3). Art. 8, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs060388.

Fleck, J. R., & Fleck, D. T. (2013). The immigrant family: parent-child dilemmas and therapy considerations. American International Journal of Contemporary Research, 3(8), 13–17.

Harkness, S., Zylicz, P. O., Super, C. M., Welles-Nyström, B., Bermúdez, M. R., Bonichini, S., & Mavridis, C. J. (2011). Children’s activities and their meanings for parents: a mixed-methods study in six Western cultures. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(6), 799.

Hart, J., Boyden, J., de Berry, J., & Feeny, T. (2006). Children affected by armed conflict in South Asia: a review of trends and issues identified through secondary research. In G. Reyes, & G. A. Jacobs (Eds), Handbook of International Disaster Psychology: Interventions with Special Needs Populations (Vol. 4, pp. 61–76). Praeger.

Heger Boyle, E., & Ali, A. (2010). Culture, structure, and the refugee experience in somali immigrant family transformation. International Migration, 48(1), 47–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2009.00512.x.

Kagitcibasi, C. (2013). Family, self, and human development across cultures: theory and applications. New York, NY, USA: Psychology Press.

Kuczynski, L., & Knafo, A. (2013). Innovation and continuity in socialization, internalization and acculturation. In M. Killen & J. G. Smetana (Eds), Handbook of Moral Development, 2nd edition (pp. 93–112). New York, NY: Taylor and Francis Publishers.

Kuczynski, L., & Mol, J. D. (2015). Dialectical models of socialization. In W. F. Overton & P. C. M. Molenaar (Eds), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Kuczynski, L., Navara, G. S., & Boiger, M. (2013). The social relational perspective on family acculturation. In S. S. Chuang & R. P. Moreno (Eds), Immigrant children - change, adaptation, and cultural transformation (pp. 171–191). Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books.

Kwak, K. (2003). Adolescents and their parents: a review of intergenerational family relations for immigrant and non-immigrant families. Human Development, 46(2-3), 115–136.

Lau, A. S., McCabe, K. M., Yeh, M., Garland, A. F., Wood, P. A., & Hough, R. L. (2005). The acculturation gap-distress hypothesis among high-risk Mexican American families. Journal of Family Psychology, 19.3, 367–375.

Lewig, K., Arney, F. & Salveron, M. (2010). Challenges to parenting in a new culture: Implications for child and family welfare. Evaluation and Program Planning, 33, 324–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2009.05.002.

Luling, V. (2006). Genealogy as theory, genealogy as tool: aspects of Somali ‘clanship’. Social Identities, 12(4), 471–485.

Löbel, L. M. (2020). Family separation and refugee mental health–A network perspective. Social Networks, 61, 20–33.

Moretti, M. M., Braber, K., & Obsuth, I. (2009). Connect. An Attachment-focused treatment group for parents and caregivers–A principle based manual. Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada: Simon Fraser University.

Mohamed, A. & Yusuf, A. M. (2012). Somali parent-child conflict in the western world: Some brief reflections. Bildhaan: An International Journal of Somali Studies, 11, 17.

Nilsson, J. E., Barazanji, D. M., Heintzelman, A., Siddiqi, M., & Shilla, Y. (2012). Somali women’s reflections on the adjustment of their children in the United States. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 40(4), 240–252. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1912.2012.00021.x.

Osman, F., Klingberg-Allvin, M., Flacking, R., & Schön, U.-K. (2016). Parenthood in transition – Somali-born parents’ experiences of and needs for parenting support programmes. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 16(7), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-016-0082-2.

Osman, F., Flacking, R., Schön, U.-K., & Klingberg-Allvin, M. (2017a). A Support program for somali-born parents on children’s behavioral problems. Pediatrics, 139(3). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-2764.

Osman, F., Salari, R., Klingberg-Allvin, M., Schön, U.-K., & Flacking, R. (2017b). Effects of a culturally tailored parenting support programme in Somali-born parents’ mental health and sense of competence in parenting: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open, 7(12). http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/7/12/e017600.abstract.

Osman, F., Flacking, R., Klingberg Allvin, M., & Schön, U.-K. (2019). Qualitative study showed that a culturally tailored parenting programme improved the confidence and skills of Somali immigrants. Acta Paediatrica, 108(8), 1482–1490. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.14788.

Osman, F. (2017). Ladnaan – evaluation of a culturally tailored parenting support program to Somali-born parents. (PHD thesis). https://openarchive.ki.se/xmlui/handle/10616/46135.

Pfeifer, J. H., & Berkman, E. T. (2018). The development of self and identity in adolescence: neural evidence and implications for a value-based choice perspective on motivated behavior. Child Development Perspectives, 12(3), 158–164.

Putman, D. B. (1993). The Somalis: their history and culture. CAL Refugee Fact Sheet Series, 9, 1–22.

Randell, E., Jerdén, L., Öhman, A., & Flacking, R. (2016). What is health and what is important for its achievement? A qualitative study on adolescent boys’ perceptions and experiences of health. The Open Nursing Journal, 10, 26.

Renzaho, A. M., & Vignjevic, S. (2011). The impact of a parenting intervention in Australia among migrants and refugees from Liberia, Sierra Leone, Congo, and Burundi: results from the African Migrant Parenting Program. Journal of Family Studies, 17(1), 71–79. https://doi.org/10.5172/jfs.2011.17.1.71.

Roche, K. M., Lambert, S. F., Ghazarian, S. R., & Little, T. D. (2015). Adolescent language brokering in diverse contexts: associations with parenting and parent–youth relationships in a new immigrant destination area. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(1), 77–89. 1.

Santah, C., (2020). Children’s matters: negotiating illness in everyday interactions at home and school in Ghana. Universiteit van Amsterdam.

Scheff, T. J. (2003). Shame in self and society. Symbolic Interaction, 26(2), 239–262.

Statistics Sweden. (2018). Befolkning efter födelseland, ålder och kön. Population by country of birth, age and sex. http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/.

Trickett, E. J., & Jones, C. J. (2007). Adolescent culture brokering and family functioning: a study of families from Vietnam. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 13.2, 143–150.

Tyyskä, V. (2007). Immigrant families in sociology. In J. E. Lansford, K. Deater-Deckard & M. H. Bornstein (Eds), Immigrant families in contemporary society (pp. 83–99). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Dalarna University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Osman, F., Randell, E., Mohamed, A. et al. Dialectical Processes in Parent-child Relationships among Somali Families in Sweden. J Child Fam Stud 30, 1752–1762 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-01956-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-01956-w