Abstract

As employees’ personal lives are increasingly splintered by work demands, the boundary between work and nonwork domains is becoming ever more blurred. Grounded within a self-regulatory approach and the executive control function of inhibitory control, we operationalize and examine nonwork role re-engagement (NWRR)—the extent to which individuals can redirect attentional resources back to nonwork tasks following work-related intrusions. In phases 1 and 2, we develop and refine a psychometrically sound unidimensional measure for NWRR aligned with the self-regulatory processes of self-control and interference control underlying inhibitory control. In phase 3, we confirm the factor structure with a new sample. In phase 4 we validate the measure using the samples from phases 2 and 3 to provide evidence of criterion-related, convergent, and discriminant validity. NWRR was related to important well-being and work-related outcomes above and beyond existing self-regulatory and boundary management constructs. We offer theoretical and practical implications and an agenda to guide future research, as attentional agility becomes increasingly relevant in a home life replete with interruptions from work.

Similar content being viewed by others

In a 24/7 economy in which technology has enabled work to be done anywhere and anytime, employees have grown accustomed to interruptions from work when not at work. With the COVID-19 pandemic thrusting a large proportion of the global workforce into work-from-home scenarios came a pervasive loss of the formal boundary between work and home. In particular, unexpected interruptions, or boundary violations (Ashforth et al., 2000), from work during nonwork hours require temporary transitions from nonwork roles back to the work role. Boundary theory suggests these micro-role transitions are mentally and physically taxing, as one must shift mindsets and behaviors to disengage from one role and re-engage in another (Ashforth et al., 2000). Boundary research has predominantly focused on the immediate aftermath of work-related intrusions—disengaging from nonwork roles to engage in the work-related intrusion (e.g., responding to after-hours job contacts; Piszczek, 2017). The present study examines what must happen subsequently—disengagement from work and re-engagement in nonwork roles—which requires redirecting attentional resources back to the original nonwork tasks.

Despite the regularity of work-related intrusions, there is still much to learn about the attentional challenges that work-related intrusions present for nonwork life. In accordance with a self-regulatory lens, we propose executive functioning as the underlying mechanism that facilitates domain-switching (Hamilton et al., 2011; Muraven & Baumeister, 2000). Because attending to work-related intrusions requires such “gear switching,” self-regulatory resources are consumed, hindering one’s ability to switch back to nonwork tasks. We suggest that individual differences in executive control resources affect the ability to re-engage in nonwork tasks.

Grounded in a self-regulatory approach (Diamond, 2013; Muraven & Baumeister, 2000), the present research contributes to the work-family literature and boundary theory. To date, much of the research on work-related interruptions has focused on how individuals manage after-hours work communications (e.g., Boswell et al., 2016), perceptions or reactions to boundary violations (e.g., Hunter et al., 2019) and outcomes of boundary crossing behavior (e.g., Carlson et al., 2015). What is unstudied is the individual difference capability of redirecting attentional resources during this process, which may be an important linking mechanism that helps explain the adverse effects of boundary violations on individuals. Thus, the development of a self-regulatory construct grounded in cognitive psychology can clarify an important and underdeveloped boundary management process—the underlying attentional capacity needed to continually cross work-nonwork boundaries in a world in which one must inevitably do so.

We develop a psychometrically sound measure of nonwork role re-engagement, defined as the extent to which attentional resources (behaviors, cognitions, emotions) can be redirected back to nonwork tasks following work-related intrusions. The executive function of inhibitory control is a self-regulatory process that can help individuals redirect attentional resources as it represents the ability to selectively attend and focus while suppressing attention to other stimuli (Beal et al., 2005; Diamond, 2013). Accordingly, explication and assessment of nonwork role re-engagement can help develop an understanding of individuals’ capacity to redirect attentional resources back to nonwork roles following intrusions from work. Somewhat similar reasoning motivated the theorizing and recent development of a work interruption resiliency construct and measure (Zide et al., 2017) focused on interrupted work tasks. Our proposed construct and measure bookends this construct by addressing work as interrupting the nonwork space.

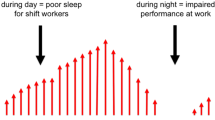

Just as occurrences of family demands interrupting work may negatively impact the work role (e.g., impaired concentration, increased attention lapses; Demerouti et al., 2007; Lapierre et al., 2012; Nohe et al., 2014), dealing with work-related intrusions during nonwork time may hinder individuals’ ability to resume and focus on nonwork tasks, and may impair the performance of nonwork tasks (e.g., keeping their child safe during play, meaningfully engaging in a conversation with one’s spouse; Leroy & Schmidt, 2016). Moreover, an inability to successfully pivot back to nonwork life may mark an unhealthy preoccupation with work and thereby strain employee well-being (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2015). To this end, we aim to: (1) operationalize the construct of nonwork role re-engagement, (2) develop and refine a measure of nonwork role re-engagement, and (3) validate the measure across two different samples.

Nonwork Role Re-Engagement: A Self-Regulatory Construct

Underlying and informing our conceptualization of nonwork role re-engagement (NWRR) are boundary management theory (Ashforth et al., 2000) and self-regulatory processes (Diamond, 2013; Leroy & Schmidt, 2016; Muraven & Baumeister, 2000). Boundary management theory addresses the ways in which individuals actively manage boundaries to uphold order in their interdependent work-nonwork lives (Ashforth et al., 2000; Nippert-Eng, 1996). Flexible work boundaries allow work to be done anywhere and anytime. Permeable nonwork boundaries allow individuals to be physically in nonwork domains while psychologically or behaviorally involved in work. Flexible work boundaries coupled with permeable nonwork boundaries allow work to intrude on nonwork life, and intrusions often require employees to pivot between roles. Attentional agility to intrusions, however, remains unexamined, thereby hindering our understanding of the relevant mechanistic pathways.

Self-regulatory processes likewise underlie NWRR (Diamond, 2013; Hamilton et al., 2011; Leroy & Schmidt, 2016; Muraven & Baumeister, 2000). While a deep discussion of these theories is space prohibitive, we take the position that individuals vary in executive control resources that help them exert self-control in the face of adverse conditions such as external stimuli that lure attention (e.g., messages from a manager) or create attentional residue (when thoughts about one task persist and intrude while performing another; Leroy, 2009). The idea that individuals differ in the degree to which they can navigate these attentional challenges is supported by Hamilton et al. (2011), who found “that switching mindsets is an executive function that consumes self-regulatory resources and therefore renders people relatively unsuccessful in their self-regulatory endeavors” (p. 21).

A core executive control function thought to underlie NWRR is the inhibitory control of attention, which “enables us to selectively attend, focusing on what we choose and suppressing attention to other stimuli” (p. 137). Inhibitory control represents the ability to control one’s behavior, thoughts, or emotions to override external stimuli so that one may do what is needed at the moment (Diamond, 2013); without it, individuals would be continually gripped by work-related intrusions, pulling them away from personal life. The idea that acts of self-control, such as inhibitory control, rely on limited attentional resources counters scholars’ arguments and prior evidence that repeated acts of self-control are not necessarily depleting (e.g., Carter & McCullough, 2013, 2014; Carter et al., 2015; Dang, 2018). However, these prior studies were focused on sequential tasks within the same (i.e., work) domain, and thus may not apply to cross-domain task interruptions. Switching from a nonwork task to a work task and then back to the original nonwork task may be more taxing and require very different mindsets, behaviors, and emotions than two sequential work tasks. Thus, inhibitory control guided the development of the NWRR construct and measure, helping to explicate the three personal resources required to redirect attention back to nonwork life—behaviors, cognitions, and emotions.

Inhibitory control may appear via self-control (or response inhibition), which involves staying on task despite distractions, thereby allowing one to behaviorally and mentally re-engage in the original nonwork task post-intrusion. It may also appear via interference control which includes suppressing concerns related to external stimuli, especially if unwanted, and the ability to pivot cognitive and emotional resources away from what was previously relevant (i.e., work-related intrusions). Hence, interference control allows individuals to suppress work-related concerns post-intrusion, thereby redirecting cognitive and emotional resources and smoothing the way for re-engagement in nonwork tasks. As self-control and interference control can vary across individuals (Diamond, 2013), we conceptualize NWRR as a personal capacity. Further, given the three resource components of the underlying executive control functions, we conceptualize NWRR as multi-dimensional. Behavioral and cognitive resources are expected to be redirected via self-control, which involves the ability to behaviorally and mentally re-engage in nonwork tasks post-intrusion. Cognitive and emotional resources are expected to be redirected via interference control, which represents the ability to regain focus on nonwork tasks and suppress intrusion-related concerns or worries, thus emotionally reconnecting with nonwork life.

NWRR is a unique and important construct for studying the aftermath of work-related intrusions. NWRR is distinct from mindfulness, a self-regulatory construct that involves being receptively attentive to, aware of, and focused on present experiences (Brown & Ryan, 2003), and may serve as a cognitive-emotional segmentation strategy (Michel et al., 2014) that enhances the ability to remain present. However, mindfulness does not address active and intentional recovery after attention resource fracture. Therefore, mindfulness and NWRR are distinct self-regulatory constructs, both useful for boundary management, yet for different parts of the process. Likewise, NWRR is also distinct from psychological detachment, a boundary management construct that addresses disengaging oneself mentally from work (Sonnentag & Bayer, 2005). Psychological detachment is broader than NWRR because it is not dependent on work-related intrusions. Individuals may desire to disengage from work for various reasons and at various times (e.g., when commuting home), regardless of whether they experience work-related intrusions. Detachment is also more limited because it focuses on disengagement but not re-engagement—and also does not address behavior.

The Present Research

The goal of the present study is to develop and validate a measure of nonwork role re-engagement (NWRR), so as to offer a focused self-regulatory construct that addresses a specific phase of the interrole transition process. Additionally, the present study was designed to demonstrate NWRR’s utility by testing its relationship with meaningful outcomes, above and beyond existing similar self-regulatory and boundary management constructs. Operationalization of and provision of a measurement tool for NWRR adds value to the work-life literature such that it can assess the extent to which individuals’ nonwork lives are fractured by work-related intrusions and their capacity to transition back to nonwork life. Further, NWRR may help explain why individuals are negatively impacted by work-related intrusions.

To create the new measure, we follow collective best practices for scale development and evaluation (Hinkin, 1998; Worthington & Whittaker, 2006; Wright et al., 2017). First, we generated and refined a pool of items associated with the three types of attentional resources (behavioral, cognitive, and emotional) hypothesized as necessary for inhibitory control. Then, we conducted studies with two different samples to verify the factor structure and validate and establish the nomological network (Cronbach & Meehl, 1955) of the newly developed NWRR measure. To develop the nomological network, we examined criterion-related, convergent, and discriminant validity of the scale, with our specific hypotheses outlined below.

Criterion-Related Validity

Criterion-related validity was tested by examining the relationships of NWRR with the following meaningful work and nonwork outcomes. Attending to work-related intrusions and then fully disengaging from intrusions to re-engage in nonwork life is an effortful process consuming executive control resources. Individuals with the ability to redirect their attentional resources back to nonwork tasks following intrusions are likely to experience better well-being and hold more positive work attitudes than those lacking this attentional agility.

Regarding well-being, we believe NWRR can help reduce feelings of work-to-nonwork conflict (WLC), which occurs when the demands of the work role and nonwork roles compete (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985). When work intrudes on nonwork time, individuals may feel they have inadequate time and emotional resources to meet their nonwork obligations, thereby contributing to time-based and strain-based WLC. In support of this premise, boundary violations at home (i.e., work-related intrusions) and transitioning between different life roles have been associated with WLC (Carlson et al., 2015; Hunter et al., 2019). Following intrusions from work, re-engagement in nonwork tasks may help reduce feelings of inadequate resources to meet nonwork obligations, thereby perceiving a lower threat to their nonwork roles (Carlson et al., 2015; Hunter et al., 2019).

Work-related intrusions are stressors that require a continual investment of personal resources to the work role, which may also lead to feelings of job burnout (e.g., Lin et al., 2013). Emotional exhaustion is the aspect of burnout most relevant to the present study. Individuals who are emotionally exhausted feel overextended because of intensive physical, affective, and cognitive strain (Maslach et al., 2001). Underscoring this reasoning, after-hours work-related interruptions and a lack of psychological detachment from work have been associated with emotional exhaustion (Chen & Karahanna, 2018; Sonnentag & Fritz, 2007; Sonnentag et al., 2010). Thus, individuals who have the capability to fully re-engage in their nonwork roles following intrusions may be able to better conserve their attentional resources for nonwork life and thus be less prone to feeling overextended and strained.

-

Hypothesis 1: NWRR negatively relates to (a) time-based WLC, (b) strain-based WLC, and (c) emotional exhaustion.

The benefits of NWRR may extend beyond well-being to positively affect work attitudes, similar to detachment (Shimazu et al., 2016). Yet, NWRR differs from detachment in that it can help individuals not just disengage from work-related intrusions, but also more appropriately allocate the expenditure of personal resources. Feelings of work engagement are highly dependent on the amount of energy, time, and emotional resources one has available to dedicate to the work role. Work-related intrusions may deplete these resources during nonwork hours, leaving fewer resources available for the work day. Yet, NWRR may improve work engagement by conserving these personal resources and thus making them available when needed, i.e., during the work day. Additionally, because NWRR may help individuals feel successful in both work and nonwork roles, it may increase feelings of career satisfaction. Supporting this premise, prior research (e.g., Martins et al., 2002), including a recent meta-analysis (Hoobler et al., 2013), has provided support for a negative relationship between WLC and career satisfaction.

-

Hypothesis 2: NWRR positively relates to (a) work engagement and (b) career satisfaction.

Convergent and Discriminant Validity

Convergent and discriminant validity provide evidence that a construct is related to but also distinct from theoretically relevant constructs. As discussed earlier, we expected NWRR to be positively related to a similar self-regulatory construct—mindfulness—and a similar boundary management construct—psychological detachment.

-

Hypothesis 3: NWRR positively relates to (a) mindfulness and (b) psychological detachment.

Yet we also suspected that NWRR is distinct from the above constructs, based on the previous discussion, and predict that NWRR is related to the well-being and work outcomes discussed earlier, above and beyond mindfulness and psychological detachment. To further demonstrate NWRR’s utility in the work-family literature, we also tested whether NWRR predicts the proposed criterion variables above and beyond existing boundary strength and boundary violation constructs.

First, we suspect NWRR is distinct from two related boundary strength constructs and thus helps enhance well-being and work-related outcomes above and beyond these variables: family flexibility-ability and family flexibility-willingness. When an individual is willing and able to loosen their nonwork (or family) boundaries, they maintain weak boundaries around their personal life, thereby enabling and even provoking work-related intrusions. In contrast, NWRR refers to one’s ability to redirect attentional resources back to nonwork tasks following work-related intrusions. So NWRR is a personal self-regulatory capacity that may help individuals cope with work-related intrusions that result from the existence of weak nonwork boundaries.

We also expect NWRR is a distinct part of the boundary violation process, separate from the experience of work-related intrusions themselves and the subsequent interrole transitioning process they require, and therefore uniquely related to well-being and work outcomes. Work-related intrusions are daily invasive events that accumulate to work-family conflict (Ashforth et al., 2000). Work-related intrusions are likely to trigger inter-domain role switching (i.e., the number of physical and cognitive transitions made from one domain to another; Matthews et al., 2010), such that individuals switch from their nonwork roles/tasks to their work role/tasks. Following the intrusions and upon completion of any ensuing interrole transitions, NWRR is a self-regulatory capacity that may make it possible for individuals to redirect their attentional resources away from intrusions and back toward the original nonwork tasks.

In summary, we examined the incremental validity that NWRR accounts for in the examined criterion variables above and beyond mindfulness, psychological detachment, two boundary strength constructs (family flexibility-ability and family flexibility-willingness; Matthews et al., 2010) and two boundary violation constructs (work-related intrusions and nonwork-to-work role transitions; Matthews et al., 2010). This test also provides evidence for discriminant validity.

-

Hypothesis 4: NWRR will account for variance above and beyond that of mindfulness, psychological detachment, family flexibility-ability, family flexibility-willingness, work-related intrusions, and nonwork-to-work role transitions in (a) time-based WLC, (b) strain-based WLC, (c) emotional exhaustion, (d) work engagement, and (e) career satisfaction.

Method

The NWRR scale development and validation process consisted of four phases (e.g., Shockley et al., 2016). In phase 1, our goal was to develop and refine the scale while ensuring adequate coverage of the content domain. First, we generated a pool of items associated with the three types of attentional resources (behavioral, cognitive, and emotional) hypothesized as necessary for inhibitory control. Then, we evaluated the content adequacy of the scale and further reduced the items based on subject matter expert (SME) feedback, a pilot test with a small group of employees, and theoretical meaningfulness. For phase 2, we administrated the refined pool of items to a sample of employees (i.e., sample 1) from a variety of occupations and industries to further reduce the items and verify the factor structure of the newly developed NWRR measure. In phase 3, we administered the NWRR scale to a new sample of employees (i.e., sample 2) with the goal of verifying the factor structure with a different sample from that used in phase 2. Finally, the goal of phase 4 was to test for validity and develop the nomological network of variables surrounding NWRR using samples 1 and 2.

Phase 1: Item Development and Refinement

Item Pool Development

We took a deductive approach to item generation (Hinkin, 1998) based on principles of content coverage and aiming to avoid construct deficiency (and, later, construct saturation). Adopting a self-regulatory perspective, we provide theoretical justification for each item based on alignment with the three attentional resources required for the core executive function of inhibitory control—the ability to control one’s behavior, thoughts, or emotions to override external stimuli (Diamond, 2013). When developing items, we were cognizant that intrusions vary and that situational circumstances may influence NWRR. However, as the present research is focused on the development and validation of a new construct and measure, we generated items that could assess NWRR by asking about individuals’ general ability to re-engage in nonwork tasks following work-related intrusions. Thus, the following lead-in preceded each item (with slight variations in wording depending on the item): “Following an intrusion from work during my nonwork hours, I am typically able to….” We generated a pool of 31 items to assess the extent to which one is typically able to redirect behaviors, cognitive resources (e.g., thoughts), and emotions back to nonwork tasks following intrusions from work.

The first group of items covered behavioral resources, representing the extent to which individuals possess behavioral self-control such that, following work-related intrusions, they can redirect their behaviors and physical resources away from the intrusions thereby allowing re-engagement in the original nonwork tasks. The items assessed a general ability to switch from work-related intrusions back to the original nonwork tasks and the ability resume the nonwork tasks, particularly at the same point from which the task was interrupted.

The second group of items covered emotional resources. A subset of these items represented the extent to which individuals possesses interference control such that, following work-related intrusions, they can suppress intrusion-related worries thereby redirecting emotional resources back to nonwork tasks. Another subset of these items represented the extent to which individuals possess emotional self-control such that, following work-related intrusions, they can redirect emotions in the service of controlling their behavior, allowing re-engagement in original nonwork tasks. The items assessed a general ability to emotionally detach from work-related intrusions and emotionally reconnect with nonwork life post-intrusion.

The third group of items covered cognitive resources, representing the extent to which individuals possess interference control such that, following work-related intrusions, they can pivot attentional resources away from intrusions and suppress intrusion-related concerns, thereby redirecting cognitive resources and smoothing the way for re-engagement in nonwork tasks. A subset of items assessed a general ability to mentally disengage from work-related intrusions and regain focus on nonwork tasks. A second subset of items assessed the extent to which one is able to re-focus on nonwork tasks without being preoccupied with intrusions.

Item Refinement

Adopting the approach recommended by Anderson and Gerbing (1991), five SMEs unaffiliated with the study reviewed the conceptual definition of NWRR and each proposed dimension (behavioral, cognitive, emotional). Item decisions were based on substantive agreement, substantive validity, and item clarity ratings, as well as qualitative feedback regarding the extent to which an item aligned with the conceptual definition of NWRR, item redundancy, and poor wording (vague, too lengthy, etc.). Substantive agreement (SA) represents the proportion of raters assigning an item to its intended dimension. Items were considered valid and were retained with 75% rater agreement. Substantive validity (SV) represents the extent to which raters assign an item to its intended dimension more than to any other dimension, with higher scores representing higher SV. All items were retained based on these results. SMEs also rated the clarity of each item (1 = very unclear to 4 = very clear). Items with a mean clarity > 3 were retained. One item was removed based on this standard. We deleted eight items based on SME qualitative feedback—seven items that seemed to measure emotional reactions to intrusions rather than emotional reconnection to nonwork tasks, and one item measuring the decision of which task (work vs. nonwork) to focus on post-intrusion, rather than re-engagement in the original nonwork task.

To further test for item clarity, we ran a pilot test with ten full-time salaried employees who frequently experience work-related intrusions. Participants rated each item on clarity using a seven-point scale (1 = very unclear to 7 = very clear) as well as offering open-ended feedback on each item. Items with average clarity ratings > 5 were retained. All items met this standard.

Following the content validity procedures, we reviewed the remaining 22 items for clarity, item redundancy, theoretical meaningfulness, and representation of the content domain. From a content perspective, we retained items measuring the discrete process of re-engaging in nonwork tasks following intrusions from work, items aligning with the two underlying self-regulatory processes of inhibitory control—self-control and interference control (Diamond, 2013), and items aligned with one of the three attentional resources (behavioral, cognitive, or emotional) required for inhibitory control. For redundant items, we kept items that best captured the specific behavioral, cognitive, and emotional processes of re-engaging in nonwork tasks following work-related intrusions. Thus, it was critical that the item referenced the original nonwork tasks. Additionally, among redundant items we retained items capturing deep cognitive and/or emotional engrossment with work-related intrusions that may prevent redirection of attentional resources back to nonwork tasks. Thus, we were more interested in entrenched preoccupation with intrusions rather than merely thinking about intrusions or feeling distracted by intrusions. Based on these criteria, we removed 12 items, with 10 items remaining at the end of phase 1.

Phases 2–4: Scale Refinement and Validation Process

To refine and validate our new measure, we collected two samples of survey data from working adults, with phase 2 based on sample 1, phase 3 based on sample 2, and phase 4 based on samples 1 and 2. The NWRR scale and validation measures were administered to each sample. In phase 2, we conducted factor analysis with sample 1 data to further refine the new NWRR measure and establish whether the three proposed dimensions were empirically distinct subscales. In phase 3, we verified the scale factor structure using confirmatory factor analysis with sample 2 data. For phase 4, we used sample 1 and 2 data to examine whether NWRR is a personal capacity that varies across persons and test for criterion, convergent, and discriminant validity, thereby helping to develop the nomological network of variables surrounding NWRR.

Participants and Procedures

Participants from sample 1 were working adults recruited using Mechanical Turk (MTurk). All participants met MTurk’s “master qualification,” a system-assigned designation for high-quality respondents (see Cheung et al., 2017). Participants also had to pass supplemental screener questions to determine their eligibility (full-time non-MTurk job, working only one job). We excluded employees whose experiences with intrusions might be atypical, including those working from home > 1 day/week, small business owners, and self-employed, temporary, or contract workers. Participants were compensated 2 USD. We received surveys from 202 respondents; 14 were removed due to widespread missing data.

Sample 1 (N = 188) was predominantly male (62%), Caucasian (73%) and college-educated (66%), with a mean age of 38 years (SD = 10.8). Forty-six percent were married, and the majority had no children (65%). They worked in a variety of industries, had an average tenure of 8 years (SD = 7.04), worked an average of 42 h/week (SD = 4.09), and 53% were in managerial roles. Seventy-six percent (n = 146) agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, “I consider being contacted by my job during my nonwork hours as an intrusion into my personal life,” suggesting that the NWRR construct is relevant and its measurement is valuable to understanding attentional challenges in the aftermath of work-related intrusions.

Sample 2 participants were working adults recruited using Prolific. The same demographic questions were asked in a Qualtrics screening survey to filter out ineligible participants. However, as the data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic, participants were required to have worked at home < 2 days/week prior to the onset of the pandemic. Only those who met basic eligibility criteria (full-time workers, age > 22, living in the USA) were able to see the post for the screening survey. Of the 600 Prolific users who responded to the screening survey, 324 were deemed eligible and invited to the main study. Of those, 274 provided complete data (response rate of 84.6%). None of the respondents failed both attention check questions. Seven respondents were removed because they were considered “speeders,” and three were removed because they were not full-time workers based on their self-reported weekly work hours. Thus, complete data for sample 2 were collected from 264 respondents.

Forty-six percent of sample 2 was female, with an average age of 34 (SD = 8.4). Most were Caucasian (75%), married (55%), and had a spouse/partner working full-time (68%). Forty-three percent had children living at home. They worked in a variety of industries, 55% were managers, average organizational tenure was 5.7 years (SD = 5.6), and they worked an average of 42 h/week (SD = 5.5). As expected, although all respondents were working from home < 2 days/week prior to COVID-related mandates to work from home, more than 50% worked from home five days/week (M = 3.5, SD = 2.2) at the time of the study (during the pandemic). Eighty-three percent reported after-hours job contacts at least a couple of times a week; thus, most were likely to experience work-related intrusions—and for 41% of respondents, these after-hours job contacts were more frequent compared to pre-COVID period. Also, 68% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, “I consider being contacted by my job during my nonwork hours as an intrusion into my personal life,” further attesting to the value and relevance of considering and measuring NWRR.

Measures

A five-point Likert scale was used for all measures (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) unless otherwise noted. Reliability coefficients for all measures are listed in Table 3.

The nonwork role re-engagement items developed for this study were administered to samples 1 and 2. The ten items retained from phase 1 were administered to sample 1. The final 8-item version of the scale was administered to sample 2 (the process of reducing the ten items to eight is described below). Three example items are as follows (stem: “Following an intrusion from work during my nonwork hours, I am typically able to”): (1) resume the personal task/activity I was involved in prior to the intrusion, (2) regain focus on the personal task/activity I was involved in prior to the intrusion, and (3) emotionally detach from the intrusion in order to resume the nonwork task/activity I was involved in prior to the intrusion.

For the criterion-related validity measures, work-to-life conflict (WLC) was assessed with the same measures in samples 1 and 2. All other criterion measures were measured in sample 2 only. WLC was assessed with Carlson et al.’s (2000) three-item measure of time-based WLC (e.g., “My work keeps me from my family/personal activities more than I would like”) and three-item measure of strain-based WLC (e.g., “Due to all the pressures at work, sometimes when I come home I am too stressed to do the things I enjoy”). With an eye toward parsimony, emotional exhaustion was assessed with the 3-item shortened OLBI (sample item, “After my work, I usually feel worn out and weary”, Thanacoody et al., 2014), and work engagement was measured with a 3-item scale (sample item, “I am immersed in my work”; Matthews et al., 2020). Career satisfaction was assessed with four items (e.g., “I am satisfied with the progress I have made toward meeting my career goals”; Greenhaus et al., 1990).

The convergent validity measures—mindfulness and psychological detachment—were assessed in samples 1 and 2. For mindfulness, in sample 1 we used Brown and Ryan’s (2003) 12-item mindfulness measure (e.g., “I find it difficult to stay focused on what’s happening in the present”). For sample 2, with an eye toward parsimony, we used a shortened 5-item version of Brown and Ryan’s measure focused on attentional awareness (Höfling et al., 2011). Psychological detachment was measured in both samples with a four-item scale from Sonnentag and Fritz’s (2007) Recovery Experience Questionnaire (e.g., “I distance myself from my work”).

All other discriminant validity measures were assessed in sample 2. To measure the flexibility of nonwork boundaries, we adapted Matthews et al.’s (2010) 5-item family flexibility-ability scale (e.g., “If the need arose, I could work late without affecting my family and personal responsibilities”) and three items from their family flexibility-willingness scale (e.g., “I am willing to change plans with my friends and family so that I can finish a job assignment”). We measured work-related intrusions with one item (“Intrusions from work during my nonwork hours impede on my personal life”). To measure nonwork-to-work role transitions, we adapted three items from the family-to-work transition scale (e.g., “How often in the past three months have you changed plans with your family to meet work-related responsibilities?”; 0 = never to 5 = 5 or more days per week; Matthews et al., 2010).

Our test of common method variance in sample 2 included a marker and a measured cause variable as recommended as best practice (Williams & McGonagle, 2016). The marker variable was community satisfaction (“In general, I am satisfied with my community, e.g., the city, town, or place where I live”; Toth et al., 2002). The measured cause variable was adapted from the abbreviated PANAS (Thompson, 2007; Watson et al., 1988), which includes five negative affective items: upset, hostile, ashamed, nervous, afraid. Given the COVID-19 climate at the time of the study, we added “distressed” as a sixth item (e.g., “Indicate the extent you have felt this way during the past 30 days: distressed”; 1 = very slightly or not at all to 5 = extremely).

Results

Phase 2 Results

We took a multi-step approach to item reduction and establishment of a factor structure for our newly developed NWRR measure. First, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (p < 0.001) both suggested that the NWRR measure could be factor analyzed. Then, we used parallel analysis (PA) to help make factor retention decisions (Hayton et al., 2004; O’Connor, 2000). Lastly, we used exploratory factor analysis (EFA) for item loading determinations using maximum likelihood estimation and direct oblimin rotation, as factors were expected to be correlated.

Using a random half of sample 1 data (n = 94), the first stage of factor analysis was conducted on the ten NWRR items. Both statistical and theoretical reasoning guided our item retention decisions, with the objective of identifying the items most clearly representative of the content domain for NWRR. For factor loading decisions, we applied the commonly used cutoff of 0.40 (Ford et al., 1986). Additionally, high item communalities are considered important for determining factor structure and evaluating items for retention, as communality represents the proportion of item variance accounted for by the factors (Hinkin, 1998; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001). Items with low communalities (< 0.40) were considered not highly correlated with one or more of the factors in the solution (Worthington & Whittaker, 2006). From a theoretical perspective, we ensured the remaining items covered the content domain such that all three hypothesized attentional resources were covered and all remaining items were representative of NWRR’s underlying executive control function of inhibitory control (Diamond, 2013).

PA revealed only one factor (see Table 1), and EFA eigenvalues and rotated factor loadings suggested one factor explaining 68% of total item variance and item loadings ranging from 0.587 to 0.924 (see Table 2). Based on EFA results, we removed two items with communality scores below the recommended cutoff, and these two items also had the lowest factor loadings. The remaining eight items still adequately covered the content domain for NWRR.

Using the second half of sample 1 data (n = 94), we repeated the factor analysis with the eight items to ensure a clear factor structure matrix explaining a high percentage of total item variance (Hinkin, 1998). PA suggested a one-factor solution (see Table 1), and EFA eigenvalues and rotated factor loadings suggested a one-factor solution, explaining 79% of total item variance and with loadings ranging from 0.722 to 0.972 (see Table 2). All eight items were retained.

Although the remaining items still cover the three originally hypothesized attentional resources, a one-factor solution suggests that inhibitory control is the critical executive control function that gives individuals the capacity to redirect various attentional resources so they may re-engage in nonwork tasks following work-related intrusions. Moreover, the two underlying self-regulatory process of inhibitory control—self-control and interference control—are adequately covered by the eight remaining items.

Phase 3 Results

In phase 3, we verified the one-factor structure of the 8-item NWRR scale in sample 2 (N = 264) using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in AMOS. The λ values for all items exceeded the recommended cutoff of 0.40 (Hair et al., 1998), ranging from 0.614 to 0.912, and significantly loaded onto the factor (p < 0.001). As recommended (Djurdjevic et al., 2017; Hu & Bentler, 1999), we examined how well the one-factor structure fit our data using the comparative fit index (CFI) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; CFI = 0.930, RMSEA = 0.159). The CFI value meets Kline’s (2005) criteria (> 0.90). While the RMSEA value falls outside of Kline’s recommended range (0.05–0.08), this is likely due to sample size and model complexity, as opposed to model misspecification or flawed data (Hu & Bentler, 1998; Lai & Green, 2016). Moreover, consistent with best practice recommendations (e.g., Kline, 2010), we considered the goodness of fit indices holistically, rather than relying on one single index or combinatorial rule to determine acceptable fit. Given the CFI value indicated good fit and the RMSEA value is likely influenced by our relatively small sample and small number of variables (Fan & Sivo, 2007; Kenny & McCoach, 2003; Kenny et al., 2015; Nye & Drasgow, 2011), we concluded the model has acceptable fit. We also confirmed that the one negatively worded item (“…too preoccupied to concentrate on the personal task/activity I was involved in prior to the intrusion”) was carefully worded so as to assure appropriate interpretation by respondents, as recommended by Hinkin (1998). Moreover, the factor loading and communality value for this item were both above the recommended cutoff (0.40). The final scale items are listed in the Appendix.Footnote 1

Rather than being differentiated by the type of attentional resources required to re-engage in nonwork tasks, the unidimensional NWRR construct represents a single core executive function—inhibitory control—with the final scale items adequately representing the two self-regulatory processes underlying inhibitory control, for which more than one type of attentional resource may be responsible: Self-control (i.e., response inhibition)—the ability to re-engage in the original nonwork tasks despite work-related intrusions requires behavioral and/or cognitive resources, and interference control—the ability to suppress concerns related to intrusions and pivot attentional resources back to nonwork tasks requires cognitive and/or emotional resources.

Phase 4 Results

We tested validity and developed the nomological net for NWRR using samples 1 and 2. See Table 3 for intercorrelations and Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients for all validation measures. In regards to our conceptualization of NWRR as a personal capacity, results generally suggest NWRR is an individual trait that varies across persons and is not necessarily related to specific situational factors. Based on data from samples 1 and 2, NWRR was not significantly related to parental status (t = − 0.026, ns and t = 0.742, ns, samples 1 and 2 respectively), management status (t = − 0.418, ns and t = 1.027, ns, samples 1 and 2 respectively), work hours (r = − 0.114, ns and r = − 0.098, ns, samples 1 and 2 respectively) or age (r = 0.065, ns and r = 0.053, ns, samples 1 and 2 respectively). NWRR did not differ by gender in sample 1 (t = − 0.733, ns), but did differ by gender in sample 2 (t = 2.193, p = 0.029) with men reporting higher NWRR. This difference may reflect an effect of men in sample 2 having significantly higher mindfulness (t = 3.09, p = 0.002) or the widely reported gendered impact of the COVID-19 pandemic fallout on women’s work and home responsibilities and support systems (e.g., BetterUp, 2020). Indeed, women in sample 2 reported significantly higher strain-based WLC (t = − 3.408, p = 0.001) and emotional exhaustion (t = − 4.299, p < 0.001).

Bivariate correlations evidenced criterion-related validity, supporting H1 and H2. NWRR was negatively related to time-based WLC (r = − 0.46, − 0.36, p < 0.001, samples 1 and 2 respectively), strain-based WLC (r = − 0.51, − 0.46, p < 0.001, samples 1 and 2 respectively), and emotional exhaustion (r = − 0.46, p < 0.001, sample 2). NWRR was positively related to work engagement (r = 0.26, p < 0.001, sample 2) and career satisfaction (r = 0.21, p < 0.001, sample 2).Footnote 2Bivariate correlations also evidenced convergent validity with mindfulness and psychological detachment in samples 1 and 2, fully supporting H3. NWRR was positively related to mindfulness (r = 0.27, 0.21, p < 0.001, samples 1 and 2 respectively) and psychological detachment (r = 0.40, 0.37, p < 0.001, samples 1 and 2 respectively).

To test hypothesis 4, we examined the incremental validity of NWRR above and beyond mindfulness, psychological detachment, two boundary strength variables (family flexibility-ability and family flexibility-willingness), and two boundary violation variables (work-related intrusions and nonwork-to-work role transitions). Hierarchical regression models were estimated for each outcome. Significance was based on changes in R2 from step one where all convergent validity variables were included to step two where NWRR was added to the model. We found full support for H4, with changes in R2 ranging from 0.02 to 0.07 (see Table 4). Model 1 shows that NWRR displayed significant incremental effects on time-based WLC (β = − 0.15, p = 0.017, ΔR2 = 0.02), strain-based WLC (β = − 0.25, p < 0.001, ΔR2 = 0.05), emotional exhaustion (β = − 0.32, p < 0.001, ΔR2 = 0.07), work engagement (β = 0.24, p < 0.001, ΔR2 = 0.04), and career satisfaction (β = 0.15, p = 0.031, ΔR2 = 0.02), above and beyond existing self-regulatory and boundary management constructs as indicated by significant changes in R2.

Common Method Variance

To test for common method variance (CMV) and its potential biasing effects in sample 1, we conducted CFAs using the unmeasured latent method factor approach (Williams & McGonagle, 2016). After evaluating a five-factor measurement model (with NWRR, time-based WLC, strain-based WLC, mindfulness, and psychological detachment) and establishing acceptable fit (CFI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.07), we added an orthogonal latent common method factor (CMF) to the basic measurement model to test for presence and equality of method effects. The CMF accounted for an average of 26.57% of the variance in the substantive indicators, which is just above the recommended median amount of method variance (25%; Williams et al., 1989) and well below the cut-off of 70% (Fuller et al., 2016).

To test for CMV in sample 2, we followed two recommended approaches (Williams & McGonagle, 2016) to improve on the limitations of the unmeasured latent construct approach. The marker variable approach involves an indirect measure of the variable presumed to underlie the CMV. We selected community satisfaction as our marker variable as it may capture sources of CMV related to affect-driven response tendencies likely to impact NWRR measurement (and other substantive variables in the present study, e.g., WLC), but does not directly measure this response tendency. The measured cause variable approach helps detect direct sources of method effects by including the measurement of a method latent variable presumed to be a source of CMV (Simmering et al., 2015). Negative affect is a potential source of CMV that, if present, should be controlled for in the present study, as NWRR has an affective component and we assessed affect-based outcomes (e.g., emotional exhaustion, career satisfaction).

We evaluated the full 12-factor measurement model (NWRR, five criterion-validity variables, and six discriminant validity variables) and established good fit (CFI = 0.902, RMSEA = 0.055). Then, we estimated two additional measurement models with the addition of the method variables. In the first model, we added community satisfaction as the marker variable, and in the second model we added negative affect as the measured cause variable. In each respective model, the method latent variable was linked to all of the study indicators, but was not allowed to correlate with the substantive latent variables. The marker method factor accounted for an average of 2.69% of the variance in the substantive indicators, and the measured cause factor accounted for an average of 9.47% of the variance in the substantive indicators, which are below the recommended cut-off (25%; Williams et al., 1989). These findings indicate CMV had little effect on our validity tests.

Discussion

The changing nature of work, combined with a national shift in ways of work in response to COVID-19, undoubtedly requires employees to be agile with their attentional resources, as an “always on” mentality causes work to bleed irrevocably into most employees’ personal lives, necessitating frequent crossing between increasingly blurred work-life boundaries (Cooper & Lu, 2019). Work-related intrusions require micro-role transitions, thus the ability to switch attentional gears will be a critical capacity for navigating today’s demanding and complex work-life interface and for thwarting negative impacts of role transitions on well-being and work attitudes. We developed a psychometrically and theoretically sound unidimensional measure of nonwork role re-engagement (NWRR), which can be utilized by work-family scholars in future boundary management studies. Additionally, the present research suggests NWRR is a unique, important and useful construct, as we provided evidence of criterion-related, convergent, and discriminant validity for our new measure with two different samples of employees. We did not find support for the originally proposed three-dimensional structure focused on the three types of attentional resources being redirected. Instead, the unidimensional structure suggests that inhibitory control is the single critical feature of NWRR with the two underlying self-regulatory functions of self-control and interference control enabling individuals to redirect various attentional resources.

Our findings suggest that NWRR can help improve well-being as well as attitudes toward work and careers, above and beyond existing similar self-regulatory and boundary management contracts. Thus, lacking NWRR may potentially explain why work-related intrusions negatively impact well-being and work attitudes, while possessing NWRR may help individuals thwart any negative consequences. Our results suggest that it may be both restorative and professionally satisfying when you can pick up where you left off and mentally and emotionally plunge back into your nonwork life following intrusions from work. Reconnecting to nonwork life behaviorally, mentally, and emotionally may allow individuals to truly disengage from work-related intrusions, thereby reducing feelings of conflict between work and nonwork life, helping to restore mental and emotional energy for work and leisure, and generating positive feelings toward one’s career. Our convergent validity evidence for mindfulness and psychological detachment suggests that NWRR may serve as a self-regulatory process that enhances the ability to actively and intentionally recover after attention resource fracture, ultimately helping individuals detach form work demands during nonwork hours and thereby potentially helping them perform well at work (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2015; Sonnentag et al., 2010).

Theoretical Implications

Answering Allen et al.’s (2014) call for the incorporation of a self-regulation approach into boundary research, we apply theories and concepts from the cognitive psychology literature to contribute to boundary theory and the work-family literature with the development of a construct that clarifies an important and underdeveloped stage of the boundary management process. NWRR helps explain the extent to which individuals are capable of redirecting behaviors, mindsets, and emotions back to nonwork tasks following work-related intrusions and overriding any attention residue from the intruding work tasks on the original nonwork tasks. An improved understanding of the underlying processes involved in the micro-role transitions that follow work-related intrusions can help explain why boundary violations negatively affect employees and how individuals can circumvent these negative consequences. The underlying self-regulatory processes of self-control and interference control can help individuals redirect attentional resources post-intrusion, thereby overcoming attention deficits and potentially enhancing well-being and work outcomes. Thus, a major implication of our research is providing a new and important measure that can be utilized by work-family scholars. Additionally, our findings suggest that future studies examining the outcomes of work-related intrusions should include NWRR as a potential mediator or moderator in these relationships to better understand how intrusions translate into adverse versus positive outcomes for employees.

Our results support attention residue theory and the depletion effect, suggesting that an act of self-regulation—re-engaging in a nonwork task following an interrupting work task—relies on redirecting limited attentional resources, countering claims and evidence that the depletion effects does not exist for acts of self-control (Carter et al., 2015; Carter & McCullough, 2013, 2014; Dang, 2018; Lurquin et al., 2016). One explanation for why our results differed from prior studies is perhaps because we focused on interruptions that require abrupt task switching across very different life domains (work and personal life), which necessitates shifting between different behaviors, mindsets, and emotions, rather than sequential tasks within one life domain (e.g., work). Thus, task switching back and forth across different life domains may be a critical feature that can deplete attentional resources and therefore require the executive functions of inhibitory control. Our results are supported by Hamilton et al. (2011) who found that switching mindsets consumes self-regulatory resources.

We further build on boundary management theory by identifying outcomes of NWRR, implying that the redirection of resources back to nonwork tasks can enhance well-being and work attitudes. These results build on Hamilton et al.’s (2011) research by showing that there are beneficial effects to being able to shift not only mindsets but also behaviors when trying to accommodate work-related intrusions during personal time. Our findings also expand attention residue theory (Leroy, 2009), which focused on how attention residue from different work tasks within the work domain negatively affects work performance (Leroy & Schmidt, 2016). We showed that a reduction of attention residue from work tasks intruding into nonwork domains benefits employee well-being.

Practical Implications

Although we conceptualized NWRR as a personal capacity, we recognize that is a dynamic trait that can be enhanced with training and practice. Because NWRR was linked to important well-being and work outcomes over and above existing self-regulatory and boundary management strategies, we suggest that NWRR can serve as a boundary management strategy that may benefit both employees and organizations. Organizations should help employees boost their inhibitory control so that they possess the attentional agility to transition away from work-related intrusions and seamlessly return to their personal lives, when needed or desired. Training should be designed to enhance both self-control and interference control among employees who frequently experience work-related intrusions, as these self-regulatory abilities can help improve work attitudes and well-being in the aftermath of intrusions. Improving self-awareness may be a viable avenue, as mindfulness was positively related to NWRR and can serve as cognitive-segmentation strategy and form of attentional control (Allen & Paddock, 2015; Bond et al., 2006; Michel et al., 2014). Thus, mindfulness training may help employees at least notice when they need to redirect attention back to nonwork tasks and become mentally and emotionally absorbed again in their nonwork life (e.g., return to caring for your child and reconnect with your child).

Our results countered claims and evidence that the depletion effect does not exist for acts of self-control, with the ability to re-engage in nonwork tasks following interrupting work tasks relying on the redirection of limited attentional resources. Therefore, we recommend that organizations and managers lean on strategies to build employees’ self-regulation capacities and reserves of executive control resources so as to improve their ability for re-engaging in nonwork life. Indeed, Kossek and Perrigino (2016) argued that supervisors play a critical role in creating a supportive work-family environment, positioning supervisors as an important resource for employees who are bombarded with work-related intrusions. Managers, and even co-workers, can be trained on after-hours communications (Boswell et al., 2016), which may help employees reserve executive control resources. For example, to the extent possible, intrusions during nonwork hours should be limited to only the most critical matters, such as work-related demands that are ubiquitously perceived as legitimate. If intrusions are limited to only the most legitimate issues, employees may have the attentional resource capacity to attend to such intrusions and then still successfully switch back to nonwork life.

Limitations and Future Research Agenda

An important limitation in the present study was the use of online sampling. Although there are concerns with online respondent pools (Porter et al., 2019), we used recommended cautions (e.g., attention checks) and screeners (see Cheung et al., 2017) which generally yield diverse samples representative of typical working adults (Crone & Williams, 2017; Goodman & Paolacci, 2017; Peer et al., 2017). MTurk can yield high-quality data with comparable reliability to traditional methods (Buhrmester et al., 2011; Walter et al., 2019), making it appropriate for scale development purposes in particular (Porter et al., 2019; Walter et al., 2019).

The survey design warrants consideration of the potential for common method variance (CMV). However, NWRR is inherently internal to individuals, based on perception and internal attention, thoughts, and feelings and thus self-report is most appropriate (Conway & Lance, 2010). Although others (e.g., partners) may be present at the time of work-related intrusions, it is the target individual who can provide the best estimate of their level of re-engagement. On the back end, our tests of CMV as well as varied strength and significance of correlations indicated that CMV was unlikely. Still, future research on NWRR may benefit from including spouse and child perceptions to study marital, family, and child outcomes.

The cross-sectional nature of our research precludes determinations of causality. Future research should measure NWRR longitudinally so as to allow for consideration of time lags between predictors, intrusions, and outcomes. Future research should also address the need for more event-contingent study designs that further expand understanding of in-the-moment work-family experiences (Allen & Martin, 2017). We consider NWRR as a dynamic self-regulatory capacity relevant to a triggering intrusion event. Because each intrusion is unique, NWRR is likely dynamic to some extent, depending upon the employee’s holistic appraisal of the intrusion’s collective characteristics, among other contextual variables (e.g., the nonwork activity being interrupted). Further, to determine any constraints on generalizability, future research could explore whether NWRR differs for permanently remote employees, as remote arrangements are rapidly becoming common with the acceleration of digital transformation resulting from COVID-19, Finally, predictors of NWRR and boundary conditions such as role segmentation preferences, after-hours availability pressure, or excessive availability for work (Cooper & Lu, 2019) should be explored.

Conclusion

The workscape continues to shift toward evermore blurred boundaries between work and nonwork domains, particularly in the context of the recent COVID-19 pandemic. With this, work-related intrusions are increasingly ubiquitous, and the need for organizations and individuals alike to understand the skills and abilities necessary to make such conditions successful is more important than ever. Grounded in a self-regulatory approach and the executive control resources therein, this work contributes to boundary management theory by introducing the concept of nonwork role re-engagement (NWRR), and developing and validating a psychometrically sound unidimensional measure of this individual capability. As we move into a new era of work, NWRR offers important predictive validity for employee well-being as well as for outcomes of concern to organizations.

Notes

For the final 8-item NWRR scale, users may consider slightly rewording the lead-in and item text so the same lead-in text can be used for all eight items (“Following an intrusion from work during my nonwork hours, I am typically…”).

To rule out the alternative explanation that the outcome variables predict NWRR, we used data from sample 2 to regress NWRR on all outcome variables simultaneously. Time-based WLC was related to NWRR (β = − .17, p = .013), but strain-based WLC was not (β = − .11, p = .267). Emotional exhaustion was related to NWRR (β = − .27, p = .002), but the coefficient was weaker than when tested as an outcome. Career satisfaction and work engagement were not related to NWRR (β = .08, p = .271, β = .05, p = .441). To provide further support that NWRR can positively impact well-being, we examined the correlations of both forms of WLC and emotional exhaustion with the intrusion impediment item (“Intrusions from work during my nonwork hours impede on my personal life”) using data from sample 2. The impediment item was positively correlated with time-based WLC, strain-based WLC, and emotional exhaustion (r = .369, r = .362, r = .353, p < .01, p < .01, respectively).

References

Allen, T. D., & Martin, A. (2017). The work-family interface: A retrospective look at 20 years of research in JOHP. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 259.

Allen, T. D., & Paddock, E. L. (2015). How being mindful impacts individuals' work-family balance, conflict, and enrichment: A review of existing evidence, mechanisms and future directions. In J. Reb & P. W. B. Atkins (Eds.), Mindfulness in organizations: Foundations, research, and applications (pp. 213–238). Cambridge University Press.

Allen, T. D., Cho, E., & Meier, L. L. (2014). Work–family boundary dynamics. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 99–121.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1991). Predicting the performance of measures in a confirmatory factor analysis with a pretest assessment of their substantive validities. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 732–740. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.76.5.732

Ashforth, B. E., Kreiner, G. E., & Fugate, M. (2000). All in a day’s work: Boundaries and micro role transitions. Academy of Management Review, 25, 472–491. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2000.3363315

Beal, D. J., Weiss, H. M., Barros, E., & MacDermid, S. M. (2005). An episodic process model of affective influences on performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 1054–1068. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1054

BetterUp. (2020). COVID-19 and the state of the worker.

Bond, F. W., Hayes, S. C., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2006). Psychological flexibility, ACT, and organizational behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 26, 25–54. https://doi.org/10.1300/J075v26n01_02

Boswell, W. R., Olson-Buchanan, J. B., Butts, M. M., & Becker, W. J. (2016). Managing “after hours” electronic work communication. Organizational Dynamics, 45, 291–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2016.10.004

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 822–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822

Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T., & Gosling, S. D. (2011). Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 3–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691610393980

Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., & Williams, L. J. (2000). Construction and initial validation of a multidemensional measure of work-family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 56, 249–276. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1999.1713

Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., Zivnuska, S., & Ferguson, M. (2015). Do the benefits of family-to-work transitions come at too great a cost? Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20, 161–171. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038279

Carter, E. C., Kofler, L. M., Forster, D. E., & McCullough, M. E. (2015). A series of meta-analytic tests of the depletion effect: Self-control does not seem to rely on a limited resource. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 144(4), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000083

Carter, E. C., & McCullough, M. E. (2013). Is ego depletion too incredible? Evidence for the overestimation of the depletion effect. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 36(36), 6.

Carter, E. C., & McCullough, M. E. (2014). Publication bias and the limited strength model of self-control: Has the evidence for ego depletion been overestimated? Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00823

Chen, A., & Karahanna, E. (2018). Life interrupted: The effects of technology-mediated work interruptions on work and nonwork outcomes. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 42, 1023–1042. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2018/13631

Cheung, J. H., Burns, D. K., Sinclair, R. R., & Sliter, M. (2017). Amazon Mechanical Turk in organizational psychology: An evaluation and practical recommendations. Journal of Business and Psychology, 32, 347–361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-016-9458-5

Conway, J. M., & Lance, C. E. (2010). What reviewers should expect from authors regarding common method bias in organizational research. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25, 325–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9181-6

Cooper, C. L., & Lu, L. (2019). Excessive availability for work: Good or bad? Charting underlying motivations and searching for game-changers. Human Resource Management Review. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2019.01.003.

Cronbach, L. J., & Meehl, P. E. (1955). Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin, 52, 281–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0040957

Crone, D. L., & Williams, L. A. (2017). Crowdsourcing participants for psychological research in Australia: A test of microworkers. Australian Journal of Psychology, 69(1), 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12110

Dang, J. (2018). An updated meta-analysis of the ego depletion effect. Psychological Research Psychologische Forschung, 82(4), 645–651.

Demerouti, E., Taris, T. W., & Bakker, A. B. (2007). Need for recovery, home-work interference and performance: Is lack of concentration the link? Journal of Vocational Behavior, 71(2), 204–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2007.06.002

Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135–168. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750

Djurdjevic, E., Stoverink, A. C., Klotz, A. C., Koopman, J., da Motta Veiga, S. P., Yam, K. C., & Chiang, J.T.-J. (2017). Workplace status: The development and validation of a scale. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(7), 1124–1147. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000202

Fan, X., & Sivo, S. A. (2007). Sensitivity of fit indices to model misspecification and model types. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(3), 509–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273170701382864

Ford, J. K., MacCallum, R. C., & Tait, M. (1986). The application of exploratory factor analysis in applied psychology: A critical review and analysis. Personnel Psychology, 39(2), 291–314. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1986.tb00583.x

Fuller, C. M., Simmering, M. J., Atinc, G., Atinc, Y., & Babin, B. J. (2016). Common methods variance detection in business research. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3192–3198.

Goodman, J. K., & Paolacci, G. (2017). Crowdsourcing consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 44(1), 196–210. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucx047

Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources and conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10, 76–88. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1985.4277352

Greenhaus, J. H., Parasuraman, S., & Wormley, W. M. (1990). Effects of race on organizational experiences, job performance evaluations, and career outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 33(1), 64–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/256352

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Factor analysis. In J. F. Hair, R. E. Anderson, R. L. Tatham, & W. C. Black (Eds.), Multivariate Data Analysis (pp. 87–138). Prentice-Hall.

Hamilton, R., Vohs, K. D., Sellier, A.-L., & Meyvis, T. (2011). Being of two minds: Switching mindsets exhausts self-regulatory resources. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 115, 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2010.11.005

Hayton, J. C., Allen, D. G., & Scarpello, V. (2004). Factor retention decisions in exploratory factor analysis: A tutorial on parallel analysis. Organizational Research Methods, 7, 191–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428104263675

Hinkin, T. R. (1998). A brief tutorial on the development of measures for use in survey questionnaires. Organizational Research Methods, 1, 104–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442819800100106

Höfling, V., Moosbrugger, H., Schermelleh-Engel, K., & Heidenreich, T. (2011). Mindfulness or mindlessness? A modified version of the Mindful Attention and Awareness Scale (MAAS). European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 27(1), 59–64. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000045

Hoobler, J. M., Hu, J., & Wilson, M. (2013). Do workers who experience conflict between the work and family domains hit a “glass ceiling?”: A meta-analytic examination. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83, 280–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2013.05.008

Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424–453. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: a Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Hunter, E. M., Clark, M. A., & Carlson, D. S. (2019). Violating work-family boundaries: Reactions to interruptions at work and home. Journal of Management, 45, 1284–1308. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317702221

Kenny, D. A., Kaniskan, B., & McCoach, D. B. (2015). The performance of RMSEA in models with small degrees of freedom. Sociological Methods & Research, 44(3), 486–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124114543236

Kenny, D. A., & McCoach, D. B. (2003). Effect of the number of variables on measures of fit in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling, 10(3), 333–351.

Kline, R. B. (2010). Promise and pitfalls of structural equation modeling in gifted research. In B. Thompson & R. F. Subotnik (Eds.), Methodologies for conducting research on giftedness (pp. 147–169). American Psychological Association.

Kline, T. (2005). Psychological testing: A practical approach to design and evaluation. Sage.

Kossek, E. E., & Perrigino, M. B. (2016). Resilience: A review using a grounded integrated occupational approach. Academy of Management Annals, 10, 729–797. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2016.1159878

Lai, K., & Green, S. B. (2016). The problem with having two watches: Assessment of fit when RMSEA and CFI disagree. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 51(2–3), 220–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2015.1134306

Lapierre, L. M., Hammer, L. B., Truxillo, D. M., & Murphy, L. A. (2012). Family interference with work and workplace cognitive failure: The mitigating role of recovery experiences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 81(2), 227–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.07.007

Leroy, S. (2009). Why is it so hard to do my work? The challenge of attention residue when switching between work tasks. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 109, 168–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2009.04.002

Leroy, S., & Schmidt, A. M. (2016). The effect of regulatory focus on attention residue and performance during interruptions. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 137(218–235). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2016.07.006.

Lin, B. C., Kain, J. M., & Fritz, C. (2013). Don’t interrupt me! An examination of the relationship between intrusions at work and employee strain. International Journal of Stress Management, 20(2), 77–94.

Lurquin, J. H., Michaelson, L. E., Barker, J. E., Gustavson, D. E., von Bastian, C. C., Carruth, N. P., Miyake, A., & Wicherts, J. M. (2016). No evidence of the ego-depletion effect across task characteristics and individual differences: A pre-registered study. Plos One, 11(2), e0147770.

Martins, L. L., Eddelston, K. A., & Veiga, J. F. (2002). Moderators of the relationship between work-family conflict and career satisfaction. Academy of Management Journal, 45(2), 399–409. https://doi.org/10.5465/3069354

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 397–422.

Matthews, R. A., Barnes-Farrell, J. L., & Bulger, C. (2010). Advancing measurement of work and family domain boundary characteristics. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(3), 447–460.

Matthews, R. M., Mills, M. J., & Wise, S. R. (2020). Advancing research and practice through an empirically validated short form measure of work engagement. Occupational Health Science, 4(3), 305–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-020-00071-4.

Michel, A., Bosch, C., & Rexroth, M. (2014). Mindfulness as a cognitive–emotional segmentation strategy: An intervention promoting work–life balance. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 87, 733–754. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12072

Muraven, M., & Baumeister, R. F. (2000). Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: Does self-control resemble a muscle? Psychological Bulletin, 126, 247–259. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.247

Nippert-Eng, C. (1996). Calendars and keys: The classification of “home” and “work.” Sociological Forum, 11, 563–582. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02408393

Nohe, C., Michel, A., & Sonntag, K. (2014). Family–work conflict and job performance: A diary study of boundary conditions and mechanisms. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(3), 339–357. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1878

Nye, C. D., & Drasgow, F. (2011). Assessing goodness of fit: Simple rules of thumb simply do not work. Organizational Research Methods, 14(3), 548–570. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428110368562

O’Connor, B. P. (2000). SPSS and SAS programs for determining the number of components using parallel analysis and Velicer’s MAP test. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 32, 396–402. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03200807

Peer, E., Brandimarte, L., Samat, S., & Acquisti, A. (2017). Beyond the Turk: Alternative platforms for crowdsourcing behavioral research. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 70, 153–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2017.01.006

Piszczek, M. M. (2017). Boundary control and controlled boundaries: Organizational expectations for technology use at the work-family interface. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38, 592–611. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2153

Porter, C. O., Outlaw, R., Gale, J. P., & Cho, T. S. (2019). The use of online panel data in management research: A review and recommendations. Journal of Management, 45(1), 319–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318811569

Shimazu, A., Matsudaira, K., De Jonge, J., Tosaka, N., Watanabe, K., & Takahashi, M. (2016). Psychological detachment from work during non-work time: Linear or curvilinear relations with mental health and work engagement? Industrial Health, 54, 282–292. https://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.2015-0097

Shockley, K. M., Ureksoy, H., Rodopman, O. B., Poteat, L. F., & Dullaghan, T. R. (2016). Development of a new scale to measure subjective career success: A mixed-methods study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(1), 128–153. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2046

Simmering, M. J., Fuller, C. M., Richardson, H. A., Ocal, Y., & Atinc, G. M. (2015). Marker variable choice, reporting, and interpretation in the detection of common method variance: A review and demonstration. Organizational Research Methods, 18, 473–511. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428114560023.

Sonnentag, S., & Bayer, U.-V. (2005). Switching off mentally: Predictors and consequences of psychological detachment from work during off-job time. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10, 393–414. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.10.4.393

Sonnentag, S., & Fritz, C. (2007). The recovery experience questionnaire: Development and validation of a measure for assessing recuperation and unwinding from work. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12, 204–221. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1924

Sonnentag, S., & Fritz, C. (2015). Recovery from job stress: The stressor-detachment model as an integrative framework. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36, S72–S103. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1924

Sonnentag, S., Kuttler, I., & Fritz, C. (2010). Job stressors, emotional exhaustion, and need for recovery: A multi-source study on the benefits of psychological detachment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 76, 355–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.06.005

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2001). Using multivariate statistics (4th ed.). Harper & Row.

Thanacoody, P. R., Newman, A., & Fuchs, S. (2014). Affective commitment and turnover intentions among healthcare professionals: The role of emotional exhaustion and disengagement. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(13), 1841–1857. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.860389

Thompson, E. R. (2007). Development and validation of an internationally reliable short-form of the positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS). Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 38(2), 227–242.

Toth, J. F., Jr., Brown, R. B., & Xu, X. (2002). Separate family and community realities? An urban-rural comparison of the association between family life satisfaction and community satisfaction. Community, Work & Family, 5(2), 181–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668800220146364