Abstract

We examine the change in the level and significance of accrual and real earnings management over the period 1996–2018. Our univariate results show that both accrual and real earnings management continue to persist, although they have significantly decreased over time. After controlling for significant factors that have been shown to affect earnings management, we find that both accrual and real-activities earnings management have significantly decreased in the short term after the regulations, but accrual earnings management reverted back to its pre-regulation levels in the long run. Further, contrary to the findings of prior research (e.g., Cohen et al. in Account Rev 83:757–787, 2008) that managers have shifted away from accruals to real earnings management in the short-term post-regulation period, we find evidence that firms actually reduced real earnings management both in the short- and long-term post-regulation periods. The results are robust to alternative sample designs and inclusion of additional control variables, and go against the widely held beliefs that accruals-based earnings management is significantly less prevalent now than it used to be.

Similar content being viewed by others

Availability of data and materials

All data are publicly available from identified sources.

Notes

We also examine two aggregate measures of earnings management. Please see footnote 14. We do not examine abnormal cash flows from operations (ACFO) because it is difficult to interpret the coefficients of post-regulation variables in an ACFO regression. Specifically, in addition to price discounts and credit terms, ACFO is affected by abnormal production costs and abnormal selling and administrative expenses in different directions.

In a different context, examining the impact of CEO and CFO power on accruals and real earnings management, Baker, Lopez, Reitenga, Ruch (2019) find that in the post-SOX period the effect of relative CEO power on accrual earnings management subsides, whereas the effect of relative CFO power on real earnings management persists.

For an excellent summary of the effects of SOX, including a detailed discussion of a number of studies that document improvements in accounting quality following SOX, see Coates and Srinivasan (2014). Earnings management also has been studied around other regulations. For example, Liu (2020) examines the effect on real and accrual-based earnings management of requiring an engagement partner’s signature on the auditor report, and finds no significant change in the usage of accrual-based and/or real earnings management for firm-years suspected of beating/meeting the zero, last-year, or analyst forecast consensus earnings threshold from the pre- to post-signature period.

This conjecture is consistent with the findings of Espahbodi et al. (2015) that analyst forecast properties improved in the short run but deteriorated in the long run following the increase in regulations. They attribute the continued problem with the information environment to the quality of financial reports and relate their conclusion to the Hawthorne effect, and Tversky and Kahneman’s (1974) human decision-making biases. The conjecture is also consistent with Kedia et al. (2015) who find copying of poor accounting practices reappears from 2006 to 2008, possibly because the sting associated with SOX has worn off.

Courts also may judge, ex post, that the executive certification of financial statements was inadequate or inaccurate.

Although some of these requirements did not take effect until 2004, their inclusion in the Act likely affected earnings management practices upon the passage of SOX.

We end the short-term post-regulation period in 2006 because prior research showing improvement in earnings quality following SOX, as discussed in the Introduction section, ended their sample period on or before quarter 4 of that year. The exception is Kedia et al. (2015) who studies copying of poor accounting practices and find that such practices stopped during the years 2003–2005 (in the short run after SOX) but reappeared during 2006–2008 (in the longer term, consistent with our finding).

Including the scandal years in the study would only strengthen our results, as prior research (e.g., Cohen et al. 2008) indicates that the scandals and earnings management were at their peaks during 2000–2002, leading to the passage of SOX and other aforementioned regulations.

We repeat our analyses using the 593 firms to see if the results hold for a constant sample of firms. The results are discussed in the Sensitivity subsection.

Theoretically, earnings management may not always indicate managerial opportunism and rent-extraction type behavior. For example, Subramanyam (1996) shows that abnormal total accruals are priced by investors, although he states that the measurement error in the discretionary accruals proxy may explain his results. Similarly, Gunny (2010, 886) concludes that using real earnings management by firms just meeting earnings benchmarks (zero and last year’s earnings) “…is not opportunistic, but consistent with managers attaining benefits that allow better future performance or signaling.” However, consistent with the majority of prior published papers (e.g., Roychowdhury 2006; Graham et al. 2005; Cohen et al. 2008; Zang 2012), we assume that all types of earnings management are opportunistic and hence value-decreasing.

Srivastava (2019) shows that the inclusion of the last five variables (market capitalization, lagged ROA, market to book as a measure of growth, future sales, and the lagged dependent variable) significantly reduces the measurement errors in the usual proxies for real earnings management and improve the inferences of tests involving real earnings management (our Eqs. 2 through 4). We extend this logic to our accrual measure (Eq. 1) as he states that any model that estimates a firm’s abnormal or manipulative behavior by comparison to that of other industry peers should account for variations in strategy-driven characteristics across firms. As Srivastava acknowledges, however, these enhancements will overcorrect for misspecifications if earnings management varies with the firm’s opportunity set, if the firm always manages earnings, or if other firms in the industry equally manage earnings.

Srivastava (2019) also uses a cohort-adjusted measure, calculated by subtracting the abnormal earnings measure of a control firm from that of each sample firm. A control firm is the one that belongs to the same industry and has the same listing vintage (proxy for age) as a sample firm, and the closest size. We don’t adjust our abnormal earnings measures based on firm size or performance for the reasons explained in the rest of this paragraph, and because using cohort-adjusted measures actually decreased both the percentage improvement in true positives and the percentage reduction in false negatives for abnormal production cost and abnormal selling and administrative expense (Srivastava, 2019, Table 5, Panel D).

We also examine two aggregate measures of earnings management: abnormal real and abnormal total earnings management (AREM and ATEM). AREM is the absolute value of the sum of abnormal production cost and negative of abnormal selling and administrative expenses, the two dominant real earnings management measures; and ATEM is the absolute value of the sum of abnormal revenues, abnormal production costs, and negative of abnormal selling and administrative expenses, the three measures that significantly affect earnings. We use the negative of abnormal selling and administrative expenses because it affects earnings in the opposite direction of abnormal revenues and abnormal production costs. We discuss some of the results for these aggregate measures, but for brevity do not tabulate them.

We do not include all potentially significant variables to ensure a more parsimonious model and avoid severe multicollinearity issues. However, we add two additional corporate governance variables (executives’ options and shares incentive ratios) to our model in our sensitivity tests. Also, we do not examine the interaction between the incentives and the time intervals. This is in contrast with some prior research (e.g., Cohen et al. 2008) which includes some interaction effects. Including interaction effects in a model induces severe multicollinearity and if we were to add the interaction effects to our 17 variables plus the one-digit industry fixed effect and the firm fixed effect, the number of variables would increase substantially and although we will have a much better fit (higher R2), the results will be uninterpretable.

Similarly, to the extent that managerial compensation is based on reported earnings, managers have an incentive to increase (e.g., considering job security or bonus) or decrease the reported earnings (e.g., considering the upper limit in some bonus plans). We include executives’ options and shares incentive ratios in our sensitivity tests as additional variables in our model.

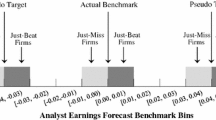

Rather than including additional control variables to capture the incentive to meet or beat earnings target, we rerun our regressions on the suspect firms only. Following prior research (e.g., Cheng et al. 2016; Roychowdhury 2006), we define suspect firms as those with actual EPS less the most recent consensus analyst forecast before earnings announcement between 0 and 1 percent of the closing stock price. The results are discussed in our sensitivity tests.

Many studies suggest that the composition of the board of directors determines its effectiveness. For example, Rosenstein and Wyatt (1990) and Klein (2002) argue that boards composed largely of outsiders are more effective than boards with few outsiders. Jensen (1994) argues that boards of directors are ineffectual monitors when the board’s equity ownership is small and when the CEO is also the Chairman of the Board. Prior research has also used numerous other measures of corporate governance. We use the percentage ownership by institutional investors as the only measure of corporate governance to avoid losing degrees of freedom due to missing data and to have a more parsimonious model (although in sensitivity tests we consider two additional corporate governance variables.

Results for our aggregate measures AREM, which is the sum of APROD, and negative ASGA and ATEM, which is the sum of AREV, APROD, and negative of ASGA, are consistent with those of their individual components.

Both our aggregate measures, AREM and ATEM, also decreased at the 1% levels in the short- and long-term post-regulation periods, respectively, suggesting that overall regulations may have been effective in reducing earnings management.

The results are somewhat different from the univariate results because of the presence of control variables. For example, while the Wilcoxon Z-Score and T-Statistic show that the median and mean ATACRU and APROD have decreased significantly in the long-term post-regulation period compared to the pre-regulation period, the regression results show that such decreases are not significant at the conventional levels.

The contradiction is potentially due to the addition of five variables, representing financial performance and strategy-driven firm characteristics, to our Eqs. 1 through 4 to reduce measurement errors in the usual proxies for earnings management, following Srivastava (2019). When we drop those five variables from our regressions 1 through 4, our results are consistent with prior research and show an increase in ASGA and our two aggregate measures both in the short- and long-term post-regulation periods. As Srivastava acknowledges, the addition of the five variables will overcorrect for misspecifications if earnings management varies with the firm’s opportunity set, if the firm always manages earnings, or if other firms in the industry equally manage earnings. Alternatively, prior studies may have simply arrived at the wrong conclusion due to the measurement errors in their earnings management proxies.

These variables are calculated following Bergstresser and Philippon (2006). Specifically, executives’ options incentive ratio = (0.01* stock price * number of options held by executives) divided by (SENSITIVE + total current compensation); executives’ shares incentive ratio = (0.01 * stock price * number of shares held by executives) divided by (SENSITIVE + total current compensation); and SENSITIVE = 0.01 * stock price * (number of shares held by executives + number of options held by executives).

Earlier studies (e.g., Cohen et al. 2008) do not scale the earnings surprise by price, and define suspect firms as those that meet or beat analyst forecasts by one cent per share or less.

Non-tabulated results show that both aggregate measures, AREM and ATEM decreased in the short term and the long term after the regulations. The coefficients of POSTREG_ST and POSTREG_LT in these two regressions were significant at the 1% level.

The differences in our findings could be due to the measurement errors in the usual proxies for earnings management used in previous studies. Alternatively, as Srivastava (2019) acknowledges, the earnings expectation models used in this study might have overcorrected for misspecifications, resulting in observance of lower earnings management levels.

References

Bartov E, Cohen D (2009) The ‘“numbers game”’ in the pre- and post-Sarbanes-Oxley eras. J Account Aud Financ 24:505–534

Baker TA, Lopez TJ, Reitenga AL, Ruch GW (2019) The influence of CEO and CFO power on accruals and real earnings management. Rev Quant Financ Account 52(1):325–345

Becker C, DeFond M, Jiambalvo J, Subramanyam K (1998) The effect of audit quality on earnings management. Contemp Account Res 15:1–24

Bergstresser D, Philippon T (2006) CEO incentives and earnings management. J Financ Econ 80:511–529

Bernard VL, Skinner DJ (1996) What motivates managers’ choice of discretionary accruals? J Account Econ 22:313–325

Burgstahler D, Dichev I (1997) Earnings management to avoid earnings decreases and losses. J Account Econ 24:99–126

Cheng Q, Lee J, Shevlin T (2016) Internal governance and real earnings management. Account Rev 91:1051–1085

Coates JC, Srinivasan S (2014) SOX after ten years: a multidisciplinary review. Account Horz 28:627–671

Cohen D, Dey A, Lys T (2008) Real and accrual based earnings management in the Pre and Post Sarbanes Oxley periods. Account Rev 83:757–787

Cohen D, Pandit S, Wasley CE, Zach T (2016) Measuring Real Activity Management. Available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=1792639 or http://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1792639.

Cohen D, Zarowin P (2010) Accrual-based and real earnings management activities around seasoned equity offerings. J Account Econ 50:2–19

Cooper LA, Downes JF, Rao R (2018) Short term real earnings management prior to stock repurchases. REV QUANT FINANC ACCOUNT 50(1):95–128

Dechow PM, Hutton AP, Kim JH, Sloan RG (2012) Detecting earnings management: a new approach. J Account Res 50(2):275–334

Dechow PM, Kothari SP, Watts RL (1998) The relation between earnings and cash flows. J Account Econ 25(2):133–168

Dechow PM, Richardson SA, Tuna I (2003) Why are earnings kinky? An examination of the earnings management explanation. Rev Acc Stud 8(2):355–384

Dechow PM, Sloan RG, Sweeney AP (1995) Detecting earnings management. Account Rev 70:193–225

Dechow PM, Sloan RG, Sweeney AP (1996) Causes and consequences of earnings manipulation: an analysis of firms subject to enforcement actions by the SEC. Contemp Account Res 13(1):1–36

DeFond ML, Jiambalvo J (1994) Debt covenant violation and manipulation of accruals. J Account Econ 17(1–2):145–176

Degeorge F, Patel J, Zeckhauser R (1999) Earnings management to exceed thresholds. J Bus 72(1):1–33

Duke JC, Hunt HG III (1990) An empirical examination of debt covenant restrictions and accounting-related debt proxies. J Account Econ 12(1–3):45–63

Dyck A, Morse A, Zingales L (2010) Who blows the whistle on corporate fraud? J Financ 65(6):2213–2253

Espahbodi H, Espahbodi P, Espahbodi R (2015) Did analyst forecast accuracy and dispersion improve after 2002 following the increase in regulation? Financ Anal J 71(5):20–37

Francis B, Hasan I, Li L (2016) Abnormal real operations, real earnings management, and subsequent crashes in stock prices. Rev Quant Financ Account 46(2):217–260

Gillespie G (1991) Manufacturing knowledge: A history of the Hawthorne experiments. Cambridge University Press.

Graham J, Harvey C, Rajgopal S (2005) The economic implications of corporate financial reporting. J Account Econ 40(1–3):3–73

Guay WR, Kothari SP, Watts RL (1996) Market-based evaluation of discretionary-accruals models. J Account Res 34:83–105

Gunny KA (2010) The relation between earnings management using real activities manipulation and future performance: Evidence from meeting earnings benchmarks. Contemp Account Res 27(3):855–888

Hamza SE, Kortas N (2019) The interaction between accounting and real earnings management using simultaneous equation model with panel data. Rev Quant Financ Account 53(4):1195–1227

Hribar P, Nichols DC (2007) The use of unsigned earnings quality measures in tests of earnings management. J Account Res 45(5):1017–1053

Jackson AB (2018) Discretionary accruals: Earnings management … or not? Abacus 54(2):136–153

Jensen MC (1994) The modern industrial revolution, exit, and the failure of internal controls systems. J App Corp Financ 6(4):4–23

Jones JJ (1991) Earnings management during import relief investigations. J Account Res 29(2):193–228

Kang S-H, Sivaramakrishnan K (1995) Issues in testing earnings management and an instrumental variable approach. J Account Res 33(2):353–367

Kedia S, Koh K, Rajgopal S (2015) Evidence on contagion in earnings management. Account Rev 90(6):2337–2373

Klein A (2002) Audit committee, board of director characteristics, and earnings management. J Account Econ 33(3):375–400

Koh K, Matsumoto D, Rajgopal S (2008) Meeting or beating analyst expectations in the postscandals world: changes in stock market rewards and managerial actions. Contemp Account Res 25(4):1067–1098

Kothari SP, Leone AJ, Wasley CE (2005) Performance matched discretionary accrual measures. J Account Econ 39(1):163–197

Kothari SP, Mizik N, Roychowdhury S (2016) Managing for the moment: The role of earnings management via real activities versus accruals in SEO valuations. Account Rev 91(2):559–586

Levitt A (1998) The numbers game. Speech delivered at the NYU Center for Law and Business New York, NY.

Liu M (2020) Real and accrual-based earnings management in the pre- and post- engagement partner signature requirement periods in the United Kingdom. Rev Quant Financ Account 54(3):1133–1161

Liu N, Espahbodi R (2014) Does dividend policy drive earnings smoothing? Account Horz 28(3):501–528

Lobo G, Zhou J (2006) Did conservatism in financial reporting increase after the Sarbanes-Oxley Act? Initial evidence. Account Horz 20(1):57–73

Matsumoto D (2002) Management’s incentives to avoid negative earnings surprises. Account Rev 77(3):483–514

McNichols M, Stubben S (2018) Research design issues in studies using discretionary accruals. Abacus 54(2):227–246

Miller M (1986) Financial innovation: The last twenty years and the next. J Financ Quant Anal 21:459–471

Rosenstein S, Wyatt J (1990) Outside directors, board independence, and shareholder wealth. J Financ Econ 26(2):175–191

Roychowdhury S (2006) Earnings management through real activities manipulation. J Account Econ 42(3):335–370

Sarra EH, Kortas N (2019) The interaction between accounting and real earnings management using simultaneous equation model with panel data. Rev Quant Financ Account 53(4):1195–1227

Srivastava A (2019) Improving the measures of real earnings management. Rev Acc Stud 24(4):1277–1316

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) (1999) Revenue recognition. Staff Accounting Bulletin No. 101 Washington, D.C., Government Printing Office.

Skinner D, Soltes E (2011) What do dividends tell us about earnings quality? Rev Acc Stud 16(1):1–28

Stubben S (2010) Discretionary revenues as a measure of earnings management. Account Rev 85(2):695–717

Subramanyam K (1996) The pricing of discretionary accruals. J Account Econ 22(1–3):249–281

Thomas J, Zhang H (2002) Inventory changes and future returns. Rev Acc Stud 7(2):163–187

Watts R, Zimmerman J (1990) Positive accounting theory: a ten year perspective. Account Rev 65:131–156

Tversky A, Kahneman D (1974) Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases. Science 185(4157):1124–1131

Zang AY (2012) Evidence on the trade-off between real activities manipulation and accrual-based earnings management. Account Rev 87(2):675–703

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the suggestions and guidance from Bharat Sarat and Rob Weigand. Also appreciated are the helpful comments from the participants at the 2019 Journal of Contemporary Accounting and Economics Annual Symposium and the 2020 Hawaii Accounting Research Conference. We are grateful for the suggestions and guidance from C.F. Lee (editor) and two anonymous reviewers. The remaining errors are ours.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1: Variable definitions

Appendix 1: Variable definitions

AGE is the number of years a firm has been listed on Compustat database as of the end of prior fiscal year.

APROD is abnormal production costs. It is the absolute value of the residual from regressing production costs (PROD) on an intercept, sales, change in sales in the current and preceding years, natural log of market capitalization, lagged return on assets, market to book ratio, next year’s sales, and lagged PROD. A separate regression is estimated for each two-digit SIC industry for each year. PROD, intercept, sales, change in sales in the current and preceding years, and next year’s sales are scaled by total assets at the beginning of the year. A constant is added to each regression to reduce misspecification.

AREV is abnormal revenue. It is the absolute value of the residual from regressing the change in accounts receivable (ΔAR) on an intercept, change in net sales of the first three quarters, change in net sales of the fourth quarter, natural log of market capitalization, lagged return on assets, market to book ratio, next year’s sales, and lagged ΔAR. ΔAR, intercept, change in net sales of the first three quarters, change in net sales of the fourth quarter, and next year’s sales are scaled by total assets at the beginning of the year. A separate regression is estimated for each two-digit SIC industry for each year. A constant is added to each regression to reduce misspecification.

ASGA is abnormal selling and administrative expenses. It is the absolute value of the residual from regressing selling and administrative expenses (SGA) on an intercept, lagged sales, natural log of market capitalization, lagged return on assets, market to book ratio, next year’s sales, and lagged SGA. A separate regression is estimated for each two-digit SIC industry for each year. SGA, intercept, lagged sales, and next year’s sales are scaled by total assets at the beginning of the year. A constant is added to each regression to reduce misspecification.

ATACRU is the absolute value of abnormal total accruals (TACRU) estimated using the Jones (1991) model adjusted for financial performance and strategy-driven firm characteristics. Specifically, ATACRU is the absolute value of the residual from the regression of total accruals on an intercept, change in sales, gross property plant and equipment (PPE), natural log of market capitalization, lagged return on assets, market to book ratio, next year’s sales, and lagged TACRU. TACRU, intercept, change in sales, PPE, and next year’s sales are scaled by total assets at the beginning of the year. A constant is added to each regression to reduce misspecification.

AREM is abnormal real earnings management. It is the absolute value of the sum of abnormal production cost and negative of abnormal selling and administrative expense.

ATEM is abnormal total earnings management. It is the absolute value of the sum of abnormal revenue, abnormal production cost, and negative of abnormal selling and administrative expense.

AUDITOR refers to the audit firm; it is set to one if the audit firm is a Big-Four, and to zero otherwise.

DEBISSUE is one if the firm issued debt during the current or following year, and zero otherwise.

EQISSUE is one if the firm issued or repurchased shares amounting to three percent or more of total outstanding shares during the current or following year, and zero otherwise.

FOLLOW is the number of analysts following a firm.

INSTOWNPCT is the fraction of voting shares held by institutional investors.

LEVERAGE is debt as a percentage of total assets.

LITIGATION is one if the firm is in an industry with a high litigation risk, and zero otherwise. High litigation industries are defined as SIC codes 2833-2836, 3570-3577, 3600-3674, 7371-7379, and 8731-8734 (Matsumoto 2002).

LMKVAL is the natural log of market capitalization, a measure of size.

LTA is the natural log of total assets (TA), another measure of size.

MKBK is market value divided by book value of equity.

POSTREG_LT is equal to one in the long-term post-regulation period (firm-year observations corresponding to fiscal years 2007–2018), and zero otherwise.

POSTREG_ST is equal to one in the short-term post-regulation period (firm-year observations corresponding to fiscal years 2003–2006), and zero otherwise.

PPE is gross property, plant, and equipment.

ROA is income before extraordinary items as a percentage of beginning assets.

SPCHG is the percentage change in S&P index from the previous fiscal year.

SALES1_3 is net sales (SALES) of the first three quarters.

SALES4 is net sales of fourth quarter.

σCFO and σREV are the standard deviations of cash flow from operations and revenues over the last five years, respectively, deflated by total assets at the beginning of the year.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Espahbodi, H., Espahbodi, R., John, K. et al. Earnings management in the short- and long-term post-regulation periods. Rev Quant Finan Acc 58, 217–244 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-021-00993-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-021-00993-2