Abstract

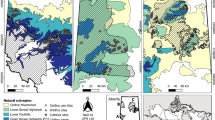

Protecting wildlife corridors is a common management problem in regions of industrial forestry. In boreal Canada, human disturbances have negatively affected woodland caribou populations (Rangifer tarandus caribou), which prefer to function in large undisturbed areas. We present a linear programming model that allocates a fixed-width corridor between isolated caribou ranges and estimates its impact on harvest activities. Our corridor placement problem minimizes total resistance for caribou passing through the corridor, which is protected by a prohibition on all economic activities. We link this corridor placement problem with a harvest planning problem that maximizes the net revenues from harvest minus the cost of building and maintaining forest access roads. We depict gradual expansion of the forest road network over time as a multi-temporal network flow problem. We applied our approach to explore corridor options for connecting caribou populations in the Lake Superior Coast Range, with the Nipigon and Pagwachuan Ranges in the Kenogami-Pic Forest, in northern Ontario, Canada. Our results revealed two locations where corridor placement is cost-effective. Optimal corridor placement depends on the perception of the severity of the impact of roads on caribou populations and decision-making objectives. When the negative impact of roads is perceived to be high and/or maximizing harvest revenues is important, the optimal corridor location is in the eastern part of the study area. However, it is optimal to place the corridor in the western part of the area when the negative impact of roads is perceived to be small or the shortest corridor is desired.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Le Bras, R., Dilkina, B., Xue, Y., Gomes, C.P., McKelvey, K.S., Schwartz, M.K., Montgomery, C.A.: Robust network design for multispecies conservation. In: AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. http://www.aaai.org/ocs/index.php/AAAI/AAAI13/paper/view/6497 (2013). Accessed 01.05.18

Williams, J.C., Snyder, S.A.: Restoring habitat corridors in fragmented landscapes using optimization and percolation models. Environ. Model. Assess. 10, 239–250 (2005)

Conrad, J., Gomes, C.P., van Hoeve, W.-J., Sabharwal, A., Suter, J.: Wildlife corridors as a connected subgraph problem. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 63, 1–18 (2012)

Dilkina, B., Gomes, C.: Solving connected subgraph problems in wildlife conservation. In: Lodi, A., Milano, M., Toth, P. (eds.) Integration of AI and OR techniques in constraint programming for combinatorial optimization problems. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 6140, pp. 102–116. Springer, Berlin /Heidelberg (2010)

Dilkina, B., Houtman, R., Gomes, C., Montgomery, C., McKelvey, K., Kendall, K., Graves, T., Bernstein, R., Schwartz, M.: Trade-offs and efficiencies in optimal budget-constrained multispecies corridor networks. Conserv. Biol. (2016). https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12814

Beier, P., Majka, D.R., Spencer, W.D.: Forks in the road: choices in procedures for designing wildland linkages. Conserv. Biol. 22, 836–851 (2008)

Lentini, P.E., Gibbons, P., Carwardine, J., Fischer, J., Drielsma, M., Martin, T.G.: Effect of planning for connectivity on linear reserve networks. Conserv. Biol. 27, 796–807 (2013)

Crooks, K.R., Sanjayan, M. (eds.): Connectivity Conservation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2006)

Beier, P., Spencer, W., Baldwin, R.F., McRae, B.H.: Toward best practices for developing regional connectivity maps. Conserv. Biol. 25, 879–892 (2011)

Haddad, N.M., Bowne, D.R., Cunningham, A., Danielson, B.J., Levey, D.J., Sargent, S., Spira, T.: Corridor use by diverse taxa. Ecology 84, 609–615 (2003)

Brandt, J.P., Flannigan, M.D., Maynard, D.G., Thompson, I.D., Volney, W.J.A.: An introduction to Canada’s boreal zone: ecosystem processes, health, sustainability, and environmental issues. Environ. Rev. 21, 207–226 (2013)

James, A.R.C., Stuart-Smith, A.K.: Distribution of caribou and wolves in relation to linear corridors. J. Wildl. Manag. 64, 154–159 (2000)

Latham, A.D.M., Latham, C., McCutchen, N.A., Boutin, S.: Invading white-tailed deer change wolf-caribou dynamics in northeastern Alberta. J. Wildl. Manag. 75, 204–212 (2011)

Wittmer, H.U., Sinclair, A.R.E., McLellan, B.N.: The role of predation in the decline and extirpation of woodland caribou. Oecologia 144, 257–267 (2005)

Festa-Bianchet, M., Ray, J.C., Boutin, S., Cote, S.D., Gunn, A.: Conservation of caribou (Rangifer tarandus) in Canada: an uncertain future. Can. J. Zool. 89, 419–434 (2011)

Hebblewhite, M.: Billion dollar boreal woodland caribou and the biodiversity impacts of the global oil and gas industry. Biol. Cons. 206, 102–111 (2017)

Hebblewhite, M., Fortin, D.: Canada fails to protect its caribou. Science 358(6364), 730–731 (2017)

Species at Risk Act (SARA): Bill C-5, An act respecting the protection of wildlife species at risk in Canada. http://laws.justice.gc.ca/PDF/Statute/S/S-15.3.pdf (2010). Accessed 06.05.19

Environment Canada (EC): Scientific Assessment to Support the Identification of Critical Habitat for Woodland Caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou), Boreal Population, in Canada. Ottawa, ON (2011)

Environment Canada (EC): Recovery Strategy for the Woodland Caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou), Boreal population, in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment Canada, Ottawa, ON. http://www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/virtual_sara/files/plans/rs%5Fcaribou%5Fboreal%5Fcaribou%5F0912%5Fe1%2Epdf (2012). Accessed 08.09.19

Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC): Report on the Progress of Recovery Strategy Implementation for the Woodland Caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou), Boreal population in Canada for the Period 2012–2017, Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series, Environment and Climate Change Canada, Ottawa, ON. http://registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/virtual_sara/files/Rs%2DReportOnImplementationBorealCaribou%2Dv00%2D2017Oct31%2DEng%2Epdf (2017). Accessed 01.02.20

Ruppert, J.L.W., Fortin, M.-J., Gunn, E.A., Martell, D.L.: Conserving woodland caribou habitat while maintaining timber yield: a graph theory approach. Can. J. For. Res. 46, 914–923 (2016)

McKenney, D.W., Nippers, B., Racey, G., Davis, R.: Trade-offs between wood supply and caribou habitat in northwestern Ontario. Rangifer 10, 149–156 (1997)

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (OMNRF): Woodland Caribou Conservation Plan. https://www.ontario.ca/page/woodland-caribou-conservation-plan (2020). Accessed 03.04.20

Zeller, K.A., McGarigal, K., Whiteley, A.R.: Estimating landscape resistance to movement: a review. Landscape Ecol. 27, 777–797 (2012)

Graves, T.A., Chandler, R.B., Royle, J.A.: Estimating landscape resistance to dispersal. Landscape Ecol. 29, 1201–1211 (2014)

Koen, E.L., Bowman, J., Sadowski, C., Walpole, A.A.: Landscape connectivity for wildlife: development and validation of multispecies linkage maps. Methods Ecol. Evol. 5, 626–633 (2014)

Wade, A.A., McKelvey, K.S., Schwartz, M.K.: Resistance-surface-based Wildlife Conservation Connectivity Modeling: Summary of Efforts in the United States and Guide for Practitioners. General technical report RMRS-GTR-333, U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fort Collins, CO (2015)

Cushman, S.A., McKelvey, K.S., Schwartz, M.K.: evaluating habitat connectivity and mapping of corridors between Yellowstone National Park and the Canadian border with landscape genetics and least cost path analysis. Conserv. Biol. 23, 368–376 (2009)

Rayfield, B., Fortin, M.-J., Fall, A.: The sensitivity of least-cost habitat graphs to relative cost surface values. Landscape Ecol. 25, 519–532 (2010)

Parks, S.A., McKelvey, K.S., Schwartz, M.K.: Effects of weighting schemes on the identification of wildlife corridors generated with least-cost methods. Conserv. Biol. 27, 145–154 (2013)

Pullinger, M.G., Johnson, C.J.: Maintaining or restoring connectivity of modified landscapes: evaluating the least-cost path model with multiple sources of ecological information. J. Ecol. 25, 1547–1560 (2010)

Royle, J.A., Chandler, K., Gazenski, K.D., Graves, T.A.: Spatial capture-recapture models for jointly estimating population density and landscape connectivity. Ecology 94, 287–294 (2013)

Singleton, P.H., Gaines, W.L., Lehmkuhl, J.F.: Landscape Permeability for Large Carnivores in Washington: A Geographic Information System Weighted-Distance and Least-Cost Corridor Assessment. Forestry Sciences Res. Pap. PNW-RP-549 USDA Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. http://www.arlis.org/docs/vol1/51864782.pdf (2002). Accessed 11.04.18

Adriaensen, F., Chardon, J.P., De Blust, G., Swinne, E., Villalba, S., Gulinck, H., Matthysen, E.: The application of ‘least-cost’ modelling as a functional landscape model. Landsc. Urban Plan. 64, 233–247 (2003)

Spear, S.F., Balkenhol, N., Fortin, M., McRae, B.H., Scribner, K.: Use of resistance surfaces for landscape genetic studies: considerations for parameterization and analysis. Mol. Ecol. 19, 3576–3591 (2010)

Torrubia, S., McRae, B.H., Lawler, J.J., Hall, S.A., Halabisky, M., Langdon, J., Case, M.: Getting the most connectivity per conservation dollar. Front. Ecol. Environ. 12, 491–497 (2014)

Cushman, S.A., Landguth, E.L., Flather, C.H.: Evaluating population connectivity for species of conservation concern in the American Great Plains. Biodivers. Conserv. 22, 2583–2605 (2013)

Dilkina, B., Lai, K.J., Gomes, C.P.: Upgrading shortest paths in networks. In: International Conference on Integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Operations Research (OR) Techniques in Constraint Programming, pp. 76–91. Springer, Berlin (2011)

Stjohn, R., Öhman, K., Tóth, S.F., Sandström, P., Korosuo, A., Eriksson, L.O.: Combining spatiotemporal corridor design for reindeer migration with harvest scheduling in northern Sweden. Scand. J. For. Res. 37, 655–663 (2016)

Sarkar, S., Pressey, R., Daniel, F., Margules, C., Fuller, T., Moffett, S.D.A., Wilson, K., Williams, K., Williams, P., Andelman, S.: Biodiversity conservation planning tools: present status and challenges for the future. Annual Rev Environ Resour 31, 123–159 (2006)

Moilanen, A., Wilson, K.A., Possingham, H.P. (eds.): Spatial Conservation Prioritization: Quantitative Methods and Computational Tools. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2009)

Stewart, R.R., Possingham, H.P.: Efficiency, costs and trade-offs in marine reserve system design. Environ. Model. Assess. 10, 203–213 (2005)

Cerdeira, J., Gaston, K., Pinto, L.: Connectivity in priority area selection for conservation. Environ. Model. Assess. 10, 183–192 (2005)

Önal, H., Briers, R.A.: Optimal selection of a connected reserve network. Oper. Res. 54, 379–388 (2006)

Shirabe, T.: A model of contiguity for spatial unit allocation. Geogr. Anal. 37, 2–16 (2005)

Williams, J.: Delineating protected wildlife corridors with multi-objective programming. Environ. Model. Assess. 3, 77–86 (1998)

Lai, K.J.; Gomes, C.P.; Schwartz, M.K.; McKelvey, K.S.; Calkin, D.E.; Montgomery, C.A.: The Steiner Multigraph Problem: Wildlife Corridor Design for Multiple Species, Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI-11), August 7–11, 2011. San Francisco, CA, USA (2011)

Sessions, J.: Solving for habitat connections as a Steiner network problem. Forest Science 38, 203–207 (1992)

Cerdeira, J., Pinto, L.S., Cabeza, M., Gaston, K.J.: Species specific connectivity in reserve-network design using graphs. Biol. Cons. 143, 408–415 (2010)

Önal, H., Wang, Y.: A graph theory approach for designing conservation reserve networks with minimal fragmentation. Networks 52, 142–152 (2008)

Önal, H., Briers, R.: Incorporating spatial criteria in optimum reserve network selection. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 269(1508), 2437–2441 (2002)

Önal, H., Briers, R.: Selection of a minimum-boundary reserve network using integer programming. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 270(1523), 1487–1491 (2003)

Jafari, N., Hearne, J.: A new method to solve the fully connected reserve network design problem. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 231, 202–209 (2013)

Jafari, N., Nuse, B.L., Moore, C.T., Dilkina, B., Hepinstall-Cymerman, J.: Achieving full connectivity of sites in the multiperiod reserve network design problem. Comput. Oper. Res. 81, 119–127 (2017)

Carvajal, R., Constantino, M., Goycoolea, M., Vielma, J.P.: Imposing connectivity constraints in forest planning models. Oper. Res. 61, 824–836 (2013)

Yemshanov, D., Haight, R.G., Liu, N., Parisien, M.-A., Barber, Q., Koch, F.H., Burton, C., Mansuy, N., Campioni, F., Choudhury, S.: Assessing the trade-offs between timber supply and wildlife protection goals in boreal landscapes. Can. J. For. Res. 50, 243–258 (2020)

Ohman, K., Lamas, T.: Reducing forest fragmentation in long-term forest planning by using the shape index. For. Ecol. Manage. 212, 346–357 (2005)

Öhman, K., Wikström, P.: Incorporating aspects of habitat fragmentation into long-term forest planning using mixed integer programming. For. Ecol. Manage. 255, 440–446 (2008)

Yoshimoto, A., Asante, P.: A new optimization model for spatially constrained harvest scheduling under area restrictions through maximum flow problem. For. Sci. 64, 392–406 (2018)

Yoshimoto, A.: Optimal Aggregation of Forest Units to Clusters as “Danchi” under Lower and Upper Size Bounds for Forest Management in Japan, FORMATH 19 (2020). https://doi.org/10.15684/formath.19.005https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/formath/19/0/19_19.005/_article/-char/en . Accessed 04.05.20

Martin, R.: Kipp: Using separation algorithms to generate mixed integer model reformulations. Oper. Res. Lett. 10(3), 119–128 (1991)

StJohn, R., Tóth, S.F., Zabinsky, Z.: Optimizing the geometry of wildlife corridors in conservation reserve design. Op. Res. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1287/opre.2018.1758

Hornseth, M.L., Rempel, R.S.: Seasonal resource selection of woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou) across a gradient of anthropogenic disturbance. Can. J. Zool. 94, 79–93 (2015)

Rempel, R.S.; Hornseth, M.L.: Range-specific seasonal resource selection probability functions for 13 caribou ranges in Northern Ontario, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Science and Research Branch, Science and Research Internal File Report IFR-01, Peterborough, ON (2018)

Naderializadeh, N., Crowe, K.A.: Formulating the integrated forest harvest scheduling model to reduce the cost of the road networks. Oper. Res. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12351-018-0410-5

Johnson, K.N., Scheurman, H.L.: Techniques for prescribing optimal timber harvest and investment under different objectives - discussion and synthesis. For. Sci. Monogr. 18(1), 1–31 (1977)

McDill, M., Rebain, S., Braze, J.: Harvest scheduling with area-based adjacency constraints. For. Sci. 48, 631–642 (2002)

McDill, M.E., Tóth, S.F., John, R.T., Braze, J., Rebain, S.A.: Comparing model I and model II formulations of spatially explicit harvest scheduling models with maximum area restrictions. For. Sci. 62, 28–37 (2016)

National Forestry Database (NFD): Harvest. 5.2 Area harvested by jurisdiction, tenure, management and harvesting method. http://nfdp.ccfm.org/en/data/harvest.php (2019). Accessed 02.01.20

James, A.R.C., Boutin, S., Hebert, D.M., Rippin, A.B.: Spatial separation of caribou from moose and its relation to predation by wolves. J. Wildl. Manag. 68, 799–809 (2004)

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR): Forest Management Guide for Boreal Landscapes. Toronto: Queen’s Printer for Ontario (2014)

Johnson, C.J., Parker, K.L., Heard, D.C., Gillingham, M.P.: A multiscale behavioural approach to understanding the movements of woodland caribou. Ecol. Appl. 12, 1840–1860 (2002)

Ferguson, S.H., Elkie, P.C.: Habitat requirements of boreal forest caribou during the travel seasons. Basic Appl. Ecol. 5, 465–474 (2004)

Ferguson, S.H., Elkie, P.C.: Seasonal movement patterns of woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou). J. Zool. 262, 125–134 (2004)

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (OMNRF): General habitat description for the forest-dwelling woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou). http://govdocs.ourontario.ca/node/29324 (2015). Accessed 11.09.19

Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, Wildland League (CPAWS): A Snapshot of Caribou Range Condition in Ontario, Special Report. https://wildlandsleague.org/media/Caribou-Range-Condition-in-Ontario-WL2009-HIGH-RES.pdf (2009). Accessed 12.11.19

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR): Ontario's Woodland Caribou Conservation Plan progress report winter 2012. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Toronto, ON. https://www.porcupineprospectors.com/wp-content/uploads/Woodland-Caribou.pdf (2012). Accessed 12.11.19

Elkie, P., Green, K., Racey, G., Gluck, M., Elliott, J., Hooper, G., Kushneriukand, R., Rempel, R.: Science and Information in Support of Policies that Address the Conservation of Woodland Caribou in Ontario: Occupancy, Habitat and Disturbance Models, Estimates of Natural Variation and Range Level Summaries, Electronic Document. Version 2018. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Forests Branch (2018)

Natural Resources Canada (NRCan): Topographic Data of Canada - CanVec Series.https://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/8ba2aa2a-7bb9-4448-b4d7-f164409fe056 (2019). Accessed 06.03.20

Maure, J.: Ontario forest biofibre, Presentation made at Cleantech Biofuels Workshop, February 13, 2013. https://www.sault-canada.com/en/aboutus/resources/Supporting_Doc_2_-_Available_biomass.pdf (2013). Accessed 02.03.19.

Green Forest Management Inc. (GMFI): Ring of Fire & Northern Ontario Community All-Weather Road Access. Preliminary Location & Cost Projection, Prepared for: KWG Resources Inc. by Green Forest Management Inc, December 2013. http://kwgresources.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/GFMI_KWG-Road-Location-Cost-Projection-Dec-2013.pdf (2013). Accessed 02.03.20

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (OMNRF): Forest Resources Inventory (FIM v 2.2D) Packaged Product. https://geohub.lio.gov.on.ca/datasets/forest-resources-inventory-fim-v2-2d-packaged-product (2019). Accessed 01.12.19

McKenney, D.W., Yemshanov, D., Pedlar, J., Allen, D., Lawrence, K., Hope, E., Lu, B., Eddy, B.: Canada’s Timber Supply: Current Status and Future Prospects under a Changing Climate, Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service. Great Lakes Forestry Centre, Information Report GLC-X-15, Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario (2016)

Boulanger, Y., Gauthier, S., Burton, P.J.: A refinement of models projecting future Canadian fire regimes using homogeneous fire regime zones. Can. J. For. Res. 44, 365–376 (2014)

Magnanti, T.L., Wong, R.T.: Network design and transportation planning: models and algorithms. Transp. Sci. 18, 1–55 (1984)

Murray, A.T.: Spatial restrictions in harvest scheduling. For. Sci. 45(1), 45–52 (1999)

Guignard, M., Ryu, C., Spielberg, K.: Model tightening for integrated timber harvest and transportation planning. Eur J Op Res 111, 448–460 (1998)

Andalaft, N., Andalaft, P., Guignard, M., Magendzo, A., Wainer, A., Weintraub, A.: A problem of forest harvesting and road building solved through model strengthening and Lagrangean relaxation. Oper. Res. 51, 613–628 (2003)

Najafi, A., Richards, E.W.: Designing a forest road network using mixed integer programming. Croat. J. For. Eng. 34, 17–30 (2013)

Ontario Ministry of Energy, Northern Development and Mines (OMENDM): Ring of Fire. https://www.mndm.gov.on.ca/en/ring-fire (2019). Accessed 01.05.20

Foster, R.F., Harris, A.G.: Marathon Platinum Group Metals and Copper Mine Project. Marathon PGM-Cu project supporting information document No. 26 - Marathon PGM-Cu project - assessment of impacts on woodland caribou. Prepared for: Stillwater Canada Inc. https://iaac-aeic.gc.ca/050/documents_staticpost/54755/80504/Supporting_Document_26_-_Woodland_Caribou_Report.pdf (2012). Accessed 01.02.21

GAMS (GAMS Development Corporation): General Algebraic Modeling System (GAMS) Washington, DC, USA, 2020. General information is available at http://www.gams.com

GUROBI (Gurobi Optimization Inc.): GUROBI Optimizer Reference Manual. Version 9.1 (2020) General information is available at http://www.gurobi.com

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service Cumulative Effects Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Model initialization

Hard combinatorial complexity makes it difficult to find feasible solutions for the full problem with large datasets. We used the following initialization procedure to warm start the full problem in Eq. (30) in the main text. First, we solved the corridor placement problem without harvest planning, i.e.:

subject to constraints (2–7) in the main text (see symbol definitions in Table 1 in the main text).

We then used the wn values (which define optimal corridor placement in problem (34)) as a fixed parameter, w’n, to solve the harvest planning problem with a fixed corridor.

To initialize the road construction model, we modified the problem formulation by introducing separate time sets for the harvest planning problem and the road construction sub-problem, t ∈ T and t’ ∈ T’, respectively. Harvest is always allocated over the full planning horizon T, but road construction may be planned over a shorter time span T’, T’ ≤ T. All equations in the road construction sub-problem use the time set T’ (a subset of the time set T), i.e.:

s.t.: harvest planning constraints (11–13),(19) in the main text and:

where w’n is a binary parameter equal to the optimal wn values from the corridor placement solution of the problem (34). The formulation in equations (34–53) above is similar to the harvest planning with road construction formulation in Eqs. (10–28) in the main text, except that a separate time domain T’ is used in equations defining the road construction sub-problem. Using a shorter time domain for the road construction sub-problem, while solving the harvest allocation for the full planning horizon T with an account for road building cost over a time span T’), reduces the numeric complexity of the problem and makes it possible to find feasible solutions via a set of T consecutive optimizations with a stepwise increase of the time horizon T’ from 1 to T, as described below.

The initialization was started by setting the road construction horizon T’ to one period (i.e., the first period, T’ = 1), but solved the harvest allocation problem for the full horizon T. After finding the harvest solution for T periods and optimal road construction pattern for period 1, we set the time domain T’ to two periods and solved the problem again using the decision variables xni, vnmt’ and ynmt’ from the solution with T’ = 1 as a warm start. After saving the optimal solution with T’ = 2, we increased the T’ value to three periods and solved the model again using xni, vnmt’ and ynmt’ from the solution with T’ = 2 as a warm start, and so on until we solved the model for T’ = T periods. To speed up the solution we included, at each solution step starting from T’ = 2, two more constraints which fixed the road construction decision variables vnmt’ and ynmt’ to their initialized values for the planning periods 1,..,T’-1 so that at each initialization step the model only needed to find the optimal road construction network for one period t’ = T’, i.e.:

where y’nmt’ and v’nmt’ are fixed parameters equal to the optimal values of decision variables ynmt’ and vnmt’ in the solution in the previous step.

After solving the problem repeatedly for a sequence of 1 to T’ horizons, the optimal solution depicted a short-sighted road planning policy where harvesting was optimized over the entire horizon T but the road construction network was optimized only within a single planning period t. We then used the set of decision variables from the last solution for T’ = T to warm start the full problem (30) in the main text. A similar procedure but without the corridor placement sub-problem (34) was used to solve the harvest-only problem with optimal road construction, In the harvest-only problem, the w’n values were fixed to zeroes. We composed the model in the General Algebraic Modeling System (GAMS) [93] and solved it with the GUROBI linear programming solver [94].

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yemshanov, D., Haight, R.G., Liu, N. et al. Exploring the tradeoffs among forest planning, roads and wildlife corridors: a new approach. Optim Lett 16, 747–788 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11590-021-01745-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11590-021-01745-w