Abstract

Small businesses face major challenges to becoming more innovative. These challenges are particularly prevalent in emerging economies where high uncertainties are a barrier to innovation. We know from previous studies that linkages to universities, on the one hand, and public procurement, on the other, support large and innovative firms in their efforts to become more innovative. However, we do not know whether these positive effects also hold true for small businesses. In this paper, we focus on how policy strategies reducing information, market and financial uncertainties shape small businesses’ innovation in China. Based on a sample of 926 small businesses derived from the World Bank Enterprises Survey in China (2012), we find that university-industry linkages enhance innovation, though only when it comes to minor forms of innovation. In line with the resource-based view of the firm, this effect is stronger for small businesses with higher capabilities. Moreover, we show that bidding for or delivering contracts to public sector clients has a positive effect on innovation, and in particular of major forms of innovation. In the bidding selection process, private firms and firms with higher capabilities are selected. Our findings show that both policy strategies have enhanced innovation, though with different effects on the degree of novelty. We attribute this finding to the different degrees of uncertainties they address.

Similar content being viewed by others

Small businesses face major challenges becoming more innovative (Terziovski, 2010). These challenges particularly affect small businesses in emerging economies where institutional voids (Khanna et al., 2005) and weak institutional enforcement (Armanios & Eesley, 2021; Pertuze et al., 2019) lead to high information, market and financial uncertainties. While large firms may be able to overcome these uncertainties by developing institutional substitutes, for example by establishing global research centers (Fu, 2015), this option is less available for small businesses as their resource scarcity does not allow them to create such substitutes (Deng & Zhang, 2018; Herrmann et al., 2020). As a result, an environment characterized by uncertainty creates significant barriers even to incremental forms of innovation (Allard et al., 2012; Ngyuyen & Jaramillo, 2014).

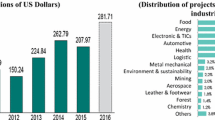

Against this background, innovation policies aim at reducing these uncertainties. Policies stimulating linkages to universities reduce information uncertainty as they provide additional sources of knowledge, ideas and technological opportunities (Ponomariov, 2014). Public procurement policies reduce uncertainties even more comprehensively as governments define promising technological paths, create demand, guarantee a certain amount of product sales, and hereby reduce information, market and financial uncertainties (Li et al., 2015). Both strategies are high on the political agenda (Eom & Lee, 2010; Monux & Ospina, 2016; Tang et al., 2019). In China, for example, three out of the nine major policy fields outlined in the present “National Medium- and Long-term Program for Science and Technology Development” are devoted to stimulating university-industry linkages. In turn, public spending on public procurement by far exceeds total government support to business R&D. With 3.1% of GDP, the spending on public procurement was 24 times larger than total government support to business R&D (data for 2015; Chinese Ministry of Finance, 2016; OECD, 2018). Important examples include the development of innovative products such as LEDs, monitoring devices for environmental pollution or portable test systems for food.

However, prior research on the effect of these strategies in the context of emerging economies has mainly focused on large and innovative firms (Fischer et al., 2019a, 2019b; Hong & Su, 2013; Kafouros et al., 2015; Liang & Liu, 2018; Motohashi & Yun, 2007; Tang et al., 2019). This is surprising given that small businesses constitute by far the largest share of businesses, and are an important potential source for building up innovative capabilities (Jones & Tilley, 2003). Further, previous research did not differentiate between degrees of innovative novelty, leading to an ambiguous expectation that innovation policies have uniform effects on a firm’s innovation outcome (Caloghirou et al., 2016; Fischer et al., 2019b). Consequently, we do not know whether or how small businesses in emerging economies benefit from these strategies, and we also do not know which firms benefit most. This paper seeks to address this gap.

To address this gap, we empirically analyze the effect of university-industry linkages and public procurement on small businesses’ innovation, and identify which firms benefit most. We use a nationwide sample of Chinese private manufacturing firms, developed based on the most recent World Bank Enterprise Survey in China (2012). This survey is similar to the Community Innovation Survey of the European Union which is one of the main sources of innovation research (Fitjar & Rodriguez-Pose, 2013; Love et al., 2014; Sadowski & Sadowski-Rasters, 2006). The data allow us to better understand whether and how these two policy strategies are associated with innovation, and who benefits most. Following previous research (see e.g. Klingebiel & Rammer, 2014; Sadowski & Sadowski-Rasters, 2006), we use the distinction between new-to-firm and new-to-market with respect to innovation novelty degree. As we are able to address endogeneity and selection biases, we interpret these associations, within the constraints of a statistical analysis, as causal effects. Experiences from one of the most innovative emerging economies may provide valuable lessons for other emerging economies with regard to innovation policy design.

Accordingly, our paper contributes to the literature on innovation in emerging economies, and in particular the literature on university-industry linkages and public procurement. Our first contribution is to the literature on university-industry linkages and innovation. We extend prior research which has focused on how large and innovative firms in emerging economies (Fischer et al., 2019a; Hong & Su, 2013; Kafouros et al., 2015; Liang & Liu, 2018; Motohashi & Yun, 2007; Tang et al., 2019) benefit from such linkages, often connected with the finding that these lead to large jumps in firms’ innovation (Caloghirou et al., 2016; Fischer et al., 2019b). We show that linkages to universities only stimulate small businesses’ new-to-firm innovation, thus minor innovations with a lower degree of novelty. Using university density as our instrument variable, we are able to show this to be a causal relationship, and that also small businesses which had not carried out innovations before benefit from these linkages. Hence, universities evidently play an important and previously overlooked role in upgrading small businesses: less by promoting large jumps of small businesses, but by supporting them in catching-up. We further identify important boundary conditions: Small businesses with higher capabilities are more likely to benefit from these linkages.

Our second contribution is to the literature on public procurement and innovation. We show that bidding for or delivering contracts to public sector clients has a positive effect on small businesses’ innovativeness. In contrast to linkages with universities, engagement in public procurement leads to more novel innovations, i.e., new-to-market innovations. We also extend prior research by corroborating the tender process. We show that firms with higher capabilities are more likely to bid or receive a public contract, whereas firms with government ownership are less likely to receive a public contract.

Taking our findings on university-industry linkages and public procurement together, we identify university-industry linkages and public procurement as two important policy strategies to achieve a more viable innovation ecosystem in emerging economies by supporting small businesses’ innovativeness, though both with different effects and with different firms as beneficiaries.

Literature review and hypotheses development

Small businesses in emerging economies: Institutional environment and uncertainty

Emerging economies are characterized by an institutional environment which creates strong barriers to business operation due to insufficient protection of property rights, high transaction costs and constrained resource supply (Armanios & Eesley, 2021). Such an environment generates high uncertainties along the dimensions of information, market and finance (Fu, 2015; Pertuze et al., 2019). More precisely, information uncertainty refers to the degree to which knowledge on new technology or knowledge required to use new technology is lacking (Hall & Martin, 2005). Building linkages with external partners, for example, enables a firm to access new technological information, thereby reducing information uncertainty. Market uncertainty is the degree to which a viable market for a product exists or can be created (Buddelmeyer et al., 2010). One strategy to tackle market uncertainty is the provision of governmental information provided in guidelines on promising technological paths such as green technology, or the provision of technical requirements of targeted products in public procurement. Financial uncertainty is the degree to which sufficient R&D funding can be secured (Pertuze et al., 2019). External financing from governmental sources, for instance, can make a big difference between project continuation and being put on hold (O'Connor & Rice, 2013). All three types of uncertainty are temporarily interlinked (Morone, 1993) and are known to be barriers to innovation (Feng & Johansson, 2017; Ngyuyen & Jaramillo, 2014). While large firms are more likely to circumvent such uncertainties as they have abundant internal resources, allowing them to create institutional substitutes (Fu, 2015; Liu et al., 2014), small businesses are less able to do so, reflecting their high resource scarcity (Herrmann et al., 2020; Nooteboom, 1993). Hence, many emerging economies are characterized by a vast majority of small businesses which are not innovative and often in need of catching up (Steinfeld, 2004). At the same time, though, small businesses have a potentially strong role in innovation – not because smallness per se creates an economic advantage, but because the greater number of businesses implies the potential for more innovation.Footnote 1 Encouraging innovation of small businesses is therefore central to policy initiatives to stimulate economic development and technological upgrading at the local, regional and national level (Audretsch & Thurik, 2001; Jones & Tilley, 2003; Lechevalier et al., 2014; Storz & Schäfer, 2011).

In the following, we analyze whether and how small businesses benefit from two distinct policy strategies which reduce uncertainty. We first analyze a policy strategy reducing information uncertainty through university-industry linkages, and then a policy strategy reducing information, market and financial uncertainties through public procurement. Following previous literature, we assume that high uncertainty is linked to lower levels of innovation novelty, and that low uncertainty is linked to higher levels of innovation novelty (O'Connor & Rice, 2013; Stockstrom & Herstatt, 2008).

Exploring new knowledge: Building up linkages to universities

Linkages to universities substantially reduce information uncertainty, in particular of technological information uncertainty, as they provide firms with information on recent technological developments, possible applications of newly developed technology and knowledge which is required to comprehend new technology (Fu, 2015). Consequently, they allow firms better to access external knowledge and to explore new ideas (Aschhoff et al., 2013; Hong & Su, 2013).Footnote 2

Recent studies on emerging economies show that linkages to universities help carry out large innovative steps (Kafouros et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2019). For example, Fischer et al., (2019a) show that top universities in Brazil contribute substantially to technological activities, and D'Costa (2006) points out the need of establishing strategic university-industry linkages for Indian firms to move up the value chain. Within China, the 985 and 211 programs for elite universities (The State Council, 2015; Wu, 2007, 2010) have contributed to more innovation on the firm level.

However, the vast majority of these studies focuses on large and innovative firms, and less on small businesses (Kafouros et al., 2015; Tang et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2019). This difference matters, as small businesses have less opportunities to reduce uncertainty in the dimensions of information, market and finance. While linkages to universities reduce information uncertainty, market and financial uncertainties still remain. Even if small businesses may indeed receive novel ideas from university partners and may start to explore them, market and financial uncertainties last. These remaining uncertainties may refrain them from undertaking more novel and risky innovation projects (Ngyuyen & Jaramillo, 2014). We therefore expect that linkages of small businesses to universities support innovation, but only innovation with a lower degree of novelty. This leads us to our first hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 1 Linkages to universities are likely to enhance small businesses’ innovation, but only for new-to-firm innovation.

Resource scarcity and the role of capabilities

Building up linkages to universities provides new opportunities, but entails opportunity costs. Searching activities take the management’s attention away from other internal activities (Alvarez & Busenitz, 2001), and require substantial resource commitments (Laursen & Salter, 2006). Given that small businesses are resource scarce, they may not be capable in gaining from such linkages (Herrmann et al., 2020; Rothwell & Dodgson, 1991). Hence, while innovation policies may support university-industry linkages, and while these linkages may reduce information uncertainty, to respond to these strategies requires substantial resources (Cunha et al., 2014; Pollock et al., 2013; van Burg et al., 2012). Indeed, prior research has shown that small businesses are often disadvantaged in benefiting from innovation policies (Wang et al., 2017).

The resource-based view of the firm posits that a firm’s resources and capabilities shape whether and how a firm may appropriately adapt, integrate, and reconfigure internal and external knowledge (Teece et al., 1997; Teece & Pisano, 1994; van Burg et al., 2012). Following Amit and Schoemarker (Amit & Schoemaker, 1993: 35), we define capabilities as the firm’s capacity to deploy resources for a desired end result such as innovation (Helfat & Winter, 2011).

There are numerous capabilities of firms which matter for a firm’s competitiveness such as a firm’s connective capacity or a firm’s transformative capacity (Lichtenthaler & Lichtenthaler, 2009). In the case of drawing knowledge from external partners, like in the case of building up linkages to universities, it is especially the firm’s absorptive capacity which matters (Lichtenthaler & Lichtenthaler, 2009) as this capacity defines how a firm is capable to acquire, assimilate and utilize the knowledge provided by the university partner (Cohen & Levinthal, 1989; Lane et al., 2006).Footnote 3

Firms with higher capabilities are more capable to combine various information which is essential to gain from the provided knowledge which needs to be evaluated, absorbed and incorporated into the existing knowledge base, and apply it to commercial ends (Cohen & Levinthal, 1989; Zahra & George, 2002). This requires, for example, a stock of human capital or internal R&D investment (Barney & Clark, 2007). Accordingly, firms with higher capabilities are more likely to benefit from collaborative efforts (Wang et al., 2015). We therefore expect that a firm’s capabilities moderate the relationship between linkages to universities and small businesses’ innovation. This leads us to the second hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 2 Linkages to universities are more likely to enhance new-to-firm innovation of small businesses with higher capabilities.

Exploiting new knowledge: Public procurement

Public procurement contracts reduce various forms of uncertainty. First, they reduce information uncertainty because calls for tenders in public procurement emphasize the technical requirements of the targeted products (Edler & Georghiou, 2007: 960). Moreover, they reduce market and financial uncertainties as innovative prototypes can be commercialized, and as economies of scale effects lower costs (Aschhoff & Sofka, 2009).Footnote 4

The underlying idea of public procurement is very simple – given that public spending occurs anyway and reaches large amounts in most countries, its redirection towards more innovative purchase products could create new markets for innovative solutions without additional spending (Czarnitzki et al., 2018). Edler & Yeow, (2016) note that public procurement may be particularly effective for more substantial forms of innovation where entry and learning costs tend to be higher, if the challenges linked to the bidding process such as the adequate selection of firms or the learning of the buying organisation are solved. Even only an increase in the number of bidders can drive up competition and the variety of new product development if transparent selection mechanisms are at work, hereby increasing the potential for innovation (Grimm et al., 2006). It is against this background that public procurement has received strong attention as a potentially favourable strategy to support firm-level innovation (Aschhoff & Sofka, 2009; Czarnitzki et al., 2018; Georghiou et al., 2014).Footnote 5

For small businesses in emerging economies, public procurement may be even more important than for large and innovative firms as these contracts not only substantially reduce information uncertainty, but also almost eliminate market and financial uncertainties.Footnote 6 Indeed, the highly segmented and unpredictable nature of markets within emerging economies (Fu, 2015), along with an often insufficient market demand, unfair competitive practices, the abrogation of contracts, the violation of intellectual property rights (Guo, 1997; Howell, 2018), increase the risk of engaging in innovation for smaller, resource scarce businesses substantially. Hence, public procurement aiming at opening up new markets while guaranteeing a certain amount of sales may be an important path to build up innovation capabilities of small businesses, as it addresses uncertainty comprehensively. We therefore expect that public procurement enhances more major forms of innovation.

An important concern, however, pertains to the tender process (Edler & Yeow, 2016; Edler & Georghiou, 2007). This holds true in particular within emerging economies where institutions tend to be weak, and the political capacity to implement innovative procurement policies may be underdeveloped (Aschhoff & Sofka, 2009; Czarnitzki et al., 2018; Kattel & Lember, 2010). Hence, we only expect a positive effect of public procurement if government sales contracts are awarded based on their capabilities. This means that businesses which have lower innovation capabilities but are close to the government should not be preferred and, vice versa, businesses which have higher innovation capabilities should be selected. Doing so, rent-seeking should be discouraged. This leads us to our third hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 3 Bidding for or delivering contracts to public sector clients helps enhance small businesses’ innovation, in particular for new-to-market innovation, if the tender process is transparent.

Data and measures

Empirical setting and data

Our empirical analysis is based upon a sample of 926 Chinese small businesses within the manufacturing industries. We developed this sample from the World Bank Enterprise Survey China (2012) from which we have detailed information on small businesses’ innovation as well as on their engagement in linkage formation activities and in public procurement. To the best of our knowledge, this survey is the only innovation survey which covers country-wide data, and includes both innovative and non-innovative firms. This property allows us to understand the effect of the two policy strategies – university-industry linkages and public procurement – causally.

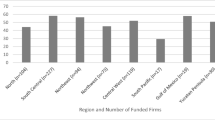

This survey follows the standardized questions of the Oslo Manual (OECD, 2005) upon which the widely used Community Innovation Survey (CIS) is based. It covers a three-year period from 2009 to 2011. Firms have been selected based upon a stratified random sampling method with three levels of stratification: Stratification by firm size divides the population of firms into three groups of small (5 to 19 employees), medium (20 to 99 employees), and large firms (more than 99 employees).Footnote 7 Stratification by geographical location reflects the distribution of non-agricultural economic activity, resulting in 25 middle-sized and large cities. Stratification by industry reflects the distribution of manufacturing and service industries as measured by the Gross National Income (at the 2-digit level according to ISIC revision 3.1; see World Bank, 2009). As a result, the World Bank Enterprise Survey China (World Bank, 2012) provides a nationwide sample of 2700 Chinese private firms in the manufacturing and service industries. Given that the innovation survey was conducted only in the manufacturing industries, we restrict our sample to 1692 manufacturing firms. According to China’s National Industrial Classification System, manufacturing firms with less than 300 employees are classified as small businesses (NBS, 2011). We therefore drop firms with more than 300 employees, restricting our sample to 1438 firms. We further drop observations with a “don’t know” answer or missing values. This procedure lowers our sample size to 926 small businesses with an average of 82 employees (median = 65) in 2011.

The use of this dataset has three important advantages: First, there is, to our best knowledge, no other survey in terms of firm size, geographical and industrial coverage which covers innovation activities and is comparable to the CIS survey. Thus, this dataset allows us to build up our knowledge of the CIS survey, in particular as patents and scientific publications are severally biased towards large firms (Bound et al., 1982). While the Chinese government has carried out innovation surveys which are similar to the CIS survey, they are not publicly available. Second, this dataset allows us to distinguish between new-to-firm and new-to-market innovations. This is important because overall estimates may underestimate innovation activities.Footnote 8 Third, since our data also provide linkage information on firms that did not introduce any product innovation, we are free from selection bias concerns; i.e., that only innovative firms were asked about their linkages to universities (Robin & Schubert, 2013). Given the cross-sectional data structure, we complemented these data with information on the number of universities, on the number of MBA programs, and on city-level population data (Ministry of Education of China, 2008; China National Economic Census, 2008) in order to construct instrument variables (IV).

Finally, we made strong efforts contextualizing our data. We carried out field visits, conducted semi-structured interviews with external key informants from universities, intermediaries, industries, and Chinese local government authorities, and obtained information from experts at the World Bank Enterprise Survey Unit. These complementary data sources helped us to interpret our results (see Appendix Table 8 for the list of data sources).

Dependent variables

Following the standard practice of identifying innovators as those firms which generate commercially successful new products or services, we measure our dependent variable, innovation performance, with the share of annual sales in 2011 which is attributed by the firms to new products (including services) having been introduced between 2009 and 2011 (Klingebiel & Rammer, 2014; Love et al., 2014; Mairesse & Mohnen, 2003; Robin & Schubert, 2013). It stands for the overall innovation performance without differentiating the degree of novelty of innovation.

To differentiate between degrees of novelty, i.e., minor and major innovations, we follow the CIS practice which has been widely used in previous studies (see e.g., Klingebiel & Rammer, 2014; Sadowski & Sadowski-Rasters, 2006). Firms were asked whether their new products are their own version of a product already supplied by another firm (i.e. products only new to the surveyed firm). Product innovations only new to the firm are minor innovations whereas product innovations new to the market are major innovations. We then differentiate between new-to-firm and new-to-market innovation performance. The former is the share of annual sales in 2011 due to new-to-firm products or services introduced between 2009 and 2011; the latter is the share of annual sales in 2011 pertaining to new-to-market products or services introduced between 2009 and 2011.

Independent variables

Following the theoretical development in the literature review, we investigate (a) university-industry linkages as a means of enhancing the firm’s innovation by reducing information uncertainty, and (b) public procurement as a means of enhancing the firm’s innovation by reducing information, market as well as financial uncertainties.

University-industry linkages: We develop a dummy and define university-industry linkages equal to one if a firm implemented an idea from external sources such as universities or research institutes (Tang et al., 2019). From expert interviews we know that these ideas often originate from the universities’ professors who consult firms as a “trouble shooter”, based on their past collaborative experience with the firm.

Public procurement: We use government contract as a proxy for public procurement. We follow previous work (Georghiou et al., 2014) and set a dummy variable equal to one if a firm was bidding for or delivering contracts to public sector clients in 2011.

Moderators

In line with previous studies, we measure firm capabilities with the stock of human capital and the R&D investment level (Lane & Lubatkin, 1998; Zahra & George, 2002), resulting in two moderators. One, we differentiate firms between high and low capabilities by taking the mean split on the number of employees in 2011. Firms with more employees have a broader internal knowledge base and therefore having higher capabilities (Lane & Lubatkin, 1998). Two, we classify a firm with high capabilities if the firm reported R&D expenditure and a firm with low capabilities if otherwise (Zahra & George, 2002).

Control variables

We control for a number of firm-specific characteristics. To account for firm heterogeneity within small businesses, we control for firm size with log of employees in 2011. As firm age matters for firm-level innovative output (Kotha et al., 2011), we measure firm age by the log of firm age in 2011. We use a set of industry dummies as controls for industry (2-digit ISIC (rev. 3.1)), based on the entries of survey respondents. We control for firms’ endowment as measured by the log of total sales in 2009 and employee skills measured by the average year of education of a typical permanent full-time production worker. A firm’s innovation input is likely to shape firm-level innovation output. In line with previous literature (De Jong & Freel, 2010; Eun et al., 2006), we measure firm’s R&D intensity to indicate the level of innovation input by calculating the log of firm’s R&D intensity measured by R&D expenditure per permanent employee in 2009 (Mairesse & Mohnen, 2003). Since access to finance has been shown to affect firm performance positively (Mina et al., 2013), we add a dummy variable to indicate whether a firm has an overdraft facility and a dummy variable to indicate whether a firm has a line of credit or a loan from a financial institution. As firms with an internationally recognized quality certification such as ISO 9000 have demonstrated their ability in producing high quality products and might be more innovative, we also use a dummy variable to control for this aspect (International quality certification). The previous literature suggests that linkages with other firms and internal development are related to the innovativeness of firms (Fitjar & Rodriguez-Pose, 2013; Jensen et al., 2007). We add a dummy variable to indicate whether a firm developed products in co-operation with suppliers and/or with client firms (linkages with others); and a dummy variable to indicate whether a firm developed/adapted an in-house product and implemented an idea from internal R&D (internal development).Footnote 9

In addition, there are a number of control variables which are of special importance within an emerging economy context. This refers first to the role of foreign technology for growth and innovation (Fu et al., 2011). Technology licensed from a foreign-owned company is equal to one if the firm licensed the technology from a foreign firm (excluding office software). Given the predominance of business groups in emerging economies, the literature attributes their origin to underdeveloped market institutions and high transaction costs so that firms belonging to a business group may feel a lesser need for building up linkages to universities (Eom & Lee, 2010). We therefore include a dummy variable to indicate whether a firm is part of a business group. As previous work found that firm ownership is negatively related to firm innovation (Choi et al., 2011), we use a dummy variable which indicates a firm’s government ownership. To take account for China’s interregional heterogeneity (Kafouros et al., 2015), we add city dummies (and province dummies when using the instrument variable). As firms tend to invest their resources on government-related regulatory work (Xie et al., 2015), the time dealing with different government regulations variable includes regulatory work on taxes, customs, labor regulations and licensing, and may negatively affect the innovation output of firms if resources are misallocated (Feng & Johansson, 2017; Xie et al., 2015). We therefore include the percentage of the total senior management’s time spent on dealing with requirements imposed by government regulations in a typical week and its square term to take non-linearity into account. The survey questions for all variables are listed in the Appendix Table 9.

Method

In order to estimate the effects of university-industry linkages and public procurement on innovation, we first estimate our baseline regressions as if university-industry linkages and public procurement were exogenous variables. We then proceed with strategies to deal with endogeneity separately. When analyzing the moderating effect of firm capabilities, we run a sample split analysis. We conduct the following general model to capture the determinant of innovation:

In this formula, Yi denotes innovation outcome, i.e., a firm’s innovation performance. UILi denotes university-industry linkages and PPi denotes public procurement. X is a vector of firm-level control variables likely to influence the outcome variables. In addition, we control for region (γ) and sector (λ) fixed effects. εi is an error term. In the baseline estimation, we use Tobit regressions for estimating innovation performance in order to respond to censoring issues.Footnote 10 We also employ OLS regression models and the results are very similar.

A number of previous studies deal with university-industry linkages and firm-level innovation in emerging economies without taking endogeneity into account (Freitas et al., 2013; Hong & Su, 2013; Lee et al., 2010; Liang & Liu, 2018). This means that, if we identify the effect of university-industry linkages on a firm’s innovativeness, this may be simply due to the fact that only innovative firms self-select into these linkages. We want to exclude endogeneity in order to understand whether also non-innovators benefit from linkages to universities. We addressed endogeneity by employing an instrument variable approach. In the first stage, we regressed UIL on the instrument variable (Z) and exogenous variables (X). In the second stage, we regressed innovation performance on the estimated variable (UIL^) and the same set of exogenous variables (X). Our instrument is university density which had been used in prior research (Robin & Schubert, 2013).Footnote 11

With regard to public procurement, we employ matching methods. We cannot use regression methods like in the case of university-industry linkages as instruments for public procurement have not been established. Instead, we follow the common practice of using matching methods (Czarnitzki et al., 2018; Heckman et al., 1997). Specifically, we make use of four different matching algorithms (nearest neighbor matching; radius matching; kernel matching and stratification matching) to estimate the average treatment effect on the treated firms (i.e., firms which bade or delivered a public contract) with regard to their innovation performance. We first use a probit model to estimate the propensity of a firm bidding for or delivering contracts to public sector clients with a set of observable firm-level characteristics, and then compute the propensity score for each firm.Footnote 12 This matching method allows us to construct the counterfactual group based upon observable characteristics (see similar studies, e.g., Dehejia & Wahba, 2002; Rosenbaum & Rubin, 1983).

Analysis and results

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics, and Table 2 provides a pairwise correlation table. Most firms in our sample are founded in the early 2000s with an average of 82 employees in 2011 and a very low R&D intensity with a median of 0.1 thousand Yuan per employee (i.e., 15 USD per employee). 4% of firms have government ownership. The average educational attainment of production workers corresponds to a high school level, and graduates even with a bachelor’s degree are rare. Given these firm characteristics, it is surprising how intense the innovation efforts are: About 26% of firms report having built up linkages to universities to develop new products, and about 10% report having bid for or delivered a public procurement contracts to public sector clients. About 11% of the annual sales originate from new products. About half of the firms report the development of new-to-firm product innovation and the other half new-to-market product innovation.

University-industry linkages and small businesses’ innovation

Table 3 presents statistical tests for the first hypothesis developed in Section 2. We find statistical support for our hypothesis. We find that linkages to universities enhance small businesses’ innovation, in particular new-to-firm innovation. To be more specific, in our baseline estimation (Table 3, column 1–3), linkages to universities show a positive coefficient for new-to-firm innovation. Using university density as an instrument (Table 3, column 4–6), we find that university-industry linkages have a positive effect on new-to-firm innovation (Table 3, column 5).Footnote 13 This effect is economically large: The annual sales attributed to such incrementally innovative products is about four times larger for firms which have built up a linkage to a university, compared with firms which did not built up any linkage. This result is striking as it indicates that also firms which have been non-innovators before they built up linkages to universities benefit from these linkages. These results remain if we use other instruments and other outcome measures (see Appendix Tables 11–12). We discuss our findings in the discussion and conclusion section.

Hypotheses 2 predicted that, when firm capabilities are higher, linkages to universities more likely to be associated with small businesses’ new-to-firm innovation. We find support for this hypothesis. Following our theoretical argument, we conduct sample split analyses along two dimensions: We split our sample according to the mean number of employees in 2011 (Table 4) and whether a firm reported any R&D expenditure (Table 5). In all sample split analyses, we account for the endogeneity issue with university density as the instrument variable.Footnote 14 Linkages to universities have a positive effect on small businesses’ new-to-firm innovation when firms have more employees and more R&D investment. Thus, the impact of linkages to universities is not universal. Instead, within small businesses, firms with higher capabilities are more likely to benefit more from linkages to universities (Barney & Clark, 2007).

Exploiting new knowledge: Public procurement and small businesses’ innovation

Our findings also provide support for our third hypothesis. Table 6 shows that firms bidding for or delivering contracts to public sector clients are more innovative than firms which do not participate in public procurement activities. Comparing the treated firms (i.e., firms which bade for or delivered a contract to public sector clients) with the counterfactual firms (i.e., firms which did not bid for or did not deliver a contract), the treated firms are more innovative in terms of new-to-market innovation, hence, they benefit by more major forms of innovation. This finding is in line with our expectation and is robust to all four matching algorithms.

Next, we analyze whether contracts are awarded based on their capabilities, this means, whether businesses which have higher innovation capabilities are selected. In turn, businesses which have lower innovation capabilities but which are close to the government should not be preferred in the tender process. Table 7 shows the result of our propensity score model and the differences in the characteristics of firms. We observe that firms which did bid for or deliver contracts differ in a number of important characteristics from those which did not: First, treated firms are characterized by a higher R&D intensity prior to the treatment. Thus, government contracts do work as an incentive to attract firms with higher innovation capabilities. Second, treated firms tend to be private firms, and government ownership shows a negative coefficient. In line with previous literature (Rong et al., 2017), ownership may be interpreted as an indicator of higher capabilities to innovate. Third, public procurement opens up new markets (which is why market uncertainty is reduced) so that firms need to have scaling up capabilities. Indeed, we find that for a number of indicators, treated firms have stronger scaling up capabilities, as for instance in terms of enlarging workforce, of using ICT for business transactions and of sharing information with suppliers as well as clients (Appendix Table 14). Taken together, our results seem to indicate a marketization of procurement policies where performance principles matter more than ownership. Hence, we attribute our results of positive innovation effects to the tender process. This may explain why we find contrasting evidence to Fernández-Sastre and Montalvo-Quizhpi (2019). We discuss and compare our findings in the discussion and conclusion section.

Discussion and conclusion

Theoretical implications

Our main finding is that two important policy strategies – university-industry linkages and public procurement – have been effective in stimulating small businesses’ innovation. More specifically, the former enhances new-to-firm innovation, and the latter new-to-market innovation. We attribute this finding to the different degrees of uncertainties these policies address.

Our results have implications for the related literatures on university-industry linkages, public procurement and the design of strategies to support innovation of small businesses in emerging economies. While previous work on university-industry linkages and firm innovation are mostly concentrated on advanced economies (Eom & Lee, 2010; Fitjar & Rodriguez-Pose, 2013; Haus-Reve et al., 2019; Jensen et al., 2007; Scandura, 2016; Szücs, 2018), we do observe an increasing number of studies in emerging economies. However, the majority focuses on large and innovative firms (Fischer et al., 2019a; Kafouros et al., 2015). We address this gap by focusing on small businesses. Our finding is complementary to a recent paper of Fischer et al., (2019a) which indicates an increasing embeddedness of universities in Brazil, but we go one step further by taking resource scarcity, degrees of novelty as well as boundary conditions into account. We show that the effect of university-industry linkages on firm-level innovation might have even been underestimated: It is not only the innovative, patenting and more resource-rich incumbent which benefits from linkages to universities (Kafouros et al., 2015; Tang et al., 2019), but also the small and less innovative firm. Hence, universities seem to fulfill a double role: To stimulate more major forms of innovation for large and innovative firms (Fischer et al., 2019a; Kafouros et al., 2015; Tang et al., 2019), and to stimulate minor forms of innovation – which is linked to learning, modification and upgrading – of small businesses. Our finding is consistent with what we observed in the field: University professors reported to provide problem-solving services for small businesses, for example by consulting them on how to improve products already existing in the market. According to our interviews, small businesses often adapt existing foreign products in the market which may explain why the surveyed firms answer that the new product which they develop with inputs from universities are new to the firm – indeed, they are only new to the respective firm, not new to the market.Footnote 15

Moreover, we contribute to a better understanding of which small firms are benefitting most from the formation of linkages. We show that within small businesses, it is especially those firms equipped with a higher level of capabilities which benefit from linkages to universities by becoming more innovative. Thus, our finding underscores the importance of a firm’s internal capabilities which are crucial for them to being able to act upon policy strategies (Cunha et al., 2014; Pollock et al., 2013). We also tested whether small businesses engaging in linkages may pursue alternative strategic goals such as better access to financial loans other than innovation. However, our results do not show a significant association (Appendix Table 15). This makes us confident that university-industry linkages are not grounded in other strategic objectives.

We further contribute to the debate on public procurement to enhance innovation of small businesses. While the role of public procurement continues to interest innovation researchers (Aschhoff & Sofka, 2009; Czarnitzki et al., 2018; Edler & Georghiou, 2007; Georghiou et al., 2014), little previous work has related public procurement to emerging economies, with the important exceptions of Fernández-Sastre and Montalvo-Quizhpi (2019) and Rocha (2018). Like Fernández-Sastre and Montalvo-Quizhpi (2019), we also do not find an effect on a firm’s overall innovativeness, but we find an effect on new-to-market innovation. This is an important finding as it shows that the effect of innovation policies needs to be measured carefully. Our result that bidding for or delivering contracts to public sector clients leads to more major innovations is important as the firms in our sample do not carry out these innovative activities within producer-user interactions (Lundvall, 1985). The finding that Brazilian suppliers with a public procurement contract show a higher innovation intensity (Rocha, 2018) may be caused by the fact that all suppliers belong to one leading public energy company which announced a procurement policy under the local content goals. In contrast, in our sample, it was not one public Chinese company calling for innovative procurement of its suppliers, but small businesses individually interacted with public sector clients. We demonstrate that even in this setting with less learning opportunities, bidding for or delivering contracts to public sector clients may improve small businesses’ innovation performance substantially. We attribute our finding to the substantial reduction in information, market and financial uncertainties.

Finally, we could not observe rent-seeking in the tender process in which firms bade for or delivered contracts to public sector clients. This is, on one hand, surprising, given that China’s economic environment is characterized by a weak nature of its institutional set-up. Also, China has not yet signed the WTO Government Procurement Agreement. On the other hand, there is a large and rich literature in political science on the technocratic background of officials and “meritocratic bureaucracies” (Evans, 1995). Against this background, Noland and Pack (2005) suggest that China’s management of public procurement may be in line with the experience of post-war East Asian industrial policy which linked purchasing activities to demanding quality standards to ensure continued innovation in the production of targeted products. These mechanisms may help rule out rent-seeking (Montinola et al., 1995; Noland & Pack, 2005).

Our results on the effects of university-industry linkages and public procurement are also relevant for the ongoing discussion on foreign technologies and innovative upgrading. On the one hand, it has been argued that it is more efficient for emerging economies to acquire foreign technology developed in advanced market economies, given that innovation tends to be risky and costly (Barro & Sala-i-Martin, 1995; Eaton & Kortum, 1995). On the other hand, as innovation essentially relies on a country’s absorptive capacity, foreign technology imports may not be beneficial (Atkinson & Stiglitz, 1969; Basu & Weil, 1998). Fu et al. (2011) and Li (2011) reply to this discussion by showing that indigenous and foreign efforts are complementary. We contribute to this literature by showing that university-industry linkages and public procurement, i.e., (mainly) domestic technology purchases, contribute to firm-level innovation. Both policies may be important tools to enhance a country’s indigenous innovative capacity. This, in turn, may be an important channel to benefit a country’s absorptive capacity, thereby enhancing the “complementary side” of foreign technology acquisition.

Managerial and policy implications

Our analysis shows the impact of university-industry linkages on the creation of new-to-firm innovation. One may argue, like Robin and Schubert (2013), that “public-private collaborations should not be encouraged at all costs, since they may not sustain all forms of innovation”. However, policy makers may encourage university-industry linkages even if it enhances only innovations with a lower degree of novelty because universities seem to be important solution providers for firms. If this is not the policy’s objective, incentive structures to enhance more major innovations should be created. At the same time, in emerging economies with high market and financial uncertainties, innovative public procurement may be a “ready-at-hand” strategy to enhance more major forms of innovation even of small businesses, under the condition that the government ensures a transparent tender process.

Limitations and future research

One limitation of our research is that innovation measurement relies on subjective statements (Cirera, 2015). There are other more objective measures which can capture innovation and its degree of novelty, as for instance invention patents, utility models or scientific publications. At the same time, the concern of subjectivity needs to be counterweighted against the advantage of gaining insights into the innovation behavior of small businesses which usually do not patent or publish scientific publications. If we want to develop a more comprehensive picture of innovation in China, we need to rely on surveys which allow us to capture innovations which may not be captured by patents or publications, and to differentiate between different degrees of novelty. Second, our data do not allow us to conduct meaningful analysis on the moderating effect of regional institutional heterogeneity. This is due to the data sampling framework which reflects the geographical distribution of economic activities. While our results on both policy strategies are encouraging, future research should consider regional institutional heterogeneity as one important boundary condition. A further concern is that our data, like the CIS data, rely on observable characteristics. This is an important weakness, given that informal networks play an important role in China (Nee & Opper, 2012). An important area for further research is to conceptualize informal factors influencing firm-level innovation such as the personal networks of company or university presidents, and informal networks between firms which buy and sell in public procurement.

While these and other future research directions are important to develop a better understanding of the drivers of innovation in emerging economies, our results help existing efforts to unravel how strategies addressing different types of uncertainties in the innovation process contribute to raising innovative capabilities of small businesses in emerging economies.

Notes

For example, 90.2% of firms in Chile are small firms; in Brazil and Czech Republic, their share is about 99% of all businesses. Also in China, the vast majority of firms is small or medium-sized; more than 95% of firms have less than 300 employees (National Bureau of Statistics, 2014), and they create 80% of urban employment (Xinhua News Agency, 2010).

We conducted an extensive literature review on university-industry linkages and firm innovation. We find that there is much research on university-industry linkages and firm innovation in developed economies than in emerging economies (see e.g. Fitjar and Rodríguez-Pose, 2013 on Norway; Fukugawa, 2013 on Japan; Jensen et al., 2007 on Denmark; Thursby & Thursby, 2011 on US; Scandaura, 2016 on UK; Szücs, 2018 on EU countries).

Capabilities are often subdivided into ordinary (or operational) and dynamic capabilities (Helfat & Winter, 2011), with dynamic capabilities defined as the set of capabilities that allows the firm to reconfigure its existing resource and capability base (Teece et al., 1997). However, Helfat & Winter (2011) have convincingly argued that the distinction between ordinary and dynamic capabilities is blurred because, on one hand, radical and non-radical changes are continuously occurring, and, on the other, both ordinary and dynamic capabilities may support both types of changes. We therefore decided to use the more general term capabilities.

Public procurement includes purchases of innovative products such as ICT or green products, as well as standard products with usually no innovation involved, such as pencils or printing ink (Aschhoff & Sofka, 2009). Hence, while public procurement spending also includes traditional technologies and products, it may create an opportunity for innovation if it is confined to innovative products and services (Caloghirou et al., 2016; Czarnitzki et al., 2018; Georghiou et al., 2014). See examples from the China Government Procurement Webpage [Zhongguo Zhengfu Caigou Wang]: http://www.ccgp.gov.cn/

In China, the share of public procurement spending was 3.1% of GDP in 2015. According to OECD (2018), China’s total government support to business R&D as a percentage of GDP was 0.13% in 2015. This includes both direct government funding for business R&D and tax incentives for R&D. The latter accounted for 49% of total government support for business R&D in China. Accordingly, direct government funding for business R&D is about 0.067% of GDP whereas tax incentives for R&D is about 0.066% of GDP in 2015 (OECD, 2018).

China has developed very comprehensive catalogues specifying government demand for new products and services which facilitates the participation of small businesses (Edler & Georghiou, 2007). While being deeply concerned by its protectionism from China’s major trade partners (which eventually led to the catalogues being abandoned), these catalogues reduced information uncertainty because they help firm to choose a more promising technological path.

It is worth mentioning that the firm size classification used by the World Bank Group in this survey is neither consistent with the firm size classification in China (see: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/tjbz/201801/t20180103_1569357.html) nor with that in the European Union (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/structural-business-statistics/structural-business-statistics/sme).

We consider new-to-firm and new-to-market innovation as two categories on an ordinal scale of innovation, with new-to-market innovation having a higher degree of novelty. Conceptually, new-to-market innovation also includes innovation which is new-to-firm. Thus, we cannot exclude that new-to-market innovation may be overestimated. We thank one anonymous reviewer for pointing out this limitation.

We also tested further a more “loose” definition of internal development: i.e., dummy = 1 if a firm developed or adapted products in-house, or if a firm implemented an idea from internal R&D. Using “loosely” defined internal development in the regression analysis does not qualitatively change our results. Results can be provided upon request.

Innovation performance is measured by the share of sales due to new product innovation. Thus, for firms which did not introduce any new product innovation, the innovation performance is censored at zero. In the regression analysis, in order to avoid losing many observations, we replaced zero with 0.1 before we did the log transformation. However, it does not change the fact that this variable is censored. Thus, Tobit regression is more appropriate.

The intuition is that university density at the city level directly affects a firm’s opportunity to establish a linkage with a university. However, the existence of linkage opportunities at the city level is unlikely to have a direct impact on the innovation performance of a specific firm.

Explanatory variables in the propensity score model should be selected carefully in order to minimize the bias in resulting estimation (Heckman et al., 1997). Hence, only variables that are unaffected by the participation – in our case, bidding for or delivering new products to public sector clients - should be included in the model. As suggested by Caliendo and Kopeinig (2008), we include unaffected variables which are fixed over time (like firm ownership, industry) and variables which are measured before the treatment (like number of employees in 2009; total sales in 2009; R&D intensity in 2009). According to the propensity score and after the confirmation of common support, we use four different matching algorithms - nearest neighbor matching (random draw); radius matching (caliper = 0.05); kernel matching (bandwidth = 0.06) and stratification matching - to estimate the average treatment effect on the treated group, i.e., firms which bade for or delivered new products to public sector clients.

Appendix Table 10 shows the regression result of the first stage, UIL^. The coefficient of university density is statistically significant and F-statistics is beyond the conventional cut-off point of 10, confirming the relevance of our instrument. In the first stage, the coefficient of university density is negative. We expect it because our instrument also includes high-quality universities (which belong to 985 and 211 programs) at the city level. In an environment with strong hierarchical ranking of universities, small businesses are less likely to enter linkages as there is a status gap between high-quality universities and small businesses.

All first stage results for the sample split analyses are in Appendix table 13. We observe that our instrument is weak (i.e. first stage results show relevance, but F-statistics is below 10) among firms with below mean number of employees in 2011 (Table 4, column 4–6). We address this issue by using weak instrument robust inference which allows us to draw correct inference for UILˆ in spite of weak instrument (Andrew & Stock, 2018; Sun, 2018). Within the subsample of firms without reporting any R&D expenditure, the instrument is no longer relevant (see Appendix table 13, column 4). We find it intuitive because these firms do not engage in any R&D activities and therefore, linkages to universities may be less relevant for them.

We are grateful for one anonymous reviewer’s suggestion on exploring regional institutional heterogeneity. We have explored the moderating role of regional institutional heterogeneity. However, the large regional institutional differences between Eastern and Western China are not visible in our setting. Hence, it is not surprising that we cannot find any significant moderating effects. We believe this null effect is a statistical artifact due to the sampling, not a reflection of negligible regional differences.

References

Allard, G., Martinez, C. A., & Williams, C. 2012. Political instability, pro-business market reforms and their impacts on national systems of innovation. Research Policy, 41(3), 638-651.

Alvarez, S. A., Busenitz, L. W., 2001. The entrepreneurship of resource-based theory. Journal of Management 27(6), 755-775.

Andrews, I., & Stock, J. H. 2018. Weak instruments and what to do about them. In NBER summer institute 2018 methods lectures. Harvard University.

Armanios, D.E., & Eesley, C.E., 2021. How do institutional carriers alleviate normative and cognitive barriers to regulatory change? Organization Science, forthcoming.

Amit, R., & Schoemaker, P. J. H. 1993. Strategic assets and organizational rent. Strategic Management Journal, 14(1), 33-46.

Aschhoff, B., Baier, E., Crass, D., Hud, M., Hünermund, P., Köhler, C., Peters, B., Rammer, C., Schricke, E., Schubert, T., Schwiebacher, F., (2013). Innovation in Germany - results of the German CIS 2006 to 2010. ZEW-Dokumentation Mannheim 13-01. Working Paper.

Aschhoff, B., Sofka, W., 2009. Innovation on Demand – Can Public Procurement Drive Market Success of Innovations. Research Policy 38 (8), 1235-1247.

Atkinson, A. B., Stiglitz, J. E., 1969. A New View of Technological Change. The Economic Journal 79 (315), 573-578.

Audretsch, D. B., Thurik, A. R., 2001. What's New about the New Economy? Sources of Growth in the Managed and Entrepreneurial Economies. Industrial and Corporate Change 10 (1), 267-315.

Barney, J., Clark, D., 2007. Resource-based Theory. In: Barney, J., Clark, D., (Eds.) Resource-based Theory: Creating and Sustaining Competitive Advantage. Oxford University Press: New York.

Barro, R. J., Sala-i-Martin, X., 1995. Economic growth. Advanced Series in Economics. McGraw Hill: New York.

Basu, S., Weil, D. N., 1998. Appropriate technology and growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 113 (4), 1025-1054.

Bound, J., Cummins, C., Griliches, Z., Hall, B. H., & Jaffe, A. B. 1982. Who does R&D and who patents? (No. w0908). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Buddelmeyer, H., Jensen, P. H., & Webster, E. 2010. Innovation and the determinants of company survival. Oxford Economic Papers, 62 (2), 261-285.

Caliendo, M., Kopeinig, S., 2008. Some practical guidance for the implementation of propensity score matching. Journal of Economic Surveys, 22 (1), 31-72.

Caloghirou, Y., Protogerou, A., Panagiotopoulos, P., 2016. Public procurement for innovation: A novel eGovernment services scheme in Greek local authorities. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 103, 1-10.

Chinese Ministry of Finance, 2016. The Ministry of Finance issues a short brief of national government procurement for 2015 [available at: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2016-08/13/content_5099132.htm, in Chinese, accessed on Sep 14, 2018].

Choi, S. B., Lee, S. H., Williams, C., 2011. Ownership and firm innovation in a transition economy: Evidence from China Research Policy 40 (3), 441-452.

Cirera, X., 2015. Catching up to the Technological Frontier? Understanding Firm-Level Innovation and Productivity in Kenya. World Bank Group: Washington, DC.

Cohen, W., & Levinthal, D. 1989. Innovation and learning: The two faces of R&D. Economic Journal, 99 (397), 569-596.

Cunha, M.P.E., Rego, A., Oliveira, P., Rosado, P., Habib, N. 2014. Product Innovation in Resource-Poor Environments. Journal of Product Innovation Management 31, 202-21

Czarnitzki, D., Hünermund, P., Moshgbar, N., 2018. Public Procurement as Policy Instrument for Innovation. ZEW – Centre for European Economic Research Discussion Paper 18-001.

D'Costa, A. P., 2006. Exports, university-industry linkages, and innovation challenges in Bangalore, India. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3887.

De Jong, J. P. J., Freel, M., 2010. Absorptive capacity and the reach of collaboration in high technology small firms. Research Policy 39 (1), 47-54.

Dehejia, R. H., Wahba, S., 2002. Propensity score-matching methods for nonexperimental causal studies. Review of Economics and statistics 84 (1), 151-161.

Deng, P., & Zhang, S. 2018. Institutional quality and internationalization of emerging market firms: Focusing on Chinese SMEs. Journal of Business Research, 92, 279-289.

Eaton, J., Kortum, S., 1995. Engines of growth: Domestic and foreign sources of innovation. NBER Working Papers 5207, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Edler, J., Georghiou, L., 2007. Public procurement and innovation − Resurrecting the demand side. Research Policy 36 (7), 949-963.

Edler, J., J Yeow, J., 2016. Connecting demand and supply: The role of intermediation in public procurement of innovation. Research Policy 45(2), 414-426.

Eom, B. Y., Lee, K., 2010. Determinants of industry – academy linkages and, their impact on firm performance: The case of Korea as a latecomer in knowledge industrialization. Research Policy 39 (5), 625-639.

Eun, J. H., Lee, K., Wu, G., 2006. Explaining the “University-run enterprises” in China: A theoretical framework for university – industry relationship in developing countries and its application to China. Research Policy 35 (9), 1329-1346.

Evans, P. B., 1995. Embedded autonomy. Princeton University Press: New York.

Feng, X., Johansson, A. C., 2017. Political Uncertainty and Innovation in China. Stockholm School of Economics Asia Working Paper 44.

Fernández-Sastre, J., Montalvo-Quizhpi, F., 2019. The effect of developing countries' innovation policies on firms' decisions to invest in R&D. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 143, 214-223.

Fischer, B. B., Rücker Schaeffer, P., Vonortas, N. S., 2019a. Evolution of university-industry collaboration in Brazil from a technology upgrading perspective. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 145, 330-340.

Fischer, B. B., de Moraes, G. H. S. M., Rücker Schaeffer, P., 2019b. Universities' institutional settings and academic entrepreneurship: Notes from a developing country. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 147, 243-252.

Fitjar, R. D., Rodriguez-Pose, A., 2013. Firm collaboration and modes of innovation in Norway. Research Policy 42 (1), 128-138.

Freitas, I. M. B., Marques, R. A., de Paula e Silva, E. M., 2013. University-industry collaboration and innovation in emergent and mature industries in new industrialized countries. Research Policy 42 (2), 443-453.

Fu, X., 2015. China's path to innovation. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK.

Fu, X., Pietrobelli, C., Soete, L., 2011. The Role of Foreign Technology and Indigenous Innovation in the Emerging Economies: Technological Change and Catching-up. World Development 39 (7), 1204-1212.

Fukugawa, N. 2013. University spillovers into small technology-based firms: Channel, mechanism, and geography. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 38 (4), 415-431.

Georghiou, L., Edler, J., Uyarra, E., Yeow, J., 2014. Policy instruments for public procurement of innovation: Choice, design and assessment. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 86, 1-12.

Grimm, V., Pacini, R., Spagnolo, G., Zanza, M., 2006. Division into lots and competition in procurement. In: Dimitri, N., Piga, G., Spagnolo, G. (Eds.), Handbook of Procurement. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 168-192.

Guo, K., 1997. The Transformation of China’s Economic Growth Pattern – Conditions and Methods. Social Sciences in China 18 (3), 12-20.

Hall, J. K., & Martin, M. J., 2005. Disruptive technologies, stakeholders and the innovation value-added chain: a framework for evaluating radical technology development. R&D Management, 35 (3), 273-284.

Haus-Reve, S., Fitjar, R. D., & Rodríguez-Pose, A., 2019. Does combining different types of collaboration always benefit firms? Collaboration, complementarity and product innovation in Norway. Research Policy, 48 (6), 1476-1486.

Heckman, J. J., Ichimura, H., Todd, P. E., 1997. Matching as an econometric evaluation estimator: Evidence from evaluating a job training programme. The Review of Economic Studies 64 (4), 605-654.

Helfat, C. E., & Winter, S. G. 2011. Untangling Dynamic and Operational Capabilities: Strategy for the (N)ever-Changing World. Strategic Management Journal, 32(11): 1243-1250.

Herrmann, A.M., Storz, C. & Held, L., 2020. Whom do nascent ventures search for? Resource scarcity and linkage formation activities during new product development processes. Small Business Economics. [available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00426-9, accessed on 16 December 2020]

Hong, W., Su, Y. S., 2013. The effect of institutional proximity in non-local university – industry collaborations: An analysis based on Chinese patent data. Research Policy 42 (2), 454-464.

Howell, A., 2018. Innovation and Firm Performance in the People’s Republic of China: A Structural Approach with Spillovers. ADBI Institute Working Paper Series 805.

Jensen, M. B., Johnson, B., Lorenz, E., & Lundvall, B. Å., 2007. Forms of knowledge and modes of innovation. Research Policy 36 (5), 680-693.

Jones, O., Tilley, F. (Eds.), 2003. Competitive Advantage in SMEs: organizing for Innovation and Change. Wiley: Chichester.

Kafouros, M., Wang, C., Piperopoulos, P., & Zhang, M., 2015. Academic collaborations and firm innovation performance in China: The role of region-specific institutions. Research Policy 44 (3), 803-817.

Kattel, R., Lember, V. 2010. Public procurement as an industrial policy tool – An option of developing countries? Journal of Public Procurement 10 (3), 368-404.

Khanna, T., Palepu, K. G., & Sinha, J. 2005. Strategies that fit emerging markets. Harvard business review, 83 (6), 4-19.

Klingebiel, R., Rammer, C., 2014. Resource allocation strategy for innovation portfolio management. Strategic Management Journal 35 (2), 246-268.

Kotha, R., Zheng, Y., George, G., 2011. Entry into new niches: the effects of firm age and the expansion of technological capabilities on innovative output and impact. Strategic Management Journal 32 (9), 1011-1024.

Lane, P., Koka, B., & Pathak, S. 2006. The Reification of Absorptive Capacity: A Critical Review and Rejuvenation of the Construct. The Academy of Management Review, 31 (4), 833-863.

Lane, P. J., & Lubatkin, M. 1998. Relative absorptive capacity and interorganizational learning. Strategic Management Journal, 19 (5), 461-477.

Laursen, K., Salter, A., 2006. Open for innovation: the role of openness in explaining innovation performance among U.K. manufacturing firms', Strategic Management Journal 27 (2), 131-150.

Lechevalier, S., Nishimura, J., & Storz, C., 2014. Diversity in patterns of industry evolution: How an intrapreneurial regime contributed to the emergence of the service robot industry. Research Policy, 43 (10), 1716-1729.

Lee, S., Park, G., Yoon, B., Park, J., 2010. Open innovation in SMEs – An intermediated network model. Research Policy 39 (2), 290-300.

Li, X., 2011. Sources of External Technology, Absorptive Capacity, and Innovation Capability in Chinese State-Owned High-Tech Enterprises. World Development 39 (7), 1240-1248.

Li, Y., Georghiou, L., Rigby, J., 2015. Public procurement for innovation elements in the Chinese new energy vehicles program. In: Edquist, C., Vonortas, N. S., Zabala-Iturriagagoitia, J. M., Edler, J. (Eds.), Public Procurement for Innovation, 179-208, Edward Elgar Publishing.

Liang, X., Liu, A. M. M., 2018. The evolution of government sponsored collaboration network and its impact on innovation: A bibliometric analysis in the Chinese solar PV sector. Research Policy 47 (7), 1295-1308.

Lichtenthaler, U., & Lichtenthaler, E. 2009. A Capability-Based Framework for Open Innovation: Complementing Absorptive Capacity. Journal of Management Studies, 46 (8), 1315-1338.

Liu, X., Lu, J., & Chizema, A. 2014. Top executive compensation, regional institutions and Chinese OFDI. Journal of World Business, 49 (1), 143-155.

Love, J. H., Roper, S., Vahter, P., 2014. Learning from openness: The dynamics of breadth in external innovation linkages. Strategic Management Journal 35, 1703-1716.

Lundvall, B. Å., 1985. Product Innovation and User-Producer Interaction. Aalborg University Press: Aalbor.

Mairesse, J., Mohnen, P., 2003. R&D and productivity: a reexamination in light of the innovation surveys. DRUID Summer Conference, 12-14.

Mina, A., Lahr, H., Hughes, A., 2013. The demand and supply of external finance for innovative firms. Industrial and Corporate Change 22 (4), 869-901.

Montinola, G., Qian, Y., Weingast, B. R., 1995. Federalism, Chinese style: the political basis for economic success in China. World Politics 48 (1), 50-81.

Monux, D., Ospina, M., 2016. Chile. In: Monux, D., Uyarra, E. (Eds.), Spurring innovation-led growth in Latin America and the Carribean through public procurement, 184-208. Inter-American Development Bank.

Morone, J. G. (1993). Winning in high-tech markets: The role of general management. Harvard Business Press.

Motohashi, K., Yun, X., 2007. Federalism, Chinese style: the political basis for economic success in China China's innovation system reform and growing industry and science linkages. Research Policy 36 (8), 1251-1260.

National Bureau of Statistics, 2011. Statistical Classification for Large, Medium, Small and Micro Firms [available at: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/tjbz/201109/t20110909_8669.html, accessed on July 5, 2020]

National Bureau of Statistics, 2014. The Third National Economic Census Data Bulletin 1 [available at: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/201412/t20141216_653709.html, accessed on Sept 16, 2018].

Nee V., Opper, S., 2012 Capitalism from below: Markets and institutional change in China. Harvard University Press.

Ngyuyen, H., Jaramillo, P. A., 2014. Institutions and Firms’ Return to Innovation. Policy Research Working Paper WPS 6918.

Noland, M., Pack, H., 2005. The East Asian Industrial Policy Experience: Implications for the Middle East. Institute for International Economics Working Paper, 05-14. [available at: SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=871784 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.871784].

Nooteboom, B. 1993. Firm size effects on transaction costs. Small business economics, 5 (4), 283-295.

O'Connor, G. C., & Rice, M. P. 2013. Uncertainty and Radical Innovation. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 30 (S1), 2-18.

OECD, 2018. R&D Tax Incentives: China. Directorate for Science, Technology and Innovation, April 2018. [available at: http://www.oecd.org/sti/rd-tax-stats-china.pdf].

OECD, Oslo Manual, 2005. The measurement of scientific and technological activities. Proposes Guidelines for Collecting and Interpreting Innovation Data, Paris.

Pertuze, J.A., Reyes, T., Vassolo, R.S., & Olivares, N. 2019. Political uncertainty and innovation: The relative effects of national leaders' education levels and regime systems on firm-level patent applications. Research Policy, 48 (9), 103808.

Pollock, T., Baker, T., Sapienza, H. 2013. Winning an unfair game: How a resource-constrained player uses bricolage to maneuver for advantage in a highly institutionalized field. In Corbett, A.C. & Katz, J.A. (eds.) Advances in Entrepreneurship, Firm Emergence & Growth.

Ponomariov, B., 2014. Knowledge flows and bases in emerging economy innovation systems: Brazilian research 2005-2009. Research Policy 43 (3), 588-596.

Robin, S., Schubert, T., 2013.Cooperation with public research institutions and success in innovation: Evidence from France and Germany. Research Policy 42 (1), 149-166.

Rocha, F., 2018. Procurement as innovation policy and its distinguishing effects on innovative efforts of the Brazilian oil and gas suppliers. Economics of Innovation and New Technology 27 (8), 750-769.

Rong, Z., Wu, X., Boeing, P., 2017. The effect of institutional ownership on firm innovation: Evidence from Chinese listed firms. Research Policy 46 (9), 1533-1551.

Rosenbaum, P. R., Rubin, D. B., 1983. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 70 (1), 41-55.

Rothwell, R., Dodgson, M., 1991. External linkages and innovation in small and medium-sized enterprises. R&D Management 21, 125-138.

Sadowski, B. M., Sadowski-Rasters, G., 2006. On the innovativeness of foreign affiliates: Evidence from companies in The Netherlands. Research Policy 35 (3), 447-462.

Scandura, A. 2016. University–industry collaboration and firms’ R&D effort. Research Policy, 45 (9), 1907-1922.

Steinfeld, E. S., 2004. China’s shallow integration: networked production and the new challenges for late industrialization. World Development 32 (11), 1971-1987.

Stockstrom, C., & Herstatt, C. 2008. Planning and uncertainty in new product development. R&D Management, 38 (5), 480-490.

Storz, C., & Schäfer, S., 2011. Institutional Diversity and Innovation. Continuing and Emerging Patterns in Japan and China. London: Routledge.

Sun, L. 2018. Implementing valid two-step identification-robust confidence sets for linear instrumental-variables models. The Stata Journal, 18 (4), 803-825.

Szücs, F. 2018. Research subsidies, industry–university cooperation and innovation. Research Policy, 47(7), 1256-1266.

Tang, Y., Motohashi, K., Hu, X., Montoro-Sanchez, A., 2019. University-industry interaction and product innovation performance of Guangdong manufacturing firms: the roles of regional proximity and research quality of universities The Journal of Technology Transfer 1-41.

Teece, D. J., & Pisano, G. 1994. The dynamics capabilities of firms: an introduction. Industrial and Corporate Change, 3 (3), 537-556.

Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. 1997. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18 (7), 509-533

Terziovski, M., 2010. Innovation practice and its performance implications in small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in the manufacturing sector: a resource-based view. Strategic Management Journal 31, 892-902.

The State Council, 2006. Notice on Some Supporting Policies for Implementing National Guideline on Medium and Long-term Program for Science and Technology Development (2006-2020). [available at: http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2006-02/26/content_211553.htm, in Chinese, accessed on Sep 14, 2018].

The State Council, 2015. Overall Plan for Coordinately Advancing the Construction of World First-class Universities and First-class Academic Disciplines. [available at: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2015-11/05/content_10269.htm, in Chinese, accessed on Sep 14, 2018].

Thursby, J., & Thursby, M. 2011. University-industry linkages in nanotechnology and biotechnology: evidence on collaborative patterns for new methods of inventing. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 36 (6), 605-623.

Van Burg, E., Podoynitsyna, K., Beck, L., & Lommelen, T. 2012. Directive Deficiencies: How Resource Constraints Direct Opportunity Identification in SMEs. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 29(6), 1000-1011,

Wang, Y., Li, J., & Furman, J. L. 2017. Firm performance and state innovation funding: Evidence from China’s Innofund program. Research Policy, 46 (6), 1142-1161.

Wang, G., Dou, W., Zhu, W., & Zhou, N. 2015. The effects of firm capabilities on external collaboration and performance: The moderating role of market turbulence. Journal of Business Research, 68 (9), 1928-1936.

Wooldridge, J. M., 2010. Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT Press.

World Bank, 2012. China – Enterprise Survey 2012. [available at: https://www.enterprisesurveys.org/Portal/].

World Bank, 2009. Enterprise survey and indicator surveys: Sampling methodology [available at: www.enterprisesurveys.org].

Wu, W., 2010. Managing and incentivizing research commercialization in Chinese Universities. Journal of Technology Transfer 35 (2), 203-224.

Wu, W., 2007. Cultivating Research Universities and Industrial Linkages in China: The Case of Shanghai. World Development 35 (6), 1075-1093.

Xie, Y., Gao, S., Jiang, X., Fey, C. F., 2015. Social Ties and Indigenous Innovation in China's Transition Economy: The Moderating Effects of Learning Intent. Industry and Innovation 22 (2), 79-101.

Xinhua News Agency, 2010. The number of China’s SMEs is more than 99% of total firms in China. [available at: http://finance.people.com.cn/GB/12824562.html (in Chinese), accessed on Sep 16, 2019].

Zahra, S. A., & George, G. 2002. Absorptive capacity: A review, reconceptualization, and extension. Academy of management review, 27 (2), 185-203.

Zhou, J., Wu, R., & Li, J. 2019. More ties the merrier? Different social ties and firm innovation performance. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 36 (2), 445-471.

Acknowledgements