Abstract

Inner worlds and subjectivity are increasingly recognized as key dimensions of sustainability transformations. This paper explores the potential of cross-cultural learning and Indigenous knowledge as deep leverage points—hard to pull but truly transformative—for inner world sustainability transformations. In this exploratory study we propose a theoretical model of the inner transformation–sustainability nexus based on three distinctive inside-out pathways of transformation. Each pathway is activated at the inner world of individuals and cascades through the outer levels (individual and collective) of the iceberg model, ultimately resulting in transformations of the individual’s relationship with others, non-humans, or oneself. Our main purpose is to empirically investigate the activation of inner leverage points among graduate students who are alumni of an Indigenous language field school in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Semi-structured interviews designed around three core aspects—(1) human–nature relationships; (2) subjective change; and (3) acknowledgment for Indigenous culture—yielded expressions of becoming aware of new forms of relationships and empirically illustrate the roles of deep leverage points in triggering the three inside-out pathways of our model. A strategic focus on activating inner levers could increase the effectiveness of cross-cultural learning in fostering transformations in relationships with non-humans, oneself and others that may yield sustainability outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The obduracy and intractability of current unsustainable trajectories is turning the attention of sustainability scholarship to inner worlds and subjectivity in search for deeper and more effective leverage points (Fischer et al. 2007; Ives et al. 2019; Manuel-Navarrete and Pelling 2015; Steffen et al. 2015). Following Meadows (1999), the inner world can be conceptualized as a domain of ‘deep leverage points’—levers very hard to pull but expected to yield truly transformative change (Abson et al. 2017; Fischer and Riechers 2019). Instead of relying only on technical innovations and behavioral interventions, working with people’s inner worlds (e.g., emotional patterns, identities, values, beliefs, deep-held assumptions), as well as their mental models, is now seen as key for sustainability transformations (Horcea-Milcu et al. 2019; Manuel-Navarrete et al. 2019; O’Brien 2018; Wamsler et al. 2018; Woiwode et al. 2021).

This paper explores the nexus between inner world changes triggered by cross-cultural learning, and sustainability. Recognizing and supporting plural perspectives, worldviews and knowledge systems is essential for transdisciplinary research on sustainability transformations (Lang et al. 2012; Loorbach et al. 2017). Thus, linking IndigenousFootnote 1 knowledge to sustainability has been increasingly discussed (Gómez-Baggethun et al. 2013; Johnson et al. 2016; Tengö et al. 2014, 2017). However, Lam et al. (2020) showed that even though Indigenous knowledge is often used to confirm and complement Western scientific knowledge in the context of biodiversity, climate, and social–ecological change, sustainability transformation research is rarely conducted from the perspective of Indigenous cultures and local knowledge systems. Cross-cultural learning can be generally defined as a process through which a person interacts with multiple cultures (Yamazaki and Kayes 2004). Arguably, the responsibility of Western culture and techno-scientific knowledge systems in causing global environmental change suggests that cross-cultural learning through immersion in Indigenous cultures might be a powerful lever for sustainability transformations (Manuel-Navarrete et al. 2004; Chilisa 2017). This paper sets out to investigate whether and how immersive experiences in Indigenous cultures may trigger inner changes amongst American students through altering their relationships with themselves, others, and non-humans.

Indigenous knowledges are based on worldviews or cosmologies described as ‘holistic and cyclical or repetitive, generalist, process-oriented, and firmly grounded in a particular place’ (Little Bear 2000, p. 83). Furthermore, a relational ontology has been identified as central to many Indigenous cultures and mental models (Alonso González and Vázquez 2015; Hart 2010; Lloyd et al. 2012; Nelson 2018; Reddekop 2014; Wilson 2001). Relational values and ontology eschew modernity’s instrumental values, essentialism and dualistic ontology (Chan et al. 2016). This relationality does not abstract knowing from the life process. Knowing and living, nature and culture, individual and community, humans and non-humans, the inner worlds of human subjects and their exterior conditions of existence are all mutually constituted (Ingold 2002). Escobar (2011) emphasizes the importance of relational ontologies as means for a new notion of sustainability that excels the contemporary “business as usual understanding of sustainable development” and to achieve what he calls a pluriverse—“a world where many worlds fit” (ibid., p. 139). With the discontinuities between mind and body, or humans and non-humans as central features of Western culture and as root cause for present sustainability issues he even states: “We need to stop burdening the Earth with the dualisms of the past centuries, and acknowledge the radical interrelatedness, openness, and plurality that inhabit it” (ibid., p. 139). From this perspective, Indigenous knowledges and cultures’ relational wisdom can assist Western knowledges to link outer and inner dimensions in sustainability transformations.

This paper proposes a theoretical model of how inner and outer leverage points can be seen as connected along inside-out pathways in sustainability transformations. Through interviews with alumni of a Quichua language field school, we apply the model within the scope of an exploratory study to empirically investigate the activation, through cross-cultural learning, of inner world levers of transformation on individual learners (Wamsler et al. 2020). We refer to these shifts in the domain of emotional patterns, identities, values, beliefs, deep-held assumptions, spirituality—deep leverage points—as inner world transformations. These may yield outer changes as individual learners return to their habitual cultural settings with a changed perspective of their relationships, and an acquired “transcultural attitude” (Nicolescu 2010, p. 28). However, this possibility of larger outer transformations is beyond the scope of our study. The paper’s empirical contribution focuses instead on the initial activation of inner levers on individuals exposed to cross-cultural experiences. Even though current unsustainable trajectories were initiated and are largely maintained by Western cultures (by its mental models and institutions), direct interventions to change a culture are problematic and hard to conceive in terms of policy. For this reason, it is key to examine whether cultural changes could be indirectly activated at the deeper level of individuals’ inner worlds. Cross-cultural learning involving Indigenous cosmologies might be a leverage point for such activation if it causes inner changes in Westerners’ perceptions and enactments of their relationships with themselves, others, non-humans and the planet.

We collected and analyzed self-reported cross-cultural experiences of seven alumni from the Andes and Amazon Field School, a boundary organization between Quichua and Western cultures that offers cross-cultural learning experiences to, mostly, graduate and undergraduate students from North American universities (Buzinde et al. 2020). The field school is located in the Ecuadorian Amazon within a Quichua community, where study abroad, and Indigenous language students spent 2 weeks or more, depending on the program. Key to the cultural immersion experience is sharing living spaces with a group of Indigenous instructors who are experts on (or experiencers of) the forest, storytellers and artists. This allows students to experience Indigenous culture more or less in situ. Some students continue enrolling over the years, developing stable relationships with the field school. Our findings focused on evidence of self-perceived changes of the alumni’s relationships with oneself, others, and non-humans as a result, or at least through the influence, of cross-cultural learning. Our discussion links these findings back to our theoretical model to bring more clarity on whether and how cross-cultural learning could be a deep leverage point to activate inner worlds changes, which in turn could cascade into inside-out pathways of sustainability transformation (O’Brien 2013).

Cross-cultural learning as deep leverage point

Meadows (1999, p. 1) defined leverage points as “points of power”, and “places within a complex system […] where a small shift in one thing can produce big changes in everything”. She proposed a systems approach, and 12 nested leverage points, similar to Senge’s (1990) iceberg model of 4 levels of change in organizations. The basic premise for both Meadows and Senge was that collective cognitive processes (mental models, mindsets or paradigms) are deeper or more transformative leverage points than material, organizational, and outer (observable) systems processes. Paradigms and mindsets are shared cognitive structures, and sets of deep (unstated) beliefs, about how the world works that guide outward collective behavior, and are at the root of observable events. Meadows (1999, p. 19) considered the “power to transcend paradigms”, or the “space of mastery over paradigms”, as the ultimate leverage point, thus opening up the Pandora’s box of seeing individual inner worlds as the most powerful lever. By infusing a trans-cultural attitude, cross-cultural learning can be seen as a leverage point at the twelfth level; capable of activating the power to transcend one’s own mental models and culture.

Based on Meadows’ idea that deep levers are more powerful than shallow levers we represent transformational pathways from the lowest (mental models) to the highest point (events) in a hierarchical manner. That is, highlighting inside-out and downplaying outside-inwards change. This is generally consistent with the basic assumption of the iceberg model, as explained below. While exterior circumstances can be important factors of inner change, our model assumes that the most transformational changes are generally triggered by how each person experiences these circumstances and what inner effects such experiencing end up having (cf. Ives et al. 2019; O’Brien 2018). Furthermore, we recognize Wilber’s (2005) Integral Theory as complementary to the iceberg model, but focused on comprehensibly mapping the full complexity of any phenomena, rather than on explaining and articulating the dynamics of transformative change in the context of what it has been recently named as the inner transformation–sustainability nexus (Woiwode et al. 2021).

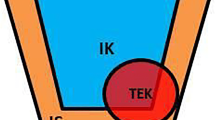

The iceberg model is used in systems thinking to illustrate that observable events (tip of the iceberg) are caused by a greater, non-observable mass of processes and structures. Consequently, trying to modify observable events tends to be self-defeating unless one can leverage changes at deeper causal mechanisms. The most conventional partition of the iceberg includes four nested levels of thinking, often represented as a pyramid. At the very top lies the level at which we observe the symptoms and think in terms of events. It represents the shallowest yet most visible reality of the system (e.g., individual shopping choices; cf. WWF 2016, p. 90). Right below, the level of patterns represents our ability to connect events (or data points) through mathematical models, or, more generally, narratives (Nguyen and Bosch 2013). From recognizing and observing patterns, future events can be extrapolated (e.g., analyzing and predicting shopping choices of groups; cf. WWF 2016, p. 90). Going deeper reveals the third level—systemic structures. These structures reveal regularities in the ways patterns and elements in the system manifest, behave and interact. Thus, glimpsing at the intricate relationships of complex systems (e.g., consumerism or prevailing GDP-focused economic model; cf. WWF 2016, p. 91). However, mental models lie even deeper and, therefore, constitute the most hidden level in this 4-levels pyramid (e.g., notion of ‘we need to get richer to be happier’ WWF 2016, p. 91). We argue that people’s emotional patterns, identities, values, beliefs, deep-held assumptions—their inner worlds—constitute the individual basis of collective mental models (Manuel-Navarrete 2015). Thus, inspired by Meadow’s twelfth leverage point—space of mastery over paradigms—we added inner worlds as a fifth level to the iceberg model (Fig. 1).

(adapted from Nguyen and Bosch 2013)

Five-level iceberg model including inner-worlds

Following Wamsler et al. (2018) call for acknowledging that ‘the micro and macro are mirrored and interrelated’ we duplicate the four-level pyramid to include both the individual realm (micro), and collective realm (macro) (ibid., p. 153). Mirroring the individuals’ pyramid to the collective realm, we labeled the fifth innermost collective level culture (Fig. 2). Operating at the intersection between the individual and collective innermost realms (i.e., inner worlds and culture), cross-cultural learning constitutes a deep lever that, our model hypothesizes, could trigger at least three possible inside-out pathways towards sustainability transformation. The collective and individual realms are interrelated. On the one hand, individual changes are embedded into, and can trigger, collective change. On the other hand, shared mental models, institutions, patterns of events and collective events condition individual mental models, livelihoods, patterns of behavior and individual actions. This is consistent with Wamsler et al.’s (2020, p. 232) set of four transformative skills across four domains: “personal (how we relate to ourselves); social/ collective (how we relate to others); systems (how we relate to nature and the environment); and the future (how we relate to future generations).” For simplicity, our model excludes the fourth domain of future generations. We argue that understanding the coupling between individual and collective realms is key when one explores sustainability transformations (Manuel-Navarrete 2015). In addition, as both individuals and collectives are embedded in environments, the relation to nature—which we phrased as relation to non-humans—is depicted as emerging from individual–collective dynamics. Our relationships with these three realms: individual, collective, and environmental shape “our ways of being (ontologies), thinking (epistemologies) and acting (ethics)” (Wamsler et al. 2020, p. 232).

The model shows three pathways towards sustainability transformations that can be leveraged by cross-cultural learning. These pathways are activated by inner changes (i.e., significant and enduring changes in the emotional patterns, identities, values, beliefs, and assumptions held by cross-cultural learners), cascading onto changes in one or more of the three realms discussed above. Inner changes would be activated by the physical and cognitive dislocation or translocation of students away from their habitual cultural contexts, and as they experience immersion in a context purposefully designed for cross-cultural exchange.

The first pathway cascades up the individual pyramid (on the right of Fig. 2) as inner world changes translate into changes in individual mental models, livelihoods, patterns of behavior and actions, ultimately resulting in a transformation of individuals’ relationship to themselves. Nested in the first pathway, a second one (emerging from enough individuals changing their relationship to self) runs up the collective pyramid (to the left) starting at the deeper level of culture and shared mental models, and cascading changes in institutions and patterns of events, to end up generating new observable collective events. This second pathway is not comprehensively explored empirically in this paper as it would require evidence of transformations that took place in the students’ local cultures, institutions, and events. Finally, a third pathway is conceptualized as nested in the other two. Both individuals and collectives may change their ways of relating to the environment and give way to sustainability transformations (West et al. 2020). Empirically testing the whole model would require an ambitious research program way beyond the scope of this paper. Instead, we elicited reflections from cross-cultural learners for evidence or insights on whether and how their immersions in Indigenous cultures, in combination with other personal experiences, activated inner world changes that have, or could have, in turn acted as deep leverage points and cascaded across the three pathways towards sustainability transformations represented in the model.

Methods and context

The Andes and Amazon Field School at Iyarina is a boundary organization and infrastructure that bridges Indigenous knowledge holders with university researchers and students. The field school was “founded 20 years ago by an American–Ecuadorian academic raised in the Amazon, and his wife, who is a member of the Quichua Indigenous community where the Field School is physically located” by the River Napo in Ecuador (Buzinde et al. 2020, p. 11). Over the years, strong relationships between the local Quichua community and academic visitors formed. Indigenous and Western experts on Amazonian environment and culture co-teach and co-produce boundary objects,Footnote 2 such as language learning materials and translated video recordings of Indigenous languages, to “acquaint non-Indigenous people with local Indigenous perspectives” (ibid., p. 13). Iyarina as a boundary organization features cultural differences of Western and Indigenous perspectives and enables ontological and epistemological discussions of underlying cultural assumptions. Participants not only get to think across different assumptions, but they also relate to people who experience life through Indigenous assumptions (Buzinde et al. 2020). Iyarina means “to think about the future by remembering the past”,Footnote 3 which to Quichua tradition is stored in the land. Thus, Iyarina refers to an Indigenous way of reflection by contemplating the land.

At the field school, Western graduate students participate, inter alia, in an 8-week Quichua language and culture course. In accordance with data protection regulations we received contact details of 27 graduate students who attended the school at least once within a maximum time span of 10 years prior to the time of the study. From this population seven alumni responded and were willing to participate in the research, reaching a response rate of 25.93%. The gender ratio was 3 men and 4 women. The varied scientific background of the interviewees ranged from linguistic anthropology over continental philosophy to Latin America studies and public health, thus displaying diverse expertise. Interviewees had different experiences during the time period spent in Quichua communities or at the field school, thus reported perceptions and stories were influenced from a diversity of experiences. The interviews were conducted remotely using video conferencing tools and audio recording programs. Interviews were between 40 and 120 min long. Subsequently, the interviews were transcribed using MAXQDA 2018 software and coded using R and the RQDA package (Huang 2018).

We conducted the coding and analysis based on the criteria of qualitative social research (e.g.,Bryman 2001; Mayring 2014), especially in the domain of Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA, Eatough and Smith 2017). The focus was self-reported data obtained from semi-structured interviews (informed by Leech 2002). Interviews started with a grand tour question (see Appendix), as described by Spradley (1979, pp. 86–88), eliciting an overview of the individual experiences at the field school. This provided a starting point for further and direct questioning on certain experiences. To focus on outcomes from cross-cultural learning experience, the semi-structured interview protocol was designed around three core themes: (1) human–nature relationships; (2) subjective change; and (3) acknowledgment for Indigenous culture. Each core theme corresponded, respectively, to the following inside-out pathways in our model: (1) relationship with non-human; (2) relationship with oneself; and (3) relationship with others. Through this design we sought to capture key aspects of the activation of deep leverage points of internal changes in relation to the three inside-out pathways from our model. The interview questions were focused on eliciting rich descriptions of inner relational changes associated, from the interviewee’s perspective, to cross-cultural learning in Indigenous contexts. Even though we did not ask about the external manifestations (e.g., changes in behavior) resulting from these inner relational changes, some participants offered examples of external manifestations to illustrate or confirm the inner relational change. Such examples anecdotally support our theoretical model but were not the focus of our study design.

The first theme, human–nature relationships, captured reports on how the participant experienced the relationships Quichua people have with their environment, the similarities or differences to the participant’s own relationship to nature, and the changes in practice or thinking about the personal relationship of the interviewee to their environment. We expected to find self-reported changes in this personal relationship pointing to the activation of a deep lever in the participant that would undermine dichotomous thinking and deep-rooted assumptions in Western culture about human–nature divisions.

The second theme, subjective change, aimed at any sustainability relevant personal insights, ideas or practices associated with the cross-cultural learning experience. We wanted to give participants room to express the myriad ways in which the cross-cultural learning experience may have affected them deeply. This may include changes in personal behavior that resulted from the experiences abroad, as well as fundamental changes of perception, ways of thinking about themselves, or ways of being in the world, but we tried to focus on aspects connected to what have been described in the sustainability literature as inner world transformations (e.g.,Abson et al. 2017; Hedlund-de Witt et al. 2014; Ives et al. 2019; Meadows 1999).

The third theme, acknowledgment for Indigenous culture, was focused changes in Westerners’ perceptions of other cultures fostered by cross-cultural learning. Biocultural diversity advocates the relevance of diversity in all forms (i.e., biologically as well as culturally, and their interconnection) as crucial for a sustainable future (Maffi 2007). Specific levers for this theme may take the form of being deeply impacted by Quichua cultural elements and sustainability concepts, or raising awareness, recognition and appreciation of diversity in various forms.

Findings

A main finding was that participants expressed transformative outcomes from cross-cultural learning largely in terms of becoming aware of new forms of relationships. Followed by the three core aspects of the interview protocol—human–nature relationship, subjective change, and acknowledgment for Indigenous culture—the interview data provided insights on the activation of the three pathways from the model: (1) relationship with non-human; (2) relationship with oneself; and (3) relationship with others.

Relationship with non-human

This pathway gained traction as non-Indigenous students were exposed to other ways of experiencing close human–nature relationships. Overall, interviewees reported that Quichua or RunaFootnote 4 appear to have a very close relationship to the environment surrounding them. Experiencing the awareness of Runa towards the forest and its inhabiting beings and species was very striking for some interviewees:

I always knew that I knew very little about nature, but I didn't realize how sort of out of touch I was. I mean, they could tell time by whatever is going on around them and pay attention to the sound around them [...]. [I]t gave me a whole new appreciation for ...just....how like sensitive these people are to what’s going on around them ....it's amazing. It made me want to be a lot more aware of like seasonal cycles and ...learn about the wildlife wherever I am.

Witnessing that Runa could tell time by the sounds of the forest demonstrated the close human–nature relationship and reflected the ‘out-of-touchness’ of the non-indigenous student. Thus, inducing the motivation of the interviewee to be more aware about nature and the different species in other settings. Another interviewee described the impact of witnessing close human–nature relations and the subsequent motivation to engage in more outdoor activities as well as the concern for the current state of the environment:

I mean it's been very personally affecting, like the experiences that I had in Ecuador, in the environment there. It really made me realize how separated I am in my sort of US-based life from the environment …or I had been at least. Since I've come back I have changed a lot, so I like go camping and hiking a lot more now than I used to.

So it really did shape how I relate to the environment. It made me a lot more concerned about the environment and environmentalism. I am pretty, like, deeply concerned about that now.

Furthermore, the awareness of Runa towards the forest was witnessed by one interviewee reporting on an incident, where an old Runa woman noticed a missing tree:

And it was like a tree that she had not seen for five years [...] and she just kind of remembered exactly where this tree was, what kind of tree it was, and it just kind of struck whole like how ...very much better at paying attention to their surroundings they [Runa] were.

The interviewee experienced a type of environmental awareness not common to him. In Western, industrialized societies paying close attention to nature and its different species is not frequently expressed.

Some interviewees explicitly stated that the key to a close and aware connection to nature does not lie within the Indigenous culture. For these informants, being aware about nature and developing the trait of what one interviewee called ecological perspective-taking—learning and thinking from or about the point of view of nature—is not inherently bound to Quichua culture. In fact, these interviewees tended to translate the experiences and practices of living close to the land (e.g., farming or hunting) to Western framings—for instance, in terms of human–nature relationships. However, other interviewees highlighted the importance of Indigenous cultural framings, such as language features and story-telling, for cultivating closer relationships with non-human beings. Thus implying a biocultural perspective, where cultural elements, such as language, are key to foster meaningful relationships with non-humans. Arguably, embracing non-Western cultural framings could foster closer environmental connection while de-emphasizing the primacy of human–nature dichotomies.

Interviewees generally described with fascination the knowledge and close relationship Runa have with their environment. Some felt motivated in experiencing nature more often and enhancing the quality of their awareness and sensitivity. Engaging in more outdoor activities was a common change of behavior. Interestingly, one participant reported a change of perception about hunting or farming in general, outside the Indigenous cultural context, as activities that can foster closer human–nature relationships through enhancing one’s ecological perspective-taking capacities.

Relationship with oneself

Beyond changes in perception of human–nature relationships, interviewees expressed subjective changes in their ability to reflect about themselves, including deep-held assumptions about being in the world:

[...] the world can look in a very different way and all of your relationships, your entire interpretation of human experience, the life with emotions, beauty, aesthetics, ethics, all of it is different, depending on your starting point.

Furthermore, language appeared to play a key role in changing relations to self. As discussed by interviewees, learning a language does not only enhance the ability to know the people and culture that are holding the language, but it can also induce transformative processes in the learner through reflection and recognition:

Knowing more about other people, speaking other languages forces you to recognize certain things in general, and I think this is important.

[...] if you want to start thinking across different [philosophical] constellations of possibility, being able to learn [an Indigenous language] would be amazing.

In the last quote the interviewee hints to the notion that different languages provide access to different knowledge systems. Furthermore, the interviewee felt that these closely bound cultural elements (knowledge and language) build on and are reproduced by the internalization of fundamental assumptions. Thus, learning a foreign language and engaging, therefore, in a different knowledge system could reveal and question those assumptions:

There are certain assumptions that we inherit in the west kind of through our very philosophical heritage that it's sort of like been bound up with science as we known it in the kind of modern period because it's sort of merged together.[...] The assumptions in there end up being so fundamental and so what we are used to hearing that they kind of ..we forget that they are even assumptions, to begin with.[...] I think that having exposure to different kinds of ...ways of thinking about, like what are the ethical and normative horizons and human actions in the world, what's a good life,... what is the context in which we are doing things like knowing ...and so. I think there is a lot to be done, a lot of good work that can happen sort of in that imperative between space; between Indigenous ways of thinking and Western ways of thinking, I think there is a lot of provocation […].

Another interviewee raised the point that different cultures tend to emphasize different types of questions:

[...] how do we learn from other people and what can we learn? And for me it's been academic, but it's also been very personal, in terms of.... what is a good life? … And I think this is what Quichua people are continuing to ask each other.

In general, interviewees agreed that reflecting on one's own cultural assumptions can be induced by experiencing foreign cultures and ways of thinking about the world. Assumptions that might have been hidden can be revealed through exchanges across cultural contexts.

Even though the cross-cultural learning was in a Quichua context, interviewees were aware about the overall situation of Indigenous people in North America. As felt by the interviewees, Indigenous languages could hold a special perception about the world and the land that they are so closely related to so that learning the language can reveal philosophical and cultural assumptions to people living in those lands. As one interviewee put it:

[...] it's about the local relationships, in some sense it is the language of a place. I think it would be really enriching, especially here is where I am from, I'm born here.

The interviewee was mentioning how he would like to learn the Indigenous language of his home area. Another interviewee reported generally the beneficial impacts of engaging with a foreign culture on personal growth:

I think that you, the things you do, whenever you expose yourself to a different culture or just a different community, you change, or hopefully you change.

I think when you widen your worldview and attempt to understand somebody else and someone else’s point of view, you are a better human.

However, interviewees also mentioned constraints about cross-cultural learning. Learning a language does not necessarily provide access to certain cultural assumptions, cosmologies, or ways of thinking about the world. The motivation of the learner should also be taken into account, as one interviewee described:

You could learn Chinese and of course, the Chinese have an incredible sophisticated philosophy of nature, so you could learn Chinese for that reason or you could learn it in order to make manufactured T-shirts in China.

Furthermore, cross-cultural learning happens through exchanging with people who hold personal values and idiosyncratic ways of engaging, or not, their cultural contexts. As one interviewee described it:

Yeah, I would learn from Indigenous people like we learn from our greatest scientists. Not any Indigenous person. And [...] we would all be better of knowing more about other people.

He considers that a culture consists of heterogeneous people. Everyone has a different history and gained different experiences and insights. Experts about particular cultural elements may hold some sort of wisdom, but not everyone is capable of, and in the position to, transfer knowledge, cultural or personal, as the interviewee concluded.

Drawing on our interviews, two leverage points impelling change along the relationship with oneself pathway became noticeable. First, the importance of being exposed to Indigenous language as tool for reflecting on one’s own culture. Language was described not only as means for communication, but as a tool to build relationships with the land as well as recognizing one’s own hidden cultural assumptions. Second, the questioning of existential beliefs (e.g., what is a good life?) through engaging in conversations and sharing experiences with speakers of Indigenous languages.

However, some constraints of the reflective properties of language learning were also revealed by the interviewees. First of all, the intentions set out by the language learner are crucial. Second, not any speaker can adequately teach an Indigenous language in ways that lead to self-reflection. Third, the need for appropriate translators and cultural facilitators.

Relationship with others

Cross-cultural learning might break stereotypes about the other, as some interviewees indicated. For example, Indigenous people are often seen as the guardians of nature.Footnote 5 However, the fact that people and cultures change and adapt is often overlooked. One interviewee described the complexity of human–nature relationships after witnessing that some Runa use poison to get rid of leaf cutter ants, which contradicted her initial view of Indigenous people being guardians of nature:

So that was something that I did not expect and based on broader discourse about Indigenous people being the guardians, you know like ...people are also rural agriculturalists and make decisions based on convenience and ...what's ...reasonable in their lives. So that's one level where things are complicated.

She also stated that “these are things that have come in really recently” pointing to the effects of globalization on the Indigenous community. One might argue that globalization affects Indigenous communities in a way to become more Western and essentially giving up their bioculture. However, this notion can be challenged, as one interviewee concluded:

[...] there is a lot of literature about Quichua people being like [...] assimilating [...]. So even within all of these ideas `oh Quichua people are really assimilated [...]', I'd really question that sort of approach to thinking about them. I think they are continuing to create and define what their culture and life ways are […].

Thus, the interviewee recognized that assumptions about culture and people might be based on simplified images. One interviewee reported how the abovementioned recognition of cultural assumptions through directly engaging with Indigenous thinking affected the student’s perception of interpersonal relationships:

I think about that in terms of my own life, my own interpersonal relationships,... but I think it is also ...I think once you get used to thinking about the world and not the land and so, in terms of these interrelationships between different species, in the kind of Quichua way of thinking about it, I think it does make sort of a lot of our assumption kind of stand out […].

The interviewee here reflects from the cross-cultural learning experience expanding the ideas about ‘interrelationships between different species’ away from the Quichua setting into the students own life and own interpersonal relationships. Another interviewee described the potential of learning from cultures that are not entangled in consumerism:

Especially, I feel, like here in the Western world and a lot in the United States where everything is at your fingertips... you don't want to wait for anything. You just want it all and just want to do it now and this and that. And I think that there could be a lot to learn from communities that are kind of not quite ingrained in the Western world of everything here, everything now.

All interviewees expressed cultural diversity as beneficial and positive for relationships. The attack on Indigenous languages through colonization and the ongoing threat by dominant languages (i.e., Spanish or English) in institutions embodied in post-colonial structures (e.g., educational system) was often reported as sad and undesirable. One interviewee described how the negative handling of Indigenous language deprived the modern world from experiencing different perspectives of “human conditions” and philosophies:

Specifically trying to stamp out indigenous languages. I just think that is like the saddest and most kind of pathetic relationship to difference that you can really have. Because I just think that ...anyone of those languages gives you such a fundamentally different way of thinking and exploring ..the human condition, what it is to exist and live and ways of exploring fundamental philosophical problems that we tend to cover over and kind of hide from it a lot of the time, but remain present. Regardless of how technical and bureaucratic …our everyday discourse becomes.

Especially the United States was mentioned as limited to experiencing cultural differences, as one interviewee stated:

The United States is like a country with fiber glass insulation around it. It is extremely bubbled.

Another interviewee reported that:

...progress can't necessarily happen in a bubble. And so, once a community sort of starts to open their doors and maybe broaden ...people who come in and speak, that's going to affect change, even if it's small change.

Thus, indicating that allowing experiences with other cultures can contribute to progress and change. Yet such change would require bursting the bubble. In addition, one interviewee described that learning about Pachamama (at the home university) and Alpamama (in Ecuador)Footnote 6 motivated her to advance cultural exchange between North and South America:

[T]hat really had a big effect on me and ....I think it could be very valuable as I am thinking about my career trajectory something that I would really like to be able to do is to bring people from Napo to be instructors or teachers in some ways in institutions in the US if that's something that they're interest in doing. Because I think that there is a lot to be gained from those sorts of exchanges, on both sides.

How the cross-cultural learning experience has actually impacted the pathway to transform relations with others is hardly determinable within the scope of this research. Interviewees generally expressed acknowledgment of biocultural diversity and recognition of Indigenous culture as factors affecting relationships with others, but it is difficult to establish a direct causality. The possibility to learn from other cultures about alternative ways of thinking and relating to the world was a common theme. However, we can only speculate that the acknowledgment for Indigenous cultures and the capacity to challenge one’s own cultural bubble may lead to pathways of changing interpersonal relations towards sustainability (e.g., de-emphasizing consumerism as a way of momentarily satisfying emotional needs).

Discussion

Our data illustrates within the scope of an exploratory study the three inside-out pathways of our deep leverage points’ model of inner worlds transformation. Interviewees reporting on the close human–nature connection of Quichua people and how this experience has influenced their perspective provides insights on the relationship to non-humans pathway. Reconnecting humans with the natural environment is a common theme in sustainability literature (e.g., Folke et al. 2011, 2021). It has been identified as a deep leverage point (Abson et al. 2017; Woiwode et al. 2021), and discussed as a dimension of inner worlds (e.g., Hedlund-de Witt et al. 2014; Ives et al. 2018). Furthermore, Lumber et al. (2017) showed that activities in direct contact with nature involving emotional engagement and contemplation of meaning are pathways towards nature connectedness. Interviewees eloquently articulated how they were deeply affected by realizing and experiencing the close relationship Runa have with their environment. This supports the idea that cross-cultural learning can activate deep leverage points at the inner worlds level.

The urge expressed by some interviewees to engage more in outdoor activities as a result of becoming aware of their out-of-touchness to nature support the idea of an inside-out pathway in the relation to oneself realm. This is also consistent with Lumber et al. (2017) findings. Engaging in more outdoor activities was a common change of individual actions (relationship to oneself pathway) that is also linked to the relationship to non-human pathway. However, it is not clear to what extent these individual transformations may be connected with larger transformations in the interviewees’ local cultures. The comments of some interviewees about ecological perspective-taking and the concept of nature indicates that some Western culture dichotomies (i.e., culture versus nature) were not really challenged, including beliefs that nature engagement can be free from culture. Interviewees were clearly impressed by indigenous perceptions of the environment as part of their culture, and the social-like character of relationships with non-humans, but further research would be needed to determine whether this shifted their own perceptions towards a more “relational, total-field image” (Naess 1973, p. 95).

Interviewees reported recognition of their own cultural biases and how cross-cultural learning triggered engagement with existential questions. This also supports our inside-out pathways, where inner-world changes leverage transformations of relations to oneself in the individual realm. Direct contact with a different culture triggered self-reflection processes facilitated by the boundary organization (i.e., the field school). As Buzinde et al. (2020) described, the first step to facilitate knowledge co-production in Indigenous communities is “endogenous to the academy and requires cognition of knowledge plurality and reflection on researcher reflexivity (ibid., p. 14).” Relationship with oneself is gaining traction in the domain of mindfulness and sustainability. Thiermann and Sheate (2020) identified six links between mindfulness and sustainability of which three can be compared to our findings: greater connectedness with nature, recognition of intrinsic values and openness to new experiences. Different mindfulness practices have been investigated for inner world sustainability transformations, but the role of cross-cultural learning is rarely considered. Yet, interviewees reported about Runa being mindful and aware about their surroundings. Thus, further investigation about mindfulness in indigenous culture and its implications for cross-cultural learning would constitute a promising research intersection.

Our data provided insights on the links between deep leverage points at the inner world level, and transformations as described by interviewees along the three inside-out pathways (Table 1). Leverage points included: sensitivity towards non-humans, new perspectives, new sense of time, empathy, questioning personal assumptions, language, locality, unveiling stereotypes, bursting one’s own cultural bubble, and consternation caused by realizing degree of separation. Though not exhaustively, they provide insights into possible triggers of inside-out pathways. A strategic focus on these inner levers when designing cross-cultural learning settings and experiences could increase their effectiveness in fostering transformations in relationships to non-humans, oneself and others that may yield sustainability outcomes.

As this is an exploratory study, there are certain caveats. The limited sample size of seven interviews might have implications for bias and the possible omission of relevant topics and issues. We hope that our initial findings will encourage further research on the inner transformation–sustainability nexus by testing our model with more participants. Through iterative research processes involving more data the model could be tested and new insights about this nexus may emerge.

Furthermore, it is important to note that the specific cross-cultural learning experiences at Iyarina were certainly not designed with the goal of achieving transformations towards sustainability, but simply to provide training in indigenous languages and cultural immersion. This can be seen as a limitation for our study, but also highlights the unrealized potential of cross-cultural learning for sustainability transformations, a potential which could be realized through the intentional design of deep leverage points, such as the ones outlined in Table 1. For instance, some interviewees described the experience as “Quichua summer camp” to emphasize the academic setting and the students’ group dynamics of the field school in opposition to the immersive experience of sharing and living with Quichua people. This is due to the institutional structures of Iyarina being an academic field school. Whether an isolated, non-academic, immersed experience would be more fruitful for the inner transformation–sustainability nexus is debatable. Most interviewees mentioned the need for appropriate language facilitators. Learning a language is challenging. Thus, having someone who is able to communicate and understand both worlds is beneficial, as one interviewee stated.

Tod, who ran the school, would bring in native Quichua speakers and we would just kind of have opportunities to either talk to them one-on-one, or Tod would kind of pose questions to them and then we would just listen to their responses and then with Tod talk about kind of how they structured their responses. And the idea was kind of to both listen to how they use the language, but also kind of use that as a way to kind of glimpse or trying to understand how they're thinking about language and their relation to—between language and their culture; how that might be different from what we would expect.

This highlights the importance of effective boundary organizations and boundary persons to enable cross-cultural learning, pointing to the question of what type of boundary facilitation is needed to maximize the leveraging power of cross-cultural learning for inner world sustainability transformations.

Our findings offer insights on the links between language, knowledge, beliefs, and the environment—one of the goals of ongoing work in biocultural diversity (Deutscher 2010; Merçon et al. 2019). Biocultural diversity research emphasizes the recognition of language diversity to access different knowledge systems and the interlinkages for biodiversity conservation (Maffi 2007). Furthermore, scholars have promoted the importance of a pluralistic perspective for sustainability outcomes (e.g., Díaz et al. 2015; Escobar 2011). Transdisciplinary methodologies embody, as Nicolescu (2010, p. 32) has put it “[t]he old principle unity in diversity and diversity from unity […].” Therefore, relationships with other cultures not only benefit biodiversity conversation or access to diverse knowledge systems but can promote reflexivity and transdisciplinarity within research (Manuel-Navarrete et al. 2021). Woiwode (2020, p. 31) argues “that one purpose of education is to accelerate a paradigm shift toward integral humanism by generating planetary consciousness.” He approaches this purpose by engaging Indian philosophy and spiritual values and reports: “[i]nterestingly, this aspect for search of a meaningful and fulfilling life was a notable finding in my research of sustainability transitions of young people in India who switched careers from information technology (IT) expertise to organic farming (ibid., p. 33).” Furthermore, Wolf (2012) described the spiritual understandings of conflict and transformation and argued for a construct that combines rationality and spirituality for more effective water conflict management. Our point is that cross-cultural learning can support the development of transdisciplinarity in the broader domain of sustainability science. The role of spiritual experience, as mentioned above, would constitute a compelling focus for the advancement of this study as it is part of Indigenous culture. However, the field school focuses more on academic experiences than including spirituality, thus insights to the role of spirituality in inner world transformation are lacking in this study.

Along Ives et al. (2019, p. 5) notion that “shifting perspectives is a fundamental skill in enabling personal paradigms and mental models to be transcended” the model and empirical evidence presented in this research furthers the discussion of how to leverage inner world sustainability. Deep awareness of one’s own cultural assumptions is an important aspect of inner worlds that can be affected through cross-cultural learning. Our pathways model provides further details on the individual and collective processes and possibilities of personal transformation brought about by cross-cultural exchange.

Conclusion

Inner worlds and deep leverage points come to the fore as sustainability transformations increase in urgency. Plural perspectives and knowledges are needed to challenge ongoing unsustainable trajectories hold by Western culture and techno-scientific knowledge systems, thus drawing attention to Indigenous cultures and local knowledge systems. However, the potential of exposing Western individuals to Indigenous knowledges as a lever for sustainability transformation is rarely investigated. This paper explores the potential of cross-cultural learning and Indigenous knowledges as deep leverage points for inner world sustainability transformations in the context of boundary organizations.

We propose a theoretical model of inside-out pathways of transformation depicting three distinctive pathways of transformation and how these pathways cascade from the inner world level through the individual and collective mirrored realms of an extended iceberg model, resulting in transformations of the individual’s relationship with others, non-humans, and oneself. Within the scope of an exploratory study, empirical investigation of the model resulted in evidence of a set of deep leverage points that can be connected to the three proposed inside-out pathways. In general, cross-cultural learning resulted in awareness of new forms of relationship. Activation of the relationship with non-humans pathway was expressed by alumni by the urge to engage in more outdoor activities as a result of becoming aware of their out-of-touchness to nature. Furthermore, relationship with oneself was indicated by reflecting and recognizing one’s own culturally rooted assumptions.

Interestingly, mentioned concepts, such as ecological perspective-taking, indicate that some Western culture dichotomies (i.e., culture versus nature) were not really transformed. Yet, the cross-cultural learning experience under investigation was not designed with the goal of achieving transformations towards sustainability. In addition, as the boundary organization is an academic field school, the cross-cultural learning was limited by its academic structure. However, skillful language learning facilitation by this boundary organization suggested the potential of cross-cultural learning for inner world sustainability transformation. Moreover, cross-cultural learning outcomes are aligned with transformational skills, such as shifting perspectives and deep awareness. From the standpoint of application, the identified deep leverage points could inform the design of cross-cultural learning processes specifically oriented towards sustainability transformations. Future research could design and test collaborative research processes involving academics, practitioners, indigenous teachers and experienced culture facilitators to investigate the effectiveness of different cross-cultural learning models in creating deep leverage points and inside-out pathways for inner world sustainability transformation.

Expanding the scope of this research and testing the model with similar boundary organizations and more participants would be beneficial to analyze in greater detail the insights explored here. Furthermore, the amplitude of the immersive properties of the cross-cultural learning experience on the activation of deep leverage points remains of interest. However, reproducing the field school setting is a challenging task. Due to (ongoing) colonialism, building trust between Indigenous and Westerners is challenging (Manuel-Navarrete et al. 2021). The field school in this research builds on decades of personal exchanges and trust-building. The meaningful involvement of indigenous people in transformative cross-cultural experiences is key, but difficult to produce, re-produce or scale.

Following Meadows’ idea that deep leverage points are the most powerful, we focused on the inside-out pathways of our model. For further research, however, it would be interesting to investigate other directions within the model. For example, comparing our approach with Wilber’s (2005) Integral Theory could provide a more relational and complex understanding of the activation of inner world transformations. Further investigations of the model could also focus on outside-inwards pathway (from the top to the pyramid to its bottom) as complementary or synergistic with inside-out transformations.

‘Sustainability’ in this paper relates to a holistic and relational context as inner world transformations are assumed to impact relationships with oneself, others and non-humans. This is consistent with the idea of the inner transformation–sustainability nexus (Woiwode et al. 2021). Future sustainability transformation research could focus on the impacts that alumni of Indigenous cross-cultural learning experience actually have in their own communities as cultural sustainability pioneers, or as Paul H. Ray announced ‘Cultural Creatives’.Footnote 7 Tackling global sustainability challenges could greatly benefit from cultural transformations in the Global North.

Notes

‘Indigenous’ is capitalized because we refer to a group of political and historical communities fighting for self-representation, recognition, and rights. https://www.sapiens.org/language/capitalize-indigenous/ [19.02.2021].

Boundary objects are objects, “which are both plastic enough to adapt to local needs and constraints of the several parties employing them, yet robust enough to maintain a common identity across sites” (Star 1989 in Star and Griesemer 1989, p. 393). Further, they “serve as translators and mediators between different social worlds while embodying the knowledge of the people who create them” (Robinson and Wallington 2012, p. 3).

https://www.andes-fieldschool.org/about [14.07.2020].

‘Runa’ denotes ‘person’ in Quichua and is used by Quichua speakers to refer to people of their cultural group (Nuckolls 2010). Therefore, ‘Runa’ and Quichua people/speakers are used interchangeable in this work.

The interviewee reported that she was introduced to Pachmama through Peruvian Quichua and to Alpamama through Napo (Ecuadorian/Amazon) Quichua, both referring to the Mother Earth.

People who are, among other values, concerned about ecological sustainability, interested in other cultures, give importance to altruism and social conscience. http://culturalcreatives.org/cultural-creatives/ [20.02.2021].

References

Abson DJ, Fischer J, Leventon J, Newig J, Schomerus T, Vilsmaier U, von Wehrden H, Abernethy P, Ives CD, Jager NW, Lang DJ (2017) Leverage points for sustainability transformation. Ambio 46(1):30–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-016-0800-y

Alonso González P, Vázquez AM (2015) An ontological turn in the debate on Buen Vivir—Sumak Kawsay in Ecuador: ideology, knowledge, and the common. Lat Am Caribb Ethn Stud 10(3):315–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/17442222.2015.1056070

Bryman A (2001) Social research methods. Oxford University Press Inc, New York

Buzinde CN, Manuel-Navarrete D, Swanson T (2020) Co-producing sustainable solutions in indigenous communities through scientific tourism. J Sustain Tour 28(9):1255–1271. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1732993

Chan KMA, Balvanera P, Benessaiah K, Chapman M, Díaz S, Gómez-Baggethun E, Gould R, Hannahs N, Jax K, Klain S, Luck GW, Martín-López B, Muraca B, Norton B, Ott K, Pascual U, Satterfield T, Tadaki M, Taggart J, Turner N (2016) Opinion: why protect nature? Rethinking values and the environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113(6):1462. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1525002113

Chilisa B (2017) Decolonising transdisciplinary research approaches: an African perspective for enhancing knowledge integration in sustainability science. Sustain Sci 12(5):813–827

Deutscher G (2010) Through the language glass : how words colour your world. Heinemann, London

Díaz S, Demissew S, Carabias J, Joly C, Lonsdale M, Ash N, Larigauderie A, Adhikari JR, Arico S, Báldi A, Bartuska A, Baste IA, Bilgin A, Brondizio E, Chan KMA, Figueroa VE, Duraiappah A, Fischer M, Hill R, Zlatanova D (2015) The IPBES Conceptual framework—connecting nature and people. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 14:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2014.11.002

Eatough V, Smith JA (2017) Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In: Rogers WS, Willig C (eds) The SAGE handbook of qualitative research in psychology, 2nd edn. SAGE Publications Ltd, London, pp 193–211

Escobar A (2011) Sustainability: design for the pluriverse. Development 54(2):137–140. https://doi.org/10.1057/dev.2011.28

Fischer J, Riechers M (2019) A leverage points perspective on sustainability. People Nat 1(1):115–120. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.13

Fischer J, Manning AD, Steffen W, Rose DB, Daniell K, Felton A, Garnett S, Gilna B, Heinsohn R, Lindenmayer DB, MacDonald B, Mills F, Newell B, Reid J, Robin L, Sherren K, Wade A (2007) Mind the sustainability gap. Trends Ecol Evol 22(12):621–624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2007.08.016

Folke C, Jansson Å, Rockström J, Olsson P, Carpenter SR, Stuart Chapin F, Crépin AS, Daily G, Danell K, Ebbesson J, Elmqvist T, Galaz V, Moberg F, Nilsson M, Österblom H, Ostrom E, Persson Å, Peterson G, Polasky S, Westley F (2011) Reconnecting to the biosphere. Ambio 40(7):719–738. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-011-0184-y

Folke C, Polasky S, Rockström J, Galaz V, Westley F, Lamont M, Scheffer M, Österblom H et al (2021) Our future in the anthropocene biosphere. Ambio 50:834–869. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-021-01544-8

Gómez-Baggethun E, Corbera E, Reyes-García V (2013) Traditional ecological knowledge and global environmental change: research findings an policy implications. Ecol Soc 18(4):72–72. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-06288-180472

Hart M (2010) Indigenous worldviews, knowledge, and research: the development of an indigenous research paradigm. J Indig Soc Dev 1(1):1–16

Hedlund-de Witt A, de Boer J, Boersema JJ (2014) Exploring inner and outer worlds: a quantitative study of worldviews, environmental attitudes, and sustainable lifestyles. J Environ Psychol 37:40–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.11.005

Heinämäki L (2010) The right to be a part of nature : indigenous peoples and the environment. Lapland University Press, Rovaniemi

Hill D (2017) Indigenous peoples are the best guardians of world’s biodiversity. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/andes-to-the-amazon/2017/aug/09/indigenous-peoples-are-the-best-guardians-of-the-worlds-biodiversity

Hood M (2019) Indigenous peoples, ‘guardians of Nature’, under siege. https://phys.org/news/2019-05-indigenous-peoples-guardians-nature-siege.html

Horcea-Milcu AI, Abson DJ, Apetrei CI, Duse IA, Freeth R, Riechers M, Lam DPM, Dorninger C, Lang DJ (2019) Values in transformational sustainability science: four perspectives for change. Sustain Sci 14(5):1425–1437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00656-1

Huang R (2018) RQDA: R-based qualitative data analysis. R package version 0.3–1. http://rqda.r-forge.r-project.org

Ingold T (2002) Culture and the perception of the environment. In: Croll E, Parkin D (eds) Bush base, forest farm: culture, environment, and development. Routledge, New York, pp 51–68

Ives CD, Abson DJ, von Wehrden H, Dorninger C, Klaniecki K, Fischer J (2018) Reconnecting with nature for sustainability. Sustain Sci 13(5):1389–1397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0542-9

Ives CD, Freeth R, Fischer J (2019) Inside-out sustainability: the neglect of inner worlds. Ambio. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-019-01187-w

Johnson JT, Howitt R, Cajete G, Berkes F, Louis RP, Kliskey A (2016) Weaving indigenous and sustainability sciences to diversify our methods. Sustain Sci 11(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-015-0349-x

Lam DPM, Hinz E, Lang DJ, Tengö M, von Wehrden H, Martín-López B (2020) Indigenous and local knowledge in sustainability transformations research: a literature review. Ecol Soc 25(1):3. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-11305-250103

Lang DJ, Wiek A, Bergmann M, Stauffacher M, Martens P, Moll P, Swilling M, Thomas CJ (2012) Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: practice, principles, and challenges. Sustain Sci 7(Suppl 1):25–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-011-0149-x

Leech BL (2002) Asking questions: techniques for semistructured interviews. PS Polit Sci Polit 35(4):665–668

Little Bear L (2000) Jagged worldviews colliding. In: Battiste M (ed) Reclaiming indigenous voice and vision. UBC Press, Vancouver, pp 77–85

Lloyd K, Wright S, Suchet-Pearson S, Burarrwanga L, Country B (2012) Reframing development through collaboration: towards a relational ontology of connection in Bawaka, North East Arnhem Land. Third World Q Spec Iss Dev Perspect Antipodes 33(6):1075–1094. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2012.681496

Loorbach D, Frantzeskaki N, Avelino F (2017) Sustainability transitions research: transforming science and practice for societal change. Annu Rev Environ Resour 42:599–626. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-102014-021340

Lumber R, Richardson M, Sheffield D (2017) Beyond knowing nature: contact, emotion, compassion, meaning, and beauty are pathways to nature connection. PLoS ONE 12(5):1–24. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177186

Maffi L (2007) Biocultural diversity and sustainability. SAGE, London, pp 267–277

Manuel-Navarrete D (2015) Double coupling: modeling subjectivity and asymmetric organization in social-ecological systems. Ecol Soc 20(3):26. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-07720-200326

Manuel-Navarrete D, Pelling M (2015) Subjectivity and the politics of transformation in response to development and environmental change. Glob Environ Chang 35:558–569

Manuel-Navarrete D, Kay JJ, Dolderman D (2004) Ecological integrity discourses: linking ecology with cultural transformation. Hum Ecol Rev 11(3):215–229

Manuel-Navarrete D, Morehart C, Tellman B, Eakin H, Siqueiros-García JM, Aguilar BH (2019) Intentional disruption of path-dependencies in the anthropocene: gray versus green water infrastructure regimes in Mexico City. Mexico. Anthropocene 26:100209

Manuel-Navarrete D, Buzinde CN, Swanson T (2021) Fostering horizontal knowledge co-production with indigenous people by leveraging researchers’ transdisciplinary intentions. Ecol Soc 26(2):22

Mayring P (2014) Qualitative content analysis: theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. Klagenfurt. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173

Meadows DH (1999) Leverage points: places to intervene in a system. Sustainability Institute, Hartland, VT

Merçon J, Vetter S, Tengö M, Cocks M, Balvanera P, Rosell J, Ayala-Orozco B (2019) From local landscapes to international policy: contributions of the biocultural paradigm to global sustainability. Glob Sustain 2:E7. https://doi.org/10.1017/sus.2019.4

Naess A (1973) The shallow and the deep, long-range ecology movement: a summary. Inquiry 16:95–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/00201747308601682

Nelson MK (2018) Back in our tracks—embodying kinship as if the future mattered. In: Nelson MK, Shilling D (eds) Traditional ecological knowledge: learning from indigenous practices for environmental sustainability. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 250–266

Nguyen NC, Bosch OJH (2013) A Systems thinking approach to identify leverage points for sustainability: a case study in the Cat Ba Biosphere Reserve, Vietnam: using systems thinking to identify leverage points for sustainability. Syst Res Behav Sci 30(2):104–115. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.2145

Nicolescu B (2010) Methodology of transdisciplinarity–levels of reality, logic of the included middle and complexity. Transdiscip J Eng Sci 1(1). https://doi.org/10.22545/2010/0009

Nuckolls JB (2010) Lessons from a Quechua strongwoman: ideophony, dialogue, and perspective. University of Arizona Press, Tucson

O’Brien K (2013) The courage to change: Adaptation from the inside-out. In: Moser SC, Boykoff MT (eds) Successful adaptation to climate change: linking science and policy in a rapidly changing world. Routledge, London, pp 306–319

O’Brien K (2018) Is the 1.5°C target possible? Exploring the three spheres of transformation. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 31:153–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2018.04.010

Reddekop J (2014) Thinking across worlds: indigenous thought, relational ontology, and the politics of nature or if only Nietzsche could meet a Yachaj

Robinson CJ, Wallington TJ (2012) Boundary work: engaging knowledge systems in co-management of feral animals on indigenous lands. Ecol Soc 17(2):16. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-04836-170216

Senge P (1990) The fifth discipline: the art and practice of the learning organization. Doubleday/Currency, New York

Spradley JP (1979) The ethnographic interview. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York

Star SL, Griesemer JR (1989) Institutional ecology, ‘Translations’ and boundary objects: amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907-39. Soc Stud Sci 19(3):387–420

Steffen W, Richardson K, Rockstrom J, Cornell SE, Fetzer I, Bennett EM, Biggs R, Carpenter SR, de Vries W, de Wit CA, Folke C, Gerten D, Heinke J, Mace GM, Persson LM, Ramanathan V, Reyers B, Sorlin S (2015) Planetary boundaries: guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 347(6223):1259855–1259855. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1259855

Tengö M, Brondizio ES, Elmqvist T, Malmer P, Spierenburg M (2014) Connecting diverse knowledge systems for enhanced ecosystem governance: The multiple evidence base approach. Ambio 43(5):579–591. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-014-0501-3

Tengö M, Hill R, Malmer P, Raymond CM, Spierenburg M, Danielsen F, Elmqvist T, Folke C (2017) Weaving knowledge systems in IPBES, CBD and beyond—lessons learned for sustainability. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 26–27:17–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2016.12.005

Thiermann UB, Sheate WR (2020) The way forward in mindfulness and sustainability: a critical review and research agenda. J Cogn Enhanc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41465-020-00180-6

Vel C (2014) Respecting the ‘Guardians of Nature:’ Chile’s violations of the Diaguita indigenous peoples’ environmental and human rights and the need to enforce obligations to obtain free, prior, and informed consent. Am Ind Law J 2(2):641–680

Wamsler C, Brossmann J, Hendersson H, Kristjansdottir R, McDonald C, Scarampi P (2018) Mindfulness in sustainability science, practice, and teaching. Sustain Sci 13(1):143–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-017-0428-2

Wamsler C, Schäpke N, Fraude C, Stasiak D, Bruhn T, Lawrence M, Schroeder H, Mundaca L (2020) Enabling new mindsets and transformative skills for negotiating and activating climate action: Lessons from UNFCCC conferences of the parties. Environ Sci Policy 112:227–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2020.06.005

West S, Haider LJ, Stålhammar S, Woroniecki S (2020) A relational turn for sustainability science? Relational thinking, leverage points and transformations. Ecosyst People 16(1):304–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/26395916.2020.1814417

Wilber K (2005) Introduction to integral theory and practice. AQAL J Integr Theory Pract 1(1):38

Wilson S (2001) What is indigenous research methodology? Can J Nativ Educ 25(2):175–179

Woiwode C (2020) Inner transformation for 21st-century futures: the missing dimension in higher education. Environ Sci Policy Sustain Dev 62(4):30–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/00139157.2020.1764299

Woiwode C, Schäpke N, Bina O, Veciana S, Kunze I, Parodi O, Schweizer-Ries P, Wamsler C (2021) Inner transformation to sustainability as a deep leverage point: fostering new avenues for change through dialogue and reflection. Sustain Sci 16:841–858

Wolf AT (2012) Spiritual understandings of conflict and transformation and their contribution to water dialogue. Water Policy 14(S1):73–88. https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2012.010

WWF (2016) Living planet report 2016. Risk and resilience in a new era. WWW International. http://www.deslibris.ca/ID/10066038

Yamazaki Y, Kayes DC (2004) An experiential approach to cross-cultural learning: a review and integration of competencies for successful expatriate adaptation. Acad Manage Learn Educ 3(4):362–379

Acknowledgements

We are very thankful for the feedback from two anonymous reviewers. They helped us to clarify and strengthen our work as well as gave insightful perspectives and guidance. Furthermore, we are deeply grateful to Tod Swanson for putting us in contact with alumni of the field school and foremost to the seven alumni for participating in this research.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Handled by David J. Abson, Leuphana Universitat Luneburg, Germany.

Appendix

Appendix

Interview protocol

Numbers in brackets indicate the relation of the question to the one of the three objectives of the research question:

-

(1)

perspective on human–nature relationships.

-

(2)

sustainable attitudes and behavior.

-

(3)

acknowledgement for biocultural diversity.

-

1.

Could you please introduce yourself, what you studied when you participated in the Quichua language course and why you participated in that course?

-

a.

Have you learned Quichua mainly at the field school?

-

a.

-

2.

Could you describe a typical day within the Quichua community during the language course at Iyarina?

-

3.

[1] Could you describe the relationship between the Quichua people and their environment?

-

4.

[1] Would you say that your relationship to nature has changed through learning an indigenous language and engaging in an indigenous community?

-

a.

Could you describe that change?

-

a.

-

5.

[2] Did you feel that this language course (or learning an indigenous language in general) made you think about things differently than you were used to? Did it give you new perspectives?

-

6.

[2] So I came across this quote:

”Indigenous tribes, such as the Achuar and Kichwa, use their resources in a way that promotes regeneration, and regrowth. They embody community and well-being, and a co-existence with nature. Through living sumak kawsay, communities are able to preserve their unique culture and identity, and care for an environment that they know will provide for generations to come.”

What do you think about this quote and the concept of Sumak Kawsay?

-

a.

Is it beneficial for our transformation towards a more sustainable society?

-

b.

[2] Would you say that indigenous cultures or practices in general (other than Sumak Kawsay) can influence our societies towards a more sustainable trajectory?

-

a.

-

7.

[2] Could you describe to me why learning an indigenous language (and engaging with an indigenous culture/philosophy) is important for (Western, sustainability) science (or societies)?

-

8.

[3] Can you elaborate on how you feel about the diminishing of indigenous languages?

-

9.

[3] Would you encourage more people to learn more about indigenous cultures?

-

a.

Why? And how?

-

a.

-

10.

Would you like to share anything with me which hasn’t come up yet?

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gray, K., Manuel-Navarrete, D. Leveraging inner sustainability through cross-cultural learning: evidence from a Quichua field school in Ecuador. Sustain Sci 16, 1459–1473 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-021-00980-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-021-00980-5