Abstract

Evidence emerging from our novel in-prison survey shows that non-criminal legal problems of prison inmates mainly relate to family law matters, contract liability, and administrative procedures. The rate of subjects who face legal issues increases after imprisonment. Employing logit estimation techniques, we test the hypothesis according to which isolation due to imprisonment obstructs legal problem resolution. Results suggest that the open-cell regime has increased the rate of resolution of some family-related problems (divorce and child custody) while not affecting others (legacy issues). Similarly, while common problems with the public administration seem easier to solve under the open-cell regime, those related to contract liability do not. We infer that the open-cell regime may support the resolution of legal problems that usually require standardised approaches. Policy implications supporting the open-cell regime follow.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Prison organisation and life conditions of inmates are relevant for the design of effective policies able to deter crime and recidivism, while favouring prisoners’ rehabilitation and social (re)inclusion.Footnote 1 Although usually associated with some (marginal and questionable) increase in deterrence,Footnote 2 poor prison conditions may represent violations of civil and human rights of the inmates,Footnote 3 and even imply costs outweighing benefits (Hagan & Dinovitzer, 1999). In particular, scholars point towards poor prison conditions being criminogenic, favouring both recidivism (Andersen, 2015; Drago et al. 2011; Mastrobuoni & Terlizzese, 2014; Nillson, 2003), and radicalisation (Mulcahy et al. 2013).

Besides deterrence and incapacitation (Chalfin & McCrary, 2017), imprisonment causes marginality and social exclusion among inmates, ex-inmates, and their families.Footnote 4 Imprisonment in itself, and especially in poor conditions, is a gateway to homelessness (Dyb, 2009); insurgence/deterioration of substance abuse, mental problems, and chronic diseases (Jakobi, 2005); disruption/deterioration of romantic relationships and family connections (Apel, 2016; Christian et al. 2006); and social exclusion of relatives (Besemer & Dennison, 2019; Lee et al., 2016). There is evidence that imprisonment significantly reduces both after-release employment and activity rates and incomes of ex-prisoners (Aaltonen et al., 2017; Bäckman et al., 2018). Furthermore, incarceration seems to be a driver for reinforcing inequalities in the labour market, education, health, families, and even for the intergenerational transmission of inequality (Wakefield & Uggen, 2010). Conversely, the literature on procedural justice suggests that granting a just and decent treatment during imprisonment to the inmates can result in reduced recidivism (Beijersbergen & Dirkzwager, 2016).

In this framework, surprisingly, very little attention has been paid to a specific adverse effect of imprisonment: the reduced—or even nullified—capability of prison inmates to manage their legal needs.Footnote 5

Inmates are in a paradoxical position of being within the (criminal) justice system while experiencing systematic obstacles to access justice for issues other than their criminal case.Footnote 6 Because of restrictions on freedom, they face relevant limitations in their actual legal capability and difficulties in managing their legal needs.Footnote 7 This represents a serious problem of fairness and equity, but also frustrates the rehabilitation purposes of punishment, finally increasing the social costs of imprisonment.Footnote 8

This study is a first attempt to fill this gap. It provides evidence emerging from a survey aimed at mapping both the legal problems and resolution attitude of inmates in two Italian correctional facilities located in Milan: San Vittore and Bollate. The survey was carried out in 2014 within a peer setting operational framework where some selected interviewer-inmates administered the questionnaires to their prison mates. The resulting original dataset collects micro-data from about just under 900 inmates.

We use for the first time this survey dataset to empirically investigate how both institutional/organisational features of the hosting facility and inmates’ individual features affect the likelihood of solving legal problems they had at the moment of incarceration. In particular, we exploit the introduction of the open-cell regime to identify the effects of fewer restrictions in the everyday life in prison on the inmates’ effectiveness in managing and resolving legal issues. According to this regime generally applied in Italy starting from 2014, prisoners are free to move within the prison for a relatively long time during the day, thereby accessing internal infrastructures, undertaking social relations, and—most importantly—accessing prison facilities.

Descriptive statistics suggest that imprisonment in itself represents an obstacle to the access to justice to fundamental rights and citizenship; it also strongly limits the possibility of managing and resolving legal issues that typically emerge in the areas of family law, private law, and administrative procedures. We performed logit regressions to estimate whether the introduction of the open-cell regime is associated with changes in the solution rate of inmates’ existing problems at the time of incarceration. We use backward stepwise techniques to select the most relevant problems faced by the inmates, those that are more easily solved since the introduction of the open-cell system, and the relevant individual characteristics affecting problem resolution. Results suggest that the establishment of the open-cell regime is likely to increase the rate of problem resolution, specifically of issues that require more ‘standardised’ resolution procedures, such as divorce, child custody, and problems with the public administration. However, more complicated and ‘individual-specific’ disputes, such as those related to legacy and contract liability, do not benefit from inmates’ greater freedom. We will discuss relevant policy implications in favour of a wider and more effective implementation of the open-cell regime.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. Section 2 illustrates the questionnaire and its administration and the evidence resulting from statistics. Section 3 presents the methodology and results of the empirical analysis, and Sect. 4 concludes the study.

2 The survey

For the purposes of designing our survey, we started from the literature on access to justice and legal needs of ordinary people. Common people in Europe (CEPEJ, 2014 ; FRA, 2011), the United States (US Dept of Justice, 2013), Canada (CFCJ, 2012), and Australia (AAGD, 2014) typically complain of the lack of prompt, effective, and affordable legal remedies, especially in specific legal areas including family and commercial law; and the adoption of simple and accessible administrative procedures.Footnote 9

Based on this evidence, we developed a multiple-choice questionnaire aimed at mapping the civil/administrative legal needs of inmates, including the following six sectionsFootnote 10:

-

Detention It frames the position of the respondent as a prisoner (judgement phase—i.e. waiting for first judgement, appellant, definitely convicted, duration of conviction, residual duration of imprisonment, recidivism, detention regime, lawyer, etc.).

-

Citizenship and family It frames personal and social features of the respondents (citizenship, gender, age, religion, education, language comprehension, family connections, etc.)

-

Pending non-criminal legal issues that arose before the detention It investigates which kind of pending non-criminal legal problems the inmate had at the moment of incarceration (debts/credits, commercial/private law/tort disputes, family law issues, problems with the public administration, etc.).

-

Resolution of problems that arose before the detention It investigates to what extent and how non-criminal legal problems that were pending before detention were resolved during the detention.

-

Non-criminal legal issues that arose during the detention and their resolution It investigates what kind of non-criminal legal problems the inmate has had during the imprisonment, to what extent, and how these problems have been resolved.

-

Fundamental rights It investigates whether the inmates experienced problems related to the fundamental rights (health, discrimination, and education) and, if this is the case, how they legally proceeded.

In the spring of 2014, all the inmates detained in the correctional facilities of Bollate and San Vittore (except those in the solitary confinement regime) were invited to participate in the survey. Given the high presence of foreigners, we opted to provide the questionnaire in different languages (Italian, Albanian, Arab, Romanian, French, English, and Spanish). The questionnaire was anonymous. Participants in the survey were provided with a brief letter which explained the aims of the survey. Inmates were invited to sign the letter both to confirm that they had understood the objectives of the research and for privacy law compliance purposes. In the letter, the anonymity of the questionnaire was particularly emphasised.

To favour participation in the survey, not only the anonymity of the respondents but also a particular mechanism of questionnaire collection that does not involve any member of the prison staff was guaranteed. To favour the possibility of the inmates to ask for clarifications about the questionnaire without disturbing the aim of avoiding any interference by members of the prison staff, we opted for a peer-setting administration. In particular, two inmates were selected in each prison section to be trained to administer the questionnaire to their mates.Footnote 11

The response rates, although highly variable by section, have been excellent overall: 44.5% for Bollate and 37.1% for San Vittore. Certainly, the individual effort devoted by the interviewer-inmates mattered in determining the response rates; in some sections, the response rate was extremely high, as in the female section of Bollate (76.7%) and in the section of hospitalised prisoners in San Vittore (88%).

From a methodological perspective, this peer-setting approach to administer the questionnaires seems to have been a good choice (moreover, we do not know of any precedent for surveys in prisons). Multivariate analyses allow controlling for multiple interviewers: their different motivations and abilities do not represent a problem for correct data analysis. The interviewer-inmates have also been debriefed to understand both the difficulties they faced during the questionnaire administration and the respondents’ general reaction. Prisoners generally appreciated the aims and methodology of the survey, especially because many of them consider access to justice as a sensitive topic.

The quality of the responses (consistency, sample variance, etc.) and the overall number of observations (893 respondents: 526 from Bollate and 367 from San Vittore) make the resulting dataset a reliable starting point to investigate access-to-justice problems in prison. According to the national statistics,Footnote 12 the number of respondents to our survey corresponds approximately to 1.7% of the total population of inmates in Italy (53,623 prisoners at the end of 2014), and 22.5% of the prison population in Milan (3966 prisoners at the end of 2014). The present study is the first output based on this original dataset.

Table 1 summarises the main institutional features of the two correctional facilities. Table 2 encapsulates both individual and social features of the respondents and information about their detention (for details about prison organisation by sections, see Table 8 in the Appendix).

By comparing the institutional information about Bollate and San Vittore and the questionnaire responses of the inmates, it is clear that these two correctional facilities are very different.

Before looking at the evidence, it must be recalled that Bollate is a relatively new facility, established in 2000 as a prison aimed at hosting prisoners who are definitely convicted (casa di reclusione). Moreover, rehabilitation projects related to long-term imprisonment have been specifically developed in Bollate from its foundation. Conversely, San Vittore is an ancient penitentiary founded in 1879, currently used as a jail where arrested people and defendants are also into custody (casa circondariale).

Despite the institutional differences between the two correctional facilities (prison vs jail), given the problem of overcrowding (in 2014 in Italy, out of every 100 available places in prisons, 105.6 were occupied), arrested people and defendants are often hosted in Bollate while long-term detainees are hosted in San Vittore. This can be easily estimated by comparing the number of inmates in the two facilities at the moment of the survey with the facilities’ accommodation capacity (1184 vs. 976 in Bollate and 988 vs. 753 in San Vittore, as shown in Table 1).

A further organisational difference that this study focuses on concerns the so-called open-cell regime. According to the open-cell regime, inmates (except those under rule 41 bis o.p.) can move in proper common spaces and are involved in individual/social activities during the day while being confined in their cells during the night. Although it was implicitly stated in the Penitentiary Law of 1975 (Law 54/1975), this regime has never been applied. After the European Court of Human Rights ruling on the case of Torreggiani and Others v Italy (application no. 43517/09), all the Italian prisons have been requested to revise their internal organisation to allow all the inmates to move within their section without restrictions, at least for eight hours per day. However, the open-cell regime still remains largely unapplied, though re-launched in 2017 by Law No. 103/2017, partially reforming the penitentiary law. According to Burdese (2018), only 50% of the correctional facilities implemented open-cell regimes (95% in Lombardia, North Italy; 5% in Campania, South Italy). From this perspective, Bollate represents an exception, since the open-cell regime has been implemented in all prison sections since its foundation in 2000. Conversely, in San Vittore, at the time of the survey, the open-cell regime was introduced only in some sections at different dates starting from the beginning of 2014. Therefore, prisoners in the sample benefited from the open-cell regime for a diverse time range.

Concerning the similarities, both the correctional facilities offer various services and activities to the inmates; in particular, there is an office of civil registry and for fiscal matters, a helpdesk for legal assistance, and some network officers who can help inmates to manage issues involving external institutions (e.g. embassies for foreign inmates, etc.). The supply of these services is important since prisoners can find internal support to manage their legal needs, mainly in this form of assistance.Footnote 13 Notably, prisoners who want to find support in these services have to reach the service-desks because, services are not provided cell by cell.

As summarised in Table 2, given the difference between prison (Bollate) and jail (San Vittore), data show that—as expected—Bollate’s population mostly includes Italian people (foreign inmates (32.3%); details by section are provided in Table 8), who are definitely convicted (88.9%), with medium-long penalties (average duration 13.2 years). However, San Vittore hosts a population where the incidence of foreign inmates who are still waiting for a first-instance judgement is substantial (foreigners are 61.7% of the population; 37.3% of the respondents are waiting for a first-instance judgement while 35.1% of the inmates are definitely convicted).

Information about employment before the imprisonment seems to be consistent with the previous features characterising the populations of the two correctional facilities: before being detained, respondents of San Vittore have been either unemployed or occasionally employed more than those of Bollate.

Concerning the number of women and the average age of the inmates, the two prisons have very similar populations. Respondents were also homogeneous in terms of their family situation: about one-third of the respondents were married, more than two-third had children, and about 20% were divorced/separated.

Although the number of foreigners is very different in the two prisons, responses are homogeneous for religion: about 70% are Christians, while 13–14% are Muslims. Generally, respondents from both Bollate and San Vittore understand Italian well or well enough; in both facilities, more than 90% of the respondents had at least primary education and more than one-third had at least higher education.

Although in both the facilities, just under 90% of the respondents are detained according to the ordinary regime, 8.2 and 4.1% of the respondents of Bollate and San Vittore, respectively, are under a work release or semi-custodial regime.

Table 3 shows evidence about civil/administrative legal problems that arose before the imprisonment and were still pending at the moment of the incarceration. In Bollate and San Vittore, 46.1% and 68.8% of the respondents, respectively, had pending legal problems when imprisoned. The most common problems concerned family law matters and issues with public administration (fines/administrative sanctions and tax/duties/contributions). This evidence is consistent with data regarding the counterparties in legal problems faced by them.

Table 4 shows evidence about civil/administrative legal problems that arose during the imprisonment and problems related to the release/renewal of ordinary documents.

Likewise, for problems that arose before the incarceration, respondents who said to have or have had non-criminal legal issues during the imprisonment are significantly more copious at San Vittore than at Bollate (74.9 vs. 52.7%). However, it is worth noticing that being imprisoned seems to lead to augmented non-criminal legal needs. In both the correctional facilities, the number of respondents who report legal problems that arose during the imprisonment increased by more than 6% compared to the respondents reporting problems before the imprisonment.

Concerning the types of problems, the most common ones are related to family law matters, but property law and administrative law issues including evictions, repossessions and loss of subsidies, and family support grants are reported as very frequent.

Only a few respondents declare that they have been able to resolve their problems. The two correctional facilities have similar rates of inmates who gave up trying to resolve their legal issues because they were imprisoned (about 11%). As already discussed, inmates mainly turn to their criminal lawyer and relatives to manage their legal issues; Bollate’s inmates also declared that they ask their mates for help.

During the imprisonment, more than 60% of the respondents have experienced problems related to the release or renewal of ordinary documents (mainly driving license and identity card). It is worth noticing that services that are provided within the correctional facility seem to have some role in the resolution of the issues related to the release/renewal of documents. To resolve problems related to administrative documents, more than 25% of the respondents of Bollate turned to the prison staff and 12% of the respondents of San Vittore turned to volunteers who cooperated with the prison.

Table 5 summarises the evidence about problems related to access to health care, discrimination, and access to education. For the most part, except in the case of access to education, respondents did not experience severe problems. Nonetheless, a relevant number of respondents have (seldom or often) faced problems related to health, discrimination, and/or education. Most prisoners who have had problems did not legally proceed. The number of respondents who successfully proceeded was very limited.

In this regard, data suggest a hypothesis that is further investigated in the next section. Specifically, we will examine whether the open-cell regime, by removing strict limitations to the possibility for inmates to move within their sections, has facilitated the inmates’ legal problem resolution. The hypothesis is also related to the differences between Bollate and San Vittore. In particular, San Vittore started implementing the open-cell regime only partially and very recently, while in Bollate, its application started long time back and has been widespread (as shown in Table 1).

All these factors play a role in explaining a different capacity/attitude to manage the legal needs of prisoners in the two correctional facilities. For instance, statistics suggest that Bollate is more effective in supporting inmates for the release/renewal of documents. This might be explained by the fact that prisoners can move within the prison with less restriction than in San Vittore. Mobility might simply result in a more effective use of services by inmates.

3 Empirical analysis

This section investigates whether measures aimed at guaranteeing more freedom to the prisoners inside the facility can ease the solution of legal problems they had at the time of incarceration.

Ceteris paribus, prisoners who are confined in cell for the largest part of the day have reduced capabilities in managing their legal needs. On the one hand, they have reduced access to soft and hard legal information. On the other hand, they feel discouraged with respect to any proactive attitude. Furthermore, some categories of inmates are likely to be particularly exposed to difficulties in solving their legal problems. For instance, young and less educated individuals without previous experience of imprisonment may experience greater obstacles to problem solution. The same may hold for foreign inmates, because they either have poorer networks or suffer limited knowledge of customary and formal rules. Additionally, inmates who are in pre-trial detention live the extremely paradoxical situation of being excluded from many prison routines (since they are assumed to be innocent); moreover, for investigative purposes, they are subject to special rules often strongly limiting contacts with people outside.

A greater freedom of interaction such as that provided under the open-cell system is manifested not only through increasing contacts with and access to recreational and cultural areas inside the prison, but also through easier access to assistance facilities such as the legal help desk. Allowing inmates to access these internal infrastructures may help them address legal needs, and generate positive externalities among prisoners. Indeed, the discussion of common problems and strategies adopted to solve them could further facilitate their solution. Finally, motivational effects related to a greater sense of empowerment could also contribute to speeding up the solution process.

To identify the effects of reduced confinement on problem resolution capability, we focus on the introduction of the open-cell regime. We rely on the exogeneity of this event with respect to the type of problems faced by the inmates before entering prison/jail. The exogeneity assumption is based on the fact that both the problem that existed at the time of entry into prison and the cause that generated it occurred at a time preceding the entry, and can be considered independent of the introduction of the open-cell regime.

In particular, the identification of the open-cell regime’s effects is supported by specific institutional limitations. First, an inmate cannot substantially interfere with the rules and procedures governing their placement in a given section of the prison. Generally, a prisoner is assigned to a section because of their gender and age irrespective of the committed crime, with the exception of prisoners under protection. Second, assignments are very often determined by problems of section-capacity: even if an assignment is not completely random, it is weakly related to the type of offence. Thus, finally, we can exclude the possibility that a prisoner can significantly and systematically control where they will be assigned.

The same can be said, even to a lesser extent, about facility selection. Bollate is a prison hosting prisoners for prolonged periods of time, while San Vittore is a jail. Hence, being associated with one or the other facility much depends on judicial aspects, and for the inmates not being in pre-trial detention, upon the capacity and availability of places in each facility. We will account for any possible exception to these general principles, introducing appropriate jail and section fixed effects in the regression analysis.

Furthermore, it is important to recall that prisoners in the sample benefited from the open-cell regime for a diverse time range (but still independently from each type of crime committed by the individual inmate), as the regime has been introduced at the section-level at different dates. If, on the one hand, this heterogeneity may be important for identification purposes, on the other hand, it may involve complications in defining the variable aimed at capturing the introduction of open cells. We opted to use a continuous permanence variable under the open-cell regime, instead of a pre-post dummy. An advantage of choosing the continuous variable is that it allows a finer measurement of the extent of the open-cell benefits, because the longer the period of freedom, the more the time available to solve problems.

3.1 Data and methodology

We use a database drawn from the survey illustrated in the previous section. In particular, we are concerned about pending legal problems that prisoners had at the time of their entry into prison.Footnote 14 All observations included in the database refer to prisoners who claimed to have had at least one problem, whereas we discarded all those who declared to have no problems at the moment of their incarceration.Footnote 15 After removing another few observations that presented more than 50% of missing answers among the covariates, a total of 443 observations were used. Summary statistics and descriptions of personal characteristics of the inmates and the problems faced by them are reported in Table 6.

We estimate how the introduction of the open-cell regime allowed a more efficient solution to the inmates’ legal problems. Most relevantly, to inflect the effects of the introduction of the open-cell regime with respect to each specific type of problem (or related counterpart), we introduce interaction terms between the length of detention under the open-cell regime and the nature of each problem or counterpart.

We define \({y}_{ij}\) as a binary variable taking the value 1 if the inmate i facing at least one (type j) problem was able to solve (or the inmate is some way dealing with) it, whereas \({y}_{ij}\) is zero if the prisoner did not solve the problem or had ceased to deal with it.

We specify our model as follows:

where \({x}_{1i}\) is an individual-based predictor of the likelihood of solving problems (namely, the length of the open-cell regime, different for each inmate according to both the time of entrance in prison and the introduction of the open-cell system in each section of their facilities), \({\mathbf{x}}_{2j}\) is a vector of binary variables reflecting the type of problem (or counterpart) faced (common to groups of inmates), while other individual characteristics of the inmate are captured by the covariates (\({\mathbf{x}}_{3i}\)). In particular, besides standard personal characteristics such as age, gender, and education, we have selected as covariates those features that can make legal problem resolution particularly tough, such as waiting for a first-instance judgement, being a foreigner, owning a house, or having children (see Table 6).Footnote 16 Besides covariates, we have added section and survey interviewer’s fixed effects (\({\mu }_{sect}\) and \({\mu }_{int}\), respectively). We have also included a dummy if the inmates are hosted in Bollate (\({\mu }_{jail})\).

The betas are parameters (vectors of parameters if bold letters) to be estimated. We focus particularly on (i) \({\beta }_{1},\) which is a general effect of open cells on problem solution; (ii) \({{\varvec{\upbeta}}}_{2},\) measuring the frequency of each specific problem for the overall population of inmates; (iii) \({{\varvec{\upbeta}}}_{3}\), which is the interaction term between the length of the open-cell regime and each type of problem/counterpart, measuring the effect of the open-cell regime on the likelihood of solving each specific type of problem. Given that we chose ‘other problems’ as the baseline category within the problem taxonomy illustrated in the previous section, \({{\varvec{\upbeta}}}_{2}\) and \({{\varvec{\upbeta}}}_{3}\), respectively, capture the frequency gap in terms of likelihood of solution of each type of problem as a consequence of the open-cell event, compared to the more general category of other problems.

Finally, \({\varepsilon }_{ij}\) is a zero-mean random error term. Standard errors are clustered at the problem level. Clustering is motivated by the fact that, due to common unobserved effects, the willingness and ability to solve or take care of legal needs may in part be common to prisoners facing the same needs.

3.2 Results

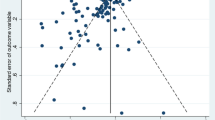

Estimates are performed using a logit model. Results of the empirical analysis are reported in Table 7. The dependent variable (years open) refers to the duration of the open-cell system which the prisoner has benefited from (measured in years). Columns differ according to the set of explanatory variables, one set is represented by the inmates’ counterpart (columns 1–5), while the other set refers to the nature of the problem faced by the inmates (columns 6–10). Marginal effects have been reported. A backward-stepwise estimation procedure was used to select the variables that are statistically more significant in affecting the likelihood of problem solution, with a significance threshold for variable retention in the stepwise procedure set at 10% level.Footnote 17

According to the inmate’s counterpart, estimates show that the most frequent problems occur with spouses (spouse), relatives (relative), and the public administration (public administration) (all through columns 1–5). Likewise, looking at the nature of the problem, the most relevant issues occur with respect to divorce and child custody (divorce and children, all through columns 6–10), inheritance (legacy, columns 7–10), citizenship (residence, columns 7 and 9), contract liability (contract liability, columns 6 and 9), and bankruptcy (bankruptcy, column 7).

From the interaction terms between the length of the open-cell system and the counterpart, it emerges that only those problems with the public administration are likely to be more efficiently solved since the introduction of the open-cell regime (years open*public administration, all through columns 1–5). Surprisingly, family-related problems are not solved efficiently, as the stepwise procedure drops the associated interaction term (years open* spouse) from the set of significant regressors in columns 1–5.

Nevertheless, further elements emerge from the specific nature of the problem. In columns 6–10, there is substantial heterogeneity in the intensity with which the open-cell regime has facilitated the problem solution. First, open cells have a significant positive effect on the solution of problems related to divorce and child custody (years open*divorce and children, all through columns 6–10). Conversely, the negative sign associated with inheritance issues (years open*legacy, columns 7–10) seems to indicate the presence of considerable difficulties in managing issues related to inheritance, compared to the baseline category. This could also explain the lack of significance of the parameters relating to the solution of problems with spouse and relatives in the regressions concerning the counterparties (see above), as easier problem solutions of divorce and child custody are compensated by difficulties in addressing those related to inheritance. Similarly, housing problems seem more easily solved owing to the new regime (years open* house, all through columns 6–10), whereas those involving contract liability face greater obstacles (years open* contract liability, columns 6 and 9).

In general (years open), the open-cell regime has weak significant effects on problem solution. This is perhaps due to the fact that the problem-specific regressors tend to absorb all the significant effects of open cells. Similarly, the inclusion of section fixed effects, even if not significant, may somehow be responsible for the lack of significance of the dummy identifying the type of facility (\({\mu }_{jail}\)). Interviewer’s fixed effects are sometimes significant whereas section fixed effects are not.Footnote 18 This supports our assumption regarding the exogenous assignment of inmates to sections.

Other interesting insights come from the covariates. First, relatively young inmates between the ages of 25 and 34 tend to suffer from greater difficulties in addressing legal problems, perhaps because of the higher frequency of dealing with divorce and child custody matters (age_25_34). This also holds for prisoners who have not had previous experience of detention (First time in jail), which is likely to support the fact that a long detention tends to increase the chances of learning how to solve problems. Wealthier conditions, by owning a house (House ownership) or having a lawyer (Own lawyer), as opposed to receiving legal patronage or obtaining a public defendant, provide more opportunities to solve previous legal problems. Finally, as expected, there is significant evidence that knowing the Italian language (Italian native / speaks good Italian) facilitates problem resolution.

4 Conclusions

Evidence from the survey carried out in the correctional facilities of Bollate and San Vittore shows that most prisoners had pending non-criminal legal problems at the moment of imprisonment. Moreover, imprisonment results in an augmented number of inmates who face legal issues which are not directly related to their criminal story.

Inmates’ legal issues mainly concern family law matters, contract liability, and administrative procedures. Often, the legal needs of prisoners involve ordinary activities such as citizenship and the release or renewal of standard documents. Imprisonment in itself represents a recurrent cause to face difficulties in solving legal problems and/or in giving up trying to solve them. Rarely, inmates find institutional support to their legal needs within the correctional facility. Prisoners turn to relatives and their criminal lawyers to manage pending issues: it is plausible that people who cannot count on their family network and/or on a personal lawyer suffer from a reduced capability to manage their legal problems.

Prison services to support inmates’ legal needs seem to be significantly used only for document release and renewal. Although both the facilities provide offices of civil registry and fiscal matters and legal assistance help-desks, it is unquestionable that access to these services is closely related to the freedom of access to the internal structures of the correctional facility. We tested this hypothesis by exploiting the regime change (introduction of the open-cell system) which occurred at different dates in each of the two facilities. Assuming that (and motivating why) the introduction of this new regime was exogenous with respect to the reasons for which the prisoner was imprisoned, we estimated the effect of the increase in freedom of movement and use of facilities within the prison on the ability to resolve previous legal problems compared to the time of imprisonment.

The empirical analysis provides evidence in favour of the fact that the open-cell regime has increased the rate of resolution of (or willingness to solve) civil and administrative problems, especially those related to family issues. We infer that issues requiring more ‘standardised’ solution procedures, like divorce, child custody, and problems with the public administration, can be more easily addressed through better access to the help-desk services, while inmates face more difficulties to address more complicated and ‘individual-based’ matters (i.e. legacy) and business-related problems (i.e. contract liability). There are no clear-cut results related to the fact of having the status of a prisoner waiting for the first-instance trial. Finally, the regression outcome also supports the idea that foreign inmates and relatively younger and less wealthy inmates have a smaller rate of problem resolution.

As a general policy issue, the empirical results of this study support the idea that the open-cell regime might be a good practice to help prisoners maintain their legal capability while reducing their exposure to further legal problems that can exacerbate (future) social exclusion and difficulties in their reintegration among free citizens.

Finally, notice that the empirical model used to provide this evidence represents a way to interpret the data from the survey, while providing some robust correlations. This has been done in a very straightforward form, using logit estimates with fixed effects and interacting terms. However, we recognize that defining such relationships causally is outside the scope of our article and may be an interesting element for future research.

Notes

See the extensive review of the law and economics literature provided by Avio (1998).

On the boundless law and economics literature on prison, punishment, and crime deterrence, see—among others—Levitt and Miles (2006), Durlauf and Nagin (2011). In their metanalysis, Chalfin and McCrary (2017) verify that the estimated positive impact of harsher punishment on deterrence is relatively small. Furthermore, distinguishing between incapacitation and deterrence is very difficult.

European case-law shows that poor prison conditions represent a relevant theme for protection of fundamental rights. From this perspective, Italy is a kind of shameful leader since the ECHR case of Torreggiani and Others vs Italy (43,517/09 (ECHR, 08 January 2013) stated that poor detention conditions and, in particular, incarceration in overcrowded prisons represent a violation of article 3 of the European Convention of the Human Rights (Maculan et al., 2013). In the United States, thousands of prisoner civil rights cases are filed every year. These cases represent a preponderant part of the civil caseload of federal courts (see Eisenberg 1993, McFarlen 2016).

Although the public opinion pushes back any discussion about potential benefits of alternatives or ‘softer’ detention regimes and ‘open prisons’ where inmates can live almost like common citizens, both scholars and policy makers are aware of the negative effects of prison overcrowding and the loss of individual and social capabilities for inmates related to poor prison conditions (Andersen, 2015; Musa & Ahmad, 2015, and several contributions in Condry & Sharff Smith, 2013).

Typically, prisoners either have a lawyer who looks after their criminal case, or had one before being definitely convicted, are in touch with the surveillance judge or, sometimes, with the public prosecutor or the investigating magistrate, and are also exposed to judicial legal language and procedures.

These obstacles are well illustrated by Grunseit et al. (2008), which is the only access-to-justice survey involving prisoners to our knowledge. However, it has the limit of being based on a very small number of interviews with inmates who are detained in Australian prisons.

Inaccessibility to rights and legal remedies becomes an ancillary penalty that—though not prescribed by the law—increases the afflicting dimension of imprisonment. On the serious consequences of inaccessible legal remedies and ineffective right protection, see Pleasence et al. (2004), Pleasence et al. (2007), Pleasence et al. (2008), and Stratton and Anderson. (2008).

Nonetheless, there are a limited number of bottom-up contributions that explore ordinary legal needs and obstacles to access to justice through investigations directly involving people. Among the survey-based contributions, we number Genn (1999) and Genn and Paterson (2001) for the United Kingdom; AM. BAR ASS’N (1994) and LEGAL SERVS. CORP. (2005) and (2009) for the U.S.; Currie (2006), (2009a), and (2009b) for Canada; and Coumarelos et al. (2006) for Australia.

The questionnaire is available upon request. Before administration, the questionnaire has been checked for coherence and understandability purposes. In particular, volunteers who are used to work with prisoners, rehabilitation staff members from Bollate and San Vittore, and some prisoner-volunteers who are affiliated to the Association Articolo 21 of Bollate have been asked to provide comments and suggestions about the questionnaire. For the prison of Bollate, an additional section about the use of prison services by the inmates has been included. Related evidence is not discussed in the present summary.

Interviewer-inmates have been selected among prisoners who can move within the section without restrictions because performing specific tasks (‘scribes’, librarians, etc.). Before starting the survey, questionnaires filled by interviewer-inmates have been used to identify and correct residual ambiguities (pilot-phase).

Statistics of the Ministry of Justice (Prison Administration). Data for year 2014 (permanently available at http://www.ristretti.it/areestudio/statistiche/. Concerning the prison population, note that although the overall imprisonment rate in Europe has continued to fall starting from 2012 (from 125.6 prisoners per 100,000 inhabitants in 2012 to 102.5 inmates per 100,000 inhabitants in 2018), some countries including Italy, shows an increasing trend from 2014 (+ 7.5% only in the biennium 2016–2018).

On this point, we underline that in 2013/2014 the position of the prisoner as a subject with legal capability has been reinforced, thanks to the introduction of judicial complaints (art. 35 bis, according to the d.l. 146/2013) and remedies (art. 35 ter, according to the d.l. 92/2014) in the Law 54/1975 (Ordinamento Penitenziario). See also Della Bella, 2017.

In the regression analysis, we do not consider the problems that arose during incarceration because this may raise additional independence issues between personal traits of the inmate (possibly correlated to the problem) and internal provisions taken by the prison administration, including confinement.

We also excluded prisoners under confinement from the regressions, without obtaining substantial differences in the estimates.

As already explained above, the fact of being waiting for a first-instance judgment, actually deprives a prisoner of many opportunities to participate to the ‘regular routine’ and benefit from services and opportunities provided by the correctional facility. Foreigners suffer for additional obstacles including knowledge and language deficiencies and the lack of any (family) network outside the prison. Finally, when there are children, families and prisoners are in a position requiring constant negotiation of competing interests. See Hagan and Dinovitzer (1999), Christian et al. (2006), Grunseit et al. (2008).

Robustness check is conducted, both using different significance thresholds and including all covariates (Tables 2a and 3a in the Appendix). In particular, the full set of covariates included the length of the overall stay in prison for each inmate. The rationale for its inclusion is that the length of stay under the open-cell regime could be correlated with the overall time that an inmate spent in prison, thus potentially introducing confounding factors in identifying the effect of the open-cell regime and its interaction with each type of problem/counterpart. Although the stepwise procedure discards this variable as being not significant above 10% level (therefore not reported in Table 7), it is included in Table 3a in Appendix. Besides being not significant, the variable Length of stay in prison does not substantially affect the main outcome.

Full estimation output available upon request.

References

AAGD (2014). Annual Report 2013–2014 - Australian Attorney-General’s Department.

Aaltonen, M., Skardhamar, T., Nilsson, A., Højsgaard Andersen, L., Bäckman, O., Estrada, F., & Danielsson, P. (2017). Comparing employment trajectories before and after first imprisonment in four Nordic countries. British Journal of Criminology, 57, 828–847. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azw026

Andersen, S. H. (2015). Serving time or serving the community? Exploiting a policy reform to assess the causal effects of community service on income, social benefit dependency and recidivism. Journal of Quantitative Criminology., 31, 537–563.

Apel, R. (2016). The effects of jail and prison confinement on cohabitation and marriage. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 665, 103–126.

Bäckman, O., Estrada, F., & Nilsson, A. (2018). Locked up and locked out? The impact of imprisonment on labour market attachment. British Journal of Criminology., 58, 1044–1065.

BarAss, A.M.’N (1994). Legal needs and civil justice: A survey of Americans, major findings from the comprehensive legal needs study. Available at www.abanet.org/legalservices/downloads/sclaid/legalneedstudy.pdf.

Beijersbergen, K. A., & Dirkzwager, A. (2016). Reoffending after release: Does procedural justice during imprisonment matter? Criminal Justice and Behavior, 43, 63–82.

Besemer, K.L., Dennison, S. (2019). Intergenerational social exclusion in prisoners’ families. The Palgrave Handbook of Prison and the Family, 479–501 Springer.

Burdese, C. (2018). Celle chiuse vs celle aperte. Il fallimento plastico dei responsabili, Ristretti orizzonti. 15 aprile.

CEPEJ (2014). CEPEJ report evaluating European judicial systems - 2014 edition (2012 data) - CEPEJ Studies No, 20.

CFCJ (2012). The Cost of Justice. Weighing the Costs of fair and Effective Resolution to Legal Problems. Report of the Canadian Forum on Civil Justice. Available at www.cfcj-fcjc.org/sites/default/files/docs/2012/CURA_background_doc.pdf.

Chalfin, A., & McCrary, J. (2017). Criminal deterrence: A review of the literature. Journal of Economic Literature, 55, 5–48.

Christian, J., Mellow, J., & Thomas, S. (2006). Social and economic implications of family connections to prisoners. Journal of Criminal Justice, 34, 443–452.

Condry, R., & Sharff Smith, P. (Eds.). (2013). Prison, punishment and the family. Oxford University Press.

Corp, L.S.E.R.V.S.(2005). Documenting the justice gap in America: The current unmet civil legal needs of low-income Americans. Available at 2005.www.lsc.gov/sites/default/files/LSC/images/justicegap.pdf.

Corp, L.S.E.R.V.S.(2009). Documenting the justice gap in America: The current unmet civil legal needs of low-income Americans. Available at www.lsc.gov/JusticeGap.pdf, 2009.

Coumarelos, C., Wei, Z., Zhou, A.Z. (2006). Justice made to measure: NSW legal needs survey in disadvantaged areas. Access to Justice and Legal Needs, Volume 3, Law and Justice Foundation of New South Wales, ISSN 1832–2670.

Currie, A. (2006). A national survey of the civil justice problems of low- and moderate-income Canadians: Incidence and patterns. International Journal of the Legal Profession, 13, 217–242.

Currie, A. (2009a). The legal problems of everyday life. In R. L. Sandefur (Ed.), Access to Justice (Sociology of Crime, Law and Deviance, Vol. 12) (pp. 1–41). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1521-6136(2009)0000012005.

Currie, A. (2009b). A lightning rod for discontent: Justiciable problems and attitudes towards the law and the justice system. In A. Buck, P. Pleasence, & N. J. Balmer (Eds.), Reaching further: Innovation, access and quality in legal services (pp. 100–114). The Stationery Office.

Della Bella, A. (2017). Il carcere oggi: tra diritti negati e promesse di rieducazione. Diritto Penale Contemporaneo, 4, 42–50.

Drago, F., Galbiati, R., & Vertova, P. (2011). Prison conditions and recidivism. American Law and Economics Review, 13, 103–130.

Durlauf, S. N., & Nagin, D. S. (2011). Imprisonment and crime: Can both be reduced? Criminology and Public Policy., 10, 13–54.

Dyb, E. (2009). Imprisonment: A major gateway to homelessness. Housing Studies, 24, 809–824.

Eisenberg, H. B. (1993). Rethinking prisoner civil rights cases and the provision of counsel. Southern Illinois University Law Journal, 17, 417.

FRA (2011). Access to justice in Europe: An overview of challenges and opportunities European. Union Agency for Fundamental Rights Publications Office of the European Union.

Genn, H. (1999). Paths to justice: What people think about going to law. Hart Publishing.

Genn, H., & Paterson, A. (2001). Paths to justice Scotland: What people in Scotland do and think about going to law. Hart Publishing.

Grunseit, A., Forell, S., McCarron, E. (2008). Taking justice into custody access to justice and legal needs. Law and Justice Foundation of New Wales, ISBN: 9780909136918.

Hagan, J., & Dinovitzer, R. (1999). Collateral consequences of imprisonment for children, communities, and prisoners. Crime and Justice, 26, 121–162.

Lee, R. D., Fang, X., & Luo, F. (2016). Parental incarceration and social exclusion: Long-term implications for the health and well-being of vulnerable children in the United States. Research on Economic Inequality, 24, 215–234.

Levitt, S. D., & Miles, T. J. (2006). Economic contributions to the understanding of crime. Annual Review of Law and Social Science., 2, 147–164.

Maculan, A., Ronco, D., Vianello, F. (2013). Prison in Europe: Overview and trends. European Prison Observatory. Detention conditions in the European Union. Antigone Edizioni, Roma

Mastrobuoni, G., Terlizzese, D. (2014). ‘Harsh or Human? Detention Conditions and Recidivism,’ EIEF working papers, 1413. Einaudi Institute for Economics and Finance (EIEF).

Mattei, U. (2006). Access to justice, costs, and legal aid. Utrecht, The Netherlands: XVII Congress of the International Academy of Comparative Law.

Mulcahy, E., Merrington, S., & Bell, P. J. (2013). The radicalisation of prison inmates: A review of the literature on recruitment, religion and prisoner vulnerability. Journal of Human Security, 9, 4–14.

Musa, A. A., & Ahmad, A. (2015). Criminal recidivism: A conceptual analysis of social exclusion. J Culture Society and Development, 7, 28–34.

Nillson, A. (2003). Living conditions, social exclusion and recidivism among prison inmates. Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention, 4, 57–83.

Pleasence, P., Balmer, N. J., & Buck, A. (2008). The health cost of civil-law problems: Further evidence of links between civil-law problems and morbidity, and the consequential use of health services. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 5, 351–373.

Pleasence, P., Balmer, N. J., Buck, A., O’Grady, A., & Genn, H. (2004). Civil law problems and morbidity. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 58, 552–557.

Pleasence, P., Balmer, N.J., Buck, A., Smith, M., & Patel, A. (2007). Mounting problems: Further evidence of the social, economic and health consequences of civil justice problems. In P. Pleasence, A. Buck, & N. J. Balmer (Eds.), Transforming lives: Law and social process: Legal Services Commission (pp. 71–96). UK: The Stationery Office.

Stratton, M., Anderson, T. (2008). Social, economic and health problems associated with a lack of access to the courts. Edmonton: Canadian Forum on Civil Justice.

Ulvinen, V. (1998). Prison life and alienation. In D. Kalekin-Fishman (Ed.), Designs for alienation: Exploring diverse realities. University of Jyväskylä.

US Department of Justice (2013). The access to justice initiative of the U.S. Department of Justice. Access to justice accomplishments. Available at www.justice.gov/atj/accomplishments.pdf.

Varano, V., De Luca, A.(2007). Access to justice in Italy, Global Jurist (Advances, art. 6). 7.

Wakefield, S., & Uggen, C. (2010). Incarceration and stratification. Annual Review of Sociology, 36, 387–406.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank two anonymous referees, the Directors Gloria Manzelli and Massimo Parisi, rehabilitation officers Roberto Bezzi and Emanuela Merluzzi, and all the inmates who participated in the survey. We are also grateful to Laura de Carlo, Fiorenzo de Molli, Silvia Landra, Martina Tombari, and Marzia Ravazzini for their suggestions. Finally, we thank Annika Bozzetti, Ilaria Loda, and Mattia Suardi for their excellent research assistance. This research has been developed within the project The Economics of Access to Justice (Grant No. 298470 Marie Curie IntraEuropean Fellowship - 7th European Community Framework Programme at the ACLE, University of Amsterdam) and with the support of Baffi Carefin Centre, Bocconi University and DEMS, University of Milano-Bicocca. All errors are our own.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Pavia within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dalla Pellegrina, L., Saraceno, M. Does the open-cell regime foster inmates’ legal capability? Evidence from two Italian prisons. Eur J Law Econ 52, 89–135 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-021-09701-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-021-09701-w