Abstract

The present study tests if the spatial variability in endogenous and exogenous components of population growth (natural balance and migration balance) reflects the transition from a mono-centric (compact-dense) settlement structure towards a more polycentric agglomeration based on sub-centers. The spatial distribution of population growth rates across municipal units in Barcelona province (Spain) was analyzed over a sufficiently long time period (44 years between 1975 and 2018, partitioned into four intervals of equal length, 1975–1985, 1986–1996, 1997–2007, 2008–2018) at five concentric rings around Barcelona. Natural balance and migration rates were investigated vis à vis selected territorial indicators using descriptive, inferential and multivariate statistical techniques. The contribution of natural balance to overall population growth decreased with the distance from downtown Barcelona; the contribution of migration balance increased with population density. In the first period (1975–1985), natural balance was higher in peri-urban locations and sub-central municipalities. In the following two periods (1986–1996 and 1997–2007), the contribution of natural balance to total population growth decreased, showing a greater spatial concordance with migration rate. In the last period (2008–2018), natural population growth decelerated further, and the impact of migration balance was extremely variable across space. The empirical results of this study shed light on the (apparent or latent) demographic processes underlying Barcelona's long-term growth, and provide evidence in favor of a relationship between polycentric development and the shift from natural growth to immigration as the main engine of urban expansion in recent times.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polycentrism is a common feature of metropolitan systems worldwide (Carbonaro et al., 2016; Fernández-Maldonado et al., 2013; Findlay & Hoy, 2000). This concept has assumed a normative relevance, being often regarded as a pre‐requisite for a more sustainable and balanced development across Europe. It was demonstrated widely how urban development taking place over the past few decades, has progressively moved away from standard mono-centric models towards spatially balanced structures and functionally polycentric agglomerations resulting from processes of residential decentralization (Gilli, 2009; Hank, 2001; Lee & Reher, 2011). This transformation has had a strong impact on settlement structures characterized by subtle dispersion processes (Bocquier & Bree, 2018; Couch et al., 2007; Dijkstra et al., 2015). Long-term analysis of population and settlement distribution provides an informative tool to investigate urban structures and the related functions (Paul & Tonts, 2005; Pérez, 2010; Roca Cladera et al., 2009; Salvati & Serra, 2016; Torrens, 2006).

Since the mid-1990s, polycentrism has been considered a theoretical framework in the analysis of the spatial organization of metropolitan regions and a tool of territorial intervention, assuming a normative relevance in the European Union (Burger & Meijers, 2012). Being regarded as a sort of 'hegemonic' policy goal (Hoekveld, 2015; Kabisch & Haase, 2011; Vasanen, 2012), polycentric urban expansion has been frequently seen as a pre‐requisite for sustainable development, reducing territorial disparities (Salvati et al., 2016). While economic integration of marginal and disadvantaged areas is crucial to assuring greater competitiveness to the European Union (Schneider & Woodcock, 2008), polycentric development was the candidate strategy promoting tighter attention to a spatially balanced regional growth (Neuman, 2005). This target becomes achievable through place-oriented interventions instead of top-down policies decided at European and national levels, ignoring the regional dimension, and with poor participation and awareness on a local scale (Parr, 2004; Longhi & Musolesi, 2007; Salvati et al., 2018). Examples of polycentric regions in Europe include, among others, the Ruhr area in Germany, Ramstad in the Netherlands, Stoke-on-Trent in the United Kingdom, the Po valley in Northern Italy and the most urbanized areas of Belgium (Meijers, 2008). As a result, these regions have no single urban center, but several towns with similar demographic size and a comparable economic power, interconnected by smaller centers embedded in a dense infrastructural network and hosting medium- or high-level functions (Bayona & Gil-Alonso, 2012; Hatz, 2009; Lucy & Phillips, 2000).

While scattered urban structures are associated with negative social, economic and environmental consequences (Muñoz, 2003), polycentrism is widely acknowledged to achieve sustainable development (Muñiz & Garcia-Lopez, 2010; Muñiz et al., 2003, 2008), combining the advantages of agglomeration economies observed in compact cities with the reduced congestion of decentralized spatial forms (Garcia-López & Muñiz, 2010, 2011; Garcia-López, 2012). Assessing the spatial evolution of population growth rates – evaluating separately the contribution of natural balance and migration – over sequential stages of urban development contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of metropolitan transitions (Marshall, 2000; Monclus, 2000; Neuman, 2005).

Spatial and a-spatial approaches have been proposed to evaluate the contribution of both components of population growth in total urban expansion (Helbich, 2012; Kulu, 2013; Schneider & Woodcock, 2008). However, the specific socio-demographic dynamics that characterize the transition toward a truly polycentric development are still under investigated and need clarification based on empirical analysis of local-scale population data (Balbo et al., 2013; Billari & Kohler, 2004; Boyle, 2003; Gavalas et al., 2014). Decomposition of total population growth in two components (endogenous and exogenous growth) allows a better comprehension of long-term demographic dynamics and polycentric development (Buzar et al., 2007; Salvati & Carlucci, 2017; Veneri, 2013).

Mediterranean cities are the most developed and affluent contexts in Southern Europe (Carlucci et al., 2017; Cuadrado-Ciuraneta et al., 2017; Pili et al., 2017). In these cities, a particularly complex interplay of socioeconomic forces influenced population growth at different spatial scales – from local to regional (Duvernoy et al., 2018; Garcia & Riera, 2003; López-Gay, 2014). The contribution of vital dynamics and migration was particularly heterogeneous over space, being oriented along elevation, coastal-inland, and accessibility gradients (Arapoglou & Sayas, 2009). Demographic transition in Southern Europe contributed to accelerated urban change, with a shift from compact-dense settlements to more scattered and discontinuous structures (De Muro et al., 2011; Dura-Guimera, 2003; Paul & Tonts, 2005).

Literature dealing with the long-term development of the Mediterranean cities concentrated on their peculiar morphologies and socioeconomic structures highlighting functional similarities and common transformative processes (Domingo & Gil-Alonso, 2007; Lerch, 2013; Morelli et al., 2014). However, relatively few studies linking new settlement forms with (more or less) rapid socioeconomic changes have been promoted with the aim at identifying evident and persistent characteristics of their recent expansion (Kabisch et al., 2012; Serra et al., 2014; Tsai, 2005). Recent studies pointed out that defining unique trends of urbanization, not only in the Mediterranean basin, but even in Southern Europe, presents some inevitable difficulties because of country- and place-specific determinants that affect the development pattern of each city in a more effective way than the (only supposedly stronger) regional (i.e. Mediterranean-wide) factors (Garcia-Ramon & Albet, 2000; Nel·lo, 2011; Richardson & Chang-Hee, 2004).

While some elements characterizing the majority of Southern European cities still remain valid when contrasting them to the affluent and 'globalized' North-Western urban models (e.g. compact forms and dense settlements in the core city), traditional settlement structures have sometimes hampered the adopted measures aimed at promoting urban competitiveness in the Mediterranean region (Turok & Mykhnenko, 2007). Compact structures derive from a stratification of past development waves, and are usually organized around a core center dominating the towns' hierarchy on a regional scale (Gil-Alonso et al., 2016; Gospodini, 2009; Longhi & Musolesi, 2007).

To ascertain if present development reflects a (more or less) rapid transition towards a polycentric structure presents inherent difficulties and needs further investigation (Roca Cladera et al., 2009; Tsai, 2005; Veneri, 2013). In this regard, a specific focus of this study was devoted to analyze population dynamics in sub-central locations, regarded as the most relevant engine of polycentric development (Blanco, 2009; Champion, 2001; Kroll & Kabisch, 2012). Urban density, spatial forms, economic and social structures (and the rapidity of their changes), allow identification of different expansion modes (Monclus, 2000). By analyzing the evolution of residential sub-centers over a sufficiently long time interval, earlier studies discriminated a sort of ‘hidden polycentrism’ from more subtle scattered paths of urban expansion (Westerink et al., 2013).

According to Roca Cladera et al. (2009), a sub-center was regarded as a location that represents a structural element of urban sub-systems within the metropolitan configuration. This definition resulted as particularly meaningful in the present study, which concentrate on long-term changes in population dynamics at various spatial scales (from regional to local) by assessing formation (and consolidation) of residential sub-centers (Vega & Reynolds-Feighan, 2008). Assuming a specific role of endogenous and exogenous population growth in the sequential phases of sub-central urban expansion, a diachronic and comparative approach seems to be particularly appropriate to identify similarities and differences in the restructuring of urban space (Vobetká & Piguet, 2012). By overcoming the restricted availability of long-time series of employment density or building types on a local scale (Van Nimwegen, 2013), this approach benefits from the extensive use of basic—and thus largely available—demographic data (long-term, homogeneous time series available at the desired territorial scale).

Based on these premises, this paper moves in the debate on polycentric development and population dynamics in growing urban regions. More specifically, our study discusses the theory of urban transition through a long-term vision, integrating a comprehensive analysis of population growth that decomposes its endogenous (natural balance) and exogenous (migration) components with a polycentric vision of metropolitan development (Coleman, 2006; Lesthaeghe, 2010; Lutz & Qiang, 2002). We assume that demographic dynamics are not spatially neutral, being in turn influenced by the dominant urban structure (Kulu & Boyle, 2009). On a metropolitan scale, we hypothesize that the exogenous component of total population growth was determinant in the consolidation of sub-centers that attract short-range and long-range population movements, while being initially supported by a higher rate of natural population growth (Coleman, 2008; López-Gay, 2007; Módenes, 1998).

The relationship between components of population growth (vital transition and migration) and a set of variables delineating selected characteristics of local contexts has been investigated to verify if polycentric development in Barcelona—contrasting the mono-centric structure typical of several Mediterranean cities—has been characterized by peculiar population dynamics (Di Feliciantonio & Salvati, 2015; Di Feliciantonio et al., 2018; Zambon et al., 2017) . To identify scale-dependent demographic processes, the present study was articulated on multiple spatial levels—from regional to urban scales, using administrative boundaries and official statistics (Zambon et al., 2018). Barcelona is one of Spain's oldest cities and has taken centuries to evolve into its present state as a modern metropolis that has substantially benefited from massive infrastructural growth, urban regeneration and renewal, and spatially asymmetric peri-urban development over the past decades (Blanco, 2009; Dura-Guimera, 2003; Módenes, 1998). The Barcelona’s metropolitan region is considered exemplificative of urban transformations from mono-centrism and compactness to polycentrism and metropolitan balance (Dura-Guimera, 2003; Garcia & Riera, 2003; Garcia-Ramon & Albet, 2000). Based on empirical evidence, this study contributes to analysis of long-term metropolitan growth in Barcelona as a polycentric process (Marshall, 2000) using demographic dynamics – instead of more classical indicators of economic agglomeration and scale factors (Salvati, 2016). Studies identifying distinctive population dynamics in central cities, residential sub-centers and peri-urban districts over a long time horizon are relatively scarce in Europe, thus justifying the analysis’ framework adopted here. The implications of this study for urban sustainability are finally discussed, and policy guidelines for cohesive urban growth and spatially balanced regions derived from our study can be extended to other contexts with similar patterns of change in both advanced economies and emerging countries.

Methodology

Study Area

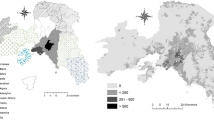

The investigated area encompasses the administrative boundaries of Barcelona’s province (NUTS-3 level of European Statistical Nomenclature for Territorial Units) extending 7,726 km2 of land along the elevation gradient from the Mediterranean Sea to the Pyrenees mountain chain (Fig. 1). This area is partitioned into 311 municipalities (NUTS-5 level of the statistical classification for the administrative boundaries of Europe) and is characterized by undulated topography consisting by nearly 30% lowlands, 50% uplands, and 20% mountains (Paul & Tonts, 2005). Although urban fabric occupies an important portion of the area, the majority of the provincial surface still consists of cropland and forests. Barcelona’s province experienced a rapid population increase in the aftermath of Civil War (Muñoz, 2003) with growth rates approaching (and sometimes overpassing) 2% per year (López Gay, 2014). The economic structure of the region is dominated by advanced services and other activities with high value added. The Barcelona metropolitan region still has an important industrial base focusing on the metallurgical industry and chemical/pharmaceutical sectors.

Distance of each municipality belonging to the study area from the inner city of Barcelona (left) map of sub-centre municipalities* (middle) and population density map (inhabitants / km2) in 2010 (right). *'RMB sub-centres' include the following municipalities: Granollers, Martorell, Matarò, Terrassa, Sabadell, Vilafranca del Penedés, Vilanova i la Geltrù; 'province head towns' include Manresa, Vic and Berga

Resident population in Barcelona's province increased from one million inhabitants in 1900 to 5.5 million inhabitants in 2010 with marked changes in its distribution over core city, sub-centers and peri-urban areas. While at the beginning of the twentieth century more than 50% of province's residents lived in the core city, the population declined to 29% in 2010. Downtown population, however, showed a U-shaped relationship over time, indicating urban concentration during 1900–1950 (from 52 to 57%) and de-concentration afterwards (from 57 to 29%). Population dynamics were comparable in the medium-term (10 years) and the long-term (30 years): sub-centers showed the highest growth compared to both core city and peri-urban municipalities. During 1900–1950, population growth rates were higher in the core city than in peri-urban municipalities while the reverse pattern was observed in the subsequent period (1950–2010), with peri-urban municipalities showing, on average, higher growth rate than the core city (López Gay, 2007).

Density progressively increased in the core city until 1980 (from 5.4 thousand inhabitants/km2 to 17.8 thousand inhabitants/km2), decreasing slowly to 16.4 inhabitants/km2 in 2010, mainly due to the suburbanization of baby-boomers when they arrived at the age of leaving the parental home. The same pattern was observed in sub-central locations with a peak density measured in 1980 and a moderate decline afterwards. The ratio of sub-center to core city density showed a positive trend from 0.15 (1900) to 0.26 (2010) with a peak observed in 1980 (0.43). Although increasing over time, population density in peri-urban municipalities was, on average, remarkably lower than that observed in sub-central locations.

Spatial Analysis’ Unit

Selection of the spatial unit of analysis is a critical challenge for the empirical analysis of population distribution, demographic dynamics, urban density and changes in the settlement structure over time (Morelli et al., 2014). Most of them rely on administrative boundaries, which are arbitrary units of measurements with regard to population density (Pili et al., 2017). However, in both quantitative applications and qualitative case studies, local administrative boundaries (i.e. municipalities) have been largely used as the denominator for demographic indicators in both urban and peri-urban areas (Couch et al., 2007; Garcia & Riera, 2003; Tsai, 2005).

Analysis carried out on a municipal scale presents additional advantages considering that long-term population data are freely available from official statistics and allow both cross-country and within-region reliable comparisons, as well as integration with external sources, such as the statistical data collected annually within economic and socio-demographic surveys. In this regard, municipalities are the smallest spatial domain of most statistical surveys and results from analysis carried out on data collected at that geographical level are easily interpretable by non-technical users such as policy-makers and other stakeholders. Lastly, although regional planning is a centralized policy issue in Spain, municipalities are key local authorities in deciding about land destination, building volume, settlement size, land taxation, and other variables impacting population distribution and density at the local scale, so they appear as a meaningful spatial unit for demographic and urban studies.

Although the vast majority of studies are based exclusively on the analysis of urban density (Garcia & Riera, 2003; Muñiz et al., 2003, 2008; Tsai, 2005), literature on the identification of sub-central locations over recent decades has become increasingly objective and rigorous. Studies carried out during the 1980s and 1990s introduced the delimitation of sub-centers as determined by historical, institutional and administrative criteria (Fernández-Maldonado et al., 2013; Garcia-López & Muñiz, 2010; Roca Cladera et al., 2009). Following these experiences, a renewed literature contributed to the empirical studies concerning the analysis of the structure of urban regions, basically using population density, employment density, and building types (Schneider & Woodcock, 2008). Statistical methods have been developed to corroborate the sub-centers identification process using both parametric and non-parametric approaches (Serra et al., 2014).

Following Roca Cladera et al. (2009) a set of reference thresholds (cut-offs) which enable the identification of sub-center municipalities from the analysis of absolute population values was used in the present study: (i) resident population > 1% of the population inhabiting the whole region and (ii) municipal population density higher than 100% of the density observed in the core city. Since the analysis was carried out on a municipal scale, the core city was identified as the central municipality assumed to represent the political, economic and social ‘heart’ of the urban region. This approach appears as particularly adequate for traditional mono-centric urban regions like Barcelona, shifting (more or less slowly) towards polycentricism.

Territorial Classification of the Study Area

The study was carried out at multiple spatial levels to avoid a scaling bias when analyzing the spatial structure of population growth rates in Barcelona. Six partitions of the area have been considered: (i) the central city, coinciding with the Barcelona’s municipality and corresponding with downtown settlements, (ii) 33 municipalities surrounding the central city and belonging to the Barcelona’s metropolitan area, (iii) 7 municipalities representing sub-central locations situated in the Barcelona’s metropolitan region (see below), (iv) the remaining (peri-urban) municipalities of the Barcelona’s metropolitan region, (v) the remaining 147 (rural) municipalities of the Barcelona’s province (outside the boundaries of Barcelona’s metropolitan region) and, finally, (vi) the whole area coinciding with the administrative NUTS-3 province of Barcelona, including 311 municipalities.

Seven sub-central municipalities (all belonging to the RMB) were identified according to Muñiz et al. (2003) on the base of the density of population, employment and activities (Granollers, Martorell, Matarò, Terrassa, Sabadell, Vilafranca del Penedès, and Vilanova i la Geltrù). They coincide with the sub-centers identified in Muñiz and Garcia-Lopez (2010) as edge cities characterized by a high concentration of jobs in specialized services (business services, as well as finance, insurance and real estate services) surrounded by residential areas, thus mimicking a small-scale replica of the central city. Three head towns were also identified in Barcelona's province outside the RMB (Manresa, Vic, and Berga). Manresa and Vic are the head towns of districts distant no less than 50–60 km from Barcelona with an intermediate density between urban and rural areas but not directly influenced by the urban development observed in the RMB. Berga is the head town of a rural district with low population density and distant 70–80 km from Barcelona. Analysis was aimed at determining a region of influence for these 10 locations in the study area.

Population Data and Demographic Indicators

Demographic data were derived from the Spanish Population Register held by the National Institute of Statistics (INE). Homogeneous data of population balance distinguishing the endogenous component (vital statistics of births and deaths) from the exogenous component (net migration rate) and disseminated annually at the municipal scale for the whole of the country, were used in this study. The investigated time span was partitioned in four intervals lasting 11 years each (1975–1985, 1986–1996, 1997–2007, 2008–2018). A total of 21 variables were calculated at the municipal scale from various official sources (Table 1) with the aim at delineating basic territorial characteristics of the study area. Variables include topographic indicators (elevation, proximity to the sea coast), accessibility (road network), agglomeration (population density), a basic classification of municipalities in 4 rings using dummies (downtown Barcelona, the metropolitan area, sub-central locations, and the remaining part of the metropolitan region), linear distances from 11 locations (inner city, 7 sub-centers and 3 locations in rural areas) and, finally, 2 control variables (distance from Madrid, the Spanish capital, and municipal surface area).

Statistical Analysis

A data mining approach incorporating descriptive statistics, non-parametric inference, and multivariate exploratory analysis was developed in the present study (Rontos et al., 2016; Salvati & Serra, 2016; Serra et al., 2014). Population dynamics decomposing natural population growth and net migration per cent rates were evaluated at the six spatial partitions of the study area for 4 consecutive time periods of 11 years each (1975–1985, 1986–1996, 1997–2007, 2008–2018). Similarity in the spatial distribution of annual rates of natural population growth and net migration was assessed using hierarchical clustering with Ward’s agglomeration rule and Euclidean distance as amalgamation metric. A Principal Component Analysis was run on a data matrix incorporating these two demographic variables and 21 territorial variables (see Table 1) at each of the 311 municipalities in the study area. This analysis was aimed at identifying and decomposing different dimensions of metropolitan expansion in Barcelona and the background variables associated with each extracted component based on loadings, and to (ii) discriminate municipalities with different population dynamics and background characteristics based on component scores. By selecting principal components with eigenvalue > 1, the analysis provides an indirect assessment of urbanization patterns and processes and the related socioeconomic forces. The spatial distribution of component scores was illustrated using maps. Non-parametric Spearman coefficients were finally used to correlate pairwise natural population growth (or net migration rate) with the territorial variables mentioned above. Significant correlations were tested at p < 0.05 after Bonferroni’s correction for multiple comparisons. Spearman correlation analysis was used to identify background indicators displaying a (linear or non-linear) relationship with local-scale population dynamics, possibly distinguishing variables associated with natural population growth from those mostly related to net migration rate.

Results

Population Dynamics in Barcelona

Demographic dynamics in the different territorial partitions of the study area are illustrated in Table 2. The endogenous component (migration) contributes to the overall growth of population in all the study periods, being strongly differentiated over space. In the central city, both endogenous and exogenous components were positive only in the first period (1975–1985), being negative since 1986. Urban shrinkage has progressively slowed down since the late 1990s. The natural growth of resident population shows the highest rates in the metropolitan area of Barcelona and in the municipalities of the metropolitan region surrounding sub-central locations. Sub-centers show an endogenous component (natural balance) that is systematically positive, while decelerating over time. The overall population growth rate was particularly high in the third time interval (1997–2007), because of the intrinsic contribution of migration—systematically higher in peri-urban areas than in central areas and rural districts.

The spatial distribution of endogenous and exogenous growth rates is shown in Fig. 2. Demographic dynamics, both endogenous and exogenous, in the first time interval were more heterogeneous and mixed at the territorial level. Accelerated demographic dynamics were observed in rural districts South of the Pyrenees. In the subsequent period, the overall growth slowed down: the endogenous component was positive only in the municipalities surrounding Barcelona; the exogenous component had positive, modest rates in rural areas. The third time interval was characterized by the highest demographic growth of the study period, and the highest rates were observed in the metropolitan areas more distant from Barcelona, and in municipalities around sub-central locations. In the last time period, the overall growth slowed down and the most significant endogenous and exogenous dynamics corresponded with the sub-centers.

A cluster analysis (Fig. 3) on endogenous and exogenous growth rates (annual base) made it possible to identify similar dynamics over time in both demographic components. Two distinct periods characterized the spatio-temporal dynamics of the endogenous component. Population dynamics over the first time interval (1975–1985) were functionally distinct from those observed in the following three sub-periods, as the dendrogram has clearly evidenced. This distinction discriminates late urbanization – still supported by endogenous dynamics – from suburbanization – mainly dependent on short and medium-range residential mobility. On the contrary, exogenous dynamics were more heterogeneous over space, as they depend on indirect factors that mix short and medium-range internal mobility with international migrations, which have largely contributed to Barcelona’s growth since the 1990s. The comparison between the two dendrograms suggests a temporal decoupling between the two components of demographic growth.

Principal Component Analysis

Principal component analysis extracted five axes that explain 73% of the overall variance, decomposing urban growth into representative dimensions characterized by different context variables and spatial hotspots (Table 3). Component 1 identifies urban growth processes typically oriented along the urban–rural gradient (Fig. 4). The variable that received the highest loading was the distance from Barcelona. The exogenous component was associated with this axis in the first study period while the endogenous component was positively associated with this axis in the three subsequent intervals.

Component 2 outlined a typical east–west gradient in the metropolitan area of Barcelona that was not associated with any demographic variable. Component 3 identified a geographical area east of Barcelona with high population growth in the two intermediate time intervals (1986–1996 and 1997–2007). In this period, endogenous and exogenous growth rates manifested the same spatial dynamics, being correlated positively with Component 3. The sub-centers most affected by urban expansion were Matarò and Granollers, while the sub-centers located to the west of Barcelona did not seem to have the same attractiveness, nor the same endogenous dynamism.

Component 4 identified the endogenous dynamics typical of the first time interval and, in part, of the second period, which mainly concerned the most marginal areas to the east, west and north of Barcelona. These dynamics, characteristic of rural areas outside the metropolitan region, reflect the relatively young demographic structure of these districts, maintaining a residual attraction for medium and long-range migrants. Component 5 completes the analysis of spatial components in Barcelona's urban growth, qualifying the role of coastal areas to the east and west of the city, which have attracted huge migratory flows, especially since 1997. However, coastal districts had also shown negative rates of endogenous growth in the first two time intervals.

Correlation Analysis

The analysis of Spearman's correlation coefficients showed a different correlation profile with the background variables for the endogenous and exogenous components of population growth (Table 4). In the first time interval, natural population growth rate was not associated with any context variable. This result confirms the empirical evidence presented above, and the results of spatial analysis showing how natural growth in that period was modest but widespread throughout the study area. A greater spatial polarization in the endogenous component of population growth was observed in the subsequent time intervals: the natural growth rate decreased significantly with the distance from Barcelona and from 4 sub-centers (Matarò, Terrassa, Sabadell, Granollers). The distance from other sub-centers negatively influenced this demographic rate, even if in a non-constant way over time. On the contrary, the rate increased with the distance from the marginal and rural district of Berga, North of Barcelona.

Taken together, these results show how the endogenous component follows a radio-centric distribution oriented towards central urban areas and demographically larger sub-centers. For instance, the impact of minor sub-centers (e.g. Vilanova and Vilafranca, as well as Manresa and Vic) was substantially limited. On the contrary, net migration growth rate was oriented along the urban gradient only in the first development phase. In the subsequent periods, the impact of some sub-centers was particularly relevant (Granollers, Matarò, Sabadell) attracting non-native population. In these districts, residential mobility and migration have been the primary component of urban growth since the mid-1980s.

Discussion

Following compact urban expansion, economic restructuring, population growth and social segregation in the post-war decades, one of the most diffused changes on the urban scale was the switch towards more diffused and polycentric development patterns (Couch et al., 2007; Gospodini, 2009; Richardson & Chang-Hee, 2004). In the last twenty years, the expansion of large Mediterranean cities was partly stimulated by the European Spatial Planning Framework (Cuadrado-Ciuraneta et al., 2017; Perrin et al., 2018; Zambon et al., 2018) indicating polycentric development as a tool (and, at the same time, a target) to achieve more cohesive territories. Both 'strictly mono-centric' and 'moderately polycentric' urban systems in Southern Europe reveal their wide-range impacts on both forms and functions and their intimate relationship with planning.

While Mediterranean sprawl has been sometimes accompanied by settlement informality, planning deregulation, and lassez-faire policies (Carlucci et al., 2017; Gospodini, 2009; Monclús, 2000), planning promoting the development of polycentric regions revealed less effective in achieving targets of environmental sustainability, social equity, economic competitiveness, and spatial cohesion (Montgomery, 2008). This is particularly relevant in the case of Mediterranean cities featuring long-term compact urban expansion. It was demonstrated how population de-concentration, together with discontinuous and scattered settlements, represents the most recent development pattern in Southern European urban areas. How this development may alter the traditional mono-centric form typically observed in several Mediterranean cities towards a more polycentric spatial asset is an intriguing question that was addressed in this paper by adopting a diachronic and comparative approach (e.g. Lerch, 2019).

Based on these premises, our study debates on the use of demographic indicators derived from vital statistics for the assessment of polycentric vs scattered urban growth in metropolitan regions of Southern Europe (Duvernoy et al., 2018; Salvati et al., 2018; Zambon et al., 2018). Empirical results of this study indicate that peri-urban municipalities, including the sub-centers belonging to Barcelona's metropolitan region, are experiencing rapid transformations reflected into a differential contribution of natural population growth and net migration to the expansion of sub-centers and neighboring locations (Muñoz, 2003).

In this regard, our study proposes a differential model of urban growth with delocalized developmental centers displaying a different contribution of endogenous and exogenous components to total growth over time. More specifically, the study comprehensively assesses urban dynamics by decomposing population growth into natural balance and migration components for each municipality of Barcelona’s province, Spain, between 1975 and 2018. The urban development of Barcelona, starting from the 1970s, has progressively abandoned a mono-centric, compact and dense model, evolving towards a polycentric setting based on the interaction between the central city and multiple (expanding) peri-urban nodes. The analysis carried out on a municipal scale considering annual and decadal data shows a strong differentiation in the spatial structure of the two components of population growth during the study period.

Barcelona's province embodies the characteristics of a moderately polycentric region with widespread (but substantially balanced) medium-density settlements, and a progressive de-concentration of the central city, which however still stands for density and compactness. The municipalities classified as sub-centers grew in number at distances progressively higher from the core city concentrating a high percentage of resident population. This trend, already observed between the 1950s and the 1980s, slowed down in the subsequent decades. The resulting structure, based on a mixture of (sometimes conflicting) demographic waves and planning initiatives, showed a moderate balance of urban functions (e.g. Lerch, 2019). Although it has sometimes been criticized, the Barcelona’s model highlights how processes of de-concentration of the core city and population re-concentration in satellite urban centers have resulted in a morphological structure, if not completed polycentric, at least more balanced over space (Garcia-López & Muñiz, 2010).

Apart from the intuitive divergence observed between urban and rural municipalities, the existence of an intermediate group of municipalities (sub-centers and surrounding locations) featuring specific population trends is interesting and should be better investigated on a regional scale (e.g. Kurek et al., 2015). The diversification of demographic dynamics in districts of the same metropolitan area may indicate specific paths of urban growth in accordance with the theory of city’s life cycle, with sequential phases of urbanization, suburbanization, counter-urbanization, and re-urbanization (Salvati, 2016). At the same time, demographic dynamics may indicate—better than other indicators—that spillover processes, which have shaped Barcelona's expansion over the last thirty years, are producing suburban spaces with moderately dispersed settlements and mixed socioeconomic functions (Couch et al., 2007). This process resulted in a different contribution of natural balance and net migration rate to total population growth in the first decade compared with the most recent period. Interestingly, such transformations have been already observed in both mono-centric and more dispersed/ fragmented cities (e.g. Carlucci et al., 2017; Salvati et al., 2018; Zambon et al., 2018).

While demonstrating that the partial failure in promoting a polycentric spatial asset may reflect the persistence of place-specific morphological, institutional and functional traits and a scarce participation to planning practices in Southern Europe, the present study reconsiders policies for sub-central development, promoting establishment and permanence of high value added economic activities in peri-urban areas (Neuman, 2005). Strategies coping with the intrinsic development of large Mediterranean cities should promote conditions for equity, cohesion, competitiveness and environmental security on a regional scale (Vasanen, 2012). Place-specific and multi-scale strategies promoting the integration of urban competitiveness and socio-environmental sustainability targets are particularly suited to identify new polycentric-oriented developmental patterns (Serra et al., 2014). At the same time, change in urban population is key to understand territorial and environmental dynamics at suburban locations, including the abandonment of rural areas and the consequent expansion of wildfires or the progressive greening of mountainous districts close to areas (Biasi et al., 2015; Perrin et al., 2018; Zambon & Salvati, 2019) . In this view, a broader selection of socioeconomic indicators possibly affecting demographic dynamics seems to be an appropriate tool to explain the territorial mechanisms underlying population growth in metropolitan regions (De Rosa and Salvati, 2016).

Representing an informative base for long-term urban development studies in originally compact cities, our findings contribute to the implementation of more effective policies that (i) stimulate regional competitiveness together with urban containment and more sustainable settlements, and (ii) are applicable to similar socioeconomic and territorial contexts, in both developed and emerging countries. Only a long-term analysis of population and settlement distribution may highlight the latent frame of urban growth suggesting specific measures for urban containment (Gilli, 2009; Hank, 2001; Salvati et al., 2016).

Conclusions

By focusing on the spatial dynamics of a set of demographic and territorial indicators observed during the last century, our study analyzes the long-term expansion of a Mediterranean region representative of a development path from mono-centric to polycentric structures in Southern Europe. The novelty of the study lies in the use of simplified and stable criteria for identification of peculiar demographic dynamics in sub-centers compared with surrounding locations. This provides original elements supporting a renewed interpretation of expansion paths observed in Mediterranean cities, a representative example of compact and dense cities in the world. The relatively long time interval examined is another strength of this study, allowing a refined interpretation of the (increased) urban complexity typical of contemporary Mediterranean cities. The diverging spatial organization of Barcelona’s municipalities suggests how the (supposed) homogeneity in forms and functions observed in the Mediterranean cities is influenced by place-specific development patterns, the spatial organization of historic settlements, and the planning strategies adopted on a local scale, producing path-dependent, fragmented and sometimes peculiar urban forms.

References

Arapoglou, V. P., & Sayas, J. (2009). New facets of urban segregation in southern Europe. European Urban and Regional Studies, 16(4), 345–362.

Balbo, N., Billari, F. C., & Mills, M. (2013). Fertility in advanced societies: A review of research. European Journal of Population, 29(1), 1–38.

Bayona, J., & Gil-Alonso, F. (2012). Suburbanisation and international immigration: The case of the Barcelona Metropolitan Region (1998–2009). Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie, 103(3), 312–329.

Biasi, R., Colantoni, A., Ferrara, C., Ranalli, F., & Salvati, L. (2015). In-between sprawl and fires: Long-term forest expansion and settlement dynamics at the wildland–urban interface in Rome, Italy. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 22(6), 467–475.

Billari, F., & Kohler, H.-P. (2004). Patterns of low and lowest-low fertility in Europe. Population Studies, 58(2), 161–176.

Blanco, I. (2009). Does a “Barcelona model” really exist? Periods, territories and actors in the process of urban transformation. Local Government Studies, 35(3), 355–369.

Bocquier, P., & Bree, S. (2018). A regional perspective on the economic determinants of urban transition in 19th-century France. Demographic Research, 38, 1535–1576.

Boyle, P. J. (2003). Population geography: Does geography matter in fertility research? Progress in Human Geography, 27(5), 615–626.

Burger, M., & Meijers, E. (2012). Form follows function? Linking morphological and functional polycentricity. Urban Studies, 49(5), 1127–1149.

Buzar, S., Ogden, P. E., Hall, R., Haase, A., Kabisch, S., & Steinführer, A. (2007). Splintering urban populations: Emergent landscapes of reurbanisation in four European cities. Urban Studies, 44(4), 651–677.

Carbonaro, C., Leanza, M., McCann, P., & Medda, F. (2016). Demographic decline, population aging, and modern financial approaches to urban policy. International Regional Science Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160017616675916

Carlucci, M., Grigoriadis, E., Rontos, K., & Salvati, L. (2017). Revisiting a hegemonic concept: Long-term ‘Mediterranean urbanization’in between city re-polarization and metropolitan decline. Applied Spatial Analysis and Policy, 10(3), 347–362.

Champion, A. G. (2001). A Changing Demographic Regime and Evolving Polycentric Urban Regions: Consequences for the Size, Composition and Distribution of City Populations. Urban Studies, 38(4), 657–677.

Coleman, D. (2006). Immigration and ethnic change in low-fertility countries: A third demographic transition. Population and Development Review, 32(3), 401–446.

Coleman, D. A. (2008). New Europe, new Diversity. Population Studies, 62(1), 113–120.

Couch, C., Petschel-held, G., & Leontidou, L. (2007). Urban Sprawl in Europe: Landscapes, Land-use Change and Policy. Blackwell.

Cuadrado-Ciuraneta, S., Durà-Guimerà, A., & Salvati, L. (2017). Not Only Tourism: Unravelling Suburbanization, Second-home Expansion and ‘Rural’ Sprawl in Catalonia. Spain. Urban Geography, 38(1), 66–89.

De Muro, P., Monni, S., & Tridico, P. (2011). Knowledge-Based Economy and Social Exclusion: Shadow and Light in the Roman Socio-Economic Model. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 35(6), 1212–1238.

De Rosa, S., & Salvati, L. (2016). Beyond a ‘side street story’? Naples from spontaneous centrality to entropic polycentricism, towards a ‘crisis city.’ Cities, 51, 74–83.

Di Feliciantonio, C., & Salvati, L. (2015). ‘Southern’ Alternatives of Urban Diffusion: Investigating Settlement Characteristics and Socio-Economic Patterns in Three Mediterranean Regions. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie, 106(4), 453–470.

Di Feliciantonio, C., Salvati, L., Sarantakou, E., & Rontos, K. (2018). Class diversification, economic growth and urban sprawl: Evidences from a pre-crisis European city. Quality & Quantity, 52(4), 1501–1522.

Dijkstra, L., Garcilazo, E., & McCann, P. (2015). The effects of the global financial crisis on European regions and cities. Journal of Economic Geography, 15(5), 935–949.

Domingo, A., & Gil-Alonso, F. (2007). Immigration and Changing Labour Force Structure in the Southern European Union. Population, 62(4), 709–727.

Dura-Guimera, A. (2003). Population deconcentration and social restructuring in Barcelona, a European Mediterranean city. Cities, 20(6), 387–394.

Duvernoy, I., Zambon, I., Sateriano, A., & Salvati, L. (2018). Pictures from the other side of the fringe: Urban growth and peri-urban agriculture in a post-industrial city (Toulouse, France). Journal of Rural Studies, 57, 25–35.

Fernández-Maldonado, A. M., Romein, A., Verkoren, O., & Parente Paula Pessoa, R. (2013). Polycentric Structures in Latin American Metropolitan Areas: Identifying Employment Sub-centres. Regional Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.786827

Findlay, A. M., & Hoy, C. (2000). Global population issues: towards a geographical research agenda. Applied Geography, 20(3), 207–219.

Garcia, D., & Riera, P. (2003). Expansion versus density in Barcelona: a valuation exercise. Urban Studies, 40(10), 1925–1936.

Garcia-López, M. A. (2012). Urban spatial structure, suburbanization and transportation in Barcelona. Journal of Urban Economics, 72, 176–190.

Garcia-López, M. A., & Muñiz, I. (2010). Employment Decentralisation: Polycentricity or Scatteration? The Case of Barcelona. Urban Studies, 47(14), 3035–3056.

Garcia-López, M. A., & Muñiz, I. (2011). Urban spatial structure, agglomeration economies, and economic growth in Barcelona: An intra-metropolitan perspective. Papers in Regional Sciences, 92(3), 515–534.

Garcia-Ramon, M. D., & Albet, A. (2000). Pre-Olympic and post-Olympic Barcelona, a model for urban regeneration today? Environment and Planning A, 32, 1331–1334.

Gavalas, V. S., Rontos, K., & Salvati, L. (2014). Who becomes an unwed mother in Greece? Sociodemographic and geographical aspects of an emerging phenomenon. Population, Space and Place, 20(3), 250–263.

Gil-Alonso, F., Bayona-i-Carrasco, J., & Pujadas-i-Rúbies, I. (2016). From boom to crash: Spanish urban areas in a decade of change (2001–2011). European Urban and Regional Studies, 23(2), 198–216.

Gilli, F. (2009). Sprawl or Reagglomeration? The dynamics of employment deconcentration and industrial transformation in greater Paris. Urban Studies, 46(7), 1385–1420.

Gospodini, A. (2009). Post-industrial trajectories of Mediterranean European cities: the case of post-Olympics Athens. Urban Studies, 46, 1157–1186.

Hank, K. (2001). Regional fertility differences in western Germany: An overview of the literature and recent descriptive findings. International Journal of Population Geography, 7(4), 243–257.

Hatz, G. (2009). Features and dynamics of socio-spatial differentiation in Vienna and the Vienna metropolitan region. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geographie, 100(4), 485–501.

Helbich, M. (2012). Beyond Postsuburbia? Multifunctional Service Agglomeration in Vienna’s Urban Fringe. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geographie, 103(1), 39–52.

Hoekveld, J. J. (2015). Spatial differentiation of population development in a declining region: The case of Saarland. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 97(1), 47–68.

Kabisch, N., & Haase, D. (2011). Diversifying European agglomerations: evidence of urban population trends for the 21st century. Population, Space and Place, 17(3), 236–253.

Kabisch, N., Haase, D., & Haase, A. (2012). Urban population development in Europe 1991–2008: The examples of Poland and UK. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 36(6), 1326–1348.

Kroll, F., & Kabisch, N. (2012). The relation of diverging urban growth processes and demographic change along an urban–rural gradient. Population, Space and Place, 18(3), 260–276.

Kulu, H. (2013). Why do fertility levels vary between urban and rural areas? Regional Studies, 47(6), 895–912.

Kulu, H., & Boyle, P. J. (2009). High fertility in city suburbs: Compositional or contextual effects? European Journal of Population, 25(2), 157–174.

Kurek, S., Wójtowicz, M., & Gałka, J. (2015). The changing role of migration and natural increase in suburban population growth: The case of a non-capital post-socialist city (The Krakow Metropolitan Area, Poland). Moravian Geographical Reports, 23(4), 59–70.

Lee, R. D., & Reher, D. S. (2011). Introduction: The landscape of demographic transition and its aftermath. Population and Development Review, 37(s1), 1–7.

Lerch, M. (2013). Fertility decline during Albania’s societal crisis and its subsequent consolidation. European Journal of Population, 29(2), 195–220.

Lerch, M. (2019). Regional variations in the rural-urban fertility gradient in the global South. PLoS One, 14(7), e0219624.

Lesthaeghe, R. (2010). The Unfolding Story of the Second Demographic Transition. Population and Development Review, 36(2), 211–251.

Longhi, C., & Musolesi, A. (2007). European cities in the process of economic integration: towards structural convergence. Annals of Regional Science, 41, 333–351.

López Gay, A. (2007). Canvis residencials i moviments migratoris en la renovació poblacional de Barcelona. Departamento de Geografía de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Tesis doctoral.

López Gay, A. (2014). 175 años de series demográficas en la ciudad de Barcelona. La migración como componente explicativo de la evolución de la población. Biblio 3W. Revista Bibliográfica de Geografía y Ciencias Sociales, 19, 1098.

Lucy, W. H., & Phillips, D. L. (2000). Suburban decline: The next urban crisis. Issues in Science and Technology, 17(1), 55–62.

Lutz, W., & Qiang, R. (2002). Determinants of human population growth. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 357(1425), 1197–1210.

Marshall, T. (2000). Urban planning and governance: is there a Barcelona model? International Planning Studies, 5(3), 299–319.

Meijers, E. (2008). Measuring polycentricity and its promises. European Planning Studies, 16(9), 1313–1323.

Módenes, J. A. (1998). Flujos espaciales e itinerarios biográficos: la movilidad residencial en el área de Barcelona. Departamento de Geografía de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Tesis doctoral.

Monclús, F. (2000). Barcelona’s planning strategies: from “Paris of the south to capital of the west Mediterranean.” GeoJournal, 51, 57–63.

Montgomery, M. R. (2008). The urban transformation of the developing world. Science, 319(5864), 761–764.

Morelli, V. G., Rontos, K., & Salvati, L. (2014). Between suburbanisation and re-urbanisation: revisiting the urban life cycle in a Mediterranean compact city. Urban Research & Practice, 7(1), 74–88.

Muñiz, I., Garcia-López, M. A., & Galindo, A. (2008). The Effect of Employment Sub-centres on Population Density in Barcelona. Urban Studies, 45(3), 627–649.

Muñiz, I., Galindo, A., & Garcia-Lopez, M. A. (2003). Cubic spline population density functions and satellite cities delimitation: the case of Barcelona. Urban Studies, 40(7), 1303–1321.

Muñiz, I., & Garcia-Lopez, M. A. (2010). The polycentric knowledge economy in Barcelona. Urban Geography, 31(6), 774–799.

Muñoz, F. (2003). Lock living: Urban sprawl in Mediterranean cities. Cities, 20, 381–385.

Nel·lo, O. (2011). The Five Challenges of Urban Rehabilitation. The Catalan Experience. Urban Research and Practice, 4(3), 308–325.

Neuman, M. (2005). The compact city fallacy. Journal of Planning and Education Research, 25(1), 11–26.

Parr, J. (2004). The polycentric urban region: a closer inspection. Regional Studies, 38(3), 231–240.

Paul, V., & Tonts, M. (2005). Containing urban sprawl: trends in land-use and spatial planning in the Metropolitan Region of Barcelona. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 48(1), 7–35.

Pérez, J. M. G. (2010). The real estate and economic crisis: An opportunity for urban return and rehabilitation policies in Spain. Sustainability, 2(6), 1571–1601.

Perrin, C., Nougarèdes, B., Sini, L., Branduini, P., & Salvati, L. (2018). Governance changes in peri-urban farmland protection following decentralisation: A comparison between Montpellier (France) and Rome (Italy). Land Use Policy, 70, 535–546.

Pili, S., Grigoriadis, E., Carlucci, M., Clemente, M., & Salvati, L. (2017). Towards sustainable growth? A multi-criteria assessment of (changing) urban forms. Ecological Indicators, 76, 71–80.

Richardson, H. W., & Chang-Hee, C. B. (2004). Urban sprawl in Western Europe and the United States. Ashgate.

Roca Cladera, J., Marmolejo Duarte, C. R., & Moix, M. (2009). Urban structure and polycentrism: towards a redefinition of the sub-centre concept. Urban Studies, 46(13), 2841–2868.

Rontos, K., Grigoriadis, S., Sateriano, A., Syrmali, M., Vavouras, I., & Salvati, L. (2016). Lost in Protest, Found in Segregation: Divided Cities in the Light of the 2015 “Oki” Referendum in Greece. City, Culture and Society, 7(3), 139–148.

Salvati, L., Sateriano, A., & Grigoriadis, E. (2016). Crisis and the city: Profiling urban growth under economic expansion and stagnation. Letters in Spatial and Resource Sciences, 9(3), 329–342.

Salvati, L. (2016). The Dark Side of the Crisis: Disparities in per Capita income (2000–12) and the Urban-Rural Gradient in Greece. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie, 107(5), 628–641.

Salvati, L., & Carlucci, M. (2017). Urban growth, population, and recession: Unveiling multiple spatial patterns of demographic indicators in a Mediterranean City. Population, Space and Place, 23(8), e2079.

Salvati, L., Zambon, I., Chelli, F. M., & Serra, P. (2018). Do spatial patterns of urbanization and land consumption reflect different socioeconomic contexts in Europe? Science of the Total Environment, 625, 722–730.

Salvati, L., & Serra, P. (2016). Estimating rapidity of change in complex urban systems: A multidimensional, local-scale approach. Geographical Analysis, 48(2), 132–156.

Schneider, A., & Woodcock, C. E. (2008). Compact, dispersed, fragmented, extensive? A comparison of urban growth in twenty-five global cities using remotely sensed data, pattern metrics and census information. Urban Studies, 45(3), 659–692.

Serra, P., Vera, A., Tulla, A. F., & Salvati, L. (2014). Beyond urban–rural dichotomy: Exploring socioeconomic and land-use processes of change in Spain (1991–2011). Applied Geography, 55, 71–81.

Torrens, P. M. (2006). Simulating sprawl. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 96(2), 248–275.

Tsai, Y. (2005). Quantifying urban form: compactness versus sprawl. Urban Studies, 42(1), 141–161.

Turok, I., & Mykhnenko, V. (2007). The trajectories of European cities, 1960–2005. Cities, 24, 165–182.

Van Nimwegen, N. (2013). Population change in Europe: turning challenges into opportunities. Genus, 69(1), 103–125.

Vasanen, A. (2012). Functional Polycentricity: Examining Metropolitan Spatial Structure through the Connectivity of Urban Sub-centres. Urban Studies, 49(16), 3627–3644.

Vega, A., & Reynolds-Feighan, A. (2008). Employment Sub-centres and Travel-to-Work Mode Choice in the Dublin Region. Urban Studies, 45(9), 1747–1768.

Veneri, P. (2013). The identification of sub-centres in two Italian metropolitan areas: a functional approach. Cities, 31, 177–185.

Vobetká, J., & Piguet, V. (2012). Fertility, Natural Growth, and Migration in the Czech Republic: an Urban–Suburban–Rural Gradient Analysis of Long-Term Trends and Recent Reversals. Population, Space and Place, 18(3), 225–240.

Westerink, J., Haase, D., Bauer, A., Ravetz, J., Jarrige, F., & Aalbers, C. B. E. M. (2013). Dealing with sustainability trade-offs of the compact city in peri-urban planning across European city regions. European Planning Studies, 21(4), 473–497.

Zambon, I., Serra, P., Sauri, D., Carlucci, M., & Salvati, L. (2017). Beyond the ‘Mediterranean city’: Socioeconomic disparities and urban sprawl in three Southern European cities. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 99(3), 319–337.

Zambon, I., Benedetti, A., Ferrara, C., & Salvati, L. (2018). Soil matters? A multivariate analysis of socioeconomic constraints to urban expansion in Mediterranean Europe. Ecological Economics, 146, 173–183.

Zambon, I., & Salvati, L. (2019). Metropolitan growth, urban cycles and housing in a Mediterranean country, 1910s–2010s. Cities, 95, 102412.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vinci, S., Egidi, G., López Gay, A. et al. Population Growth and Urban Management in Metropolitan Regions: the Contribution of Natural Balance and Migration to Polycentric Development in Barcelona. Appl. Spatial Analysis 15, 71–94 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12061-021-09395-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12061-021-09395-2