Abstract

The present study concerns the Phoenician-Punic site of Motya, a small island set in Western Sicily (Italy), in the Marsala Lagoon (Stagnone di Marsala), between Trapani and Marsala. A big disposal pit, datable to between the first half of the 8th and the mid-6th century bc, was identified in Area D. This context was sampled for plant macro-remains through bucket flotation. Palynological treatment and analysis were also performed on soil samples collected from each of the identified filling layers. The combination of the study of macro- and micro-remains has shown to be effective in answering questions concerning introduced food plants and agricultural practices, and native plants, including timber use. Here we investigate if a waste context can provide information about Phoenicians at Motya and their impact on the local plant communities. We found that human diet included cereals (mostly naked wheat), pulses and fruits. A focus was placed on weeds (including Lolium temulentum and Phalaris spp.) referable to different stages of crop processing. This aspect was enriched by the finding of cereal pollen, which suggests that threshing (if not even cultivation) was carried out on site. Palynology also indicates an open environment, with little to no forest cover, characterized by complex anthropogenic activities. Anthracology suggests the presence of typical Mediterranean plant taxa, including not only the shrubs Pistacia lentiscus and Erica multiflora, but also evergreen oaks. The presence of a stone pine nut and of Pinus pinea/pinaster in the pollen rain is noteworthy, suggesting the local occurrence of these Mediterranean pines outside their native distribution range. This represents the first such find in the central Mediterranean. Finally, the present study allows us to compare Motya’s past environment with the present one. The disappearance of Juniperus sp. and Erica arborea from the present-day surroundings of the Marsala lagoon appears to be related to land-overexploitation, aridification or a combination of both processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

“Phoenicians” is the label given by Greeks to a multifaceted culture of the coast of the Levant, which spread across the Mediterranean between the second and the first millennium bc bringing a new socio-economic model – that of the port-city – and a revolutionary cultural tool: the alphabet. This was not the only innovative element transplanted in the Western Mediterranean (López-Ruiz and Doak, 2019). Epigraphy and written sources have provided a large set of data on the Phoenicians in the Western Mediterranean, however archaeology is enlarging our knowledge on their materiality and daily life in Phoenician centres. Knowledge regarding their use of plants and on the important impact they had on the ancient environment is limited to studies on Phoenician plant fossils restricted to Sardinia, Italy (e.g. Buosi et al. 2017; Ucchesu et al. 2017; Sabato et al. 2019), Southern Iberia (e.g. Buxò 2008), Tunisia (van Zeist et al. 2001), Morocco (Grau Almero 2011) and Lebanon (Badura et al. 2016; Orendi and Deckers 2018). Such studies focus on macro-remains, with pollen sometimes being introduced as a complementary tool (e.g. van Zeist et al. 2001; Sabato et al. 2015).

This study intends to substantially widen this panorama including Western Sicily, which was a main landing point for Phoenician communities during their expansion in the Mediterranean.

Although numerous archaeobotanical studies have been performed on Sicilian material (total of 32; Mercuri et al. 2015), studies on early to mid-first millennium bc material in Sicily are scarce and only concern the sites of Rocchicella-Palikè near Mineo (Castiglioni 2008), Monte Polizzo (Salemi) and Selinunte (Stika 2004; Stika et al. 2008; Stika and Heiss 2013). Pollen records confirm a heavy environmental impact during the period of Phoenician occupation with the opening of coastal forests in both inland and coastal Sicily (Sadori and Narcisi 2001; Noti et al. 2009; Tinner et al. 2009; Calò et al. 2012; Sadori et al. 2013).

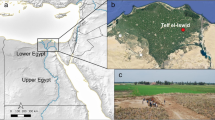

Motya (also known as San Pantaleo) is a small island (ca. 40 ha) located off the western coast of Sicily (Fig. 1a), in the Marsala Lagoon, between Trapani and Marsala (Fig. 1b). Thanks to its sheltered and strategic position in the middle of the Mediterranean, as well as to the presence of fresh-water sources (Di Mauro et al. 2011), the site has been inhabited since at least the 17th century bc and was chosen by Phoenicians as a colony in the 8th century bc. Although the Phoenician-Punic occupation lasted until the siege of Motya in 397 bc, the island continued to be inhabited in the following centuries (Nigro 2007). The “Missione Archeologica a Mozia” of Sapienza University is responsible for excavations on the island since 1964, under the lead of Lorenzo Nigro starting from 2002.

a The geographic location of Motya with reference to the Iron Age sites of Monte Polizzo and Selinunte, the pollen sequences of Gorgo Basso and Pergusa, and other locations mentioned in the text; b the position of Motya within the Marsala lagoon; c the position of Area D within the site of Motya, courtesy of Sapienza University of Rome Expedition to Motya

These recent excavations have provided stratigraphic sequences anchored to radiocarbon dates, which backdate the acquaintance of Levantine peoples with the island to the second millennium bc, as described by the sequence of material cultures (Nigro 2016). Archaeobotanical analyses have so far only been performed in the area of the sanctuary of Cappiddazzu, revealing information regarding the use of plants in animal sacrifices (Moricca et al. 2020b), and on the submerged causeway which once connected the Northern Gate of Motya to the opposite coast near the district of Birgi (Terranova et al. 2009).

The present paper is aimed at framing the Phoenician inhabitants of the small island of Motya in the landscape they have modified through centuries, cultivating and exploiting the natural resources of the territory starting from the earliest stages of the Phoenician settlement. This allows assessment of the Levantines/Phoenicians’ contribution to the modification of the environment and the cultural contribution given by them in terms of plant introduction and use both for nutritional and curative purposes (Moricca et al. 2020b).

This is the first systematic study of this kind for a Phoenician site in Sicily, combining the study of seeds and fruits, wood and pollen. The novelty of this study is also given by the peculiar context itself, a rich waste pit providing an insight into daily life during two centuries (ca. 750–550 bc) of continuous occupation of the site.

Materials and methods

The archaeological site of Motya is divided into a series of areas labelled using letters. Area D lies on the south-eastern slope of the Acropolis of Motya, in the centre of the island, with the highest altitude of 6 m a.s.l. (Fig. 1c). Recent excavations by Sapienza University of Rome revealed that this area houses the oldest settlement stages at Motya, as already hypothesized by J. Whitaker in 1921 (Nigro et al. 2002). During the campaigns of 2004–2005 and 2016–2019, a large disposal pit, F.1112, was uncovered and excavated. This showed signs of burning and was therefore selected for archaeobotanical analysis. Apart from the archaeobotanical remains, the excavation has revealed an impressive amount of other materials, which include shells, animal bones and broken ceramics. The latter have provided a chronology ranging from the first half of the 8th to the mid-6th century bc (this study).

Six stratigraphic units (SU) – SU 1112, SU 2268, SU 1406, SU 1407, SU 1492 and SU 7234 – corresponding to four depositional phases, were identified in the studied deposit. These stratigraphic units spread over an area of 29 m2 to a depth of 1.35 m (Fig. 2). They correspond to a series of events close in time, which have the most recent chronological limit in the mid-6th century bc. On this date, a radical rearrangement of the area took place modifying the plan and the urban layout, and, probably, also its function. The archaeological deposit consists of a series of fills of organic and inorganic materials, dating from the mid-8th to the mid-6th century bc (Table 1). Four filling layers (FL) have been identified and dated, using the range of pottery content. These correspond to four distinct anthropological phases through time, each ending with an in-situ fire.

Macro-remains

A pilot study was carried out on preliminary samples retrieved from the pit in summer 2017. An unknown volume of material from the top of SU 1112 was dry sieved on a series of nested sieves of mesh size 10, 5 and 2 mm.

Systematic sampling of the pit was carried out during the excavation campaign of 2018. Samples of known volume (333 L total; ESM Table 1) of sediment coming from each of the filling layers were processed on-site using bucket floatation. This allowed the charred material to float on the water surface and to be caught on a sieve of mesh size 250 µm. The heavy residue was water sieved using a mesh size of 1 mm in order to collect any residual remains, both charred and mineralized. Once dry, the sediments were brought to the lab and sieved on a series of nested sieves with mesh size 2, 1 and 0.5 mm (for the light fraction) or 5, 2 and 1 mm (the heavy fraction), in order to increase the efficiency of hand-picking. Archaeobotanical remains were subsequently separated from the residual sediment. Carpological remains were observed using a Leica M205C stereomicroscope (magnification between 8× and 78×). We acquired high resolution images of plant macrofossils with a Leica IC80 HD camera using the software Leica Application Suite, version 4.5.0. Seeds and fruits were identified using atlases and online resources, including Jacomet (2006), Neef et al. (2012), Cappers and Bekker (2013), Nesbitt (2016) and Pignatti et al. (2017–2019). Anthracological remains >2 mm were selected for analysis using a Nomarski microscope (phase contrast microscope with differential interference contrast) and identified using atlases available for the study of Mediterranean trees and shrubs (Schweingruber 1990). Unfortunately it was not possible to use the novel approach involving High Resolution Magnetic Resonance Imaging proposed by Capuani et al. (2020), as it is not suitable for charred wood. The botanical nomenclature follows the Euro + Med PlantBase (2006) for carpological remains, Schweingruber (1990) for anthracological remains, Cambini (1967) for Quercus taxa and Greguss (1955) for Pinus taxa. The findings issuing from plant remains (charcoal, seeds) and pollen were compared with the data issuing from previous literature concerning current local vascular flora (Pasta 2004; Scuderi et al. 2007 and references therein) and vegetation (Guarino and Pasta 2017 and references therein).

Pollen

Palynological analysis was performed in support of the study of macro-remains. A soil sample was collected from each filling layer, for a total of four samples. In case of filling layer I–III, comprised of SU 1112 and 2268, and filling layer IV, comprised of SU 1406 and 1407, a single sample was collected per filling layer (Table 1). The samples were chemically processed following Faegri and Iversen (1989) at the Laboratory of Archaeobotany and Palynology at Sapienza University of Rome. Sample residues were later sieved using a 10 µm nylon sieve and treated with ultrasound at the Department of Geology and Geoenvironment of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens in order to obtain clearer slides. A known quantity of Lycopodium spores was added to each weighted sample in order to estimate pollen and non-pollen palynomorphs concentration (NPPs; Stockmarr 1971). Pollen identification was carried out using atlases (Reille 1992–1998; Beug 2004). The features reported by Smit (1973) were used to distinguish oak pollen taxa. The identification key by Andersen (1979), readapted to glycerine as a mounting medium, was used to distinguish among cereal taxa. The pollen diagram was drawn using the TILIA program (Grimm 1991).

Results

Macro-remains: fruits and seeds

A total of 3,151 carpological remains, belonging to 78 different plant taxa, were recovered from the studied deposit (ESM Table 1; Fig. 2). These also include the remains recovered during the preliminary sampling of 2017, although these are only taken into consideration for qualitative analysis. Although most plant remains were preserved by charring (Fig. 3), some mineralized specimens were also present. Unfortunately, due to fragmentation, the variable conservation state and intra- and inter-species variability, it was not always possible to identify specimens at the species level. The most represented taxa were Hordeum vulgare L. (barley, both hulled and naked), Triticum aestivum L./T. durum Desf. (naked wheat), Vitis vinifera L. (grape), and wild grasses such as Phalaris sp. and Lolium temulentum L. (darnel). Nonetheless, a wide variety of cereals including Avena cf. sativa L. – oat, Triticum turgidum ssp. dicoccon (Schrank) Thell., also known as T. dicoccon (Schrank) Schübl – emmer wheat, and T. monococcum L. – einkorn, represented also by scarce chaff remains, and pulses (Lens culinaris Medik. – lentil, Pisum sativum L. – green pea, Vicia ervilia (L.) Willd. – bitter vetch, V. faba L. – faba bean, and Vicia/Lathyrus was found.

Selected carpological remains from pit F.1112. a Triticum turgidum ssp. dicoccon, b Triticum aestivum/durum, c Hordeum vulgare (hulled); d H. vulgare (hulled and sprouted); e H. vulgare (rachis node); f Pisum sativum; g Lens culinaris; h Vicia/Lathyrus; i Vicia ervilia; j Vitis vinifera (seed); k Vitis vinifera (pedicel); l Ficus carica; m Punica granatum; n Lolium temulentum; o Phalaris cf. minor; p Briza maxima; q Sherardia arvensis; r Silene vulgaris. Scale bars = 1 mm

Pips, undeveloped pips and pedicels of V. vinifera were present. Olea europaea L. (olive) endocarps, Punica granatum L. (pomegranate) pericarp fragments and Pinus pinea L. (stone pine) seed and scale fragments were also found. Crataegus monogyna Jacq. (common hawthorn), Crataegus sp. and Ficus carica L. (Fig. 3) completed the fruit assemblage. A fragment of Linum usitatissimum L. (linseed) seed was also retrieved.

Approximately 40% of the assemblage is constituted of weeds typically growing in cultivated crop fields and ruderal species. The most abundant taxa belonging to these categories are Lolium temulentum, Phalaris sp. and Phalaris cf. minor Retz. However, remains of Calendula arvensis (Vaill.) L., Chenopodiastrum murale (L.) S. Fuentes & al., Euphorbia helioscopia L., Heliotropium europaeum L., Sherardia arvensis L., Silene sp., Urtica membranacea Poir and Urtica urens L. were also found, among others.

Macro-remains: wood charcoals

The anthracological analysis concerned a total of 870 fragments of charred wood. These have been identified as belonging to 19 different taxa (ESM Table 2). Evergreen oaks (likely Quercus ilex L. or Q. coccifera L.) account for ca. 24% of the assemblage (211 fragments), followed by Pistacia lentiscus L. (lentisk: 14%), Olea europaea (olive: 12%) and Rhamnus/Phillyrea (10%). Some fragments were identified as Pistacia sp. (10%) and Quercus sp. (2%) due to limited size or bad preservation state. However, it is probable that they are related to lentisk or terebinth, and to evergreen oaks, respectively. As for the fragments referred to Rhamnus/Phillyrea, although these two genera belong to two different families, i.e. Rhamnaceae and Oleaceae, their identification turns out to be difficult. This is because they show a very similar wood anatomy, with diffuse-porous wood, vessels in a dendritic and diagonal pattern and heterogeneous, bi- or tri-seriate rays and spiral thickenings (Schweingruber 1990). For this reason, fragments with the above described characteristics have been named as Rhamnus/Phillyrea. In more detail, Phillyrea latifolia L. occurs rather frequently in the remnant nuclei of sclerophyllous maquis in the coastal areas of western Sicily. As for Rhamnus, R. alaternus L. currently occurs in the Stagnone area at Isola Lunga (Di Martino and Perrone 1970), whilst R. lycioides L. ssp. oleoides (L.) Jahand. & Maire frequently grows together with Chamaerops humilis L. and Quercus coccifera L. in the low-growing sclerophyllous scrub of southwestern Sicily (Brullo et al. 2008).

Other abundant taxa are represented by Erica arborea type (5.5%), E. multiflora type (5%), E. arborea/multiflora (5%), Pistacia terebinthus (4%) and Fabaceae Faboideae (4%). Almost all Fabaceae present a strong structural variability, making identification difficult. Faboideae are a subfamily of Fabaceae including shrubby brooms, whose wood is generally semi-ring porous, characterized in the transversal section by vessels arranged in an oblique to dendritic pattern with paratracheal parenchyma (Bouchaud et al. 2017). Longitudinally it presents spiral thickenings, homogenous to heterogeneous rays, of variable width (Schweingruber 1990). These features were observed in the studied fragments, which could potentially correspond to Cytisus infestus C. Presl, a thorny summer-deciduous shrub very common in the degraded oakwoods and garrigues of the thermomediterranean Sicilian belt, or to Spartium junceum L., more common on the hills of inner Sicily, especially in human-disturbed areas.

Other identified taxa include Pinus sylvestris-montana group (0.8%; Greguss 1955), Capparis spinosa L. (0.6%), Cupressus sempervirens L. (0.2%), Juniperus sp. (0.2%), Rosaceae Maloideae (0.2%) and Rosaceae Rosoideae (0.2%).

Microremains: Pollen and NPPs

The total terrestrial pollen count in the studied samples ranges between 107 and 522 grains. Pollen preservation is variable, and concentration is in a range of 49–1,790 pollen grains/g. A total of 46 taxa have been identified (Fig. 4). Pollen from trees and shrubs is scarce, belonging to the Mediterranean forest with both evergreen (Quercus ilex type, including all evergreen Mediterranean oak species except Q. suber, and Pinus), and deciduous elements (deciduous and semi-deciduous oaks and the riparian Alnus) and maquis (Ericaceae, Juniperus, Pistacia). Pollen identification also evidenced locally cultivated tree taxa (Juglans, Vitis).

Most of the identified taxa correspond to herbaceous plants. Asteraceae Asteroideae, present in all samples with percentages ranging from 25 (FL I–III) to 70 (FL IV), are the most abundant pollen type, followed by Poaceae, with a maximum of 25% (FL V), and Asteraceae Cichorioideae, peaking at 19% (FL VI).

Cultivated and ruderal plants are highly represented amongst the herbaceous taxa, and include cereals (Avena/Triticum and Hordeum group), Plantago lanceolata type, Plantago undiff., Urtica, Brassicaceae, Fabaceae and Rumex. Pollen identified as Alchemilla, currently absent in the Sicilian flora, could correspond to Aphanes, which has a very similar morphology.

The non-pollen palynomorphs (NPPs) are Glomus, Pseudoschizaea, Tecaphora, Turbellaria and Rotifera eggs. The first and the second are considered indicators of erosion in lacustrine records (Sadori 2018).

Discussion

The pit F.1112 was identified as a context with high potential for archaeobotanical analysis due to the signs of direct burning. The plant remains represent primary refuse, being accumulated and occasionally burned in order to reduce their volume (Fuller et al. 2014). The archaeological interpretation of such disposal contexts is quite complex, although extensive information regarding diet, agricultural practices, use and selection of plants, and the surrounding environment may be obtained from the analysis of archaeobotanical remains. The concentration of carpological remains in the studied sediment is quite low for this type of context (ca. 6 remains/l), but the scarcity may have been influenced by repeated fires, possibly causing the complete combustion of numerous remains. Such burnings are also responsible for very low pollen concentrations.

Although most plant remains were preserved by charring, the most common preservation method for materials in the Mediterranean (Peña-Chocarro and Pérez-Jordà 2019), some mineralized specimens were also present. This is partly due to some taxa (e.g. Echium plantagineum L., Heliotropium europaeum L.) undergoing a process called biomineralization, due to their intrinsic properties (van Zeist and Bakker-Heeres 1982). Another source of mineralization in this context may be organic material (human faeces, bones or other organic remains), rich in calcium phosphate (Peña-Chocarro and Pérez-Jordà 2019), which may have affected F. carica achenes and two V. vinifera seeds.

Implications for Phoenician diet and land use

A relevant portion of the assemblage is constituted of a wide variety of cereals and pulses, which provide information about the diet of local settlers. Cereals are represented, in order of abundance, by Hordeum vulgare, Triticum aestivum/durum, T. turgidum ssp. dicoccon and T. monococcum. The concentration of the latter is quite low, suggesting that it was not cultivated intentionally, but was a legacy of previous cultivations and eventually behaved as a weed. Unfortunately, due to fragmentation and taphonomic factors, it was not possible to identify all grains at a species level, with some being identified as Triticum sp. or, more broadly, as cereals. The prevalence of barley and naked wheat in the cereal assemblage can also be seen in the Early Iron Age site of Monte Polizzo and the Archaic-Corinthian site of Selinunte, both in western Sicily (Stika et al. 2008).

The finding of naked barley in the assemblage represents an aspect worth focusing on. Despite naked and hulled barley requiring similar conditions for growth, with the former being more palatable and needing less processing before human consumption, the naked variety decreases noticeably in European archaeobotanical assemblages from the Neolithic to the Iron Age/Roman period, being found only in association with hulled barley in Italy (Lister and Jones 2013). This is probably due to its higher susceptibility to insect attack and parasitic diseases, as well as the rise of naked wheat, which has a higher yield and is more suitable for making bread-like products, with barley being used only as animal fodder (Lister and Jones 2013).

Several germinated caryopses of H. vulgare, T. turgidum ssp. dicoccon and T. aestivum/durum were also retrieved from pit F.1112. This germination can result from processes such as damp storage or wetting while still in the field (Bouby et al. 2011).

Pulses are less numerous than cereals, but just as varied. The most abundant is Pisum sativum, followed by Vicia/Lathyrus, Vicia faba, Lens culinaris and Vicia ervilia. While bitter vetch and, above all, grass pea (Lathyrus sativus) are currently only grown as fodder due to the presence of neurotoxins, it is possible that these were removed by soaking the seeds in water before cooking, as hypothesized for Byzantine Carthage (van Zeist et al. 2001). It is, however, more probable that, while naked barley, and naked and hulled wheat were used for human consumption, hulled barley was a potential source of fodder, along with oat (Avena cf. sativa), bitter vetch, other vetches and the waste deriving from the early processing stages of all the above-mentioned cereals (Jones 1998).

Our data provide information about Phoenician agricultural practice and crop storage. The presence of numerous weed seeds in all depositional layers of F.1112, in addition to cereal grains and chaff, points towards the assemblage representing waste products, greatly correlated to different stages of crop processing, such as winnowing. Although past studies have tried to analyse similar groups of plant remains in order to distinguish settlements of primary arable producers from those receiving the harvest, these studies have been criticized by Stevens (2003). He rather suggested an identification of the routine processing stages, whose waste is more likely to become charred, and depend mostly on the state in which the crops are stored. This is also because bulk processing usually takes place in a short period of time following the harvest and may be carried out in the field, away from any fire, resulting in a loss of the waste that would distinguish producers from consumers. In contrast, crop processing of stored crops before consumption occurred more frequently, and its waste was more likely to become charred. The Motya deposit indicates processing of stored crops before consumption. This is confirmed by the application of the ratio of small to large weed seeds, and the proportion of weed seeds to crop seeds proposed by Stevens (2003). The assemblage of F.1112 appears to fall in the area defined as “household” processed, with a weed seed to grain percentage of 54% and large weed seeds representing only 34% of the weed assemblage, suggesting that most of the processing stages were carried out on a daily basis after storage. What does not correspond to Stevens’ description is the extremely low percentage of chaff. This difference is partly due to both free-threshing cereals and glume wheats being present amongst the retrieved remains, with barley (hulled and naked) and naked wheats constituting between 65% and 75% of the cereal assemblage per each stratigraphic unit. This results in most of the rachises being removed during threshing, in contrast with hulled wheats, where the rachis often remains attached to the spikelet (Stevens 2003). Jones (1990) argues that the only way to analyse mixed assemblages is a multivariate approach, calculating the grain/chaff ratio separately for each species. Applying this to the F.1112 assemblage shows in fact a great difference, with no T. aestivum/durum chaff, a chaff/grain ratio of 1:62 for H. vulgare (mostly hulled) and of 1:6 for T. turgidum ssp. dicoccon, supporting the evidence of the low chaff concentration being due to the abundance of free-threshing cereals.

Taphonomic processes are another potential factor responsible for the extremely low percentage of chaff, as chaff is more easily damaged by fire than grain, especially in oxidizing conditions (Bates et al. 2017). Archaeological evidence suggests numerous burning events in the pit F.1112 in order to reduce the volume of waste, to gain space for new material and reduce bad smells, making it less likely for fragile plant parts to be found in the archaeobotanical assemblage. Additional data regarding local agricultural practices are provided by the presence of low growing species, like Sherardia arvensis, which suggests harvesting low down the culm (Reed 2016). Palynological evidence supports our interpretation that at least threshing (if not also cultivation) was carried on-site. Although in low concentrations, Hordeum group pollen was found in three out of the four investigated filling layers of pit F.1112. In addition to this, Avena/Triticum group pollen was identified in filling layer IV. The only filling layer in which cereal pollen was absent is filling layer VI, the oldest one. Cereals produce large pollen grains traveling over very short distances and are generally underrepresented in pollen records (Mercuri et al. 2013). These grains are brought into settlements along with crops and are released mostly during threshing and winnowing (Montecchi and Mercuri 2018). For this reason, cereal pollen is expected to be found in this kind of context. It is more likely that the whole crop processing procedure was carried out in situ, while the remains of the first stages of processing were given to animals as fodder (Fuller et al. 2014). According to the demographic model created by Nigro (2017) by matching all available archaeological data with ethnographic resources, the estimated population of Motya between the 8th and 7th century bc was ca. 1,400 people. Despite the small size of the island, Nigro (2017) hypothesized that at least 30 ha were kept free for agriculture, animal breeding and other productive activities. Of these, 14.1 ha are thought to have been dedicated to cereal cultivation, which could explain the finding of cereal pollen in the sediment from pit F.1112.

The cereal-sized Lolium temulentum (darnel) constituting most of the big weeds in the carpological assemblage suggests particular care in removing it from the processed crop by hand-picking. Although darnel is not poisonous itself, it is very easily attacked by the endophytic fungus Endoconidium temulentum, which is thought to be the source of the pyrrolizidine alkaloids (Eliáš et al. 2010). The toxicity manifests in the form of hallucinations and severe damage to the nervous system (if ingested in larger quantities) and has been known to man for millennia, being documented also in the Bible (Eliáš et al. 2010).

The second most common weed in the assemblage is Phalaris sp., small-sized and separated from the crop through fine sieving. According to Riehl (2010), it may represent a weed of free-threshing wheat. Although the different species are said not to be differentiated based on their caryopses (Baldini 1993), two different morphologies were identified in the assemblage: one more elongated than the other. After the comparison with pictures of modern samples present on the CISEH (2001–2018) online database of the University of Georgia and modern samples from the Herbarium of the Sapienza University of Rome (RO), the less elongated morphology has been identified as that of Phalaris cf. minor, which grows in wastelands, fallows, edges and cultivated fields (Baldini 1993). The portrayed specimen of Phalaris minor (Walters and Southwick [date unknown]) appeared to be noticeably less elongated than the specimens of other Phalaris spp.

Human impact on the environment

The overall weed assemblage shows similarities with the ones from the Iron Age sites of Monte Polizzo and Selinunte in Western Sicily (Stika et al. 2008). L. temulentum/remotum and Phalaris sp. predominate there as well, accompanied by other common weeds of crop fields such as Avena sp. and Bromus sp., which also grow in dry disturbed places.

Arable weeds in the F.1112 assemblage also include Ammi majus L., Ranunculus sp. and Raphanus raphanistrum L. (Schepers 2014). Other wild plants that are very common in sites prone to anthropogenic disturbance are Calendula cf. arvensis, Chenopodium album L., Chenopodiastrum murale, Echium plantagineum, Heliotropium europaeum, Malva nicaeensis All., Malva sp., Medicago sp., Silene cf. vulgaris, Sherardia arvensis, Veronica sp. and Portulaca oleracea L., the latter possibly cultivated also as a vegetable (Bosi et al. 2009; Pasta et al. 2020). Urtica membranacea and U. urens are also present, being typically found on nutrient-rich and disturbed ground, but occurring also as weeds of woody crops (van Zeist et al. 2001).

The identification of the Calendula cf. arvensis (field marigold) achene was complex, as each capitulum of this genus “can produce 2 to 6 different morphologies of achenes, and in some species, specimens presenting different combinations of achene morphs can co-exist” (Gonçalves et al. 2018). This means that different species can present achenes with the same morphology, while different morphologies may occur in the same species and on one single plant. Concerning the morphology of Calendula achenes, Pignatti et al. (2017–2019) state that those of C. arvensis are bent, sometimes locked up in a ring, with dorsal spines, which are generally absent in C. maritima Guss., a perennial marigold endemic to the coastal habitats of western Sicily (Pasta et al. 2017).

More surprising, although in low concentrations, was the retrieval of a variety of Cyperaceae and Polygonaceae, including Eleocharis palustris (L.) Roem. & Schult. and Persicaria cf. amphibia (L.) Delarbre. Their find seems to confirm the presence of humid environments with permanent freshwater or subject to extremely short periods of drying up, perhaps corresponding to the fresh-water springs found on the island (Di Mauro et al. 2011).

More data about the surrounding environment can be inferred from palynology. The dominance of non-arboreal taxa indicates an open environment, with little to no forest cover (Montecchi and Mercuri 2018). Complex anthropogenic activities are testified, among others, by Asteroideae, Cerealia, Poaceae, Ranunculaceae and Rumex (Mercuri et al. 2013). Other indicators of human activity are Cichorioideae, indicator of mesic meadows and pastures, Urtica, a nitrophilous plant, and Plantago, which indicates trampled areas (Florenzano et al. 2015; Mercuri et al. 2013). Nonetheless, Plantago could refer to P. macrorhiza Poir., a plantain that grows on coastal salty meadows and is not linked to the presence of grazing or trampling.

NPPs also contribute to building an image of the past environment. Glomus is a mycorrhizal fungus that forms symbiotic relationships with plant roots and is present in all samples, with concentrations as high as 76.5% (FL I-III). Pseudoschizaea, presumably the schizocarp of a green alga living in the soil, also occurs in all samples. They are both considered as indicators of erosion in lacustrine records (Sadori 2018). Here they can be interpreted as evidence of soil micro-organisms. In particular, Pseudoschizaea is related to depositional conditions that occur in correspondence to seasonal desiccation, indicating a direct link between its presence and erosion processes (Sadori 2018). The third most abundant NPPs are Tecaphora basidiospores that occur on higher plants (Fabaceae and Convolvulaceae; van Geel et al. 1980). Finally, Turbellaria are cocoons of whirl-worms indicating a high concentration of nutrients (van Geel et al. 1983), while Rotifera (found only in SU 1112) are near-microscopic animals, whose eggs are usually found in moist environments (van Geel 2001).

Another category widely represented in the carpological assemblage is that of fruits, which was probably not related to crop processing and/or storage, but perhaps to winemaking. The most abundant is V. vinifera (grapevine), which was also retrieved during the preliminary survey in 2017. Grapevine holds a specific importance in the Phoenician world, as it is believed that Phoenicians, along with Greeks, were responsible for the spread of various grapevine cultivars across the Mediterranean (Ucchesu et al. 2015). It is interesting to notice the presence of Vitis pollen in the two bottom filling layers of F.1112, reaching a concentration of 8.3% in filling layer VI. As is seen for cereals, Vitis pollen grains travel over short distances (Sabato et al. 2015), suggesting local cultivation of grapevine.

Punica granatum (pomegranate), retrieved in pit F.1112 in the form of six exocarp fragments, is also believed to have been brought to the Mediterranean basin by Phoenicians (Nigro and Spagnoli 2018). Pomegranate is not very common in archaeobotanical assemblages due to seeds being eaten and the endocarp being more exposed to deterioration. From a chronological point of view, the retrieval of pomegranate at Motya represents the oldest such find in Sicily. Although in small concentrations, P. granatum was also found in, among other places, the Iron Age sites of Concepción and Núñez Méndez in the area of Huelva (9th–8th centuries bc; Pérez-Jordà et al. 2017), Phoenician Tell el-Burak in Lebanon (8th–4th centuries bc; Orendi and Deckers 2018), Iron Age Ashkelon on Israel’s southern shoreline (7th century bc; Weiss and Kislev 2004) and nuraghe S’Urachi in Sardinia (7th–6th centuries bc; Pérez-Jordà et al. 2020).

Another fruit found in pit F.1112 is Ficus carica (fig), known to be part of the standard Mediterranean assemblage (Alonso Martinez 2005). It is amongst the oldest fruit trees cultivated in the Mediterranean, where it can also grow spontaneously (Pignatti et al. 2017–2019). Due to each “fruit” containing hundreds of achenes, as well as them being ingested and preserved in faeces through mineralization, figs are often overrepresented in archaeobotanical assemblages (Alonso Martinez 2005). Taking into consideration that most of the achenes retrieved were preserved by charring, overrepresentation of fig does not take place in the F.1112 assemblage at Motya.

A Pinus pinea (Mediterranean stone pine) nutshell fragment and a bract were also found in filling layer VI. Furthermore, the Pinus pollen identified in the studied sediment presents the morphology of P. pinea/pinaster. The percentage (ca. 10% in FL I-III) achieved by this Mediterranean pine suggests a local presence. The origin and spread of the Mediterranean stone pine (P. pinea) are the subject of unresolved debates. These difficulties in assessing the origin of this plant are mostly due to its extremely low genetic variability (Pinzauti et al. 2012). P. pinea is considered native to the entire Mediterranean basin, with studies showing that it was present in the Iberian Peninsula for several tens of thousands of years (Martínez and Montero 2004), being found in caves inhabited by Neanderthals (Mutke et al. 2019). It survived in Spain the LGM (last glacial maximum), being found in the Nerja Cave near Malaga during the Upper Palaeolithic dating back between ca. 22000 and 15500 years bc (Carrión et al. 2008). It is nonetheless probable that Phoenicians played a key role in its spread (Mutke et al. 2019). Pinus pinea/pinaster wood was found in a Bronze Age context in Sardinia (Sabato et al. 2015), a region where native populations of Pinus pinaster still occur (Caudullo et al. 2017). Archaeobotanical remains of the Mediterranean stone pine have in fact been found in numerous Phoenician-Punic sites, such as Santa Giusta in Sardinia (Sabato et al. 2019), where it was believed to be added for meat preservation and spicing (Ucchesu et al. 2017), 6th–5th century bc layers on the Balearic Islands (Pérez-Jordà et al. 2018) and in Punic Carthage (van Zeist et al. 2001), where the find is considered as testifying to the contacts with the western Mediterranean. As far as we know, the finding of Motya is the oldest Italian site, corroborating the hypothesis that Phoenicians played a major role in the spread of Pinus pinea. The presence of P. pinea/pinaster pollen also suggests local growing of Mediterranean coastal pines. The two Mediterranean coastal pines cannot be distinguished on the basis of pollen morphology and none currently grow wild in Western Sicily (Caudullo et al. 2017).

Anthracological remains make up a big part of the archaeobotanical assemblage of pit F.1112. This is to be expected in such a context, as wood was burned as fuel, producing charcoal (Fuller et al. 2014). Most of the wood taxa retrieved are typical of the Mediterranean maquis and show a correspondence with the present-day flora of the Sicilian coastline, between the infra- and the thermo-Mediterranean, referred to the Quercetea ilicis class and the Pistacio-Rhamnetalia alaterni order, with a prevalence of Pistacia lentiscus and Olea europaea (Gianguzzi et al. 2016). Despite the pollen spectra being characterized by a prevalence of non-arboreal pollen, Pistacia and Quercus ilex type are both present. What appears to be surprising is the lack of Olea in the palynological evidence, while it is common among anthracological remains. This is surprising as demographic studies carried out by Nigro (2017) suggested that a relevant portion of the islet was used for olive tree cultivation. Nonetheless, a study carried out by Florenzano et al. (2017) on modern pollen from olive groves in Tuscany and Basilicata shows that, while Olea pollen percentages from samples collected inside the groves were as high as 58%, the ones collected at a distance of 500 m or more from the grove were not higher than 1.6%. Furthermore, even some of the samples collected from inside the groves showed rather low Olea pollen concentrations of ca. 10%. Therefore, the lack of olive pollen does not necessarily indicate the absence of olive trees on the islet. There could have been an olive grove in Motya, possibly on the other side of the island. This is supported by the evidence from the submerged causeway (Terranova et al. 2009). Finally, overrepresentations of local plants in pollen assemblages coming from human settlements are common, possibly causing the Olea pollen concentration in the sediment from Motya to be even lower.

Nonetheless, O. europaea represents a relevant part of the anthracological assemblage. While in the votive pit at Motya (Moricca et al. 2020b) it represented almost 80% of the assemblage, in pit F.1112 it does not prevail over other taxa. Considering the slow growth rate of such trees (Valamoti et al. 2018), it is rational to believe that olive timber was used scrupulously, preferring taxa with a faster growth rate. O. europaea is much more likely to have been cultivated for its fruits (Valamoti et al. 2018). It is interesting to notice that only two olive endocarps were retrieved from the analysed sediment. One of the reasons may be the use of olives for oil production. Oil is present both in the soft outer part (mesocarp) and in the stone, and is obtained through pressing, requiring the application of a stronger force to extract it from the latter (Cappers et al. 2013). Olive pressing at Motya is thought to have been performed in tanks and low basins connected to food preparation (Nigro 2007). It is possible that the remains of olive pressing (pomace) were discarded near the basins, or perhaps pomace was used as a source of fuel in other areas of the site, as reported for various Mediterranean sites between 3100 bc and the 6th century ad (Rowan 2015).

Although scarce, Chamaerops humilis (Mediterranean dwarf palm) was also found. Its wood was identified using the key provided by Thomas (2013). Motya falls within the present-day natural distribution range of C. humilis, which covers the central and western Mediterranean (Moricca et al. 2020a). Archaeobotanical evidence of C. humilis is uncommon, nonetheless its macro- and micro-remains are present in records from Italy and Spain (Moricca et al. 2020a).

Overall, no significant changes were observed in the bulk of the carpological and anthracological assemblages of the different depositional layers. This may be due to the disposal pit F.1112 being used for a limited amount of time, as common for this type of archaeological feature. Nonetheless, some less abundant wood taxa, such as Cupressus sempervirens (cypress), Fraxinus sp., Juniperus sp., Rosaceae Maloideae and Rosoideae were present only in one or two of them. These data should not be disregarded as, for example, C. sempervirens (cypress) is believed to be native to the Middle East and to have arrived in the Western Mediterranean thanks to Phoenicians and Etruscans (Pignatti et al. 2017–2019), despite some evidence showing that it may be actually native to Italy (Bagnoli et al. 2009). A mineralized remain of cypress was in fact also found in pit F.7057 in the area of the Temple of Cappiddazzu at Motya (Moricca et al. 2020b). Rosaceae Maloideae probably belong to Pyrus sp. or Sorbus sp., as Malus sp. prefers cooler climates and it is intolerant of drought.

Another unusual finding is represented by Juglans (walnut) pollen in SU 1112. Its current distribution is the result of human action that favoured its spread from east to west along the Mediterranean (Pérez-Obiol and Sadori 2007). It appears in Sardinian pollen spectra from at least 5,300 bp (Di Rita and Melis 2013) and its endocarps are present in the Phoenician-Punic site of Santa Giusta (Sabato et al. 2019). In Sicily, Juglans pollen appears in the 8th–7th century bc (Sadori 2013). Furthermore, walnut charcoal is also present in the votive pit in the temple of Cappiddazzu at Motya (Moricca et al. 2020b).

The finding of juniper in Phoenician Motya is interesting. Despite the data deriving from a single context, juniper is found both in the pollen and in the anthracological evidence. In order to assess its frequency, it would be necessary to take into consideration other contexts, gathering data from structural charcoals. Nowadays, the closest populations of Juniperus growing in Sicily, referred to Juniperus turbinata Guss., are located near Alcamo or near Siculiana, both located ca. 100 km from Motya (Gianguzzi et al. 2012). Charcoals of Juniperus sp. have also been found in a prehistoric cave in Favignana dating ~ 14.2 ka cal bp (Poggiali et al. 2012). The presence of juniper in western Sicily is also confirmed by the Gorgo Basso pollen spectra, where it appears with low values and discontinuously throughout last 10,000 years (Tinner et al. 2009). Currently, we can advance two hypotheses: juniper was either present in small quantities along the coasts of the Stagnone, or it grew on the islet itself. Its complete disappearance in present-day western Sicily could be due to burning. Juniper, in fact, recovers less easily than other plants of the maquis, like heaths and lentisks, which easily re-sprout after fire. Similar considerations can explain the present lack of Erica arborea, common in the Motya assemblage, whose nearest populations are nowadays located at Scorace, Angimbé and Zingaro nature reserve (i.e. at least 40 km far from Motya; Gianguzzi et al. 2012). As E. arborea requires a deeper, more acid and more developed soil than E. multiflora, its disappearance is likely ascribable to either land over-exploitation, aridification or a combination of both.

Finally, charcoal fragments belonging to the Pinus sylvestris-montana group (as reported by Greguss 1955), which includes montane species of pine, were found. In fact, the only Sicilian pine sharing the same anatomical characteristics of these remains, i.e. Pinus nigra Arnold ssp. laricio Palib. ex Maire, only grows on Mount Etna, located nearly 250 km from Motya. Pine timber is known to have been used for ship-building (Giachi et al. 2003); therefore it is possible that the retrieved piece of charcoal derived from a ship that had been built elsewhere.

Conclusions

The present multidisciplinary study provides precious information regarding the Phoenicians’ daily life at Motya – their earliest colony in Sicily (Thucydides 1881) – and their plant use, highlighting the importance of combining the study of macro- and micro-remains.

First, the presence of cereals, numerous weeds of different sizes and chaff made it possible to hypothesize that most of crop processing was carried out on site, after storage. The presence of cereal pollen in the studied samples supports the hypothesis that threshing was carried out next to the analysed deposit, as well as the archaeological hypothesis that cultivation occurred on site.

Secondly, the study provides evidence for local human diet. Although hulled and naked wheat and barley were found, a clear preference for naked wheat and hulled barley was recorded. This is in accordance with data from other Iron Age sites in western Sicily, namely Monte Polizzo and Selinunte (Stika 2004; Stika et al. 2008; Stika and Heiss 2013). It is probable that naked wheat was used for human consumption, while hulled barley was used as fodder. The finding of naked barley is surprising, as it underwent a rapid decline in all Europe during the Iron Age. Other than cereals, the diet was comprised of a wide variety of pulses (including lentils, peas and faba beans) and fruits, among which grapevine prevailed.

Pollen data indicate a strongly disturbed Mediterranean landscape with little to no forest cover. Complex anthropogenic activities are testified by the presence of cultivated trees and cereals among others, with Asteroideae, Cichorioideae and Urtica as the main synanthropic taxa.

Anthracological data help to complete the local environmental picture, with findings of Pistacia lentiscus, Olea europaea, Erica multiflora, E. arborea, Juniperus sp. and evergreen oaks. Only the first three currently grow on the islet, while E. arborea and Juniperus species grow no closer than 40 km and 100 km from Motya, respectively. Olea, with abundant charcoals, and still cultivated on present day Motya, is surprisingly lacking in the pollen diagram. The high charcoal percentage of evergreen oaks, plants today absent on Motya and currently showing a scattered occurrence along the coast facing the Marsala Lagoon, indicates that it was a wood-type of preference. Finally, the retrieved fragments of the “montane type” of pine probably issue from imported material. Remarkably, the finding of Pinus pinea represents the oldest for this species in the Holocene in the central Mediterranean.

Based on the evidence reported in the present paper, it is possible to compare Motya’s past environment with the present one. The present-day lack of Juniper sp. could be due to burning, as this plant is a less efficient re-sprouter after fire than other woody species of the maquis, like heaths and lentisk. Similar considerations could explain the present lack of E. arborea, whose disappearance is likely ascribable to either land over-exploitation, aridification or a combination of both processes.

References

Alonso Martinez N (2005) Agriculture and food from the Roman to the Islamic Period in the North-East of the Iberian Peninsula: archaeobotanical studies in the city of Lleida (Catalonia, Spain). Veget Hist Archaeobot 14:341–361

Andersen ST (1979) Identification of wild grass and cereal pollen. Dan Geol Unders Årbog 1978:69–92

Badura M, Rzeźnicka E, Wicenciak U, Waliszewski T (2016) Plant remains from Jiyeh/Porphyreon, Lebanon (seasons 2009–2014): preliminary results of archaeobotanical analysis and implications for future research. Pol Archaeol Mediterr 25:487–510

Bagnoli F, Vendramin GG, Buonamici A et al (2009) Is Cupressus sempervirens native in Italy? An answer from genetic and palaeobotanical data. Mol Ecol 18:2,276–2,286

Baldini RM (1993) The genus Phalaris L. (Gramineae) in Italy. Webbia 47:1–53

Bates J, Singh RN, Petrie CA (2017) Exploring Indus crop processing: combining phytolith and macrobotanical analyses to consider the organisation of agriculture in northwest India c. 3200–1500 BC. Veget Hist Archaeobot 26:25–41

Beug HJ (2004) Leitfaden der Pollenbestimmung für Mitteleuropa und angrenzende Gebiete. Friedrich Pfeil, München

Bosi G, Guarrera PM, Rinaldi R, Bandini Mazzanti M (2009) Ethnobotany of purslane (Portulaca oleracea L.) in Italy and morfobiometric analyses of seeds from archaeological sites of Emilia Romagna (Northern Italy). In: Morel JP, Mercuri AM (eds) Plants and Culture: seeds of the cultural heritage of Europe. Bari, Edipuglia, pp 129–139

Bouby L, Boissinot P, Marinval P (2011) Never mind the bottle. Archaeobotanical evidence of beer-brewing in Mediterranean France and the consumption of alcoholic beverages during the 5th century BC. Hum Ecol 39:351–360

Bouchaud C, Jacquat C, Martinoli D (2017) Landscape use and fruit cultivation in Petra (Jordan) from Early Nabataean to Byzantine times (2nd century BC–5th century AD). Veget Hist Archaeobot 26:223–244

Brullo S, Gianguzzi L, La Mantia A, Siracusa G (2008) La classe Quercetea ilicis in Sicilia (The class Quercetea ilicis in Sicily). Boll Acc Gioenia Sci Nat 41:1–80 ((in Italian))

Buosi C, Del Rio M, Orrù P, Pittau P, Scanu GG, Solinas E (2017) Sea level changes and past vegetation in the Punic period (5th-4th century BC): archaeological, geomorphological and palaeobotanical indicators (South Sardinia-West Mediterranean Sea). Quat Int 439:141–157

Buxó R (2008) The agricultural consequences of colonial contacts on the Iberian Peninsula in the first millennium B.C. Veget Hist Archaeobot 17:145–154

Calò C, Henne PD, Curry B et al (2012) Spatio-temporal patterns of Holocene environmental change in southern Sicily. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 323–325:110–122

Cambini A (1967) Micrografia comparata dei legni del genere Quercus (Comparative micrographs of woods of the genus Quercus). In: Cambini A (ed) Riconoscimento microscopico del legno delle querce italiane. Consiglio nazionale delle ricerche, Roma (in Italian)

Cappers RTJ, Bekker RM (2013) A manual for the identification of plant seeds and fruits, vol 23. Barkhuis, Groningen

Cappers R, Heinrich F, Kaaijk S, Fantone F, Darnell J, Manassa C (2013) Barley revisited: Production of barley bread in Umm Mawagir (Kharga Oasis, Egypt). In: Accetta K, Fellinger R, Gonçalves PL, Musselwhite S, van Pelt WP (eds) Current Research in Egyptology 2013: proceedings of the Fourteenth Annual Symposium. Oxbow Books, Oxford, pp 49–63

Capuani S, Stagno V, Missori M, Sadori L, Longo S (2020) High-resolution multiparametric MRI of contemporary and waterlogged archaeological wood. Magn Reson Chem 58:860–869

Carrión JS, Finlayson C, Fernández S et al (2008) A coastal reservoir of biodiversity for Upper Pleistocene human populations: palaeoecological investigations in Gorham’s Cave (Gibraltar) in the context of the Iberian Peninsula. Quat Sci Rev 27:2,118–2,135

Castiglioni E (2008) I resti botanici (The botanical remains). In: Maniscalco L (ed) Il santuario dei Palici. Un centro di culto nella valle dei Margi (The sanctuary of the Palici. A center of cult in the valley of the Margi). Collana d’Area. Quaderno 11. Regione Siciliana, Palermo, pp 365–386 (in Italian)

Caudullo G, Welk E, San-Miguel-Ayanz J (2017) Chorological maps for the main European woody species. Data Brief 12:662–666

Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Help (CISEH) (2001–2018) University of Georgia, Tifton. https://www.invasive.org. Accessed 26 March 2020

Di Martino A, Perrone C (1970) Flora delle isole dello Stagnone (Marsala) (Flora of the islands of Stagnone (Marsala). Isola Grande. Lav Ist Bot Giard Colon 24:109–166 ((in Italian))

Di Mauro D, Alfonsi L, Sapia V, Nigro L, Marchetti M (2011) First field magnetometer investigation at the Phoenician Island of Mozia (Trapani), northwestern Sicily: preliminary results. Archaeol Prospect 18:215–222

Di Rita F, Melis RT (2013) The cultural landscape near the ancient city of Tharros (central West Sardinia): vegetation changes and human impact. J Archaeol Sci 40:4,271–4,282

Eliáš PJ, Hajnalová M, Eliášová M (2010) Historical and current distribution of segetal weed Lolium temulentum L. in Slovakia. Hacquetia 9:151–159

Euro+Med PlantBase - the information resource for Euro-Mediterranean plant diversity (2006) Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum Berlin-Dahlem, Berlin. http://ww2.bgbm.org/EuroPlusMed/. Accessed 6 April 2020

Faegri K, Iversen J (1989) In: Faegri K, Kaland PE, Krzywinski K (eds) Textbook of pollen analysis, 4th edn. Wiley, Chichester

Florenzano A, Marignani M, Rosati L, Fascetti S, Mercuri AM (2015) Are Cichorieae an indicator of open habitats and pastoralism in current and past vegetation studies? Plant Biosystems 149:154–165

Florenzano A, Mercuri AM, Rinaldi R et al (2017) The representativeness of Olea pollen from olive groves and the Late Holocene landscape reconstruction in central Mediterranean. Front Earth Sci 5(85):1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2017.00085

Fuller DQ, Stevens C, McClatchie M (2014) Routine activities, tertiary refuse and labor organization: social inferences from everyday archaeobotany. In: Madella M, Lancelotti C, Savar M (eds) Ancient plants and people. Contemporary trends in archaeobotany. University of Arizona Press, Tucson, pp 174–217

Giachi G, Lazzeri S, Mariotti Lippi M, Macchioni N, Paci S (2003) The wood of “C” and “F” Roman ships found in the ancient harbour of Pisa (Tuscany, Italy): the utilisation of different timbers and the probable geographical area which supplied them. J Cult Herit 4:269–283

Gianguzzi L, Ilardi V, Caldarella O, Cusimano D, Cuttonaro P, Romano S (2012) Phytosociological characterization of the Juniperus phoenicea L. subsp. turbinata (Guss.) Nyman formations in the Italo-Tyrrhenian Province (Mediterranean Region). Plant Sociol 49:3–28

Gianguzzi L, Papini F, Cusimano D (2016) Phytosociological survey vegetation map of Sicily (Mediterranean region). J Maps 12:845–851

Gonçalves AC, Castro S, Paiva J, Santos C, Silveira P (2018) Taxonomic revision of the genus Calendula (Asteraceae) in the Iberian Peninsula and the Balearic Islands. Phytotaxa 352. Magnolia Press, Auckland

Grau Almero E (2011) Charcoal analysis from Lixus (Larache, Morocco). SAGVNTVM Extra 11:107–108

Greguss P (1955) Identification of living gymnosperms on the basis of xylotomy. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest

Grimm EC (1991) TILIA and TILIAGRAPH software. Illinois State Museum, Springfield

Guarino R, Pasta S (2017) Botanical excursions in Central and Western Sicily. Field Guide for the 60th IAVS Symposium (Palermo, 20–24 June 2017). Palermo University Press, Palermo

Jacomet S (2006) Identification of cereal remains from archaeological sites, 2nd edn. Basel University, Basel, IPAS

Jones G (1990) The application of present-day cereal processing studies to charred archaeobotanical remains. Circaea 6:91–96

Jones G (1998) Distinguishing food from fodder in the archaeobotanical record. Environ Archaeol 1:95–98

Lister DL, Jones MK (2013) Is naked barley an eastern or a western crop? The combined evidence of archaeobotany and genetics. Veget Hist Archaeobot 22:439–446

López-Ruiz C, Doak BR (2019). The Oxford Handbook of the Phoenician and Punic Mediterranean. Oxford Handbooks.

Martínez F, Montero G (2004) The Pinus pinea L. woodlands along the coast of South-western Spain: data for a new geobotanical interpretation. Plant Ecol. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:VEGE.0000048087.73092.6a

Mercuri AM, Allevato E, Arobba D et al (2015) Pollen and macroremains from Holocene archaeological sites: a dataset for the understanding of the bio-cultural diversity of the Italian landscape. Rev Palaeobot Palynol 218:250–266

Mercuri AM, Bandini Mazzanti M, Florenzano A, Montecchi MC, Rattighieri E (2013) Olea, Juglans and Castanea: the OJC group as pollen evidence of the development of human-induced environments in the Italian peninsula. Quat Int 303:24–42

Montecchi MC, Mercuri AM (2018) When palynology meets classical archaeology: the Roman and medieval landscapes at the Villa del Casale di Piazza Armerina, UNESCO site in Sicily. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 10:743–757

Moricca C, Nigro L, Gallo E, Sadori L (2020a) The dwarf palm tree of the king: a Nannorrhops ritchiana in the 24th-23rd century BC palace of Jericho. Plant Biosyst. https://doi.org/10.1080/11263504.2020.1785967

Moricca C, Nigro L, Spagnoli F, Sabatini S, Sadori L (2020) Plant assemblage of the Phoenician sacrificial pit by the Temple of Melqart/Herakles (Motya, Sicily, Italy). Environ Archeol. https://doi.org/10.1080/14614103.2020.1852757

Mutke S, Vendramin GG, Fady B, Bagnoli F, González-Martínez SC (2019) Molecular and Quantitative Genetics of Stone Pine (Pinus pinea). In: Nandwani D (ed) Genetic Diversity in Horticultural Plants. Springer, Cham, pp 61–84

Neef R, Cappers RTJ, Bekker RM (2012) Digital atlas of economic plants in archaeology, vol 17. Barkhuis, Groningen

Nesbitt M (2016) Identification guide for Near Eastern grass seeds. Routledge, London

Nigro L (2007) Mozia-XII: Zona D, la “Casa del sacello domestico”, il “Basamento meridionale” e il Sondaggio stratigrafico I. Rapporto preliminare delle campagne di scavi XXIII e XXIV (2003–2004) (Motya XII: Area D, the house of the domestic shrine, the southern base and stratigraphic survey I. Preliminary report of the 23rd and 24th excavation campaigns (2003–2004). Missione Archeologica a Mozia, Roma (in Italian)

Nigro L (2016) Mozia nella preistoria e le rotte levantine: i prodromi della colonizzazione fenicia tra secondo e primo millennio a.C. nei recenti scavi della Sapienza (Prehistoric Motya and the Levantine routes: the harbingers of Phoenician colonization between the second and first millennium BC in the recent excavations of Sapienza). Scienze dell’Antichità 22:339–362 ((in Italian))

Nigro L (2017) Motya IV: building up a West Phoenician colony. In: Nigro L, Spagnoli F (eds) Landing on Motya. The earliest Phoenician settlement of the 8th century BC and the creation of a West Phoenician cultural identity in the excavations of Sapienza University of Rome – 2012–2016. Missione Archeologica a Mozia, Roma

Nigro L, Spagnoli F (2018) Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) from Motya and its deepest oriental roots. Vicino Oriente 22:49–90

Nigro L, Antonetti S, Rocco G, Spagnoli F (2002) Zona D. Le pendici occidentali dell’Acropoli (D Area. The western slopes of the Acropolis). In: Nigro L (ed) Mozia - X. Rapporto preliminare della XII campagna di scavi - 2002 condotta congiuntamente con il Servizio Beni Archeologici della Soprintendenza Regionale per i Beni Culturali e Ambientali di Trapani (Motya X. Preliminary report of the 12th excavation campaign - 2002 conducted jointly with the Archaeological Heritage Service of the Regional Superintendence for Cultural and Environmental Heritage of Trapani). Quaderni di Archeologia Fenicio-Punica I. Missione Archeologica a Mozia, Roma, pp 141–354 (in Italian)

Noti R, van Leeuwen JFN, Colombaroli D et al (2009) Mid- and late-Holocene vegetation and fire history at Biviere di Gela, a coastal lake in southern Sicily, Italy. Veget Hist Archaeobot 18:371–387

Orendi A, Deckers K (2018) Agricultural resources on the coastal plain of Sidon during the Late Iron Age: archaeobotanical investigations at Phoenician Tell el-Burak, Lebanon. Veget Hist Archaeobot 27:717–736

Pasta S (2004) La conservazione delle emergenze botaniche nell’area costiera siciliana: il caso della R.N.O. “Isole dello Stagnone di Marsala” (Trapani, Sicilia Occidentale) (The conservation of the botanical heritage of a Sicilian coastal area: the case of the nature reserve “Isole dello Stagnone di Marsala”). Naturalista Siciliano 28:243–263 ((in Italian))

Pasta S, La Rosa A, Garfì G et al (2020) An updated checklist of the Sicilian native edible plants: preserving the traditional ecological knowledge of century-old agro-pastoral landscapes. Front Plant Sci 11:388. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.00388

Pasta S, Garfì G, Carimi F, Marcenò C (2017) Human disturbance, habitat degradation and niche shift: the case of the endemic Calendula maritima Guss. (W Sicily, Italy). Rend Fis Acc Lincei 28:415–424. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12210-017-0611-5

Peña-Chocarro L, Pérez-Jordà G (2019) Garden plants in medieval Iberia: the archaeobotanical evidence. Early Mediev Eur 27:374–393

Pérez-Jordà G, Hurley J, Ramis D, van Dommelen P (2020) Iron Age botanical remains from nuraghe S’Urachi. Antiquity, Sardinia. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2020.33

Pérez-Jordà G, Peña-Chocarro L, Fernández MG, Rodríguez JCV (2017) The beginnings of fruit tree cultivation in the Iberian Peninsula: plant remains from the city of Huelva (southern Spain). Veget Hist Archaeobot 26:527–538

Pérez-Jordà G, Peña-Chocarro L, Picornell-Gelabert L, Marco YC (2018) Agriculture between the third and first millennium BC in the Balearic Islands: the archaeobotanical data. Veget Hist Archaeobot 27:253–265

Pérez-Obiol R, Sadori L (2007) Similarities and dissimilarities, synchronisms and diachronisms in the Holocene vegetation history of the Balearic Islands and Sicily. Veget Hist Archaeobot 16:259–265

Pignatti S, Guarino R, La Rosa M (2017–2019) Flora d’Italia, 2nd edn. Edagricole - Edizioni Agricole di New Business Media, Bologna

Pinzauti F, Sebastiani F, Budde KB, Fady B, González-Martínez SC, Vendramin GG (2012) Nuclear microsatellites for Pinus pinea (Pinaceae), a genetically depauperate tree, and their transferability to P. halepensis. Am J Bot 99:e362–e365

Poggiali F, Martini F, Buonincontri M, Di Pasquale G (2012) Charcoal data from Oriente cave (Favignana island, Sicily). Abstract book of the AIQUA Congress, ‘The transition from natural to anthropogenic-dominated. Environmental change in Italy and the surroundings regions since the Neolithic - Session Environment, Climate and Human impact: The archaeological evidence’. AIQUA – Associazione Italiana per lo Studio del Quaternario, Firenze

Reed K (2016) Archaeobotanical analysis of Bronze Age Feudvar. In: Kroll HJ, Reed K (eds) Die Archäobotanik: Feudvar III. Würzburg University Press, Würzburg, pp 197–297

Reille M (1992–1998) Pollen et spores d’Europe et d’Afrique du Nord. Laboratoire de botanique historique et palynologie, Marseille

Riehl S (2010) Plant production in a changing environment: The archaeobotanical remains from Tell Mozan. In: Deckers K, Doll M, Pfälzner P, Riehl S (eds) Development of the environment, subsistence and settlement of the city of Urkeš and its region. Studien zur Urbanisierung Nordmesopotaniens Serie A 3. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden, pp 13–158

Rowan E (2015) Olive oil pressing waste as a fuel source in antiquity. Am J Archaeol 119:465–482

Sabato D, Masi A, Pepe C et al (2015) Archaeobotanical analysis of a Bronze Age well from Sardinia: a wealth of knowledge. Plant Biosyst 149:205–215

Sabato D, Peña-Chocarro L, Ucchesu M et al (2019) New insights about economic plants during the 6th-2nd centuries BC in Sardinia, Italy. Veget Hist Archaeobot 28:9–16

Sadori L (2013) Southern Europe. In: Elias SA (ed) The encyclopedia of quaternary science, vol 4. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 179–188

Sadori L (2018) The Lateglacial and Holocene vegetation and climate history of Lago di Mezzano (central Italy). Quat Sci Rev 202:30–44

Sadori L, Narcisi B (2001) The Postglacial record of environmental history from Lago di Pergusa, Sicily. Holocene 11:655–671

Sadori L, Ortu E, Peyron O et al (2013) The last 7 millennia of vegetation and climate changes at Lago di Pergusa (central Sicily, Italy). Clim Past 9:1,969–1,984

Schepers M (2014) Why sample ditches? In: Schepers M (ed) Reconstructing vegetation diversity in coastal landscapes. Advances in Archaeobotany 1. Barkhuis, Groningen, pp 109–122

Schweingruber FH (1990) Anatomy of European woods. Haupt, Bern

Scuderi L, Pasta S, Lo Cascio P (2007) Indagini sulla flora e sulla vegetazione delle isole minori dello Stagnone di Marsala (Investigations on the flora and the vegetation of the small islands of the Stagnone di Marsala). 102 Congresso Nazionale Società Botanica Italiana (Palermo, 26–29 settembre 2007), riassunti 312. Azienda Regionale Foreste Demaniali Reg. Sicilia, Palermo (in Italian)

Smit A (1973) A scanning electron microscopical study of the pollen morphology in the genus Quercus. Acta Bot Neerl 22:655–665

Stevens CJ (2003) An investigation of agricultural consumption and production models for prehistoric and Roman Britain. Environ Archaeol 8:61–76

Stika H-P (2004) Preliminary Report on the Archaeobotanical Remains (2003 Season) from Monte Polizzo (sixth-fourth Century BC and twelfth Century AD) and Salemi (fifth and fourth Century BC) in Sicily. In: Morris I, Jackman T, Garnand B, Blake E, Tusa S (eds) Stanford University Excavations on the Acropolis of Monte Polizzo, Sicily, IV: Preliminary Reports on the 2003 Season. Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 49. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, pp 197–279

Stika H-P, Heiss AG (2013) Seeds from the fire: charred plant remains from excavations in Sweden, Denmark, Hungary and Sicily. In: Bergerbrant S, Sabatini S (eds) Counterpoint: essays in archaeology and heritage studies in honour of professor Kristian Kristiansen. Archaeopress, Oxford, pp 77–86

Stika H-P, Heiss AG, Zach B (2008) Plant remains from the early Iron Age in western Sicily: differences in subsistence strategies of Greek and Elymian sites. Veget Hist Archaeobot 17:139–148

Stockmarr J (1971) Tablets with spores used in absolute pollen analysis. Pollen Spores 13:615–621

Terranova F, Accorsi CA, Bandini Mazzanti M et al (2009) Indagini archeopalinologiche in Sicilia a Taormina, Piazza Armerina e Mozia (Archaeopalynological analyses in Sicily in Taormina, Piazza Armerina and Motya). In: Centro Regionale per la Progettazione ed il Restauro e per le Scienze Naturali ed Applicate ai Beni Culturali (ed) Atti del III Convegno Internazionale ‘La materia e i segni della storia’. Regione Siciliana, Assessorato dei Beni Culturali ed Ambientali e della Pubblica Istruzione, Dipartimento Beni Culturali ed Ambientali ed Educazione Permanente, Palermo, pp 184–194

Thomas R (2013) Anatomy of the endemic palms of the Near and Middle East: archaeobotanical perspectives. Rev Ethnoécol 4:1–15

Thucydides (1881) History of the Peloponnesian War, Book VI, chapter 2, section 6. Translated by B. Jowett. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Tinner W, van Leeuwen JF, Colombaroli D et al (2009) Holocene environmental and climatic changes at Gorgo Basso, a coastal lake in southern Sicily, Italy. Quat Sci Rev 28:1,498–1,510

Ucchesu M, Orrù M, Grillo O et al (2015) Earliest evidence of a primitive cultivar of Vitis vinifera L. during the Bronze Age in Sardinia (Italy). Veget Hist Archaeobot 24:587–600

Ucchesu M, Sarigu M, Del Vais C et al (2017) First finds of Prunus domestica L. in Italy from the Phoenician and Punic periods (6th-2nd centuries BC). Veget Hist Archaeobot 26:539–549

Valamoti SM, Gkatzogia E, Ntinou M (2018) Did Greek colonisation bring olive growing to the north? An integrated archaeobotanical investigation of the spread of Olea europaea in Greece from the 7th to the 1st millennium BC. Veget Hist Archaeobot 27:177–195

Van Geel B (2001) Non-pollen palynomorphs. In: Smol JP, Birks HJB, Last WM (eds) Tracking environmental change using lake sediments terrestrial, algal, and siliceous indicators, vol 3. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, pp 99–119

Van Geel B, Bohncke SJP, Dee H (1980) A palaeoecological study of an upper Late Glacial and Holocene sequence from “De Borchert”, The Netherlands. Rev Palaeobot Palynol 31:367–448

Van Geel B, Hallewas DP, Pals JP (1983) A late Holocene deposit under the Westfriese Zeedijk near Enkhuizen (Prov. of Noord-Holland, The Netherlands): palaeoecological and archaeological aspects. Rev Palaeobot Palynol 38:269–335

Van Zeist W, Bakker-Heeres JAH (1982) Archaeobotanical studies in the Levant: I. Neolithic sites in the Damascus basin: Aswad, Ghoraife. Ramad Palaeohistoria 24:165–256

Van Zeist W, Bottema S, van der Veen M (2001) Diet and vegetation at ancient Carthage: the archaeobotanical evidence. Groningen Institute of Archaeology, Groningen

Walters D, Southwick C (date unknown) Table Grape Weed Disseminule ID 5466558. USDA APHIS PPQ. https://www.invasive.org/browse/detail.cfm?imgnum=5466558. Accessed 25 March 2020

Weiss E, Kislev ME (2004) Plant remains as indicators for economic activity: a case study from Iron Age Ashkelon. J Archeol Sci 31:1–13

Acknowledgements

The Brain network and database—http://brainplants.successoterra.net/—are acknowledged for the archaeological sites mentioned in the paper. The authors would like to thank Katerina Kouli from the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens with her help with pollen treatment and analysis. A heartfelt acknowledgement goes to René T.J. Cappers, who helped with the identification of weeds. This research work is a product of the PRIN 2017 Project: “People of the Middle Sea. Innovation and integration in ancient Mediterranean (1600-500 bc)” [A.3 Flora antiqua], grant number 2017EYZ727. It was also supported by a PhD grant of the Department of Earth Sciences, Sapienza University of Rome. The authors are also grateful to the anonymous reviewers, whose constructive comments have allowed us to improve the form and content of the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Roma La Sapienza within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by W. Tinner.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moricca, C., Nigro, L., Masci, L. et al. Cultural landscape and plant use at the Phoenician site of Motya (Western Sicily, Italy) inferred from a disposal pit. Veget Hist Archaeobot 30, 815–829 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00334-021-00834-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00334-021-00834-1