Abstract

Extensive research has been conducted into the antecedents and consequences of workplace envy, but there have been limited meta-analytic reviews. This meta-analysis draws on social comparison theory to examine studies of envy in the workplace and develop a comprehensive model of the antecedents and consequences of workplace envy. We reconcile the divergent findings in the literature by building a model of three types of workplace envy that distinguishes between episodic, dispositional, and general envy. The results suggest that individual differences (e.g., narcissism, neuroticism), organizational contexts (e.g., competition, position), and social desirability are predictors of workplace envy. They also reveal that workplace envy is related to organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs), negative behaviors (e.g., ostracism, social undermining), negative emotions, organizational perceptions (i.e., engagement, satisfaction), turnover intentions, and moral disengagement. We test the moderating roles of envy types, measurement approaches, and causal directions. The results reveal that these moderators have little differences, and that some variables (e.g., self-esteem, fairness) may be both antecedents and consequences of workplace envy. Finally, we suggest that future research into workplace envy should investigate contextual predictors and moderators of the social comparison process that triggers envy. This meta-analysis can serve as a foundation for future research into workplace envy.

Similar content being viewed by others

“Every time a friend succeeds, a part of me dies.” Gore Vidal, American writer.

Envy is a painful emotion aroused by another’s good fortune (Tai et al., 2012). Like other strong emotions, envy activates neurocognitive mechanisms (Takahashi et al., 2009). Envy has been extensively studied in the psychology literature, and studies of envy in the workplace have increased in number (Koopman et al., 2020; Puranik et al., 2019; Thiel et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2018). These studies suggest that competitive work environments may often create envy.

Most of these studies investigate the outcomes from the perspective of the envious individuals who “desire what another has achieved or accomplished” (Sterling & Labianca, 2015, p. 297). Specifically, they explore the behavioral and perceptional outcomes for envious individuals. In terms of behavioral outcomes, envy can trigger an attempt to acquire or remove the envied other’s desirable features, leading to a complex set of processes that can determine whether envy facilitates productive or counterproductive behavior (Crusius et al., 2020; van de Ven et al., 2009). The compensatory behavioral responses of envy are targeted at the envied other, who may be ambivalently perceived as both an admired role model and a threatening competitor. As a painful emotion, envy in the workplace can lead to decreased job engagement and satisfaction (Lee et al., 2018; Sterling, 2013). Research focusing on the antecedents of workplace envy has identified the predictors of workplace envy, including personality differences (Cohen-Charash, 2000; Sun et al., 2020) and perceived leadership (Kim, 2006). The growing literature on the antecedents of workplace envy considers justice, social comparison (Hoogland, 2016; Koopman et al., 2020), and performance-based triggers (Kim & Glomb, 2014).

The antecedents and outcomes of workplace envy have been explained from different perspectives (Crusius et al., 2020; Ganegoda & Bordia, 2019; Puranik et al., 2019; Tai et al., 2012), but there are few holistic empirical analyses of envy. No consensus has been reached on the conceptualization of envy and its antecedents and outcomes, and the conclusions of previous studies are often contradictory (Cohen-Charash & Larson, 2016). No single conceptual model that encompasses the different types of envy (e.g., dispositional envy, episodic envy, and general envy) has been developed. Thus, this study advances the field by developing a model that includes these different conceptualizations.

Previous studies focus on either the antecedents or outcomes as subsets of workplace envy, and a broad conceptual perspective is lacking. To address this gap, we apply social comparison theory to envy research. Envy is a product of upward social comparison (Smith, 2000), as it occurs when individuals upwardly compare themselves to others who they perceive to be better off.

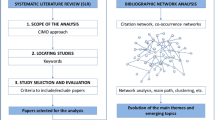

As the literature on workplace envy is extensive and complex, a quantitative review is required. First, we review the conceptualizations of envy and build a model of three types of workplace envy that differentiates episodic, dispositional, and general envy. Second, we build a holistic framework for understanding the antecedents and outcomes of workplace envy based on Festinger’s social comparison theory (Festinger, 1954), which suggests that comparing oneself with others is a facet of human nature. Recent research has significantly modified and extended Festinger’s hypothesis (Buunk & Gibbons, 2007; Gibbons & Buunk, 1999; Greenberg et al., 2007; Smith, 2000; Suls et al., 2002), contributing to the understanding of how workplace envy is operationalized. We first examine the theoretical perspectives in detail and then identify the primary nomological network of the antecedents of workplace envy: individual differences (e.g., self-esteem), organizational environments (e.g., competition), and social desirability. We also examine envy outcomes in the form of behaviors (e.g., core performance), emotions (e.g., anger, depression), organizational perceptions (e.g., satisfaction), and social dysfunction (e.g., moral disengagement). In our meta-analysis, we identify 20 antecedents and 18 outcomes of workplace envy based on social comparison theory (see Fig. 1). Finally, we identify the boundary conditions by treating envy types (i.e., episodic, dispositional, and general envy), measurement approaches (i.e., unitary or dual), and causal directions (variables as antecedents or outcomes) as moderators of the relationships between workplace envy and its antecedents and consequences.

This meta-analytic review of workplace envy makes three contributions to the literature. First, we reconcile previous findings by building a model of three types of workplace envy, and further define the nature of envy (Cohen-Charash & Larson, 2016; Crusius et al., 2020). Second, drawing on social comparison theory, we propose a holistic conceptual framework for understanding the antecedents and outcomes of envy, thus addressing the lack of explanation or justification for these effects in studies of organizational behavior. Finally, we suggest that future research should further develop a comprehensive study of different types of workplace envy and its implications, investigate the underlying mechanisms, boundary conditions, and positive aspects of workplace envy, and reassess the possibility of reverse causality (i.e., the effects of envy on self-esteem).

Theory and hypotheses

Model of three types of workplace envy

Emotions can manifest in two forms: as a disposition or a state. Envy is no exception. To clarify and classify concepts of envy used in research, this study develops a model of workplace envy that encompasses both individuals and situations (see Fig. 2). Episodic envy (i.e., situation-based, within-person) is triggered by an unpleasant upward comparison with a similar other that identifies a lack “in a domain central to one’s self-concept” (Cohen-Charash & Mueller, 2007, p. 666). Dispositional envy (i.e., trait-based, between-person) is a relatively stable interpersonal tendency, in which individuals “respond to upward status comparison with behavior directed at leveling the difference toward these superior others” (Lange, Blatz, & Crusius, 2018, p. 425). General envy is regarded as “a pattern of thoughts, emotions, and behaviors that results from the perceived loss of social standing in response to another obtaining outcomes that are personally desired” (Vecchio, 2005, p. 69), which is the type of envy most commonly examined in the literature (Duffy et al., 2012; Thompson, Glaso, & Martinsen, 2016). Thus, it is appropriate to argue that a model of workplace envy should include episodic envy, dispositional envy, and general envy. The common characteristic of these three types of envy is that they are invoked through the process of social comparison and have affective (pain), cognitive (comparison, evaluation), and behavioral components (threat-oriented and challenge-oriented) (Tai et al., 2012). These three types of envy also have distinct characteristics. Dispositional envy (trait-based or between-person envy) reflects individual differences in the extent to which individuals experience envy in the workplace. Episodic envy (situation-based or within-person envy) reflects transient feelings of envy. General envy simultaneously reflects the state and trait of envy, which may be pervasive and general in the workplace. Compared with dispositional envy, general envy is partly situation-based and more changeable. Episodic envy focuses on a specific event or comparison referent (i.e., a singular referent), whereas general envy has more than one comparison referent (i.e., multiple referents). General envy may last longer than episodic envy (Duffy et al., 2021). To explore how workplace envy operates within different types, we test the moderating effects of these distinct types of envy on the antecedents and outcomes of workplace envy. To develop our general hypotheses, workplace envy is conceptualized as “a homeostatic emotion characterized by pain at another’s good fortune that activates threat- and challenge-oriented action tendencies” in the workplace (Tai et al., 2012, p. 110).

The social comparison model of workplace envy

The conceptual foundation for our workplace envy model is social comparison theory or, more appropriately, social comparison theories (Brown et al., 2007; Festinger, 1954; Gerber, 2018; Gerber et al., 2018). Social comparison theory has continually developed since it was initially introduced by Festinger in 1954, but all of the variants share the assumption that individuals tend to compare their abilities or opinions to others, particularly under uncertain conditions. Although the objectives and approaches of these different comparison theories vary, they all share the assumption that individuals naturally engage in social comparison processes. In our workplace envy framework, we focus on who makes the comparisons (individual differences), how they compare things (organizational contexts), what the effects are (reaction responses), the role of conformity to social norms (e.g., social desirability), and responses to the comparisons (e.g., behaviors, perceptions, emotions).

Personal characteristics directly determine whether individuals participate in the process of social comparison after self-evaluation (Tesser, 1988). Wheeler (2000) regards neuroticism as an emotional need for others to be worse off than oneself, while self-esteem consists of the emotional assets required for self-protection and confidence. Individual characteristics (e.g., personal traits) also affect the perception of threats. When individuals feel that their self-worth is threatened, social comparison leads to negative self-evaluation because it leads them to believe they cannot achieve the superior performance of the individual they are comparing themselves to, who is perceived as having particular advantages (e.g., success in a valued domain).

Organizational contexts involve uncertainty and competition (Brown et al., 2007). Comparisons with others in the workplace may raise individuals’ awareness of their lack of something possessed by a comparison referent (Festinger, 1954). Responding to this discrepancy triggers self-regulation, which refers to “a process by which individuals strive for a desired internal state by evaluating discrepancies between actual states and reference values” (Koopman et al., 2020, p. 860). When circumstances fall below individuals’ expectations, they attempt to regulate the resources, information, and relationships in the environment as a form of control (Johnson et al., 2006). From the perspective of self-regulation, organizations may stimulate individuals’ awareness of discrepancies between themselves and others and provide a context for the social-functional role of envy. The discrepancies are typically highlighted by organizational characteristics that can promote envy, such as competition, fairness, and leader–member exchange (LMX). In addition, experiencing envy has a social-functional effect on organizational perceptions (e.g., satisfaction, engagement, turnover intentions) and behavior (e.g., abusive supervision).

The selective accessibility model suggests that there are two responses to social comparison, assimilation and contrast. Assimilation is characterized by obtaining the same status as the superior referent, and contrast is characterized by obtaining a clear recognition of the self (Mussweiler, 2003; Mussweiler & Strack, 2000). After individuals compare themselves to another and identify a discrepancy, they may subsequently gain the advantage of the comparison target (i.e., assimilation) or remain deprived of this advantage (i.e., contrast). These two remedial reactions reduce the discrepancy resulting from upward comparison (Lee & Duffy, 2019).

Social comparison theory hinges on the notion of conformity to social norms (Litt et al., 2012). Individuals must satisfy the expectations of society and others by obeying social norms, but may disengage from or contradict social norms to alleviate a discrepancy resulting from social comparison. Thus, social norms provide standards to obey or to contradict when individuals become aware of discrepancies between themselves and comparison referents.

Social comparison is directional, i.e., it can take the form of either upward comparison with those who are better off or downward comparison with those who are worse off. In this meta-analysis, we focus on upward comparison, as it effectively represents the direction of the emotion of envy. We draw on social comparison theory in our meta-analytic review and propose a conceptual model of workplace envy to tests its antecedents and outcomes, as described in our hypotheses.

Antecedents

Personality

Narcissism is characterized by “an inflated sense of self that is reflected in feelings of superiority, arrogant behavior, and a need for constant attention and admiration” (Bogart et al., 2004, p. 36). It is a personality trait closely related to social comparison. Narcissistic individuals desire actual or symbolic superiority, and thus feel that they are entitled to more resources (Castiglione, 2010). They desire to be admired by others and strive for a sense of recognition from their surroundings (Robertson, 2014). They are also hypersensitive to threats and try to maintain a sense of superiority in upward comparison (Bogart et al., 2004). High levels of narcissism can therefore increase the tendency for envy.

Neuroticism is characterized by angry hostility, depression, impulsiveness, vulnerability, and anxiety, and can predict emotional instability. Studies show that neuroticism leads to greater participation in the comparison process and elevates the unpleasant emotion of envy (Buunk & Gibbons, 2007). Neurotic individuals are irrational when evaluating their self-worth in an upward comparison (Howard et al., 2020). They are prone to perceive more uncertainty and easily become anxious about their superiority, thus engendering more envy.

Thus, we propose the following hypothesis.

-

Hypothesis 1 (a) Narcissism and (b) neuroticism are positively associated with workplace envy.

Affectivity

Affectivity describes individuals’ psychological states. Individuals with a positive affect feel enthusiastic, active, and alert, whereas a negative affect involves the experience of aversive mood states (e.g., upset, fear, distress) (Watson et al., 1988). Numerous studies show that positive or negative affectivity is closely associated with social comparison and interaction (Dineen et al., 2017; Khan et al., 2014; Kim & Glomb, 2014). Individuals with positive affectivity are satisfied and experience pleasant emotions, whereas those with negative affectivity experience unpleasant emotions (Watson et al., 1988). Positive affectivity helps individuals evaluate their own ability and potential, suggesting that individuals with high levels of positive affectivity are aware of their own potential and perceive more possibility of success when making upward comparisons, thus decreasing the likelihood of workplace envy (Scott et al., 2015). Negative affectivity may increase perceptions of discrepancy and lead individuals to indulge in negative emotions, increasing their workplace envy. Thus, we make the following hypothesis.

-

Hypothesis 2 (a) Positive affectivity is negatively associated with workplace envy, whereas (b) negative affectivity is positively associated with workplace envy.

Self-perceptions

Three separate categories of self-perception are considered in this meta-analysis: (1) core self-evaluations, which represent a broad range of self-perceptions, (2) self-efficacy, which focuses on individuals’ evaluations of their abilities, and (3) self-esteem, which reflects an individual’s sense of worth. Core self-evaluations (CSEs) are characterized by “self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and nonneuroticism,” and represent bottom-line evaluations of one’s worthiness, competence, and capabilities (Judge et al., 1998, p. 17). CSEs also reflect the perception of self-uncertainty through individuals’ evaluations of their own abilities or capabilities. Those with low CSEs are likely to experience uncertainty in the upward comparison process and the emotion of envy may emerge as a compensatory mechanism. Individuals with high CSEs possess more realistic and reasonable judgements of threats and challenges (Tai et al., 2012) and this can inhibit envy. Thus, low CSEs can trigger more workplace envy.

Self-efficacy is characterized by “a generative capability in which component cognitive, social, and behavioral skills must be organized into integrated courses of action to serve innumerable purposes” (Bandura, 1982, p. 122). Individuals with low self-efficacy are likely to perceive themselves as inferior in the upward comparison process, as they perceive that they lack capability and are vulnerable, which can produce negative emotions such as envy. Thus, low self-efficacy is likely to trigger workplace envy.

Self-esteem is a measure of individuals’ evaluation of their own worth (Cohen-Charash, 2000). Individuals with high self-esteem are more confident and experience positive emotions. They can protect themselves against threatening comparisons in the upward comparison process. Psychologists generally suggest that people with low self-esteem need stronger defenses than those with high self-esteem when they compare themselves unfavorably with others. Thus, CSE, self-efficacy, and self-esteem can help individuals to develop the ability to resist negative emotions or threatening events, thus leading to less workplace envy. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis.

-

Hypothesis 3 (a) CSE, (b) self-efficacy, and (c) self-esteem are negatively associated with workplace envy.

Other individual differences

Admiration can be defined as a pleasing feeling of appreciation for the accomplishments of another person and is a combination of a “liking for” and being “inspired by” and “pleased for” the target (Johar, 2011, p. 20). Admiration can lead to the internalization and emulation of the superior referent as part of the effort to achieve self-growth. It is also linked to the desire for self-improvement, which can in turn reduce envy. Psychologists generally conclude that envy is a stronger negative emotion than admiration in upward social comparison (van de Ven, 2017; van de Ven et al., 2011). An individual who admires the comparison referent does not perceive the referent as superior (Cohen-Charash, 2009). In the process of social comparison with a superior referent, those who admire the target may admit the discrepancy but suppress the negative emotion, and are thus less likely to engage in workplace envy.

Studies show that low levels of perceived control engender more workplace envy (Smith, 2000). Perceived control gives individuals the opportunity to bridge discrepancies using a self-regulation mechanism (Koopman et al., 2020). Perceived control reduces the uncertainty of upward comparison and enhances an individual’s confidence in his or her ability to rebalance the position of inferiority (Brown et al., 2007). Thus, perceived control reduces workplace envy.

Social comparison involves the comparison of the self with referents, and can motivate self-evaluation, self-improvement, and self-enhancement (Gibbons & Buunk, 1999). Social comparison is a fundamental element of human cognition (Lange & Crusius, 2015). Individuals with high tendencies for social comparison are more likely to experience negative emotions (e.g., envy, resentment) (Smith, 2000). Social comparison reminds individuals of the advantages possessed by other people, which leads to envy (Smith & Kim, 2007). Specifically, envy arises when social comparisons trigger awareness of one’s poor performance in areas that personally matter. Social comparison stimulates inferences about the self and assessments of one’s ability (Smith & Kim, 2007). The tangible consequences of social comparisons (e.g., superior relative performance, relative LMX) and their effects on self-evaluation, logically, should trigger envy (Tai et al., 2012). Thus, we expect a greater tendency toward social comparison to increase the occurrence of workplace envy.

-

Hypothesis 4 (a) Admiration and (b) perceived control are negatively associated with workplace envy, whereas (c) social comparison is positively associated with workplace envy.

Organizational perceptions

Comparisons can be the result of “structured competition for rewards, recognition, or status” (Fletcher & Nusbaum, 2010, p. 107). Competition can lead to more uncertainty, for example uncertainty about resources. If an individual feels that a comparison referent may take resources, she or he may feel more envious (Ng, 2017; Reh et al., 2018). Competition can also be threatening, as, for example, individuals may fear that the comparison referent could replace them (Reh et al., 2018). Thus, competition may undermine the process of self-regulation. When individuals identify a discrepancy, it may upset them and make them feel envious. Thus, competition is positively related to workplace envy.

Fairness is a judgement reached through comparison with others and involves “evaluations about justice rule adherence” (Koopman et al., 2020, p. 864). In the process of social comparison, fairness positively predicts social exchange quality and positive affect (Colquitt et al., 2013), while a lack of fairness predicts a sense of unappreciation and disconnection, which creates an awareness of potential threats from a discrepancy (Koopman et al., 2020), resulting in envy. Thus, a lack of fairness triggers workplace envy.

-

Hypothesis 5 (a) Competition is positively associated with workplace envy, and (b) fairness is negatively associated with workplace envy.

Leadership

LMX is defined as “the quality of the exchange relationship between leader and subordinate” (Schriesheim et al., 1999, p. 77). Employees who experience high-quality LMX are likely to form trusting relationships, gain access to resources, and enjoy job satisfaction and favorable leader evaluations. Conversely, those who experience low-quality LMX are likely to resent coworkers who they perceive as enjoying more benefits than themselves, thus reducing the sense of balance in the workplace (Kim et al., 2010). High-quality LMX can moderate the effects of unfavorable comparisons with superior others, therefore reducing envy (Matta & Van Dyne, 2020). Thus, we propose the following hypothesis.

-

Hypothesis 6 LMX is negatively associated with workplace envy, such that individuals experiencing low-quality LMX are more likely to experience workplace envy.

Contexts

Organizational size and relative position can shape the competitiveness of an environment. The larger an organization, the more resources it has. An environment with adequate information and resources gives individuals the confidence to deal with uncertainty and thus reduces envy. Similarly, a high position provides individuals with a feeling of superiority and adequate resources, and thus they will perceive the organizational climate to be less competitive than those in subordinate positions (Thompson et al., 2016). Conversely, smaller organizations and a low position produce a more competitive climate, which may induce more envy (Reh et al., 2018).

Social desirability requires individuals to behave according to prevailing cultural norms and to satisfy societal expectations. Social desirability suppresses the occurrence of workplace envy for two reasons. First, socially desirable biases encourage people to hide the self-demeaning nature of envy (Cohen-Charash & Mueller, 2007) and to obey normative sanctions against expressing envy (Gibbons & Buunk, 1999). Envy is a covert and socially undesirable emotion that is considered a sin in most cultures (Smith & Kim, 2007), metaphorically referred to as “the green-eyed monster.” Individuals who express envy are likely to be regarded as “narrow-minded.” To convey a positive image, people with a high degree of social desirability tend to repress their envy (Cohen-Charash, 2000). Second, social desirability sets a high value on emotional stability (Ones et al., 1996). Envy is a strong emotion, which does not support emotional stability. Thus, social desirability suppresses envy. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis.

-

Hypothesis 7 (a) Organizational size, (b) position level, and (c) social desirability are negatively related to workplace envy.

Outcomes

Behaviors

Social comparison theory suggests that the consequences of comparison are assimilation and contrast. Although researchers have studied behavioral outcomes from many perspectives (e.g., Lee & Duffy, 2019; Puranik et al., 2019; Tai et al., 2012), they generally suggest that envy involves either attempting to improve oneself (i.e., assimilation, or leveling-up) or harming the envied (i.e., contrast, or leveling-down) (Crusius et al., 2020; Koopman et al., 2020; Lee & Duffy, 2019; Mao et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2018).

Envy puts employees into a negative psychological state, which affects their interpersonal interactions. The envious may feel inferior and less confident at work, which affects their in-role behaviors (i.e., core performance) and organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs). In-role behaviors are behaviors that are associated with employees’ work for an organization. OCBs represent extra-role behaviors that spontaneously and effectively promote organizational function, including “helping behavior, sportsmanship, organizational loyalty, organizational compliance, individual initiative, civic virtue, and self-development” (Podsakoff et al., 2000, p. 516). Negative upward comparison results in hostility and depression in the envious, thus reducing both their core performance and OCBs.

In their attempts to match the comparison referents’ level, the envious try to enhance their own superiority through help seeking, learning behaviors, and other forms of improvement that allow them to shift closer to the comparison target. Help seeking and learning behaviors provided by the superior referent can help the envious to narrow the discrepancy and can serve as a coordinating function for improving their relationship with the superior referent (Lee & Duffy, 2019). The envious individuals also conduct other forms of improvement, such as self-improvement (Yu et al., 2018), increased work effort (Sterling, 2013), and working harder (Khan et al., 2017), to manage their envy.

To contrast or reduce the discrepancy with the comparison referent, the envious may conduct negative workplace behaviors to distance themselves from the target, or to compensate for their own inferiority by conducting harmful behaviors (Greco et al., 2019). These behaviors can include counterproductive work behaviors (CWBs), defined as “voluntary behavior that violates significant organizational norms and in so doing threatens the well-being of an organization, its members, or both” (Bennett & Robinson, 2000, p.349); abusive supervision, defined as “subordinates’ perceptions of the extent to which supervisors engage in the sustained display of hostile verbal and nonverbal behaviors, excluding physical contact” (Tepper, 2000, p. 178); ostracism, defined as the perception of ignorance or exclusion by others (Ferris et al., 2008); social undermining, a type of antisocial behavior consisting of “intentional behavior and behavior designed to weaken its target gradually or by degrees” (Duffy et al., 2012, p. 643); and incivility, defined as “low-intensity deviant behavior with ambiguous intent to harm the target, in violation of workplace norms for mutual respect” (Blau & Andersson, 2005, p. 596). Thus, we propose the following hypotheses.

-

Hypothesis 8 Workplace envy is negatively related to (a) core performance and (b) OCBs.

-

Hypothesis 9 Workplace envy is positively related to (a) help seeking, (b) learning behaviors, and (c) other forms of improvement.

-

Hypothesis 10 Workplace envy is positively related to (a) CWBs, (b) abusive supervision, (c) ostracism, (d) social undermining, (e) incivility, and (f) other forms of mistreatment.

Emotions

Emotional states can be positive or negative, as suggested by previous meta-analyses (Howard et al., 2020). Positive emotions are reduced when the envious experience unpleasant discrepancies between their expectations and perceived reality (Buunk et al., 2003). Upward comparison can evoke negative emotions in envious individuals, whose desire for superiority is thwarted by the envied other. Envy with sense of inferiority and frustration reduces positive emotions and increases negative emotions. Thus, we hypothesize the following.

-

Hypothesis 11 Workplace envy is negatively associated with (a) positive emotions, and positively associated with (b) negative emotions.

Organizational perceptions

In the upward comparison process, individuals experience negative emotions and stress (Greenberg et al., 2007), which harm their positive experience of the workplace. Thus, workplace envy created by social comparison processes reduces favorable perceptions of an organization, including identification, defined as a shared sense of self within an organization or group (Ashmore et al., 2004; Kim & Glomb, 2014); engagement, defined as the physical, cognitive, and emotional energy individuals devote to their work roles (Erdil & Muceldili, 2014; Kahn, 1990); and satisfaction, defined as an individual’s appraisal of their job or work experiences (Brown et al., 2007; Judge et al., 2005). Thus, we hypothesize the following.

-

Hypothesis 12 Workplace envy is negatively associated with (a) identification, (b) engagement, and (c) satisfaction.

Turnover

Researchers reveal that envious individuals are likely to withdraw physically or psychologically from their jobs or workplaces (De Clercq et al., 2018; Sterling, 2013; Vecchio, 2000). Brown et al. (2007) note that upward comparisons lead to reductions in job satisfaction and affective commitment, which directly influence turnover intentions. A decrease in satisfaction and commitment at work can mean that envious individuals are more likely to quit than unenvious individuals.

-

Hypothesis 13 Workplace envy is positively associated with turnover intentions.

Moral disengagement

Moral disengagement represents a dysfunction in an individual’s moral standards. It involves a series of cognitive justification mechanisms through which an individual can separate moral standards from behaviors (Bandura, 1999; Moore, 2015). Envy can trigger moral disengagement through three mechanisms: devaluing the envied, who are perceived as undeserving of the advantages they enjoy; reconstructing negative behavior by rationalizing it through moral justification; and obscuring or distorting the consequences of one’s behaviors (Duffy et al., 2012). For example, the envious may narrow the gap with the comparison referent by rationalizing unethical behavior as efficient and effective, thus justifying their disengagement from moral standards (Thiel et al., 2020). The envious are thus more likely to convince themselves that disengaging from moral standards will reduce the discrepancy and their envy. Thus, we make the following hypothesis.

-

Hypothesis 14 Workplace envy is positively associated with moral disengagement.

Methodological hypotheses and research questions

In previous studies of workplace envy, the demographic variables of gender, age, tenure, and education are generally controlled, as they may influence the relationships between workplace envy and its antecedents or outcomes (Ng, 2017). Although Gerber et al. (2018) concludes that social comparisons may vary with gender (e.g., women compare appearance, whereas men compare status), few studies have examined the relationship between gender and workplace envy. Women have been found to encounter more difficulty than men in the workplace, due to their roles as caregivers and mothers. Furthermore, disparities in job positions and being targets of mistreatment may result in perceptions of inferiority (Howard et al., 2020). Hence, women are more likely to experience negative emotions as an outcome of the comparison process than men. Moreover, studies show that women are more emotional and more experientially reactive to and sensitive to negative emotions than men (Gard & Kring, 2007). Taken together, we propose that women report more envy than men.

As for age, older people are more likely to hide their emotions including envy (Gerber, 2018), and are more capable of regulating their negative emotions than younger employees (Gross et al., 1997). In the comparison process, older individuals are likely to be covert about feelings of envy and to manage envy more effectively. Thus, we propose that older people report less envy than younger people.

Tenure represents the length of employment in an organization and individuals with longer tenure are familiar with their organizational surroundings (Zhang & Bednall, 2016), likely having resources and information about the organization. Specifically, individuals with longer tenure clearly have more information than the ones with shorter tenure, which makes it easier for them to obtain advantages in the organization. Hence, individuals with long tenure are less likely to indulge in workplace envy.

Educational background influences employees’ self-evaluations and corresponds to recognition and approval from one’s social milieu, resulting in different comparison referents. Education not only reflects social class and socioeconomic status but also reflects a cultural cleavage in which individuals with similar educational background are likely to form groups and adopt similar values (Leander et al., 2020). Education levels are negatively related to workplace envy because education leads to an understanding of the reasons for the discrepancies. Thus, we propose that education is negatively associated with workplace envy. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses.

-

Hypothesis 15 Gender is associated with workplace envy, as women exhibit more envy than men.

-

Hypothesis 16 (a) Age, (b) tenure, and (c) education are negatively associated with workplace envy.

Previous studies have developed multiple measures of envy. Although this has produced refined measures of specific types of envy, it is challenging to unify the phenomenological experiences captured by the numerous scales (Duffy et al., 2021; Lange, Blatz, & Crusius, 2018). Our model of workplace envy distinguishes three primary types of envy: dispositional, episodic, and general. For dispositional envy, we use the scales developed by Lange and Crusius (2015), Smith et al. (1999), and scales designed to measure individuals’ stable tendency to experience envy. For episodic envy, we use the scales developed by Cohen-Charash (2009), Mueller et al. (2007), van de Ven et al. (2009), and scales designed to assess state envy regardless of individuals’ trait or dispositional tendencies. For general envy, we use the scales developed by Schaubroeck and Lam (2004) and Vecchio’s (1995, Vecchio, 2000, Vecchio, 2005) scales that use trait and situation conditions to assess an individual’s envy of multiple referents. The relationships of envy with the antecedent and outcome variables may vary with the measurement method. We divide envy research into three subgroups according to the different envy measures to explore the moderating effects of these methodologies on the identified relationships.

Envy can be conceptualized and operationalized using either a unitary approach, in which it is regarded as a unitary construct that evokes different reactions, or a dual approach, which recognizes two subtypes or forms of envy (e.g., benign vs. malicious envy) that have different outcomes (Crusius et al., 2020; van de Ven et al., 2009). In this review, we take a dual approach and regard envy as taking different forms, such as general envy or specific envy (which can be benign or malicious) (Lange, Weidman, & Crusius, 2018; van de Ven, 2016). We also regard the distinction between dispositional and episodic envy as another dualism (Cohen-Charash, 2009; Lange & Crusius, 2015; van de Ven, 2016).

-

Research Question 1. Do the relationships between variables and envy differ depending on the type of envy (i.e., dispositional, episodic, or general)?

-

Research Question 2. Do the relationships between variables and envy differ depending on the measurement approach (i.e., unitary or dual)?

Some variables have been identified as antecedents of envy, but the evidence for the directionality of the relationships is not strong. According to Vecchio (2000), individuals with low self-esteem are sensitive to threats and are likely to have low self-value: thus, low self-esteem triggers envy. However, Yu et al. (2018) believe that envy signals a shortage of resources in important areas and represents a threat to self-esteem. Thus, self-esteem can be an antecedent or a consequence of envy. We therefore examine whether the relationship between workplace envy and self-esteem (fairness, competition, other forms of mistreatment, and engagement) is stronger when envy is measured as an antecedent or as an outcome of these constructs.

-

Research Question 3. Do the relationships between variables and envy differ when envy is measured before or after self-esteem, fairness, competition, other forms of mistreatment, and engagement are measured?

Method

To test our hypotheses and answer our research questions, we followed the meta-analysis reporting standards (MARS) and the suggestions of previous meta-analyses (American Psychological Association, 2020; Howard et al., 2020; Hunter & Schmidt, 2004).

Literature search

We conducted searches of the following databases in June 2020: Web of Science, EBSCO, PsycINFO, ProQuest Dissertations, and Theses Global. We used “envy” as the keyword. To identify all of the relevant published or unpublished empirical studies, we also searched the Academy of Management 2009–2020 Annual Meeting and Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology 2016–2020 Annual Conference programs and e-mails were sent to listed authors to request any unpublished or in-press manuscripts.

Inclusion criteria

Our inclusion criteria were as follows. First, we only included empirical studies that measured envy and provided quantitative statistics. We initially retrieved 1565 sources, including articles, dissertations, and unpublished data. We then narrowed the pool of the meta-analysis database by examining every study and excluding any research that was not relevant to workplaces or that lacked the necessary statistical information, such as the correlation coefficient (r) and sample size (N). This reduced the sample to 87 sources. After eliminating studies that did not provide the appropriate theoretical model or key variables for a relationship of interest, the sample was reduced to 51 sources, including 68 studies (N = 15,252). Two trained researchers coded these sources independently and reported the relevant information about the desired relationships. They rechecked the coding information of 10 sources at a time together, and the level of consistency was over 95%. The authors discussed any inconsistencies until consensus was reached.

Analyses

We calculated the results using Hunter and Schmidt’s (2004) meta-analytic procedure and R version 4.0.2. The results were used to report the random effects of the meta-analysis, following Hunter and Schmidt (2004). Table 1 reports the antecedents of envy and Table 2 reports the outcomes of envy. We used R and its meta packages of meta, metafor, and dmetar (Harrer et al., 2019; Viechtbauer, 2010).

We reported the effect size by estimating the sample size weighted mean observed correlation (\( \overline{r} \)), mean true score correlation (ρ), and 95% confidence interval, which excluded zero, and found that the corrected correlation was statistically significant. We also reported effect sizes, following previous meta-analyses. Other relevant statistics are provided in the tables (i.e., Tables 1 & 2).

We tested the moderating effects of workplace envy. First, we examined heterogeneity among the moderators by fitting a mixed-effects model and subgrouping the studies of each categorical moderator (see question 1 to question 3). Using the metafor package (Viechtbauer, 2010), we calculated the random effects separately for each subgroup, thus allowing for a comparison of the subgroups’ estimate r and confidence intervals after dummy-coding the subgroups. Second, we conducted a meta-regression to test for between group differences. The Q-statistics and p values indicated the significance of the moderators based on our fixed effects model. The estimate r also suggested the effect size when the variable defining each subgroup was used as the sole predictor. Q and p value reflected the moderating effects of the subgroup differences (Viechtbauer, 2010). Other parameter results can be provided upon request, such as the I2-statistic and T2-statistic. The I2-statistic represents the percentage of total variability due to heterogeneity, and the T2-statistic represents the estimated amount of residual heterogeneity. An I2-statistic of 25%, 50%, and 75% shows low, medium, and large heterogeneity, respectively (Borenstein et al., 2009; Viechtbauer, 2010). Furthermore, the I2-statistic “is less affected by the scaling of the measures or the number of included studies” (Burnette et al., 2013, p.14), which could further illustrate the heterogeneity of effect sizes. The results are briefly summarized below and the details of the moderating effects are provided in the Supplementary Material 3.

We also estimated publication bias using the following methods: fail-safe k, Egger’s test, the random-effects trim-and-fill method, and the weight-function model analysis (Vevea & Coburn, 2015; Vevea & Hedges, 1995; Vevea & Woods, 2005). We used three types of plots to visualize the results: a funnel plot to visualize the estimation of publication bias; an influence plot to identify outlier sources through a visual approach (Viechtbauer & Cheung, 2010); and a forest plot to strengthen the conclusions by visualizing each size effect. The results of these analyses are reported in the Supplementary Material 4. In particular, we have provided an online repository on the Center for Open Science (https://osf.io/kgcfw/), including two subdirectories -- analysis scripts and datasets with four supplementary materials and the whole primary data.

Results

Antecedents

Table 1 shows the meta-analysis estimates of the relationships between workplace envy and its antecedents following Hunter and Schmidt’s (2004) procedures. In terms of demographics, we found that gender (\( \overline{r} \) = − .02, ρ = −.02, 95% CI [−.06, .03]), age (\( \overline{r} \) = − .02, ρ = −.03, 95% CI [−.07, .02]), tenure (\( \overline{r} \) = .003, ρ = −.0001, 95% CI [−.06, .06]), and education (\( \overline{r} \) = .001, ρ = .002, 95% CI [−.04, .05]) had non-significant relationships with workplace envy, at 95% confidence intervals.

Workplace envy had positive and significant relationships with personality variables. Narcissism (\( \overline{r} \) = .09, ρ = .11, 95% CI [.03, .19]) and neuroticism (\( \overline{r} \) = .34, ρ = .43, 95% CI [.29, .56]) were both positively associated with workplace envy. Positive affectivity was not significantly related to workplace envy (\( \overline{r} \) = .04, ρ = .04, 95% CI [−.02, .10]), but negative affectivity was significantly related to workplace envy (\( \overline{r} \) = .04, ρ = .04, 95% CI [−.02, .10]). Workplace envy was negatively and significantly related to CSE (\( \overline{r} \) = − .20, ρ = −.23, 95% CI [−.31, −.15]), self-efficacy (\( \overline{r} \) = − .19, ρ = −.22, 95% CI [−.31, −.14]), and self-esteem (\( \overline{r} \) = − .23, ρ = −.27, 95% CI [−.47, −.08]), which are predictors of self-perception. Workplace envy was not significantly related to admiration (\( \overline{r} \) = − .03, ρ = −.03, 95% CI [−.16, .10]) or perceived control (\( \overline{r} \) = − .12, ρ = −.15, 95% CI [−.42, .12]), but was positively related to social comparison (\( \overline{r} \) = .26, ρ = .29, 95% CI [.08, .50]).

Competition was positively and significantly related to workplace envy (\( \overline{r} \) = .19, ρ = .21, 95% CI [.01, .41]), but fairness was not significantly related (\( \overline{r} \) = − .06, ρ = −.06, 95% CI [−.19, .06]), nor was LMX (\( \overline{r} \) = − .18, ρ = −.19, 95% CI [−.48, .10]). In terms of context, organizational size did not have a significant effect on workplace envy (\( \overline{r} \) = − .10, ρ = −.10, 95% CI [−.28, .07]), but position was negatively and significantly related (\( \overline{r} \) = − .09, ρ = −.09, 95% CI [−.16, .03]). Social desirability was negatively and significantly related to workplace envy (\( \overline{r} \) = − .23, ρ = −.27, 95% CI [−.44, −.11]). Thus, we identified 10 significant predictors of envy, as shown in Table 1: narcissism, neuroticism, negative affectivity, CSE, self-efficacy, self-esteem, social comparison, competition, position level, and social desirability.

Outcomes

Table 2 shows the meta-analysis estimates of the relationships between workplace envy and its outcomes, following Hunter and Schmidt’s (2004) procedures. Envy was negatively associated with OCBs (\( \overline{r} \) = − .21, ρ = −.24, 95% CI [−.39, −.09]), but did not significantly affect core performance (\( \overline{r} \) = .04, ρ = .05, 95% CI [−.03, .14]), help seeking (\( \overline{r} \) = − .03, ρ = −.02, 95% CI [−.25, .21]), learning behaviors (\( \overline{r} \) = − .08, ρ = −.08, 95% CI [−.36, .21]), or other forms of improvement (\( \overline{r} \) = .05, ρ = .06, 95% CI [−.03, .16]).

Workplace envy had a significant effect on all six negative behavior types. It had positive relationships with CWBs (\( \overline{r} \) = .33, ρ = .39, 95% CI [.26, .51]), abusive supervision (\( \overline{r} \) = .27, ρ = .31, 95% CI [.23, .39]), ostracism (\( \overline{r} \) = .37, ρ = .42, 95% CI [.34, .49]), social undermining (\( \overline{r} \) = .29, ρ = .31, 95% CI [.23, .40]), incivility (\( \overline{r} \) = .29, ρ = .35, 95% CI [.06, .63]), and other forms of mistreatment (\( \overline{r} \) = .28, ρ = .32, 95% CI [.24, .40]).

Workplace envy had a non-significant relationship with positive emotions (\( \overline{r} \) = − .04, ρ = −.04, 95% CI [−.23, .16]), but was positively and significantly associated with negative emotions (\( \overline{r} \) = .32, ρ = .36, 95% CI [.23, .49]). In terms of organizational perceptions, workplace envy was negatively associated with engagement (\( \overline{r} \) = − .14, ρ = −.16, 95% CI [−.30, −.01]) and satisfaction (\( \overline{r} \) = − .19, ρ = −.23, 95% CI [−.41, −.05]) but was not significantly related to identification (\( \overline{r} \) = − .03, ρ = −.04, 95% CI [−.24, .16]). It also had a positive effect on turnover intentions (\( \overline{r} \) = .24, ρ = .28, 95% CI [.14, .42]). In addition, workplace envy had a positive and significant relationship with moral disengagement (\( \overline{r} \) = .33, ρ = .38, 95% CI [.23, .52]). In total, 12 significant outcomes of envy were identified, as shown in Table 2: OCBs, CWBs, abusive supervision, ostracism, social undermining, incivility, other forms of mistreatment, negative emotions, engagement, satisfaction, turnover intentions, and moral disengagement.

Moderator analyses

To test whether the type of envy influenced the observed relationships, we distinguished three subgroups of studies according to the measures used: dispositional envy (Smith et al., 1999); episodic envy (Cohen-Charash, 2009; Cohen-Charash & Mueller, 2007); and general envy (Schaubroeck & Lam, 2004; Vecchio, 2000, 2005). We dummy-coded the types of envy to test their moderating effect. The only relationship moderated by envy type was the relationships between education and envy (Q = 5.39, p = .02). The subgroup analysis suggested that education was positively related to dispositional envy (r = .17, 95% CI [.02, .32]). Although the other relationships did not differ greatly according to whether the scale measured dispositional, episodic, or general envy, we report the significant relationships within each subgroup to offer a better understanding of the model. Within the subgroup of studies that measured episodic envy, five relationships had a significant effect: narcissism, neuroticism, CWBs, other forms of improvement, and other forms of mistreatment. Within the subgroup of studies that measured general envy, five outcomes had a significant effect size: OCBs, CWBs, other forms of mistreatment, negative emotions, and turnover intentions.

Furthermore, we tested the moderating effect of the measurement approach, which was coded as a unitary approach or a dual approach to envy. Two of the relationships were significantly different in the unitary and dual subgroups: engagement (Q = 5.69, p = .02) and satisfaction (Q = 16.64, p < .001). However, the limited number of variables affected and low values suggested that the measurement approach did not have a notable moderating effect.

We also tested whether the methodological design moderated the results. Specifically, we coded the studies according to when the antecedents and outcomes were measured: “measured before envy,” “measured after envy,” or “measured simultaneously or unknown” (see Table 3). Self-esteem did not have a significant effect when regarded as an antecedent or as an outcome but had a large effect when studied cross-sectionally (r = −.52, 95% CI [−1.01, −.01]). The effect of fairness was significantly different when it was studied as an antecedent (r = −.13, 95% CI [−.26, −.01]) and as an outcome (r = −.54, 95% CI [−.83, −.24]). Other forms of mistreatment had a non-significant relationship when studied as an antecedent (r = .28, 95% CI [−.25, .29]), but had a significant and positive effect when studied as an outcome (r = .26, 95% CI [.21, .46]) and cross-sectionally (r = .34, 95% CI [.20, .39]). The Q-statistic and the p value of fairness were significant (Q = 10.89, p < .001), suggesting that the methodological design does influence the results. The other results of the Q-statistics and p values were not significant, suggesting that the relationships did not differ when measured before envy, after envy, or simultaneously.

Publication bias analyses

Tables 4 and 5 show the results of the publication bias analyses. To reduce publication bias, we set the following requirements: the fail-safe k should be sufficiently large (N > 50); Egger’s test should be non-significant (p < .05); a random-effects trim-and-fill method with the missing mean (k > 3) should suggest that publication bias is present; and the weight-function model with specified p value intervals (p < .05 and p > .05) should not be significant. Among the antecedents, the fail-safe k was sufficiently large for all of the significant relationships with envy except for narcissism, CSE, self-efficacy, and position. The Egger’s test was not significant for all of the relationships with envy except for narcissism, suggesting that the observed effects were robust. Negative affectivity had a large number of implied missing studies (k > 3) and the weight-function model analyses were not statistically significant for any of the antecedents.

In terms of outcomes, the fail-safe k was sufficiently large for all of the significant relationships with envy except for abusive supervision and satisfaction. All of the Egger’s tests of the significant relationships were not significant. None of the outcome variables had a high number of implied missing studies (k > 3). The weight-function model analyses were not statistically significant for any of the outcome variables except for OCBs.

To further evaluate publication bias, we found that most of the small fail-safe k results (for narcissism, CSE, self-efficacy, position level, abusive supervision, satisfaction) or significant Egger’s tests (narcissism) appeared to be due to the small number of representative studies, which makes bias difficult to address. The weight-function result for the OCBs may suggest that publication bias is a likely problem. Through influential case diagnostics, we found one outlier and deleted it before reconducting the weight-function analysis. The likelihood ratio result was not statistically significant for OCBs, indicating that the outlier did not change the conclusion (Viechtbauer & Cheung, 2010). Although publication bias is therefore a concern, our inspection indicated that it was not a major issue in our findings.

Discussion

The results of this meta-analytic review are a model of workplace envy that includes three categories of envy: episodic envy (within-person), dispositional envy (between-person), and general envy. This meta-analytic model of workplace envy draws on social comparison theory, clarifies the controversies in the literature, and takes a holistic view of antecedents and consequences. For example, the results suggest that LMX and core performance have non-significant relationships with workplace envy, although the results in the literature are mixed. Our results also point to future directions for research on workplace envy. For example, considering the different effect sizes of the antecedents and consequences of workplace envy, researchers could explore the boundary conditions and mechanisms within the theoretical model given in Fig. 1.

The current meta-analytic review provides an initial step toward a unified understanding of workplace envy by aggregating the empirical research findings on workplace envy and its antecedents and consequences. The findings of previous studies of workplace envy are inconsistent, as can be seen in the review paper by Duffy et al. (2021), which lists all of the reported correlations between envy and job performance. The reported effect sizes of these correlations vary widely, with different studies finding positive correlations, negative correlations, and non-significant correlations. Thus, the correlation between envy and job performance remain ambiguous in previous studies. Our meta-analysis offers coherent evidence that workplace envy has a non-significant relationship with core performance. Contextual factors inappropriately used as proxies for underlying variables in the review by Duffy et al. (2021) should be investigated, as they are inconsistent with our findings that position is negatively related to workplace envy.

Our meta-analysis shows that workplace envy is not only influenced by individual differences but also by organizational contexts and social norms. Significant antecedents of workplace envy include narcissism, neuroticism, negative affectivity, CSE, self-efficacy, self-esteem, competition, social comparison, position, and social desirability. We assess the individual differences in gender, age, tenure, education, and positive affectivity, but none are significantly associated with workplace envy. The organizational contexts of fairness, LMX, and organizational size do not have a significant effect on workplace envy. Among the significant relationships, narcissism, negative affectivity, and organizational level have small effects; CSE, self-efficacy, self-esteem, competition, and social desirability have moderate effects; and neuroticism and social comparison have large effects. Rosenthal and Rosnow (2008) propose that correlations of 0.10, 0.24, and 0.37 should be considered small, moderate, and large effect sizes, respectively. They can be transformed from Cohen’s d into r. Though the benchmark levels, we can analyze the different effect sizes of predictors/outcomes and choose to test the mechanisms or boundary conditions of workplace envy. Furthermore, the findings implicitly reveal the main effect and the potential moderating effects in our model.

Workplace envy is also related to consequences such as individual behaviors, organizational perceptions, and moral dysfunction. Specifically, it is significantly related to OCBs, CWBs, abusive supervision, ostracism, social undermining, incivility, other forms of mistreatment, negative emotions, engagement, satisfaction, turnover intentions, and moral disengagement. Workplace envy does not have significant effects on the consequences of core performance, help seeking, learning behaviors, other forms of improvement, and identification. Workplace envy also has a major effect on CWBs, abusive supervision, ostracism, social undermining, incivility, other forms of mistreatment, negative emotions, and moral disengagement, a moderate effect on OCBs and turnover intentions, and a small effect on organizational perceptions (i.e., engagement and satisfaction).

To answer our research questions, we estimate the size effects by testing the moderating effects. The moderating effects of workplace envy do not differ in terms of envy types or measurement approaches. Dispositional envy, episodic envy, and general envy have no notable moderating effects. Researchers should further investigate these different envy types and conduct research using a model of three types of workplace envy, particularly to identify any significant relationships within each subgroup. Furthermore, the relationships between workplace envy and the studied variables do not differ greatly between studies that measure workplace envy with a unitary approach or with a dual approach. Although the logic of benign envy vs. malicious envy is reasonable, previous studies generally consider workplace envy as a unitary construct (Crusius et al., 2020; Tai et al., 2012). Future research should examine whether envy can be more successfully measured through a unitary or dual approach.

Past studies propose a clear theoretical division between the predictors and consequences of workplace envy, but the results of our meta-analytic review suggest that this division may not be as clear as hypothesized. In particular, reverse causality may be present (e.g., fairness is the outcome of envy), which has not generally been hypothesized. Fairness is typically regarded as an antecedent of workplace envy, but the relationship of fairness when measured after workplace envy is the same as the relationship of fairness when measured before workplace envy. This conclusion can also be applied to other forms of mistreatment. Thus, future research should consider examining reciprocal relationships.

Theoretical implications

We propose a model of workplace envy that (a) considers episodic (within-person, situation-based), dispositional (between-person, trait-based), and general envy and integrates personal and situational aspects, and (b) precisely distinguishes these types by testing them in the meta-analysis. The model of three types of workplace envy not only helps to clarify the plethora of conceptualizations of envy, which do not integrate personality (trait-based or between-based workplace envy) and emotion-based (state-based or within-based workplace envy) constructs, but also lays a foundation for understanding the precise mechanisms that drive the relationships between dispositional, episodic, and general envy and their antecedents and outcomes.

This meta-analytic review supports various theoretical perspectives that can be generally applied to the envy literature. We drew on social comparison theory to establish who engages in comparisons (individual differences), how they make the comparisons (organizational contexts), the effects (reaction responses), and the moderating role of conformity to social norms (e.g., social desirability), thus contributing to the literature on workplace emotion. We find that narcissism and neuroticism are predictors of workplace envy. The large effect of neuroticism suggests that emotional stability is important for preventing workplace envy. Individuals with negative affectivity are also prone to indulging in the negative emotion of envy. CSE, self-efficacy, and self-esteem significantly predict workplace envy, and thus social comparison may be based on the self-evaluation of abilities and opinions. Social comparison may therefore be an important predictor of envy in upward comparisons. The results of this meta-analysis also show that demographic variables (gender, age, tenure, and education) have non-significant relationships with envy, suggesting that envy occurs independently of these factors. For example, we find no differences in how female and male employees report the emotion of workplace envy.

Contextual factors also appear to be critical in explaining workplace envy. Although LMX is not related to envy in our meta-analysis, differing levels of LMX differentiation (Buengeler et al., 2021) may predict workplace envy. Individuals with poor relationships with their supervisors may not feel envy if the supervisor has a poor relationship with every member of the team. However, if the supervisor exhibits favoritism, this can trigger envy, as the differentiation in LMX may increase the discrepancy perceived in the social comparison. Fairness is related to workplace envy, which may provide insights into the role of perceived justice in self-regulation, and could lead to a reassessment of social justice comparisons (Koopman et al., 2020). Position represents status and power in an organization, and is an important predictor of envy (Fiske et al., 2002; Tai et al., 2012). High-level jobs offer individuals the advantages of resources and information, increasing the likelihood of workplace envy. Contextual factors may influence the self-regulation of awareness of discrepancies, and future research into the dynamic organizational contexts of self-regulation in terms of workplace envy should be conducted.

Workplace envy has significant effects on negative behaviors and emotions, suggesting that “bad is stronger than good” (Baumeister et al., 2001, p. 323). The non-significant effects of behavioral consequences on workplace envy suggest that self-improvement behavior (e.g., help seeking, learning behaviors) is a relatively ineffective way to mitigate workplace envy (Brown et al., 2007). These behavioral outcomes are aimed at improving one’s ability or acquiring superior knowledge, which suggests that researchers have acknowledged that envy may trigger positive behavior, and thus future studies could examine the potential positive effects of envy (Lee & Duffy, 2019). However, our results provide evidence that envious individuals not only conduct fewer OCBs but also harm those they envy, ostracizing them and engaging in more social undermining as they try to release the negative emotion of envy. Workplace envy also results in more negative emotions, turns organizational perceptions negative (i.e., engagement, satisfaction), and increases intention to move jobs. These results consistently suggest that envy is a complex psychological state involving not only feelings of psychological pain and hostility but also affective, cognitive, and behavioral components (Tai et al., 2012). Those who are envious take action to restore the discrepancy and are dissatisfied with their organizations. They may also lose enthusiasm for the organization and eventually withdraw from it. Thus, workplace envy may be negatively related to desirable personal and organizational consequences, but the potential positive consequences should be explored further (Koopman et al., 2020; Lee & Duffy, 2019).

We also find that workplace envy has relationships with social norms or personal ethical values. Social desirability can reduce workplace envy either in reality or symbolically, and workplace envy can facilitate moral disengagement. Envy is likely to be suppressed by social desirability, because individuals are likely to deny feeling envy, an undesirable and unpleasant emotion, and instead present fake sentiment on the outside. They will also find reasons to justify their envy-triggered behavior, and will try to compensate for the perceived discrepancy and overcome the feeling of inferiority through harmful behavior toward the envied. Thus, more research is required into the mediating mechanisms to establish the effects of social norms on workplace envy.

The results of our moderation test suggest that the direction of causality is uncertain. Some of the variables had the same relationships with envy, whether envy was measured before or after the variables. Hence, some of the proposed consequences could also be regarded as antecedents of workplace envy. For example, fairness can be conceptualized as both an antecedent and an outcome. Thus, causality should be further investigated to establish whether workplace envy should be conceptualized as an antecedent or a consequence.

Future research directions

This meta-analytic review indicates several opportunities for future research. The envy literature is fragmented and adopts various theoretical perspectives. Consequently, we offer two models (see Figs. 1 and 2) to investigate workplace envy. First, the model of three types of workplace envy offers a holistic framework based on personal traits and situations, and further research can elucidate the underlying mechanisms and boundary conditions of this model. For example, we speculate that episodic envy may influence episodic performance, while dispositional envy may affect typical performance (anxiety and performance, e.g., Cheng & McCarthy, 2018). Second, future research could explore the application of a social comparison framework to workplace envy, which supports previous findings and offers new areas of exploration, such as social norms. Researchers could advance the study of workplace envy under the social comparison framework and investigate social norms as standards of conduct.

The contextual antecedents of workplace envy can also be further investigated, particularly in terms of organizational comparison (Greenberg et al., 2007), which has been underexplored. More knowledge of the contextual antecedents may help organizations and leaders to develop harmonious workplaces that mitigate the negative consequences of workplace envy.

The positive aspects of workplace envy require further investigation (Koopman et al., 2020; Lee & Duffy, 2019), as the literature focuses on its negative consequences. The envied may seek to narrow the discrepancy between themselves and the referents by learning or seeking advice, thus improving their core performance (Lee & Duffy, 2019). The model of three types of workplace envy provides insights into both the negative and positive aspects of envy (Cheng & McCarthy, 2018).

Future research should reconsider how envy is measured. Many measurement approaches have been applied, but we suggest that the model of three types of workplace envy can help to develop a holistic envy measure. The model in this study provides a basic framework that can be further developed.

Future research could also consider new methods of studying workplace envy. Researchers should reconsider whether workplace envy should be investigated as part of an envious and envied dyad. Instead of focusing on the envious, the feeling of being envied could be further explored, as those who are envied may reassess their behavior to obtain a sense of belongness (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Novel research designs could be used to categorize the antecedents and consequences of envy, thus investigating causality in a reverse direction from that generally hypothesized (e.g., can fairness trigger envy?). Behaviors, emotions, and perceptions may be both antecedents and consequences of workplace envy. Current research designs do not enable us to easily conclude whether a variable is a cause or an outcome. Thus, novel research designs are required, such as longitudinal and experimental designs, to identify whether the variables (such as fairness) are best conceptualized as antecedents, consequences, or both of workplace envy.

Researchers should also investigate other moderating effects. For example, workplace envy may have different relationships in individualist or collectivist cultures (Hofstede, 2011). Collectivism may lead individuals to suppress negative emotions in favor of pursuing interpersonal harmony and solidarity (Lee & Duffy, 2019). Thus, cross-cultural research into workplace envy is required.

Limitations

Consistent with previous meta-analyses (Howard et al., 2020), we aggregate similar constructs together to ensure that the total number of studies met the sufficient effect size requirements for our selected methodology. Using different measures may reveal subtle differences in familiar constructs. In the Supplementary Material 1 and 2, representative constructs and labels are provided, allowing further insights into any dimensions (or subgroups) with variables that can be conceptualized from different perspectives.

Due to the small number of studies, there may be sampling error in this meta-analysis, such that a significant moderating effect is “unlikely to be detected because of low statistical power” (Hunter & Schmidt, 2004, pp. 68–70). For example, a larger sample size should be used to assess the relationship between envy and core performance, as our assumption that performance triggers envy and envy may influence core performance is not supported by our results. Hunter and Schmidt’s (2004) meta-analysis procedure reports random effects. In this meta-analysis, we also offer random and mixed effects in the Supplemantary Materal 4, including the R syntax results. The fixed effects and random effects are visualized as forest plots in the Supplementary Material 4, providing a clear illustration of the meta-analytic review. Funnel plots are also provided to visualize publication bias. The applied method is the most suitable for the current analytical approach, and can thus be confidently used in future meta-analyses.

Conclusion

We review the envy literature and develop a model of workplace envy that considers episodic envy (within-person), dispositional envy (between-person), and general envy, and test a meta-analytic model of the antecedents and outcomes of workplace envy based on social comparison theory. Our meta-analytic review is aimed at encouraging future research to explore the contextual antecedents, test the moderation effects of different mechanisms, and examine whether the commonly tested variables are antecedents or consequences of workplace envy.

References

All references included in meta-analysis are marked with an (*) asterisk

American Psychological Association. 2020. Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.). Author.

Ashmore, R. D., Deaux, K., & McLaughlin-Volpe, T. 2004. An organizing framework for collective identity: articulation and significance of multidimensionality. Psychological Bulletin, 130(1): 80–114.

*Aydin Küçük, B., & Taştan, S. 2019. The examination of the impact of workplace envy on individual outcomes of counterproductive work behavior and contextual performance: The role of self-control. Suleyman Demirel University Journal of Faculty of Economics & Administrative Sciences, 24(3): 735–766.

*Bamberger, P., & Belogolovsky, E. 2017. The dark side of transparency: How and when pay administration practices affect employee helping. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(4): 658–671.

Bandura, A. 1982. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2): 122–147.

Bandura, A. 1999. Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3(3): 193–209.

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. 2001. Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology, 5(4): 323–370.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. 1995. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3): 497–529.

Bennett, R. J., & Robinson, S. L. 2000. Development of a measure of workplace deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 349–360.

Blau, G., & Andersson, L. 2005. Testing a measure of instigated workplace incivility. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78(4): 595–614.

Bogart, L. M., Benotsch, E. G., & Pavlovic, J. D. P. 2004. Feeling superior but threatened: The relation of narcissism to social comparison. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 26(1): 35–44.

*Boone, A. L. 2005. The green-eyed monster at work: An investigation of how envy relates to behavior in the workplace. (Ph.D.). George Mason University, Ann Arbor. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global database. (3176928)

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P., & Rothstein, H. R. 2009. Introduction to meta-analysis. John Wiley & Sons.

*Braun, S., Aydin, N., Frey, D., & Peus, C. 2018. Leader narcissism predicts malicious envy and supervisor-targeted counterproductive work behavior: Evidence from field and experimental research. Journal of Business Ethics, 151(3): 725–741.

Brown, D. J., Ferris, D. L., Heller, D., & Keeping, L. M. 2007. Antecedents and consequences of the frequency of upward and downward social comparisons at work. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 102(1): 59–75.

Buengeler, C., Piccolo, R. F., & Locklear, L. R. 2021. LMX Differentiation and group outcomes: A framework and review drawing on group diversity insights. Journal of Management, 47(1): 260–287.

Burnette, J. L., O'Boyle, E. H., VanEpps, E. M., Pollack, J. M., & Finkel, E. J. 2013. Mind-sets matter: A meta-analytic review of implicit theories and self-regulation. Psychological Bulletin, 139(3): 655–701.

Buunk, A. P., & Gibbons, F. X. 2007. Social comparison: The end of a theory and the emergence of a field. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 102(1): 3–21.

Buunk, B. P., Zurriaga, R., Gonzalez-Roma, V., & Subirats, M. 2003. Engaging in upward and downward comparisons as a determinant of relative deprivation at work: A longitudinal study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 62(2): 370–388.

*Castiglione, A. 2010. Counterproductive work behaviors: The role of employee support policies, envy, and narcissism. (M.S.). California State University, Long Beach, Ann Arbor. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global database. (1493097)

Cheng, B. H., & McCarthy, J. M. 2018. Understanding the dark and bright sides of anxiety: A theory of workplace anxiety. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(5): 537–560.

*Cohen-Charash, Y. 2000. Envy at work: An exploratory examination of antecedents and outcomes. (Ph.D.). University of California, Berkeley, Ann Arbor. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global database. (3001795)

Cohen-Charash, Y. 2009. Episodic Envy. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 39(9): 2128–2173.

Cohen-Charash, Y., & Larson, E. 2016. What is the nature of envy. Envy at work and in organizations, 1–37.

*Cohen-Charash, Y., & Mueller, J. S. 2007. Does perceived unfairness exacerbate or mitigate interpersonal counterproductive work behaviors related to envy? Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(3): 666–680.

Colquitt, J. A., Scott, B. A., Rodell, J. B., Long, D. M., Zapata, C. P., Conlon, D. E., & Wesson, M. J. 2013. Justice at the millennium, a decade later: a meta-analytic test of social exchange and affect-based perspectives. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(2): 199–236.

Crusius, J., Gonzalez, M. F., Lange, J., & Cohen-Charash, Y. 2020. Envy: An adversarial review and comparison of two competing views. Emotion Review, 12(1): 3–21.

*De Clercq, D., Haq, I. U., & Azeem, M. U. 2018. The roles of informational unfairness and political climate in the relationship between dispositional envy and job performance in Pakistani organizations. Journal of Business Research, 82: 117–126.

*Demirtas, O., Hannah, S. T., Gok, K., Arslan, A., & Capar, N. 2017. The Moderated influence of ethical leadership, via meaningful work, on followers’ engagement, organizational identification, and envy. Journal of Business Ethics, 145(1): 183–199.

*Dineen, B. R., Duffy, M. K., Henle, C. A., & Lee, K. 2017. Green by comparison: Deviant and normative transmutations of job search envy in a temporal context. Academy of Management Journal, 60(1): 295–320.

Duffy, M. K., Lee, K., & Adair, E. A. 2021. Workplace envy. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 8(1): 19–44.

*Duffy, M. K., Scott, K. L., Shaw, J. D., Tepper, B. J., & Aquino, K. 2012. A Social Context Model of Envy and Social Undermining. Academy of Management Journal, 55(3): 643–666.

*Duffy, M. K., & Shaw, J. D. 2000. The Salieri syndrome: Consequences of envy in groups. Small Group Research, 31(1): 3–23.

*Eissa, G., & Wyland, R. 2015. Keeping up with the Joneses. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 23(1): 55–65.

Erdil, O., & Muceldili, B. 2014. The effects of envy on job engagement and turnover Intention. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 150: 447–454.

Ferris, D. L., Brown, D. J., Berry, J. W., & Lian, H. 2008. The development and validation of the workplace ostracism scale. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6): 1348–1366.