Abstract

The purpose of this article is to understand how academic integrity educational tutorials are administered across Canadian higher education. Results are shared from a survey of publicly funded Canadian higher education institutions (N = 74), including universities (n = 41) and colleges (n = 33), across ten provinces where English is the primary language of instruction. The survey contained 29 items addressing institutional demographic details, as well as academic integrity education questions. Results showed that academic integrity tutorials are inconsistent across Canadian higher education, with further differences evident within the university and college sectors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Article

The importance of supporting educational environments that promote and engage students and faculty in learning, teaching, and researching with integrity, remain integral to the success and missions of higher education organizations around the world. Recent challenges to our educational systems, as a direct result of the COVID-19 pandemic, have stressed and tested existing organizational structures, educational pedagogies, and processes that aim to protect, preserve, and promote academic integrity efforts across higher education. These efforts in turn continue to ensure quality learning environments. Because our higher education organizations are complex systems, effective efforts to ensure that learning environments are grounded in integrity must be multifaceted and responsive to changing needs. How we educate and acculturate our students to the expectations for their studies and conduct, that are consistent with the values aligned with academic integrity like honesty, trust, fairness, respect, responsibility, and courage, are worth exploring and discussing (International Centre for Academic Integrity, 2021). This article serves to inform our understanding about the use and intent of student academic integrity tutorials in universities and colleges in Canada. Specifically, we report findings about existing academic integrity education efforts through tutorials, highlighting similarities and differences in delivery of such content between Canadian universities and colleges.

Literature Review

Existing literature focused on academic integrity across higher education is replete with studies that report the incidence, reasons, and various forms of student academic dishonesty (Hensley et al., 2013; Lang, 2013; McCabe et al., 2001; Tatum et al., 2018). Some studies show expectations of faculty and students are misaligned in terms of how well-prepared students are to enter higher education, including expectations regarding academic integrity within their learning environments. This misalignment between expectations result in student integrity transgressions and student dissatisfaction with their educational journeys (Bretag et al., 2014; Curtis et al., 2013). Opportunity, for faculty, leaders, and students in higher education, rests in our efforts to orient, teach, and engage students with academic integrity (Peters et al., 2019). Additionally, higher education students’ interactions with their organizations’ cultural landscapes influence their beliefs and actions related to integrity (Young et al., 2018).

Efforts to understand the effectiveness of educational initiatives that focus on relevant academic integrity content suggest that while successes exist with student satisfaction, and an immediate increased knowledge of academic integrity, there remains a paucity of current research focused on changes to student behaviours and adherence to integrity on a longer-term basis. Stoesz and Yudintseva (2018) synthesized findings from twenty-one articles and report on research completed internationally (United States, United Kingdom, Australia, Sweden, Qatar, Taiwan). They conclude that it remains unclear if one specific approach to teaching academic integrity is most effective, when considering face-to-face, e-learning, and blended approaches (Stoesz & Yudintseva, 2018). In turn, an Australian team completed an extensive review of approaches to online delivery and applied Mayer’s Theory and Principles of Multimedia Learning to their offering of an academic integrity course at their higher education organization (Bing et al., 2016). This theory suggests that learning happens through students’ information processing (visual and auditory), basic principles of multimedia learning that include issues like the intentional use of graphics, and boundary conditions like individual student learning needs and the complexity of content. They concluded that a deliberate multimedia approach to online design “works for students when assimilating, integrating, retaining, and creating deeper meaning” based on their usability testing with students (Bing et al., 2016, p. 12).

Evidence suggests that faculty play important roles in modelling desired behaviours and conduct, as well as teaching essential skills that equip students to engage with their studies with integrity (Garza Mitchell & Parnther, 2018). Academic writers suggest that when students have positive relationships with their instructors, they are less likely to be dishonest and feel connected to their learning and those teaching them (Clark & Soutter, 2016; Peters et al., 2019; Stoesz & Yudintseva, 2018). Seventy-five percent of senior undergraduate nursing students (N = 339) from across three different educational organizations reported they rely on their professors/instructors to help them learn about academic integrity (Miron, 2016). As well, in designing and teaching academic integrity it is important to consider students in a more holistic manner. Acculturating students to integrity may rest with a broader educational approach to address students’ moral, intellectual, civic, and performance development (Clark & Soutter, 2016).

Content included in academic integrity tutorials often serves to orient and educate students on understanding organizational processes and supports, as well as to outline the behavioural expectations that will support their successful engagement in post-secondary learner roles. Content is often intended to expose and prepare students for the requirements needed to behave with integrity in higher education (Eaton, 2019). Approaches to the successful development of such tutorials, that are sensitive to the idiosyncrasies and nuances of each organization, must be carefully and strategically planned for when undertaking this work (Eaton, 2019; Levine & Pazdernik, 2018; Orr, 2018). Such nuances require consideration of content, key players, and best approaches to delivery of content. Orr (2018) notes that buy-in and success of such educational programs are cultivated when we review and clearly understand our organizations’ “academic misconduct troubles” (p. 206) and work to include a variety of organization members’ voices.

Contributions to Knowledge

The literature and research available to help us understand the current experience with academic integrity teaching across Canada is sparse (Eaton & Edino, 2018). The authors share an interest in learning more about tutorials focused on academic integrity content across Canadian universities and colleges. Informing our understanding of current educational practices can create opportunities, disseminate knowledge, stimulate conversation on the topic, and provoke interest in additional research.

Theoretical Framing

A foundational tenet of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) is that the intentions that predict behavior include attitudes, perceived norms and perceived behavioral expectations (Ajzen, 1991; Ajzen, & Sheikh, 2013). TPB is a common theoretical framing of academic integrity studies (Coren, 2012; Curtis et al., 2018; Harding et al., 2007). TPB frames academic integrity tutorials as a method to help develop students’ attitudes regarding the value of learning with integrity, as well as to teach them the perceived educational norms and behavioral expectations regarding academic integrity within higher educational contexts.

Method

Our research method followed a quantitative approach through a nonexperimental exploratory survey (LoBiondo-Wood & Harper, 2017).

Research Questions

The primary and secondary questions that guided the project were:

-

(RQ1): What is the rate of higher educational organizations in Canada that use student academic integrity educational tutorials (university and colleges)?

-

(Sub-RQ2): Is there a difference between the rates of Canadian universities using academic integrity educational tutorials compared to Canadian colleges?

-

(Sub-RQ3): Are there differences in how, why, and when student academic integrity educational tutorials are used between universities and colleges?

Research Ethics

Research ethics were obtained through the researchers’ schools in June of 2018. Informed consent was obtained through a detailed explanation of risks and benefits to the respondents from the various higher education organizations who then indicated consent by implied action through an online acceptance of the research terms before completing the survey. Participants were advised that they could drop out of the research without fear of reprisal. Data were kept confidential and secured through password protected access by the researchers.

Sample (Inclusion/Exclusion)

Non-random purposive sampling (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016) was employed to recruit participant institutions on a Pan-Canadian level. Initially all private and public funded higher education organizations across all but the three territories in Canada (Northwest Territories, Nunavut, and the Yukon) were included in the study. Difficulty in locating information about higher education contacts for the three Canadian territories made it difficult to include these regions in the initial research. Our final sample initially intended to include private and public funded higher education organizations information from the ten Canadian provinces, however a decision was made after collecting the data to proceed with analyzing data from all English public funded higher education organizations that responded to the survey.

Phase I

In the fall of 2018, online surveys were developed considering available research that discussed online learning, the pedagogy of teaching–learning, and academic integrity (Atkinson et al., 2016; Green et al., 2010; Griffith, 2013; Lowe et al., 2018; Singh & Hurley, 2017; Smith et al., 2010; Tallent-Runnels et al., 2006). Two separate surveys were created to capture the nuanced differences between colleges and universities using SurveyMonkey®. The final survey development was agreed upon through an iterative process between the researchers with the help and consultation of various experts in survey development, education, and academic integrity. Each survey consisted of 29 items that included demographic information as well as specific academic integrity module queries (Appendix A; Appendix B).

Parallel work was completed in Phase I with the help of a work-study student (Laura McBreairty). The student completed an initial review of all Canadian higher education websites to obtain appropriate contact people who were identified with roles or expertise in academic integrity, at each organization. This information was populated to a spreadsheet and supported the work of email dissemination of the online surveys.

Phase II

During the second phase of the research the developed surveys were sent to the contacts identified by the work-study student in phase I. The first round of emails was sent with an explanation of the study, and an invitation to participate in the study in October–December 2018. Surveys were sent to higher education organizations across all Canadian provinces (the three territories were excluded).

From February to March 2019, a second call for participation was sent out to the same higher education organizations with a thank you for those who had already participated. This set of emails also provided higher education organizations, who had not yet participated, an opportunity to do so with access to the survey online. Again, a deadline of two weeks was set.

The overall sample resulted in responses from n = 44 universities and n = 38 colleges (combination of privately and publicly funded organizations N = 82). Since the response rate from private higher educational organizations was low, it was decided to narrow the focus for analysis to explore the publicly funded institutions.

A list of publicly funded higher education institutions with English as the primary language of instruction was created (Jennifer Miron) and verified by a review of provincial government sites, and experts living and teaching in each of the provinces. Gaps in the data resulted since only seven of the nine provinces surveyed recorded responses, with some universities and colleges within the participating provinces not recording responses (Table 1).

Analysis

Data from the online surveys were analyzed using SPSS-23 with the help of a research assistant (Heba Baig). The final response rate of English, publicly funded universities and colleges were seventy-four (N = 74). Sixty-six percent of the university sub-sample (n = 41) reported having academic integrity tutorials compared to 55% of the college sub-sample (n = 33). Our final analysis is then based on the aforementioned English, public funded universities and colleges who reported having academic integrity tutorials across seven Canadian provinces (n = 27; n = 18 respectively). Since the numbers varied between provinces, it was also decided to analyze the data set for all universities and colleges rather than province by province (Table 1).

Demographic Findings

The survey was most often completed by administrators at both universities and colleges (48%; 56%) followed by a category of other (37%; 22%), and faculty (15%; 17%). The other category accounted for those working in roles such as academic integrity coordinators/officers, support staff, librarians, administrative staff, academic skills instructors, and roles in centres for teaching and learning. The majority of respondents had worked at their organization between 1-5 years (52% university: 61% college). Seventy-four percent of universities and 52% of colleges were organizations with over 10,000 students. Sixty-seven percent of all respondents reported having assigned roles for academic integrity work.

Additional Findings

English was the primary language that academic integrity tutorials were offered for both universities and colleges (89%). A French version was offered 11% of the time in both types of organizations. The estimated time to complete the educational session took less than one hour in universities (52%) compared to one to four hours at colleges (56%). Both universities and colleges offered academic integrity education most often through one module (63% universities; 50% colleges), with certificates of completion offered at universities 33% of the time, compared to colleges (22%). About half of the respondents at both organizations believed no research had been undertaken related to the academic integrity modules (52% universities; 50% colleges). Universities relied on library staff to deliver academic integrity education (30%) followed by individual faculty members (11%). The picture was different for colleges that reported a higher percentage of individual faculty members taking responsibility (33%) followed by the library staff (22%).

The frequency of content that included information about various aspects of scholarly writing were priorities for both organizations but varied between universities and colleges. Plagiarism was the primary focus for both organizations although paraphrasing, referencing, and citing were areas of higher interest for universities when compared to colleges. Other skills such as citing, and research skills were less of a focus but still higher in university than college modules. The item of cheating was not specifically defined on the survey but was an item that was reported as covered through the education tutorials more with the college respondents than the university group. Content on collusion was higher with universities, however impersonation was covered more thoroughly in the college tutorials. The concept of contract cheating was one of the lowest content areas when looking at both universities and colleges. Both organizations covered content related to academic integrity policies for their respective organizations although, including content that discussed how to access this information was higher in the university grouping (Table 2).

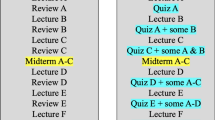

A higher percentage of respondents across both types of higher education organizations reported that academic integrity tutorials were not made available to all students (Table 3). Not all respondents answered questions related to the time when tutorials were administered to students, but of the responses received both organizations reported the tutorials were more often delivered during the students’ first semester. As for the timing of tutorial administrations the other category captured responses related to students completing tutorials at any time over their studies, and as often as they wanted. Again, both university and college respondents noted that the tutorials were intended to be educative in approach, but they seemed less clear as to whether tutorials were also used for student remediation. Tutorials at universities had higher reports of prevention of academic dishonesty and promotion of integrity as the foci for the content of the tutorials when compared to the colleges. Universities were less likely to have learning outcomes associated with the tutorials than their college counterparts. A high percentage of both organizations reported that their tutorials included quizzes, but universities were less likely to track student success than colleges. The majority of the sample for both organizations reported that students were not held back from their studies if they had not successfully completed the tutorials. Tutorials were largely administered online (Fig. 1) at both types of organizations with much smaller offerings of content through face-to-face and blended/hybrid modalities. Strategies of academic integrity workshops, specific library sessions, and hands on activities were employed less often.

Limitations

There were several limitations to the study. First, the survey was not tested for reliability or validity and its purpose was to explore and gather information about the current situation for academic integrity tutorials across Canada. Second, the distribution of the surveys was largely dependent on the success of accessing names and contact information for higher education organizations available through their main school websites. It is possible that if a survey was sent to an individual who did not have information about academic integrity tutorials, or was not interested in the subject matter, it may not have been forwarded to the most appropriate person for completion. This may account for the low overall response rate since there are over 160 recognized private and public universities and 180 colleges across the country (Council of Ministers of Education, n. d.). Future research should include a contact for each province and territory who could advise and perhaps secure contact names for each targeted organization. Finally, Canada has two official languages, but this study was conducted in English only, due mainly to limited language proficiency of the authors. Efforts will be made in a second stage of this research to translate the survey and administer it to those higher education organizations that identify as primarily French language schools.

Discussion

In this exploratory study, we learned that educational approaches about academic integrity were inconsistently applied across colleges and universities in terms of who taught the content, when content was delivered, what content was covered in tutorials, the accessibility of content to all students, and the level and investment of time expected of the student for completion. As well, there were differences in the delivery method for the tutorials, their intended foci, and their organized structure.

Research Question 1

What is the rate of higher educational organizations in Canada that use student academic integrity educational tutorials (university and colleges)?

In considering the current research study it is important to note that our sample represented about 57% of all English publicly funded higher educational organizations across the ten Canadian provinces. So, our findings should be considered with caution. That being said, we noted that over sixty percent of the responding organizations reported having academic tutorials in place for their students.

Research Question 2

Is there a difference between the rates of Canadian universities using academic integrity educational tutorials compared to Canadian colleges?

In the current study university responses indicated that those organizations used academic integrity tutorials to educate their students more often than their college counterparts.

Research Question 3

Are there differences in how, why, and when student academic integrity educational tutorials are used between universities and colleges?

Our third research question revealed data that are important to consider. There is academic debate that scaffolded approaches to teaching specific skills required by students in higher education is an important aspect to the successful acculturation of students to the values of academic integrity. Emerson et al. (2005) reported that plagiarism with first year university students (N = 142) was the result of more than their misunderstandings of the conventions of scholarly writing. They suggested a scaffolded, multi-dimensional approach to engaging with students through interactive teaching benefitted students’ understanding around expectations for honest writing. Garza et al. (2018) reported success through their college environments when a variety of learning opportunities were provided to students including, policy information shared through student handbooks, course catalog information that included academic integrity, syllabi academic integrity content, writing classes, and library sponsored modules on literacy. Findings from this study suggest that tutorials are one strategy used to teach content specific to academic integrity and are often taught using one offering and during students’ first semester. Successes such as the ones reported by Garza Mitchell and Parnther recognize the educational experience as a developmental one so that initial academic integrity tutorials offer an opportunity to lay a foundation for the content, but it is important to approach our teaching from different vistas.

The notion of a “one and done” approach to teaching academic integrity merits closer scrutiny. Circling back to the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Ajzen & Sheikh, 2013), it is reasonable to expect that students’ understanding of educational behavioral norms and expectations develop over time, as they encounter concrete instances in which ethical decision-making is required in various contexts and throughout their academic journey. Past successful strategies to help students understand honesty within the academic environment include information and academic integrity language through syllabi and course outlines accompanied by clearly set expectations and opportunities for discussion on the topic (Löfström et al., 2015; Miron, 2016). One tutorial, as is currently reported most often by Canadian universities and colleges, should be considered a starting point and work in combination to other learning opportunities that fully effect students’ understandings for what is expected in their roles as learners. Helping students to understand at the start of their higher education journey just what is expected and why serves an important purpose in an introductory tutorial and may serve to be a powerful starting point (Hyytinen & Löfström, 2017).

Academic integrity content was most often taught by library staff, and individual faculty members. Our research did not explore how academic integrity was being taught apart from a tutorial approach, but it is important to consider the potential challenges to situating tutorials separately from what is happening in the classroom, if they are stand-alone efforts. Emerson et al. (2005) noted that relationships with teaching assistants played a large role in students appreciating and committing to writing with integrity. The pivotal role faculty play through their relationships with students must be emphasized. Students have reported their reliance on faculty to help them understand expectations related to academic integrity (Miron, 2016; Peters et al., 2019). Modeling and mentoring the values of academic integrity combined with teaching content specific to academic integrity and expectations across the students’ learning career will support the development of students’ ethical and moral comportment. Peters et al. (2019) noted that faculty who adopt an ambassador role toward academic integrity engage students systematically to teach them the importance of integrity in their academics. Peters et al. suggested that this role engages, promotes, encourages, and inspires students to learn through tangible teaching about academic integrity within the higher education setting.

Assumptions that students are prepared and understand their responsibilities in the higher education landscape are misplaced so strategies that include descriptions for assignments and conduct in learning environments are important to share and model consistently with students and across courses. Current research suggests that dichotomies exist across faculty teaching in higher education. Löfström et al. (2015) studied academics teaching in higher education in Finland and New Zealand (N = 56) who reported beliefs that academic integrity teaching included more than focusing on the rules of the academy. They also believed they were qualified to teach about academic integrity but disagreed on how to teach it and if it was teachable to every student. Upholding and enacting academic integrity requires a multi-stakeholder approach (Morris, 2016). It is unlikely that a single academic integrity tutorial can provide students with adequate understanding of the institutional behavioral expectations regarding academic integrity that can be enacted across various courses throughout a student’s program. This study showed few links, if any, between academic integrity tutorials and classroom student experience. How faculty design and manage their classroom activities and members helps shape student integrity practices (Garza Mitchell & Parnther, 2018). It is worth noting that relational pedagogy may play an important role in acculturating students to values consistent with academic integrity since at its core it “encourages students to invest more in their own learning” (Lertora et al., 2020, p. 206). So, those relationships between faculty and students are paramount to academic integrity efforts. While faculty play key roles in teaching academic integrity, there is also an argument that suggests a shared responsibility is fundamental to maintaining and promoting cultures of integrity (Garza Mitchell & Parnther, 2018; Morris, 2016).) Faculty, staff, administrators and students are collectively responsible for promoting integrity across higher education settings. They warn that a separation of roles or imbalance of one group taking responsibility jeopardizes integrity and may set up organizations to focus on dishonesty rather than integrity.

What is being taught across different organizations through tutorials varied. This finding makes sense in that it is important for organizations to understand where their vulnerable or pressure points are to ensure students have clear understandings and the skills, they need to avoid breaching integrity. By identifying the factors that lead students to breach integrity, organizations can develop integrity education that makes sense to the unique needs of its members (Orr, 2018). A positive and practical approach to tutorials may also enable members across the community to avoid assigning blame and shame and instead help focus initiatives on increased knowledge and improved learning skills. Such knowledge and skill translate to careers after students graduate and benefit those delivering and receiving care and services from graduates (Orr, 2018).

Conclusion

Cultures of academic integrity are built and sustained through the cooperation and commitment of all members of the learning community. Bertram Gallant and Drinan (2006) suggest student academic dishonesty boils down to an adaptive challenge for students who must learn and demonstrate integrity in conduct and behavior within the context of the higher education learning environments. In fact, they note that academic dishonesty is not the result of individual dysfunction but rather a systematic and organizational issue (Bertram Gallant & Drinan, 2006). Approaches to the acculturation of students to the values associated with academic integrity must be multi-faceted and include clear, accessible policies and procedures, and educational initiatives that consider developmental, relational approaches to teaching and learning.

Our research questions focused on the use of academic integrity tutorials in Canadian higher education contexts, with a further focus on the differences that might exist between how universities and colleges utilize such tutorials. Our results showed inconsistencies in how academic integrity education is implemented across Canadian higher education institutions, with few links to classroom practice. Overall, there is a need for Canadian higher education institutions to attend to the needs of students in terms of understanding and enacting institutional expectations for ethical learning behavior in a variety of ways, of which tutorials are only one component. A more integrated and intentional approach to academic integrity education that emphasizes learning about ethical conduct as a developmental process that continues throughout formal education and beyond is needed moving forward.

Data Availability

The majority of the data generated and analyzed during the study are included in this published article. Any additional datasets specific to the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Ajzen, I., & Sheikh, S. (2013). Action versus inaction: Anticipated affect in the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43(1), 155–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.00989.x

Atkinson, D., Nau, S. Z., & Symons, C. (2016). Ten years in the academic integrity trenches: Experiences and issues. Journal of Information Systems Education, 27(3), 197–207.

Bertram Gallant, T. & Drinan, P. (2006). Organizational theory and student cheating: Explanation, responses, and strategies. The Journal of Higher Education, 77(5), 839–860. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2006.0041

Bing, T., Reid, S., & Ivanovic, V. (2016). Paint me a picture: Translating academic integrity policies and regulations into visual content for an online course. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 12(2), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-016-0008-8

Bretag, T., Mahmud, S., Wallace, M., Walker, R., McGowan, U., East, J., & James, C. (2014). “Teach us how to do it properly!” An Australian academic integrity student survey. Studies in higher education, 39(7), 1150–1169. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2013.777406.

Clark, S., & Soutter, M. (2016). A broad character education approach for addressing America’s cheating culture. Journal of Character Education, 12(2), 29.

Coren, A. (2012). The theory of planned behaviour: Will faculty confront students who cheat? Journal of Academic Ethics, 10(3), 171–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-012-9162-7

Council of Ministers of Education (CMEC) Canada. (n.d.). Education in Canada: An overview. Retrieved from https://www.cmec.ca/299/Education-in-Canada-An-Overview/index.html#04

Curtis, G. J., Gouldthorp, B., Thomas, E. F., O’Brien, G. M., & Correia, H. M. (2013). Online academic-integrity mastery training may improve students’ awareness of, and attitudes toward, plagiarism. Psychology Learning & Teaching, 12(3), 282–289. https://doi.org/10.2304/plat.2013.12.3.282

Curtis, G., Cowcher, E., Greene, B., Rundle, K., Paull, M., & Davis, M. (2018). Self-Control, injunctive norms, and descriptive norms predict engagement in plagiarism in a Theory of Planned Behavior Model. Journal of Academic Ethics, 16(3), 225–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-018-9309-2

Eaton, S. E. (2019). Contract Cheating in Canada: National policy analysis. Open Science Framework. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/N9KWT

Eaton, S. E., & Edino, R. I. (2018). Strengthening the research agenda of educational integrity in Canada: A review of the research literature and call to action. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 14(5):1-21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-018-0028-7

Emerson, L., MacKay, B., & Rees, M. (2005). Plagiarism in the science classroom: Misunderstandings and models. Retrieved from http://www.newcastle.educ.au/conference/apeic/papers.html

Garza Mitchell, R. L., & Parnther, C. (2018). The shared responsibility for academic integrity education. New Directions for Community Colleges, 2018(183), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/cc.20317

Green, N. C., Edwards, H., Wolodko, B., Stewart, C., Brooks, M., & Littledyke, R. (2010). Reconceptualising higher education pedagogy in online learning. Distance Education, 31(3), 257–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2010.513951

Griffith, J. (2013). Pedagogical over punitive: The academic integrity websites of Ontario universities. The Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 43(1), 1–22.

Harding, T. S., Mayhew, M. J., Finelli, C. J., & Carpenter, D. D. (2007). The theory of planned behavior as a model of academic dishonesty in engineering and humanities undergraduates. Ethics & Behavior, 17(3), 255–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508420701519239

Hensley, L. C., Kirkpatrick, K. M., & Burgoon, J. M. (2013). Relation of gender, course enrollment, and grades to distinct forms of academic dishonesty. Teaching in Higher Education, 18(8), 895–907. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2013.827641

Hyytinen, H., & Löfström, E. (2017). Reactively, proactively, implicitly, explicitly? Academics’ pedagogical conceptions of how to promote research ethics and integrity. J Acad Ethics, 15(1), 23–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-016-9271-9

International Center for Academic Integrity (ICAI). (2021). The fundamental values of academic integrity (3rd ed.). Retrieved from https://www.academicintegrity.org/wpcontent/uploads/2021/02/20019_ICAI-Fundamental-Values_R11.pdf

Lang, J. M. (2013). Cheating lessons: Learning from academic dishonesty. Harvard, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lertora, I., Croffie, A., Dorn-Medeiros, C., & Christensen, J. (2020). Using relational cultural theory as a pedagogical approach for counsellor education. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 15(2), 265–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2019.1687058

Levine, J., & Pazdernik, V. (2018). Evaluation of a four-prong anti-plagiarism program and the incidence of plagiarism: a five-year retrospective study. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(7), 1094–1105. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1434127

LoBiondo-Wood, G., Haber, J. (2017). Nursing research: Methods and critical appraisal for evidence-based practice. Mosby, Canada.

Löfström, E., Trotman, T., Furnari, M., & Shephard, K. (2015). Who teaches academic integrity and how do they teach it? Higher Education, 69(3), 435–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9784-3

Lowe, M. S., Londino-Smolar, G., Wendeln, K. E. A., & Sturek, D. L. (2018). Promoting academic integrity through a stand-alone course in the learning management system. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 14(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-018-0035-8

McCabe, D. L., Treviño, L. K., & Butterfield, K. D. (2001). Dishonesty in academic environments. The Journal of Higher Education, 72(1), 29–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2001.11778863

Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. (4th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Miron, J. (2016). Academic integrity and senior nursing undergraduate clinical practice. [Doctoral dissertation, Queen's University]. Queen's Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://hdl.handle.net/1974/14708

Morris, E. J. (2016). Academic Integrity: A teaching and learning approach. In T. Bretag (Ed.), Handbook of Academic Integrity. (pp. 1037–1053). Singapore: Springer Singapore.

Orr, J. (2018). Developing a campus academic integrity education seminar. Journal of Academic Ethics, 16(3), 195–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-018-9304-7

Peters, M., Boies, T., & Morin, S. (2019). Teaching academic integrity in Quebec universities: Roles professors adopt. Frontiers in Education, 4(99), 1–13.

Singh, R., & Hurley, D. (2017). The effectiveness of teaching and learning process in online education as perceived by university faculty and instructional technology professionals. Journal of Teaching and Learning with Technology, 6(1), 65-75. https://doi.org/10.14434/jotit.v6.n1.19528

Smith, T., Edwards-Groves, C., & Brennan Kemmis, R. (2010). Pedagogy, education and praxis. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 18(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681360903556749

Stoesz, B., & Yudintseva, A. (2018). Effectiveness of tutorials for promoting educational integrity: A synthesis paper. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 14(6). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-018-0030-0

Tallent-Runnels, M., Thomas, J., Yan, W., Cooper, S., Ahern, T., Shaw, S., & Liu, X. (2006). Teaching courses online: A review of the research. Review of Educational Research, 76(1), 93–135. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543076001093

Tatum, H. E., Schwartz, B. M., Hageman, M. C., & Koretke, S. L. (2018). College students’ perceptions of and responses to academic dishonesty: An investigation of type of honor code, institution size, and student-faculty ratio. Ethics & Behavior, 28(4), 302–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2017.1331132

Young, R., Miller, G., & Barnhardt, C. (2018). From policies to principles: The effects of campus climate on academic integrity, a mixed methods study. Journal of Academic Ethics, 16(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-017-9297-7

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jennifer Miron and Sarah Elaine Eaton contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were completed by Jennifer Miron and Sarah Elaine Eaton. Initial data collection was completed by Laura McBreairty. Data entry was completed by Heba Baig. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Jennifer Miron and Sarah Elaine Eaton contributed to the continued development and revisions. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

REB Approval

This research project has been approved by the Humber-ITAL Research Ethics Board. Participants are encouraged to ask any questions at any time (before, during, or after participating), about the study, its procedures, or their rights as a participant. If you have any questions or study-related problems, please feel free to contact Jennie Miron (jennie.miron@humber.ca). If you have any questions about ethics approval or your rights as a research participant, please contact REB chair at Humber College ITAL.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Miron, J., Eaton, S.E., McBreairty, L. et al. Academic Integrity Education Across the Canadian Higher Education Landscape. J Acad Ethics 19, 441–454 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-021-09412-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-021-09412-6