Abstract

Previous theoretical and computational analyses demonstrate that uncorrelated variations in individual asset returns promote extreme inequality in financial wealth. This paper describes a standard individual-based computational model of this financial accumulation process and then extends it in order to expose other key influences on wealth inequality. We find large effects of individual behavior, cultural practices, tax policy, and technological change. Specifically, we present simulation experiments with heterogeneous saving rates, a stylized marriage institution, a wealth tax structured to mirror contemporary policy proposals, and variations in wage growth. These experiments demonstrate that modest concessions to realism have large effects on long-run wealth inequality in models of the financial accumulation process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In this literature, it is common to impose a zero-wealth boundary, which effectively truncates R at 0. Whether zero wealth is then likely to be an absorbing boundary for wealth accumulation depends on the model parameterization. For example, it is in Yunker (1999) but it is not in Biondi and Righi (2019).

Python code for this model is available upon request.

This paper does not engage the debate over the boundaries between agent-based models, individual-based models, and econophysics models. Readers should adopt their preferred classification.

Empirically, households appear to experience persistent differences in asset returns (Cao and Luo 2017). Levy and Levy (2003) suggest that individual investment talent may influence investment income, and they therefore extend their baseline model of the financial accumulation process so that \(R_{i,t}\) has an agent-specific mean. In this context, however, they end up arguing that chance (i.e., the stochastic component of \(R_{i,t}\)) must be more important than skill in producing observed wealth inequality. Our baseline implementation of the financial accumulation process therefore focuses on the role of chance. (However, see the "Labor Income and Wealth Inequal" section.)

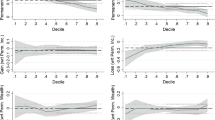

For this experiment, each agent’s saving rate is time invariant. Individual saving rates are distributed uniformly in an interval. The three intervals producing the illustrated results, as implied by the standard deviations reported in the figure legend, are roughly [0.45, 0.55], [0.40, 0.60], and [0.35, 0.65]. In terms of the algebra of the "Algebra for a Financial Accumulation Process" section, period T wealth becomes \(k_{i,T} = k_{i,0} \prod _{t=0}^{T-1} (1 + s_{W,i} r_{t})\), where \(s_{W,i}\) is the saving rate out of investment income for individual i and \(r_t\) is the shared net return on investments in period t.

Not evident when comparing Fig. 5 with Fig. 4 is the difference in wealth mobility across time. When inequality is induced by the baseline financial accumulation process, there is always some individual mobility in the economy’s wealth distribution. In contrast, relative wealth rankings induced by idiosyncratic saving rates persist. As an aside, note that in contrast to Benhabib et al. (2019), these idiosyncratic saving rates are not responses to changes in wealth.

Accordingly, estate taxes with a mean household lifespan of 100 years can have a similar dampening effect on inequality. (Results not shown.)

Discussion of these effects by economists frequently have turned to the language of ethics. For example, Mill (1861) urged that it was “fair and reasonable that the general policy of the State should favour the diffusion rather than the concentration of wealth.” This section eschews the ethical, pragmatic, and legal questions in favor of a descriptive approach.

Germany eliminated its wealth tax amid arguments that it would have to be confiscatory in order to raise substantial revenues. However, recent policy discussion has shifted towards restoring the wealth tax.

Not only are these proposals controversial, but their constitutionality remains debatable: as a direct tax, a wealth tax may be subject to an apportionment rule (Johnsen and Dellinger 2018).

This accords with the citizenship model of Isaac (2008) and public-service redistribution model of Biondi and Righi (2019). In terms of the algebra in the "Algebra for a Financial Accumulation Process" section and footnote 6, at time t an individual i not subject to the wealth tax now saves \(s_W r_{i,t-1} k_{i,t-1} + s_Y a_{t}\) where \(a_{t}\) is the period t national dividend per capita. Contrast with the insurance model of Isaac (2008) or the welfare model of Biondi and Righi (2019), wherein redistribution targets the poorest agents. Since (as shown below) even a national dividend proves very effective at reducing inequality, this paper does not additionally report results for means-tested redistribution.

Reducing the efficiency of redistribution has the same effect on individual wealth accumulation as reducing the saving rate from the national dividend.

For the reported experiment, the labor-income growth rates are deterministic. Allowing transient shocks produces similar results.

References

Ando, Albert, and Franco Modigliani. 1963. The ‘Life Cycle’ hypothesis of saving: Aggregate implications and tests. American Economic Review 53 (1): 55–84.

Atkinson, A.B. 1971. The distribution of wealth and the individual life-cycle. Oxford Economic Papers 23 (2): 239–254.

Benhabib, Jess, Alberto, Bisin, and Mi Luo. 2019. Wealth distribution and social mobility in the US: A quantitative approach. American Economic Review, 109(5): 1623–1647.

Biondi, Yuri and Simone Righi. 2019. Inequality, mobility and the financial accumulation process: A computational economic analysis. Journal of Economic Interaction and Coordination, 14(1): 93–119. Code at https://github.com/simonerighi/BiondiRighi2018_JEIC.

Blinder, Alan S. 1973. A model of inherited wealth. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(4): 608–26.

Bommel, Pierre, and Jean-Pierre. Müller. . 2007. An Introduction to UML for modelling in the human and social sciences, 273–294. Oxford, UK: The Bardwell Press.

Cagetti, Marco, and Mariacristina De Nardi. 2008. Wealth inequality: Data and models. Macroeconomic Dynamics 12 (S2): 285–313.

Cao, Dan, and Wenlan Luo. 2017. Persistent heterogeneous returns and top end wealth inequality. Review of Economic Dynamics 26: 301–326.

Davies, James B., Susanna Sandström, Anthony B. Shorrocks, and Edward N. Wolff. 2009. The level and distribution of global household wealth.” Working Paper 15508, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Díaz-Giménez, Javier, Andy Glover, and José-Victor. Ríos-Rull. . 2011. Facts on the distributions of earnings, income, and wealth in the United States: 2007 update. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review 34 (1): 2–31.

Fernholz, Ricardo and Robert Fernholz. 2014. Instability and concentration in the distribution of wealth. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 44(C): 251–269.

Greenwood, Jeremy, Nezih Guner, Georgi Kocharkov, and Cezar Santos. 2014. Marry your like: Assortative mating and income inequality. American Economic Review, 104(5): 348–53.

Hendricks, Lutz. 2007. How important is discount rate heterogeneity for wealth inequality? Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 31 (9): 3042–3068.

Hubmer, Joachim, Per Krusell, and Jr. Smith, Anthony A. 2016. The historical evolution of the wealth distribution: A quantitative-theoretic investigation. Working Paper 23011, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Huggett, Mark. 1996. Wealth distribution in life-cycle economies. Journal of Monetary Economics 38 (3): 469–494.

Isaac, Alan G. 2008, Winter. Inheriting inequality: Institutional influences on the distribution of wealth. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 30(2): 187–204.

Isaac, Alan G. 2014. The intergenerational propagation of wealth inequality. Metroeconomica 65 (4): 571–584.

Johnsen, Dawn and Walter Dellinger. 2018. The constitutionality of a national wealth tax. Indiana Law Journal, 93(1): Article 8.

Kalecki, Michal. 1945. On the Gibrat distribution. Econometrica 13 (2): 161–170.

Land, K. C. and S. T. Russell. 1996. Wealth accumulation across the adult life course: Stability and change in sociodemographic covariate structures of net worth data in the survey of income and program participation, 1984-1991. Social Science Research, 25(4): 423–462.

Levy, Moshe and Haim Levy. 2003. Investment talent and the pareto wealth distribution: Theoretical and experimental analysis. Review of Economics and Statistics, 85(3): 709–725.

Lorenz, M.O. 1905. Methods of measuring the concentration of wealth. Publications of the American Statitical Association, 9(70): 209–219.

Mill, John Stuart. 1861[1861]. The income and property tax, in the collected works of John Stuart Mill: Essays on economics and society part II, ed. John M. Robson., Volume 5. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. Accessed 02 May 2019.

Object Management Group. 2017. Technical Report: OMG Unified Modeling Language.

Okun, Arthur M. 1975. Equality and efficiency, the big tradeoff. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Oulton, Nicholas. 1976. Inheritance and the distribution of wealth. Oxford Economic Papers, 28(1): 86–101.

Pareto, Vilfredo. 1896–1897. Cours D’Économie Politique. Paris: F. Pichon.

Parzen, E. 1962. On estimation of a probability density function and mode. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics 33 (3): 1065–1076.

Piketty, Thomas. 2014. Capital in the twenty-first century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Rosenblatt, M. 1956. Remarks on some nonparametric estimates of a density function. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics 27 (3): 832–837.

Sargan, J.D. 1957. The distribution of wealth. Econometrica 25 (4): 568–590.

Smith, Karen E., Mauricio Soto, and Rudolph G. Penner. 2009, October. How seniors change their asset holdings during retirement.” Discussion Paper 09-06, Urban Institute.

Steindl, Joseph. 1965. Random processes and the growth of firms: A study of the pareto law. London: Charles Griffin and Company.

Stigler, G., and G. Becker. 1977. De Gustibus non est Disputandum. American Economic Review 67: 76–90.

Sutton, John. 1997. Gibrat’s legacy. Journal of Economic Literature 35 (1): 40–59.

Wold, H. O. A. and P. Whittle. 1957, October. A model explaining the pareto distribution of wealth. Econometrica, 25(4): 591–595.

Yunker, James A. 1998–1999, Winter. Inheritance and chance as determinants of capital wealth inequality. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 21(2): 227–258.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Isaac, A.G. Wealth Inequality and the Financial Accumulation Process. Eastern Econ J 47, 430–448 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41302-021-00191-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41302-021-00191-x