Abstract

This paper analyzes the impact of marriage regulations on the migratory behavior of individuals using the history of the liberalization of same-sex marriage across the USA. The legalization of same-sex marriage allows homosexuals’ access to legal rights and social benefits, which can make marriage more attractive in comparison to singlehood or other forms of partnership. The results clearly show that legalization increased the migration flow of gay men to states that legalized same-sex marriage. We do not detect statistically significant effects for women in the short term. Supplemental analysis, developed to explore whether the migration flow translated to a significant effect on the number of homosexuals by state, suggests that the increase after the legalization of same-sex marriage was transitory. Legalization of same-sex marriage also reduces the incentives for non-US-native individuals originating from intolerant countries to move to a state that permits same-sex marriage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The term homosexual refers to gays and lesbians in this study.

We want to thank a referee for this interesting suggestion.

Using methodologies quite similar to that presented here, we have found several papers that examine the role of law reforms on different outcomes. For example, some researchers focus their attention on the impact of divorce law reforms on divorce rates (Wolfers 2006; González-Val and Marcén 2012), fertility rates (Bellido and Marcén 2014), marriage rates (Drewianka 2008), and suicide and domestic violence (Stevenson and Wolfers 2006). Other papers have considered the effect of custody law reforms on marriage rates and fertility rates (Halla 2013), economic well-being (Del Boca and Ribero 1998; Allen et al. 2011), and educational attainment (Leo 2008; Nunley and Seals 2011). In all these cases, the empirical approach is based on the exogeneity of the law reforms. We revisit this issue below.

We obtain similar results when accounting for pre-existing differences across states incorporating the interaction between the state-fixed effects and calendar and quadratic calendar time (see Table 2). Results do not vary with/without weights. The intuition behind using weighted least squares is that a positive effect of same-sex marriage legalization in say, California, will carry more weight than a positive effect in New Hampshire (Friedberg 1998).

We omitted respondents for whom sex was allocated by the data administrators to avoid erroneous classification of same-sex households (Hansen et al. 2020).

Not all individuals in the LGBT community are included in the data since we can only identify couples where both individuals are male, or both are identified as female from the ACS. These data consider only a subset of individuals in the LGBT community. We recognize that this is an inherent problem when analyzing same-sex individuals.

We did not consider the effective date of the legislation since the announcement of the legalization of same-sex marriage can also attract homosexuals. Note that we are using annual data, so the differences between the effective date and the date used here are not likely to have an impact on our dataset. In any case, our results are robust to the use of the timing of the effective date of the law instead of using the announcement date. Results are presented in the Appendix, Table 10.

The variation in sample size is due to the fact that in some states all homosexuals identified in some years are gay or lesbian. North Dakota only has gay migrants in some years but not lesbian. Alaska, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming only have lesbian migrants but not gay migrants in some years. Our results are maintained without those states and years in which there are no observations in the microdata about lesbian women or gay men (see column 1 of Table 9 in the Appendix). This can be consequence of a problem of identification of gay/lesbian individuals in some specific state-years because the sample size is quite small in some cases. We prefer to be conservative and run the analysis without the information of those state-years when separating the sample by gender. In any case, we only lost five observations in the gay sample and two in the lesbian sample. Results are maintained if we consider no gay/lesbian migrants in those state-years. We have also run the analysis filling those gaps with linear interpolation and results are maintained (see columns 2 and 3 of Table 9 in the Appendix).

Note that our findings are limited to the use of a sample that only includes individuals living in a same-sex relationship. We recognize that the number of unmarried couples identified in those states without same-sex marriage can be underestimated since homosexuals can be more likely to be living apart to reduce stigma. This could bias our estimates.

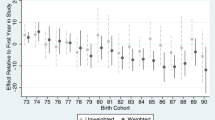

We provided additional evidence that pre-existing trends on homosexual migration are not driving our results by including a dummy variable which takes the value 1 during the periods − 1 and − 2, that is, 1 and 2 years prior to the legalization of the same-sex marriage. Results are reported in Table 10 in the Appendix where it is observed that the pre-same-sex marriage coefficient is not statistically significant. Thus, it appears that our results are not simply the continuation of prior patterns. We also re-ran our main analysis by limiting the sample to those states that legalized same-sex marriage via a judicial decision (Hansen et al. 2020), since this implementation may be less likely to be predicted. Note that these results should be taken with caution due to the scarcity of observations after this limitation of the sample. In any case, we find evidence of a positive and significant impact on the migration of gay men, which is in line with all our findings.

Note that the scarcity of observations can generate concerns on the validity of our estimates after the inclusion of all these additional controls. For this reason, the analysis is presented without those state-specific trends.

We have re-run these specifications including each of these additional controls separately, and the results did not vary.

Note that all same-sex couples who reported being married were recoded to unmarried cohabiting partners until 2013. Thus, the addition of married individuals to the sample only captured married individuals from 2013 to 2015 (https://usa.ipums.org/usa-action/variables/MARST#editing_procedure_section).

The coefficient picking up the effect 1–2 years is positive and different from zero although non-statistically significant, which may indicate that this is more imprecisely estimated.

Unfortunately, we cannot re-run the analysis considering migration between each pair of states due to the scarcity of observations to obtain reliable estimations.

Results on the impact of these legislations should be taken with caution, since in some cases the dates of the reforms are quite close and even coincide. In any case, we have repeated the analysis including each legislation at a time and our results have not changed substantially. We recognize that the estimated coefficients after 5 to 6 years of same-sex marriage legalization appear to be more imprecisely estimated, albeit positive.

Homosexuals appear to earn less than their heterosexual counterparts in the USA and in other countries (Ahmed and Hammarstedt 2010; Badgett 1995; Clain and Leppel 2001; Grossbard and Jensen 2008), generating budget constraints to move to a more distant state, because the greater the physical distance, the higher the migration costs (Belot and Hatton 2012; Bellido and Marcén 2015). Although this is mainly only observed for gay men (Drydakis 2012) and not for lesbian women who are found to earn more than heterosexual women (Klawitter 2015). However, the opposite could be possible. With low wages, opportunity costs would be lower for homosexuals, encouraging migration for homosexuals. Also, since homosexual households are less likely to have children, this reduces over a lifetime the necessities of some household resources (Black et al. 2002; Grossbard and Jensen 2008), which can make them free in the migration process. Our preliminary results, controlling for the possible effect of physical distance, do not alter our findings. We do not include these here because, as suggested by a referee, this is not surprising.

We want to thank a referee for this interesting suggestion.

Same-sex marriage can increase cohabitation/marriage among state residents in addition to migration. Therefore, these results cannot be completely attributed to the effect of migration. Note again that here we are considering a subset of individuals of the LGBT community: individuals in same-sex couples. We can only identify this subset in the ACS. According to the School of Law Williams Institute (UCLA), the total same-sex couples were 646,500 (1.3 million individuals) which represent around 0.4% of the US population in 2010 (https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/visualization/lgbt-stats/?topic=SS#density). This is quite close to the mean of the number of homosexuals obtained in our sample (0.42% for the entire period; see Table 6).

Note that the pattern of homophobic behavior appears to persist over time across countries (Chang 2020).

References

Ahmed AM, Hammarstedt M (2010) Sexual orientation and earnings: a register data-based approach to identify homosexuals. J Popul Econ 23(3):835–849

Allen BD, Nunley JM, Seals A (2011) The effect of joint-child-custody legislation on the child-support receipt of single mothers. J Fam Econ Iss 32(1):124–139

Badgett ML (1995) The wage effects of sexual orientation discrimination. Ind Labor Relat Rev 48(4):726–739

Badgett MV (2009) The economic value of marriage for same-sex couples. Drake Law Rev 58:1081

Beaudin L (2017) Marriage equality and interstate migration. Appl Econ 49(30):2956–2973

Becker G (1973) A theory of marriage: Part I. J Polit Econ 81(4):813–846

Bellido H, Marcén M (2014) Divorce laws and fertility. Labour Econ 27:56–70

Bellido H, Marcén M (2015) Spaniards in the wider World, MPRA Paper 63966. University Library of Munich, Germany

Belot MV, Hatton TJ (2012) Immigrant selection in the OECD. Scand J Econ 114(4):1105–1128

Black D, Gates G, Sanders S, Taylor L (2002) Why do gay men live in San Francisco? J Urban Econ 51(1):54–76

Black DA, Sanders SG, Taylor LJ (2007) The economics of lesbian and gay families. J Econ Perspect 21(2):53–70

Borghans L, Golsteyn BH (2012) Job mobility in Europe, Japan and the United States. Br J Ind Relat 50(3):436–456

Bureau of Labor and Statistics (2018) Labor market activity, education, and partner status among Americans at age 31: results from a longitudinal survey. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/nlsyth.pdf. Accessed Dec 2020

Chang S (2020) The sex ratio and global sodomy law reform in the post-WWII era. J Popul Econ:1–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-020-00773-7

Clain SH, Leppel K (2001) An investigation into sexual orientation discrimination as an explanation for wage differences. Appl Econ 33(1):37–47

Davies PS, Greenwood MJ, Li H (2001) A conditional logit approach to US state-to-state migration. J Reg Sci 41(2):337–360

Del Boca D, Ribero R (1998) Transfers in non-intact households. Struct Chang Econ Dyn 9(4):469–478

Dillender M (2014) The death of marriage? The effects of new forms of legal recognition on marriage rates in the United States. Demography 51(2):563–585

Drewianka S (2008) Divorce law and family formation. J Popul Econ 21(2):485–503

Drydakis N (2011) Women’s sexual orientation and labor market outcomes in Greece. Fem Econ 17(1):89–117

Drydakis N (2012) Sexual orientation and labour relations: new evidence from Athens, Greece. Appl Econ 44(20):2653–2665

Drydakis N (2019) Sexual orientation and labor market outcomes. IZA World of Labor. https://doi.org/10.15185/izawol.111.v2

Enchautegui ME (1997) Welfare payments and other economic determinants of female migration. J Labor Econ 15(3):529–554. https://doi.org/10.1086/209871

Fiva JH (2009) Does welfare policy affect residential choices? An empirical investigation accounting for policy endogeneity. J Public Econ 93:529–540

Francis AM, Mialon HM, Peng H (2012) In sickness and in health: Same-sex marriage laws and sexually transmitted infections. Soc Sci Med 75(8):1329–1341

Friedberg L (1998) Did unilateral divorce raise divorce rates? Evidence from panel data. Am Econ Rev 88(3):608–627

Gelbach JB (2004) Migration, the life cycle, and state benefits: how low is the bottom? J Polit Econ 112(5):1091–1130

Gerstmann E (2017) Same-sex marriage and the constitution. In: Same-Sex Marriage and the Constitution. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp I–Ii

Gius M (2011) The effect of income taxes on interstate migration: an analysis by age and race. Ann Reg Sci 46(1):205–218

González-Val R, Marcén M (2012) Unilateral divorce versus child custody and child support in the U.S. J Econ Behav Organ 81(2):613–643

Goodridge v. Department of Public Health 440 Mass. 309, 798 N.E. 2d 941 (2003)

Greenwood MJ (1997) Internal migration in developed countries. Handb Popul Fam Econ 1:647–720

Grossbard S, Jepsen LK (2008) The economics of gay and lesbian couples: introduction to a special issue on gay and lesbian households. Rev Econ Househ 6(4):311–325

Gurak DT, Kritz MM (2000) The interstate migration of US immigrants: individual and contextual determinants. Soc Forces 78(3):1017–1039

Halla M (2013) The effect of joint custody on family outcomes. J Eur Econ Assoc 11(2):278–315

Hamermesh DS, Delhommer S (2020) Same-sex couples and the marital surplus: the importance of the legal environment, (No. w26875). National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working paper series

Hansen ME, Martell ME, Roncolato L (2020) A labor of love: the impact of same-sex marriage on labor supply. Rev Econ Househ 18:265–283

Hatzenbuehler ML, O'Cleirigh C, Grasso C, Mayer K, Safren S, Bradford J (2012) Effect of same-sex marriage laws on health care use and expenditures in sexual minority men: a quasi-natural experiment. Am J Public Health 102(2):285–291

ILGA World (2019) International lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersex association: Lucas Ramon Mendos. State-Sponsored Homophobia, Geneva

Kane M (2003) Social movement policy success: decriminalizing state sodomy laws, 1969–1998. Mobilization 8(3):313–334

Klawitter M (2015) Meta-analysis of the effects of sexual orientation on earnings. Ind Relat 54(1):4–32

Langbein L, Yost MA (2009) Same-sex marriage and negative externalities. Soc Sci Q 90(2):292–308

Leo TW (2008) From maternal preference to joint custody: the impact of changes in custody law on child educational attainment, Working Paper

Long L, Tucker CJ, Urton WL (1988) Migration distances: an international comparison. Demography 25(4):633–640

Lucas RE (2001) The effects of proximity and transportation on developing country population migrations. J Econ Geogr 1(3):323–339

Mayda AM (2010) International migration: a panel data analysis of the determinants of bilateral flows. J Popul Econ 23(4):1249–1274

McKinnish T (2005) Importing the poor welfare magnetism and cross-border welfare migration. J Hum Resour 40(1):57–76

McKinnish T (2007) Welfare-induced migration at state borders: new evidence from micro-data. J Public Econ 91(3):437–450

Movement Advancement Project (2019) Non-discrimination laws. https://www.lgbtmap.org/equality-maps/non_discrimination_laws. Accessed Dec 2020

Negrusa B, Oreffice S (2011) Sexual orientation and household financial decisions: evidence from couples in the United States. Rev Econ Househ 9(4):445

Nunley JM, Seals RA (2011) Child-custody reform, marital investment in children, and the labor supply of married mothers. Labour Econ 18(1):14–24

Obergefell vs. Hodges, 576 U.S. (no. 14-556), 2015 WL 2473451

Ocobock A (2013) The power and limits of marriage: married gay men’s family relationships. J Marriage Fam 75(1):191–205

Patacchini E, Ragusa G, Zenou Y (2015) Unexplored dimensions of discrimination in Europe: homosexuality and physical appearance. J Popul Econ 28(4):1045–1073

Pinello DR (2016) America’s war on same-sex couples and their families: and how the courts rescued them. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316402351

Plug E, Berkhout P (2004) Effects of sexual preferences on earnings in the Netherlands. J Popul Econ 17(1):117–131

Rogers A, Raymer J (1998) The spatial focus of US interstate migration flows. Popul Space Place 4(1):63–80

Ruggles S, Genadek K, Goeken R, Grover J, Sobek M (2018) Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 7.0 [Machine-readable database]. University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. https://doi.org/10.18128/D010.V8.0

Stevenson B, Wolfers J (2006) Bargaining in the shadow of the law: divorce laws and family distress. Q J Econ 121(1):267–288

Trandafir M (2015) Legal recognition of same-sex couples and family formation. Demography 52(1):113–151

Vossen D, Sternberg R, Alfken C (2019) Internal migration of the “creative class” in Germany. Reg Stud 53(10):1359–1370

Wolfers J (2006) Did unilateral divorce laws raise divorce rates? A reconciliation and new results. Am Econ Rev 96(5):1802–1820

Acknowledgements

This article has benefited from comments provided by Professor Klaus F. Zimmermann and five anonymous referees.

Funding

This research has been funded by the Regional Government of Aragon and the European Fund of Regional Development (Grant S32_20R).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Responsible editor: Klaus F. Zimmermann

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marcén, M., Morales, M. The effect of same-sex marriage legalization on interstate migration in the USA. J Popul Econ 35, 441–469 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-021-00842-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-021-00842-5