Abstract

Objective

The goal of the present study was to extend the findings of the dual-hormone hypothesis (DHH) literature by assessing whether the interaction between testosterone (T) and cortisol (C) is associated with dominance in an adolescent sample via multiple methods of measuring T, C, and dominance, and with pre-registration of hypotheses and analyses.

Methods

In a sample of 337 adolescents (Mage = 14.98, SD = 1.51; 191 girls) and their caregivers, hormonal assays were obtained from hair and saliva, and dominance behavior was assessed across four operationalizations (behavioral ratings in a leadership task, self- and caregiver reported dominance motivations, and self-reported social potency).

Results

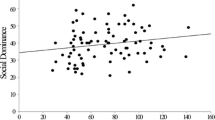

T and C main effects were generally null across hormone and dominance operationalizations, except that observer-rated dominance was negatively associated with salivary T, and social potency was positively associated with salivary T and negatively associated with salivary C. Support for the DHH was weak. Point estimates reflected a small negative T × C interaction for behavioral ratings of dominance, consistent with the DHH, whereas interaction effects for report-based dominance measures were close to zero or positive.

Conclusions

The results contribute to a growing evidence base suggesting T × C interaction effects are variable across measures and methods used to assess hormones and dominance and highlight the need for comprehensive, multi-method examinations employing best practices in scientific openness and transparency to reduce uncertainty in estimates. Measurement of hormones and dominance outcomes vary across labs and studies, and the largely null results should be considered in that context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

19 August 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40750-021-00171-7

Notes

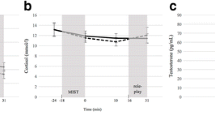

Procedures for the present study included the Trier Social Stress Test (Kirschbaum et al., 1993), a task that reliably elicits an acute increase in C levels. Inclusion of this task is a theoretically-relevant potential moderator of dual-hormone effects, as acute C responses (rather than basal C) may moderate the association between T and status-seeking behavior in stress conditions (Prasad et al., 2017; Prasad, Knight, et al., 2019a, 2019b). However, in the present study, the stress-induction task occurred approximately 1.25–1.5 h before the leadership task, which allowed sufficient time for cortisol levels to return to baseline. This time also included a 15-min break during which participants enjoyed self-guided relaxation. C levels at the time of the final saliva sample (M = 7.68, SD = 7.92), which was collected approximately 15 min before the leadership task, were slightly lower than baseline (i.e., averaged T1 and T2) C levels (M = 9.01, SD = 11.20; t(262) = 3.47, 95% CI [0.54, 1.95]). T levels at the time of the final saliva sample (M = 29.23, SD = 38.12) were not significantly different than baseline T levels (M = 31.91, SD = 44.88; t(262) = 1.39, 95% CI [-1.11, 6.43]).

Fifty-one different examiners and 61 different followers were used.

While our leadership task was modeled after that used in Mehta and Josephs (2010) Study 1, there were important differences, including age and gender differences in leader and follower in the present study and fewer designs completed. Further, while participants were explicitly told they would be judged on leadership ability, they were not explicitly told their leadership skills would be compared to other participants.

References

Adam, E. K., & Kumari, M. (2009). Assessing salivary cortisol in large-scale, epidemiological research. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 34(10), 1423–1436.

Archer, J. (2006). Testosterone and human aggression: an evaluation of the challenge hypothesis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 30(3), 319–345.

Archer, J., Graham-Kevan, N., & Davies, M. (2005). Testosterone and aggression: A reanalysis of Book, Starzyk, and Quinsey’s (2001) study. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 10(2), 241–261.

Bakker, M., Hartgerink, C. H., Wicherts, J. M., & van der Maas, H. L. (2016). Researchers’ intuitions about power in psychological research. Psychological Science, 27(8), 1069–1077.

Blake, K. R., & Gangestad, S. (2020). On attenuated interactions, measurement error, and statistical power: Guidelines for social and personality psychologists. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46(12), 1702–1711.

Book, A. S., Starzyk, K. B., & Quinsey, V. L. (2001). The relationship between testosterone and aggression: A meta-analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 6(6), 579–599.

Brown, L. L., Tomarken, A. J., Orth, D. N., Loosen, P. T., Kalin, N. H., & Davidson, R. J. (1996). Individual differences in repressive-defensiveness predict basal salivary cortisol levels. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(2), 362.

Burnstein, K. L., Maiorino, C. A., Dai, J. L., & Cameron, D. J. (1995). Androgen and glucocorticoid regulation of androgen receptor cDNA expression. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 115(2), 177–186.

Carré, J. M., & Archer, J. (2018). Testosterone and human behavior: the role of individual and contextual variables. Current Opinion in Psychology, 19, 149–153.

Carré, J. M., & McCormick, C. M. (2008). Aggressive behavior and change in salivary testosterone concentrations predict willingness to engage in a competitive task. Hormones and Behavior, 54(3), 403–409.

Cassidy, T., & Lynn, R. (1989). A multifactorial approach to achievement motivation: The development of a comprehensive measure. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 62(4), 301–312.

Casto, K. V., Hamilton, D. K., & Edwards, D. A. (2019). Testosterone and cortisol interact to predict within-team social status hierarchy among Olympic-level women athletes. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology, 5(3), 237–250.

Chen, S. Y., Wang, J., Yu, G. Q., Liu, W., & Pearce, D. (1997). Androgen and glucocorticoid receptor heterodimer formation a possible mechanism for mutual inhibition of transcriptional activity. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 272(22), 14087–14092.

Cronbach, L. J., & Meehl, P. E. (1955). Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin, 52(4), 281.

Dabbs, J. M., Jurkovic, G. J., & Frady, R. L. (1991). Salivary testosterone and cortisol among late adolescent male offenders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 19(4), 469–478.

Dekkers, T. J., van Rentergem, J. A. A., Meijer, B., Popma, A., Wagemaker, E., & Huizenga, H. M. (2019). A meta-analytical evaluation of the dual-hormone hypothesis: Does cortisol moderate the relationship between testosterone and status, dominance, risk taking, aggression, and psychopathy? Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 96, 250–271.

Denson, T. F., Spanovic, M., & Miller, N. (2009). Cognitive appraisals and emotions predict cortisol and immune responses: A meta-analysis of acute laboratory social stressors and emotion inductions. Psychological Bulletin, 135(6), 823.

Dickerson, S. S., & Kemeny, M. E. (2004). Acute stressors and cortisol responses: A theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychological Bulletin, 130(3), 35.

Edwards, D. A., & Casto, K. V. (2013). Women’s intercollegiate athletic competition: Cortisol, testosterone, and the dual-hormone hypothesis as it relates to status among teammates. Hormones and Behavior, 64(1), 153–160.

El-Farhan, N., Rees, D. A., & Evans, C. (2017). Measuring cortisol in serum, urine and saliva–are our assays good enough? Annals of Clinical Biochemistry, 54(3), 308–322.

Field, H. P. (2013). Tandem mass spectrometry in hormone measurement. In M. J. Wheeler (Ed.), Hormone Assays in Biological Fluids. (pp. 45–74). Humana Press.

Flake, J. K., Pek, J., & Hehman, E. (2017). Construct validation in social and personality research: Current practice and recommendations. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(4), 370–378.

Franco, A., Malhotra, N., & Simonovits, G. (2014). Publication bias in the social sciences: Unlocking the file drawer. Science, 345(6203), 1502–1505.

Gao, W., Stalder, T., Foley, P., Rauh, M., Deng, H., & Kirschbaum, C. (2013). Quantitative analysis of steroid hormones in human hair using a column-switching LC–APCI–MS/MS assay. Journal of Chromatography B, 928, 1–8.

Geniole, S. N., Busseri, M. A., & McCormick, C. M. (2013). Testosterone dynamics and psychopathic personality traits independently predict antagonistic behavior towards the perceived loser of a competitive interaction. Hormones and Behavior, 64(5), 790–798.

Geniole, S. N., Carré, J. M., & McCormick, C. M. (2011). State, not trait, neuroendocrine function predicts costly reactive aggression in men after social exclusion and inclusion. Biological Psychology, 87(1), 137–145.

Geniole, S. N., Procyshyn, T. L., Marley, N., Ortiz, T. L., Bird, B. M., Marcellus, A. L., Welker, K. M., Bonin, P. L., Goldfarb, B., Watson, N. V., & Carré, J. M. (2019). Using a psychopharmacogenetic approach to identify the pathways through which—and the people for whom—testosterone promotes aggression. Psychological Science, 30(4), 481–494.

Goldsmith, H. H., & Lemery, K. S. (2000). Linking temperamental fearfulness and anxiety symptoms: A behavior–genetic perspective. Biological Psychiatry, 48(12), 1199–1209.

Grahek, I., Schaller, M., & Tackett, J. L. (in press). Anatomy of a psychological theory: Integrating construct validation and computational modeling methods to advance theorizing. Perspectives on Psychological Science.

Grebe, N. M., Del Giudice, M., Emery Thompson, M., Nickels, N., Ponzi, D., Zilioli, S., Maestripieri, D., & Gangestad, S. W. (2019). Testosterone, cortisol, and status-striving personality features: A review and empirical evaluation of the Dual Hormone hypothesis. Hormones and Behavior, 109, 25–37.

Grotzinger, A. D., Mann, F. D., Patterson, M. W., Tackett, J. L., Tucker-Drob, E. M., & Harden, K. P. (2018). Hair and salivary testosterone, hair cortisol, and externalizing behaviors in adolescents. Psychological Science, 29(5), 688–699.

Harden, K. P., Wrzus, C., Luong, G., Grotzinger, A., Bajbouj, M., Rauers, A., Wagner, G. G., & Riediger, M. (2016). Diurnal coupling between testosterone and cortisol from adolescence to older adulthood. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 73, 79–90.

Holm, S. (1979). A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics, 6(2), 65–70.

Johnson, E. O., Kamilaris, T. C., Chrousos, G. P., & Gold, P. W. (1992). Mechanisms of stress: A dynamic overview of hormonal and behavioral homeostasis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 16(2), 115–130.

Kirschbaum, C., & Hellhammer, D. (1994). Salivary cortisol in psychoneuroendocrine research: Recent developments and applications. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 19(4), 313–333.

Kirschbaum, C., Pirke, K. M., & Hellhammer, D. H. (1993). The ‘Trier Social Stress Test’–a tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology, 28(1–2), 76–81.

Knight, E. L., Sarkar, A., Prasad, S., & Mehta, P. H. (2020). Beyond the challenge hypothesis: The emergence of the dual-hormone hypothesis and recommendations for future research. Hormones and Behavior, 104657.

Kordsmeyer, T. L., & Penke, L. (2019). Effects of male testosterone and its interaction with cortisol on self-and observer-rated personality states in a competitive mating context. Journal of Research in Personality, 78, 76–92.

Lahey, B. B., Applegate, B., Waldman, I. D., Loft, J. D., Hankin, B. L., & Rick, J. (2004). The structure of child and adolescent psychopathology: Generating new hypotheses. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113(3), 358–385.

Lausen, A., Broering, C., Penke, L., & Schacht, A. (2020). Hormonal and modality specific effects on males’ emotion recognition ability. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 119, 104719.

Liening, S. H., Stanton, S. J., Saini, E. K., & Schultheiss, O. C. (2010). Salivary testosterone, cortisol, and progesterone: Two-week stability, interhormone correlations, and effects of time of day, menstrual cycle, and oral contraceptive use on steroid hormone levels. Physiology & Behavior, 99(1), 8–16.

Mehta, P. H., Jones, A. C., & Josephs, R. A. (2008). The social endocrinology of dominance: Basal testosterone predicts cortisol changes and behavior following victory and defeat. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(6), 1078.

Mehta, P. H., & Josephs, R. A. (2006). Testosterone change after losing predicts the decision to compete again. Hormones and Behavior, 50(5), 684–692.

Mehta, P. H., & Josephs, R. A. (2010). Testosterone and cortisol jointly regulate dominance: Evidence for a dual-hormone hypothesis. Hormones and Behavior, 58(5), 898–906.

Mehta, P. H., & Prasad, S. (2015). The dual-hormone hypothesis: A brief review and future research agenda. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 3, 163–168.

Mehta, P. H., Welker, K. M., Zilioli, S., & Carré, J. M. (2015). Testosterone and cortisol jointly modulate risk-taking. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 56, 88–99.

Nosek, B. A., Ebersole, C. R., DeHaven, A. C., & Mellor, D. T. (2018). The preregistration revolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(11), 2600–2606.

Oyegbile, T. O., & Marler, C. A. (2005). Winning fights elevates testosterone levels in California mice and enhances future ability to win fights. Hormones and Behavior, 48(3), 259–267.

Patrick, C. J., Curtin, J. J., & Tellegen, A. (2002). Development and validation of a brief form of the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 14(2), 150.

Petersen, A. C., Crockett, L., Richards, M., & Boxer, A. (1988). A self-report measure of pubertal status: Reliability, validity, and initial norms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 17(2), 117–133.

Pfattheicher, S. (2017). Illuminating the dual-hormone hypothesis: About chronic dominance and the interaction of cortisol and testosterone. Aggressive Behavior, 43(1), 85–92.

Pfattheicher, S., Landhäußer, A., & Keller, J. (2014). Individual differences in antisocial punishment in public goods situations: The interplay of cortisol with testosterone and dominance. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 27(4), 340–348.

Platje, E., Popma, A., Vermeiren, R. R., Doreleijers, T. A., Meeus, W. H., van Lier, P. A., Koot, H. M., Branje, S. J. T., & Jansen, L. M. (2015). Testosterone and cortisol in relation to aggression in a non-clinical sample of boys and girls. Aggressive Behavior, 41(5), 478–487.

Popma, A., Vermeiren, R., Geluk, C. A., Rinne, T., van den Brink, W., Knol, D. L., Jansen, L. M. C., van Engeland, H., & Doreleijers, T. A. (2007). Cortisol moderates the relationship between testosterone and aggression in delinquent male adolescents. Biological Psychiatry, 61(3), 405–411.

Ponzi, D., Zilioli, S., Mehta, P. H., Maslov, A., & Watson, N. V. (2016). Social network centrality and hormones: The interaction of testosterone and cortisol. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 68, 6–13.

Prasad, S., Knight, E. L., & Mehta, P. H. (2019). Basal testosterone’s relationship with dictator game decision-making depends on cortisol reactivity to acute stress: A dual-hormone perspective on dominant behavior during resource allocation. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 101, 150–159.

Prasad, S., Lassetter, B., Welker, K. M., & Mehta, P. H. (2019). Unstable correspondence between salivary testosterone measured with enzyme immunoassays and tandem mass spectrometry. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 109, 104373.

Prasad, S., Narayanan, J., Lim, V. K., Koh, G. C., Koh, D. S., & Mehta, P. H. (2017). Preliminary evidence that acute stress moderates basal testosterone’s association with retaliatory behavior. Hormones and behavior, 92, 128–140.

Reitan, R. M. (1992). Trail Making Test: Manual for administration and scoring. Reitan Neuropsychology Laboratory.

Roelofs, K., van Peer, J., Berretty, E., de Jong, P., Spinhoven, P., & Elzinga, B. M. (2009). Hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis hyperresponsiveness is associated with increased social avoidance behavior in social phobia. Biological Psychiatry, 65(4), 336–343.

Ronay, R., van der Meij, L., Oostrom, J. K., & Pollet, T. V. (2018). No evidence for a relationship between hair testosterone concentrations and 2D: 4D ratio or risk taking. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 12, 30.

Rubinow, D. R., & Schmidt, P. J. (1996). Androgens, brain, and behavior. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 153(8), 974–984.

Ruttle, P. L., Shirtcliff, E. A., Armstrong, J. M., Klein, M. H., & Essex, M. J. (2015). Neuroendocrine coupling across adolescence and the longitudinal influence of early life stress. Developmental Psychobiology, 57(6), 688–704.

Sarkar, A., Mehta, P. H., & Josephs, R. A. (2019). The dual-hormone approach to dominance and status-seeking. In O. C. Schultheiss & P. H. Mehta (Eds.), Routledge International Handbook of Social Neuroendocrinology. (1st ed., pp. 113–132). Routledge.

Schild, C., Aung, T., Kordsmeyer, T. L., Cardenas, R. A., Puts, D. A., & Penke, L. (2020). Linking human male vocal parameters to perceptions, body morphology, strength and hormonal profiles in contexts of sexual selection. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 1–16.

Schulkin, J., Gold, P. W., & McEwen, B. S. (1998). Induction of corticotropin-releasing hormone gene expression by glucocorticoids: Implication for understanding the states of fear and anxiety and allostatic load. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 23(3), 219–243.

Schultheiss, O.C. & Stanton, S.J. (2009). Assessment of salivary hormones. In E. Harmon-Jones & J.S. Beer (Eds.), Methods in social neuroscience (pp. 17–44). Guilford Publications.

Sherman, G. D., Lerner, J. S., Josephs, R. A., Renshon, J., & Gross, J. J. (2016). The interaction of testosterone and cortisol is associated with attained status in male executives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 110(6), 921.

Shirtcliff, E. A., Dahl, R. E., & Pollak, S. D. (2009). Pubertal development: correspondence between hormonal and physical development. Child Development, 80(2), 327–337.

Simmons, J. P., Nelson, L. D., & Simonsohn, U. (2011). False-positive psychology: Undisclosed flexibility in data collection and analysis allows presenting anything as significant. Psychological Science, 22(11), 1359–1366.

Stalder, T., Steudte, S., Miller, R., Skoluda, N., Dettenborn, L., & Kirschbaum, C. (2012). Intraindividual stability of hair cortisol concentrations. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37(5), 602–610.

Tackett, J. L., Herzhoff, K., Harden, K. P., Page-Gould, E., & Josephs, R. A. (2014). Personality× hormone interactions in adolescent externalizing psychopathology. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 5(3), 235.

Taylor, S. E., Klein, L. C., Lewis, B. P., Gruenewald, T. L., Gurung, R. A., & Updegraff, J. A. (2000). Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychological Review, 107(3), 411.

Tellegen, A. (1982). Brief manual for the multidimensional personality questionnaire. Unpublished manuscript, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, 1031–1010.

Tilbrook, A. J., Turner, A. I., & Clarke, I. J. (2000). Effects of stress on reproduction in non-rodent mammals: The role of glucocorticoids and sex differences. Reviews of Reproduction, 5(2), 105–113.

Van Den Bos, W., Golka, P., Effelsberg, D., & McClure, S. (2013). Pyrrhic victories: The need for social status drives costly competitive behavior. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 7, 189.

van Honk, J., Schutter, D. J., Hermans, E. J., Putman, P., Tuiten, A., & Koppeschaar, H. (2004). Testosterone shifts the balance between sensitivity for punishment and reward in healthy young women. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 29(7), 937–943.

Viau, V. (2002). Functional cross-talk between the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal and-adrenal axes. Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 14(6), 506–513.

Wechsler, D. (2008). Wechsler adult intelligence scale–Fourth Edition (WAIS–IV). NCS Pearson.

Welker, K. M., Lassetter, B., Brandes, C. M., Prasad, S., Koop, D. R., & Mehta, P. H. (2016). A comparison of salivary testosterone measurement using immunoassays and tandem mass spectrometry. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 71, 180–188.

Welker, K. M., Lozoya, E., Campbell, J. A., Neumann, C. S., & Carré, J. M. (2014). Testosterone, cortisol, and psychopathic traits in men and women. Physiology & Behavior, 129, 230–236.

Williams, R. H., & Zimmerman, D. W. (1989). Statistical power analysis and reliability of measurement. The Journal of General Psychology, 116(4), 359–369.

Wingfield, J. C., Hegner, R. E., Dufty, A. M., Jr., & Ball, G. F. (1990). The “challenge hypothesis": Theoretical implications for patterns of testosterone secretion, mating systems, and breeding strategies. The American Naturalist, 136(6), 829–846.

Zhang, Q., Chen, Z., Chen, S., Yu, T., Wang, J., Wang, W., & Deng, H. (2018). Correlations of hair level with salivary level in cortisol and cortisone. Life Sciences, 193, 57–63.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shields, A.N., Brandes, C.M., Reardon, K.W. et al. Do Testosterone and Cortisol Jointly Relate to Adolescent Dominance? A Pre-registered Multi-method Interrogation of the Dual-Hormone Hypothesis. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology 7, 183–208 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40750-021-00167-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40750-021-00167-3