Abstract

This paper investigates consumption patterns in digital subscription-based streaming services for books by means of a large-scale dataset derived from Storytel. The aim is twofold: to empirically discuss how book consumption in the commercial top segment diverges between print books and digital streaming platforms, and to conceptually show the usefulness and considerable possibilities with computational approaches for digital publishing studies and contemporary book history. This is accomplished by introducing the concept of the beststreamer, and the average finishing degree measure. The empirical output shows large differences between print bestsellers and digital beststreamers, both in terms of genre distributions, finished streams, and levels of completion. These results are discussed in relation to factors fostering consumption patterns, such as platform design, pricing models, supply, marketing, customer base, and media-specific features of the audiobook.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Streaming services for audiobooks and e-books have grown rapidly in recent years in many book markets across the globe [1,2,3,4]. This ongoing shift in how books are consumed is transforming reading and publishing [5], but also the possibilities for studying reading and publishing. As Karl Berglund and Ann Steiner have argued, digital methods constitute “a necessary update of the book history toolbox in studying book consumption. A digital book trade needs digital methods to be studied adequately” [6]. Access to large-scale data points on real-time book consumption behavior enables scholars to answer questions that could only be speculated about earlier: Which books are readers most (and least) likely to finish? Where do readers drop out in narratives? When (which hours of the day, which days of the week) are books consumed the most?

This paper zooms in on the first of these questions by introducing two concepts for publishing studies that are empirically grounded in digital book consumption at scale. The first is the concept of the beststreamer. In the most obvious respect, it works analogue to the bestseller, thus being the books that have been streamed the most in a particular region and period of time; in the era of subscription-based streaming services that equates with the digital bestsellers, more or less. Although popularity in streaming services is increasingly important if one seeks to map contemporary book consumption at large, beststreaming numbers should not, however, be understood as separated from bestseller numbers. On the contrary, the beststreamer plays down the often-claimed opposition between print and digital consumption as titles popular in streaming services are often also popular in print. As the analysis will show, bestsellers and beststreamers both converge and depart. In this respect, the beststreamer concept takes Simone Murray’s [7] claim that “[a]nalysts of the contemporary book world thus need to cease conceptualising the analogue and digital as ontological opposites and instead examine the two domains’ complex patterns of coexistence” (2) seriously, and offers a way to concretely achieve this.

Furthermore, the beststreamer has a second dimension, as it measures actual consumption of books, i.e. streaming rates: started streams and finished streams as well as, potentially, any level of completion between these two outer delimiters. The beststreamer thus unites publishing and readership studies and provides a measurement of impact based on consumption and not, as earlier book history metrics, based on book sales or library lending. As is commonly known, not all books that are bought are read. Finished streams is therefore a much more accurate metric to track consumption in the sense of reading books instead of merely in the sense of buying (or lending) books.

To make use of the more nuanced information available in the streaming data, I introduce the concept of the average finishing degree (AFD), which equals the number of finished streams of a title in a streaming-service platform divided by the number of started streams of the same title. This measurement is powerful in its simplicity, and it enables a fresh approach to the study of book popularity. Instead of counting popularity only in terms of books sold or streams finished, AFD also lets the scholar measure things such as readerly devotion and books’ ability to absorb their readers. The AFD thereby avoids binaries and moves closer to real reading patterns. It should also be regarded as a starting point for further, more fine-grained approaches to digital book consumption.

The purpose of the paper is to showcase the utility of these two concepts—the principal beststreamer, and the more operative AFD—for publishing studies, contemporary book history and sociology of literature by putting them to empirical use on a large-scale digital material, more precisely consumer-behavior data from Storytel, one of the key players in subscription-based digital bookselling outside of the Anglophone countries. The focus of this paper is thus twofold and covers conceptual and methodological development for digital publishing studies as well as empirical results on patterns for book consumption in subscription-based streaming services. This can be broken down into the following concrete research questions:

-

How do beststreamers differ—conceptually and empirically—from bestsellers? What do streaming rates reveal about book consumption in the more commercial segments of the trade?

-

What can the AFD metric reveal about consumption patterns of digital books? Which books, genres, and authorships are readers most (and least) likely to finish, and how can such results be understood?

-

How can beststreamers, AFDs, and other digital approaches inform publishing studies and contemporary book history? How can output derived from large-scale datasets be critically discussed and contextually examined?

Method and Material

As stated, the empirical point of departure is consumer behavior data from Storytel, a streaming platform for audiobooks and ebooks currently launched in 21 national book markets across the globe, including countries such as Germany, Spain, Russia, Brazil, and India. The company was founded in Sweden in 2005, where it has its strongest book market position. In 2021, more than half (57%) of the volumes sold on the Swedish market emanated from subscription-based streaming services ([4], 23–24), and in this segment Storytel’s market share is larger than all other platforms combined ([8], 13).

The consumption data cover all Storytel users in Sweden for all works that during the period 2015–2019 have been either a bestseller in print (according to the Swedish Publishers’ Association’s annual lists), a beststreamer on the Storytel platform (according to Storytel data), or both. Storytel has collected finished streams for the whole period studied, but more fine-grained consumption data—including started streams, a metric needed to calculate the AFD—only since October 2018. This means that finished streaming rates are measured January 2015 to April 2020, and AFDs for the shorter period October 2018 to April 2020. Although it is unfortunate that the AFD scores don’t cover the whole period studied, the limitation doesn’t affect the discussion concerning the usefulness of the measure. Taken together, the dataset covers nearly 10 million data point and is composed as shown in Table 1. It covers consumption of both audiobooks and ebooks, but the audiobook format is the absolutely most popular on the platform, with over 90% of the traffic.Footnote 1

Since digital data from commercial actors in the book trade are generally hard to access for researchers, a note on data sharing and access is relevant in this context. The data were made available through a collaborative agreement between Storytel AB and Uppsala University.Footnote 2 The research group gained access to data aggregated per ISBN for the titles of interest for the project. In practice, this means very large CSV files of streaming patterns on the Storytel platform for contemporary bestsellers and beststreamers in Sweden. The data itself is thus aggregated but “raw” (i.e., objective in the same sense as book sales data; it reflects popularity in the Storytel platform), although raw data is indeed a problematic term [9]. With that said, the data points are of course dependent upon the platform’s recommendation algorithms and design in the same manner as print book sales are dependent on book displaying and recommendations in physical and internet book retailing. To empirically investigate which effects these different areas of display and recommendation have is a driving force behind the paper.

With the of help of Python libraries pandas and Matplotlib, this vast dataset has been analyzed, grouped and visualized in several ways. Added to this core data is contextualizing information about the works in question and their authors: metadata, genre categorizations, and other publishing information. The empirical analysis is divided into two parts. In the first, bestsellers and beststreamers are compared and analyzed according to the number of finished streams, that is: popularity in terms of digital book consumption. In the second, a similar comparison is carried out, but now departing from the AFD metric, thus focusing on reader devotion and textual ability to keep up reader interest. In the final section, these two quantitative approaches to digital book consumption are brought together and discussed critically in relation to the fields of publishing studies and contemporary book history.

Debates in Digital Publishing Studies

The new concepts proposed in this paper derive from a deliberate and consequent merging of publishing studies, sociology of literature and contemporary book history, on the one hand, and computational methods and investigations of large-scale digital datasets, on the other. Both these perspectives are necessary to understand the rapid alterations in consumption behavior that mark the book trade of today.

This is obviously not the first discussion of digital perspectives in contemporary publishing. On the contrary, the digitalization of the trade has—naturally—been a standard element in most scholarly work on twenty-first century publishing (see, for instance, [5, 7, 10, 11, 13]). Empirical computational approaches that depart from large-scale dataset to study contemporary book culture are however more uncommon. In a recent survey of publishing studies, Rachel Noorda and Stevie Marsden [13] interestingly make a contrary claim: “twenty-first century book scholars commonly use digital methodologies—such as data scraping or mining, online surveys and computational analysis.” (382) Although there are certainly examples of studies in this vein (research within or bordering computational publishing studies have been carried out by e.g. [6, 14,15,16,17,18]; cf. [12], an overwhelming majority of the studies in the field are qualitative. In addition, prominent scholars have raised criticism toward quantitative perspectives, questioning what large-scale dataset can really prove. In The Digital Literary Sphere (2018), Simone Murray [5] highlights several problems with computational methods. She warns of “an inherent risk of naïve positivism,” of weaknesses in the methods employed, and of the fact that book history scholars might unconsciously internalize a culture of metrics, in a way similar to how actors such as Amazon understand book consumption (151–154). Simon Rowberry [19], relatedly, claims that data collected from digital reading offers a poor substitute for reading, and that it is unclear how the metrics provided relate to the act of reading.

Although Murray’s and Rowberry’s concerns should be taken seriously, they are both mainly problem-oriented and do not thoroughly discuss the inherent possibilities in such methods for publishing studies. It could be added that their objections are in many respects similar to previous criticism in literary studies toward large-scale computational methods, where scholars have warned about positivism (see e.g. [20]), troublesome methods (see e.g. [21]), and metrics and measuring culture per se (see e.g. [22]). Simon Rowberry’s [19] claim that “metrics of consumption […] fail to capture the complete reading process” (237–238) is in many ways analogue to Stephen Marche’s [22] assertion that “literature is not data,” but transferred from literary studies to book history, from literary text to reader behavior.

In the most basic sense, I agree with both Marche and Rowberry: literature is not data; metrics of consumption do fail to capture the complete reading process. However, and focusing on the latter claim, this does not make it less useful as a way to study readership and book consumption on digital platforms. From my perspective, large-scale data points on digital book consumption deriving from commercial actors seem to be one of the more promising operationalizations of reading and book consumption that publishing studies and book history have ever had access to. The keyword here is operationalization, i.e., the transformation of an elusive concept (such as reading) into something concrete that can be studied empirically. Operationalizations are needed in all studies of readers and book consumption, and no single method manages to capture all aspects of what constitutes these things.

Thus, there are certainly limitations to operationalizing reading as finished streams in a digital platform, but as long as one is upfront with these limitations and discuss them critically, data point on book streams can reveal a lot about contemporary book consumption. Furthermore, data derived from the digital streaming platforms themselves makes for a better understanding of how these platforms perform and function. Sales figures enable publishing scholars to see which books have been popular in the sense of sold the most. Similarly, streaming data have the potential of letting scholars see not only which books that have been the most popular in digital streaming services, but also how readers have interacted with these works. Although such measurements are in one respect always crude, they are more nuanced than figures on sales or library lending.

Furthermore, the demarcation line between digital contexts and digital methods proposed by Murray [5] as well as Noorda and Marsden ([13], 382) is problematic. Digital content and digital methods are intertwined, and, from my point of view, the best way to approach streaming platforms is by investigating them on their own terms, in their own habitat. This, however, by no means rules out an uncritical, uninformed or positivist approach to the results found. There is no conflict between computational large-scale methods and a critical perspective based on contextual knowledge (cf. [23, 24]).

Thus, when Noorda and Marsden [13] argue “that long twenty-first century research is in a unique position to use digital texts and contexts, such as websites, ebooks, apps, social media, and audiobooks, to name but a few, in its analysis of contemporary book and publishing culture,” (382) I completely agree, with the addition that most such datasets benefit greatly from computational methods. Similarly, I support Simone Murray’s [5] claim that “what is currently missing and is urgently needed is a digital literary studies that is both contemporary and contextual.” (9) But contrary to Murray I believe critically and contextually informed computational analyses of digital data points at scale to be a feasible way to bridge this knowledge gap. Even though publishing scholars probably never will be able to get a hold of the algorithms that steer consumption behavior in digital platforms, as Murray [7] rightly points out (7), analyzing the outcome of these algorithms in terms of user interaction and consumption patterns appears to be highly relevant and—at the very least—as the second-best alternative. An approach that makes use of consumption data from a book-streaming service provides for a solid understanding of how such consumption data is used by that platform, and what effects it might have regarding the digital framing and consumption of literature.

Moreover, as all recommendation algorithms are based on statistical models that cluster users together based on similarity patterns in consumption and interaction on the platform in question (albeit possibly biased in different ways—such systems can favor the company’s own titles, for instance), the technical details of each individual algorithm might not be the holy grail for publishing studies. “How to account for the power of algorithms when those algorithms are unavailable for scholarly scrutiny, likely in perpetuity?”, Murray asks ([7], p. 14). A basic knowledge of how machine learning recommendation systems operate, paired with a critical mindset towards their output, is probably sufficient for most publishing studies’ research questions. Even though such algorithms are important, one should not exaggerate their importance, as that, contrary to the intentions, might mystify algorithms in the cultural industries even further.

With that said, platform-studies approaches to digital streaming services are crucial for understanding these platforms (cf. [12]). In many respect, the importance of accounting for the materiality of books, stressed by book historians since at least the 1980s, becomes amplified even further when the reading is carried out in digital environments. Such book consumption is material indeed, and this materiality will likely have a large impact on reading habits in the future.

Popularity Seen as Finished Streams

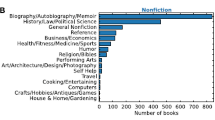

What is then discovered when finished streams are compared for bestsellers and beststreamers? To start with, comparing the titles’ attributed genres reveals important differences. Although bestsellers are a category of books dominated by popular fiction, especially crime fiction, it is nevertheless a mixed category that also contains a significant amount of prestigious and award-winning fiction as well as middlebrow titles. Beststreamers, however, can almost be equated with crime fiction (see Table 2).

If the title-based numbers are transformed into streaming rates, the pattern emerges even more clearly. For the whole dataset, crime fiction constitutes 65% of the titles and 79% of the finished streams, while prestigious fiction constitutes 7% of the titles and 2% of the finished streams (see Tables 2, 3). If we look only at bestsellers in print, prestigious fiction constitutes 15% of the titles, but only 7% of the finished streams.

The outcome shows that crime fiction in the most popular segment is consumed to a notably higher extent in digital streaming services when compared to print sales, and that prestige fiction conversely is consumed to a notably lower extent. The pattern emerges merely from looking at genres at the top of lists for respective platforms and is amplified when finished streams are counted. Thus, there is not only more crime fiction and less literary fiction in the digital charts compared to the print ones—the titles of literary fiction that were bestsellers are consumed less when compared to other bestsellers in print that didn’t made it to the top charts of the streaming platform.

If the finished streams are broken down to individual titles, all top titles are domestic crime fiction, with authors such as David Lagercrantz, Lars Kepler, and Camilla Läckberg in the absolute top. In the bottom, several prize winners end up (e.g., works by Olga Tokarczuk, Hanya Yanagihara, Johannes Anyuru), but even more apparent is the dominance of translated works, including translated popular fiction (by e.g. Anthony Doerr, Armando Lucas Correa, Louise Doughty). If we look at the whole dataset, the bias concerning translations and Swedish originals is apparent. While the distribution is at least fairly balanced among the bestsellers in print (roughly 6 to 4), the Swedish originals constitute around 9 out of 10 of the finished streams both among the beststreamers and the titles popular in both formats (see Table 4).

It is important to stress here that the distribution of finished streams in the beststreamer category resembles the distribution in the category of cross-format popularity, concerning both genres and translations. The data thus seem to suggest that while pure bestsellers in print are a very different category of books compared to beststreamers, the bestsellers that also work well in digital streaming services seem to be more similar to the pure beststreamers. This indicates that bestsellers is a mixed category that contains both highbrow and lowbrow, whereas beststreamers is much more homogeneous, heavily dominated by Swedish popular fiction, especially crime fiction. This pattern is visible even on the metadata level but becomes enhanced and emerges with full power when the point of departure is finished streams, i.e., actual book consumption on the streaming service. If this difference is also reflected on the textual level is yet to be investigated.

Explanations for Differences Between Print and Digital

There are several possible explanations for the outcomes discussed above, and they are likely to be interconnected. One is that digital audiobooks are the driving force behind the vast impact of streaming services and that this is a format best suited for straightforwardly narrated and streamlined popular fiction, while more complex and stylistically advanced prose perform less well. This aspect is frequently highlighted in debates around the rise of streaming services in Sweden, much because it worries advocates of literary fiction. The former CEO of Sweden’s largest publishing house, Bonniers, for instance, has stressed such arguments in a noticed interview [26]. Karl Berglund and Mats Dahllöf [27] have also shown empirically that bestsellers and beststreamers do differ regarding prose style, also beyond genre. Print bestsellers are longer, and syntactically more complex and varied, where popular audiobooks by contrast are shorter, more straightforwardly written and focused on plot and dialogue. Iben Have and Birgitte Stougaard Pedersen [28] claim the opposite, as they argue that audiobooks work equally well for focused listening as for easy-reads and distraction. Even if this might theoretically be true, the data tell a different story, at least concerning the bestselling segment: literary fiction, prestige fiction, and more complex narrative constructs do not manage to attract consumers in streaming services to the same extent as they do with print books.

A second explanation is that the differences between print bestsellers and streaming rates make a previously more invisible distinction between literary consumption in the sense of buying books and in the sense of actually reading them visible. Many people probably recognize themselves in the description of having bought an award-winning book or having received it as a gift, and then letting the book lie, completely or partially unread. This tend to happen because there is an intrinsic value in owning or giving away books by award-winning, prestigious literature, regardless of whether they are read or not. A book by Herta Müller or Olga Tokarczuk in the bookshelf signals education and good taste. Popular literature works differently—if you buy a detective story or a romance novel, you usually do so because you want to read it. When similar behaviors are transferred to a digital streaming services, the difference between genres emerges with brutal clarity: with the status-only consumption of print books taken away, the figures for literary fiction simply plunge. There is no prestige in streaming an audiobook or an e-book that goes beyond what the actual listening or reading provides. In streaming services, consumption of literature is equal to actual streaming. From this perspective, digital streaming services might be regarded as a new low-cost format for books, a digital version of the mass-market paperback.

A third explanation of the homogeneity of the beststreamers might be found in the customer base of the streaming services. In Sweden in the year 2019, only around 10% of all book readers used streaming services on a daily basis, which can be compared to the corresponding number of 34% for printed books ([29], 77). Although both audiobook consumption and streaming services have grown since then, it is still a minority of readers that use streaming services regularly. Thus, it is possible, not to say likely, that the Storytel users are not representative of the book-reading community in Sweden in general. Frequent consumers of literary fiction might prefer reading in print, and consumers of both popular and literary fiction might choose Storytel as a substitute for buying mass-market paperbacks of popular fiction, while sticking with print editions for their literary reads. At the moment, there are unfortunately no data available about possible biases regarding the customer base—the best thing we can do as scholars is to highlight this possible skew and keep a critical mind.

A final explanation relates to the Storytel platform design. Several commentators have discussed how interface design and functionality in digital subscription-based platforms affect and steer consumption behavior, and how the availability of seemingly endless numbers of choices makes readers increasingly dependent on suggestions from recommendation systems (see, for instance, [6, 7, 30, 31]. Similar patterns might be at work here. Storytel and the rapid growth of audiobooks in Sweden in general have been mainly discussed in relation to easy reads, and to books consumed while doing something else (commuting, cleaning, doing the dishes, etc.). This has likely affected Storytel’s customer base, which in turn produces effects in its recommendation systems. If most Swedish Storytel readers consume crime fiction and romantic fiction, such titles will be recommended to a high extent, and placed strategically in the app design in terms of suggested reads and categories. Also, the beststreaming lists themselves might work in a similar fashion, since such rankings are not only a listing of book consumption, but a marketing tool in themselves, attracting more readers to the already-popular titles (see e.g. [32]).Footnote 3

Temporal Patterns and Segmentation

Another viable approach to the finished streaming rates concerns the diachronic perspective, that is, how the different formats for book consumption in the streaming services relate to each other over time. This can be accomplished by means of linear regression, a standard statistical analysis that calculates tendencies among data points.Footnote 4 Such an analysis, based on finished streams per day for the whole dataset, shows that the pure beststreamers are gaining ground, while the pure print bestsellers and the titles popular both in print and in streaming services are decreasing as per finished streams (see Fig. 1).

The result indicates that subscription-based streaming services are starting to find their stride as a portal for book consumption, and that this shift—slowly but steadily—is drifting away from print bestsellers. In relative numbers, successful beststreaming-only titles are becoming more important on the Storytel platform, while bestsellers in print are becoming less important. The observed textual differences in prose style between popular audiobooks and popular print books found by Berglund and Dahllöf [27] point in the same direction; consumers of audiobooks in streaming services seems to favor a different kind of writing. What these changes will mean for book publishing in the future is yet to be seen. One scenario is that bestsellers and beststreamers will continue to diverge. This could lead to a book trade consisting of two increasingly separated segments, where books are possibly published in different versions to suit the respective format. The other scenario is that the print world will start to adapt to the rules that apply in the world of beststreamers. Such an adaptation can take many forms—editing and publishing with audio in mind, experiments with audio only-publishing, well-established print authors turning to born-audio formats, etc.—some of which are already happening.

Nuances in Digital Book Consumption Through Average Finishing Degrees

Consumption patterns have this far been discussed only in terms of finished streams, which equates with books that have been completed by the reader, either listened or read (or a combination of these two things) all the way through. Average finishing degrees (AFD) measure levels of completion and thereby of reader devotion as well as the ability of narratives to absorb readers. What immediately stands out when AFD numbers are investigated are the correlations between popularity on the platform (in terms of finished streams) and high completion rates. This goes for practically all parameters: audiobooks has higher AFD scores than ebooks (74% compared to 69%); crime fiction has the highest AFD score among the genres, while prestigious fiction has the lowest (76% for crime fiction, 65% for other popular fiction, and 53% for prestigious fiction); Swedish originals have higher AFD scores than translated titles (74% compared to 64%); and pure beststreamers and titles popular both in streaming services and in print have higher AFD scores than print-only bestsellers (79% and 75% respectively compared to 64%) (see Figs. 2, 3, 4).

This means, in general, that titles consumed by many users on the Storytel platform (in terms of finished streams) also are titles that consumers tend to finish. This result makes sense and can also be tracked down by statistical means. Figure 5 shows a scatterplot of all the titles in the dataset, distributed along the x-axis by AFD and along the y-axis by number of finished streams. The positive curve of the gray interpolation line indicates the positive correlation between the two variables in statistical terms. The R-value 0.475 from the regression analysis suggests a moderate linear relationship, which can be interpreted as something like: generally, a high AFD follows a high number of finished streams, but there are also several exceptions to this rule.

If we take a close look at Fig. 5, this seems plausible. In fact, a lot of more nuanced information can be drawn from this scatterplot. First, almost all books with really high AFD scores (> 80%) are works of crime fiction. Indeed, crime fiction seems to be the genre in particular that manages to keep up reader interest and produce page-turning effects. This is not surprising per se as crime fiction has for long had a strong position in the bestselling segment in Sweden (see [25], 92–98), but it would be interesting to compare this genre to others at scale to see if this ability to attract devoted readers can be explained on a textual and narrative level. It is important to note, though, that it is not the most popular novels in terms of finished streams that are completed to the highest extent, but rather the segment just under the very top. For titles with AFD scores over 80%, we find not David Lagercrantz, Lars Kepler or Camilla Läckberg, but lesser-known names as Sofie Sarenbrandt, Carin Gerhardsen and Dag Öhrlund. A probable explanation for this outcome is that the latter category of authors are highly profiled within the crime genre, but not so much outside of it. Thus, they mostly attract already engaged crime-fiction readers, whereas writers like Lagercrantz, Kepler and Läckberg attract a broader audience. But this wider audience is also less faithful as consumers, which leads to lower AFD scores.

The exceptions to the rule that high AFD equals crime fiction are interesting to study a bit further. These include one historical novel by Jan Guillou, a very well-known and popular author in Sweden (Blå stjärnan [Blue Star]), the romantic novel Still Me by the British writer Jojo Moyes, and two titles in Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Novels series, Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay and The Story of the Lost Child.Footnote 5 What unites these titles is not genre, nor country of origin, but that they all belong to a series, and that none of them are the first title in their series. Interestingly, a closer inspection of the Naples Novels (all four of which were bestsellers in Sweden in the period and thus are all included in the dataset) tells a clear story: the first novel in the series is the one streamed the most, but it is also the one with a significantly lower AFD than the others (see Table 5).

Thus, while there exists a positive correlation in general between number of finished streams and high AFD, this relationship on the level of individual series is likely to be inverted in most cases (as in the Ferrante case), simply due to the fact that those who cling to series to the end are the most devoted readers. If you have read the first three Ferrante novels and start to stream the fourth and last one, you are likely much more motivated to read it through than if you have just embarked on the first book in the series; this reader psychology is what the Ferrante example above tells us. The relationship between popularity and reader devotion should therefore be regarded simultaneously at two parallel levels: one on the generic level (where number of finished streams and high AFDs have a positive correlation), and one on the level of the individual book series (where number of finished streams and high AFDs is likely to have a negative correlation).

Conclusion: Conceptualising the Beststreamer

This paper departs from book consumption data from a major subscription-based streaming service for books, Storytel, to track how bestsellers have been consumed in print and digital in Sweden over the last five years. In doing this, two new methodological concepts for digital publishing studies are introduced: the beststreamer, which equals the most highly consumed titles in an online streaming service for books in a particular region and time; and the average finishing degree, which is the number of finished streams of a particular title divided by its number of started streams. The data along with these concepts allow for a tracking of book-consumption behavior simultaneously at scale and in a far more nuanced way than what is possible by means of traditional measures of book consumption, such as sales and library lending.

Empirically, large differences between the bestselling and the beststreaming segments were found. Print bestsellers show a genre-wise much greater heterogeneity than digital beststreamers. Where the former spans prestige fiction to crime fiction, the latter consist almost entirely of crime fiction, primarily written by domestic authors. This pattern emerges on the title level but grows stronger when actual consumption is analyzed. Similarly, crime fiction is the by far most successful genre in terms of average finishing degree, where prestige fiction, on the other hand, is the kind of literature in this segment where most readers tend to drop out along the narrative line.

The results indicate that readers prefer different kinds of literature when they listen to or read in online streaming platforms and when they buy print books—at least for the moment, and at least in Sweden. There are obviously a multitude of reasons for these differences—including platform design, pricing models, supply, marketing, customer base, and media-specific features of the audiobook, the dominating format for book consumption in digital streaming services for books—but the differences in themselves make the beststreamer a relevant and important concept for understanding the increasingly digital contemporary book trade. And this goes for both the empirical and the conceptual levels: it is important to highlight differences between book distribution channels, but it is even more interesting to discuss why these differences emerge.

The growing subscription-based models for selling not digital books, but access to large collections of digital books, affects consumption behavior, but perhaps not in the ways one would immediately assume. For instance, one could imagine that most readers would try out lots of books when they have access to “it all,” so to speak, before settling on the one to listen to. Similarly, one could assume that people who buy books also tend to read them through. While there is no data available for consumption patterns in print books, the consumption data in this investigation complicates such preconceptions. The average finishing degrees for most popular titles in this comparison are actually rather high, with a mean value of 71% and with several titles holding AFD scores over 80%, some bordering 90. This means that over seven out of ten consumers who have started to listen to one of the bestsellers or beststreamers also completed the book in its entirety. The AFD scores for print bestsellers only are lower, and especially low concerning prestige titles. Although book consumption in print and in digital streaming services are not the same thing, the latter at least indicates that consumption of prestige fiction in the sense of buying books is not the same as reading them; there is an inherent value in buying, owing, and giving away print books of prestige fiction that simply disappears in streaming services, where actual consumption is measured. This discrepancy in consumption behavior between buying books and consuming them will become increasingly important as the streaming services deploy a business model called revenue share, meaning that publishers get paid for the number of minutes streamed on the platforms for their collections of books. This is very different from getting paid by the number of sold entities (no matter the grade of actual consumption), and it will undoubtedly make books that people tend to finish more valuable for publishers henceforth.

The ability to track and understand how reader devotion works and operates on the level of book trade segments, genres, authorships, and individual titles will be a crucial task for both publishers and publishing-studies scholars in the future. As I have tried to demonstrate in this paper, book consumption data calculated per average finishing degree scores is one way of accomplishing an operative, transparent and understandable measurement of such reader devotion. Hopefully, this approach can attract recognition within publishing studies and contemporary book history. The lesson learned from this study is that bestsellers diverge from beststreamers on the empirical level, but also so on the material and conceptual levels. As these aspects go hand in hand and affect each other, much is gained by analyzing them together.

Notes

The official format figure from Storytel, covering all consumption in Sweden in 2020, is 92% audiobooks (Mikael Holmquist, Storytel, e-mail interview with author, February 10, 2021).

This agreement states that the research group are free to analyse the data provided in any way they find interesting, as long as the data itself is not shared with a third party, and all research output from the project is sent to Storytel.

See e.g. Laura J. Miller (2000), “The Best-Seller List as Marketing Tool and Historical Fiction,” Book History 3.

Linear regression, a standard procedure in applied statistics, is a prediction of the best-fitting interpolation line for all data points (xn, yn) according to the formula y = mx + b, where m is the slope of the line, and b is the value of the line where it crosses the y-axis (e.g., the starting point in this analysis, 1 January 2015). A positive m-value indicates a positive, rising trend (in this case an increased proportion of the streams in the top segment of the book trade), whereas a negative m-value indicates the opposite. In this analysis, the regression lines have been calculated with the Python standard math library NumPy.

The latter is here categorized as prestige fiction as it was shortlisted for the 2016 Man Booker International Prize.

References

Statista. US Book Market—Format Market Shares 2011–2019. Statista. https://www.statista.com/topics/1474/e-books/ (2019). Accessed 25 Feb 2021.

Wischenbart R, Fleischhacker MA. The Digital Consumer Book Barometer 2019: a report on e-book and audiobook sales in Canada, Germany, Italy, The Netherlands & Spain and Digital Imports. Vienna: RWCC; 2019.

Wischenbart R. The Digital Consumer Book Barometer: Covid-19. Special. Frankfurt: Bookwire; 2020.

Wikberg E. Bokförsäljningsstatistiken. Helåret 2020. Stockholm: Swedish Booksellers’ Association and Swedish Publishers’ Association; 2021.

Murray S. The digital literary sphere: reading, writing, and selling books in the Internet Era. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2018.

Berglund K, Steiner A. Is backlist the new frontlist? Large-scale data analysis of bestseller book consumption in streaming services. LOGOS J World Publ Community. 2021;32(1):7–24.

Murray S. Secret agents: algorithmic culture, goodreads and datafication of the contemporary book world. Eur J Cult Stud. 2019;22:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549419886026.

Hanner H, Connor A, Wikberg E. Ljudboken. Hur den digitala logiken påverkar marknaden, konsumtionen och framtiden. Stockholm: Swedish Publishers’ Association; 2019.

Davies T, Frank M. ‘There’s no such thing as raw data’: exploring the socio-technical life of a government dataset. In: WebSci '13: Proceedings of the 5th Annual ACM Web Science Conference, p. 75–8. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1145/2464464.2464472.

Striphas T. The late age of print: everyday book culture from consumerism to control. New York: Columbia University Press; 2009.

Ray-Murray P, Squires C. The Digital Publishing Communication Circuit. Book 2.0. 2013;3(1):3–23.

Kirschenbaum M, Werner S. Digital scholarship and digital studies: the state of the discipline. Book Hist. 2014;17:406–58. https://doi.org/10.1353/bh.2014.0005.

Noorda R, Marsden S. Twenty-first century book studies: the state of the discipline. Book Hist. 2019;22:370–97.

Finn E. New literary cultures: mapping the digital networks of Toni Morrison. In: Lang A, editor. From codex to hypertext: reading at the turn of the twenty-first century. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press; 2012. p. 177–202.

Gruzd A, Rehberg-Sedo D. #1b1t: investigating reading practices at the turn of the twenty-first century. Mémoires du livre/Stud Book Cult. 2012. https://doi.org/10.7202/1009347ar.

Riddell A, van Dalen-Oskam K. Readers and their roles: evidence from readers of contemporary fiction in the Netherlands. PLoS ONE. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201157.

Berglund K, Dahllöf M, Määttä J. Apples and oranges? Large-scale thematic comparisons of contemporary Swedish popular and literary fiction. Samlaren. 2019;140:228–60.

Koolen CW, et al. Literary quality in the eye of the Dutch Reader: the National Reader Survey. Poetics. 2020;79:101439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2020.101439.

Rowberry S. The limits of big data for analyzing reading. Participations. 2019;16(1):237–57.

Allington D, Brouillette S, Golumbia D. Neoliberal tools (and archives): a political history of digital humanities. LA Review of Books, 1 May. https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/neoliberal-tools-archives-political-history-digital-humanities/. 2016.

Da NZ. The computational case against computational literary studies. Crit Inq. 2019;45(3):601–39. https://doi.org/10.1086/702594.

Marche S. Literature is not data: against digital humanities. LA Review of Books, 28 October. https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/literature-is-not-data-against-digital-humanities/. 2012.

English JF, Underwood T. Shifting scales: between literature and social science. Mod Lang Q. 2016;77(3):277–95.

Underwood T. A genealogy of distant reading. Digit Humanities Q. 2017;11(2):2.

Berglund K. Deckarboomen under lupp: Statistiska perspektiv på svensk kriminallitteratur 1977–2010. Uppsala: Uppsala University; 2012.

Lenas S, Cederskog G. Konflikt om ljudböcker på Bonniers: ‘Nobelpristagare underpresterar digitalt’. Dagens Nyheter, March 22. 2018.

Berglund K, Dahllöf M. Audiobook stylistics: book format comparisons between print and audio in the bestselling segment. Forthcoming 2021.

Have I, Pedersen BS. Digital audiobooks: new media, users and experiences. New York: Routledge; 2016.

Ohlsson J, editor. Mediebarometern 2019. Gothenburg: Nordicom; 2019.

Striphas T. Algorithmic culture. Eur J Cult Stud. 2015;18(4–5):395–412.

Steiner A. The global book: micropublishing, conglomerate production, and digital market structures. Publ Res Q. 2018;34:118–32.

Miller LJ. The best-seller list as marketing tool and historical fiction. Book Hist. 2000;3:286–304.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted within the research project “Patterns of Popularity: Towards a Holistic Understanding of Contemporary Bestselling Fiction,” supported by the Swedish Research Council (Ref: 2019-02829).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Uppsala University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Berglund, K. Introducing the Beststreamer: Mapping Nuances in Digital Book Consumption at Scale. Pub Res Q 37, 135–151 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12109-021-09801-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12109-021-09801-0