Abstract

Modeling a flexible multibody system employing the floating frame of reference formulation (FFRF) requires significant computational resources when the flexible components are represented through finite elements. Reducing the complexity of the governing equations of motion through component-level reduced-order models (ROM) can be an effective strategy. Usually, the assumed field of deformation is created considering local modes, such as normal, static, or attachment modes, obtained from a single component. A different approach has been proposed in Cammarata (J. Sound Vibr. 489, 115668, 2020) for planar systems only and involves a reduction based on global flexible modes of the whole mechanism. Through the use of global modes, i.e., obtained from an eigenvalue analysis performed on the linearized dynamic system around a certain configuration, it is possible to obtain a modal basis for the flexible coordinates of the multibody system. Here, the same method is extended to spatial mechanisms to verify its applicability and reliability. It is demonstrated that global modes can be used to create ROM both at the system and component levels. Studies on the complexity of the method reveal this approach can significantly reduce the calculation times and the computational effort compared to the unreduced model. Unlike the planar case, the numerical experiments reveal that the system-level approach based on global modes can suffer from slow convergence speed and low accuracy in results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The finite element floating frame of reference formulation (FE-FFRF) often accompanies considerable use of computational resources to model flexible multibody systems [41]. The interaction between the gross motion of the floating frames and the small deformations of the finite elements generates a strong coupling between the two motion fields which leads to high complexity. In particular, inertia-related terms are highly nonlinear and demand the highest computational burden. It is well known that the use of different floating frames considering different reference conditions (RCs), employed to delete the rigid motions of the flexible elements, can simplify the inertia terms [2]. In this regard, the free-floating RCs have received the greatest diffusion in flexible multibody software. Nevertheless, recent investigations have demonstrated that the free-floating RCs can lead to inaccurate results [10, 36, 38, 42, 43]. To face this issue, some researchers simplify inertial terms using accurate definitions of the inertia shape integrals, that is, integrals connected to the geometry and the shape matrix of the finite elements [30, 33, 37, 47]. Recently, Zwölfer and Gerstmayr employed a nodal-based corotational formulation of the FFRF to bypass these integrals [48–51].

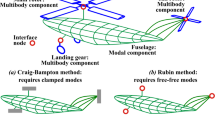

The computational load rises quickly by increasing the number of flexible bodies, or by using refined mesh to describe the finite elements, therefore the greatest efforts of the scientific community have been directed to create reduced-order models (ROMs), i.e., models in which the number of flexible coordinates is contained [15, 16, 35]. Most of the ROMs implemented in the FFR are component-level based and the reduction is applied to the elastic coordinates of each flexible body [1, 4, 8, 26, 29, 31, 45, 46]. In [24, 25] a component-level reduction method based on an enhanced Craig–Bampton method is described. The other way around, the system-level based formulations employ a global reduction of rigid and elastic components [7, 22, 32, 34]. Recently, the component mode synthesis (CMS) techniques have been employed to condense all the elastic coordinates, thereby obtaining an equivalent rigid-body model [19].

Here, the method presented in [9] is extended to spatial systems. Two reduction methods based on the global modes of the mechanism are proposed. In both approaches, only the elastic coordinates of the components are replaced using global flexible normal modes while the final ROM maintains the gross motion coordinates. In the system-level approach, all flexible bodies deform together following a linear combination of global flexible modes, and the elastic coordinates are replaced by modal intensities associated with these modes. Differently, the component-level approach employs the global modes to create basis function for each component in a similar way as done for a classic CMS reduction method.

In Sect. 2 a brief mathematical background on the spatial FE-FFRF is provided. Section 3 introduces the linearization process necessary to obtain global modes. Three types of global modes are described, but only the flexible global modes are used to derive the final ROM. In Sect. 4, the complexity of the method is analyzed. Section 5 focuses on three numerical applications. Finally, conclusions are drawn to summarize the strengths and weaknesses of the method.

2 Background on the spatial FE-FFRF

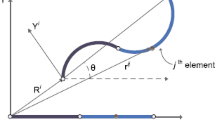

The spatial kinematics of a point belonging to a flexible body depends on the gross motion of the floating frame of reference and on the local small deformations described in the floating frame. As depicted in Fig. 1, the positioning vector \(\mathbf{r}^{ij}\) of point \(P^{ij}\), belonging to the finite element \(j\) of body \(i\), is written as

where \(\mathbf{R}^{i}\) is the positioning vector of the floating frame, \(\mathbf{A}^{i}\) is the rotation matrix of the floating frame (\(x^{i}\),\(y^{i}\),\(z^{i}\)) concerning the reference frame (\(X\),\(Y\),\(Z\)), parameterized through a set of orientation parameters in \(\boldsymbol {\theta }^{i}\), \(\mathbf{u}_{0}^{i}\) denotes the local undeformed position of \(P^{ij}\), and finally, \(\mathbf{u}_{f}^{i}\) is the displacement due to the deformation. The two vectors inside the parentheses characterize the position vector \(\mathbf{u}^{i}\) of the point inside the floating frame and can be expressed in terms of a set of nodal deformations \(\overline{\mathbf{q}}^{i}\) through the use of a shape matrix \(\mathbf{S}^{i}\), i.e.,

where, in turn, \(\overline{\mathbf{q}}^{i}\) has been decomposed in the two parts \(\overline{\mathbf{q}}_{0}^{i}\) and \(\overline{\mathbf{q}}_{f}^{i}\), respectively, denoting the elastic coordinates in the undeformed configuration \(\mathcal{C}_{0}^{ij}\) and deformed configuration \(\mathcal{C}^{ij}\).

2.1 Reference conditions

The vector of nodal deformations \(\mathbf{q}_{f}^{i}\) could generate rigid motions in the element that would be superimposed and therefore indistinguishable from those produced by the gross motion of the floating frame. It is necessary to introduce a set of constraints to eliminate these unwanted rigid motions from the nodal deformations of the body and generate only deformations. These constraints define the so-called reference conditions and are contained in a linear transformation matrix \(\mathbf{B}_{2}^{i}\) mapping a new independent set \(\mathbf{q}_{f}^{i}\) of nodal deformations into the original set \(\overline{\mathbf{q}}_{f}^{i}\), i.e.,

As already remarked in many textbooks and papers [39, 40, 43], the reference conditions “define the nature of the deformable body reference.” The reference conditions are not unique but should be selected considering two fundamental aspects: their number “must be greater than or equal to the number of rigid body modes in the assumed displacement field” [39]; their type should be consistent with the multibody joints of the system. The first aspect imposes a lower bound on the number of reference conditions restricting the feasible cases only to isostatic or hyperstatic systems. The significance of the second aspect is more related to a rule of thumb in choosing the appropriate set of reference conditions that match with the multibody joints of the mechanism. It has been demonstrated that some reference conditions are not suitable for any application [1, 2]. A good hint is to select the reference conditions that resemble the mechanical joints to which the single body is linked. By introducing the RCs of Eq. (3) into Eq. (1), the positioning of a point in its deformed configuration is governed by the gross motion of the body reference expressed by \(\mathbf{R}^{i}\) and \(\mathbf{A}^{i}(\boldsymbol {\theta }^{i})\) and the small deformation \(\mathbf{q}_{f}^{i}\) expressed in the floating frame.

2.2 Inertia shape integrals

The terms of the generalized mass and stiffness matrices and those of the generalized velocity vector of centrifugal and Coriolis forces, that will be reported in the next subsection, depend on some quantities referred to as the inertia shape integrals. The latter are volume integrals depending on the undeformed geometry, on the inertial and structural parameters, as well as on the mesh, the shape matrix \(\mathbf{S}\) and the RCs, as shown in Fig. 2.

The inertia shape integrals are time-invariant and are generally computed in the preprocessing phase. In the following, the notation introduced in [37] to describe inertia shape integrals will be briefly recalled. Interested readers are referred to equivalent formulations in [30, 47].

Denoting with \(\mathbf{u}_{0,i}\) the \(i\)th component of \(\mathbf{u}_{0}\) and with \(\mathbf{S}_{j}\) the \(j\)th row of the shape matrix \(\mathbf{S}\), the nine inertia shape integrals have the expressions reported in Table 1.

It can be observed that \(\mathbf{I}^{3},\mathbf{I}^{4},\mathbf{I}^{5},\mathbf{I}^{6},\mathbf{I}^{8}\), and \(\mathbf{I}^{9}\) depend on the entries of shape matrix \(\mathbf{S}\) and the RCs matrix \(\mathbf{B}_{2}\). These inertia shape integrals will be updated after creating the transformation matrix based on the global modes, as will be explained in the following section.

2.3 Governing equations of motion

The set \(\mathbf{x}^{i}\) of rigid and flexible coordinates becomes

These coordinates are not independent because of the mechanical joints coupling the parts of the mechanical system or because of the motions imposed on some components. The kinematic constraints introduced by the mechanical joints form a set of nonlinear equations coupling the system coordinates, i.e.,

where the constraint vector \(\mathbf{C}\) takes into account all the kinematic constraints coupling the system coordinate vector \(\mathbf{x}\) [27]. Introducing the generalized forces due to the constraints to the dynamic equations of each body leads to

where \(\mathbf{M}^{i}\) and \(\mathbf{K}^{i}\), respectively, are the generalized mass and stiffness matrices, \(\mathbf{C}_{\mathbf{q}^{i}}\) is the constraint Jacobian matrix referred to the body \(i\), \(\boldsymbol {\lambda }^{i}\) is the corresponding vector of Lagrangian multipliers, \(\mathbf{Q}_{e}^{i}\) is the vector of external forces, and \(\mathbf{Q}_{v}^{i}\) is the velocity vector that contains the gyroscopic and Coriolis forces. The governing equations of motion can be partitioned as in [39], i.e.,

where all terms are referred to the reference and elastic coordinates and the generalized external, Coriolis, and centrifugal forces have been gathered into a single vector of generalized forces \(\mathbf{Q}^{i}\). The block matrices of \(\mathbf{M}^{i}\) depend on the inertia shape integrals and the coordinates \(\mathbf{x}^{i}\); the components of the velocity vector \(\mathbf{Q}_{v}^{i}\) depend on the inertia shape integrals, the coordinates \(\mathbf{x}^{i}\), and their time-derivative \(\dot{\mathbf{x}}^{i}\). The expressions for \(\mathbf{M}^{i}\) and \(\mathbf{Q}_{v}^{i}\) will be reported in Sect. 4.

3 Global modes

The number of EoMs can be largely limited by using ROMs. Among the latter, those based on CMS are the most popular. The component modes are particular shapes used to create a basis necessary to reduce the number of elastic coordinates while capturing the dynamic properties of the original model. The component modes used in the literature are of various types: static, dynamic, constrained, free, mixed, and so on. Usually, the component-level reduction is employed, meaning that each flexible component is reduced individually using a given set of component modes. The resulting reduced components are then assembled to create the final reduced system. A further reduction can follow the first local reductions to condense the so-called interface modes [17, 21, 28] or to create an equivalent rigid body model [19]. Here, a different approach based on global modes is employed. A global mode pertains to the whole assembled system and it is obtained after the linearization of the EoMs around a given configuration.

3.1 Linearization

In the following, only the linearization around a rigid-reference configuration will be discussed. A rigid-reference configuration is obtained when all the elastic coordinates \(\mathbf{q}_{f}\), as well as all velocities \(\dot{\mathbf{x}}\) and the external forces applied to the system, are zero. The rigid-reference configuration is a zero-strain energy configuration and belongs to the space of rigid configurations that can be attained by a given mechanism. Denoting with \(\mathbf{x}_{l}\) the vector of coordinates at the generic rigid-reference configuration, it is derived that the chosen linearization configuration must satisfy three conditions, i.e.,

where \(\boldsymbol {\lambda }_{l}\) is the Lagrangian multiplier vector at the linearization configuration. The linearization of the constraints and EoM, i.e., Eqs. (5) and (6), around a rigid-reference configuration leads to

where \(\mathbf{M}\) is the mass matrix, \(\mathbf{S}\) is the tangent stiffness matrix, \(\mathbf{C}_{x}\) is the Jacobian matrix of the constraint vector \(\mathbf{C}\), \(\mathbf{r}_{l}\) is the residual vector, and \(\Delta {\mathbf{x}}\), \(\Delta \ddot{\mathbf{x}}\), \(\Delta \boldsymbol {\lambda }\) are the increments of the variables around the linearization configuration. In the following sections, the matrix containing \(\mathbf{S}\) in Eq. (9) will be referred to as the generalized tangent stiffness matrix. The latter or its scaled version [6] is employed in the NR-algorithm to solve the nonlinear system deriving from the application of an implicit integration scheme. Due to the choice of the linearization configuration, the tangent stiffness matrix has the following simplified expression:

The reader should notice that the tangent damping matrix is not present in the system (9). This term depends linearly on the velocities and is zero due to the particular choice of the linearization point. Since \(\mathbf{x}_{l}\) must satisfy the constraint equations, it follows that \(\mathbf{C}_{l} \equiv {\mathbf{C}}(\mathbf{x}_{l})=\mathbf{0}\). Even the residual vector

evaluated at the same configuration point leads to \(\mathbf{r}_{l} = \mathbf{0}\). As reported in [11], the linearized modal equations of motion of the constrained flexible multibody system can be derived from the homogeneous form of Eq. (9), i.e.,

where all the matrices must be calculated at the configuration \(\mathbf{x}_{l}\).

3.2 Eigenproblem and global modes determination

The dimension of the eigensystem (12) is \(n+m\), where \(n\) is the dimension of \(\mathbf{q}\) and \(m\) is the dimension of the constraint vector \(\mathbf{C}\). The eigensystem (12) yields three type of eigenvectors of dimension \(n+m\) [11]:

-

f global rigid-reference modes \(\boldsymbol {\phi }^{R}\) with associated zero eigenfrequencies,

-

(\(n-m-f\)) global flexible modes \(\boldsymbol {\phi }^{F}\) with finite eigenfrequencies \(\omega _{f}\),

-

\(2m\) global constraint modes \(\boldsymbol {\phi }^{C}\) associated with couples of frequencies \(\pm \infty \).

It can be verified that the final number of modes is \(n+m\) as the dimension of the eigensystem (12). To explain the nature of the global modes, let us refer to the spatial slider–crank mechanism displayed in Fig. 3 where the crank and slider are rigid bodies and the connecting rod, or coupler, is flexible. The rigid-reference configuration has been obtained by solving the inverse kinematic problem by imposing that the \(x\)-coordinate of the slider be at −0.27 (m). Then, the eigensystem (12) has been solved, and Fig. 4 reports the first four global modes of the mechanism, sorted from the lowest to the highest frequency value. The first global mode is the only global rigid-reference mode of the mechanism: in fact, the spatial slider–crank is a 1-dof mechanism, therefore \(f=1\). It can be observed that the flexible coupler remains undeformed and the mechanism accomplishes a rigid motion. The remaining global modes plotted in the figure are the first three global flexible modes. The connecting rod experiences bending deformations and the corresponding eigenfrequencies grow passing from the first to the third flexible mode. The last type of global modes, i.e., the global constraint modes \(\boldsymbol {\phi }^{C}\) cannot be displayed because \(\boldsymbol {\phi }^{C}=[{\mathbf{0}}^{T},\boldsymbol {\phi }_{\lambda }^{T}]^{T}\) in the eigensystem (12), meaning that both the displacements pertaining the gross motions and the elastic coordinates are zero.

The first four global modes of the spatial slider–crank. From top-left: the rigid global mode \(\boldsymbol {\phi }^{R_{1}}_{\mathbf{x}}\), the first flexible global mode \(\boldsymbol {\phi }^{F_{1}}_{\mathbf{x}}\), the second flexible global mode \(\boldsymbol {\phi }^{F_{2}}_{\mathbf{x}}\), and the third flexible global mode \(\boldsymbol {\phi }^{F_{3}}_{\mathbf{x}}\)

3.3 Flexible global modes and transformation matrix

The global modes obtained solving the eigensystem (12) are summarized in Fig. 5. The figure shows that \(n+m\) global modes with dimension \((n+m)\times 1\) are obtained. Denoting with \(\boldsymbol {\phi }_{\mathbf{x}}=[\boldsymbol {\phi }_{r}^{T},\boldsymbol {\phi }_{f}^{T}]^{T}\) the \(n\)-dimensional part including both the rigid and elastic coordinates of the generic mode \(\boldsymbol {\phi }\), let \(\boldsymbol {\phi }^{F}_{\mathbf{x}}\) be the corresponding part referred to all the flexible global modes. Each mode of \(\boldsymbol {\phi }^{F}_{\mathbf{x}}\) represents a global deformed shape as those reported in Fig. 4.

Since the proposed reduction method involves only the elastic coordinates of the flexible parts, only the block \(\boldsymbol {\phi }^{F}_{f}\) of \(\boldsymbol {\phi }^{F}_{\mathbf{x}}\) is used to create the transformation matrix \(\boldsymbol {\varPsi }\). Furthermore, only a reduced set of \(k< n-m-f\) global flexible modes is retained to create \(\boldsymbol {\varPsi }\). The selection of the global flexible modes follows the same rules used in other reduction methods [18, 20, 23, 44, 51] and can be entrusted to effective masses, experimental results, bandwidth, and so on. It is important to emphasize that the \(f\)-dimensional modes of \(\boldsymbol {\phi }^{F}_{f}\) refer to the elastic coordinates of the flexible parts composing the mechanical system and are already expressed in the floating frames and do not require further transformation. Selecting the corresponding blocks of \(\boldsymbol {\phi }^{F}_{f}\) referred to the single flexible bodies it is possible to create a basis of global modes for each component, completely analogous to what has been done in the classic normal mode approach. In this case, the modes describe shapes obtained from a global analysis and not a local eigenproblem. This strategy will be referred to as a component-level reduction based on global modes, hereafter denoted with the GMc method.

Instead of working on single flexible parts, suppose the whole mechanism is deformed following a superposition of global shapes, i.e., the columns of \(\boldsymbol {\varPsi }\), namely

where \(p_{j}\) are real numbers referring to each global flexible mode. The vector \(\mathbf{p}_{f}\) containing all \(p_{j}\) is referred to as the global intensity vector. Equation (13) becomes

expressing the transformation that will be used to derive the ROM. As already mentioned, the columns of \(\boldsymbol {\varPsi }\) are global shapes involving all flexible parts together. Therefore, too few global flexible modes would limit the deformation of the mechanism. This means that the mechanism would deform only following a limited set of shapes. This shortcoming, which will be shown in the numerical part, can be relaxed by controlling the accuracy of the ROM compared to the full unreduced model results. Hereafter, this approach will be referred to as the GMs method.

3.4 Reduced order model (ROM)

The ROM of the GMc approach follows the same rules reported in [41] and it is not reported for brevity. The ROM of the GMs approach is readily obtained by means of Eq. (14). Recalling that \(\overline{\mathbf{q}}_{f} = \mathbf{B}_{2} {\mathbf{q}}_{f}\), an easy way to obtain the ROM is to substitute \(\mathbf{B}_{2}\) with a new RCs matrix, defined as

This matrix is then used to update the inertia shape integrals, as shown in the Fig. 2 and Table 1. It is noteworthy that this substitution is carried out in the preprocessing phase and leads to the final ROM

where the reduced matrices and vectors have been overlined. The expressions of the reduced matrices are not reported because these are equal to the classic matrices reported in [41], obtained by replacing the updated matrix \(\mathbf{B}_{2}^{*}\). Using the global flexible modes in the GMs approach has the advantage of maintaining a low number of coordinates when the number of flexible bodies increases while achieving good performance in terms of solution accuracy. This results sometimes in a reduced computational burden. Nevertheless, this is not a rule, as observed in the numerical applications, since the global assumed modes can stiffen the mechanism too much, therefore, creating a stiff system with slower convergence.

4 Complexity and flops

In this section, the computational complexity of some important parts of the algorithm used for the dynamic analysis is derived in terms of the number of operations or flops. The flowchart of Fig. 6 describes all the blocks necessary to implement the dynamic algorithm both for the full and reduced models. The preprocessing part allows for computing the inertia shape integrals, the RCs, and, in the case of the application of ROM, the transformation matrix. The preprocessing part is excluded from the complexity evaluation because it is processed only once before the start of the dynamic simulation. The algorithm proceeds by inserting the initial state \((\mathbf{x}_{0},\dot{\mathbf{x}}_{0})\) evaluated at the initial time \(t_{0}\). The generalized \(\alpha \)-method receives the current state and returns the newly updated state at the time \(t+h\), with \(h\) being the time-step of the simulation. Inside the generalized \(\alpha \)-method, the generalized mass matrix, the generalized vector of forces, the constraint vector, and its Jacobian matrix are evaluated. Then, the increments of the unknowns \((\Delta {\mathbf{x}}, \Delta \boldsymbol {\lambda })\) are obtained utilizing the Newton–Raphson algorithm. This block calls the LU-decomposition algorithm for sparse matrices to be executed. The algorithm stops when the residual vector is lower than a given tolerance parameter \(TOL\). The most demanding blocks, in terms of computations, have been highlighted in Fig. 6 and pertain to the generalized mass and forces calculation (block \(B_{1}\)) and the computation of the increments of coordinates and Lagrangian multipliers (block \(B_{2}\)).

Focusing on block \(B_{1}\), the steps necessary to derive the generalized mass matrix \(\mathbf{M}_{TOT}\) and the generalized vector of forces \(\mathbf{Q}_{TOT}\) are reported in Table 2. The shape integrals recalled in the table have been introduced in Sect. 2.2. The reader is referred to [37] for further details. In the same table, the complexity of the most relevant operations has been reported. Here, the parameter \(f_{i}\) is the number of elastic coordinates \(\mathbf{q}_{f}^{i}\) of each flexible body for FM while it is equal to the number of retained modes \(k\) for GMs regardless of the number of flexible bodies \(n_{b}\) included in the system. Regarding the computation of the increments (block \(B_{2}\)), FM yields a generalized tangent stiffness matrix that can be reordered in a block-diagonal sparse matrix while GMs produces an arrowhead banded sparse matrix due to the coupling provided by the global intensities. The size of the arrow, in terms of rows and columns, is precisely equal to the number \(k\) of global intensities. Nevertheless, evaluating the complexity for \(B_{2}\) is not a trivial issue therefore further insights will be investigated in the following section using a numerical test. The same table can be used to estimate the complexity of GMc, or any other CMS method, by considering that \(f_{i}\) is equal to the number \(k_{i}\) of component-modes chosen to represent the elastic field of the ith flexible body.

5 Numerical applications

In this section, three numerical applications are proposed. First, the spatial slider–crank mechanism is used to verify the applicability of the method. The proposed approach is compared to two classic CMS reduction methods: the normal mode approach and the Craig–Bampton reduction method. The second application is an open-chain mechanism composed of N-links. This application will be used to calculate the complexity of the method compared to the other reduction methods. The third application is a spatial Sarrus 6-bar mechanism. This example is used to understand when the method can be used and to describe its strengths and weaknesses.

5.1 The spatial slider–crank mechanism

In this subsection, the spatial slider–crank, presented in Sect. 3.2 is chosen as a case study to discuss the applicability of the proposed approach based on global modes and for the comparison with two classic CMS reduction methods: the normal mode approach [41], denoted with NM, and the Craig–Bampton method [13], referred to as CB. Here, the two approaches, i.e., the component-reduction approach GMc and the system-reduction approach GMs are coincident since one single flexible body has been considered. Indistinctly, we will refer to a unique GM approach. Going deeper into the description of Fig. 3, the spatial slider–crank is composed of a rigid crank, a flexible connecting rod, and a rigid slider. The crank is connected to a fixed frame through a revolute joint and to the connecting rod through a spherical joint. Then, the connecting rod is linked to the slider through a universal joint. Finally, the slider is constrained to move along the X-axis using a prismatic joint. All parameters employed in the numerical simulations are reported in Table 3. The three reduced models, i.e., GM, NM, and CB, have been compared to the full model, hereafter referred to as FM. The governing equations of motion have been integrated using the generalized-\(\alpha \) scheme proposed in [3] considering a constant time-step \(h=1\)E−4 (s), a tolerance (TOL) of 1E−8 and \(\alpha =0.7\).

The following motion has been imposed to the \(x\)-coordinate (m) of the slider:

where \(t\) denotes time. The RMS error \(\epsilon _{RMS}\), defined as

has been used to compare FM and the reduced models. In the previous Eq. (17), \(N\) is the number of instants of time while (\(x,y,z\)) and (\(\bar{x}, \bar{y},\bar{z}\)) are the coordinates of a same node for the full and reduced model, respectively. For our purposes, the mid-span node \(G_{2}\) has been selected for the comparison.

The global modes used in the GM are of the same type as those reported in Fig. 4. The local modes used for the NM and CB are obtained by imposing spherical-universal (S-U) boundary conditions to the boundary nodes of the connecting rod. Figure 8 shows these modes respectively for the NM in the left subplot (a) and CB in the right subplot (b). The NM considers shapes obtained by solving an eigenvalue problem. Each normal mode is labeled using its frequency \(f_{i}\). Since only one flexible body is considered in the model, the local modes of NM are the same as the global flexible modes of GM and the two methods yield the same results. The modes used for CB are distinguished into fixed interface normal modes, labeled with \(f_{i}\), and static constraint modes respectively denoted with the corresponding dof. Notice that the fixed interface normal modes have different shapes and frequencies from those obtained in the NM as obtained constraining the boundary nodes of the connecting rod.

Table 4 reports the RMS error \(\epsilon _{RMS}\) of the mid-span node \(G_{2}\) increasing the number of modes m retained in the corresponding reduced model. For both GM and NM, m is the number of the retained global or local normal modes while it corresponds to the number of fixed interface normal modes for CB. All CB models include five static constraints deriving from the boundary conditions, therefore leading to a total number of \(5+m\) local modes.

The trajectory of the mid-span node \(G_{2}\) is reported in Fig. 7 for FM and GM, the latter obtained using the first three flexible global modes plotted in Fig. 4. For both GM and NM, it can be observed that only two modes are necessary to achieve an error below \(2 \times 10^{-5}\) (m). This result can be interpreted by observing that the first two global modes include the first two bending modes of the connecting rod. The third global mode pertains to a bending mode of the same body with higher frequency, as confirmed by the inflection point in Fig. 4. The contribution of this mode is of little relevance for the accuracy of the solution and could be removed or replaced with other modes.

The results of CB are slightly less accurate than NM and GM. This is not surprising since the accuracy of CB depends on multiple factors such as boundary conditions used, number and position of boundary nodes, output node. In this regard, the output node \(G_{2}\) is an inner point for CB, that is, a node that is condensed in the reduced model. Repeating the analysis for the node in the center of the spherical joint between the crank and the connecting rod, and considering \(m=1\), the values of \(\epsilon _{RMS}\) are \(8.88\times 10^{-10}\) for NM/GM and \(4.54\times 10^{-10}\) for CB, respectively. This result confirms what is already known for the CB method, the accuracy obtained in boundary nodes is usually greater than that obtained in internal nodes.

5.2 \(N\)-link system

In this second application, the benchmark example of a spatial pendulum composed of multiple flexible links has been investigated. The links are connected through revolute joints with axes parallel to the \(y\)-axis and are subject to their weights. Spatial Euler–Bernoulli beam elements have been employed to model the links. The simulations have been carried out imposing a law of motion, as a function of time \(t\), to the angle \(\theta _{1}\) (rad) of the first revolute joint, i.e.,

The end-point trajectories for the case with four links have been plotted in Fig. 9. Table 5 reports the values of \(\epsilon _{RMS}\) for each end-point and the number \(n_{b}\) of flexible links varies from 2 to 10 bodies with increments of two bodies. The results for GMs have been obtained maintaining constant the total number of retained modes, i.e., \(m=6\). The accuracy of the results produced by the proposed method remains very high using a small set of global modes even when the complexity of the mechanical multibody system increases. The results for NM are not so accurate and the accuracy is two order of magnitude lower than the other methods. The results for GMc are more accurate, but comparable, than GMs, even if the number of retained modes grows up to \(n_{b}\cdot m\), and very similar to the results of CB. The latter has the best results for a limited number of bodies while GMc is more accurate when the number of bodies grows. Summarizing, comparing all methods, GMc and CB are the most accurate reduction methods even if GMs still produces very accurate results even retaining the smallest number of modes.

As for the CMS methods NM and CB, the total calculation time of the proposed GM methods remains almost unchanged by increasing the number of flexible coordinates. Small deviations in the calculation times are, however, expected as changing the number of flexible elements means changing the bases that will be used for the reductions. If the partitions chosen are still adequate to reproduce the flexible behavior of the components, or of the entire system, the chosen bases will not differ significantly and as a consequence, the calculation times will be similar.

As revealed in Fig. 10 and as it was expected by observing the computational complexity in Table 2, the CPU-time needed by FM is increased passing from 5 to 10 finite elements to model each link. The total complexity for GMs increases only by increasing the number of flexible bodies \(n_{b}\) or the number of retained global modes \(m\). By substituting \(f_{i} = 10\times 6 \equiv 60\), \(\forall i =1,\ldots , n_{b}\), and \(k=m\) in Table 2, the total complexity of FM is about 126 time higher than GMs regardless the number of bodies \(n_{b}\) considered in the system, i.e., when the same partition is employed for all links the number of bodies \(n_{b}\) can be factored out and simplified to evaluate the complexity-ratio of the two models. The complexity of the component-mode methods NM, CB, and GMc depends on the number of flexible bodies and retained modes for each component, here chosen to be the same for a fair comparison. Although the number of elastic parameters is equal to \(n_{b}*m\) for each CMS methods, both based on local or global modes, while it is equal to m for GMs, the simulation times are very different. The constant amount of computational resources, required to assemble the generalized mass matrix and the vector of forces, is only a part of the global complexity and can not justify the different CPU-times shown in Fig. 10. As already announced in Sect. 4 and Fig. 6, the computation of the increments (block \(B_{2}\)) is the most time-consuming part. The increments of coordinates and Lagrangian multipliers are evaluated using LU decomposition of the sparse generalized tangent stiffness matrix and subsequent back-substitution, refer to [3, 5] for details. Permuting the sparse generalized tangent stiffness matrix for FM through the Reverse Cuthill–McKee algorithm [14] yields a band-matrix with a small bandwidth, here equal to 74. Similar results, but with smaller bandwidths can be obtained for the CMS methods. Contrary to the previous models, calculating the nested dissection ordering of the sparse generalized tangent stiffness matrix for GMs places the dense columns referred to the global intensities to form a pattern that can be turned into an arrowhead banded sparse matrix. The corresponding sparsity patterns of the reordered matrices are shown in Fig. 11 for FM and GMs, respectively.

The complexity computation of block \(B_{2}\) goes beyond the purposes of this article and it is still an open issue for sparse matrices. Here, it was preferred to evaluate the mean CPU-time for the calculation of the increments. The numerical results for the full and reduced models are reported in Fig. 12. The mean value of the time required to find the increments is calculated using all instants of time and is plotted as a function of the number of coordinates of the system \(n_{tot}\) referred to FM. Here, \(n_{tot}\) has been preferred to \(n_{b}\) as it has the dimension of the generalized tangent stiffness matrix taking into account both the number of rigid/flexible coordinates \(n_{dof}\) and the number of constraints \(n_{doc}\) introduced by the spatial revolute joints and the prescribed motion, i.e.,

This approach makes the CPU-time more reliable and less subject to sources of error deriving from internal processes. It should be borne in mind that this time also includes other operations such as creating and updating variables. To limit the influence of this aspect, a single Matlab code has been implemented to simulate all methods.

Mean CPU-time for the calculation of the increments as in block \(B_{2}\) of Fig. 6. The number of coordinates of the system \(n_{tot}\) refers to FM

NM and CB provides similar results and their mean CPU-time grows since the size of the final system grows proportionally to the number of flexible bodies. As a matter of fact, both the rigid and elastic coordinated depend on the number of flexible bodies.

Contrary to what one might expect, GMc is faster than GMs despite having a number of coordinates \(n_{b}\) times greater than GMs. This is not surprising because the CPU required depends on factors such as the sparsity pattern and conditioning of the generalized tangent stiffness matrix.

5.3 The Sarrus-type six-link mechanism

The third example is the six-link mechanism of Sarrus-type shown in Fig. 13, [12]. This spatial mechanism is overconstrained and has a closed-kinematics composed of two limbs and six links: a fixed frame, two proximal links, two distal links, and a moving platform. Each limb is a 3R mechanism, R stands for the revolute joint, that starts from the fixed frame and arrives to the moving platform. The three R of each limb are parallel to each other and aligned along the x-axis, for the first limb, and along the y-axis, for the second limb, respectively. The moving platform is constrained to move along the z-axis only while the remaining dof are restrained. Here, the proximal and distal links are modeled as flexible bodies while the moving platform is modeled as a rigid body. The parameters used in this case study are reported in Table 6.

As for the previous example, all simulations have been carried out considering the full model FM, the models GMs and GMc employing global flexible modes, the normal mode approach NM, and the Craig–Bampton method CB. The center of the moving platform, i.e., point E, has been selected as a reference point for the comparison of the three reduced models.

The case study considers the mechanism at rest falling down from a given configuration due to its own weight. If the mechanism were rigid, the trajectory of point E should remain straight during the rebounds. The presence of flexibility in the links produces undesired displacements in the x–y plane, making the trajectory deviate from the ideal straight one. In Fig. 14, the position vector \(\mathbf{p}_{xy}^{E}\) of E in the x–y plane, i.e., along with the theoretically constrained directions, and the z-component \(\mathbf{p}_{z}^{E}\) along the dof in the vertical direction have been separated into two subplots to better highlight the difference between the FM and the reduced models.

Observing the Fig. 14, both GMs and NM have reduced or amplified magnitudes and phase lag and are not able to reproduce correctly the position of the end-effector point. This shortcoming is not present implementing the CB model and its results are very close to the FM, as confirmed in Table 7 where the RMS error of \(\mathbf{p}^{E}\) is reported for various reduced models. Notice that the number in round parentheses represents the total number of parameters employed in the reduced model.

The reason that GMs fails to reproduce FM results with greater accuracy is related to using the global flexible modes of the whole mechanism as elastic parameters of the reduced model. To explain this concept, let us refer to the Fig. 15 in which the first four global flexible modes of the six-link mechanism, as obtained at the linearization configuration that the mechanism has when \(\mathbf{p}^{E} = [0.282,0.282,-0.031]\), are displayed. It is noteworthy that this configuration generally does not coincide with the initial configuration of the simulation. For example, the initial configuration has been set considering the end-effector at the position given by \(\mathbf{p}_{0}^{E} = [0.282,0.282,0]\) for all simulations. When the global flexible modes of the whole mechanism are employed as elastic parameters of the reduced model, the latter can deform following the superposition of a prescribed set of global modes, in this case, given by the four modes displayed in Fig. 15. While this strategy minimizes the elastic parameters of the ROM, sometimes it makes the system too plastered and unable to deform freely. As it can be observed in Table 7, even using a fairly high number of global modes the convergence speed of GMs remains very low.

In Fig. 16, the same four global modes of Fig. 15 are employed to create four component-modes for each flexible body, i.e., the two proximal and two distal links, of the mechanism. These component-modes are not normal as in the NM, nonetheless, they can form a basis for GMc able to represent the elastic field of the flexible parts. Observing the results of GMc in Table 7, we realize that GMc is faster to converge and more accurate than CB. This result has been pointed out in [9] for the planar case, but here is confirmed also for the spatial mechanisms. Comparing the two reduced models CB(\(4 \times [5{s}+2{m}\)]) and GMc(\(4\times 7\)m), using both 28 elastic parameters, the RMS-error almost halves from \(0.220\times 10^{-5}\) (m) to \(0.128\times 10^{-5}\) (m). Like the component-modes used for NM and CB, those of GMc are not only compatible with the reference conditions defined in the floating frames but also with the joints, being derived from the assembled multibody system. Another important distinction is that the global modes refer to the eigenfrequencies of the whole mechanism, which are considerably lower than those of the single component. In addition to what has been explained in [9], here a possible criterion to establish the number of global modes that are necessary to define reliable base functions for GMc is formulated. From Eq. (14), the analogue of the participation mass \(\overline{m}_{i}\) can be defined as

where \(\varPsi _{i}\) is the generic global flexible mode and \(\mathbf{M}\) is the mass matrix evaluated at the linearization point. These masses can be used to scale the global modes in order to increase the conditioning of the system, i.e., \(\overline{\varPsi }_{i} = \varPsi _{i}/\sqrt{\overline{m}_{i}}\). Furthermore, \(\bar{m}_{i}\) contains information on the importance of a global flexible mode indicating the mass/inertia that participates in that particular global mode. Table 8 reports the first twenty participation masses \(\overline{m}_{i}\) of the system. Using these data to understand the results of GMc in Table 7, we notice that adding the ninth global mode could improve the accuracy of GMc. As a matter of fact, the RMS-error lowers up to \(1.092\times 10^{-6}\) (m).

6 Discussion and conclusions

Global modes can be a viable alternative to traditional reduction methods to reduce the complexity of applying the FRFF to flexible multibody systems. Being obtained from the linearization of the governing equations of motion of the assembled system, the global modes satisfy the constraints and contain information on the dynamics of the whole system. It is known how the presence of mechanical joints relaxes, in a certain sense, and modifies the frequency range of a mechanism. Global modes contain shapes and refer to frequencies that belong to the assembly and not to the individual components. However, as demonstrated in the examples, they can be used to form a valid modal basis even at the level of a single component. However, determining the global modes for systems with a high number of flexible coordinates involves a preliminary eigenvalue analysis that can be complex. Limiting the number of global modes required can be a strategy to reduce the computational load in the preprocessing phase. Another strategy, to be investigated in the future, might go through a preliminary reduction process of the individual complex components followed by a second reduction process based on global modes.

Another important aspect is related to the choice of the linearization configuration. The numerical results obtained in terms of RMS error have shown how the ROM manages to reproduce the results of the nonreduced model for the entire duration of the simulation. This is interpreted by recalling that the set of global flexible shapes obtained in a given configuration forms a basis capable of representing the dynamics of the flexible components also in other configurations. However, although the choice of a given linearization configuration did not lead to drift errors in the solution of the ROM, it cannot be excluded that there are configurations better than others or that the method can be extended to any model. Systems in the presence of collisions, or with variable topologies generate complex dynamics that are difficult to capture using a single linearization point. For such systems, strategies based on different mappings that can interchange based on the occurrence of events can be implemented.

The numerical simulations showed comforting results in terms of computational load reduction and accuracy in the ROM results. It has been observed that a limited number of global modes are enough to be able to capture the dynamic content of a flexible system with an open-kinematic chain even when the system increases its complexity by increasing the number of flexible components.

Differently, departing from the planar formulation presented in [9], the closed-kinematic chain spatial mechanism pointed out that the global modes do not always form adequate base functions in approximating the elastic field of flexible multibody systems. Sometimes, the superposition of the global modes excessively limits the deformation capacity of the mechanism, which becomes more rigid than it should, while the speed of convergence towards the solution of the complete model decreases drastically. Fortunately, in such cases, the global modes can be used to reduce each individual component in the same way as for a classic CMS method. The results showed that the accuracy of a CMS method based on global modes can be better than a classic CMS reduction method developed using local modes. Finally, a criterion based on the participation of the global modes to be included in the final ROM has been provided.

References

Agrawal, O.P., Shabana, A.A.: Dynamic analysis of multibody systems using component modes. Comput. Struct. 21(6), 1303–1312 (1985)

Agrawal, O., Shabana, A.: Application of deformable-body mean axis to flexible multibody system dynamics. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 56(2), 217–245 (1986)

Arnold, M., Brüls, O.: Convergence of the generalized-\(\alpha \) scheme for constrained mechanical systems. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 18(2), 185–202 (2007)

Bai, Z.: Krylov subspace techniques for reduced-order modeling of large-scale dynamical systems. Appl. Numer. Math. 43(1–2), 9–44 (2002)

Bauchau, O.A.: Flexible Multibody Dynamics, vol. 176. Springer, Berlin (2010)

Bottasso, C.L., Dopico, D., Trainelli, L.: On the optimal scaling of index three DAEs in multibody dynamics. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 19(1–2), 3–20 (2008)

Brüls, O., Duysinx, P., Golinval, J.C.: The global modal parameterization for non-linear model-order reduction in flexible multibody dynamics. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 69(5), 948–977 (2007)

Cammarata, A.: Full and reduced models for the elastodynamics of fully flexible parallel robots. Mech. Mach. Theory 151, 103895 (2020)

Cammarata, A.: Global flexible modes for the model reduction of planar mechanisms using the finite-element floating frame of reference formulation. J. Sound Vib. 489, 115668 (2020)

Cammarata, A., Pappalardo, C.M.: On the use of component mode synthesis methods for the model reduction of flexible multibody systems within the floating frame of reference formulation. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 142, 106745 (2020)

Cardona, A., Geradin, M.: Time integration of the equations of motion in mechanism analysis. Comput. Struct. 33(3), 801–820 (1989)

Chu, J.S.Z.F., Feng, Z.J.: Mobility of spatial parallel manipulators. In: Parallel Manipulators, Towards New Applications. (2008). IntechOpen

Craig, R.R., Bampton, M.C.: Coupling of substructures for dynamic analysis. AIAA J. 6(7), 1313–1319 (1968)

Cuthill, E., McKee, J.: Reducing the bandwidth of sparse symmetric matrices. In: Proceedings of the 1969 24th National Conference, pp. 157–172 (1969)

Eberhard, P., Schiehlen, W.: Computational dynamics of multibody systems: history, formalisms, and applications. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. 1(1), 3–12 (2006)

Fehr, J., Eberhard, P.: Simulation process of flexible multibody systems with non-modal model order reduction techniques. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 25(3), 313–334 (2011)

Fehr, J., Holzwarth, P., Eberhard, P.: Interface and model reduction for efficient explicit simulations-a case study with nonlinear vehicle crash models. Math. Comput. Model. Dyn. Syst. 22(4), 380–396 (2016)

Friberg, O.: A method for selecting deformation modes in flexible multibody dynamics. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 32(8), 1637–1655 (1991)

Han, J.B., Kim, J.G., Kim, S.S.: An efficient formulation for flexible multibody dynamics using a condensation of deformation coordinates. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 47(3), 293–316 (2019)

Han, S., Kim, J.G., Choi, J., Choi, J.H.: Iterative coordinate reduction algorithm of flexible multibody dynamics using a posteriori eigenvalue error estimation. Appl. Sci. 10(20), 7143 (2020)

Heirman, G.H., Desmet, W.: Interface reduction of flexible bodies for efficient modeling of body flexibility in multibody dynamics. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 24(2), 219–234 (2010)

Heirman, G.H., Naets, F., Desmet, W.: A system-level model reduction technique for the efficient simulation of flexible multibody systems. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 85(3), 330–354 (2011)

Kim, S.S., Haug, E.J.: Selection of deformation modes for flexible multibody dynamics. J. Struct. Mech. 18(4), 565–586 (1990)

Kim, J.G., Lee, P.S.: An enhanced Craig–Bampton method. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 103(2), 79–93 (2015)

Kim, J.G., Han, J.B., Lee, H., Kim, S.S.: Flexible multibody dynamics using coordinate reduction improved by dynamic correction. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 42(4), 411–429 (2018)

Kobayashi, N., Wago, T., Sugawara, Y.: Reduction of system matrices of planar beam in ANCF by component mode synthesis method. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 26(3), 265–281 (2011)

Korkealaakso, P., Mikkola, A., Rantalainen, T., Rouvinen, A.: Description of joint constraints in the floating frame of reference formulation. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng., Part K, J. Multi-Body Dyn. 223(2), 133–145 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1243/14644193JMBD170

Krattiger, D., Wu, L., Zacharczuk, M., Buck, M., Kuether, R.J., Allen, M.S., Tiso, P., Brake, M.R.: Interface reduction for Hurty/Craig–Bampton substructured models: review and improvements. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 114, 579–603 (2019)

Lehner, M., Eberhard, P.: On the use of moment-matching to build reduced order models in flexible multibody dynamics. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 16(2), 191–211 (2006)

Lugrís, U., Naya, M., Luaces, A., Cuadrado, J.: Efficient calculation of the inertia terms in floating frame of reference formulations for flexible multibody dynamics. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng., Part K, J. Multi-Body Dyn. 223(2), 147–157 (2009)

Masoudi, R., Uchida, T., McPhee, J.: Reduction of multibody dynamic models in automotive systems using the proper orthogonal decomposition. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. 10(3), 031007 (2015)

Naets, F., Desmet, W.: Super-element global modal parameterization for efficient inclusion of highly nonlinear components in multibody simulation. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 31(1), 3–25 (2014)

Naets, F., Heirman, G., Vandepitte, D., Desmet, W.: Inertial force term approximations for the use of global modal parameterization for planar mechanisms. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 85(4), 518–536 (2011)

Naets, F., Tamarozzi, T., Heirman, G.H., Desmet, W.: Real-time flexible multibody simulation with global modal parameterization. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 27(3), 267–284 (2012)

Nowakowski, C., Fehr, J., Fischer, M., Eberhard, P.: Model order reduction in elastic multibody systems using the floating frame of reference formulation. IFAC Proc. Vol. 45(2), 40–48 (2012)

Orzechowski, G., Mikkola, A.M.: Boundary conditions and Craig–Bampton substructuring technique with free-free modes. In: ASME 2017 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference, p. V006T10A023 (2017). American Society of Mechanical Engineers

Orzechowski, G., Matikainen, M.K., Mikkola, A.M.: Inertia forces and shape integrals in the floating frame of reference formulation. Nonlinear Dyn. 88(3), 1953–1968 (2017)

O’Shea, J.J., Jayakumar, P., Mechergui, D., Shabana, A.A., Wang, L.: Reference conditions and substructuring techniques in flexible multibody system dynamics. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. 13(4), 041007 (2018)

Shabana, A.A.: Dynamics of Multibody Systems. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2013)

Shabana, A.A.: Computational Continuum Mechanics. Wiley, New York (2018)

Shabana, A.: Dynamics of Multibody Systems. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2020)

Shabana, A.A., Wang, G.: Durability analysis and implementation of the floating frame of reference formulation. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng., Proc., Part K, J. Multi-Body Dyn. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1177/1464419317731707

Shabana, A.A., Wang, G., Kulkarni, S.: Further investigation on the coupling between the reference and elastic displacements in flexible body dynamics. J. Sound Vib. 427, 159–177 (2018)

Shin, S.H., Yoo, W.S., Tang, J.: Effects of mode selection, scaling, and orthogonalization on the dynamic analysis of flexible multibody systems. J. Struct. Mech. 21(4), 507–527 (1993)

Tang, Y., Hu, H., Tian, Q.: Model order reduction based on successively local linearizations for flexible multibody dynamics. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 118(3), 159–180 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/nme.6011

Winfrey, R.C.: Dynamic analysis of elastic link mechanisms by reduction of coordinates. J. Eng. Ind. 94(2), 577–581 (1972)

Witteveen, W., Pichler, F.: On the relevance of inertia related terms in the equations of motion of a flexible body in the floating frame of reference formulation. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 46(1), 77–105 (2019)

Zwölfer, A., Gerstmayr, J.: Co-rotational formulations for 3d flexible multibody systems: a nodal-based approach. In: Contributions to Advanced Dynamics and Continuum Mechanics, pp. 243–263. Springer, Berlin (2019)

Zwölfer, A., Gerstmayr, J.: A concise nodal-based derivation of the floating frame of reference formulation for displacement-based solid finite elements. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 49(3), 291–313 (2020)

Zwölfer, A., Gerstmayr, J.: Consistent and inertia-shape-integral-free invariants of the floating frame of reference formulation. In: ASME 2020 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference. (2020). American Society of Mechanical Engineers Digital Collection

Zwölfer, A., Gerstmayr, J.: The nodal-based floating frame of reference formulation with modal reduction. Acta Mech. 232(3), 835–851 (2021)

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Catania within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cammarata, A. Global modes for the reduction of flexible multibody systems. Multibody Syst Dyn 53, 59–83 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11044-021-09790-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11044-021-09790-0