Abstract

I examine how one central aspect of the family environment—sibling sex composition—affects women’s gender conformity. Using Danish administrative data, I causally estimate the effect of having a second-born brother relative to a sister for first-born women. I show that women with a brother acquire more traditional gender roles as measured through their choice of occupation and partner. This results in a stronger response to motherhood in labor market outcomes. As a relevant mechanism, I provide evidence of increased gender-specialized parenting in families with mixed-sex children. Finally, I find persistent effects on the next generation of girls.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Across most OECD countries, women today attain more education than men and participate almost equally in the labor force (OECD 2016, 2017). But why do women keep choosing fields of study that lead to substantially lower-paid occupations (Blau and Kahn 2017)? Although societies have removed barriers to women’s participation in education and the labor force in an attempt to achieve gender equality, gender norms still play an important role for gender differences in behavior and, subsequently, economic outcomes (Akerlof and Kranton 2000; Bertrand 2011; Goldin 2014). In particular, unlike men, women still experience a substantial drop in labor earnings upon becoming a parent, in large part due to a decreased labor supply (Kleven et al. 2019). To better understand why women continue to behave in ways that lead to inferior labor market outcomes relative to those of men, it is essential to know more about the origins of women’s conformity to traditional gender norms.Footnote 1 In this study, I focus on the importance of one key aspect of the childhood family environment—sibling sex composition—for women’s socialization and development of gender conformity.

To examine how sibling sex composition affects the development of women’s gender conformity, I use high-quality administrative data on the Danish population from 1980 to 2016. With this comprehensive dataset, I evaluate women’s conformity to traditional gender norms as measured through their choice of occupation and partner between ages 31 and 40 (proxied by the gender share in their own and their partner’s occupations, respectively). I further complement these measures of gender conformity with an examination of whether sibling sex differentially affects women’s response to motherhood in terms of labor supply and earnings. To examine gender-specific parenting as a relevant mechanism, I additionally link the administrative data to rich survey data.

To provide causal estimates of the impact of sibling sex, I exploit the random variation in the second child’s sex in families with a first-born daughter, conditional on the parents’ having a second child. In other words, I compare the gender conformity of first-born women with a second-born brother to those with a second-born sister. While sibling sex composition has a small impact on family size, I show that family size is not a confounding factor for the effect of sibling sex composition on women’s gender conformity. This empirical approach distinguishes itself from most previous studies on sibling sex composition, which generally includes all siblings in both the measure of sibling sex composition and the estimation sample. However, as the final sibling sex composition in a sibship is endogenous, including all siblings might lead to biased estimates. By focusing on the second-born child’s sex, I avoid selection bias, as parents do not know the sex of their unborn child when deciding to have another child.

My results show that having a second-born brother relative to a sister increases first-born women’s conformity to traditional gender norms. Specifically, women with a brother work in more female-dominated occupations during their thirties and choose more traditional partners. I next document that women with a brother experience a larger drop in labor earnings and accumulate less working experience from the time of their first childbirth through 9 years after, relative to women with a sister. What is even more striking is that this response to the arrival of the first child is entirely driven by women growing up in traditional families.Footnote 2 This effect on women’s gender conformity already appears in their first educational choice after compulsory education at age 16. In other words, the random event of the arrival of a brother to the family instead of a sister changes these women’s socialization within the family to such an extent that they are on a different career path early on.

So how does sibling sex affect women’s conformity to traditional gender roles? I provide compelling evidence that an important channel is parents’ response to their children’s sex composition in terms of gendered parenting. Drawing on rich survey data, I examine mothers’ and fathers’ quality time investment in their first-born daughter during childhood and show that parents of mixed-sex children invest their time more gender-specifically compared with parents of same-sex children. This empirical pattern is consistent with a traditional household specialization model with gender-specific parenting human capital (Becker 1973; Becker and Tomes 1986). Mothers might have better knowledge than fathers of problems facing daughters and therefore have the comparative advantage of raising daughters, and vice versa for fathers and sons. Therefore, it would be optimal for the parents to gender-specialize their parenting in mixed-sex families by having the mother spend more time with the daughter and the father more time with the son. This suggests that parents of mixed-sex children more strongly transmit gender-specific human capital and thereby traditional gender norms to their daughters than parents of same-sex children. The results from heterogeneity analyses further show that the effect of having a brother is strongest for women from more traditional families.

The key finding that women with a brother acquire more gender-typed human capital and pair with more gender-conforming men implies that they end up creating a more gender-stereotypical family environment for their children. Remarkably, I further show that the effect of sibling sex carries over to the next generation of girls: daughters’ comparative advantage in language over math in school is larger for those from more traditional families (i.e., for daughters of mothers with a brother relative to daughters of mothers with a sister). Thus, I find evidence of persistent long-run consequences of women’s childhood family environment. This demonstrates that women are not only sensitive to the gender role environment shaped in the family after their younger sibling’s birth (caused by sibling sex composition and unrelated to parents’ human capital), but girls are also sensitive to the degree of gender norms in their family environment already shaped before their birth (parents’ gendered human capital).

In the existing literature, only a few related studies investigate how a sibling’s sex causally affects labor earnings.Footnote 3 Two recent studies find, similar to my findings, that women with a next-youngest brother experience lower earnings than those with a sister. Cools and Patacchini (2019) consider self-reported earnings around age 30 for cohorts born in the late 1970s and early 1980s in the USA,Footnote 4 while Peter et al. (2018) consider the average earnings between ages 25 and 64 for cohorts born in 1938–1977 using Swedish registry data.Footnote 5Cools and Patacchini (2019) suggest that their findings can be explained by lower parental investment (as measured through expectations and schoolwork monitoring) and more family-centered behaviors (fewer work hours and higher desired fertility). In contrast, Peter et al. (2018) find that women with a younger brother are slightly less likely to ever marry and have children,Footnote 6 while there is no effect on the total number of children. Instead, they argue that the negative effect of having a brother on women’s earnings could occur through increased unemployment, as the job search network of brothers is less relevant than the one of sisters.

I complement these two recent studies and contribute more broadly to the literature studying how the social (in particular, the family) environment affects women’s conformity to traditional gender norms in three important ways. First, I provide a comprehensive and rigorous analysis of how sibling sex composition causally affects the development of women’s gender conformity, using three unique measures (choice of occupation, choice of partner, and the response to motherhood in labor market outcomes).Footnote 7Footnote 8 By focusing on the development of women’s gender conformity, I rigorously examine a potentially important underlying mechanism for the earnings effect. In particular, to reconcile the existing evidence of a “brother earnings penalty” with my findings on a differential response to motherhood by sibling sex, I show that the negative effect of having a brother on women’s earnings emerges exactly around the age when most women have their first child. Thus, the timing of the measurement of women’s earnings is crucial for understanding the underlying mechanisms of the brother earnings penalty in a modern setting with equal labor market performance between men and women prior to first childbirth (Kleven et al. 2019).

Second, I conduct a large quantitative analysis of how sibling sex composition affects child-parent interactions, thereby providing evidence on a potentially important channel through which the effects on gender conformity operate. Third, I document lasting effects on the next generation of girls, thereby stressing the persistence of gender norms. Importantly, such analysis is only possible thanks to the rich and extensive data, including administratively reported family links.

2 Empirical strategy

The aim is to estimate the causal effect of sibling sex composition on the formation of women’s gender conformity. However, simply comparing women from families with different sex compositions would not provide valid estimates of the causal effect of sibling sex composition due to selection. The final gender composition in a family is endogenous, as parents decide whether to have more children after the birth of each child and thus know their current children’s sex composition. If parents’ decision to have a second child depends on the first child’s sex and if such sex preferences also affect how parents raise their children, it is not possible to estimate the causal effect of “current” (first-born) children’s sex on “future” (second-born) children’s outcomes because not all “future” children are born.

To estimate the causal effect of sibling sex composition, I focus on the random assignment of the second-born child’s sex. Because parents do not know the sex of a subsequent child when they decide to have another child, I can causally estimate the effect of a second-born child’s sex on first-born children’s outcomes. Thus, I leverage the random assignment of the second child’s sex in families with a first-born daughter, conditional on having a second child. In other words, I compare first-born women who have a second-born brother with first-born women who have a second-born sister. Thus, the identifying assumption is that conditional on the first child’s sex and conditional on having a second child, the sex of the second child is random.Footnote 9

The empirical specification for the main analysis is:

where \(Y_{i}^{First-Born}\) measures woman i’s (who is first-born) gender conformity. The estimate of interest is α1, representing the effect of having a second-born brother. Xi is a vector of fixed effects for birth municipality, year-by-month of birth, spacing in months to the second-born sibling, maternal age at birth, paternal age at birth, maternal level-by-field of education, and paternal level-by-field of education.Footnote 10νi is the error term.

As this strategy only relies on the random variation in the second child’s sex, parents can respond to the sex composition of their first two children in terms of subsequent fertility. Consistent with the literature exploiting sibling sex composition as an instrument for family size (e.g., Angrist and Evans 1998), Appendix Table 8 shows that for the main sample of the analysis (described in Section 3) having two mixed-sex children reduces family size by 0.07 children on average. Therefore, family size could potentially mediate some of the effect of having a second-born brother if family size has an independent impact on gender conformity. Existing studies find that family size does not affect educational attainment in Israel or Norway using twins as an instrument for family size (Angrist et al. 2010; Black et al. 2005). Appendix B.1 of Brenøe (2021) replicates this finding in the Danish context and shows that family size also does not affect the different measures of gender conformity. This appendix also provides additional tests of the sensitivity of the findings, which further lend support to the conclusion that the results are robust to family size. Based on this wide battery of tests, family size does not seem to be an important confounder or mediator of the effect of sibling sex.

To reach a comprehensive picture of women’s conformity to gender norms, I further examine whether first-born women with a second-born brother to a greater extent conform to traditional gender roles upon motherhood in terms of labor market outcomes than those with a second-born sister. For this, I consider women’s labor market trajectory relative to their first childbirth by sibling sex in an event study framework. The difference-in-differences specification is:

where \(L_{it}^{First-Born}\) is the woman’s labor market outcome (labor supply and earnings) in year t relative to her first childbirth and γi represents individual fixed effects. Timeik is a series of event year dummies (i.e., dummy variables for event years − 6 to 9, excluding the calendar year of childbirth which is coded as year 0), where the event is entry into motherhood, i.e., the woman’s first childbirth. I estimate this regression specification from 6 years prior to the arrival of the first child through 9 years following the birth to rigorously test for pre-trends and to allow for dynamic effects occurring well after the first childbirth. For this analysis, it is important to note that I do not find evidence of any meaningful effect of sibling sex on fertility outcomes, neither in terms of the probability of having any children nor the age at first childbirth (Table 5). Thus, focusing on the sub-sample of women with any children and centering the analysis around the timing of the first childbirth should not introduce any selection issue.

3 Data

3.1 Data and sample selection

I use Danish administrative data for the total population from 1980 to 2016. One central feature of this dataset compared to most previous studies on sibling sex composition is that I can link all children to their parents, siblings, (cohabiting and marital) partners, and own children. Thus, I observe parents’ complete fertility history and thereby correctly measure the sibling sex composition. Furthermore, I have information on parents’ date of birth, length, type, and field of education, labor market attachment, and occupation. For the children, I annually observe labor market outcomes, educational enrollment and completion, fertility, cohabitation, and marital status. Finally, I observe the school performance of the grandchildren.

I restrict the sample to women born between 1962 and 1975 to study the choice of occupation and partner when these women are in their thirties. Moreover, I only include first-born women, who are the first child to both the mother and father. I exclude immigrants.Footnote 11 I only consider individuals who have at least one full sibling (same mother and father) born less than 4 years apart and who survived the first year of life.Footnote 12 I exclude families in which either the first or second child is a twin, and finally I exclude those few women who died before the age of 40 or did not live in Denmark at any time between the ages of 31 and 40, when the main outcome variables are measured.Footnote 13 I refer to this sample of first-born women as the main sample.

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics on the childhood family environment for the main sample by the sex of the second-born sibling. As expected, these women come from families with similar predetermined family characteristics regardless of sibling sex. On average, spacing to the younger sibling is 2.5 years, mothers (fathers) are 22.9 (25.7) years at birth and have 10.9 (11.8) years of education. In terms of characteristics, parents can manipulate after realizing the sex composition of their first two children, those with two daughters are more likely to have more children, as discussed in Section 2. Meanwhile, the probability of having both parents working equally during childhood (and thus coming from a non-traditional family) does not differ by sibling sex composition. I define this variable (parents working equally) as the tertile of families in which the parents’ division of labor until the child turns 19 years is most equal. More precisely, fathers in this group work at most 62% of the total parental labor supply.Footnote 14 Neither does the probability of living with both biological parents at the age of 17 differ by sibling sex composition.

To provide support for the identifying assumption that sibling sex is random, column (5) in panel A tests whether the background characteristics differ by the sex of the second-born sibling. Considering the predetermined characteristics, only the father’s age at birth differs marginally between the two groups. Panel B shows statistics from a balancing test that tests whether the demographic characteristics included in Xi in Eq. 1 can predict sibling sex. The F-test strongly rejects joint significance and thus supports the identifying assumption.Footnote 15

3.2 Outcome variables

The three main outcome variables evaluate the degree of women’s gender conformity. The first outcome reflects the extent to which the individual woman’s occupational choice is gender-typed. More precisely, I construct this variable as the natural logarithm of the average male share in the woman’s four-digit occupation codes observed between the ages of 31 and 40.Footnote 16 The second outcome measures the share of years between the ages of 31 and 40 during which the woman works in a high-skilled STEM occupation. The choice of this outcome is particularly motivated by the recent focus in the literature on women shying away from STEM fields, fields that are traditionally high-paid and heavily male-dominated. The third outcome quantifies how traditional the woman’s choice of partner is. This variable measures the natural logarithm of the female share in the partner’s occupation.Footnote 17 Table 2 provides descriptive statistics on the outcome variables for the main sample of women by sibling sex and for a sample of men with similar selection criteria as for the main sample, for comparison. We observe a strong degree of gender segregation in occupational choice.

To study whether the impact of motherhood causes a differential response on labor market outcomes by sibling sex, I further consider labor force participation and earnings in relation to the arrival of the first child.Footnote 18 As a measure of labor force participation, I examine the cumulated lifetime work experience at the end of each calendar year, measured in months. Supported by the findings in Kleven et al. (2019), I consider this measure of employment (i.e., the intensive margin) the most relevant measure of labor force participation rather than participation at the extensive margin.Footnote 19 This measure of work experience corresponds to full-time equivalent working experience and accounts thereby for periods of (different degrees of) part-time work; periods of un- or non-employment do not enter as work experience, while maternity and parental leave spells do count. As a measure of earnings, I use the earnings percentile by age and cohort, which provides a standardized measure of relative income that includes individuals with zero earnings, is comparable across cohorts and ages, and is constructed based on the total population. For robustness checks, I also consider earnings measured in levels and log-transformed and cumulated lifetime unemployment, measured in months at the end of each calendar year.

Furthermore, I examine whether sibling sex affects education by age 30 and family formation through age 41. The educational outcomes include the length (in months) and male share of the highest completed education, academic high school grade-point-average (GPA), and any field-specific STEM enrollment and completion. The family formation outcomes include the share of years between ages 18 and 41 during which the woman cohabits without being married (henceforth cohabit) and is married, respectively, the probability of having any children, the number of children, and age at first childbirth conditional on having any children. Although having a partner (and being married) and having children might reflect a greater degree of gender-stereotypical behavior, this is not inevitably the case (Bertrand et al. 2020); instead, cohabitation could reflect non-traditional behavior, given that marriage is the tradition.

Finally, the last group of outcomes concerns the school performance of the next generation. For this, I consider the outcomes of the first-born child and split the sample by the child’s sex.Footnote 20 I examine the externally graded GPA from the Grade 9 written language (Danish) and math exams. Both measures are standardized with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation (SD) of 1 by exam year for the entire student population.

4 Results

This section presents the results on the effect of sibling sex on women’s adult outcomes and their children’s school performance, using the main sample. Section 4.1 provides the main results of the paper by eliciting the effect of sibling sex on women’s gender conformity in terms of their (1) choice of occupation and partner and (2) differential response to motherhood in labor market outcomes. Next, Section 4.2 considers the role of education and family formation as potential channels of the effects on labor market outcomes. Finally, Section 4.3 examines whether the effects persist to the next generation by studying the school performance of the children of the women in the main analysis.

4.1 Gender conformity

4.1.1 Choice of occupation and partner

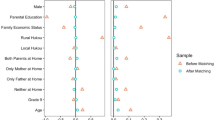

Figure 1 illustrates the main results on the impact of having a second-born brother compared to a sister on women’s choice of occupation and partner. Overall, having a brother enhances women’s conformity to traditional gender norms. First-born women with a second-born brother work in occupations with 1.2% fewer men compared to first-born women with a second-born sister. Note that this difference in occupational choice is observed well into these women’s labor market careers during their thirties (as an average from the ages of 31 to 40). Consistent with this, having a brother also reduces women’s probability of working in STEM fields by 0.4 percentage points, corresponding to a decrease of 7.3% relative to the mean for women with a sister. Consequently, the results clearly show that having a brother induces women to exhibit more traditional choices of occupation. In other words, they are less prone to opt into traditionally male-dominated occupations, including STEM.

Raw differences: effect of having a brother on gender conformity. Main sample (first-born women born in 1962–1975 with a younger biological sibling born within 4 years). The whiskers represent the 95% confidence interval. Each bar illustrates the estimates from one regression model, only including an intercept. The point estimates are replicated in column (1) in Table 3

Sibling sex also has a significant impact on the choice of partner in terms of the degree to which his occupation is gender-typed. Having a brother rather than a sister induces women to choose a partner who works in more male-dominated occupations. On average, women with a brother have a partner working in occupations with 2.0% fewer women than women with a sister.

Table 3 shows the regression-based results, with different control versions. Column (1) replicates the raw mean differences between first-born women with a second-born sister and those with a second-born brother from Fig. 1, while column (2) includes basic demographic controls. Column (3), the preferred model, further controls for parental education. Finally, column (4) flexibly adds controls for family size and the sex of potential third- and fourth-born siblings.Footnote 21 As family size is an outcome of sibling sex composition, the latter control version might bias the estimates. However, this control version works as a robustness check of the results, as family size might also be considered a confounding variable. Regardless of the covariates included, the estimates across the different control versions are almost identical, supporting the assumption that sibling sex is random and illustrating that family size is not a principal mediator of the effect of sibling sex. The rest of this paper proceeds by presenting the results using the preferred control version in column (3).

As a test of the robustness of the main measures of gender conformity, Appendix Table 9 considers two alternative measures. Notably, having a brother also increases the partner’s relative earnings in the couple and the age between the woman and the partner. These results demonstrate a consistent effect of having a brother not only on women’s choice of gender-stereotypical occupations and partners but also on other aspects of their gender-conforming behavior.

If the effect of sibling sex at least partly is attributable to the way in which parents treat their children, we might observe some heterogeneity by parental characteristics in the effect of having a brother.Footnote 22 Panel A in Table 4 includes an interaction term between sibling sex and an indicator for having parents working (almost) equally during childhood. Remarkably, the effect of having a brother on occupational choice disappears for women coming from more gender-equal families. This suggests that women with more gender-stereotypical parents drive the effect of sibling sex on the probability of choosing more female-dominated occupations. Moreover, the results in panel B suggest that the effect of having a brother is strongest for those women with more traditional parents in terms of their educational field. The effects seem to be largest in magnitude for those with a mother who has an academic education within care or administration and for those with a father who has an academic education within STEM.

Furthermore, the effect of having a brother is largest for those with at least one highly educated parent (≥ 12 years of education) for occupational choice. In most cases, a highly educated parent will also imply having a parent with human capital that is traditionally associated with his or her own gender. For instance, most mothers with greater education are in the care and administration fields (e.g., nurse, secretary, and office work) and most fathers are in STEM fields. Therefore, these results again support the previous findings—this time, with an emphasis on parental gender-stereotypical human capital rather than gender-stereotypical labor supply.

Notably, the results also show that women whose parents both have less education do not experience an effect of sibling sex. This suggests that the effect is not due to resource constraints, which has been suggested as a potentially relevant mechanism in the sibling sex composition literature on educational attainment (Amin 2009; Butcher and Case 1994). Cools and Patacchini (2019) also observe this pattern, finding an effect of sibling sex on earnings among women with skilled, but not among those with unskilled, parents. Such finding is further consistent with Charles (2017) who shows that the gender gap in STEM aspirations is larger in more affluent countries. The heterogeneity for the other two outcomes in Table 4 is qualitatively consistent with the findings for the male share in the woman’s occupation, despite being more imprecisely estimated.

Finally, I consider heterogeneity with respect to spacing to the second-born sibling. Spacing might affect child-parent interactions and thereby the impact of sibling sex composition. A first-born daughter with long spacing was the only child for a longer time, during which the parents did not treat her differently based on their next child’s sex. Especially, influences in early childhood and the formation of child-parent interactions might be important for later family dynamics. At the same time, short spacing might increase the (accumulated) exposure to gendered parenting and gender-specific toys in the presence of a brother. Thus, longer spacing might reduce the strength of the impact of sibling sex. Expanding the sample to include women with up to 8 years before their second-born sibling and including interactions between sibling sex and spacing shows, in line with the theoretical predictions, that sibling sex does not have an impact for those with long spacing between them and their sibling (Appendix Fig. 3).Footnote 23 However, the estimated effects by spacing are not statistically significantly different from each other, probably due to the small fraction of children with long spacing between them and their second-born sibling.

In sum, these heterogeneities indicate that the effect of having a brother is strongest for women from more traditional families. In turn, this suggests that differences in child-parent interactions are important for the effects of sibling sex composition on the formation of women’s gender conformity. All other things being equal, we would expect that parents with more gender-stereotypical human capital would transmit gender norms to a stronger extent than those parents with less gender-specific human capital (Humlum et al. 2019). Additionally, we would expect that spending more time with the mother than with the father would influence the child more in the direction of the mother’s (female) rather than the father’s (male) interests. Therefore, the results are consistent with the hypothesis that parents of mixed-sex children invest more time in their same-sex child than parents of same-sex children; Section 5 elaborates more thoroughly on this.

4.1.2 Response to motherhood in labor market outcomes

To shed further light on how sibling sex impacts women’s conformity to traditional gender roles, this subsection examines whether women with a brother respond to motherhood differently than women with a sister in terms of labor supply and earnings. Using data from Denmark similar to mine, Kleven et al. (2019) document that exactly in the year of the first childbirth, female labor supply and earnings experience an immediate drop and never converge back to their initial level, while the arrival of the first child does not affect men’s labor market trajectories. Moreover, Kuziemko et al. (2018) demonstrate that upon motherhood, women in Great Britain adjust their attitudes towards gender roles substantially in a more traditional direction. Based on this evidence, the timing of the first childbirth seems to be a key trigger for women to conform to traditional gender roles. Therefore, studying women’s labor market trajectories by sibling sex before, around, and after their first childbirth might help nuance the picture of the impact of having a brother on the development of gender conformity and improve our understanding of the brother earnings penalty documented in previous work (e.g., Cools and Patacchini 2019; Peter et al.2018).

Effect of sibling sex on gender conformity in the response to motherhood. Main sample (first-born women born in 1962–1975 with a younger biological sibling born within 4 years). The whiskers represent the 95% confidence interval. Each graph illustrates the estimates from one regression model. All graphs illustrate the estimates from an event study of the effect of having a second-born brother, where the year of first childbirth is the baseline (year 0). Graphs (b) and (d) illustrate this by parental division of labor. All models absorb time-specific fixed effects and individual fixed effects. Graphs (b) and (d) further control for time-specific-“unequal parental labor division” fixed effects. Earnings Percentile measures the labor earnings percentile by age and cohort. Work Experience measures the cumulated lifetime work experience in months. a Labor Earnings. b Labor Earnings: Heterogeneity. c Work Experience. d Work Experience: Heterogeneity

Graph (a) in Fig. 2 illustrates that in the 6 years preceding the first childbirth, sibling sex does not differentially affect womens labor earnings trajectory once taking out time and individual fixed effects. Remarkably, already in the first year after entry into motherhood, women with a brother experience a larger drop in earnings by 0.33 percentiles relative to women with a sister.Footnote 24 This effect remains stable and statistically significant through 9 years after the first childbirth, i.e., through the end of the period of study. To put this into perspective, women with a younger sister experience a drop in labor earnings by 3.99 percentiles 9 years after their first childbirth, while this number is 4.41 for women with a younger brother. Thus, 9 years after the arrival of the first child, women with a younger brother experience a child earnings penalty that is 10.53% larger than women with a younger sister.

Next, graph (b) explores heterogeneity in the effect of having a brother by childhood family background. For this, I split the effect of sibling sex by parental division of labor during the women’s childhood. Thus, I present the estimates of the effect of having a brother for women of parents working (almost) equally during childhood (referred to as equal in the graphs) and the effect of having a brother for women of fathers working (much) more than mothers (unequal). The negative effect of having a brother on women’s earnings trajectory upon entry into motherhood is entirely driven by women from more traditional families: these women experience a drop in earnings that is 0.5 to 0.7 percentile points larger in the 9 years following their first childbirth compared to the rest of the sample.

Before entering into motherhood, sibling sex does not differentially affect women’s labor supply, measured through their cumulated full-time equivalent work experience (graph (c)). Meanwhile, after the arrival of the first child, a difference by sibling sex emerges. Nine years after entry into motherhood, women with a brother have cumulated 0.54 fewer months of work experience. Again, this difference by sibling sex is solely driven by women from more traditional families: women with a brother from more gender-stereotypical families have cumulated nearly 1 month less of work experience 9 years after the birth of their first child compared to women with a sister (graph (d)). Put differently, women with a brother from more gender-equal families do not experience a differential labor market trajectory upon entry into motherhood relative to the one of women with a sister.

Previous studies on sibling sex composition have documented negative effects of having a brother on women’s earnings (Cools and Patacchini 2019; Gielen et al. 2016; Peter et al. 2018). They have, however, done so without relating the time of measurement to the entry into motherhood and mostly without considering potentially dynamic effects over time. Appendix Fig. 4 illustrates the impact of having a brother on women’s labor market outcomes from an event study, including individual fixed effects, examining whether women experience different labor market trajectories by sibling sex between ages 18 and 40.Footnote 25 This shows that for the overall sample (not restricted to women with at least one child) a negative and statistically significant effect of having a brother on earnings emerges from age 28 and persists through age 40—an effect that is again completely driven by women from traditional families. To relate these results to the ones on the differential response to motherhood, Appendix Fig. 5 displays the cumulative distribution of age at first childbirth. By age 28, 55% of women have had their first child which help explain the timing of the emerging brother earnings penalty.

To compare the magnitude of these results with other studies, Appendix Fig. 4 demonstrates that the negative effect of having a brother on log-earnings in women’s thirties corresponds to a decrease of approximately 2%. Consistent with my results, Peter et al. (2018) find a negative effect of having a brother on a proxy for women’s permanent income in the magnitude of nearly 1% in Sweden. Similarly, Cools and Patacchini (2019) show that first-born women in the USA earn 9% less around age 30 when having a second-born brother instead of a sister.Footnote 26 These similar findings of a negative impact of having a brother on women’s earnings across three different developed countries suggest that my findings on gender conformity might be generalizable to a broader set of countries. At the same time, the differences in magnitudes also suggest that the effects on gender conformity might be larger in more gender unequal societies.Footnote 27 Thus, although the brother earnings penalty is only 2% in my empirical setting, its economic significance seems to be substantial in more gender unequal settings.

4.2 Education and family formation

Could differences in ability or fertility behavior explain the impact of having a brother on women’s increased conformity to traditional gender roles in terms of occupational and partner choice? In short, the answer is no. I do not find any evidence of an impact of sibling sex on educational attainment or school performance (columns (2) and (3) in panel A, Table 5).Footnote 28 This is similar to Peter et al. (2018), which is the only existing study with causal estimates of sibling sex on educational attainment. Likewise, Cyron et al. (2017) do not find an effect of sibling sex on girls’ cognitive or non-cognitive skills in first grade in the United States. Thus, sibling sex does not seem to affect differences in ability or (financial constraints in terms of) access to education. This supports an interpretation that the channels of the effect of sibling sex on occupational choice are changes in interests or identity.

While sibling sex does not affect overall educational attainment, the effect of sibling sex on occupational choice is closely mirrored in field of education by age 30. Having a brother reduces the share of men in the highest completed field-by-level of education by 1.35%. Similarly, women with a brother relative to those with a sister are respectively 7.4 and 11.0% less likely to ever enroll in and complete any field-specific STEM education. Appendix Table 10 further shows that the effect is already present in the type of first educational enrollment after compulsory education and that the effect is present for STEM degree completion at different levels of education. Thus, having a brother pushes women out of traditionally male-dominated fields as early as age 16.

The magnitude of the effects is comparable with previous studies examining the impact of various aspects of the social environment in school on study choice (Bottia et al. 2015; Carrell et al. 2010; Schneeweis and Zweimüller 2012; Fischer 2017). Moreover, the results are broadly comparable with other studies examining correlations between sibling sex composition and field of college major (Anelli and Peri 2015; Oguzoglu and Ozbeklik 2016). Appendix Table B13 in Brenøe (2021) displays the associations between the sex of a first-born sibling and second-born women’s gender conformity, indicating similar but less robust correlations compared with the main results. These results are also closer to those in Anelli and Peri (2015), who do not find a significant association for women’s enrollment in high-earning college majors (although the magnitude of their estimate is relatively large). This stresses the importance of rigorously considering selection bias when the aim is to evaluate the causal effect of sibling sex.

A potential reason for the differences in educational and occupational choice by sibling sex could be differences in family formation preferences. Women with a stronger desire to have children early or more children might plan their choice of occupation accordingly, as female-dominated occupations tend to be more family-friendly (Goldin 2014; Kleven et al. 2019). If that were the case, we would expect women with a brother to wish to marry earlier, have children earlier, or have more children than women with a sister.Footnote 29 The administrative data do not report women’s family preferences, but it rigorously documents their actual behavior. Overall, I do not find support of any meaningful impact of sibling sex on the various aspects of family formation reported in panel B in Table 5. The results only suggest a small negative effect of having a brother on cohabitation,Footnote 30 while sibling sex has no effect on the probability of being married (column (2)). Thus, the only difference between women with a brother and those with a sister is that the former move in with a partner before marriage slightly later. This might explain the small positive (though negligible) effect on age at first childbirth.Footnote 31 Overall, sibling sex has no effect on the fertility rate through age 41, i.e., close to complete realized fertility.

4.3 Persistent effects to the next generation (of girls)

So far, I have documented that the childhood family environment affects the development of women’s gender conformity. Having a brother influences the family environment to such a degree that women choose more female-dominated occupations and more gender-conforming partners. This motivates the final question—before turning to the study of potential mechanisms—whether the effect on gender conformity (and thereby these women’s adult family environment) is sufficiently strong to affect the next generation. To investigate this, I examine the school performance in Grade 9 in language and math respectively of these women’s first-born daughters and sons separately. In other words, I here focus on school performance in subjects that are associated with traditionally “female” (language) versus “male” (math) skills. In line with the typical finding that boys seem less sensitive to the social environment than girls in terms of “gendered” outcomes (Bottia et al. 2015; Carrell et al. 2010; Fischer 2017), we might expect largest impacts on daughters’ performance relative to the one of sons.

A potential effect of sibling sex on the next generation’s school performance might either go through a direct transmission of gender norms from parents to children or through the type of parents’ human capital. On the one hand, more traditional (gender-conforming) parents might impose more gender-stereotypical expectations on their children than less traditional parents. For instance, traditional parents might not have high expectations for their daughters’ math performance but, in contrast, expect their sons to perform well in math.

On the other hand, parents might have similar expectations but different possibilities to help their children with homework. As mothers are more likely to help children with homework than fathers,Footnote 32 maternal skills might be particularly relevant for this channel. Girls with a more gender-conforming mother might receive more help with language homework and, for instance, be more encouraged to read books for leisure than girls with a less gender-conforming mother. As previously shown (Table 5 and Appendix Table 10), the sex of the mother’s sibling does not affect her own school performance in compulsory education or in overall high school GPA. Yet, sibling sex affects her field of post-compulsory education, changing her competences within certain skill domains. Therefore, girls with a more gender-conforming mother might also receive less(more) qualified help with or be less (more) encouraged to do their math (language) homework. Note, however, that the gender gap in math performance (0.10 SD) is not as large as in language (0.45 SD), suggesting that most of any potential action might happen in the “female” domain of skill acquisition.Footnote 33 Consequently, if having a more gender-stereotypical mother (and father) affects the next generation, we would expect daughters to perform better in languages and/or worse in math.

Remarkably, Table 6 shows that daughters whose mother’s second-born sibling is male relative to female perform 2.44% of a standard deviation better in languages. Meanwhile, I do not detect an effect on daughters’ math performance nor on sons’ performance in either discipline. Thus, daughters’ differences in language and math ability are larger for those with a more gender-conforming mother.Footnote 34 This increase in girls’ absolute advantage in language over math might in turn predict more traditional choices of field of education. Notably, I find evidence of very persistent long-run consequences of women’s childhood family environment. A likely explanation for this finding is the change in daughters’ childhood family environment in terms of the parental skill sets and gender role attitudes, an aspect of the maternal family environment that was unaffected by her sibling’s sex.

5 Gender-specific parenting as a relevant mechanism

5.1 Related literature

The previous section documents that sibling sex affects women’s development of conformity to traditional gender norms and that the impact seems to be strongest among women from more gender-stereotypical families. This subsection discusses relevant mechanisms behind these findings, while the subsequent subsection provides some empirical evidence. Overall, I consider changes in identity to be the main channel of the impacts on gender conformity, as the previous analysis does not suggest that differences in educational attainment, ability, labor force participation before motherhood, family size, or resource constraints are important or driving mechanisms. Consistent with the same-sex education literature (Booth et al. 2014; Schneeweis and Zweimüller 2012), the overarching argument is that girls with a brother are more exposed to gender-stereotypical behavior in the family, and therefore they are more inclined to acquire traditional gender norms. In this context, gender-stereotypical behavior could become more salient through changes in the nature of either child-sibling and/or child-parent interactions.

First, parents might interact differently with their children depending on the sex composition in terms of the quantity, quality, and content of time spent together. Assuming that both parents spend at least some time with their children, a traditional household specialization model suggests that parents gender-specialize their investment in children when they have mixed-sex children if mothers have the comparative advantage of creating female human capital and fathers are more productive in creating male human capital (Becker 1973). Parents might also derive more utility from spending time with a same- compared to an opposite-sex child due to the type of activities undertaken with the child. In both cases, it would be optimal for parents of mixed-sex children to gender-specialize their parenting investments to a greater extent than those of same-sex children.

McHale et al. (2003) suggest that because parents of mixed-sex children have the opportunity to gender-differentiate their parenting, children with opposite sex siblings might have the strongest explicit gender stereotypes. Endendijk et al. (2013) find some evidence that fathers with mixed-sex children exhibit stronger gender-stereotypical attitudes than those with same-sex children. Previous research has further documented that overall mothers talk more in general and more about interests and attitudes with daughters than sons (Maccoby 1990; Leaper et al. 1998; Noller and Callan 1990). By contrast, fathers talk more and spend more time with sons than daughters and have a greater emotional attachment to sons (Bonke and Esping-Andersen 2009; Morgan et al. 1988; Noller and Callan 1990). Based on this, we might expect that parents of mixed-sex children gender-specialize their parenting more and thereby expose their children more to gender-stereotypical behavior than parents of same-sex children. This in turn might result in a stronger transmission of gender norms in families with mixed-sex children.

Second, first-born girls might interact differently with their second-born sibling depending on the siblings’ sex. In particular, having a brother might make girls more aware of “appropriate” female behavior or more likely to want to differentiate themselves from their sibling and thereby induce them to develop more gender-stereotypical behaviors and attitudes. For instance, Booth and Nolen (2012) show that girls attending same-sex schools are no more risk averse than boys, while girls attending mixed-sex schools are significantly more risk averse. Women are generally less competitive than men and this sex difference in competitiveness seems to be stronger in mixed-sex relative to same-sex environments (Bertrand 2011; Niederle and Vesterlund 2011). Traditionally male-dominated (STEM) fields are considered more competitive (Buser et al. 2014). Therefore, having a brother instead of a sister might change women’s degree of competitiveness and thereby their preferences for working in competitive environments. For that reason, having a brother might induce women to develop more gender-stereotypical attitudes due to a greater awareness of gender through sibling interactions. This in turn could be reinforced by parents’ increased gender specialization. For instance, Rao and Chatterjee (2018) find that women with a larger share of brothers tend to hold more traditional family attitudes.Footnote 35

Thus, differences in child-parent interactions and in particular increased gender specialization in families with mixed-sex children are a potentially key mechanism for the observed effect of sibling sex on women’s formation of gender norms, which I am able to empirically test. In the remainder of this section, I explore this mechanism by investigating the impact of sibling sex composition on parental time investment. More precisely, in daily child-parent interactions, we might observe that parents of mixed-sex children invest more quality time in their same-sex child. This could explain the heterogeneity in the effect of sibling sex documented in Table 4. Furthermore, in the case of parental divorce, we might expect that children from mixed-sex child families would be more likely to live with their same-sex parent compared to same-sex children due to a stronger degree of gender-specialized parenting. Consequently, it is common for these predictions that a parent of mixed-sex children influences his or her same-sex child more than a parent of same-sex children.

5.2 Empirical evidence on gender-specific parenting

To investigate whether sibling sex composition affects child-parent interactions, I draw on the Danish Longitudinal Survey of Children (DALSC), which I have linked to administrative data.Footnote 36 The survey has followed children born between September and October 1995 to a mother with Danish citizenship from the age of 6 months throughout childhood. It is a unique survey due to its detailed information on parental time investment. For this analysis, I select first-born girls who have a second-born sibling born within 5 years.Footnote 37 Appendix Table 11 presents descriptive statistics on predetermined parental characteristics and balancing checks. Parental characteristics balance across sibling sex composition. Moreover, as expected given the difference in birth years between the main and the DALSC samples, parents in the DALSC sample are on average better educated and older at their child’s birth.

At the ages of 7 and 11, both parents report how often they undertake different types of activities together with their first-born daughter. I construct an index on parental quality time investment, using principal component analysis, and standardize it with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1.Footnote 38 I define quality time as playing with the child, helping with homework, doing out-of-school activities, reading/singing, and going on an excursion.

Columns (1) to (4) in Table 7 provide the results on parental time investment by each parent for the two ages, separately. Mothers of a first-born daughter and a second-born son invest 15% of a standard deviation more time in their first-born daughter at both ages compared to mothers with two daughters. By contrast, fathers invest 21–24% of a standard deviation less time in their first-born daughter when having mixed-sex children. This reduction in total paternal time investment is driven by reduced time spent playing, helping with homework, and reading for the daughter (Appendix Table 12).Footnote 39 This finding indicates that, in mixed-sex families, the parent who is less-qualified in and less-excited about traditionally male-dominated subjects (the mother) helps the daughter more with homework in these subjects. This might prevent girls with a brother from growing interests in these fields. Furthermore, this effect on father-daughter interactions translates into a substantially worse relationship between fathers and their first-born daughters when the second-born child is male relative to female (Appendix Table 13). Overall, girls receive the same time investment regardless of their younger sibling’s sex, as mothers in absolute terms tend to spend more time with their daughter than fathers. These results clearly show that first-born girls with a second-born brother experience more gendered parenting relative to those with a younger sister.

Ideally, I would have had similarly detailed data on parental inputs for the main sample. However, such information is not observed in the administrative registries. Instead, I observe all children’s family structure at age 17.Footnote 40 Sibling sex composition does not alter the probability of living with both biological parents (column (5) in Table 7). In the case of parental divorce or separation (henceforth divorce), the living arrangement between parents and children in the main sample might additionally shed light on child-parent interactions in terms of splitting parents’ time. If parents of mixed-sex children gender-specialize more than those of same-sex children, we would expect that divorced families with mixed-sex children would be more likely than families with same-sex children to have a living arrangement in which the first-born daughter lives with her mother and the second-born child lives with the father.

Conditional on living in a divorced family, the results show a pattern consistent with the prediction (column (6)). First-born daughters with a second-born brother are 5.30 percentage points (115%) more likely to live with their mother while their younger sibling lives with the father. These results consequently show a strong effect on the living arrangement among divorced families, thereby lending support to the previous findings (based on the much smaller DALSC sample) on more gender-specific parenting and time investment in families with mixed-sex children. In conclusion, these findings support the hypothesis that parents of mixed-sex children gender-specialize their parenting more than those of same-sex children, thereby strengthening the transmission of traditional gender-specific interests and behaviors.

6 Conclusion

This study documents that the childhood family environment has a long-run impact on women’s occupational and marital choice, with persistent effects to the next generation of girls. The results show that having a second-born brother relative to a sister increases first-born women’s gender conformity, as measured through the gender composition in their own occupation and the one of their partner. I further show that having a brother negatively affects labor supply and earnings upon entry into motherhood and that this pattern is entirely driven by women growing up in more gender-stereotypical families. I provide compelling evidence that changes in child-parent interactions—and in particular increased gender-specialized parenting in families with mixed-sex children—play an important role for the changes in gender conformity. This suggests that the transmission of traditional gender norms is stronger in families with mixed-sex children. Finally, I show that the increased gender conformity among women with a brother persists into the next generation of girls, as indicated by an increase in daughters’ comparative advantage in language over math performance in school.

Put differently, until the birth of the younger sibling, these girls and their parents were similar. Yet, the random event of the arrival of a brother to the family instead of a sister affects these girls’ socialization process within the family. These changes have long-lasting consequences for women’s career path and the family environment they give their children. However, this event alone cannot explain the gender gap in labor market outcomes, as the aggregate effect of having a brother is only small compared to the extent of gender segregation in the labor market and the gender pay gap. But this event stresses that exposure to gender-stereotypical behavior in the family environment shapes women’s interests, choices, and behaviors. This clearly highlights that biological differences between men and women cannot be the single driver of gender differences in outcomes.

Importantly, having a brother already affects girls’ study choices in a more gender-stereotypical direction at the end of compulsory schooling. This indicates that girls’ development of gender conformity by adolescence has important consequences for their later-life educational and labor market outcomes. Thus, if policy makers wish to reduce gender inequality in the labor market, one relevant margin to focus on is the formation of conformity to gender norms among school girls and not only at the time of their career choice.

Notes

In this paper, I define gender norms as people’s perceptions of how women and men generally should conform within society, based on the definition by United Nations Statistics Division (2018). Gender roles reflect the expectations associated with the perception of masculinity and femininity; I refer to gender norms and gender roles interchangeably. Similarly, I consider gender conformity as the act of conforming to the prevailing gender norms in society. While gender norms within a given society are relatively fixed at a given point in time, the degree to which individuals conform to those norms differ.

I measure a traditional family as having a father working more than the mother during childhood.

Starting from Butcher and Case (1994), a small literature on sibling sex composition has predominantly concerned educational attainment with overall mixed results (Amin 2009; Bauer and Gang 2001; Conley 2000; Hauser and Kuo 1998; Kaestner 1997). However, small sample sizes (in most cases around 3,000–4,000 observations) pose a general problem, often resulting in quite imprecise estimates, and these studies include all siblings in the measure of sibling sex composition, raising concerns about potential biases.

Rao and Chatterjee (2018) consider earnings at age 28–36 for cohorts born two decades earlier also in the USA but fail to find a significant correlation between the share of brothers and women’s wages.

However, Peter et al. (2018) do not observe earnings for all ages for any of the cohorts.

These effects seem to be negligible, however, as the probability of ever marrying and having any children is only reduced by 0.7 and 0.2% relative to the mean, respectively. They suggest that this effect on family formation might be due to competition among sisters, as older sisters normally want to get married and have children before their younger siblings and women typically start their family formation earlier than men.

Only few papers on sibling sex composition have considered occupational choice and have generally not had access to data that could allow for any clear-cut conclusion. Cools and Patacchini (2019) and Rao and Chatterjee (2018) consider some indicators for occupational outcomes based on self-reported measures; however, their estimates are too noisy to allow for any clear conclusions due to small sample sizes (N < 2900). Moreover, Peter et al. (2018) consider the female share in women’s occupation, but have access to fewer years of data than I do and pool women of very different ages and birth cohorts; overall, they do not find an effect of sibling sex, though they note that they qualitatively find a comparable effect to my results on the probability of working in a STEM field. Moreover, to the best of my knowledge, no previous sibling sex composition paper has examined the gender conformity of the choice of women’s partner.

While the main analysis concerns the development of women’s gender norms, Appendix B.5 of the working paper version of this paper (Brenøe 2021) briefly presents the results from a similar analysis for men. In line with the findings for women, the results suggest that having an opposite-sex sibling enhances men’s gender conformity.

My strategy is, e.g., in contrast to Amin (2009), Anelli and Peri (2015), Bauer and Gang (2001), Butcher and Case (1994), Conley (2000), Cyron et al. (2017), Hauser and Kuo (1998), Kaestner (1997), Oguzoglu and Ozbeklik (2016), and Rao and Chatterjee (2018), as they generally include children of different birth orders and consider the correlational effect of the number of sisters (or brothers) or of having any sister (or brother). Moreover, Gielen et al. (2016) employ a difference-in-differences strategy to estimate the effect of having a male twin on earnings, although their interest lies in whether exposure to prenatal testosterone (rather than sibling sex composition per se) has an effect on earnings. Contemporaneous with this current paper, Peter et al. (2018) developed a similar strategy to mine (in their working paper version, they only considered the effect of a co-twin’s sex (Peter et al. 2015), an approach similar to Cronqvist et al. 2016). Relatedly, Cools and Patacchini (2019) consider the effect of the sex of a next younger sibling, an approach that Rao and Chatterjee (2018) also consider in a robustness check and that Vogl (2013) also use in the context of marriage institutions in developing countries (though, in the rest of the paper, I will only consider studies from developed countries). Moreover, Healy and Malhotra (2013) use the sex of a next younger sibling as an instrument for the share of sisters within a sibship to examine the effect on political attitudes.

If the parent does not have a field-specific education, I use their field of occupation.

For first-generation immigrants, I do not necessarily have complete sibling or parental information. Second-generation immigrants would have represented approximately 1% of the sample; I decided to exclude them to have a more homogeneous sample. However, including second-generation immigrants does not change the results.

Of all children who fulfill all sample requirements except for the restriction on spacing, 72% have less than 4 years between them and their second-born sibling.

Sibling sex composition does not affect attrition due to these restrictions.

I observe parents’ labor supply through a mandated pension scheme (ATP), in which employers contribute for each employee based on the number of hours worked. This is also the variable I use to measure cumulative work experience as the outcome variable; see, e.g., Kleven et al. (2019) for more details on this measure.

In Brenøe (2021), the graphs in Appendix Figure B.2 illustrate the estimates from an event study of the effect of having a second-born son on a variety of parental socio-economic characteristics. The sex composition of children does not affect parental cohabitation, marital status, length of education, employment, or labor earnings around the birth of their first child.

I use the Danish version of the International Standard Classification of Occupations (DISCO), which I observe from 1991 to 2013. This implies that I only observe the occupation through age 38 (39) for the 1975(1974) cohort.

I define the partner as the mode person with whom the woman cohabits or is married between the ages of 31 and 41. I consider the logarithm of the male share in the woman’s own occupation and the logarithm of the female share in her partner’s occupation because these measures best approximate a normal distribution rather than considering the logarithm of the male share in both persons’ occupations. As an anonymous referee pointed out, I acknowledge that this measure of the woman’s choice of partner also to some degree could reflect her preference for marital complementarity, while still reflecting gender conformity, as women working in more traditionally female occupations tend to partner with men working in more traditionally male occupations.

For the event study estimations of labor market outcomes, I restrict the sample to women who live outside Denmark (and thus do not have an observation during those years) for at most 3 years of the analysis period.

Kleven et al. (2019) show that the response to motherhood is much larger at the intensive compared to the extensive labor supply margin in Scandinavia and German-speaking countries than in English-speaking countries.

Given that child sex is independent of the sex of the mother’s sibling, this split does not create any bias. Nonetheless, sibling sex might affect the mother’s gender preference for her own children and thereby her subsequent fertility choices. Therefore, I only consider women’s first-born children. Sibling sex is unrelated to the probability of having an observation on a first-born child’s outcomes.

The estimates are identical when not controlling for third- and fourth-born siblings’ sex.

As seen in Table 1, these parental characteristics do not differ by sibling sex composition.

Ninety-seven % of all second-born full siblings are born within 8 years after the first child. Therefore, the sample for children with longer spacing is too small to meaningfully study heterogeneity by longer spacing.

Appendix Figure A2 in Brenøe (2021) illustrates that these findings are robust with alternative earnings measures (raw earnings and the natural logarithm of earnings) and that women’s unemployment trajectory is unaffected by sibling sex in relation to the timing of childbirth.

At age 18, there is no difference in the labor market outcomes by sibling sex.

Rao and Chatterjee (2018) do not find a significant correlation between sibling sex composition and women’s earnings among slightly older cohorts in the USA, although their estimate of the effect of having a next-younger male sibling indicates a negative impact.

In 2017, Sweden ranked as the fifth-most gender-equal country, Denmark ranked number 14, and the USA ranked number 49 according to the Global Gender Gap Index (World Economic Forum 2017).

Appendix Table 10 further shows that there is no effect on different types of ability, measured through Grade 9 language and math written exam GPA. Moreover, Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests cannot reject equality of distributional functions for neither of the three GPA measures. Thus, distributional effects do not seem to be important.

However, such a conjecture implicitly requires that being married and having children is an important aspect of women’s gender identity. This might very well not be the case in a modern setting in which women do not face a mutually exclusive choice of having a family and a career (Bertrand et al. 2020; Goldin and Katz 2002). For instance, the cohorts of women under study have all had access to contraceptives, abortion, various family leave policies, and infant- and childcare options. On the other hand, women with a younger sister might experience more competition in terms of being the first among the two who marries and has children, as men (i.e., brothers) on average are older when they start their family formation. These two opposing forces might explain why I essentially do not find any effect of sibling sex on various aspects of family formation, consistent with the findings in Peter et al. (2018).

This could be due to more traditional gender norms, as more traditional women might want to wait longer before moving in with a partner before marriage. The majority of these cohorts cohabit and have children before marriage. Ninety-one % of the women in the sample have cohabited for at least one year before the year they get married, and 53% get married in the year of their first childbirth or later.

In the main sample (used for the analysis of the response to motherhood), Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests of age at first birth cannot reject equality of distributional functions by sibling sex (p = 0.354; p = 0.785), by sibling sex among those with parents working equal (p = 0.242; p = 0.947) or unequal (p = 0.706; p = 0.627).

In the DALSC sample (see Section 5.2), mothers, on average, help daughters with homework 4.2 times a week at age 7 and 3.1 times a week at age 11 in contrast to fathers who help 1.7 times a week at both ages. For a comparable sample of sons, mothers help sons with homework 3.5 times a week both at age 7 and 11, while fathers help sons 1.6 times a week at age 7 and 1.7 times at age 11.

This could be because the degree to which math is considered masculine is smaller than the femininity of language in primary school or simply because most math learning takes place in school, while a larger degree of language learning is acquired outside school, e.g., through practicing reading skills.

This difference is statistically significant (insignificant) for daughters (sons) with an estimate of 2.22 (0.05) and standard error of 0.95 (0.98).

For one out of four gender role attitudes questions, Healy and Malhotra (2013) reach a similar finding.

The study was designed by researchers from SFI, the Danish National Centre for Social Research, in collaboration with other research institutions. The survey includes 6011 randomly sampled children and their parents and was conducted in 1996, 1999, 2003, 2007, 2011, and 2015.

I allow for spacing within 5 years (and not 4 years as in the main sample) to increase the sample size and thereby, power.

See Appendix Table B10 in Brenøe (2021) for details.

Unfortunately, data from time diaries is not available in the survey. Cools and Patacchini (2019) also consider a 5-point scale index of activities with the mother and father separately during adolescence. However, their index is only a crude measure of high-frequency, high-quality activities with the child. They also find that mothers spend more time with their daughter when the next-youngest child is male, while they do not find an effect on father’s activities.

I observe the family structure on January 1 each year and use the observation for the year when the person turns 18 or the last year in which the child lived with at least one biological parent.

References

Akerlof G A, Kranton R E (2000) Economics and identity. Q J Econ CXV:715–753

Amin V (2009) Sibling sex composition and educational outcomes: a review of theory and evidence for the UK. Labour 23(1):67–96

Anelli M, Peri G (2015) Gender of siblings and choice of college major. CESifo Econ Stud 61(1):53–71

Angrist JD, Evans WN (1998) Children and their parents’ labor supply: evidence from exogenous variation in family size. Am Econ Rev 88(3):450

Angrist J, Lavy V, Schlosser A (2010) Multiple experiments for the causal link between the quantity and quality of children. J Labor Econ 28 (4):773–824

Bauer T, Gang I (2001) Sibling rivalry in educational attainment: the German case. Labour 15(2):237–255

Becker GS (1973) A theory of marriage: part I. J Polit Econ 81 (4):813–846

Becker GS, Tomes N (1986) Human capital and the rise and fall of families. J Labor Econ 4(3, Part 2):S1–S39

Bertrand M (2011) New perspectives on gender. Handbook of Labor Economics 4:1543–1590

Bertrand M, Cortés P, Olivetti C, Pan J (2020) Social norms, labor market opportunities, and the marriage gap between skilled and unskilled women. Rev Econ Stud, forthcoming

Black SE, Devereux PJ, Salvanes KG (2005) The more the merrier? The effect of family size and birth order on children’s education. Q J Econ 120(2):669–700

Blau FD, Kahn LM (2017) The gender wage gap: extent, trends, and explanations. J Econ Lit 55(3):789–865

Bonke J, Esping-Andersen G (2009) Parental investments in children: how educational homogamy and bargaining affect time allocation. Eur Sociol Rev 10(20):1–13

Booth AL, Nolen P (2012) Gender differences in risk behaviour: does nurture matter? Econ J 122(558):F56–F78

Booth A, Cardona-Sosa L, Nolen P (2014) Gender differences in risk aversion: do single-sex environments affect their development? J Econ Behav Org 99:126–154

Bottia MC, Stearns E, Mickelson RA, Moller S, Valentino L (2015) Growing the roots of STEM majors: female math and science high school faculty and the participation of students in STEM. Econ Educ Rev 45:14–27

Brenøe AA (2021) Brothers increase women’s gender conformity. University of Zurich, Department of Economics, Working Paper

Buser T, Niederle M, Oosterbeek H (2014) Gender, competitiveness, and career choices. Q J Econ 129(3):1409–1447

Butcher KF, Case A (1994) The effect of sibling sex composition on women’s education and earnings. Q J Econ 109(3):531–563

Carrell SE, Page ME, West JE (2010) Sex and science: how professor gender perpetuates the gender gap. Q J Econ 125(3):1101–1144

Charles M (2017) Venus, Mars, and Math: gender, societal affluence, and eighth graders’ aspirations for STEM. Socius 3:2378023117697179

Conley D (2000) Sibship sex composition: effects on educational attainment. Social Sci Res 29(3):441–457

Cools A, Patacchini E (2019) The brother earnings penalty. Labour Econ 58:37–51

Cronqvist H, Previtero A, Siegel S, White RE (2016) The fetal origins hypothesis in finance: prenatal environment, the gender gap, and investor behavior. Rev Financ Stud 29(3):739–786

Cyron L, Schwerdt G, Viarengo M (2017) The effect of opposite sex siblings on cognitive and noncognitive skills in early childhood. Appl Econ Lett 24(19):1369–1373

Endendijk JJ, Groeneveld MG, van Berkel SR, Hallers-Haalboom ET, Mesman J, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ (2013) Gender stereotypes in the family context: mothers, fathers, and siblings. Sex Roles 68(9–10):577–590

Fischer S (2017) The downside of good peers: how classroom composition differentially affects men’s and women’s STEM persistence. Labour Econ 46:211–226

Gielen AC, Holmes J, Myers C (2016) Prenatal testosterone and the earnings of men and women. J Hum Resour 51(1):30–61

Goldin C (2014) A grand gender convergence: its last chapter. Am Econ Rev 104(4):1091–1119

Goldin C, Katz LF (2002) The power of the pill: oral contraceptives and women’s career and marriage decisions. J Polit Econ 110(4):730–770

Hauser RM, Kuo H-HD (1998) Does the gender composition of sibships affect women’s educational attainment? J Hum Resour 33(3):644–657

Healy A, Malhotra N (2013) Childhood socialization and political attitudes: evidence from a natural experiment. J Polit 75(4):1023–1037

Humlum MK, Nandrup AB, Smith N (2019) Closing or reproducing the gender gap? Parental transmission, social norms and education choice. J Popul Econ 32(2):455–500

Kaestner R (1997) Are brothers really better? Sibling sex composition and educational achievement revisited. J Hum Resour 32(2):250–284

Kleven H, Landais C, Søgaard JE (2019) Children and gender inequality: evidence from Denmark. Am Econ J: Appl Econ 11(4):181–209

Kleven H, Landais C, Posch J, Steinhauer A, Zweimüller J (2019) Child penalties across countries: evidence and explanations. AEA Pap Proc 109:122–26

Kuziemko I, Pan J, Shen J, Washington E (2018) The mommy effect: do women anticipate the employment effects of motherhood?

Leaper C, Anderson K J, Sanders P (1998) Moderators of gender effects on parents’ talk to their children: a meta-analysis. Dev Psychol 34(1):3–27

Maccoby E E (1990) Gender and relationships. A developmental account. Am Psychol 45(4):513–520

McHale S M, Crouter A C, Whiteman S D (2003) The family contexts of gender development in childhood and adolescence. Social Dev 12 (1):125–148

Morgan S P, Lye D N, Condran G A (1988) Sons, daughters, and the risk of marital disruption. Am J Sociol 94(1):110–129

Niederle M, Vesterlund L (2011) Gender and competition. Annu Rev Econ 3(1):601–630

Noller P, Callan V J (1990) Adolescents’ perceptions of the nature of their communication with parents. J Youth Adolesc 19(4):349–362

OECD (2016) Education at a glance 2016: OECD indicators

OECD (2017) OECD Labour Force Statistics 2017

Oguzoglu U, Ozbeklik S (2016) Like father, like daughter (unless there is a son): sibling sex composition and women’s stem major choice in college. Institute of Labor Economics (IZA), No. 10052

Peter N, Lundborg P, Webbink D (2015) The effect of sibling’s gender on earnings, education and family formation. Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper, TI 2015-073/V

Peter N, Lundborg P, Mikkelsen S, Webbink D (2018) The effect of a sibling’s gender on earnings and family formation. Labour Econ 54:61–78

Rao N, Chatterjee T (2018) Sibling gender and wage differences. Appl Econ 50(15):1725–1745

Schneeweis N, Zweimüller M (2012) Girls, girls, girls: gender composition and female school choice. Econ Educ Rev 31(4):482–500

United Nations Statistics Division (2018) United Nations Statistics Division: Gender Statistics Manual

Vogl T S (2013) Marriage institutions and sibling competition: evidence from South Asia. Q J Econ 128(3):1017–1072

World Economic Forum (2017) The global gender gap report: 2017, World Economic Forum, Geneva. OCLC: 1012177619

Acknowledgements