Abstract

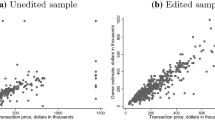

We focus on the housing market and examine why nonlocal home buyers pay 12% more for houses than local home buyers. We established a database on the residential housing market for Lafayette and West Lafayette, Indiana, that includes house transactions from 2000 to 2020. The dataset contains highly detailed information on individual buyers and house characteristics. We explain the price differential controlling for arguments such as imperfect information on prices, wealth effects, heterogeneous buyer preferences, and differential search and travel costs across buyers, among others. We estimate a housing demand model that returns heterogeneous marginal willingness to pay parameters for housing attributes. Our results show that nonlocal home buyers are willing to pay more for specific housing attributes, especially for house size, school quality, and house age. We also find that arguments such as gratification, reward, and imperfect price information explain the price differential to a large extent. Search and travel cost arguments have an adverse effect on nonlocal buyers’ house spending.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For example, a house in Beverly Hills, California, is valued and priced differently than a comparable house in Indiana.

We use this information from various sources, such as the Multiple Listing Services, the county assessor, and mortgage documents.

We use the approach by Bishop and Timmins (2019) and we would also like to thank Kelly Bishop for providing valuable insights.

Local buyers pay an estimated average of \(\mathrm{\$}187,524\) for houses, while NLBs pay \(\mathrm{\$}210,070\).

Due to data limitations, our study is not able to include the effect of agencies on house prices. This is certainly an interesting and important topic that will be discussed further at the end of the paper.

For further information on search frictions arising from deadlines, see Coey et al. (2019).

For information on the evolution of housing prices and appreciation rates in different states, see the U.S. Census Bureau at http://www.census.gov/const/www/quarterly starts completions.pdf and OFHEO at http://www.ofheo.gov/media/hpi/2q07hpi.pdf. All monetary values in this study are expressed in 2020 U.S. dollars using the Consumer Price Index.

In comparing our database with the Census of Population and Housing database, the latter database contains self-reported or estimated home values, which are less reliable than the house prices in our database. Moreover, the prices are partitioned into 23 mutually exclusive categories, and this represents a loss of information compared to our pricing data.

The identities and some other information about the home buyers are kept anonymous in the study.

Most apartments in Lafayette and West Lafayette are rental properties, so we would not expect any crucial concerns from removing these.

This includes most of the variables that have been provided to us.

We dropped house purchases by non-U.S. residents.

We would like to thank a referee for the suggestion to separately control for education effects of nonlocal home buyers that purchase a home in West Lafayette. This separation allows us to test whether nonlocal buyers that work in academia (as captured by the dummy \(WLNLB\)) are willing to spend a premium on school quality and the education for their children.

We thank a referee for the suggestion to adopt this preliminary regression.

We would like to thank an anonymous referee for valuable feedback on this section. We also thank Kelly Bishop for providing support on the estimation algorithm.

For notational simplicity, we suppress time subscripts.

The \({i}^{*}\) indicates that the \(\beta\) coefficients hold locally for each household-level observation in \(Z\).

It should be noted that the estimated coefficients reflect the implicit prices averaged across all buyers. We turn to the estimation of individual-specific marginal willingness to pay parameters in the second stage of our estimation procedure.

Remember that this prediction is evaluated at the average implicit price.

References

Anand, A., & Subrahmanyam, A. (2008). Information and the intermediary: Are market intermediaries informed traders in electronic markets? Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 43(1), 1–28

Andrews, D. W. K. (1991). Asymptotic normality of series estimators for nonparametric and semiparametric regression models. Econometrica, 59(2), 307–346

Bartik, T. J. (1987). The estimation of demand parameters in hedonic price models. Journal of Political Economy, 95(1), 81–88

Baye, M., Morgan J., & Scholten, P. (2006). Information, search, and price dispersion. in Handbook of Economics and Information Systems, Amsterdam.

Bayer, P., Ferreira, F., & McMillan, R. (2007). A unified framework for measuring preferences for schools and neighborhoods. Journal of Political Economy, 115(4), 588–638

Beracha, E., & Seiler, M. J. (2014). The effect of listing price strategy on transaction selling prices. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 49(2), 237–255

Bernheim, B. D., & Meer, J. (2008). How much value do real estate brokers add? A case study,” NBER working paper, No. 13796.

Betts, J. R. (1995). Does school quality matter? Evidence from the national longitudinal survey of youth. Review of Economics and Statistics, 77(2), 231–250

Bishop, K. C., & Timmins, C. (2019). Estimating the marginal willingness to pay function without instrumental variables. Journal of Urban Economics, 109(C), 66–83.

Black, S. E. (1999). Do better schools matter? Parental valuation of elementary education”. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(2), 577–599

Brown, Z. (2019). Equilibrium effects of health care price information. Review of Economics and Statistics, 101(4), 699–712

Bucchianeri, G. W., & Minson, J. A. (2013). A homeowner’s dilemma: Anchoring in residential real estate transactions. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 89(C), 76–92.

Burdett, K., & Judd, K. (1983). Equilibrium price dispersion. Econometrica, 51(4), 955–969

Campbell, T. S., & Kracaw, W. A. (1980). Information production, market signalling, and the theory of financial intermediation. Journal of Finance, 35(4), 863–882

Card, D. & Krueger, A. B. (1996). Labor market effects of school quality: Theory and evidence. NBER Working Paper, No. 5450.

Cardella, E., & Seiler, M. J. (2016). The effect of listing price strategy on real estate negotiations: An experimental study. Journal of Economic Psychology, 52, 71–90

Chan, Y. S., & Leland, H. E. (1982). Prices and qualities in markets with costly information. Review of Economic Studies, 49(4), 499–516

Chan, Y. S., & Leland, H. E. (1986). Prices and qualities: A search model. Southern Economic Journal, 52, 1115–1130

Cheng, P., Lin, Z., Liu, Y., & Seiler, M. J. (2015). The benefit of search in housing markets. Journal of Real Estate Research, 37(4), 597–621

Chinloy, P., Hardin III, W., & Wu, Z. (2013). Price, place, people, and local experience. Journal of Real Estate Research, 35(4), 477–505

Clauretie, T. M., & Thistle, P. D. (2007). The effect of time-on-market and location on search costs and anchoring: The case of single-family properties. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 35(2), 181–196

Coey, D., Larsen, B. J., & Platt, B. C. (2019). Discounts and Deadlines in Consumer Search. mimeo.

Cooper, Z., Craig, S. V., Gaynor, M., & VanReenen, J. (2019). The price ain’t right? Hospital prices and health spending on the privately insured. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 134(1), 51–107

Cutler, D., & Glaeser, E. (1997). Are ghettos good or bad? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(3), 827–872

DellaVigna, S., & Gentzkow, M. (2019). Uniform pricing in U.S. retail chains, NBER working paper, No. 23996.

Diamond, P. A. (1971). A model of price adjustment. Journal of Economic Theory, 3(2), 156–168

Dranove, D., & Satterthwaite, M. A. (1992). Monopolistic competition when price and quality are imperfectly observable. RAND Journal of Economics, 23(4), 518–534

Efron, B. (1979). Bootstrap methods: Another look at the jackknife. Annals of Statistics, 7(1), 1–26

Efron, B., & Tibsharani, J. (1993). An introduction to the bootstrap. Chapman and Hall.

Ehrlich, G. (2013). Price and time to sale dynamics in the housing market: The role of incomplete information. mimeo.

Elder, H. W., Zumpano, L. V., & Baryla, E. A. (1999). Buyer search intensity and the role of the residential real estate broker. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 18(3), 351–368

Epple, D. (1987). Hedonic prices and implicit markets: Estimating demand and supply functions for differentiated products. Journal of Political Economy, 95(1), 59–80

Epple, D., & Sieg, H. (1999). Estimating equilibrium models of local jurisdictions. Journal of Political Economy, 107(4), 645–681

Farrell, J. (1980). A model of price and quality choice, with informed and uninformed buyers. mimeo, Department of Economics, M.I.T.

Gardiner, J., Heisler, J., Kallberg, J., & Liu, C. (2007). The impact of dual agency. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 35(1), 39–55

Genesove, D., & Mayer, C. J. (1997). Equity and time to sale in the real estate market. American Economic Review, 87(3), 255–269

Goldberg, P., & Verboven, F. (2001). The evolution of price dispersion in the European car market. Review of Economic Studies, 68(4), 811–848

Grennan, M. (2013). Price discrimination and bargaining: Empirical evidence from medical devices. American Economic Review, 103(1), 145–177

Haerdle, W., Werwatz, A., Mueller, M., & Sperlich, S. (2004). Density Estimation. Springer.

Hanushek, E. A. (1996). Measuring investment in education. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 10(4), 9–30

Harding, J. P., Rosenthal, S. S., & Sirmans, C. F. (2003). Estimating bargaining power in the market for existing homes. Review of Economics and Statistics, 85(1), 178–188

He, X., Lin, Z., Liu, Y., & Seiler, M. J. (2020). Search benefit in housing markets: An inverted u-shaped price and tom relation. Real Estate Economics, 48(3), 772–807

Hitsch, G., Hortacsu, A., & Lin, X. (2019). Prices and promotions in U.S. retail markets: Evidence from big data, NBER working paper, No. 26306.

Holmes, C., & Xie, J. (2018). Distortions in real estate transactions with out-of-state participants. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 57(4), 592–617

Ihlanfeldt, K., & Mayock, T. (2012). Information, search, and house prices: Revisited. Journal of Real Estate Financial Economics, 44(1), 90–115

Janssen, M. C. W., Moraga-Gonzalez, J. L., & Wildenbeest, M. R. (2005). Truly costly sequential search and oligopolistic pricing. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 23(5–6), 451–466

Johnson, K., Lin, Z., & Xie, J. (2015). Dual agent distortions in real estate transactions. Real Estate Economics, 43(2), 507–536

Kadiyali, V., Prince, J., & Simon, D. H. (2014). Is dual agency in real estate a cause for concern? Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 48(1), 164–195

Kmenta, J., & Gilbert, R. F. (1968). Small sample properties of alternative estimators of seemingly unrelated regressions. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 63(324), 1180–1200

Lambson, V. E., McQueen, R. G., & Slade, B. A. (2004). Do out of state buyers pay more for real estate? An examination of anchoring induced bias and search costs”. Real Estate Economics, 32(1), 85–126

Levitt, S. D., & Syverson, C. (2008). Market distortions when agents are better informed: The value of information in real estate”. Review of Economics and Statistics, 90(4), 599–611

Ling, D. C., Naranjo, A., & Petrova, M. T. (2018). Search costs, behavioral biases, and information intermediary effects. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 57(1), 114–151

Merlo, A., & Ortalo-Magne, F. (2004). Bargaining over residential real estate: Evidence from England. Journal of Urban Economics, 56(2), 192–216

Myer, N. F. C., He, L. T., & Webb, J. R. (1992). Sell-offs of U.S. real estate: The effect of domestic versus foreign buyers on shareholder wealth. Journal of the American Real Estate and Urban Economics Association, 20(3), 487–500.

Nechyba, T. J., & Strauss, R. P. (1998). Community choice and local public services: A discrete choice approach. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 28(1), 51–73

Northcraft, G. B., & Neale, M. A. (1987). Experts, amateurs, and real estate: An anchoring-and-adjustment perspective on property pricing decisions. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 39(1), 84–97

Olley, G. S., & Pakes, A. (1996). The dynamics of productivity in the telecommunications equipment industry. Econometrica, 64(6), 1263–1297

Robinson, P. M. (1988). Root-n consistent semiparametric regression”. Econometrica, 56(4), 931–954

Rothschild, M. (1974). Searching for the lowest price when the distribution of prices is unknown. Journal of Political Economy, 82(4), 689–711

Rutherford, R., Springer, T., & Yavas, A. (2005). Conflicts between principals and agents: Evidence from residential brokerage. Journal of Financial Economics, 76(3), 627–665

Rutherford, R., Springer, T., & Yavas, A. (2007). Evidence of information asymmetries in the market for residential condominiums. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 35(4), 23–38

Salop, S., & Stiglitz, J. (1977). Bargains and ripoffs: A model of monopolistically competitive price dispersion. Review of Economic Studies, 44(3), 493–510

Siebert, R. B. (2021). Heterogeneous foreclosure discounts of homes. Journal of Real Estate Research, forthcoming.

Sieg, H., Smith, V. K., Banzhaf, H. S., & Walsh, R. (2002). Interjurisdictional housing prices in locational equilibrium. Journal of Urban Economics, 52(1), 131–153

Silverman, B. W. (1986). Density estimation for statistics and data analysis. Chapman and Hall.

Stigler, G. J. (1961). The economics of information. Journal of Political Economy, 69(3), 213–225

Turnbull, G., & Sirmans, C. F. (1993). Information, search, and house prices. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 23(4), 545–557

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185, 1124–1131

Varian, H. (1980). A model of sales. American Economic Review, 70(4), 651–659

Watkins, C. (1998). Are new entrants to the residential property market informationally disadvantaged? Journal of Property Research, 15(1), 57–70

Yinger, J. (1978). The black-white price differential in housing: Some further evidence. Land Economics, 54(2), 187–206

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Stephen Martin, Kelly Bishop, seminar participants, and two anonymous referees for valuable feedback and support. We also thank the Tippecanoe County Assessor's Office, the Board of Realtors in Indiana, the Real Estate Agents Association in Indiana, and Real Estate Agent Amy Junius for support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Siebert, R.B., Seiler, M.J. Why Do Buyers Pay Different Prices for Comparable Products? A Structural Approach on the Housing Market. J Real Estate Finan Econ 65, 261–292 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-021-09841-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-021-09841-5