the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Controlling water infrastructure and codifying water knowledge: institutional responses to severe drought in Barcelona (1620–1650)

Santiago Gorostiza

Maria Antònia Martí Escayol

Mariano Barriendos

Combining historical climatology and environmental history, this article examines the diverse range of strategies deployed by the city government of Barcelona (Catalonia, NE Spain) to confront the recurrent drought episodes experienced between 1626 and 1650. Our reconstruction of drought in Barcelona for the period 1525–1821, based on pro pluvia rogations as documentary proxy data, identifies the years 1626–1635 and the 1640s as the most significant drought events of the series (highest drought frequency weighted index and drought duration index). We then focus on the period 1601–1650, providing a timeline that visualises rain rogation levels in Barcelona at a monthly resolution. Against this backdrop, we examine institutional responses to drought and discuss how water scarcity was perceived and confronted by Barcelona city authorities. Among the several measures implemented, we present the ambitious water supply projects launched by the city government, together with the construction of windmills as an alternative to watermills, as a diversification strategy aimed at coping better with diminishing water flows. We pay special attention to the institutional efforts to codify the knowledge about Barcelona's water supply, which in 1650 resulted in the Book of Fountains of the City of Barcelona (Llibre de les Fonts de la Ciutat de Barcelona). This manual of urban water supply, written by the city water officer after 3 decades of experience in his post, constitutes a rare and valuable source to study water management history but also includes significant information to interpret historical climate. We analyse the production of this manual in the context of 3 decades marked by recurrent episodes of severe drought. We interpret the city government aspiration to codify knowledge about urban water supply as an attempt to systematise and store historical information on infrastructure to improve institutional capacities to cope with future water scarcities.

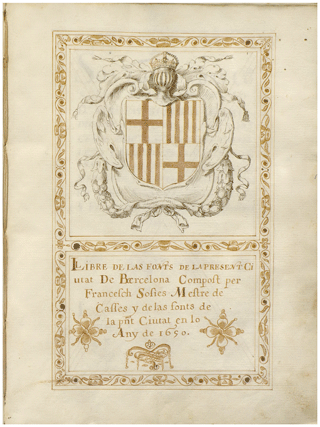

Around July 1650, during an intense episode of drought in Barcelona, the city water officer (“mestre de les fonts”) Francesc Socies started writing a book that described in great detail the water supply and distribution system of the city. At the time, Socies had been in his post for over 30 years, overseeing the city's fountains and water supply, and was approaching retirement. After decades of coping with drought frequently, and well aware of the precious experience gathered by Francesc Socies, the city government had asked him to compile his knowledge about Barcelona's water supply system. The resulting book should perpetually be kept in the city archives to shed light on the work of future city water officers and improve urban water management. In November 1650, Socies delivered what became known as the Llibre de les Fonts de la Ciutat de Barcelona (“Book of Fountains of the City of Barcelona”) (Archival source AS1).

This article focuses on the 3 decades (1620–1650) leading up to the codification of knowledge about Barcelona's water supply into the Book of Fountains and examines them from the perspective of historical climatology and environmental history. Our analysis reconstructs the severe droughts experienced in the city during this period and examines the strategies followed by the city government to cope with them, contributing to the growing scholarship on societal adaptation to past climate changes (Degroot, 2018). First, drawing on pro pluvia rogations (rain rogations) as proxy data, we identify the years 1626–1635 and the 1640s as the most significant drought events that occurred in Barcelona during the period 1521–1825 (highest drought frequency weighted index and drought duration index of the series). This previously unpublished drought reconstruction is the first contribution of our work, which confirms previous research on historical climatology that had pointed to the years 1625–1635 as severely dry (Díaz, 1984; Martín-Vide and Barriendos, 1995; Rodrigo and Barriendos, 2008). These results are coherent with a systematic analysis of 165 tree-ring series in the Mediterranean for the last 500 years, which points to an acute period of drought between 1620 and 1640, an episode that affected the whole Western Mediterranean (Nicault et al., 2008).

Second, following scholarship on the social response to past climate variability (Pfister et al., 1999), we examine the diverse range of strategies deployed by the Barcelona city government to confront the recurrent drought episodes experienced during the years 1626–1650. In contrast to the development of historical climatology in Catalonia, research on the human response to past climate variability is still scarce (Martí Escayol, 2019). The work of Antoni Simon i Tarrés, who highlighted the importance of drought among the complex interaction of factors that triggered social unrest in Catalonia during the late 1620s and 1630s, stands out among the few existing publications on the topic (Simon i Tarrés, 1981, 1992). Others have underlined that climate conditions in the 17th century accentuated the agricultural, social and political crisis (Serra i Puig and Ardit, 2008). The impact of climate variability in the Iberian Peninsula during the 17th century has also been stressed by Geoffrey Parker, who pointed out that Spain “suffered extreme weather without parallel in other periods, particularly in 1630–2 and 1640–3” (Parker, 2013, p. 289). Parker examined the Catalan revolt against the Spanish King Philip IV (1640–1652) emphasising the key impact of extreme weather events in Catalan society (Parker, 2013).

However, none of these authors examined in detail the human response to climatic variability in Catalonia during these years. More recently, by focusing on the case of the town of Terrassa (Barcelona region), Mar Grau-Satorras has analysed how local communities combined different strategies to cope with drought during the 17th century, including infrastructural, institutional and symbolic responses, which changed throughout time (Grau-Satorras, 2017; Grau-Satorras et al., 2016, 2021). Along these lines, our research focuses on the case of Barcelona as an example of Western Mediterranean urban agglomeration (40 000 citizens) under severe environmental stress. Among other institutional strategies in response to drought and diminishing water flows, we discuss the production of the Book of Fountains, underlining the relevance and novelty of the attempt of Barcelona city government to codify water knowledge in the form of a book for future urban city officers.

In line with research in historical climatology re-assessing traditional documentary sources or presenting innovative ones (Adamson, 2015; Veale et al., 2017), our research draws attention to the potential of urban water supply manuals as a rare but significant source to be considered to critically interpret institutional responses to droughts. While the Book of Fountains is known in Catalan historiography (Cubeles, 2011; Perelló Ferrer, 1996; Voltes Bou, 1967), it remains unpublished and has not been studied in depth. After carrying out the first complete transcription and analysis of the text, this is the first article that contextualises the writing of the Book of Fountains within the severe droughts experienced in Barcelona during the 17th century. Manuals of urban water supply constitute rare documentary sources, and we have only identified one similar book: Le Livre des Fontaines de Rouen, written by Jacques Le Lieur between 1524 and 1525 in the city of Rouen, France (Sowina, 2016).

The article proceeds as follows. In the next section, we provide an overview of the methods and sources used to reconstruct droughts during our period of study, as well as to review the institutional responses to it. In the “Results” section we present three previously unpublished figures that show the drought frequency weighted index and drought duration index for the period 1521–1825, together with a timeline that presents rain rogation levels in Barcelona between 1601 and 1650 at a monthly resolution. The results about institutional responses are presented in the form of two diagrams showing the main strategies followed by the city government and the specific years they were implemented. Next, the discussion section is subdivided into three parts. First, we examine how institutional responses to drought were intertwined with urban and political conflicts. Second, we discuss the Book of Fountains as a strategy for codifying knowledge transmission and improving urban water management. Third, we analyse the Book of Fountains as a tool to enhance water infrastructure control. In the conclusions, we summarise the relevance of our local case study and point out the potential of urban water supply manuals as historical sources for both climate reconstruction and past climate adaptation.

2.1 Drought reconstruction

The climatic conditions during the 17th century can be regarded as part of the climatic episode known as the Little Ice Age (LIA). Research on historical climatology has pointed to a higher frequency and severity of cold spells during this episode (Ogilvie and Jónsson, 2001; Pfister et al., 1996, 1998; White, 2014). More recently it has also identified and analysed a general increase in the irregularity of rainfall patterns, manifested in the emergence of hydrometeorological extreme episodes with great social and environmental impact. At the climatic scale, in the Spanish Mediterranean this increase in the frequency and severity of extreme hydrometeorological events manifests itself in periods of around 40 years for the case of extraordinary rainfalls leading to floods (Barriendos et al., 2019; Barriendos and Martin-Vide, 1998; Llasat et al., 2005).

Rain rogations have been successfully used as a proxy for the reconstruction of rainfall variability (Martín-Vide and Barriendos, 1995; Barriendos, 1996, 1997). Rogations were a mechanism to respond to environmental stress, in this case drought. The institutions involved (agricultural guilds, city councils, cathedral chapters) have left reliable and detailed records, with data at a daily resolution. In Catalonia, rain rogations are classified in five levels, according to their severity. These categories can be identified by the typology of religious liturgies, from simple rogations inside the church (low, level 1) to pilgrimages to sanctuaries (critical, level 5). An integrated index is obtained by weighting data according to the severity of each level of rogation. This index is standardised so that it can be compared with other populations and regions (Martín-Vide and Barriendos, 1995).

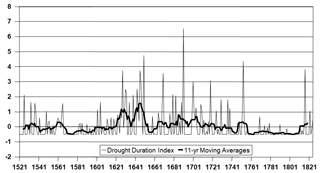

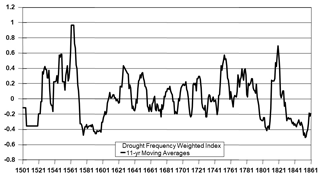

Figure 1Drought frequency weighted index (1501–1861). Standardised values. Eleven-year moving averages from four cities: Girona, Barcelona, Tarragona and Tortosa. Data adapted from Oliva et al. (2018).

Drawing on previous research based on this method and sources, Fig. 1 provides a general view of the frequency of extreme droughts for the period 1501–1861 with data from four Catalan cities near the Mediterranean coast at a yearly resolution (Barcelona, Girona, Tarragona and Tortosa) (data adapted from Oliva et al., 2018). This general view allows us to identify many recurring events of medium intensity and some of very high intensity for the Catalan coast. The relevant drought events identified are the following: 1520s, 1540s, 1560s, 1620s (ca. 1625–1635), 1750s, and 1812–1824.

In relation to 17th-century Catalonia, Fig. 1 shows two pulses of drought during our period of study (1620–1650): a higher one approximately between 1625–1635 and a lower one immediately after. This assessment is coherent with the systematic analysis of 165 tree-ring series in the Mediterranean for the last 500 years, which point to an acute period of drought between 1620 and 1640, an episode that affected the whole Western Mediterranean (Nicault et al., 2008).

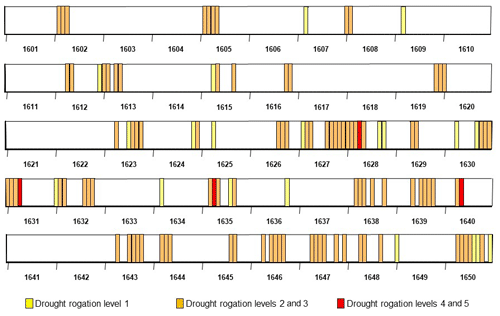

In order to document the impact of drought in Barcelona and the institutional measures to adapt to it, our research focuses on the Catalan capital leaving aside the other three cities included in Fig. 1. In the first place, we apply the drought frequency weighted index displayed in Fig. 1 to the local data of Barcelona (see Fig. 4 in the section “Results”, previously unpublished). Second, we take advantage of a variable that provides useful information to assess the length of drought episodes. In the case of Barcelona, level 2 of pro pluvia rogations involved the public exhibition of a specific relic: the remains of Santa Madrona (Martín-Vide and Barriendos, 1995). The public exhibition of this relic on the high altar of the cathedral lasted until the authorities established that the drought was over. In that moment, the urn containing the Saint's remains was taken back to the Chapel of Santa Madrona at the nearby mountain of Montjuïc. This liturgical pattern introduces the possibility of analysing the duration of drought episodes as perceived by local authorities, something that has not been studied in this geographical context. By accounting for the number of days per year that level 2 of drought was active in Barcelona and standardising the result to make it comparable with other cities, we obtain an annual index of drought duration for the period 1521–1825 (see Fig. 5 in the section “Results”, previously unpublished). Finally, since the data allow for an analysis at a monthly resolution, we aim at producing a timeline to describe the behaviour of drought and the different rogation levels focused on the study period 1600–1650. This timeline (see Fig. 6 in the section “Results”, previously unpublished) allows us to distinguish if the dry months were sporadic and irregular or appeared as a persistent anomaly for long periods.

2.2 Institutional response

Our analysis of the institutional response to drought focuses on the period 1620–1650. We provide a qualitative analysis of the records produced by the Consell de Cent (city government) in relation to water management during these years. Most of all, we interpret the creation of the Llibre de les Fonts in the context of the frequent drought of our period of study. This rare source, kept at the city archives, was written by the city water officer Francesc Socies during the summer of 1650, at the request of the city government (AS1, Fig. 2; AS2, ff. 325–326). The Book of Fountains is a manual about urban water supply, a text where Socies provides instructions that codify both the knowledge of his profession and the experience from his job position, where he was posted between 1620 and 1650. The manual aimed at guiding future interventions in the supply system and communicating what future city water officers should know.

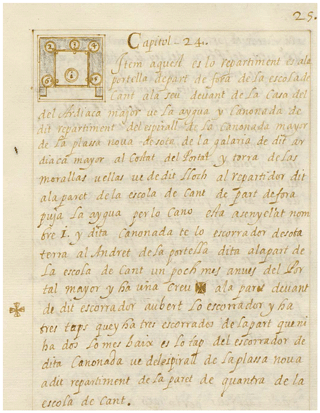

Figure 2First page of the Llibre de les Fonts, Manuscrits, AHCB1-002/CCAM 01/1G-076, Arxiu Històric de la Ciutat de Barcelona (AHCB).

The structure of the book follows the water distribution system and describes it as an interconnected network, from the drainage underground canals in the hills of Barcelona known as “water mines” (qanats) to the city fountains. The author indicates with high precision where each element is located, both for those visible and those hidden from view, underground or behind walls (water taps, pipes, water tanks or wells). In addition, throughout the book, the author provides a calendar for the system's maintenance within a particular urban space and time. Socies specifies where to intervene and how often, for instance in relation to the cleaning of pipes and curtailing the growth of tree roots that can disrupt sections of the system (e.g. every 2, 4 or 5 years). Nevertheless, Socies' temporal specifications do not only apply to maintenance but also to key historical information about water property rights. Finally, Socies refers several times to droughts and the lack of water supply experienced in the city during the study period.

In addition to our analysis of the Book of Fountains, a review of the secondary literature on urban history helped to identify valuable works that refer to measures approved by the city government during the 17th century to cope with drought and diminishing water flows (Perelló Ferrer, 1996; Voltes Bou, 1967). We have also reviewed the leaflets published by the city government during our period of study and found several connected to water management. In the first place, we located a pamphlet in defence of a project to build an irrigation canal to bring waters from the Llobregat River to Barcelona (AS3, published in 1627). Though this project was not carried out, we have traced several references to it in city chronicles and meeting records during the following years (AS4 and AS5). Our review has also identified four leaflets connected to a legal conflict concerning water rights, which in 1634 brought the Barcelona city government and the water officer Francesc Socies face to face with the cathedral chapter (AS6, AS7, AS8 (see Fig. 3) and AS9).

3.1 Drought reconstruction

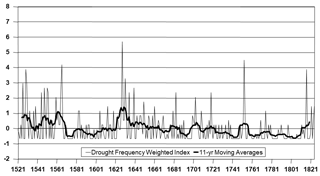

Drawing on pro pluvia rogations, Fig. 4 shows a distribution of drought frequency in Barcelona between 1521 and 1825 with different degrees of intensity. By using yearly weighted indexes, we identify the decades of 1560s and 1625–1635 as the two most significant drought events of these 3 centuries in the city. The latter, however, stands out for its extreme severity. Moreover, there was no similar experience with drought in the previous 50 years (approximately 1570–1620).

Figure 4Drought frequency weighted index. Standardised values. City of Barcelona (1521–1825). Data improved from Martín-Vide and Barriendos (1995).

Through the development of an index of drought duration based on the records about the public exhibition of Santa Madrona relic, Fig. 5 shows that the drought experienced in Barcelona during the late 1620s was perceived as longer than any other registered until that time. While it is difficult to extract more details with these historical records, it is evident that the drought registered had an extraordinary magnitude. However, the long duration of the rain rogations may also be related to the perception of an extreme anomaly by the city authorities, since almost no drought conditions had been experienced in the previous 50 years.

The analysis of drought duration presented in Fig. 5 reveals another significant issue. After the severe 1620s drought, which extends into the first part of the 1630s, there was a less intense episode, very close in time, around the 1640s. On this occasion the duration of rain rogations of level 2 – involving the exhibition of Santa Madrona – was even longer than in the previous episode (Fig. 5). These results do not allow us to analyse in detail the development of the drought episode but provide an entry point to the human response to an extraordinary climate event. The first drought period of the study (1620s to the first half of 1630s) had such a social impact that the almost consecutive episode of the 1640s generated a proportional response. In view of the impact of drought on water resources and with limited references available after two generations without similar events, the duration of the rain rogations may have been extended as a response against a challenging situation for local authorities.

Finally, Fig. 6 focuses on the first half of the 17th century, the period during which the most significant and long episodes of drought have been identified in the previous figures. Figure 6 visualises rain rogation levels at a monthly resolution for the first time in our geographical context. This timeline allows us to analyse whether drought appeared either sporadically and irregularly or as a persistent anomaly for longer periods. In the case of prolonged drought during the rainy seasons in the region (spring and autumn), the impacts in agriculture and water supply may have been particularly severe. The results shown in Fig. 6 allow us to identify the years 1626–1627 as the beginning of the 1620–1630s drought episode shown in Figs. 4 and 5. During the 1640s, the specific period identified spans from 1643 to 1650.

3.2 Institutional response

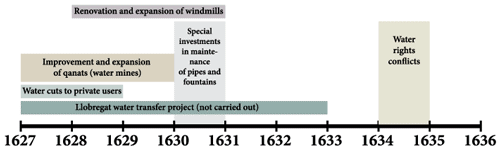

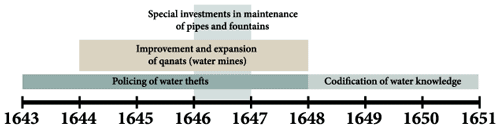

Throughout the period 1620 to 1650 the city government implemented a diverse range of institutional strategies to respond to drought. In the following paragraphs, we summarise these strategies, identified through our review of primary and secondary sources. Figures 7 and 8 synthesise these responses in relation to the two periods of drought identified (1620s–1630s and the 1640s).

One of the main strategies developed by the city council to cope with the diminishing water flows caused by drought was the improvement and expansion of the urban water supply sources. During the 17th century, the water supplied to Barcelona's fountains came from several underground drainage canals originating in the hills surrounding the city. These structures, known as mines d'aigua (“water mines”) in Catalan, were common in all the Mediterranean and originated in the medieval qanats established by Muslim settlers (Custodio, 2012; Guàrdia, 2011). On several occasions during our period of study water flows coming from these sources decreased significantly, triggering efforts from the Consell de Cent to improve and expand old qanats and to open new ones. Between 1627 and 1629, the city water officer built a new qanat that provided a significant increase in the waters delivered to Barcelona (Perelló Ferrer, 1996, pp. 126–127). During the second half of the 1640s the Consell de Cent approved the construction of a new qanat in Pedralbes (Perelló Ferrer, 1996, p. 129).

Other attempts to diversify the water sources of the city were more ambitious. In 1627 the city government proposed to build an open water canal (approximately 12 km long) connecting the river Llobregat to the city. The Consell de Cent regarded the Llobregat waters as the “universal solution” to the problem of water supply and published a pamphlet detailing the many advantages of the project. Several experts in water supply infrastructure came to Barcelona and worked together with the city water officer to draft a detailed proposal which was submitted to the Viceroy and eventually to the Spanish King (AS3). King Philip IV showed interest in the project but also concerns about the landowners affected (Voltes Bou, 1967, pp. 58–59). In 1633 the project made a comeback when the city officers called water supply experts to resume the work on the canal and even started marking it on the ground (AS4). However, the royal privilege needed was not obtained (AS5, pp. 137, 154–155) and the project did not go ahead (Voltes Bou, 1967, pp. 59–60; Perelló Ferrer, 1996, pp. 127–128).

Along with the investments devoted to expanding and diversifying the sources of water supply, the city government attempted to improve the efficiency of the existing system. In 1630–1631 it devoted substantial efforts to the conservation and maintenance of the city pipes, fixing broken sections, and cleaning those that were clogged by earth and tree roots. During the second half of the 1640s it also invested in the improvement of the city fountains (Voltes Bou, 1967, p. 60; Perelló Ferrer, 1996, pp. 127–129). In moments of acute scarcity, the city government would actively police water thefts from the urban supply system and, if needed, impose restrictions on private users. The severe drought experienced during 1627 and early 1628, for instance, was the justification for the city government to cut off the water supply to almost all private users in the city (Perelló Ferrer, 1996, p. 126). In order to confront water thefts during the 1640s, the city government went as far as approving a search of all the houses close to the main pipe to find where the water leak was or who had illegally drilled into the pipe and installed a tap (AS1, chap. 22; Perelló Ferrer 1996, p. 128) (see Figs. 7 and 8).

The city government's efforts to regulate water use by urban institutions and private actors sometimes created acute tensions. A remarkable example that occurred during our period of study involved the Consell de Cent and the cathedral chapter. In 1634, the city government's decision to cut water supply to the cathedral triggered a major scandal. The cathedral chapter excommunicated the city water officer and the members of the Consell de Cent for offending the property of the Church (AS9). Even if water flows to the cathedral were restored after its ancient water rights were demonstrated and the excommunications were lifted after several weeks, the city government publicly reasserted itself as the “master and owner of the waters that flow to [Barcelona's] fountains” (AS8).

Extreme drought did not only cause problems in the city fountains but also in the water mills needed to produce flour. During very dry periods, the water level in the irrigation canals might not be high enough for them to function. This situation forced the city government to transport the grain to locations farther from the city, thus increasing the associated costs and occasionally jeopardising the city's flour supply (Simon i Tarrés, 1992, pp. 165–169). The unreliability of watermills during severe droughts was invoked by the city government in their plea to bring the waters of the Llobregat River to Barcelona via a water canal. In fact, it was the reason why the city government had owned two windmills outside the city walls since earlier times (AS3). However, due to the almost complete absence of dry periods since the 1570s, these windmills were little used and fell into disrepair. In 1628, the Consell de Cent requested their renovation along with two new windmills; five more would follow in 1629. Therefore, the city government addressed the unreliability of watermills during dry years with a great expansion of the city windmills, which grew from two to nine (450 %) between 1628 and 1631 (Perelló Ferrer, 1996, pp. 286–288).

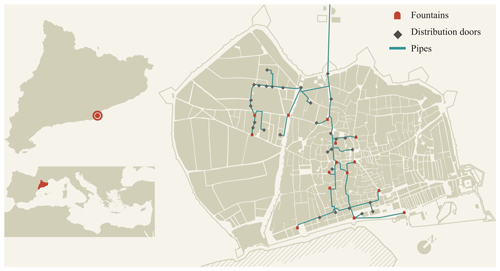

Figure 9The urban water supply network of Barcelona as described in the Llibre de les Fonts. Source: Guàrdia (2011), modified by the present authors.

Finally, towards the end of the study period (8 July 1648) the Consell de Cent asked the city water officer to write a book about Barcelona's water supply and the operation of the city's fountains. The Book of Fountains, written during the very dry year of 1650, provides a detailed description of the city water infrastructure, including each of the branches and sections of the city's main pipe, along with the buildings receiving a water supply and the location of the water conduits and fountains (see Fig. 9). The value of the knowledge compiled in the book was regarded as critical, and according to the city government's instructions, it could not leave the city government's grounds (AS2, ff. 325–326, 400).

The Book of Fountains did not only provide readers with a geography of the water network elements but also with a calendar for the system's maintenance and key historical information about water property rights and concessions to specific buildings. Moreover, it includes useful information for the reconstruction of the climate of the past. Socies' account points out the years 1626 and 1627 as the beginning of a long dry period in Barcelona. According to his testimony, the first 2 decades of the 17th century had been a time of water abundance when the city government supported the expansion of the water distribution system and granted water concessions to several aristocratic houses and monasteries (AS1, chaps. 65, 69, 79 and 98). All this came to an end between 1626–1627. In Socies own words, “the abundance of waters lasted until the year 1626 (...). Already in the year 1627 came a great drought and in the fountains of the city there was a great lack of water” (AS1, chap. 65). When writing the book in 1650, Socies visited the qanats of Nostra Senyora del Coll and pointed out that it was the first time in his life that he saw them dry. After 30 years on his post, Socies considered that as years passed by, the flow of water in the city had been decreasing. He underlined the importance of the qanat construction he had led in 1627–1629 to keep water running in Barcelona's fountains during the driest periods (AS1, chap. 65).

4.1 Drought stress and political tensions

In this section, we discuss how the unprecedented drought pulse starting in 1626–1627 heightened micro- and macropolitical tensions in Barcelona. By looking at three ways in which the institutional responses to drought were intertwined with urban and political conflicts, we shed light on the complex interlinkages between drought, water scarcity, food supply and politics at the local and regional scale.

The impacts of the severe dry period starting in 1627 went beyond Barcelona and critically disrupted the food supply during the following years. By 1628, a contemporary witness stated that “the dioceses of Barcelona, Tarragona and the plain of Urgell cry of thirst” (Simon i Tarrés, 1992, pp. 161–162). Between 1628 and 1631, drought and extreme climate events critically affected agriculture in Catalonia, resulting in bad crops and adding new tensions to both local and regional conflicts (Simon i Tarrés, 1992, pp. 158–161). The diminishing grain supplies could have been compensated with imports from southern France and Milan, but war and plague in these regions prevented it. The Barcelona city government boosted the construction of windmills to secure the transformation of grain into flour during dry periods when watermills were unreliable (see Fig. 7). However, the agricultural impact of drought in the region reduced the availability of grain.

During the spring of 1631, the protests regarding the price, scarcity and bad quality of bread in Barcelona resulted in violent riots that threatened the lives of the city government members. In response to this subsistence crisis, the Consell de Cent assumed full control of bread production, putting in place a centralised, street-by-street rationing system. In the end, wheat cargo coming from Mallorca in May 1631 alleviated the shortage (Simon i Tarrés, 1992). However, the strategy of enforcing a centralised rationing system during scenarios of scarcity – or whenever these scenarios seemed feasible – remained in use during the following years. This is consistent with other studies that have identified rationing limited resources such as food or water (either by centralising its distribution or applying sanctions) as adaptive responses to climate variability (Grau-Satorras et al., 2021).

However, the very mechanisms established to face subsistence crises were intertwined with power struggles, sometimes setting the scene for new conflicts. During 1633 the Barcelona city government continued to enforce control over bread production and distribution, put into practice 2 years earlier. The insistent warnings directed at the monasteries and the cathedral to prevent them from producing and distributing bread suggest that these regulations were far from being followed. In this context, on the 4 January 1634, a representative from the Consell de Cent confiscated a piece of bread that had been produced by the cathedral, confirming that this institution was disobeying the calls from the city government (AS5, pp. 192–194). The accusations escalated rapidly, and among the reprisals approved, the city government ordered the water officer to cut off the water supply to the cathedral. In order to enforce the food rationing mechanisms, the Consell de Cent banned access to another critical resource: water.

However, this decision triggered a major conflict. Arguing that cutting the water flow was an offence to the property of the Church, the cathedral chapter excommunicated the members of the Consell de Cent and Francesc Socies. While it was bread production and distribution, not water, that had originally been the cause of the dispute, legal rights about water supply were at stake. The critical value of water in the recent severe droughts helps explaining the reprisal chosen by the Consell and the virulent response of the cathedral. By questioning access to water, a quarrel over bread rationing and distribution rights transformed into a major legal dispute leading to the excommunication of the city government officials. As pointed out by Grau Satorras et al. (2016), water conflicts could occur independently of droughts but were certainly intensified by them. Moreover, they often reconfigured the way water rights were dealt with. In the case of Barcelona, the city government could impose restrictions regarding water use on certain monasteries or private urban users, but actors like the cathedral chapter actively resisted these regulations. The cathedral chapter proved that its water rights went back as far as 1355, as shown by the documents kept in its archive (AS1, chap. 26; AS6, AS9). Water supply to the cathedral was restored, but in the legal dispute that followed, the Consell reasserted its role as the institution responsible for maintaining and overseeing the urban water supply. Mutual accusations between the cathedral and the Consell continued for months, even if the excommunications were provisionally lifted after a few weeks (AS5, pp. 205–206; AS6, AS7, AS8, AS9).

Finally, among the diverse range of strategies launched by the city government in these years (see Fig. 7) one stands out for its ambition and scale: the project to build a canal bringing the waters of the Llobregat River to Barcelona. Proposed as early as 1627, the project harmed the interests of aristocratic landowners, who opposed it consistently. The petition reached King Philip IV in the aftermath of his meeting with the representative body of Catalonia (Corts), held in 1626, where the King's proposal to raise an economic and human contribution from Catalonia to support the Spanish army had failed (Elliott, 1984; Parker, 2013). The situation repeated itself a few years later, in 1632, at a time when Barcelona received less than a third of its usual water supply (Voltes Bou, 1967, p. 59). The dialogue about the project was resumed coinciding with a new fiasco at the meeting of the Catalan Corts with the King. The permission and royal privilege from King Philip IV were never obtained, and the project came to nothing despite the advanced preparations carried out by the Consell de Cent (Perelló Ferrer, 1996, pp. 127–128). Three centuries were still to pass until the waters of the Llobregat were channelled to Barcelona (Burgueño, 2008; Saurí et al., 2014; Tello and Ostos, 2012).

Facing decreasing water flows, the city government's project to build a canal from the Llobregat River was an ambitious attempt to increase the variety of water sources supplying the city. Diversifying the sources of critical resources is an adaptive strategy to cope with climate variability that has been identified in several contexts (Grau-Satorras et al., 2021). Lacking the political support needed for a major infrastructure like the Llobregat canal, local authorities in Barcelona focused on alternative, less expensive versions of the same strategy: they built new qanats, expanded the old ones and invested in the maintenance of the existing system (see Fig. 7). Similarly, when watermills proved to be unreliable, the city government rapidly approved the renewal and expansion of windmills. Altogether, by diversifying water and energy sources, they increased their adaptive capacity in a time of recurrent drought.

4.2 Knowledge transmission and adaptation

Under the light of the recurring droughts experienced between 1626 and 1650, the efforts of the city government to codify water knowledge into a book can be interpreted as an attempt to improve future management by collecting the knowledge of the past. Like private diaries (Adamson, 2015) or peasant family books (Grau-Satorras et al., 2021; Torres i Sans, 2000), the Book of Fountains aimed at gathering and transmitting experiences to future generations. Following Grau-Satorras et al. (2021), its production can be interpreted as an adaptive strategy consisting of storing information to better cope with future climate variability. However, unlike private diaries or family books produced at the household level, the Book of Fountains was an initiative of urban institutional actors that involved the whole city of Barcelona and its water sources outside the city walls.

The city government asked Socies to write a book in the summer of 1648, after a significantly dry spring and 5 years of recurrent droughts (see Fig. 6). During these years, the water stress suffered in the city made any suspected water theft a critical matter. The aggressive approach demonstrated by the city authorities in policing water thefts between 1643 and 1648 (see Fig. 8) marks an increased awareness of the importance of controlling urban water infrastructure (see Sect. 4.3). The need to expand urban water flows also involved investments in new qanats and extraordinary funds for the maintenance of the supply network (see Fig. 8). All this work required additional expenditures because the salary paid to the city water officer included only maintenance tasks. Accordingly, the city government considered that with the assistance of a book compiling urban water knowledge, the expenditure related to city fountains would decrease. The economic reasons to write the Book of Fountains were explicitly mentioned in the petition directed to Francesc Socies (AS2, ff. 325–326).

When it came to intervening in urban water infrastructure, the city government depended on the city water officer. The severe impact of droughts during the 1630s and the 1640s only made these circumstances more evident. By the late 1640s, the city water officer was ageing with no successor in sight and the precious knowledge he embodied was at risk of being lost. In this context, the city government saw an opportunity to intervene in the process of knowledge transmission by putting forward a proposal to write a book. Only in 1650 did Francesc Socies agree to the proposal, in exchange for a salary until the end of his life (AS2, ff. 325–326). The Book of Fountains was written during the continuously dry months of 1650 (see Fig. 6) which caused the loss of harvest and made the year known as “the year of misery” (Guàrdia et al., 1986, p. 105).

Perhaps key to Socies' decision to accept writing the Book of Fountains was the fact that the water officer had no direct relatives to whom pass on his knowledge and job post. Traditionally, when approaching retirement, the city water officer would ask the city government for permission to perform his duties accompanied by an assistant – usually his son or son-in-law. After working together for several years the apprentice would then replace the city water officer (Perelló Ferrer, 1996, p. 77). This father-to-son tradition of knowledge transmission was common within guild structures, where family and the family house were units of production (for the Catalan context, see for instance Creixell i Cabeza, 2008; Solá, 2008). Within this context, knowledge about professions was transmitted to direct relatives and to apprentices. Therefore, knowledge transmission combined a type of oblique transmission (teacher to pupil) with a vertical type (father to son, uncle to nephew) (Leonti, 2011). This mechanism of transmission could sometimes involve the creation of dynasties of the same families in the same job post, keeping knowledge away from the city government (Montaner i Martorell, 1990, p. 177).

By requiring Socies to write a book compiling his knowledge, the city government aimed at interceding in the circuit of knowledge transmission. In other words, it aimed at putting oblique knowledge transmission under institutional control. The production of the Book of Fountains should be contextualised within the emergence of technical and practical manuals to transmit knowledge (Cifuentes i Comamala, 2006; Eamon, 1994; Long, 2001). The information stored in these manuals, however, was not meant to be made “public” in the modern sense. In the case of the Book of Fountains, water knowledge could not be disseminated for the sake of the institutions' own interests and for security reasons. The process of knowledge transmission revealed critical details about the location of water infrastructure, potentially subject to attack or disruption. Secrecy around infrastructure was strategic for the survival of the city, both with regard to external circumstances – the 1630s and 1640s were marked by war and the threat of military siege – and internal struggles with other city institutions such as the cathedral chapter. The strategic value of this knowledge explains the city government's instructions, which established that the book should remain perpetually in the city government's premises. This also showed an explicit intention of appropriating the knowledge inherently associated with the water officer's job post, restricting the access to it to those authorised by the city government.

Writing the Book of Fountains was about compiling the knowledge of the past but also about creating an object that could store future information. Francesc Socies demanded the involvement of his readers – future city water officers – to ensure that the book remained a useful tool. He asked them to record at the margins of the text any intervention in the water network, thus keeping knowledge up to date for future generations (AS1, f. 262). By involving future water officers in the authorship, the book aimed at becoming a transgenerational endeavour, a collective heritage under the control of the city government. In this way it became useful for the present as a physical object but also a perdurable, vital tool for the city's future. By obtaining a book that transmitted knowledge to future managers, the city government aimed at improving the institutional capacity to respond to future environmental stress, while it reduced its dependence on the city water officer. Moreover, armed with the knowledge compiled in the book, the city government was much better equipped to impose control over urban water users.

4.3 Enforcing control over water infrastructure

The scandal of the excommunication of the Consell de Cent and the city water officer after the water cut-off to the cathedral in 1634 came after some of the driest years remembered in Barcelona (see Figs. 4, 5 and 6). The city government came out of this conflict with renewed awareness about the importance of enforcing control over the water supply but also of monitoring information about water concessions and water rights, which could help avoid similar conflicts in the future. In line with the declaration that the city was “master and owner of the waters that flow to its fountains” (AS8), the city government devoted more and more attention to watching its water resources and remained wary of any violation of its water rights.

The production of the Book of Fountains was consistent with this strategy. The ambition to write a book containing urban water knowledge and the explicit requirement that it should be kept in the city government's grounds made clear the Consell's determination to reinforce its position as the institution responsible for water management in the city and therefore to reaffirm its capacity to use water as a tool to control urban space (AS2, ff. 325–326). In other words, enhancing the city government's control over urban water flows was also one of the goals behind the codification of water knowledge. The Book of Fountains was not only a way of storing information and improving adaptation to future climate variability. It also meant creating a valuable tool to enforce control over urban water flows and infrastructure. In terms of water property and rights, writing was an instrumental juridical tool for the city government to reaffirm its political power.

Figure 10Book of Fountains, chap. 24. On the lower left side, a cross marks a reference for the reader. The text refers to the location of the same cross in the urban fabric. Source: Llibre de les Fonts, Manuscrits, AHCB1-002/CCAM 01/1G-076, Arxiu Històric de la Ciutat de Barcelona (AHCB).

Through the pages of the Book of Fountains, the city water officer established the itinerary of urban waters from source to tap, defining who the proprietor of this knowledge was and institutionalising who had the power to control it. When referring to specific places in the city, he often established a symbolic relation between the written text and the urban fabric. To connect the text with the territory, Francesc Socies used a symbol – the cross – either in the text or in its margins, making its location easier to find for readers. These crosses written in the book refer to crosses chiselled in the stone walls of street buildings, indicating specific elements of water infrastructure hidden from view and thus binding the book pages with the urban fabric of the city. In other words: the author inscribed urban water geography into the pages of the Book of Fountains (see Fig. 10).

This intention of controlling urban space, based on the need of preserving the water supply, was also explicit in Socies' instructions to future managers. In order to keep a regular water flow running in the city's fountains, the city government needed to be able to detect and solve any incident rapidly, particularly in relation to water thefts. To this end, Socies explained how he had been remaking the water network that ran through internal parts of buildings, moving pipes to their external sections to hinder any attempt to illegally tap into them. He recommended continuing with these reforms in the future, so that the water infrastructure remained as much as possible within reach of the city water officer, simplifying its surveillance (AS1, chaps. 26, 78 and 79).

This article examined past climate variability in the city of Barcelona (Western Mediterranean) focusing both on drought reconstruction and the institutional responses to it. First, drawing on pro pluvia rogations as documentary proxy data, we provided a detailed reconstruction of drought frequency and duration between the years 1521 and 1825. The years 1625–1635 register the highest drought frequency weighted index of the series (Fig. 4), while the 1640s stand out in the drought duration index (Fig. 5). Second, we examined the institutional strategies followed by the city government in response to drought. Among other strategies, these involved diversifying the sources of urban water supply, enforcing restrictions over water uses and compiling the city water officer's knowledge into a book. We discussed these actions considering the complex interlinkages of drought with food supply and social unrest.

By focusing on the historical analysis of drought in Barcelona, our research corroborates and expands previous work that had identified a dry period in the Western Mediterranean between 1620–1640 (Martín-Vide and Barriendos, 1995; Nicault et al., 2008). Moreover, by examining the social impacts of drought in a major city of 40 000 inhabitants, we contribute to the discussion about the importance of climate variability among the factors that contributed to social unrest in Barcelona and Catalonia during the years leading to the Catalan Revolt (1640–1652). In addition, our analysis of the institutional strategies to cope with drought contributes to the scholarship on societal adaptation to climate variability (Degroot, 2018; Grau-Satorras et al., 2021). In this regard, among the strategies analysed, the codification of urban water knowledge stands out for its novelty. Finally, by showing how the information collected in the Book of Fountains can be used both for reconstructing past drought events and for examining institutional adaptation, we argue that manuals of urban water management are rare but valuable documentary sources to be considered in the field of historical climatology.

Written in 1650, right at the end of the most significant drought period identified in Barcelona between 1521 and 1825, the Book of Fountains offers an authoritative voice on the perception of urban water flows: that of the city officer in charge and his 30 years of experience. His assessments of the severity of drought during the years 1626–1627 or the summer of 1650 correspond to our results of the analysis of pro pluvia rogations. This cross-check reinforces the authority of both documentary sources used in our research. In essence, the Book of Fountains constitutes a mechanism to store and transmit key knowledge to cope better with environmental stress. In a context marked by drought and diminishing urban water flows, the Book of Fountains was a complex form of adaptation directed at improving the efficiency of urban water management systematising historical information about repairs and maintenance, reducing expenditure, and preventing conflicts about water rights.

From this perspective, the Book of Fountains can be interpreted as an outcome of the institutional learning of 3 decades of coping with severe water stress. Years of local and regional tensions reinforced the city government's legal claims over the management of urban water supply. A coherent step to reassert the position of the Consell de Cent as the “master and owner of the waters that flow to [Barcelona] fountains” was to codify knowledge about urban water rights, water distribution and maintenance into a book. In times of drought, more than ever, the knowledge about the old qanats, pipes, deposits and fountains that formed the water supply network, together with the centenary water rights that regulated it, was key to the exercise of political power. A book containing all this information was a treasure that had to be carefully kept for future generations.

- –

[AS1] Llibre de les Fonts, Manuscrits, AHCB1-002/CCAM 01/1G-076, Arxiu Històric de la Ciutat de Barcelona (AHCB).

- –

[AS2] AHCB, Deliberacions, Consell de Cent II-159, 1650.

- –

[AS3] Consell de Cent, Barcelona. “Discurs fet per orde dels consellers, obrers, y saui Concell de Cent, en lo aniuellar y aportar una sequia de aygua del riu de Lobregat, à la ciutat de Barcelona, als 9 de maig 1627”, Manuscrits Bonsoms, F. Bon. 5410, Biblioteca de Catalunya.

- –

[AS4] AHCB, Deliberacions, Consell de Cent II-142, 1633, fol. 144–147.

- –

[AS5] AHCB, Manual de novells ardits vulgarment apellat Dietari del Antich Consell Barceloní, vol. 11 (1632–1636).

- –

[AS6] Consell de Cent, Barcelona. “Informacion de la ivsticia qve tiene la civdad de Barcelona en la cavsa sobre qve aora trae pleyto con el Cabildo de la Santa Iglesia Catedral de la misma ciudad en el Tribunal y Corte eclesiastica del Illustrissimo Señor Arçobispo de Tarragona”, 1634. F.Bon. 5402, Biblioteca de Catalunya.

- –

[AS7] “Resolucion theologica en la duda que en esta ciudad de Barcelona ha hauido sobre sí los que concurrieron en quitar el agua que sale en las fuentes de los claustros de la Santa Iglesia del Asseo desta ciudad por espacio de algunas horas incurrieron en las censuras de las constituciones prouinciales tarraconeneses y apostolicas”, 1634. F.Bon. 4873, Biblioteca de Catalunya.

- –

[AS8] Consell de Cent, Barcelona. “Por la civdad de Barcelona y Francisco Sossies, maestro de las fventes, con el Cabildo de la Iglesia Maior acerca de las censuras declaradas contra el dicho Sossies”, 1634. F.Bon. 10964, Biblioteca de Catalunya.

- –

[AS9] Capítol de la Catedral de Barcelona. “Per lo Capitol y canonges de la Seu de Barcelona, en defensa de la sentencia proferida per lo official ecclesiastich a 5 de Ianer 1634, declarant que Fra[n]cesch Socies, mestre de les fonts de la ciutat, y los demes complices en lleuar la aygua de la font que te dita iglesia eran excomunicats y posant entredit”, 1634. F.Bon. 11466, Biblioteca de Catalunya.

The research dataset on historical drought in Barcelona prepared by Mariano Barriendos and used to construct the monthly drought index, yearly drought index and yearly weighted drought index is available in the Zenodo repository: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4695361 (Barriendos, 2021).

SG conceived this research with MAME and wrote the introduction, conclusions, and Sects. 2.2, 3.2, 4.1 and 4.3 of the text. He made significant contributions to the rest of the article. In addition, he handled the coordination, integration, translation and revision of texts, as well as the peer-review process.

MAME conceived this research with SG and wrote Sect. 4.2 of the text. MAME transcribed the Llibre de les Fonts de la Ciutat de Barcelona and made significant contributions to Sects. 1, 4.1 and 5.

MB prepared the drought series for Catalonia and Barcelona, handled the database organisation, statistical treatment, graphic production, and preparation of the tables and figures. MB wrote Sects. 2.1 and 3.1 of the text.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This article is part of the special issue “Droughts over centuries: what can documentary evidence tell us about drought variability, severity and human responses?”. It is not associated with a conference.

Santiago Gorostiza acknowledges financial support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, through the “María de Maeztu” programme for Units of Excellence (CEX2019-000940-M). This article was first conceived during a research stay at the Department of History of Georgetown University in Washington D.C.; Santiago Gorostiza thanks John McNeill and Dagomar Degroot for their encouragement to pursue this work. Santiago Gorostiza presented this research at the European Society of Environmental History in Tallinn (August 2019) and the Watermarks workshop at ICTA-UAB (October 2019). We thank the participants of these events and the reviewers of this article for their constructive comments and criticisms. We are particularly grateful to Xavier Cazeneuve for his support throughout this research and to Ekaterina Chertkovskaya for her careful reading of the text.

This research has been supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, through the “María de Maeztu” programme for Units of Excellence (CEX2019-000940-M).

This paper was edited by Andrea Kiss and reviewed by Mar Grau-Satorras and Inês Amorim.

Adamson, G. C. D.: Private diaries as information sources in climate research, WIRES Clim. Chang., 6, 599–611, https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.365, 2015.

Barriendos, M.: El clima historico de Catalunya (siglos XIV-XIX). Fuentes, métodos y primeros resultados, Rev. Geogr., 30–31, 69–96, 1996.

Barriendos, M.: Climatic variations in the Iberian Peninsula during the late Maunder minimum (AD 1675-1715): An analysis of data from rogation ceremonies, Holocene, 7, 105–111, https://doi.org/10.1177/095968369700700110, 1997.

Barriendos, M.: Historical drought in Barcelona (Spain) dataset, Zenodo, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4695361, 2021.

Barriendos, M. and Martin-Vide, J.: Secular climatic oscillations as indicated by catastrophic floods in the Spanish Mediterranean coastal area (14th-19th centuries), Clim. Change, 38, 473–491, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005343828552, 1998.

Barriendos, M., Gil-Guirado, S., Pino, D., Tuset, J., Pérez-Morales, A., Alberola, A., Costa, J., Carles Balasch, J., Castelltort, X., Mazón, J., and Ruiz-Bellet, J. L.: Climatic and social factors behind the Spanish Mediterranean flood event chronologies from documentary sources (14th – 20th centuries), Glob. Planet. Change, 182, 102997, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2019.102997, 2019.

Burgueño, J.: El Mapa com a llenguatge geogràfic. Recull de textos històrics (ss. XVII-XX): Diago, Borsano, Aparici, Canellas, Massanés, Bertran, Cerdà, Papell, Ferrer, Vila, Societat Catalana de Geografia, Barcelona, 2008.

Cifuentes i Comamala, L.: La ciència en catalaÌ a l'Edat Mitjana i el Renaixement, 2a ed. rev., Universitat de Barcelona, Palma de Mallorca, Spain, 2006.

Creixell i Cabeza, R. M.: L'ofici de fuster a la Barcelona del set-cents. Noves aportacions documentals, noves mirades, Locus Amoenus, 9, 229–247, https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/locus.189, 2008.

Cubeles, A.: El “Llibre de les fonts” del mestre Socies i l'abastament d'aigua de beure a Barcelona al segle XVII, in: La Revolució de l'aigua a Barcelona: de la ciutat preindustrial a la metròpoli moderna, 1867-1967, edited by: Guàrdia i Bassols, M., Ajuntament de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 45–50, 2011.

Custodio, E.: The History of Hydrogeology in Spain, in: History of Hydrogeology, edited by: Howden, N. and Mather, J., Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton, USA, 291–316, 2012.

Degroot, D.: Climate change and society in the 15th to 18th centuries, WIRES Clim. Chang., 9, e518, https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.518, 2018.

Díaz, M. P.: Aproximación a la climatología en la Cataluña del siglo XVII (según fuentes de la época), in Primer Congrés d'Història Moderna de Catalunya: Barcelona, del 17 al 21 de desembre de 1984, 255–266, 1984.

Eamon, W.: Science and the secrets of nature: books of secrets in medieval and early modern culture, Princeton University press, Princeton, NJ, USA, 1994.

Elliott, J. H.: The revolt of the Catalans: a study in the decline of Spain (1598-1640), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1984.

Grau-Satorras, M.: Adaptation before anthropogenic climate change: a historical perspective on adaptation to droughts in Terrassa (1600–1870s, NE Spain), PhD thesis, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain, available at: https://www.tesisenred.net/handle/10803/405252 (last access: 15 January 2021), 2017.

Grau-Satorras, M., Otero, I., Gómez-Baggethun, E., and Reyes-García, V.: Long-term community responses to droughts in the early modern period: the case study of Terrassa, Spain, Ecol. Soc., 21, 33, https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08232-210233, 2016.

Grau-Satorras, M., Otero, I., Gómez-Baggethun, E., and Reyes-García, V.: Prudent peasantries: Multilevel adaptation to drought in early modern Spain (1600–1715), Environ. Hist. Camb., 27, 3–36, 2021.

Guàrdia, J., Pladevall i Font, A., and Simon i Tarrés, A.: Guerra i vida pagesa a la Catalunya del segle XVII: segons el Diari de Joan Guàrdia, pagès de l'Esquirol, i altres testimonis d'Osona, Curial, Barcelona, Spain, 1986.

Guàrdia, M.: L'aigua de les fonts, in: La Revolució de l'aigua a Barcelona: de la ciutat preindustrial a la metròpoli moderna, 1867–1967, Ajuntament de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 40–44, 2011.

Leonti, M.: The future is written: Impact of scripts on the cognition, selection, knowledge and transmission of medicinal plant use and its implications for ethnobotany and ethnopharmacology, J. Ethnopharmacol., 134, 542–555, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2011.01.017, 2011.

Llasat, M. C., Barriendos, M., Barrera, A., and Rigo, T.: Floods in Catalonia (NE Spain) since the 14th century. Climatological and meteorological aspects from historical documentary sources and old instrumental records, J. Hydrol., 313, 32–47, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2005.02.004, 2005.

Long, P. O.: Openness, secrecy, authorship: technical arts and the culture of knowledge from antiquity to the Renaissance, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, USA, 2001.

Martí Escayol, M. A.: The environmental history of the Catalan-speaking lands, Catalan Hist. Rev., 12, 43–55, https://doi.org/10.2436/20.1000.01.155, 2019.

Martín-Vide, J. and Barriendos, M.: The use of rogation ceremony records in climatic reconstruction: a case study from Catalonia (Spain), Clim. Change, 30, 201–221, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01091842, 1995.

Montaner i Martorell, J. M.: La Modernització de l'utillatge mental de l'arquitectura a Catalunya: 1714–1859, Institut d'Estudis Catalans, Barcelona, Spain, 1990.

Nicault, A., Alleaume, S., Brewer, S., Carrer, M., Nola, P. and Guiot, J.: Mediterranean drought fluctuation during the last 500 years based on tree-ring data, Clim. Dyn., 31, 227–245, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-007-0349-3, 2008.

Ogilvie, A. E. J. and Jónsson, T.: “Little Ice Age” Research: A Perspective from Iceland, Clim. Change, 48, 9–52, 2001.

Oliva, M., Barriendos, M., Benito, G. and Cuadrat, J. M.: The Little Ice Age in Iberian mountains, Earth-Sci. Rev., 177, 175–208, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2017.11.010, 2018.

Parker, G.: Global Crisis: War, Climate Change & Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century, Yale University Press, New Haven, USA, 2013.

Perelló Ferrer, A. M.: L'arquitectura civil del segle XVII a Barcelona, Publicacions de l'Abadia de Montserrat, Barcelona, Spain, 1996.

Pfister, C., Schwarz-Zanetti, G., and Wegmann, M.: Winter severity in Europe: The fourteenth century, Clim. Change, 34, 91–108, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00139255, 1996.

Pfister, C., Luterbacher, J., Wegmann, M., and History, E.: Winter air temperature variations in western Europe during the Early and High Middle Ages (AD 750-1300), Holocene, 8, 535–552, 1998.

Pfister, C., Brázdil, R., and Glaser, R., Eds.: Climatic Variability in Sixteenth-Century Europe and Its Social Dimension, Springer Science, Dordrecht, the Netherlands, 1999.

Rodrigo, F. S. and Barriendos, M.: Reconstruction of seasonal and annual rainfall variability in the Iberian peninsula (16th–20th centuries) from documentary data, Glob. Planet. Change, 63, 243–257, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2007.09.004, 2008.

Saurí, D., March, H., and Gorostiza, S.: Des ressources conventionnelles aux ressources non conventionnelles: l'approvisionnement moderne en eau de la ville de Barcelone, Flux, 97–98, 101–109, 2014.

Serra i Puig, E. and Ardit, M.: Història Agrària dels Països Catalans, Vol 3, Edat Moderna, Fundació Catalana per a la Recerca, Barcelona, Spain, 2008.

Simon i Tarrés, A.: Catalunya en el siglo XVII. La revuelta campesina y popular de 1640, Estud. Gen. Rev. la Fac. Lletres la Univ. Girona, Vol. 1, 137–147, 1981.

Simon i Tarrés, A.: Els anys 1627-32 i la crisi del segle XVII a Catalunya, Estud. d'Historia Agrar., 9, 157–180, 1992.

Solá, A.: Impressores i llibreteres a la Barcelona dels segles XVIII i XIX, Recer. Història, Econ. i Cult., 56, 91–129, 2008.

Sowina, U.: Water, Towns and People, Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2016.

Tello, E. and Ostos, J. R.: Water consumption in Barcelona and its regional environmental imprint: A long-term history (1717–2008), Reg. Environ. Chang., 12, 347–361, 2012.

Torres i Sans, X.: Els llibres de famiìlia de pagès. Segles XVI-XVIII: memóries de pagès, memóries de mas, Institut de Llengua i Cultura Catalanes de la Universitat de Girona, Girona, Spain, 2000.

Veale, L., Endfield, G., Davies, S., Macdonald, N., Naylor, S., Royer, M., Bowen, J., Tyler-jones, R., and Jones, C.: Dealing with the deluge of historical weather data: the example of the TEMPEST database, Geo Geogr. Environ., 4, e00039, https://doi.org/10.1002/geo2.39, 2017.

Voltes Bou, P.: Historia del abastecimiento de agua de Barcelona, Sociedad General de Aguas de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 1967.

White, S.: The Real Little Ice Age, J. Interdiscip. Hist., XLIV, 327–352, https://doi.org/10.1162/JINH_a_00574, 2014.