Abstract

The present paper is a continuation of a previous one by the same title, the content of which faced the issue concerning the relations of coreference and qualification in compliance with the Navya-Nyāya theoretical framework, although prompted by the Advaita-Vedānta enquiry regarding non-difference. In a complementary manner, by means of a formal analysis of equivalence, equality, and identity, this section closes the loop by assessing the extent to which non-difference, the main issue here, cannot be reduced to any of the former. The following sections of this study will focus on the assessment of the eventual possibility of causation and transformation in non-difference.

Similar content being viewed by others

As stated in the first part of this investigation (P1), non-difference

( )—closely linked to the notion of coreference (sāmānādhikaraṇya, Ṇ)—cannot be reduced to identity or equality. In the following sections I will try to definitely demonstrate why this is the case, but not before having discussed how non-difference cannot be subsumed to the relation of equivalence, either.Footnote 1

)—closely linked to the notion of coreference (sāmānādhikaraṇya, Ṇ)—cannot be reduced to identity or equality. In the following sections I will try to definitely demonstrate why this is the case, but not before having discussed how non-difference cannot be subsumed to the relation of equivalence, either.Footnote 1

Equivalence

In an axiomatic theory of sets, equivalence (E) is a binary relation capable of formally expressing the naive concept ‘possessing the same property’.Footnote 2 In Nyāya Kośa (NK), equivalence is described sub voce tulyatva1kha.Footnote 3 In this manner, x is equivalent (tulya) to y (〈x, y〉∈E) if it shares with y a common property (dharmavattva) even while keeping itself distinct from it (bhinnatva).Footnote 4

Be it considered, for instance, the indefinite generic statement: gaur gāṃ janayati (‘A cow gives birth to a cow’), or the following indefinite non-generic one: gām ānaya (‘Fetch a cow’). In all of these cases, by reason of their indefinite character, if a cow (g) possesses the property cow-ness (gotva, gt), then a second cow (g′) might be said to be equivalent to g with respect to the property gotva. ‘That cow is equivalent to this one’—so gaur etasya gos tulyaḥ—will appear in NL as:

[8] (g′. gt)⌝ E ⌞(g. gt)

yad tulyatvam idaṃ-go-niṣṭha-gotva(vattva)-āvacchinnaṃ tad adaḥ-go-niṣṭha-gotva(vattva)-nirūpitam; ‘Equivalence, conditioned by cow-ness in that cow, is limited by cow-ness in this cow’; iff (g, g′) ∈(|gt| = G) (dharmavattva = gotvavattva; cf. fn. 3: NK: 991) ∧ g′≠ g (bhinnatve sati; cf. fn. 3: NK, p. 991) ∧ |g′. gt| ⊆ |E⌞(g. gt)| (‘Cow-ness in cow g′ is a sub-set of What is equivalent to Cow-ness in cow g’); that is, 〈g, g′〉 ∈ Egt.Footnote 5

As shown by the previous example, in general the relation of equivalence appears as necessarily bound to domain multiplicity—setting aside, for the moment, the trivial case of the equivalence of an element with itself (reflexive equivalence). In this respect, let us consider the definition of jāti or sāmānya: “[…] sāmānyam iti | tallakṣaṇaṃ tu nityatve saty anekasamavetvam”; “[…] The ‘universal’. While its definition is: the property which, being constant, is inherent in many [particulars]” (NSM 1988, pp. 97–98).Footnote 6 It follows that all individuals (vyakti) belonging to a given jāti are by definition equivalent to each other with respect to the jāti to which they belong. On the contrary, let us now consider the first jāti-bādhaka (‘blocker’ or ‘opposing agent of the universal’): vyakter abhedaḥ [bhedābhāva], “ ‘the oneness of the individual’ or ‘indivisibility of the individual’ [or ‘radical absence of any possible distinction’], that is when exists only one member of any category, an individual alone” (Pellegrini 2016, p. 79). For instance, according to the Nyāya analysis, kāla (time) or dik (space) are radically one and therefore, qua singular substances, they cannot have equivalents in the sense that a cow, with respect to another cow, can.

In the utterance vaidyam ānaya (‘Fetch a doctor!’), the implied meaning appears, reasonably enough, to be: mad-rogamukti-viśaya eka-kuśala-vaidyasya anya-kuśala-vaidyas tulyaḥ; atha kuśala-vaidyam ānaya (‘In order to heal my disease, a skilled physician is equivalent to another one, provided that he is a skilled physician as well; so, fetch one!’). So—for v : vaidya, a physician; vt : vaidyatva, the property being a physician; V: the set Physicians; and for (v, v′)∈V and |vt|=V—we could obtain the meaningful assertion: [8b] (v′.vt)⌝E⌞(v.vt), for v′≠v. However, [8c] (v′.vt)⌝E⌞(v′.vt), for v=v, that is, etat-kuśala-vaidyasya etat-kuśala-vaidyas tulyaḥ (‘This very physician is equivalent to this very physician’) is true either in the secondary and here pointless sense of an individual being equivalent to himself; or even, taken as a negation, with a completely opposite meaning. This last sentence, in fact, could be interpreted as etad-vaidyasya na kaścit tulyaḥ, tasya uttamattvāt: ‘This physician has no equivalent, because he is the best’ or *[8c-1] (v′.vt)⌝E⌞(v.vt), which is nevertheless a patent contradiction for (v, v′)∈(V=|vt|) (*=‘false’; cf. P1). The truth values thus suggest that the properties involved cannot be the same. Instead, for instance vt = ‘Being an average physician’, and v′t = ‘Being the finest physician’, with a significative change in the truth values: a) v′t ≠vt, (v′ ∈ |v′t|) ⊆ (v ∈|vt|); b) the domain of |vt| = V will be now greater than one (card(V) ≥ 2) if we assume that there exists at least one average doctor apart from the outstanding one; and c) the domain of |v′t| = V′ will necessarily be equal to one, because there is by definition only one utmost exemplar (card(V′) = 1; for the concept of cardinality of a set, cf. infra). In sum, two distinct elements a and b, both belonging to the generic set Z = |zt|, could be said to be equivalent to the generic property zt. This is impossible with respect to the two distinct properties zt and z′t, however, because x and y now no longer belong to the same reference domain; i.e. an average physician is not equivalent to the best physician. Moreover, a reflexive equivalence could be either true but trivial or paradoxically negative and highly context-sensitive, although still formally true—e.g. ‘This physician is only equivalent to himself, because he has no equivalent’.

Equivalence appears, in light of the above, to be closely linked to domain multiplicity. Yet what could multiplicity mean in this context? In modern times, Navya-Nyāya—and Raghunātha Śiromaṇi (c. 1510), in particular—moved beyond the theory of number as an inherent quality (guṇa) in “adjectival function” (Ganeri, 1996, p. 111), through the logically primitive relational concept of paryāpti-sambandha in the sense of ‘completion’.Footnote 7 This new conception “bears a close resemblance to the recent concept in Western logic of number as a class of classes” (Ingalls 1951, p. 76).Footnote 8 Framed in this way, number becomes an imposed property (upādhi) related by paryāpti to the set of objects being numbered: indeed, “paryāpti is the relation by which numbers reside in wholes rather than the particulars of wholes”, so that “the loci of two-ness and of three-ness are mutually exclusive” (Ingalls 1951, p. 77). In this manner, “a trio of men, for example, is an instance of number 3, and the number 3 is an instance of number; but the trio is not an instance of number […; because] a number is something that characterises certain collections, namely, those that have that number” (Russell 1919, pp. 11–12).Footnote 9 Thereby, numbers could be conceived as “n-fold relations of mutual distinction: ‘The planets are (at least) three’ is ‘logically equivalent’ to: (∃x) (∃y) (∃z) [Planet (x) & Planet (y) & Planet (z) & x≠y & y≠z & z≠x]”.Footnote 10 In a nutshell, the condition laid down by the NK definition of equivalence—bhinnatve sati—requires that the cardinality of the reference domain be greater than one (condition-a) and, therefore, not trivially reflexive (condition-b). Equivalence in a full sense thus only exists between two distinct elements of a given set, which in turn is the reference domain of that property to which these elements are declared equivalent.

For the limited purposes of this article, we are dealing exclusively with natural numbers (viz., not negative integers); I thus propose to express the paryāpti relation in NL through the natural numbers symbol (‘ℕ’), leaving the possibility of expanding the system open to further investigation.Footnote 11 Consequently, being ‘two’ linked to the property two-ness (dvitva, 2t; cf. NK, p. 381), the statement dvau gāvau (‘Two cows’) could be expressed in NL as:

[9] ((g, g′) . gt)⌝ ℕ ⌞2t

yat paryāptitvaṃ dvi-go-niṣṭha-gotvāvacchinnaṃ tad dvitva-nirūpitam; ‘The relational abstract completion-ness, conditioned by two-ness, is limited by cow-hood in two cows’.Footnote 12

Now, NK explicitly states that tulyatva means sharing a given property (dharma-vat-tva) in the context of a mutual distinction (bhinnatva). However, this very distinction cannot but imply multiplicity—as we have seen, an “n-fold relations of mutual distinction”. Therefore, equivalence can only be conceived as a relation the cardinality of which is strictly greater than one: card(E)>1.Footnote 13 Thus—being the condition ‘greater than one’ expressible as dvitvādi (‘two, etc.’, or ≥ 2t)—our first example concerning equivalence to gotva now begs a further truth condition which was previously solely implicit. This means that the reference domain must possess more than one element (i.e., there is more than one cow; condition-a); and that the relation involves two distinct elements of this multiple reference domain (g′≠g; i.e., we are talking about two different cows; condition-b). In NL:

[8a] ((g′. gt)⌝ E ⌞(g. gt))⌝ ℕ ⌞(≥ 2t)

yat paryāptitvaṃ go-niṣṭha-tulyatvāvacchinnaṃ tad dvitvādi-nirūpitam, etad eva tulyatvaṃ ca idaṃ-go-niṣṭha-gotvāvacchinnam adaḥ-go-niṣṭha-gotva-nirūpitaṃ ca; ‘Equivalence, conditioned by cow-ness in that cow, and limited by cow-ness in this cow, for card(E) ≥ 2’.Footnote 14

In general—being ‘Possessing a particular property’ expressible as taddharmavattva (tdt , cf. fn. 3)—the statement ‘Equivalence between the generic element a and b is a relation whose cardinality is strictly greater that one’ will now appear in NL as:

[10] (b . tdt⌝ E ⌞(a . tdt))⌝ ℕ ⌞(≥ 2t)

yat paryāptitvaṃ tulyatvāvacchinnaṃ tad dvitvādi-nirūpitam, etad eva tulyatvaṃ ca idam-niṣṭha-taddharmavattva-avacchinnam adaḥ-niṣṭha-taddharmavattva-nirūpitaṃ ca; ‘The relational abstract completion-ness, conditioned by two-ness, etc., is limited by equivalence, which is in turn conditioned by a particular property in a generic element, and limited by the same property occurring in another element’; iff (a ≠ b) ∧ ((a, b) ∈ |tdt|) ∧ card(E) ≥ 2.

The truth conditions and cardinality of a tulyatva relation undoubtedly show that this cannot, except in a secondary sense, concern the relation of non-difference (abheda). A gold crown is undeniably one and, in this sense, the crown (m) is non-different from the gold (h). This state of affairs has been provisionally expressed in P1 through the relation of sāmānādhikaraṇya (Ṇ): [2a] (h.ht)⌝Ṇ⌞(m.mt). In all evidence, the cardinality of [2a] is equal to one (there is but one crown) and thus incompatible with the requested cardinality of tulyatva expressed in [10]. Moreover—in violation of the definition of both tulyatva (cf. dharmavattva) and condition-a (cf. supra)—a well-formed equivalence formula cannot be provided, by substitution, starting from [2a]. The same properties do not appear on both sides of the equivalence relation, that is, the two relata do not belong to the same reference domain: *[2b] *(h.ht)⌝E⌞(m.mt), false because h ∈|ht| (an instance of gold belongs to the set Gold), but m ∈|mt| (a crown belongs to the set Crowns). So, hāṭakasya na mukuṭaṃ tulyam (‘A crown is not equivalent to gold’, 〈h, m〉 ∉E).

In a further countercheck, we could state that crown and gold are nonetheless equivalent: mukuṭasya hāṭakaṃ tulyam. What could be the meaning implied here? Firstly, that they are two. This immediately gives rise to a second question: with respect to what property? Uttered by a merchant, it could mean that they are equivalent to their value (mūlya) or their ‘purchasing power’ (krayaṇa): krayaṇāya hāṭaka-mukuṭa-bhūṣaṇasya piṇḍa-rūpa-hāṭakaṃ tulyam (‘For the purpose of purchasing, a golden accessory, such as a crown (m), is equivalent to raw forms of gold, such as a nugget (p)’). In this area NL precludes misinterpretations and reshapes (including visually: note the symmetry of properties on both sides of the equivalence; in this case: being gold) every possible hypothesis into a well-formed formula (in observance of conditions a & b):

[11] (m . ht)⌝ E ⌞(p . ht)

yad tulyatvaṃ mukuṭa-niṣṭha-hāṭakatva-avacchedakāvacchinnaṃ tad piṇḍa-niṣṭha-hāṭakatva-nirūpitam; ‘Equivalence, conditioned by gold-ness in a nugget, is limited by gold-ness in a crown’; iff ((m, p) ∈ |ht|) ∧ (m ≠ p) ∧ |(m.ht)| ⊆ |E⌞(p.ht)|, that is, 〈g, p〉 ∈ Eht.

It follows that there is at least a crown and a nugget, and that both of them are equivalent to the set to which they belong, defined by the property ‘gold-ness’: [11a] ((m.ht)⌝E⌞(p.ht))⌝ℕ⌞(≥2t), iff card(E) > 1. If this interpretation is in perfect compliance with the aforesaid equivalence conditions, in all evidence it again fails to match the non-difference truth conditions, the cardinality of which is strictly one (card([2a]) = 1). The same conclusion is reached for any property whatsoever. Is there any way to force ‘mukuṭasya hāṭakaṃ tulyam’ to be true without appealing to any further property? Only against the ‘condition-b’, that is, in the reflexive form of equivalence with cardinality equal to one: [12] (m.ht)⌝E⌞(m.ht), iff m = m, that is, just as with the derivate form we saw to be either pointless—lacking in any informative value—or directly contradicting the relation itself: anuttara-hāṭaka-mukuṭaḥ, ‘An unparalleled gold crown’.

Equality

“Equality gives rise to challenging questions which are not altogether easy to answer. Is it a relation? A relation between objects, or between names or signs of objects? In [his] Begriffsschrift [Frege] assumed the latter”, and here I do as well.Footnote 15 According to NK, the relation of equality (samaniyatatva)Footnote 16 consists in a mutual pervasion or invariable concomitance (vyāpti) in which the pervaded (vyāpyatva) is also the pervader (vyāpakatva): vyāpyatve sati vyāpakatvam.Footnote 17 NK advances the classical example concerning cow-hood (gotva) and possessing dewlap, etc. (sāsnādimattva): these properties must be said to be equal since every instance of the former is an instance of the latter, and vice versa, and because—according to the Axiom of Extensionality (AE)—if two sets have exactly the same members then they are equal.Footnote 18 The very concept is expressed in NK sub voce ‘tulyatva2ka-kha’: anyūnānatirikta-vyaktikatvam, “x is equal to y when x has all the manifestations (vyakti) of and no other manifestation than y” (Ingalls 1951, p. 67); as in the case of ghaṭatva and kalaśatva, both translatable as pot-ness and whose manifestations are nothing but pots; or as in the further case of buddhitva (intellection) and jñānatva (cognition).Footnote 19Tulyatva2ka-kha is explicitly mentioned by NK as a ‘blocker’ (bādhaka) impeding the establishment of distinct general properties; it follows that the same individual manifestations (vyakti) cannot but point to the very same jāti, even if they are expressed with different terms. “[Vyakter] tulyatvam, the sameness [of the individual]” operates as a blocker; therefore, “the substrate (adhikaraṇa) of the first property is nothing but the substrate of the second one, and viceversa”.Footnote 20 More precisely: tulyatvaṃ ca na jātibādhakam | kintu jātibhedabādhakam; “sameness [of the individuals] is not an universal blocker, but a blocker of the difference between universals”, which are thus, stricto sensu, equal.Footnote 21 What follows (phalita) is the very same extension (samaniyatatva) of properties which differ only linguistically.

If samaniyatatva and tulyatva2ka-kha define the relation of equality between distinct expressions both of which can refer to the same property, then: iyaṃ gau iti iyaṃ sāsnāmatī iti vā, samaniyatatvāt (‘This cow or this [animal] possessing dewlap, by virtue of equality’) or ghaṭatvakalaśatvayos tulyatvam (‘Pot-ness is equal to pitcher-ness’). Equality expresses an identity of reference (vācya or artha) between distinct signs and expressions (vācaka or pada). Samaniyatatvaṃ vāgālambanaṃ nāmādheyaṃ vā: equality is a matter of words; it is a mere verbal difference regarding names or denominations. Thus, there is equality between signs and expressions, but identity regarding the object. In Frege’s words: “Equality. I use this word in the sense of identity and understand ‘a = b’ to have the sense of ‘a is the same as b’ or ‘a and b coincide’ ” (Frege 1966, p. 56, fn. *). Along the same lines, Quine opportunely notes that “confusion and controversy have resulted from the failure to distinguish clearly between object and its name. […] The trouble comes […] in forgetting that a statement about an object must contain a name of the object rather than the object itself” (Quine 1981, p. 24). It is thus necessary to plainly distinguish between “Use versus Mention” (Quine 1981: §4, pp. 23–26; cf. also 1987, pp. 231–235). “The name of a name or other expression is commonly formed by putting the named expression in single quotation marks […]. We mention x by using a name of x; and a statement about x [inescapably] contains a name of x” (Quine 1981, p. 23). In this sense, in defining the relation of identity as x = y iff (z=x) ↔φ (z=y), Quine himself makes use of three different names for the object under examination—while ‘the object under examination’ constitutes a fourth expression. Only the names of x (i.e., its mentions) are distinct, however, because: ‘x’ ≠ ‘y’ ≠ ‘z’ ≠ ‘the object under examination’ (all in single quotation marks); while the use of the names, stricto sensu, allows the affirmation that x = y = z = the object under examination (all without single quotation marks).Footnote 22

Words—variously: pada, śabda, vācaka, or nāman—are said to possess a peculiar primary referential power (śakti; together with its related abstract, śakyatā) by virtue of which they stand solely for certain defined entities (sattva) or meaning-relata (artha, vādya or vācya) and not others. The issue is particularly complex and surely beyond the scope of this paper; yet, roughly speaking, the pada ‘go’ refers to its artha—the animal called ‘cow’—and not to a chair precisely because of that śakti: the power to point at the specific quality which distinguishes cows from chairs, that is, the pravṛtti-nimitta, the basis or grounds for using that term and not another.Footnote 23 In this sense, two different expressions in possession of the very same grounds for use (pravṛtti-nimitta) could be said to be equal: vaṭavṛkṣa = nyagrodhapādapa because their primary referential power (śakti) points at the very same referent or artha (i.e., in a third expression, ficus benghalensis). In other terms, I assume that equality, in its proper sense, concerns first and foremost the padapadārtha-sambandha. Samaniyatatva must be conceived as a matter of śakyatā because it provides information about the use of the names of x (viz. about ‘x’, or about its mentions)—while establishing relations of co-extensionality, co-reference or synonymity (samabhivyāhāra; cf. NK, p. 957) between expressions.Footnote 24 Consequently, I suggest that identity, stricto sensu, must concern the referent in question and not its names—being a statement about x and not about ‘x’ (cf. infra, § 7.).

Let us now analyse the NK example in NL involving the non-symmetric relation of invariable concomitance or pervasion (vyāpti) (cf. Anrò, forthcoming §4.4-5). Let samaniyatatva the relational abstract of equality (Q); gotva (gt) the property cow-hood relative to the set Cows (|gt|=G); and sāsnāmattva (st) the property possessing-dewlap referred to the set Living beings possessing-dewlap (|st|=S).Footnote 25 The equality of expressions and the identity of their reference could thus be conveyed as:

[13] ((gt⌝ Q ⌞st) ∧ (st⌝ Q ⌞gt)) ↔ ((gt⌝ Ṇ ⌞st) ∧ (st⌝ Ṇ ⌞gt))

yadi sāsnāmattvaṃ gotvaṃ vyāpnoti evaṃ gotvaṃ sāsnāmattvaṃ vyāpnoti, tarhi sāsnāmattvagotve samaniyate ; ‘If cow-ness pervades possessing-dewlap-ness and possessing-dewlap-ness pervades cow-ness, then cow-ness and possessing-dewlap-ness are equal’. Or, in full expression: yadi yad vyāptitvaṃ gotva-avacchinnaṃ tat sāsnāmattva-nirūpitam evam yat vyāptitvaṃ sāsnāmattva-avacchinnaṃ tad gotva-nirūpitam, tarhi yad yat samaniyatatvaṃ gotva-avacchinnam tat tat sāsnāmattva-nirūpitam, athavā yad yat samaniyatatvaṃ sāsnāmattva-avacchinnaṃ tat tad gotva-nirūpitam.

NL calls for a further operator here to express a symmetrical—that is, reversible—relation. For this purpose, be introduced the symbol ‘⇌’ in the straightforward meaning of: tadviparyayeṇa (‘vice versa’, hereafter ‘&vv’).Footnote 26 Consequently, [13] will now turn into:

[14] (gt ⇌ Q ⌞st) ↔ (gt ⇌ Ṇ ⌞st)

yadi sāsnāmattvaṃ gotvaṃ vyāpnoti tadviparyayeṇa ca, tarhi ete samaniyate; ‘If the property cow-ness pervades the property possessing dewlap, &vv, then these properties are equal’. Iff (G ⊆ S) ∧ (S ⊆ G) ∴ (G = S).

With [14] we have definitely clarified that gt and st have the same extension. Consequently—lest they not mean what they mean—they are in possession of the same ground of use (pravṛttinimitta), which is the limitor of their property of primary meaningfulness (śakyatā, Ś).

[15] ‘g’⌝ Ś ⌞gt

yā śakyatā go-pada-avacchinnā sā gotva-nirūpitā, ‘The primary meaningfulness is limited by the term cow, while conditioned by cow-ness’. Iff |‘g’| = g ∈(|gt|=G), where single brackets in formulas such as [15] do mean the word (pada) x; thereby, ‘The extension of the word ‘cow’ is a cow, qua instance of cow-ness and belonging to the set Cows’. Analogously, for ‘sāsnāmat’: ‘s’⌝Ś⌞st, for |‘s’| = s ∈(|st|=S).

However, in [14]: (G = S), and in [15]: (|‘g’| = (g∈G)) ∧ (|‘s’| = (s∈S)) ∴ (|‘g’| = |‘s’|). Therefore, we can conclude that equality relation—as padapadārtha (or vācyavācaka) sambandha and with respect to the terms ‘go’ and ‘sāsnāmat’ (sāsnādimat)—might be fully interpreted as:

[16] (‘g’⌝Ś⌞gt) ⇌ Q⌞ (‘s’⌝Ś⌞st)

yad samaniyatatvaṃ go-pada-avacchinna-gotva-nirūpita-śakyatā-avacchedaka-avacchinnaṃ tat sāsnāmad-pada-avacchinna-sāsnāmattva-nirūpita-śakyatā-nirūpitam, tadviparyayeṇa ca; ‘Equality, conditioned by primary meaningfulness described by the property possessing dewlap and limited by the expression ‘possessing dewlap’, is limited by primary meaningfulness described by the property cow-hood and limited by the word ‘cow’, &vv’.

In light of the above, the cardinality of the relation of equality will be greater than or equal to one (card(Q) ≥1). Firstly, because of the intrinsic plurality of manifestations of a general term (cf. supra). Secondarily, because a term could clearly refer to a singular, as in cases such as ‘dik’ (‘space’, cf. § 1) or in sentences such as ‘ayodhyā-kumāro rāmaḥ’.Footnote 27 It follows that, being the condition ≥ 1 expressed as ekatvādi (≥1t, lit., ‘oneness, etc.’), the equality between ‘gotva’ and ‘sāsnāmattva’ needs its cardinality truth condition to be made explicit, that is: [16a] ((‘g’⌝Ś⌞gt)⇌Q⌞(‘s’⌝Ś⌞st))⌝ℕ⌞(≥1t), for (card Q) ≥1. In more general terms, the equality between this (etat; ‘a’) and that (tat; ‘b’) generic expression—in relation to their common grounds of use (pravṛttinimitta), expressed by the same generic property (taddharmavattva, tdt; cf. fn. 3)—as a symmetric relation whose cardinality is greater than or equal to one, will now appear in NL as:

[17a] (‘a’⌝Ś⌞tdt) ⇌ Q⌞ (‘b’⌝Ś⌞tdt))⌝ℕ⌞(≥1t)

yat paryāptitvaṃ samaniyatatva-avacchinnaṃ tad ekatvādi-nirūpitam; etad eva samaniyatatvaṃ etat-pada-avacchinna-taddharmavattva-nirūpita-śakyatā-avacchedakāvacchinnaṃ tad-pada-avacchinna-taddharmavattva-nirūpita-śakyatā-nirūpitaṃ, tadviparyayeṇa ca; ‘Equality, conditioned by primary meaningfulness described by a particular property and limited by that linguistic expression, is limited by primary meaningfulness described by the same property and limited by this linguistic expression, &vv, for card(Q) ≥ 1’.

Identity

“Identity, we will say, is the relation that each thing has to itself and nothing else. […] The concept of identity is so basic to our conceptual scheme that it is hopeless to attempt to analyse it in terms of more basic concepts” (Hawthorne 2003, p. 99). The problem is that, “roughly speaking, to say of two things that they are identical is nonsense, and to say of one thing that it is identical with itself is to say nothing at all”.Footnote 28 A first move in the attempt to figure out this puzzle could be recognising that “a thing is identical with itself and with nothing else”, however obvious it may sound; consequently, to admit that “the identity relation comprises all and only the repetitious pairs, 〈x, x〉”; nevertheless, and this is the key point, “〈x, x〉 is still not to be confused with x” (Quine 1987, pp. 89–90). Along exactly the same lines, NK defines the relation of identity—sub voce ‘tādātmya2’—as referring to a singularity (aikya) that cannot but be declared identical to itself precisely because it is that very singularity.Footnote 29 Vācaspati Miśra (VM) likewise seems to accept this definition of identity: in negative terms, where there is not difference there is unit or singularity (ekatva): na cet, ekatvam evāsti, na ca bhedaḥ (cf. fn. 49 and P1). Similarly, tādātmya1kha suggests that identity could also be conceived as an idiosyncratic feature (dharma) by virtue of being ‘not-common’ (asādhāraṇa) and ‘self-referring’ (svavṛtti); thus, radically singular (ekamātra).Footnote 30 This idiosyncratic feature has individuality (vyaktitva) as its form (rūpa). Thereby, in case of a blue pot, identity—grammatically expressed through the notion of sāmānādhikaraṇya—is precisely that particular individuality in (niṣṭha) that very pot.Footnote 31 In this sense, identity could thus be defined as a relation the cardinality of which is strictly equal to one.Footnote 32 Obviously, I am not arguing here that the concept of unit completely parallels that of identity. Rather, I propose that identity is usefully describable through the cardinality one of the ordered couple it consists of; consequently, cardinality one must compose the definition of identity as a decisive factor.

Bhāsarvajña (c. 950)Footnote 33 maintains that numbers stand for relations of identity (abheda) and difference (bheda). “Identity and difference depend on sameness [svātmāpekṣā] and distinctness [parātmāpekṣā] in colour and so on, and so are not considered to be qualities [guṇa]. Further, it is a tautology [paryāya] to say ‘the one is identical’ [ekam abhinnam] or ‘the many are different’ [anekaṃ bhinnam]”.Footnote 34 “The statement ‘a and b are one’ is synonymous with ‘a = b’. […] On the other hand, the statement ‘a and b are two’ asserts that a ≠ b. […] Indeed, it is now standard to formalise sentences of the form ‘there are n Fs’ by means of non-identity’ […]” (Ganeri 2001, p. 418). In short, “number is but another name for diversity. Exact identity is unity, and with difference arises plurality”Footnote 35.

If x and y are meant as identical, “the intended sense [is that] ‘x and y are the same object’” (Quine 1981, p. 134). Therefore, being that very object, x and y are one. However, we have already seen that the definition of identity, according to Quine, likely sounds like: ‘x is y iff x is z and z is y’. Apparently, defining or even simply talking about identity—which is oneness—necessarily implies a panoply of multiple symbols and expressions; that is, any discourse about the identity of x makes use of the relation of equality between the different names for x—for instance, x is y; then x is y via z, etc. And yet, what about the relation between x and z, used as a medium between x and y? Multiplicity and the proliferation of names and relations are therefore paradoxically introduced where there was nothing but oneness.

To express the difficulties language encounters in dealing with identity—a structurally binary relation, by virtue of the very fact of being a relation, although radically converging on one—what could come to our aid is Frege’s premise about the problem of unit, as expressed in the context of his scrutiny of unit as the building-block of numbers and as the alleged result of abstraction (my glosses about identity appear in square brackets): “If we try to produce the number by putting together different distinct objects [or, in our case, to express identity from the combination of distinct expressions; e.g. ‘Scott = author of Waverley’], the result is an agglomeration in which the objects contained remain still in possession of precisely those properties which serve to distinguish them from one another [and, similarly, we obtain but an agglomeration once again comprising exactly those properties that differentiate the distinct expressions we used: ‘Scott’ and ‘author of Waverley’]; and this is not a number [or identity]. But if we try to do it in the other way, by putting together identicals [or, in our case, if we reaffirm the identity by a combination of identical expressions; e.g. Scott = Scott], the result runs perpetually together into one and we never reach a plurality [or, this constantly coalesces into trivial tautology, and we never achieve any informative expression]. […] The word ‘unit’ is admirably adapted to conceal this difficulty [and so is the term ‘identity’]”.Footnote 36

How, then, to solve this conundrum? A negative, counterfactual, formulation could be attempted. Be ‘∄’ the relation of ‘constant or absolute absence’ (atyantābhāva), ‘constant absence-hood’ (atyantābhāvatva; ∄) its relational abstract, and ‘constant absentee-hood’ (atyantābhāvīya-pratiyogitā; ∄−1) the inverse of this latter—where, in general: (∄⌞v) = (v⌝∄−1).Footnote 37 Consequently, the traditional example bhūtale ghaṭo na (‘There is no pot on the ground’) can be expressed in NL as:

[18] gt⌝∄−1⌞(L−1⌞b)

yā atyantābhāvīya-pratiyogitā ghaṭatvāvacchinnā sā ādheyatā-nirūpitā, saiva ādheyatā bhūtala-nirūpitā; ‘The constant absentee-hood, with respect to the property being over (L−1) a ground (b), is limited by pot-ness (gt)’; iff |gt|∩|L−1⌞b| = ∅ (‘The intersection of the set Pots and the set Superstrata of a certain ground is empty’); in s.n. (∃x, ∀y | Bx, Gy) (〈x, y〉 ∉ L).

Let us now use the same approach to analyse a second classical assertion: ghaṭaḥ paṭo na (‘A pot is not a cloth’). To avoid any confusion with the relation of equality, concerning expressions, I will introduce here a specific notation for identity (I) and its negation (

), absolutely abandoning the equality-identity overlap and radically embracing the account according to which “Nyāya conceives of identity as obtaining between objects, not between symbols” (Matilal 1968, p. 46). So, let anyonyābhāva (

), absolutely abandoning the equality-identity overlap and radically embracing the account according to which “Nyāya conceives of identity as obtaining between objects, not between symbols” (Matilal 1968, p. 46). So, let anyonyābhāva (

) be the symmetrical relation of mutual absence; anyonyābhāvatva (

) be the symmetrical relation of mutual absence; anyonyābhāvatva (

) its relational abstract, i.e. the mutual absent-hood; and anyonyābhāvīya-pratiyogitā (

) its relational abstract, i.e. the mutual absent-hood; and anyonyābhāvīya-pratiyogitā (

) the converse of the latter, i.e. mutual absentee-hood. Accordingly, ghaṭaḥ paṭo na will turn into:

) the converse of the latter, i.e. mutual absentee-hood. Accordingly, ghaṭaḥ paṭo na will turn into:

[19] p ⇌

⌞g

yā anyonyābhāvīya-pratiyogitā paṭa-niṣṭhā sā ghaṭa-nirūpitā, tadviparyayeṇa ca; ‘Mutual absentee-hood, conditioned by a pot, is limited by a cloth, &vv’; iff (g ∈ G) ∧ (p ∈ P) ∧ (G∩P = ∅).

The relation of difference or mutual absence can easily be transformed into a ‘negation of identity between the relata’: anuyogi-pratiyogi-tādātmya-pratiṣedha. Thus, for the same truth conditions, [19] can be rephrased in: [20] ∄(p ⇌

⌞g), where the identity relation (I) between g and p is said to be absent. In accordance with [18], it could be stated that:

⌞g), where the identity relation (I) between g and p is said to be absent. In accordance with [18], it could be stated that:

[21] p ⇌ ∄−1⌞(

⌞g)

yā paṭa-niṣṭha-atyantābhāvīya-pratiyogitā sā tādātmyatā-nirūpitā, saiva tādātmyatā ghaṭa-nirūpitā, tadviparyayeṇa ca; ‘Constant absentee-hood, limited by a cloth, is conditioned by mutual absentee-hood, in turn conditioned by a pot, &vv’; iff (G ∩ P = ∅).

Keeping in mind the elements laid out in these introductory examples, let us now move to the analysis of the counterfactual definition of identity. As mentioned above, identity is defined in terms of oneness.Footnote 38 Now, Gadādhara (c. 1650) maintains that “the meaning of ‘one F’ [eka-śabda] is: an F qualified by being-alone [kaivalya; i.e. ‘being a unit’], where ‘being-alone’ [or ‘being a unit’] means ‘not being the counterpositive of a difference resident in something of the same kind’ [svasajātīya]”.Footnote 39 This ‘uniqueness’ (kaivalya), Gadādhara overtly states, radically excludes multiplicity: kaivalya in the meaning of svasajātīya-dvitīya-rāhitya, ‘being devoid of a second one of the same kind’. If a second one of the same kind were presumed here, the postulated relation would collapse into equivalence—as in the case of two manifestations of the same property. Therefore, the expression “ ‘one F’ is to be analysed as saying of something which is F that no F is different to it. If this is paraphrased in a first order language as Fx & ¬(∃y) (Fy & y≠x), then it is formally equivalent to a Russellian uniqueness clause: Fx & (∀y) (Fy → y = x)” (Ganeri 2001, p. 419). In other words, “to deny that an object a is numerically different from an object b is tantamount to saying that a is identical with b” (Matilal 1968, p. 46; cf. also, NK, p. 186, ekatva).

Let us proceed step by step. The definition opens by claiming that this ‘unit’ is the pratiyogin of a relation of difference (bheda). Accordingly, a single pot g, e.g., must appear in the pratiyogin position with respect to difference or mutual absence relation (bheda = anyonyābhāva,

; and therefore as anuyogin in

; and therefore as anuyogin in

), just as in the assertion paṭo ghaṭo na: g·

), just as in the assertion paṭo ghaṭo na: g·

⌞p (‘A cloth is not a pot’).Footnote 40

⌞p (‘A cloth is not a pot’).Footnote 40

Now, this difference could be said to momentarily occur (niṣṭha) in ‘Something which is the same’ (svasajātīya): let us call it g′. Consequently: *(g.

⌞g′), *‘Something which is the same is different from this (e.g., a pot)’. As the third step, this relation is subsequently negated; because the object under examination must not be the pratiyogin of such a relation: “a-pratiyogin”, the text states. Thus: ∄(g.

⌞g′), *‘Something which is the same is different from this (e.g., a pot)’. As the third step, this relation is subsequently negated; because the object under examination must not be the pratiyogin of such a relation: “a-pratiyogin”, the text states. Thus: ∄(g.

⌞g′). In light of the above examples, this last assertion can easily be transformed into:

⌞g′). In light of the above examples, this last assertion can easily be transformed into:

[22] g ⇌ ∄−1 ⌞ (

⌞ g′)

yā ghaṭa-niṣṭhā-atyantābhāvīya-pratiyogitā sā anyonyābhāvīya-pratiyogitā-nirūpitā, saiva anyonyābhāvīya-pratiyogitā svasajātīya-ghaṭa-nirūpitā, tadviparyayeṇa ca; (t)‘This pot is the limitor of the constant absence of the mutual absence with respect to something which is the same, &vv’.

This assertion is true iff g ∉ |

⌞g′|, because the constant absence (atyantābhāva, ∄) of g occurs in |

⌞g′|, because the constant absence (atyantābhāva, ∄) of g occurs in |

⌞g′|. And yet |

⌞g′|. And yet |

⌞g′| = \(\mathrm{\overline{G}}^{\prime}\), i.e. the set Everything which is not g′, in which G′ is a singleton containing g′ solely: i.e. G′ = {g′}. Therefore, if g ∉ \(\mathrm{\overline{G}}^{\prime}\), then g ∈ G′; but G′ = {g′}, so: g = g′ or, better, 〈g, g′〉 ∈ I (i.e. the two linguistically different expressions ‘g’ and ‘g′’ refer to the very same singular extension). In other words, if g does not belong to the set Everything which is not g′ (i.e. \(\mathrm{\overline{G}}^{\prime}\)), then g cannot but belong to G′; however, G′ is a singleton whose unique element is g′. Thereby, g and g′ are one and the same. In brief: g = g′, even if ‘g’ ≠ ‘g′’ (name vs. mention); 〈g, g′〉 ∈I; and (g, g′) ∈G′ (as imposed by the definition: svasajātīya) for card(G′)=1. So: ghaṭo aneko na bhāsate, ghaṭaikatvāt, ‘No pot-multiplicity appears, because there is but one pot’. That is, ghaṭa-svasajātīya-ghaṭayos tādātmyam, ‘Identity between this pot and what is the same thing as this pot’, because these two expressions point to the very same pot. Therefore, if [22], then:

⌞g′| = \(\mathrm{\overline{G}}^{\prime}\), i.e. the set Everything which is not g′, in which G′ is a singleton containing g′ solely: i.e. G′ = {g′}. Therefore, if g ∉ \(\mathrm{\overline{G}}^{\prime}\), then g ∈ G′; but G′ = {g′}, so: g = g′ or, better, 〈g, g′〉 ∈ I (i.e. the two linguistically different expressions ‘g’ and ‘g′’ refer to the very same singular extension). In other words, if g does not belong to the set Everything which is not g′ (i.e. \(\mathrm{\overline{G}}^{\prime}\)), then g cannot but belong to G′; however, G′ is a singleton whose unique element is g′. Thereby, g and g′ are one and the same. In brief: g = g′, even if ‘g’ ≠ ‘g′’ (name vs. mention); 〈g, g′〉 ∈I; and (g, g′) ∈G′ (as imposed by the definition: svasajātīya) for card(G′)=1. So: ghaṭo aneko na bhāsate, ghaṭaikatvāt, ‘No pot-multiplicity appears, because there is but one pot’. That is, ghaṭa-svasajātīya-ghaṭayos tādātmyam, ‘Identity between this pot and what is the same thing as this pot’, because these two expressions point to the very same pot. Therefore, if [22], then:

[23] (g ⇌ I ⌞g′)⌝ℕ⌞(1t)

yat tādātmyatā-avacchedaka-avacchinna-paryāptitvaṃ tad ekatva-nirūpitam, ghaṭa-kaivalyād; saiva ghaṭa-niṣṭhā-tādātmyatā svasajātīya-ghaṭa-nirūpitā, tadviparyayeṇa ca; (t)‘Pot′ is identical to pot, &vv, for card(I) = 1’; iff (〈g, g′〉 ∈ I).Footnote 41

The question potentially remains, why must the cardinality necessarily be equal to one? Firstly, for textual reasons: because Gadādhara himself imposes this condition when discussing the meaning of ‘the term one’ (ekaśabda). Secondly, for logical reasons. Indeed, what if the above analysis (cf. [21]–[23]) were repeated in terms of general properties, e.g. pot-ness (gt)? The result would then be:

[24] gt ⇌ ∄−1 ⌞(

⌞gt′)

yā ghaṭatvāvacchinna-atyantābhāvīya-pratiyogitā sā anyonyābhāvīya-pratiyogitā-nirūpitā, saiva anyonyābhāvīya-pratiyogitā svasajātīya-ghaṭatva-nirūpitā, tadviparyayeṇa ca; whose purport is: (t)‘Pot-ness (gt) identical to pot-ness′ (gt′), &vv’.

Formula [24] is true iff (|gt| = G) ∧ (|gt′| = G′) ∧ (|gt|∩|

⌞g′t| = ∅); but, |

⌞g′t| = ∅); but, |

⌞gt′| = \(\mathrm{\overline{G}}^{\prime}\); therefore, G∩\(\mathrm{\overline{G}}^{\prime}\) = ∅. It follows that 〈‘gt’, ‘gt′’〉∈Q and 〈G, G′〉∈I, i.e. the expression ‘pot-ness’ is equal to the expression ‘pot-ness′’ and the set Pot-ness is identical to the set Pot-ness′ because they are the very same set (AE; cf. fn. 18). Now, if we chose to distinguish gt and gt′ call them ghaṭatva and kalaśatva, from a linguistic perspective the application of Gadādhara’s definition to a general property such as gt collapses significantly into equality (Q; cf. § 2). If, on the contrary, the same name, say ghaṭatva, were retained, this would be just a reflexive case of equality. If equality primarily concerns different names with the same reference, identity should first and foremost concern reference and not its names, otherwise the one would collapse into the other. What could identity mean with regards to a set, if it is not a matter of names? Once again, the key is to think in terms of relations on the Cartesian plane. What is at stake here is the set of ordered couples belonging to the relation 〈G, G〉∈I (i.e. G×G according to relation I), in which every single element of G (g1, g2, …, gn) stands in relation I to itself: 〈gn, gn〉∈I. In other words, the extensional interpretation of identity, with respect to a general property such as ghaṭatva (gt), turns out to be the set of the ordered couples stating the identity of all the elements of the dominion with themselves. It goes without saying that each of these couples clearly has a cardinality equal to one, as expressed in [23].

⌞gt′| = \(\mathrm{\overline{G}}^{\prime}\); therefore, G∩\(\mathrm{\overline{G}}^{\prime}\) = ∅. It follows that 〈‘gt’, ‘gt′’〉∈Q and 〈G, G′〉∈I, i.e. the expression ‘pot-ness’ is equal to the expression ‘pot-ness′’ and the set Pot-ness is identical to the set Pot-ness′ because they are the very same set (AE; cf. fn. 18). Now, if we chose to distinguish gt and gt′ call them ghaṭatva and kalaśatva, from a linguistic perspective the application of Gadādhara’s definition to a general property such as gt collapses significantly into equality (Q; cf. § 2). If, on the contrary, the same name, say ghaṭatva, were retained, this would be just a reflexive case of equality. If equality primarily concerns different names with the same reference, identity should first and foremost concern reference and not its names, otherwise the one would collapse into the other. What could identity mean with regards to a set, if it is not a matter of names? Once again, the key is to think in terms of relations on the Cartesian plane. What is at stake here is the set of ordered couples belonging to the relation 〈G, G〉∈I (i.e. G×G according to relation I), in which every single element of G (g1, g2, …, gn) stands in relation I to itself: 〈gn, gn〉∈I. In other words, the extensional interpretation of identity, with respect to a general property such as ghaṭatva (gt), turns out to be the set of the ordered couples stating the identity of all the elements of the dominion with themselves. It goes without saying that each of these couples clearly has a cardinality equal to one, as expressed in [23].

The cases of dik and Rāma have already been discussed in § 2: ‘dik’ ≠ ‘ākāśa’ ≠ ‘vyoman’, and ‘Rāma’ ≠ ‘ayodhyā-kumāra’, are meant as different names (nāman, śabda, or pada) for the same reference, the space and the hero called Rāma. In light of § 3, it is now clear that from a linguistic point of view (śabdataḥ), referring to the same artha (object or reference), the name ‘dik’ is said to be equal to ‘ākāśa’ and ‘Rāma’ to ‘ayodhyā-kumāra’; however, from an extensional point of view (arthataḥ) there is nothing but space, or nothing but Rāma. Thereby, arthataḥ, and starting from the assertion rāmo ’yodhyā-kumāro naiti na (‘It is false that Rāma is not the prince of Ayodhyā’):

[25] ((ayodhyā-kumāra) ⇌ ∄−1 ⌞(

⌞(Rāma)))⌝ℕ⌞(1t)

yad atyantābhāvīya-pratiyogitā-avacchedakāvacchinna-paryāptitvaṃ tad ekatva-nirūpitam, saiva ayodhyā-kumāra-niṣṭha-atyantābhāvīya-pratiyogitā anyonyābhāvīya-pratiyogitā-nirūpitā, saiva anyonyābhāvīya-pratiyogitā rāma-nirūpitā, tadviparyayeṇa ca; (t)‘The prince of Ayodhyā is not the counterpositive of a difference occurring in Rāma, &vv; for card=1’.

That is, rāmo ’yodhyā-kumāraḥ in the meaning of rāmāyodhyā-kumārayos tādātmyam (‘Rāma is identical to the prince of Ayodhyā’), because: 〈Rāma, ayodhyā-kumāra〉∈I, or 〈Rāma, Rāma〉∈I, or 〈ayodhyā-kumāra, ayodhyā-kumāra〉∈I, and card(I) radically equal to one. In parallel, śabdataḥ (cf. supra [17]):

[26] (‘Rāma’⌝Ś⌞etatpuruṣa) ⇌ Q⌞ (‘ayodhyā-kumāra’⌝Ś⌞etatpuruṣa))⌝ℕ⌞(≥1t)

yat samaniyatatva-avacchedakāvacchinna-paryāptitvaṃ tad ekatvādi-nirūpitam, tatra yad eva rāma-pada-avacchinna-etatpuruṣa-nirūpita-śakyatā-avacchedakāvacchinna-samaniyatatvaṃ tat ayodhyā-kumāra-pada-avacchinna-śakyatā-nirūpitaṃ, eṣaiva śakyatā etattva-avacchinna-etatpuruṣa-nirūpitā, tadviparyayeṇa ca. Whose purport is: (t)‘Two distinct verbal expressions—‘Rāma’ and ‘prince of Ayodhyā’—referring to the very same individual (card(Qsub[26])=1)’.

In conclusion, the constant counterpositive-ness (atyantābhāvīya-pratiyogitā) of identity (tādātmya) has proved to be mutual absence (anyonyābhāva) or diversity (bheda). Conversely, the constant counterpositive-ness of mutual absence is nothing but identity.Footnote 42 What has been obtained in this section is thus a counterfactual redefinition of identity in terms of oneness, mutual exclusion and constant absence; or, from a purely extensional perspective, its redefinition in terms of membership relation, complement and the cardinality of a set.Footnote 43

Interpreting Non-difference

VM has openly stated that the relation of non-difference (abheda, abhinna;

) is linguistically expressible in terms of sāmānādhikaraṇya (Ṇ), syntactical homogeneity or coreferentiality (cf. P1). Yet, how to interpret in detail this relation? Could non-different relata be also said at once equivalent, equal, or identical? In the light of previous paragraphs, it will be argued that none of these interpretations is viable.

) is linguistically expressible in terms of sāmānādhikaraṇya (Ṇ), syntactical homogeneity or coreferentiality (cf. P1). Yet, how to interpret in detail this relation? Could non-different relata be also said at once equivalent, equal, or identical? In the light of previous paragraphs, it will be argued that none of these interpretations is viable.

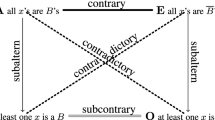

Interpreting a given relation means here to explore when this is true with respect to other relations. In this sense, if two relations are at once true, in every possible cases, they are one and the same, as e.g. syntactical homogeneity and coreferentiality are: (∀x) (〈x, y〉∈R ∧ 〈x, y〉∈R′) → (R=R′). In parallel, two relations are completely distinct if they never are simultaneously true: (∀x) (〈x, y〉∈R ∧ 〈x, y〉∉R′) → (R≠R′). If a relation is always true when a second one is true, but not vice versa, the former is included in the latter: if (∀x) (〈x, y〉∈R′ → 〈x, y〉∈R) ∧ (∃x) (〈x, y〉∈R ∧ 〈x, y〉∉R′), then R′ ⊆ R. In a fourth case, two relations could share some common pairs and, in this sense, they could be said just ‘resembling’ (≅): (∃x) (〈x, y〉∈R ∧ 〈x, y〉∈R′) ∧ (∃x′) (〈x′, y〉∈R ∧ 〈x′, y〉∉R′) → (R ≅ R′); or R ∩ R′ ≠ ∅.Footnote 44

Let us consider again the case of a golden crown. In [3] h.ht⌝V(Ṇ)⌞m.mt (ruled by SVN, Samānādhikaraṇa-Viśiṣṭatva-Nyāya or ‘Principle of Coreferential Qualification’; cf. P1), it has been shown that every case of coreference (Ṇ) can properly be interpreted in terms of qualification (viśeṣya-viśeṣaṇa-saṃsarga, V). Moreover, assertions [2]–[3] can stand as proper interpretations of mukuṭa-hāṭakayor abhedaḥ (‘Non-difference between crown and gold’), because ostensibly: (

) ⊆ (Ṇ) ⊆ (V).Footnote 45

) ⊆ (Ṇ) ⊆ (V).Footnote 45

[27] h .

⌞m

yā abhinnatā hāṭaka-niṣṭhā sā mukuṭa-nirūpitā & yā abhinnatā hāṭaka-niṣṭha-hāṭakatvāvacchinnā sā mukuṭa-niṣṭha-mukuṭatva-nirūpitā; ‘Non-difference-ness in gold, conditioned by a crown’. Iff 〈m, h〉∈

∧ 〈m, h〉∈Ṇ ∧ 〈m, h〉∈V.

In assertions *[2b] and [11]–[12] (cf. §2), it has already been shown that [2]–[3]—and consequently [27]—cannot be interpreted as instances of equivalence on the model of [10]. Neither could they be interpreted as instances of equality on the model of [17]: *[17a] *((‘m’⌝Ś⌞mt)⇌Q⌞(‘h’⌝Ś⌞ht))⌝ℕ⌞(≥1t), which is false because: (|ht|⊈|mt|) ∧ (|mt|⊈|ht|), therefore G≠M. It follows that only its negation can be true, i.e.:

[28] ((‘m’⌝Ś⌞mt) ⇌ ∄−1 ⌞(Q ⌞(‘h’⌝Ś⌞ht)))⌝ℕ⌞(≥1t)

yad atyantābhāvīya-pratiyogitā-avacchedakāvacchinna-paryāptitvaṃ tad ekatvādi-nirūpitam, tatra yā mukuṭa-pada-avacchinna-mukuṭatva-nirūpita-śakyatā-avacchedaka-avacchinna-atyantābhāvīya-pratiyogitā sā samaniyatatva-nirūpitā, tad eva samaniyatatvaṃ śakyatā-nirūpitam, saiva śakyatā hāṭaka-pada-avacchinnā hāṭakatva-nirūpitā, tadviparyayeṇa ca.

It is clear that (t)‘The term gold is not equal to crown, simply because that which is a crown is not indifferently called gold, &vv’. Let us consider the assertions: ‘Gold is mined’ or ‘In the periodic table, the chemical element known as gold has the atomic number 79’. Here, any substitution would clearly be nonsense because crowns are not mined, nor are they chemical elements in the periodic table, nor do they have an atomic number.Footnote 46 The grounds for the use (pravṛtti-nimitta) of the terms ‘mukuṭa’ and ‘hāṭaka’ is plainly distinct, thus the two terms cannot be coextensive.

Moreover, equality is unquestionably a symmetrical relation since it identifies coreferentiality between terms, as in formulas such as [16] and as expressly stated by the operator ‘⇌’ (go = sāsnādimat as well as sāsnādimat = go). Since |‘gt’|=G ∧ |‘st’|=S ∧ (G=S), equality is a relation having set G—that is S—as its reference domain and range (i.e., Qsub[16]: G ↦ G or S ↦ S). The same is not true for V and

, which are consequently not symmetric. Consider the case of ‘A smiling man’ (smayan puruṣaḥ): while this man is qualified by his smile, it is harder to accept that a smile is qualified by this man who smiles—just as in the case of blueness qualifying a pot, which simply cannot be qualified by pot-ness. Thus, relation V openly appears to be not-symmetric and requires its proper inverse (V−1) to be reversed.Footnote 47 Syntactic homogeneity (sāmānādhikaraṇya, Ṇ) is, on the contrary, too vague a notion to be considered symmetrical or not. In fact, its possible symmetry depends on its interpretation: if Ṇ means equality—as in the sentence sāsnādimatī gauḥ—then it will be transitive and symmetric. As shown, however, if it was interpreted as a general instance of qualification, it could no longer be said to be either symmetrical or transitive—just as in nīlo ghaṭaḥ (cf. also fn. 47). The issue might not be quite so predictable with regard to non-difference. In the golden crown case, if

, which are consequently not symmetric. Consider the case of ‘A smiling man’ (smayan puruṣaḥ): while this man is qualified by his smile, it is harder to accept that a smile is qualified by this man who smiles—just as in the case of blueness qualifying a pot, which simply cannot be qualified by pot-ness. Thus, relation V openly appears to be not-symmetric and requires its proper inverse (V−1) to be reversed.Footnote 47 Syntactic homogeneity (sāmānādhikaraṇya, Ṇ) is, on the contrary, too vague a notion to be considered symmetrical or not. In fact, its possible symmetry depends on its interpretation: if Ṇ means equality—as in the sentence sāsnādimatī gauḥ—then it will be transitive and symmetric. As shown, however, if it was interpreted as a general instance of qualification, it could no longer be said to be either symmetrical or transitive—just as in nīlo ghaṭaḥ (cf. also fn. 47). The issue might not be quite so predictable with regard to non-difference. In the golden crown case, if

is interpreted as a viśiṣṭa-jñāna—in which the crown is non-different (

is interpreted as a viśiṣṭa-jñāna—in which the crown is non-different (

) from the gold by which it is qualified (V)—then abheda will clearly be non-symmetrical. Moreover, if non-difference were then further interpreted as ‘consisting of’ or ‘being made of’, it would be newly non-symmetrical. Indeed, it can safely be stated that a pot is ultimately clay (cf. Chāndogya Up. 6.1.4–6), but it is harder to accept that clay is a pot or consists of a pot. Along the same lines, VM’s interpretation explicitly puts abheda in contact with causation (kāryakāraṇabhāva, K) in general and with material cause (upādānakāraṇa, uK) in particular (VM-B, p. 72–73). Thus, if k⌝uK⌞r, yā upādānakāraṇatā kāraṇa-avacchinnā sā kārya-nirūpitā (‘Material causeness, conditioned by the effect (r), occurring in the cause (k)’); its symmetric form is clearly false: *r⌝uK⌞k, *yā upādānakāraṇatā kāryāvacchinnā sā kāraṇa-nirūpitā (*‘Material causeness, conditioned by the cause, occurring in the effect’). Then, the effect (kārya, r) could be said, once proved, to be non-different from the cause (kāraṇa, k) from which it derives: k⌝

) from the gold by which it is qualified (V)—then abheda will clearly be non-symmetrical. Moreover, if non-difference were then further interpreted as ‘consisting of’ or ‘being made of’, it would be newly non-symmetrical. Indeed, it can safely be stated that a pot is ultimately clay (cf. Chāndogya Up. 6.1.4–6), but it is harder to accept that clay is a pot or consists of a pot. Along the same lines, VM’s interpretation explicitly puts abheda in contact with causation (kāryakāraṇabhāva, K) in general and with material cause (upādānakāraṇa, uK) in particular (VM-B, p. 72–73). Thus, if k⌝uK⌞r, yā upādānakāraṇatā kāraṇa-avacchinnā sā kārya-nirūpitā (‘Material causeness, conditioned by the effect (r), occurring in the cause (k)’); its symmetric form is clearly false: *r⌝uK⌞k, *yā upādānakāraṇatā kāryāvacchinnā sā kāraṇa-nirūpitā (*‘Material causeness, conditioned by the cause, occurring in the effect’). Then, the effect (kārya, r) could be said, once proved, to be non-different from the cause (kāraṇa, k) from which it derives: k⌝

⌞r. However, merely switching the relata is nothing but nonsense here as well: *r⌝

⌞r. However, merely switching the relata is nothing but nonsense here as well: *r⌝

⌞k (*‘The cause is non-different from the effect’). A negation of symmetry could be also achieved by interpreting non-difference as a case of ‘part and whole relation’, since what possesses parts (avayavin) might be conceived as non-different from the parts (avayava) it possesses, but not vice versa. Thus, while it is reasonable to say that ‘A horse is not different from a limb of itself’, ‘A limb is not-different from a horse’ sounds slightly stranger in some way. In the form of joke, one of the Buddha’s teeth is not the Buddha.Footnote 48

⌞k (*‘The cause is non-different from the effect’). A negation of symmetry could be also achieved by interpreting non-difference as a case of ‘part and whole relation’, since what possesses parts (avayavin) might be conceived as non-different from the parts (avayava) it possesses, but not vice versa. Thus, while it is reasonable to say that ‘A horse is not different from a limb of itself’, ‘A limb is not-different from a horse’ sounds slightly stranger in some way. In the form of joke, one of the Buddha’s teeth is not the Buddha.Footnote 48

Moreover, while equality is a transitive relation, non-duality is not—and neither is V. If hāṭaka = suvarṇa and suvarṇa = kanaka, then hāṭaka = kanaka (cf. fn. 46), since these padas have one and the same grounds of use. And yet, being bt the property kaṭakatva (‘bracelet-hood’, for |bt|=B), given h.Ṇ⌞b (A golden bracelet) and [2] h.Ṇ⌞m (A golden crown)—or h.

⌞b (A bracelet not-different from gold) and [27] h.

⌞b (A bracelet not-different from gold) and [27] h.

⌞m (A crown not-different from gold)—it patently does not follow that *b.Ṇ⌞m (A crown which is a bracelet) or *b.

⌞m (A crown not-different from gold)—it patently does not follow that *b.Ṇ⌞m (A crown which is a bracelet) or *b.

⌞m (A crown non-different from a bracelet). In other words, if the crown is golden and so is the bracelet, it does not follow that the crown is a bracelet. One last remark about equality: it is surely licit to use it reflexively, but such a use appears somehow secondary in that it is lacking any informative value. Indeed, whereas it could be of some use to state that ‘gold = suvarṇa = Au (in the periodic table)’, it is much less interesting to repeat that ‘gold = gold’. The same holds for non-difference: it is safe to assert that ‘m.

⌞m (A crown non-different from a bracelet). In other words, if the crown is golden and so is the bracelet, it does not follow that the crown is a bracelet. One last remark about equality: it is surely licit to use it reflexively, but such a use appears somehow secondary in that it is lacking any informative value. Indeed, whereas it could be of some use to state that ‘gold = suvarṇa = Au (in the periodic table)’, it is much less interesting to repeat that ‘gold = gold’. The same holds for non-difference: it is safe to assert that ‘m.

⌞m’ (A crown non-different from a crown), but such an assertion is utterly uninteresting.

⌞m’ (A crown non-different from a crown), but such an assertion is utterly uninteresting.

To summarize, it turns out that, even though the crown is in fact gold, it cannot be said to be equal to gold, nor crown-ness to gold-ness. Nonetheless, this crown is still gold, a fact which renders the assertion ‘The crown is not gold’ (*m ≠ h) also concurrently false. VM openly declares that non-difference is never reducible to a relation of reciprocal absence (parasparābhāva; i.e.

). If that were the case, there would exist only simple difference and not any kind of non-difference. This eventuality is simply impossible (asaṃbhava), however, because it would be directly contradictory (virodha) to non-difference: by hypothesis, the two properties do co-exist (saha-avasthāna) in the very same locus.Footnote 49 If simple difference (*m ≠ h) were the case, then the relation between gold-ness and crown-ness in a golden crown would be assimilable to a relation to whatever other property, say, horse-hood: if 〈m, h〉∈

). If that were the case, there would exist only simple difference and not any kind of non-difference. This eventuality is simply impossible (asaṃbhava), however, because it would be directly contradictory (virodha) to non-difference: by hypothesis, the two properties do co-exist (saha-avasthāna) in the very same locus.Footnote 49 If simple difference (*m ≠ h) were the case, then the relation between gold-ness and crown-ness in a golden crown would be assimilable to a relation to whatever other property, say, horse-hood: if 〈m, h〉∈

was read as m ≠ h, then a crown would also be not-different from a horse. In other terms, if non-duality was conceived as equality or diversity, we would be pushed back to the starting contradiction (cf. P1): *m = h is false, as is *m ≠ h. Thus, the crown is (i.e., Ṇ, V, and

was read as m ≠ h, then a crown would also be not-different from a horse. In other terms, if non-duality was conceived as equality or diversity, we would be pushed back to the starting contradiction (cf. P1): *m = h is false, as is *m ≠ h. Thus, the crown is (i.e., Ṇ, V, and

) surely gold, yet not in the sense implied by equality or difference.

) surely gold, yet not in the sense implied by equality or difference.

Now, could non-difference be interpreted as a relation of identity? Let us try to interpret the assertion hāṭakaṃ mukuṭam in terms of identity following the model of [22]–[24]—the crown is (Ṇ) gold, in the sense that the crown should be said to be identical (I) to gold:

*[29] *h ⇌ I⌞m ∨ [30] h . ∄−1 ⌞ ( ⌞ m)

⌞ m)

That is, according to the counterfactual definition of identity, the crown should not be the counterpositive of an absolute absence of a mutual absence with respect to something which is that very entity, i.e. the gold. Here, a first important point: [30] is true for h∉|

⌞m|, i.e. ‘An instance of gold (h) is meant to belong to the singleton |m| = {m}’, which is indeed the case (‘A crown is not the counterpositive of an absolute absence of a mutual absence with respect to an instance of gold’). What we are talking about is this crown, which is (i.e., V, Ṇ,

⌞m|, i.e. ‘An instance of gold (h) is meant to belong to the singleton |m| = {m}’, which is indeed the case (‘A crown is not the counterpositive of an absolute absence of a mutual absence with respect to an instance of gold’). What we are talking about is this crown, which is (i.e., V, Ṇ,

, and I) this gold: what is at stake here is this very singleton. Non-difference fits the counterpositive definition of identity because these two relations ontologically focus on the very same artha. So far, non-difference seems to coalesce dangerously into identity.

, and I) this gold: what is at stake here is this very singleton. Non-difference fits the counterpositive definition of identity because these two relations ontologically focus on the very same artha. So far, non-difference seems to coalesce dangerously into identity.

However, let us now consider two additional points: on the one hand, the so-called Principle of the Indiscernibility of Identicals (sometimes called Leibniz’s Law, LL): for all x and y, if x = y (i.e. 〈x, y〉∈I), then x and y have the same properties—which is commonly considered quite uncontroversial. On the other hand, what is known as the Principle of Identity of Indiscernibles (PII): for all x and y, if x and y have the same properties, then x = y (i.e. 〈x, y〉∈I)—which, on the contrary, is highly controversial. Whether or not PII functions, this principle does not apply here anyway. In the assertion under examination stating that hāṭakaṃ mukuṭam, there is no trace of the commonality of properties, much less of indiscernibility. And yet, the situation regarding LL is even worse: if LL applied here, then crown and gold would display the same properties, which they do not—simply because we are still dealing with two fully distinct properties (cf. Leibniz 1989, p. 42 and 1981, p. 230).

Let us take a step forward. If non-difference were identity tout court and the indiscernibility of property followed for LL, then non-difference would pass the Substitutivity Test (ST). Still, consider the following case: if *[29] *m⇌I⌞h (The crown is identical to the gold), then obviously, by substitution: m⇌I⌞m and h⇌I⌞h (The crown is identical to the crown, the gold to the gold). The same holds true for a golden bracelet (kaṭaka, b): if *b⇌I⌞h, then b⇌I⌞b and h⇌I⌞h. In this case, however, it would follow—again by substitution between identical indiscernibles—that: *b⇌I⌞m (This bracelet is identical to this crown), which is pure nonsense—simply because a bracelet, perfectly discernible from a crown, is not a crown. Thereby, non-difference clearly fails the ST and, since fallacies are generated, it appears to be non-reducible to identity tout court. Moreover, this last example is a clear case of non-transitivity: non-difference has thus proven to be a non-transitive relation, while identity of course is—if x is identical to y, y is identical to z, z is identical to x (cf. supra, Quine 1981, pp. 134–136).Footnote 50

Interpreted as a case of qualified cognition (V), non-difference does not even appear as a symmetric relation, and this is because V is certainly not one. It has been shown that, for SVN, the property Gold-ness in crowns is a subset of the set Properties of crowns: |ht|⊆|V(Ṇ)⌞mt| (cf. P1), for V(Ṇ): M↦V(Ṇ)[M] and V(Ṇ)[M]⊆M. Non-difference can analogously be construed as a relation whose domain is M (Crowns) and whose range is 2[M] (What is non-different from crowns, e.g. gold-ness, heaviness, etc.): i.e. relation 2: M↦2[M], for 2[M]⊆M. What is at stake here is the gold-ness occurring in a crown. Inasmuch as the reference domains are distinct, by virtue of V, the relata cannot be simply inverted as in case of symmetry; what is needed instead is a fully fledged inverse relation. The same is clearly true for different kinds of non-difference interpretations as well, such as causation, ‘part and whole’, ‘consisting of’, etc.Footnote 51

Cardinality also could help in distinguishing between non-difference and identity. Indeed, it has been shown that the cardinality of identity is strictly equal to one (card(I) =1; cf. [23]). I will argue here that non-difference can bear a cardinality equal to and greater than one (card(

) ≥1). The assertion mukuṭa-hāṭakayor abhedaḥ clearly begs for a cardinality equal to one, since there is but one crown here, a golden one:

) ≥1). The assertion mukuṭa-hāṭakayor abhedaḥ clearly begs for a cardinality equal to one, since there is but one crown here, a golden one:

[31] (h .

⌞m)⌝ℕ⌞(=1t)

yad abhinnatā-avacchedakāvacchinna-paryāptitvaṃ tad ekatva-nirūpitam, saiva abhinnatā hāṭaka-niṣṭhā mukuṭa-nirūpitā; ‘Non-difference, conditioned by a crown, is limited by a specimen of gold, for card(

) =1(since they are but the same object)’.

However, let us try to interprete

as an avayavāvayavin relation (‘Part and whole’) in which it turns out that multiplicity is structurally embedded: aśvo svāṅgābhinnaḥ (‘Non-difference between a horse (a) and its own limbs (ṅ)’; for 〈a, ṅ〉∈

as an avayavāvayavin relation (‘Part and whole’) in which it turns out that multiplicity is structurally embedded: aśvo svāṅgābhinnaḥ (‘Non-difference between a horse (a) and its own limbs (ṅ)’; for 〈a, ṅ〉∈

) or ghaṭaḥ kapāladvayābhinnaḥ, (‘Non-difference between a pot (g) and its own halves (k)’; for 〈g, k〉∈

) or ghaṭaḥ kapāladvayābhinnaḥ, (‘Non-difference between a pot (g) and its own halves (k)’; for 〈g, k〉∈

). That, just because avayavī-avayavābhedaḥ (‘Non-difference between the whole (ī) and its constituents (ν)’; for 〈ī, ν〉∈

). That, just because avayavī-avayavābhedaḥ (‘Non-difference between the whole (ī) and its constituents (ν)’; for 〈ī, ν〉∈

). Thus:

). Thus:

[32] (a .

−1 ⌞ṅt)⌝ℕ⌞(≥1t) ∨ (g .

−1 ⌞kt)⌝ℕ⌞(≥1t) ∨ (ī .

−1 ⌞vt)⌝ℕ⌞(≥1t)

yad viparītābhinnatā-avacchedakāvacchinna-paryāptitvaṃ tad ekatvādi-nirūpitā, saiva viparītābhinnatā (aśva-; or ghaṭa-; or avayavī-)niṣṭhā (aṅgatva-; or kapālatva-; or avayavatva-)nirūpitā; (t)‘The inverse relational abstract of non-difference relation, conditioned by the constituents (such as limbs or halves), is limited by the whole (such as a horse or a pot), for card(

) ≥1’. Iff, in s.n., (∃x, ~∀y | Īx, ~Vy) (〈x, y〉∈

).Footnote 52

Looking closer, even interpretations based on upādānakāraṇa (uK) or viśeṣaṇa-viśeṣya-bhāva (V) might display the same feature. Moreover, all of the above cases are ‘one-to-many’ relations. Multiplicity might be introduced into the domain as well, however, thereby obtaining ‘many to one’ and ‘many to many’ relations of non-difference. For instance, vahnyabhinne prakāśanadāhakārye, ‘The effects of making light and heat are non-distinct from fire’, or bāṣpābhinnā meghāḥ, ‘Clouds are non-different from water vapour’. Let us take now a step forward by considering, e.g., the 88 notes corresponding to the standard 88 piano keys (K={k1, …, k88}, for card(K)=88). Now, a non-difference relation can be construed having as its domain every possible piano piece, written or not-yet-written, potentially counting infinite notes (P={p1, …, pn} for card(P) = ℵ0; i.e. aleph-zero, the cardinality of the set of all natural numbers): thus, having dom(

) = P and ran(

) = P and ran(

) = K, i.e.

) = K, i.e.

: P↦K. Although it is pointless to say that every possible piano piece is equivalent, equal or identical to the 88 notes corresponding to the 88 piano keys, it could be perfectly sound to state that the former are non-different from the latter. In standard notation: (∀x, ~∀y | Px, ~Ky) (〈x, y〉∈

: P↦K. Although it is pointless to say that every possible piano piece is equivalent, equal or identical to the 88 notes corresponding to the 88 piano keys, it could be perfectly sound to state that the former are non-different from the latter. In standard notation: (∀x, ~∀y | Px, ~Ky) (〈x, y〉∈

). Once more, a symmetric inversion of the relata is not possible. It is simply false that the 88 notes corresponding to the 88 piano keys are non-different from every possible piano piece: i.e., *〈y, x〉∈

). Once more, a symmetric inversion of the relata is not possible. It is simply false that the 88 notes corresponding to the 88 piano keys are non-different from every possible piano piece: i.e., *〈y, x〉∈

is false, since only 〈y, x〉∈

is false, since only 〈y, x〉∈

−1 is true. Obviously, the same could be said about writing systems and literature or about the five DNA-RNA nitrogenous bases and living beings.Footnote 53 A novel is non-different from, say, the Latin alphabet, but not vice-versa (i.e., 〈novel, alphabet〉∈

−1 is true. Obviously, the same could be said about writing systems and literature or about the five DNA-RNA nitrogenous bases and living beings.Footnote 53 A novel is non-different from, say, the Latin alphabet, but not vice-versa (i.e., 〈novel, alphabet〉∈

and 〈alphabet, novel〉∈

and 〈alphabet, novel〉∈

−1 are true, but *〈alphabet, novel〉 ∈

−1 are true, but *〈alphabet, novel〉 ∈

is false). In the same way, organisms are non-different from their nitrogenous basis, whereas these latter cannot be said to be simply non-different from the former (i.e., 〈organisms, n-basis〉∈

is false). In the same way, organisms are non-different from their nitrogenous basis, whereas these latter cannot be said to be simply non-different from the former (i.e., 〈organisms, n-basis〉∈

and 〈n-basis, organisms〉∈

and 〈n-basis, organisms〉∈

−1 are true, but *〈n-basis, organisms〉∈

−1 are true, but *〈n-basis, organisms〉∈

is false).

is false).

This last remark might cast new light—from an advaita perspective—on a classical issue concerning identity. The case of Rāma and his description as ‘prince of Ayodhyā’ has already been discussed above. The case is analogous to the famous ‘Scott = author of Waverley’. It is well known that this case and its potentially paradoxical consequences have been analysed in detail, firstly through the distinction between names, descriptions, and denotations.Footnote 54 Yet, it might still be usefully rephrased in terms of non-difference: ‘Rāma is non-different from the prince of Ayodhyā’—just as ‘Scott is non-different from the author of Waverley’. It will come as little surprise that these assertions cannot pass the ST, since they involve properties which are distinct and highly informative (‘being called Rāma’ and ‘being the prince of a city called Ayodhyā’) even if referring to the very same referent (the man called Rāma). Nonetheless, pushing the argument even further and assuming that Dāśarathi Rāma was a real living human being—just as sir W. Scott was—it could be said that Rāma is non-different from his DNA-RNA nitrogenous bases or his biochemical bases in general—and the same for Scott.

[33] (r .

−1⌞bt)⌝ ℕ ⌞(≥1t)

yad viparītābhinnatā-avacchedakāvacchinna-paryāptitvaṃ tad ekatvādi-nirūpitam, saiva viparītābhinnatā rāma-niṣṭhā mahābhūtatva-nirūpitā; (t)‘Rāma (r) is non-different from his biochemical bases (b)’.Footnote 55

The same holds for Scott as well, because every human could be said to be non-different from his/her biology.

[33a] (pt⌝

−1⌞bt)⌝ ℕ ⌞(≥1t)

yad viparītābhinnatā-avacchedakāvacchinna-paryāptitvaṃ tad ekatvādi-nirūpitam, saiva viparītābhinnatā puruṣatva-avacchedakāvacchinnā mahā-bhūtatva-nirūpitā; ‘Humanhood (puruṣatva, pt) is non-different from its biochemical-base-hood (bt)’;

iff |pt|⊆|

−1⌞bt| (card

2≥1); in s.n. (∀x, ~∀y | Px, ~By) (〈x, y〉 ∈).

Clearly [33a] has nothing to do with the identity we evoked when talking about Rāma or Scott, since it involves general properties and no longer deals with a singularity, much less defined descriptions. Being distinctly relational in nature, [33a] could not be straightforwardly reduced to a predicative schema either, nor does it claim that ‘Humankind is its biology’—only that the former is non-distinct from the latter.

Conclusions

The assertion ‘A golden crown’ displays an evident case of sāmānādhikaraṇya (Ṇ), syntactical homogeneity and coreferentiality. The notion of Ṇ-relation is nevertheless extremely vague and requires further interpretation. It has been shown that: Ṇ ≠ E; Ṇ ⊆ V; Q ⊆ Ṇ; I ⊆ Ṇ;

⊆ Ṇ. Thus, Ṇ might or might not be said to be reflexive, symmetric, or transitive, depending on the chosen interpretation. For instance, if Ṇ is supposed to be a particular case of V—as the assertion ‘A golden crown’ suggests—it will be non-symmetrical, non-transitive and reflexive only in a secondary, uninformative, sense.

⊆ Ṇ. Thus, Ṇ might or might not be said to be reflexive, symmetric, or transitive, depending on the chosen interpretation. For instance, if Ṇ is supposed to be a particular case of V—as the assertion ‘A golden crown’ suggests—it will be non-symmetrical, non-transitive and reflexive only in a secondary, uninformative, sense.

It has also been shown that equivalence (tulyatva; E) first and foremost entails one shared property (taddharmavattva, tdt) among many. It has also proven to be a symmetric (⇌) and transitive relation whose cardinality is strictly greater than one. According to [10], the equivalence between generic elements a and b can be expressed in NL as: ((b.tdt) ⇌E⌞(a.tdt))⌝ℕ⌞(≥ 2t); iff (a ≠ b) ∧ ((a, b) ∈|tdt|) ∧ (card(E) ≥ 2). In keeping with these truth conditions, interpretations of equivalence show that: E ≠ Ṇ; E ≠ Q; E ≠ I; E ≠

. That is, an equivalence relation, stricto sensu, is to be considered distinct from coreferentiality, equality, identity, and non-difference.Footnote 56

. That is, an equivalence relation, stricto sensu, is to be considered distinct from coreferentiality, equality, identity, and non-difference.Footnote 56

Equality (samaniyatatva; Q) has proven to mean invariable concomitance, or mutual pervasion, with regards to names or expressions. It appears to be a reflexive (albeit in a secondary sense, because in this case it lacks any informative value), symmetric, and transitive relation, whose cardinality is greater than or equal to one. According to [17] the equality between two generic expressions ‘a’ and ‘b’—in relation to their primary meaningfulness (śakyatā, Ś) and individual manifestations with respect to a given generic property (taddharmavattva, tdt)—can be expressed in NL as: (‘a’⌝Ś⌞tdt)⇌Q⌞(‘b’⌝Ś⌞tdt))⌝ℕ⌞(≥1t); iff (|‘a’| = b∈(|tdt|=TD) ∧ (|‘b’| = a∈(|tdt|=TD) ∧ (card(TD) ≥1). The above relation of equality between terms can be promptly interpreted as a case of identity (I) and non-difference (

) of their extension. If 〈‘a’,‘b’〉∈Q, then for AE also 〈‘a’,‘b’〉∈I and 〈‘a’,‘b’〉∈

) of their extension. If 〈‘a’,‘b’〉∈Q, then for AE also 〈‘a’,‘b’〉∈I and 〈‘a’,‘b’〉∈

. If linguistically 〈‘gold’, ‘Au’〉∈Q, then ‘gold’ is extensionally non-different from ‘Au’ (〈‘gold’, ‘Au’〉∈

. If linguistically 〈‘gold’, ‘Au’〉∈Q, then ‘gold’ is extensionally non-different from ‘Au’ (〈‘gold’, ‘Au’〉∈

): every case of equality is, arthataḥ, also non-duality, but not the other way around (〈gold, crown〉∈

): every case of equality is, arthataḥ, also non-duality, but not the other way around (〈gold, crown〉∈

, yet ‘gold’≠‘crown’ ∧ |‘gold’| ≠ |‘crown’|). In summary: Q ≠ E (cf. §1 and fn. 56); Q ⊆

, yet ‘gold’≠‘crown’ ∧ |‘gold’| ≠ |‘crown’|). In summary: Q ≠ E (cf. §1 and fn. 56); Q ⊆

, and consequently Q ⊆ (Ṇ ⊆ V); lastly, I is Q arthataḥ, while Q is I śabdataḥ (cf. § 2–3 and formulas [22]–[26]).

, and consequently Q ⊆ (Ṇ ⊆ V); lastly, I is Q arthataḥ, while Q is I śabdataḥ (cf. § 2–3 and formulas [22]–[26]).

Identity (tādātmya; I) appears as a reflexive (although somehow paradoxically, cf. supra fn. 28), symmetric, and transitive relation whose cardinality is strictly equal to one. Identity, as ‘not the counterpositive of a difference resident in something of the same kind’, can be expressed, for the generic primitive a, as (cf. [22]-[25]): (a⇌∄−1⌞(

⌞a′))⌝ℕ⌞(1t); iff (a∉(|

⌞a′))⌝ℕ⌞(1t); iff (a∉(|

⌞a′| = \(\mathrm{\overline{A}}^{\prime}\))) ∧ (A′={a′}). In brief: I ≠ E (cf. §1 and fn. 56); I ⊆

⌞a′| = \(\mathrm{\overline{A}}^{\prime}\))) ∧ (A′={a′}). In brief: I ≠ E (cf. §1 and fn. 56); I ⊆

, and thus I ⊆ (Ṇ ⊆ V); again, I and Q are the artha and śabda sides of the same coin (cf. previous point).

, and thus I ⊆ (Ṇ ⊆ V); again, I and Q are the artha and śabda sides of the same coin (cf. previous point).

Non-difference (abheda;

) has been shown to be a reflexive (although in a secondary sense), non-symmetric, and non-transitive relation whose cardinality is greater than or equal to one. Every instance of non-difference appears to be a case of co-reference and qualified cognition (viśiṣṭa-jñāna), but not the other way around. Indeed, the assertion daṇḍī puruṣaḥ qualifies a man by means of a staff, though it does not follow this man is non-different from his staff (cf. fn. 45). Thereby:

) has been shown to be a reflexive (although in a secondary sense), non-symmetric, and non-transitive relation whose cardinality is greater than or equal to one. Every instance of non-difference appears to be a case of co-reference and qualified cognition (viśiṣṭa-jñāna), but not the other way around. Indeed, the assertion daṇḍī puruṣaḥ qualifies a man by means of a staff, though it does not follow this man is non-different from his staff (cf. fn. 45). Thereby:

⊆ (Ṇ ⊆ V). It follows that SVN rules

⊆ (Ṇ ⊆ V). It follows that SVN rules

, for

, for

[A] ⊆ A. That is, non-difference is an instance of closure as well, because the set ‘Non-different from what belongs to the generic set A’ is A-closed under the relation

[A] ⊆ A. That is, non-difference is an instance of closure as well, because the set ‘Non-different from what belongs to the generic set A’ is A-closed under the relation

(i.e.

(i.e.

: A ↦

: A ↦

[A]). On one hand, in cognitions connecting a pot and its colour (nīlo ghaṭaḥ, a case of V(Ṇ)) or a crown and its material (hāṭakaṃ mukuṭam, a case of uK; cf. end of §4), the relata in both cases are to be understood as non-different, yet in a different sense. The same clearly holds true for ‘part and whole’ relations (A, avayavāvayavi-bhāva). On the other hand, non-difference cannot even be reduced to identity; although they could appear as highly resembling each other, they do not collapse into other. In fact, their cardinality prevents such coalescence (card(I)=1 vs. card(