Abstract

This paper analyzes the role of dynamic capabilities in the transformation of a multi-organizational setting. I conduct an embedded multi-case study in which the cases represent critical transformational events in the history of a shopping center. The five critical transformational events, which have exerted substantial influence on the organizations operating in the context, are concerned with the construction of new premises, modernization of existing premises, and the introduction of new services. I analyze and classify related (dynamic) capabilities of individual organizations, resulting in aggregated outcomes that determine the evolution of the entity. Applying an abductive case research strategy, I then generate five distinct theoretical results on the effects and the interconnectedness of the multi-organizational context, the individual organizations, and their dynamic capabilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

This study explores the dynamic capabilities related to the transformation of a multi-organizational setting. More specifically, it examines how the capabilities of individual organizations can shape the context in which the organizations operate and/or the organization’s response to changes in the context. The research into the core organizational phenomena that purposefully adapt an organization’s resource base (for example, change and transformation) has prompted scholars to address the capabilities that underpin these phenomena (Helfat and Peteraf 2015; Teece et al. 1997; Teece 2007). Notwithstanding recent advances in understanding organizational change through dynamic capabilities, we lack a theoretical understanding of how such capabilities act across organizational boundaries within a transformative context.

A multi-organizational setting consists of an organizational network where individual organizations seek to gain an advantage from the existence of the other organizations, despite the increased threat of competition (Sydow and Windeler 1998). Any individual organization in such a setting is influenced by its surroundings, which comprise two distinct parts. The context of the multi-organizational setting refers to the organizational network itself, and the environment refers to all the external actors that influence the context. A typical example of a multi-organizational setting is a shopping center, the context of which might include the owner, the coordinating body, the financiers, the managing consultants, the city planning department, and most importantly, the various tenants (Teller 2008). This context is influenced by environmental factors, such as accessibility, competition, and local customer needs (Teller et al. 2016). Individual organizations typically respond to the changing context and environment by transforming their operating procedures, creating a network of interactive influences within the particular context (Tsoukas and Chia 2002; Levinthal 1991).

This paper uses an abductive case research approach to examine the dynamic capabilities involved in such transformations. The multi-organizational setting of the study is the Finnish shopping center, Itis, between 1970–2012. After a lengthy period of planning and development, the center was opened in 1984 and has since tripled in size. In 1992, as a result of its first expansion, it became the largest shopping center in the Nordic countries. Over the period studied, a total of 468 retailers have operated within Itis’s multi-organizational setting. The services provided have increased in line with the size of the center, which has hosted best-selling global actors such as H&M (Hennes and Mauritz) and Zara, as well as the major Finnish department stores Stockmann, Sokos, and Anttila.

The shifting configuration and unique characteristics of the numerous individual organizations involved mean that transformations within a multi-organizational setting are often context-specific endeavors. However, I argue that the organizations have dynamic capabilities for either influencing or adapting to transformational events within such a context. By identifying and considering these capabilities, it is possible to determine the kinds of changes individual organizations are able to react to and how they do so, and thus explain the evolution of organizations (Levinthal and Marino 2015).

In the literature, dynamic capabilities have been defined as the organization’s capability to purposefully adapt its resource base within the environment in which it operates (Teece et al. 1997; Nelson and Winter 1982). An organization that can recognize its capabilities can identify its effective and ineffective operating patterns (Eisenhardt and Martin 2000). I argue that this also applies to more complex settings that involve multiple organizations. Despite the numerous applications of the dynamic capability theory, the existing literature fails to address the capabilities associated with multi-organizational settings. This paper therefore explores the role of capabilities in governing contextual transformations within the multi-organizational setting of a shopping center, by identifying and classifying such capabilities and analyzing their aggregate influence. In short, I address the following research question: How do capabilities function in the transformation of a multi-organizational context?

The paper proceeds as follows. First, I conduct a literature review. Since there is no existing literature on dynamic capabilities within multi-organizational settings, my review analyzes two distinct streams of literature: the literature on multi-organizational settings and the literature on dynamic capabilities. I combine these before describing my research methodology. Before engaging in theory building, I provide a rather detailed narrative of the history of Itis and its most important transformational events. Specifically, I identify five critical transformational events and divide the lifecycle of Itis into four distinctive eras or phases that are initiated by or culminate in these critical events. Finally, I identify dynamic capabilities related to these events, classifying them into three types. My analysis generates five theoretical results on capabilities that illustrate the interrelatedness of the context, the individual organizations, and the capabilities within a multi-organizational setting. Hence, my results contribute to the understanding of the role of dynamic capabilities in multi-organizational settings, thus providing insight into their management and coordination.

2 Literature review

2.1 Literature review on multi-organizational settings

The term multi-organization was introduced by Stringer (1967) to describe a setting where individual decision makers manage organizations within an organizational network. Building on this, Huxham (1991) specified the term to describe situations where several organizations or parts of organizations—each with its own affiliations, goals, and values—are involved in achieving a plan or an end result. The differences among the individual organizations enable them to make distinct contributions to the joint venture, but these differences are also an inherent source of tension in the collaboration process (Bengtsson and Kock 2014; Brass et al. 2004; Huxham and Beech 2003). The concept of an inter-organizational network (inter-firm network) has been similarly defined in that it has the same boundary conditions; however, this has typically been the case in settings where the focus has been on dyadic relationships (e.g., Child and McGrath 2001; Grandori and Soda 1995; Sydow and Windeler 1998; Zollo et al. 2002). In my research, many of the interesting relationships that allow for rich descriptions are indeed dyadic, but I also consider multi-organizational interactions that are simultaneously influenced by a vast number of independent organizations (cf. Eden and Huxham 2001).

For the purposes of this paper, and largely in accordance with the definitions provided by Sydow and Windeler (1998) in their study of inter-firm networks, a multi-organizational setting is conceived as an arrangement among distinct but related business organizations; it is a setting that operates differently from both hierarchies and markets. In a hierarchy, the roles of and relationships among the individual organizations are strictly defined (Huxham 1991), whereas a market is characterized purely by the competition among organizations (MacMillan and Farmer 1979). At the time when the most important transformational events were taking place at the Itis shopping center (i.e., the 1980s and ‘90 s), many hierarchical organizational entities worldwide were being replaced by multi-organizational settings (Schilling and Steensma 2001). The literature from this era emphasizes the way in which multi-organizational settings differ from any hierarchy or market. It refers to at least three structural properties: network-relationships between individual organizations, i.e., the relationships are shaped and designed between organizations that have legally separate identities but are economically interrelated; a certain degree of reflexivity, i.e., the network itself becomes an object of “signifying, organizing, and legitimizing”; and a logic of exchange that combines competition and cooperation, i.e., relationships among organizations shape their individual expectations and routines, which turns the dynamics within these networks into a collective logic (Sydow and Windeler 1998: 267). When compared with the design of an individual organization, these structural properties render the organization of this type of setting more difficult, but they also offer additional aggregated capabilities for adaptation (Mariotti and Cainarca 1986; Sydow and Windeler 1998; Zenger and Hesterly 1997; Zollo et al. 2002).

2.2 Literature review on dynamic capabilities

Since the 1990s, the need to keep pace with increasing competition has driven firms to constantly adapt, reconfigure, and recreate their resources and capabilities (Pisano 2017; Wang and Ahmed 2007). Teece (2018) examined how organizations keep up with their evolving surrounding and identified the existence of types of dynamic capabilities that determine the speed, and degree to which, firm’s particular resources can be aligned and realigned to match the requirements and opportunities. Dynamic capabilities and their inputs are seen to include not only the higher-level routines, such as the building blocks of their execution, but also the skills and competencies that support their functioning (Felin et al. 2012; Winter 2000). More specifically, Winter (2003: 994) has defined them as “high-level routines (or collections of routines) that, together with its implementing input flows, confers upon an organization's management a set of decision options for producing significant outputs of a particular type.” The variety of applications for the concept of dynamic capabilities came about as an attempt to explain competitive advantage in situations that place high demands on the degree of reflexivity (Helfat and Winter 2011). In such environments, the operational routines that drive competitive success in more stable conditions—such as conducting range-reviews, pricing, and the design of promotions in retail space (e.g., Paavola and Cuthbertson 2018)—quickly become outdated and so fall short of ensuring success (Felin and Powell 2016).

The multi-organizational setting of a shopping center is typically not noted for its dynamism nor it is generally considered to be under constant transformation. However, the traditional tools of organizational design, such as hierarchies, chains of command, functional areas, or long-term planning, are not best-suited to situations when change does take place (Felin and Powell 2016). In such situations, firms need dynamic capabilities to “create, extend, and modify the ways in which they make their living” (Helfat et al. 2007: 1). From a managerial perspective, the understanding of capabilities is considered to be an important aid for management endeavoring to combine competitive advantage with an element of future-proofing in changing environments (Teece et al. 1997).

2.3 Combining the viewpoints

The above research points to the co-constitution of multi-organizational settings and dynamic capabilities. Since dynamic capabilities are crucial to effecting transformations and therefore determine the success of organizations, it is natural to expect them to also play a role in multi-organizational settings and their transformations. Despite the fact that research on dynamic capabilities has primarily focused on organizations’ ability to transform, prior research has not addressed the joint influence of the varying dynamic capabilities of multiple organizations or markets (Schilke et al. 2018).

As previously mentioned, dynamic capabilities are thought to be crucial in situations that place high demands on the degree of reflexivity of organizations (Helfat and Winter 2011). It has however been noted that the nature of multi-organizational settings also places considerable demands on this reflexivity (Sydow and Windeler 1998). Here, matters are complicated by the fact that the individual organizations, as well as their dynamic capabilities, are embedded within the context. It seems likely that not only are these capabilities shaped by the context as it evolves, and in ways that would be unexpected in a more clearly defined setting such as a hierarchy, but also that the capabilities contribute to changes in the context. Moreover, the capabilities of individual organizations may interact and lead to certain aggregate outcomes.

Although the multi-organizational setting places additional demands on organizations’ degree of reflexivity, it must be remembered that the structure of a multi-organizational setting can also facilitate the coordination and adaptation that occurs within the entity (Huxham 1991; Mariotti and Cainarca 1986); Sydow and Windeler 1998; Zenger and Hesterly 1997) The manifold interdependencies between the organizations, their capabilities, and the context are a research area that I wish to begin to understand in this paper.

3 Methods and data

3.1 Research design

My goal is to consider dynamic capabilities in the multi-organizational setting of a particular shopping center and their possible actions across organizational boundaries. This represents a purposefully selected special case for my research, which addresses a phenomenon that has not previously been studied. The Itis shopping center was one of the first in Finland, and with its first expansion it became the largest shopping center in the Nordic countries; a status it later regained through its second expansion. As such, the center has attracted significant media attention, yielding copious newspaper articles and other material upon which my study is founded. In this respect, my case selection for researching a special phenomenon is analogous to the study of Dutton and Dukerich (1991), which analyzed image and identity in New York Port Authority. While multiple-case studies tend to provide a more legitimate base for theory building (Yin 1994), the advantage of studies focusing on single entities lies in their ability to richly describe a phenomenon in a special case (Siggelkow 2007).

I choose to limit the scope of the study to those transformational events in the history of the shopping center that the data indicate to have been among those of greatest significance; I term these the critical transformational events. In this paper, an event is a theoretical construct that is used to connect and explain a number of empirically observed incidents (Abbott 1990; Langley 1999). Several organizations are likely to be involved in or affected by critical events, and thus the multi-organizational nature of the setting is clearly visible. Furthermore, I note that the events that emerge as critical in my research are rather diverse, involving transformations of the infrastructure as well as the services of the shopping center, and as such, they can be seen to provide a cross-section of the various transformations of the setting.

I emphasize that my focus is strictly on certain identified dynamic capabilities, which are considered to be comprised of skills, competencies, and groups of higher-order routines, through which organizations either bring about transformations within a multi-organizational context or respond to such transformations (e.g., Winter 2000). Furthermore, I note that capabilities, like events, are usually not directly observable. Rather, once I have gathered data about the actions of various actors, I evaluate and interpret them and look for patterns resulting from intended actions, and thus recognize capabilities. Once I have identified the relevant capabilities, I analyze their roles within the context and explore how they intertwine to create an aggregate outcome, with the aim of discovering their role in the evolution of the multi-organizational setting.

Identifying the capabilities can be problematic because I usually have only a small sample of observable organizational performances to analyze, and these do not repeatedly produce identical performances. Nevertheless, according to Felin et al. (2012), dynamic capabilities do produce recognizable patterns of interdependent actions carried out by multiple actors. Since I am interested in the patterns of actions brought about as parts of dynamic capabilities, the usual statistical methods, such as averaging, are not suitable. Instead, I follow the suggestion of Pentland et al. (2014), and interview key figures, from which I create flow charts of action patterns that summarize the understanding of specific routines composing the capabilities.

Since the situational variables for how a shopping center is transformed are unique and influenced by the operations of each organization within the specific context, I opt for an embedded multi-case study (Eisenhardt 1989; Yin 1994). The cases in this study are the transformational events, which are all embedded within the multi-organizational setting and its overall development history. The embedded nature of the observed phenomena and their spread across the lifecycle of the center gives the research a strong resemblance to longitudinal process analysis, which is, by definition, used to observe the unfolding of events and processes over time (Langley et al. 2013; Pettigrew 1990). In particular, the entire history of the shopping center can be divided into eras known as phases, which are initiated by or culminate in critical events (Langley 1999). These phases serve as a useful and illustrative way of subdividing the time span under consideration (1970–2012), but as already mentioned, my main focus will be on the critical transformational events. There are several advantages to combining a longitudinal study with a number of individual case studies (Leonard-Barton 1990).

Consistent with this longitudinal approach, I apply an abductive research strategy to extrapolate findings from the data (Dubois and Gadde 2002).. Generally speaking, a deductive approach takes existing theory and develops propositions from it; these can then be tested in the real world. An inductive approach, on the other hand, systematically generates theory from data. An abductive approach is more akin to the inductive approach than it is to the deductive approach, but its focus is on the development rather than the generation of theory (Dubois and Gadde 2002, 2014). More precisely, Dubois and Gadde (2002) talk about systematic combining, which is a process where the “theoretical framework, empirical fieldwork, and case analysis evolve simultaneously”. Thus, one starts with a framework, and then one develops and modifies the framework in line with both the empirical findings and the theoretical insights. In my case, the framework is based on the theories of multi-organizational settings and dynamic capabilities, and my goal is to build theory that combines the two and explains the role of dynamic capabilities in multi-organizational settings.

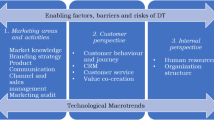

I develop theory based on identified constructs and their relationships, using an approach similar to an inductive case research strategy (Bacharach 1989; Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007). The key constructs in this research include the following concepts: a multi-organizational setting, context, environment, and dynamic capabilities. I identify a large number of dynamic capabilities, and later classify them into three different types: external assessment capability, internal assessment capability, and implementation capability. My research seeks to produce theoretical results on the interplay between the dynamic capabilities of various organizations and the multi-organizational context. The fact that I seek to develop theory rather than test it further justifies my focus on a small number of cases with the potential to illuminate the interactions between the different constructs (Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007).

Although I combine qualitative and quantitative methods in the study (Eisenhardt 1989; Yin 1994), I focus on the former (Miller and Freisen 1982). Hence, I identify and study dynamic capabilities with qualitative methods, only using quantitative methods in the selection of the critical transformational events. I note that a shopping center constitutes a complex multi-organizational setting in which causal dynamics between, say, the capabilities connected to the various critical events are not easily quantifiable (Eisenhardt 1989; Mintzberg 1979). Moreover, since a primary motivation for this study is abductive theory building through theoretical results concerning, for example, the relationship between various dynamic capabilities, a qualitative method is the most natural way of formulating these results. On the other hand, longitudinal process analysis can readily incorporate both qualitative methods (e.g., a description of the historical development of the center) and quantitative methods (e.g., an analysis of the center’s total annual revenue) (Langley et al. 2013).

3.2 Sources of data

Chronology

Altogether, 373 newspaper articles published between 1970 and 2012 were studied and analyzed so as to create a general picture of the lifecycle of the Itis shopping center. The chronology is based on the news archives of Kauppalehti (a commerce-oriented Finnish newspaper owned by Alma Media) and Helsingin Sanomat (the largest subscription newspaper in Finland, owned by Sanoma). I searched for articles with the terms “Itäkeskus” (this is the original name of the center, as well as being the district where Itis is located), “kauppakeskus” (shopping center), and “Itis”. The chronology provided me with an insight into the critical transformational events of Itis, their background, and their impact on the center’s financial success. Even minor changes involving Itis caught the attention of the local media due to the uniqueness of Itis in the market.

Informants

A total of 25 interview sessions were organized, two of which had two respondents and one of which had three. In total, there were 20 different respondents. Informants from all organizations playing key roles in the transformations were included (see Table 1). The newspaper chronology revealed, to some extent, the organizations and other actors involved in the most important transformational events of Itis; individuals who had been in leading positions in these organizations were then chosen for the interviews. However, the selection of respondents became iterative since the interviews themselves provided further information on the central decision makers. In conclusion, most of the respondents had taken part in strategic decisions regarding the critical transformational events of Itis, and had observed its development for more than 25 years. All of the interviews were taped and analyzed.

While interviews are an efficient way of gathering empirical data about unique events, the data may often be biased due to retrospective sensemaking (Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007). One way to avoid this problem is to compare the information given by several knowledgeable informants (Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007). Accordingly, once I had completed the interviews, I compared them, and in cases of contradiction, sent the transcribed interviews back to the respondents for further clarification. Additionally, in order to achieve maximum accuracy and legitimacy, archival data was repeatedly consulted during the interviews. Archival data is particularly suitable for longitudinal process analyses where the development of an entity is being observed over a long period of time (Langley et al. 2013; Langley 1999).

Archival data

The newspaper chronology and the interviews were backed up by figures and quantitative graphs (e.g., on the total annual revenue) demonstrating the changes that have taken place at Itis. The archival data describes the development of the tenant mix and the total revenue of the shopping center. The data on the tenant mix were collected from Itis’s archives for the years 1984, 1985, 1988, 1992, 1995, 1998, 1999, 2002, and 2005–2011. In most cases, successive data points were so similar that the missing data could be extrapolated from the known figures. The areas of the different stores were measured from old floor plans, and stores were divided into 15 different categories in order to provide insight into the internal competition and structural changes at the shopping center. The management of Itis provided the total revenue data and sales figures. In addition, memoranda, transcripts of meetings, copies of old contracts, photographs portraying the participants at contract signings, and the projected cash flow calculations were variously consulted during the interviews.

3.3 Process of data analysis

I began my analysis by creating a narrative description of what had happened in Itis and what roles different organizations played in the overall development. The narrative was primarily based on the collected newspaper chronology, archive materials and a few interviews. During the course of this, the capabilities at play in deciding and assessing the development sparked my interest. At first sight, the different capabilities appeared to be relatively stable. However, I could not identify one higher-order dynamic capability or clear-cut strategy that had orchestrated the overall development. I then realized that the routines constituting the capabilities of individual organizations had evolved within and across the capabilities themselves. Changes in the performance of one capability seemed to lead to changes in the impacts of other capabilities, thereby intertwining the capabilities as a collective logic that determined the development over time. Hence, it felt logical to direct my search towards the mechanisms and capabilities that allowed Itis and the relevant stakeholders to adapt and change during events that were critical to the overall development.

The analysis of the above sources of data prompted my selection of five transformational events in the lifecycle of Itis. I deemed these to be greatly important to the center’s overall development. I do not argue that these events were the most explicitly critical—simply that they were highly important and most certainly had influence on the majority of organizations operating in Itis at the time. These critical events were selected by means of triangulation using three sources of data (Denzin 1978; Jick 1979). First, an overview of the transformational events of the center was created from the newspaper chronology. Second, the impact of specific transformations (construction of new premises, modernization of premises, and introduction of new services) on the lifecycle of Itis was assessed by analyzing the total revenue (see Fig. 1), various sales figures, and the distribution of space in the center taken up by different (key) tenants. Third, several informants gave their opinions as to what were the center’s significant transformational events.

The five critical events that were chosen were as follows: construction, first expansion, Anttila expansion, Stockmann contract, and H&M contract. Three of these five events concern contracts with key tenants, known as anchor tenants (Kirkup and Rafiq 1994; Teller 2008). The composition of the tenant mix is recognized as a shopping center’s most central success factor (Kirkup and Rafiq 1994), especially with respect to its compatibility with the local clientele (Anselmsson 2006; Shim and Eastlick 1998). Analogous to a method used by Langley (1999), the lifecycle of Itis could be divided into four distinctive eras or phases that were initiated by or culminated in the critical events. A timeline for the development of Itis and its four eras is presented in Fig. 1 and briefly described below.

The planning and construction of Itis began the center’s development, and constitute the construction era. After the center opened, plans for expanding it quickly arose; this triggered the expansion era, during which time the concept of malls was imported from the United States. The large premises constructed during the expansion made it possible for major department stores to open in the shopping center, and they became efficient anchor tenants. Consequently, this expanded the services Itis could offer, as these new anchor tenants attracted other tenants and new customers. This phase is referred to as the growth era. The growth era was followed by the internationalization era, which was triggered when H&M showed interest in the Itis premises. Soon after, several international retailers followed H&M’s example and expanded their businesses to Finland.

In the final stage of the analysis, I identified the main dynamic capabilities related to these critical events. To do this, I conducted 20 additional interviews that focused on the role of various capabilities and processes during the events. I targeted my research on specific capabilities by designing a list of semi-structured interview questions that were used throughout the interviews. I prompted interviewees to reflect on the roles different organizations played during these events, as well as on how the interactions were managed. The interviewees were asked for their views on the phases of change undergone by the multi-organizational setting and the individual organizations, and to identify and explain the cause-and-effect relationships related to these changes. Based on these descriptions and a preliminary understanding of the bigger changes that had occurred, I coded the interview data to capture central capabilities related to the service offering. I clustered these specific tasks into three overarching dynamic capabilities that I considered most crucial for the development (namely internal assessment capability, external assessment capability, and implementation capability). Given my theoretical interest in how dynamic capabilities initiate transformation in a multi-organizational setting, I performed an iteration between three main sources: the archive material, my interview data, and the existing literature, in order to further refine the focus of my research and its contribution (Locke 2001).

4 Analysis of the five transformational events

In this section, I separately analyze each critical transformational event. I note that, strictly speaking, each event—for example, the construction of the Itis shopping center—is a theoretical construct that connects and explains a large number of observable and documented incidents, such as meetings between key actor representatives, land purchases, and different phases of the construction work. Somewhat similarly, capabilities can rarely be observed directly; rather, the actions of various companies and actors can be viewed as capabilities if they exhibit a certain repetitive nature and result in an intended outcome. In this section, I mainly limit myself to observing the actions of various actors, avoiding use of the term “dynamic capability.”

4.1 Construction of Itis

The original idea to construct the Itis shopping center dates back to the beginning of the 1970s. At this time, Itäkeskus, an eastern district in the Finnish capital of Helsinki, was a new suburb with a growing population and a need for services. The underground connection between Itäkeskus and the center of Helsinki was constructed during the 1970s, and the original plan was to build a shopping area to provide services at the eastern end of the underground line. This would encourage the local population to use both the new underground line and the new services as part of their daily commute.

The shopping area was intended to have excellent transportation links and so the planning process incorporated good road connections as well as the new underground line. This emphasis on accessibility caused various retail and construction companies to take an interest in the area’s undeveloped land, which was eventually compulsorily purchased by the City of Helsinki and earmarked for development by 17 large construction and retail companies.

The City of Helsinki played an active role in the development of the suburb, hiring several city development consultants, specifically the Niras consultancy, to take the project forward. After benchmarking the trends in the rest of Europe, they came up with the idea of a shopping center. The first plan was to start the construction process in 1975 and open the center by the start of the 1980s. However, the development and construction plans were halted when the oil crisis struck Finland in 1973, causing the country’s GDP to drop drastically.

When Finland began its economic recovery, the plans to construct the shopping center were revived. Not all the companies that had reserved land had objectives in common and so the project was taken forward by four key players: the retail companies Elanto and Anttila, and the construction companies Haka and Polar. Some land exchanges were conducted with other companies in order to connect the land owned by these four players.

As a condition for granting building permission to the construction companies, the City of Helsinki demanded that the services offered by the new center must include a medical center and a movie theater on its premises, and must be served by a large number of parking spaces. This idea was adopted from other European shopping centers. The City of Helsinki also requested that the parking spaces built alongside the shopping center be free of charge to people travelling via the underground line into the city center. The idea was that workers commuting to the city center from farther afield could leave their vehicles at Itis and travel downtown on the underground line. This would alleviate traffic problems downtown and on the roads between Itäkeskus and the city center. This had worked in many other European cities, such as Munich.

The construction process was begun in 1981 by the consortium created by the construction companies Haka and Polar, and the shopping center opened in 1984. In accordance with the trends in the rest of Europe, the retail organizations Elanto and Anttila were placed at opposite ends of the center so as to create customer flows between them. The shopping center turned out to be an immediate success, and the sales of Anttila in particular skyrocketed. Within only two years of opening, it became apparent that the space dedicated to Anttila was insufficient, and it was this that sparked the next phase of development.

The causal relationships among the various events included in the construction phase are summarized in Fig. 2.

4.2 First expansion of Itis

In its original form, Itis was no more than a local shopping center that provided services to the population living in its vicinity. However, the center's success quickly led to expansion plans. Simultaneously, the idea of malls (larger shopping centers) was being imported from the United States to Europe, and many malls were being built in, for example, Great Britain, France, and Spain. There was an abundance of undeveloped land around Itis that had originally been set aside for housing. The construction company Haka had observed the international trend of constructing large shopping centers and noted the excellent traffic connections in the region of Itäkeskus; these factors, combined with the availability of land surrounding the center, presented an excellent business opportunity. The company had a vision that Itis could be the actual center of the eastern suburbs, and that people would travel from a distance to use its services.

The first plans for an expansion were drawn up in 1986. The main challenge presented by the process was to ensure that the premises were of such superb quality that even the most demanding retailers would agree to open their stores in Itis. The ambitious aim was for the premises to meet the demands of customers and retailers 20 years into the future. In order to avoid mistakes, several benchmarking trips were organized abroad to inspect the new shopping centers in Great Britain, Spain, France, the United States, and Canada. For example, the idea of constructing a large boulevard area inside the center and decorating it with various pieces of sculpture and artwork originated abroad.

The department store Anttila had been very successful in the original version of the center, and it was eager to expand. A pre-contract was signed with Anttila to bind this important future anchor tenant to the project, thus reducing risks. The Itis branch of Anttila was to triple in size during the expansion, making Anttila an important anchor tenant. Later on (but before the expansion was completed), another major department store, Stockmann, signed a contract with the management of Itis. Finally, a third department store, Sokos, also decided to open a store in the shopping center, though it rented a slightly smaller space than the other two stores. Together, these three department stores would occupy approximately 40% of the available premises at Itis. Throughout the expansion process, there was an active search for other strong anchor tenants. However, the remoteness of Finland meant that almost all of the international retail chains approached by the Itis management were uninterested. Nonetheless, the contracts with Anttila and Stockmann increased Itis's attractiveness to smaller Finnish retail organizations, and the remaining units were filled fairly quickly.

The new expanded center was opened in 1992, just before full might of the early 1990s recession was unleashed. Itis can be considered to have been extraordinarily fortunate in having actively sought out and signed several tenancy agreements during the expansion phase. If there had been a delay of only one or two years, tenants would have been much more difficult to find. This success can be considered critical in the history of the center.

4.3 Anttila contract for store expansion

Before its expansion at Itis, the Anttila department store had catered for a low-end market; this strategy had proved very successful in the original version of the center. However, Anttila soon outgrew its Itis footprint. Furthermore, around the time Itis was expanding, several new discount stores were joining the market, and Anttila had to make a choice between competing with them or finding a different market. These new cheap concept stores were building their premises in various retail parks that had started to pop up in the suburbs. The new leases at Itis and other central areas could not compete on price with those being offered by these suburban retail parks, and Anttila’s organizational strategy had to be modified. In a complete volte face, Anttila decided to choose the more expensive locations in central areas and shopping centers, with a view to upgrading the image of its department stores. In a shopping center environment, it is important for a store to differentiate itself from its competitors operating in the same context, but Anttila was able to find a market niche by finding good locations in which to sell (comparatively) cheap goods that were not always sold by the high-end stores, Stockmann and Sokos. Anttila was developing this concept at the time Itis was expanding and it soon opened several large stores in Finland.

The expansion of Itis could not have proceeded without the pre-contract with Anttila due to the latter’s important role in the planned context of Itis. Since Elanto was struggling and had to leave Itis in 1993, and the situation with Stockmann was not secure, Anttila was potentially the only true anchor tenant at that time. The purpose of the pre-contract was also to enable Anttila’s involvement in the planning and construction phases, allowing it to have input into the refurbishment of the premises. By the time the Itis expansion was almost complete, Finland was experiencing serious signs of recession and Anttila was struggling with its many simultaneous investments. Since Anttila had completed only a pre-contract with Itis, there remained the possibility of further negotiations. These negotiations resulted in modifications to the terms of the contract, allowing the rent to be adjusted according to the store’s sales. The idea for the profit-dependent price levels for the rents had originated from the negotiations between Itis and Stockmann, as the latter was not willing to enter the center with a fixed rent agreement. Since Anttila had doubts about its ability to expand, it was justified in seeking a similar contract.

On the other hand, the fact that Stockmann was also interested in Itis was an important factor in Anttila’s willingness to sign a tenancy agreement. The three large department stores that would be opening at the shopping center would create a tough competitive situation. However, Anttila management concluded that Sokos would quickly fall out of the competition because it shared a common customer base with Stockmann. By contrast, the sufficiently distant concepts of Stockmann and Anttila would enable them to profit from each other’s presence in the center. Anttila carefully assessed Stockmann’s strengths and tailored its own product range accordingly. For example, Stockmann had a high reputation for their extensive shoe offering, so Anttila decided not to have a shoe department in Itis. Stockmann catered for a high-end clientele, and the store would provide Itis customers with the more luxurious goods. Anttila would then provide the cheaper goods. The predictions of the Anttila management proved correct: Sokos left Itis in 1997, whereas Anttila and Stockmann thrived.

4.4 Stockmann contract

There were several attempts made by the management of Itis to enter into a pre-contract with Stockmann even before the expansion work had begun. Stockmann was known to be a very successful Finnish retail chain, and having their store on the premises would guarantee a certain level of customer flow. However, Stockmann already had a large department store in the vicinity, and entering the shopping center context of Itis was not part of its strategy. Rental negotiations with various other retail chains were being conducted while the construction work was going on, but no tenant could be found who needed a unit as large as the one available. Thus, once the building work had been completed, the center’s management offered Stockmann a contract with extremely attractive rental terms, which Stockmann accepted. According to the interviews, Stockmann had used delay as a negotiating tactic, enabling the company to use its strong market position to secure a very profitable pre-contract with Itis.

Despite the favorable terms of the pre-contract, Stockmann proved to be a demanding tenant and stipulated many requirements that had to be fully met. For example, according to the interviews, Stockmann placed an embargo on some of its competitors being accepted at certain locations in the Itis shopping center. This capricious behavior prompted the construction contractor, Haka, and the management of Itis to proceed with caution. However, Stockmann’s was one of the expansion’s anchor tenants and there had already been significant financial outlay on the customized fixtures and fittings for its store. It was therefore vital to keep Stockmann happy.

Indeed, Stockmann proved to be an extremely important tenant for Itis, who benefitted from the store’s branding and market segment. The Stockmann contract has enabled Itis to differentiate itself from many of the competing shopping centers right up to the present day. Reciprocally, Stockmann has been highly satisfied with its decision to open a store at Itis. Early on, Stockmann’s main competition within the center was the department store Sokos; however, Sokos had a far smaller footprint and could not compete with Stockmann in terms of the quality and variety of the brands of stocked. As a result, Sokos left Itis by the end of 1997. Stockmann and Anttila, on the other hand, were able to complement each other by appealing to sufficiently distinct market segments. The premises that had been vacated by Sokos were taken over in 1997 by a company whose arrival significantly enhanced the tenant mix at Itis and heralded the center’s internationalization phase: H&M.

4.5 Hennes & Mauritz contract

Hennes & Mauritz AB is a Swedish multinational retail organization that sells clothes and accessories. It was founded in 1947 and it first expanded outside of Sweden by opening a store in Norway in 1964. In 1974, after several years of rapid growth, H&M was quoted on the Swedish stock exchange. Its international expansion advanced with the opening of the first H&M store in Denmark. Once the exporting of the concept had proved successful, expansion proceeded at a steady pace that continues to the present day. By the beginning of the 1990s, H&M was an internationally recognized and desirable brand; it had also caught the attention of the management of Itis, who were actively searching for anchor tenants.

H&M can be considered to be a perfect anchor tenant for a shopping center. The customer volume at an individual H&M store exceeds that of its competitors, generating increased customer flow for its host shopping center. The store also generates sales volumes that are higher than average because of the constantly changing product selection, the stores’ prime locations, and their modern, always on-trend shopping environment.

The negotiations between H&M and Itis had already begun during the first expansion of the center in 1991. During this time, there was an active search for good anchor tenants and, according to the interviews, Itis would have been prepared to increase the competitiveness of its premises by making heavy modifications to meet H&M’s probable demands. However, H&M was more interested in other markets at the time (namely, the United States, Spain, and Great Britain) and it was not looking to expand into Finland.

Between 1991 and 1997, the management of Itis had several meetings with representatives of H&M. The initiative for these negotiations came from Itis's management, who were keen for their shopping center to be the first in Finland to have H&M on its premises. During this period of negotiation, H&M was growing rapidly and actively searching for business opportunities in many countries and cities. However, H&M was still reluctant to expand into Finland, partly because it was committed to its (successful) strategy of simultaneously opening several stores in each new country, which naturally required the several suitable premises to be available.

In 1997, H&M had completed its expansion in the more tempting countries, and by then a number of good premises had become available in Finland. Itis was a particularly desirable setting for H&M because the excellence of the center’s anchor tenants (Stockmann and Anttila) guaranteed abundant customer flows. Thus, the first H&M store in Finland opened in Itis in 1997, in a prime location that had just been vacated by Sokos. Within the wider contexts of the City of Helsinki and the country as a whole, one factor that made suitable premises more available at this time had to do with a change in the service structure of Finland’s banks during 1997 to 1999, when various activities were shifted online. As a result, several large banks divested themselves of their expensive premises in downtown Helsinki, leaving the sites vacant. Only two weeks after the launch of the store in Itis, a large H&M store opened in downtown Helsinki in a location previously occupied by a bank. Shortly after, H&M opened several stores across the country at a rapid pace, in accordance with its expansion strategy of fast market penetration.

At the time H&M opened its doors in Itis, it was the most notable international retailer in the Finnish market, and it remains one of the center’s most important anchor tenants. According to the interviews, H&M’s strong market position enabled it to all but dictate the terms of its tenancy contract. The rent was set very low, but Itis management correctly estimated that the increased customer flow would more than compensate for the lost rental income. In addition, H&M attracted several other international retailers to the center, starting the era of internationalization at Itis and other Finnish shopping centers.

The causal relationships among the various events included in the expansion, growth, and internationalization phases are summarized in Fig. 3.

5 Synthesis and development of results

This description of the critical transformational events enabled me to identify several distinct capabilities connected to these events. In the following section, I analyze and classify these capabilities and produce five theoretical results that play a role in the transformations of a multi-organizational setting. In this analysis, I focus specifically on either dynamic capabilities—the existence of capabilities by which organizations either bring about transformations or respond to them—or the lack thereof.

5.1 Analyzed capabilities

Three types of dynamic capabilities were consistently observed in the five critical events in the development of Itis. I term these dynamic capabilities the external assessment capability, the internal assessment capability, and the implementation capability. In some cases, an action performed by a given actor occurred repeatedly in the data, warranting the label “capability,” whereas in other cases the routine-like nature of an action was communicated in, for example, the interviews.

I note that interpreting repeated actions as capabilities constitutes the first step in theory building, although the other steps will become evident as I develop my theoretical results. Eisenhardt and Graebner (2007) emphasize the importance of tying the development of theory in with the case data, whereas Pratt (2009) recommends that the reader should be given the chance to draw his or her own conclusions from the data gathered during the research process. Accordingly, in Table 1 I provide many quotes from the interviews to illustrate and justify my interpretation of various higher-order capacities or dynamic capabilities.

External assessment capability

The term external assessment capability refers to an organization’s continuous assessment of its surroundings—I note that from the standpoint of an individual organization in a multi-organizational context, the word “surrounding” can refer both to the multi-organizational context and its environment, as defined earlier. When the external assessment is directed towards the competitors of an organization, it is called benchmarking.

The data reveal that the external assessments conducted by the management of Itis, the consultant company Niras, and the City of Helsinki all played a crucial role in the development of the center. During the construction and expansion eras, the assessments could be characterized as ad hoc, and were driven by a desire to gain insight into unfamiliar processes. During these eras, many of the innovations introduced at Itis, such as the large boulevard area or the concept of filling a significant portion of the premises with department stores, were new to the Finnish retail market and needed to be imported from abroad.

As the competition in the Finnish retail market grew, the size and context of Itis also developed, and an external assessment capability became perhaps one of the most critical success factors in the development process—this became an habitual routine and an integral part of the constantly ongoing processes. For example, realizing the profitability of taking on H&M, at a very low rent, was the result of the international benchmarking of other shopping centers. Moreover, benchmarking was similarly directed at the domestic retail market. As a result of this external assessment, Itis emerged as a competitive context where each tenant had a carefully planned role.

In addition to the external assessment conducted by the management of Itis, all of the transformational events have also been influenced by one or several of the other organizations involved in the multi-organizational setting, and their external assessment capabilities. Prior to being attached to the project, the construction companies Haka and Polar were conducting an ongoing search for new business opportunities. They had an eye to the city’s development plans and were also monitoring developments in the market. The decision taken by Anttila to expand its store at Itis and boost its image was a result of the benchmarking of both the environment—for example, observing the emergence of cheap concept stores in retail parks—and the multi-organizational context of Itis; in particular, the decision took into account the other two department stores at Itis, Stockmann and Sokos. H&M conducts a constant external assessment of the availability of suitable premises, and it entered Itis when such premises became available.

Internal assessment capability

The term internal assessment capability refers to an organization’s or other actor’s capacity to make assessments within its own boundaries. For example, the realization by the department store Anttila that it had outgrown its retail unit at Itis can be considered the product of an internal assessment capability, which ultimately led to the expansion of the department store during the center’s first expansion. Originally, the idea to construct the Itis shopping center was initiated by an internal assessment conducted by the City of Helsinki; this assessment revealed the need for services in the district of Itäkeskus.

Likewise, in the rivalry between the three department stores Anttila, Stockmann, and Sokos, the internal assessment capabilities of Anttila played a key role in its success against its tough competition. Without the capability to clearly assess its own product range, Anttila would not have been able to simultaneously differentiate itself from both Stockmann and the cheap concept stores outside of Itis. In contrast, Sokos lacked the kind of assessment routine that would have enabled it to make the necessary adaptations through shifts in its product range.

From the standpoint of the management of Itis, the term “internal” refers to the entire multi-organizational context. The poor performance of Sokos in the competition between department stores was not solely a concern for Sokos, but was also an issue for the management of It is, who which needed to find new tenants to fill the premises previously occupied by Sokos. In this sense, internal assessment is particularly complicated for the management of a multi-organizational setting since it must take into account the complex interactions between the individual organizations (cf. Sydow and Windeler 1998).

Implementation capability

I use implementation capability as a general term that encompasses more specific actions, such as the skills and routines related to negotiations and decision-making capacities. Broadly speaking, the implementation capabilities of an organization can guide its actions once relevant information has been gained via the external and internal assessment capabilities. Felin and Powell (2016) also note that the range of resources—for example, information—produced by capabilities can determine what schemas and actions are implemented. For example, once the City of Helsinki had assessed that there was a need for new services in the district of Itäkeskus, the service requirements it imposed on the new shopping center can be seen as manifestations of the city’s urban planning capability.

In a multi-organizational setting such as Itis, transformational events are ultimately the outcome of a complex interplay between the implementation capabilities of various organizations. During the construction phase and the first expansion of Itis in particular, there were constant negotiations between the management of Itis and the center’s prospective tenants. The data reveal that the negotiation routine of the Itis management underwent significant changes as the context of the shopping center developed and competition in the market grew. Early in its history, Itis was the only true shopping center in Finland, and as such, it was a highly desirable location that could easily attract tenants. However, soon the ability of strong tenant organizations, such as Anttila and Stockmann, to increase the profitability of the shopping center as a whole provided these organizations with bargaining power with respect to their tenancy negotiations. Seeking to develop the entire context, the management of Itis offered premises to these anchor tenants for cheap rents, with the knowledge that the loss in rental income would be compensated for by an increase in the sales of other organizations. During the first expansion of the center, the concept of signing pre-contracts with future anchor tenants in order to bind them to the project and reduce risks was also central to the center’s negotiation strategy.

The negotiation capabilities of the management of Itis were once again challenged a few years later by H&M’s own practices. The corporate practices of global tenants like H&M set strict guidelines for organizational changes and new business opportunities. Therefore, the management of a shopping center needs to take into account these unique organization-specific features. This is perfectly demonstrated by the long negotiation process between Itis and H&M, which saw the introduction of H&M’s global strategies into a local context. In order to satisfy the requirements set by H&M, the management of Itis had to alter the shopping center context by, for example, refurbishing the premises. However, even this compliance was deemed insufficient, as the fast market penetration strategy of H&M requires the availability of several suitable premises within the same country. Hence, the management of Itis went so far as to assist H&M to find other premises at competing shopping centers. The three critical transformational events that involved the contracts with the three anchor tenants, Anttila, Stockmann, and H&M, indicate that the less coherence there is between the business strategies of the shopping center and the tenant, the more flexibility will be required in the actions of the shopping center management.

In Table 2 I summarize the roles the three different types of capabilities have played in shaping the multi-organizational setting of Itis.

5.2 Development of theoretical results

In this section, I provide five theoretical results on the relationships between the individual organizations, their capabilities, and the context of a multi-organizational setting, with reference to the analysis of the development of the Itis shopping center.

The earlier descriptions of the three types of dynamic capabilities indicate that they exert a strong influence on the multi-organizational setting. They can even be considered to have started the different eras in the Itis lifecycle. For example, the expansion era was largely started by Anttila’s internal assessment capability, which revealed the need for larger premises, as well as by the benchmarking capability of the management of Itis and the consultant company Niras. These capabilities and their implementation formed a chain reaction, where one step triggered the next, leading to a profound change in the entire context and the organizations within it. Thus, I offer the following result:

-

Theoretical result 1: Dynamic capabilities create links between organizations’ actions and reactions, creating the potential for transformations in the entire multi-organizational setting.

The data indicate that the context has also influenced the organizations operating within the multi-organizational setting of Itis. Thus, it has been vital for every individual organization to monitor contextual changes that, according to Theoretical result 1, may have been caused by the capabilities of other organizations. Crucially, these changes may have been brought about by internal imbalances in the setting, and thus they may be detrimental to a given organization. A prime example of this can be seen in the superfluity of department stores at the outset of the expansion phase, and the inability of Sokos to compete with Anttila and Stockmann in this situation. This leads me to my second result.

-

Theoretical result 2: While a dynamic capability may produce the intended benefits for certain organizations operating in a context, it may place others in jeopardy.

It is known that the ability to adapt to change creates an organization's competitive edge (Eisenhardt and Martin 2000). The literature on multi-organizational settings (e.g., Sydow and Windeler 1998) states that these settings are, to a large extent, self-organizing entities where individual organizations can adapt to various impacts. My data also indicate that while the dynamic capabilities of some organizations can at times bring about changes in the context, those of other organizations determine the situational responses to the potential changes. Hence, seemingly similar (dynamic) capabilities may produce varying impacts at different times. For example, when the department stores Sokos and Stockmann entered Itis during the first expansion of the center, Anttila’s external assessment capability and its capacity to differentiate itself through its product range enabled it to respond to the changed situation, whereas the dynamic capabilities of Sokos were insufficient for identifying the need to adapt or how to do so. Hence, the third result.

-

Theoretical result 3: To maintain a competitive edge, organizations need suitable dynamic capabilities with which they can respond to transformations in the context.

This also indicates that individual organizations operating in and involved with a multi-organizational setting require dynamic capabilities and that these are necessary for the long-term sustainability of the entire entity; this is the question of interest in a longitudinal study such as this. The aforementioned capabilities of Anttila, for example, contributed to the success of Itis, which was able to adapt so effectively, it retained for several decades its position as the leading shopping center in Finland.

Previous studies on dynamic capabilities involving several organizations have either dealt with situations where the organizations have directly interacted with one another, such as through strategic alliances (Zollo et al. 2002), or situations where organizations have interacted with their operating environment (e.g., Zott 2003). In my research, I have focused on a multi-organizational setting where the organizations and their capabilities are connected indirectly through the context (Sydow and Windeler 1998). For example, the negotiation capabilities of the department stores Anttila and Stockmann prior to the first expansion of Itis were influenced by each other in the sense that once Stockmann had demanded profit-related rents, Anttila made a similar demand. While Theoretical result 1 suggests that organizational capabilities create the potential to influence the context in which the organizations operate, and Theoretical results 2 and 3 suggest that a contextual change influences the organizations that operate within a particular context through the capabilities of these organizations, there is also a fourth result, which I offer now.

-

Theoretical result 4: The dynamic capabilities of organizations operating in the same context may create links between their actions through the context itself, even though the organizations do not directly interact with each other. Together these capabilities are intertwined to create an aggregated collective logic.

The work by Sydow and Windeler (1998) and Huxham (1991) suggests that multi-organizational settings operate very differently from both markets and hierarchies, especially in terms of the fact that they combine cooperative and competitive elements, autonomy and dependence, and trust and control. Similarly, my data and my first four theoretical results reveal examples of organizations within the multi-organizational setting of Itis both competing with each other and benefiting from each other’s existence. However, it seems that in the majority of these connections, one party is one of a few central organizations and actors.

In the case of Itis, the central organizations and actors include or have included the management of the center itself, the consultant company Niras, the construction companies Haka and Polar, the City of Helsinki, and most interestingly the anchor tenants. The most important anchor tenants in the history of Itis have been Anttila, Stockmann, and H&M. When Anttila expanded its store and Stockmann entered Itis during the first expansion of the center, numerous other retail organizations began to show an interest in Itis, and 97% of the units had been filled before the expansion had been completed. Later, H&M attracted many more tenants to Itis, including several international retailers. For example, the number of international apparel and shoe stores increased by 450% within a few years of H&M’s arrival at the center.

In short, it seems that the few central organizations readily form symbioses and other connections with the numerous other organizations in the multi-organizational context, and thus the dynamic capabilities of the central organizations can initiate waves of change throughout the entire context, possibly even resulting in a critical transformational event. Thus, I offer a fifth and final result.

-

Theoretical result 5: Critical transformational events in a multi-organizational setting are often brought about by the dynamic capabilities of a few central organizations and their interplay with the numerous other organizations within the context.

5.3 Managerial implications

My theoretical results have several implications for practitioners. In these I focus specifically on the management and coordination of multi-organizational entities, because it is this aspect that promises to yield the greatest novelty; the management of individual organizations, whether they are parts of a multi-organization setting or not, is naturally better suited to studies focusing specifically on them.

In my examination of the entire multi-organizational setting, I propose that it is important not only to view such settings as portfolios of static offerings, but also as agglomerations of organizations with individual characteristics. Even then, from the managerial perspective, it is not sufficient to simply cobble together an apparently suitable group of organizations; one must take into consideration their inter-organizational connections and their resulting ability to adapt as a dynamic entity. In my specific setting of a shopping center, the tenant with the highest sales or the apparently best offering at a given moment may not turn out to be the best tenant in the long run; for example the department store Sokos had excellent sales figures in its stores elsewhere, but in Itis it failed to find a suitable niche. By contrast, Anttila was able to adapt in various ways, such as by discontinuing its shoe store when other retailers with superior selections entered the context. The success and sustainability of Itis across several decades was determined largely by its ability, in most cases, to select suitable tenants that helped the entire entity adapt and thrive in the long run. It is therefore evident that an important factor in the success of a multi-organizational setting lies in its ability to identify the capabilities of the organizations that constitute it.

6 Conclusions and further research

In this paper, I have addressed the following research question: How do dynamic capabilities function in the transformation of a multi-organizational context? I have applied an abductive research approach, using the shopping center Itis as the multi-organizational setting under study, and produced five theoretical results on the dynamic capabilities associated with the transformational events that take place within the context of a shopping center. The results are novel in the scholarship of dynamic capability research, and the theoretical results I introduce serve as a basis for further research and theory building concerning dynamic capabilities in complex organizational settings.

In earlier studies, researchers have considered dynamic capabilities as sources of connections, understanding, and change within a particular organization or alliance (Felin and Powell 2016; Zollo et al. 2002). By contrast, and in response to the call to take dynamic capability research to the multi-organization or multi-market level (Schilke et al. 2018) I have identified connections between the context, the individual organizations, and their capabilities in a multi-organizational setting, intertwining them into a collective aggregated logic that has guided past transformations. In practical terms, my results contribute to the understanding of the role of dynamic capabilities in multi-organizational settings, providing insight for their management and coordination.

As my focus has been limited to one specific multi-organizational setting, it is natural to envision further research in other settings. Understanding dynamic capabilities in multi-organizational settings is a wide topic, with many avenues for future research. Multi-organizational settings clearly pose significant challenges to the dynamic capabilities of organizations, and many of the findings will be context-specific. There is much to be understood about what might comprise the capabilities in such settings, what determines their impact (i.e., when are the capabilities dynamic), and how they evolve and intertwine over time. In my Theoretical result 4 and the lead-up to it, I observed some of this intertwining, but this was mostly a matter of one organization’s dynamic capability influencing that of another in a rather coincidental way. It is however likely that such organizational learning can occur in other, possibly more systematic, ways. Overall, in many of my theoretical results I observed various causal relationships, suggesting a need for further longitudinal studies to validate the interpretation of correlational evidence as causality.

References

Abbott A (1990) A primer on sequence methods. Organ Sci 1(4):375–392

Anselmsson J (2006) Sources of customer satisfaction with shopping malls: a comparative study of different customer segments. Int Rev Retail Distrib Cust Res 16(1):115–138

Bacharach SB (1989) Organizational theories: some criteria for evaluation. Acad Manag Rev 14(4):496–515

Bengtsson M, Kock S (2014) Coopetition—quo vadis? Past accomplishments and future challenges. Ind Mark Manage 43(2):180–188

Brass DJ, Galaskiewicz J, Greve HR, Tsai W (2004) Taking stock of networks and organizations: a multilevel perspective. Acad Manag J 47(6):795–817

Child J, McGrath RG (2001) Organizations unfettered: organizational form in an information-intensive economy. Acad Manag J 44(6):1135–1148

Denzin NK (1978) The research act, 2nd edn. McGraw-Hill, New York

Dubois A, Gadde LE (2002) Systematic combining: an abductive approach to case research. J Bus Res 55(7):553–560

Dubois A, Gadde LE (2014) “Systematic combining” – a decade later. J Bus Res 67(6):1277–1284

Dutton J, Dukerich J (1991) Keeping an eye on the mirror: image and identity in organizational adaption. Acad Manag J 34(3):517–554

Eden C, Huxham C (2001) The negotiation purpose in multi-organizational collaborative groups. J Manage Stud 38(3):351–369

Eisenhardt KM (1989) Agency theory: an assessment and review. Acad Manag Rev 14(1):57–74

Eisenhardt KM, Graebner ME (2007) Theory building from cases: opportunities and challenges. Acad Manag J 50(1):25–32

Eisenhardt KM, Martin J (2000) Dynamic capabilities: what are they? Strateg Manag J 21(10–11):1105–1121

Felin T, Powell TC (2016) Designing organizations for dynamic capabilities. Calif Manag Rev 58(4):78–96

Felin T, Foss NJ, Heimeriks KH, Madsen TL (2012) Microfoundations of routines and capabilities: individuals, processes, and structure. J Manage Stud 49(8):1351–1374

Grandori A, Soda G (1995) Inter-firm networks: antecedents, mechanisms and forms. Organ Stud 16(2):183–214

Helfat CE, Peteraf MA (2015) Managerial cognitive capabilities and the microfoundations of dynamic capabilities. Strateg Manag J 36(6):831–850

Helfat CE, Winter SG (2011) Untangling dynamic and operational capabilities: strategy for the (N)ever-changing world. Strateg Manag J 32(11):1243–1250

Helfat E. C., Finkelstein S., Mitchell W., Peteraf A. M., Singh H., Teece J. D. and Winter G. S. (2007). Dynamic capabilities: Understanding strategic change in organizations. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Huxham C (1991) Facilitating collaboration: issues in multi-organizational group decision support in voluntary informal collaborative settings. J Oper Res Soc 42(12):1037–1045

Huxham C, Beech N (2003) Contrary prescriptions: recognizing good practice tensions in management. Organ Stud 24(1):67–91

Jick TD (1979) Mixing qualitative and quantitative methods: triangulation in action. Adm Sci Q 24(4):602–611

Kirkup M, Rafiq M (1994) Managing tenant mix in new shopping centres. Int J Retail Distrib Manag 22(6):29–37

Langley A (1999) Strategies for theorizing from process data. Acad Manag Rev 24(4):691–710

Langley A, Smallman C, Tsoukas H, Van de Ven A (2013) Process studies of change in organization and management: unveiling temporality, activity, and flow. Acad Manag J 56(1):1–13

Leonard-Barton D (1990) A dual methodology for case studies: synergistic use of a longitudinal single site with replicated multiple sites. Organ Sci 1(3):248–266

Levinthal DA (1991) Organizational adaptation and environmental selection-interrelated processes of change. Organ Sci 2(1):140–145

Levinthal DA, Marino A (2015) Three facets of organizational adaptation: selection, variety, and plasticity. Organ Sci 26(3):743–755

Locke K (2001) Grounded theory in management research. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

MacMillan K, Farmer D (1979) Redefining the boundaries of a firm. J Ind Econ 27(3):277–285

Mariotti S, Cainarca GC (1986) The evolution of transaction governance in the textile-clothing industry. J Econ Behav Organ 7(4):351–374

Miller D, Freisen PH (1982) Innovation in conservative and entrepreneurial firms: two models of strategic momentum. Strateg Manag J 3(1):1–25

Mintzberg H (1979) An emerging strategy of “direct” research. Adm Sci Q 24(4):580–589

Nelson RR, Winter SG (1982) An evolutionary theory of economic change. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Paavola LJ, Cuthbertson RW (2018) Routines as drivers of adaptation, incremental change and transformation. Acad Manag Proc 2018(1):15686

Pentland BT, Hœrem T, Hillison D (2014) Comparing organizational routines as recurrent patterns of action. Organ Stud 31(7):917–940

Pettigrew A (1990) Longitudinal field research of change: theory and practice. Organ Sci 1(3):267–292

Pisano GP (2017) Toward a prescriptive theory of dynamic capabilities: connecting strategic choice, learning, and competition. Ind Corp Chang 26(5):747–762

Pratt MG (2009) For the lack of boilerplate: tips on writing up (and reviewing) qualitative research. Acad Manag J 52(5):856–862

Schilke O, Hu S, Helfat CE (2018) Quo vadis, dynamic capabilities? A content-analytic review of the current state of knowledge and recommendations for future research. Acad Manag Ann 12(1):390–439

Schilling MA, Steensma HK (2001) The use of modular organizational forms: an industry-level analysis. Acad Manag J 44(6):1149–1168

Shim S, Eastlick MA (1998) The hierarchical influence of personal values of mall shopping attitude and behavior. J Retail 74(1):139–160

Siggelkow N (2007) Persuasion with case studies. Acad Manag J 50(1):20–24

Stringer J (1967) Operational research for “multi-organizations.” Oper Res Q 18(2):105–120

Sydow J, Windeler A (1998) Organizing and evaluating interfirm networks: a structurationist perspective on network processes and effectiveness. Organ Sci 9(3):265–284

Teece DJ (2007) Explicating dynamic capabilities: the nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg Manag J 28(13):1319–1350

Teece DJ (2018) Business models and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Plan 51(1):40–49

Teece DJ, Pisano G, Shuen A (1997) Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg Manag J 18(7):509–533

Teller C (2008) Shopping streets versus shopping malls–determinants of agglomeration format attractiveness from the consumers’ point of view. Int Rev Retail Distrib Consum Res 18(4):381–403

Teller C, Alexander A, Floh A (2016) The impact of competition and cooperation on the performance of a retail agglomeration and its stores. Ind Mark Manage 52(1):6–17

Tsoukas H, Chia R (2002) On organizational becoming: rethinking organizational change. Organ Sci 13(5):567–582

Wang CL, Ahmed PK (2007) Dynamic capabilities: a review and research agenda. Int J Manag Rev 9(1):31–51

Winter SG (2000) The satisficing principle in capability learning. Strateg Manag J 21(10–11):981–996

Winter SG (2003) Understanding dynamic capabilities. Strateg Manag J 24(10):991–995

Yin RK (1994) Case study research – design and methods, second edition. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Zenger TR, Hesterly WS (1997) The disaggregation of corporations: selective intervention, high-powered incentives, and molecular units. Organ Sci 8(3):209–222

Zollo M, Reuer JJ, Singh H (2002) Interorganizational routines and performance in strategic alliances. Organ Sci 13(6):701–713