Abstract

This paper studies the effect of Morningstar ratings on fund flows and fund performance predictability using a proprietary data set of equity funds from Norway. Controlling for a number of variables proxying for fund and firm visibility, we find that fund flows respond asymmetrically to changes in Morningstar ratings. Specifically, 4- and 5-star rated funds get more flows, and funds upgraded to 5-star get significantly more flows not only in the next month, but also over the following 12 months after the rating change. Downgraded funds suffer outflows, but the results only become statistically significant when fund performance falls to a 2-star rating. We also find evidence of long-term performance predictability for top-rated funds. As the mutual fund industry develops worldwide, our results suggest that Morningstar has been successful in bringing its brand name to markets outside the USA, and that Morningstar ratings are a valuable tool for helping investors make strong investment decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

At the end of 2019, the world mutual fund industry managed financial assets of nearly $53 trillion, nine times the $6 trillion managed at the end of 1996 (Investment Company Institute 2020). The number of funds has also increased dramatically, to almost 137,000 funds. This growth has been registered worldwide, and particularly in the mutual fund industry outside the USA, where the share of assets under management grew from 38% in 1996 to 52% in 2019.

The bulk of the literature on fund flows has focused on flow-performance sensitivity. In the USA, the literature shows that this relation is convex, as investors flock disproportionately to the best performers and fail to sell poorly performing funds (e.g., Ippolito 1992; Sirri and Tufano 1998; Del Guercio and Tkac 2002). Dahlquist et al. (2000) and Keswani and Stolin (2008) also find a convex flow-performance relationship in Sweden and in the UK, respectively. Ferreira et al. (2012) show that the flow-performance relationship varies across countries, depending on the level of participation costs in the fund industry and on how sophisticated investors are. Search costs and participation costs also affect the flow-performance sensitivity, as its convexity is more pronounced among funds with higher search costs (Sirri and Tufano 1998) and participation costs (Huang et al. 2007).

At the end of 2019, Australia is the sixth largest mutual fund industry in the world by assets under management, and the Australian mutual fund industry represents 30% of the assets under management in the Asia-Pacific region (EFAMA 2020).

Despite the fast growth of China’s financial markets observed in recent years, there are still fundamental differences between the USA and China mutual fund industries and overall capital markets. The mutual fund industry in China only started in 2001, while, in the USA, the first open-end mutual fund was created in 1924 (Khorana et al. 2005). Additionally, mutual funds in China present unique features, including high risk and a rather low performance persistence compared to that observed in U.S. funds (Jun et al. 2014), and, China’s unique regulatory system also affects investor allocation decisions.

Different studies show that many of the most stylized facts observed in the US fund industry do not apply to other mutual fund industries. For example, Ferreira et al. (2019) find that differences in competition in the mutual fund industry explain considerable variation in performance persistence levels across countries, while Ferreira et al. (2012) find marked differences in the flow-performance relationship across countries, suggesting that the documented convexity in the U.S. literature does not apply universally. Additionally, Keswani et al. (2020) show that cultural influences are likely to be as important as institutional, financial and macroeconomic influences in explaining differences in mutual fund conduct across countries.

It was only in 1993 the starting year of the open-end fund industry in Norway (Khorana et al. 2005).

The average monthly flow across funds in our sample is 0.11%.

For detailed information on the Morningstar rating methodology, see: https://www.morningstar.com/content/dam/marketing/shared/research/methodology/771945_Morningstar_Rating_for_Funds_Methodology.pdf.

Morningstar changed their methodology in 2002 by introducing a new improved risk-adjusted return measure and new peer groups. Blume (1998) presents a detailed description of the rating system used from 1996 to 2002. Our sample starts in 2003 and, therefore, this change does not affect our results.

In October 2006, Morningstar introduced the 5-year and 10-year rating to Europe; thus, the current European overall rating is based on the weighted average of the 3-, 5- and 10-year rating. Previously, the overall rating in Europe was only based on the 3-year rating. This change has no impact on our results.

We impose all funds in our sample to have a complete rating history and also to have data on all explanatory variables. There are several reasons why some funds have an incomplete rating history, such as inception date, rating suspension, or category change.

To ensure that extreme values do not drive our results, we winsorize fund flows at the bottom and top 1% level of the distribution.

To examine whether the effect of upgrades and downgrades persists, we also compute cumulative flows for the next 3, 6, and 12 months (Flows(t,t+x), where x = 3,6 and 12) after the rating change.

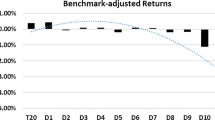

In untabulated results, we also use benchmark-adjusted returns and that does not change the tenor of our main results.

Factors are from AQR Capital Management: https://www.aqr.com/Insights/Datasets.

We winsorize fund performance at the bottom and top 1% level of the distribution.

The TNA managed by fund management companies affiliated with a top brand Scandinavian bank represents 28% of the TNA in our sample at the end of 2019.

Keller (1993) presents different financial benefits of creating a strong brand, including greater customer loyalty, less vulnerability to marketing actions from competitors and marketing crises, more inelastic consumer response to price increases, greater trade support and cooperation, and increased opportunities for marketing communication effectiveness, licensing, and brand extensions.

In untabulated results we obtain similar results when computing ranks based on fund’s performance in the prior 36 months.

We include dummy variables indicating Morning star rating grades from 2- to 5-star. This means that the intercept provides the impact on flows for 1-star funds; thus, the coefficients of the dummy variables measure the marginal flows with respect to 1-star rated funds.

In untabulated results, we use Morningstar Style Box as investment style fixed effects instead of Morningstar Category classifications and this change does not affect our main results.

Del Guercio and Tkac (2008) use an event-study methodology on Morningstar rating changes to study the impact of Morningstar on mutual fund flows. They argue that this approach circumvents the problem of correlation between performance variables, which makes it difficult to obtain an accurate estimate of the marginal effect of any given measure on fund flows. However, one problem that arises from doing event studies with ratings already identified by Faff et al. (2007) is that ratings are highly transitory in nature, making it difficult to apply the full Del Guercio and Tkac (2008) methodology. For example, in our sample, in 2019, 36 funds changed their rating, of which 23 changed their rating more than once over the year. This would make the inference from an event study very noisy.

This means that if, for example, a fund was upgraded to 5-star in the last month, Upgraded to 5-star takes the value of 1.

Ferreira et al. (2012) argue that investor sophistication is explained by the level of development of the financial industry and the mutual fund industry in a country, and that there is less sensitivity to poor performance and high sensitivity to top performance in countries with less sophisticated investors.

This is consistent with the findings in Huang et al. (2007) that show that the convexity of the flow-performance relationship has declined over time for U.S. funds due to investors becoming better informed.

The 1-star rated fund group is the reference group, as it provides a bottom limit from which it is possible to evaluate the performance of higher-rated funds. If the Morningstar ratings accurately forecast abnormal performance, then we would observe increasingly positive and significant coefficients moving from 1 to 4. For example, if 4 is significant, then the difference in performance between 5-star and 1-star funds is statistically significant.

In robustness tests we also control for past long-term performance by adding to our baseline model prior period 5-year raw returns.

References

Adkisson, J., Fraser, R.: Reading the stars: age bias in Morningstar ratings. Financ. Anal. J. 59, 24–27 (2003)

Bailey, W., Alok, K., David, N.: Behavioral biases of mutual fund investors. J. Financ. Econ. 102(1), 1–27 (2011)

Barber, B., Odean, T.: All that glitters: the effect of attention and news on the buying behavior of individual and institutional investors. Rev. Financ. Stud. 21, 785–818 (2008)

Ben-David, I., Li, J., Rossi, A., Song, Y.: What do mutual fund investors really care about? Am. Econ. Rev. (forthcoming) (2020)

Berk, J., Van Binsbergen, J.: Measuring managerial skill in the mutual fund industry. J. Financ. Econ. 118, 1–20 (2015)

Blake, C., Morey, M.: Morningstar ratings and mutual fund performance. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 35, 451–483 (2000)

Blume, M.: An anatomy of Morningstar ratings. J. Financ. Anal. 54, 19–27 (1998)

Brand Finance: BrandFinance® Banking 500 (2019)

Carhart, M.: On persistence in mutual fund performance. J. Finance 52, 57–82 (1997)

Dahlquist, M., Engström, S., Söderlind, P.: Performance and characteristics of Swedish mutual funds. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 35, 409–423 (2000)

Del Guercio, D., Tkac, P.: The determinants of the flow of funds of managed portfolios: mutual funds vs. pension funds. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 37, 523–557 (2002)

Del Guercio, D., Tkac, P.: Star power: the effect of Morningstar rating on mutual fund flow. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 43, 907–936 (2008)

Del Guercio, D., Reuter, J.: Mutual fund performance and the incentive to generate alpha. J. Finance 69, 1673–1704 (2014)

Demirci, I., Ferreira, M., Matos, P., Sialm, C.: How Global is Your Mutual Fund? International diversification from multinationals. Working paper (2019).

European Fund and Asset Management Association, International Statistics Release (2020)

Evans, R. B., Sun, Y.: Models or stars: The role of asset pricing models and heuristics in investor risk adjustment. Rev. Financ. Stud. Forthcoming (2020)

Faff, R., Parwada, J., Poh, H.-L.: The information content of Australian managed fund ratings. J. Bus. Financ. Acc. 34, 1528–1547 (2007)

Ferreira, M., Keswani, A., Miguel, A., Ramos, S.: The flow-performance relationship around the world. J. Bank. Finance 36, 1759–1780 (2012)

Ferreira, M., Keswani, A., Miguel, A., Ramos, S.: The determinants of mutual fund performance: a cross-country study. Rev. Finance 17, 483–525 (2013)

Ferreira, M., Keswani, A., Miguel, A., Ramos, S.: What determines fund performance persistence? International evidence. Financ. Rev. 16, 1–30 (2019)

Gallaher, S., Kaniel, R., Starks, L.: Advertising and Mutual Funds: From Families to Individual Funds. Working paper, University of Texas at Austin (2008)

Gallaher, Steven T., Ron Kaniel., Starks, L.T.: Advertising and mutual funds: From families to individual funds. CEPR papers 10329 (2015)

Goetzmann, W., Peles, N.: Cognitive dissonance and mutual fund investors. J. Financ. Res. 20, 145–158 (1997)

Gruber, M.J.: Another puzzle: the growth in actively managed mutual funds. J. Finance 2011, 783–810 (1996)

Hortacsu, A., Syverson, C.: Product differentiation, search costs, and competition in the mutual fund industry: a case study of S&P 500 index funds. Quart. J. Econ. 119, 403–456 (2004)

Huang, J., Wei, K., Yan, H.: Participation costs and the sensitivity of fund flows to past performance. J. Finance 62, 1273–1311 (2007)

Huang, C., Li, F., Weng, X.: Star ratings and the incentives of mutual funds. J. Finance 75, 1715–1765 (2020)

Huberman, G.: Familiarity breeds investment. Rev. Financ. Stud. 14, 659–680 (2001)

Investment Company Institute, Mutual Fund Factbook (2020)

Ippolito, R.: Consumer reaction to measures of poor quality: evidence from the mutual fund industry. J. Law Econ. 35, 45–70 (1992)

Jain, P., Wu, J.: Truth in mutual fund advertising: evidence on future performance and fund flows. J. Finance 55, 937–958 (2000)

Jun, X., Li, M., Yan, W., Zhang, R.: Flow-performance relationship and star effect: new evidence from Chinese mutual funds. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 50, 81–101 (2014)

Kaniel, R., Starks, L., Vasudevan, V.: Headlines and Bottom Lines: Attention and Learning Effects from Media Coverage of Mutual Funds. Working paper (2007)

Keller, K.: Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. J. Mark. 57, 1–22 (1993)

Keswani, A., Stolin, D.: Which money is smart? Mutual fund buys and sells of individual and institutional investors. J. Finance 63, 85–118 (2008)

Keswani, A., Mamdouh, M., Miguel, A., Ramos, S.: Uncertainty avoidance and mutual funds. J. Corp. Finan. 65, 1017–1048 (2020)

Khorana, A., Servaes, H., Tufano, P.: Explaining the size of the mutual fund industry around the world. J. Financ. Econ. 78, 145–185 (2005)

Kronlund, M., Pool, V., Sialm, C., Stefanescu, I.: Out of sight no more? The effect of fee disclosures on 401(k) investment allocations. J. Financ. Econ. Forthcoming (2020)

Merton, R.: A simple model of capital market equilibrium with incomplete information. J. Finance 42, 483–510 (1987)

Morey, M.: Mutual fund age and Morningstar ratings. Financ. Anal. J. 58, 56–63 (2002)

Morey, M.: Kiss of death: a 5-star Morningstar mutual fund rating? J. Invest. Manag. 3, 41–52 (2005)

Odean, T.: Do investors trade too much? Am. Econ. Rev. 89, 1279–1298 (1999)

Plantier, L.: Globalization and the global growth of long-term mutual funds. ICI Global Research Perspective 1, No.1 (2014)

Petersen, M.: Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: comparing approaches. Rev. Financ. Stud. 22, 435–480 (2009)

Pool, V., Stoffman, N., Yonker, S.: No place like home: familiarity in mutual fund manager portfolio choice. Rev. Financ. Stud. 25, 2563–2599 (2012)

Reuter, J., Zitzewitz, E.: How Much Does Size Erode Mutual Fund Performance? A Regression Discontinuity Approach. NBER working paper 16329 (2015).

Sirri, E., Tufano, P.: Costly search and mutual fund flows. J. Finance 53, 1589–1622 (1998)

Thompson, S.: Simple formulas for standard errors that cluster by both firm and time. J. Financ. Econ. 99, 1–10 (2011)

Acknowledgements

We thank Morningstar Norway, particularly Ketil Myhrvld and Afsheen Azam. They made this paper possible through providing essential data. We also thank two anonymous referees for comments suggestions and the Professor Markus Schmid Editor. This research is supported by a Grant from the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (Grant UIDB/00315/2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix 1

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aasheim, L.K., Miguel, A.F. & Ramos, S.B. Star rating, fund flows and performance predictability: evidence from Norway. Financ Mark Portf Manag 36, 29–56 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11408-021-00390-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11408-021-00390-8