Abstract

This paper develops a theory of the organization of high-end restaurants. I identify the high degree of output complexity produced by these establishments as the industry’s fundamental characteristic. This high degree of output complexity leads to reputational investments by restaurants, which in turn affects their organizational structure. In particular, my theory addresses the prevalence of chef-owned establishments in the fine dining industry and the assignment of productive tasks within its kitchens.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Appetizer

For most of human history, meal preparation was a mundane enterprise. Its goal was to make food tastier and more digestible. With the rise of Haute Cuisine in nineteenth century France, the craft of cooking turned into culinary science. It’s only with the advent of Nouvelle Cuisine in the 1960’s and 1970’s that meal-preparation became a creative endeavor and the chef turned into an artist. Today, patrons of fine-dining establishments expect their culinary experience to consist of a unique combination of sensory stimulations–from the flavor profile of the meal to the combination of the colors and geometric composition of the plate to the overall atmosphere of the restaurant. Chefs are well aware of this and often refer to their job as that of “selling an event” or “fulfilling [the customers’] dreams”, rather than the mere selling of good-tasting food:

My greatest wish is to surprise the people who come to me, to enchant them with my dishes. When they eat, and I see how much they like it, I am happy, I have reached my goal. For this I am willing to do everything.Footnote 1

As is typical with experience goods, trade over dining services is supported by significant reputational investment on the supply side. Since the importance of reputation in an industry grows with the degree of complexity of the commodity supplied (Shapiro 1982), by increasing the complexity of the services sold by fine-dining establishments, the Nouvelle Cuisine movement was bound to affect the way the industry is organized.

This article develops an ‘optimal organization’ framework to study the internal structure of restaurants in the fine-dining industry. This framework identifies the fundamental determinant of a business’ organizational choice as the tradeoff between benefits from internal specialization in ownership and across tasks on the one hand and the potential losses due to an agent’s opportunism on the other. The allocation of residual claimancy and the extent of specialization are popular topics in the study of economic organizations. My argument relies on theories of organizational choice as developed by Grossman and Hart (1986), Hart and Moore (1990), Holmstrom and Milgrom (1991), and Wernerfelt (2002). Becker and Murphy (1992) and Allen and Lueck (1998) develop models of specialization where individuals and firms must decide which tasks to perform internally and which to outsource to the market.Footnote 2 My framework differs from these contributions in two important ways. First, theories of organizational choice study the ownership of the firm’s physical assets as determinant of equilibrium incentives, while my focus is on the ownership of the firm’s brand and reputation. Second, most work on the division of labor aim to explain its prevalence between firms while my analysis centers on the allocation of tasks within the firm.Footnote 3 The framework produces testable predictions about the internal organization of high-end restaurants and explains several of its characteristics. These include the prevalence of chef-owned establishments in the world of fine-dining, why chefs directly oversee the purchase of ingredients and why other tasks (like the management of the kitchen during service) are outsourced to the chef’s agents.

To test these implications, I rely on a mix of qualitative and quantitative evidence, including accounts of the history and current status of the fine-dining industry, public information on the ownership of Michelin-starred restaurants in the United States, and a small dataset on the allocation of tasks within high-end establishments in Europe. While, due to data limitations, it falls short of providing definite proof of causality, the evidence I present is strongly supportive of my framework. The share of chef-owned restaurants increases with the quality of the establishments, proxied by the number of Michelin stars received in 2019. Similarly, the pattern of task-allocation in the available sample follows a systematic pattern consistent with the theory: Tasks that are more likely, ex-ante, to yield opportunistic behavior on the part of an agent tend to be performed by the chef-owner.

Scholarly work on the fine-dining industry is scant. Ferguson (1998) provides a sociological theory of the development of gastronomy in post-revolutionary France. Rao et al. (2003, 2005) study the emergence of Nouvelle Cuisine in the second half of the twentieth century through similar sociological lenses. They argue that the new movement was able to solicit defectors from the ‘old school’ and establish itself as the new standard in the industry by leveraging discrepancies and contradictions in the received identity of traditional French chefs. Balazs (2001, 2002) study the entrepreneurial characteristics of celebrity chefs in France. Ottenbacher and Harrington (2007) investigate the innovation process employed by Michelin-starred chefs to develop and update their menus. Johnson et al. (2005) provide a typology of Michelin-starred restaurants based on thirty-six restaurants from four European countries. Finally, work in economics has focused on the effect of the award of a Michelin star on an establishment’s pricing strategies (Snyder and Cotter 1998; Gergaud et al. 2007, 2015).Footnote 4 My article contributes to this literature by extending insights from organizational economics to study the world of high-end restaurants.Footnote 5 To my knowledge, there has been no attempt in the literature to explain the ownership structure of these establishments and the pattern of division of labor and task-allocation within them. However, kindred work has focused on the internal organization of North American farms (Allen and Lueck 1998), carpentry shops (Simester and Wernerfelt 2005), and the trucking industry (Baker and Hubbard 2003).

2 First course

The lingua franca of the fine-dining industry is French. Roasts are served au-jus, vegetables cut a la julienne. Desserts have names like crème brûlée and mille feuille. This entire world is dominated by norms and practices first adopted by French restaurateurs over the past 300 years. The very notion of a restaurant, as we understand it today, is French. Throughout history, there had always been places like markets and taverns where willing customers could sit at a table and purchase and consume a meal. However, the modern restaurant-with food prepared by a team of professional cooks, selected by patrons out of a menu of dishes, served to patrons by a waiter or waitress-first emerged in France at the turn of the 19th-century.Footnote 6 It is during this period that French gastronomy emerged and consolidated its fundamental characteristics, from the selection and manipulation of ingredients through cooking techniques to the organization of the kitchen.Footnote 7 Over the following decades, France-trained chefs (who, in most cases, were still also French chefs) came to dominate the kitchens of fine-dining establishments throughout the world.Footnote 8

These followed the traditional precepts of French cuisine they had learned at culinary school or during an apprenticeship. The gastronomical knowledge inherited from the previous generations of French chefs specified which ingredients to use and in what combination as well as the cooking techniques to be employed in the preparation of dishes and menus. The Nouvelle Cuisine movement in the 1960s and 1970s freed fine-dining chefs from the strictness of this tradition. Nouvelle Cuisine emphasized the freshness of ingredients, encouraged the import of elements, flavors, and techniques from other culinary traditions, and rewarded creativity in the design of new dishes and menus.Footnote 9 The figure of the chef became even more central to the operation of the restaurant. Up to this point, the chef had been master artisans in charge of the operation of a kitchen-usually employed by a hotel, an inn, or a similar business-and custodian of received culinary wisdom. Nouvelle Cuisine added a creative and experimental dimension to the chef’s prerogatives. Now, she had to also be an artist with a unique creative vision that would be expressed in the menu offered in her restaurant.Footnote 10 The contemporary celebrity chef, a mix of irascible culinary genius and rock-star, was born.

The influence of this history on contemporary high-cuisine manifests itself in two important ways. The first tangible effect of this heritage is the importance of formal culinary training in a chef's career. Someone who aspires to enter this world may enroll in culinary schools.Footnote 11 Others begin their career as dish-washers, waiters, or line cooks (the bottom of the kitchen's hierarchy) to serve as apprentices of an established chef.Footnote 12 At culinary school, one learns the fundamental skills of traditional French cooking. These include knife skills, mise en place, the preparation of stocks, roux, and sauces, and so forth.Footnote 13 Here, students practice these skills for hours and hours, 6 days a week, until the movements, timing, and mindset of a chef have become second nature to them. One key focus of formal culinary education is attention to details:

You can’t ever send out a product if it's not right. It doesn't matter how busy you are. Your reputation is on the line every time you put a plate out. If you get into the mindset that ‘I don't care what it looks like, I'm too busy, just take it out, maybe they won't know the difference,' then that's the kind of restaurant you'll work in the rest of your life. You'll never work in a really great restaurant and you'll never be a really great chef. You'll work in a mediocre restaurant and you'll be a mediocre chef. Because that's the mindset of a mediocre chef: ‘I'm too busy to do it right; get it out of my face!’Footnote 14

The production of a certain dish requires that all instructions-regarding the size, quantity, and order in which ingredients are combined, as well as the amount of heat to which they are exposed, the tools being used, the force and pressure applied to them and so forth-are followed to the letter. Any deviation will result in an unsatisfactory product at best and a health hazard at worst.Footnote 15

The French legacy is further in the organization of the kitchens of these restaurants, which tend to be structured along the traditional French model. This model is highly hierarchical. In the kitchen

[t]he rules are rigidly adhered to, with the aim to ensure the consistently high standard of everything that is put in front of the client. Thoroughness, completeness, and conformity to standard and established procedures are the main values that are stressed in these organizations. This systematization and formalization are not an easy task in an organization where every dish is made individually and by hand.Footnote 16

George Orwell, who worked as a dishwasher in a French restaurant in his youth, compares the internal structure of the kitchen to that of an army: “Our staff … had their prestige graded as accurately as that of soldiers, and a cook or waiter was as much above a plongeur as captains about a private.”Footnote 17 The chef is the absolute ruler, sitting at the top of the hierarchy. Below her is the restaurant’s personnel, divided into two teams. The first team is responsible for the preparation of the food. It consists generally of a sous-chef, the second in command and responsible for the kitchen during the hours of operation, and as many chefs de partie as there are separate stations in the kitchen (appetizers, vegetables, meat, seafood, desserts, etc.). In the larger restaurants, one can find demi-chefs de partie, who assist the chefs in each station, as well as commis and apprentices that are responsible for the more basic tasks in the preparation of the dishes. The second team is responsible for serving the customers. Overseeing the dining room is the restaurant director. Below her are the three maîtres d’hotel (first, second, and third), responsible for order-taking and meat-carving. The chef de rang serves the tables and cleans up after the customers are done, assisted by her demi-chef. The sommeliers (who assist the customers in selecting and serving the wine) form their own hierarchy-within-the-hierarchy.

3 Second course

When the goods and services a firm supplies must satisfy a subjective demand for quality and their attributes are hard to measure objectively, the legal system is limited in its ability to enforce exchange. This has two implications for the internal organization of high-end restaurants. First, the restaurant and its customers must rely on mostly extra-legal mechanisms to enforce trade, such as reputation and branding. Though costly to create and sustain, brands have the beneficial effects of (a) reducing the cost of acquiring information on the past performance of suppliers in the absence of repeated interaction and (b) creating a stream or rents that would be foregone if the restaurant were to lower its standards of quality below some threshold.Footnote 18

The second implication is that information asymmetries are bound to emerge between the brand-owner and the chef. If the attributes of the restaurant’s output are hard to measure, so are those of the chef’s input into its production process. This is especially true of the creative process behind the design of new dishes and menus. Fine-dining chefs employ highly-specialized knowledge (of cooking techniques, of ingredient selection, of flavors combination, and so forth), the faithful application of which is necessary for the creation of a high-quality product. The more specialized the chef’s knowledge and skills, the harder it is for the (non-chef) owner to evaluate accurately her performance. Monitoring a high-end chef is particularly challenging due to the creative and artistic dimensions of the latter’s job. These are expressed in the design of individual dishes and the menu. At a high-end restaurant, each dish plays a specific role in the overall menu and must complement all of the other offerings of the establishment. Many such restaurants offer a limited selection of options to patrons. In some extreme cases, the customers have no choice at all. The chef may even demand that they consume each element of each dish in a specific sequence (Ottenbacher and Harrington 2007: 453).

The chef expresses her creativity by manipulating one the three fundamental variables behind each dish: taste profile, texture, and color (Ottenbacher and Harrington 2007: 448). Culinary tradition has identified a set of standards and norms on what combinations of these variables are more likely to produce a desired outcome. However, these serve merely as a starting point to the chef’s creative process. To attain prominence within this landscape, chefs must devise new and exciting combinations. Out of the countless conceivable combinations, only a few are going to please the patrons’ palates. Being able to identify a winning combination of flavor, texture, and color that is also surprising and innovative requires natural talent, technical skills, and luck. Unsurprisingly, fine-dining chefs “spend a lot of time and effort in creating new dishes” (Ottenbacher and Harrington 2007: 447). This creative process is made possible by a form of “tacit knowledge” or “chefmanship” (Ottenbacher and Harrington 2007: 449), which requires constant research and experimentation with new ingredients and techniques. A chef’s research may take the form of visiting other chefs’ restaurants or reading industry literature (cookbooks, magazines, etc.). Once the chef identifies a new technique or combination of ingredients that she thinks can be incorporated into her cooking in innovative ways, she will start experimenting with them. During this process, the chef will first learn to master the new technique and ingredients and then develop different recipes until she identifies a viable candidate (Ottenbacher and Harrington 2007: 451). Only then, will she train her crew and include officially the new dish in the menu.

By the very nature of this process, owner and chef won’t be able to specify many of the relevant attributes of the final product, making the exact contribution of the chef’s creativity and talent to the overall performance of the restaurant hard to measure.Footnote 19 Hence, as with all creative enterprises, delegation can be counterproductive since a rational chef is likely to act opportunistically and shirk on her duties. Specifically, she may supply too little effort in undertaking her creative responsibilities. Lacking the specialized knowledge to establish the quality of the chef’s work, the owner is left guessing the value the latter contributes to the establishment’s fortunes and misfortunes.

Chef-opportunism can be extremely damaging to the establishment’s profitability since its success “depends entirely on the skills and culinary excellence of the restaurant’s celebrity chef” (Johnson et al. 2005: 171). To mitigate her incentive to shirk, the chef of a high-end restaurant is likely to assume residual claimancy over the operation of the business. Extending the ownership of the business to the chef minimizes on the agency costs that emerge under conditions of asymmetric information in the production of fine-dining services. A chef who is also a residual claimant has all the incentives to self-police since she bears the losses associated with her shirking and other forms of opportunism.Footnote 20

The importance of reputation and the potential for chef opportunism are not unique to high-end restaurants and are bound to characterize the whole dining industry: Every meal, no matter who serves it, is an experience good. Similarly, information asymmetries between owner and chef will exist regardless of the type or quality of food being prepared, as long as the two roles are performed by different individuals. However, the degree of complexity that is required for a service to be considered fine-dining makes it particularly vulnerable to both forms of opportunism. To see why, consider the difference between a diner and a high-end restaurant. Diners serve a long list of staple items, most of them made with just a few ingredients, and relatively easy to prepare. They also seldom change their menu. This is the opposite business model of high-end restaurants. While a diner’s reputation matters, it won’t play as significant a role as that of a fine-dining establishment. After all, there is only so much you can do to make eggs and bacon taste bad.Footnote 21 A similar logic applies to the case of chef opportunism. Information asymmetries between principal and agent grow more pernicious the more highly specialized the skills performed by the agent. However, the asymmetry of information is inconsequential if chef opportunism has little effect on the final product or it is easily spotted. Let’s again compare a diner and a fine-dining restaurant. In general, the skills of the chef in charge of the latter are more specific than those of a chef in charge of a diner. The creative input of the former is also more consequential to the overall performance of their restaurant. Thus, while the dining industry as a whole is prone to these forms of opportunism, they affect more significantly high-end establishments than others.

As there is no such thing as a free lunch—and this has never been truer than in the world of Haute Cuisine—the transfer of residual claimancy to solve agency problems comes at a cost. This has two potential sources: the foregone benefits from specialization in ownership and the potential for multi-tasking when the transfer does not include residual claimancy over all assets and attributes.Footnote 22 In the case of high-end restaurants, the costs of chef-ownership are likely more than compensated by its benefits. Since the size of their operation is limited by significant diseconomies of scale, high-end restaurants are unlikely to experience large losses from the foregone benefits of specialization in ownership.Footnote 23 Multi-tasking concerns do not seem to apply, either: Due to the fundamental role of reputation in this industry, the most precious asset of a high-end restaurant is its reputation, usually identified with a brand-name (such as the name of the restaurant or the name of the highest-ranking chef). This leads to the prediction that the chef will also be the owner (or have partial ownership) of the business.

While high-end restaurants are relatively small operations, they are nevertheless fairly complex ones. Running a successful business in this industry requires the effective and coordinated performance of multiple tasks. As the partial or full owner, the chef will want to allocate these tasks in a way that balances the benefits of specialized labor with the costs of monitoring the behavior of the employees and measuring their output.Footnote 24 This leads to a prediction regarding the allocation of tasks between the chef-principal and her employee-agents. Those tasks that produce a homogeneous output or that consist of a process that can be automated will tend to be allocated to the agents. The principal will keep to herself those tasks the contribution of which is hard to measure. Another category that will gravitate towards the principal is that of tasks where shirking and opportunism are both feasible but hard to infer from observing the final product (Barzel 1987). As applied to the organization of high-end restaurants, this suggests that the chef, the creative mind of the restaurant, will also be responsible for the selection of ingredients, which is hard to monitor without costly double measurement (Barzel 1982). Similarly, it suggests that she will entrust such tasks as the attending of tables (immediate feedback and partial residual claimancy by the waiting personnel) and meal preparation during service (automated and easy to measure) to her employees.

4 Third course

4.1 Ownership

The optimal-organization approach to high-end restaurants predicts the adoption of an ownership structure that minimizes the potential for chef opportunism. The chef’s main responsibility lies in devising new dishes and menus offered by her kitchen, a crucial task to the success of the operation. The chef will assume residual claimancy by assuming ownership of the restaurant. The value of the restaurant’s brand is a function of customers’ expectations about the quality of service. If the chef deviates from high-quality performance, she will be forced to bear the losses in the capitalized value of the brand, where the brand may encompass the establishment, the chef herself, or both.

Other contractual forms can make the chef a residual claimant over the receipts of the restaurant but do not necessarily extend her claimancy over the value of the brand. For example, the owner of the establishment may employ a form of compensation that rewards the chef based on the performance of the restaurant. The chef may receive bonuses at the end of the year if certain targets have been met or she may receive a constant share of the revenues. In neither case does the chef have any claim over the value of the brand of the restaurant. This may introduce intertemporal agency problems, the chef having an incentive to maximize current profits but possibly jeopardizing the long-run profitability of the enterprise.Footnote 25 Extending ownership of the establishment to the chef, rather than adopting some other contractual form, mitigates this problem.

The existence of the chef’s own professional reputation may have similar effects on her performance if the potential customer-base knows which chef is in charge of which restaurant. This is made more likely by the existence of such institutions as the Michelin Guide and the rise of fine-dining-centered media networks. In many developed countries, over the past two decades,Footnote 26 chefs have emerged from their kitchens to take center-stage in popular culture. Some of these ‘celebrity-chefs’ have their own TV show and line of frozen food. They publish bestselling cookbooks. Some have become cultural icons.Footnote 27 The predicted effect of the chef-brand on her performance is ambiguous. On the one hand, personal-brand investment would have similar effects on the chef’s incentive to perform as those of the restaurant’s brand. This generates a stream of future rents as long as she does not act opportunistically in the present. If she is only partial claimant of the restaurant but owns fully her brand, the latter increases her losses from hwe own opportunistic behavior, leading to less opportunism overall. On the other hand, the chef's brand may distract her from restaurant duties. She may spend more of time traveling, guesting a TV show or hosting her own, writing books, giving interviews to the press, and so forth and less time at the restaurant. Or she may be tired and distracted while working in the kitchen. Over time this will have negative effects on the quality of restaurant’s output.

These negative effects on quality may be more than compensated for by an increase in revenues due to the chef’s popularity. Having a celebrity-chef managing the restaurant could generate a lot of publicity and zero-priced advertisement for the establishment temporarily pushing demand ‘away from the origin’ even as the quality of the goods served and the dining experience goes down. One way to realign the celebrity chef's incentives with those of the establishment would be to increase her share of the residual from the restaurant's proceeds and thus bear more fully any losses associated with her lack of effort. Alternatively, her contract with the restaurant may impose restrictions on her alternative sources of income, especially the rents generated by her personal brand.

4.2 Tasks

The operation of a high-end restaurant requires the coordinated performance of several tasks. The optimal organization approach predicts that the assignment of these tasks will be influenced by the ability of the chef to measure the performance of her agents and their contribution to the services supplied to the patrons. Tasks that are prohibitively costly to monitor will be performed directly by the chef while those easy to monitor or that can be automatized will be assigned to agents to take advantage of gains from specialization.

The literature on Haute Cuisine identifies four fundamental tasks that must be performed in the operation of a high-end restaurantFootnote 28:

-

1.

Financial administration

-

2.

Personnel administration

-

3.

Food preparation

-

4.

Ingredient selection

These tasks differ over a variety of margins. For the purpose of my discussion, I focus on the ability of the chef-owner to identify an agent's opportunism in the performance of each.

4.2.1 Financial administration and food preparation

Financial management and food preparation fall at one extreme of the spectrum of least to most costly to observe. The chef-owner has several tools at her disposal to monitor her agents. For example, the chef-owner is promptly alerted by suspicious changes in the flows of revenues and costs in the operation of the restaurant. The chef-owner can also rely on the external services of professional accountants to ensure that no wrongdoing took place. Similarly, tax authorities may identify discrepancies that will direct the attention of the chef-owner to potential irregularities. Food preparation in high-end restaurants is a highly automatized process. Line cooks and the various chefs and sous-chefs are expected to perform with the technical precision and consistency of machines. During their years of training (whether in culinary school or as apprentices at other high-end restaurants), they develop the ability to perform according to the dictates of the chef-owner. Everything, from the style and size of the cutting of ingredients, the timing of each step of the cooking, the temperature at which the dish must be served, and so forth are identified in the instructions provided by the chef. The existence of a set of standards allows the chef-owner to easily establish whether any deviation from her instructions had taken place.Footnote 29 When a new menu or a new dish is introduced, the chef will generally perform their preparation in front of their crew at least once before having the latter attempt to replicate the process (Ottenbacher and Harrington 2007: 454). The chef expects its crew to produce the dish exactly as she envisions it: “We train as often or long until the kitchen employees can cook it 100 percent perfect. The dish must be perfectly cooked without [the chef] being involved in the cooking process.”Footnote 30

Chefs adopt three relatively cheap strategies to ensure the consistency of their dishes. First, a chef will visit her kitchen, seemingly at random, several times during service.Footnote 31 This ‘randomization' limits the ability of the kitchen personnel to shirk. Second, many of the dishes leaving the kitchen during service are first ‘expedited’, that is, they go through the chef-owner for a last-minute quality check before being served to the customers. Expediting allows the chef to identify fundamental flaws in the preparation of the dish just by looking at it. If any such flaws are found, the chef will send the dish back to the kitchen where the relevant chef de partie will have to remake it from scratch, in some cases after enduring the chef’s ire: “if someone is sloppy or careless, I get very angry … if they repeat the same mistake over and over again they will not last long with me.”Footnote 32 Finally, chefs spend much of their time in the dining room, stopping at each table to introduce themselves to the patrons, engaging in small talk, and explaining to them the ‘philosophy’ behind their menus.Footnote 33 In the process, a chef will ask patrons what they thought of the dishes. If their response is not enthusiastic, she may ask them she can ‘take a bite’ and taste the dish herself, as a Michelin-starred chef explained during a private conversation. If the dish is indeed flawed, she will apologize and offer to compensate them for the inconvenience.Footnote 34

4.2.2 Personnel management

Outsourcing the management of a restaurant’s personnel can prove more challenging than the tasks above. On the one hand, chef-owners can rely on professional certifications, letters of recommendation, and other proxies for ability when making a hiring decision. On the other hand, technical ability is not the end-all and be-all of working in a professional kitchen, especially at a high-end restaurant. The ideal employee must have several characteristics other than technical skills. She must be a team player, capable and willing to take and execute orders from her superiors. She must show attention to detail and be able to learn quickly recipes and techniques as presented by the chef-owner.Footnote 35 Some of these can be measured by a third party acting as the chef’s agent. However, a candidate that appears originally as a ‘good-fit’ may demonstrate herself a liability over time. A third party may credibly deny responsibility and claim to have been deceived by the candidate.

There is little the chef-owner can do to establish the truth of the matter, thus creating room for significant opportunism. The cost of opportunism will be especially significant for positions with large influence on the performance of the restaurant (such as line-cooks or chefs and sous-chefs du partie). Knowing that the chef-owner won’t know whether the candidate was a ‘bad-apple’ from the beginning, the third party has an incentive to put less than optimal effort in the screening process. Given the circumstances, the chef-owner will take some initiative in the recruiting process.

4.2.3 Selection of ingredients

The selection of ingredients is of foremost importance for the success of a fine-dining establishment (Ottenbacher and Harrington 2007). Selecting ingredients means identifying a set of reliable suppliers as well as making sure that the ingredients met the very high standards of the industry. Entrusting this task to a third party presents very similar complications to those of personnel management. These complications will have severe negative effects on the performance of the restaurant. First, the agent may suffer more acutely from information asymmetries than the chef-owner when dealing with suppliers. The chef may instruct the agent about the desirable and undesirable characteristics of the ingredients, but this process is unlikely to result in perfect knowledge transfer. Another obstacle to the effective delegation of this task lies in the very nature of the goods being purchased. The room for opportunism would be much smaller if these commodities were standardized. However, high-end restaurants pride themselves to use organic and artisanal products, exactly the sort of commodities that experience greater variation in their characteristics.Footnote 36 This task is also prone to agency problems because it is hard to establish whether the ingredients met the chef-owner’s standards once they have been manipulated (peeled, minced, cooked, and mixed with other ingredients) before and during the preparation of the final meal. Finally, undesirable outcomes-a dish that tastes or looks different from what the chef envisioned-may be blamed on any of the many other links that followed the purchase of the ingredients. A tomato-based sauce may taste ‘off’ because the tomatoes were too ripe (or not ripe enough) at the moment of the purchase, or because they were stored improperly, or that they were not prepared exactly according to the chef’s directions. The potential for opportunism makes it more likely that the chef-owner will take over the process.

5 Fourth course

5.1 Ownership

Testing the implications of the optimal-organization approach is not easy. Its predictions are about real economic variables (the allocation of claims over the residual from economic activities) which are, in some cases, hard to observe. For example, nominal ownership over an asset is not equivalent to its real counterpart, especially when transaction costs are high and the assets complex.Footnote 37 High-end restaurants tend to be relatively small business-ventures and their organizational structure takes one of three forms: (a) the restaurant is owned by its highest-ranking chef or chefs; (b) the restaurant is owned by a hotel or an inn; (c) the hotel is owned by some private investor or group of investors.

Every year since 1900, the tire manufacturer Michelin has released a guide of the best restaurants in France. Over time, the Guide evolved into a global institution. Today, the company’s representatives travel around the world to evaluate thousands of restaurants across four continents. In 2016, there were over 2,700 Michelin-starred restaurants across twenty-eight countries. France had the most starred restaurants of any country, with six-hundred establishments, followed by Japan, Italy, Germany, Spain, the United Kingdom, and Belgium. Only two countries in the Americas, the United States and Brazil, had any Michelin-starred restaurants in 2016.

Not all starred restaurants are created equal. The Michelin Guide assigns one, two, or three stars based on five criteria: the quality of the ingredients used to prepare the meals; the “mastery of flavor and cooking techniques” employed by the chefs; the chef’s personality and demeanor; the ‘value’ of the restaurant’s offer; and the consistency of quality, mastery, personality, and value over time. One star indicates that the restaurant is of overall ‘high quality' and therefore ‘worth a stop'. Two stars indicate that the restaurant has attained a degree of ‘excellence' in culinary matters and is thus ‘worth a detour'. The third and final star means that the establishment has achieved an ‘exceptional' status and is deserving of ‘a special journey'. In 2019, there were only eighty-eight three-star restaurants in the world.Footnote 38

Table 1 shows data on the ownership structure for all US restaurants that received at least one Michelin star in 2019. To gather this information, I rely on a variety of sources, including the Michelin Guide, the establishments’ websites, culinary magazines, and local newspapers. Out of two hundred and six observations, I could not find any information about the ownership of two establishments. The remaining observations show a pattern consistent with the optimal-organization framework. One hundred fifty-eight of all US Michelin-starred restaurants are owned, at least in part, by their highest-ranking chef(s).Footnote 39 Over seventy-seven percent of all establishments extend partial residual claimancy to their chefs. The second most popular option for these restaurants is ownership by a private investor or group of investors. This was the case for thirty-one establishments, or fifteen percent. Over half of these are in New York City, where investors-owned establishments represent twenty percent of the total. Hotels or similar ventures own nine Michelin-starred restaurants in the United States, just shy of five percent.

By themselves, these figures cannot adjudicate on the predictiveness of my framework. One would have to compare the ownership structure of these establishments with that of other categories of restaurants and enterprises in the dining business. However, the data show two patterns that are highly suggestive of the framework’s validity. First, while franchises, chains, and other agglomerates dominate other popular categories of the dining sector, they are only a small share of Michelin-starred establishments. According to the 2012 Economic Census, fifty-four percent of all fast-food restaurants belong to a franchise.Footnote 40 Of the two hundred ad four observations for which I have ownership data, none can be truly characterized as belonging to either a franchise or a chain. The closest case is that of the Sushi Ginza Onodera restaurants in Los Angeles and New York. Both restaurants share name and owner (Hiroshi Onodera) but are operated by two separate head chefs. Another case is that of three restaurants, two in New York and one in Los Angeles, all owned by the same hospitality group, under the leadership of three distinct chefs. There are four other cases of establishments sharing the same owner. In all four cases, the restaurants are chef-owned and operated. In three of these, the chef owns two restaurants in the same city (two cases in New York and one case in the Bay Area). In the remaining case, the same chef owns three establishments, two in the Bay Area and one in New York. Combined, these cases account for fewer less than seven percent of all Michelin-starred restaurants. The discrepancy in the share of chain-owned or franchised establishments between fast-food restaurants and high-end ones is consistent with the optimal organization approach. Overall, fast-food restaurants specialize in the supply of highly standardized commodities (so much so that one knows exactly what the fries will taste like in advance). Their employees have little-to-no culinary skills and creativity plays but a marginal role. Thus, they don’t face the constraints that fine-dining establishments do, which is reflected in their ownership structure.

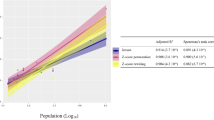

The second pattern consistent with the optimal organization framework is the distribution of ownership-type among categories of Michelin-starred restaurants. The framework predicts that the prevalence of chef-owned restaurants will increase with quality of service. If one uses the number of Michelin stars as a proxy for the quality of service, the data in Table 1 show that the percentage of restaurants that are chef-owned increases with the number of stars. Seventy-five percent of one-star establishments are chef-owned. The same figure is seventy-nine percent among two-star restaurants. Finally, in my sample, all three-star establishments (that is, restaurants reaching the highest level of quality) are chef-owned.

In “Appendix 1”, I provide the regression tables for several empirical tests of the hypothesis that quality, measured by the number of Michelin stars, predicts the degree of chef-ownership among the establishments in my sample. Table 3 reports the results of an ordinary least squares regression using robust standard errors. The results of this model indicate that a two-star establishment is not significantly more likely to be chef-owned than a one-star establishment but that a three-star establishment is. Column 1 suggests that the probability that a three-star establishment is owned by the chef is 24.7 percentage points higher than that of a one-star restaurant, and the coefficient is significant at the one percent level. Column 2 reports the results with regional fixed effects and standard errors clustered at the regional level. These results reinforce those from columns 1: The probability that a three-star establishment is owned by the chef is 25.7 percentage points higher than that of a one-star restaurant. The coefficient is again significant at the one percent level.Footnote 41

The absence of variation in the dependent variable due to the fact that all fourteen three-star restaurants are chef-owned is a potential source of bias in the estimation of the coefficients in columns 1 and 2. To mitigate this bias, I create a new indicator variable, Two- or three-stars, equal to 1 when a restaurant has been assigned at least two stars. I then replicate columns 1 and 2 using the new variable instead of Two Stars and Three Stars. Column 3 reports the results of the baseline specification using robust standard errors. The coefficient has the right sign but is predictably smaller than the one reported in column 1 and only approaches marginal significance at the ten percent level. Column 4 contains coefficients for a specification that includes regional fixed effects and regionally clustered standard errors. As in column 3, the coefficient on Two- or three-stars is of the right sign but just shy of marginally significance.

Because my dependent variable (chef ownership) is binary, Table 4 reports the results of a series of logistic specifications. The results are consistent with those of Table 3, with a third Michelin star having a large and strongly significant effect on the probability that an establishment will be chef-owned (columns 1 and 2). As above, replicating the specification using Two- or three-stars as the independent variable instead (columns 3 and 4) produces positive coefficients that just fail to meet standard levels of significance. One shortcoming of the logistic strategy is that, in the presence of extreme events, it may generate coefficients that are unlikely large due to small sample bias (King and Zeng 2001). Since all three-starred restaurants are chef-owned in my sample, this is the case for the results in columns 1 and 2 in Table 4. To mitigate this problem, I apply the penalized maximum likelihood (or ‘Firth’) method to my logistic specification.Footnote 42 Consistent with the results of my other specifications, this method yields a positive and insignificant coefficient for Two-stars and a positive and significant (p = 0.02219) coefficient for Three-stars. The Firth method coefficients indicate that an establishment with only one Michelin star has a probability of 0.79 to be chef-owned. This figure increases to 0.82 if the restaurant has two stars. Finally, a three-stars establishment will be chef-owned with probability 0.97.

These results show a consistent pattern: More quality goes together with higher levels of chef ownership. This is consistent with the predictions of the optimal-organization approach. However, they fall short of proving systematically that this relationship is causal.Footnote 43 Moreover, due to data-limitations, my specifications may suffer from omitted variable bias. One significant source of the latter may be related to Gergaud (2017) finds that among French high-end restaurants, asset value varies drastically between establishments with zero, one, and at least two Michelin stars. If the size of the investment required affects the establishment’s ownership structure, then my coefficients will be biased. Requiring larger investments to achieve and maintain an extra star, chefs may have to rely on external investors as they operate at higher levels of quality. However, this appears inconsistent with the finding that chef ownership is less prevalent among one-star establishments than among three-star ones. Thus, eliminating this source of bias should strengthen my results.Footnote 44

One additional piece of evidence consistent with the predictions of my framework comes from the historical evolution of the fine-dining industry and the field of gastronomy in the second half of the twentieth century. The rise of Nouvelle Cuisine, an influential approach to gastronomy since the 1970s, coincided with significant changes in the organization of the industry. In classical Haute Cuisine, “[chefs] lacked the freedom to create and invent dishes,” instead, they were expected “to translate the intentions or prescriptions of [their 19th-century predecessors].”Footnote 45 Nouvelle Cuisine emphasized creativity and experimentation in the design of menus and dishes as well as the importance of fresh ingredients, often alien to traditional French cooking.Footnote 46 The increased importance of creativity coincided with a renovated role for the chef. Traditionally, she was “an employee of the restaurant owner and was in the background.”Footnote 47 The Nouvelle Cuisine model saw the chef attain increasing influence within and outside of the kitchen: “The role of the chef was reframed to that of an innovator, creator, and owner.”Footnote 48

5.2 Tasks

Johnson et al. (2005) provide the only available evidence on task allocation at Michelin-starred restaurants.Footnote 49 They have data on the performance of four tasks in a sample of twenty establishments from four European countries.Footnote 50 In a series of semi-structured interviews with these restaurants’ executive chefs, they asked who was in charge of the financial administration of the restaurant, the management of its personnel, the preparation of the meals during service, and the selection and oversight of the supply of ingredients. Johnson et al. (2005) distinguish between three categories of people who can potentially undertake these tasks: The chef, a member of her family, or a third party.

Table 2 summarizes their findings. Each row provides the percentage of establishments that saw the involvement of the chef (or family member, or third party) involved in each task. The data show that chefs dominate the overseeing of the provision of ingredients to the restaurant. In sixteen out of eighteen establishments, the chef was involved in this task. In four of these, she received aid from a family member. In only two establishments was this task within the purview of some other party. In this sample, chefs were the premier agents responsible for one more task: the management of the establishment’s personnel. This was the case in ten out of twenty restaurants. In two cases, she received assistance from another party (a family member in one case and a third party in the other). Chefs have limited involvement in the remaining two tasks. In either food preparation or the administration of the restaurant’s finances, only two chefs out of the whole sample were involved. In all these cases, they were assisted by either a family member or a third party. The chef’s family members seem to play a significant role in the administration of financial matters, with half of all observations showing their involvement with this task.

Third parties (employers of the restaurant with no familial connection to the chef) play a significant role in the financial administration of these establishments, as they are involved in this task in roughly half of them. They have a similar degree of involvement in the administration of personnel, with eight out of twenty establishments in the sample. Third parties dominate the preparation of food during service, with seventy percent of all establishments. Compare this number to that of family members. The latter are involved in this task in five out of nineteen observations. Third parties play only a minor role in the selection of ingredients and dealing with the suppliers. Family members appear more involved in this task with four cases out of eighteen. However, in all them, they are not the sole party responsible as the chef herself is also involved.

The concentration of responsibility over the procurement of ingredients onto the figure of the chef is supported by qualitative studies of the industry. Balazs (2002: 255) claims that “[t]oday’s great chefs have long-term contracts with their major suppliers with whom they deal directly, without intermediaries. They often choose their suppliers by first traveling around to find the best ones, and then building up long-term relationships with them.”Footnote 51 Chefs themselves justify this pattern on the basis that ingredients are “a crucial factor” to the success of their establishments:

Every ingredient has to always be the freshest available, most often representing the finest produce of the region where the restaurant is situated. According to Derek Brown, the managing editor of the Guide Rouge Michelin, what differentiates a three-star cook from a lesser one is, among others, the way he procures his products.Footnote 52

5.3 Dessert

In this article, I develop a theory of high-end restaurants. My approach relies on the conjecture that, in organizing their businesses, entrepreneurs face a tradeoff between the benefits of specialization and the losses from opportunism. If one knows the specific sources of opportunism a firm must overcome in its line of business, one should be able to predict the organizational responses the firm will adopt in the real world. I focus on two aspects of organizational choice: an establishment's ownership structure and the allocation of tasks within it. I predict that the industry's characteristics favor the assignment of residual claimancy to the chef and that the chef-owner will also maintain for herself such tasks as the design of the restaurant's menu and the selection of ingredients. Other tasks, including the preparation of the meal and the management of the establishment's finances, will fall in the hands of someone else.

In testing the framework’s empirical implications, I rely on a combination of qualitative evidence and very limited quantitative evidence. This is consistent with both of my predictions. Chef-ownership is widespread among American Michelin-starred restaurants, especially when compared to dining businesses, like fast-foods, that do not face the same obstacle in organizing ownership. A sample of European high-end restaurants also shows a pattern of task-allocation in line with my prediction. Admittedly, the evidence I provide cannot establish once and for all the validity of the causal mechanisms identified by my framework. Nor should readers interpret my discussion of theory and evidence as a general theory of organization in the fine-dining industry. Rather, my intent is to argue for the systematic role of incentives in affecting, alongside other factors, the organization of ‘creative’ businesses like high-end restaurants.

More systematic testing would require the collection of data on ownership and internal task-allocation from a representative sample of dining establishments across all levels of quality. The framework’s implications could also be tested against time-series data. For example, it predicts that the rise of Nouvelle Cuisine movement in the 1960’s and 1970’s would be followed by a change in the share of chef-owned high-end restaurants. This would require the collection of information on fine-dining establishments going back to the 1950’s. However, gathering this kind of data gets harder the further back one goes. Anecdotally, hotel restaurants seem to have been a larger share of fine-dining establishments before the Nouvelle Cuisine movement. To the extent that hotel restaurants and chef-ownership are mutually exclusive (something that is not entirely clear from historical accounts), this would be consistent with the framework. Harder still would be to collect systematic evidence on task allocation that far into the past. That being said, the framework may be extended to generate testable implications that that go beyond the narrow scope of this article.

Notes

Anonymous chef quoted in Balazs (2002: 250).

This is related to the standard argument on vertical integration and the ‘make or buy’ decision in the industrial organization literature.

One exception is Chossat and Gergaud (2003), which empirically identify two strategies chefs employ to achieve official recognition (as measured by being included in a prestigious guidebook of French cuisine): consistency in the mastery of French cuisine and investment in the ‘setting’ of the restaurant.

The work of scholars studying the use of franchise contracts in the fast-food industry comes closest. See Kaufman and Lafontaine (1994).

See Ferguson (1998).

See Trubek (2000).

Rao et al. (2003: 805).

In 2008, there were over 60,000 students enrolled in one of the 157 culinary schools across the United States (Ruhlman 2009).

In a sample of 20 Michelin-starred chefs, Johnson et al. (2005) find that 70% went through the apprenticeship route, 15% went through culinary school, and the rest was self-taught.

See Ruhlman (2009) for a detailed overview of a chef wannabe’s experience through culinary school.

Chef Michael Pardus of the Culinary Institute of America, quoted in Ruhlman (2009: 52).

Ruhlman (2009: 62–64).

Balazs (2002: 256).

Quoted in Turbeck (2000: 75).

The fine-dining industry presents many similarities with the painting industry in Renaissance Italy. Each artistic workshop was led by a master who was in charge, among other things, of the painting's overall design and the introduction of new techniques and styles but who left much of the actual painting to his apprentices (Cole 2018). On the economics of the Renaissance art market, see also Etro (2018).

This is the standard result of the literature on moral-hazard. In a principal-agent relationships with frictions in the contracting process, if the principal-owner cannot perfectly observe the agent-chef’s hidden effort, the latter consumes leisure in excess of the stipulated amount. The solution to the moral-hazard problem requires the transfer of residual claimancy from the principal to the agent. This transfer will be complete unless the agent is risk-averse. See Cheung (1968).

Casual observation seems to confirm this. For example, people are more likely to consult an expert’s review of a fine-dining establishment than a diner. Similarly, driving on the highway, you are much more likely to spot a diner than a fancy restaurant.

A great illustration of the multi-tasking problem with partial transfer of residual claimancy comes from agriculture (Allen and Lueck 1992). When a farmer rents a piece of land from its owner, she has full claim over the residual of the produce of the land over the duration of the contract. However, she bears none of the losses associated with the long-run consequences of her choice of agricultural practices. To the extent that she may increase output value (which is all hers) by adopting practices that generate losses in the value of the land in the long-run (and that are unobservable in the short-run), she will. As a result, farmers and land-owners are more likely to opt for sharecropping contracts when this form of multi-tasking is likely to be more prevalent (Allen and Lueck 1992).

On the benefits of specialization in the ownership and control of assets, see Fama and Jensen (1983).

For example, the chef may overwork her staff to increase short-term performance but leading to higher turnout rates over the long-run.

One possible explanation is the rise of the cooking-centered TV channel Food Network in the early 1990s. See Matus (2007).

The late Antoine Bourdain fits the rock star comparison fairly well.

See Johnson et al. (2005).

Ruhlman’s (2009) recollection of his time in culinary school contains episode after episode of chefs identifying mistakes in the making of a dish by look or taste.

Anonymous two-starred Chef, quoted in Ottenbacher and Harrington (2007: 454).

In an interview with the author, an Italian celebrity-chef and owner of a Michelin starred restaurant, explained how he comes in and out of the kitchen during service to check that everything is working smoothly and taste the food being prepared.

Anonymous chef quoted in Balazs (2001: 140).

Philosophy occupies a surprisingly significant role in the formation of Haute Cuisine chefs. In their introductory course on gastronomy, students of the Culinary Institute of America are taught to be ‘Socratic cooks’, to always start their creative process by questioning the ‘essence’ of the dish, and to ‘question everything’ (Ruhlman 2009: 14).

However, sometimes the complaint is simply the result of differences in tastes between the chef and the patron. In this case, the chef may explain her thought-process in designing the dish to the patron in an attempt to change the latter’s mind. So much for not arguing over taste!

Unsurprisingly, these character traits are the focus of the learning process during culinary school (Ruhlman 2009).

Standardization reduces across individual units of output as the production process comes increasingly under direct control by human agents and the whimsical role of nature is limited (Allen and Lueck 2004: 5).

See the discussion in Allen (2006).

Unsurprisingly, approximately one-third of them are found in France the remaining being distributed across nineteen countries.

I identify a restaurant as chef-owned as long as the chef is explicitly identified as owner, co-owner, founder, or proprietor of the establishment.

U.S. Census Bureau (2014).

While I do not report its results in the body of the text, I also estimated a model using a dummy variable for observations with one star instead of the two star one. In this mode, the coefficient on the three-star dummy identifies the increase in the probability that an establishment will be chef-owned if it were to have three stars instead of two. The measured effect is positive, large (twenty percentage points), and significant at the ten percent level in the baseline estimate and becomes significant at the one percent level using either robust fixed effects or fixed effects clustered at the regional level.

That is, the binary variable for chef ownership as a function of the number of Michelin stars, controlling for regional fixed effects.

For example, I cannot rule out that causality runs in the opposite direction. Chef-ownership may, for example, affect the chef’s creative control over her establishment, which in turn may influence the overall quality of service and probability of receiving an additional star.

Another reason omitting asset values is unlikely to be responsible for my findings is that my dependent variable, chef ownership, is binary. Thus, it captures any instance of residual claimancy being extended to the chef. The size of the investment required to operate at higher levels of quality may dilute the chef’s ownership share but is unlikely to result in a corner solution (e.g., no chef ownership) as long as the hidden effort problem exists.

Rao et al. (2003: 805).

See Rao et al. (2003: 806), especially the information in table 2.

Rao et al. (2005: 975, 980).

Rao et al. (2003: 807).

The reader should take this evidence with a grain of salt due to the small number of observations and the potential for deceit and exaggeration on the part of the objects of the study.

Each of these establishments had obtained at least two Michelin stars in the decade 1992–2001.

An Italian Michelin-starred chef confirmed this in an interview with the author. He has personally identified all the suppliers of ingredients for his restaurants, within whom he entertains long-term relationships. These are not regulated by similarly long-lasting formal contracts but rather by the chef’s threat of putting the supplier “on a diet” (i.e., to stop his orders temporarily).

Balazs (2002: 255).

References

Allen DW (2006) Theoretical difficulties with transaction cost measurement. Div Lab Trans Costs 2(01):1–14

Allen D, Lueck D (1992) Contract choice in modern agriculture: cash rent versus cropshare. J Law Econ 35(2):397–426

Allen DW, Lueck D (1998) The nature of the farm. J Law Econ 41(2):343–386

Allen DW, Lueck D (2004) The nature of the farm: contracts, risk, and organization in agriculture. MIT Press, Cambridge

Baker GP, Hubbard TN (2003) Make versus buy in trucking: Asset ownership, job design, and information. Am Econ Rev 93(3):551–572

Balazs K (2001) Some like it haute: leadership lessons from France’s great chefs. Organ Dyn 30(2):134–134

Balazs K (2002) Take one entrepreneur: the recipe for success of France’s great chefs. Eur Manag J 20(3):247–259

Barzel Y (1982) Measurement cost and the organization of markets. J Law Econ 25(1):27–48

Barzel Y (1987) The entrepreneur’s reward for self-policing. Econ Inq 25(1):103–116

Becker GS, Murphy KM (1992) The division of labor, coordination costs, and knowledge. Q J Econ 107(4):1137–1160

Cheung SN (1968) Private property rights and sharecropping. J Polit Econ 76(6):1107–1122

Cheung SN (1983) The contractual nature of the firm. J Law Econ 26(1):1–21

Chossat V, Gergaud O (2003) Expert opinion and gastronomy: the recipe for success. J Cult Econ 27(2):127–141

Clay K (1997) Trade without law: private-order institutions in Mexican California. J Law Econ Organ 13(1):202–231

Cole B (2018) The renaissance artist at work: from Pisano to Titian. Routledge, London

Etro F (2018) The economics of Renaissance art. J Econ Hist 78(2):500–538

Fama EF, Jensen MC (1983) Separation of ownership and control. J Law Econ 26(2):301–325

Ferguson PP (1998) A cultural field in the making: Gastronomy in 19th-century France. Am J Sociol 104(3):597–641

Garicano L, Hubbard TN (2009) Specialization, firms, and markets: the division of labor within and between law firms. J Law Econ Organ 25(2):339–371

Gergaud O (2017) Michelin: quand distinction rime avec pression. Harvard Business Review France. https://www.hbrfrance.fr/chroniques-experts/2017/11/17906-michelin-distinction-rime-pression/.

Gergaud O, Guzman LM, Verardi V (2007) Stardust over Paris gastronomic restaurants. J Wine Econ 2(1):24–39

Gergaud O, Storchmann K, Verardi V (2015) Expert opinion and product quality: evidence from New York City restaurants. Econ Inq 53(2):812–835

Greif A (1993) Contract enforceability and economic institutions in early trade: the Maghribi traders’ coalition. Am Econ Rev 83(3):525–548

Grossman SJ, Hart OD (1986) The costs and benefits of ownership: a theory of vertical and lateral integration. J Polit Econ 94(4):691–719

Hart O, Moore J (1990) Property rights and the nature of the firm. J Polit Econ 98(6):1119–1158

Holmstrom B, Milgrom P (1991) Multitask principal-agent analyses: incentive contracts, asset ownership, and job design. J Law Econ Organ 7:24–52

Johnson C, Surlemont B, Nicod P, Revaz F (2005) Behind the stars: a concise typology of Michelin restaurants in Europe. Cornell Hotel Restaur Admin Q 46(2):170–187

Kaufmann PJ, Lafontaine F (1994) Costs of control: the source of economic rents for McDonald’s franchisees. J Law Econ 37(2):417–453

King G, Zeng L (2001) Logistic regression in rare events data. Polit Anal 9(2):137–163

Klein B (1995) The economics of franchise contracts. J Corp Financ 2(1–2):9–37

Klein B, Leffler KB (1981) The role of market forces in assuring contractual performance. J Polit Econ 89(4):615–641

Leeson PT (2007) Trading with bandits. J Law Econ 50(2):303–321

Matus V (2007) Bam! Wkly Stand 13(7):13–17

Ottenbacher M, Harrington RJ (2007) The innovation development process of Michelin-starred chefs. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 19(6):444–460

Rao H, Monin P, Durand R (2003) Institutional change in Toque Ville: Nouvelle cuisine as an identity movement in French gastronomy. Am J Sociol 108(4):795–843

Rao H, Monin P, Durand R (2005) Border crossing: bricolage and the erosion of categorical boundaries in French gastronomy. Am Sociol Rev 70(6):968–991

Ruhlman M (2009) The making of a chef: mastering heat at the Culinary Institute of America. Holt Paperbacks, New York

Shapiro C (1982) Consumer information, product quality, and seller reputation. Bell J Econ 13(1):20–35

Shapiro C (1983) Premiums for high quality products as returns to reputations. Q J Econ 98(4):659–679

Simester DI, Wernerfelt B (2005) Determinants of asset ownership: a study of the carpentry trade. Rev Econ Stat 87(1):50–58

Snyder W, Cotter M (1998) The Michelin Guide and restaurant pricing strategies. J Restaur Foodserv Mark 3(1):51–67

Spang RL (2001) The invention of the restaurant. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Trubek AB (2000) Haute cuisine: how the French invented the culinary profession. The University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia

U.S. Census Bureau (2014) 2012 economic census. U.S. Department of Commerce, Washington

Wernerfelt B (2002) Why should the boss own the assets? J Econ Manag Strategy 11(3):473–485

Williamson OE (1983) Credible commitments: using hostages to support exchange. Am Econ Rev 73(4):519–540

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge Yoram Barzel, Caleb Fuller, and Clara Jace for helpful comments. An early draft was presented at the Free Market Institute Research Seminar at Texas Tech University and the 2019 Southern Economic Association Meetings. Chef Luigi Pomata was kind enough to introduce me to some of the most treasured secrets of his trade. Regrettably, he did not ask me to stay for lunch.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Piano, E. . Organizing high-end restaurants. Econ Gov 22, 165–192 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-021-00253-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-021-00253-y