Abstract

The measurements of one of the major greenhouse gases, carbon dioxide (CO2), are being made using dedicated satellite remote sensing since the launch of the greenhouse gases observing satellite (GOSAT) by a three-way partnership between the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), the Ministry of Environment (MoE) and the National Institute for Environmental Studies (NIES), and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2). In the past 10 years, estimation of CO2 fluxes from land and ocean using the earth system models (ESMs) and inverse modelling of in situ atmospheric CO2 data have also made significant progress. We attempt, for the first time, to evaluate the CO2 fluxes simulated by an earth system model (MIROC-ES2L) and the fluxes estimated by an inverse model (MIROC4-Inv) using in situ data by comparing with GOSAT and OCO-2 observations. Both MIROC-ES2L and MIROC4-Inv fluxes are used in the MIROC4-atmospheric chemistry transport model (referred to as ACTM_ES2LF and ACTM_InvF, respectively) for calculating total column CO2 mole fraction (XCO2) that are sampled at the time and location of the satellite measurements. Both the ACTM simulations agreed well with the GOSAT and OCO-2 satellite observations, within 2 ppm for the spatial maps and time evolutions of the zonal mean distributions. Our results suggest that the inverse model using in situ data is more consistent with the OCO-2 retrievals, compared with those of the GOSAT XCO2 data due to the higher accuracy of the former. This suggests that the MIROC4-Inv fluxes are of sufficient quality to evaluate MIROC-ES2L simulated fluxes. The ACTM_ES2LF simulation shows a slightly weaker seasonal cycle for the meridional profiles of CO2 fluxes, compared with that from the ACTM_InvF. This difference is revealed by greater XCO2 differences for ACTM_ES2LF vs GOSAT, compared with those of ACTM_InvF vs GOSAT. Using remote sensing–based global products of leaf area index (LAI) and gross primary productivity (GPP) over land, we show a weaker sensitivity of MIROC-ES2L biospheric activities to the weather and climate in the tropical regions. Our results clearly suggest the usefulness of XCO2 measurements by satellite remote sensing for evaluation of large-scale ESMs, which so far remained untested by the sparse in situ data.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is the most important anthropogenically produced greenhouse gas (Myhre et al. 2013). During 2009–2018, CO2 emissions associated with human activities, such as the burning of fossil fuel and cement manufacturing contributed about 100 PgC (1 Pg = 1015 g) or about 10 PgC/year to the atmosphere (Friedlingstein et al. 2020). Based on available statistics (Janssens-Maenhout et al. 2019), about 60% of these emissions originate from the northern extratropics, mainly by the Annex 1 countries of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), signatories to the Kyoto Protocol subject to caps on greenhouse gases (GHGs) emissions. The inventory emissions from the non-Annex I countries are rising quickly due to their rapid economic growth and shifting manufacturing from the Annex I or Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) member countries to the so-called BRICS countries (i.e. Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa). Uncertainties in the emissions are larger for non-Annex I counties relative to the Annex I countries (Andres et al. 2012). This leads to lower confidence of our knowledge of the changes in terrestrial biospheric fluxes in response to climate change and climate variabilities, and CO2 fertilisation feedbacks (Ainsworth and Rogers 2007; Keenan et al. 2013; Saeki and Patra 2017; Bastos et al. 2020).

CO2 emissions to the atmosphere from land-use change (LUC), predominantly caused by human-driven deforestation and cropland development, is estimated to be in the range of 1–2 PgC/year for the period 2009–2018 (Hansis et al. 2015; Houghton and Nassikas 2017; Kondo et al. 2020; Friedlingstein et al. 2020). The uncertainties in LUC CO2 emission estimations are originated from the treatment of various terrestrial carbon pools of above and below ground biomass and soil carbon (Houghton and Nassikas 2017; Kondo et al. 2020). Due to an increase in these anthropogenic emissions, the atmospheric CO2 concentration is rising at an average rate of 3 ppm/year during 2009–2018 (Tans and Keeling 2019). This is less than half of the rate that is expected from all anthropogenic emissions. About 29% of the anthropogenic emissions are taken up by the land ecosystems due to the greater availability of CO2 in the atmosphere thereby increasing water use efficiency by the plants (Keeling et al. 2017). About 23% is being absorbed by the oceans as the partial pressure of CO2 increases faster in the atmosphere than in the surface ocean (DeVries et al. 2019). Uncertainties prevail on the regions and process of CO2 uptakes by the land and ocean ecosystems (Graven et al. 2013; Zeng et al. 2014; Forkel et al. 2016; McKinley et al. 2020).

In the Paris Agreement, parties to the UNFCCC reached a landmark agreement to combat climate change and to accelerate and intensify efforts to reduce the rate of atmospheric CO2 build-up to limit the increase of the Earth’s global-mean surface air temperature to below 2 °C by 2100 (https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/paris-agreement). Meeting this goal will depend very strongly on the land-ocean-atmosphere feedbacks in the future (Ciais et al. 2013). One of the urgent questions is whether or not the terrestrial biosphere and the oceanic systems will continue to absorb and store CO2 from the atmosphere in the future, particularly when the emission mitigation goals of net-zero or negative emissions are achieved in the later-half of the century (Jones et al. 2019). For this purpose, comprehensive Earth System Models (ESMs) have been developed that account for the past behaviours of the terrestrial and oceanic climate systems, coupled with the carbon and nutrients cycles (Jones et al. 2016; Arora et al. 2019; Hajima et al. 2020). The ESM simulated land/ocean-atmosphere CO2 fluxes are relatively untested in comparison with the atmospheric constraints (Wenzel et al. 2016), while the CO2 fluxes simulated by the dynamic global vegetation models (DGVMs) are recently benchmarked with the global remote sensing CO2 data products or climate parameters (Calle et al. 2019; Collier et al. 2018).

The main goal of this study is thus to evaluate the CO2 fluxes simulated using one such ESMs, the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC)’s Model for Interdisciplinary Research on Climate (MIROC)-based Earth System Simulation version 2 (referred to as MIROC-ES2L) (Hajima et al. 2020). As the in situ measurements are often affected by local weather conditions and spatial coverage is sparse, the global ESM simulations of CO2 will not be adequately assessed by comparing with in situ data. With the advent of satellite remote sensing by the dedicated instruments for CO2 measurements, we now have global coverage of CO2 concentrations since 2009 (Yoshida et al. 2013). In addition, the overall consistency of ACTM simulations with total column measurements and in situ measurements has already been established (Patra et al. 2017). This has allowed us here to check the performance of MIROC-ES2L simulations for the recent 5 years (2009–2014) using the historical Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) climate drivers, which are available only up to 2014 as per the CMIP6 protocol. We also compare the MIROC-ES2L simulation results with an inversion estimation of CO2 fluxes using in situ CO2 measurements and the MIROC4-ACTM simulation (Saeki and Patra 2017; Patra et al. 2018; Friedlingstein et al. 2020). We reiterate that the in situ data have superior accuracy than the satellite retrievals of XCO2, and the satellite retrievals, while perfectly suitable for the objectives of this paper, are still maturing.

The details of the materials and method for MIROC-ES2L evaluation are given in Section 2. In Section 3 (Results and discussion), we first compare the fluxes from MIROC4-Inv and MIROC-ES2L. Then XCO2 simulations by using both the fluxes are evaluated using GOSAT and OCO-2 observations, in order to evaluate the quality of MIROC4-Inv fluxes based on sparse in situ observations and check the applicability for evaluating the MIROC-ES2L simulations. Recently, the GOSAT XCO2 measurements are being used for the evaluation of the ESM simulation results at monthly time intervals (Gier et al. 2020), but our analysis uses a common transport model for simulating the fluxes before comparison. Here, the model XCO2 is constructed by sampling the MIROC4-ACTM simulated CO2 vertical profiles at the observation location and time, and by applying the satellite a priori corrections and column averaging kernels (Section 2). Conclusions are given in Section 4.

2 Methods

2.1 Greenhouse gases observing SATelite, retrieval version 02.81

The Greenhouse gases Observing SATelite (GOSAT), nicknamed “Ibuki”, was launched on 23 January 2009 (Hamazaki et al. 2004; Yokota et al. 2009). GOSAT has been making measurements of XCO2 since April 2009. GOSAT measurement precision and the retrieved XCO2 accuracy have been improving since the first set of retrievals was released (Yoshida et al. 2013). We have used the latest retrievals, version General User 02.81 (GOSAT_v2.81; https://data2.gosat.nies.go.jp/index_en.html), which are bias uncorrected, but validated using XCO2 from upward-looking FTS network (TCCON—Total Carbon Column Observing Network) (Wunch et al. 2017) (see updates in https://data2.gosat.nies.go.jp/doc/documents/ValidationResult_FTSSWIRL2_V02.81_GU_en.pdf). GOSAT data are provided for XCO2, a priori profiles, and column averaging kernels (both at 15 pressure layers). Although the bias-corrected data should be more comparable with the model simulations (earlier retrieval version 02.72), we have preferred to use the newest retrieval version which has better physical characteristics. The single-shot precision of GOSAT measurements is estimated to be 2.17 ppm.

2.2 Orbiting carbon observatory, retrieval version 9r

The Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2) was launched on 04 July 2014 and retrievals are available since September 2014 (Crisp et al. 2017; Eldering et al. 2017). We have used bias-corrected retrievals, version 9r (OCO-2_v9r) (Updated Lite files from https://co2.jpl.nasa.gov/#mission=OCO-2) (O’Dell et al. 2018). OCO-2 data are available for XCO2, a priori profiles (20 levels), and column averaging kernels (20 pressure levels). Data with a quality flag of 0 (best data) are used in the analysis. The data coverage of OCO-2 (approximately 10 million data points annually) is much greater than that of GOSAT (approximately 0.1 million data points annually). The single-shot accuracy of OCO-2 retrievals is estimated to be 1.3 ppm over land and 1 ppm over ocean (Kulawik et al. 2020). The better quality of the XCO2 data from OCO-2 (compared with bias uncorrected GOSAT_v2.81), although without an overlap with the MIROC-ES2L simulation, provides us an assessment of the retrieval data quality on evaluation of the CO2 flux models.

In this article, the GOSAT and OCO-2 XCO2 retrievals are referred to as XCO2 observations, which are retrieved from a remote sensing signal and rely on a radiative transfer model with uncertainties.

2.3 MIROC earth system model version 2 for long-term simulations and evaluation using remote sensing observations

MIROC-ES2L is the latest generation of earth system model (ESM) that is developed at the JAMSTEC, in collaboration with Tokyo University and the National Institute for Environment Studies (NIES). The ESM has fully coupled terrestrial-ocean-atmosphere model components for simulating the evolutions of carbon-nitrogen cycles and climate for the past centuries and centuries to millennium-term future projection (Hajima et al. 2020). The horizontal resolution of the atmosphere is T42 spectral truncation (approximately 2.8° intervals for latitude and longitude) and the vertical resolution is 40 layers up to 3 hPa with a hybrid σ–p coordinate; the ocean grid system consists of horizontally 360 × 256 grids with 62 vertical layers.

The terrestrial carbon cycle component covers major processes relevant to the global carbon cycle, with vegetation (leaf, stem, and root), litter (leaf, stem, and root), and humus (active, intermediate, and passive) pools and with a static biome distribution. Photosynthesis or gross primary productivity (GPP) is simulated based on the Monsi–Saeki theory (Monsi and Saeki 1953), and the allocation of photosynthate between carbon pools in vegetation (e.g. leaf, stem, and root) is regulated dynamically following phenological stages. The transfer of vegetation carbon into litter–soil pools is simulated using constant turnover rates, and in deciduous forests, seasonal leaf shedding occurs at the end of the growing period. The perturbation from the land-use change on the terrestrial carbon cycle is simulated by the transition of 5 types of land-use tiles (primary vegetation, secondary vegetation, urban, crop, and pasture) in a grid; e.g. deforestation processes are represented by the reduction in area fraction of primary/secondary vegetation (and increase of less-vegetated land-use tile like urban), and deforested carbon is gradually lost to the atmosphere. Details on carbon cycle processes in the model can be found elsewhere (Ito and Oikawa 2002; Hajima et al. 2020).

In the Ocean ecosystem component Embedded within the ocean circulation model (OECO2), ocean biogeochemical dynamics are simulated with 13 biogeochemical tracers (three types of nutrients, four biological tracers, four carbon and/or calcium, and other two inorganic tracers). The carbon cycle processes are simulated following the biogeochemical dynamics of the tracers, assuming that all organic materials have an identical elemental stoichiometric ratio. Ocean ecosystem dynamics are simulated based on the nutrient cycles of nitrate, phosphorous, and iron. The nutrient concentration, in conjunction with the controls of seawater temperature and the availability of light, regulates the primary productivity of the phytoplankton. In the model, zooplankton is assumed to be independent of abiotic conditions (e.g. seawater temperature) and dependent on biotic conditions (phytoplankton and zooplankton concentrations). Detritus contains nitrate, phosphorus, iron, and carbon, most of which is remineralized while sinking downward. A fraction of the detritus that reaches the ocean floor is removed from the system. The formulations of atmosphere–ocean gas exchange, carbon chemistry, and related parameters follow protocols from the Ocean Model Intercomparison Project (OMIP) (Orr et al. 2017).

The basic performance of the land and ocean carbon cycle is assessed by comparing the simulated spatial patterns with observation data for land (gross primary production, vegetation carbon, and soil carbon for the land component) and ocean (primary production, export production, atmosphere-ocean CO2 flux, dissolved inorganic carbon) (Hajima et al. 2020). Hajima et al. (2020) also showed that atmosphere-land or ocean CO2 fluxes in cumulative value (i.e. the changes in land or ocean amount) in the period of 1850–2014 are within the estimated range suggested by Le Quéré et al. (2018), although the GPP seasonality in land tropics and CO2 flux seasonality in the Southern Ocean and the North Atlantic Ocean requires improvement. The feedback strengths of carbon cycle processes, which are associated with the magnitude of natural carbon sinks in response to atmospheric CO2 concentration and climate change, are also quantified and compared with other ESMs, showing MIROC-ES2L has the intermediate values for the feedback parameters (Arora et al. 2020).

The original historical simulation of MIROC-ES2L is obtained from the CMIP6 exercise (Eyring et al. 2016; Hajima et al. 2020), where the model is driven by anthropogenic fossil fuel CO2 emission, other GHGs and aerosol emissions/concentrations, natural forcing like solar irradiance change and volcanic events, and land-use change. The CO2 concentration is explicitly simulated by the model based on the external forcing of anthropogenic CO2 emission, simulated land and ocean CO2 sink, and simulated LUC-derived CO2 emission (the experimental configuration in which CO2 concentration is prognostically simulated by models is called “emission-driven” mode, while the configuration in which CO2 concentration is prescribed as forcing data is called “concentration-driven” mode) (Jones et al. 2016). The simulation period was 1850–2014, following a continuous 2483 spin-up years by the “concentration-driven” mode and 691 years by the “emission-driven” mode. The accuracy of future prediction by the ESMs is likely to depend on the quality of the historical simulation of the carbon-nitrogen-climate feedbacks and the model response to external forcing (e.g. terrestrial response to land-change forcing). However, the sparse in situ measurements and smaller flux footprint of the surface sites limited the evaluation of the historical simulations by the ESMs. The situation has now changed because of the global coverage of XCO2 measurements from space (GOSAT and OCO-2), which are explored in this study for an evaluation of the MIROC-ES2L historical simulation.

2.4 MIROC atmospheric chemistry transport model

The MIROC (version 4)-based atmospheric chemistry transport model (MIROC4-ACTM) simulations are conducted at horizontal resolution of T42 spectral truncations with 67 hybrid pressure layers in vertical. The greater number of vertical layers covering the altitude range from Earth’s surface to 0.0128 hPa or about 80 km, and closely spaced levels in the upper troposphere and lower stratosphere region is designed for better representation of the vertical profiles of long-lived gases in the Earth’s atmosphere. MIROC4-ACTM (Patra et al. 2018; Watanabe et al. 2011) simulated horizontal winds and temperature are nudged to the Japanese 55 year reanalysis or JRA55 (Kobayashi et al. 2015), is well validated for large-scale interhemispheric transport using sulphur hexafluoride (SF6) and the Brewer-Dobson circulation patterns using the age of air derived from CO2 and SF6 (Patra et al. 2018). Thus we expect better simulations of XCO2 by accounting for the accurate meridional and vertical profiles of CO2. However, the convective (weekly or shorter time scale) transport remained invalidated due to the lack of appropriate observational parameters, e.g. Radon-222 with a radioactive decay lifetime of 3.8 days (Patra et al. 2018).

We use monthly mean CO2 fluxes from JAMSTEC’s time-dependent inversion model for this analysis (Saeki and Patra 2017; Friedlingstein et al. 2020). The inverse model estimated CO2 fluxes (referred to as MIROC4_Inv) for 84 regions of the globe using the MIROC4-ACTM simulations and in situ CO2 observations at 30 sites around the globe (Fig. 1). The atmospheric data are provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Cooperative Air Sampling Network (Dlugokencky and Tans 2019), and the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) (Tsuboi et al. 2013). A priori MIROC4-ACTM simulations are conducted using interannually varying emissions due to fossil-fuel and cement production (FFC) from the global carbon project (Friedlingstein et al. 2020), climatological monthly mean terrestrial and oceanic fluxes from the Carnegie-Ames-Stanford Approach (CASA) land model, and upscaling model of air-sea CO2 flux measurements, respectively (Randerson et al. 1997; Takahashi et al. 2009). Thus, the interannual variabilities in the land and ocean regional fluxes estimated by the inverse model are driven entirely by the signals in observed CO2 variabilities at 30 sites. The simulated CO2 concentrations from the MIROC4_Inv fluxes compare well with the other atmospheric inversion models when evaluating against independent airborne measurements (Friedlingstein et al. 2020).

Regional divisions of land (15) and ocean (11), along with their names, for time series analysis shown by the map. The in situ measurement sites used in the MIROC4-ACTM inversion are shown by triangles and marked by their 3-letter site abbreviation, as per the World Meteorological Organisation – World Data Centre for Greenhouse Gases (WMO-WDCGG). CO2 data for 28 sites are taken from NOAA (https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/flask.php), and data for YON and MNM are taken from JMA (https://gaw.kishou.go.jp/)

2.5 Preparation of model XCO2 data and processing of the gridded maps and time series

Here, in order to simultaneously evaluate both the XCO2 and CO2 fluxes simulated by MIROC-ES2L, we first made two types of MIROC4-ACTM simulations—one is driven by the CO2 fluxes of MIROC-ES2L and the other is by MIROC4_Inv flux; the simulations are referred to as ACTM_ES2LF and ACTM_InvF, respectively. Thus, the atmospheric CO2 transport, driven by JRA55 reanalysis, is common for both simulations. This experimental setting allows us to make a direct comparison of XCO2 in both simulations with that of satellite monitoring. The model simulations by MIROC4-ACTM are archived at hourly time resolution and sampled for the GOSAT and OCO-2 measurement locations by linear interpolations in horizontal grid and time (Patra et al. 2017). The model simulations are then convolved with satellite a priori (CO2prior) and column averaging kernels (Ai) after calculating their respective pressure levels (Pi; where i is the index for retrieval pressure layers; 20 for OCO-2 and 15 for GOSAT) from the original ACTM vertical grids (67 hybrid). Thus, the ACTM simulated XCO2 are

where dPi is the pressure weighting function (Rodgers and Connor 2003).

Both the simulations using MIROC4-Inv and MIROC-ES2L fluxes are spin-up from 1996–2009, so that the CO2 concentration responses to the flux changes near the Earth’s surface propagates throughout the atmosphere, as high as the model top of about 90km. This is important because the XCO2 measurements capture the total columns and there are systematic CO2 gradients in the stratosphere and mesosphere that are season dependent, and lags more than 6 years for the concentration increase rate in the troposphere. Both the model concentrations are adjusted for initial values so that the global mean concentrations agree with the GOSAT observations on 01 January 2010. This is a valid approximation because we do not consider any chemical production or loss of CO2 in the models, thus the concentration increases are consistent with the flux evolution (Basu et al. 2018). The initial value adjustment helps to put all plots on identical XCO2 scales.

All the XCO2 results are gridded to a 2.5° × 2.5° latitude–longitude grid for further analysis (Patra et al. 2017). Time series analyses are conducted by further aggregating XCO2 data for the 15 partitions of the land and 11 ocean regions as marked by the maps in Fig. 1. The model data differences and agreements are quantified by comparing the growth rates and seasonal cycles between the observed and simulated XCO2, following decomposition of the time series using a harmonic analysis (Thoning et al. 1989). We fitted 4 harmonics to each of the regionally aggregated time series for deriving a long-term trend and a fitted time series. The seasonal cycles are calculated as fitted–trend time series, and the growth rate is calculated as a time derivative of the trend time series.

2.6 Leaf area index and gross primary productivity

The LAI, one-sided green leaf area per unit horizontal ground surface (m2 m−2), is one of the main drivers of primary production in the ESMs (Anav et al. 2015). LAI defines the canopy structure and functions of the biosphere, influenced by the weather and climate of the region. Thus, the LAI and GPP together allow us to diagnose basic ecosystem functioning for carbon assimilation in MIROC-ES2L. Although solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence data can be used as an indicator of GPP (Wu et al. 2016; Doughty et al. 2019), we did not use it since the data cannot be compared with GPP directly. We used LAI from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) Collection 6 (Yan et al. 2016) and GPP from FLUXCOM, a CO2 flux upscaling inter-comparison project (Tramontana et al. 2016). The MODIS LAI product with the original 500 m resolution was aggregated globally based on the same quality control with Ichii et al. (2017) and averaged over the T42 spatial resolution for comparison with MIROC-ES2L results. The FLUXCOM GPP product (Jung et al. 2020) was generated by an ensemble of estimations by multiple machine-learning algorithms with eddy-covariance CO2 flux observation network (FLUXNET) and MODIS land products (Tramontana et al. 2016). The original 1/12 degree resolution data were converted to the T42 spatial resolution.

3 Results and discussion

Figure 2 shows the time series of CO2 fluxes for the land biosphere, ocean exchange, and FFC emissions. We also show the time evolution of the meridional land and ocean CO2 fluxes as simulated by the MIROC-ES2L and MIROC4-Inv (right column). The results show global total land and ocean CO2 fluxes are increasing with time and offset about 44 ± 6% of the FFC emissions during the period 2009–2018, as seen from the latest Global Carbon Budget (GCB) (Friedlingstein et al. 2020). In general, the cumulative fluxes by MIROC-ES2L (− 16.0, − 10.1, and 46.7 PgC for land, ocean, and FFC, respectively) and MIROC4-Inv (− 14.4, − 8.1, and 46.3 PgC for land, ocean, and FFC, respectively) are in good agreement for the overlapping GOSAT observation period of 2010-2014. These fluxes are also in good agreement with the GCB’s cumulative flux estimates − 13.3, − 8.4, and 47.0 PgC for land (land sink – land-use source + riverine export), ocean (ocean sink – riverine export), and FFC, respectively, during 2009–2014. For this comparison, we have corrected the GCB land and ocean fluxes for riverine export (Resplandy et al. 2018), i.e. 0.78 PgC year−1 is added to the land sink and removed from the ocean sink for this comparison because the inversion and ESM fluxes are used in the ACTM simulations for atmospheric CO2 without any spatial adjustment for riverine export flux. While the GCB underestimate sinks (“budget imbalance”) (Saeki and Patra 2017; Bastos et al. 2020), we find here that the MIROC-ES2L fluxes marginally overestimate the cumulative sink compared with the inversion estimated CO2 sink. The inversion fluxes by design reproduce the observed growth rates in atmospheric CO2. In the ACTM simulation of atmospheric CO2, a bias of 1 ppm is produced per 2.12 PgC of flux imbalance.

Time series of global (left column) and semi-hemispheric (right column) total CO2 fluxes for land and ocean at annual intervals as estimated by the MIROC4-Inv and MIROC-ES2L (panels a and b, respectively). The FFC emissions from independent data sources are also compared (panel c). The global total results are compared with GCP-CO2 budgets (Friedlingstein et al. 2020). The semi-hemispheric biospheric fluxes of land and ocean regions as well as the FFC emissions are shown (right column), for the northern hemisphere (NH) extratropics, tropics, and southern hemisphere (SH) extratropics (panels d–f, respectively). Please note the different y-axis range for each panel (the ocean flux variability in panel b may appear deceivingly large compared with the land flux variability in panel a)

The magnitude of interannual variations and trends in CO2 fluxes are in good agreement between the 3 different estimations for the global land but are at a lower agreement for the global ocean (Fig. 2a, b). Nevertheless, the land and ocean show similar increasing long-term trends in CO2 uptake (more negative flux in the recent years), except for the anomalous period of 1996–2002 for MIROC4-Inv. Although this anomalous period is included in the ACTM simulation spin-up, the simulated CO2 concentrations for 2009 and later will be largely unaffected. The agreements between mean fluxes from MIROC4-InvF and MIROC-ES2L at 3 broad latitude bands (Fig. 2d–f) are excellent except for the land in the southern hemisphere (SH) extratropics. The SH land flux is estimated at about − 0.5 PgC year−1 by MIROC-InvF during 2009–2014 compared with very weak negative flux by MIROC-ES2L (Fig. 2f). It has to be seen whether or not such differences in fluxes are validated/invalidated by the GOSAT and OCO-2 observations. Please bear in mind that the phase of interannual variability of CO2 fluxes by MIROC-ES2L is not expected to match the phasing of interannual climate variability of the real world (e.g. El Niño–Southern Oscillation). Thus, MIROC4-Inv and MIROC-ES2L disagree on the phases of interannual variability of CO2 fluxes. However, the magnitude of land flux interannual variabilities for MIROC4-Inv (0.86 PgC year−1, 1-σ standard deviation for the period 1996–2014 after detrending) and MIROC-ES2L (0.85 PgC year−1) are in good agreement, but the global ocean flux interannual variabilities are underestimated largely by MIROC-ES2L (0.09 PgC year−1) compared with that for MIROC4-Inv (0.32 PgC year−1).

The seasonal variation of fluxes at different latitude grid are more variable in the case of the MIROC4-Inv and MIROC-ES2L (Fig. 3). We find that the CO2 flux seasonalities are in a good match in the latitudes north of 30°N, but the cycle of outgassing and uptake in the latitude bands of 30°S-Eq and Eq-30°N are contrasting between the two flux models. The MIROC-ES2L underestimates CO2 uptake in the latitude band of 55°S–30°S and shows no CO2 degassing in cold season around 60°S along the coast of Antarctica, when compared with the MIROC4-Inv fluxes. For the simulation of XCO2, we expect to see different phasing and amplitude of seasonal cycle simulated using the inversion and ESM fluxes, particularly over the tropical and southern hemispheric regions.

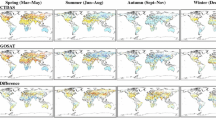

Figure 4 shows examples of XCO2 distributions as observed by GOSAT and OCO-2 for the year 2014 and 2016, respectively. Note that OCO-2 does not have full-year coverage of measurements for 2014. The data density has been significantly increased in the case of OCO-2 retrievals. We also see that the model–observation differences are generally lower for OCO-2 and ACTM_InvF compared with the differences between GOSAT and ACTM_InvF, particularly over the ocean regions. The GOSAT sun glint observations are known to have additional retrieval bias relative to those over the land surfaces and produce greater inconsistency when compared with transport model simulations (Patra et al. 2017; Schuh et al. 2019; Yoshida et al. 2013). Both our models systematically overestimated XCO2 concentrations over Asia around the latitude 45°N, which could either arise from high bias in FFC CO2 emissions over China (Saeki and Patra 2017) or underestimation of sinks over the regions (Wang et al. 2020). For both the simulations, XCO2 over the tropical land regions, except over India, are underestimated (negative differences) while the XCO2 over the ocean basins are systematically overestimated (positive differences) (Fig. 4b, c). The overestimations over ocean are more prominent in the southern extratropics.

Figure 5 shows the latitude–time distributions of zonal-mean XCO2 for the period of GOSAT and OCO-2 measurement period. Both models are compared with GOSAT for the period 2009–2014 and only ACTM_InvF results are compared with OCO-2 due to the unavailability of ACTM_ES2LF simulations for the recent years. In general, the model simulations are within 2 ppm of the observed XCO2 concentrations. The fact that the ACTM_InvF simulation better agrees with GOSAT XCO2 suggests an overall consistency of the in situ measurements with those from the satellites. Figure 5 c and e show that the model-observation agreements have improved compared with those using earlier versions of retrievals for both GOSAT and OCO-2, especially at the high-latitude edges (Patra et al. 2017). The ACTM_InvF better simulates the time evolution because the fluxes are optimised using in situ data, while the free-running fluxes in ACTM_ES2LF marginally underestimated the XCO2 increase rate with time due to slightly stronger global total CO2 sinks in the years 2010–2014, compared with the inversion fluxes (Fig. 2). In the latitude range around 20°S, the seasonal bias in ACTM_ES2L simulated XCO2 is maximum with positive values in austral autumn and negative values in the austral spring, reflecting tendencies of weaker sink to source and weaker source to sink during the two seasons, respectively, in the MIROC-ES2L fluxes compared with the MIROC4_Inv fluxes (Fig. 3).

We find that the ACTM_InvF–GOSAT shows greater differences in the periods since 2015, which may arise from insufficient accuracy of the degradation correction of the TANSO-FTS without accounting for switching of the pointing system in January 2015 (Kuze et al. 2016). The differences are greater over the water surface than the land surface (Figs. S1 and S2). The instrumental degradation correction is suspected more than the retrieval physics uncertainties because the characteristics of surface reflectance are better modelled over the water bodies than that over the land.

The model-observed regional biases in XCO2 (Table 1) provide an indication of how well the flux models simulated the regional fluxes. Because the GOSAT_v2.81 data are not bias corrected, the agreement between ACTM_InvF with GOSAT (biases greater than 0.12 ppm for 16 out of 26 regions and are less than 1 ppm) is much greater than those for ACTM_InvF and OCO-2 (biases typically below 0.12 ppm except for 3 out of 26 regions). Generally, the regional biases are greater for ACTM_ES2LF and GOSAT_v2.81 (only 6 out of 26 regions have bias less than 0.12 ppm). The biases are systematically positive for Boreal America and Asia, in contrast to strongly negative for the Southern Ocean (poleward of 45°S). These biases will be better assessed in the future by using newer simulations by MIROC-ES2L and updated GOSAT/GOSAT2 and OCO-2/OCO-3 retrievals.

The mean growth rates for the model and observed time series (not shown in Table 1 for clarity) suggest that the ACTM_ES2LF simulation (2.01 ± 0.09 ppm year−1 for 2010–2014) slightly underestimated the GOSAT growth rates (2.13 ± 0.25 ppm year−1 for 2010–2014) over all the regions. This growth rate mismatch of 0.11 ppm year−1 is equivalent to a sink bias of 0.25 PgC year−1 for MIROC-ES2L fluxes (1 ppm = 2.12 PgC in MIROC4-ACTM). As the inversion fluxes are optimised using the surface CO2 measurements the mean growth rate from ACTM_InvF (2.32 ± 0.04 ppm year−1 for 2010–2018) agrees well with that of the GOSAT (2.27 ± 0.09 ppm year−1 for 2010–2018). The differences in growth rates between the regions are small because CO2 is well mixed in the atmosphere, and also the region-to-region differences are greater over a shorter time period, e.g. for the case of GOSAT during 2010–2014, because of the impacts of regional climate variabilities on the CO2 flux (Patra et al. 2005).

Figure 6 shows the importance of greater observational data coverage, for conducting better inversion of regional CO2 sources and sinks, e.g. the mismatch between the seasonal cycle phase and amplitude over Southern Africa is more evident than Temperate North America. Assuming that the XCO2 are strongly sensitive to the regional and hemispheric flux gradients we find the ACTM_ES2LF simulation shows large mismatches in the seasonal cycle phase and amplitudes in the tropical southern hemisphere to the southern extratropics (Table 1; Animation S1 and S2 for GOSAT and OCO-2, respectively). The seasonal cycle correlations are found to be the smallest over Southern Africa (r = 0.04), Tropical Africa (r = 0.24), and Brazil (0.38). This suggests that the MIROC-ES2L fluxes are not simulated well over the tropical land regions and southern hemisphere in general (seen as the contrast between the MIROC4-Inv and MIROC-ES2L CO2 fluxes in Fig. 3). Since the transport is common in both the ACTM simulations, we attribute the ACTM_ES2LF–GOSAT mismatches to the surface fluxes rather than the model transport uncertainty, due to the deep cumulus convection in the tropics (Remaud et al. 2018).

Time series XCO2 for 4 selected parts of the world. Values are aggregated over the regions highlighted by yellow. The detailed results for 15 land and 11 ocean regions are shown for the time series, ACTM_InvF/ACTM_ES2L-GOSAT, and their detrended seasonal cycles (GIF Animation S1). Comparisons with OCO-2 data are also shown in supporting materials (GIF Animation S2)

Better seasonal cycle correlations for South Asia (r = 0.60) or Southeast Asia (r = 0.79) could arise due to the far-field influence from the northern extratropics, where the fluxes are better modelled. It is typical that the terrestrial biosphere models are better parameterised for biogeochemical cycles of the temperate regions (temperature/radiation controlled), compared with the regions over tropical regions, where the carbon cycle is very strongly limited by water availability under the weaker seasonal temperature variations (Gloor et al. 2012; Patra et al. 2013; Haverd et al. 2013; Sitch et al. 2015; Jones et al. 2020). The tropical and temperate regions also have different characteristics of nitrogen and phosphorus limitations (Zaehle et al. 2010; Fleischer et al. 2019). The issue of poor seasonal cycle simulation by MIROC-ES2L is addressed later using empirically derived LAI and GPP.

Further, we checked the meridional variations of multi-year mean peak-to-trough seasonal cycle amplitudes (SCAs) for XCO2 over the land and ocean regions separately (Fig. 7). The interannual variabilities, seen as the vertical error bars, are generally smaller than 0.5 ppm in most latitudes, except over the ocean in the latitudes poleward of 40°N which show persistently greater than 1 ppm (Fig. 7d). We find distinct features for the comparisons over the land and ocean which helps us to identify the possible link between the surface CO2 fluxes over the land and ocean on XCO2. ACTM_InvF simulation generally compares well with GOSAT observations in the period 2010–2014 and OCO-2 observations in the period 2015–2018. The ACTM_ES2LF simulation shows better agreement with GOSAT observation over the land compared with the ACTM_InvF simulation except over the tropics and northern extratropics (5°S to 40°N) (Fig. 7a). The ACTM_ES2LF simulation systematically underestimates SCAs by about 50% in the northern hemisphere (north of the Equator) compared with those observed by GOSAT over the ocean in all years. The ACTM_ES2LF and GOSAT XCO2 SCA agreement over land in the latitudes poleward of 45oN support the results for the CMIP5 model (MIROC-ESM) and aircraft measurements showed reasonably good agreement, at about 11 ppm and 14 ppm, respectively (Graven et al. 2013). The aircraft data (Graven et al. 2013) observe a combined effect of land and oceanic fluxes; thus, the separation of land and ocean flux signals using XCO2 SCA from a large amount of data provides us additional information.

Seasonal cycle amplitude of zonal mean XCO2, shown for land (top row) and ocean (bottom row) surfaces separately. The comparisons of XCO2 SCAs for both the ACTM_InvF and ACTM_ES2LF simulations are compared with GOSAT observations for the 2010–2014 period (left column), while the ACTM_InvF simulation only is compared with GOSAT and OCO-2 observations for the 2015–2018 period (right column). The error bars represent 1-σ standard deviations over 5 years in the left column and over 4 years in the right column. The ACTM_invF(GOSAT) and ACTM_invF(OCO-2) in panels c and d show the ACTM_InvF results when sampled at the location and time of GOSAT and OCO-2 measurements, respectively

While the ACTM_InvF simulation shows systematically lower SCAs than those observed by GOSAT by 1.5-2.0 ppm at all latitudes over the land, the systematic disagreements of ACTM_InvF SCAs with those of OCO-2 are smaller by half (Fig. 7c). These disagreements in SCAs over land are outside the range of the interannual variability in the southern hemisphere (Fig. 7c). The SCA differences over the ocean are more striking between GOSAT_v2.81 and the other 3 estimations in the southern hemisphere (Fig. 7d). This suggests a difference in the quality of XCO2 retrievals by the two satellites, especially over the ocean (i.e. glint observations on water bodies). It is not clear whether the post-retrieval bias correction (ref. O’Dell et al. 2018) is the only reason for the improved agreement between OCO-2 and ACTM_InvF.

To explain the weaker seasonal cycle correlations (Table 1) and smaller seasonal cycle amplitudes (Fig. 7a) simulated by ACTM_ES2LF in the tropical regions of Africa, America, and Asia, we compare two of the important terrestrial biosphere variables GPP and LAI from MIROC-ES2L with those from the FLUXCOM experiment and MODIS satellite (Fig. 8). In the tropics (10°S-10°N), comparisons of the two observed products (MODIS LAI and FLUXCOM GPP) show that the MODIS LAI exhibits less seasonality as the region consists of mostly evergreen forests, while FLUXCOM GPP shows distinct seasonality (Fig. 8a, c). The GPP is observed to be the highest in the late summer in both hemispheres. This suggests that GPP seasonality in this region is controlled strongly by abiotic processes, such as precipitation or soil water, radiation, and air temperature (Jung et al. 2017; Patra et al. 2005). MIROC-ES2L shows less seasonality in LAI, as in the case of MODIS LAI, but the simulated GPP shows much lesser agreement with the FLUXCOM GPP. This led us to conclude that the abiotic controls on CO2 exchange by the terrestrial ecosystem, as modelled in MIROC-ES2L, requires further attention; it is suspected that less soil water seasonality in tropics is associated with this problem, which needs further clarification through the evaluation of the model in terms of both biogeochemical and hydrological processes (Eyring et al. 2016; Hoffman et al. 2017).

At around 30°S, both MODIS LAI and FLUXCOM GPP show similar seasonality, suggesting LAI is the dominant controlling factor in the region. In MIROC-ES2L, the simulated LAI clearly shows weaker seasonality, leading to rather flat GPP throughout the year, suggesting problems in the biotic process model. In the northern midlatitudes (~ 40°N), it is clear that the growing season is longer in MIROC-ES2L than the observation-based products, i.e. too early leaf onset and too late leaf shedding. This suggests room for improving the phenology scheme in the model (Hajima et al. 2020). However, the problematic issues in the midlatitude regions are not tracked well in this study, and further sophistications in the atmospheric (XCO2) metric are required.

4 Conclusions

We have compared the simulated total column CO2 concentrations (XCO2) by JAMSTEC’s ACTM, using CO2 fluxes from an atmospheric CO2 inversion (ACTM_InvF) and an ESM (ACTM_ES2LF), with the XCO2 observed by GOSAT and OCO-2. Based on the analyses following major conclusions can be drawn.

(1)We show that the forward transport model simulation of CO2 fluxes from various methods can be tested well for all regions over the globe using the XCO2 measurements from the satellites, with conditions that the transport model realistically represents the inter-hemispheric exchange and age of air in the stratosphere (see also Schuh et al. 2019; Calle et al. 2019). Note that the atmospheric CO2 inversions lack in situ data coverage over much of the globe, and the ESMs are in their developmental phase for simulating the carbon cycle in a general circulation modelling framework.

(2)The inversion results using surface sites are consistent with the XCO2 measurements over different parts of the globe within 1 ppm (or more often within 0.5 ppm) (Table 1). Although this method of comparing MIROC-ES2L simulated fluxes with inversion and XCO2 observations is only valid for the simulation period where abundant in-situ or satellite measurements are available (e.g. 2009–2014 in this study), this can be a powerful constraint to test the contemporary CO2 flux simulated by ESMs. Hajima et al. (2020) suggested the MIROC-ES2L is likely to underestimate the contemporary CO2 concentration, and this study revealed that the contemporary CO2 fluxes by the ESM are comparable with the fluxes estimated by state-of-the-art inverse models with a sink bias of 0.25 PgC year−1.

(3)We also propose a metric to evaluate carbon cycle processes by using seasonal cycles of CO2—the inversion CO2 fluxes and satellite XCO2 suggested the ESM should be improved for seasonal amplitude and phasing of CO2 fluxes in different latitude bands. Using the observation-based leaf area index and gross primary productivity are compared with those simulated by the MIROC-ES2L, which suggest that the carbon-cycle processes in MIROC-ES2L need to be improved in the extratropical regions while it was suggested over the tropical regions the weather and soil water dynamics (and its ecological response) are inadequately simulated.

(4)A more sophisticated analysis is needed for removing the far-field effects on the XCO2 over individual regions for accurately judging how well (or badly) the ESM or inversion CO2 fluxes are modelled, as seen by the satellites. At the moment, it is not very clear whether the model–observation mismatches we find over the Southern Africa region (Fig. 6c) are caused by what fraction due to regional flux error or arising from the wrong flux seasonality in other continents in the same latitude range or propagated model data mismatches from the regions north or south of Southern Africa.

(5)More of these questions will be answered better as the quality of the retrievals continues to improve and longer time series of remote sensing observations are gathered, while the ESMs account for more complex processes occurring in the earth’s environment due to both anthropogenic and natural causes. As demonstrated in this study, the evaluation of CO2 fluxes over the globe will be a help to specify the region with large biases and to improve the model performance on reproducing CO2 concentration, both of which are essential to make more realistic future climate projections.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset(s) supporting the conclusions of this article is(are) available in JAMSTEC’s webdata server [https://ebcrpa.jamstec.go.jp/~prabir/data/Pubctn/XCO2model/].

The code of MIROC-ES2L and MIROC4-ACTM are not publicly archived because of the copyright policy of MIROC community. Readers are requested to contact the modelling group if they wish to validate the model configurations of MIROC-ES2L and MIROC4-ACTM.

Abbreviations

- ACTM:

-

Atmospheric chemistry transport model

- BRIC:

-

Brazil, Russia, India and China

- CASA:

-

Carnegie-Ames-Stanford Approach

- CO2 :

-

Carbon dioxide

- CMIP6:

-

Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6

- DGVM:

-

Dynamic global vegetation model

- ESM:

-

Earth system model

- ES2L:

-

Earth System Simulation version 2

- FFC:

-

Fossil-fuel and cement production

- FTS:

-

Fourier-transform spectrometer

- GHG:

-

Greenhouse gas

- GPP:

-

Gross primary productivity

- GCB:

-

Global carbon budget

- GOSAT:

-

Greenhouse Gases Observing Satellite

- JAMSTEC:

-

Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology

- JAXA:

-

Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency

- JMA:

-

Japan Meteorological Agency

- LAI:

-

Leaf-area index

- LUC:

-

Land-use change

- MIROC:

-

Model for Interdisciplinary Research on Climate

- MODIS:

-

Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer

- MoE:

-

Ministry of Environment; Japan

- NASA:

-

National Aeronautics and Space Administration

- NIES:

-

National Institute for Environmental Studies

- NOAA:

-

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

- OECD:

-

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- OCO-2:

-

Orbiting Carbon Observatory (series 2)

- OMIP:

-

Ocean Model Intercomparison Project

- SF6 :

-

Sulphur hexafluoride

- TCCON:

-

Total Carbon Column Observing Network

- UNFCCC:

-

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

References

Ainsworth EA, Rogers A (2007) The response of photosynthesis and stomatal conductance to rising [CO 2 ]: mechanisms and environmental interactions. Plant Cell Environ 30(3):258–270. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01641.x

Anav A, Friedlingstein P, Beer C, Ciais P, Harper A, Jones C, Murray-Tortarolo G, Papale D, Parazoo NC, Peylin P, Piao S, Sitch S, Viovy N, Wiltshire A, Zhao M (2015) Spatiotemporal patterns of terrestrial gross primary production: a review. Rev Geophys 53(3):785–818. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015RG000483

Andres RJ, Boden TA, Bréon F-M, Ciais P, Davis S, Erickson D, Gregg JS, Jacobson A, Marland G, Miller J, Oda T, Olivier JGJ, Raupach MR, Rayner P, Treanton K (2012) A synthesis of carbon dioxide emissions from fossil-fuel combustion. Biogeosciences 9(5):1845–1871. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-9-1845-2012

Arora V, Katavouta A, Williams RG, Jones C, Brovkin V, Friedlingstein P, Schwinger J, Bopp L, Boucher O, Cadule P, Chamberlain MA (2019) Carbon-concentration and carbon-climate feedbacks in CMIP6 models, and their comparison to CMIP5 models. Biogeosci Discuss. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-2019-473

Arora VK, Katavouta A, Williams RG, Jones CD, Brovkin V, Friedlingstein P, Schwinger J, Bopp L, Boucher O, Cadule P, Chamberlain MA, Christian JR, Delire C, Fisher RA, Hajima T, Ilyina T, Joetzjer E, Kawamiya M, Koven CD, Krasting JP, Law RM, Lawrence DM, Lenton A, Lindsay K, Pongratz J, Raddatz T, Séférian R, Tachiiri K, Tjiputra JF, Wiltshire A, Wu T, Ziehn T (2020) Carbon–concentration and carbon–climate feedbacks in CMIP6 models and their comparison to CMIP5 models. Biogeosciences 17(16):4173–4222. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-17-4173-2020

Bastos A, O’Sullivan M, Ciais P, Makowski D, Sitch S, Friedlingstein P, Chevallier F, Rödenbeck C, Pongratz J, Luijkx IT, Patra PK, Peylin P, Canadell JG, Lauerwald R, Li W, Smith NE, Peters W, Goll DS, Jain AK, Kato E, Lienert S, Lombardozzi DL, Haverd V, Nabel JEMS, Poulter B, Tian H, Walker AP, Zaehle S (2020) Sources of uncertainty in regional and global terrestrial CO2 exchange estimates. Glob Biogeochem Cycles 34(2). https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GB006393

Basu S, Baker DF, Chevallier F, Patra PK, Liu J, Miller JB (2018) The impact of transport model differences on CO 2 surface flux estimates from OCO-2 retrievals of column average CO 2. Atmos Chem Phys 18(10):7189–7215. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-18-7189-2018

Calle L, Poulter B, Patra PK (2019) A segmentation algorithm for characterizing rise and fall segments in seasonal cycles: an application to XCO2 to estimate benchmarks and assess model bias. Atmos Meas Tech 12(5):2611–2629. https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-12-2611-2019

Ciais P, Sabine C, Bala G, Bopp L, Brovkin V, Canadell JG, Chabra A, DeFries RS, Galloway J, Heimann M, Jones C, Le Quéré C, Myneni R, Piao S, Thornton P (2013) Carbon and other biogeochemical cycles. In: Climate change 2013: the physical science basis Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

Collier N, Hoffman FM, Lawrence DM, Keppel-Aleks G, Koven CD, Riley WJ, Mu M, Randerson JT (2018) The international land model benchmarking (ILAMB) system: design, theory, and implementation. J Adv Model Earth Syst 10(11):2731–2754. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018MS001354

Crisp D, Pollock HR, Rosenberg R, Chapsky L, Lee RAM, Oyafuso FA, Frankenberg C, O’Dell CW, Bruegge CJ, Doran GB, Eldering A, Fisher BM, Fu D, Gunson MR, Mandrake L, Osterman GB, Schwandner FM, Sun K, Taylor TE, Wennberg PO, Wunch D (2017) The on-orbit performance of the orbiting carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2) instrument and its radiometrically calibrated products. Atmos Meas Tech 10(1):59–81. https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-10-59-2017

DeVries T, Le Quéré C, Andrews O, Berthet S, Hauck J, Ilyina T, Landschützer P, Lenton A, Lima ID, Nowicki M, Schwinger J, Séférian R (2019) Decadal trends in the ocean carbon sink. Proc Natl Acad Sci 201900371:201900371. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1900371116

Dlugokencky EJ, Tans PP (2019) Trends in atmospheric carbon dioxide. In: Natl. Ocean. Atmos. Adm. Earth Syst. Res. Lab

Doughty R, Köhler P, Frankenberg C, Magney TS, Xiao X, Qin Y, Wu X, Moore B (2019) TROPOMI reveals dry-season increase of solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence in the Amazon forest. Proc Natl Acad Sci 116(44):22393–22398. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1908157116

Eldering A, O’Dell CW, Wennberg PO, Crisp D, Gunson MR, Viatte C, Avis C, Braverman A, Castano R, Chang A, Chapsky L, Cheng C, Connor B, Dang L, Doran G, Fisher B, Frankenberg C, Fu D, Granat R, Hobbs J, Lee RAM, Mandrake L, McDuffie J, Miller CE, Myers V, Natraj V, O’Brien D, Osterman GB, Oyafuso F, Payne VH, Pollock HR, Polonsky I, Roehl CM, Rosenberg R, Schwandner F, Smyth M, Tang V, Taylor TE, To C, Wunch D, Yoshimizu J (2017) The orbiting carbon Observatory-2: first 18 months of science data products. Atmos Meas Tech 10(2):549–563. https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-10-549-2017

Eyring V, Bony S, Meehl GA, Senior CA, Stevens B, Stouffer RJ, Taylor KE (2016) Overview of the coupled model Intercomparison project phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci Model Dev 9(5):1937–1958. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-9-1937-2016

Fleischer K, Rammig A, De Kauwe MG, Walker AP, Domingues TF, Fuchslueger L, Garcia S, Goll DS, Grandis A, Jiang M, Haverd V, Hofhansl F, Holm JA, Kruijt B, Leung F, Medlyn BE, Mercado LM, Norby RJ, Pak B, von Randow C, Quesada CA, Schaap KJ, Valverde-Barrantes OJ, Wang Y-P, Yang X, Zaehle S, Zhu Q, Lapola DM (2019) Amazon forest response to CO2 fertilization dependent on plant phosphorus acquisition. Nat Geosci 12(9):736–741. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-019-0404-9

Forkel M, Carvalhais N, Rodenbeck C, Keeling R, Heimann M, Thonicke K, Zaehle S, Reichstein M (2016) Enhanced seasonal CO2 exchange caused by amplified plant productivity in northern ecosystems. Science (80- ) 351:696–699. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac4971

Friedlingstein P, O’Sullivan M, Jones MW, Andrew RM, Hauck J, Olsen A, Peters GP, Peters W, Pongratz J, Sitch S, Le Quéré C, Canadell JG, Ciais P, Jackson RB, Alin S, Aragão LEOC, Arneth A, Arora V, Bates NR, Becker M, Benoit-Cattin A, Bittig HC, Bopp L, Bultan S, Chandra N, Chevallier F, Chini LP, Evans W, Florentie L, Forster PM, Gasser T, Gehlen M, Gilfillan D, Gkritzalis T, Gregor L, Gruber N, Harris I, Hartung K, Haverd V, Houghton RA, Ilyina T, Jain AK, Joetzjer E, Kadono K, Kato E, Kitidis V, Korsbakken JI, Landschützer P, Lefèvre N, Lenton A, Lienert S, Liu Z, Lombardozzi D, Marland G, Metzl N, Munro DR, Nabel JEMS, Nakaoka S-I, Niwa Y, O’Brien K, Ono T, Palmer PI, Pierrot D, Poulter B, Resplandy L, Robertson E, Rödenbeck C, Schwinger J, Séférian R, Skjelvan I, Smith AJP, Sutton AJ, Tanhua T, Tans PP, Tian H, Tilbrook B, van der Werf G, Vuichard N, Walker AP, Wanninkhof R, Watson AJ, Willis D, Wiltshire AJ, Yuan W, Yue X, Zaehle S (2020) Global carbon budget 2020. Earth Syst Sci Data 12(4):3269–3340. https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-12-3269-2020

Gier BK, Buchwitz M, Reuter M, Cox PM, Friedlingstein P, Eyring V (2020) Spatially resolved evaluation of earth system models with satellite column-averaged CO 2. Biogeosciences 17(23):6115–6144. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-17-6115-2020

Gloor M, Gatti L, Brienen R, Feldpausch TR, Phillips OL, Miller J, Ometto JP, Rocha H, Baker T, de Jong B, Houghton RA, Malhi Y, Aragão LEOC, Guyot J-L, Zhao K, Jackson R, Peylin P, Sitch S, Poulter B, Lomas M, Zaehle S, Huntingford C, Levy P, Lloyd J (2012) The carbon balance of South America: a review of the status, decadal trends and main determinants. Biogeosciences 9(12):5407–5430. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-9-5407-2012

Graven HD, Keeling RF, Piper SC, Patra PK, Stephens BB, Wofsy SC, Welp LR, Sweeney C, Tans PP, Kelley JJ, Daube BC, Kort EA, Santoni GW, Bent JD (2013) Enhanced seasonal exchange of CO2 by northern ecosystems since 1960. Science (80- ) 341:1085–1089. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1239207

Hajima T, Watanabe M, Yamamoto A, Tatebe H et al (2020) Description of the MIROC-ES2L earth system model and evaluation of its climate–biogeochemical processes and feedbacksGeosci Model Dev Discuss. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-2019-275

Hamazaki T, Kuze A, Kondo K (2004) In: Strojnik M (ed) Sensor system for greenhouse gas observing satellite (GOSAT), p 275

Hansis E, Davis SJ, Pongratz J (2015) Relevance of methodological choices for accounting of land use change carbon fluxes. Glob Biogeochem Cycles 29(8):1230–1246. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GB004997

Haverd V, Raupach MR, Briggs PR, Davis SJ, Law RM, Meyer CP, Peters GP, Pickett-Heaps C, Sherman B (2013) The Australian terrestrial carbon budget. Biogeosciences 10(2):851–869. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-10-851-2013

Hoffman FM, Koven CD, Keppel-Aleks G, Lawrence DM, Riley WJ, Randerson JT, Ahlström A, Abramowitz G, Baldocchi DD, Best MJ, Bond-Lamberty B, De Kauwe MG, Denning AS, Desai AR, Eyring V, Fisher JB, Fisher RA, Gleckler PJ, Huang M, Hugelius G, Jain AK, Kiang NY, Kim H, Koster RD, Kumar SV, Li H, Luo Y, Mao J, NG MD, Mishra U, Moorcroft PR, GSH P, Ricciuto DM, Schaefer K, Schwalm CR, Serbin SP, Shevliakova E, Slater AG, Tang J, Williams M, Xia J, Xu C, Joseph R, Koch D (2017) 2016 international land model benchmarking (ILAMB) workshop report

Houghton RA, Nassikas AA (2017) Global and regional fluxes of carbon from land use and land cover change 1850-2015. Glob Biogeochem Cycles 31(3):456–472. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GB005546

Ichii K, Ueyama M, Kondo M, Saigusa N, Kim J, Alberto MC, Ardö J, Euskirchen ES, Kang M, Hirano T, Joiner J, Kobayashi H, Marchesini LB, Merbold L, Miyata A, Saitoh TM, Takagi K, Varlagin A, Bret-Harte MS, Kitamura K, Kosugi Y, Kotani A, Kumar K, Li S-G, Machimura T, Matsuura Y, Mizoguchi Y, Ohta T, Mukherjee S, Yanagi Y, Yasuda Y, Zhang Y, Zhao F (2017) New data-driven estimation of terrestrial CO 2 fluxes in Asia using a standardized database of eddy covariance measurements, remote sensing data, and support vector regression. J Geophys Res Biogeosci 122(4):767–795. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JG003640

Ito A, Oikawa T (2002) A simulation model of the carbon cycle in land ecosystems (Sim-CYCLE): a description based on dry-matter production theory and plot-scale validation. Ecol Model 151(2-3):143–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3800(01)00473-2

Janssens-Maenhout G, Petrescu R, Crippa M, Peters J, Dentener F, van Aardenne J, Muntean M, Guizzardi D, Solazzo E, Bergamaschi P, Olivier J, Pagliari V, Oreggioni G, Doering U, Monni S, Schaaf E (2019) EDGAR v4.3.2 global atlas of the three major greenhouse gas emissions for the period 1970–2012. Earth Syst Sci Data Discuss 2010:1–52. https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-2018-164

Jones CD, Arora V, Friedlingstein P, Bopp L, Brovkin V, Dunne J, Graven H, Hoffman F, Ilyina T, John JG, Jung M, Kawamiya M, Koven C, Pongratz J, Raddatz T, Randerson JT, Zaehle S (2016) C4MIP – the coupled climate–carbon cycle model Intercomparison project: experimental protocol for CMIP6. Geosci Model Dev 9(8):2853–2880. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-9-2853-2016

Jones CD, Frölicher TL, Koven C, MacDougall AH, Matthews HD, Zickfeld K, Rogelj J, Tokarska KB, Gillett NP, Ilyina T, Meinshausen M, Mengis N, Séférian R, Eby M, Burger FA (2019) The zero emissions commitment model Intercomparison project (ZECMIP) contribution to C4MIP: quantifying committed climate changes following zero carbon emissions. Geosci Model Dev 12(10):4375–4385. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-12-4375-2019

Jones S, Rowland L, Cox P, Hemming D, Wiltshire A, Williams K, Parazoo NC, Liu J, da Costa ACL, Meir P, Mencuccini M, Harper AB (2020) The impact of a simple representation of non-structural carbohydrates on the simulated response of tropical forests to drought. Biogeosciences 17(13):3589–3612. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-17-3589-2020

Jung M, Reichstein M, Schwalm CR, Huntingford C, Sitch S, Ahlström A, Arneth A, Camps-Valls G, Ciais P, Friedlingstein P, Gans F, Ichii K, Jain AK, Kato E, Papale D, Poulter B, Raduly B, Rödenbeck C, Tramontana G, Viovy N, Wang Y-P, Weber U, Zaehle S, Zeng N (2017) Compensatory water effects link yearly global land CO2 sink changes to temperature. Nature 541(7638):516–520. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature20780

Jung M, Schwalm C, Migliavacca M, Walther S, Camps-Valls G, Koirala S, Anthoni P, Besnard S, Bodesheim P, Carvalhais N, Chevallier F, Gans F, Goll DS, Haverd V, Köhler P, Ichii K, Jain AK, Liu J, Lombardozzi D, Nabel JEMS, Nelson JA, O’Sullivan M, Pallandt M, Papale D, Peters W, Pongratz J, Rödenbeck C, Sitch S, Tramontana G, Walker A, Weber U, Reichstein M (2020) Scaling carbon fluxes from eddy covariance sites to globe: synthesis and evaluation of the FLUXCOM approach. Biogeosciences 17(5):1343–1365. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-17-1343-2020

Keeling RF, Graven HD, Welp LR, Resplandy L, Bi J, Piper SC, Sun Y, Bollenbacher A, Meijer HAJ (2017) Atmospheric evidence for a global secular increase in carbon isotopic discrimination of land photosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 114(39):10361–10366. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1619240114

Keenan TF, Hollinger DY, Bohrer G, Dragoni D, Munger JW, Schmid HP, Richardson AD (2013) Increase in forest water-use efficiency as atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations rise. Nature 499(7458):324–327. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12291

Kobayashi S, Ota Y, Harada Y, Ebita A, Moriya M, Onoda H, Onogi K, Kamahori H, Kobayashi C, Endo H, Miyaoka K, Takahashi K (2015) The JRA-55 reanalysis: general specifications and basic characteristics. J Meteorol Soc Japan Ser II 93(1):5–48. https://doi.org/10.2151/jmsj.2015-001

Kondo M, Patra PK, Sitch S, Friedlingstein P, Poulter B, Chevallier F, Ciais P, Canadell JG, Bastos A, Lauerwald R, Calle L, Ichii K, Anthoni P, Arneth A, Haverd V, Jain AK, Kato E, Kautz M, Law RM, Lienert S, Lombardozzi D, Maki T, Nakamura T, Peylin P, Rödenbeck C, Zhuravlev R, Saeki T, Tian H, Zhu D, Ziehn T (2020) State of the science in reconciling top-down and bottom-up approaches for terrestrial CO 2 budget. Glob Chang Biol 26(3):1068–1084. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14917

Kulawik SS, Crowell S, Baker DF, Liu J, McKain K (2020) Characterization of OCO-2 and ACOS-GOSAT biases and errors for CO2 flux estimatesAtmos Meas Tech. https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-2019-257

Kuze A, Suto H, Shiomi K, Kawakami S, Tanaka M, Ueda Y, Deguchi A, Yoshida J, Yamamoto Y, Kataoka F, Taylor TE, Buijs HL (2016) Update on GOSAT TANSO-FTS performance, operations, and data products after more than 6 years in space. Atmos Meas Tech 9(6):2445–2461. https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-9-2445-2016

Le Quéré C, Andrew RM, Friedlingstein P, Sitch S, Hauck J, Pongratz J, Pickers PA, Korsbakken JI, Peters GP, Canadell JG, Arneth A, Arora VK, Barbero L, Bastos A, Bopp L, Chevallier F, Chini LP, Ciais P, Doney SC, Gkritzalis T, Goll DS, Harris I, Haverd V, Hoffman FM, Hoppema M, Houghton RA, Hurtt G, Ilyina T, Jain AK, Johannessen T, Jones CD, Kato E, Keeling RF, Goldewijk KK, Landschützer P, Lefèvre N, Lienert S, Liu Z, Lombardozzi D, Metzl N, Munro DR, Nabel JEMS, Nakaoka S, Neill C, Olsen A, Ono T, Patra P, Peregon A, Peters W, Peylin P, Pfeil B, Pierrot D, Poulter B, Rehder G, Resplandy L, Robertson E, Rocher M, Rödenbeck C, Schuster U, Schwinger J, Séférian R, Skjelvan I, Steinhoff T, Sutton A, Tans PP, Tian H, Tilbrook B, Tubiello FN, van der Laan-Luijkx IT, van der Werf GR, Viovy N, Walker AP, Wiltshire AJ, Wright R, Zaehle S, Zheng B (2018) Global carbon budget 2018. Earth Syst Sci Data 10(4):2141–2194. https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-10-2141-2018

McKinley GA, Fay AR, Eddebbar YA, Gloege L, Lovenduski NS (2020) External forcing explains recent decadal variability of the ocean carbon sink. AGU Adv 1(2). https://doi.org/10.1029/2019AV000149

Monsi M, Saeki T (1953) Über den Lichtfaktor in den Pflanzengesellschaften und seine Bedeutung für die Stoffproduktion. Japanese J Bot 14:22–52

Myhre G, Shindell DT, Bréon F-M, Collins W, Fuglestvedt JS, Huang J, Koch D, Lamarque J-FJ-F, Lee D, Mendoza B, Nakajima T, Robock A, Stephens GL, Takemura T, Zhang H (2013) Anthropogenic and natural radiative forcing, in: climate change 2013: the physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge and New York

O’Dell CW, Eldering A, Wennberg PO, Crisp D, Gunson MR, Fisher B, Frankenberg C, Kiel M, Lindqvist H, Mandrake L, Merrelli A, Natraj V, Nelson RR, Osterman GB, Payne VH, Taylor TE, Wunch D, Drouin BJ, Oyafuso F, Chang A, McDuffie J, Smyth M, Baker DF, Basu S, Chevallier F, Crowell SMR, Feng L, Palmer PI, Dubey M, García OE, Griffith DWT, Hase F, Iraci LT, Kivi R, Morino I, Notholt J, Ohyama H, Petri C, Roehl CM, Sha MK, Strong K, Sussmann R, Te Y, Uchino O, Velazco VA (2018) Improved retrievals of carbon dioxide from orbiting carbon Observatory-2 with the version 8 ACOS algorithm. Atmos Meas Tech 11(12):6539–6576. https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-11-6539-2018

Orr JC, Najjar RG, Aumont O, Bopp L, Bullister JL, Danabasoglu G, Doney SC, Dunne JP, Dutay J-C, Graven H, Griffies SM, John JG, Joos F, Levin I, Lindsay K, Matear RJ, McKinley GA, Mouchet A, Oschlies A, Romanou A, Schlitzer R, Tagliabue A, Tanhua T, Yool A (2017) Biogeochemical protocols and diagnostics for the CMIP6 ocean model Intercomparison project (OMIP). Geosci Model Dev 10(6):2169–2199. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-10-2169-2017

Patra P, Crisp D, Kaiser J, Wunch D, Saeki T, Ichii K, Sekiya T, Wennberg PO, Feist DG, Pollard DF, Griffith DWT, Velazco VA, De Maziere M, Sha MK, Roehl C, Chatterjee A, Ishijima K (2017) The orbiting carbon observatory (OCO-2) tracks 2–3 peta-gram increase in carbon release to the atmosphere during the 2014–2016 El Niño. Sci Rep 7(1):13567. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-13459-0

Patra PK, Canadell JG, Houghton RA, Piao SL, Oh N-H, Ciais P, Manjunath KR, Chhabra A, Wang T, Bhattacharya T, Bousquet P, Hartman J, Ito A, Mayorga E, Niwa Y, Raymond PA, Sarma VVSS, Lasco R (2013) The carbon budget of South Asia. Biogeosciences 10(1):513–527. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-10-513-2013

Patra PK, Ishizawa M, Maksyutov S, Nakazawa T, Inoue G (2005) Role of biomass burning and climate anomalies for land-atmosphere carbon fluxes based on inverse modeling of atmospheric CO 2. Global Biogeochem cycles 19. https://doi.org/10.1029/2004GB002258

Patra PK, Takigawa M, Watanabe S, Chandra N, Ishijima K, Yamashita Y (2018) Improved chemical tracer simulation by MIROC4.0-based atmospheric chemistry-transport model (MIROC4-ACTM). SOLA 14(0):91–96. https://doi.org/10.2151/sola.2018-016

Randerson JT, Thompson MV, Conway TJ, Fung IY, Field CB (1997) The contribution of terrestrial sources and sinks to trends in the seasonal cycle of atmospheric carbon dioxide. Glob Biogeochem Cycles 11(4):535–560. https://doi.org/10.1029/97GB02268

Remaud M, Chevallier F, Cozic A, Lin X, Bousquet P (2018) On the impact of recent developments of the LMDz atmospheric general circulation model on the simulation of CO<sub>2</sub> transport. Geosci Model Dev 11(11):4489–4513. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-11-4489-2018

Resplandy L, Keeling RF, Rödenbeck C, Stephens BB, Khatiwala S, Rodgers KB, Long MC, Bopp L, Tans PP (2018) Revision of global carbon fluxes based on a reassessment of oceanic and riverine carbon transport. Nat Geosci 11(7):504–509. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-018-0151-3

Rodgers CD, Connor BJ (2003) Intercomparison of remote sounding instruments. J Geophys Res Atmos 108n/a-n/a. https://doi.org/10.1029/2002JD002299

Saeki T, Patra PK (2017) Implications of overestimated anthropogenic CO2 emissions on east Asian and global land CO2 flux inversion. Geosci Lett 4(1):9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40562-017-0074-7

Schuh AE, Jacobson AR, Basu S, Weir B, Baker D, Bowman K, Chevallier F, Crowell S, Davis KJ, Deng F, Denning S, Feng L, Jones D, Liu J, Palmer PI (2019) Quantifying the impact of atmospheric transport uncertainty on CO2 surface flux estimates. Glob Biogeochem Cycles 33(4):484–500. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GB006086

Sitch S, Friedlingstein P, Gruber N, Jones SD, Murray-Tortarolo G, Ahlström A, Doney SC, Graven H, Heinze C, Huntingford C, Levis S, Levy PE, Lomas M, Poulter B, Viovy N, Zaehle S, Zeng N, Arneth A, Bonan G, Bopp L, Canadell JG, Chevallier F, Ciais P, Ellis R, Gloor M, Peylin P, Piao SL, Le Quéré C, Smith B, Zhu Z, Myneni R (2015) Recent trends and drivers of regional sources and sinks of carbon dioxide. Biogeosciences 12(3):653–679. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-12-653-2015

Takahashi T, Sutherland SC, Wanninkhof R, Sweeney C, Feely RA, Chipman DW, Hales B, Friederich G, Chavez F, Sabine C, Watson A, Bakker DCE, Schuster U, Metzl N, Yoshikawa-Inoue H, Ishii M, Midorikawa T, Nojiri Y, Körtzinger A, Steinhoff T, Hoppema M, Olafsson J, Arnarson TS, Tilbrook B, Johannessen T, Olsen A, Bellerby R, Wong CS, Delille B, Bates NR, de Baar HJW (2009) Climatological mean and decadal change in surface ocean pCO2, and net sea–air CO2 flux over the global oceans. Deep Sea Res Part II Top Stud Oceanogr 56(8-10):554–577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2008.12.009

Tans PP, Keeling RF (2019) Trends in atmospheric carbon dioxide NOAA/ESRL Scripps Inst Oceanogr

Thoning KW, Tans PP, Komhyr WD (1989) Atmospheric carbon dioxide at Mauna Loa observatory: 2. Analysis of the NOAA GMCC data, 1974-1985. J Geophys Res Atmos 94(D6):8549–8565. https://doi.org/10.1029/JD094iD06p08549

Tramontana G, Jung M, Schwalm CR, Ichii K, Camps-Valls G, Ráduly B, Reichstein M, Arain MA, Cescatti A, Kiely G, Merbold L, Serrano-Ortiz P, Sickert S, Wolf S, Papale D (2016) Predicting carbon dioxide and energy fluxes across global FLUXNET sites with regression algorithms. Biogeosciences 13(14):4291–4313. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-13-4291-2016

Tsuboi K, Matsueda H, Sawa Y, Niwa Y, Nakamura M, Kuboike D, Saito K, Ohmori H, Iwatsubo S, Nishi H, Hanamiya Y, Tsuji K, Baba Y (2013) Evaluation of a new JMA aircraft flask sampling system and laboratory trace gas analysis system. Atmos Meas Tech 6(5):1257–1270. https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-6-1257-2013

Wang J, Feng L, Palmer PI, Liu Y, Fang S, Bösch H, O’Dell CW, Tang X, Yang D, Liu L, Xia C (2020) Large Chinese land carbon sink estimated from atmospheric carbon dioxide data. Nature 586(7831):720–723. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2849-9

Watanabe S, Hajima T, Sudo K, Nagashima T, Takemura T, Okajima H, Nozawa T, Kawase H, Abe M, Yokohata T, Ise T, Sato H, Kato E, Takata K, Emori S, Kawamiya M (2011) MIROC-ESM 2010: model description and basic results of CMIP5-20c3m experiments. Geosci Model Dev 4(4):845–872. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-4-845-2011

Wenzel S, Cox PM, Eyring V, Friedlingstein P (2016) Projected land photosynthesis constrained by changes in the seasonal cycle of atmospheric CO2. Nature 538(7626):499–501. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature19772

Wu J, Albert LP, Lopes AP, Restrepo-Coupe N, Hayek M, Wiedemann KT, Guan K, Stark SC, Christoffersen B, Prohaska N, Tavares JV, Marostica S, Kobayashi H, Ferreira ML, Campos KS, da Silva R, Brando PM, Dye DG, Huxman TE, Huete AR, Nelson BW, Saleska SR (2016) Leaf development and demography explain photosynthetic seasonality in Amazon evergreen forests. Science (80- ) 351:972–976. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad5068

Wunch D, Wennberg PO, Osterman G, Fisher B, Naylor B, Roehl CM, O’Dell C, Mandrake L, Viatte C, Kiel M, Griffith DWT, Deutscher NM, Velazco VA, Notholt J, Warneke T, Petri C, De Maziere M, Sha MK, Sussmann R, Rettinger M, Pollard D, Robinson J, Morino I, Uchino O, Hase F, Blumenstock T, Feist DG, Arnold SG, Strong K, Mendonca J, Kivi R, Heikkinen P, Iraci L, Podolske J, Hillyard PW, Kawakami S, Dubey MK, Parker HA, Sepulveda E, García OE, Te Y, Jeseck P, Gunson MR, Crisp D, Eldering A (2017) Comparisons of the orbiting carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2) X CO 2 measurements with TCCON. Atmos Meas Tech 10(6):2209–2238. https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-10-2209-2017

Yan K, Park T, Yan G, Chen C, Yang B, Liu Z, Nemani R, Knyazikhin Y, Myneni R (2016) Evaluation of MODIS LAI/FPAR product collection 6. Part 1: consistency and improvements. Remote Sens 8:359. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs8050359

Yokota T, Yoshida Y, Eguchi N, Ota Y, Tanaka T, Watanabe H, Maksyutov S (2009) Global concentrations of CO2 and CH4 retrieved from GOSAT: first preliminary results. SOLA 5:160–163. https://doi.org/10.2151/sola.2009-041

Yoshida Y, Kikuchi N, Morino I, Uchino O, Oshchepkov S, Bril A, Saeki T, Schutgens N, Toon GC, Wunch D, Roehl CM, Wennberg PO, Griffith DWT, Deutscher NM, Warneke T, Notholt J, Robinson J, Sherlock V, Connor B, Rettinger M, Sussmann R, Ahonen P, Heikkinen P, Kyrö E, Mendonca J, Strong K, Hase F, Dohe S, Yokota T (2013) Improvement of the retrieval algorithm for GOSAT SWIR XCO 2 and XCH 4 and their validation using TCCON data. Atmos Meas Tech 6(6):1533–1547. https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-6-1533-2013

Zaehle S, Friend AD, Friedlingstein P, Dentener F, Peylin P, Schulz M (2010) Carbon and nitrogen cycle dynamics in the O-CN land surface model: 2. Role of the nitrogen cycle in the historical terrestrial carbon balance. Glob Biogeochem Cycles 24n/a-n/a. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009GB003522

Zeng N, Zhao F, Collatz GJ, Kalnay E, Salawitch RJ, West TO, Guanter L (2014) Agricultural green revolution as a driver of increasing atmospheric CO2 seasonal amplitude. Nature 515(7527):394–397. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13893

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by TOUGOU/SOUSEI, the Integrated Research Program for Advancing Climate Models (grant number JPMXD0717935715)/Program for Risk Information on Climate Change, through the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan. We thank Masayuki Takigawa and Shingo Watanabe, JAMSTEC for helping with the MIROC4-ACTM development. This work was first presented at the Earth Information Day, an event organised by the The Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA) at the 25th Conference of the Parties (COP-25) Madrid, Spain (https://unfccc.int/topics/science/events-meetings/systematic-observation/earth-information-day-2019). This article was first submitted to the SPEPS/Article Collection “Projection and impact assessment of global change” (05 Feb 2020). We thank Dr. Marine Remaud and two anonymous reviewers for valuable comments in the review process.

Funding

This work was supported by TOUGOU/SOUSEI, the “Integrated Research Program for Advancing Climate Models”/“Program for Risk Information on Climate Change”, by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (grant number JPMXD0717935715). The Earth Simulator and JAMSTEC Super Computing System were used for the simulations, and the administration staff provided much supports.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PKP and MKa proposed the research topic and conceived the analysis. TH, AI, NC, KI conducted the model simulations. RS, NC and PKP performed data analysis. TH, MKa, MKo, KI, DC joined the discussions. All authors contributed in preparation of the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1:

Same as Fig. 5 but for data over land surface only. Figure S2: Same as Fig. 5, but for the observations over water bodies only. Animation S1: Same as Fig. 6 for the time series of XCO2 for all the 15 land regions and 11 ocean regions for the period of 2009-2018. Note that these plots consist of 2 additional panels showing the model-measurement differences and the detrended seasonal cycles, for which the statistics are presented in Table 1. (https://ebcrpa.jamstec.go.jp/~prabir/data/Pubctn/XCO2model/Animation_S1.gif). Animation S2: Same as Animation S1, but for the OCO-2 measurement period (2014-2018). (https://ebcrpa.jamstec.go.jp/~prabir/data/Pubctn/XCO2model/Animation_S2.gif). Animation S3: Same as Fig. 7 for XCO2 seasonal cycle amplitudes for different years, and those for ACTM_InvF and OCO-2 only for the period 2014 to 2018. (https://ebcrpa.jamstec.go.jp/~prabir/data/Pubctn/XCO2model/Animation_S3.gif). Animations are also available at: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14343383.v1.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Patra, P.K., Hajima, T., Saito, R. et al. Evaluation of earth system model and atmospheric inversion using total column CO2 observations from GOSAT and OCO-2. Prog Earth Planet Sci 8, 25 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40645-021-00420-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40645-021-00420-z