Abstract

Within the rich literature on volunteering, the topic of volunteer–user interaction and the mechanisms causing or mitigating inequality in this interaction remain understudied. Moreover, knowledge on how digitalization affects voluntary interaction is scarce. Based on a qualitative study of a Danish organization that offers virtual voluntary tutoring, this paper shows how technological and formal aspects of the organizational context may mitigate the risk of volunteers engaging in paternalistic, intimacy-seeking behaviour. First, reliance on information and communications technology (ICT) and managerial logics sustains a bounded form of interaction in which solving a problem is the focal point, while access to personal background information is limited. Second, the organizational design suspends sociability as a criterion for differential treatment of users. Third, anonymous mediated interaction enables temporal and audio–visual asymmetry, allowing users to perform ‘digitally sustained impression management’.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Voluntary social work, defined as unremunerated efforts by volunteers in response to a social problem or need, has become a prominent ingredient in the ‘new welfare mix’ (Hustinx, 2010) across welfare states. Central to the political and public appraisal of voluntary social work are the democratic, innovative, and interpersonal qualities routinely associated with the interaction between volunteers and beneficiaries (Eliasoph, 2011; Evers & von Essen, 2019). Whereas volunteering en bloc is said to generate societal cohesion and generalized trust (Putnam, 2000), interaction between volunteers and beneficiaries is expected to represent an egalitarian and authentic form of sociality, free of bureaucratic regulation and paternalistic authority (Eliasoph, 2009; la Cour, 2019; Villadsen, 2008). Given the multiple political and public hopes centred on the interaction between beneficiaries and volunteers, research into this form of sociality is surprisingly scarce.

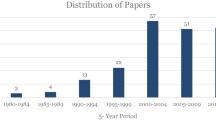

Compared to the rich literature on volunteering in general (Ma & Konrath, 2018) and the wealth of publications theorizing and documenting inequality in regard to access to volunteering (Ma & Konrath, 2018; Wilson & Musick, 1997), the topic of inequality between volunteers and beneficiaries has been neglected. Moreover, existing research provides limited empirical support for the popular belief that such interaction should be particularly egalitarian. On the contrary, scholars find that ‘philanthropic paternalism’ (Salamon & Anheier, 1998) is common in voluntary social work, as the helping often takes place according to the volunteers’ schedules, moral aspirations, and pursuit of authentic and intimate relations with beneficiaries (Carlsen, Doerr, and Toubøl 2020, Conran, 2011; Eliasoph, 2011; Villadsen, 2008). These studies, however, represent a tiny area in the vast landscape of third sector research (Ma & Konrath, 2018), leaving underexplored the topic of how intra-organizational and interpersonal dynamics enable or mitigate inequality. Related to this knowledge gap, the question of how digitalization impacts voluntary interaction remains understudied. With notable exceptions (presented below), scholars occupied with voluntary work and interaction have concentrated on face-to-face sociality (Conran, 2011; Eliasoph, 2011; la Cour, 2019; Quinn & Tomczak, 2021; Villadsen, 2008). While the digitalization of organizations in the private and public sectors has been subject to vigorous academic discussion (Plesner & Husted, 2020), questions such as how digitalization affects voluntary organizing and inequality in volunteering remain underexplored.

Focusing on an organization in Denmark that provides virtual voluntary tutoring, this paper contributes knowledge on intra-organizational dynamics of inequality in digitalized voluntary interaction by investigating the following question:

How is inequality between volunteers and users sustained or mitigated by the formal and techno-material aspects of the organizational context?

Based on 18 months of fieldwork, in-depth interviews, and focus groups with volunteers and staff members, this paper shows how organizational reliance on information and communications technology (ICT) in interplay with a pronounced orientation towards managerial logics mitigates the risk of inequality in interaction between volunteers and beneficiaries.

After briefly reviewing the existing literature on inequality in face-to-face and digital interaction between volunteers and beneficiaries, the theoretical framework is presented. Then, the details of the case study and methods are described, after which the analysis is laid out in three parts. The paper concludes by summarizing the findings and discussing their academic and practical implications.

The Pursuit of Intimacy and the Production of Inequality in Voluntary Social Work

As la Cour remarks, the ‘myth of authenticity’ (2019) that envisions voluntary social work as the antithesis to paternalistic and bureaucratic professional social work has captivated the minds of many politicians, managers, and volunteers. Across geographical contexts and fields of voluntary work targeting at-risk populations, scholars observe how building authentic, intimate relationships with beneficiaries constitutes a key motivational factor for volunteers. In the US context, Eliasoph documented how volunteers at homework cafés were motivated by the opportunity to ‘become intimate quickly’ with at-risk users and gain an ‘inspiring, emotionally and morally transformative and fulfilling experience’ (2011, p. 117). Among volunteer tourists in the Global South, Conran observed how volunteers especially valued the ‘intimate embodied experiences’ in which they ‘got to know the native population as they really were’ (2011, p. 1460). Moreover, volunteer managers across different countries encourage the pursuit of intimate relationships with beneficiaries and instruct volunteers to act like ‘beloved aunties’ (Eliasoph, 2011, p. 11), develop a ‘family-like intimacy’ (Eliasoph, 2009, p. 301), or become like ‘an uncle’ (la Cour, 2019, p. 7). Coordinators of volunteer tourists recognize that the experience of ‘feeling their heartbeat’ is important to volunteers (Conran, 2011, p. 1461), and managers of shelters for the homeless perceive ‘close and trustful relationships’ between volunteers and users as being key to successful rehabilitation (Villadsen, 2008, p. 183).

Regarding the important matter of inequality in volunteering, another transversal finding is, however, that the pursuit of interpersonal intimacy has a dark side. At the homework cafés, Eliasoph noted how the episodic engagement of ‘plug-in volunteers’, combined with the desire of these volunteers to build ‘morally transformative’ relationships with beneficiaries, had a ‘disastrous effect’ (2011, p. 118). When the task of helping became too difficult due to the volunteers’ busy schedules, they would initiate conversations about the private lives of the young beneficiaries. However, such intimate conversations proved to be awkward, as the privileged volunteers had difficulty relating to the beneficiaries’ life worlds. Instead of getting help, users shared personal background information with a volunteer who typically left within a few months. In their quest for intimate, egalitarian, and authentic sociality, volunteers thus inadvertently end up reproducing the structural dynamics of inequality, as the interaction takes place mainly on their terms and according to their schedules and aspirations for morally transformative experiences. Similarly, Conran concluded that ‘the overwhelming focus on intimacy in volunteer tourism overshadows the structural inequality that volunteer tourism seeks to address’ (2011, p. 1467). Such findings corroborate the general concern regarding ‘philanthropic paternalism’ (Salamon & Anheier, 1998), which denotes the phenomenon in which resourceful volunteers engage in helping on terms that they define. However, as recent studies on interpersonal inequality in volunteering have focused on face-to-face interaction, it remains unclear whether virtual volunteering involves a similar risk of paternalistic intimacy-seeking.

To be sure, ICT has long been on the radar of third sector scholars, and studies abound on how many-to-many communication enables new ways of connecting, mobilizing, recruiting, and managing civically engaged people (Amichai-Hamburger, 2008; Bennett & Segerberg, 2012; Bernholz, 2017; Brainard & Brinkerhoff, 2004; Eimhjellen, 2019; Piatak et al. 2019). The phenomenon of virtual volunteering, however, is more recent (Ihm, 2017), and while the COVID-19 pandemic triggered a host of virtual volunteering initiatives (Carlsen, Toubøl, and Brincker 2020), the field of online volunteer research remains in its infancy (Eimhjellen, 2019). At present, the literature is dominated by descriptive and exploratory studies that demarcate and map the field (Ackermann and Manatschal 2018; Mukherjee, 2011), supply advice to managers of virtual volunteers (Cravens, 2000; Dhebar & Stokes, 2008), or map the motivations and characteristics of volunteers (Eimhjellen, 2019). Consequently, questions such as how ICT impacts intra-organizational sensemaking and inequality in voluntary interaction demand further examination (Carlsen, Doerr, and Toubøl 2020). To this end, organization scholars caution against the fallacy of technological determinism (Plesner & Husted, 2020), by which digital technologies, impervious to the context in which they are deployed, are expected to produce certain outcomes. Thus, while the digitalization of work in the public and private sectors has been observed to sustain the supervision, effectivization, and evaluation of work (Orlikowski & Scott, 2016; Plesner & Husted, 2020), the ramifications of ICT on voluntary interaction deserve to be explored with an approach that takes account of organizational contingency. The theoretical framework presented next is designed to grasp digital voluntary interaction in interdependency with the organizational and institutional context.

Theorizing Digital Interaction in Context

Regarding the act of volunteering, Hustinx et al. remarked how ‘it is imperative to situate these micro-level attributes in the broader social, structural and cultural context of volunteering’ (2010, p. 75). The importance of a multi-level approach that appreciates interpersonal interaction as embedded in organizational and institutional structures is transferable to research on virtual voluntary interaction. As scholars in this field argue, the implementation and everyday use of ICT depends in part on the organizational culture and orientation (Eimhjellen, 2014), the ‘embodied presence’ and material settings of those involved (Gotved, 2006; Knorr-Cetina & Bruegger, 2002, p. 923), and the temporal structures that connect interactants (Hernes & Schultz, 2020; Knorr-Cetina & Bruegger, 2002).

To explore inequality in relation to volunteer–user interaction and understand how the integration of ICT is interdependent with trends in the organizational and institutional environment, the analytic framework includes an interactionist development of the institutional logics perspective (ILP). The ILP, as developed by Friedland and Alford (1991), suggests that organizations respond to dominant logics in their institutional environment by integrating certain goals and considering certain managerial techniques and interactional norms as legitimate. Building on this insight, Hallett and Ventresca (2006) argue that the external orientation is modified internally, as the institutional logics are subject to intra-organizational interaction and sensemaking among organizational inhabitants. Accordingly, the following analysis perceives of volunteer–user interaction as embedded in an organizational context, which, in turn, is responsive to an institutional environment that promotes certain modes of organizing.

Regarding the matter of how the technological and material aspects (techno-material aspects below) of the organizational context affect interaction, the ILP remains a valuable yet insufficiently explored framework. In their foundational text, Friedland and Alford do point to a dialectic interplay between the ideational and material aspects of institutional logics (1991, p. 248). However, as Jones et al. (2013) conclude in a recent review, the vast majority of studies employing the ILP merely mobilize the ideational aspects of organizing without addressing the matter of materiality. Given that organizations are ‘multi-modal achievements’ (Jones et al. 2017, p. 638) embedded in and sustained by formal, physical, and technological structures, it is crucial to appreciate ‘how matter matters’ in organization studies (Carlile et al. 2013). The analysis presented next seeks to revive the notion of a dialectic interplay between the material and ideational or formal aspect of institutional logics by considering how organizational interaction and sensemaking is enabled and constrained by both formal and techno-material spaces and boundaries.

In addition to the institutional logics perspective, selected concepts from Goffman’s (1959, 1967) formal sociological studies are employed to discuss the interpersonal dynamics between volunteers and beneficiaries. Although the Goffmanian concepts relate to face-to-face co-presence, micro-sociological concepts have previously proven fruitful for understanding interpersonal face-to-screen interaction (Knorr-Cetina & Bruegger, 2002).

In the analysis, this theoretical bricolage serves as a multi-focal lens that is sensitive to the dynamics of inequality in interpersonal digital interaction yet mindful of the organizational and institutional contexts informing, enabling, and restraining such interaction.

The Case Study of Project Virtual Tutoring

The following analysis is based on data from an 18-month, in-depth single case study of project virtual tutoring (PVT). PVT was launched in 2010 by employees at a public library in a large Danish city to establish a digital, anonymous, flexible, and voluntary tutoring option for boys with immigrant backgrounds from socially disadvantaged areas. This group was targeted because of their high dropout rates and lack of interest in physical homework cafés, which was attributed to the physical presence requirement. PVT was funded by short-term state grants, contingent on PVT’s meeting several performance goals and providing quarterly progress reports to a steering committee. In response to these demands and thanks to persistent efforts by PVT’s entrepreneurial CEO, the number of call centres increased from one to five over a four-year period, while the number of volunteers more than doubled from 70 to 150, along with more users, more homework sessions, and expanded opening hours. PVT also formed a strategic partnership with a private ICT company that provided expertise and corporate volunteers in exchange for a seat on the steering committee.

The virtual tutoring was provided by students and corporate volunteers, all of mainly long-term Danish ancestry. The student volunteers sat together in call centres—rooms separate from the daily operations of the library and equipped with computers with integrated cameras and headsets. The corporate volunteers conducted their virtual tutoring from locales at their local company division that were also equipped with computers and headsets. This paper focuses on the interaction between student volunteers and pupils, henceforth referred to as ‘users’ according to PVT practice.

During a shift, student and corporate volunteers logged in to the same virtual site created especially for PVT. The tutoring site allowed for mediated (face-to-screen) interactions through an integrated camera, talking using a microphone, and/or writing by employing an integrated chat module. To receive tutoring, users accessed the site from a private computer and logged in with an anonymous profile. Volunteers logged in with a profile showing their real first name and the subjects they could help with. Based on this information, volunteers and users were matched by a so-called controller, a PVT staff member. On busy nights, sessions were to last no more than 30 min, and the controller notified volunteers who exceeded this limit. While it was mandatory for volunteers to leave their camera on during interactions, users could deselect both camera and audio.

PVT was strategically selected (Flyvbjerg, 2006) as a case that would provide in-depth information on how inequality in volunteer–user interaction is produced or mitigated by the techno-material and formal aspects of the organizational context. The wider national context of the study is Denmark, a Scandinavian welfare state considered a world leader in digitalization (Eimhjellen, 2019). Moreover, tendencies towards competition, marketization, and professionalization have been observed to be increasing within the Danish third sector (Grubb and Henriksen 2019). While insights from the single case study of PVT cannot be generalized in the statistical sense, they may nevertheless serve as a point of departure for further studies on how digitalization and increased competition in interdependency affect intra-organizational sensemaking and interaction in voluntary organizations.

Methods and Analytic Strategy

The findings presented next are based on a mixture of qualitative data derived from 18 months of participant observation, semi-structured interviews, focus groups, and document analysis. To observe the patterns of verbal and non-verbal communication across organizational settings (Luhtakallio & Eliasoph, 2014), I conducted fieldwork between 2013 and 2014 at three call centres across Denmark. I served as a virtual tutor, participated in training courses, and attended social gatherings for volunteers. Additionally, I attended seminars, launch events, and other occasions where PVT presented itself to external audiences. To gain insight into volunteers’ and staff members’ experiences of interacting within a digitalized organization, I conducted semi-structured interviews with 13 volunteers and 6 staff members and 3 focus groups with volunteers. A total of 29 people were interviewed. Interviews lasted between 45 and 60 min and were transcribed in their entirety. Finally, analogue and digital organizational documents, such as project plans and newsletters, were reviewed to scrutinize PVT’s internal and external storytelling. The analytic themes presented in the sections below were developed inductively through a process in which central patterns identified during fieldwork served as the basis for vertical and horizontal readings of field notes, interview transcripts, and organizational documents to assess their prevalence.

Analysis

As a prelude to the analysis of how volunteer–user interaction is shaped by the formal and techno-material spaces and boundaries of PVT, the next section presents a portrait of the institutional logics informing the work of PVT. Approaching digital interaction through the institutional environment sustains the pursuit of avoiding technological determinism when interpreting digital interactions.

Exploring the Hybrid Organization PVT

Across organizational documents, meetings with representatives from the steering committee, launch events at public libraries, and external storytelling on its official homepage, PVT emerged as an organization oriented towards several institutional logics. As with most third sector organizations, PVT was thus an organizational hybrid (Skelcher & Smith, 2015), responsive to competition and institutional turbulence in its environment. Like any small entrepreneurial enterprise, PVT strove to create a competitive advantage by cultivating a multi-stranded organizational identity as being civic minded, socially engaged, and efficient.

Aspirations to the civic logic came across in multiple ways. A press release published when PVT won an award for ‘best digitalized welfare project’ highlighted that it was ‘based on the engagement of young people as active digital citizens and included civil society in innovative ways’. At meetings with new partners, the CEO stressed how their online service was unique because of the engagement of volunteers. Moreover, the large share of satisfied users, who were quoted on the PVT website, was routinely attributed to the authentic personal engagement of the volunteers. Highlighting the engagement of volunteers as key to the unique service demonstrated how PVT was conceived and nurtured by a political discourse that casts volunteers as representatives of an authentic, egalitarian sociality that benefits users. Moreover, emphasizing the social commitment of volunteers resonated with the second key aspiration of PVT: providing a voluntary service that supplemented public education services by catering to those falling behind in the established school system.

Finally, PVT aspired to present itself as an efficient, user-oriented organization. This aim was reflected particularly well in a status report distributed to all stakeholders, in which PVT management stated how it intended to increase opening hours and double the number of weekly sessions, volunteers, and user profiles over the following two years. Regarding users and volunteers, the report stated the following goals: ‘At least 75% [of users] are satisfied with the help they receive. […] at least 75% [of volunteers] experience overall satisfaction with their volunteer job’ (PVT status report). Pursuing user satisfaction benchmarks and other quantifiable performance measures has traditionally been associated with organizations in the private sector. In the current institutional environment, which is characterized by competition over short-term funding, voluntary organizations have been observed to act in an increasingly ‘businesslike’ manner and to adapt so-called managerial logics known from private, market-oriented organizations (Maier et al. 2016; Shoham et al. 2006). In adapting a service-minded responsiveness to the demands of stakeholders and users, implementing managerial techniques known from private corporations (Maier et al. 2016, p. 70), and perpetually striving for growth, PVT did indeed act ‘businesslike’.

While PVT thus responded to several institutional logics, among which the market-inspired managerial logic seemed most prominent, the important question in this context is how these logics, in interdependency with ICT, enabled and informed the interaction between users and volunteers. To this end, spending time among the volunteers as a virtual tutor revealed several patterns. Notably, as indicated by this paper’s title, it turned out that PVT’s reliance on digital technologies in interdependency with its orientation towards a managerial logic enabled an efficient, task-focused, service-minded interaction with limited possibilities for the type of intimacy-seeking that motivates volunteers and haunts scholars. The following three analytic sections each explore one facet of how this bounded interaction was produced and how it impeded volunteers from pursuing intimacy on the premises they established.

Avoiding the Background: Interaction Bounded by Techno-material and Formal Boundaries

This first part of the analysis shows how techno-material, formal, and temporal boundaries together enabled an activity-centred form of interaction that allows both parties to avoid the background of the other and, thus, intimacy. The most obvious demarcation of a bounded interaction between users and volunteers was techno-material. Due to ICT, users could access the tutoring site from private computers, while volunteers accessed the site using computers in call centres. As the project leader explained during an interview, this setup was a deliberate managerial decision to limit potential experiences of stigmatization:

This way of providing a helping hand via an online platform can be a way to meet them [users] on their home turf, where they already spend a lot of time. And it is an anonymous kind of help. It can be a huge advantage that they don’t have to show up physically in a homework cafe and ‘flash’ that they need help.

Virtual volunteering allowed users to avoid stigmatizing gazes from peers and adult supervisors at physical homework cafés while also preventing face-to-face interaction with volunteers. Although the volunteers had a general idea of the category to which a user belonged (Lamont et al. 2014), the multiple visible cues that indicate socio-economic status and other cultural affiliations in face-to-face interaction (Goffman, 1959) were cloaked.

Several formal and temporal boundaries contributed to sustaining a fragmented interaction. Across national divisions and local settings, PVT exposed a pronounced fondness for formal guidelines that served to standardize volunteer–user interactions and make them more efficient. The first place where volunteers encountered these demarcations was at the mandatory one-day introductory course that all aspiring volunteers had to attend. In these courses, the project leaders presented a number of guidelines for virtual interaction. One set of rules regarded the role of the volunteers during virtual interaction:

Aspiring volunteers are instructed to meet the pupils in an appreciative way, provide ‘help-to-self-help’, and act and think positively about the users. This positive attitude shall not, however, be confused with the role of a ‘parent’ or other caretakers. On the contrary, the course leader emphasizes, that the role of the volunteer is strictly academic, limited to the well-defined assignment that the user presents (Fieldnotes, introductory course, PVT).

Far from providing instructions to act as ‘beloved aunties’ (Eliasoph, 2011) or develop a ‘close and trustful relationship’ with users (Villadsen, 2008), volunteers at PVT were to engage in a positive but not overtly caring way, focusing on the assignment rather the person presenting it. As additional insurance against excessive emotional and personal engagement, the formal boundaries extended to the possible attitudes and topics volunteers were to deal with:

The course leader talks about the possibility of getting ‘unserious’ pupils on the line. They can be rude, but they may also present the volunteers with personal problems such as grief or other topics unrelated to homework. Such pupils should be advised to consult websites specialized in the relevant issue (Fieldnotes, introductory course, PVT).

The purpose of the interaction was to solve a specific task, not build a personal relationship, and the formal and techno-material boundaries worked together to achieve this end.

The temporal border further assisted in keeping the interaction activity-focused and non-intimate. Volunteers and users were repeatedly instructed to limit each session to a maximum of 30–45 min, depending on the number of users waiting. To sustain the temporal boundary, users were instructed to select one well-defined task, while volunteers were instructed to begin each session by setting a realistic goal. These mutually sustaining instructions allowed PVT to provide a large number of sessions per shift, in accordance with their stakeholder agreements. Volunteers, for their part, perceived of them as a tool that sustained, rather than compromised, the overall mission of providing a unique social service through appreciative tutoring. As the volunteers explained, the temporal boundary was established out of concern for users waiting in line. Moreover, the boundary provided a legitimate reason for ending a session that had gone awry, without having to place any blame on the user.

Besides their concern for the users, the volunteers’ commitment to the time limit could be attributed to the circumstance that a managerial logic which encouraged time-efficient interaction was formally sustained both through verbal and written guidelines and grounded materially in the digital and physical spaces framing the interaction (Jones et al. 2017). In all call centres, the digital waiting line was projected onto the most visible wall in the room, ensuring that the number of pupils in line, the time they had been waiting, and who they were in session with were visible to all volunteers. Aside from the blue light from the quivering digital queue, no posters or other aesthetic artefacts competed for visual attention in the call centres, which made inefficient procrastination feel like a breach of a materially grounded norm of efficient volunteering. Moreover, the virtual platform on which the tutoring was conducted was equipped with a small timer in the top right corner of each screen that began counting down at the beginning of a new session, allowing volunteers to monitor and discipline themselves to maintain a focused and efficient interaction. As volunteers typically participated in an episodic way and rarely spent time interacting in a manner that would permit new volunteers to learn from experienced ones, this material grounding of the time-efficient norm enabled the transmission of cues about the ‘organizational style’ (Eliasoph, 2011; xii) to new volunteers, independent of personal interaction (Jones et al., 2017). In interdependency, the formal and techno-material aspects of PVT thus sustained the temporal boundary and the ideal of keeping interactions efficient while leaving the background out of sight, both literally and cognitively.

As previous studies have shown that intimate relationships with users is a key motivational factor for volunteers, I was surprised to learn that the volunteers at PVT accepted, even appreciated, the multiple boundaries that prevented intimate relationships:

IP: I liked being how you were there, but physically somewhere else than those whom you helped.

Int.: You liked that?

IP: Yes, because the commitment would be different otherwise. I did not have to engage myself personally. They did not have to know who I was and vice versa […]. The only thing they knew was that I wanted to help them. I liked that distance. You were free from personal information.

Int: Okay… and you liked it that way?

IP: Yes, it made the communication easier with some of these young people because they did not have to make excuses for themselves or apologize for how bad they really were. […]. I could meet them without being prejudiced in any way. I think this is a huge advantage for PVT as opposed to the physical tutoring cafes. […] You could engage yourself during the time you were in a session and put it behind you afterwards. You did not have to take a personal story home with you, and I did not want that either. […] I sat safely behind my screen, and so did they.

Contrary to the volunteer tourists who were attracted by the possibility of meeting natives at their own homes and ‘feeling their heartbeat’ (Conran, 2011), the PVT volunteers found the limited access to users’ backgrounds appealing:

Int: So, what is your impression of those at the other end… Is it something you think about?

IP: Well, in the concrete situation, I don’t think about that at all. What kind of types… Not at all, and I think it is because the assignment takes up all my focus.

Int: And you liked that, you said?

IP: Yes, I do because … It is not that I don’t like it the other way, but I like this a lot because I think for them and for me, the academic is in focus. It gets things moving, I think.

The establishment of the role as a professional rather than a caregiving, tutor and the time limit thus worked as mutually reinforcing demarcations that ‘got things moving’. Users could not express problems beyond one particular assignment within 30 min, and those who did could be politely redirected to the appropriate website.

In sum, the interplay between techno-material, formal, and temporal boundaries produced an activity-centred interaction that allowed both parties to avoid intimacy. In light of studies on the dark side of intimacy-seeking behaviour among volunteers, one could argue that the multi-modal, interdependent boundaries served the noble purpose of grounding an organizational norm of efficient, impersonal interactions to the benefit of the users. In fact, the organizational setup enabled both users and volunteers to avoid intimacy and the potentially intolerable sensation of intrusion when confronted with the familiar space of another person (Breviglieri, 2009).

Avoiding Sociality: Suspending Sociability as Criterion for Getting Help

As a result of an institutional environment characterized by short-term funding and competition, PVT constantly entered into partnerships with public and private organizations to increase capacity and secure sustainable funding. Consequently, a vast network of organizational subdivisions developed, with ICT serving as a facilitating structure for the complex intra-organizational coordination that PVT required (Bernholz, 2017). The digital platform enabled tutoring shifts to be covered by student volunteers in one part of the country and by corporate volunteers in another. Both groups could simultaneously access the tutoring site while the controller supervised the digital interactions from a distance. Moreover, because the task rather than the personal relationship was the focus of the digital interaction, volunteers could easily refer users to volunteers with better qualifications. Users, for their part, were not stuck with an incompetent volunteer, which was found to be the case at American homework cafés where users were at the mercy of the volunteers on a given day (Eliasoph, 2011). Moreover, the integration of ICT, combined with the marketized mindset of the management, allowed for longer opening hours designed to meet the needs of both users and volunteers.

A third way in which the organizational design assisted in making the task-based interaction work to the benefit of the users was the controller in charge of matching volunteers and users. A widely observed and criticized tendency within social work and hybrid workfare programmes is a phenomenon known as ‘creaming’, which refers to the selection of clients with the most potential for progress (Garrow & Hasenfeld, 2014). The creaming phenomenon has also been observed in voluntary social work. In the case of Danish homeless shelters, Villadsen (2008) noted that managers used the sociability and extroverted behaviour of users as subtle criteria for differential treatment, which benefitted those showing the most signs of sociability. At the physical homework cafés, volunteers would ‘run to get seats next to participants who were easy to help’ while avoiding those ‘hard to bond with’ (Eliasoph, 2011, p. 117). At PVT, differential treatment based on physical appearance, sociability, and other subjective preferences was prevented by the controller, who matched users and volunteers strictly according to academic and temporal criteria. This intermediary function sustained an interaction that placed the activity—not the personal relationship—at the centre. The activity-focused relation was further sustained by the ability of users to change their anonymous profile name. During one session, several volunteers complained about a user ‘being rude’, as he or she started writing back in capital letters. As usual, the user interacted exclusively through the chat function, but as one volunteer explained, getting answers written in caps lock felt like being yelled at symbolically. Serving as a tutor myself that evening, I noted the alias of this user, secretly hoping that we would not be matched. The next time I took a shift, I was matched with someone who used caps lock to ‘yell’, but as the user went by another alias, it was impossible to tell whether this was the same person or someone else. Even the temptation to create positive or negative narratives about anonymous users was thus hampered by the ease with which they could change aliases.

Avoiding Loss of Face: Digitally Sustained Impression Management

The third circumstance that limited intimacy-seeking behaviour, mainly benefitting volunteers, was that users preferred to communicate without the camera and sound. While volunteers were obliged to leave their cameras on unless otherwise agreed upon, surveys conducted by PVT documented that the most common form of interaction was chatting without a camera. As studies on mediated communication have shown, meeting on a platform, face-to-screen instead of face-to-face, limits the possibility of expressing and exchanging ‘glances, gestures, positioning and verbal statements’ (Licoppe & Morel, 2012, p. 399), which Goffman defined as indispensable cues to performing the interaction ritual in face-to-face co-presence (1967). In the case of PVT, the possibility of limiting access to these cues was given exclusively to the users, which created an asymmetrical audio–visual power balance to the users’ advantage. Users could control the visual and audible information they ‘gave off’ (Goffman, 1959, p. 2), in addition to the information they deliberately communicated over chat. With a slight ICT-based adaptation of the Goffmanian inventory, it could be argued that users thus conducted ‘digitally sustained impression management’ (Goffman, 1959, p. 208). Because of the asymmetrical auditory and visual power balance, users could leave the interaction temporarily, or permanently, without an explanation.

Regarding face-to-face interaction and visual perception, Simmel once remarked: ‘By the same act that the subject tries to acknowledge the object, it is already at the mercy of the object. You cannot take with the eyes without giving at the same time’ (1998 [1908], p. 75). The mediated interaction at PVT challenged this basic rule of reciprocity in visual perception. Because of the combination of mediated interaction and formal rules that legitimated the deselection of sound and vision, it was, in fact, quite possible for users to ‘take with their eyes’ while refusing visual access to volunteers. This circumstance arguably gave users an advantageous interactional position during sessions. Allowing for this audio–visual imbalance to the advantage of users sustained the notion of PVT as an organization oriented towards a market-inspired managerial logic that put the needs and favourable ‘reviews’ of users first. Regarding inequality, it further shifted the power dynamics towards the users. The interactional asymmetry, however, frustrated the volunteers, who had to fulfil the role of a service-minded, positive tutor without verbal or visual response and without knowing what caused slow or missing answers. While potentially equalizing the power balance, the asymmetrical visual, temporal, and auditory interaction thus seemed to work counter to the organizational ambition of providing efficient tutoring. Moreover, it created frustrations among one of the stakeholder groups that PVT management valued: the volunteers. On the one hand, relying on ICT thus enabled PVT to increase opening hours, reach more users, and frame an activity-focused, efficient interaction. On the other hand, the legitimate deselection of the camera and sound by users hampered communication and, arguably, complicated tutoring. Such organizational paradoxes are common in hybrid organizations informed by multiple institutional logics (Eliasoph, 2011; Skelcher & Smith, 2015) and resolving them lies beyond the boundaries of this paper. In the case of PVT, the central finding is that the combination of ICT and the managerial logic mitigated inequality.

Conclusion and Avenues for Further Research

This paper contributes knowledge on the underexplored topic of mediated volunteer–user interaction through an in-depth case study that follows volunteers and users engaged in online tutoring at PVT, a thoroughly digital organization. The research question read as follows:

How is inequality between volunteers and users sustained or mitigated by the formal and techno-material aspects of the organizational context?

Based on fieldwork, interviews, and document analysis, the findings indicate three ways in which reliance on ICT in interdependence with a pronounced orientation towards a managerial logic produce a bounded, time-efficient form of interaction. First, the techno-material and formal boundaries together sustain a form of interaction that places the focus on the activity, not personal relations and background information. Second, the use of third-party matchmaking and ICT as a facilitating structure prevents sociability from being used as a criterion for the differential treatment of users, thereby hampering creaming. Third, the anonymous mediated interaction combined with a user-oriented organization enabled an audio–visual asymmetry that favoured users, allowing them to perform digitally sustained impression management. These three interconnected organizational features mitigate the risk of intimacy-seeking behaviour on unequal premises established by volunteers.

In conjunction with the organizational reliance on ICT and a marketized orientation towards user satisfaction, PVT enabled what we might call ‘volunteering on demand’: digitally available volunteering tailored to the schedules and demands of each user. When practicing volunteering on demand, structurally defined categories such as ‘resourceful volunteer’ and ‘at-risk beneficiary’ are overlaid by the roles as ‘service-oriented tutor’ and ‘demanding service user’. Not only did the organizational design thus mitigate the risk of volunteers seeking intimacy instead of providing help, it also contributed to levelling the structural inequality at the interpersonal level in interaction.

While the single case study design proved useful for providing an in-depth analysis of an underexplored phenomenon (digital voluntary interaction), additional studies based on complementary methodological designs are needed to challenge, substantiate, and extend the findings. Below, I specify the contribution of the paper in regard to digitalization and volunteering before suggesting three ways in which future research could complement the limitations of the present study while building on its theoretical and empirical findings.

By reviving the notion of institutional logics as materially grounded (Jones et al. 2013) and showing how organizational reliance on ICT and managerial logics enable an efficient, user-oriented form of volunteering, this paper contributes knowledge on the underexplored topic of how ICT affects voluntary social work. Moreover, in documenting the dialectic interplay between ICT and organizational efficiency, the paper contributes to the current academic debate on the mechanisms contributing to the rationalization and hybridization of the third sector (Henriksen et al. 2015; Hwang & Powell, 2009; Maier et al. 2016; Skelcher & Smith, 2015), in which ICT so far has remained strangely absent in the line-up of usual suspects.

However, by focusing on inequality in volunteer–user interaction, the paper has explored a mere fraction of the vast array of topics at the intersection of ICT and voluntary organizing. At least three topics deserve further attention.

First, the ethical, political, and practical perspectives of digitalized programmes like PVT should be systematically investigated. Whereas this analysis focused on how boundaries mitigate the risk of intimacy-seeking behaviour to the benefit of the users, an unsettling suspicion could be that the possibility of avoiding intimacy primarily benefitted the volunteers. From a safe distance, the volunteers could experience the pleasure of altruism without excessive personal engagement and without the risk of experiencing ‘long-term emotional weight’ and ‘burnout’ observed among practitioners in the voluntary penal sector (Quinn & Tomczak, 2021, p. 85). Perhaps PVT was, in fact, another case of how middle-class volunteers define the premises of interaction—only this time with the reverse objective: to avoid intimacy instead of pursuing it. What if users needed more care, time, and proximity? Such needs were excluded by design at PVT, and exploring the experiences of the users was beyond the scope of this paper. Further studies on virtual volunteering should look into the ethical aspects of mediated help and include user perspectives and experiences.

Second, the fact that the background of the other, both literally and cognitively, was out of sight during most sessions could prevent volunteers from developing curiosity and concern about the structural factors causing the need for tutoring in the first place. The possibility of avoiding intimacy may, in other words, be conducive to ‘avoiding politics’ (Eliasoph, 1998), preventing personal experiences from transitioning into subjects of public engagement (Thévenot, 2019). Whether fragmented, digital interaction may sustain or deter civic action in the long run is another question that merits further study.

Finally, the data presented here reflect interaction within a Danish organization embedded in a Scandinavian welfare state. Further studies could explore whether and how the preferences for distanced interaction vary according to institutional environment, geographical context and regime type. Indeed, the overall topic of inequality in volunteering calls for more comparative studies that seek to grasp how different ways of organizing, legitimizing, and evaluating voluntary work produce inequality between various actors at the intra-organizational level.

References

Ackermann, K., & Manatschal, A. (2018). Online volunteering as a means to overcome unequal participation? The profiles of online and offline volunteers compared. New Media and Society, 20(12), 4453–4472.

Amichai-Hamburger, Y. (2008). Potential and promise of online volunteering. Computers in Human Behavior, 24(2008), 544–562.

Bennett, W. L., & Segerberg, A. (2012). The logic of connective action: Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Information, Communication & Society, 15(5), 739–768.

Bernholz, L. (2017). Creating digital civil society. In R. Reich, C. Cordelli, & L. Bernholz (Eds.), Philanthropy in democratic societies: History, institutions, values. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Brainard, L. A., & Brinkerhoff, J. M. (2004). Lost in cyberspace: Shedding light on the dark matter of grassroots organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 33(3), 32–53.

Breviglieri, M. (2009). L’insupportable. L’excès de proximité, l’atteinte à l’autonomie et le sentiment de violation du privé. In M. Breviglieri, C. Lafaye, & D. Trom (Eds.), Compétences critiques et sens de la justice. (pp. 125–149). Paris: Economica.

Carlile, P., Nicolini, D., Langley, A., & Tsoukas, H. (2013). How matter matters: Objects, artifacts, and materiality in organization studies. Oxford University Press.

Carlsen, H. B., Doerr, N., & Toubøl, J. (2020). Inequality in Interaction: Equalising the Helper-Recipient Relationship in the Refugee Solidarity Movement. Voluntas. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-020-00268-9.

Carlsen, H. B., Toubøl, J., & Brincker, J. (2020). On solidarity and volunteering during the COVID-19 crisis in Denmark: The impact of social networks and social media groups on the distribution of support. European Societies. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2020.1818270.

Conran, M. (2011). They really love me! Intimacy in volunteer tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(4), 1454–1473.

Cravens, J. (2000). Virtual volunteering: Online volunteers providing assistance to human service agencies. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 17(2–3), 119–136.

Dhebar, B. B., & Stokes, B. (2008). A nonprofit manager’s guide to online volunteering. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 18(4), 497–506.

Eimhjellen, I. (2014). Web technologies in practice: The integration of web technologies by environmental organizations. Media, Culture & Society, 36(6), 845–861.

Eimhjellen, I. (2019). New forms of civic engagement: Implications of social media on civic engagement and organization in Scandinavia. In L. S. Henriksen, K. Strømsnes, & L. Svedberg (Eds.), Civic engagement in Scandinavia: Volunteering, informal help and giving in Denmark, Norway and Sweden. (pp. 135–152). Springer.

Eliasoph, N. (1998). Avoiding politics: How Americans produce apathy in everyday life. Cambridge University Press.

Eliasoph, N. (2009). Top-down civic projects are not grassroots associations: How the differences matter in everyday life. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 20(3), 291–308.

Eliasoph, N. (2011). Making volunteers: Civic life after welfare’s end. Princeton University Press.

Evers, A., & von Essen, J. (2019). Volunteering and civic action: Boundaries blurring, boundaries redrawn. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 30, 1–14.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219–245.

Friedland, R., & Alford, R. R. (1991). Bringing society back. In: Symbols, practices, and institutional contradictions. In W. Powell & P. J. DiMaggio (Eds.), The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. (pp. 232–266). University of Chicago Press.

Garrow, E., & Hasenfeld, Y. (2014). Social enterprises as an embodiment of a neoliberal welfare logic. American Behavioral Scientist, 58(11), 1475–1493.

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Anchor Books.

Goffman, E. (1967). Interaction ritual: Essays on face-to-face behaviour. Pantheon Books.

Gotved, S. (2006). Time and space in cyber social reality. New Media & Society, 8(3), 467–486.

Grubb, A., & Henriksen, L. S. (2019). On the changing civic landscape in Denmark and its consequences for civic action. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 30(1), 62–73.

Hallett, T., & Ventresca, M. J. (2006). Inhabited institutions: Social interactions and organizational forms in Gouldner’s Patterns of Industrial Bureaucracy. Theory and Society, 35(2), 213–236.

Henriksen, L. S., Smith, S. R., & Zimmer, A. (2015). Welfare mix and hybridity: Flexible adjustments to changed environments. Introduction to the special issue. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 26, 1591–1600.

Hernes, T., & Schultz, M. (2020). Translating the Distant into the Present: How actors address distant past and future events through situated activity. Organization Theory, 1(1), 2631787719900999. https://doi.org/10.1177/2631787719900999.

Hustinx, L. (2010). Institutionally individualized volunteering: Towards a late modern re-construction. Journal of Civil Society, 6(2), 165–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/17448689.2010.506381.

Hustinx, L., Handy, F., & Cnaan, R. (2010). Volunteering. In R. Taylor (Ed.), Third sector research. (pp. 73–89). Springer.

Hwang, H., & Powell, W. W. (2009). The rationalization of charity: The influences of professionalism in the nonprofit sector. Administrative Science Quarterly, 54(2), 268–298. https://doi.org/10.2189/2Fasqu.2009.54.2.268.

Ihm, J. (2017). Classifying and relating different types of online and offline volunteering. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 28(1), 400–419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-016-9826-9.

Jones, C., Boxenbaum, E., & Anthony, C. (2013). The immateriality of material practices in institutional logics. In M. Lounsbury & E. Boxenbaum (Eds.), Institutional Logics in Action, Part A (Research in the Sociology of Organizations). (Vol. 39, pp. 51–75). Emerald Group Publishing.

Jones, C., Meyer, R., Jancsary, D., & Höllerer, M. (2017). The material and visual basis of institutions. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, T. B. Lawrence, & R. Meyer (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism. (2nd ed., pp. 621–646). Sage.

Knorr-Cetina, K., & Bruegger, U. (2002). Global microstructures: The virtual societies of financial markets. American Journal of Sociology, 107(4), 905–950. https://doi.org/10.1086/341045.

la Cour, A. (2019). The management quest for authentic relationships in voluntary social care. Journal of Civil Society, 15(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/17448689.2018.1551864.

Lamont, M., Beljean, S., & Clair, M. (2014). What is missing? Cultural processes and causal pathways to inequality. Socio-Economic Review, 12(3), 573–608. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwu011.

Licoppe, C., & Morel, J. (2012). Video-in-interaction: ‘Talking heads’ and the multimodal organization of mobile and Skype video calls. Research on Language and Social Interactions, 45(4), 399–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2012.724996.

Luhtakallio, E., & Eliasoph, N. (2014). Ethnography of politics and political communication: Studies in sociology and political science. In K. Kenski & K. H. Jamieson (Eds.), Oxford handbook of political communication. Oxford University Press.

Ma, J., & Konrath, S. (2018). A century of nonprofit studies: Scaling the knowledge of the field. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 29(6), 1139–1158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-018-00057-5.

Maier, F., Meyer, M., & Steinbereithner, M. (2016). Nonprofit organizations becoming business-like: A systematic review. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 45(1), 64–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0899764014561796.

Mukherjee, D. (2011). Participation of older adults in virtual volunteering: A qualitative analysis. Ageing International, 36(2), 253–266.

Orlikowski, W. J., & Scott, S. V. (2016). Digital work: A research agenda. In B. Czarniawska (Ed.), A research agenda for management and organization studies. (pp. 88–96). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Piatak, J., Dietz, N., & McKeever, B. (2019). Bridging or deepening the digital divide: Influence of household Internet access on formal and informal volunteering. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 48(2S), 123S – 150.

Plesner, U., & Husted, E. (2020). Digital organizing: Revisiting themes in organization studies. Springer.

Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon and Schuster.

Quinn, K., & Tomczak, P. (2021). Practitioner niches in the (Penal) voluntary sector: Perspectives from management and the frontlines. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 32(1), 78–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-020-00301-x.

Salamon, L. M., & Anheier, H. K. (1998). Social origins of civil society: Explaining the nonprofit sector cross-nationally. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 9(3), 213–248. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022058200985.

Shoham, A., Ruvio, A., Vigoda-Gadot, E., & Schwabsky, N. (2006). Market orientations in the nonprofit and voluntary sector: A meta-analysis of their relationships with organizational performance. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 35(3), 453–476.

Simmel, G. 1998 [1901–1908]. Hvordan er samfundet muligt: Udvalgte sociologiske skrifter. Copenhagen: Gyldendal.

Skelcher, C., & Smith, S. R. (2015). Theorizing hybridity: Institutional logics, complex organizations, and actor identities: The case of nonprofits. Public Administration, 93(2), 433–448. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12105.

Thévenot, L. (2019). How does politics take closeness into account? Returns from Russia. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, 33, 221–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10767-019-9322-5.

Villadsen, K. (2008). Doing without state and civil society as universals: ‘Dispositifs’ of care beyond the classic sector divide. Journal of Civil Society, 4(3), 171–191.

Wilson, J., & Musick, M. (1997). Who cares? Toward an integrated theory of volunteer work. American Sociological Review, 62(5), 694–713. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657355.

Acknowledgements

The author warmly thanks Itamar Shachar, Paul Rameder, and Lesley Hustinx—co-guest editors of this special issue of Voluntas—for inspiring comments throughout the writing process. Earlier drafts received valuable comments from Nina Eliasoph, Morten Frederiksen, Claus Levinsen, Anders la Cour, Christoph Brandtner, Alexis Pang, Nathalie Perregaard, and scholars affiliated the Center for Inclusion and Welfare (CIW), at Aalborg University. Finally, I thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive and helpful comments.

Funding

The empirical study, on which the article is based, was conducted as part of the authors doctoral thesis that was partly funded by a grant (§ 15.75.09.30—‘Research on civil society and volunteering’) from the Danish Ministry of Social Affairs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grubb, A. Avoiding Intimacy—An Ethnographic Study of Beneficent Boundaries in Virtual Voluntary Social Work. Voluntas 33, 72–82 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-021-00350-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-021-00350-w