Abstract

Volunteer management practices have been shown to have positive effects on employees in terms of skill development, job success, organizational identity, and morale in the public, nonprofit, and corporate sectors. Despite considerable research on volunteering, questions remain about how management practices of volunteer programs may affect volunteer performance. Leveraging data comparing self-enrolled and corporate-recruited volunteer mentors into a large-scale online program for entrepreneurs, this study measures the impact of institutional support on volunteer intensity, persistence, and quality. It also presents a novel way to measure volunteer quality through sentiment analysis to measure the tone of online messages, an emerging statistical technique. Findings suggest that a high level of institutional support leads to higher quality mentor engagement, compared to self-enrolled volunteers, while a low level of support leads to mentor quality much lower than self-enrolled volunteers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

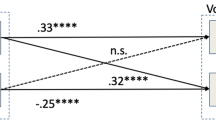

org.program represents the independent variable of interest, Organization Client Program (Yes) and the three levels of institutional support. This specification is the same across all models.

References

Aryee, S., Chay, Y. W., & Chew, J. (1996). The motivation to mentor among managerial employees: An interactionist approach. Group & Organization Management, 21(3), 261–277.

Baqapuri, A. I. (2015). Twitter sentiment analysis. arXiv preprint arXiv:1509.04219.

Barraza, J. A. (2011). Positive emotional expectations predict volunteer outcomes for new volunteers. Motivation and Emotion, 35(2), 211–219.

Booth, J. E., Park, K. W., & Glomb, T. M. (2009). Employer-supported volunteering benefits: Gift exchange among employers, employees, and volunteer organizations. Human Resource Management, 48(2), 227–249.

Chacón, F., Vecina, M. L., & Dávila, M. C. (2007). The three-stage model of volunteers’ duration of service. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 35(5), 627–642.

Clary, E. G., & Snyder, M. (1999). The motivations to volunteer: Theoretical and practical considerations. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 8(5), 156–159.

Clary, E. G., Snyder, M., Ridge, R. D., Copeland, J., Stukas, A. A., Haugen, J., & Miene, P. (1998). Understanding and assessing the motivations of volunteers: A functional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1516–1530.

Cláudia Nave, A., & do Paço, A. (2013). Corporate volunteering: A case study centred on the motivations, satisfaction and happiness of company employees. Employee Relations, 35(5), 547–559.

Cnaan, R. A., & Amrofell, L. (1994). Mapping volunteer activity. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 23(4), 335–351.

Cnaan, R. A., & Goldberg-Glen, R. S. (1991). Measuring motivation to volunteer in human services. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 27(3), 269–284.

do Paço, A., Agostinho, D., & Nave, A. (2013). Corporate versus non-profit volunteering—Do the volunteers’ motivations significantly differ? International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 10(3), 221–233.

Dwyer, P. C., Bono, J., Snyder, M., Oded, N., & Berson, Y. (2013). Sources of volunteer motivation: Transformational leadership and personal motives influence volunteer outcomes. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 24(2), 181–205.

Gatignon-Turnau, A.-L., & Mignonac, K. (2015). (Mis)Using employee volunteering for public relations: Implications for corporate volunteers’ organizational commitment. Journal of Business Research, 68(1), 7–18.

Ghosh, R., & Reio, T. G. (2013). Career benefits associated with mentoring for mentors: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83(1), 106–116.

Grant, A. M. (2012). Giving time, time after time: Work design and sustained employee participation in corporate volunteering. Academy of Management Review, 37(4), 589–615.

Hager, M. A., & Brudney, J. L. (2004). Volunteer management practices and retention of volunteers. . Urban Institute.

Hager, M. A., & Brudney, J. L. (2011). Problems recruiting volunteers: Nature versus nurture. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 22(2), 137–157.

Haggard, D. L., Dougherty, T. W., Turban, D. B., & Wilbanks, J. E. (2011). Who is a mentor? A review of evolving definitions and implications for research. Journal of Management, 37(1), 280–304.

Haski-Leventhal, D., Kach, A., & Pournader, M. (2019). Employee need satisfaction and positive workplace outcomes: The role of corporate volunteering. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 48(3), 593–615. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764019829829.

Holt, S. B. (2020). Giving time: Examining sector differences in volunteering intensity. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 30(1), 22–40.

Hu, C., Wang, S., Yang, C.-C., & Wu, T. (2014). When mentors feel supported: Relationships with mentoring functions and protégés’ perceived organizational support: MENTOR POS, MENTORING, PROTÉGÉ POS. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(1), 22–37.

Hustinx, L., Cnaan, R. A., & Handy, F. (2010). Navigating theories of volunteering: A hybrid map for a complex phenomenon. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 40(4), 410–434.

Ivonchyk, M. (2019). The costs and benefits of volunteering programs in the public sector: A longitudinal study of municipal governments. The American Review of Public Administration, 49(6), 689–703.

Jensen, K. B., & McKeage, K. K. (2015). Fostering volunteer satisfaction: Enhancing collaboration through structure. The Journal of Nonprofit Education and Leadership, 5(3), 174–189.

Johnson, W. B., & Ridley, C. R. (2018). The elements of mentoring: 75 practices of master mentors. (3rd ed.). Martin’s Press.

Kouloumpis, E., Wilson, T., & Moore, J. D. (2011). Twitter sentiment analysis: The good, the bad and the omg! ICWSM, 11(538–541), 538–541.

Kram, K. W., & Hall, D. T. (1996). Mentoring in a context of diversity and turbulence. In E. E. Kossek & S. A. Lobel (Eds.), Managing diversity: Human resource strategy for transforming the workplace. (pp. 108–136). Blackwell Publishers.

Lee, F. K., Dougherty, T. W., & Turban, D. B. (2000). The role of personality and work values in mentoring programs. Review of Business, 21(1), 33.

Lee, Y. (2012). Behavioral implications of public service motivation: Volunteering by public and nonprofit employees. The American Review of Public Administration, 42(1), 104–121.

Li, N., Chiaburu, D. S., & Kirkman, B. L. (2017). Cross-level influences of empowering leadership on citizenship behavior: Organizational support climate as a double-edged sword. Journal of Management, 43(4), 1076–1102.

Maki, A., & Snyder, M. (2017). Investigating similarities and differences between volunteer behaviors: Development of a volunteer interest typology. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 46(1), 5–28.

Megginson, D. (1988). Instructor, coach, mentor: Three ways of helping for managers. Management Education and Development, 19(1), 33–46.

Meyer, J. P., Becker, T. E., & Vandenberghe, C. (2004). Employee commitment and motivation: A conceptual analysis and integrative model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(6), 991.

Nelson, H. W., Netting, F. E., Borders, K. W., & Huiber, R. (2007). Volunteer attrition: Lessons learned from oregon’s long-term care ombudsman program. The International Journal of Volunteer Administration, 22(4), 28–33.

Nencini, A., Romaioli, D., & Meneghini, A. M. (2016). Volunteer motivation and organizational climate: Factors that promote satisfaction and sustained volunteerism in NPOs. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 27(2), 618–639.

Nesbit, R., Christensen, R. K., & Brudney, J. L. (2018). The limits and possibilities of volunteering: A framework for explaining the scope of volunteer involvement in public and nonprofit organizations. Public Administration Review, 78(4), 502–513.

Omoto, A. M., & Snyder, M. (2002). Considerations of community: The context and process of volunteerism. American Behavioral Scientist, 45(5), 846–867.

Orth, C. D., Wilkinson, H. E., & Benfari, R. C. (1987). The manager’s role as coach and mentor. Organizational Dynamics, 15(4), 66–74.

Pajo, K., & Lee, L. (2011). Corporate-sponsored volunteering: A work design perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 99(3), 467–482.

Parise, M. R., & Forret, M. L. (2008). Formal mentoring programs: The relationship of program design and support to mentors’ perceptions of benefits and costs. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 72(2), 225–240.

Perry, J. L., Brudney, J. L., Coursey, D., & Littlepage, L. (2008). What drives morally committed citizens? A study of the antecedents of public service motivation. Public Administration Review, 68(3), 445–458.

Peterson, D. K. (2004). Benefits of participation in corporate volunteer programs: Employees’ perceptions. Personnel Review, 33(6), 615–627.

Pinder, C. C. (1998). Work motivation in organizational behavior. . Psychology Press.

Post, S. G. (2005). Altruism, happiness, and health: It’s good to be good. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 12(2), 66–77.

Ragins, B. R., & Cotton, J. L. (1999). Mentor functions and outcomes: A comparison of men and women in formal and informal mentoring relationships. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(4), 529–550.

Rodell, J. B., Breitsohl, H., Schröder, M., & Keating, D. J. (2016). Employee volunteering: A review and framework for future research. Journal of Management, 42(1), 55–84.

Rodell, J. B., & Lynch, J. W. (2015). Perceptions of employee volunteering: Is it “credited” or “stigmatized” by colleagues? Academy of Management Journal, 59(2), 611–635.

Salamon, L., Haddock, M. A., & Sokolowski, S. W. (2017). Closing the gap? New perspectives on volunteering north and south. In J. Butcher & C. J. Einolf (Eds.), Perspectives on volunteering: Voices from the south. (pp. 29–52). Springer International Publishing.

Sarlan, A., Nadam, C., & Basri, S. (2014). Twitter sentiment analysis. In: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Information Technology and Multimedia, 212–216.

Scandura, T. A., & Williams, E. A. (2002). Formal mentoring: The promise and the precipice. In C. L. Cooper & R. J. Burke (Eds.), The new work of work: Challenges and opportunities. (pp. 241–257). Blackwell Business.

Stebbins, R. A. (1996). Volunteering: A serious leisure perspective. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 25(2), 211–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764096252005.

Stebbins, R. (2013). Unpaid work of love: Defining the work–leisure axis of volunteering. Leisure Studies, 32(3), 339–345.

St-Jean, E., & Audet, J. (2012). The role of mentoring in the learning development of the novice entrepreneur. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 8(1), 119–140.

Stukas, A. A., Snyder, M., & Clary, E. G. (1999). The effects of “mandatory volunteerism” on intentions to volunteer. Psychological Science, 10(1), 59–64.

Stukas, A. A., Worth, K. A., Clary, E. G., & Snyder, M. (2009). The matching of motivations to affordances in the volunteer environment: An index for assessing the impact of multiple matches on volunteer outcomes. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 38(1), 5–28.

Vecina, M. L., Chacón, F., Sueiro, M., & Barrón, A. (2012). Volunteer engagement: Does engagement predict the degree of satisfaction among new volunteers and the commitment of those who have been active longer? Applied Psychology, 61(1), 130–148.

Wilson, J. (2000). Volunteering. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 215–240.

Wilson, J. (2012). Volunteerism research a review essay. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41(2), 176–212.

Wilson, J., & Musick, M. (1997). Who cares? Toward an integrated theory of volunteer work. American Sociological Review, 62(5), 694.

Wilson, J., & Musick, M. (1999). The effects of volunteering on the volunteer. Law and Contemporary Problems, 62(4), 141–168.

Young, A. M., & Perrewé, P. L. (2000). The exchange relationship between mentors and Protégés: The development of a framework. Human Resource Management Review, 10(2), 177–209.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights

The research design was approved by the appropriate Institutional Review Board for research involving human subjects.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1—Validation of Sentiment Analysis

Appendix 1—Validation of Sentiment Analysis

The sentiment analysis package provided in TextBlob is trained from movie reviews. Therefore, there may be a concern that it cannot assess the sentiment expressed in messages exchanged between entrepreneurs and mentors. To address this potential concern, we validated the measures by comparing the outputs from the package with an evaluation done by human raters. We randomly picked 2,000 messages out of 126,037 conversation messages in English and asked three graduate research assistants to categorize the messages into four categories: positive, negative, neutral/objective, and ambiguous. Following the practice described in Baqapuri’s (2015) report, we instructed the research assistants to codify the messages with the following criteria.

-

Positive If the entire message has a positive/happy/excited/joyful attitude or if something is mentioned with positive connotations. Also, if more than one sentiment is expressed in the message, but the positive sentiment is more dominant. Example: “You have accomplished a lot so far. Good job!”

-

Negative If the entire message has a negative/sad/displeased attitude or if something is mentioned with negative connotations. Also, if more than one sentiment is expressed in the message, but the negative sentiment is more dominant. Example: “Sorry—I'm probably looking to help someone a bit more established right now and local to the area.”

-

Neutral/Objective If the creator of a message expresses no personal sentiment/opinion in the message and merely transmits information. Advertisements of different products would be labeled under this category. Example: “First I share with you some online pages/articles about Iran and travel to it: CNN's popular article: [PERSONAL WEBSITE].”

-

Ambiguous If more than one sentiment is expressed in the message which is equally potent with no one particular sentiment standing out and becoming more obvious. Also, if it is obvious that some personal opinion is being expressed here, but due to lack of reference to context, it is difficult/impossible to accurately decipher the sentiment expressed. Example: “I kind of like heroes and don’t like it at the same time…”.

The final category is determined by the consensus of the raters, defined as the category upon which two or more raters agree. We had 1,633 messages with two raters assigning the same category, an 82.98% consensus rate. We then reviewed the remaining messages that do not have an agreed-upon category and determine the category for the analysis. Finally, we use the package to generate the polarity and subjectivity scores. The average scores by category are presented in Table

6.

Table 6 shows that positive and neutral messages account for 91% of the sample. This finding is not surprising because we expect people to interact with each other politely when they seek advice or consult others. We then conduct a series of t tests to see whether the package is able to distinguish one category from the other. The results are summarized in the second half of Table 6.

In terms of polarity, the package is able to separate positive messages from the other three categories. The mean polarity score of positive messages is significantly higher than those of the other three. However, the scores for the remaining three categories are not statistically distinguishable. This finding is consistent with the observation that the majority of messages are either positive or neutral. It is rare to see people express strongly negative emotions in business conversations.

In terms of subjectivity, we observe a similar pattern except for that positive and ambiguous messages are not statistically different. This should not be a surprise either according to our coding instruction. A message is coded as ambiguous because it expresses positive and negative emotion in an equal weight. Therefore, it should score high in subjectivity. The finding that negative and neutral/objective messages are not statistically different from each other also suggests that negative messages we see from the sample are not really “negative” but more of “objective.”

Overall, this analysis provides face validity of our construct. While the package is not trained for this study specifically, we are confident that it is able to evaluate sentiments expressed in the message exchanged between mentors and entrepreneurs.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mason, D.P., Chen, LW. & Lall, S.A. Can Institutional Support Improve Volunteer Quality? An Analysis of Online Volunteer Mentors. Voluntas 33, 641–655 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-021-00351-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-021-00351-9