Abstract

Geosocial networking applications (GSN apps) are widely utilized by gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) to meet potential sexual/romantic partners, foster friendships, and build community. However, GSN apps usage has been linked to elevated levels of HIV sexual risk behavior among GBMSM. Little is known about how GSN apps can facilitate HIV sexual risk behaviors, especially among GBMSM in Africa. To fill this gap in research, the present study aimed to characterize the frequency of GSN apps usage and its association with sociodemographic characteristics, sexual health, healthcare access, psychosocial problems, and substance use in a large multicity sample of community-recruited GBMSM in Nigeria (N = 406). Bivariate and multivariable ordinal logistic regression procedures were used to examine factors associated with GSN apps usage. We found that 52.6% of participants reported recent (≤ 3 months) GSN apps use to meet sexual partners. Factors associated with increased odds of GSN apps usage included: being single, having a university degree or higher, reporting higher recent receptive anal sexual acts, being aware of PrEP, having a primary care provider, and reporting higher levels of identity concealment. HIV-related intervention delivered through GSN apps may help curb the spread of HIV among Nigerian GBMSM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nigeria represents 9% of the global burden of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (Emmanuel et al., 2019). Globally, gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) are disproportionately impacted by HIV, compared to the general population (Beyrer et al., 2012). A recent study found that the national HIV prevalence among GBMSM in Nigeria increased from 14% in 2007, to 17% in 2010, and 23% in 2014 (Eluwa et al., 2019), highlighting a growing epidemic among this key population. The study found that older age, receptive anal sex, and a history of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) were associated with HIV seropositivity among Nigerian GBMSM (Eluwa et al., 2019).

Cultural and political factors specific to the lived experience of GBMSM in Nigeria may also contribute to increased risk for HIV infection. In Nigeria, homosexuality is considered taboo and members of society are intolerant of and hostile toward individuals known and/or perceived to be lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) (Balogun, Bissell, & Saddiq, 2020). The Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Act (SSMPA), which was signed into law in 2014, imposes prison sentences on anyone attempting to enter into a civil union with someone of the same sex and anyone who “registers, operates, or participates in gay clubs, societies and organizations or supports such activity.” The law also criminalizes public displays of affection between individuals of the same sex. Since the enactment of the SSMPA, there has been a documented increase in violence against LGBTQ individuals and restrictions on their ability to access health services, particularly HIV prevention and treatment (Schwartz et al., 2015). Criminalization of homosexuality in Nigeria negatively impacts opportunities for GBMSM to physically connect and build community—due to the lack of safe public spaces for LGBTQ people—and may lead them to explore other avenues, such as geosocial networking applications (GSN apps) to meet and interact with other individuals with shared sexual identities and attractions.

GSN apps are primarily utilized by GBMSM to find potential sexual/romantic partners, foster friendships, and build community (Zou & Fan, 2017); however, little is known about how GSN apps can facilitate HIV sexual risk behaviors, especially among GBMSM in Africa. In 2013, a systematic review of GSN apps use among GBMSM in the U.S., Australia, and Asia found that approximately 31–36% of those sampled had used a GSN app and 50–75% of GSN app users had met a sexual partner through that medium (Zou & Fan, 2017). We identified only one study that explored online-sex seeking (through internet websites and GSN apps) among Nigerian GBMSM. The study found that 62% of participants reported online sex-seeking behavior and participants who reported seeking sex online were significantly more likely to be HIV-positive and have a history of other STIs, compared to those who did not seek sex online (Stahlman et al., 2017). This study did not, however, report on psychosocial factors (e.g., depression, anxiety, suicidality) (Oginni et al., 2018, 2020; Ogunbajo et al., 2020b) which may influence the relationship between GSN apps usage and HIV sexual risk.

Given the higher risk for HIV infection among GBMSM who use GSN apps (Holloway et al., 2015; Stahlman et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018; Zou & Fan, 2017), there is a need to further characterize the relationship between GSN apps usage and experiencing psychosocial problems such as sexual minority stress, mental health, and substance use. These include mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, suicidality, and substance use (Oginni et al., 2018; Ogunbajo et al., 2020b) and minority stress factors, such as actual and perceived discrimination and internalized stigma (Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Dovidio, 2009; Oginni et al., 2019). However, few studies have examined associations between minority stress, mental health problems, substance use and GSN apps usage among GBMSM in low- and middle-income countries, including Nigeria. A recent study conducted among GBMSM in the UK found that problematic use of GSN apps was associated with lower psychological well-being, higher psychosocial distress, and increased minority stress compared to non-problematic use of GSN apps (Altan, 2019). There exists a dearth of research on the relationships between GSN app usage and psychosocial health and it is important to elucidate these associations to develop and implement interventions and programs to improve the health and well-being of GBMSM.

To fill this gap in research, the present study aimed to characterize the frequency of GSN apps usage and its association with sociodemographic characteristics, sexual health, healthcare access, psychosocial problems, and substance use in a large multicity sample of community-recruited GBMSM in Nigeria. We hypothesized that individuals with higher frequency of GSN apps usage will have higher levels of psychosocial problems and sexual risk taking. Understanding these relationships is important to inform HIV prevention efforts, especially since GSN apps may be a viable platform to share resources on HIV testing and counseling, HIV prevention (especially pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)), linkage to HIV care services, and other sexual health-related information with GBMSM, particularly in settings where these identities and community members are stigmatized and persecuted.

Method

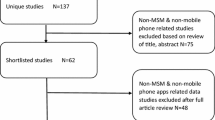

Participants and Procedure

We recruited 406 GBMSM from Abuja (n = 107), Delta (n = 102), Lagos (n = 112), and Plateau (n = 85) from March to June 2019, through community-based organizations (CBOs) and snowball sampling. Peer educators, outreach workers, and key opinion leaders from CBOs based in the four study sites provided potential participants with information about the study and a study contact number. Individuals who showed interest in the study were screened for eligibility. Eligibility criteria were: (1) 18 years of age or older; (2) currently residing in one of four Nigerian states (Abuja, Delta, Lagos or Plateau); (3) identify as cisgender male (i.e., participants who were assigned male sex at birth and currently identify as men); and (4) any self-reported history of sex (oral or anal) with another male. Eligible participants were told to provide information about the study to other members of their social network. The study was approved by the institutional review boards at Brown University and the Nigerian Institute of Medical Research. Informed verbal consent was obtained from each participant prior to enrolling them in study.

Data collection was conducted in the private offices of each CBO. Each participant provided verbal informed consent and completed the quantitative survey with the help of a trained research assistant. The survey took between 1 and 1.5 h to complete. Upon completion of the survey, participants were compensated with 4000 Naira (equivalent to 10 US dollars).

Measures

Question items without a citation were formulated by the research team.

Demographics

Age was assessed by asking participants their current age, and the responses were categorized as 18–24, 25–29, and 30 + years. Relationship status was assessed as single vs. not single (short-term relationship with a man or woman, long-term relationship with a man or woman, married to a man or woman, divorced, widowed, separated). Educational attainment was assessed by asking participants their level of school completion with the following response options: senior secondary school or lower (no formal education, primary school, junior secondary school, senior secondary school), some university or vocational school, university degree or higher (university degree, graduate/post-graduate degree), or other. Sexual orientation was assessed by asking participants to indicate their sexual identity: gay/homosexual, bisexual, straight/heterosexual, questioning, or other. Religious affiliation was assessed as Christian (Catholic, Pentecostal, Protestant), Muslim, or other (traditional religion).

Social Marginalization

Monthly income was assessed by asking participants to provide their monthly income in Naira, and the responses were categorized as: ₦0-₦10,000, ₦10,000-₦30,000, ₦30,000-₦50,000, ₦50,000-₦100,000, or ₦100,000 or more. Employment status was assessed as employed (working full-time, working part-time, self-employed) vs. unemployed (student, unemployed, looking for work, unemployed not looking for work). Financial hardship was assessed by asking participants: “How difficult is it for you to meet monthly payment on bills (rent, electricity, transportation, food, etc.)?” and dichotomized into high financial hardship (“somewhat difficult,” “very difficult,” “extremely difficult”) vs. low financial hardship (“not at all difficult,” “not very difficult”) (Tucker-Seeley, Mitchell, Shires, & Modlin Jr, 2015). History of incarceration was assessed by asking participants: “Have you ever spent time in a prison, jail, or detention center?” with response options yes vs. no.

Sexual Health

Sexual position was assessed by asking participants: “How would you describe your sexual role with respect to anal sex?” (Reponses included “I do not have anal sex,” “bottom,” “versatile bottom,” “versatile,” “versatile top,” “top,” or “other”). HIV status was assessed by asking participants their current HIV status (“HIV-negative,” “HIV-positive,” or “I don’t know”). HIV status responses were dichotomized into HIV-negative/I don’t know vs. HIV-positive. History of STIs were assessed by asking participants: “In your lifetime, have you ever been told by a medical provider that you have a STI not including HIV such as gonorrhea, syphilis, chlamydia, genital warts, herpes, etc.?” with response options “yes” vs. “no.” STIs in the last year was assessed by asking participants: “In the past year, have you ever been told by a medical provider that you have a STI not including HIV such as gonorrhea, syphilis, chlamydia, genital warts, herpes, etc.?” with response options “yes” vs. “no.”

Number of receptive anal sex acts in the last 30 days was assessed by asking participants: “How many times did you have receptive anal sex(bottom) with a male sexual partner in the past 30 days?” with continuous response options. Responses were categorized (0, 1, 2–3, 4–5, 6+). Number of insertive anal sex acts in the last 30 days was assessed by asking participants: “How many times did you have insertive anal sex(top) with a male sexual partner in the past 30 days?” with continuous response options. Responses were categorized (0, 1, 2–3, 4–5, 6+). Condom use for receptive anal sex acts in the last 3 months was assessed by asking participants: “In the last 3 months, of the times you had receptive anal sex (bottom) with a male sexual partner how often were condoms used?” with response options “never,” “almost never,” “about half the time,” “almost always,” “always,” and “I didn’t bottom in last 3 months” and dichotomized into “always” and “not always.” Condom use for insertive anal sex acts in the last 3 months was assessed by asking participants: “In the last 3 months, of the times you had insertive anal sex (top) with a male sexual partner how often were condoms used?” with response options “never,” “almost never,” “about half the time,” “almost always,” “always,” and “I didn’t top in last 3 months” and dichotomized into “always” and “not always.”

Condom use at last anal sex was assessed by asking participants: “Was a condom used the last time that you had anal sex with a man?” with response options “yes” vs. “no.” To assess PrEP awareness, participants were asked: “Have you heard of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention?” with response options “yes” vs. “no.”

Healthcare Access

Participants were asked whether or not they had a current primary care provider, health insurance, and whether they had been unable to access healthcare in the last year due to costs. Responses to all questions were “yes”/“no.”

Mental Health and Minority Stress

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Eaton, Smith, Ybarra, Muntaner, & Tien, 2004), a 20-item scale used to screen for clinically significant depressive symptoms (α = 0.93 in the present study). The items were scored on a 4-point scale from 0 to 3, with a higher score indicating more severe depressive symptoms. Scores were summed, responses were dichotomized into depressive symptoms (16 or higher) and no depressive symptoms (15 or lower).

Suicidal ideation was assessed by asking participants: “Have you ever thought about ending your life or committing suicide?” with response options “yes” vs. “no.” Previous suicide attempt was assessed by asking participants: “Have you ever attempted to end your life?” with response options “yes” vs. “no.” Participants who endorsed suicidal ideation and/or previous suicide attempt were counselled by a physician and provided resources on mental health services.

Perceived social support was assessed using the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) (Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, & Farley, 1988), a 12-item validated scale to measure perceived social support from family, friends, and significant other (α = 0.86 in the present study). Each of the items are scored on a 7-point Likert scale. Scores were summed, and higher scores indicated greater perceived social support.

Anxiety was assessed using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale (Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, & Löwe, 2006), a 7-item validated scale that measures recent symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder scored on a 4-point Likert scale (α = 0.82 in the present study). Scores were summed and higher scores indicated greater anxiety.

Community connectedness, identity concealment and rejection anticipation were assessed using the LGBT Minority Stress Measure (Outland, 2016), a 50-item validated scale to measure minority stress experiences among LGBT individuals. The community connectedness subscale (α = 0.86 in the present study) contained five items which were each scored on a 5-point Likert scale with a higher score indicating higher levels of community connectedness. The identity concealment subscale (α = 0.86 in the present study) contained four items which were each scored on a 5-point Likert scale with a higher score indicating higher levels of identity concealment. The rejection anticipation subscale (α = 0.72 in the present study) contained four items which were scored on a 5-point Likert scale with a higher score indicating higher levels of rejection anticipation.

Substance Use

Participants were asked about their alcohol and drug use. Hazardous drinking was assessed with the AUDIT-C (Bush, Kivlahan, McDonell, Fihn, & Bradley, 1998), a 3-item screening for heavy drinking or alcohol dependence. The AUDIT-C was scored on a scale of 0–12; a score of 4 or greater indicated hazardous drinking. History of polysubstance use was assessed by asking participants if they had ever used any of the following recreational drugs in their lifetime: tramadol, codeine, street opioids and prescription opioids, poppers (alkyl nitrites), cocaine, prescription stimulants (Ritalin, Concerta, Dexedrine, Adderall, or diet pills), methamphetamines, inhalants, hallucinogens, Rohypnol (flunitrazepam) and sedative/sleeping pills. Responses were categorized into 0, 1, 2–3, and 4 + (number of drugs ever used). Recent polysubstance use was assessed by asking participants how often had ever used any of the following recreational drugs in the last 3 months: tramadol, codeine, street opioids and prescription opioids, poppers (alkyl nitrites), cocaine, prescription stimulants (Ritalin, Concerta, Dexedrine, Adderall, or diet pills), methamphetamines, inhalants, hallucinogens, Rohypnol (flunitrazepam) and sedative/sleeping pills. Responses were categorized into none, once or twice and monthly or more.

Geosocial Networking App Usage

To assess frequency of GSN apps usage, we asked participants: “Have you used a website or mobile app to find male partners for sexual activity in the last 3 months? If yes, how often?” Responses were categorized into “No GSN apps usage,” “Several times a week or less,” and “Once a day or more.” To assess types of GSN apps being utilized, we asked participants: “Which websites/mobile apps do you use to meet partners for casual sex?” Participants were could select multiple apps.

The categorization cutoffs for all continuous variables were decided based on categorization in past studies and the distribution of data in our sample (minimizing low counts in cells while also making sure cutoffs are logical and easily interpretable).

Data Analysis

We assessed the distribution (percentages and means) of all variables by GSN apps usage. Chi-square global tests of independence were used to assess independent associations between variables. Bivariate and multivariable ordinal logistic regression models (assuming proportional odds) were constructed to examine the relationship between GSN apps usage and other health-related factors. Variables that were significant at p < .05 in the bivariate models were retained in the multivariable model assessing these outcomes. Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

Sample Demographics

Sample demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. The average age was 29.2 years (SD = 5.8; range, 18–60), majority (60%) identified as bisexual, and 63% were single. Most (61%) of the participants reported experiencing high financial hardship, and 22% reported a history of incarceration. About a quarter (24%) screened positive for depressive symptoms, 21% had a history of suicidal thoughts and 10% self-reported suicide attempts in the past. More than a third (38%) of the sample reported living with HIV and almost one-third (32%) reported an STI diagnosis in the last year.

Geosocial Networking App Usage

Almost half (48%) of participants reported no use of GSN apps to find male partners for sexual activity in the previous 3 months, 28% reported using GSN apps several times a week or less, and 24% reported using GSN apps once a day or more. The most commonly used GSN app was Facebook (30.9%), followed by Grindr (20.5%), and Badoo (11.3%).

In the bivariate analysis (Table 2), demographic and sexual risk factors associated with increased odds of higher frequency of GSN apps usage included: being single [odds ratio (OR) 1.56; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.06 to 2.29], having a university degree or higher (OR 2.51; 95% CI: 1.59 to 3.95), reporting living with HIV (OR 1.67; 95% CI: 1.15 to 2.44), having 4–5 receptive anal sexual acts (OR 2.32; 95% CI: 1.31 to 4.11) and 6 or more receptive anal sex acts (OR 3.44; 95% CI: 1.70 to 6.99) in the previous 3 months compared to none, reporting condom use at last anal sex (OR 1.71; 95% CI: 1.08 to 2.72) compared to reporting not using a condom, being aware of PrEP (OR 3.14; 95% CI: 2.13 to 4.64). In terms of healthcare access and mental health, having a primary care provider (OR 1.57; 95% CI: 1.09 to 2.28), reporting suicidal ideation (OR 2.10; 95% CI: 1.34 to 3.28), reporting moderate anxiety (OR 1.66; 95% CI 1.10 to 2.48) and moderately severe/severe anxiety (OR 1.83; 95% CI: 1.05 to 3.20) compared to mild anxiety, and higher levels of identity concealment (OR 1.07; 95% CI: 1.03 to 1.11) were associated with increased odds of higher frequency of GSN apps usage. Residing in Plateau state, compared to Abuja (OR 0.57; 95% CI: 0.33 to 0.99) and identifying as Muslim (OR 0.49; 95% 0.32 to 0.76) compared to Christian, was associated with decreased odds of higher frequency of GSN apps usage. Substance use was not significantly associated with GSN apps usage.

In the multivariable model (Table 2), factors significantly associated with increased odds of higher frequency of GSN apps usage included: being single [adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 1.62; 95% CI: 1.04 to 2.51] compared to not being single, having a university degree or higher (aOR 1.81; 95% CI: 1.07 to 3.07) compared to senior secondary school or lower, having 4–5 receptive anal sexual acts (aOR 2.32; 95% CI: 1.23 to 4.40) and 6 or more receptive anal sex acts (aOR 3.18; 95% CI: 1.42 to 7.12) in the previous 3 months compared to none, being aware of PrEP (aOR 2.58; 95% CI: 1.54 to 4.33), having a primary care provider (aOR 1.62; 95% CI: 1.06 to 2.46), and higher levels of identity concealment (aOR 1.09; 95% CI: 1.04 to 1.14).

Discussion

This study examined the frequency of GSN apps usage and its association with demographic and psychosocial factors in a multisite sample of community-recruited GBMSM in Nigeria. To our knowledge, this is only the second study to explore frequency and predictors of GSN apps usage among Nigerian GBMSM, thus contributing to the growing body of research on this topic in the region. We found that usage of GSN apps was common, with more than half of participants (53%) reporting using GSN apps to meet sexual partners in the previous 3 months. This prevalence is similar to a similar study among Nigerian GBMSM that found 62% of participants met male sexual partners online (Stahlman et al., 2017). This suggests that GSN apps usage is popular among Nigerian GBMSM and this medium may be an effective tool to disseminate health-related information to this population.

We found that participants who had a college degree or higher, and those who reported having a primary care provider were more likely to report greater GSN apps usage. Having a college degree and access to healthcare services might be indicative of having higher socioeconomic status (SES), which may also be related to increased access to mobile technology and internet services. Therefore, while GSN apps might be an effective mechanism to reach Nigerian GBMSM of higher SES, it might overlook an economically disadvantaged and far more vulnerable population that may be unable to afford a smartphone and mobile data. While previous studies have demonstrated that GSN apps can be utilized to promote better sexual health practices among GBMSM (Fields et al., 2020; Kirby & Thornber-Dunwell, 2014; Levy et al., 2015), it is important to be aware of the subpopulations that may be missed through interventions and programs disseminated through these platforms.

Previous research has linked GSN apps usage with HIV sexual risk taking among GBMSM populations, specifically higher number of sexual partners, condomless anal sex, and prevalence of being diagnosed with STIs (Lehmiller & Ioerger, 2014; Phillips et al., 2014; Rice et al., 2012). Similarly, we found that being single and reporting increasing number of receptive anal sex acts in the past month was associated with greater use of GSN apps. However, we also found that condomless anal sex and diagnosis of STIs were not significantly associated with GSN apps usage to meet sexual partners. This finding may be due to the limited scope of questions we utilized to assess condomless sex. Additionally, several studies that have investigated—with mixed findings—whether online sex seeking facilitate sexual risk taking among GBMSM or whether these mediums attract more people who are already engaged in riskier sexual practices (Jenness et al., 2010; Liau, Millett, & Marks, 2006). More studies are needed to elucidate this relationship, especially among GBMSM in the African setting where GSN apps usage is highly prevalent. We found that individuals who utilized GSN apps to meet sexual partners were three times more likely to be aware about PrEP for HIV prevention, compared to individuals who did not use GSN apps. This suggests that there may be a compensatory mechanism where participants who are engaged in riskier sexual practices are also more aware of newer HIV prevention approaches and have increased access to a primary care provider. It is also possible that GSN apps users may be more likely to be aware of PrEP, as it is sometimes advertised on GSN apps commonly utilized by GBMSM.

A majority of the sample reported using GSN apps in the previous three months and those who used such apps were substantially more likely to be aware of PrEP. More research is needed to investigate whether GSN apps could be an effective medium for the dissemination of health-related information and engaging in health education, specifically related to HIV prevention and care services, especially since GBMSM are highly stigmatized in Nigeria. For example, this medium can be leveraged to disseminate information related to HIV PrEP, which has been shown to be highly acceptable among GBMSM in West and East Africa but knowledge about PrEP remains relatively low (Ogunbajo et al., 2019a, b, 2020a). Past studies have found that GSN apps are highly acceptable for the dissemination of health information, increasing HIV testing, and linkage to HIV care among GBMSM (Chow & Klausner, 2018; Czarny & Broaddus, 2017; Patel et al., 2017). Another study found that GBMSM were highly acceptable to finding LGBT-friendly healthcare providers, receiving lab test results, and chatting with a healthcare provider on GSN apps (Ventuneac, John, Whitfield, Mustanski, & Parsons, 2018). Utilizing GSN apps, might help bypass barriers—such as stigma and discrimination—to learning about sexual and other health services, while still maintaining some level of anonymity and safety compared to seeking this information at a traditional physical location (e.g., clinic, hospital, community-based organization). This is even more important as sexual minority identity concealment was associated with greater GSN app usage in our sample. It is important that community-based organizations and healthcare systems that serve GBMSM leverage GSN apps as a medium to promote a range of sexual health services available to this group, which might help facilitate increase in health seeking behaviors and lead to more visits to their physical locations.

In the bivariate analysis, we found that some mental health outcomes (suicidal ideation and anxiety) were associated with greater use of GSN apps but those associations became statistically insignificant in the multivariable model. This finding suggests that mental health problems might not be sufficient to explain the relationship between GSN apps usage and HIV sexual risk practices. It is plausible that GSN apps usage may be utilized as a coping strategy to deal with mental health problems that might proliferate from feelings of social isolation in a highly homophobic country such as Nigeria. These preliminary findings suggest the need for more research to elucidate the possible pathways through which mental health impacts GSN app usage and ultimately sexual risk taking among Nigerian GBMSM. Additionally, we found a high prevalence of depressive symptoms, anxiety, and suicidal ideation, which is similar to other studies among Nigerian GBMSM (Oginni et al., 2020; Ogunbajo et al., 2020b) Consequently, there is a need for mental health services and providers that are both affirming of GBMSM communities and can provide competent and nonjudgmental services to this vulnerable group.

Limitations

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of some study limitations. The cross-sectional nature of our study design limits our ability to draw conclusions about causal inference. Additionally, participants were recruited through CBOs that serve GBMSM and social networks of this group, thereby limiting the generalizability of the results, especially considering GBMSM who are not connected to the CBOs or are outside of these social networks. In addition, many of the measures were self-reported, which may have been influenced by interviewer bias. Future studies should use more objective measurements when possible.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, this study represents one of the few that has examined the role of GSN apps is associated with psychosocial health among Nigerian GBMSM. Our findings support a handful of studies that have also called for the need to develop and implement sexual health interventions and programs that target GBMSM in Africa through GSN apps (Stahlman et al., 2015, 2017).

References

Altan, K. B. (2019). Problematic versus non-problematic location-based dating app use: Exploring the psychosocial impact of grindr use patterns among gay and bisexual men. https://uhra.herts.ac.uk/handle/2299/22527

Balogun, A., Bissell, P., & Saddiq, M. (2020). Negotiating access to the Nigerian healthcare system: The experiences of HIV-positive men who have sex with men. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 22, 223–246.

Beyrer, C., Baral, S. D., Van Griensven, F., Goodreau, S. M., Chariyalertsak, S., Wirtz, A. L., & Brookmeyer, R. (2012). Global epidemiology of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. The Lancet, 380(9839), 367–377.

Bush, K., Kivlahan, D. R., McDonell, M. B., Fihn, S. D., & Bradley, K. A. (1998). The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): An effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Archives of Internal Medicine, 158(16), 1789–1795.

Chow, J. Y., & Klausner, J. D. (2018). Use of geosocial networking applications to reach men who have sex with men: Progress and opportunities for improvement. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 94(6), 396–397.

Czarny, H. N., & Broaddus, M. R. (2017). Acceptability of HIV prevention information delivered through established geosocial networking mobile applications to men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior, 21(11), 3122–3128.

Eaton, W. W., Smith, C., Ybarra, M., Muntaner, C., & Tien, A. (2004). Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: Review and Revision (CESD and CESD-R). In M. E. Maruish (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment: Instruments for adults (pp. 363–377). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Eluwa, G. I., Adebajo, S. B., Eluwa, T., Ogbanufe, O., Ilesanmi, O., & Nzelu, C. (2019). Rising HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men in Nigeria: A trend analysis. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1201.

Emmanuel, G., Folayan, M. O., Ochonye, B., Umoh, P., Wasiu, B., Nkom, M., … Anenih, J. (2019). HIV sexual risk behavior and preferred HIV prevention service outlet by men who have sex with men in Nigeria. BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), 261.

Fields, E. L., Long, A., Dangerfield, D. T., Morgan, A., Uzzi, M., Arrington-Sanders, R., & Jennings, J. M. (2020). There’s an app for that: Using geosocial networking apps to access young Black gay, bisexual, and other MSM at risk for HIV. American Journal of Health Promotion, 34(1), 42–51.

Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Dovidio, J. (2009). How does stigma “get under the skin”? The mediating role of emotion regulation. Psychological Science, 20(10), 1282–1289.

Holloway, I. W., Pulsipher, C. A., Gibbs, J., Barman-Adhikari, A., & Rice, E. (2015). Network influences on the sexual risk behaviors of gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men using geosocial networking applications. AIDS and Behavior, 19(2), 112–122.

Jenness, S. M., Neaigus, A., Hagan, H., Wendel, T., Gelpi-Acosta, C., & Murrill, C. S. (2010). Reconsidering the internet as an HIV/STD risk for men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior, 14(6), 1353–1361.

Kirby, T., & Thornber-Dunwell, M. (2014). Phone apps could help promote sexual health in MSM. The Lancet, 384(9952), 1415.

Lehmiller, J. J., & Ioerger, M. (2014). Social networking smartphone applications and sexual health outcomes among men who have sex with men. PloS ONE, 9(1), e86603.

Levy, M. E., Watson, C. C., Wilton, L., Criss, V., Kuo, I., Glick, S. N., … Magnus, M. (2015). Acceptability of a mobile smartphone application intervention to improve access to HIV prevention and care services for black men who have sex with men in the District of Columbia. Digital Culture & Education, 7(2), 169–191.

Liau, A., Millett, G., & Marks, G. (2006). Meta-analytic examination of online sex-seeking and sexual risk behavior among men who have sex with men. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 33(9), 576–584.

Oginni, O. A., Mapayi, B. M., Afolabi, O. T., Ebuenyi, I. D., Akinsulore, A., & Mosaku, K. S. (2019). Association between risky sexual behavior and a psychosocial syndemic among Nigerian men who have sex with men. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 23(2), 168–185.

Oginni, O. A., Mapayi, B. M., Afolabi, O. T., Obiajunwa, C., & Oloniniyi, I. O. (2020). Internalized homophobia, coping, and quality of life among Nigerian gay and bisexual men. Journal of Homosexuality, 67, 1447–1470.

Oginni, O. A., Mosaku, K. S., Mapayi, B. M., Akinsulore, A., & Afolabi, T. O. (2018). Depression and associated factors among gay and heterosexual male university students in Nigeria. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(4), 1119–1132.

Ogunbajo, A., Iwuagwu, S., Williams, R., Biello, K., & Mimiaga, M. J. (2019a). Awareness, willingness to use, and history of HIV PrEP use among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in Nigeria. PloS ONE, 14(12), e0226384.

Ogunbajo, A., Kang, A., Shangani, S., Wade, R. M., Onyango, D. P., Odero, W. W., & Harper, G. W. (2019b). Awareness and acceptability of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) in Kenya. AIDS Care, 31, 1185–1192.

Ogunbajo, A., Leblanc, N. M., Kushwaha, S., Boakye, F., Hanson, S., Smith, M. D., & Nelson, L. E. (2020a). Knowledge and acceptability of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Ghana. AIDS Care, 32, 330–336.

Ogunbajo, A., Oke, T., Jin, H., Rashidi, W., Iwuagwu, S., Harper, G. W., Biello, K. B., & Mimiaga, M. J. (2020b). A syndemic of psychosocial health problems is associated with increased HIV sexual risk among Nigerian gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM). AIDS Care, 32, 337–342.

Outland, P. L. (2016). Developing the LGBT minority stress measure. Colorado State University. Libraries.

Patel, R. R., Harrison, L. C., Patel, V. V., Chan, P. A., Mayer, K. H., Reno, H. E., & Manning, T. (2017). HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis programs incorporating social applications can reach at-risk men who have sex with men for successful linkage to care in Missouri, USA. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 28(3), 428–430.

Phillips, G., Magnus, M., Kuo, I., Rawls, A., Peterson, J., Jia, Y., … Greenberg, A. E. (2014). Use of geosocial networking (GSN) mobile phone applications to find men for sex by men who have sex with men (MSM) in Washington, DC. AIDS and Behavior, 18(9), 1630–1637.

Rice, E., Holloway, I., Winetrobe, H., Rhoades, H., Barman-Adhikari, A., Gibbs, J., et al. (2012). Sex risk among young men who have sex with men who use Grindr, a smartphone geosocial networking application. Journal of AIDS and Clinical Research, 84(Suppl. 4), 1–6.

Schwartz, S. R., Nowak, R. G., Orazulike, I., Keshinro, B., Ake, J., Kennedy, S., … Baral, S. D. (2015). The immediate effect of the Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Act on stigma, discrimination, and engagement on HIV prevention and treatment services in men who have sex with men in Nigeria: Analysis of prospective data from the TRUST cohort. The Lancet HIV, 2(7), e299–e306.

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097.

Stahlman, S., Grosso, A., Ketende, S., Mothopeng, T., Taruberekera, N., Nkonyana, J., … Baral, S. (2015). Characteristics of men who have sex with men in southern Africa who seek sex online: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(5), e129.

Stahlman, S., Nowak, R. G., Liu, H., Crowell, T. A., Ketende, S., Blattner, W. A., … Meena, T. R. S. (2017). Online sex-seeking among men who have sex with men in Nigeria: Implications for online intervention. AIDS and Behavior, 21(11), 3068–3077.

Tucker-Seeley, R. D., Mitchell, J. A., Shires, D. A., & Modlin, C. S., Jr. (2015). Financial hardship, unmet medical need, and health self-efficacy among African American men. Health Education & Behavior, 42(3), 285–292.

Ventuneac, A., John, S. A., Whitfield, T. H., Mustanski, B., & Parsons, J. T. (2018). Preferences for sexual health smartphone app features among gay and bisexual men. AIDS and Behavior, 22(10), 3384–3394.

Wang, H., Zhang, L., Zhou, Y., Wang, K., Zhang, X., Wu, J., & Wang, G. (2018). The use of geosocial networking smartphone applications and the risk of sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1178.

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41.

Zou, H., & Fan, S. (2017). Characteristics of men who have sex with men who use smartphone geosocial networking applications and implications for HIV interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(4), 885–894.

Acknowledgments

We will like to thank all the participants of the study for their time and efforts. We would also like to thank the staff at Centre for Right to Health (Abuja) Equality Triangle Initiative (Delta), Improved Sexual Health and Rights Advocacy Initiative (ISHRAI, Lagos) and Hope Alive Health Awareness Initiative (Plateau). We also extend our gratitude to Olubiyi Oludipe (ISHRAI), Bala Mohammed Salisu (Hope Alive Health Awareness Initiative), Chucks Onuoha, Prince Bethel, Eke Chukwudi, Tochukwu Okereke, Josiah Djagvidi, Victor Brownson, and Odi Iorfa Agev, for providing logistical support to the project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

This study was supported by a R36 dissertation grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse [DA047216] (principal investigator [PI]: Adedotun Ogunbajo) and by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health Policy Research Scholars Program, for which the first author is a scholar but the foundation did not provide direct project support.

Ethics Approval

The study protocols were approved by the institutional review boards at Brown University and the Nigerian Institute of Medical Research.

Consent to Participate

Each participant provided verbal informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ogunbajo, A., Lodge, W., Restar, A.J. et al. Correlates of Geosocial Networking Applications (GSN Apps) Usage among Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men in Nigeria, Africa. Arch Sex Behav 50, 2981–2993 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01889-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01889-3