Abstract

The existence of a strong link between socio-economic background and individual preferences has been documented among both children and grown-ups. Here, we study whether such a correlation persists even in a highly homogeneous population of young adults: university students. Our findings indicate that participants living in an area characterized by a high socio-economic environment tend to trust more and are more inclined to reciprocate higher levels of trust, as compared to those coming from less wealthy neighborhoods. This behavioral difference is, at least in part, driven by heterogeneities in beliefs: subjects from the most affluent part of the city have more optimistic expectations on their counterpart’s trustworthiness than those living in a lower socio-economic environment. By contrast, no significant differences emerge in other preferences: generosity, risk attitudes, and time preferences. Finally, we do not find any systematic evidence of out-group discrimination based on neighborhood identity.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Inequality has been increasing steadily in industrialized societies over the last decades, and this has been recognized as one of the main societal challenges (OECD 2011). Cities have grown divided, to the extent that household income inequality measured at the city level may be even larger than inequality at the country level.Footnote 1 Thus, affluent and extremely poor districts often coexist next to one another, divided only by an invisible line.

Here, we study how being socialized in a more or less wealthy area of the same metropolitan city correlates with residents’ preferences in strategic and non-strategic situations. This is informed by the recent empirical literature on neighborhoods effects, showing that childhood exposure to different environments has a long-term effect on earnings, college attendance, fertility, and marriage patterns (Chetty et al. 2016).

In an online study, we exploit the existing differences in socio-economic status (SES) between areas of an Italian city. In particular, we recruit participants who reside in different areas of the same city and we ask them to participate in a Trust Game and a Dictator Game, and we elicit their time and risk preferences by means of standard, incentive compatible procedures. Our main goal is to test if the preferences of participants from high and low SES areas display systematically different patterns. Furthermore, we want to test whether participants discriminate by conditioning their behavior on the socio-economic background of their counterpart.

A link between socio-economic status (of the participant or of the family) and preferences has been documented in a few recent studies. Using the General Social Survey (GSS) from the US, Alesina and La Ferrara (2002) show that being economically unsuccessful in terms of income is associated with low level of trust. In a survey conducted in Sweden, respondents in the bottom half of the income distribution report a significantly lower level of generalized trust with respect to those at the top (Gustavsson and Jordahl 2008). This result is also confirmed in Butler et al. (2016) who look at the European context more broadly, using both the European Social Survey and the SOM Survey, finding that people with low levels of trust have significantly lower income than those with intermediate levels of trust. Finally, Ananyev and Guriev (2019) look at the case of Russia and using the survey data from the Public Opinion Foundation (Fond Obschestvennogo Mneniya, or FOM), they show that a 10% decrease in income is associated with a five-percentage point decrease in social trust.

The correlation between wealth and generosity, instead, is still debated (Piff et al. 2010; Andreoni et al. 2021). A small but growing literature has documented that family socio-economic characteristics correlate with children’s risk attitudes, impatience, self-control, and social preferences (Castillo et al. 2011; Delaney and Doyle 2012; Bauer et al. 2014; Kosse et al. 2020).

Differences along these dimensions may have important economic consequences, since these traits have been shown to have a long-term effect on a wide variety of life outcomes. Longitudinal studies for example show that children’s ability to postpone a gratification is a good predictor of important life-long outcomes, ranging from educational attainments (Mischel et al. 1989), to labor outcomes and lifetime income (Golsteyn et al. 2014), to health conditions, substance dependence, personal finances, up to criminal behavior (Moffitt et al. 2011). Sutter et al. (2013) confirm that an association exists between children’s and adolescents’ impatience and their consumption of alcohol and cigarettes, their body mass index, their saving behavior, and their school conduct. Prosociality also correlates with labor market success, in a large-scale cross-country study (Kosse and Tincani 2020), while a field intervention promoting children’s non-cognitive skills proved to foster trust among the treated sample and improved their education achievements, as well as other outcomes in early adulthood such as criminality and employment (Algan et al. 2014).

A peculiarity of our experiment is that our subject pool is composed of well-educated young adults, who are currently enrolled in the university or have just completed their studies. Most of our participants still live with their family. This is an appealing feature of our sample, as it excludes any possibility of self-selection into a given area. While the parents of our participants made a conscious choice in terms of housing—driven by income, preferences, convenience, etc.—it is safe to assume that their children had little or no saying in this decision. Moreover, our subject pool is remarkably homogeneous in terms of education, ethnicity, and religion; dimensions that could affect cooperative behavior and preferences in general (Fershtman and Gneezy 2001; Koopmans and Veit 2014; Weng and Yang 2014; Chakravarty et al. 2016; Chuah et al. 2016). Since the majority of our sample is composed of college students, it is also likely that our participants have been exposed to daily interactions with peers from different backgrounds for years. While we do not make any causal claim based on our data, we believe that any difference in preferences and beliefs between participants from areas with different SES would provide some support in favor of the long-lasting effects of environmental conditions and socialization.

Furthermore, experimental economists are increasingly using laboratory experiments to measure the importance of the recipient’s identity in cooperation and coordination games.Footnote 2 Our study adds to this strand of the literature by additionally testing whether participants’ behavior in the Trust and the Dictator Game depends on the signal they receive on the socio-economic background of their counterpart.

We build on the design developed by Falk and Zehnder (2013), who ran a large experiment involving a random sample of the adult residents of Zurich, and found evidence that trustor condition their behavior on the trustee’s district of residence.Footnote 3 Differently from Falk and Zehnder (2013), however, we focus more on differences in senders’ behavior depending on their own socio-economic background, rather than on the recipients’. Our main goal is to verify if participants from low SES areas are less likely to show preferences and beliefs that are conducive to cooperation—in general or specifically when they face counterparts from wealthier neighborhoods—hence potentially missing opportunities for their development and bolstering poverty and social fragmentation. As the area of residence is an observable characteristic that might affect behavior and interpersonal interactions in the “real world,” providing this information to subjects may strengthen the external validity of our results. Hence, both in the Trust and in the Dictator Game, we provide participants with information on their counterpart’s area of residence, which may be perceived as a signal of socio-economic status.

We report three main results. First, participants from the high SES area trust more are more trustworthy, and expect more trustworthiness than their peers from the low SES area. No significant differences emerge in decision tasks that do not imply any strategic interaction, through which we measure generosity, risk attitudes, and time preferences. Second, we find that most of the heterogeneity in trust behavior between the two areas is explained by beliefs about trustworthiness. We also find support for the consensus effect in explaining the belief formation process. Finally, we do not find any evidence of systematic out-group discrimination. Participants do not change their behavior in the Trust and Dictator Game if they are matched with someone from their same area of residence or a different one.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the experimental location, the subject pool, and the design of the online experiment. Section 3 reports the main results of the paper and the conclusion is drawn in Sect. 4.

2 Subject pool and experimental design

In this section, we start by describing the location where the experiment took place, and the subject pool. We then detail the experimental design and the procedures.

2.1 Location and subject pool

All participants in the study were born in the metropolitan area of Bologna, a medium-size city located in the North of Italy. The municipality of Bologna has a population of about 380,000 inhabitants, while the metropolitan area includes about 1 million inhabitants. We recruited participants from the municipality of Bologna, both from the inner center—which was divided into nine districts at the time of the experiment—and the hinterland (Fig. 1).

Income distribution in Bologna. The low SES area (North) includes: Borgo Panigale, Navile, San Donato, and Reno. The High SES area (South) includes: Porto, San Vitale, Savena, Saragozza, and Santo Stefano. The heat map shows the average income for the year 2014 expressed in Euro

While the focus of the paper is mainly on the nine districts of the central area of Bologna, we also recruited people from the hinterland to make the purpose of the experiment less transparent. No formal borders are present across the districts within the municipality, but a clear socio-economic division exists between the Northern and Southern areas (see Table 1 and Fig. 1). The divide emerges along many important dimensions. First and foremost, the average income is 25% lower in the Northern as compared to the Southern area. This is a quite sizable difference, especially if one considers that Bologna is a medium-size municipality. Another important dimension to assess the socio-economic environment is the education level. The incidence of residents with at least a bachelor degree goes from 43% in the Northern area to 61% in the Southern area. Moreover, the Northern area is characterized by a higher degree of multiculturalism and by a slightly lower political participation (measured by the turnout in the 2016 national constitutional referendum). The latter difference emerges even in the local municipal elections (Bellettini et al. 2016).Footnote 4 Throughout the paper, we will refer to the North area as the low SES area and to the South area as the high SES one.

The division between the two areas reflects a rooted sentiment among the local population. Especially among teenagers and adolescents, rather, unflattering nicknames for the two areas are commonly used. While the level of social tension is fairly low, it is important to stress that the division and the boundaries of the two areas are commonly perceived and understood by the local population.Footnote 5

The subject pool We recruited participants born in the metropolitan area of Bologna via ORSEE (Greiner 2015). We were able to screen subjects based on the information available in our database, so no reference to the subjects’ origins was made in the recruitment message.

Table 6 shows that about one-third of participants live in the hinterland, outside the municipality of Bologna. The hinterland of the metropolitan area of Bologna is quite heterogeneous. The average income ranges between 19,386€ and 28,111€Footnote 6, and the fraction of foreigners over the total population ranges between 5.6 and 15.2%.Footnote 7 We decided not to exclude these subjects from our sample, because on one hand, their presence makes the purpose of the experiment less transparent to participants, hence reducing a potential demand effect, and on the other hand, they represent an interesting benchmark for comparison.Footnote 8

A few considerations about the composition of our sample are in order. First, participants from the three areas—low SES, High SES, and Hinterland—do not differ in terms of age, gender, and education level (Table 6 in Appendix A). This is not surprising, since we mostly draw from the student population of the University of Bologna. Second, we focus on the impact of having spent the early years of life in areas with different socio-economic characteristics. Our participants, however, are mostly university students (80%)—this share increases to 94% if we include recent graduates (subjects with a bachelor degree and an age below 30)—and do not fully reflect the same differences in terms of SES observed at the population level. To better understand the composition of our sample, we have conducted an additional survey some time after our main experiment on a (partly) new sample (see Sect. A.2 of the Appendix for further details). The results from this complementary survey (Table 10 in the Appendix) indicate that our sample is indeed very homogeneous along many relevant dimensions—i.e., parental education and home possession.

We also have information about the place of residence at the time of birth, on whether or not the participants live with their parents, and about the area of residence of their best friend. Only 35 (out of a total of 144) participants moved across areas, and those who moved were mostly from the Hinterland (\(N =14\)). Importantly, only less than 7% of participants moved from the Low to the High SES (\(N = 5\)) or vice versa (\(N = 5\)). The lowest level of mobility is observed among participants living in the low SES area. A substantial portion of our participants (77%) still live with their parents, and the figures are similar across areas.Footnote 9 We also have information about the area where their best friend lives. One-third of the participants from the low SES have a best friend living in the high SES, while this number increases to 45% for participants from high SES. This evidence can be understood as an additional sign that our subject pool is quite homogeneous and socialized.

2.2 Experimental design

The experiment consists of four games presented in a fixed order: (i) Trust Game; (ii) Dictator Game; (iii) time preferences task; and (iv) risk preferences task. Below, we describe in detail how we implemented each of these games.

Trust Game To capture trust and trustworthiness, we used a variation of the Trust Game developed by Berg et al. (1995). Participants were divided into pairs comprising one trustor and one trustee. Trustors were endowed with 5€ that had to be divided between themselves and the trustee. Any amount sent to the trustee was tripled, and the trustees could decide how much of the tripled amount to keep for themselves and how much to return to the trustor. A self-interested rational player should send back nothing while playing as a trustee and, by backward induction, a trustor should keep the entire endowment. However, efficiency is maximized when the trustor sends the entire endowment to the trustee.

The amount sent by the trustor to the trustee is commonly understood as a proxy for trust, while the amount sent back by the trustee is a proxy for trustworthiness.Footnote 10 We used the role reversal and the strategy method. That means that all players played in both roles—first as trustors and then as trustees; at the end of the experiment, pairs were randomly formed and roles were randomly assigned. Only the decisions made in the role assigned ex-post were implemented. Moreover, while deciding as trustees, players had to make a decision for each possible amount sent by the trustor. To avoid any carry-over effect or hedging problem, partners and roles were randomly assigned, and feedback was provided only at the end of the experiment. After making their decisions as trustor and trustee, subjects were also asked to state their beliefs about the trustworthiness level of their counterpart. We asked what percentage of the tripled amount they expected to be sent back from the trustee, in intervals of 10 percentage points.Footnote 11

Dictator Game To measure the generosity level of our subjects, we used the Dictator Game (Kahneman et al. 1986). Participants were divided into pairs comprising one dictator and one recipient. We informed subjects that the opponent for this game would not necessarily be the same as the one in the Trust Game. Dictators were endowed with 10€ and had to decide how much to keep for themselves and how much to give to the recipient, who had no decision to make. A self-interested dictator should keep the entire endowment, while positive transfers are interpreted as a proxy for generosity. Here, as in the Trust Game, we used the role-reversal; all players were asked to make a decision as dictators. Roles were assigned and revealed at the end of the experiment.

Time preferences After the Dictator Game, we elicited time preferences through a Multiple Price List (Andersen et al. 2008). Each subject had to make 10 choices between two options. Option A paid 100€ 1 week after the end of the experiment, while Option B paid a larger amount 1 week and 3 months after the end of the experiment. While the amount paid by Option A was the same in all decisions, the amount paid by Option B increased in steps of 3€ from one decision to the other and ranged from 103€ (decision 1) to 130€ (decision 10, see the Instructions in Appendix B). The switching point from Option A to Option B is our proxy for time preferences. The later the subjects switch from A to B, the more impatient they are. 7 participants (1 in 20) were randomly selected for payment for this part, and the relevant decision was also drawn at random by the computer. Payments for this task were carried out via bank transfer on the selected date.

Risk preferences Finally, we elicited risk preferences by means of the “Bomb Risk Elicitation Task” developed by Crosetto and Filippin (2013). Subjects were presented with a \( 5\times 5 \) table containing 25 cells. Every 2 s, a cell was automatically activated and colored in red. The earnings increased linearly with the number of activated cells; more precisely, any activated cell yielded 50 cents. However, behind one of the 25 cells, there was a “bomb”; if that cell was activated, all the earnings for this task vanished. Subjects had to decide when to stop activating new cells. The position of the “bomb” was revealed only at the end of the experiment. In this task, subjects faced a trade-off between the amount of money they could make and the risk of activating the cell containing the “bomb”. The number of cells activated by a subject is negatively correlated with his or her degree of risk aversion.

Treatments We had three between-subject treatments in which we varied the area of residence of the opponent—low SES, High SES, or Hinterland.Footnote 12 The treatments applied only to the first two games—Trust Game and Dictator Game—where another player was involved.

At the beginning of the experiment, before playing the Trust Game, all subjects were asked to answer a short questionnaire where they also had to report the district where they were living at the time of the experiment. To facilitate the task, we also showed a map of the boundaries of the districts (see the Instructions in Appendix B). In the Trust Game and in the Dictator Game, subjects were told that their counterpart was participating in the same study and was from one of the three areas.Footnote 13

To limit any possible demand effect, we did not make any reference to the SES characteristics of the areas, but simply displayed a map with the three areas highlighted in different colors (Fig. 5 in the Appendix). The blue color identified the Low SES area, the green color indicated the High SES area, and the yellow one identified the Hinterland. The area of the counterpart was kept constant across the games, but the counterpart was not necessarily the same from the first to the second game (and this information was explicitly provided to subjects in the instructions).Footnote 14

Experimental procedures The experiment was conducted in May 2016 online using the oTree software (Chen et al. 2016) and subjects were recruited via ORSEE (Greiner 2015). In particular, we restricted the ORSEE subject pool to include only individuals born in the municipality of Bologna. We invited via email all the 296 participants fulfilling the requirement. Subjects were informed that the study itself was online and that they would have to collect their payment at the Bologna Laboratory for Experiments in Social Sciences (BLESS). They could choose from several dates and times to collect the payment and this decision had to be made before starting the study. We also made clear that the participation required to use a PC, a tablet, or a smartphone, and could be carried out from home or any other place with an Internet connection. Moreover, we informed the potential participants that the typical payments ranged from 0€ to 30€, and the completion time was at most 30 min.

Figure 2 illustrates the timeline of the experiment. After registering for the experiment, subjects received a link to access the online experiment and had 1 week to complete the study in all its parts. At the end of the week, all participants who successfully completed the experiment received an email with their earnings and a code to claim their payment. In total, 153 subjects registered for taking part in the study, 145 started the study, and 144 completed it.

After reading the instructions for each part, subjects had to answer few control questions and could not proceed to the game until they answered all the questions correctly. When giving a wrong answer, subjects were provided with some explanation and were required to answer the question again. After having completed the four games, subjects were asked to answer a questionnaire (see Appendix B). No feedback was provided during the experiment: participants received information about the results of each game and earnings via e-mail, at the end of the experiment. Earnings corresponded to the sum of the earnings in all tasks, with the only exception of time preferences for which only one out of every 20 participants was randomly selected for payment.Footnote 15 The average payment was of 17.60€, and payments ranged from 2€ to 138€. Subjects collected their cash payments in a sealed envelope at the BLESS laboratory the date they had selected at the beginning of the study.Footnote 16

3 Results

In this section, we first consider if there is any form of out-group discrimination. We want to test if participants trust more, are more trustworthy, and are more generous when matched with someone from their own area rather than from a different area of residence. We then test if participants living in a high SES area display different preferences compared to the ones from a low SES area. We will focus on situations both with and without strategic interaction. Finally, we study the link between trust, trustworthiness, and beliefs to grasp a better understanding of the origins of the observed differences.

When we talk about high SES and low SES, we refer to the area where the subject was living at the time of the experiment. We have information also about the area of residence at the time the participant was born, and we will use this information to check the robustness of our findings by adding a control for those subjects who moved to a different area. As a further control, we run additional robustness checks by restricting the sample to those participants whose area of residence at the time of the experiment was the same as the one at the time of birth (stayers hereafter).

In the analysis, we consider the following behavioral measures.

-

Trust: defined as the share of the endowment sent to the trustee in the Trust Game;

-

Trustworthiness: we adopt the measure of “reciprocal inclination” proposed by Falk and Zehnder (2013), which is obtained by estimating individual-level OLS regressions where the dependent variable is the amount sent back and the only regressor is the level of trust;Footnote 17

-

Beliefs about trustworthiness: measured by the expected amount returned, as a fraction of the total sum received by the trustee;

-

Generosity: share of the endowment sent to the recipient in the Dictator Game;

-

Risk attitude: share of activated cells in the Bomb Risk Elicitation Task—larger shares are associated to stronger willingness to take risk;

-

Impatience: based on the number of the row, in the Multiple Price List, at which the individual switches from having 100€ today to having a higher amount in the future. The measure goes from 0 (if the respondent always chose the late amount) to 1 (if the respondent always chose the early amount): the higher the number, the higher the impatience level.Footnote 18

3.1 Out-group discrimination across areas

In this section, we test if our participants behave differently when they are matched with someone from their own area of residence or from a different one. We focus on the behavior in the Dictator Game and in the Trust Game—as the other tasks did not involve a counterpart. We do not find any systematic evidence of out-group discrimination. Both in the Trust Game and in the Dictator Game, the behavior and beliefs of subjects who were matched with counterparts residing in their own area were not significantly different from those exhibited by subjects matched with someone from a different area (Table 2 and Fig. 6 in the Appendix).Footnote 19 On average, subjects showed a tendency to reciprocate slightly more toward out-group than in-group members, but this was not true for residents in the low SES area (Fig. 6).

Result 1

We do not find any systematic evidence of out-group discrimination neither in the Trust Game nor in the Dictator Game.

The absence of any significant in-group bias, based on the area of residence of the counterpart, is consistent with the evidence by Blanco and Guerra (2017), who relied on a sample of college students in Colombia. The result is instead at odds with the findings reported by Falk and Zehnder (2013) for a representative sample of the general population. This is not necessarily surprising as we rely on a very different subject pool. Our sample is mostly composed of students who volunteer for experiments and the sense of belonging to the same community might overshade the differences along other dimensions, such as the area of residency.

3.2 SES of the area of residency and preferences

In this section, we pool data across treatments to study if any systematic difference in preferences emerges, depending on the subject’s area of residence. That is, we want to test if participants from a high SES area display preferences and beliefs that are different from those exhibited by participants from a low SES area.

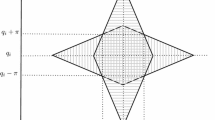

Situations with strategic interaction Figure 3a reports the heat maps for trust, trustworthiness, and beliefs about trustworthiness by neighborhood. It is immediate to see that there is more trust in the high than in the low SES area. A similar pattern is observed for trustworthiness and beliefs.

Table 3 reports the mean value of these three variables by area and summarizes results from non-parametric tests on the distributions. The data confirm that the difference in trust, trustworthiness, and beliefs between the low and the high SES areas are significant (at least at the 10% level) along all three dimensions.

This result is confirmed using formal regression analysis. Models 1–3 in Table 4 provide evidence in support of the correlation between SES and behavior and beliefs in the Trust Game. Model 1 reports ordered logit estimates for trust. The main regressors of interest are high SES, which takes value 1 if the decision-maker is resident in the High SES area and 0 otherwise, and Hinterland that takes value 1 if the decision-maker is resident in the area outside the municipality and 0 otherwise. We also include a dummy for the area of residency of the counterpart (as before, the baseline category is low SES, and we include dummies for High SES and Hinterland). Finally, we control for a number of socio-demographic characteristics and answers to the survey questions (see Notes to Table 4 for further details). The regression analysis suggests that residents of the high SES area trust significantly more than the ones from a low SES area. It is also interesting to notice that none of the dummies for the area of residency of the counterpart is significant. This suggests that not only we fail to observe any out-group discrimination, but none of the areas is discriminated against. To account for the censored nature of our data for trustworthiness (Model 2) and beliefs about trustworthiness (Model 3), we run Tobit regressions. We replicate the same analysis as in Model 1 and obtain similar results also for these variables.Footnote 20 So far, we have considered all participants and have controlled for those who moved from one area to the other. As a further robustness check, we have replicated Table 4 by restricting the sample to those participants who reported to live in the same area where they were born (i.e., stayers). Results for trust and trustworthiness are confirmed also for the sub-sample of stayers. We instead fail to find a significant effect of high SES for beliefs, but the direction of the effect is confirmed.Footnote 21

Figure 4 sheds further light on the difference across areas in terms of trustworthiness, showing that it mainly comes from the fact that the residents in the high SES area tend to reciprocate more higher levels of trust.Footnote 22

Result 2

Participants from the High SES area trust more, are more trustworthy, and expect their counterpart to be more trustworthy as compared to participants from the low SES area.

Situations without strategic interaction We now consider behavior in the Dictator Game, risk aversion, and time preferences. Figure 3b reports the heat maps for generosity, risk, and impatience, and Table 3 reports the mean values of these variables by area. No clear pattern emerges along these dimensions; while there is some variation across neighborhoods, it does not follow the high–low SES division.Footnote 23

More specifically, we fail to find any significant difference between high and low SES areas for generosity level, risk attitude, and patience. Support for these results is provided in Table 9 of the Appendix.Footnote 24

Result 3

In dimensions that do not involve strategic interaction—generosity, risk attitudes, and time preferences—we fail to find significant differences between the preferences of participants from high and low SES areas.

3.3 The determinants of trust

From the previous analysis, we have seen that, even if players do not change their actions based on their counterpart’s area of residence, a significant difference emerges in the trust attitudes between residents living in low and high SES areas. In this section, we try to measure what are the factors explaining this difference.

Trust Previous research has shown that several factors can drive the trustor’s behavior in the Trust Game: individual beliefs about trustworthiness (Gambetta 1988), other-regarding and efficiency concerns (Cox 2004; Ashraf et al. 2006), or individual risk preferences (Schechter 2007). We follow the approach proposed by Sapienza et al. (2013) to better understand what explains the difference in trust levels between residents living in high and low SES areas. To do so, we have to tease apart the two main drivers of trust: beliefs in others’ trustworthiness and individual preferences (generosity, political and social preferences, and risk preferences).

In Model 1 of Table 4, we show that high SES areas are characterized by higher levels of trust. We now build on that model and try to understand if this tendency is driven by beliefs, preferences, and orientations. We proceed by adding to the baseline regression (Model 1, Table 4) preferences and beliefs as measured in the experiment, as well as measures taken from the questionnaire.

In Model 1 of Table 5, we expand the baseline estimation by adding controls that capture elicited preferences—risk attitude, time preferences, and generosity—and beliefs on opponent’s trustworthiness. We find that the most important component in explaining trust are the beliefs. As we have seen in the previous section, the beliefs are correlated with the area of residence of the individual; this explains why when we include this variable into the model, it captures all the impact of the High SES variable. Moreover, notice that our elicited measure of generosity is also a relevant factor in explaining the trust decisions.

In Model 2 of Table 5, we add measures of social and political orientations from the questionnaire (the items are taken from the World Value Survey). Consistently with the previous studies (Glaeser et al. 2000), we do not find any significant relationship between the trust measured with the World Value Survey item and our experimental measure. We do find, instead, that the answer to the question “How much do you think is important to help the people nearby; to care for their well-being?” (Questionnaire Help) is moderately but significantly related to the trustor’s decision in the Trust Game. We believe that this question is capturing some altruistic preferences and indeed, the results in Model 3 of Table 5 seem to support this intuition. Specifically, when we add both the questionnaire measures of social preferences and the incentive compatible measure of generosity, both the significance and the magnitude of Generosity and Questionnaire Help coefficients change due to some collinearity.Footnote 25

Result 4

Beliefs about trustworthiness and generosity are the main drivers of trust. Moreover, a large part of the difference in trust across areas is explained by the beliefs.

We find that the initial amount of trust is strongly correlated with the beliefs about trustworthiness but also with altruistic preferences, especially when experimentally elicited. Moreover, we find that much of the across-areas variation in the residents’ level of trust is captured by the difference in the beliefs between high and low SES residents.Footnote 26 Given that individual beliefs are a strong determinant of the behavior in the Trust Game, we now investigate what drives their formation.

Beliefs In Models 4–6 of Table 5, we use a similar approach to the one we just described for trust behavior. This time, the dependent variable captures the subjects’ beliefs about trustworthiness. As before, we add a first block of variables, including the preferences elicited in the experiment, and a second block with the answers to the questionnaire items. Based on the previous evidence (Butler et al. 2015), we want to test if there is a consensus effect in the belief formation. That is, when thinking about their opponents’ level of trustworthiness, subjects might form their beliefs by putting themselves in the shoes of the other player but by reasoning with their own mind and values. If that is the case, subjects’ beliefs on the other players’ trustworthiness have to be correlated with their own trustworthiness. Model 4 in Table 5 shows indeed that in our sample, there is a strong and positive correlation between trustworthiness and beliefs about others’ trustworthiness. Social and political opinion—as measured in the questionnaire—have only weak predictive power in this case (Model 5). When including both preferences, and questionnaire items (Model 6), we still find strong support for a consensus effect.

All the above results on the determinants of trust hold true if we consider a linear specification or if we restrict the sample to those participants who did not move across areas (i.e., stayers).Footnote 27

Result 5

There is a consensus effect in the beliefs formation: beliefs about trustworthiness are strongly associated with one’s own level of trustworthiness.

4 Conclusions

A recent strand of the literature has documented the existence of a strong link between socio-economic background and individual preferences among children (Castillo et al. 2011; Delaney and Doyle 2012; Bauer et al. 2014; Kosse et al. 2020) and adults (Gustavsson and Jordahl 2008). Here, we study whether such a link persists even in a highly homogeneous population of young adults: university students. Our subjects all have approximately the same age, they are all born in the same metropolitan area, and experienced a similar educational path. Yet, they come from districts characterized by a substantially different socio-economic environment. With a set of incentivized experiments, we investigate if these disparities across neighborhoods correlate with residents’ preferences in strategic and non-strategic situations. In addition, we measure if subjects condition their behavior on the area of residence of their counterpart.

Our results indicate that participants living in an area characterized by a high socio-economic environment tend to trust more, as compared to those coming from less wealthy neighborhoods. Importantly, this difference does not seem to be driven by a different perception of the value of money across neighborhoods. Instead, the data suggest that this behavioral difference is, at least in part, driven by a difference in beliefs: subjects from the most affluent part of the city have more optimistic expectations on their counterpart’s trustworthiness than those who live in the part of the city which is characterized by a lower socio-economic environment. We also find evidence that residents of wealthy neighborhoods are more inclined to reciprocate higher levels of trust, as compared to those living in the low SES area. We interpret this as evidence of a “consensus” effect (Butler et al. 2015), that might be amplified in a more homogeneous environment (Sapienza et al. 2013). By contrast, no significant differences emerge in terms of generosity (Dictator Game), risk attitudes, and time preferences, which are all elicited through tasks that do not imply any strategic interaction.

On the other hand, we do not find any systematic evidence of out-group or in-group discrimination. In particular, results from the Trust Game and the Dictator Game show that participants do not condition their beliefs and behavior on their counterpart’s area of residence. This result is in line with Blanco and Guerra (2017) who run a Trust Game and a Dictator Game with college students with a high or low socio-economic status, in Colombia. However, these findings do not necessarily generalize to the whole population (see for instance Falk and Zehnder 2013). In our case, since the trustee is likely to be a university student,Footnote 28 the trustor might think that he is different from his lot, and more akin to other students than to the average resident in that area.

Our findings from a follow-up study indicate that our sample is highly selected, as the SES divide in our pool of reference is not as marked as the one observed at the neighborhood level. Despite that, and after almost 20 years of schooling and being exposed to daily interactions with peers from different backgrounds, the socio-economic status of the area of residence has a persistent effect on trust and trustworthiness. Of course, there is only so much one can learn from a single experiment, and the rather small sample size combined with the lack of individual-level data on the family SES does not allow to advance any solid causal claim. That said, it is also useful to mention that relying on a student sample is likely to underestimate the nexus between economic preferences and the area of origin, which could be stronger in a representative sample.

However, if one takes our results at face value, they can have far-reaching policy implications. The results suggest that in a world characterized by increasing economic inequality, it is important to take into consideration the differences in preferences that might be determined by the socio-economic characteristics of the area of residence, and by the related socialization dynamics. If early socialization is important and has long-lasting consequences even on basic economic preferences, policymakers should actively foster cross-contamination by promoting inclusivity and avoiding school districting and segregation (e.g., ethnic segregation in public housing). This is in line with the findings by Chetty et al. (2016) on the advantages of moving to a better neighborhood early in life.

Availability of data and materials

Data are available upon request.

Notes

This is the case for some large US cities, such as New York or San Francisco. United States Census Bureau, 2005–2009. https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/2011/acs/acs-16.pdf.

For a meta-analysis on discrimination in laboratory experiment, see Lane (2016).

Our paper also relates to McEvily et al. (2012) who study how both behavioral and attitudinal measures of trust vary with the target of trust. We instead focus on how trust, trustworthiness, and generosity vary with the individual characteristics of both the first and second movers. We recently became aware that a similar approach has been adopted by Blanco and Guerra (2017) in an experiment conducted in Bogota (Colombia), with college students from different socio-economic status.

Bellettini et al. (2016) show that districts characterized by lower income, higher inequality, and higher percentages of foreign residents have a lower turnout rate than wealthier and more homogeneous neighborhoods, in the 2004 and 2009 local elections in Bologna. As the authors suggest, this difference is in line with the idea that higher contextual heterogeneity could discourage electoral turnout, since it might reduce civic cohesion and engagement.

The High SES area is often called the “Bolobene” (that could loosely translate into well off Bologna) and the Low SES area is sometimes dubbed “Bolofeccia” (the dregs of Bologna). No major incidents or fights between the two factions have occurred in the past. The main exception is a fight between two large groups from the two areas involving about 200 adolescents in the summer of 2013. https://www.ilrestodelcarlino.it/bologna/cronaca/2013/09/14/949754-rissa-ricchi-poveri-ask.shtml.

For more information on the socio-economic characteristics of the counties where the subjects from the hinterland reside, see Table 7 in Appendix A.

This is not uncommon in Italy; students going to college in the city where they were born and where their family resides usually live with their parents.

The interpretation of the trustor’s behavior as a measure of generalized trust has been debated in the literature (see Sapienza et al. (2013), and the references therein). In line with Sapienza et al. (2013), we find indeed that the quantity sent in the trust game is correlated both with the sender’s expectation of the receiver’s trustworthiness and with his own generosity.

In the experiment, this question was not incentivized. While incentives may reduce noise, there are practical costs of implementing and explaining the incentive scheme. Moreover, incentivization might generate distortions due to risk aversion or hedging (Schlag et al. 2015). Nevertheless, we tried to reduce the risk of having noisy beliefs, by first eliciting them quite at the beginning of the experiment (reducing the risk of having bored or tired subjects). Second, we implement a “role reversal” strategy both in the Trust and Dictator Game, as playing in both roles helps grasping the strategic nature of the game and can promote a deeper understanding of the rules of the game.

Here, we depart from Falk and Zehnder (2013) who varied the area of the opponent in a within-subjects fashion.

Both in the Trust Game and in the Dictator Game, at the bottom of each screens in which subjects took their decisions, we included a summary of the instructions where we reminded the rules of the game and the area of their partner.

We opted for a random re-matching between the Trust Game and the Dictator Game to minimize the possibility that participants will perceive the different tasks as one and hence compound decisions. Changing partner in between tasks emphasizes that each game has consequences for different players.

In designing the incentives scheme, we follow the recommendations in Charness et al. (2016): when we elicit time preferences through a multiple price list, we paid subjects only for one, randomly selected choice. Instead, when eliciting social preferences, we decided in favor of paying all tasks to avoid diluting incentives, as the authors report that there is no clear evidence that this affects subjects’ choices.

Earnings for time preferences were paid via bank transfers on the predetermined day.

As in Falk and Zehnder (2013), we set the intercept to zero to properly capture trustees’ sensitivity to different levels of trust. Remember that we use the strategy method to elicit the level of reciprocity; therefore, we have 6 data points for each subject.

In the computation of this measure, we drop 4 observations—2 from the South and 2 from the Hinterland—because these individuals switched multiple times.

The absence of any out/in-group discrimination is confirmed even when running a fully interacted model, where, for each outcome of interest, we include the player’s area dummy, the opponent’s area dummy, and their interactions. The results are available upon request to the authors.

Results are robust when using a OLS specification instead of non-linear models (see tables C1, C2, and C3 in the Appendix), and when we control for any “in-group” effect (see Table 8 in the Appendix).

See tables C4, C6, C5 in the Appendix.

As the difference in trustworthiness increases with the level of trust and no differences in the level of generosity emerge, we believe that higher SES participants are more reciprocal—rather than more generous in general—with respect to lower SES participants.

The failure to find any statistically significant difference in the generosity level across areas is also reassuring in terms of the perceived value of money across areas. Indeed, more generous behavior on the side of participants from a high SES area could have suggested that money was perceived as less important by those participants. This finding might not be surprising given that we focus on differences in the socialization context and not in the individual SES, and our subject pool is quite homogeneous (see follow-up study in Appendix A.2).

As a robustness check, we run a series of OLS regressions and all the results are qualitatively and quantitatively the same. The results are confirmed also by a series of Tobit regressions on the sub-sample of the stayers (see Appendix C).

The pairwise correlation between our incentivized measure of generosity and Questionnaire Help is of 0.20 and significant at the 5% level.

Notice that, even when we use a more stepwise approach, where we include one by one each of all the relevant regressors of Table 5, the magnitude of the effect of beliefs on trust is greater than any other effect. In addition, this approach further confirms that beliefs capture most of the across-areas variation in the level of trust. Results are available upon request.

Results are available upon request from the authors.

We did not provide any specific information on the individual characteristics of the opponent, but the questions subjects had to answer before starting to play would probably allow them to infer the nature of the subject pool.

We included questions 1–3 from Task 1. All the questions from Task 6 were present also in the follow-up. For question 3 in Task 1 (high school), we enlarged the set of options to include schools from the Hinterland. Due to a restructuring of the formal definition of some neighborhoods, we provided a finer grid to classify participants into areas. The full questionnaire is available upon request to the authors.

We include all the variables from the 2015 PISA questionnaire with the exception of variables ST011Q01TA, ST011Q02TA, ST011Q03TA, ST011Q05TA, and ST013Q01TA. We did not include the above items in an effort to adapt the questionnaire to our sample.

Peripheral areas are less well connected by public transport; that could explain the need to rely more on own means of transportation compared to people leaving in the city center.

References

Alesina, A., & La Ferrara, E. (2002). Who trusts others? Journal of Public Economics, 85(2), 207–234.

Algan, Y., Beasley, E., Vitaro, F., & Tremblay, R. E. (2014). The impact of non-cognitive skills training on academic and non-academic trajectories: From childhood to early adulthood. Sciences Po: Technical report.

Ananyev, M., & Guriev, S. (2019). Effect of income on trust: Evidence from the 2009 economic crisis in Russia. Economic Journal, 129(619), 1082–1118.

Andersen, S., Harrison, G., Lau, M., & Rutstrom, E. (2008). Eliciting risk and time preferences. Econometrica, 76(3), 583–618.

Andreoni, J., Nikiforakis, N., Stoop, J. (2021). Higher socioeconomic status does not predict decreased prosocial behavior in a field experiment. Nature Communication (forthcoming).

Ashraf, N., Bohnet, I., & Piankov, N. (2006). Decomposing trust and trustworthiness. Experimental Economics, 9(3), 193–208.

Bauer, M., Chytilová, J., & Pertold-Gebicka, B. (2014). Parental background and other-regarding preferences in children. Experimental Economics, 17(1), 24–46.

Bellettini, G., Berti Ceroni, C., & Monfardini, C. (2016). Neighborhood heterogeneity and electoral turnout. Electoral Studies, 42, 146–156.

Berg, J., Dickhaut, J., & McCabe, K. (1995). Trust, reciprocity, and social history. Games and Economic Behavior, 10(1), 122–142.

Blanco, M., & Guerra, J. A. (2017). To segregate, or to discriminate? That is the social identity question. Mimeo.

Butler, J. V., Giuliano, P., & Guiso, L. (2015). Trust, values, and false consensus. International Economic Review, 56(3), 889–915.

Butler, J. V., Giuliano, P., & Guiso, L. (2016). The right amount of trust. Journal of the European Economic Association, 14(5), 1155–1180.

Castillo, M., Ferraro, P. J., Jordan, J. L., & Petrie, R. (2011). The today and tomorrow of kids: Time preferences and educational outcomes of children. Journal of Public Economics, 95(11–12), 1377–1385.

Chakravarty, S., Fonseca, M. A., Ghosh, S., & Marjit, S. (2016). Religious fragmentation, social identity and cooperation: Evidence from an artefactual field experiment in India. Social Identity and Discrimination, 90, 265–279.

Charness, G., Gneezy, U., & Halladay, B. (2016). Experimental methods: Pay one or pay all. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 131, 141–150.

Chen, D. L., Schonger, M., & Wickens, C. (2016). oTree—An open-source platform for laboratory, online, and field experiments. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 9, 88–97.

Chetty, R., Hendren, N., & Katz, L. F. (2016). The effects of exposure to better neighborhoods on children: New evidence from the moving to opportunity experiment. American Economic Review, 106(4), 855–902.

Chuah, S. H., Gächter, S., Hoffmann, R., & Tan, J. H. (2016). Religion, discrimination and trust across three cultures. Social Identity and Discrimination, 90, 280–301.

Cox, J. C. (2004). How to identify trust and reciprocity. Games and Economic Behavior, 46(2), 260–281.

Crosetto, P., & Filippin, A. (2013). The “bomb’’ risk elicitation task. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 47(1), 31–65.

Delaney, L., & Doyle, O. (2012). Socioeconomic differences in early childhood time preferences. Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(1), 237–247.

Falk, A., & Zehnder, C. (2013). A city-wide experiment on trust discrimination. Journal of Public Economics, 100, 15–27.

Fershtman, C., & Gneezy, U. (2001). Discrimination in a segmented society: An experimental approach. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(1), 351–377.

Gambetta, D. (1988). Can we trust trust? In D. Gambetta (Ed.), Trust: Making and breaking cooperative relations. Basil: Blackwell.

Glaeser, E. L., Laibson, D. I., Scheinkman, J. A., & Soutter, C. L. (2000). Measuring trust. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(3), 811–846.

Golsteyn, B. H., Grönqvist, H., & Lindahl, L. (2014). Adolescent time preferences predict lifetime outcomes. Economic Journal, 124(580), 739–761.

Greiner, B. (2015). Subject pool recruitment procedures: Organizing experiments with ORSEE. Journal of the Economic Science Association, 1(1), 114–125.

Gustavsson, M., & Jordahl, H. (2008). Inequality and trust in Sweden: Some inequalities are more harmful than others. Journal of Public Economics, 92(1), 348–365.

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. (1986). Fairness as a constraint on profit seeking: Entitlements in the market. American Economic Review, 76(4), 728–741.

Koopmans, R., & Veit, S. (2014). Ethnic diversity, trust, and the mediating role of positive and negative interethnic contact: A priming experiment. Social Science Research, 47, 91–107.

Kosse, F., Deckers, T., Pinger, P., Schildberg-Hörisch, H., & Falk, A. (2020). The formation of prosociality: Causal evidence on the role of social environment. Journal of Political Economy, 128(2), 434–467.

Kosse, F., & Tincani, M. M. (2020). Prosociality predicts labor market success around the world. Nature Communications, 11(1), 1–6.

Lane, T. (2016). Discrimination in the laboratory: A meta-analysis of economics experiments. European Economic Review, 90, 375–402.

McEvily, B., Radzevick, J. R., & Weber, R. A. (2012). Whom do you distrust and how much does it cost? An experiment on the measurement of trust. Games and Economic Behavior, 74(1), 285–298.

Mischel, W., Shoda, Y., & Rodriguez, M. I. (1989). Delay of gratification in children. Science, 244(4907), 933–938.

Moffitt, T. E., Arseneault, L., Belsky, D., Dickson, N., Hancox, R. J., Harrington, H., et al. (2011). A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(7), 2693–2698.

OECD. (2011). Divided we stand: Why inequality keeps rising. Paris: OECD Publisher.

OECD. (2017). Pisa 2015 technical report. Technical Report 67. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Piff, P., Kraus, M., Côté, S., Cheng, B., & Keltner, D. (2010). Having less, giving more: The influence of social class on prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(5), 771–784.

Sapienza, P., Toldra-Simats, A., & Zingales, L. (2013). Understanding trust. Economic Journal, 123(573), 1313–1332.

Schechter, L. (2007). Traditional trust measurement and the risk confound: An experiment in rural Paraguay. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 62(2), 272–292.

Schlag, K. H., Tremewan, J., & Van der Weele, J. J. (2015). A penny for your thoughts: A survey of methods for eliciting beliefs. Experimental Economics, 18(3), 457–490.

Sutter, M., Kocher, M. G., Glätzle-Rüetzler, D., & Trautmann, S. T. (2013). Impatience and uncertainty: Experimental decisions predict adolescents’ field behavior. American Economic Review, 103(1), 510–531.

Veall, M. R., & Zimmermann, K. F. (1996). Pseudo-r2 measures for some common limited dependent variable models. Journal of Economic Surveys, 10(3), 241–259.

Weng, W., & Yang, F. (2014). The impact of social identity on trust in China: Experimental evidence from cross-group comparisons. Applied Economics, 46(16), 1855–1860.

Acknowledgements

We thank E. Fatas, R. Weber, and D. B. Huffman for insightful discussions. We are grateful to participants at the IMEBESS Workshop in Florence and the NoBeC Workshop for useful comments. This work was supported by the Italian Ministry of Education and Research [SIR grant no. RBSI14I7C8]; and the UniCredit & Universities Foundation [Modigliani Fellowship 2015]. Significant parts of this research were developed, while the second author (Bortolotti) was at the University of Cologne and at the Max Planck Institute for Research on Collective Goods; she thanks those institutions for the financial and logistic support. The usual disclaimer applies.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Alma Mater Studiorum - Università di Bologna within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Code availability

The software codes are available upon request.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix A

Appendix A

1.1 A1: Additional tables and figures

See Tables 6, 7, 8, 9 and Figs. 5, 6.

1.2 A.2: Online survey about participants’ SES

Since we are mainly interested in the effect of neighborhoods on preferences, in the main questionnaire of our experiment, we only collected information about the place of residence of our participants. What is important for our analyses are indeed the aggregate statistics about the areas of residence and not necessarily the SES of participants themselves. It is still interesting to have a better understanding of the composition of our subject pool, as one would not necessarily expect it to fully reflect the aggregate figures for each area—as almost all our participants are enrolled in a college major or have a college degree. In particular, in case our pool reflects the same characteristics of the area of residence, any difference in preferences could be driven either by the family background or by a neighborhood effect. On the contrary, if our subject pool is more homogeneous, the neighborhood effect is more likely to be the main driver of our results. To grasp a better understanding of the actual SES of our participants, we run a follow-up survey in 2019, in which we collected a series of proxy for SES at the household level.

Subject pool As in the main experiment, we recruited participants born in the metropolitan area of Bologna using the information available in our database. All subjects who met the criteria were invited to sign-up for a short online questionnaire via ORSEE (Greiner 2015). Invitations were also sent to the participants of our main experiment who were still present in the dataset (\(N = 130\)). For privacy reasons, we are not allowed to link results from the current survey with data from the main experiment. It is important to stress that the recruitment procedures were very similar to the ones used in the main experiment, as to minimize any possible experiment-specific selection effect. Of the 433 invited subjects, 198 signed up and 183 successfully completed the questionnaire (64 of them also took part in the main experiment).

Questionnaire and procedures The follow-up study builds on Task 1 and Task 6 from the main experiment (see Appendix B), and includes questions about the area of residence, gender, education, employment, best friend, and personal attitudes (risk, trust, and welfare state).Footnote 29 In addition, we collected information about the education level of the parents and a series of proxies for the economic status of the household taken from the 2015 PISA questionnaire (OECD 2017). The survey was run online using the Qualtrics platform. Only participants invited via the ORSEE system who signed up for the online survey were allowed to take part in the study, and the systems prevented participants to take the survey more than once. Upon receiving the link, participants had 1-week time to complete the survey. Median completion time was about 8 min. Eight participants (1 in 25) were randomly selected at the end of the survey and received a fixed payment (via bank transfer) of 50€.

Main results Table 10 presents the main results from the follow-up survey. The first block of variables reports the highest educational level achieved by each parent on a scale from 1 to 6 (OECD 2017). No difference across areas emerges from our data. The second block of variables aims at capturing the wealth possessions of the family.Footnote 30 We fail to find any systematic difference between high SES and low SES areas (nor the Hinterland). Perhaps unsurprisingly, families leaving in the Hinterland tend to have larger houses and more cars.Footnote 31 As for the comparison between high SES and low SES areas, the only differences pertain cultural items (e.g., classic book, books on art, music, or design, and e-book readers). Overall, our sample is remarkably homogeneous and only small differences emerge across areas.

In-group and out-group trustworthiness, by SES area. The figure displays the average amount of money returned by trustees, given the amount of money received, by trustee’s and opponent’s areas. In-group refers to the case in which the opponent is from the same area of the trustee. Out-group refers to the case where the trustee and the opponent are from different areas

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bigoni, M., Bortolotti, S. & Rattini, V. A tale of two cities: an experiment on inequality and preferences. Theory Decis 92, 189–222 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-021-09803-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-021-09803-6