Abstract

Many environmental problems represent social dilemma situations where individually rational behaviour leads to collectively suboptimal outcomes. Communication has been found to alleviate the dilemma and stimulate cooperation in these situations. Yet, the knowledge of the basic elements, i.e. the types of information that need to be provided and exchanged to make communication effective, is still incomplete. Previous research relies on ex post methods, i.e. after conducting an experiment researchers analyse what information was shared during the communication phase. By nature, this ex post categorization is endogenous. In this study, we identify the basic elements of effective communication ex ante and evaluate their impact in a more controlled way. Based on the findings of previous studies, we identify four cooperation-enhancing elements of communication: (i) problem awareness, (ii) identification of strategies, (iii) agreement, and (iv) ratification. In a laboratory experiment with 560 participants, we implement interventions representing these components and contrast the resulting levels of cooperation with the outcomes under free (unstructured) or no communication. We find that the intervention facilitating agreement on a common strategy (combination of (ii) and (iii)) is particularly powerful in boosting cooperation. And if this is combined with interventions promoting problem awareness and ratification, similar cooperation levels as in settings with free-form communication can be reached. Our results are relevant not only from an analytical perspective, but also provide insights for social dilemma situations in which effective communication processes cannot be successfully self-organized, calling for some form of external, structured facilitation or moderation.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Many environmental problems represent social dilemma situations where individually rational behaviour leads to collectively suboptimal outcomes. A long tradition in social science research examines how cooperation can be facilitated and sustained in such situations. One finding in this stream of literature is that communication between the involved actors can promote cooperation (Balliet 2009; Chaudhuri 2011; Ledyard 1995; Sally 1995). Existing studies examine why communication enhances cooperation (Kerr and Kaufman-Gilliland 1994). A first explanation is that communication promotes the emergence of cooperative social norms (which constrain the socially acceptable action space) (Bicchieri 2002). A second explanation is that communication facilitates the emergence of a group identity, and that the resulting sense of belonging activates social preferences (Dawes et al. 1988; Orbell et al. 1988). Finally, a third explanation is that communication helps actors to coordinate their beliefs, which is particularly powerful when the majority of actors are conditional co-operators (Cardenas et al. 2004; Chaudhuri et al. 2017; Dawes et al. 1977; Isaac and Walker 1988).

But what information, when exchanged during the communication process, fosters cooperation? This question ties back to the definition of communication. With the origin in the Latin word communicare—to share—communication is understood as “a process by which information is exchanged between individuals through a common system of symbols, signs, or behaviour” (Merriam Webster 2019). Typically, in social science experiments on communication, subjects exchange messages face-to-face or through an open text chat. In order to understand what type of information in the `black box´ of communication improves cooperation, researchers then analyse ex post the content of the conversations and categorize the messages exchanged during the communication phase (Pavitt et al. 2005). By nature, this ex post categorization is endogenous (Janssen 2013; Ostrom et al. 1992; Schill et al. 2016). Hence, existing research can only provide hints about what kinds of information promote cooperation when shared. Some groups may cooperate successfully after the communication phase, and cooperation-promoting elements can be identified on the basis of their verbal exchange. But the increase in cooperation cannot be attributed to these elements with certainty when the observed communication is group-specific, i.e. it might simply be the type of communication that groups who would cooperate anyway engage in. The results from previous studies that show, on the contrary, that some groups have difficulty in reaching a common agreement on cooperation in free communication (Cardenas et al. 2011; Ostrom et al. 1992; Schill et al. 2016), also hint to this.

In this study, we identify the elements of effective communication and evaluate their impact, on contrast, in a more controlled way. We do so by probing the effectiveness of the previously identified elements of effective communication with an ex ante approach. We start our study with a review of social dilemma studies which implemented free form communication and analysed ex post the content of the messages. Based on these studies, we identify four information elements of communication which have been recurrently listed as potentially important to promote cooperation, namely, problem awareness, identification of strategies, agreement and ratification. We then develop experimental interventions which represent these four elements and test their impact on cooperation in a public good game. By controlling the information that participants are presented with and/or are allowed to exchange, we can track the consequent changes in behaviour. Lastly, we contrast the performance of our interventions against two baseline settings: no communication and free communication. In comparison to existing studies, which report purely correlative links between certain communication elements and subsequent cooperation levels, we instead can derive causal inferences and evaluate the performance of each element individually and in combination. We find that the intervention which facilitates agreement on a common strategy (identification of strategies + agreement) has the strongest effect on cooperation. Combined with the intervention promoting problem awareness and ratification, high levels of cooperation can be reached which are similar to what we observe under free communication. The results of this study show that it does not suffice to have public information on the social dilemma dynamics (problem awareness) or the financial consequences of individual and joint courses of action (identification of strategies) to promote cooperation. Participants, in addition, require opportunities to exchange with others on their intentions to build and abide to agreements for cooperation (agreement and ratification).

Why is it important to identify the elements of effective communication? First, our findings contribute to the understanding of communication in social dilemma situations, especially regarding the question what information when shared fosters cooperation. This, in turn contributes to the widely discussed question of why communication enhances cooperation. Second, we show that by offering mechanisms which resemble the basic elements of effective communication the cooperation-enhancing effect can (almost) be replicated. But, our mechanisms allow us to control what information is shared and with whom. This structured approach may be advantageous when (i) actors involved in the social dilemma are numerous, (ii) not all actors involved have the courage or power to speak up, (iii) factors concerning the social dilemma are complicated and when (iv) meetings are time consuming, because they are poorly structured or organised, or logistically difficult. These conditions are prevalent in many environmental social dilemma situations and external facilitation and moderation can under these circumstances help the involved actors to deliberate on their choices. In fact, the elements of effective communication we have identified bear a strong resemblance with methods that are, for example, used in participatory processes. Our systematic assessment of the elements which make communication effective may therefore provide useful insights into how such external facilitation and moderation processes must be structured and designed to be effective in promoting collective action.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2 we review the insights from previous studies on communication and derive the cooperation-enhancing elements of effective communication. In Sect. 3we describe our experimental design and implementation. We present and discuss our experimental results in Sect. 4 and summarise our conclusions in Sect. 5.

2 Four Elements of Effective Communication

As stated above, a common way to analyse the content of communication is by examining the protocols of the discussion ex post. The aim of this analysis is to explore what information participants shared during the communication phase and hence understand what might drive the cooperation-enhancing effect of communication. Typically, researchers bundle and encode the recorded messages according to different information categories. This analysis allows to identify the correlative links between the shared information and subsequent cooperative behaviour. The following section summarises and describes the four information categories we found when reviewing the literature. Our review encompasses those social dilemma studies which have analysed the content of free communication, reported the coding results in the paper, and were available at the time of our review.Footnote 1

2.1 Problem Awareness

At the beginning of a communication phase, it is observed that participants try to find a common understanding as a basis for the following discussion. Brosig et al. (2003) describe problem awareness as the first of three steps in which misunderstandings in a communication phase are clarified to ensure that the “dilemma structure (is) common knowledge” (p. 226). Pavitt et al. (2005) assign eight to 13 percent of their recorded information units, depending on the treatment variation, to the category “Game understanding: Discussion relevant to the rules of the game, with the general intent of increasing game players’ understanding of how the game is played.” A further four to six percent, depending on the treatment variation, were assigned to the information category “Past or practice round: Discussion relevant to what occurred during past rounds in the game or during the practice round” (pp. 352). Brandts et al. (2016) report that 42 to 50 percent of the group leaders in their experiment sent at least once a message to their group with “content of comprehension” like an “[o]bservation of decline” (p. 812) of the cooperation rate or “[o]bservations of followers undercutting” (p. 812). Finally, Lopez and Villamayor-Tomas (2017) categorise 45 percent of the total of 1,493 messages recorded to the two information categories “Game dynamics” and “Past result and actions”, with the former taking into account descriptions of free riding or “[s]tatements describing the dilemma between individual appropriation and group gains” (p. 73).

Taken together, messages in these categories describe the situation players found themselves in and aim at creating a common understanding of the game and the consequences of single actions.

2.2 Strategies

In order to overcome the identified problem, participants subsequently communicate about how to address the social dilemma, i.e., they identified strategies. Lopez and Villamayor-Tomas (2017) assign 22 percent of their messages to the category “Collective strategy” or “Individualistic strategy [:] Statements pointing to strategies wherein each participant decides what to do independently from other participants’ decisions” (p. 73). Pavitt et al. (2005) report that six to seven percent of the identified information units fit into the category “General strategy: Discussion relevant to the general strategy to be used in subsequent rounds.”(p. 352), while 52 to 57 percent include information on a “[s]pecific strategy: Discussion relevant to specific proposed strategies; i.e., proposals including specific numbers of points to be harvested.” (p. 352) and six to nine percent include “[s]tatements that ask for or are part of calculations relevant to proposals, along with acknowledgments following those statements.” (p. 352). Koukoumelis et al. (2012) formed a very similar category “Payoff calculation: Calculation of the (period or overall) payoff associated with the proposal.” (p. 386) and found that 67 to 78 percent of the team leaders in their experiment sent at least once a message containing such a calculation to their fellow team members. Brandts et al. (2016), in turn, adopted the coding scheme of Koukoumelis et al. and found that payoff calculations occurred less frequently, that is only 42 percent of the team leaders sent at least once a calculation to their team members.Footnote 2 Similar to the calculation category, Pavitt et al. (2005) formed an additional information category describing the results of the individual proposals, “Elaboration: Non-evaluative statements about previously offered proposals and their consequences“, which occurred in 28 percent of their information units.Footnote 3

In summary, two major topics are nestled within the categories above: First, strategies are formulated. Second, participants elaborate on the consequences of these strategies, specifically by calculating the resulting payoffs. The high observed frequencies suggest that the formulation and elaboration of strategies is an important element in communication which aims to solve the social dilemma. And, it forms the basis for the following step: the agreement.

2.3 Agreement

After the strategies are described, participants made proposals to agree about what strategy is most favoured within the group. Here, Lopez and Villamayor-Tomas (2017) consider the following information categories, “Evaluation”, “Proposal: Statements suggesting a strategy to be followed in the subsequent rounds of the experiment” and two categories describing associated approval or disapproval named “Positive maintenance” and “Negative maintenance” (p. 74). These four categories were observed in six to 16 percent of all messages, respectively. Pavitt et al. (2005) distinguish between the information category “Evaluation: Statements that ask for or provide explicit or implicit acceptance or rejection of the proposal under consideration, or asks for an evaluation” and “Suggestion: Statements that introduce or ask for a proposal, along with acknowledgments following those statements” (p. 352), 11 percent of the information were identified to belong to these two categories. Also, Koukoumelis et al. (2012) observed that 94 percent of the leaders in their experiment sent at least once a “[s]uggestion (point or interval) of how much to contribute to the project” and 78 to 83 made at least once an “[e]fficient suggestion: Implicit or explicit suggestion to contribute the whole endowment” (p. 386). Following Koukoumelis coding, Brandts et al. (2016) find that 83 to 91 percent of the leaders made at least once a suggestion and 36 to 42 percent an efficient suggestion.Footnote 4 Brosig et al. (2003) describe that “some subjects first observed that it would be best if all group members contribute their whole endowment in every round.” (p. 225). Finally, Bochet et al. (2006) find that “about a quarter of substantive messages are concerned with discussion of what the best strategy would be” (p. 21).

Overall, in the component agreement, participants evaluated the previously defined strategies and made proposals about which of the strategies should be implemented in the group. In the discussions, participants tried to agree upon the most favoured strategy.

2.4 Ratification

Agreeing on the most favoured strategy does not automatically imply also implementing it. The ratification category captures whether communication is used to “devise verbal agreement [were given] to implement these strategies” (Ostrom et al. 1992). This communication element is regarded as an important factor in facilitating cooperation (Kerr and Kaufman-Gilliland 1994; Orbell et al. 1990, 1988; Sally 1995). Cardenas et al. (2004) state that an “agreement or ratification of the need for every player to choose a low level of extraction” is the second of two steps to “build an effective agreement for co-operation” (p. 275). In line with this, Bochet et al. (2006) find that beside those messages which were posed to identify the most favourable strategy “most of the remaining messages [were] statements of commitment to the common strategy” (p. 21). Brosig et al. (2003) even state that promises were made in all groups of their experiment: “In this group all subjects promised to fully cooperate until round 9; in all other groups all subjects promised to cooperate (either explicitly in all rounds or not).” (p. 226). But promises were not in all studies so frequent. Pavitt et al. (2005) find that only three to four percent of their information units categorise as “Confirmation: Statements that either state the decision in its final form or ask for or provide an explicit group acceptance of a proposal.” (p. 352). In Koukoumelis et al. (2012) a “Promise: Pledge to contribute some specific amount.” (p. 386) was made at least once by eleven percent of the leaders, while Brandts et al. (2016) detected that 18 to 25 percent of their leaders made such a promise.

In summary, participants express in this final element their intention to abide by the previously reached agreement. The way in which this public commitment takes place varies from group to group, depending on the specific dynamics of their communication process.

Taken together, all previous studies that examined the communication content ex post identified problem awareness, identification of strategies, agreement on a common strategy and ratification as important contributors for the positive impact communication can have on cooperation in social dilemmas. This observation is particularly interesting when one takes into account that the studies employed different designs and framings. Koukoumelis et al. (2012) and Brandts et al. (2016), for example, allowed only one actor, the leader, to communicate via written messages in a public good game, whereas in Pavitt et al. (2005) and in Lopez and Villamayor-Tomas (2017) all group members in the associated common pool resource game could communicate and did so face-to-face. Furthermore, the studies were conducted in culturally different locations and used different categorization and coding schemes. Figure 1 summarises the findings from the literature review about which elements improve cooperation when used in communication and shows their typical chronological sequence.

3 Experimental Design and Implementation

Our experiment is built on a two-stage design. In the first stage, participants are randomly assigned to groups of four and play ten rounds of a standard linear public good game (see Ledyard 1995). The payoff structure is \({\pi }_{i}=20-{g}_{i}+ 0.4 \sum_{j=1}^{4}{g}_{j}.\) After each round, participants receive feedback on the sum of total contributions to their group project, the average contribution of the other players and their own potential payoff from this round. At the end of the experiment only one round of each stage is randomly selected to determine the actual payment.

After the tenth round, participants learn that the first stage of the experiment is over and that the second stage will employ the same game as before. We have chosen to keep the group composition across the two stages constant. Although this design decision potentially reduces the magnitude of our treatment effects, in all applications for which our results may have implications, such as resource management settings, actors have a history of interactions.

Groups in the control group No Communication start directly after this information with the second set of ten rounds of the public good game. Groups assigned to the treatment groups, in contrast, receive the treatment-specific information before starting with the second stage of the game. The treatments consist of a mechanism resembling one or a combination of the identified elements of effective communication: (a) problem awareness, (b) identification of strategies, (c) agreement, and (d) ratification. We also implement a second control condition ‘Free communication’, in which participants could, like in previous studies, communicate through an open text box with their group members. The chat was open for 10 min and messages sent were visible to all group members.Footnote 5 We see our treatments as interventions which an external actor might draw upon to facilitate cooperation. After the intervention, players also play a set of ten rounds. With this repeated interaction, we can not only identify immediate effects, but also examine whether the effects persist over the course of several interactions.

In sum, this design allows us to control for heterogeneities in group’s contribution behaviour before the intervention and track the subsequent behavioural changes in a between and within comparison. In the following, we describe how we implemented each of the four information elements of effective communication in the experimental treatments.

3.1 Problem Awareness

In the treatment Problem Awareness (PA), subjects were first confronted with their group’s behaviour in stage 1: a chart delineated how their groups’ total contribution to the project developed over the first ten rounds (see Fig. 1 in the appendix). Afterwards, a stylized curve was displayed showing the typical decay of contributions commonly observed in public goods games (see Fig. 2 in the appendix).Footnote 6 This second graph was accompanied by a text explaining why the curve was downward sloping. The explanation highlighted that participants, who are not willing to accept free riding, commonly decrease their contributions when they detect that there are free-riders among their group members. In consequence, contributions deteriorate over time.

3.2 Strategies

For the identification of strategies, we presented to the participants three potential ways on how to contribute to the public good: (i) the socially optimal strategy, i.e., all group members contribute their entire endowment to the project, (ii) the self-interested strategy, i.e., all group members contribute nothing to the project, and (iii) a laissez-faire strategy, where the group members contribute to the project whatever they want. To ease the understanding and evaluation of each strategy, we displayed the individual and group payoffs resulting from each strategy. The participants could visualise each strategy and its possible consequences as often as they liked. (Please see the appendix for a detailed description of the scenarios and the screenshots, Fig. 13).

3.3 Agreement

After participants could make themselves familiar with the potential consequences of the three strategies, they were guided to a voting stage in which participants were asked which strategy they would like to see implemented in their group. Because it is not possible to vote on strategies before first learning about them, we implemented the Agreement element always in combination with the Strategies element. With help of a multistage voting mechanism, the groups could agree on what strategy was the most favourable. If the four group members agreed unanimously on the socially optimal strategy in the first vote, the group learned the voting result and moved on with the experiment. If this was not the case, then the group members, after having learned the voting result, were asked to take a second vote. Thus, the participants were encouraged to reconsider any choice that is not socially optimal. We have implemented this weak normative nudge from the perspective of an external authority interested in structuring processes of information exchange that might facilitate cooperation.

After the second vote, participants received again feedback on the voting result. If the voting behaviour was stable, that means all group members voted exactly the same way as they did before, the group moved on. If, in contrast, at least one group member changed her previously indicated preferred strategy, the group was asked to vote for a third and last time. Subsequently, the voting result was shown and the group moved to the next step in the program. (Please see Fig. 3 in the appendix for an illustration of the voting mechanism).

By being confronted either with voting results or others’ contribution to the discussion, subjects learn about the preferences of their fellow group members. This information is likely to change actors’ expectations about the behaviour of the other actors and this potentially alters the behaviour (due to the principle of conditional cooperation).

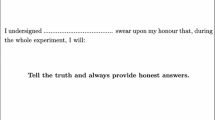

3.4 Ratification

In our experiment, the Ratification element only became active when the majority of the group members voted previously for the socially optimal strategy and naturally could only be implemented in combination with the other three elements. The implementation followed a mechanism developed by Koessler et al. (2018): First, subjects were asked whether they wanted to promise that they will follow the socially optimal strategy in all rounds of the following game. If they agreed, they had to key-in the following statement: “I promise to contribute 20 points in all subsequent rounds.” (see Fig. 16 in the appendix). Previous research has shown that engaging individuals pro-actively in the act of promise-making induced a higher commitment to the promised behaviour (Kiesler 1971). After all group members made their decision about the promise, feedback was provided on which group members made the promise. Then the second stage of the experiment started. Table 1 summarises all treatments and outlines the respective elements of effective communication we have implemented in each treatment group.

The experiment was conducted at the experimental laboratory of the University Osnabrück using the experimental software SOPHIE (Hendriks 2012). Subjects were students recruited from the local database of potential subjects via ORSEE (Greiner 2015). Average earnings were 9 € and one session lasted about 45 min. In total, we conducted 33 sessions with a total of 560 subjects. The appendix contains descriptive statistics across treatments.

3.5 Identification Strategy

Our treatment conditions allow us to evaluate how the four elements change the consequent cooperation behaviour. By their nature, some mechanisms representing the four information elements of effective communication could only be implemented in combination. For example, an agreement by voting on the most favourable strategy requires that the available strategies are previously known, and a common strategy can only be ratified if it has been established in advance.

In the experimental evaluation, we can probe whether the four elements which have been identified by previous studies as cooperation-enhancing, are indeed beneficial. The conditions No communication and Free Communication serve hereby as controls for both ends of the spectrum, that is no communication and free, unstructured communication. Against the resulting cooperation levels in these conditions, we can assess what impact our structured elements of effective communication have, individually (for PA and Strategies) and in combination (PA + Strategies + Agreement and Full Set).

With our two stage design, we can assess how groups change their cooperation levels after being treated with one or more structured elements, while controlling for the group’s baseline cooperation level. Specifically, we formulate the following hypotheses: (H1) Our interventions mimicking effective element of communication have a positive effect on cooperation. (H2) In combination the interventions have a stronger effect. As previous studies have indicated, the sequential combination may be needed for a positive effect to unfold: “while communication is an effective tool for enhancing collective action, it can only work through a series of steps that start from the understanding of the mapping of actions into outcomes in the social dilemma to the crafting of the agreement” (Cardenas et al. 2011).

With comparison to Free Communication we will explore whether our structured interventions perform better or worse in promoting cooperation than free unstructured communication. Finally, the repeated interactions allow us to study (i) how the groups adjust their level of cooperation immediately after treatment, and (ii) how the cooperation levels develop over time, that is how sustainable our treatment effects are.

4 Results

In the following, we first analyse the average treatment effects on cooperation based on the total group contributions to the public good. Subsequently, the dynamic development of cooperation is examined.

4.1 Average Treatment Effects

Compared to the first stage of the game, cooperation increased in the second stage in all treatment conditions, except in the No Communication group (see Fig. 2 and first three columns of Table 2). It seems that the interventions mimicking the elements of effective communication were successful in increasing cooperation. Specifically, for the Problem Awareness and for the Strategy intervention, the change in cooperation between Stage 1 and Stage 2 was different from that under No Communication, although at 10% level only (Wilcoxon rank sum test on Diff avg; p = 0.09 and p = 0.08, respectively). For the other treatments the effect was significant at the 1% level (No Communication vs. treatment: p < 0.01 for all other treatments).

The small effect of Problem Awareness is consistent with the findings of Brandts et al. (2016), whose mechanism design we employed in the Problem Awareness intervention. Based on the results of their experiment, the authors concluded that advice giving has only a significant positive effect if the advice is given by a peer, but not when it is provided by an expert. In our experiment, the explanation of why contributions deteriorate was given by the experimenter, i.e., an expert.

Also the identification and exploration of available strategies alone (treatment Strategies) lead only to an incremental improvement in cooperation. This is in line with what was proposed in previous work based on the ex post analyses: individually identifying the best strategy is not sufficient for collective action, it must be combined with the awareness and credibility given to the expected decisions of others (Cardenas et al. 2004; Isaac and Walker 1988; Ostrom et al. 1992). In line with this we find that, when the strategies treatment was combined with a subsequent opportunity to agree on a common strategy (treatment Strategies + Agreement), cooperation was facilitated and an increase of 57% was achieved as compared to the before- treatment level of cooperation (p = 0.07). Adding Problem Awareness to this sequence leads to a small incremental improvement (average cooperation increases by 67% compared to 57% under Strategies + Agreement, p = 0.25). The increase in cooperation becomes then statistically significant when a further element of communication is added to the core element Strategies + Agreement, namely the Ratification element—in which players reaffirmed with a pledge their intention to contribute (Wilcoxon rank sum test on Diff avg; Strategies + Agreement vs. Full Set p = 0.04).

In sum, going through the full set of our elements resembling effective communication (Full Set = PA + Strategies + Agreement + Ratification) produced an increase in cooperation by 98% compared to cooperation levels before treatment. Despite this remarkable increase, the treatment Free Communication, in which groups could communicate freely for 10 min via a chat box, still achieved significantly higher cooperation levels (Wilcoxon rank sum test: Full Set vs. Free communication: p = 0.04).

Since baseline cooperation levels differed between groups, we will assess the robustness of our observations with help of a multivariate regression analysis. Table 3 presents the estimates from a Random effects Tobit model, censored at the lower limit (0) and the upper limit of group contributions (80). All models estimate the change in average group contributions in Stage 2 (i.e., after the treatment interventions) controlling for the heterogeneity among groups in the baseline contributions. In Stage 1, all groups received the identical instructions and played the baseline, any differences in the contribution levels before treatment are thus to be attributed to varying group compositions and differences in the group dynamics developed during Stage 1.Footnote 7

Model 1 focuses on the average treatment effect and estimates the effect of each intervention on the subsequent contribution behaviour. In addition, we control for the dynamic effects in model 2 (discussed in the next section) and exclude in model 3 the last two rounds to preclude end round effects.Footnote 8 In this section, we focus on the discussion of the average treatment effects, i.e. the coefficients on our treatment dummies, based on model 1. We use cooperation levels in No Communication as reference point.

We find support for our previous findings. In all treatment groups cooperation increases after the interventions, compared to No Communication. The effect of Problem Awareness and Strategies is hereby not statistically significant, while all other interventions lead to a significant increase in cooperation at the 1% level (p < 0.01 for Strategies + Agreement, PA + Strategies + Agreement and Full Set).Footnote 9 We thus find partly support for hypothesis 1, the Agreement element is necessary for a significant positive effect to unfold.

RESULT 1 (average effect): Structured interventions mimicking the elements of effective communication lead to a significant increase in cooperation if groups are given the possibility to agree on a common strategy.

To examine the differences between treatment groups we conduct Wald tests for differences in coefficient estimates, the results of which are presented in Table 6 of the appendix. In the following, we focus on the most important results. When we assess whether the interventions had a stronger effect in combination, we find that the performance of the core element Strategies + Agreement indeed significantly improved when Problem Awareness was preceded (Strategies + Agreement vs. PA + Strategies + Agreement: p = 0.008 and Strategies + Agreement vs. Full Set: p = 0.000). One interpretation might be that being informed of the problem and the underlying social dilemma structure highlighted the need to coordinate and cooperate as a group in order to achieve desired outcomes. Adding Ratification to the sequence PA + Strategies + Agreement lead to a small additional but non-significant boost in contributions (PA + Strategies + Agreement vs. Full Set: p = 0.16).

RESULT 2 (average effect): The combined sequence with all interventions leads to a stronger increase in cooperation than the intervention facilitating agreement on a common strategy alone.

Lastly, the analysis reveals that when heterogeneities in baseline contributions are taken into account, the combined set of our interventions: Problem Awareness + Strategies + Agreement + Ratification (Full Set), produces a cooperation-enhancing effect which is no longer statistically different to the effect of Free Communication (Full Set vs. Free Communication: p = 0.14).

4.2 Dynamic development of cooperation over time

Model 2 and 3 take into account the dynamic of how contributions evolved in the rounds after the treatment. Figure 3 shows the corresponding average group contribution per round across all treatment conditions. Individual graphs describing the development for each single group across the treatments can be found in the appendix.

A visual inspection of the development over time reveals that cooperation decreased over time in both stages and in all treatment groups. Such a decline is commonly observed in repeated public good games and occurs due to the endgame effect and participants being, on average, (imperfect) conditional contributors (Fischbacher and Gächter 2010). At the end of Stage 1, cooperation levels are similar across all treatment groups. At the first round of Stage 2, cooperation increased in all groups. However, in line with our earlier results, the cooperation levels at which groups started Stage 2 vary greatly across treatments (see also last two columns of Table 2). The increase is significantly stronger after our interventions than in the No Communication treatment (p < 0.05 for Strategy and p < 0.01 for all combined treatment),Footnote 10 suggesting that the interventions lead to an increase additional to the usual restart effect.Footnote 11 The difference between the increase in cooperation in Problem Awareness and No Communication is not statistically robust.

Moreover, the maintenance of the achieved contribution levels over time varied among the treatment groups. Looking at models 2 and 3 in Table 3 we find the following: The coefficient on Round*Problem Awareness indicates that the deterioration rate in Problem Awareness is similar to the decline observed in No Communication. By contrast, the deterioration in all other treatment groups is steeper than in No Communication (p < 0.05 in model 2).

In model 3, we do not consider the last two rounds in which typically the end-game effect takes place, i.e. cooperation collapses towards the end of the game (Andreoni 1988). When excluding the last two rounds from the analysis, we find that the deterioration of cooperation in PA + Strategy + Agreement and in Free Communication is no longer steeper than in No Communication (p = 0.67 and p = 0.27, respectively).Footnote 12 In combination with the higher starting level of cooperation in the first round of Stage 2, this indicates that Free Communication and PA + Strategy + Agreement hence manage to sustain the cooperation increase as compared to No Communication. The initial increase in cooperation in Free Communication was hereby stronger than in PA + Strategy + Agreement (p = 0.04).Footnote 13

4.3 Achievement of Social Optimum

Another dimension of contribution behaviour is how often groups in the respective treatment groups reached the social optimum. We briefly discuss results from inspecting this measure of successful cooperation across treatments. In the first stage, the baseline stage, only four out of the 140 groups managed to reached the social optimum in at least one of the ten rounds.Footnote 14 After the interventions in Stage 2, in Problem Awareness and Strategy, four out of 20 groups reached the social optimum at least once. In Strategy + Agreement half of the groups reached the social optimum at least once, while in PA + Strategy + Agreement and in the Full Set a clear majority of 18 groups, and in Free Communication all 20 groups managed to reach the social optimum in at least one of the ten rounds. This indicates that our interventions helped groups in reaching the social optimum. But could the groups maintain these high levels of cooperation? We find that, on average, groups in No Communication and in Problem Awareness reached the social optimum in less than 10% of the rounds. In Strategy and in Strategy + Agreement groups reached the social optimum in 30% of the rounds, while in the treatments comprising the combined sequence of elements (PA + Strategy + Agreement and Full Set) groups reached the social optimum in 51% and 69% of the ten rounds, respectively. Finally, in Free Communication, groups reached the social optimum in an overwhelming 83% of the rounds.Footnote 15 Hence, the analysis on this measure of cooperation supports Result 1 and 2: the combined interventions (and free communication) lead to a positive effect on cooperation.

4.4 Explorative Analysis of Chats in Free Text and the Uncovered Element: Social Chit Chat

In summary, we find that the combined sequence of interventions representing elements of effective communication promotes a statistically significant increase in cooperation and contributes to the maintenance of relative high cooperation levels which are similar to what we observed under Free Communication. However, free communication still somewhat outperforms this structured process of information exchange. Under Free Communication, cooperation levels reached the social optimum more often. We speculate that Free Communication offers something that promotes cooperation in addition and that we do not capture this element in our proposed elements for effective communication. To shed more light on the missing element, we analysed the content of the group chats in a similar way as the studies we reviewed in Sect. 2. To do this, we first asked two research assistants to go through the protocols and suggest categories to codify the messages of the participants. The first two authors then reviewed the categories and created a revised list of categories to analyse the content of the messages. We present the categorisation protocol in the supplementary material.

With this revised list at hand, another set of three research assistants codified the total of 893 messages. The purpose of this exercise was to identify which elements the participants exchanged during the chat, i.e. the topics they discussed and the way they did it. The following observations are based on the coding with the highest consensus among our coders. We are able to categorise 42% of the messages to the elements of effective communication we have discussed in this paper:

-

1.

4% of the messages relate to Problem Awareness and describe either (a) the tension between individual and group interest (3%), (b) the decline and effects of conditional cooperation (6%), or (c) former experiences from the baseline stage (79%) or (d) from previous experiments (12%).

-

2.

19% of the messages link to our Strategies element, (a) identifying potential strategies (41%) or (b) arguing for or against them (59%).

-

3.

10% link to our Agreement element and 9% link to our Ratification element.

-

4.

10% of the messages could be not categorised.

To identify the additional elements that are exchanged in Free Communication, which may cause open communication being more effective in maintaining cooperation than our structured process of information exchange, we take a closer look at the remaining 48% of messages which our coders categorised as “Other”. Within this category the coding team derived the following subcategories: (a) messages related to compliance and consequences (4%), (b) messages about insecurities and previous mistakes (7%), (c) nonsense (2%) and (d) social chit chat (87%). Thus, the majority of ‘other’ messages included primarily some sort of social chit chat. Messages in this category aimed to spread good vibes (smileys, good wishes, greetings, whooping, praise), or were classified as small talk (regarding the weather, study majors, jokes, or concerning the experiment: possibility to chat, anonymity of chat, remaining time).

Overall, the content analysis of the free chat shows that about half of the messages exchanged in Free Communication are related to our previously identified elements of effective communication. The other half, however, is largely used for social chit chat. With reference to the aforementioned debate about why communication improves cooperation, this social chit chat may have a function of its own, such as building a group identity (Dawes et al. 1988; Orbell et al. 1988) and/or allowing “individuals to increase (or decrease) their trust in the reliability of others” (Ostrom 1998, p. 13). Future research may want to examine how “social chit chat” links to these functions.

In this paper, we focused on the information content that promotes cooperation when shared. We saw that with the combined sequence of our interventions we reach similar levels as under Free Communication. This aspect becomes particularly interesting if we think about settings where the process of free communication may not be as clean and equal as in our small groups of relatively homogenous. We will explore this point further in the discussion.

5 Discussion and Conclusions

What information promotes cooperation in social dilemmas when it is exchanged in a communication process? In this paper, we have designed interventions resembling those elements of communication that have previously been identified as likely drivers of the positive impact of communication on cooperation. In an experimental setup, we tested how these interventions mimicking the potential elements of effective communication work individually and in combination in promoting cooperation in a social dilemma setting.

Our results suggest that is it is not enough to be informed about a problem or to examine potential strategies and the associated consequences individually, instead an exchange with the other interaction partners is needed to agree on a common strategy. We find that a nonbinding voting mechanism can help with this coordination on a commonly preferred strategy. The intervention facilitating an understanding of the available strategies and thereafter building an agreement upon them has thus the most positive impact on cooperation.

Combined with the interventions promoting problem awareness and ratification, high levels of cooperation were achieved. The observed pro-social behaviour is similar to what we observed when individuals could communicate freely via chat. In our view, there are two interesting ways how to read this result. On the one hand, we find that cooperation in our experiment reached high levels and could be sustained best when the group members could simply chat with each other; our mimicking interventions could not fully reach this combination of boosting and maintaining cooperation. We believe that this result suggests that there is more about communication than simply sharing information; communication also promotes social bonding; social chit may help to build trust and a shared group identity (Ostrom 1998; Sally 1995). But, we also see that with the combined sequence of our interventions we reached an increase that is not statistically different to the increase free communication triggered. This finding becomes interesting when we consider the environment in which the result of free communication was generated. In our experiment, a small group of relatively homogenous individuals (university students) interacted anonymously and with financial resources provided by us. In the real world, interacting actors may not have identical options at hand. They may be more heterogeneous in their endowments, action spaces, and preferences, and furthermore, the social dilemmas they face may be more complex. Free communication may not be sufficient to attain socially optimal outcomes when settings are complex (Ostrom et al. 1994, 1992; Schill et al. 2016). Cardenas et al. (2011), for example, illustrate this point in their lab-in-the-field experiment in Colombian and Kenyan watersheds. The problem was not that participants did not honour agreements commonly made in the communication phase, but they had difficulties to reach an agreement in the first place. In cases like this, structured and controlled facilitation may help to steer participants towards common agreements and cooperative patterns of interaction (Cardenas et al. 2004; Schill et al. 2016). Already the early work of Dawes et al. (1977) showed that when free communication is not goal-oriented and relevant to the task, it does not promote cooperation. The elements in our experiment ensure this task relevance and are controlled information-sharing mechanisms with which external actors can facilitate the process.

Structuring a communication process and/or managing the flow of information can have at least three effects. First, it avoids inefficiencies. For example, our interventions consisted only of the relevant information that was believed to improve cooperation. In an open communication phase, non-topic-related and redundant information may also be exchanged and potentially distract from the issue in question. Second, the risk of incorrect information being disseminated is lower when the flow of information is controlled. In an actual communication phase, incorrect or confusing information may be exchanged. And third, anyone can have a say if the structured communication process is designed accordingly. In an open forum with many actors, usually only dominant and powerful actors dare to speak out. Studies on participatory processes warn that loud and powerful actors may use the platform to pursue their own goals (Hickey and Mohan 2005; Reed 2008) and argue that external facilitation should prevent this.

The interventions in our experiment are similar to the measures that external actors can take to facilitate information exchange or to the role of facilitators in a participatory process. Thus, our analysis provides insights into which key elements should be considered when structuring and facilitating communication and information exchange in order to promote cooperation between actors.

Notes

We performed this literature review in 2017, by searching explicitly for papers that used free communication in a social dilemma experiment and which analysed the communication ex post. The selection of the literature was expert-led and complemented by a Google Scholar search and subsequent “snowballing”.

Payoff calculations are also mentioned in other papers. Isaac and Walker (1988), for example, state that group communication began many times with a search for the strategy that would bring the maximum yield to the group. Or, Ostrom et al. (1992) conclude that the participants in their experiment focused on two tasks; “calculat(ing) coordinated yield-improving strategies” and “determining the maximal yield available” (p. 410). Also, Cardenas et al. (2004) find that participants calculate the outcome of different strategies to clarify “to all group members that a lower level of aggregate extraction can increase individual earnings” (p. 275). And Brosig et al. (2003) state that a typical communication phase incorporated that “the payoffs for full cooperation were computed and, qualitatively or quantitatively, compared to payoffs that would follow after no cooperation. In addition, some groups computed the maximal individual payoff from free-riding.” (p. 225).

However, they also find that in 50 to 73 percent of all communication phases, depending on the treatment condition, participants demanded to maximize the group payoffs. Thus, it is one thing to call for maximizing group payoff and another to identify the maximizing strategy.

In the treatment combining all four elements (Problem Awareness + Strategy + Agreement + Ratification) participants needed on average 10 min to pass through the treatment stage. This is why the chat time in `Free Communication’ was 10 min.

We used a graph similar to the one used in Brandts et al. (2016)’s treatment.

Baseline contributions in the treatment conditions do not statistically differ from the contributions in the control group No Communication. However, among the treatment groups, we have to reject the Null hypothesis of uniformity between Prob. Awareness and Strategy (p = 0.08), Prob. Awareness and Free Comm. (p = 0.07), Strategy and PA + Strategies + Agreement (p = 0.06), and between PA + Strategies + Agreement and Free Communication (p = 0.05). Please note that these differences limit the magnitude of our effect rather than increasing it.

In this regression model we excluded the last two rounds. The effects, however, remain robust when w exclude alternatively only the last round or the last three rounds. The respective estimation results can be found in the appendix.

For the tests on the average treatment effects we consider model 1.

We consider here model 2. In model 3, in which the end rounds are not considered, the increase in Strategy is only significant at the 10% level.

The restart effect describes the fact that contributions increase simply because participants were told that something new starts (Chaudhuri 2018).

In the Full Set, we, on contrast, observe a steeper decay. This decrease may be triggered by disappointment resulting from broken promises.

Our estimates in models 2 and 3 may be biased, since we cannot consider the effects of time invariant omitted variables via fixed effects in the conditional Tobit model. For some of these unobserved factors we account for by including the average group contributions from the first stage as a control variable. Please note our main results are not based on these two models, neither are they affected by the time dynamic.

One group in No Communication and three groups in PA + Strategy + Agreement.

Average amount of rounds in which the groups in the respective treatment reached the social optimum: No Communication: 0.4 rounds, PA: 0.65 rounds, Strategy: 1.2 rounds, Strategy + Agreement: 2.75 rounds.

References

Balliet D (2009) Communication and cooperation in social dilemmas: a meta-analytic review. J Confl Resolut 54(1):39–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002709352443

Bicchieri C (2002) Covenants without swords: group identity, norms, and communication in social dilemmas. Ration Soc 14(2):192–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043463102014002003

Bochet O, Page T, Putterman L (2006) Communication and punishment in voluntary contribution experiments. J Econ Behav Organ 60(1):11–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2003.06.006

Brandts J, Rott C, Solà C (2016) Not just like starting over—leadership and revivification of cooperation in groups. Exp Econ 19:792–818. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-015-9468-6

Brosig J, Weimann J, Ockenfels A (2003) The effect of communication media on cooperation. German Econ Rev 4(2):217–241

Cardenas JC, Ahn TK, Ostrom E (2004) Communication and co-operation in a common-pool resource dilemma: a field experiment. In: Huck S (ed) Advances in understanding strategic behaviour. Palgrave Macmillan, pp 258–286. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230523371_12

Cardenas JC, Rodriguez LA, Johnson N (2011) Collective action for watershed management: field experiments in Colombia and Kenya. Environ Dev Econ 16(3):275–303. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355770X10000392

Chaudhuri A (2011) Sustaining cooperation in laboratory public goods experiments: a selective survey of the literature. Exp Econ 14(1):47–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-010-9257-1

Chaudhuri A (2018) Belief heterogeneity and the restart effect in a public goods game. Games. https://doi.org/10.3390/g9040096

Chaudhuri A, Paichayontvijit T, Smith A (2017) Belief heterogeneity and contributions decay among conditional cooperators in public goods games. J Econ Psychol 58:15–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2016.11.004

Dawes RM, McTavish J, Shaklee H (1977) Behavior, communication, and assumptions about other people’s behavior in a commons dilemma situation. J Pers Soc Psychol 35(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.35.1.1

Dawes RM, Van De Kragt AJC, Orbell JM (1988) Not me or thee but we: The importance of group identity in eliciting cooperation in dilemma situations: experimental manipulations. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 68(1–3):83–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-6918(88)90047-9

Fischbacher U, Gächter S (2010) Social preferences, beliefs, and the dynamics of free riding in public goods experiments. Am Econ Rev 100(1):541–556. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.100.1.541

Greiner B (2015) Subject pool recruitment procedures: organizing experiments with ORSEE. J Econ Sci Assoc 1(1):114–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40881-015-0004-4

Hendriks A (2012) SoPHIE-software platform for human interaction experiments. University of Osnabrück, Osnabrück

Hickey S, Mohan G (2005) Relocating participation within a radical politics of development. Dev Chang 36(2):237–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0012-155X.2005.00410.x

Isaac RM, Walker JM (1988) Communication and free-riding behavior: the voluntary contribution mechanism. Econ Inq 26(4):585–608. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7295.1988.tb01519.x

Janssen MA (2013) The role of information in governing the commons: experimental results. Ecol Soc 18(4):4. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-05664-180404

Kerr NL, Kaufman-Gilliland CM (1994) Communication, commitment, and cooperation in social dilemma. J Pers Soc Psychol 66(3):513–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.66.3.513

Kiesler CA (1971) The psychology of commitment: Experiments linking behavior to belief. Academic Press, New York

Koessler A-K, Page L, Dulleck U (2018) Promoting pro-social behavior with public statements of good intent. SSRN. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3184836

Koukoumelis A, Levati MV, Weisser J (2012) Leading by words: a voluntary contribution experiment with one-way communication. J Econ Behav Organ 81(2):379–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2011.11.007

Ledyard JO (1995) Public Goods: A Survey of Experimental Research. In: Roth JA, Kagel JH (eds) The handbook of experimental economics. Princton University Press, Princton

Lopez MC, Villamayor-Tomas S (2017) Understanding the black box of communication in a common-pool resource field experiment. Environ Sci Policy 68:69–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2016.12.002

Merriam Webster E (2019) Communication. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/communication. Accessed July 30, 2019

Orbell J, Dawes RM, van de Kragt A (1990) The limits of multilateral promising. Ethics 100(3):616–627. https://doi.org/10.1086/293213

Orbell J, van de Kragt AJC, Dawes RM (1988) Explaining discussion-induced cooperation. J Pers Soc Psychol 54(5):811–819. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.5.811

Ostrom E (1998) A behavioral approach to the rational choice theory of collective action. Am Polit Sci Rev 92(1):1–22. https://doi.org/10.2307/2585925

Ostrom E, Gardner R, Walker JM (1994) Rules, games, & common-pool resources. Rules, games, & common-pool resources. University of Michigan Press

Ostrom E, Walker J, Gardner R (1992) Covenants with and without a sword: self-governance is possible. Am Polit Sci Rev 86(2):404–417. https://doi.org/10.2307/1964229

Pavitt C, McFeeters C, Towey E, Zingerman V (2005) Communication during resource dilemmas: 1. Effects of different replenishment rates. Commun Monogr. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750500206482

Reed MS (2008) Stakeholder participation for environmental management: a literature review. Biol Cons 141(10):2417–2413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2008.07.014

Sally D (1995) Conversation and cooperation in social dilemmas: a meta-analysis of experiments from 1958 to 1992. Rationality and Society 7(1):58–92

Schill C, Wijermans N, Schlüter M, Lindahl T (2016) Cooperation is not enough—exploring social-ecological micro-foundations for sustainable common-pool resource use. PLoS ONE 11(11):e0165009. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157796

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Funding for this research was provided by the Alexander von Humboldt-Foundation in the framework of the Alexander von Humboldt-Professorship endowed by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, as well as by the Ministry of Science and Culture of Lower Saxony (Germany). We thank Imke Lüdecke, Lea Kolb, Dominik Kohl and Peter Naeve for their valuable support as research assistants, Fabian Thomas for his help in programming the experiment, and the participants of the LEEP conference 2019 as well as the 4th Workshop on Experimental Economics for the Environment in Münster for the discussion. Lastly, we would like to thank the editor and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive and helpful feedback.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix I

1.1 Sample Statistics

See Appendix Table 4.

1.2 Dynamic development within groups

See Appendix Tables 5 and 6 and Figs. 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10.

Appendix II–Experimental Material

2.1 Problem Awareness

2.2 Identification of Strategies

In the visualisation of the three strategies, namely the socially optimal strategy, the self-interested strategy and the laissez-faire strategy, we offered corresponding scenarios which illustrated the consequences in terms of individual and group payouts. Scenario A showed that when all group members contributed their entire endowment, a total payout of 128 points could be achieved and the payout for each group member would be 32 points. Scenario B depicted that when all group members contribute nothing, the total payout would be 80 points and the corresponding individual payout 20 points. For the laissez-faire strategy, we presented three scenarios. Scenario C.1 elaborated on the incentive to free-ride. It showed that if three group members contributed their entire endowment and one group member contributed nothing, the total payout would be116 points. The group members contributing would receive 24 points while the free-rider would receive 44 points. Hence, the scenario also showed that even when a free-rider was present, it was still beneficial for the other group members to contribute their entire endowment. Scenario C.2 depicted that a moderate cooperation of all group members would be also still be beneficial compared to no cooperation. It showed that when all group members contributed 10 points, the total payout would be 104 points and each group member would receive 26 points. Lastly, scenario C.3 adopted the same level of contribution to the public good as C.2, but unequally distributed among the group members. In the scenario, one group member contributed 20, another 13, the third 7 points while the last group member contributes 0 points. Hence, the total payout reached 104 points and the four group members receives 16, 23, 29, 36 points, respectively.

The labels of all three strategies A, B, C and their scenarios A.1, B.1, C.1, C.2, C.3 were randomized among subjects as well as groups. Thus, the same strategy labelled as A for one player, may have been strategy A, B or C for other players. Consistently, the order in which the strategies were presented was randomized as well. For the sake of a better understanding, we however refer to the strategies by A, B and C in the paper as presented above (see Appendix Fig. 13.

2.3 Agreement (Voting)

2.4 Ratification

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Koessler, AK., Ortiz-Riomalo, J.F., Janke, M. et al. Structuring Communication Effectively—The Causal Effects of Communication Elements on Cooperation in Social Dilemmas. Environ Resource Econ 79, 683–712 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-021-00552-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-021-00552-2