Published online Mar 26, 2021. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v13.i3.208

Peer-review started: October 6, 2020

First decision: December 24, 2020

Revised: January 8, 2021

Accepted: February 15, 2021

Article in press: February 15, 2021

Published online: March 26, 2021

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI), which refers to liver damage caused by a drug or its metabolites, has emerged as an important cause of acute liver failure (ALF) in recent years. Chemically-induced ALF in animal models mimics the pathology of DILI in humans; thus, these models are used to study the mechanism of potentially effective treatment strategies. Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) possess immunomodulatory properties, and they alleviate acute liver injury and decrease the mortality of animals with chemically-induced ALF. Here, we summarize some of the existing research on the interaction between MSCs and immune cells, and discuss the possible mechanisms underlying the immuno-modulatory activity of MSCs in chemically-induced ALF. We conclude that MSCs can impact the phenotype and function of macrophages, as well as the differentiation and maturation of dendritic cells, and inhibit the proliferation and activation of T lymphocytes or B lymphocytes. MSCs also have immuno-modulatory effects on the production of cytokines, such as prostaglandin E2 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha-stimulated gene 6, in animal models. Thus, MSCs have significant benefits in the treatment of chemically-induced ALF by interacting with immune cells and they may be applied to DILI in humans in the near future.

Core Tip: Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is a crucial cause of acute liver failure (ALF). Although mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) have not been applied to DILI in clinical trials, their efficacy has been proven in various animal models of chemically-induced ALF. Immune system disorders play key roles in chemically-induced ALF, and MSCs are able to regulate the immune system through soluble factors and cell-to-cell contact, and eventually improve liver damage. We, herein, discuss the immunomodulatory properties of MSCs in different animal models that mimic the pathology of DILI in humans.

- Citation: Zhou JH, Lu X, Yan CL, Sheng XY, Cao HC. Mesenchymal stromal cell-dependent immunoregulation in chemically-induced acute liver failure. World J Stem Cells 2021; 13(3): 208-220

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-0210/full/v13/i3/208.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4252/wjsc.v13.i3.208

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI), the most common cause of acute liver failure (ALF) in developed countries, accounts for approximately 50% of ALF cases[1]. In patients with hypersensitivity or reduced tolerance due to special constitutions, the immune-privileged state of the liver can be disrupted by drugs and chemicals or their metabolites, such as reactive intermediate species[2], resulting in unbalanced immune cell infiltration and liver injury[3].

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) are widely studied adult pluripotent stem cells. They possess not only all of the common characteristics of stem cells but also immunomodulatory properties. They have been extensively researched due to their wide range of sources and easy availability. Since the first MSC transplantation in a pediatric patient experiencing grade IV treatment-refractory acute graft vs host disease (GVHD) in 2004[4], there have been an increasing number of studies demonstrating that MSC transplantation can effectively modulate the immune system in several immune-related disorders. In addition to the ability of MSCs to migrate to damaged liver sites and undergo proliferation and differentiation into hepatocytes, the therapeutic mechanism of MSCs in ALF mainly depends on their potential immunomodulatory nature[5].

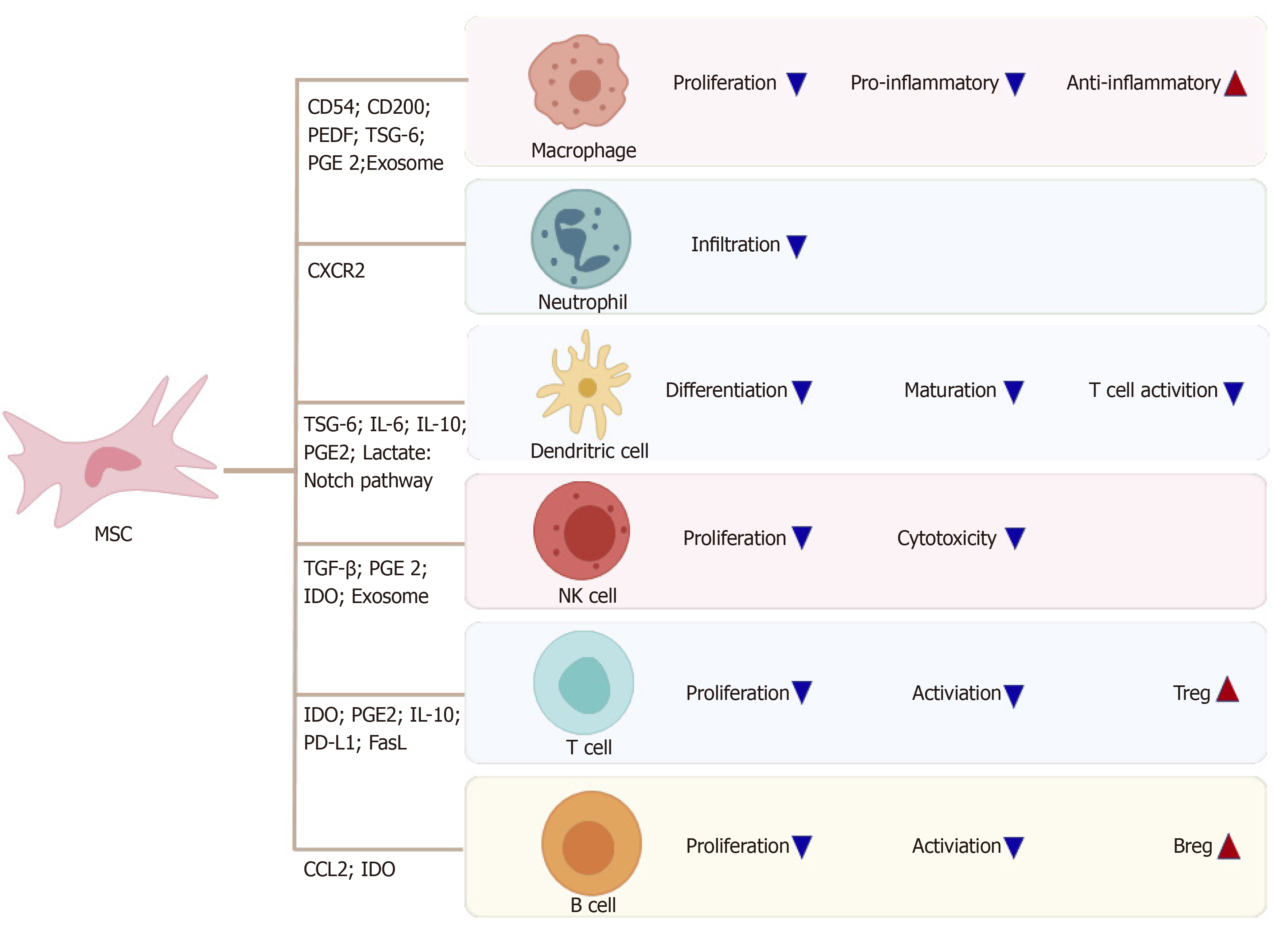

The main immune cells consist of neutrophils, T cells, B cells, natural killer (NK) cells, monocytes/macrophages, and dendritic cells (DCs). MSCs alter macrophages from a regularly activated (M1) phenotype to an either/or activated (M2) phenotype, resulting in reduced secretion of the proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and interleukin (IL)-1, and increased secretion of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, which to a great extent is dependent on cell-to-cell contact or soluble factors, such as prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), and TNF-α-stimulated gene 6 (TSG-6)[6]. MSCs impact two stages of DCs: differentiation and maturation. When co-cultured with MSCs, DC precursors and immature DCs express lower levels of major histocompatibility complex class II (MHCII) and costimulatory molecules cluster of differentiation (CD) 86, CD80, and CD40, which result in a weakened ability to stimulate T cell proliferation. However, the immunosuppressive capacity of MSCs in mature DCs remains controversial[7].

Several studies have shown the inhibitory effects of MSCs on T cell activation, proliferation, and differentiation to T helper 17 (Th17) cells through PGE2, programmed cell death protein 1 (referred to as PD-1), and IL-10[8]. Additionally, MSCs can stimulate the generation and proliferation of immunosuppressive regulatory T cells (Tregs)[9]. Similarly, MSCs suppress the proliferation, activation, and antibody production ability of B cells and induce the B regulatory cells (Bregs)[10].

MSCs have been studied as a prospective therapy for the treatment of DILI and ALF due to their immunomodulatory ability. Several animal models of chemically-induced ALF have been used to study the mechanisms of DILI and the mechanisms of potentially novel therapies[3]. MSCs can alleviate ALF by interacting with different immune cells because the main pathogenic immune cells differ in these animal models, and these discoveries in animal models will contribute to the clinical application of MSC-based strategies for the treatment of human DILI.

In this review, we summarize a number of existing studies on the interplay of MSCs and the immune system, and discuss some possible mechanisms underlying the immunomodulatory ability of MSCs in chemically-induced ALF. MSC-based therapy may be applied to DILI in humans in the near future.

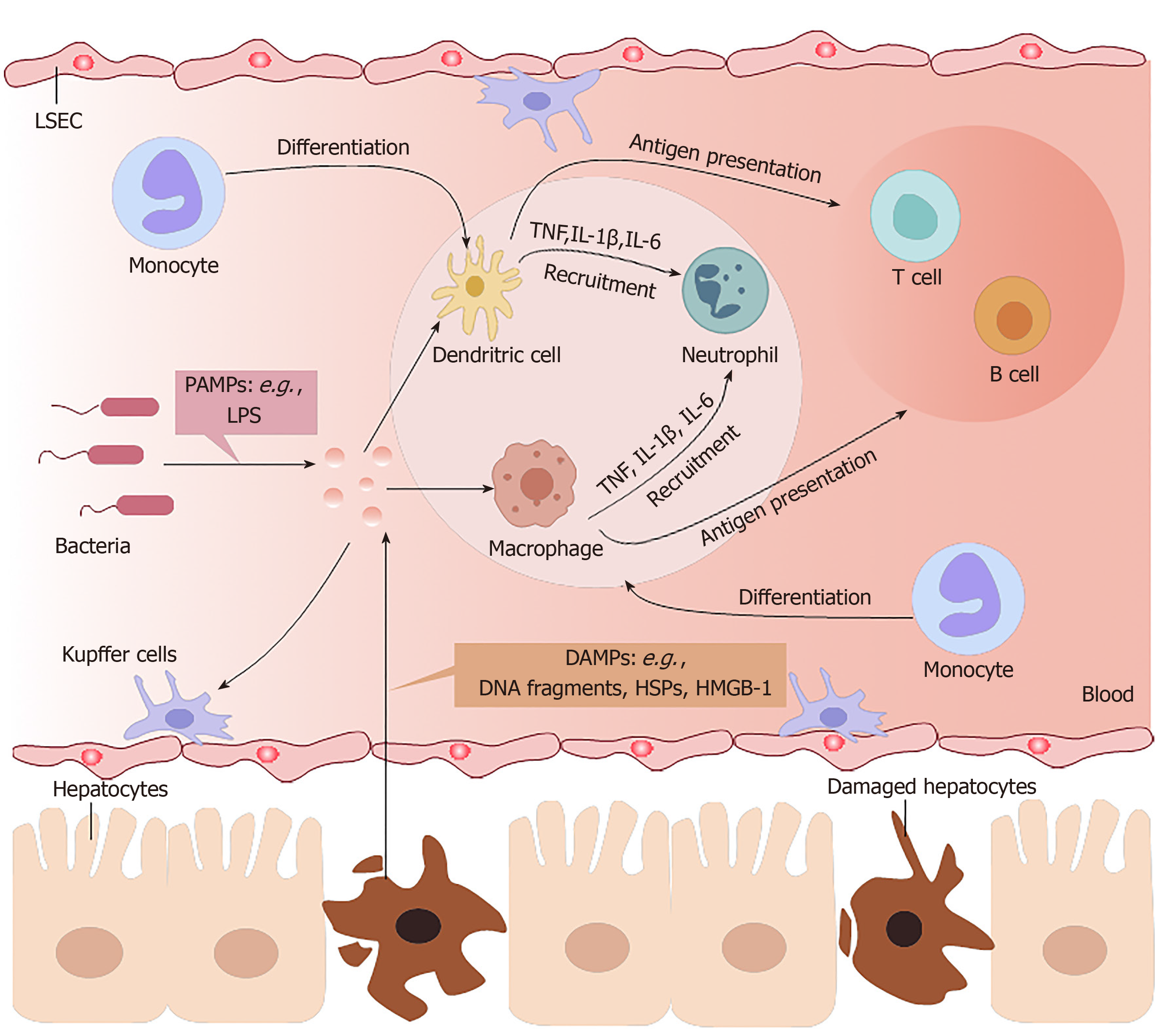

The liver is an organ that is dominated by metabolic functions. It is inevitably exposed to the metabolites of various foods or drugs in the blood from the portal vein, which requires this organ to have high immune tolerance and self-repair abilities[2]. Chemically-induced liver injuries refer to liver damage caused by chemical hepatotoxic substances, including alcohol, drugs, traditional Chinese medicines, chemical poisons from food, and organic and inorganic poisons in industrial production. On the one hand, the immune system of the liver has to tolerate the heavy antigenic load of daily food residues from the portal vein in a healthy state; on the other hand, it must respond efficiently to numerous viruses, bacteria, parasites, and chemical hepatotoxic substances[11]. Excessive inflammation often contributes to morbidity and mortality in chemically-induced ALF (Figure 1).

In DILI, necrotic hepatocytes show many damage-associated molecular patterns (referred to as DAMPs), such as high-mobility group box-1 protein, DNA fragments, and heat shock proteins[12], and these factors can be identified by Toll-like receptors (commonly known as TLRs) on innate immune cells. Then, proinflammatory factors recruit inflammatory immune cells into the liver, activating them to remove necrotic cell debris[13].

Liver macrophages mainly include two cell types: resident Kupffer cells and infiltrating monocyte-derived macrophages. Although of different cellular origins, both types of macrophages can phagocytose microorganisms and metabolic waste in liver sinusoids. The numbers of liver macrophages become greatly increased in any type of liver injury, due to the self-renewal ability of Kupffer cells and the infiltration of monocyte-derived macrophages[14]. In the early stages of liver injury, Kupffer cells recognize DAMPs derived from damaged hepatocytes and then secrete several proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines to attract neutrophils, NK cells, and bone-marrow-derived monocytes to the regions of inflammation[15]. Ly6C+ monocytes and Ly6C- monocytes exist in the blood of mice, and can differentiate into hepatic macrophages. Infiltrating Ly6C+ monocytes promote inflammation and induce organ impairment, but eventually maturate with the downregulation of Ly6C expression, at which point they acquire the ability to restore liver integrity[16].

Neutrophils are the first-line immune cells that have the fastest response when inflammation occurs. However, uncontrolled neutrophil infiltration and activation lead to excessive inflammation in chemically-induced liver injuries. The expression levels of C-X-C motif chemokine ligand (referred to as CXCL) 1, IL-6, TNF-α, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in the injured liver are significantly increased to regulate the infiltration and activation of neutrophils[17]. Tissue-resident phagocytes, including macrophages and DCs, release a variety of proinflammatory mediators and establish a chemoattractant gradient, triggering neutrophil recruitment into tissues. Neutrophils express receptors (G protein-coupled receptor, Fc-receptors, adhesion molecules, TLRs, C-type lectins) that can recognize these signals and then release granules (myeloperoxidase), generate reactive oxygen species, and form neutrophil extracellular traps[18,19].

DCs in ALF engage in the innate immune response involving macrophages and neutrophils, with antigen recognition by pattern-recognition receptors. However, the most important effect of DCs is initiation of the adaptive immune response. DCs reside in organs such as the liver as immature cells, which are very effective at antigen recognition, capture and processing, and then circulate in the blood or lymph fluid to peripheral immune organs where they can achieve terminal maturation with the ability of efficient antigen presentation as well as activation of T cells[20].

In the healthy state, hepatocytes express MHC-I, which binds to inhibitory receptors on NK cells, preventing NK cell activation[21]. In contrast, infected hepatocytes lacking MHC-I can be recognized and eliminated by NK cells[22].

Contrary to innate immune responses, which induce acute liver injury (ALI) in experimental animal models[13], adaptive immune responses play an undefined secondary role in DILI[23]. In homeostasis, liver sinusoidal endothelial cells and Kupffer cells constitutively express IL-10, prostaglandins, TNF-α, and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) to expand Tregs, attenuate T cell activation, and induce liver immune tolerance[12]. In some ALI models induced by some special types of drugs or chemicals, T cells are important. Yu et al[24] found that IL-1β is upregulated in the AAGL (Agrocybe aegerita galectin) model and is crucial to recruit T cells from peripheral blood into the injured liver; treatment with IL-1β antibody can significantly alleviate hepatocyte damage. The possible mechanism may be inhibition of p38 or nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) signaling pathways and subsequently reduced infiltration of T cells into the liver. Heymann et al[25] applied a concanavalin A (Con A)-induced liver injury model to mimic immune reactions observed in humans, trigger an inflammatory cascade by activating resident Kupffer cells, initiate neutrophil infiltration, and increase CD4+ T cell infiltration and activation[26]. Although Tiegs et al[27] showed that CD4+ T cells play a more critical role than CD8+ T cells in Con A-induced liver injury in wild-type mice, CD8+ T cells played an important role in T cell-transferred Rag2-knockout mouse (in which T cells cannot mature) challenged with Con A. Both IL-33 released by the injured liver and perforin secreted by CD8+ T cells were crucial components in their study.

Quiescent MSCs display immune homeostatic features biased towards suppression. When MSCs are induced by various proinflammatory cytokines, these immuno-suppressive properties can be considerably enhanced, resulting in polarization to immunosuppressive phenotypes of MSCs. IDO and inducible nitric oxide synthase (referred to as iNOS) are the key to the immune regulatory functions of MSCs, with a series of potential complementary suppressor pathways, including heme oxygenase-1, soluble human leukocyte antigen-G5, TGF-β, PGE2, galectin, and TSG-6[28]. MSCs possess a pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory phenotype by contacting immune cell responses in different situations, and regulate the immune response by secreting soluble factors or direct cell contact[6].

MSCs can regulate the proliferation and activation of Kupffer cells, macrophages, DCs, neutrophils, and NK cells (Figure 2). MSCs reportedly transfer to injury sites in response to large amounts of inflammatory factors, such as IL-6 and TNF-α secreted by activated Kupffer cells[29]. MSCs, in turn, inhibit the phenotype transition of activated Kupffer cells to M1 and stimulation of the NF-κB pathway in lipopolysaccharide (commonly known as LPS)-treated Kupffer cells[30]. Several studies have revealed the mechanism by which MSCs cause immunosuppression via the interaction of macrophages. MSCs can interact directly and physically with innate immune cells. Upregulated CD54 on human MSCs (referred to here as hMSCs) co-cultured with M1 macrophages in an in vitro co-culture system increased IDO activity and inhibited the proliferation of T cells[31]. Similarly, upregulated CD200 on mouse bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) in contact with M1 macrophages can also enhance the immunotherapeutic effects of MSCs to reprogram proinflammatory macrophages[32]. On the other hand, soluble factors secreted by MSCs can contribute to the immunoregulatory properties of MSCs. Corneal-derived MSCs can secrete pigment epithelium-derived factor and then modulate the immunophenotype and angiogenic function of macrophages[33]. TSG-6 and PGE2 secreted by MSCs have also been widely studied, due to their immunoregulatory effects on MSCs and macrophages[32,34].

In addition, MSC-derived exosomes, which are rich in proteins, mRNAs, and microRNAs (designated as miRs), have been used as a therapy for liver diseases in recent years. In a study of experimental autoimmune hepatitis, BMSC-derived exosomes, which are rich in miR-223, effectively alleviated liver injury by downregulating formation of the NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (referred to as NLRP3) inflammasome[35]. In another study, miR-17 derived from adipose tissue-derived MSC (AMSC)-derived exosomes was shown to ameliorate LPS/D-galactosamine-induced ALI by inhibiting activation of the TXNIP/NLRP3 inflammasome of macrophages[36]. MSCs can limit neutrophil recruitment or infiltration and inhibit neutrophil activation to prevent an excessive inflammatory response. MSCs ameliorate the hepatic inflammatory response by reducing the release of neutrophil chemoattractant CXCL2 and attenuating neutrophil chemotaxis via downregulation of C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 2 expression in neutrophils[37]. In a septic mouse model, MSCs optimally balanced the distribution of circulating and tissue-infiltrated neutrophils, maximizing bacterial killing and minimizing liver injury[34].

Many studies have focused on the effects of MSCs on DCs in vitro, especially through soluble factors. One showed that TSG-6 secreted by mouse BMSCs suppressed the maturation and activation of DCs by inactivating mitogen-activated protein kinase and NF-κB signaling pathways[38]. In addition, IL-6 reportedly participates in the immune regulation mechanism mediated by the murine MSC line via inhibition of DCs[39]. Regarding hMSCs, Spaggiari et al[40] demonstrated that human BMSCs can secrete PGE2 to inhibit differentiation of monocyte-derived DCs. Selleri et al[41] showed that human umbilical-cord-derived MSCs can secrete lactate to induce granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor/IL-4-treated monocytes to differentiate into M2 macrophages rather than DCs by metabolic reprogramming. A study by Liu et al[42] showed that MSCs derived from mouse embryonic fibroblasts can induce a type of novel regulatory DCs that express low levels of CD11c and Ia and are phenotypically different from immature and mature DCs via IL-10.

In addition, direct cell contacts are as important as soluble molecules in MSC/DC interactions. hMSCs can inhibit the proliferation ability and differentiation capability of CD34+ hemopoietic progenitor cells into interstitial DCs but cannot inhibit maturation of CD34+ hemopoietic progenitor cell-derived DCs, and the inhibitory effect is associated with the Notch pathway[43]. Cahill et al[44] demonstrated that mouse MSC induction of functional tolerogenic DCs that can induce Tregs in vitro requires Notch signaling. This hypothesis was confirmed in an animal model treated with Jagged-1 knockdown MSCs. In another study, mature DCs cocultured with MSCs expressing Jagged-2 acquired tolerogenic properties[45]. MSCs can influence the proliferation capacity, cytokine release, phenotypic conversion, and cytotoxicity of IL-2-induced NK cells[46]. The mechanism may include TGF-β[47], PGE2[48], IDO[49] and exosomes[50]. Moreover, NK cells can stimulate MSC recruitment by secreting neutrophil-activating peptide 2[51], and activated NK cells can efficiently lyse MSCs[46].

MSCs can inhibit proliferation, activation, and differentiation of T cells, induce apoptosis of T cells and induce recruitment of Tregs. MSCs can also induce cell cycle arrest by downregulating cyclin D2 and upregulating p27kip1 in T cells, resulting in division anergy of activated T cells[52]. Of note, MSCs can inhibit T cell function by inducing apoptosis of activated T cells. Plumas et al[53] showed that this apoptosis can be associated with transformation of tryptophan to kynurenine by IDO expressed by MSCs in the presence of IFN-γ. Akiyama et al[54] revealed that BMSCs may trigger apoptosis of transient T cells through the Fas ligand (FasL)-dependent pathway, and that apoptotic T cells can induce production of TGF-β in macrophages, thereby upregulating Tregs. In some experiments in vitro, MSCs were shown to inhibit allogeneic T cell responses in mixed lymphocyte reactions by IDO after MSCs were activated by IFN-γ[55]. Recently, MSCs were shown to inhibit activation of CD4+ T cells and reduce secretion of IL-2 via PD-1 ligands[56].

Several investigators have highlighted that MSCs can effectively inhibit Th17 differentiation. Duffy et al[57] demonstrated that this inhibition requires cyclooxygenase-2 induction, which is dependent on cell contact, leading to direct Th17 inhibition by PGE2. Qu et al[58] also showed that MSCs inhibit Th17 cell differentiation, and suggested that increased secretion of IL-10 may play a role. One important aspect of the immunomodulatory effect of MSCs is the recruitment and influence of Tregs[59]. MSCs can reinforce the regulatory function of CD8+CD28- Treg cells by increasing expression of IL-10 and FasL[60]. They can also induce cell cycle arrest in the G0/G1 phase instead of induction of B-cell apoptosis in a soluble factor-dependent manner[61]. Furthermore, MSCs inhibit proliferation and activation of B cells by modifying the phosphorylation levels of the extracellular signal-related kinase 1/2 or p38 pathways[62]. Rafei et al[63] clarified that MSC-derived chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (referred to as CCL2) can suppress secretion of immunoglobulin (referred to as Ig) in plasma cells and induce proliferation of plasmablasts, leading to IL-10-mediated blockade via inactivation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (referred to as STAT3) and induction of paired box 5 in vitro. MSCs can enhance the survival and proliferation rates of CD5+ Bregs in an IDO-dependent manner, increasing IL-10 expression and ameliorating refractory, chronic GVHD[10]. Similarly, AMSCs reduce plasmablast formation or induce IL-10-producing CD19+CD24highCD38high B cells[64]. Park et al[65] elucidated the effect of human AMSCs on the proliferation of Bregs in an animal model of systemic lupus erythematosus.

Viral infection remains the main cause of ALF in developing countries, whereas DILI is more common in developed countries[1]. DILI accounts for 50% of ALF cases in the United States[66] and Europe, and the main drug responsible is acetaminophen[67]. Several animal models induced by chemical substances have been used to study the mechanisms of ALF[3]. Chemical substances, such as Con A, α-galactosylceramide (commonly known as α-GalCer) and carbon tetrachloride (CCl4), have been used in ALF animal models in which MSCs have been demonstrated to alleviate the symptoms of liver injury effectively; although, the mechanisms are complex and not fully understood (Table 1).

| Species of MSCs | Source | Dose | Model | Reagents for model | Immune cell | Mechanism | Effect | Ref. |

| Mouse | Bone marrow | 5 × 105 | Mouse | α-GalCer | Treg | Increase the population of Tregs and their capacity to produce IL-10; attenuate hepatotoxicity of NKT cells in an IDO-dependent manner | Attenuate ALF | Gazdic et al[9] |

| Mouse | Bone marrow | 1 × 106 | Mouse | TAA | Macrophage/T cell | Inhibit macrophage infiltration; reduce Th1 and Th17 cells and increase Tregs | Ameliorate FHF and reduces mortality | Huang et al[78] |

| Rat | Bone marrow | 1 × 107 | Rat | D-GalN/LPS | Neutrophil | Reduce the number and activity of neutrophils in both peripheral blood and liver | Improve the liver function | Zhao et al[77] |

| Mouse | Bone marrow | 5 × 105 | Mouse | Con A/α-GalCer | NKT cell | Attenuate the cytotoxicity and capacity of liver NKT in an iNOS- and IDO-dependent manner | Attenuate ALF | Gazdic et al[72] |

| Mouse | Bone marrow | 5 × 105 | Mouse | CCl4/a-GalCer | NKT cell | Reduce IL-17-producing NKT cells and increase the presence of IL-10-producing NKT regulatory cells in an IDO-dependent manner | Attenuate ALF | Milosavljevic et al[74] |

| Mouse | Adipose tissue | AMSC-Exo, 400 μg | Mouse | LPS/D-GalN | Macrophage | Reduce NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages by targeting TXNIP | Attenuate ALF | Liu et al[36] |

Volarevic et al[68-70] conducted several studies on the immunoregulation of MSCs in ALF induced by Con A. Their previous studies showed that Con A-induced ALF is an excellent murine model of immune-mediated liver injury. CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, NK T (NKT) cells, NK cells, and macrophages are reportedly related to this model and can be transferred to injured liver sites and secrete many cytokines. Meanwhile, the authors confirmed the efficacy of AMSCs for ALF induced by Con A[71]. Gazdic et al[72] researched the MSC-NKT cell interaction in Con A- and α-GalCer-induced murine models of ALF, and elucidated that MSCs protect hepatocytes from the cytotoxicity of liver NKT cells by attenuating their ability to produce inflammatory factors, such as TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-4, in an iNOS- and IDO-dependent manner. In a recent study of α-GalCer-induced ALF, Ito et al[73] demonstrated that MSCs can increase IL-10 in Tregs, which in turn, attenuates the hepatotoxicity of liver NKT cells[9].

Milosavljevic et al[74] revealed another mechanism of MSC-NKT cell interaction, specifically that MSCs can attenuate CCl4-induced ALF by downregulating IL-17 in liver NKT cells. Their findings highlighted the reduction of liver NKT cell cytotoxicity and the critical importance of increased regulatory cells (Tregs and NK Tregs) in MSC-mediated attenuation of ALF, indicating the importance of MSC-induced regulatory cells as a prospective cell-based ALF therapy. Liu et al[75] demonstrated through a high-dimensional analysis that MSCs significantly ameliorated CCl4-induced ALF and regulated the immune system of the liver. In this model, MSCs regulated different immune cells in two phases. During the injury stage, MSCs reduced the numbers of Ly6ClowCD8+ resident memory T cells (referred to as TRM) cells, conventional NK cells, and IgM+IgD+ B cells but increased the quantity of immunosuppressive monocyte-derived macrophages. During the recovery stage, MSCs enhanced the retention of Ly6ClowCD8+ TRM cells and maintained the immunosuppressive ability of monocyte-derived macrophages. To reveal alterations in immune cell subsets of CCl4-induced ALF after MSC transplantation, the authors detected the metabolomic profile of the immune system. Using high-performance chemical isotope labeling liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry, they confirmed 256 metabolites as candidate biomarkers of the immune response in CCl4-induced ALF animal models, and 114 metabolites as candidate biomarkers of the immune response after MSC transplantation. However, the potential immunomodulatory role of metabolites needs further investigation[76]. MSCs have exhibited positive effects in a rat model of D-GalN/LPS-induced ALF by inhibiting the recruitment and activity of neutrophils. Compared with monotherapy, combination of MSCs and anti-neutrophil serum can inhibit cell apoptosis more efficiently, ameliorate liver function, and reduce the mortality rate[77]. In a mouse model of thioacetamide-induced ALF, both MSCs and MSC-conditioned medium treatment reduced the incidence of death. MSC-treated livers showed less hepatocellular apoptosis and more liver regeneration, as well as downregulation of macrophage infiltration and alteration of CD4+ T cells to an anti-inflammatory phenotype[78].

Increasing evidence has shown that MSCs have immunosuppressive capacities to regulate the function of immune cells in ALI as well as promote internal environmental homeostasis in chemically-induced ALF. MSCs can interact with both innate and adaptive immune systems via cell-to-cell interactions and the paracrine pathway, coordinating an integrated response to liver injury and preventing hepatocyte necrosis. However, there are still some deficiencies in the research of MSC-dependent immunoregulation in chemically-induced ALF. For example, the pathogenesis of liver injury models and the role of the immune system are still unclear. There has not been enough extensive and in-depth research on MSC-dependent immunoregulation in chemically-induced ALF.

Different sources and different pretreated MSCs have varying therapeutic effects on liver injury. To date, there is no uniform standard for MSC applications in animal models[79]. Thus, the results from different studies cannot be compared or repeated in different laboratories under different conditions[80].

MSCs have been widely studied for their differentiation and immunomodulation abilities. However, in one study, researchers focused on a single capability of MSCs, ignoring comparisons of their various capabilities. Future studies are needed to determine which MSC capability dominates.

There have been no clinical trials on DILI treated by MSCs. Clinical trials on MSC treatment are often applied to chronic diseases such as GVHD, diabetes, and malignant blood disease[81]. MSCs are rarely used in DILI, which has a rapid onset and high mortality rate, and more conventional and conservative treatments tend to be used. Clinical trials can be conducted only if the efficacy and safety of MSCs are supported by sufficient research. The two main obstacles to translating the results from animal experiments into clinical practice are that the pathogenicity of ALI caused by clinical drugs differs from that of animal models[6], and that the immune system of animals, such as mice, is different from that of humans, so the results demonstrated in mice are not necessarily applicable to humans. Possible solutions to these issues are to verify the results obtained in animal experiments in organoids derived from human liver, and to identify animal models with similar pathogenicity to DILI in humans. Further studies are needed to reveal the therapeutic mechanisms of MSCs.

In conclusion, MSC transplantation can efficiently reduce the high mortality rate of chemically-induced ALF and may become a prospective therapy in clinical practice. More prospective randomized studies are needed to ensure the therapeutic effects of MSCs.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver, No. MN-2162.

Specialty type: Cell and tissue engineering

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cao T, Philips CA S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Bernal W, Wendon J. Acute liver failure. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2525-2534. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 736] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 747] [Article Influence: 67.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Gu X, Manautou JE. Molecular mechanisms underlying chemical liver injury. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2012;14:e4. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 174] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gazdic M, Arsenijevic A, Markovic BS, Volarevic A, Dimova I, Djonov V, Arsenijevic N, Stojkovic M, Volarevic V. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Dependent Modulation of Liver Diseases. Int J Biol Sci. 2017;13:1109-1117. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 47] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Le Blanc K, Rasmusson I, Sundberg B, Götherström C, Hassan M, Uzunel M, Ringdén O. Treatment of severe acute graft-versus-host disease with third party haploidentical mesenchymal stem cells. Lancet. 2004;363:1439-1441. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2044] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1970] [Article Influence: 98.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hu C, Li L. Improvement of mesenchymal stromal cells and their derivatives for treating acute liver failure. J Mol Med (Berl). 2019;97:1065-1084. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bernardo ME, Fibbe WE. Mesenchymal stromal cells: sensors and switchers of inflammation. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:392-402. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 903] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 971] [Article Influence: 97.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ðokić JM, Tomić SZ, Čolić MJ. Cross-Talk Between Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells and Dendritic Cells. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2016;11:51-65. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Haddad R, Saldanha-Araujo F. Mechanisms of T-cell immunosuppression by mesenchymal stromal cells: what do we know so far? Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:216806. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 117] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gazdic M, Markovic BS, Arsenijevic A, Jovicic N, Acovic A, Harrell CR, Fellabaum C, Djonov V, Arsenijevic N, Lukic ML, Volarevic V. Crosstalk between mesenchymal stem cells and T regulatory cells is crucially important for the attenuation of acute liver injury. Liver Transpl. 2018;24:687-702. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Peng Y, Chen X, Liu Q, Zhang X, Huang K, Liu L, Li H, Zhou M, Huang F, Fan Z, Sun J, Ke M, Li X, Zhang Q, Xiang AP. Mesenchymal stromal cells infusions improve refractory chronic graft vs host disease through an increase of CD5+ regulatory B cells producing interleukin 10. Leukemia. 2015;29:636-646. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 133] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Doherty DG. Immunity, tolerance and autoimmunity in the liver: A comprehensive review. J Autoimmun. 2016;66:60-75. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 202] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Iorga A, Dara L. Cell death in drug-induced liver injury. Adv Pharmacol. 2019;85:31-74. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jaeschke H, Williams CD, Ramachandran A, Bajt ML. Acetaminophen hepatotoxicity and repair: the role of sterile inflammation and innate immunity. Liver Int. 2012;32:8-20. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 316] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 333] [Article Influence: 27.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Krenkel O, Tacke F. Liver macrophages in tissue homeostasis and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17:306-321. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 621] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 803] [Article Influence: 114.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Luedde T, Schwabe RF. NF-κB in the liver--linking injury, fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:108-118. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 836] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 942] [Article Influence: 72.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tacke F, Zimmermann HW. Macrophage heterogeneity in liver injury and fibrosis. J Hepatol. 2014;60:1090-1096. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 600] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 700] [Article Influence: 70.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wang XZ, Zhang SY, Xu Y, Zhang LY, Jiang ZZ. The role of neutrophils in triptolide-induced liver injury. Chin J Nat Med. 2018;16:653-664. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Futosi K, Fodor S, Mócsai A. Neutrophil cell surface receptors and their intracellular signal transduction pathways. Int Immunopharmacol. 2013;17:638-650. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 355] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 412] [Article Influence: 37.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Alvarenga DM, Mattos MS, Araújo AM, Antunes MM, Menezes GB. Neutrophil biology within hepatic environment. Cell Tissue Res. 2018;371:589-598. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Szabo G, Mandrekar P, Dolganiuc A. Innate immune response and hepatic inflammation. Semin Liver Dis. 2007;27:339-350. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 138] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Morvan MG, Lanier LL. NK cells and cancer: you can teach innate cells new tricks. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:7-19. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 712] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 774] [Article Influence: 96.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Liu P, Chen L, Zhang H. Natural Killer Cells in Liver Disease and Hepatocellular Carcinoma and the NK Cell-Based Immunotherapy. J Immunol Res. 2018;2018:1206737. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 61] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kim SH, Naisbitt DJ. Update on Advances in Research on Idiosyncratic Drug-Induced Liver Injury. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2016;8:3-11. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yu W, Lan X, Cai J, Wang X, Liu X, Ye X, Yang Q, Su Y, Xu B, Chen T, Li L, Sun H. Critical role of IL-1β in the pathogenesis of Agrocybe aegerita galectin-induced liver injury through recruiting T cell to liver. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2020;521:449-456. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Heymann F, Hamesch K, Weiskirchen R, Tacke F. The concanavalin A model of acute hepatitis in mice. Lab Anim. 2015;49:12-20. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 171] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Elshal M, Abu-Elsaad N, El-Karef A, Ibrahim T. Retinoic acid modulates IL-4, IL-10 and MCP-1 pathways in immune mediated hepatitis and interrupts CD4+ T cells infiltration. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019;75:105808. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tiegs G, Hentschel J, Wendel A. A T cell-dependent experimental liver injury in mice inducible by concanavalin A. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:196-203. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 812] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 852] [Article Influence: 26.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Krampera M, Galipeau J, Shi Y, Tarte K, Sensebe L; MSC Committee of the International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT). Immunological characterization of multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells--The International Society for Cellular Therapy (ISCT) working proposal. Cytotherapy. 2013;15:1054-1061. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 297] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 311] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Yang X, Liang L, Zong C, Lai F, Zhu P, Liu Y, Jiang J, Yang Y, Gao L, Ye F, Zhao Q, Li R, Han Z, Wei L. Kupffer cells-dependent inflammation in the injured liver increases recruitment of mesenchymal stem cells in aging mice. Oncotarget. 2016;7:1084-1095. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Liang X, Li T, Zhou Q, Pi S, Li Y, Chen X, Weng Z, Li H, Zhao Y, Wang H, Chen Y. Mesenchymal stem cells attenuate sepsis-induced liver injury via inhibiting M1 polarization of Kupffer cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2019;452:187-197. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Espagnolle N, Balguerie A, Arnaud E, Sensebé L, Varin A. CD54-Mediated Interaction with Pro-inflammatory Macrophages Increases the Immunosuppressive Function of Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2017;8:961-976. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 61] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Li Y, Zhang D, Xu L, Dong L, Zheng J, Lin Y, Huang J, Zhang Y, Tao Y, Zang X, Li D, Du M. Cell-cell contact with proinflammatory macrophages enhances the immunotherapeutic effect of mesenchymal stem cells in two abortion models. Cell Mol Immunol. 2019;16:908-920. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 107] [Article Influence: 21.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Eslani M, Putra I, Shen X, Hamouie J, Tadepalli A, Anwar KN, Kink JA, Ghassemi S, Agnihotri G, Reshetylo S, Mashaghi A, Dana R, Hematti P, Djalilian AR. Cornea-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Therapeutically Modulate Macrophage Immunophenotype and Angiogenic Function. Stem Cells. 2018;36:775-784. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 44] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Németh K, Leelahavanichkul A, Yuen PS, Mayer B, Parmelee A, Doi K, Robey PG, Leelahavanichkul K, Koller BH, Brown JM, Hu X, Jelinek I, Star RA, Mezey E. Bone marrow stromal cells attenuate sepsis via prostaglandin E(2)-dependent reprogramming of host macrophages to increase their interleukin-10 production. Nat Med. 2009;15:42-49. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1678] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1742] [Article Influence: 108.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 35. | Chen L, Lu FB, Chen DZ, Wu JL, Hu ED, Xu LM, Zheng MH, Li H, Huang Y, Jin XY, Gong YW, Lin Z, Wang XD, Chen YP. BMSCs-derived miR-223-containing exosomes contribute to liver protection in experimental autoimmune hepatitis. Mol Immunol. 2018;93:38-46. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 161] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Liu Y, Lou G, Li A, Zhang T, Qi J, Ye D, Zheng M, Chen Z. AMSC-derived exosomes alleviate lipopolysaccharide/d-galactosamine-induced acute liver failure by miR-17-mediated reduction of TXNIP/NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages. EBioMedicine. 2018;36:140-150. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 149] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Li S, Zheng X, Li H, Zheng J, Chen X, Liu W, Tai Y, Zhang Y, Wang G, Yang Y. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Ameliorate Hepatic Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury via Inhibition of Neutrophil Recruitment. J Immunol Res. 2018;2018:7283703. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Liu Y, Yin Z, Zhang R, Yan K, Chen L, Chen F, Huang W, Lv B, Sun C, Jiang X. MSCs inhibit bone marrow-derived DC maturation and function through the release of TSG-6. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;450:1409-1415. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Djouad F, Charbonnier LM, Bouffi C, Louis-Plence P, Bony C, Apparailly F, Cantos C, Jorgensen C, Noël D. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit the differentiation of dendritic cells through an interleukin-6-dependent mechanism. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2025-2032. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 463] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 451] [Article Influence: 26.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Spaggiari GM, Abdelrazik H, Becchetti F, Moretta L. MSCs inhibit monocyte-derived DC maturation and function by selectively interfering with the generation of immature DCs: central role of MSC-derived prostaglandin E2. Blood. 2009;113:6576-6583. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 478] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 479] [Article Influence: 31.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Selleri S, Bifsha P, Civini S, Pacelli C, Dieng MM, Lemieux W, Jin P, Bazin R, Patey N, Marincola FM, Moldovan F, Zaouter C, Trudeau LE, Benabdhalla B, Louis I, Beauséjour C, Stroncek D, Le Deist F, Haddad E. Human mesenchymal stromal cell-secreted lactate induces M2-macrophage differentiation by metabolic reprogramming. Oncotarget. 2016;7:30193-30210. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 92] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Liu X, Qu X, Chen Y, Liao L, Cheng K, Shao C, Zenke M, Keating A, Zhao RC. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells induce the generation of novel IL-10-dependent regulatory dendritic cells by SOCS3 activation. J Immunol. 2012;189:1182-1192. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 66] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Li YP, Paczesny S, Lauret E, Poirault S, Bordigoni P, Mekhloufi F, Hequet O, Bertrand Y, Ou-Yang JP, Stoltz JF, Miossec P, Eljaafari A. Human mesenchymal stem cells license adult CD34+ hemopoietic progenitor cells to differentiate into regulatory dendritic cells through activation of the Notch pathway. J Immunol. 2008;180:1598-1608. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 196] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Cahill EF, Tobin LM, Carty F, Mahon BP, English K. Jagged-1 is required for the expansion of CD4+ CD25+ FoxP3+ regulatory T cells and tolerogenic dendritic cells by murine mesenchymal stromal cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015;6:19. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 92] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Zhang B, Liu R, Shi D, Liu X, Chen Y, Dou X, Zhu X, Lu C, Liang W, Liao L, Zenke M, Zhao RC. Mesenchymal stem cells induce mature dendritic cells into a novel Jagged-2-dependent regulatory dendritic cell population. Blood. 2009;113:46-57. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 241] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Spaggiari GM, Capobianco A, Becchetti S, Mingari MC, Moretta L. Mesenchymal stem cell-natural killer cell interactions: evidence that activated NK cells are capable of killing MSCs, whereas MSCs can inhibit IL-2-induced NK-cell proliferation. Blood. 2006;107:1484-1490. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 773] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 756] [Article Influence: 39.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Sotiropoulou PA, Perez SA, Gritzapis AD, Baxevanis CN, Papamichail M. Interactions between human mesenchymal stem cells and natural killer cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:74-85. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 683] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 657] [Article Influence: 36.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Chatterjee D, Marquardt N, Tufa DM, Beauclair G, Low HZ, Hatlapatka T, Hass R, Kasper C, von Kaisenberg C, Schmidt RE, Jacobs R. Role of gamma-secretase in human umbilical-cord derived mesenchymal stem cell mediated suppression of NK cell cytotoxicity. Cell Commun Signal. 2014;12:63. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 34] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Spaggiari GM, Capobianco A, Abdelrazik H, Becchetti F, Mingari MC, Moretta L. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit natural killer-cell proliferation, cytotoxicity, and cytokine production: role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and prostaglandin E2. Blood. 2008;111:1327-1333. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 799] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 792] [Article Influence: 46.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Fan Y, Herr F, Vernochet A, Mennesson B, Oberlin E, Durrbach A. Human Fetal Liver Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Impair Natural Killer Cell Function. Stem Cells Dev. 2019;28:44-55. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 65] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Almeida CR, Caires HR, Vasconcelos DP, Barbosa MA. NAP-2 Secreted by Human NK Cells Can Stimulate Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cell Recruitment. Stem Cell Reports. 2016;6:466-473. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Glennie S, Soeiro I, Dyson PJ, Lam EW, Dazzi F. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells induce division arrest anergy of activated T cells. Blood. 2005;105:2821-2827. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 825] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 807] [Article Influence: 42.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Plumas J, Chaperot L, Richard MJ, Molens JP, Bensa JC, Favrot MC. Mesenchymal stem cells induce apoptosis of activated T cells. Leukemia. 2005;19:1597-1604. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 239] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Akiyama K, Chen C, Wang D, Xu X, Qu C, Yamaza T, Cai T, Chen W, Sun L, Shi S. Mesenchymal-stem-cell-induced immunoregulation involves FAS-ligand-/FAS-mediated T cell apoptosis. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:544-555. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 486] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 527] [Article Influence: 43.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Meisel R, Zibert A, Laryea M, Göbel U, Däubener W, Dilloo D. Human bone marrow stromal cells inhibit allogeneic T-cell responses by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-mediated tryptophan degradation. Blood. 2004;103:4619-4621. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1243] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1217] [Article Influence: 60.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Davies LC, Heldring N, Kadri N, Le Blanc K. Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Secretion of Programmed Death-1 Ligands Regulates T Cell Mediated Immunosuppression. Stem Cells. 2017;35:766-776. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 230] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Duffy MM, Pindjakova J, Hanley SA, McCarthy C, Weidhofer GA, Sweeney EM, English K, Shaw G, Murphy JM, Barry FP, Mahon BP, Belton O, Ceredig R, Griffin MD. Mesenchymal stem cell inhibition of T-helper 17 cell- differentiation is triggered by cell-cell contact and mediated by prostaglandin E2 via the EP4 receptor. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:2840-2851. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 170] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Qu X, Liu X, Cheng K, Yang R, Zhao RC. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit Th17 cell differentiation by IL-10 secretion. Exp Hematol. 2012;40:761-770. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 68] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Prevosto C, Zancolli M, Canevali P, Zocchi MR, Poggi A. Generation of CD4+ or CD8+ regulatory T cells upon mesenchymal stem cell-lymphocyte interaction. Haematologica. 2007;92:881-888. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 262] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 274] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Liu Q, Zheng H, Chen X, Peng Y, Huang W, Li X, Li G, Xia W, Sun Q, Xiang AP. Human mesenchymal stromal cells enhance the immunomodulatory function of CD8(+)CD28(-) regulatory T cells. Cell Mol Immunol. 2015;12:708-718. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 55] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Corcione A, Benvenuto F, Ferretti E, Giunti D, Cappiello V, Cazzanti F, Risso M, Gualandi F, Mancardi GL, Pistoia V, Uccelli A. Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate B-cell functions. Blood. 2006;107:367-372. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1263] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1235] [Article Influence: 65.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Tabera S, Pérez-Simón JA, Díez-Campelo M, Sánchez-Abarca LI, Blanco B, López A, Benito A, Ocio E, Sánchez-Guijo FM, Cañizo C, San Miguel JF. The effect of mesenchymal stem cells on the viability, proliferation and differentiation of B-lymphocytes. Haematologica. 2008;93:1301-1309. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 203] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Rafei M, Hsieh J, Fortier S, Li M, Yuan S, Birman E, Forner K, Boivin MN, Doody K, Tremblay M, Annabi B, Galipeau J. Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived CCL2 suppresses plasma cell immunoglobulin production via STAT3 inactivation and PAX5 induction. Blood. 2008;112:4991-4998. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 171] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Franquesa M, Mensah FK, Huizinga R, Strini T, Boon L, Lombardo E, DelaRosa O, Laman JD, Grinyó JM, Weimar W, Betjes MG, Baan CC, Hoogduijn MJ. Human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells abrogate plasmablast formation and induce regulatory B cells independently of T helper cells. Stem Cells. 2015;33:880-891. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 149] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Park MJ, Kwok SK, Lee SH, Kim EK, Park SH, Cho ML. Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells induce expansion of interleukin-10-producing regulatory B cells and ameliorate autoimmunity in a murine model of systemic lupus erythematosus. Cell Transplant. 2015;24:2367-2377. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 70] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Reuben A, Koch DG, Lee WM; Acute Liver Failure Study Group. Drug-induced acute liver failure: results of a U.S. multicenter, prospective study. Hepatology. 2010;52:2065-2076. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 515] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 478] [Article Influence: 34.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Bernal W, Auzinger G, Dhawan A, Wendon J. Acute liver failure. Lancet. 2010;376:190-201. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 720] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 677] [Article Influence: 48.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Volarevic V, Mitrovic M, Milovanovic M, Zelen I, Nikolic I, Mitrovic S, Pejnovic N, Arsenijevic N, Lukic ML. Protective role of IL-33/ST2 axis in Con A-induced hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2012;56:26-33. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 117] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Volarevic V, Paunovic V, Markovic Z, Simovic Markovic B, Misirkic-Marjanovic M, Todorovic-Markovic B, Bojic S, Vucicevic L, Jovanovic S, Arsenijevic N, Holclajtner-Antunovic I, Milosavljevic M, Dramicanin M, Kravic-Stevovic T, Ciric D, Lukic ML, Trajkovic V. Large graphene quantum dots alleviate immune-mediated liver damage. ACS Nano. 2014;8:12098-12109. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 64] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Volarevic V, Misirkic M, Vucicevic L, Paunovic V, Simovic Markovic B, Stojanovic M, Milovanovic M, Jakovljevic V, Micic D, Arsenijevic N, Trajkovic V, Lukic ML. Metformin aggravates immune-mediated liver injury in mice. Arch Toxicol. 2015;89:437-450. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Kubo N, Narumi S, Kijima H, Mizukami H, Yagihashi S, Hakamada K, Nakane A. Efficacy of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells for fulminant hepatitis in mice induced by concanavalin A. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:165-172. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Gazdic M, Simovic Markovic B, Vucicevic L, Nikolic T, Djonov V, Arsenijevic N, Trajkovic V, Lukic ML, Volarevic V. Mesenchymal stem cells protect from acute liver injury by attenuating hepatotoxicity of liver natural killer T cells in an inducible nitric oxide synthase- and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-dependent manner. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2018;12:e1173-e1185. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 47] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Ito H, Hoshi M, Ohtaki H, Taguchi A, Ando K, Ishikawa T, Osawa Y, Hara A, Moriwaki H, Saito K, Seishima M. Ability of IDO to attenuate liver injury in alpha-galactosylceramide-induced hepatitis model. J Immunol. 2010;185:4554-4560. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Milosavljevic N, Gazdic M, Simovic Markovic B, Arsenijevic A, Nurkovic J, Dolicanin Z, Djonov V, Lukic ML, Volarevic V. Mesenchymal stem cells attenuate acute liver injury by altering ratio between interleukin 17 producing and regulatory natural killer T cells. Liver Transpl. 2017;23:1040-1050. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 57] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Liu J, Feng B, Xu Y, Zhu J, Feng X, Chen W, Sheng X, Shi X, Pan Q, Yu J, Zeng X, Cao H, Li L. Immunomodulatory effect of mesenchymal stem cells in chemical-induced liver injury: a high-dimensional analysis. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10:262. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Shi X, Liu J, Chen D, Zhu M, Yu J, Xie H, Zhou L, Li L, Zheng S. MSC-triggered metabolomic alterations in liver-resident immune cells isolated from CCl4-induced mouse ALI model. Exp Cell Res. 2019;383:111511. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Zhao X, Shi X, Zhang Z, Ma H, Yuan X, Ding Y. Combined treatment with MSC transplantation and neutrophil depletion ameliorates D-GalN/LPS-induced acute liver failure in rats. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2016;40:730-738. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Huang B, Cheng X, Wang H, Huang W, la Ga Hu Z, Wang D, Zhang K, Zhang H, Xue Z, Da Y, Zhang N, Hu Y, Yao Z, Qiao L, Gao F, Zhang R. Mesenchymal stem cells and their secreted molecules predominantly ameliorate fulminant hepatic failure and chronic liver fibrosis in mice respectively. J Transl Med. 2016;14:45. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 118] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Nauta AJ, Fibbe WE. Immunomodulatory properties of mesenchymal stromal cells. Blood. 2007;110:3499-3506. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1289] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1288] [Article Influence: 75.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 80. | Gazdic M, Volarevic V, Arsenijevic N, Stojkovic M. Mesenchymal stem cells: a friend or foe in immune-mediated diseases. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2015;11:280-287. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 149] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Poltavtseva RA, Poltavtsev AV, Lutsenko GV, Svirshchevskaya EV. Myths, reality and future of mesenchymal stem cell therapy. Cell Tissue Res. 2019;375:563-574. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |