Abstract

In the competitive, increasingly international music business, publishers are developing new ways to increase effectiveness and efficiency of the monetization of the copyrights they own or manage. Driven by various needs, publishers become entrepreneurs in new markets by choosing the path of direct memberships in foreign copyright collecting societies, rather than entrusting sub-publishers or taking the detour through their domestic copyright collecting society. Since with great power comes great responsibility, publishers as entrepreneurs are pursuing various economic opportunities, but at the same time are also facing great challenges. This paper aims at studying the motivation, obstacles and potentials and deriving possible solutions for this step and thus improving the understanding of as well as supporting publishers in this entrepreneurial activity.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Stagnation is regression – this also applies to companies in the music industry, an environment characterized by strong competition, multiple technological developments and disruptive market players. Reinventing business, constantly questioning the traditional approach, responding to new trends and developing and pursuing long-term strategies are the prerequisites for sustainable corporate success. Combining the principles of evolution and entrepreneurial research, various analogies can be found (Nielsen and Lassen 2012), highlighting the application of an entrepreneurial mindset as a viable approach for existing businesses.

Thus, not only new market actors and their entrepreneurial activities, but also existing companies are subject to continuous development in order not to be made obsolete by economic evolution. Very few industries are static, but the music industry is particularly creatively challenged because it has clung to established but anachronistic models for too long (Wilde and Schwerzmann 2004). So what are the new needs and challenges that the players in the industry are confronted with, which make them continuously become entrepreneurs within their industry? The paper at hand aims to answer this question from the perspective of music publishers focusing their interaction with copyright collecting societies (CCS) and sub-publishers in the context of the international exploitation of music copyrights.

In contrast to the past, the business model of music publishers today is more extensive and complex, involving the management, promotion and licensing of the use of copyrights of their represented writers. Due to the complexity and volume, the licensing of these rights is not feasible for a single economic entity. Therefore, this task is solved cooperatively: publishers become members of copyright collecting societies, authorizing them to handle the licensing of various types of copyright use on their behalf. If licensing takes place outside the area of operation of the (usually domestic) CCS, royalties are paid via intermediaries such as foreign collecting societies or sub-publishers. Consequences are payment delays, non-transparency and higher transaction costs. Due to increasing technology-driven internationalization, this has also a major impact on smaller publishers, as they generate increasing amounts of royalties in foreign markets. However, there is growing awareness among music publishers regarding a relevant market change: Legal harmonization and technological developments have facilitated the option of direct memberships of publishers in multiple, international CCS.

Due to these trends and challenges, also existing music publishing companies need to evolve constantly by applying entrepreneurial principles. Transferring these principles to the current situation of music publishers in general and the opportunity of direct membership in particular illustrates the analogies. The first aspect is the correct interpretation of market-changes (Kirzner 1973). Applied to the music industry this covers the recognition of an increasing competition for music publishers driven by self-marketing platforms and technology-driven publishing administrators. Second, entrepreneurs need to perceive opportunities to improve the current state (Stevenson et al. 1999). In terms of the music business, publishers, for example, need to identify ways to increase payment speed, reduce transaction costs and transparency which is enabled by direct CCS membership. Third, entrepreneurs must implement proactive decision making and risk taking (Miller 1983). Since applying for direct CCS membership in foreign countries is still in its infancy, music publishers are often faced with technical and organizational challenges and risks. Finally, it can be argued that direct membership of music publishers in foreign CCS is consistent with the emerging consensus that internationalization is an entrepreneurial activity (O’Cass and Weerawardena 2009).

In this paper, we observe this market change and contribute to this topic from multiple perspectives by gathering needs, challenges, opportunities and highlighting solutions for music publishers in the implementation of direct memberships in foreign CCS. The first sections cover a short summary of the mechanics of the music business (Sect. 2) and a detailed explanation of direct memberships as an entrepreneurial opportunity (Sect. 3). In Sect. 4, we give details about the methodology used to gather information about the state of the art of copyright exploitation. Based on these findings, Sects. 5, 6 and 7 present needs, challenges and opportunities from the publishers’ perspective. Major outcomes are clearly depicted requirements of the publishers and an aggregated view on the interaction with CCS by deriving harmonized process and data models. Based on these models, software tools supporting a seamless integration of different international CCS can be developed. Corresponding prototypes are introduced in Sect. 8. The economic potential of direct membership is assessed in Sect. 9, whereas a more prospective view including future research steps and necessary development tasks is presented in Sect. 10.

2 Economics of music copyright

Today’s music business is characterized by a plethora of different income channels, one of which is copyrights. Copyright holders, for instance composers, authors or publishers, generate the majority of their income based on three different categories (Pitt 2010, p. 16). First, performance rights royalties are generated by licensing the performance of music, such as public performances, performances on radio or television and non-interactive streaming. Second, mechanical rights royalties result from the licensing of recordings and their reproduction as audio files on storage media and through interactive streaming. Finally, synchronization royalties are generated by licensing the syncing of the musical work with another (usually visual) medium, e.g., in movie/TV soundtracks. Besides different income channels, music business is getting more and more global resulting in an increased economic potential – a development underlined by the following financial numbers.

The distribution of royalties by CCS is steadily increasing. Since 2003, collected royalties of CCS increased from 6.15 billion to 9.65 billion Euro per year (CISAC 2014, 2019). With a 53 percent share of global collections, Europe is the largest region in terms of music collections (CISAC 2019). Although the digital sector is constantly growing, the traditional income channels “Live” and “TV and Radio” account for 69 percent of the royalties collected (CISAC 2019). Recent technological, organizational and legal advances are challenging the traditional network of collecting societies and opening the market for direct multi-territorial licensing. However, advances are largely focused on online rights. For example, technology-driven publishing administration companies such as Kobalt Music GroupFootnote 1 or SongtrustFootnote 2 offer a large network of contracts with CCS and digital service providers. In addition, CCS consolidate their repertoire through joint ventures such as ICE.Footnote 3 Territorially managed uses of copyright, such as performances at local events or terrestrial radio/TV, however, remain outside the focus. In order to save deductions and to speed up the exploitation process, publishers are increasingly choosing the option of “direct memberships.” While this option is open to all types of copyright holders, publishers are inherently focused on managing the copyright exploitation process and therefore recognize entrepreneurial opportunities herein first. Therefore, we set the research focus specifically on the needs of music publishers. Furthermore, we narrow the scope of our study to small-to-medium-sized music publishers focusing on the live music sector in Europe. Although the applicability of the results can be expected beyond this scope, the variance in economic, institutional or legal factors between different types of copyright holders and markets leads to the necessity of a closer examination of concrete scenarios.

To gain a better understanding of stakeholders and their responsibilities as well as the different ways of exploiting music copyrights internationally, the following paragraphs give a short introduction to the music business’ value chain. For the sake of brevity, the variety of stakeholders is reduced to a minimum and iteratively extended. Furthermore, a few simplifications have been applied.

Any exploitation of music copyrights starts with the composition of a musical work by one or more writers. Since the commercialization of the work can be tedious, writers usually entrust a publisher with this task. Even if limited to the national level, the ways of exploitation are so extensive that publishers cannot license every use of the work themselves. Due to this fact, CCS handle this task as intermediaries. A CCS represents a great number of copyright holders and an even greater number of their musical works, thus allowing for applying economies of scale (Handke and Towse 2007). However, since copyright depends on legal frameworks, CCS generally restrict their licensing activities to a specific country (Handke 2013). In order to still receive international royalties, various options with different advantages and disadvantages exist.

The default option is the management of international copyrights by domestic CCS. In this case, international royalties are collected by foreign CCS, transferred to domestic CCS, and later distributed to copyright holders. Though this is a comfortable option for copyright holders, it is likely to result in additional deductions and significantly delayed royalty payments.Footnote 4 To accelerate the process, the second option, particularly for publishers, is to transfer the copyrights for a limited territory to another publisher – a so-called sub-publisher (Towse 2017).Footnote 5 On behalf of the publisher the sub-publisher deals with the foreign CCS. However, this in turn leads to a decrease in revenue due to administrative costs (Towse 2017). A third option that has recently gained attention are direct memberships with foreign CCS.Footnote 6 This option overcomes the necessity to include intermediaries at the expense of increasing efforts for the copyright holders (see Fig. 1).

3 The direct membership – a universal economical remedy?

In order to transform an entrepreneurial opportunity into economic benefits, a number of conditions must be met. In Davidsson (2015), 210 leading journal articles that focused the term “entrepreneurial opportunity” in their research were analyzed. The study proposed a triadic construct: External Enablers (e.g., regulation, technological advances), New Venture Ideas (an entrepreneur’s ideas for future businesses) and Opportunity Confidence (“actor’s subjective evaluation of the attractiveness” of an opportunity) (Davidsson 2015).

The act of introducing a new type of entrepreneurial action requires the recognition of an entrepreneurial opportunity. While majors have been using the approach of direct memberships for a long time and address international markets via offices in various countries, small-to-medium-sized publishers cannot afford to do so. Likewise, additional experts addressing legal and marketing specifics are beyond the budget. However, the current trend toward direct memberships is supported by two external enablers:

-

1.

Legal harmonization: Under Directive 2014/26/EU Article 5 (2) the European Parliament and Council directed its member states to grant that copyright holders shall have the right to authorize collecting societies with the management of categories and types of rights in territories of their choice (European Parliament, Council of European Union 2014).Footnote 7 For instance, a copyright holder can legally authorize a CCS with the management of the performance rights of its repertoire for the countries of its choice and conversely terminate authorizations, according to Article 5 (4).Footnote 8

-

2.

Technological progress: Many potential problems from market insights to the processing of licensing statements are data-related issues and can thus be solved with software.

These are the reasons why an increasing number of publishers consider the exploitation of copyrights via direct memberships in foreign CCS as a promising business opportunity.

Since copyrights relating to territories, categories and types must be managed exclusively by a CCS, it should be noted that overlapping assignment of copyrights to different CCS must be avoided. This is the responsibility of the copyright holder – and is noted on many registration forms. On the other hand, since the three criteria territory, categories and types are independent of each other, direct memberships in several CCSs in the same country are possible or even necessary.

Following the above introduced classification of Davidsson , the motivation of publishers to pursue the option of direct membership will be discussed in Sect. 5, aiming at a better understanding of the business expectations of publishers connected with this rather new approach (opportunity confidence). External conditions disabling the implementation of this option for publishers are discussed in Sect. 6, while Sect. 7 describes new entrepreneurial chances arising from this new state (including new venture ideas). Finally, prototypical technologies that were developed in the research process and can be regarded as additional external enablers will be presented.

4 Methodology

As methodological basis we follow the design science research (DSR) approach as proposed by Peffers et al. (2007). The six steps of the DSR methodology mapped to our research and the content of this paper are as follows:

-

1.

Identify problem and motivate: Global music copyright handling is a complex task. Publishers need support to cope with new developments and demands. The current situation of global music copyrights was presented in section 2, details from a publishers’ point of view and are given in the following chapters.

-

2.

Define objectives of a solution: The objective of our research is to enable new entrepreneurial opportunities for music publishing companies as presented in Sect. 3. Therefore, we develop software tools supporting music publishers to effectively and efficiently work with multiple, international CCS allowing them to generate values from international copyrights.

-

3.

Design and development: The majority of this paper deals with the presentation of the underlying concepts to implement a solution. This covers the presentation of the needs, challenges and opportunities in the following sections.

-

4.

Demonstration: We present a web application for evaluating the performance of European CCS and a prototypical desktop application for a standardized registration process for musical works with CCS. Both software tools were developed by the authors and are described in Sect. 8 of this paper.

-

5.

Evaluation: Several music publishers have already tested prototypical implementations of various software tools and gave feedback as presented in Sect. 8. We have implemented their feedback to improve effectiveness and efficiency of the tools. In addition, we are continuously working together with a software company providing tools for music publishers to gather feedback about needs of the domain.

-

6.

Communication: This paper presents an overview of the insights from a research project. Additional information can be found on the project’s website.Footnote 9

To identify needs, challenges and opportunities concerning the management of music copyrights, we followed a threefold approach, addressing publishers and CCS as the most relevant stakeholders within the value chain. First, we conducted semi-structured interviews with representatives of publishers. Second, we gathered key performance indicators of European CCS. Finally, based on the findings we selected six CCS and analyzed processes and data necessary for collaboration with publishers. In the following sections, these three steps are introduced in more detail.

4.1 Interviews

To gain a better understanding of the music publishers’ perspective on the status quo, challenges and trends of international copyright management, we conducted a survey. To ensure openness and objectivity within this exploratory context, a qualitative research setup was chosen (Sutton and Austin 2015). To allow for a comparison of the results and to ensure completeness of the interviews, semi-structured questionnaires comprising 26 questions were used. The questions cover basic demographic information, current workflows, the state of the art of international copyright exploitation, experiences in collaborating with CCS, challenges and wishes in that regard.

The sample included nine interviews with representatives of German music publishers held between June and September 2019. All interviews were conducted by phone- or Internet-based conference tools by two people and recorded digitally to allow for a comprehensive, comfortable and traceable analysis. The duration of the interviews varied between 17 and 45 minutes with a cumulative duration of almost five hours. Following the approach suggested by Sutton and Austin (2015), the recordings were fully transcribed, coded and evaluated. Transcription and coding was done using the software tool f4.Footnote 10

4.1.1 Demography

Since the music business and the involved companies’ roles are diverse, the compilation of survey participants was aimed to cover different segments of the business, like genre, markets or size. To get an impression of the spectrum of interviewees, basic demographic information was surveyed (see Table 1). If a publisher is active in more than one business role or on more than one market, the dominant option is marked bold. Despite the broad spectrum of different publishers, it is important to note that due to the underlying methodology the survey is not representative and, thus, no general conclusions can be drawn (see Sect. 4.1.2). Nevertheless, the demographics should help to evaluate the background of participants. The figures on the market share of independent publishers [42% in 2019, compared to 25% of Sony and 21% of Universal Music Publishing Group, according to Music and Copyright (2020)] as well as Germany being the fourth largest market worldwide (CISAC 2019) show the relevance of the type of companies examined.

Most of the interviewees’ companies cover two roles, label and publisher. This is a common practice in the modern music industry (Tschmuck 2016). Regarding the musical focus, all but one company covered popular music. Besides conventional exploitation of musical works for consumers with bands and releases, a few companies were active in niches like production music, illustration music or custom compositions for the TV sector. The companies were all internationally active, i.e., generating revenue on markets other than their home country as well, although the predominant market in many cases was Germany. The role of the interviewees ranged from managers and owners to employees responsible for copyrights ensuring relevant as well as competent feedback. Reflecting the common corporate structures within the music industry, all interviewees worked in micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises with corresponding revenues.

4.1.2 Limitations

As a result of the study design, a few limitations emerge. Due to the qualitative character of the study, the general applicability of the statements is limited. More generic conclusions in any means cannot be drawn and would require a quantitative study. Hence, the limitation on German publishing companies impairs conclusions for a more global perspective. Additionally, the focus on independent music companies prevents transferring the findings to the majors of the music business.

Furthermore, the interviews were conducted in German. In order to be able to illustrate the findings by citations, the statements were translated. Rather colloquial descriptions were interpreted with the aim of achieving the best possible compromise between authenticity and comprehensibility.

4.2 Key performance indicators

For the effective and efficient exploitation of music copyrights, CCS play a crucial role. To capture the general economic performance of these stakeholders, a quantitative analysis of European CCS was conducted.

Therefore, annual business and transparency reports were analyzed. To create a standardized basis for comparing and deriving insights from commonly reported financial data, KPIs were collected, normalized and analyzed.Footnote 11 Altogether, ten different KPIs were extracted (see Table 2). The results of the data collection and harmonization steps described were compiled in a semi-structured format (CSV) providing the basis for a quantitative analysis of the data.Footnote 12

4.2.1 Data preparation

To prepare the data for quantitative analysis, it first had to be extracted. For this purpose, the publicly available data of 40 CCS (for musical performing rights, mechanical reproduction rights and both) of 35 European countries were extracted and consolidated from their annual business and transparency reports. The data collection took place between September and November 2019. In order to capture the current situation as closely as possible, the most recent report available was chosen. For the majority of the CCS (\(\approx \) 84%), the most recent reporting year was 2018 while the oldest report was from 2016. Manual extraction was necessary, since the annual reports were published as non-standardized PDF documents.

It was noticeable that most CCS report similar KPIs, although partly under different names. However, due to differences in data quality and scope, semantic mappings were not applicable to every CCS-specific KPI. In case of semantic deviations preventing a mapping, some KPIs had to be calculated, e.g., the total turnover, which was not always explicitly stated. As an additional remedy, missing figures were supplemented from other sources (e.g., the official website of the respective CCS or the CISAC members directory.Footnote 13) Sources differing from the annual reports as well as data transformations were assigned to the corresponding data set. Additionally to the CCS-national currency, a uniform currency was chosen (EUR) to ensure comparability. For this purpose, exchange ratesFootnote 14 at the end of the reporting year were used to convert the national currency of the respective collecting society into EUR. However, even taking these aspects into account, relevant KPIs could not be found for every CCS. Due to this fact, the sample size of individual KPIs may vary.

4.2.2 Limitations

The methodology presented is subject to several limitations. First, the data collected represent only a snapshot not capturing annual fluctuations. Second, the mapping of CCS-individual KPIs to standardized KPIs is lossy, considering varying monetary information, price levels and conversion rates. Finally, the statistical analysis of the data is also subject to the limitation that only a small sample could be collected. Other limitations may result from translation errors or generally from the manual nature of data extraction.

4.3 Process and data modeling

While the previously described method draws a coarse-grained and generic picture of the economics of CCS, a more detailed analysis of CCS was conducted in a supplementary study. The aim was to investigate technological and organizational requirements for interaction between CCS and publishers. Furthermore, based on the findings of this methodological approach, possible software solutions for managing the complex interactions with CCS can be developed.

We focused our work on the societies that were considered relevant by the interviewees: GEMA (Germany), AKM/AUME (Austria), SUISA (Switzerland), BUMA/STEMRA (The Netherlands), SACEM (France), and SIAE (Italy). To reconstruct processes and data models, we took publicly available membership application forms into account.

4.3.1 Process modeling

Modeling took place in a workshop-based format consisting of three authors of this article. We collaboratively analyzed available registration information and simultaneously extracted the underlying processes.

Based on the textual descriptions, we defined structured process models using the Business Process Model and Notation (BPMN) – a widespread notation for graphically capturing and structuring processes (Chinosi and Trombetta 2012). With these process models, we are able to identify the chronological order of activities publishing companies have to perform. Figures 2 and 3 depict the registration processes for the Austrian CCS AKM/AUME and the German CCS GEMA, respectively. For the sake of brevity and comprehensibility, the process models do not display exceptional situations but only the idealized registration process. As can already be seen without any prior knowledge of reading BPMN, there are differences in both, structure and content of the process models. In the following, we present the GEMA registration process (Fig. 3) in more detail.

Each BPMN process consists of a sequence of so-called activities. An activity represents a precisely defined piece of work performed by a specific actor. As can be seen from Fig. 3, the registration process consists of the two actors publisher and GEMA. As we are only interested in the activities of the publisher, the GEMA activities are undisclosed. In the lower part of Fig. 3, the registration process is depicted beginning with the preparation of the membership application. Using BPMN, it is possible to outline activities on different levels of detail. This is shown with the second activity, send membership application, which is detailed in the upper part of Fig. 3. Depending on the reader of the process model, a more coarse-grained view, i.e., send membership application, might be sufficient or a more fine-grained view (using the detailed sub-process) is necessary.

For synchronizing various process participants, BPMN provides messages and events. For example, in the GEMA registration process, the publishing company waits for receiving the deed of assignment and payment information – this reflects the textual description of the process as shown above. As the internal GEMA process is not relevant, we do not outline how and when GEMA sends these information. Instead, the event element pauses the process until the documents arrive. After arrival of the deed and payment information, the publishing company has to pay the admission charge, sign and send the contract back to GEMA. Since the order of these activities is not of particular relevance, they are encapsulated in a so-called AND-gateway. This gateway splits up the process into two parallel sequences. After both activities were performed, the process is merged and waits for receiving the countersigned contract.

Using publicly available information, we were able to model six society-specific registration processes. A repository containing the process models can be found online.Footnote 15 Based on these models, we were able to identify commonalities and differences in registering with the various collecting societies. These findings are a starting point for unifying and allow for multi-society registration.

4.3.2 Data modeling

Using the above-mentioned sources, we identified data necessary for registering with CCS. Since every CCS follows its own naming convention and has distinct requirements on mandatory data fields, we had to harmonize the data. In addition, CCS from different countries use different languages resulting in even more transformation efforts. Table 3 shows an example record of data required when registering with the German CCS GEMA.

As a result of the harmonization, we established a categorized list of data fields used by different CCS as presented in Table 4. The entire data model containing mappings of data fields between different CCS and the result of the data harmonization can be found online.Footnote 16

4.3.3 Limitations

With the help of publicly available information, we were able to reconstruct registration processes and data requirements. However, using this method, a few limitations need to be considered. First and foremost, it is not possible to deduce thorough process models from the given information due to missing and ambiguous information in the textual description or PDF/web forms. In addition, for some CCS we cannot infer the whole process. For example, the AKM/AUME registration form is only available on demand. Since information are not available beforehand, it is not possible to identify necessary registration data.

It is important to mention that process and data models only represent a snapshot in time. As various CCS currently shift from offline application processes to online processes using webforms, processes may decrease in size and become more homogeneous, since the entered data need to be processed automatically.

5 Needs

After introducing the methodological elements applied, the following sections merge the findings to draw a comprehensive figure of the needs, challenges and opportunities in the international management of music copyright.

In the following, quotations from the interviews are listed according to the scheme (P5:42). The first part represents the interviewee (P5) and the second part (42) the paragraph in which the quoted statement was made.

As mentioned above, there are various options for publishers to exploit their copyrights internationally. For a long time, the predominant way was via sub-publishers (Towse 2017) or via domestic CCS and their reciprocal agreements (as the default option). This is also reflected in the interviews – almost all interviewees used these two constructs (see Table 5). In the recent past, the option of direct memberships gained practical relevance, which, however, still has a much lower market penetration. This section covers the needs of the publishers by analyzing advantages and disadvantages of the different options and thus examining the motivation of the publishers for direct memberships at multiple CCS.

As can be seen in Table 5, the different options are not mutually exclusive – a decision has only to be made per territory and type of rights. It should be noted that the table only shows the paths of international exploitation – on national level, the exploitation of copyrights for all the publishers was done via their domestic CCS (in this case the GEMA).

According to which criteria and with which motives do publishers decide for or against a certain exploitation channel? A first decisive factor is the importance of the respective market for the publisher. However, two different interpretative approaches prevail here. First, there is the strategy of reaching important markets via sub-publishing partners.

“We have sub-publishing partners in the core markets, so to speak, and otherwise we administer the rights through GEMA. (P3:30)”

Second, it is also argued that direct membership of the respective CCS would provide better access to the market and data.

“Yeah, Switzerland. Switzerland for example, simply because of transparency and of course also because of its value. (P6:52)”

How can this apparent contradiction be resolved? The answer lies in the role of the sub-publisher. The expectation is that the sub-publisher will actively take care of the marketing and exploitation of the catalog transferred to it or cover communication with the foreign CCS. If it does so, it can become a valuable partner in the addressed market.

“So France is a bit of an exception for me personally because it is a very important market for us and because we need local partners there who actively exploit our repertoire. [...] But as I said, Spain, Portugal, Poland, England, I can think of a whole series of countries or territories where it [a direct membership] would make absolute sense. (P3:50)”

If this expectation remains unfulfilled, the option of a direct membership becomes more appealing, since expenses for services with questionable effects can be avoided. Even without comprehensive expertise in the relevant market, the publisher can provide basic services itself. If the publisher can already draw on market knowledge, it is all the easier to choose the path of taking more responsibility but also to develop more economic opportunities through a direct membership.

“But I have for example a sub-publisher in Spain/Portugal, who of course takes a pretty good percentage for managing our rights, but even though it is a really well known publisher it is not really active exploiting our repertoire. And the fact that they just manage our rights there and take their fee without taking care about sync rights or anything else, that I would of course like to replace it by simply becoming a member in the country and then just pay the usual fees of the collecting society. (P3:45)”

In addition to the sub-publisher’s lack of marketing and exploitation activities, shortcomings regarding controlling (checking of statements, complaints) were also mentioned. All in all, it can be stated that publishers increasingly critically assess the value for money of their publishing partners and are therefore beginning to replace partners with direct memberships.

“Because you can see what kind of turnover is coming in and you think about it, you always give something away and if you have the possibility and the resources or you do it yourself...We have the monitoring system and we can see for ourselves what has to be reported, what can be complained and of course we always had to tell our sub-publisher that. We can then almost do the work ourselves. (P9:32)”

In addition to partner-induced and strategic considerations, financial needs also provide arguments for direct membership. The processing steps by additional stakeholders between the foreign CCS and the publisher require additional time, regardless of whether the route via a sub-publisher or domestic CCS is chosen.

“That is one reason, the second reason which of course is absolutely an argument in favor is simply the time factor. It doesn’t matter if you have a sub-publisher or if you let [domestic CCS] take care of your international rights, it just takes a long time. It’s quicker via sub-publishers than via [domestic CCS], but money that comes from a foreign collecting society via [domestic CCS] needs often two years for transit. And if you could accelerate that, that’s a bad performance, of course. (P3:46)”

Thus, the choice of a particular exploitation option for a country is an issue with several criteria to be considered. In addition to the economic relevance of the targeted market, the performance of the sub-publisher is crucial. Furthermore, driven by their heterogeneity (see also Sect. 6.2) various characteristics of the CCS are also relevant factors in the decision-making process.

“The criteria ...collecting society: communication, efficiency, friendliness, language. Although language doesn’t matter, really. Sub-publisher: the decisive criterion is: can they really do something for us. (P4:33 - 34)”

It can be concluded that dissatisfaction is often the driving force for developing new ways of exploiting copyrights. This aligns with antecedents of entrepreneurship which can be found in the context of employees (Serviere 2010). The potential of sub-publishers compared to exploitation via domestic CCS is a limited acceleration of financial transactions and potential improvements regarding the marketing of the repertoire. As with any form of cooperation, expectations are linked to such partnerships. If the publisher’s expectations are not met or financial conditions seem not rewarding, direct membership offers an additional option. The increased responsibility and workload of the publisher is matched by greater freedom of action and greater efficiency in terms of time and money. This again aligns with the paradigm of an entrepreneurial return based on lowering transaction costs by establishing new improved organization structures (Foss and Foss 2008).

It also becomes apparent that the decision for or against an exploitation option cannot be made in a globally uniform manner. Similarly to other entrepreneurial decisions, various criteria such as possible partners, addressed territories and own competences have to be taken into account. The choice of a direct membership is of increasing importance in the variety of options, but comes with a variety of challenges discussed in the next chapter.

6 Challenges

In this section, we present an overview of challenges for publishers when registering with foreign CCS. Based on the interviews, process and data modeling, and capturing of KPIs, three categories of challenges were identified. Organizational challenges cover communication with CCS. Technological challenges occur due to heterogeneities in the technological basis of the interaction with different CCS. Subjective challenges result from a lack of knowledge and thus lead to a situation where dealing with foreign CCS is avoided.

6.1 Organizational challenges

Organizational challenges for direct membership in foreign CCS are triggered by both, the publisher and the specific CCS (see Table 6). While the first indicates weaknesses of the publisher hindering it to become a direct member, the latter indicates the lack of external enablers needed for direct memberships to be perceived as an entrepreneurial opportunity (Davidsson 2015). The majority of challenges result from the fact that publishers must adhere to heterogeneous registration processes and might have to put additional effort into legal adaptions of existing documents. Organizational challenges hampering entrepreneurial opportunities occur, in particular, in fragmented markets like Europe with different languages, regulations and customer preferences (van Weele et al. 2018).

OC1: Additional effort when registering with foreign CCS is induced by the different organizational structures of CCS. First and foremost, registering with foreign CCS is associated with additional costs. Publishing companies need to gather information about specific registration requirements. Adding to this fact, during process and data modeling, we were able to identify a vast amount of deviations in the registration process. These deviations can be categorized as follows:

-

Different order of mandatory steps: While most CCS allow for registration using a web-based form, subtle differences in the process models occur. For example, when registering with the German CCS GEMA, publishers have to pay the registration fees before they receive a signed copy of their membership contract. Contrary, the French CCS SACEM sends signed contracts before membership fees are to be paid.

-

Additionally required steps: Publishers registering with a foreign CCS have to fulfill different requirements including presentation of statements concerning aspects of the company. For example, the Italian CCS SIAE and the French SACEM additionally require publishers to validate the name of their company. This step is not necessary for registering with the other analyzed CCS.

-

Non-transparent registration processes: Some CCS do not make their registration process completely transparent. For example, when registering with the Austrian CCS AKM, publishing companies first have to complete a minimal membership application. After processing of this application by AKM, publishing companies receive an online link to the complete application. Without further information gathering, publishers do not have knowledge about necessary registration data.

Besides deviations in the registration process, publishers are faced with the fact that different CCS do not comply with a standardized data model. Thus, differences in data field names and semantics of data fields occur or additional data is required. While naming ambiguities are usually easy to solve (e.g., GEMA calls the data field company name entire publishing company name, SACEM calls this field company name), semantic differences are often more subtle but hamper automated registration with different CCS. For example, the meaning of the legal type of a publisher varies between the different CCS.

Challenge OC2: Language barriers are related to data field naming inconsistencies. Since registration with foreign CCS is a relatively new phenomenon, most European CCS only provide application forms in their national language. This may result in ambiguous interpretations due to poorly or not at all translated forms. In addition, communication with representatives of a CCS might get even more complicated in a multilingual context.

Publishers wanting to register with foreign CCS have to adhere to different restrictions, resulting from OC3: Legal barriers and corporate guidelines. Although the national legal frameworks are transpositions of the Directive 2014/26/EU within the European Economic Area (EEA), the rather abstract definitions of the Directive leave national legislators and individual CCS room for interpretation – for further discussion on this see Matanovac Vučković (2016). According to specific legal requirements or the policies defined by the CCS, publishers might have to consider different possibilities and restrictions of work registrations or have to supply different verification and supporting documents. For example, for registering with the SIAE, publishers need to provide proof of work usage during registration process.

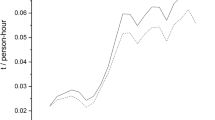

Challenge OC4: Heterogeneity of CCS performance is again induced by the different organizational structures of CCS and different designs of business processes, which in turn can derive from legal specifics [cf. OC3 and Rochelandet (2003)], the lack of unified data standards (TC1) and methods/tools for automated data processing (TC2) (see Table 7). Among the music publishers, consciousness about the variance of CCS performance already exists, as the quote in Table 6 emphasizes. This thesis is supported by a quantitative analysis of the KPIs of the CCS in the sample as shown in Fig. 4. The upper boxplot shows the dispersion of the cost rate (\(\hbox {n} = 32\)). With a range of 20% between the min and max value (not including the outlier), it becomes visible to what extend cost rates of individual CCS may vary (see also Sect. 8.1). The boxplot below shows the dispersion of the deviation of the distribution sum from the distributed royalties in the same year by each CCS (\(\hbox {n}=24\)). This metric was introduced to approximate the tendency toward delays in the distribution of royalties. While a small difference between the two metrics does not necessarily indicate a nearly synchronous distribution, a larger difference between the two metrics indicates that the distribution was not carried out on an accrual basis. Here, the range between the minimum and maximum values indicates the variance in aspects of time efficiency among CCS.

6.2 Technological challenges

Technological challenges in registering with foreign CCS result from different registration processes and diverse data requirements and are indicating the lack of external enablers for direct memberships to be perceived as an entrepreneurial opportunity. Due to this situation, publishers have to transform data into different formats. Transformation is faced with two difficulties. On the one hand, data mappings might not be possible, since data formats are not equivalent. On the other hand, every transformation has the potential of mistakes resulting in erroneous data. An overview about identified technological challenges is presented in Table 7.

One of the major challenges for direct membership in foreign CCS is TC1: Lack of unified data standards. Due to this fact, communication with different CCS is cumbersome. Since different CCS use different data models, publishers have to keep in mind how to map data fields between the CCS. In addition, data might be represented differently, e.g., normalized to different degrees. To give a simple but illustrative example, the street address of a publisher is a single field in the SACEM data model, where GEMA splits it up to the fields street and number. Adding to this situation is the fact that CCS use different names for identical data fields, be it due to language reasons or to varying regional habits.

Table 8 shows an aggregated view of data heterogeneities by depicting the matching of data fields of different CCS. First, the total amount of data fields per CCS is shown, e.g., five fields for AKM/AUME. In addition, the coverage between two CCS data is displayed. For example, two percent of the data fields of AKM and BUMA correspond with each other. In addition, six percent of AKM data fields are not present as BUMA data fields and 92 percent of BUMA data fields are not available as AKM data fields. As indicated in Table 8, the majority of data fields does not match and, thus, publishers need to adhere to different data models.

In conclusion, it can be stated that there is a lack of methods and tools for automated data processing (TC2) due to heterogeneous data and process models. Data heterogeneities increase the effort required when communicating with CCS because publishers cannot automatically parse requests and responses. In addition, process deviations result in the need for systems tailored to a specific CCS. While this might be feasible when interacting with a small number of CCS, it is a limiting factor when managing a great number of musical works globally.

6.3 Subjective challenges

Subjective challenges hinder the evaluation of the attractiveness of direct memberships as entrepreneurial opportunities due to a lack of awareness or opportunity confidence (Davidsson 2015). In fact, the main reason for subjective challenges is lack of knowledge, as Table 9 indicates.

The first subjective challenge results from the fact that not all publishers were aware of the fact they can become direct members of foreign CCS (C1: Lack of knowledge about the possibility for direct membership). Thus, these publishers did not consider direct membership until now and did not estimate the costs and benefits of doing so. This lack of knowledge results from the territorial characteristics of CCS (Harrison 2011). Due to this fact, most CCS do not actively present themselves as partners for foreign publishing companies. (This is also indicated by OC2: Language barriers, since a majority of CCS membership applications are only available in the national language but not in English.)

Several publishers are reluctant about direct memberships because costs and benefits are not completely transparent (SC2: Lack of knowledge about costs and benefits from direct membership). Depending on the previously chosen exploitation options, various aspects have to be weighed up. Compared to the way via domestic CCS, direct memberships can in particular increase the transparency and reduce the latency of royalty payments – advantages that are difficult to quantify financially. If a cooperation with a sub-publisher is replaced by a direct membership, the financial advantages are clear (avoiding the sub-publisher’s fee), but the value of the services provided by the sub-publisher, such as administration or marketing activities, might be hard to quantify as well. As a result, publishers often cannot reliably calculate the revenue differences between direct and indirect international copyright exploitation options.

As the music market is constantly evolving, publishers cannot be sure about future developments resulting in uncertainties (SC3: Lack of knowledge about future developments concerning European CCS). As these future developments may have the potential to restructure existing markets, cautious publishers might be reluctant to put additional effort into direct memberships but rather wait for European-wide harmonized solutions, like ICE. However, the focus of such joint ventures to date has been exclusively on online rights. While these represent a key source of revenue, they are only a fraction of all the copyright-types that a CCS can represent. A more objective alternative would therefore be to examine which territories are covered by the already authorized CCS and which types of rights are already represented in these territories, and then to optimize in terms of costs and time-efficiency.

7 Opportunities

Direct memberships with foreign CCS can contribute to a better copyright exploitation process in various ways. As being potentially lucrative it is an entrepreneurial opportunity for publishers, following the definition of Short et al. (2010). This section will first discuss improvements derived from a direct membership which are immediately beneficial to a publisher after joining a foreign CCS and subsequently the opportunities which a publisher may develop and exploit in the long-term view.

7.1 Short-term view

Before the positive effects of a direct membership can be taken advantage of by a music publisher, an economic analysis of the target market should precede, evaluating the currently chosen way for exploitation. Only if the published works already enjoy great popularity in the target market due to their characteristics or promotional work, migrating from the current exploitation option to a direct membership will make sense from an economical point of view (see also Sect. 5).

“Sure, I would say you have to look at each country individually, see what kind of sales you are doing or have done in the past and then evaluate the revenue in that country, if it’s worth the effort to become a member of that country and register everything yourself and so on or if the revenue is simply too small, so that you say, then [the domestic CCS] should continue to collect it. (P3:54)”

The first advantage of direct memberships for music publishers is increased transparency, which is supported by various developments: First, transparency is increased by disintermediation as the direct relationship to a single CCS makes data transfers of royalties less complex and easier to document. Second, as with any outsourcing solution, there is an encapsulation of tasks resulting in less transparency, which would be counteracted through insourcing. Furthermore, statements of domestic CCS concerning foreign royalties are less transparent, while statements received directly from a CCS may list royalties in direct allocation to uses. The interviewees describe this situation as follows:

“Unfortunately, [the domestic CCS] is not transparent about the payments as we expect it to be and with direct membership in the [foreign CCS] it is simply more transparent. We get an amount X and details on what took place and where. (P6:48)”

“It’s just that if we hadn’t done this now, we would get an amount X which we can’t even assign [...] and if we are a direct member, we get a detailed statement [...] (P6:54)”

Due to the greater transparency, there is also greater certainty about the correctness of royalty statements, which could reduce complex communication chains.

“But it is of course already so, if I have the feeling that, for example, a sub-publisher delivers a statement of account that does not seem plausible to me and does not come round the corner with a proper explanation, then I naturally contact the respective collecting societies and make sure that I get the information from them that I did not get otherwise. (P3:64)”

In summary, direct memberships can improve copyright exploitation for music publishers regarding transparency, time and costs of transactions. Based on this factors, music publishers can focus on an improved service quality.

7.2 Long-term view

As a direct member the publisher neither depends on the service of sub-publishers nor on the domestic CCS with representation agreements. This comes with increased responsibility, but also gives the chance to offer a better service to clients. Successfully addressing additional challenges like language barriers and market specifics (cf. Sect. 6) makes publishers more attractive for authors located in the region of the foreign society. In addition to economic advantages and increased transparency, as a member of a CCS publishers can influence decision making processes and thus advance a needs-based development of the CCS.

Some services, such as usage reports, complaints, cessions and inquiry-lists are only available for direct members and cannot be implemented through a reciprocal representation agreement with another CCS. For publishers, direct memberships simplify access to these services, leading to an extension or increased efficiency of services for its represented writers in return.

“At PRS – I think that’s very nice – they have these inquiry lists that GEMA has for sync and TV, PRS even has to live. These are things that I find very attractive. (P5:61)”

“It is limited to asking whether they accept assignments granted to non-members. So when we sign Dutch or Australian authors, we ask the collecting societies if they accept cessions – so if there is an advance – cessions from a GEMA member and that is an interesting process. (P5:77)”

For example, data available in a less aggregated form allows for deeper analysis, which can serve as a starting point for improving the publisher’s strategic decisions, for optimizing marketing activities or for a simpler and fairer distribution of royalties. Moreover, the review of statements and the possible necessary creation of complaints can be done in a more effective and efficient way.

In addition, music publishers can increase their competitiveness by expanding their core business by becoming sub-publishers in foreign territories themselves – a trend already evident in the interviews.

“We were progressive enough to say that we are now a direct member of SUISA, so we also offer sub-publishing services for Switzerland. (P1:156)”

To make use of the opportunities, publishers need to address the challenges and overcome the obstacles described in Sect. 6. This is certainly not an easy task and requires corresponding economic strength as well as other resource advantages. If these conditions are met, publishers can use direct memberships to expand and improve their core competencies, create new service offerings and thus gain competitive advantages. To facilitate the exploitation of these opportunities, the necessary external enablers must be available, such as technological advances addressing these challenges.

8 Technology as a solution

In order to support the exploitation of the above-mentioned opportunities, the identified challenges must be addressed appropriately. In the following, two use cases illustrate possibilities of technological support.

As a first technological prototype, we present a tool to compare the commonly reported financial characteristics of European CCS. As Sect. 5 exemplifies, choosing between the different exploitation options is a necessary task. As explained in Sect. 7, in the future such tasks could become even more relevant. The tool addresses organizational challenge 4 (heterogeneity of CCS performance, cf. Sect. 6.1) and supports the decision making process of publishers for direct memberships.

A second prototype focuses on the registration of works as a specific task of particular interest for publishers in collaboration with CCS. This software addresses various challenges introduced in Sect. 6. First, it reduces the additional effort connected with direct memberships with foreign CCS, as it is a scalable solution for registering works (organizational challenge 1). Second, although a data standard for registering works exists,Footnote 17 it is not followed consequently (technological challenge 1). Third, the creation and verification of files is supported by this tool (technological challenge 2).

8.1 Use case “Evaluating CCS”

As described in Sect. 5, various selection criteria are relevant for the decision to become a direct member of a CCS. Music publishers are supported by comparing the introduced KPIs (see Sect. 4.2.1). To simplify this process, a web-applicationFootnote 18 was developed (see Fig. 5), providing three analysis options. The first option allows for a comprehensive view of relevant KPIs of a specific CCS. This view is suitable for evaluating a CCS of an already targeted market, driven by the idea of joining the CCS as a direct member. It provides a summarizing alternative to viewing the annual report of the CCS, focusing on key facts.

As a second option, the tool provides an evaluation of CCS performance by sorting and ranking CCS with respect to a specific KPI. For example, the KPI cost rate can serve as an indicator of the efficiency of CCS processes. Figure 6 shows both the three lowest and the three highest cost rates of the investigated sample, detailing the analysis in Sect. 6.1.

As a third option, weighted rankings of CCS allow for identifying possible correlation between two selected KPIs. As an example, an analysis of the licensed music use per capita can support the decision of a publisher to tap into a new market. This question is targeted by analyzing the royalty turnover of the respective CCS weighted against the population of its country (see Fig. 7).Footnote 19 By combining further KPIs, various additional analysis is feasible (e.g., “number of copyright holders per employee” or “paid royalties per copyright holder”) allowing further comparative conclusions.

This section presented a tool to support a publisher’s strategic decision to become a direct member of a CCS by making CCS economic performance transparent (organizational challenge 4). The tool is subject to various limitations which are described in Sect. 4.2.2. Continuously updating the database with current CCS KPIs would allow music publishers to assess the continuity of CCS performance. Also, differentiating between different copyright categories and types would support publishers to strategically align CCS with their business goals. These features would greatly objectify the decision process of whether to invest time, effort and money in a direct membership with a CCS or to retain the current intermediary exploitation option.

8.2 Use case “Registering Works”

According to the common expectation of digitalization, IT-tools can foster efficiency and effectiveness of various work tasks in many aspects. Furthermore, supporting technology is positively influencing the likeliness of exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities (Choi and Shepherd 2004). Nevertheless, technological solutions must fulfill some conditions to achieve optimal results:

-

To provide a basic understanding between various actors, transferred data should adhere to a generally accepted format.

-

In order to avoid media discontinuity, all actors involved must offer digitally accessible interfaces.

-

To allow for an extensive automation, the addressed processes should ensure a minimum degree of uniformity and frequency of execution.

As not all examined processes meet these requirements to an equal extent (e.g., becoming member in a foreign CCS is usually a one-time task), it can be assumed that software is not an equally effective approach for all identified challenges. The following characteristics illustrate why we chose the registration of works process as a case study to be supported by a software prototype:

-

Scaling: Whereas it is possible to register new works using e-mail or online forms, it becomes a tedious and error-prone process when registering hundreds or thousands of works. Since the repertoire managed by a publisher is typically on a larger scale, a manual process is not feasible.

-

Repetition: The composition of new works is predominantly an ongoing process. New works have to be registered at collecting societies or transferred to sub-publishers on a regular basis. Improvements in this area are therefore not limited to a single, concluding action.

-

Standardization: Driven by the previous two arguments and a rather long history of transferring work data between publishers, the CISAC developed CWR (Common Work Registration), a standardized data format describing various aspects relevant for musical works (Zetterlund 2011). Since a broad variety of stakeholders accept this data format for describing work-relevant metadata, a rather uniform way of data exchange could be expected.

-

Interfaces: An initial, basic investigation found widespread use of e-mail or FTP servers for exchanging CWR data. Although newer, more advanced technological options exist, this path meets the minimum technological requirements, as it at least prevents media breaks.

Thus, this example serves as a good starting point with manageable technological complexity, while at the same time offering great benefits and a wide application potential. Furthermore, the market offers only a few alternatives.Footnote 20

Various aspects of the CWR file format played a role in the interviews. On the one hand, the relevance of this format not only for the exchange between publishing partners or CCS, but also for the exchange with other platforms and service providers was emphasized.

“Also many other platforms and service providers, for example Lyricfind, can also be supplied with CWR. And of course, large catalogs have to be delivered in the adapted formats to collecting societies in case of direct memberships. (P1:96)”

On the other hand, various statements indicate challenges to be expected when dealing with the CWR format. First, this is a repeatedly mentioned lack of compatibility of CWR-files exchanged between different stakeholders, which often results in the necessity of manual corrections.

“And the problem is simple with this CWR story – although it’s called Common Work Registration it’s not common at all. Because no matter where you do it, it’s never right for the country in question. You still have to manually add or remove things. (P4:113)”

It is irrelevant whether the partners of the data exchange are publishers or CCS, the challenges remain the same in both cases. As there is actually a maintained, published and documented standard, the problem is initially surprising from a technological perspective, since it is precisely these problems that standardization is intended to solve – a surprise that the publishers share.

“What seems to be a huge effort is to get data from GEMA, i.e., verified data that can be used. We hear again and again from foreign publishers that the data is not quite compatible, although there is this CWR format. I always don’t understand why this is so problematic. (P7:63)”

A further challenge is the lack of tool support for tasks following the pure exchange of data. According to the standard, the registration of new works is also confirmed with a CWR summarizing information about success or failure of the registration. Due to a lack of IT support, it is not possible for publishers to analyze this feedback, which in turn makes any corrective action that may be required impossible.

“And now we get registration confirmations via CWR back, we can’t read that at all. Yes, we can’t check if this is really correct (P1:134)”

In summary, the use case of registering or transferring work data has great potential and practical relevance, but also presents numerous technological and organizational challenges, which exemplify the difficulties that new ways of exploiting copyrights raise for publishers.

8.2.1 CWR-Validator

Driven by the interview statements we developed a tool for validating CWR files. Based on the described needs and challenges, the functional goals were:

-

A strict and comprehensive validation against the published standard to assess the correctness and completeness of CWR files,

-

A structured and clear representation of the file contents including registration feedback, as the readability of extensive, fixed-length text-based files is limited,

-

And an understandable and detailed description of occurred validation messages to support the creation of valid CWR files.

The prototype was implemented as a desktop application for Windows. The user interface is divided into four parts (see upper part of Fig. 8). First, the Import Log lists information, errors and warnings regarding the process of reading the file. Second, the results of the actual check of the CWR file is shown in the Validation Result tab, including some metadata such as the violated rule. It is also possible to get a listing of the violation causing works with line numbers and description to support manual corrections. The third tab displays the data of the CWR file in a structured manner along with the validation messages (see lower part of Fig. 8). Finally, the fourth tab allows for an export of the CWR data along with the validation messages to a JSON formatted file.

8.2.2 Evaluation

A practical evaluation was carried out with ten publishers using this tool for testing purposes. The feedback was positive regarding various aspects of the user interface, but also showed the consequences of not strictly following standards. The central point of criticism was that due to the numerous violations of the standard in their CWR files, the high number of validation messages had a negative impact on the clarity of the validation results. Since different communication partners often ignore or even cause certain violations of the standard, the display of all validation messages made it difficult to identify “relevant” errors.

Although relevance and meaningfulness of all rules may not be apparent at first glance, the complete advantages of a standard can only be exploited through its essential prerequisite – a uniform interpretation. Unless a majority of stakeholders in the industry comply with this fundamental principle, the problems described in the interviews cannot be avoided. Since addressing the root cause of the problem is a challenge beyond the scope of a research project, a technological workaround was developed. According to the feedback of the evaluating publishers and assuming the freedom of interpretation of the standard as given, the feature to filter certain types of validation messages was implemented. Additionally, reasonable presets covering known individualized interpretations of the standards were included.

The evaluation revealed that strict conformity to the standard is not the main objective of the music industry. Instead, the pragmatic approach of the publishers is: 100% validity is not necessary, it is sufficient to be as valid as needed so that further processing by partners is possible. Although at first sight this seems to be a valid tactic, a more holistic perspective shows the connection between this approach and the above-mentioned problems. A standard is only useful as long as all stakeholders comply with it.

As the use cases illustrate, software has the potential to address these problems. However, fundamental solutions require changes on an organizational, political level, which are difficult to achieve in a heterogeneous environment consisting of numerous independent actors. The fact that publishers are taking the direct membership route despite these difficulties shows its potential as well as the needs of the industry. In the future, additional case studies may expand the scope of our research by implementing software that supports other processes, including importing, reviewing, and correcting music usage information.

9 Economic potential of technological solutions

In the previous chapters, technological solutions were presented which aim to support small-to medium-sized publishers in taking the entrepreneurial step toward direct memberships in foreign CCS. Table 10 presents three technological approaches for implementing this entrepreneurial opportunity.

Using approach A, the publisher authorizes the CCS directly, saves the costs for sub-publishers and reduces the latency between licensing and royalty payment at the same time. Negative effects occur at the interorganizational interface – insufficient integration of processes and an increase in manual work lead to higher error-proneness and lower process efficiency. The majority of the publishers surveyed follow this approach.

Approach B is characterized by a software supported reduction of manual tasks which in turn increases process accuracy and efficiency. No comprehensive software solution has been implemented yet; rather single, particularly complex tasks are supported by software tools. There are costs for developing and maintaining the software, and publishers would increase their dependence on software suppliers or developers.

In approach C, technology service providers deliver software that enables the management of the entire interorganizational process, starting with the initial membership application, the management of rights assigned to the CCS, work registrations, and all other processes at the interface to the CCS (cf. Fig. 1). These providers act as a hub to the various CCS, so that the exchange of data can be carried out efficiently by applying economies of scale, supported by technological solutions. On the other hand, there is limited independence, since the publisher may now receive more favorable conditions than with a sub-publisher, but at the expense of the individual support of its artists. Furthermore, the dependence on the sub-publisher is substituted with the dependence on the service provider. In contrast to technology-centered publishing administrators such as Songtrust or Kobalt, this approach would allow the publisher to establish direct contractual relationships with CCS of their choice to build their own network based on their needs (cf. Sect. 5). While potentially saving administrative costs, the publisher is also closer to the CCS and can take advantage of the opportunities identified in Sect. 7. As of today, no such solution exists according to the best knowledge of the authors.

As noted above, publishers’ freedom of choice to authorize CCS directly applies equally to writers and any other eligible copyright holder within the EEA.Footnote 21 However, they are facing similar challenges as the publishers (cf. Sect. 6). Due to the conflicting nature of administrative and artistic activities, it can be assumed that writers will tend to focus on the latter, even if the availability of technological support lowers the barriers of direct memberships (approach B). However, a more widespread use of convenient technological services that act as a hub between CCS and copyright holders would have the potential to cause a shift in this respect (approach C).

10 Conclusion and future perspectives

The aim of this paper was to outline the entrepreneurial opportunity of direct memberships of publishers in multiple international copyright societies along with its challenges, opportunities and possible technological solutions. We focused on the underlying economic motivation and requirements of publishers, highlighted the heterogeneity of economic performance of CCS, differences and commonalities in processes and data and proposed technological solutions supporting the alignment of publishers’ needs with current CCS practices.

With our findings, we aim to draw a comprehensive picture of the trend toward direct international copyright management. Despite the extra work involved, a growing number of small- and medium-sized publishers took advantage of this opportunity, motivated mainly by the expectation of economic improvements and driven by the urgency to find international compatibility, especially due to a changing, more international market.

Since this study only marks the outset, a few fundamental questions are yet to be answered. First, in a follow-up study, the qualitative findings are to be translated into quantitative backed statements to allow for more general conclusions to be drawn. Second, since most of the publishers interviewed choose to become members of CCS based more or less on subjective estimates rather than on concrete objective measures, a thorough economic assessment is necessary, examining the conditions and best practices necessary to make this step profitable.

As the study shows, organizational and administrative barriers for direct memberships nowadays are quite high due to heterogeneous processes and data formats as well as varying organizational rules and legal frameworks. As a consequence, publishers focus only on their most important markets. Technological solutions might support further developments. The findings regarding process models and data formats support the deduction of abstract processes and formats, which in turn can contribute to the implementation of generic tools supporting multiple CCS. Software that simplifies interaction with multiple CCS supports a more widespread adoption of direct memberships, extending it to smaller markets as well. Likewise, it could also become an option for small publishers or other copyright holders like composers or authors. In order to lay the theoretical foundation for the implementation of software solutions, the technological requirements needed for a fully integrated solution have to be further detailed in follow-up studies.

One starting point might be to examine existing solutions from technology-driven publishing administration companies; the life cycle of publishers’ interaction with CCS outlined in Fig. 1 could also be used as a structuring basis.

A further factor of uncertainty is the ongoing, but very slowly progressing organizational changes in the market of CCS. Partnerships or joint ventures such as ICE may indicate movement in a long time predominantly very static sector, although the implications for the day-to-day business are yet to be determined. Nevertheless, aggregation tendencies on the CCS side may render the construct of multiple direct memberships obsolete. So far, however, these aggregations have focused only on online rights, and current practice demonstrates the urgent need on the part of publishers for more rapid development.

If the focus is on competition rather than consolidation, an interesting point for future research is to evaluate which factors are beneficial in terms of the efficiency and effectiveness to better understand the reasons for heterogeneity of CCS. To what extent do CCS implement efficiency-oriented strategies? What are success factors and best practices?

Although technology is not the driving factor for the rise of direct memberships yet, it is an enabler to support, spread and intensify this trend among publishers. An obstacle to wider acceptance of the direct membership model is in many cases the increased administrative effort required, which publishers are currently prepared to bear in only a few core markets. As the proposed prototypes show, technology can address this challenge and, thus, support this trend. Likewise, reducing transaction costs enables an entrepreneurial return. New organizational structures or technological systems will support that development (Foss and Foss 2008). In addition, even if publishers are currently primarily concerned with improving copyright management for their repertoire, an increased offering of exploitation services for other publishers can be expected in the future – cross-national sub-publishing provided by one publisher. This service can be considered as a further entrepreneurial opportunity, compensating the increased effort of direct memberships by new exploitation options.

We hope that the results presented will help to gain an initial understanding of this trend, as well as draw attention to this growing field, thereby encouraging technological and organizational developments that support publishers in their role as international entrepreneurs.

Data availability

The tools and many raw data such as process models can be found on the research group’s webpage https://creativeartefact.org and on the project’s webpage https://soclear.de.

Code availability

The tools and further information can be found on the research group’s webpage https://creativeartefact.org and on the project’s webpage https://soclear.de.

Notes

The distribution of international performing rights by the German CCS GEMA can be taken as an example for delayed payments, e.g., Australian performing rights from 07/2018 until 06/2019 are paid off on July 1, 2020 (https://www.gema.de/en/music-authors/royalties/pay-outsdistribution-of-international-income/international-performing-rights-2020/).

For the sake of simplicity, sub-publishing in this context refers to all contractual relationships like co-publishing or administration agreements as well, since the business structure – an additional entity within the process – remains the same.

Although most traditional European CCS support only a membership model in which control over the operation of the CCS is granted to the members, there is increasing support for purely commercially motivated models, in which copyright holders are merely clients or principals of the CCS, e.g., in so-called independent management entities. Because the study focused on traditional CCSs, and to minimize the terminological variety used in this paper, the term “direct membership” includes these options.