Abstract

The classification of life forms into a hierarchical system (taxonomy) and the application of names to this hierarchy (nomenclature) is at a turning point in microbiology. The unprecedented availability of genome sequences means that a taxonomy can be built upon a comprehensive evolutionary framework, a longstanding goal of taxonomists. However, there is resistance to adopting a single framework to preserve taxonomic freedom, and ever increasing numbers of genomes derived from uncultured prokaryotes threaten to overwhelm current nomenclatural practices, which are based on characterised isolates. The challenge ahead then is to reach a consensus on the taxonomic framework and to adapt and scale the existing nomenclatural code, or create a new code, to systematically incorporate uncultured taxa into the chosen framework.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Naming and classifying the world around us is a natural human prerogative for effective communication [1]. With regard to the biological sciences, formal structures first arose in the 1700s through the work of Linnaeus [2]. Linnaeus introduced the principles of modern biological taxonomy (arrangement of plants and animals into hierarchical categories) and nomenclature (rules for naming taxonomic groups of plants and animals), which today form the basis of biological classification. Originally taxonomy was based on shared properties (chiefly anatomical, but also biochemical and physiological), developmental processes (e.g., live birth vs. eggs) and behaviours (e.g., flight), later collectively termed phenotype to distinguish these features from hereditary information (genotype) [3]. This intuitively reflected the concept of common ancestry even though evolutionary theory had yet to be developed at the time of Linnaeus. This works quite well for animals and plants with a few celebrated red herrings, such as the long-held belief that hippos were most closely related to pigs based on anatomical similarities; genotype indicates that they are actually more closely related to whales [4]. Phenotype was also used for decades to classify microorganisms despite much less conspicuous morphological and developmental traits than animals and plants [5]. However, phenotype provides little insight into deep evolutionary relationships of microorganisms, which can only be discerned by comparison of conserved information-bearing macromolecules [6]. Moreover, the realisation that most microbial diversity had been overlooked because most microbes cannot easily be grown in the laboratory has further hamstrung microbial classification [7,8,9]. This review concerns microbial taxonomy and nomenclature with a primary focus on Bacteria and Archaea, from an historical perspective to modern day, and an exploration of how recent advances in culture-independent genome sequencing may be harnessed to provide a comprehensive and systematic classification of the microbial world.

Taxonomy: improving the framework

Taxonomy is most commonly defined in biology as the branch of science, which names and classifies organisms based on shared properties [10, 11]. However, here we define taxonomy according to its original Ancient Greek derivation as táxis for ‘order or arrangement’ and nomos meaning ‘law’ typically manifested as a hierarchical structure or framework in biology. We specifically exclude nomenclature from this definition, i.e., formal naming schemes and rules, which govern them, discussed separately below. We do this because taxonomy (thus defined) and nomenclature can and have operated independently, particularly in microbial classification, which can create conflicts (see below).

Taxonomy can be based on any combination of properties; however, beginning with Darwin’s recognition of common descent, biologists now agree that taxonomy should be based on evolutionary relationships as the most natural way of arranging organisms [12]. In this regard microorganisms have until recently been the most problematic taxa to arrange in a phylogenetic framework because their phenotypic properties for the most part do not reveal their common ancestry [6].

Phenotypic classification

The first modern attempt to systematically classify bacteria based on their phenotypic properties began with the first edition of Bergey’s Manual of Determinative Bacteriology in 1923, which categorised bacteria into a nested hierarchical classification to indicate differing levels of relatedness. Initially this comprised from highest (most distantly related) to lowest (most closely related) rank; class, orders, families, tribes, genera and species based on identification keys and tables of distinguishing characteristics [13]. The keys relied heavily on morphology, culturing conditions and pathogenic characters with the primary goal being practical identification of isolates at the species level rather than constructing an evolutionary framework. Numerical taxonomy, proposed by Sokal and Sneath in 1962 [14,15,16], provided a mathematical basis for quantitative comparisons of phenotypic properties between bacteria typically incorporating dozens of features. Although in principle, numerical taxonomy could incorporate phylogenetic information, in practice it was used primarily for identification and lacked a rigorous evolutionary framework. A heartfelt acknowledgement of the limited evolutionary resolution afforded by phenotypic characteristics was made on numerous occasions by Stanier and van Niel in the 1940s–1960s [17,18,19], where they concluded that it was a waste of time for taxonomists to attempt a natural system of classification (i.e., one based on evolution) for bacteria. However, it was during this period that the path forward to breaking the phenotype impasse was predicted by Zuckerkandl and Pauling through the use of informational macromolecules that could act as molecular clocks to infer evolutionary relationships [20].

Small subunit ribosomal RNA, the molecular pioneer of microbial classification

Inspired by the work of Zuckerkandl and Pauling, Woese began a search for a molecular chronometer that could form the basis of an evolutionary framework for all life. He landed upon the ribosome as a good candidate, most famously the small subunit ribosomal RNA (16S/18S rRNA) contained therein, due to its high sequence conservation holding together the structural core of the ribosome, interspersed with variable regions not under the same exacting selective pressure. The combination of these properties make small subunit rRNAs useful molecular clocks with both an hour and minute hand to measure ancient and more recent relationships [21,22,23,24]. Several other DNA-based classification methods have been developed over time, including DNA–DNA hybridization [25, 26], DNA G + C content [27, 28], pulsed-field gel electrophoresis [29, 30], and more recently multilocus sequence typing [31, 32] and multilocus sequence analysis [33, 34]. However, like their phenotypic predecessors these methods are not useful for deep phylogenetic reconstructions, whereas comparative analysis of small subunit rRNAs is able to provide an objective evolutionary framework across the tree of life. The highlight of Woese and his colleagues’ analyses was the discovery of Archaea [21] completely overlooked by identification keys because of the inability to frame phenotypic properties such as methanogenesis in the correct phylogenetic context [35].

The 16S rRNA gene was also instrumental in highlighting the enormous amount of microbial diversity missed by culturing methods [7, 11, 36]. Pace and colleagues were the first to characterise microorganisms via their 16S rRNA sequences obtained directly from the environment through the ingenious use of highly conserved ‘universal’ primers broadly targeting this molecule [22]. These primers were subsequently used to PCR-amplify 16S rRNA genes from extracted genomic environmental DNA. Mixed amplicons were then cloned and sequenced to provide profiles of the in situ microbial community [37]. As sequencing technologies improved, the cloning step could be omitted, and thousands of samples from dozens of habitats were readily profiled [38,39,40], which brought with it a plethora of databases and tools for analysing and classifying 16S rRNA gene sequences (Table 1). By the end of the 1990s, the redefining of prokaryotic taxonomy through the lens of 16S rRNA sequences was sufficient to induce Bergey’s Manual Trust to transition from traditional phenotype-based classification to a 16S rRNA-based phylogenetic framework in the second edition (2001–2012) of Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology [41].

Polyphasic taxonomy emerged as an approach to integrate phenotypic and genotypic characteristics in order to produce a consensus taxonomy that best reflected the many and varied attributes of biological organisms [10]. The original definition of polyphasic taxonomy by Colwell in 1970 predated and made no reference to phylogenetic inference, but with the advent of 16S rRNA analysis, phylogenetic classification rose to prominence [42]. Due to the high sequence conservation of the 16S rRNA gene, polyphasic taxonomy was stratified such that 16S rRNA trees informed classifications at and above the rank of genus, whereas species and subspecies level delineations were better accommodated by chemotaxonomic methods such as multilocus enzyme electrophoresis and whole-cell protein analysis, and more recently by comparison of genome sequences [26, 42, 43]. The advent of whole-genome sequencing, and its rapid acceleration in recent years due to technological advances has provided increasing impetus for bacterial and archaeal taxonomy to transition again, this time from a 16S rRNA-based to a genome-based classification [44, 45].

Genome-based classification

As with the 16S rRNA gene, genome sequences can be used to construct a robust phylogenetic framework on which to base a systematic classification [44]. Enormous advances in both high-throughput sequencing and high-performance computing have enabled sequenced genomes to form the basis of a classification framework. Genome-based classification affords greater resolution than the 16S rRNA gene (which represents only 0.05% of an average 3-Mbp prokaryotic genome) for both the most ancient and most recent relationships due to a larger fraction of the genome being used in the comparison, which provides an improved phylogenetic signal [46,47,48]. However, since most gene families have some history of horizontal gene transfer between organisms, genome-based phylogenies typically use a subset of conserved vertically inherited genes as the basis of the inference [49,50,51]. A notable exception is the rank of species for which methods using much greater fractions of the genome have been developed (Box 1). Two main approaches exist for building evolutionary trees from genome sequences; supertrees and supermatrices. In the construction of supertrees, independent gene trees are created and then combined to produce a single, consensus estimate of phylogenetic relationships between organisms [52,53,54]. Supermatrices involve concatenating genes into a single phylogenetic matrix of aligned sequences from which the tree is then inferred [47, 55,56,57]. Both methods have been used successfully to infer phylogenies across the tree of life, and in a recent direct comparison of a bacterial supertree and supermatrix, had a 98.2% taxonomic congruence despite being based on different sets of marker genes [58]. Other classification methods, which make use of genome sequences include similarity measures between pairs of genomes either at the level of encoded proteins (average amino acid identity) [59], or nucleotides (average nucleotide identity (ANI)) [59, 60] and digital DNA–DNA hybridisation [61, 62]. However, these methods do not use an explicit evolutionary model like supertrees and supermatrices and are used primarily for defining and identifying species (Box 1).

Like 16S rRNA sequences, genome sequences have been extended into the uncultured domain via shotgun sequencing of environmental samples. This metagenomic approach has also benefitted greatly from improvements in sequencing and computation, and today it is possible to recover near-complete or even complete genome sequences of naturally occurring microbial populations from environmental DNA, so-called metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) [63,64,65]. Indeed, the number of available MAGs is rapidly eclipsing the number of isolate genomes due to the relative ease of obtaining multiple MAGs from a single metagenome [9]. In instances where retrieval of genome sequences of low abundance or heterogeneous populations from environmental samples is not feasible, single cell genomics has advanced to the point where single-amplified genomes (SAGs) can represent such taxa [8, 66, 67]. This rapid accumulation of genome data from uncultured taxa raises an enormous challenge for classification, both in terms of taxonomic placement and nomenclature (see ‘Nomenclature: controlling the vocabulary’). It is estimated that uncultured taxa represent upwards of 85% of microbial diversity according to Faith’s phylogenetic diversity metric [8] meaning that taxonomic frameworks established over previous decades have major gaps in them. This issue is even more pronounced in the viral world with a recent estimate of 1031 bacteriophage in the environment represented by only a few thousand sequenced genomes [68].

It is widely recognised that prokaryotic taxonomy is riddled with phylogenetic inconsistencies (polyphyletic taxa) due to historical use of phenotypic data [69], chimeric 16S rRNA gene sequences from PCR-based environmental surveys [70], and premature conclusions based on phylogenetic reconstructions lacking suitable outgroups [71]. These problems have been compounded by the tidal wave of gene and genome sequences from uncultured taxa. Consequently, several databases and tools have been developed to try to address these shortcomings through the establishment of robust phylogenetic frameworks for microbial classification, firstly using 16S rRNA gene sequences, and more recently using genome sequences (Table 1). All of these resources face the same technical challenge of having to compare hundreds of thousands of sequences to each other to provide a global view of microbial diversity, which is difficult for individual genes and more so for genomes. However, common features of successful resources include computationally cheap dereplication of sequences and inference of a robust and scalable evolutionary framework. Whether these resources continue to scale with the rapidly increasing sequence database remains to be seen.

Historically, definition of ranks based on phenotypic data has been highly subjective, particularly for ranks above species. The introduction of gene and genome-based classification has provided the opportunity to define genus and higher ranks based on objectively quantifiable sequence similarities. In 2014, Yarza and colleagues proposed standardised thresholds for defining prokaryotic lineages from genus to phylum based on 16S rRNA gene sequence identities [11]. While certainly removing many inconsistencies in existing taxonomic classifications, and having the benefit of accommodating uncultured taxa, this approach does not take into account phylogenetic relationships and variable rates of evolution between lineages. As such, fast-evolving groups with more divergent 16S rRNA sequences are classified in higher than expected ranks, such as mycoplasma bacteria which constitute two phyla by this identity-based criterion. Vertebrate-associated mycoplasmas, however, are estimated to have diverged from their arthropod-associated sister lineage (ureaplasmas) only 400 Mya, which is much later than the estimated primary diversification of bacterial phyla (2–3 Gya) [44]. This issue can be offset by use of relative evolutionary divergence (RED) distances, which normalise for variable substitution rates across a phylogenetic tree [44]. After RED correction on a concatenated conserved marker gene tree, mycoplasmas were classified into a single order within the phylum Firmicutes more consistent with their estimated time of divergence from ureaplasmas, suggesting that this approach may be better suited for systematically defining higher ranks than uncorrected identity thresholds [44].

Finally, it is important to note that there is no official prokaryotic taxonomy to ensure freedom of taxonomic opinion, but also because underlying technologies used to define taxonomic hierarchies have been changing so rapidly [1, 72]. However, different taxonomies incorporating named prokaryotic isolates have been effectively linked through an official nomenclature.

Nomenclature: controlling the vocabulary

The development of nomenclatural codes

Nomenclature, the business of systematically naming things, was first proposed for biological entities (plants and subsequently animals) by Linnaeus in the mid 1700s in which he introduced the concept of a taxonomic hierarchy (described above). Most famously this included the binomial nomenclature system comprising the two lowest canonical ranks: genus and species [73]. His work became the foundation for hierarchical taxonomy in both botany and zoology with the establishment of nomenclatural codes over 100 years later, most recently called the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi and plants (ICN or Botanical Code) founded in 1867 and International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (Zoological Code) founded in 1905, in which a set of rules for naming plants (and algae and fungi) and animals was laid out and controlled by elected committees of experts. Until 1947, microorganisms had been predominantly classified under the Botanical Code because bacteria had traditionally been considered fungi [74, 75]. In 1930 at the First International Congress of Microbiology in Paris, it was proposed that bacteria and viruses should have their own code, resulting in the Revised Edition of the International Code of Nomenclature of Bacteria and Viruses in 1958, today called the International Code of Nomenclature of Prokaryotes (Prokaryotic Code) [76] to reflect the inclusion of archaea and removal of viruses [77] (Fig. 1). One notable exception is the bacterial phylum Cyanobacteria, which is still mostly classified under the Botanical Code due to the association of oxygenic photosynthesis with plants (Box 2). Additional codes have been proposed for specific subsets of taxa including cultivated plants (ICNCP; 1952), viruses (ICVCN or Virus Code; 1966) and plant associations (ICPN; 1976) resulting in the six International Codes recognised today each controlled by a committee of experts (Fig. 1). The Prokaryotic Code is unusual amongst these codes in that its nomenclature was effectively rebooted in 1980, whereby all bacterial names proposed to that point were made null and void due to the high number of synonyms and inadequate or non-uniform descriptions, and an ‘Approved Lists of Bacterial Names’ was established. Names not on those lists lost their standing in nomenclature [78]. All codes have in common the use of type specimens or strains, which serve as a permanent reference for a given species name. However, what constitutes type material (Box 3), the specific ranks used, and rules governing how names are established for each rank vary markedly between the different codes [76, 79, 80]. For example, the Prokaryotic Code requires all names be treated as Latin regardless of their origin and that ranks above genus be based on the stem of the type genus name [76]. By contrast the Virus Code only requires that names be alphabetical, and most recently proposed that higher ranks cannot be based on lower rank names [81, 82].

The complexity of multiple nomenclatural codes and sometimes conflicting application of rules even within one code led to proposals for unification and simplification of the different codes. A leading contender was the Biocode, which proposed to harmonise all biological nomenclature codes under a unified Code largely based on the rules of the Botanical Code [83,84,85]. However, it was met with a great deal of opposition due to the implicit loss of control by existing nomenclatural committees, and potential confusion created by harmonisation of terms that have different meanings for different codes [86, 87]. A revised draft was published in 2011 but continues to lack consensus support [88]. Another major contender for a unified nomenclature was the PhyloCode proposed in 1998 [89,90,91,92], which provided rules for naming clades and species through explicit reference to a phylogeny without the need for a hierarchical taxonomic framework. The plan was to use PhyloCode in parallel with existing Linnaean-based codes, with the goal of replacing them at a later date. In principle, phylogenetic trees provide precise coordinates for taxa, making a classification based on a hierarchical taxonomy redundant [93]. However in practice, uptake of the PhyloCode has not occurred highlighting the reluctance of biologists to move away from the Linnaean system.

(Lack of) nomenclature for uncultured diversity

Detailed molecular characterisation of uncultured microorganisms is a relatively recent innovation due to technological advances (see 16S rRNA and Genome-based classification). Such organisms pose a challenge to the Prokaryotic Code as their names cannot be validly published since species descriptions must be based on pure cultures of type strains (Box 3) and as a consequence they have been outside the rules of the Code [45, 76]. This has resulted in the widespread use of alphanumeric placeholder names for uncultured taxa, which is unregulated and has led to frequent synonymous naming, e.g., Marine Group A/SAR406 [7, 94], GN02/BD1-5 [95, 96] and CD12/BHI80-139 [8]. An early nomenclatural stop-gap for uncultured taxa was proposed in 1994 through the introduction of the provisional status of Candidatus [97, 98]. The word Candidatus is prefixed to a common name of any rank to indicate the provisional nature of the taxon and has no standing in prokaryotic nomenclature, and therefore no requirement for correct etymology or nomenclature type. Consequently, many Candidatus names do not conform to the Prokaryotic Code [99, 100]. Despite these shortcomings, no other proposals have been adopted to accommodate the formalised naming of uncultured taxa, and Candidatus has not been widely adopted representing only 4.9% of the 45,414 prokaryotic taxa in the Genome Taxonomy Database (Table 1 and Fig. 2).

Total number of taxa per rank are shown below each rank name. Most recognised prokaryotic taxa only have placeholder names, and the majority of these fall outside the Prokaryotic Code because they lack cultured representatives (Box 3). Only 7.2% of this excluded fraction have adopted the nomenclatural provisional status of Candidatus. The proportion of validly named taxa (Latin names) is likely to fall as MAG sequencing overtakes isolate sequencing. Note that there are no validly published names of phyla as the rank of phylum is not (yet) covered by the rules of the Prokaryotic Code [122].

Candidatus was originally proposed [98] with 16S rRNA environmental surveys in mind. It was expected that their descriptions would be limited in scope compared to isolates, comprising one or at most a few gene sequences, habitat origin (and inferred temperature range) and cell morphology if 16S rRNA-targeted fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) had been successfully applied [36, 97, 101]. However, with the advent of near-complete or even complete MAGs and SAGs [65, 102], and a plethora of techniques able to describe a microorganism’s function without the need for isolation, or even enrichment [103], a Candidatus species can be described in great detail. In 2016, it was proposed that gene sequences serve as type material since they are able to provide unambiguous reference points for nomenclature, particularly whole-genome sequences [104, 105]. This would mean that Candidatus species (with high-quality genome sequences) could be used as type material and would give them nomenclatural priority (Box 3). Arguments against the use of genome sequences as type material include the lack of deposited physical biomass, lack of uniformly applied genome quality standards, the absence of directly measured phenotypic traits and the potential for nomenclatural chaos due to the much reduced requirements for naming an organism [106, 107]. Given the difficulties in incorporating nomenclature of uncultured microorganisms into the Prokaryotic Code, there have been calls to establish an independent code for these taxa [45, 108]. Proposed minimal standards include genome sequence quality (estimated completeness and contamination), ecological data, a complete 16S rRNA gene sequence, inferred metabolic functions and microscopic identification of the organism using taxon-specific FISH probes or related technique [108]. A key goal of establishing such a parallel code would be that it ultimately converge with the Prokaryotic Code to ensure a unified nomenclature for prokaryotes [45, 108]. A proposal to use sequence data as type material was rejected by the International Committee on Systematics of Prokaryotes (the committee which governs the Prokaryotic Code) in March 2020 [109]. However, if uncultured taxa are ever to be fully integrated into the Prokaryotic Code, sequence data (ideally genome sequences) will have to be accepted as type material, and if this is not possible, a separate nomenclatural code will likely emerge that accepts genomes as type material or does not use type material at all.

Nomenclatural scaling issues

A recent estimate of the global number of prokaryotic species is 2.2–4.3 million [110], down from previous potentially flawed estimates of trillions [111]. Even with this downwardly revised estimate, there is an enormous gap between millions of species and the current number of species with validly published names (~21K) and genomically described species (~25K) [9, 112]. We are likely to bridge this gap over the coming decades in terms of genome representation, but validation of names of such a large volume of new species via the Prokaryotic Code is not currently possible for uncultured taxa and is time-consuming for microbial isolates (Box 3). This is already being reflected in the high proportion of prokaryotic taxa with placeholder names (Fig. 2). However, it can be reasonably argued that not all identified species need to be given Latin names provided that a systematic taxonomic framework with unique and permanent object identifiers for genomically circumscribed species is established and maintained [1, 44]. Only species that are of sufficient interest to the scientific community would be the subject of more in-depth characterisation and naming. Alternatively, Pallen et al. recently demonstrated the high-throughput generation of grammatically correct Latin names is quite feasible using a combinatorial approach, suggesting that millions of taxa could be named [113]. However, adapting the existing Code or proposing a separate nomenclature for taxa that have not or cannot be obtained in pure culture would still be required.

Bones of contention between prokaryotic nomenclature and microbial ecology

Microbial ecologists have always appreciated the need to name the microorganisms that they study, however, most are not overly familiar with the rules of nomenclature. This has resulted in a number of points of contention between the two disciplines, which could expand once uncultured taxa are more formally taken into consideration under the Prokaryotic Code or under a new code. First, the Code requires strict adherence to correct Latin grammar, and names are routinely checked for etymological correctness by a small group of experts before publication in the International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology (IJSEM) as original articles or in Validation Lists [76]. Candidatus names, by contrast, are not held to these exacting standards as evidenced by a recent compilation in IJSEM, where 35% of 1091 compiled Candidatus names required grammatical corrections [100]. Second, since the 1975 revision of the Prokaryotic Code, there is a requirement that higher rank names up to class be formed from the stem of a genus name and a standardised suffix (Rules 8 and 9; [76]). There has been a recent proposal to extend this requirement to the rank of phylum using the suffix -ota, which necessitates small variations to numerous existing phylum names, such as Planctomycetes to Planctomycetota and Thermotogae to Thermotogota (Table 1 in [114]). Moreover, the requirement to form higher rank names on subordinate genus stems has resulted in proposals to completely change the names of a number of higher taxa, although there is latitude in the Code to retain older names predating this requirement. For example, it was proposed that the Class Epsilonproteobacteria be renamed to Campylobacteria after the genus Campylobacter [115]. Such changes can create unrest amongst microbial ecologists who value continuity of names in the literature ahead of strict compliance with the Prokaryotic Code. Despite these potential shortcomings (from the ecological viewpoint), the great majority of validated higher taxon names satisfy the genus stem requirement with a few well-established and high-profile exceptions such as the proteobacterial classes and class Actinobacteria [114]. However, if the rank of phylum and Candidatus taxa are formally recognized, the number of discrepancies and associated name changes will increase.

A crossroads for prokaryotic taxonomy and nomenclature

Prokaryotic taxonomy and nomenclature are at an interesting crossroads. On the positive side, we have never been better placed to develop a taxonomy based on objective evolutionary relationships using the burgeoning resource of sequenced microbial genomes [108, 116]. Microbial taxonomies have evolved over time in response to improved methodologies (Fig. 1), and it has been argued that for this reason, an official taxonomy should be avoided to prevent the possibility of it becoming methodologically outdated [1]. However, genomes are the most fundamental blueprints of life making it unlikely that a widely accepted alternative methodology resulting in a radically different and improved taxonomy will be developed. Although there are bioinformatic scaling challenges associated with developing a comprehensive genome-based taxonomy, the high degree of concordance between independent initiatives using different combinations of marker genes bodes well for a robust evolutionary framework [57, 117] that could form the basis of a stable taxonomy.

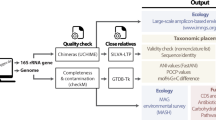

While the idea of a polyphasic approach to taxonomy is understandable, particularly the goal of using multiple features to define ecologically coherent units [118], we believe that genome sequences alone, specifically the subset of conserved vertically inherited core operating genes, should form the basis of a taxonomic framework. All other phenotypic, genotypic and ecological data can then be usefully overlaid onto this framework in order to understand their individual distributions and evolutionary trajectories relative to the species tree. The benefits of a single consistent taxonomy universally accepted by the scientific community would be manifold, including improved interoperability and communication. This was the impetus for developing the GTDB [44] (Table 1), which has a heavy emphasis on inclusion (i.e., using as much high-quality sequence data as possible from both cultured and uncultured taxa) and systematisation (e.g., uniform and reproducible approaches for defining species representatives and ranks, and provision of full taxonomic assignments from domain to species [9, 44]).

A standardised taxonomic framework needs a nomenclature that is similarly reproducible and objective and will scale with the task at hand. The official prokaryotic nomenclature was developed before the advent of large-scale genome sequencing and characterisation of uncultured taxa, and consequently does not cover the uncultured microbial majority. This impasse will need to be overcome either by development of a separate nomenclature based on genome sequences as type material, or a significant modification of the rules governing Candidatus taxa in the Prokaryotic Code [45, 105, 108]. If development of a separate nomenclature does become necessary, it could provide an opportunity to take the best elements of the Prokaryotic Code and streamline other parts mired in historical legacy that are not user friendly [1, 119], and do not scale well to the challenge of big sequence data. One example would be simplification or automated formation of names derived from Latin or Greek with correct etymology, which otherwise only a handful of practitioners worldwide are capable of ensuring [120].

On the negative side, adoption of a universal standardised taxonomy will inevitably be accompanied by growing pains. Several industries have become invested in particular taxonomies and associated nomenclature, which do not necessarily follow an evolutionary framework. For example the well-known bacterial genus Shigella is phylogenetically intertwined with Escherichia and should be made a synonym based on an evolutionary taxonomy; however, it is maintained as a separate genus to avoid confusion in clinical practice [121]. Similarly, the genus Lactobacillus has a high profile in the probiotic sector with many species being familiar to a general audience including L. acidophilus and L. casei. From a phylogenetic perspective, however, the genus is too deep and also polyphyletic. A recent genome-based revision of the taxonomy of Lactobacillus divided it into 24 distinct genera [117], which was accompanied by an outreach campaign to educate probiotic consumers endorsed by the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics. Development of an additional nomenclature while presenting an opportunity for modernisation does carry with it the potential negative of interoperability challenges with the existing Prokaryotic Code. However, this is not unprecedented as exemplified by the case of Cyanobacteria (Box 2), and therefore should be manageable with an open dialogue between nomenclatural committees. With careful management and adequate resourcing, a genome-based taxonomy and streamlined nomenclature would be welcomed by a new generation of researchers who use modern approaches to study the microbial world.

References

Rosselló-Móra R, Whitman WB. Dialogue on the nomenclature and classification of prokaryotes. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2019;42:5–14.

Larson JL. Linnaeus and the natural method. Isis. 1967;58:304–20.

Rosselló-Móra R, Amann R. Past and future species definitions for Bacteria and Archaea. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2015;38:209–16.

Thewissen JGM, Cooper LN, Clementz MT, Bajpai S, Tiwari BN. Whales originated from aquatic artiodactyls in the Eocene epoch of India. Nature. 2007;450:1190–4.

Oren A, Garrity GM. Then and now: a systematic review of the systematics of prokaryotes in the last 80 years. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 2014;106:43–56.

Woese CR. There must be a prokaryote somewhere: microbiology’s search for itself. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:1–9.

Rappé MS, Giovannoni SJ. The uncultured microbial majority. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2003;57:369–94.

Rinke C, Schwientek P, Sczyrba A, Ivanova NN, Anderson IJ, Cheng J-F, et al. Insights into the phylogeny and coding potential of microbial dark matter. Nature. 2013;499:431–7.

Parks DH, Chuvochina M, Chaumeil P-A, Rinke C, Mussig AJ, Hugenholtz P. A complete domain-to-species taxonomy for Bacteria and Archaea. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38:1079–86.

Vandamme P, Pot B, Gillis M, De Vos P, Kersters K, Swings J. Polyphasic taxonomy, a consensus approach to bacterial systematics. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:407–38.

Yarza P, Yilmaz P, Pruesse E, Glöckner FO, Ludwig W, Schleifer K-H, et al. Uniting the classification of cultured and uncultured bacteria and archaea using 16S rRNA gene sequences. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:635–45.

Mayr E. Biological classification: toward a synthesis of opposing methodologies. Science. 1981;214:510–6.

Bergey DH, Harrison FC, Breed RS, Hammer BW, Huntoon FM. Bergey’s manual of determinative bacteriology. 1st ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins Co.; 1923.

Sneath PHA, Sokal RR. Numerical taxonomy. Nature. 1962;193:855–60.

Sokal RR. Numerical taxonomy. Sci Am. 1966;215:106–17.

Sneath PHA, Sokal RR. Numerical taxonomy. The principles and practice of numerical classification. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman and Co.; 1973.

Stanier RY, van Niel CB. The main outlines of bacterial classification. J Bacteriol. 1941;42:437–66.

van Niel CB. The classification and natural relationships of bacteria. In: Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1946. p. 285–301.

Stanier RY, van Niel CB. The concept of a bacterium. Arch Mikrobiol. 1962;42:17–35.

Zuckerkandl E, Pauling L. Molecules as documents of evolutionary history. J Theor Biol. 1965;8:357–66.

Woese CR, Fox GE. Phylogenetic structure of the prokaryotic domain: the primary kingdoms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5088–90.

Lane DJ, Pace B, Olsen GJ, Stahl DA, Sogin ML, Pace NR. Rapid determination of 16S ribosomal RNA sequences for phylogenetic analyses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:6955–9.

Olsen GJ, Woese CR. Ribosomal RNA: a key to phylogeny. FASEB J. 1993;7:113–23.

Woese CR. Bacterial evolution. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:221–71.

Schildkraut CL, Marmur J, Doty P. The formation of hybrid DNA molecules and their use in studies of DNA homologies. J Mol Biol. 1961;3:595–617.

McCarthy BJ, Bolton ET. An approach to the measurement of genetic relatedness among organisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1963;50:156–64.

Marmur J, Doty P. Determination of the base composition of deoxyribonucleic acid from its thermal denaturation temperature. J Mol Biol. 1962;5:109–18.

Owen RJ, Hill LR, Lapage SP. Determination of DNA base compositions from melting profiles in dilute buffers. Biopolymers. 1969;7:503–16.

Schwartz DC, Saffran W, Welsh J, Haas R, Goldenberg M, Cantor CR. New techniques for purifying large DNAs and studying their properties and packaging. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1983;47:189–95.

Schwartz DC, Cantor CR. Separation of yeast chromosome-sized DNAs by pulsed field gradient gel electrophoresis. Cell. 1984;37:67–75.

Maiden MCJ, Bygraves JA, Feil E, Morelli G, Russell JE, Urwin R, et al. Multilocus sequence typing: A portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3140–5.

Enright MC, Spratt BG. Multilocus sequence typing. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7:482–7.

Gevers D, Cohan FM, Lawrence JG, Spratt BG, Coenye T, Feil EJ, et al. Re-evaluating prokaryotic species. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:733–9.

Thompson FL, Gevers D, Thompson CC, Dawyndt P, Naser S, Hoste B, et al. Phylogeny and molecular identification of Vibrios on the basis of multilocus sequence analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:5107–15.

Evans PN, Boyd JA, Leu AO, Woodcroft BJ, Parks DH, Hugenholtz P, et al. An evolving view of methane metabolism in the Archaea. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17:219–32.

Amann RI, Ludwig W, Schleifer KH. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:143–69.

Giovannoni SJ, Britschgi TB, Moyer CL, Field G. Genetic diversity in Sargasso Sea bacterioplankton. Nature. 1990;345:60–63.

Ronaghi M, Uhlén M, Nyrén P. A sequencing method based on real-time pyrophosphate. Science. 1998;281:363–5.

Sogin ML, Morrison HG, Huber JA, Welch DM, Huse SM, Neal PR, et al. Microbial diversity in the deep sea and the underexplored “rare biosphere”. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:12115–20.

Andersson AF, Lindberg M, Jakobsson H, Bäckhed F, Nyrén P, Engstrand L. Comparative analysis of human gut microbiota by barcoded pyrosequencing. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2836.

Garrity GM, Boone DR, Castenholtz RW. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology, vol. 2. New York: Springer-Verlay; 2001.

Kämpfer P, Glaeser SP. Prokaryotic taxonomy in the sequencing era—the polyphasic approach revisited. Env Microbiol. 2012;14:291–317.

Konstantinidis KT, Tiedje JM. Towards a genome-based taxonomy for prokaryotes. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:6258–64.

Parks DH, Chuvochina M, Waite DW, Rinke C, Skarshewski A, Chaumeil P-A, et al. A standardized bacterial taxonomy based on genome phylogeny substantially revises the tree of life. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36:996–1004.

Murray AE, Freudenstein J, Gribaldo S, Hatzenpichler R, Hugenholtz P, Kämpfer P, et al. Roadmap for naming uncultivated Archaea and Bacteria. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5:987–94.

Fox GE, Wisotzkey JD, Jurtshuk P Jr. How close Is close: 16S rRNA sequence identity may not be sufficient to guarantee species identity. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:166–70.

Ciccarelli FD, Doerks T, von Mering C, Creevey CJ, Snel B, Bork P. Toward automatic reconstruction of a highly resolved tree of life. Science. 2006;311:1283–7.

Johnson JS, Spakowicz DJ, Hong B-Y, Petersen LM, Demkowicz P, Chen L, et al. Evaluation of 16S rRNA gene sequencing for species and strain-level microbiome analysis. Nat Commun. 2019;10:5029.

Doolittle WF. Phylogenetic classification and the universal tree. Science. 1999;284:2124–8.

Ochman H, Lawrence JG, Groisman EA. Lateral gene transfer and the nature of bacterial innovation. Nature. 2000;405:299–304.

Dagan T, Artzy-Randrup Y, Martin W. Modular networks and cumulative impact of lateral transfer in prokaryote genome evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:10039–44.

Sanderson MJ, Purvis A, Henze C. Phylogenetic supertrees: assembling the trees of life. Trends Ecol Evol. 1998;13:105–9.

Daubin V, Gouy M, Perrière G. Bacterial molecular phylogeny using supertree approach. Genome Inform. 2001;12:155–64.

Bininda-Emonds ORP. The evolution of supertrees. Trends Ecol Evol. 2004;19:315–22.

Wu M, Eisen JA. A simple, fast, and accurate method of phylogenomic inference. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R151.

de Queiroz A, Gatesy J. The supermatrix approach to systematics. Trends Ecol Evol. 2007;22:34–41.

Williams TA, Cox CJ, Foster PG, Szöllősi GJ, Embley TM. Phylogenomics provides robust support for a two-domains tree of life. Nat Ecol Evol. 2020;4:138–47.

Zhu Q, Mai U, Pfeiffer W, Janssen S, Asnicar F, Sanders JG, et al. Phylogenomics of 10,575 genomes reveals evolutionary proximity between domains Bacteria and Archaea. Nat Commun. 2019;10:5477.

Konstantinidis KT, Tiedje JM. Genomic insights that advance the species definition for prokaryotes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:2567–72.

Goris J, Konstantinidis KT, Klappenbach JA, Coenye T, Vandamme P, Tiedje JM. DNA–DNA hybridization values and their relationship to whole-genome sequence similarities. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007;57:81–91.

Auch AF, von Jan M, Klenk H-P, Göker M. Digital DNA-DNA hybridization for microbial species delineation by means of genome-to-genome sequence comparison. Stand Genom Sci. 2010;2:117–34.

Meier-Kolthoff JP, Klenk H-P, Göker M. Taxonomic use of DNA G+C content and DNA–DNA hybridization in the genomic age. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2014;64:352–6.

Tyson GW, Chapman J, Hugenholtz P, Allen EE, Ram RJ, Richardson PM, et al. Community structure and metabolism through reconstruction of microbial genomes from the environment. Nature. 2004;428:37–43.

Albertsen M, Hugenholtz P, Skarshewski A, Nielsen KL, Tyson GW, Nielsen PH. Genome sequences of rare, uncultured bacteria obtained by differential coverage binning of multiple metagenomes. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:533–8.

Chen L-X, Anantharaman K, Shaiber A, Eren AM, Banfield JF. Accurate and complete genomes from metagenomes. Genome Res. 2020;30:315–33.

Raghunathan A, Ferguson HR, Bornarth CJ, Song W, Driscoll M, Lasken RS, et al. Genomic DNA amplification from a single bacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:3342–7.

Marcy Y, Ouverney C, Bik EM, Lösekann T, Ivanova N, Martin HG, et al. Dissecting biological ‘dark matter’ with single-cell genetic analysis of rare and uncultivated TM7 microbes from the human mouth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:11889–94.

Paez-Espino D, Eloe-Fadrosh EA, Pavlopoulos GA, Thomas AD, Huntemann M, Mikhailova N, et al. Uncovering earth’s virome. Nature. 2016;536:425–30.

Yutin N, Galperin MY. A genomic update on clostridial phylogeny: Gram-negative spore formers and other misplaced clostridia. Environ Microbiol. 2013;15:2631–41.

Hugenholtz P, Huber T. Chimeric 16S rDNA sequences of diverse origin are accumulating in the public databases. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2003;53:289–93.

Hugenholtz P, Stackebrandt E. Reclassification of Sphaerobacter thermophilus from the subclass Sphaerobacteridae in the phylum Actinobacteria to the class Thermomicrobia (emended description) in the phylum Chloroflexi (emended description). Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54:2049–51.

Gaston KJ, Mound LA. Taxonomy, hypothesis testing and the biodiversity crisis. Proc R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci. 1993;251:139–42.

Linnaeus C. Systema naturae, vol. 1. Holmiae: Impensis Direct. Laurentii Salvii; 1758.

Buchanan RE. Studies in the nomenclature and classification of the bacteria: II. the primary subdivisions of the Schizomycetes. J Bacteriol. 1917;2:155–64.

Buchanan RE, St. John-Brooks R, Breed RS. International bacteriological code of nomenclature. J Bacteriol. 1948;55:287–306.

Parker CT, Tindall BJ, Garrity GM. International Code of Nomenclature of Prokaryotes. Prokaryotic code (2008 revision). Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2019;69:S1–S111.

Buchanan RE. The international code of nomenclature of the bacteria and viruses. Syst Zool. 1959;8:27–39.

Sneath PHA, McGowan V, Skerman VBD. Approved lists of bacterial names. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1980;30:225–420.

Ride WD, Cogger HG, Dupuis C, Kraus O, Minelli A, Thompson FC, et al. International code of zoological nomenclature. 4th ed. London: International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature; 1999.

Turland N, Wiersema J, Barrie F, Greuter W, Hawksworth D, Herendeen P, et al. International code of nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Shenzhen Code) adopted by the nineteenth International Botanical Congress Shenzhen, China, July 2017. Regnum vegetabile. Koeltz Botanical Books: Oberreifenberg, Germany; 2018.

Van Regenmortel MHV. 1—Recent developments in the definition and official names of virus species. In: Tibayrenc M, editor. Genetics and evolution of infectious diseases. 2nd ed. London: Elsevier; 2017. p. 1–23.

Siddell SG, Walker PJ, Lefkowitz EJ, Mushegian AR, Dutilh BE, Harrach B, et al. Binomial nomenclature for virus species: a consultation. Arch Virol. 2020;165:519–25.

Greuter W, Hawksworth DL, McNeill J, Mayo MA, Minelli A, Sneath PHA, et al. Draft BioCode: the prospective international rules for the scientific names of organisms. Taxon. 1996;45:349–72.

Greuter W. On a new BioCode, harmony, and expediency. Taxon. 1996;45:291–4.

Greuter W, Nicolson DH. Introductory comments on the Draft BioCode, from a botanical point of view. Taxon. 1996;45:343–8.

Brummitt RK. The BioCode is unnecessary and unwanted. Syst Bot. 1997;22:182–6.

Dubois A. A zoologist’s viewpoint on the Draft BioCode. Bionomina. 2011;3:45–62.

Greuter W, Garrity G, Hawksworth DL, Jahn R, Kirk PM, Knapp S, et al. Draft BioCode (2011): principles and rules regulating the naming of organisms. Taxon. 2011;60:201–12.

Cantino DP, Bryant HN, de Queiroz K, Donoghue MJ, Eriksson T, Hillis DM, et al. Species names in phylogenetic nomenclature. Syst Biol. 1999;48:790–807.

Cantino PD, de Queiroz K. PhyloCode: a phylogenetic code of biological nomenclature. 2000.

de Queiroz K. The PhyloCode and the distinction between taxonomy and nomenclature. Syst Biol. 2006;55:160–2.

de Queiroz K, Cantino PD. International code of phylogenetic nomenclature (PhyloCode): a phylogenetic code of biological nomenclature. 1st ed. Ohio: CRC Press; 2020.

Felsenstein J. Inferring phylogenies, vol. 2. Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer associates; 2004.

Gordon DA, Giovannoni SJ. Detection of stratified microbial populations related to Chlorobium and Fibrobacter species in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1171–7.

Ley RE, Harris JK, Wilcox J, Spear JR, Miller SR, Bebout BM, et al. Unexpected diversity and complexity of the Guerrero Negro hypersaline microbial mat. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:3685–95.

Wrighton KC, Thomas BC, Sharon I, Miller CS, Castelle CJ, VerBerkmoes NC, et al. Fermentation, hydrogen, and sulfur metabolism in multiple uncultivated bacterial phyla. Science. 2012;337:1661–5.

Murray RGE, Stackebrandt E. Taxonomic note: implementation of the provisional status Candidatus for incompletely described procaryotes. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:186–7.

Murray RGE, Schleifer KH. Taxonomic notes: a proposal for recording the properties of putative taxa of procaryotes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1994;44:174–6.

Oren A. A plea for linguistic accuracy—also for Candidatus taxa. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2017;67:1085–94.

Oren A, Garrity GM, Parker CT, Chuvochina M, Trujillo ME. Lists of names of prokaryotic Candidatus taxa. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2020;70:3956–4042.

DeLong EF, Wickham GS, Pace NR. Phylogenetic stains: ribosomal RNA-based probes for the identification of single cells. Science. 1989;243:1360–3.

Parks DH, Rinke C, Chuvochina M, Chaumeil P-A, Woodcroft BJ, Evans PN, et al. Recovery of nearly 8,000 metagenome-assembled genomes substantially expands the tree of life. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2:1533–42.

Hatzenpichler R, Krukenberg V, Spietz RL, Jay ZJ. Next-generation physiology approaches to study microbiome function at single cell level. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2020;18:241–56.

Whitman WB. Genome sequences as the type material for taxonomic descriptions of prokaryotes. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2015;38:217–22.

Whitman WB. Modest proposals to expand the type material for naming of prokaryotes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2016;66:2108–12.

Bisgaard M, Christensen H, Clermont D, Dijkshoorn L, Janda JM, Moore ERB, et al. The use of genomic DNA sequences as type material for valid publication of bacterial species names will have severe implications for clinical microbiology and related disciplines. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;95:102–3.

Overmann J, Huang S, Nübel U, Hahnke RL, Tindall BJ. Relevance of phenotypic information for the taxonomy of not-yet-cultured microorganisms. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2019;42:22–9.

Konstantinidis KT, Rosselló-Móra R, Amann R. Uncultivated microbes in need of their own taxonomy. ISME J. 2017;11:2399–406.

Sutcliffe IC, Dijkshoorn L, Whitman WB, ICSP Executive Board. Minutes of the International Committee on Systematics of Prokaryotes online discussion on the proposed use of gene sequences as type for naming of prokaryotes, and outcome of vote. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2020;70:4416–7.

Louca S, Mazel F, Doebeli M, Parfrey LW. A census-based estimate of Earth’s bacterial and archaeal diversity. PLOS Biol. 2019;17:e3000106.

Locey KJ, Lennon JT. Scaling laws predict global microbial diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:5970–5.

Parte AC. LPSN—list of prokaryotic names with standing in nomenclature (bacterio.net), 20 years on. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2018;68:1825–9.

Pallen MJ, Telatin A, Oren A. The next million names for Archaea and Bacteria. Trends in Microbiol. 2021;29:289–98.

Whitman WB, Oren A, Chuvochina M, da Costa MS, Garrity GM, Rainey FA, et al. Proposal of the suffix –ota to denote phyla. Addendum to ‘Proposal to include the rank of phylum in the International Code of Nomenclature of Prokaryotes’. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2018;68:967–9.

Waite DW, Vanwonterghem I, Rinke C, Parks DH, Zhang Y, Takai K, et al. Comparative genomic analysis of the class Epsilonproteobacteria and proposed reclassification to Epsilonbacteraeota (phyl. nov.). Front Microbiol. 2017;8:682.

Hugenholtz P, Skarshewski A, Parks DH. Genome-based microbial taxonomy coming of age. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2016;8:a018085.

Zheng J, Wittouck S, Salvetti E, Franz CMAP, Harris HMB, Mattarelli P, et al. A taxonomic note on the genus Lactobacillus: Description of 23 novel genera, emended description of the genus Lactobacillus Beijerinck 1901, and union of Lactobacillaceae and Leuconostocaceae. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2020;70:2782–858.

Garcia-Pichel F, Zehr JP, Bhattacharya D, Pakrasi HB. What’s in a name? The case of cyanobacteria. J Phycol. 2020;56:1–5.

Pridham TG. Nomenclature of bacteria with special reference to the order Actinomycetales. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1971;21:197–206.

Oren A, Schink B, Garrity GM. Wanted: microbiologists with basic knowledge of Latin and Greek to join our ‘nomenclature quality control’ team. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2015;65:3761–2.

Lan R, Reeves PR. Escherichia coli in disguise: molecular origins of Shigella. Microbes Infect. 2002;4:1125–32.

Oren A, da Costa MS, Garrity GM, Rainey FA, Rosselló-Móra R, Schink B, et al. Proposal to include the rank of phylum in the International Code of Nomenclature of Prokaryotes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2015;65:4284–7.

Olsen GJ, Overbeek R, Larsen N, Marsh TL, McCaughey MJ, Maciukenas MA, et al. The Ribosomal Database Project. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:2199–200.

Cole JR, Wang Q, Fish JA, Chai B, McGarrell DM, Sun Y, et al. Ribosomal Database Project: data and tools for high throughput rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D633–42.

Yilmaz P, Parfrey LW, Yarza P, Gerken J, Pruesse E, Quast C, et al. The SILVA and “All-species Living Tree Project (LTP)” taxonomic frameworks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;42:D643–8.

Pruesse E, Quast C, Knittel K, Fuchs BM, Ludwig W, Peplies J, et al. SILVA: a comprehensive online resource for quality checked and aligned ribosomal RNA sequence data compatible with ARB. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:7188–96.

Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, Gerken J, Schweer T, Yarza P, et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D590–6.

Yoon S-H, Ha S-M, Kwon S, Lim J, Kim Y, Seo H, et al. Introducing EzBioCloud: a taxonomically united database of 16S rRNA gene sequences and whole-genome assemblies. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2017;67:1613–7.

McDonald D, Price MN, Goodrich J, Nawrocki EP, DeSantis TZ, Probst A, et al. An improved Greengenes taxonomy with explicit ranks for ecological and evolutionary analyses of bacteria and archaea. ISME J. 2012;6:610–8.

DeSantis TZ, Hugenholtz P, Larsen N, Rojas M, Brodie EL, Keller K, et al. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:5069–72.

McIlroy SJ, Saunders AM, Albertsen M, Nierychlo M, McIlroy B, Hansen AA, et al. MiDAS: the field guide to the microbes of activated sludge. Database. 2015;2015:bav062.

McIlroy SJ, Kirkegaard RH, McIlroy B, Nierychlo M, Kristensen JM, Karst SM, et al. MiDAS 2.0: an ecosystem-specific taxonomy and online database for the organisms of wastewater treatment systems expanded for anaerobic digester groups. Database. 2017;2017:bax016.

Federhen S. The NCBI taxonomy database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D136–43.

Meier-Kolthoff JP, Göker M. TYGS is an automated high-throughput platform for state-of-the-art genome-based taxonomy. Nat Commun. 2019;10:2182.

Markowitz VM, Korzeniewski F, Palaniappan K, Szeto E, Werner G, Padki A, et al. The integrated microbial genomes (IMG) system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D344–8.

Chen I-MA, Chu K, Palaniappan K, Pillay M, Ratner A, Huang J, et al. IMG/M v.5.0: an integrated data management and comparative analysis system for microbial genomes and microbiomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;47:D666–77.

Euzéby JP. List of bacterial names with standing in nomenclature: a folder available on the internet. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1997;47:590–2.

Parte AC, Sardá Carbasse J, Meier-Kolthoff JP, Reimer LC, Göker M. List of prokaryotic names with standing in nomenclature (LPSN) moves to the DSMZ. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2020;70:5607–12.

Garrity GM, Lyons C. Future-proofing biological nomenclature. Omi A J Integr Biol. 2003;7:31–3.

Ramos V, Morais J, Vasconcelos VM. A curated database of cyanobacterial strains relevant for modern taxonomy and phylogenetic studies. Sci Data. 2017;4:170054.

Komarek J, Hauer T. CyanoDB. cz-On-line database of cyanobacterial genera. Word-wide Electronic Publication University of South Bohemia Institute of Botany AS CR. 2011.

Guiry MD, Guiry GM, Morrison L, Rindi F, Miranda SV, Mathieson AC, et al. AlgaeBase: an on-line resource for Algae. Cryptogam Algol. 2014;35:105–15.

Verslyppe B, De Smet W, De Baets B, De Vos P, Dawyndt P. StrainInfo introduces electronic passports for microorganisms. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2014;37:42–50.

Rosselló-Mora R, Amann R. The species concept for prokaryotes. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2001;25:39–67.

Konstantinidis KT, Ramette A, Tiedje JM. The bacterial species definition in the genomic era. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2006;361:1929–40.

Cohan FM. What are bacterial species? Annu Rev Microbiol. 2002;56:457–87.

Achtman M, Wagner M. Microbial diversity and the genetic nature of microbial species. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:431–40.

Brenner DJ. Deoxyribonucleic acid reassociation in the taxonomy of enteric bacteria. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1973;23:298–307.

Wayne LG, Brenner DJ, Colwell RR, Grimont PAD, Kandler O, Krichevsky MI, et al. Report of the ad hoc committee on reconciliation of approaches to bacterial systematics. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1987;37:463–4.

Stackebrandt E, Goebel BM. Taxonomic note: a place for DNA-DNA reassociation and 16S rRNA sequence analysis in the present species definition in bacteriology. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1994;44:846–9.

Jain C, Rodriguez-R LM, Phillippy AM, Konstantinidis KT, Aluru S. High throughput ANI analysis of 90K prokaryotic genomes reveals clear species boundaries. Nat Commun. 2018;9:5114.

Olm MR, Crits-Christoph A, Diamond S, Lavy A, Matheus Carnevali PB, Banfield JF. Consistent metagenome-derived metrics verify and delineate bacterial species boundaries. mSystems. 2020;5:e00731–19.

Mayr E. Systematics and the origin of species from the viewpoint of a zoologist. New York: Columbia University Press; 1942.

Bobay L-M, Ochman H. Biological species are universal across life’s domains. Genome Biol Evol. 2017;9:491–501.

Aharon O, Ventura S. The current status of cyanobacterial nomenclature under the “prokaryotic” and the “botanical” code. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 2017;110:1257–69.

Bonen L, Doolittle WF. Partial sequences of 16S rRNA and the phylogeny of blue-green algae and chloroplasts. Nature. 1976;261:669–73.

Fox GE, Stackebrandt E, Hespell RB, Gibson J, Maniloff J, Dyer TA, et al. The phylogeny of prokaryotes. Science. 1980;209:457–63.

Stanier RY, Sistrom WR, Hansen TA, Whitton BA, Castenholtz RW, Pfennig N, et al. Proposal to place the nomenclature of the cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) under the rules of the International Code of Nomenclature of Bacteria. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1978;28:335–6.

Ishida T, Watanabe MM, Sugiyama J, Yokota A. Evidence for polyphyletic origin of the members of the orders of Oscillatoriales and Pleurocapsales as determined by 16S rDNA analysis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2001;201:79–82.

Bauersachs T, Miller SR, Gugger M, Mudimu O, Friedl T, Schwark L. Heterocyte glycolipids indicate polyphyly of stigonematalean cyanobacteria. Phytochemistry. 2019;166:112059.

Soo RM, Skennerton CT, Sekiguchi Y, Imelfort M, Paech SJ, Dennis PG, et al. An expanded genomic representation of the phylum Cyanobacteria. Genome Biol Evol. 2014;6:1031–45.

Soo RM, Hemp J, Parks DH, Fischer WW, Hugenholtz P. On the origins of oxygenic photosynthesis and aerobic respiration in Cyanobacteria. Science. 2017;355:1436–40.

Soo RM, Hemp J, Hugenholtz P. Evolution of photosynthesis and aerobic respiration in the cyanobacteria. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;140:200–5.

Nicolson DH. A history of botanical nomenclature. Ann Mo Bot Gard. 1991;78:33–56.

Tindall BJ, Kämpfer P, Euzéby JP, Oren A. Valid publication of names of prokaryotes according to the rules of nomenclature: past history and current practice. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2006;56:2715–20.

Acknowledgements

We thank the GTDB team, Pierre-Alain Chaumeil, Christian Rinke, Aaron Mussig, David Waite and Soo Jen Low for embarking with us down the taxonomic rabbit hole, only to discover a deeper, twistier hole called nomenclature. Hopefully this review will help others to avoid some of our initial mistakes. We thank two anonymous reviewers and in particular the Reviews Editor, Andy Holmes, for constructive feedback on the manuscript. PH, MC and DHP were supported by an Australian Research Council (ARC) Laureate Fellowship (Grant no. FL150100038) and RMS was supported by an ARC Discovery Early Career Research Award (Grant no. DE190100008). We also thank the International Society for Microbial Ecology for an Open Access Publication Voucher 2020 awarded to RMS for her talk on this review topic at the Virtual Microbial Ecology Summit Unity in Diversity.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PH and RMS wrote the first draft of the paper and DHP drafted Fig. 2. All authors revised and approved the article.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hugenholtz, P., Chuvochina, M., Oren, A. et al. Prokaryotic taxonomy and nomenclature in the age of big sequence data. ISME J 15, 1879–1892 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-021-00941-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-021-00941-x

This article is cited by

-

Two decades of population genomics: will we ever agree on bacterial species?

BMC Biology (2024)

-

An evolutionary view of the Fusarium core genome

BMC Genomics (2024)

-

The intestinal digesta microbiota of tropical marine fish is largely uncultured and distinct from surrounding water microbiota

npj Biofilms and Microbiomes (2024)

-

The overlooked evolutionary dynamics of 16S rRNA revises its role as the “gold standard” for bacterial species identification

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

The discovery of archaea: from observed anomaly to consequential restructuring of the phylogenetic tree

History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences (2024)