Abstract

This work aims to identify and quantify the biases behind the anomalous behavior of people when they deal with the Three Doors dilemma, which is a really simple but counterintuitive game. Carrying out an artefactual field experiment and proposing eight different treatments to isolate the anomalies, we provide new interesting experimental evidence on the reasons why subjects fail to take the optimal decision. According to the experimental results, we are able to quantify the size and the impact of three main biases that explain the anomalous behavior of participants: Bayesian updating, illusion of control and status quo bias.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction and Literature Review

“Suppose you're on a game show, and you're given the choice of three doors: behind one door is a car; behind the others, goats. You pick a door, say No. 1, and the host, who knows what's behind the doors, opens another door, say No. 3, which has a goat. He then says to you, ‘Do you want to pick door No. 2?’ Is it to your advantage to switch your choice?”Footnote 1 The optimal choice, switching to pick door No. 2, should be not so hard to find (for the homo oeconomicus). People, however, seem to do not behave accordingly. This is the case of the famous TV show "Let's Make a Deal", in which a presenter (Monty) and a participant play a game called the "Monty Hall's three doors". It is a really simple but counterintuitive game, in which there are three ordered doors. Behind these three doors, there are, respectively: one prize (a luxury car) and two non-prizes (goats). The participant is supposed to find the prize (a luxury car) that is hidden behind one of the three doors. It is a two-stage sequential game as follows:

-

(1)

The participant chooses one of the three doors, and the door is left closed;

-

(2)

The host opens one of the two left doors with a goat behind;

-

(3)

The host asks the participant to decide whether to keep his initial door or to change it with the other closed door.

At this point, the intuitive thought of the participant could be that it is indifferent whether to keep staying or switch. However, following the Bayesian probability theorem we know that this intuition is wrong, and the optimal choice should be to switch. If one keeps his initial door, the probability of winning remains 1/3, as it was in point (1), while in case of switching the probability rises to 2/3. Despite it seems quite straightforward, most people seem to do not consider this conditional probability but makes often the wrong choice.

The Monty Hall problem has been deeply studied across several fields, from mathematics, psychology, physics to economics. Even though it seems a simple probabilistic game, it is hard to explain the systematic and self-determined irrational behavior of the major of participants. The debate is still open, and it seems to be an endless problem. The choice of not switching, reducing dramatically the probability of winning, could be caused by different reasons. Friedman (1998) focuses his reasoning on four main factors: (i) gambler’s fallacy, (ii) endowment effect, (iii) probability matching, (iv) Bayesian updating.

Through gambler’s fallacy (also called “illusion of control” by Camerer, 1995) participants are self-convinced to be able to control more than they really can, showing some intuitive skills in choosing the most likely door with the prize behind. Moreover, a kind of endowment effect bias can be found in explaining the anomalous choice. Since a participant already chooses one of the three doors, when he is supposed to decide whether to switch or to stick, he would not switch because he considers his initial choice as the endowment, without considering it as a sunk decision.Footnote 2 It seems that people ascribe more value to things merely because they already own them. Another important behavior that comes out from the experimental design of Friedman (1998) is the probability matching behavior, that is an anomalous and irrational behavior through which people choose according to the likelihood of each alternative rather than the real most likely one. Despite all these three already mentioned reasons are very relevant in explaining the reluctance to switch the choice, even though it should be the most rational one, there is another fundamental problem in the Monty Hall dilemma, which is considered to be the most important by the literature in various fields: participants fail in Bayesian updating. When the initial choice is made and the information of the empty door is given to the participant, the Bayesian probability of winning is 1/3 for the initially picked door and of 2/3 for the other alternative. People seem to do not notice this updating of probability, or they are not able to understand this simple but counterintuitive problem.

On this wise, Franco-Watkins et al., (2003) state that human reasoning does not always adhere to the formal rules of logic. For instance, the expected utility or Bayesian theorem fails to be effective in reality. Baratgin (2015) noticed that people often use subjective Bayesian reasoning for solving complex problems in which different solutions can be envisaged depending on the interpretations made by participants.Footnote 3 Hence, one may think that the Monty Hall anomaly is all about a problem of the misunderstanding of Bayesian probabilities or subjective conditional probabilities. In reality, it may be not the case, or better, it is not the unique cause that leads to the anomalous behavior of participants. For this purpose, experimental studies have tried to modify the original Monty hall game proposing several treatments, trying to capture different effects according to specific control variables.

Many experiments attempted to address this unsolved dilemma. By employing an iterated version of the game, Palacious-Huerta (2003) showed that different monetary incentive amount, individuals’ initial abilities and social interactions affect the learning individual and group behavior in Monty Hall problem. They found that, in earlier stages, the more able students make the optimal choice (on average with a switching rates of 18 percentage points in the first 5 rounds) respect to the less able students. Moreover, individual interaction along rounds incremented the probability to take the right choice. On the other hand, Franco-Watkins et al. (2003) ran three different experiments to study—in the first two cases—if choice behavior and probability judgements can be influenced by learning from another simulated game similar to the Monty Hall problem (a card game) and—in the last one—if changes in the number of doors and in the amount of prizes can influence participants behavior. In the first two treatments, they found that participants learned the switching strategy in the card game, and some applied it to the Monty Hall dilemma, perhaps they were are not able to soundly motivate their strategy. Thus, they get just implicit knowledge of the game, indeed they did not understand that switching is the theoretical optimal solution to increase the likelihood to win. From the last treatment, authors found that subjects portioned their probability judgement on the basis of the number of prizes over the number of unopened doors. Continuing, Morone and Fiore (2008) tested whether the Bayesian updating bias disappeared with a treatment “for dummies” in which participants were not supposed to compute any probability updating. However, although the share of switching behavior has increased, the irrational behavior of not switching did not completely disappear. Thus, the Monty Hall anomaly is not only linked to the limited capacity of Bayesian updating but other reasons, mainly psychological, play an important role in the choice of participants. According to Morone and Fiore (2008), the “status quo bias” could have an effective impact on the anomalous behavior of players. People seem to attribute a higher value on the initial choice, probably because they feel their choice as an initial endowment, and their loss aversion makes them surer in case they do not switch the initial choice. Participants give more value to their choice, only because they think they own them, and this justifies the fact that at least 15% of the experiment participants never decided to switch. Finally, Petrocelli and Harris (2011) studied the linkage between learning, counterfactual thinking, and memory for decision/outcome frequencies. Their main result is that subjects are reluctant to switch doors. The counterfactual thinkingFootnote 4 makes learning Monty Hall problem more difficult, because it puts subjects in the position to do not understand the optimal choice, especially when the premium increases. At the same time memory for decision/outcome frequencies makes learning the actual associations between switch decisions and winning and stick decisions and losing, difficult to understand.

To the best of our knowledge, literature lacks paper which (i) jointly remove both the Bayesian updating and the illusion of control biases and (ii) account for a different game solution.

We provide an artefactual field experiment, carried out in a mall in Bari (Italy), to isolate the different reasons behind the irrational choice of participants.

2 Experimental design

We conducted an artefactual field experiment in a mall in Bari (Italy) in October 2019, interviewing a total amount of N = 681 subjects.Footnote 5

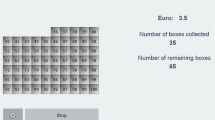

In the questionnaire (see Annex 1), we have six socio-demographic questions. The last question concerns Monty Hall’s three doors. In all eight treatments we have three boxes and only one of these contains a prize, i.e. a 10 € banknote the other two boxes are empty.

In T1, the Control treatment, subjects were asked to choose a box among three and an empty un-chosen box was subsequent opened. Then, we asked subjects if they want to switch their first choice with the remaining un-chosen box. In this treatment are presented the three biases discussed in the previous paragraph:

-

the illusion of control: subjects believe that they may understand which choice is better and they consider the first choice as the most likely;

-

the status quo bias/endowment effect: subjects seem to give higher value on their first choice, maybe because they are loss averse and because they think they own it;

-

the Bayesian updating: the opening of the empty box creates new information i.e. the probability that the first chosen box contained a reward was 1/3 and it was stead, at the same time the probability that the open box concealed the reward became 0. Finally, the probability that the last box had a reward was 1/3 and it became 2/3.

T2 is identical to T1 but we removed the Bayesian updating. Also, in this treatment, subjects were asked to choose a box among three, but in this treatment, no boxes are opened after the subject choice and, then we asked subjects if they want to switch their chosen box with the other two boxes. In this treatment are presented only two of biases discussed in the previous paragraph:

-

the illusion of control;

-

the status quo bias/endowment effect.

In T3, subjects were assigned one box among three and then one empty box is opened, and we asked subjects if they want to switch their assigned box with the remaining not opened one. In this treatment, only two biases are presented:

-

the Bayesian updating;

-

the status quo bias/endowment effect.

T4 is identical to T3 but we removed the Bayesian updating. Subjects were assigned one box among three and then we asked them if they want to switch their assigned box with the two remaining boxes. In this treatment, there is only one bias:

-

the status quo bias/endowment effect.

In T5, subjects were asked to choose two boxes among three. Then, an empty box of the two chosen boxes is opened and we asked subjects if they want to switch both their chosen boxes with the remaining box. In this treatment, there are all biases:

-

the illusion of control;

-

the Bayesian updating;

-

the status quo bias/endowment effect.

In T6, subjects were asked to choose two among three boxes. We asked subjects if they want to switch both their chosen boxes with the remaining box. In this treatment, there are only two biases:

-

the illusion of control;

-

the status quo bias/endowment effect.

In T7, subjects were assigned two boxes. Then, an empty box of the two assigned ones is opened and we asked subjects if they want to switch both their assigned boxes with the remaining box. In this treatment, there are only two biases:

-

the Bayesian updating

-

the status quo bias/endowment effect.

Finally, in T8, subjects were assigned two among three boxes. Then, subjects were asked if they want to switch both their boxes with the remaining box. This treatment presents only one bias:

-

the status quo bias/endowment effect.

In Table 1, we summarize the biases that are present in each treatment:

3 Experimental results

We start the analysis by exposing an overview of the results (Fig. 1) and, for the sake of soundness, we compare the baseline scenario with those of previous literature (Table 2). Fig. 1 shows the share of subjects who made the optimal decision in each treatment.

As it can be observed, there are interesting differences across all the eight treatments. To grasp the size and the effect of removing each one of the three biases which could explain the irrational choice of subjects, it is useful to analyze the difference between performances comparing paired treatments. Moreover, to get clearer information from the data, it would be better to group the treatments into two categories, each according to the same optimal strategy for the treatments inside the group. For this reason, we compare the results within the first four treatments grouped (T1, T2, T3, and T4), in which the rational choice is to switch and the biases go in the opposite direction of the rational choice, and within the last four treatments grouped as well (T5, T6, T7, and T8). As a general result, comparing the results between both groups, one can see graphically that there exists a big gap between the performance of the first group and second group. This is because in the first four treatments subjects can maximize their probability of winning if they switch but the biases go in the opposite direction pushing then to stay; hence, it is harder for subjects to being right respect to the second group of treatments. In the latter, in fact, the decision that maximizes their probability of winning goes in the same direction of the biases.

Starting from T1, the control treatment in which all three biases are present, the share of subjects who took the optimal choice is 10%. This means that 90% of subjects behaved irrationally. It is interesting to compare this result with the results in previous literature. To this purpose, in Table 2, we show the percentage of subjects who decided to switch in the first period across several experiments, when the original Monty Hall’s treatment has been proposed to participants.Footnote 6

We additionally provide a two proportion Z-test to compare the statistical significance of the differences evidenced (see Table 3).

Moving from T1 to T2, we observe an increase of 17.78% (p-value = 0.034) of the percentage of the optimal choice. Hence, we observe an increase of rationality once the Bayesian updating is removed. This positive effect appears also when we take away the illusion of control. Comparing the results between T3 and T1, in fact, the 35.23% of subjects took the optimal decision, respect to the 10% in the control treatment T1. The difference of 25.23% (p-value 0.001) is caused by illusion of control.

Another important aspect that we aim to understand is the impact of eliminating both Bayesian updating and illusion of control together. This effect is captured taking the difference between the means of T4 and T1, which is 25.44% (p-value 0.0001). Hence, removing Bayesian updating and illusion of control together positively and significantly improves the performance of subjects. Since in T2 we isolate Bayesian updating, in T3, the illusion of control bias, and in T4, both these biases together, it can be interesting to see whether the effect of removing Bayesian updating (T2) and illusion of control (T3) one by one is equal or not to the effect of removing both together (T4). To test this difference, we create a third variable made by the sum of T2 and T3, and then we compare the mean of this new cumulative variable with the performance of T4. We reject the null hypothesis (p-value 0.0008), concluding that the Bayesian updating and illusion of control are not cumulative biases. Even though we expected a larger share of rational choices in T4 than T3 and T2, the ratio of subjects taking the optimal choice in T4 was not statistically different from the other two treatments, suggesting that a significant share of subjects may be affected by more biases. In particular, the observed frequency of rational choices in T4 is lower than expected, and this indirectly confirms that subjects are affected by more than a bias only. Hence, we can argue that there could be an overlapping of biases, in this case, the Bayesian updating and illusion of control. It is important to notice that in T4, there is still present the status quo bias, which is harder to detect and to isolate. For this reason, we can assume that the residual of the irrational behavior that is still present, also after eliminating illusion of control and Bayesian updating, can be attributed to the status quo bias. We will now analyze the second group of treatments, and we compare the two groups. There is a huge gap and a common pattern between the score of the first four treatments (best strategy switch) and the last four (best strategy stick). This could be mainly explained because the task is easier since there is a double choice, and biases go in the same direction of the right choice of subjects. Comparing T5 with T6, we observe that the impact of the Bayesian updating is negligible ( – 5.52%) and not statistically significant (p-value 0.400). This happens because in making their decision, subjects already choose two boxes among three; hence, it is easier for them to understand the Bayesian dynamic. Thus, keeping or leaving the Bayesian updating does not affect the result if it goes in the same direction of the right choice. Things are different in T7, which is specular to T3, in which we isolate the illusion of control. In this case, the difference between T7 and T5 is – 15.52% and highly statistically significant (p-value 0.015). We can conclude that removing the illusion of control negatively affects the subjects’ performance. In the last treatment, T8, we eliminate both Bayesian updating and illusion of control together (as we did in T4), and this leads to a statistically significant drop of the percentage of the correct choice respect to T5 ( – 11.90%, p-value 0.052). Moreover, comparing the differences between T5-T6 and T7-T8, we can assess the impact of the Bayesian updating in this group of treatments. Previously, we stressed that Bayesian updating does not play an important role in this group of treatments, because the difference between T5 and T6, – 5.52% (p-value 0.40), is not statistically significant. This result is confirmed looking at the difference between T7 and T8, because the performance varies practically for the same size, – 5.39% (p-value 0.819), that in turn is not statistically significant.

All in all, we propose a logit regression model to (i) summarize the results outlined in Fig. 1 and (ii) to control the effects of age, gender, education and employment status. We propose two versions of the results. In Table 4, we separate the regressions in accordance with the optimal strategy to be adopted, since as discussed before, it is possible to observe a different behavior. Specifically, from T1 to T4, the removal of biases improves the ratio of optimal choices, while from T5 to T8, biases removal leads to a reduction of it. Hence, we investigate if there is a relation between the diversity of outcome and subject personal traits. We propose two versions of each model: a reduced form, considering only the average treatment effect and the complete form, including the aforementioned socio-demographic characteristics. We also report the marginal effects to enhance the interpretability of the results. In Table 5, we repeat the analysis considering the full dataset.

As it can be noticed, different levels of age, gender and employment status do not lead to a significant variation in the optimal choice ratio. All the average treatment effects discussed above are confirmed by the regressions performed. This aspect is evident in both Tables 4 and 5. Moreover, Table 4 confirms the evidence described above: in the first four treatments (T1–T4), the removal of biases favors the identification of the optimal choices (as it can be noticed by observing the positive sign of the coefficient associated to T2, T3 and T4), while in the latter block (T5–T8), the removal of biases makes it more difficult to identify the optimal choice. For completeness, we check whether personal characteristics might be specifically related to a particular bias (i.e. to a specific treatment). Results are not different, enhancing the robustness of the abovementioned consideration (see Annex 2).

4 Further extensions

In the proposed artefactual field experiment, the selected sample is heterogeneous and considers different population groups. It might be worthy to investigate how different skilled subjects’ respond to the proposed dilemma. We repeated exactly the same experiment using an online platform. We administered questionnaires addressing it to specific groups: (i) students (417 participants), (ii) former students (21 participants) and (iii) experts in the economic area (172 participants). An incentivized (a) and a non-incentivized (b) classroom experiment was carried out, respectively, while for the third case, a non-incentivized experiment was administered through the Economic Science Association (ESA) mailing list. At the end of the data collections, for the incentivized (a), one of the students was randomly chosen and he/she won the prize of 10 euros. Figure 2 summarizes the main results.

Focusing on T1, the control treatment in which all three biases are present, the share of subjects who took the optimal choice was 10% in the artefactual field experiment, in these other experiments, we can observe a homogeneous behavior among subjects, except for the expert sample (67%). The percentage of optimal choice is 9% in the non-incentivized experiment, and 17% in the incentivized one. In all the other treatments, we cannot observe a significant difference in choosing except for the non-incentivized former students and the expert subjects. The former students show a less understanding of the game, they have the worse percentage of optimal choice per treatment. The experts seem to recognize the Monty Hall problem and its resolution, they choose the optimal choice in both Treatment 1 (67%) and Treatment 3 (67%). This allows us to assume that experts are not affected by illusion of control but when we remove the Bayesian updating for them is less easy to recognize the theoretical game. Considering the other treatments, from T5 to T8, we can confirm expert awareness about the game as they identify “stay” as optimal choice, as well as the ability of the other two groups. Thus, it is easier to recognize the optimal choice when it goes in the same direction as biases.

5 Conclusion

The main goal of our experiment has been to identify and quantify the biases behind the anomalous behavior of people when they deal with the Three Doors dilemma.

We provide an artefactual field experiment, carried out in a mall in Bari (Italy), to isolate the different reasons behind the irrational choice of participants. According to the experimental results, we can quantify the size and the impact of three main biases that explain the anomalous behavior of participants: Bayesian updating, illusion of control and status quo bias.

Our main considerations have been clear: the biases may be overlapping, indirectly confirming that subjects are affected by more than a bias only. As we can see from the results, we are not able to isolate and detect the status quo bias (T4 and T8); for this reason, we can assume that the residual of the irrational behavior that is still present, also after eliminating the other two biases, can be attributed to this one.

Another important observation is that in the second group of treatments, in which the right decision is to stay, we registered higher percentage of optimal choice, this is because, subjects already choose two boxes among three; hence, it is easier for them to understand the Bayesian dynamic. Thus, keeping or leaving the Bayesian updating does not affect the result if it goes in the same direction of the right choice.

Testing this anomalous behavior of people when they deal with the Monty Hall dilemma, we wanted to verify if socio-demographic aspects could have some effects on the subjects’ decisions. We can affirm that different levels of age, gender and employment status do not lead to a significant variation in the optimal choice ratio.

To conclude, we investigated how differently skilled subjects’ respond to the proposed dilemma. We repeated the experiment addressing it to three different groups: experts, incentivized and non-incentivized students.

From the results emerge two important aspects. Experts know the game and make the right decision, even if when the treatment is not the traditional one, they are able to reconnect it with the theoretical game. Thus, it allows us to suppose that they are not affected by the illusion of control bias. The other important aspect is that non-incentivized students perform worse in almost all the treatments compared to the other groups.

Notes

vos Savant, Marilyn (17 February 1991a). "Ask Marilyn". Parade Magazine: 12.

See the “Sunk cost fallacy”: Arkes & Blumer, The psychology of sunk cost (1985); the “Prospect theory”: D. Kahneman & A. Tversky, (1979).

See the “Sleeping Beauty problem”, Baratgin and Walliser, 2010; Mandel, 2014.

In that case, an upward counterfactual thinking (i.e., simulating alternatives that are more desirable than reality; Markman, Gavanski, Sherman, & McMullen, 1993) has been applied.

N = 80 in T1, N = 72 in T2, N = 88 in T3, N = 79 in T4, N = 96 in T5, N = 88 in T6, N = 87 in T7 and N = 91 in T8.

In case of repeated games, we report the result of the first period of the experiment in the similar treatment.

References

Bailey, H. (2000). Monty hall uses a mixed strategy. Mathematics Magazine, 73(2), 135–141.

Baratgin, J. (2015). Rationality, the Bayesian standpoint, and the Monty-Hall problem. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1168.

Bennett, Kevin L. (2018), "Teaching the Monty Hall Dilemma to Explore Decision-Making, Probability, and Regret in Behavioral Science Classrooms", International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning: Vol. 12: No. 2, Article 13.

D’Ariano, G. M., Gill, R. D., Keyl, M., Werner, R. F., Kummerer, B., & Maassen, H. (2002). “The Quantum Monty Hall Problem”, Quantum information and computation. Physical Review A, 2, 355–466.

Fernandez, L., & Piron, R. (1999). Should She Switch? A Game-Theoretic Analysis of the Monty Hall Problem. Mathematics Magazine, 72(3), 214–217.

Flitney, A. P., & Abbott, D. (2001). Quantum version of the Monty Hall problem. Phisical review A, 65, 062318.

Franco-Watkins, A., Derks, P., & Dougherty, M. (2003). Reasoning in the Monty Hall problem: Examining choice behaviour and probability judgements. Thinking & Reasoning, 9(1), 67–90.

Friedman D. (1998), “Monty Hall's Three Doors: Construction and Deconstruction of a Choice Anomaly Author(s)”, The American Economic Review, Vol. 88, No. 4 (Sep., 1998), pp. 933–946.

Gill, R. D. (2011). The Monty Hall problem is not a probability puzzle (It’s a challenge in mathematical modelling). Statistica Neerlandica, 65(1), 58–71.

Goldstein, M. (2006). Subjective Bayesian Analysis: Principles and Practice. Bayesian Analysis, 1(3), 403–420.

Lucas, S., Rosenhouse, J., & Schepler, A. (2009). The Monty Hall Problem, Reconsidered. Mathematics Magazine, 82(5), 332–342.

Morone A., Fiore A. (2008), “Monty Hall’s Three Doors for Dummies”. In: Abdellaoui M., Hey J.D. (eds) Advances in Decision Making Under Risk and Uncertainty. Theory and Decision Library (Series C: Game Theory, Mathematical Programming and Operations Research), vol 42. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Palacios-Huerta, I. (2003). Learning to open Monty Hall’s doors. Experimental Economics, 6, 235–251.

Petrocelli, J., & Harris, A. K. (2011). Learning Inhibition in the Monty Hall Problem: The Role of Dysfunctional Counterfactual Prescriptions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(10), 1297–1311.

Rosenthal, J. S. (2008). Monty Hall, Monty Fall, Monty Crawl. Math Horizons, 16(1), 5–7.

Schuller, J. C. (2012). The malicious host: a minimax solution of the Monty Hall problem. Journal of Applied Statistics, 39(1), 215–221.

Slembeck, T., & Tyran, J. R. (2004). Do institutions promote rationality? An experimental study of the three-door anomaly. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 54(2004), 337–350.

Sprenger, J. (2010). Probability, rational single-case decisions and the Monty Hall Problem. Synthese, 174, 331–340.

Wang J. L., Tina Tran, Fisseha Abebe (2016), “Maximum Entropy and Bayesian Inference for the Monty Hall Problem”, Journal of Applied Mathematics and Physics, 2016, 4, 1222–1230

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Bari Aldo Moro within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Annex 1

Annex 2

In this Annex we report, for each treatment, a logit model checking for the existence of a possible statistically significant relation between the optimal choice and personal traits. As it can be observed, there are only some isolated cases of statistical significance with regard the occupational status, since employed (reference category) performed better in T7, while there is no age, gender and education effect. It is difficult to draw some conclusions from the effect found in T7 where the illusion of control is removed, since in the correspondent treatment T3 the same effect for employed people vanishes. Likewise, this effect does not exist in the treatment of the same block (T5–T8) Table 6.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Morone, A., Caferra, R., Casamassima, A. et al. Three doors anomaly, “should I stay, or should I go”: an artefactual field experiment. Theory Decis 91, 357–376 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-021-09809-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-021-09809-0