Abstract

With student loan borrowing becoming an increasingly common experience in U.S. households, it is crucial to understand the interpersonal manifestation of education debt within family systems. This study sought to understand how accruing and repaying student loan debt for one’s own higher education relates to family dynamics and communication within families. Leveraging Family Communication Patterns Theory, this study asked: How do student loan borrowers describe loan-related family communication patterns prior to loan accrual and during the repayment period? Utilizing qualitative and quantitative data collected through a concurrent nested mixed methods study design, findings from this study profile family communication typologies leading up to, and during, student loan repayment. Study findings suggest that the ways in which families communicate about student loans prior to loan accrual and during repayment (a) relate to family financial socialization processes and (b) play at least a partial role in how they experience student loans as part of their overall family dynamics. This study proposes a model of loan-related family communication dynamics and offers implications for future scholarship and practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

While many would argue that the value of a higher education degree persists over time, others would suggest that the costs of pursuing higher education impose effects that increasingly constrain individual and family financial wellbeing (Iacoviello, 2008). A growing body of literature points to ways in which large amounts of student loan debt can impact multiple domains of borrowers’ lives, ranging from marriage and childbearing (Gicheva, 2011; Nau et al., 2015) to home buying (Danziger & Ratner, 2010; Fitzpatrick & Turner, 2007), career choices (Rothstein & Rouse, 2011), and pursuit of additional higher education (Millett, 2003).

Despite growing research about impacts of carrying student loan debt on individual wellbeing and family formation, considerably less research has focused on the interpersonal manifestation of student loan debt within family systems. It is widely-recognized within family scholarship that within most family systems, family members influence, and are influenced by, each other’s lives and decisions (Corey, 2005). Previous research has suggested that nowhere is a family’s “influence on individual behaviors more profound than in the area of communicative behaviors” (Koerner & Fitzpatrick, 2002, p. 36). Thus, as critical as it may be to understand decisions and effects of student loans for individuals, it is equally important to situate borrowers’ experiences within their larger family systems. Building on previous family financial socialization research, this study explores how student loan borrowers communicate about student loans within their family system of origin, (henceforth in this paper simply referred to as family system).

To date, qualitative research has largely focused on family decision making processes about attitudes toward borrowing and experiences with the financial aid application process and quantitative research has focused more on incidence of student loans across different demographics of student loan borrowers and impacts of loans on borrowers’ abilities to reach traditional markers of adulthood (see Akers & Chingos, 2016; Cho et al., 2015; Chudry et al., 2011; Gicheva & Thompson 2015; Johnson, 2012). Little empirical research has been conducted about loan-related family communication leading up to the accrual of student loans, with even less focused on family communication during repayment (McHugh, 2017; Miller, 2019). Therefore, the question of “How are student loans actually discussed within families, both before taking them on and during repayment,” remains unanswered. Because family financial socialization (and, within it, family communication about finances) is tied to financial literacy and overall financial wellbeing (Fan & Chatterjee, 2019; Jorgensen & Savla, 2010), it is crucial to understand trends in family communication about student loans. Drawing on family financial socialization literature and a concurrent nested mixed methods design, this research seeks to understand how student loans are discussed and experienced within family systems. Specifically, this study focuses on how people who borrowed for their own undergraduate and/or graduate education perceive family communication patterns about student loans before accrual and during the repayment period. Findings from this exploratory study may inform financial professionals’ understandings of how to educate, prepare, and support student loan borrowers and their families in achieving financial wellbeing.

Background

Broadly defined, financial socialization is a process through which individuals cultivate financial knowledge, attitudes, norms, and personal styles of management and behaviors, all of which ultimately contribute to financial wellbeing (Danes, 1994; Gudmunson et al., 2016; Kim & Chatterjee, 2013). Within the specific context of family systems, financial socialization is predominantly regarded as a non-purposive process that manifests from daily interaction patterns (Gudmunson & Danes, 2011; Jorgensen & Savla, 2010). Parents are often regarded as some of the earliest and most influential agents of financial socialization- teaching, reinforcing, and modeling financial attitudes and behaviors both directly and indirectly (Gudmunson & Danes, 2011; Moschis, 1985).

Family Financial Socialization Factors Associated with Student Loan Accrual and Repayment

Previous family financial socialization research has explored how factors can influence relational impacts of financial decisions in the family, including availability of resources, gender and cultural expectations, and family make-up (Hsiung, Ruth, & Bagozzi, 2012; Levy, Murphy, & Lee, 2008). Other influential factors in relational repercussions of family finances include social roles of family members, financial communication and socialization within the family (including extent of self-disclosure about finances), and financial literacy (Danes & Yang, 2014; Edwards, Allen, & Hayhoe, 2007; Gudmunson & Danes, 2011). More specific to student loans, previous research suggests that characteristics of a borrower’s family of origin are the most influential factor in their ability to pay for higher education, and thus their potential need to take on loans (Akers & Chingos, 2016; Furquim et al., 2017; Houle, 2014; Jackson & Reynolds, 2013; Kim et al., 2017; Lee & Mueller, 2014). According to a study conducted by Sallie Mae (2018), 53% of families borrowed for the 2017–2018 academic year in order to pay for a child’s undergraduate education. In 32% of the families who had borrowed, only the student borrowed; in 14%, only the parent(s) borrowed; in the remaining 7%, both student and parent(s) borrowed.

Fan and Chatterjee (2019) proposed a conceptual framework of financial socialization and student loan attitudes and behaviors that integrates financial knowledge and socialization agents, debt-related characteristics, and sociodemographic characteristics with financial attitudes and behaviors related to student loans. Among other findings, their results showed that borrowers who received financial education from their parents as well as in academic or professional settings made more timely student loan payments and reported less worry about their student loan debt relative to those who had received less financial education. Taken together, this work points to the close ties between family financial socialization and student loan accrual and repayment as financial behaviors.

Understanding Overt Family Communication Patterns as One Aspect of Family Financial Socialization

Referring to both overt and nonverbal communication processes, family communication about finances is one of the many pillars of family financial socialization research (Moschis, 1985). Understanding family financial communication patterns are important because they can serve as meaningful predictors of childrens’ financial attitudes, beliefs, values, and behaviors, including but not limited to, student loan accrual and repayment (Fan & Chatterjee, 2019; Jorgensen & Savla, 2010; Moschis, 1985). For the purposes of this paper, overt family financial communication will be highlighted and thus, henceforth mentions of “family financial communication” can be assumed to mean overt family communication about finances.

In general, research has shown that when emerging adults perceive higher quality of communication with parents about finances, they report a greater sense of personal wellbeing and less psychological distress (Serido et al., 2010). With that said, much research in the financial socialization literature has focused on parents’ avoidance of financial conversations with children and, as a corollary, how children are socialized to view finances as a taboo topic of conversation within families (Romo, 2011; Romo & Vangelisti, 2014; Trachtman, 1999). With finances often treated as a private matter, children tend to perceive thick privacy boundaries around their parents’ financial lives (Plander, 2013). In line with the notion of privacy, findings from several studies have suggested that family conversations about finances are treated, schematically, as similar to conversations about drinking, drugs, and smoking—with low to moderate levels of conversation and a general privileging of parents’ perspectives (Baxter & Akkoor, 2011; ING Direct, 2009; Romo & Vangelisti, 2011).

In regards to the financial behavior of interest in this paper, research has shown that family financial socialization- and more specifically, family financial communication norms- can influence attitudes and behaviors related to borrowing and credit. In fact, the way parents communicate financial topics to their children have been regarded as importantly as the topics themselves (Bandura, 1986; Solheim et al., 2011). For example, Pinto et al. (2005) found that college students who had received more information from parents about credit had lower credit card balances. Relatedly, Thorson and Kranstuber Horstman (2014) found that emerging adults’ propensities to discuss their credit card behaviors with parents in turn affected their knowledge of financial terms and subsequent credit behavior.

Family Communication Patterns Theory

Over a 40-year span, as Family Communication Patterns Theory (FCPT) has evolved, it has continued to assert that over time, as family members develop patterns of interpersonal communication, they develop models and expectations of family interaction and communication behavior (referred to as schemata) which in turn influence family culture (Koerner & Fitzpatrick, 2002). The schemata developed through FCPT “serve as models for family communication through time” (Koerner & Fitzpatrick, 2002, p. 486) and have been shown to predict social and behavioral outcomes in multiple contexts (Schrodt et al., 2008).

Originally based on Newcomb’s (1953) A-B-X communication paradigm and then adapted by McLeod and Chaffee (1973) and Ritchie (1991), FCPT now includes a typology of parent–child communication structures and patterns. These schemata exist on spectrums of conversation and conformity orientation, which combine to create four distinct typologies of family communication (see Fig. 1). In FCPT, conversation orientation is defined best as forging a “climate where all members are encouraged to participate freely in interaction” (Koerner & Fitzpatrick, 2002, p. 85). Families high in conversation orientation are those where members feel free to interact, disagree, and weigh in on decision making fully, whereas families low in conversation orientation tend to solicit each other’s opinions and private thoughts less frequently and across a narrower breadth of topics.

adapted from Koerner & Fitzpatrick, 2006, p. 57)

Family communication types according to family communication patterns theory (

Relatedly, conformity orientation is defined as honing a “homogeneity of attitudes, values, and beliefs” (Koerner & Fitzpatrick, 2002, p. 85). Families high in conformity orientation tend to interact in ways that promote uniformity of attitudes and beliefs, most often engaging in conversations that promote a culture of agreement of shared family views. Moreover, families high in conformity orientation tend to privilege parents’ perspectives, which leads to a top-down process of decision making. On the flipside, families low in conformity orientation tend to promote unique opinions of individual family members and value equality among all family members with relatively less emphasis on hierarchy. These families also tend to engage more in conversations that emphasize individuality and independent growth of each family member (Koerner & Fitzpatrick, 2002). These schemata play important roles in contextualizing individuals’ experiences of phenomena within their enduring family communication patterns.

Previous studies involving FCPT have made multiple connections with financial socialization research- most notably that “family communication patterns may enhance or temper parents’ influence over their children’s attitudes, values, and behaviors” (Thorson & Kranstuber Horstman, 2014, p. 488). More specifically, studies have found that family communication schemata have been linked to family purchase decisions (Kim et al., 2009) and emerging adults’ communication styles regarding credit card spending (Baxter & Akkoor, 2011; Thorson & Kranstuber Horstman, 2014). Thorson and Kranstuber Horstman (2014) also suggest that research connecting FCPT with financial talk and behaviors within families has been more limited than one would expect, particularly in FCPT’s most updated conceptualization.

Based on Koerner and Fitzpatrick’s (2002) theory, we posed the first research question- that is, how do family communication patterns manifest before accruing student loans? Due to FCPT’s emphasis on decision-making processes, the theory applies neatly to family communication before accruing loans. However, in asking the second research question- what are profiles in loan-related family communication patterns during the repayment period- we anticipated some differences and similarities compared with the pre-accrual period. On one hand, the schemata Koerner and Fitzpatrick (2002) detail as part of FCPT would theoretically extend as enduring styles of communication in families. On the other hand, we anticipated that any kind of trends in loan-related family communication may diverge in its nuances.

Methods

Study Design

This exploratory study utilized a single-sample, concurrent nested mixed methods design, in which multiple sources of data are collected with the same participants and within the same stage and one form of data is given more weight than the other (Castro et al., 2010; Creswell et al., 2003). In the case of this research, additional emphasis was placed on qualitative data. The goal of using mixed methods for this research was to triangulate data and methods to develop a rich and multi-layered understanding of a largely-unexplored study area (Greene, 2007). Given the dearth of scholarship about family communication patterns and student loan borrowing, a mixed methods design was also well-suited to capture narrative accounts of attitudinal and behavioral processes along with more numerically-measurable outcomes (Bronstein & Kovacs, 2013). Alone, qualitative and quantitative approaches offer valuable insights into a complex topic such as this one, yet by examining data using complementary methods, it becomes possible to develop an even richer and multi-layered understanding of the largely-unexplored areas this particular study pursues (Patton, 2002). Quantitative data provided information for descriptive purposes and served as a vehicle for understanding the breadth of participants’ attitudes and experiences. Qualitative data aimed to generate a nuanced understanding of participants’ attitudes and experiences related to their student loans within family systems and longevity planning contexts.

Data Collection

Data collection for this study took place in Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA, between February and September of 2018. The study was approved by The Committee on the Use of Humans as Experimental Subjects (COUHES) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Protocol 208540).

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was a 95-item instrument designed to measure the experiences of carrying student loans, how loans interact with people’s spending and saving priorities, borrowers’ relationships with other family members, and attitudes and behaviors surrounding saving for retirement. The questionnaire was administered via computer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology via Qualtrics, an online survey platform, after participants completed their consent forms. All questionnaires were completed within 30 min.

For the purposes of this analysis, five items were included in the quantitative analysis. First, participants were asked, “Has there been any kind of conflict or friction in your family related to your student loans? (Yes, no, don’t know). Second, those who answered yes were then prompted, “please briefly explain the nature of the conflict or friction in your family related to student loans….” Third, participants were asked, “How have your student loans affected your relationships within your family?” (Positive effect, negative effect, both positive and negative effect, no effect, not applicable). Fourth, in a matrix format, participants were asked, “How would you say taking on student loans has affected your relationship(s) with the following?” People included in the matrix were “your mother, your father, your spouse/significant other, your grandparent(s), your stepmother, your stepfather, your sibling(s), your child(ren), someone else (please specify).” (Made it better, made it worse, no effect, not applicable). Fifth, participants were asked, “Did anyone in your family contribute to paying for your higher education? (Yes, no, don’t know).

Focus Groups

Immediately following completion of the questionnaire, participants engaged in a semi-structured focus group. Focus groups are a source of data collection used for research employing qualitative description approaches such as this study (Colorafi & Evans, 2016). Employing focus groups for research that may be regarded as sensitive or private can present some challenges and limitations in terms of rapport building and information sharing among participants, but if done well, previous research has shown that it can actually elicit even more information and depth about a topic compared with interviews (Guest et al., 2017; Wellings et al., 2000). Focus group prompts were created based on the research questions of interest, with the ultimate goal of illuminating the mechanisms through which student loan borrowers experienced their loans within family systems and longevity-planning contexts. In March and April, 2018, twelve groups were hosted, followed by two additional groups in September of 2018. Each focus group was video and audio-recorded for transcription and lasted between 1.75 and 2 hr. These fourteen study groups contain sufficient data to allow for meaningful comparisons. Participants were invited to participate in particular focus groups based on their level of education debt relative to their household income pre-taxes. For the purposes of this study, participants were characterized as having a level of current outstanding education debt that was either higher or lower than their household income pre-taxes.

Focus group prompts included for this analysis included:

-

How did you make the decision to take out student loans… did you talk to anyone about the decision? Who? Professionals? Family members?

-

Was there any kind of disagreement in your family about the decision to take on loans?

-

Did anyone in your family contribute to costs of your education either by paying directly to the college or by taking on loans? What kinds of support did they provide?

-

Did anyone in your family also take on loans for you to go to college? Who? How did those conversations go? Did your family make any stipulations about support for payment of your loans? Examples: having a particular major, needing to graduate, maintaining good grades, etc.?

-

What was the role of family in your decision to take on debt?

-

Was taking on student loans a result of your family’s financial situation in any way?

-

Did anyone else in your family have student loans when you took out loans? How did that affect your decision to take out your loans?

-

Have your student loans had any effect on relationships with other family members – parents, grandparents, siblings, etc.?

-

Since taking on student loans, have your family dynamics changed in any way? How?

-

If other family members contributed to the costs of your education, how has your relationship with them changed, if at all, since starting to repay your loans? How?

-

Since beginning to repay your loans, what kind of conversations (if any) have you had in your family about them?

-

Where do you go or whom do you talk to when you need advice about how to deal with financial decisions?

Study Sample and Characteristics

62 participants were included in this analysis, all of whom completed the online questionnaire and participated in a focus group. These 62 participants comprised a subset of cases (all of whom were repaying loans for themselves) drawn from a larger study (n = 88) that also included participants repaying loans for family members. The study relied on non-probability purposive sampling, an approach often used with qualitative research designs (Bradshaw et al., 2017). First, prospective participants were sent a brief online screener through Qualtrics that inquired about level of debt, degree(s) for which loans were accrued, age, gender, race, income, and availability to travel locally to (The Massachusetts Institute of Technology campus) for the study. Next, select individuals were invited to participate based on their specific relationship with education debt in order to gather information-rich cases, generate theory, and reach saturation. By selecting cases that maximized within-group diversity relevant to research questions through maximum variation sampling, it was possible to observe attitudes and experiences across age, debt burden, education level, wealth, socioeconomic status, race, gender, parenting and marital statuses (Teddlie & Yu, 2007). Participant recruitment was conducted through multiple outlets, including the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) AgeLab volunteer database, the MIT Human Resources Department, through social media outlets, and through distributing flyers across local neighborhoods. Participants were provided with a monetary incentive.

The study sample was limited to persons who: were between the ages of 25 and 75; accrued student loans for themselves; read and spoke fluent English; and were still making payments on student loans, or planned to make payments on student loans in the future if the loans were currently in deferment, forbearance or default. While these situations are distinct, the knowledge of ultimately being responsible for repayment is a commonality. The study sample was also limited to those who had accrued student loans that were used toward a not-for-profit institution in the United States (including public and private schools) from which the student graduated within 6 years (i.e., enrolling in 1975 and graduating in/by 1981 or enrolling in 2006 and graduating in/by 2013, etc.). Borrowers with loans used toward for-profit schools were excluded due to disproportionately high loan totals and sustained financial vulnerability (Deming et al., 2012). And, given that recent national 6-year completion rates for undergraduates were 58.3% (Shapiro et al., 2018) and that time-to-completion can be influenced by a variety of academic and non-academic factors (Su et al., 2019), researchers sought to maintain a degree of similarity in participants’ rates of time-to-degree-completion.

Of the subset of cases drawn from the overall study, participants represented a mix of ages: 50.0% (n = 31) of borrowers were ages 25–35, 32.3% (n = 20) were ages 36–50, and 17.7% (n = 11) of participants were ages 51 or older. The majority of participants identified as White, female, without children, never married, and working full or part time. See Table 1 for descriptive characteristics of the subset of cases included in this analysis. Participants represented a range of general financial situations, the results of which can be found in Table 2. Over half of all participants reported having a household income of $50,000 or more and the majority were not homeowners.

As Table 3 displays, a plurality of participants (39.2%, n = 24) took out and currently owed between $50,000 and $99,000 in student loan debt. A plurality had taken on loans for their undergraduate and graduate education. 40% (n = 20) had been making payments for four or fewer years and expected to finish repaying within 6 to 15 years from the time the study was done. The majority of participants were continuing-generation (rather than first-generation) college students and had less current outstanding education debt compared with their household income pre-taxes.

Data Analysis

Quantitative Analysis

For the quantitative analysis, after questionnaire data were collected via Qualtrics, data were downloaded to SPSS Version 25.0, cleaned for inconsistencies, and recoded for analysis. Where possible, any missing questionnaire data were replaced by responses provided during the focus groups. Frequencies and crosstabs were used in the analysis of the quantitative data.

Qualitative Analysis

The qualitative component of this study was conducted using a qualitative description approach. Qualitative description inductively analyzes data by focusing on the meaning participants ascribe to phenomena and the contexts in which those meanings are derived (Creswell, 2014; Denzin & Lincoln, 2005; Sandelowski, 2000). Qualitative description strives to provide a rich and straightforward description of participants’ experiences with a phenomenon that is not fully understood (Sullivan-Bolyai et al., 2005). In line with the philosophical underpinnings of qualitative descriptive research- specifically its alignment with the naturalistic approach- this research focused on understanding study phenomena “through accessing the meanings participants ascribe to them” (Bradshaw et al., 2017, p. 2). The approach aims to maximize the presentation of factual information and minimize abstraction, rendering it well-suited for this research study for several reasons. First, the value of qualitative description rests on its close proximity to participants’ original words. Given the study’s focus, much of the participants’ language centered on terminology and jargon specific to finances. Rather than striving to interpret the data or make inferences through phenomenology and/or grounded theory, staying close to the surface of the language allowed for a deepened understanding of the financial realities borrowers experience, promoting descriptive and interpretive validity (Sandelowski, 2000, 2010). Further, qualitative description was a good fit for exploratory research like this where the goal is to make concrete (rather than abstract) discoveries about understudied phenomena (Sandelowski, 2000).

With its emphasis on the systematic classification of qualitative data through coding and identification of themes and patterns, content analysis was used as a strategy for locating the meaning of data and classifying data into categories of related meanings (Cho & Lee, 2014; Schreier, 2012). Qualitative content analysis is leveraged to “answer questions such as what, why and how, and the common patterns in the data are searched for” by coding and categorizing text with shared meaning (Heikkilä & Ekman, 2003, p. 138). Moreover, quantification of qualitative data through coding is conducive to qualitative description’s goal of minimizing abstraction (Sandelowski, 2000). Codes were developed both inductively (directly from the data) and deductively (through preconceived codes based in part on FCPT) (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). In line with the qualitative descriptive approach, codes were primarily created based on manifest content as well as minimally-interpretative latent content undergirding the meaning of the text (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004; Schreier, 2012).

To improve the reliability of qualitative results, multiple coders independently coded each transcript and reached a consensus on coding decisions. Undergoing an iterative process that Creswell (2014) referred to as “The Data Analysis Spiral,” the researchers read and reviewed transcripts multiple times and refined themes, subthemes, and codes. First, all three coders coded the same three transcripts, generating an initial codebook. While reviewing coding decisions and reaching consensus on each coding decision, a subsequent codebook with modified and more nuanced themes, sub-themes, sub-sub-themes, and codes was created. Using this more updated codebook, two coders then coded each remaining transcript and compared coding decisions with the goal of reaching consensus. Ultimately, there were eight categories of codes, with 45 sub-categories, 20 sub-sub-categories, and 552 codes assigned. The eight categories of codes were “aging-related, coders’ commentary; decision to take on loans; loans in your life; money management; perceptions of loans; relationships; relevant background.” This paper draws on a smaller subset of categories and codes most relevant to the research questions at hand.

Mixed Methods Analysis

Data sources were mixed in multiple ways, including during the formal qualitative and quantitative analysis stages and throughout the writing of this paper. As it evolved, the qualitative codebook was partially informed by quantitative results. For instance, while “conflict with family about loans” may not have been its own code based on the first three transcripts that were coded as a group, survey results pointing to rates of family conflict made it clear that it should be its own code in the qualitative data in case it emerged through analysis. In other cases, qualitative data were quantified. While family communication patterns pre-accrual and typologies during repayment were not asked in the survey, two additional variables were created in the survey based on participants’ comments in focus groups about family communication and decision-making. Finally, throughout this paper, quantitative results provide additional context for some participants’ comments in focus groups (e.g., related to first-generation college student status) and vice-versa, with qualitative results providing additional context for some survey results (e.g., related to the nature of family conflict). In this way, the qualitative and quantitative data played complementary roles in exploring research questions, with qualitative results leading in the concurrent nested mixed methods design.

Results

Loan-Related Family Communication Before Accruing Student Loans: Qualitative Findings

Qualitative results paint a complex picture of loan-related family communication and decision-making dynamics leading up to loan accrual. In focus groups, participants described conversations with their parents leading up to the time at which they accrued loans. From focus groups, four discrete typologies were identified that were categorized according to Family Communication Patterns Theory. These typologies are identified in existing literature as the following: Laissez-faire, Protective, Pluralistic, and Consensual. Table 4 lists all codes included in these results and Table 5 lists examples of codes associated with each schemata. The intersection of schemata (e.g., low conversation orientation and high conformity orientation, high conversation orientation and high conformity orientation, etc.) create each of the typologies below.

Laissez-Fare and Protective Families: Relatively Little Overt Loan-Related Communication with Parent(s) Before Accruing Student Loans

Participants who described having Laissez-faire and Protective family communication typologies often portrayed conversations with their parents about accruing loans as minimal. This profile can be traced to several likely explanations that were not mutually-exclusive: (a) Slightly over half of all participants (n = 33 of 62, 53.2%) stated that loans were the only perceived option for financing their higher education. Thus, it felt unnecessary to involve other family members in the decision, especially when participants had sole responsibility for funding their college education (which was common among participants with low conversation orientations); (b) 12.9% (n = 8) of participants described how their parents were not financially literate about loans and thus involving them would not have been especially helpful; or (c) That same percentage (12.9%) of participants recalled not involving their parents in the decision to take on loans in an effort to not burden them.

In addition to these specific attributes, many participants with Laissez-faire and Protective family communication styles simply described conversations with parents about student loans as extensions of their ongoing styles of communication with parents- that is, with an enduring low level of conversation orientation in general. Below, Diego, Jane, and Kathy speak to ways in which low conversation orientations contributed to fairly limited involvement from parents leading up to the time at which the participants took on student loans.

Laissez-Faire Families

Just over sixty-six percent (66.1%, n = 41) of all participants in the sample were coded in the focus groups as having had Laissez-faire family communication patterns with their families leading up to taking on loans. Participants with Laissez-faire styles of communication with their parents before accruing loans were those who described having low conversation orientations and low conformity orientations within their family. In other words, these participants typically reported limited conversations with parents about accruing loans and described their family as one in which all members were generally encouraged to make their own decisions, not necessarily privileging the parents’ perspective.

For instance, Diego, a 31 year old working as an engineer, recalled having minimal conversations with his parents about loans before taking them on. He had taken on $31,000 in undergraduate and graduate loans for himself and still owes $10,000. When asked to describe the experience of carrying student loans, he used the word “obligation.” Referring to the time at which he took on the loans, he was part of a large group of participants who described viewing them as his only option to pay for his education. And, like 27.4% of all participants with loans for themselves (n = 17), he also stated in a focus group that any family conversations leading up to his taking on loans for his undergraduate degree were more focused on pursuing, not paying for, a degree. He went on to explain that, as a first-generation college student, his family was not able to offer much in the way of advice about student loans, “so because of that, I’ve kind of been always on my [own], like doing research. So it was all internet-based in terms of me trying to figure out what was going on.” When asked if he and his family discussed student loans before accruing them and/or while repaying them, he responded, “Nah, not at all… I was on my own and ready to go, so they just kind of said pay your loans, do your stuff, but it really never came up.”

In another case, Jane, 37, took on $20,000 in loans for her undergraduate education and currently owes $1,500. She was working in the gig economy (De Stefano, 2015), walking dogs and driving Uber, and described her loans in one word as “an obstacle.” Like other participants who expressed not wanting to burden their parents, she recalled making the decision to take out student loans as an act of human agency: “I do remember [thinking] this was my choice… This is not my parents’ responsibility. It’s mine, so I will pay these loans.” She clarified, “I think the only thing I ever thought was—and that I may have said to my mother…I just don’t want this to burden me for the rest of my life.” Jane recalled her mother saying “The education you get will be worth it. So that’s what you have to think about…” In this way, Jane framed the limited conversations with her mother about loans as just one piece of her decision to accrue them. She also echoed Diego’s recollection of conversations with parents centering on the value of the degree, not about the mechanics of paying for it.

Protective Families

Just over eleven percent (11.3%, n = 7) of all participants in the sample were coded in the focus groups as having had Protective family communication patterns with their families leading up to taking on loans. Protective families are identified as those with low conversation and high conformity orientation. Like families with Laissez-faire styles of communication, Protective families typically have more limited and less open conversation as part of their ongoing family financial socialization. Unlike those with Laissez-faire styles of communication, however, Protective families emphasize agreement within the family, with a particular emphasis on deference to parental authority. One example is Kathy, 72, who framed her family of origin’s communication style as relevant to her decision to take on loans. At the time of the focus group, she was semi-retired and working in several part-time positions when her health allowed. She had taken on $25,000 in student loans for her undergraduate education when she was 40 years old and currently owes $35,000. Kathy explained that she graduated from high school in the early 1960s and grew up in a large family.

Given the time period and her description of a high conformity orientation in her family, her experience of having minimal conversations with her parents about college was not uncommon. However, in framing her family’s high conformity orientation, she shared that she had little choice but to accept the gendered norms related to paying for college. According to Kathy, “I felt angry at my parents, at the time, that they gave support—not financial support, but they gave support for my brothers to go to college. I got no support and there was never any dialogue about [my] going to college in the house. Never.” And so, after graduating college, Kathy got married and worked as a small business owner as she raised her children. Then, when her children began their own college educations (for which they took on loans and she did not), Kathy decided to pursue her lifelong dream of earning a college degree, herself. She was part of the 11.3% of participants (n = 7), all but one of whom were women, who explained in focus groups that “college was on my bucket list.”

Pluralistic and Consensual Families: Relatively More Overt Loan-Related Communication with Parent(s) Before Accruing Student Loans

In focus groups, participants who described having Pluralistic and Consensual family communication typologies often portrayed their parents’ involvement in the decision to take on loans as more involved compared to their Laissez-faire and Protective counterparts. Generally, these higher levels of parental involvement could be traced to (a) pragmatic conversations between participants and parents in which repayment responsibility was negotiated based on cost-efficiency; (b) conversations in which parents made their willingness to share loan borrowing responsibility conditional based on several factors; or (c) higher incidence of shared borrowing status, meaning parents may have taken on additional loans for participant’s education and/or may have been helping them to repay the loans. And, as with previous participants, some described the open communication with their parents leading up to taking on loans as similar to communication in which they were accustomed to engaging with their parents. Here, Charles and Brent (both of whom had shared borrowing status) speak to ways in which high conversation orientations contributed to more involvement from parents leading up to time at which the participants took on student loans.

Pluralistic Families

Just over eight percent (8.1%, n = 5) of all participants in the sample were coded in the focus groups as having had Pluralistic family communication patterns with their families leading up to taking on loans. Pluralistic families are those defined as high in conversation orientation (whereby topics are discussed openly among parents and children) and low in conformity orientation (whereby family members do not necessarily feel compelled to agree on all topics, nor do they expect that parents’ perspectives should be privileged over children’s perspectives).

Charles, a 28 year old engineer, framed his family communication style as pluralistic. He started with approximately $10,000 in undergraduate and graduate loans for himself and currently owes $85,000, described the loans as “a limitation.” As the first in his family to attend a 4-year college, he took it upon himself to strategize paying the difference between what his parents could contribute (through a 529 college savings plan) and what the overall costs of college would be. He was one of 24.2% of participants (n = 15) who could be characterized as a financial hobbyist—someone who is savvy about financial management and enjoys learning about finances. From Charles’ descriptions, it became clear that in his family, the financial know-how he had developed rendered his opinions about financial matters as influential as his parents’, which in this case contributed to his family’s low conformity orientation. Charles explained how, in his first year of college, his mother took out a private loan on his behalf, but that before beginning his second year of college, he approached his mother with a proposal: “I was like, ‘Mom, [Parent PLUS loans] are a better deal. I’ll pay for them.’ So the next year, she did that. It was my idea for her to take them out… I said, ‘These are my loans. You’re just taking them out because it’s a better deal.’” The fact that Charles and his mother shared loan borrowing status for his education gave them a starting point for mutual involvement in loan-related repayment decisions.

Consensual Families

Over six percent (6.5%, n = 4) of all participants in the sample were coded in the focus groups as having had Consensual family communication patterns with their families leading up to taking on loans. Consensual families are typified as those high in conversation and conformity orientations, meaning families speak freely and openly, emphasizing agreement but generally privileging parents’ perspectives over children’s’ perspectives. Often, these participants explained how, before taking on loans, their parents had made clear their conditional willingness to contribute to costs of their child(ren)’s college education based on a variety of factors—most often including cost, degree level, type of school, academic performance, and/or part-time work expectations from their child. For example, Patrick, a 34 year old truck driver who referred to the student loans as “just a bill” had taken on $35,000 in undergraduate loans and still owed $11,000. He recalled conversations with his parents about paying for college, “My parents told me… They were like, “If you want to go [to a private school], you’re going to have debt for a long time. I was 18. [laughter] Didn’t think anything of it. But a little different now.” He went on to explain, “They would have rather had me go to [a state school], but they weren’t going to say, ‘No, you absolutely can’t afford it.’ There’s people that have money to lend, so you’re going to get loans, and if you really want to go to [a private school], then you’re going to have to pay for it.”

Like some of his peers, he stated that his parents had also taken on loans for him to attend college: “My mom said, ‘You’re taking out loans, but I’m taking out loans, too.’” Like 20.9% of other participants with loans for themselves who reported having some sort of expectations in place in exchange for financial support to pay for college (n = 13), Patrick recalled the stipulations his mother set: “But if you don’t graduate or you get kicked out, you’re going to be in trouble. You’re going to have to pay me back eventually, too.’ Gave me a little impetus to actually graduate and kind of keep my nose as clean as I could.” In this way, Patrick spoke to ways in which (a) his parents’ also carrying loans for his education, paired with (b) his family’s high conversation and conformity orientations, contributed to his parents’ high level of involvement in the decision to take on loans.

Loan-Related Family Communication Before Accruing Student Loans: Mixed Methods Findings

Quantitative results suggest a clear bifurcation in participants’ reports of family communication about taking on loans, whereby participants either identified as the primary decision maker to take on loans or reported relatively low levels of involvement, with little variation in between. Quantitative data alone showed that 44 participants (70.9%) reported that they were the primary decision maker to take out the loans. Combining data sources by coding and quantifying the number and distribution of Family Communication Pattern schemata revealed that of those 44 participants who identified as the primary decision maker in the survey, 74.4% (n = 33) were coded in focus groups as having Laissez-faire communication patterns with their families leading up to loan accrual, meaning low conversation orientation and low conformity orientation. In the survey, 27.4% of participants reported that their parent(s) was(were) the primary decision maker, the greatest number of whom were coded as having Laissez-faire (n = 8) or Protective (n = 5) family communication patterns leading up to loan accrual. The one participant (1.7%) in the survey who reported that someone else was the primary decision maker also was coded as having a Laissez-faire family communication pattern.

Mixing qualitative and quantitative (demographic) data, a plurality of participants in each age group (25–35, 36–50, and 51–75) were coded as having Laissez-faire styles of communication. Specifically, 48.4% (n = 15) of participants ages 25–35, 81% (n = 17) of participants ages 36–50, and 90% (n = 9) of participants were coded as having Laissez-faire styles of family communication pre-loan accrual. Notably, 79.2% (n = 19) of participants who were the first in their family to attend college were coded as having had Laissez-faire styles of communication with their families leading up to taking on the loans, compared with 4.2% (n = 1) who were coded as having Pluralistic or Consensual communication patterns, respectively, and 12.5% whose communication patterns were uncategorized. Over sixty-eight percent (68.6%, n = 24) of women made statements in focus groups that categorized them as coming from Laissez-faire communication patterns, compared with 63% (n = 17) of men. The second most frequently assigned communication patterns were Protective (for women, 14.3%, n = 5) and Pluralistic (for men, 11.1%, n = 3). Finally, 74.1% (n = 20) of participants who reported in the survey that no one else had helped pay for them to attend college were coded as having Laissez-faire styles of family communication leading up to taking on the loans, while 60% (n = 21) of participants who did report receiving help paying for college also were coded as having Laissez-faire styles of family communication.

Patterns of Family Communication About Loans During Repayment: Qualitative Findings

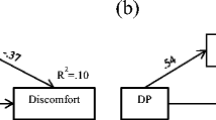

Focus groups pointed to trends in response to four distinct typologies of loan-related family communication during the period of repayment. Examples of assigned codes can be found in Table 6. See Fig. 2 for an illustration of these typologies, each of which map on to Koerner and Fitzpatrick’s (2002) pre-established family communication types leading up the time at which the loans were accrued. The expressed styles of family financial communication before accruing loans were found to be linked most closely to the directness in which participants and their parents discussed student loan repayment.

Typologies of family communication regarding student loans during repayment (Miller, 2019)

Avoiders and Roundabouters: Less Direct Overt Communication with Family About Loan Repayment is Associated with More Benign Effects of Loans on Family Relationships

In focus groups, participants categorized as “Avoiders and Roundabouters” were those who described indirect communication with parents about student loan repayment. The indirect style of communication characteristic of both of these communication typologies situated student loan repayment as a fairly benign factor operating in the background of family relationships.

Avoiders: Indirect and Infrequent Overt Family Communication About Loans

Over twenty-two percent (22.6%, n = 14) of all participants in the sample were coded in the focus groups as having had Avoider family communication patterns with their families while repaying loans. Many participants described how communication about their loans was an extension of more enduring patterns of financial communication with their family system. Therefore, it is perhaps unsurprising that those who described Laissez-faire styles of communication with parents leading up to the time of accruing loans were subsequently considered “Avoiders” during the repayment period. This classification is defined by indirect and infrequent communication with family members about the student loans during repayment. Within this group, 45.2% of participants (n = 28) described a general “lack of direct conversations with family about finances,” including but not limited to the time at which they were repaying the loans.

For instance, Anne, a 48 year old academic administrator who described being “burdened” with a persistent $68,000 in loans for her undergraduate and graduate education, explained “I wasn’t brought up in a family where people talked openly about finances or financial planning. There was a lot of magical thinking about money, and, ‘Oh, it’ll work out. You know, don’t worry. We’ll take care of that.’” Years later, after taking over responsibility for her loan payments after her parents’ financial situations changed after getting divorced, she describes living in a “state of denial” about her loans. Attributing her enduring state of denial to the familiar patterns of indirect and infrequent conversations to which she was accustomed from her family of origin, Anne explained that her own financial socialization as a child and emerging adult has since informed how she approaches conversations about finances and paying for college with her own children.

Like Anne, who described family conversations about finances and loans as indirect and infrequent, another participant, Dave, spoke to similarly opaque conversations he had with his parents, who also have loans on his behalf. A 33 year old academic affairs professional who had taken on $200,000 in graduate loans for himself and still owed $180,000, Dave reported that his parents took on loans for his undergraduate, not graduate, degree. He used the word “inevitable” to describe his student loans. Like 8.1% of all participants with loans for themselves (n = 5), he expressed gratitude for his family’s support. Despite recalling more detailed conversations about paying for college leading up to the time in which he took on loans, Dave still described fairly indirect and infrequent family conversations with his parents during the repayment period. He was part of the 24.2% of participants (n = 15) who reported having “no real need to talk about loans with family.” While participants expressed different reasons for not having a pressing need to speak with their family about loans, Dave’s reasons seemed to stem from his family’s Laissez-faire communication pattern. When asked if he knew that his parents were taking out loans for him to go to college, he responded, “I mean, they told me they would pay for college for me…I don’t know what their total amount that they took out was.” Like others with a similar situation, he went on to clarify that he also did not know what his parents had repaid.

Roundabouters: Indirect and Frequent Overt Family Communication About Loans

Over twenty-two percent (22.6%, n = 14) of all participants in the sample were coded in the focus groups as having had Roundabouter family communication patterns with their families while repaying loans. Circling back to Charles, the engineer whose mother took out loans that he knew he would be repaying from the start, it became clear that his family’s decidedly pluralistic communication style (high conversation orientation and low conformity orientation) before accruing loans had not only persisted, but evolved into a roundabout style of communicating about loans during the repayment period. When asked if and how the loans come up in conversation with his mother now, Charles shrugged as he framed conversations with his mother about loan repayment as part of the more enduring pluralistic pattern of family communication- high in conversation orientation and low in conformity orientation. According to Charles, “She gets notifications [online] when one of them gets paid off, I think. I’ll ask her if I forget what one of the security questions is… But she’ll be like, ‘Oh, good job. I saw you paid the thing off.’ I’m like, ‘Yeah. Thanks, Mom.’ But not in a serious way, because there’s not a concern or an issue or anything.” In Charles’ case, technology largely served as an indirect mediator of communication between him and his mother during repayment, whereby he would not choose to verbally communicate updates about the loans with his mother but she receives automatic updates about the loans online.

To-the-Pointers and Persisters: More Direct Overt Communication with Family About Loan Repayment are Associated with More Negative Effects of Loans on Family Relationships

In focus groups, participants referred to as “To-the-pointers and Persisters” were those who described direct and often negative communication with parents about student loan repayment. These participants framed communication with parents about loan repayment as direct, which both extended the style of communication typically described leading up to taking on the loans (for Protective and Consensual families) and contextualized the higher reports of student loan-related family conflict within these groups.

To-the-Pointers: Direct and Infrequent Family Communication About Loans

Over twenty-two percent (22.6%, n = 14) of all participants in the sample were coded in the focus groups as having had To-the-pointer family communication patterns with their families while repaying loans. “To-the-pointers” described more direct yet fairly infrequent conversations about loan repayment and finances in general with their family of origin. Leading up to the time at which they accrued loans, “To-the-pointers” could be described most often as coming from families with Protective styles of communication, low in conversation and high in conformity. A perfect example is Alice, 28 years old, who had taken on $90,000 in loans for her undergraduate and graduate education and now owed $116,000. She was working as an adjunct professor and referred to her loans as “burdensome.” She began by contextualizing her loans within the fact that her parents did not pay for any of their children’s education, including hers. Like 38.7% of participants with loans for themselves (n = 24), Alice described having siblings who also had or have student loans. Despite having three siblings with student loans (all with balances significantly lower than hers), Alice could not remember a time when she had spoken or consulted with her two older siblings about student loans before she took them on, an experience reported by 22.6% (n = 14) of all participants with loans for themselves. However, when asked how student loans were discussed among her siblings during repayment, she spoke to the boundaried sub-systems notion of family systems theory, explaining that interactions with siblings about student loan repayment were rooted in camaraderie. In Alice’s words, “I mean, with the siblings we’re pretty open…every once in a while it’ll come up where parents will not necessarily understand, and I need to seek support from someone who I can feel like I can say, ‘Hey, you know how screwed I am. I can talk with you about it,’ to which they can sort of share that same thing.”

However, describing enduring patterns of communication with her parents that were primarily Protective (low in conversation orientation and high in conformity orientation), Alice described loan-related interactions with her parents that were adversarial and quite often inflammatory. Alice revealed how, as she has moved deeper into repayment, conversations with her parents about her loans tended to cluster around participating in family events. She explained that when her parents ask her to travel to family events, she responds with, “’I can’t pull $500 out. If I did, it would have gone to my loans this month, to deal with that.’ [My parents] will generally see it as some sort of poor financial planning on my part…some sort of being talked down to about it.” In this way, Alice also demonstrated ways in which conversations about loans arise sporadically and surrounding particular events, yet when they are discussed, they are discussed fairly directly and negatively. Her comments also pointed to the ways in which family communication about loans can directly inform perceived effects of loans within family systems. When asked how the student loans have impacted her relationship with her parents, Alice’s tone became somber. “Incredibly negatively. I mean, I lived at home while I was taking those out and constantly got heat about my financial situation. And then, leaving the house instead was seen as like a financially disastrous move to go be employed somewhere for more money far away from home. Sort of every step of the way has led to them questioning my life decisions more and more knowing that I now have this over my head, in a sense.” In these ways, she was part of the 8.1% of participants (n = 5) who reported feeling judged by their families because of their loans.

Persisters: Direct and Frequent Family Communication About Loans

About one-fourth (25.8%, n = 16) of all participants in the sample were coded in the focus groups as having had Persister family communication patterns with their families while repaying loans. Like “To-the-pointers,” who described fairly negative effects of loan repayment on family relationships, “Persisters,” also described direct communication about loans during the repayment period. In comparison, however, Persisters referred to more frequent conversations with parents about loans during repayment. Incidentally, these participants were most often those who described Consensual styles of family communication (high in both conversation orientation and conformity orientation) leading up to the time at which they took on the loans. When asked if and how student loans are discussed in his family, Brent, a 32 year old part-time teacher who took on $62,000 in loans for graduate school and still owes $61,000, responded, “Every time I talk to my father.” Using the word “resigned” to describe his feelings on the loans, Brent explained that he had borrowed the maximum amount of federal loans available and that his father had borrowed the remainder using a home equity line of credit. The shared expectation between the two of them was that Brent ultimately repay all of the loans that both of them had accrued. According to Brent, “So every time I talk to him, he’s like, ‘Oh, hey, how you doing? Okay. This is where you stand right now [with the loan payments]…’ It was very generous of him, but it’s sort of jokingly brought up every time we talk, because he’s not going to pay it down. I’m going to pay it down through him. He reminds me.” Brent described these conversations as reinforcing an existing power dynamic between the two of them. Acknowledging that these patterns of communication with his father were similar leading up to, and during repayment, Brent explained that the two of them had always discussed finances freely and openly, but that his father always had the last word.

Loan-Related Family Communication During Student Loan Repayment: Mixed Methods Findings

Survey results pointed to ways in which participants felt repaying student loans had manifested within their family relationships, whereas focus group data extended these findings by spotlighting the role of family communication in these relationships. As Table 7 displays, the majority of participants (55.8%) reported in the survey that the loans had not affected their overall relationships with their family, nor had they affected their specific relationships with their mother, father, or sibling(s). However, survey results also showed that if participants reported any effects of the student loans on their overall and/or specific relationships with family members, they had most often imposed negative impacts. Qualitative results help to explain some of these responses.

Despite the fact that over half of participants reported in the survey that the loans had not affected their overall relationships with their family, 42.9% of participants (n = 24) reported in the survey that they had experienced some type of conflict in their family related to the student loans. Qualitative analysis revealed that some of these family relationships manifested in spoken communication patterns, whereas others were not vocalized but quietly affected family relationships nonetheless. For instance, of the participants in the survey who reported experiencing family conflict related to the loans, 33.3% (n = 8) of whom were coded as having Roundabout family communication typologies during the loan repayment period, 25% (n = 6) of whom were coded as having Persister or To-the-pointer typologies, respectively, 12.5% (n = 3) of whom were coded as having Avoider family communication typologies, and 4.2% (n = 1) of whom had uncategorized family communication typologies during the repayment period.

Overall, 25.8% (n = 16) of all participants in the sample were coded in the focus groups as having had Persister family communication typologies during the loan repayment period, 22.6% (n = 14), respectively, of participants were coded with Avoider or Roundabouter communication typologies, 19.4% (n = 12) were coded with Roundabouter communication typologies, and 9.7% (n = 6) were uncategorized. 25–35 year olds most commonly reported having Persister styles of communication (41.9%, n = 13), whereas 36–50 year olds most commonly reported having Roundabouter styles of communication (33.3%, n = 7), and 51–75 year olds most commonly reported having Avoider styles of communication (40%, n = 4). Women were most commonly coded as having Roundabouter (28.6%, n = 10) and To-the-pointer (25.7%, n = 9) styles of family communication during loan repayment, whereas men were most commonly coded as having Avoider (33.3%, n = 9) and Persister (29.6%, n = 8) styles of family communication. Finally, 29.6% (n = 8) of participants who reported in the survey that no one else had helped pay for them to attend college were coded as having Avoider styles of family communication during loan repayment, while 34.3% (n = 12) of participants who did report receiving help paying for college were coded as having Persister styles of family communication during loan repayment.

Discussion

The main goal of this mixed methods study was to understand student loan-related family communication patterns before accrual and during repayment. Building on research pointing to the complexity of financial interactions within families (see Dew et al., 2012), results suggest that, for many student loan borrowers, student loan-related conversations with family members are about more than just money. Results from this study also suggest that family communication about student loans- both before accruing them and during repayment- can be seen as a reflection and extension of family financial socialization processes.

Loan-Related Family Communication Before Accruing Loans

The first research question centered on ways in which family communication patterns manifested before accruing student loans. An important finding is that 66% of borrowers in this study were deemed to have had Laissez-faire styles of family communication in the time leading up to the loans, meaning they had perceived low levels of family conversation about student loans and relatively high autonomy in their decision to take on loans. This suggests that many participants in this particular sample made decisions about accruing loans without considerable consultation or advice from family members.

More specifically, results show that the degree to which families engaged in mutual shared decision making about taking on loans (e.g., who will take them out, who will repay them, what are the most cost-effective loan options, etc.) largely reflected ongoing financial socialization processes within their family, including but not limited to, their family communication patterns (Koerner & Fitzpatrick, 2002). Results suggest that, particularly when borrower’s overall schemata of family communication leaned toward a high conversation orientation, that loan-related family communication pre-accrual was generally more open (Koerner & Fitzpatrick, 2002; Schrodt et al., 2008). Generally, these higher levels of family conversations about taking on loans could be traced a) to enduring patterns of communication with family, not constrained to communication about loans; and/or b) higher incidence of shared borrowing status, meaning parents may have also been carrying and/or repaying loans for participants.

As a result of more shared borrowing status in these families, participants with high conversation orientations were more apt to recall having pragmatic conversations with their parents in which they discussed plans to take on loans as multiple members of a family and perhaps also spoke about division of repayment responsibility. Based on their higher incidence of shared borrowing status, these participants also were more prone to describe conversations in which parents made their willingness to share loan borrowing responsibility conditional based on several factors. These findings align with Thorson and Kranstuber Horstman’s (2014) and Edwards et al.’s (2007) research in a related domain that college students who depend on their parents for social and financial support are more likely to discuss their credit card use with their parents.

On the other hand, participants who described lower conversation orientations tended to describe how they flew solo on the decision to take on loans, most often because they perceived the loans to be their only financing option (particularly if they had sole loan carrying status), considered their parents to be financially illiterate about loans, and/or because they did not want to burden their parents. In line with previous research, first-generation college students were overrepresented within the latter group (Furquim et al., 2017; Lee & Mueller, 2014). For participants with low conversation orientations leading up to the time of accruing loans, decisions about taking on loans were often made by individuals within their family systems, as opposed to decisions made by families as a whole. Thus, unlike previous research suggesting that, when families make decisions that impact the whole family, they approach it as a family unit to gather information, consider the needs and wants of the family members, and evaluate alternatives (Hsiung et al., 2012), findings from this study suggest that, if this process actually takes place leading up to taking on loans, it can happen in more covert, siloed ways for those who do not regularly discuss finances with their family. An alternative explanation presented by Arnett (2000) is that emerging adults may intentionally make fairly autonomous decisions about taking on student loans in an effort to assert their autonomy, a crucial developmental task during this life stage.

Loan-Related Family Communication During Student Loan Repayment

The second research question asked about ways in which borrowers described loan-related family communication patterns during the repayment period. Because participants had moved past the decision-making stage of accruing loans and had since either taken on sole or shared responsibility for repayment, the levers that emerged for communication typologies during repayment had more to do with frequency and directness of family conversations. At the most fundamental level, results extend previous research pointing to finances as a taboo topic of conversation, even within families (Plander, 2013; Romo & Vangelisti, 2011; Trachtman, 1999). More generally, the ways in which student loans were discussed within families can be viewed as extensions of larger family relationships and enduring financial communication patterns within the family.

Emerging from focus group data and theoretical framework are four discrete typologies of family communication regarding loans based on the frequency and directness of communication (Miller, 2019). These typologies are important because, as extensions of family communication norms, they can be viewed as potential predictors of students’ financial literacy and spending and saving behaviors across the life course (Koerner & Fitzpatrick, 2002; Schrodt et al., 2008; Thorson & Kranstuber Horstman, 2014). They build on Koerner and Fitzpatrick’s (2002) pre-established family communication types, demonstrating that conversation and conformity orientations can be relevant during multiple stages of the student loan process, leading up to the time of accrual and through repayment.

Notably, participants who characterized loan-related family communication during repayment as infrequent and indirect were least likely to report negative effects of loans within families, including loan-related conflicts, perhaps due to the indirect nature of communication within their family about the loans. These results echo work of Kim et al. (2011), pointing to potentially negative repercussions of family communication styles that are more typical with families that are low in conversation orientation. Often, participants who described family communication about the loans as minimal-to-nonexistent felt that communication was unnecessary (often the case for borrowers with sole loan-carrying status) and/or uncomfortable. Others described indirect yet more frequent communication about the loans during repayment, sometimes referring to the ways in which technology-mediated communication increasingly serves as a conduit for financial conversations (albeit indirect) between family members. It also illuminates ways in which some families may discuss loans often, but how the conversations may be triangular in nature (between two family members about a third family member, for instance) rather than linear (from one family member directly to another).

Still other participants described loan-related family conversations during the repayment period that were direct and often more negative. For some, the loans did not come up in family conversations often but when they did (often tied to occasions such as holidays, vacations, or other occasions that would include spending, gifting, or otherwise having clustered conversations about finances), they were addressed directly. And for others, the loans were discussed directly and frequently, some matter-of-factly and some with more complex emotions.

More generally, we would suggest that the gap in what was said and left unsaid in families during student loan repayment is captured in the differences in quantitative vs. qualitative results. Participants who reported in the survey that the loans had negatively impacted their relationship with family also made it clear in focus groups that loans had come to the foreground in family relationships, either at various points or persistently during the repayment period. That said, over half of all participants reported in the survey that student loan repayment played a quiet, passive role in family relationships—more specifically, that the loans had not affected their relationship with their family. However, for at least a portion of these participants, focus groups revealed that these dynamics were actually experienced as undercurrents of family relationships, not necessarily said but often felt by the participant.

In this case, the fact that differences emerged in surveys versus focus groups reinforces the notion that the medium through which research participants are asked about finances (or other sensitive topics, for that matter) may influence responses. Drawing on these conflicts in data, compared with quantitative data, qualitative data revealed a depth of emotion many participants experienced related to loans within their family. These differences could have reflected how the semi-structured focus group prompts were framed, a sense of comradery formed through shared discussion, or how the other participants’ comments may have evoked memories, attitudes, and/or perceived bases for comparison about family experiences with loans (Khan et al., 1991; Krueger & Casey, 2000).

A Proposed Model: Linking Loan-Related Family Communication Before Accrual and During Repayment

Figure 3 depicts a proposed model that connects loan-related overt family communication patterns pre-loan accrual with overt family communication patterns during the repayment period. Family communication patterns regarding student loans were expressed leading up to the time of loan accrual in ways that were based on conversation and conformity orientation (Koerner & Fitzpatrick, 2002). In turn, these patterns mapped to a loan-related family conversation typology that was based on frequency and directness of communication about the loans (Miller, 2019).

By linking conversation and conformity orientation in families leading up to loan accrual through family communication patterns theory with directness and frequency of family loan-related communication during repayment, this research extends previous scholarship about family financial socialization and, more specifically, family communication about finances (Gudmunson & Danes, 2011; Koerner & Fitzpatrick, 2002; Moschis, 1985).

Combined, these insights about family communication dynamics and decision making may ultimately have implications for family financial conversations in other important domains as well, including related to legacy/estate planning and financial caregiving. In fact, family communication patterns related to student loans may be previews for what is to come as borrowers and their families move through the life course.

Implications

From this study, implications emerge for a variety of stakeholders, including student loan borrowers, professionals and organizations working in the fields of behavioral health and financial planning and counseling, as well as researchers. Overall, this study points to the enduring taboo of financial conversations within families- in this case, specifically about student loans before accrual and during repayment. Previous financial socialization research argues that the general lack of financial conversations within family systems and the enduring taboo of talking about money partially explain why many do not develop financial literacy at home (Lusardi et al,, 2014; PwC and GFLEC 2015). In turn, research has shown how low financial literacy can be detrimental for borrowers’ financial wellbeing before they take out the loan (e.g., understanding terms of loans, interest rates) and after they start repaying it (e.g., understanding the impact of late payments on credit) (Fan & Chatterjee, 2019; Lusardi et al., 2014). We would suggest that these issues are perhaps most urgent for first-generation college students, many of whom described Laissez-faire styles of family communication before accruing loans, with minimal communication with, or guidance, from parents about taking on debt. Anticipating that increased financial literacy may improve overall family financial communication, we would argue that financial literacy training (including for parents) must be considered a priority in private, non-profit, and public sectors, including in business, educational, clinical/therapeutic, and employment contexts.

The same family communication norms that influence students’ experiences accruing and repaying loans can endure over time and influence subsequent communication with family members about other important topics, including caregiving, end of life planning, and providing financial support to children (Koerner & Fitzpatrick, 2002; Lai, 2012; Schrodt et al., 2008; Silverstein et al., 2002). Thus, this research also calls on financial professionals working in a variety of settings to expand their services beyond financial training and management in order to encompass some degree of counseling. Social workers or other clinicians working in the realm of family therapy, financial therapy, employee assistance programs and other programs within human resources departments can embed psychoeducational groups and/or other resources for employees with student loans into their work settings to help borrowers navigate complex family financial communication patterns and borrow and repay more effectively and efficiently (Allen et al., 2013). At the same time, it is vitally important that financial professionals become more literate, themselves, about student loan borrowing so that they can provide the soundest advice for clients about involving family members in conversations about student loans when appropriate.