Until the mid-1990s, discussion of the press and propaganda in First World War Britain was generally characterized by deep suspicion. Gerard DeGroot's caustic account of government relations with the press suggested a ‘paranoid government feared that spies lurked in every corner ready to exploit careless leaks’ and ‘failed abysmally to manage the news’; while the press ‘willingly cooperated in the collective effort to pull the wool over the public's eyes’, and was ‘kept sweet’ through public roles. ‘The Harlot of Fleet Street’, he concluded, ‘sold herself cheaply.’Footnote 1 DeGroot's was a late example of serious scholars’ attempts to portray Britain's wartime management of information as, simultaneously, inept and ineffective, yet corrupt and sinister. Such accounts, commencing in the 1920s and dominating discussion through the twentieth century, invited readers both to scoff at crass attempts to manipulate public opinion and to shudder at the malign intentions these attempts embodied.Footnote 2 The public's deception explained its continued consent to a pointless war.Footnote 3

However, such broad generalizations have been increasingly challenged. Assumptions about atrocity stories’ crudity and dishonesty, for instance, have been problematized by evidence that substantial atrocities occurred;Footnote 4 that the ‘sensationalist’ press spent more space on destruction of property;Footnote 5 and that propagandists’ use of atrocity stories served more complex purposes, whether humanizing Britain's legal case for war, or contextualizing the need for wartime service as part of a wider patriotic narrative.Footnote 6 Where scholars look in greater depth at a particular aspect of the whole, they generally reveal more complexity,Footnote 7 and often more sophistication, than previously suggested.

Press censorship has only partly received such close scrutiny. The only extended study of the ‘D’ notice system administered by the Press Bureau, instructing editors about what was or was not publishable, focuses mainly on the Bureau's relations with the press, rather than the notices’ content.Footnote 8 Nicholas Wilkinson's official history includes a lengthy appendix in which he assigns notices into one of fourteen categories, but only covers 284 notices (a little over one third of the total), suggesting many of the rest cancelled, amended, or repeated previous instructions. While the analysis below suggests the quantitative pre-eminence of security-related instructions, Wilkinson's appendix gives greatest prominence to ‘Political/Foreign/Industrial Relations’, of which he gives more examples than those referring to the three armed forces branches combined.Footnote 9 This serves Wilkinson's purpose of highlighting the range of issues addressed but is problematic for understanding the notices’ overall thrust. Discounting repetitive content (such as individual, but similar, security-motivated instructions not to publish details of military movements, or the movement of prominent figures) skews the overall picture of the notices’ content. Further, his somewhat undifferentiated ‘relations’ category elides quite distinct concerns. The desire not to antagonize a neutral nation through press commentary, for instance, and to avoid commentary on domestic industrial disputes, served different purposes. Wilkinson is much more interested in government relations with the press than with the notices themselves. Tania Rose, meanwhile, confirms that D notices were ‘overwhelmingly concerned with legitimate security matters’ such as military and naval matters and the movements of prominent people, partly anticipating this article's assessment. Rose stresses other forms of formal and informal Bureau censorship, such as secret letters sent to select trusted editors, the potential withdrawal of such privileges, and practices such as telephoning additional information around notices, importantly demonstrating that D notices did not govern press conduct alone. Like Wilkinson, however, she does not fully assess D notice content. Her discussion acknowledges, but makes little effort to assess or differentiate, security-oriented notices, instead suggesting that only 16 and 15 of 747 notices covering, respectively, Russia and strikes, showed a ‘significant subject concentration’.Footnote 10 The more substantial content analysis below complements these accounts, sharpening the picture of what content the Bureau sought to moderate.

Other accounts offer relatively brief, general assessments of the Bureau's work, suggesting it functioned as part of wider official propaganda activities but offering only impressionistic analyses of individual notices. Deian Hopkin's article about domestic censorship, arguing that, despite stepping up interference with ‘pacifist’ publications from 1917, British censorship did not fundamentally intrude on the freedom of the press, spends little time on D notice content.Footnote 11 M. L. Sanders and Philip M. Taylor's classic discussion of British propaganda suggests ‘the press became the servant of official propaganda more out of willing acquiescence than…official coercion’, often governed by patriotic motives, but that, nonetheless, editors retained substantial freedom to use and discuss official information as they saw fit, and pushed back against undue attempts to impose content. Such claims are largely confirmed below but, again, accentuated by much more thorough consideration of the notices. Eberhard Demm's recent comparative study of censorship and propaganda addresses censorship primarily in a single chapter, suggesting Britain's methods were more lenient than other nations’ and developed ‘in informal discussions and social contact with newspaper editors’. Again, Demm pays little attention to the notices themselves, besides briefly suggesting extensive restrictions on discussion of industrial action.Footnote 12 Such a characterization is hard to square with close examination of the notices’ content. This article, therefore, provides a more holistic examination of official efforts to control wartime press content through D notices. It briefly outlines the D notice system, before providing quantitative and qualitative analysis of the notices and the themes addressed by them, considering individual examples at greater length. This evidence suggests notices primarily sought to prevent potentially useful knowledge reaching enemy sources. C. E. Montague (a noted critic of the wartime press) pointed out that, theoretically, such restrictions were limitless, since ‘all information about either side is of military value to the other’,Footnote 13 and Wilkinson has shown that editors certainly chafed at what they considered unreasonable restrictions on public knowledge or attempts to suppress things already known.Footnote 14 The Bureau did not, however, generally try to stifle criticism or dissent through D notices – notices only rarely sought to suppress journalistic opinion, though they did occasionally attempt to obscure public dissent, as discussed below. Meanwhile, efforts to modify newspapers’ tone or opinions, or to encourage more attention to topics that government departments wished discussed, proved less palatable to an otherwise helpful press. Taken as a whole, the article shows that D notices’ major function was to prevent unnecessary risks to prominent individuals or to military or naval planning or personnel, and not to promote a false account of the war's progress. Neither the Bureau, nor the press, generally saw the notices as unduly intruding on press freedom or obstructing public knowledge, and where undue restrictions appeared, the press quickly protested to an apparently responsive Bureau. This close examination of D notice content, therefore, adds further weight to the revision of ideas about official and media representations of the war.

I

The Press Bureau was announced by Winston Churchill, first lord of the Admiralty, on 7 August 1914,Footnote 15 and established in the following days. Editors were informed by the Admiralty, War Office, and Press Committee's (AWOPC) secretary, Edmund Robbins, on 8 August. The Bureau's original purpose was made clear in this letter, which informed editors that:

the names of ships…should not be reported; nor…(a) Movements of Ships, Troops, Aircraft, or War Material; (b) Fortifications, Defence Works, Arsenals, Dockyards, Oil Depots, Ammunition Stores, and Electric Light Installations, without first obtaining the sanction of the Admiralty or War Office respectively. In fact no information should be given bearing on naval or military movements, as such information – however remote it might appear to be – would probably be of advantage to the enemy, and, therefore, prejudicial to national interests.Footnote 16

The letter reflected ongoing efforts to protect sensitive military and naval information, developed since the Second Boer War. The AWOPC emerged in 1913 as an attempt to resolve frictions between the press and the armed forces by providing more opportunity for regular communication and co-operation.Footnote 17 While the AWOPC continued during the war as an additional conduit, the Bureau became the official arbiter of permissible news. Initially led by the Conservative lawyer and MP, F. E. Smith, then the Liberal lawyer and MP, Stanley Buckmaster, after May 1915 it was run by the journalist, Edward Cook, and the colonial administrator, Sir Frank Swettenham, while other journalists were appointed to help advise the 300 censors of the expanded Bureau, smoothing out initial concerns that censorship decisions were made without regard for newspapers’ needs.Footnote 18 The Bureau's relations with the press were enhanced by the AWOPC's continuation and ongoing contact with the Newspaper Proprietors’ Association (NPA), usually represented by the News of the World's editor, Sir George Riddell, a political insider closely connected with David Lloyd George (successively, wartime chancellor of the exchequer, minister of munitions, secretary for war, and prime minister).Footnote 19 As the war developed, so did the Bureau's relationship with the press, with the result that (as discussed below), while editors sometimes directly challenged the Bureau, they also sometimes sought to aid its task, or sought its help in adjusting departmental obstructiveness. Far from a one-directional imposition on press freedom, therefore, through personal connections between its directors and leading journalists, the Bureau mediated between departments and the press.Footnote 20

While the Bureau finalized and issued 747 D notices between August 1914 and March 1919 (eventually to over 2,100 editors nationwide),Footnote 21 it did so at government departments’ request, particularly those representing the armed forces. Of those notices identifying a specific departmental source, 63 per cent came from the Admiralty or War Office. The next most frequently stated department, the Ministry of Munitions, accounted for less than 8 per cent.Footnote 22 Cook noted that all departments could request notices, and were expected to disseminate (rather than withhold) information via the Bureau's B and C notices from November 1914,Footnote 23 but the preponderance of explicitly naval and military D notices hints at the primary security emphasis underlying the system. Cook partially explained this in his post-war assessment of the Bureau's work, which emphasized the scope and limits of Britain's censorship provisions. Since it was recognized that the ‘whole idea of censorship is repugnant to a democracy accustomed to a completely free Press’, the Bureau was not empowered or expected to restrict press commentary simply for departmental convenience. Generally speaking, he claimed, the ‘rule which the Directors…laid down for themselves was, contrary to some suppositions on the subject, to interfere as little as possible with military criticism and not at all with political criticism’.Footnote 24 The Bureau sometimes issued requests to avoid material on diplomatic matters that might be ‘provocative’ to neutrals, but, after December 1915, it was instructed not to censor discussion of foreign affairs as too much restraint might indicate the press was beholden to official views.Footnote 25

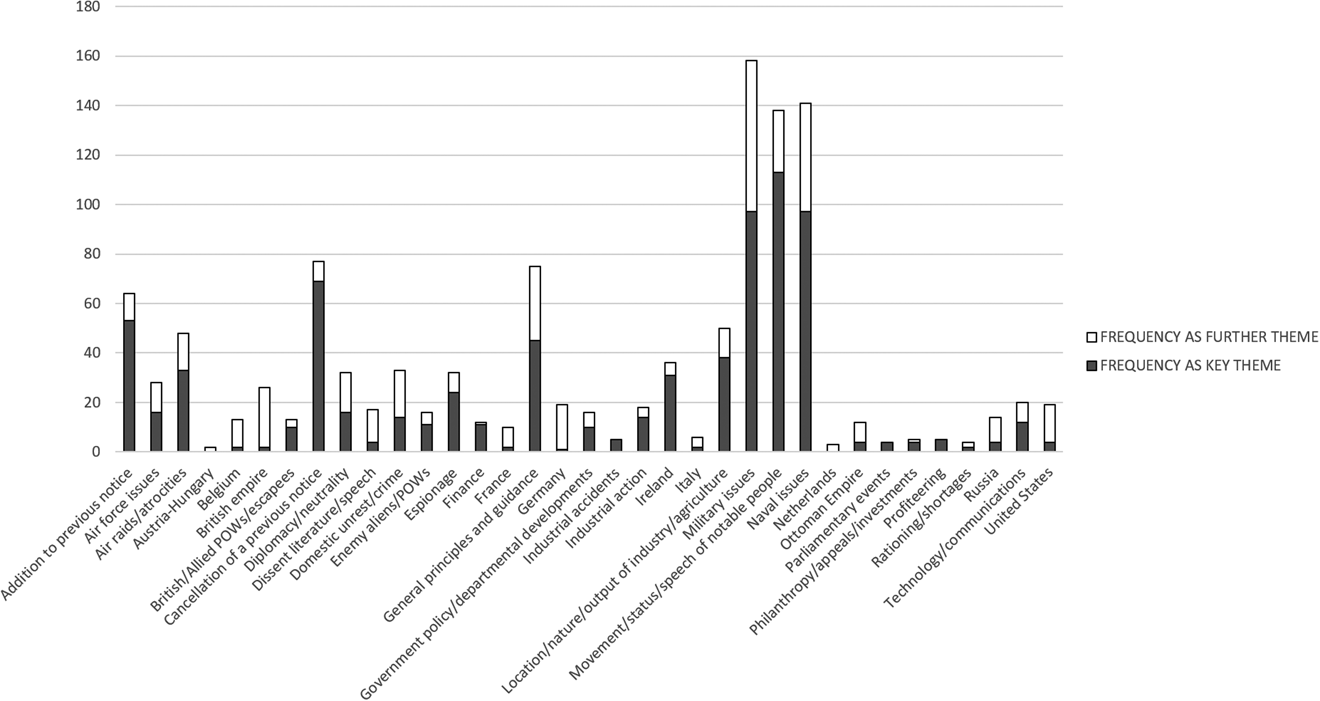

Cook's defence of the Bureau may seem excessively complimentary. A minority of notices, discussed in detail below, can be found that restricted discussion of contentious events. For a time, the Bureau published a small number of notices intended to obscure industrial dissent. On very few occasions, political dissent within England, Scotland, and Wales was targeted, while the Bureau applied less strict principles of press freedom when limiting discussion of Ireland after the 1916 Easter Rising. Regarding all these issues, editors pushed back firmly, sometimes obtaining concessions from the Bureau or the relevant department. However, quantitative and qualitative analysis shows that these instances, while noteworthy, comprise a small portion of the total content of the D notices issued. A database, constructed from Home Office files of the draft notices, assigns each notice a single ‘key theme’ and (if more than one theme was evident) further themes. This analysis makes clear that the instructions’ purpose was substantially security-oriented, while notices that did not address a specific security risk were often banal regulations, cancelling, extending, or consolidating more specific notices into enduring guiding principles for editors. Avoiding criticism or seeking to distort military or domestic realities was, therefore, a rare exception to a more general, cautious rule that sought to avoid inadvertently providing information damaging to Britain's war effort. Of 759 key themes assigned to the D and separately coded ‘Ireland D’ notices (from 35 alternatives, allowing for more differentiated thematic analysis than Wilkinson's previous categories), the three most common categories related, first, to the movements, statuses, or speeches of ‘notable people’ – mostly royalty, ministers, senior armed forces personnel or foreign dignitaries – which featured in 113 notices; and equal second to military or naval issues (97 each). This comprises over 40 per cent of the total in these heavily security-oriented categories, though, if the next two largest ‘themes’ – the cancellation of or addition to a previous notice – are excluded, the percentage rises to over 48 per cent (beyond this core, many notices tied to smaller key themes also carried a security focus, as outlined below). When further themes are added (Figure 1), military issues become most common, followed by naval issues and movements of notable people. Few dramatic differences occur when further themes are added, except that ‘general principles and guidance’ becomes more prominent. This category indicates the notice provided a broad discussion of censorship principles, rather than restricting one specific piece of information. Practically, such notices often consolidated several instructions into one. It also served as a last resort for instructions that did not fit directly into other categories, such as four notices issued regarding the prohibition on discussing the weather – a particularly severe assault on British public discussion!Footnote 26

Figure 1. Frequency of key themes and further themes.

Notices relating to the activities of prominent figures usually had a security purpose in avoiding making either the person concerned (for instance, when travelling by sea) or the place visited (for instance, the inspection of a munitions factory at a particular place) a target. Requests not to publish aspects of speeches also usually sought to avoid revealing sensitive information. Some notices were, doubtless, excessively cautious, but understandable in the context of a war in which new innovations such as aerial bombardment and submarines created greater potential risks and anxieties. However, some notices were also issued more for individual convenience than real security concern. For instance, D700, issued 16 August 1918, asked the press not to disclose a trip the prime minister, David Lloyd George, was taking to his home in Criccieth ‘as he desires to be as quiet as possible’.Footnote 27 Such a minor request was unlikely to alarm editors who routinely kept more intimate secrets as matters of personal rather than public interest. Nonetheless, making such trivia the subject of a D notice prevents any claim that all notices addressed urgent security needs. In total, twenty-six notices (around 23 per cent) regarding notable figures had questionable necessity.

While notices could be issued for reasons other than security, nonetheless security concerns were comfortably the most prominent motivation. For instance, most of the thirty-three ‘air raid/atrocity’ notices related to air raids (two addressed ‘atrocities’), revolving largely around avoiding reporting raids’ impact, the destruction of enemy aircraft or measures taken within Britain to counteract them. Such requests had obvious security benefits in depriving Germany of detailed evidence of their raids’ success or failure. Press coverage of air raids continued throughout the war, and the Bureau issued several reminders and updates, repeatedly stressing the desire to prevent information reaching the enemy as well, more debatably, as suggesting that reporting damage and casualties was a ‘direct encouragement’ of future raids.Footnote 28 In its final notice on air raids, in October 1917, the Bureau stressed that:

The reason why it is not permitted to mention the exact localities where bombs have been dropped by enemy aeroplanes at night, is that an aviator flying by moonlight at a height of over 10,000 feet under heavy gunfire must always be in some doubt as to his exact whereabouts…[especially] when a raid is made…on a dark night, in an area where neither searchlights nor anti-aircraft guns are used.

The German communiques concerning night raids have contained so many inaccuracies that it is evident that the raiders are unable to recognize with any degree of certainty, the towns of England.Footnote 29

While hindering public knowledge of events within Britain, therefore, the restrictions erred on the side of caution in these cases. Newspapers faced a difficult challenge in trying to cover an issue of obvious public interest without compromising such strictures. Over time, officials sought to help by providing official reports from which journalists could draw, but papers continued to exceed their instructions.Footnote 30

Notices in this category that did not cite the prevention of useful information for the enemy included two concerning atrocity stories; one asking newspapers not to report a bomb dropped on Dutch territory by a British plane; two advising editors not to publish advertisements for dubious fire retardants; two notifying newspapers that official photographs of bomb damage were available; and one thanking editors for their previous discretion about a raid. Finally, D597 in late 1917 suggested that public alarm had been caused by reporting anxious crowds sheltering in Underground stations and asked journalists to avoid worsening people's fears through such reports.Footnote 31 Of these notices, the desire to downplay the bomb allegation and crowding in the Underground are, arguably, censurable for withholding information of public interest. The latter notice stifled discussion of a public safety issue, justifying this by asserting that public morale might suffer. The remainder, however, reveal less the hidden manipulation of the state than over-enthusiasm for circulating notices. The ‘thank you’ note, in particular, issued as a formal notice, was more likely to irritate than gratify busy editors.

Other themes in which most instructions related to security included ‘Air force issues’, ‘Espionage’ (largely censoring trials of suspected spies), and ‘Technology/communications’. The weather restrictions mentioned above, though seemingly trivial, were justified as providing potentially helpful information to the enemy. Cook cited a post-war Manchester Guardian article in defence of this, which noted that a major German air raid had failed because of inaccurate wind calculations.Footnote 32 Of twelve notices related to technology, nine involved protecting valuable wartime secrets regarding carrier pigeons; armoured cars; land, sea, or air ‘fighting machines’; medical technology; tracer bullets; dazzle paint for ships; a transatlantic cable; range-finding and wireless telegraphy. The remaining three sought discretion about the discovery of forged banknotes; regarding a revelation about cables that would ‘embarrass’ Britain and the US, and asked newspapers not to discuss delays to rail, telegraphic, and postal services caused by a blizzard, on the grounds that this might be ‘of great use to the enemy’.Footnote 33 Presumably, the assumption was that such information would permit predictions that snowy weather would undermine normal activities and offer opportunities.

Cook acknowledged some instructions may have been excessively cautious, but stated he preferred this to risking servicemen's lives, and that, since intelligence gathering was like a ‘jigsaw puzzle’, even very small pieces of information mattered.Footnote 34 His claim that the Bureau did not censor military criticism is borne out by detailed examination of notices focused on military or naval issues. None sought to prevent newspapers commenting on the merits or otherwise of particular campaigns or commanders, and notable press controversies, including the 1915 ‘shells scandal’, which criticized the government for providing inadequate and insufficient munitions to the army, or the 1918 Maurice affair, in which the War Cabinet was accused of providing misleading information about British military forces,Footnote 35 were not subject to any Bureau restrictions. This reflected the realization that most newspapers and journalists – particularly accredited war correspondents – undertook ‘voluntary self-censorship’ in return for access. The correspondents gave ‘vivid accounts of the fighting experiences…but always holding out hope of victory and without criticism of the higher commanders’.Footnote 36 Confident in the press's general willingness to maintain patriotic standards, the Bureau did not need to instruct editors about military coverage. Hence, when they sought silence on particular operations, this was either to prevent advance speculation or to avoid revealing useful information, such as how the evacuation of Gallipoli was achieved.Footnote 37 Likewise, most restrictions on reporting naval incidents or discussing submarines aimed to prevent definite information reaching Germany about the effects or losses of its ships.

One of the most notorious notices, D109, received ridicule for instructing editors, in December 1914, not to report the loss of the battleship Audacious in October, even though this was witnessed by a US ship, which rescued the crew, and reported in the US.Footnote 38 Both Cook and the wartime intelligence officer and propagandist, Sir George Aston, noted that this instruction was issued because conflicting reports that the ship was either sunk or towed to Belfast might confuse Germany while the British fleet was temporarily reduced to near parity with German ships. Riddell, an important press liaison with (and challenger of) the Bureau via the NPA, seemingly accepted the deception's reasonableness in retrospect.Footnote 39 Nonetheless, Aston considered it one of only two examples of ‘deceptive British propaganda’ (alongside the notorious corpse conversion factory story). He considered it regrettable, longer term, because it ‘shook the confidence of the British public and of foreign nations in the bona fides of British announcements’.Footnote 40 Concerns about US opinion, in particular, remained prominent throughout the war, as discussed further below. Besides such concerns, editors may also not have welcomed the concluding reference to ‘the duty of loyal subjects and friends of the country’ to obey the instruction.

While most notices were concerned with security – and did not stifle opinion about the war's prosecution, provided it did not reveal sensitive information – some censored material based, apparently, on social, cultural, or political considerations rather than genuine security risks. For instance, D225, issued June 1915, insisted:

It is very desirable that no pictures of European nurses attending our wounded native soldiers should be published in the Press.

The…War Office point out that such pictures have a bad effect on discipline. The Press are therefore requested not to give publicity to pictures of French or British native troops attended by European nurses.

The notice, based on a letter on behalf of the director of military operations, Major-General Charles Callwell,Footnote 41 supplied a discipline motivation to justify distaste for racial mixing, presumably prompted by a Daily Mail photograph of a white nurse attending an Indian soldier.Footnote 42 Two notices in 1919 (while the Bureau continued operating, against Cook and Swettenham's suggestions),Footnote 43 meanwhile, sought to suppress discussion of demobilization and protests for reasons that appeared more to do with military convenience than real threats to national interests. One notice suggested that reporting soldiers’ refusal to re-embark for France might unsettle other soldiers, whose leave provisions might be affected.Footnote 44 Another stressed that a dispute involving the Royal Army Service Corps had been ongoing for some time and ‘has no bearing on the general strike movement in this country’:

At the same time statements of this kind appearing at this moment can do nothing but harm to the public interest by fomenting the general strike situation which is already sufficiently serious.

Newspaper Editors will therefore be rendering a considerable service to the Government if they will instruct their staffs not to insert statements of the kind…[and] emphasise the need for exercising special discretion.Footnote 45

In this example, seemingly issued at Churchill's behest (as war secretary), the usual commitment to avoiding military or political controversy was not applied. It did, however, fall within the boundaries Home Secretary Herbert Samuel stated in 1917, which permitted commentary ‘which could be regarded as unpatriotic’ but denied permission to ‘foment strikes or disaffection’, and which Cook suggested the Bureau followed thereafter.Footnote 46

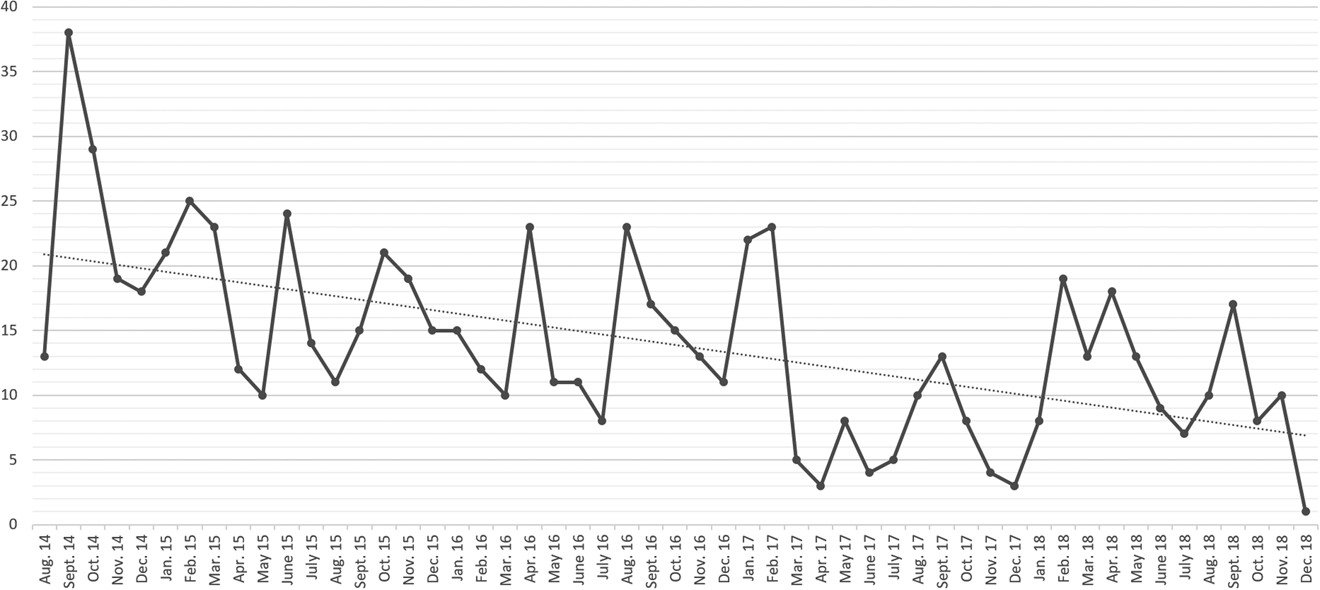

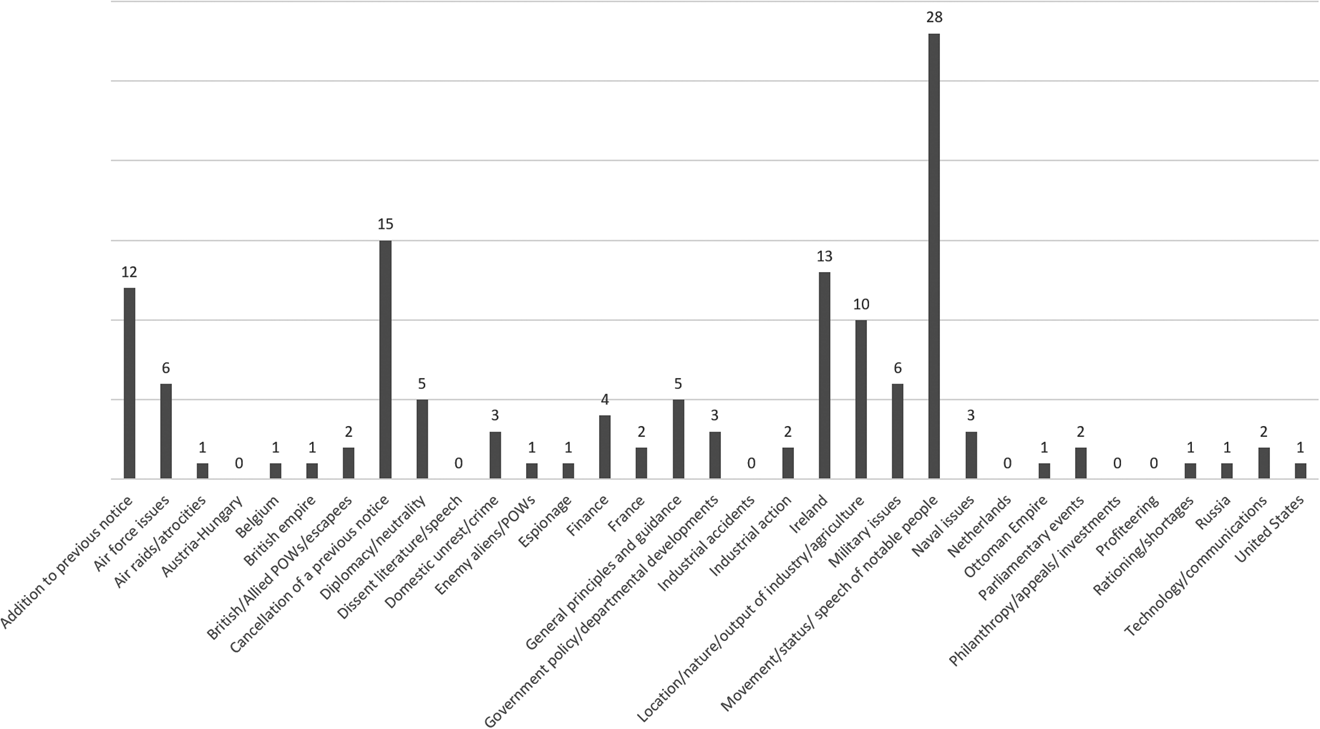

Nonetheless, this was one of relatively few notices that tried to obscure dissent or industrial disruption. Despite increasing official concern about public resolve to support the war, particularly among industrial workers,Footnote 47 the Bureau issued progressively fewer notices as the war continued (Figure 2). This is unsurprising if it is accepted that the notices’ key purpose was to restrict security-sensitive information, as serious issues steadily became subject to permanent restrictions. With finite sensitive security matters, there were fewer notices, with new ones only needed to address specific new developments. As early as November 1914, a Bureau official, R. P. Hills, argued it should ‘rely so far as possible upon general rules and…dispense with the necessity for the issue of a special “D” Notice on any particular occasion’ since ‘the more there are, the more complicated and obscure the situation often becomes’.Footnote 48 This did not prevent repetitious instructions – as noted, several similar instructions on permissible discussion of air raids were issued because of newspapers’ continuing failure to observe sufficient caution – but progressively fewer notices were issued over time. By 1917, the rate of instructions dropped to an average nine per month, from twenty-four in the last few months of 1914. This picked up a little again in 1918, but the small number of military and naval notices suggests these matters were settled (Figure 3). The most frequent theme related to the activities of notable people, which needed a new notice for each sensitive event. Other substantial topics were cancellations, additions, and the location of facilities. No instructions were issued regarding dissenting literature or speeches, while two notices regarding industrial action involved a request not to publicize an ‘ex parte statement’ by the Alliance Aircraft Company during negotiations with aircraft workers,Footnote 49 and a request not to reprint an official statement about the ongoing police strike in September 1918.Footnote 50 This latter instruction neither prohibited nor inhibited reporting of the strike itself – The Times, for instance, published a major article and editorial on 31 August, another editorial on 2 September, articles on 6 and 20 September, and a letter to the editor on 10 September.Footnote 51

Figure 2. Notices issued per month.

Figure 3. 1918 key theme frequency.

II

Quantitative and qualitative analysis shows that D notices’ largest concern was security. Relying to a significant extent on editors’ ‘patriotic’ collaboration, the Bureau focused mainly on restricting potentially dangerous information from reaching Germany. This should not suggest the Bureau only intervened for direct security purposes, however, and the restraint evident by 1918, despite serious industrial unrest early in that year, showed evolution from earlier temptations to restrict commentary. Before Samuel's intervention, the Bureau issued four notices in 1915 seeking to suppress dissenting voices. Yet, even during this year, the Bureau's reluctance to intrude excessively on dissent was shown. In July, editors were asked not to provide ‘the hospitality of their columns and the publicity which attaches to a large circulation’ to the anti-war activist C. H. Norman, a member of the Independent Labour Party, Stop the War Committee, and No-Conscription Fellowship, who sought to publish an article entitled ‘Why the war should be stopped’:

The Directors of the Press Bureau feel sure that it is only necessary to put the press on their guard…A perusal of the article…is enough to convince any patriotic reader that publication…could only embarrass the Government, cause anxiety to our Allies, satisfaction to our enemies and danger to the national cause.Footnote 52

While not forbidding publication, this notice made clear that Norman's views were unwelcome, and that ‘patriotic’ editors would take no interest. In September, the Bureau reminded the press, particularly in South Wales, of Defence of the Realm regulations regarding the incitement of strikes and urged them to avoid giving publicity to strike leaders ‘in the public interest and for their own protection’. In October, editors were requested not to review the US socialist William E. Walling's The socialists and the war, which collected pre-war and wartime socialist comments from various nations. Finally, a fourth notice in October asked for no publicity for a man, previously employed confidentially, who held a grudge and threatened to reveal secret information.Footnote 53 That some editors sympathized with anti-pacifist attitudes is shown by Riddell's correspondence with the directors in October, in which he forwarded a letter sympathetic to pacifists in the Glasgow Evening Times, publication of which he considered a ‘scandal’, before criticizing the Bureau for paying inadequate attention to provincial papers and those aimed at workers. Replying, Cook asked Riddell to indicate a list of such papers, but concluded that Riddell ‘seems to be concerned with the publication of opinions, rather than of information useful to the enemy’, and that much larger governmental powers would be required to ‘suppress the former’.Footnote 54 In this discussion, which Riddell stressed represented his personal view rather than the NPA's, Cook showed more reluctance than Riddell to interfere with dissent.

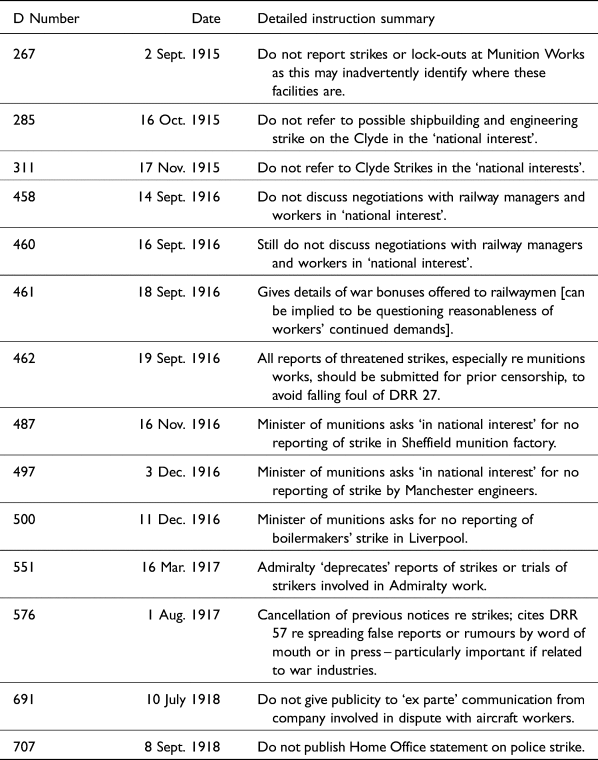

Demm suggests ‘coverage of strikes and other labour disturbances were rigorously regulated by numerous D-notes [sic]’.Footnote 55 However, this assertion is supported by neither the very few notices on this subject, nor the press's critique of those issued. While a handful of specific strikes were the subject of notices over four years, there were only limited attempts to obscure industrial discontent. Most questionably, in response to the ‘major wave’ of engineering strikes in May 1917,Footnote 56 the Bureau asked editors ‘to exercise great restraint…and to avoid encouraging a stoppage of work on an extended scale by inviting public attention to the proceedings of those who are always ready to strike’.Footnote 57 The condescending attitude towards the engineers, depicted almost as children acting up for attention, suggests that the Bureau assumed editors shared the same dim opinion of industrial action. Like the request to avoid publishing Norman's views, it suggests the Bureau was confident most editors were sympathetic, rather than hostile. In fact, as noted below, on this occasion this assumption proved false.

Other restrictions on discussing industrial action (Table 1), spread throughout 1915–18, include ten instructions not to discuss strikes or negotiations between workers and employers, particularly relating to areas of plausible military significance – munition works, shipbuilding and engineering, railways and boilermakers. Hence, most instructions were issued in the ‘national interest’, though it is certainly arguable that the security risk in revealing a potential loss of industrial output went alongside a wider concern to portray a harmonious war effort. An eleventh notice, in September 1916, revealed the war bonuses offered to railway workers, seemingly to inspire commentary against further negotiation. It can, thus, again be seen as an official attempt to undermine industrial action.

Table 1. Industrial action notice summaries

The Bureau's notices regarding industrial matters were certainly not entirely disinterested statements of security necessities, but they were also far from constantly repeated. These few notices addressed a few specific incidences of wartime dissent. Unlike the regular new notices issued regarding the movements of notable people, there was no sense that every example of industrial unrest required a notice. Moreover, sketchy requests were not accepted uncritically. Editors objected strongly to the May 1917 restriction, sending a resolution to the minister of munitions, Christopher Addison, that limiting discussion of industrial disputes was ‘inimical to the public interest and calculated to accentuate…unrest’ rather than reduce it.Footnote 58 Eventually, perhaps in belated response, D576, issued in August 1917, cancelled previous restrictions on strike reporting, reiterated Defence of the Realm regulations, and urged editors’ caution in judging whether to discuss future incidents:

it is necessary to point out the very prejudicial effect which strikes in Shipbuilding, ship repairing and Engineering Yards and shops, Docks, mines, and munition works, or amongst any body of workers engaged in industries vital to the prosecution of the war, must have upon the success of British and Allied arms on sea and land. The Press are, therefore, urged in the public interest to refrain from publishing anything which would tend to bring about or prolong a strike or lock-out.Footnote 59

The official view by the summer of 1917 was thus that strikes in war industries were a bad thing, not to be encouraged by excessive coverage. Thereafter, however, despite the substantial growth of industrial discontent in the winter of 1917/18 and governmental concern about disruption, and even the supposed spread of ‘Bolshevism’,Footnote 60 no further instructions on this theme were issued until late 1918. While this partly reflects growing domestic propaganda, including specific targeting of industrial communities, following the launch of the National War Aims Committee (NWAC) in the summer of 1917,Footnote 61 the apparent decision to stop prohibiting discussion of industrial disputes suggests the Bureau was not interested in conveying a fantasy of uninterrupted domestic bliss. Its general position was clear, and editors could decide whether to accept it. When the chief labour adviser at the Ministry of Munitions, Thomas Munro, suggested in early 1918 that the Bureau advise newspapers that in commenting on strikes they should advocate workers’ acceptance of arbitration, Cook replied – notwithstanding some previous value judgements in the notices – that such a suggestion ‘seems to us to be in the nature of a hint to editors as to how they should write up a subject, and, as such, to be rather outside the scope of our prohibitive instructions’.Footnote 62 Once again, this suggests the Bureau made genuine efforts to balance the necessity for silence on some issues with limiting intrusions on editorial freedom. Philip Snowden, while condemning official ‘vindictiveness’ in pursuing and imprisoning critics like E. D. Morel and Bertrand Russell in 1917–18, nonetheless asserted that the Bureau largely followed Samuel's direction ‘that there should be no unnecessary interference with the expression of opinions’.Footnote 63

III

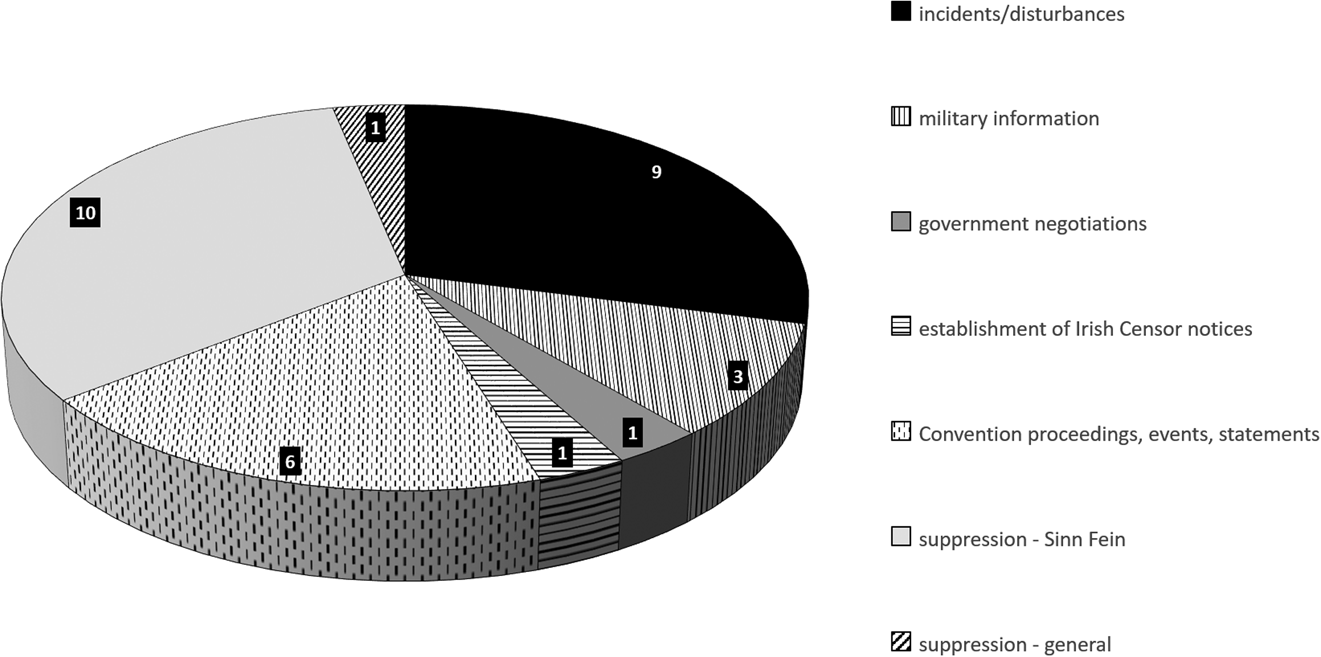

As in so many other respects, Ireland was treated somewhat as a separate entity by the Bureau. Clearly, rules against restricting dissent were loosened with regard to Ireland, usually at the Irish authorities’ request. Critical voices were tolerable and publishable in Britain, whether (as Snowden or Cook, from different viewpoints, suggested) because free speech was ‘ingrained in our British people’, or, as Millman suggests, because this masked less formal coercion.Footnote 64 While limited peace advocacy, criticism of ‘secret diplomacy’, and even mockery of censorship was possible in British newspapers, critical Irish nationalists, in the aftermath of an armed insurrection, were a different matter. Fourteen standard D notices were issued regarding Ireland from 1916 to 1919, commencing after the Easter Rising. However, from early 1917, twenty separate ‘Ireland D’ notices were issued at the Irish Censor's request, to prevent British newspapers printing information restricted in Ireland.Footnote 65 Of thirty-one Irish-focused notices in the Home Office files, nine restricted reports of incidents or disturbances; three limited military information; six insisted newspapers should not report the proceedings or other activities within the Irish Convention, on the claim that discussions could only proceed freely with confidence that they would not be reported; and ten, between 1917 and 1919, tried to suppress reports of Sinn Féin activities (Figure 4). All but two of the last were issued by the Irish Censor, the only exceptions occurring in January 1917, when editors were asked to submit any ‘letters or speeches’ made in the USA by Hanna Sheehy Skeffington – the political activist and widow of Francis Sheehy Skeffington, unjustly executed after the Easter Rising – and in May 1918 when the Bureau asked that evidence connecting Sinn Féin with Germany should not be linked to the USA.Footnote 66 Both notices, issued long after US entry into the war, suggest ongoing concerns about damage to US opinion of Britain through sympathy for Irish nationalism.Footnote 67 D508, issued in December 1916, informed the press that the Bureau would occasionally convey urgent instructions made in Ireland to the Irish press to English and Scottish newspapers, appealing to editors’ sense of fellowship by suggesting that the restriction would prevent Irish papers from being ‘placed at a disadvantage’.Footnote 68 Despite newspaper competition, correspondence with the NPA suggests that such appeals may have carried weight. In September 1916, for instance, Riddell forwarded a resolution asking the Bureau to consider releasing material for high-circulating Sunday papers, rather than withholding announcements until Mondays.Footnote 69

Figure 4. Ireland sub-categories' frequency.

More broadly, Irish restrictions were not accepted uncritically by the press. Riddell forwarded a protest addressed to the chief secretary for Ireland, Henry Duke, against D482, which had requested ‘careful discrimination’ in any reporting of unrest within the Dublin police over pay and working conditions because it was ‘only likely to increase any trouble that exists’.Footnote 70 The NPA countered that ‘censoring of news concerning internal affairs unconnected with the military situation’ was against the public interest.Footnote 71 Again, in July 1917, Riddell forwarded a resolution complaining about the proscription of commentary on the Convention, covered by Defence of the Realm Regulation 27a. The NPA protested that ‘prohibitions of such a sweeping and drastic character are prejudicial to the public interest and…incapable of enforcement’.Footnote 72 Notably, however, these protests were directed at government departments rather than the Bureau itself. The latter protest, included alongside another resolution seeking to maintain editors’ existing relations with the Bureau, rather than engage with John Buchan as director of the Department of Information, led Riddell to affirm the ‘cordial and friendly character’ of the Bureau's relations with the press.Footnote 73 Notwithstanding damaging early friction,Footnote 74 by 1917 editors had apparently reached a tolerable equilibrium with the Bureau.

Little justification was offered or, apparently, sought, however, when news of Sinn Féin was suppressed. One notice, seeking silence on a speech by Arthur Griffith, apparently related to the wider, standing, instruction not to publish details of the Convention's activities, about which he had commented.Footnote 75 Another, Ireland D18, issued in January 1919, contained a clear public order imperative, reminding editors to avoid quoting any Sinn Féin materials ‘which directly or indirectly incite to the commission of unlawful acts’.Footnote 76 Despite these technicalities, however, Bureau communications regarding Ireland stretched the bounds of its general operating principles considerably. Some simply suppressed speeches and statements by Sinn Féin figures, such as Fr. Michael O'Flanagan's speech at Ballyjamesduff in May 1918 supporting Griffith's East Cavan by-election campaign, and a statement by O'Flanagan, Alderman Thomas Kelly, and Harry Boland after the by-election in August,Footnote 77 showing an apparent conviction in Dublin Castle that Sinn Féin's voice should not be heard. While, arguably, such prohibitions were security-oriented insofar as they sought to minimize the impact of disruption within Britain and Ireland which might affect the conduct of total war, such interventions were a long way from the Bureau's usual notices. While it issued very rare notices regarding other speeches thereafter,Footnote 78 from January 1916 the Bureau obtained Samuel's endorsement for the general principle that public speeches could be published at newspapers’ ‘own risk’ without prior submission for censorship.Footnote 79 Proscribing reports of public Sinn Féin activities, therefore, represents a further instance of British authorities applying different rules to Ireland.

IV

Notifying editors about arrests in February 1917, the Irish Censor, through the Bureau, permitted publication, but urged the avoidance of ‘speculation of sensational character’ which might ‘inflame public opinion’.Footnote 80 Arguably, where the Bureau was most likely to lose newspapers’ sympathy was when it went further than indicating a necessary restriction of commentary, and presumed to set the tone of reporting.Footnote 81 Editors tolerated unwelcome limits on information, but rarely received comments in notices on the appropriate view to hold without a fierce reaction. Arguably, such retorts gave editors a chance to reassert their independence and reject any suggestion of absolute official authority over news. At various infrequent points, around matters including atrocities, air raids, or military ‘successes’, editors were chastised for over-sensational coverage's potential effects on morale. In September 1914, the Bureau asked newspapers to carefully check atrocity allegations, since there was ‘much weighty material establishing the charge of atrocious misconduct + the fact of this is weakened by the dissemination of unauthenticated charges which break down under examination’.Footnote 82 Officials welcomed content damaging to enemies, but not regardless of accuracy – this was a plea for better researched news, not for more sensationalized attacks on Germany. Three messages asserted the risks of unnecessarily alarming the public through over-dramatic discussion of air raids,Footnote 83 while newspapers were also asked neither to exaggerate losses,Footnote 84 nor to inflate small events into large successes, which it was felt would undermine civilians’ realization of the war's seriousness:

The magnitude of the British task in this great war runs serious risk of being overlooked by reason of exaggerated accounts of successes printed daily in the Press especially by exhibiting posters framed to catch the eye…Germany is represented as within measurable distance of starvation, bankruptcy + revolution, and, only yesterday, a poster was issued in London declaring that half the Hungarian army had been annihilated.

All sense of just proportion is thus lost and…the public can have no true appreciation of the facts or of the gigantic task and heavy sacrifices before them.Footnote 85

In this instance, issued fairly early in the war in March 1915, in the midst of the British Expeditionary Force's first major 1915 battle at Neuve Chapelle (a limited tactical success with little wider strategic impact),Footnote 86 the Bureau's aim was not to have the press ‘pull the wool over the public's eyes’ but to manage expectations and avoid too relaxed a perspective.

Nonetheless, while largely prepared to obey instructions for security reasons, experienced editors and journalists dismissed lectures on their choices of language or emphases.Footnote 87 In this case, Riddell shot back that if ‘the people are being unduly soothed and elated, this responsibility lies with the Government…The Press acts upon the news supplied. If this is inaccurate or incomplete, the Government cannot blame the Press.’Footnote 88 Since newspapers made do with limited information released by government departments, editors would not accept attempts to dictate how newspapers pieced together these fragments. While Riddell's response stressed the need to offer the public real and full information to obtain real and full commitment, arguably, this dispute also reflected the divergence caused by the pressures of wartime administration on one hand, and of commercial news producers on the other. Newspapers needed posters with eye-catching headlines to attract buyers in a wartime environment which, as the war continued, increasingly emphasized ‘thrift’ and the abandonment of wasteful spending.Footnote 89

Editors accepted that some information was too sensitive to publish, but were less inclined to withhold so much information or opinion that readers stopped buying their product. When the Bureau prohibited coverage of U-boat attacks on steamer vessels in July 1915, R. A. Walling, editor of the Plymouth-based Western Daily Mercury, for which ‘all naval questions are of the greatest importance’, protested restrictions on reporting attacks on steamships, arguing that the claim that restrictions aimed to prevent information reaching Germany was inconsistent, and asked for a statement of the wider principles governing notices. Replying, Swettenham told Riddell that the Bureau simply followed Admiralty instructions, but argued that war necessitated some inconsistency, said that preventing information was ‘only one of the principles’ driving Bureau actions (without stating the others), and explained that an inconsistency noted by Walling was explained by the presence of US citizens aboard a ship in a previously reported case.Footnote 90 As with some Irish notices, wider concerns to stimulate US opinion were prominent here. Some editors, like H. W. Massingham, went further, rejecting the notices because they were meant to regulate news, not opinion.Footnote 91 This may have retorted to the prohibition of the Nation's overseas export at the request of the War Office, ordered the previous month. If this ban hurt the Nation's reputation in some quarters, it did not hurt it commercially. During 1917, its average circulation rose by more than 2,000 copies,Footnote 92 and it continued to publish material that criticized the government, like J. A. Hobson's pseudonymous series of articles satirizing censorship, propaganda, and the Defence of the Realm Act.Footnote 93 This allowed the Nation, domestically at least, to continue exerting the ‘power of…influenc[ing] those who influence others’, perhaps largely because it was ‘not…a widely popular journal’,Footnote 94 and thus unlikely to have major, immediate impacts. The lack of reaction to domestic press criticism is interpreted by some historians as showing the state's crafty manipulation of public opinion. Letting attacks by noted critics pass uncensored, in this interpretation, showed that Britain retained a free press, or even helped direct aggressive patriots to disrupt public gatherings addressed by the critics.Footnote 95 By contrast, Cook argued that ‘[p]ermission was, throughout the war, the rule; prohibition the exception’, and that the same account reproduced in 100 newspapers would provide value to neither the public nor the state.Footnote 96 The journalist J. Saxon Mills, a somewhat hagiographic biographer, suggested that, as a career journalist, Cook's sympathies lay in balancing ‘wise consideration’ of the ‘higher national interest’ with ‘all possible allowance’ for the press's ‘insatiable thirst for news’.Footnote 97 Another interpretation, suggested by the occasional couching of notices as guidance to ‘right-thinking’ journalists, is that permitting critical voices would strengthen rather than weaken public support for the war.

Correspondence with Riddell shows that, as Wilkinson and others have noted previously, the press accepted the Bureau's general necessity while regularly questioning its judgement. Frank and regular criticism and, sometimes, support, does not suggest the state's overbearing restriction of press freedom. Rather, because editors maintained ‘habitual informal contacts’ and influence with government,Footnote 98 representatives like Riddell could confidently resist undue limits. Likewise, such connections meant the Bureau knew it could usually trust editors to stay within bounds. As Cook noted when accepting Riddell's advice to add further newspapers to a list receiving confidential information, ‘the real security…is the good faith of the editors, which there is no reason to doubt’.Footnote 99 Far from always demanding fuller information, the NPA sometimes suggested the Bureau adjust its instructions to avoid revealing too much. In January 1916, Riddell, presumably referring to D307, which asked for no commentary on planned arrests (implicitly of spies), warned Swettenham ‘it was a matter of absolute impossibility’ that newspapers could ensure this information did not leave their offices. Rather than giving so much detail, simply naming a suspected spy to editors would prevent coverage. The Bureau responded that it had already circulated a new notice, D344, providing generic instructions not to discuss any aspect of spy cases unless information was officially supplied for publication and, to Riddell's irritation, suggested the Bureau should be able to trust newspapers to keep secret instructions secret. Though the exchange became tetchy, the editors’ intent to help was clear, a circular sent by the Bureau to government departments on appropriate content soon after showed they had conceded the point, and Riddell sympathized with the Bureau's ‘difficult and irksome position’.Footnote 100 Familiarity and co-operation thus allowed genuine debate between editors and censorship directors about what was appropriate.

On another occasion, Riddell approached Sir Eric Geddes, first lord of the Admiralty, seeking more positive news about the navy. Without compelling information from the Admiralty, he argued, ‘our cause in America is being seriously prejudiced by our silence’ and assumptions of inaction, while ‘our own people don't appreciate what the Navy has done and is doing’. Riddell's letter showed shared concerns with officials regarding US opinion, as well as newspapers’ intent to boost domestic opinion. At the same time, however, the ensuing discussion showed press discomfort with supplied content. Writing to the naval censor, Douglas Brownrigg, Riddell stressed that ‘the newspapers are anxious for individual action in order to avoid stereotyped matter…[They] do not want matter written up by authors and literary men…the work should be done by journalists who understand newspaper requirements.’Footnote 101 Such complaints were increasingly common. At a regular conference of London and provincial newspapers in November 1916, editors protested the increasing, undesirable practice of departments issuing ‘editorial paragraphs’ to the press as formal notices, thus ‘flooding the newspapers with identical articles’. Partly related to a desire to charge departments for ‘advertisements’, and partly to resented privileges for ‘special writers’ rather than newspapers’ journalists,Footnote 102 the complaint largely reflected concern that placed content did not meet newspapers’ needs or style. Such concerns became even more pressing with later paper shortages, and Riddell protested again in March 1918 that the Bureau issued many trade notices ‘of no general interest’. It was ‘impossible to fill newspapers with a quantity of dull matter which interests only a few people’. These critiques of content placement show the limits of official press control. Riddell and his colleagues tolerated D notice restrictions, but refused to dump unpaid ‘technical and uninteresting’ prose into their papers to accommodate departments.Footnote 103 MI7b, which supplied varied content, including some similarly dull and technical detail around topics like ‘A new way of supplying the army with meat’, at least met press objections to inappropriate material by offering its lengthy accounts ‘not for reproduction…but as a basis…for articles’ produced by journalists. Even MI7b, however, also supplied more literary pieces by authors including A. A. Milne, Lord Dunsany, and Patrick MacGill, with no such invitation to journalists to adapt.Footnote 104 Editors then, with some complaints about restrictions they found unwise, largely accepted that some information should not be published. They proved far less willing to uncritically reproduce government prose, or accept advice on the tone adopted in reporting what news remained. Riddell's sometimes barbed, sometimes friendly correspondence with Swettenham and Cook shows the extent to which press control remained negotiated rather than dictated.

V

At the most basic level, D notices instructed editors about topics that could, or could not, be safely discussed. This accompanied the Bureau's direct censorship of submitted articles; provision of less frequent notices supplying information for newspapers;Footnote 105 and monitoring and potentially reporting transgressions to the director of public prosecutions. Government departments and other organizations, including MI7b and the NWAC also sought to place content as press material,Footnote 106 sometimes to the Bureau's discontent,Footnote 107 as well as editors’. The Bureau depended on editors’ goodwill to ensure most notices were followed. Alongside this formal apparatus, as Rose, Millman, Hopkin, and others note, were various potentially coercive informal pressures on journalists. However, as Cook's and Swettenham's combative but cordial exchanges with Riddell show, editors differentiated the Bureau's actions from government departments, recognizing its awkward intermediary role. As noted, it sometimes rejected both departmental and press requests to restrict opinion, and showed willingness to adjust some regulations after press concerns. More thorough investigation of the D notices, therefore, clarifies the representation of the war desired by the state, but filtered by the Bureau, which recognized the value of diverse, not uniform, press commentary. The Bureau's wartime constraints irritated editors, but the organization's necessity was recognized. This article's survey of D notice content, and press reactions to it, reveals that, in steering and shaping press commentary on the war's events, the Bureau did not, generally, seek to prevent or obscure criticism of military or political activities or individuals. Irish affairs were treated less liberally, and the Bureau became more open to discussion of industrial strife as the war continued, but a clear concern with security is evident in most notices. Many were issued because commentary might provide revealing information about security-related activities; the location of individuals or facilities which could become targets for attack; or information that would help Britain's enemies. By contrast, with few exceptions (noted above), notices rarely intruded in matters of public interest that might inconvenience the state, government, armed forces, or individuals where such matters carried no security risk, though they did sometimes chide newspapers’ perceived excesses. If the Bureau over-cautiously censored topics with small likely risks, it was primarily concerned with preventing unnecessary loss and damage, not deceiving the public about wartime events. Where it questioned newspapers’ tone, this was not necessarily to demand more positive coverage, but to suggest what it considered, perhaps pompously, more serious and sensible commentary, and editors like Riddell sometimes had to seek more positive content for themselves. The D notice system, improvised during wartime, struck a balance which stressed security, ‘patriotism’, and seriousness and accuracy, received (and sometimes adapted to) criticism, generally allowed publication of critical opinions, and helped maintain a largely diverse and free wartime press. As a whole, the Bureau's notices aimed more at safe news than fake news.

Acknowledgements

Early versions of this article were presented to the History Department research seminar, University of Canterbury, and to the International Society for First World War Studies ‘Recording, narrating and archiving the First World War’ conference (Melbourne, July 2018). I thank the audiences of both these events for their comments, as well as the editor and reviewers of the Historical Journal for their further valuable suggestions.

Funding Statement

Attendance at the International Society for First World War Studies conference was supported by a grant from the School of Humanities and Creative Arts, University of Canterbury, to which I am grateful. Open access publication was generously funded by the University of Canterbury Library Open Access Fund and by the College of Arts, University of Canterbury.