Abstract

Sustainability science is, per se, a topic that is inherently interdisciplinarity and oriented towards the resolution of societal problems. In this paper, we propose a classification of scientific journals that composes the journal category “Green and Sustainable Science and Technology” in the period 2014–2018 through the entropy-based disciplinarity indicator (EBDI). This indicator allows the classification of scientific journals in four types based on the citing and cited dimensions: knowledge importer, knowledge exporter, disciplinary and interdisciplinarity. Moreover, the relationship between this taxonomy and the JCR bibliometric indicators and its predictive capacity of the taxonomy is explored through a CHAID tree. As well, relations between the Web of Science categories, journals and taxonomy are explored by the co-occurrence of categories and correspondence analysis. Results suggest that the great majority of journals in this field are specialized or interdisciplinary. However, over the 5-year period proposed in this study, interdisciplinary journals tend to be far more stable than specialized ones. The decision tree has shown that the number of citations is the variable with the greatest discriminating capacity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Scientific disciplines have evolved as such through a complex process only from the 1700’s onwards, followed by an increased speed in the delineation of disciplinary boundaries in the XIX and XX centuries (Abramo et al., 2019). Post-war developments in university and research structures gave rise to ‘Big science’ in a broad sense (Weinberg, 1961) and, given the diverse type of scientific and technical types of knowledge required for the attainment of such projects’ objectives, this was followed by an increase in the interest of inter / multidisciplinarity. The integration of different perspectives, methodologies and procedures in the pursuit of a main scientific objective has remained a difficult task for researchers, but also for those in charge of establishing policy goals and allocating research funds (Braun & Schubert, 2003; Lee & Bozeman, 2005; Lyal et al., 2013). As a result, IDR was initially addressed from the perspective of research policy and management. The results of interdisciplinary research in terms of citations do not allow concluding that that there is a linear, positive relationship between the degree of interdisciplinarity and the volume of citations (Lariviere et al., 2015; Yegros-Yegros et al. 2015).

The phenomenon usually termed ‘Interdisciplinary Research’ or IDR (e.g. Davé et al. 2016) has been an increasingly relevant object of research in various fields. IDR acronym seemingly appeared for the first time in a 1976 article in the IEEE Transactions on Engineering Managament (Nilles, 1976), although the issue of multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity and specialization had already been present in the academic discussion for more than a decade (Huutoniemi et al., 2010). Despite (or perhaps because of) this long presence in the academic realm, it is considered a multifaceted and somehow ambiguous concept (Wang & Schneider, 2019) and, at the same time, a tool to tackle pressing societal problems (Mugabushaka et al., 2016). Addressing real-world issues is clearly related to informing policy decisions.

Considerable efforts have been made to define, operationalise, and measure the concept of interdisciplinarity. For instance, the National Academies of Sciences (US) defined Interdisciplinary Research (IDR) as “[…] a mode of research by teams or individuals that integrates information, data, techniques, tools, perspectives, concepts, and/or theories from two or more disciplines or bodies of specialized knowledge to advance fundamental understanding or to solve problems whose solutions are beyond the scope of a single discipline or field of research practice” (National Academies, 2004). This approach pursuits the integration of different disciplines to enable mutual development on the objectives and the approaches of the research problem as well as to create joint solutions. Although there is no ‘official’ definition of IDR, that provided by the National Academies is often referenced in bibliometric studies. Despite the relatively frequent attempts to provide accurate descriptions and definitions of the concepts related to interdisciplinarity (Broto et al., 2009; Huutoniemi et al., 2010), current research is far from a consensual definition and some inconsistencies have been identified (for instance, information abundance vs specialization) (Wang & Schneider, 2019). Some of the operative definitions, procedures and indicators have been developed in from the bibliometric approach (see Wang & Schneider, 2019). One of the aims of the study of IRD research is to analyse the research output and determine to which extent there is integration of knowledge generated in other fields and up to which point the knowledge generated in the research output under study is used in a variety of other fields.

One possible differentiation between the approaches to the measurement of IDR in bibliometric studies is that of the classification scheme of fields of knowledge: it is possible to distinguish between bottom-up approaches and top-down approaches (Leydesdorff, 2007 as bottom up; Rafols & Meyer, 2010 as top-down), as well as the use of citation networks and derived indicators (Leydesdorff & Rafols, 2012). Also, the level of analysis is a relevant dimension distinguishing between the various procedures developed for the measurement and study of IDR, ranging from individual articles and journals (in example, Zhang et al. 2016) or at the level of institutions (Huang et al. 2016, using Hill-type indicators). Of particular relevance for the study of IDR are the indicators derived from other fields (ecology in general and biodiversity analyses in particular or economy), such as the Hill-type family indicators proposed by Mugabushaka et al. (2016) or the Gini coefficient (Leyesdorff & Rafols, 2011). In terms of operationalization, the data source selected and similar indicators produce different results and are sensitive to levels of analysis as stated by Wang and Schneider (2019) and Digital Science (2016). This fact affects the validity of those measures, denoting that no single criteria or indicators are agreed to identify IDR measures.

Sustainable development was a concept firstly introduced in the 80 s with a simple essence: development that meets the needs of humankind without compromising the ability of future generations. This concept reflected the struggle of the world population for achieving better conditions and growth in a healthy environment. However, this constitutes a complex idea that cannot be simply applied. As a result, a new research paradigm was needed to reflect the complexity and the multidimensional character of sustainable development (Martens, 2006). Thus, Sustainability Science (SS hereafter) emerged as a scientific field that investigates “complex and dynamic interactions between natural and human systems with the aim to bridge the gap between science and society and limit its knowledge to actions for sustainability” (Disterheft et al., 2013). Thus, it can be understood as a social contract between science and society (Lubchenco 1998). Although no consensus has emerged on its definition, many studies have explored this topic from a bibliometric perspective by using ‘sustainability’ or ‘sustainable development’ in the search query. In recent decades, SS has expanded considerably the number of publications, and the range of subdisciplines (Kajikawa et al., 2014). This is not surprising particularly given the current ecological crises facing in many parts of the world as well as the goal of a sustainable society, which has become a central task of science and technology (Holdren, 2008). For Nučič (2012) and Schoolman et al. (2012) this is associated with the fact that is highly interdisciplinary research field. Undeniable, most scientific disciplines are able to contribute toward sustainability, because “issues in sustainability have complex structures that include environmental, technological, societal, and economic facets” (Kajikawa et al., 2014). Sustainability itself is inherently complex and linked to the human world, so the “research in this framework involves different disciplines to enable mutual development on the scopes and approaches to the problem” (Lam et al., 2014). Therefore, this model of the interconnectedness of natural, socio-cultural, and economic systems implies a genuine pursuit of sustainability and requires an interdisciplinary approach. As Thorén and Persson (2013) claims, sustainability issues are usually defined in natural sciences and later exported to social sciences. Considering that its intrinsically multidisciplinary nature is often emphasized, it is important to identify and explore its interdisciplinary approach.

Theinterdisciplinarity of sustainability science has been explored from a bibliometric point of view in previous studies. Kajikawa and Mori (2009) measured interdisciplinarity in a sustainability science dataset (n = 19,992) with a set of indicators (betweenness centrality, diversity of references and diversity of references of reference) from citation network analysis. These authors concluded there are divergences on results obtained for the sustainability papers identified according to the indicator used. In the work of Bettencourt and Kaur, (2011), interdisciplinarity is calculated in terms of the distribution across WoS’ categories (WCs hereafter) as well as via the collaboration network of over 20,000 papers. They concluded that this field WC evolved as a collaboration network unified with a giant cluster of co-authorship around the year 2000. Other authors analyzed interdisciplinarity of sustainable science (SS hereafter) based on the triple-bottom approach (TBL).Footnote 1 Nučič (2012) measured interdisciplinarity by using the integration index and overlay maps visualization. Results point out that SS is a highly interdisciplinary field, especially in the case of environmental studies. On the contrary, Schoolman et al. (2012) using the Shannon entropy determined that this field is not uniformly interdisciplinarity, being the economic pillar the more interdisciplinary instead. Later, Buter and Van Raan (2013) presented a research based on the citation networks by considering highly cited sustainability documents documents. They calculated the diversity of clusters and they concluded the interdisciplinary approach of this field is still developing and researchers are still integrating knowledge from a variety of fields. Lam et al. (2014) analysed different attributes (academic and disciplinary nature) of 70 papers that are specifically addressing interdisciplinarity in sustainability studies. They concluded that interdisciplinary studies are scarce (but growing) and none of the studies achieved a whole approach.

In 2006, a newWoS category was created in Web of Science (WoS) called “Green & Sustainable Science & Technology” (GSS&T hereafter). This WoS Category has been explored quantitatively in previous studies (Bautista-Puig, 2020; Bautista-Puig et al. 2019; De Filippo & Serrano-López, 2018; Pandiella-Dominique et al. 2018). According to Web of Sciences,Footnote 2 this category “covers resources that focus on basic and applied research on green and sustainable science and technology, including green chemistry; green nanotechnology; green building; renewable and green materials; sustainable processing and engineering; sustainable policy, management and development; environmental and agricultural sustainability; renewable and sustainable energy; and innovative technologies that reduce or eliminate damage to health and the environment.” As pointed by Pandiella-Dominique et al. (2018), ‘the creation of a new WoS category would therefore attest to the scientific interest generated by certain subjects in the academic community”. However, as accounted by Bautista-Puig et al. (2019) this WC is related to sustainability science, although presents some biases towards environmental sustainability.

Objectives

This study counts with three objectives:

-

1.

To measure the degree of specialization / interdisciplinarity of journals in the WoS category Green & Sustainable Science and Technology.

-

2.

To develop a taxonomy of the journals in the WC according to their specialization / interdisciplinarity in the citing/cited dimensions and the combinations thereof.

-

3.

To analyze the statistical relationship between the role taxonomy and the bibliometric indicators included in JCR and, indirectly, the predictive capacity of the taxonomy with regards to those same indicators.

Data and methods

Sustainability journals dataset

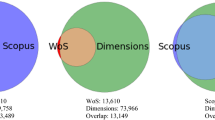

As SC, we considered the recently created (2016) WC GSS&T.The reasons for choosing this WC are: (a) its relatedness with sustainability science, for which there is a certain number of previous studies that would allow a valid starting point to this research and an interpretation in context of its results and, at the same time, accomplishing the following condition: (b) its relative youth, hence allowing the study of the evolution of the journals concerning their interdisciplinarity in the initial stages of the conformation of the field, (c) the existence of previous studies on the interdisciplinarity of the field, which allows counting with a theoretical baseline and framework on the expectable results of our analyses and (d) the lack, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, of a quantitative taxonomy of journals role in a recently ‘formalised’ (from the perspective of systematized set of journals under a WC denomination) discipline. Our approach starts with the premise that interdisciplinarity of this field can be examined based on the citations and references of the 40 sustainability journals listed in this category. We have used the CWTS in-house WoS database for this study: 57,227 articles have been identified, with 2,035,616 cited and 744,813 citing references were collected in a 5-year period, from 2014 to 2018. The CWTS database contains WoS data with some fundamental enhancements. For instance, it has a more efficient citation matching algorithm than the one in WoS (see Olensky et al., 2016). In this study, we have considered the Core collection databases (Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI), Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) and Arts & Humanities Citation Index (A&HCI)). We selected the period 2014–2018 based on the recent years that also coincides with the launch of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Moreover, we have used the most-updated Journal Citation Reports (JCR) 2018Footnote 3 version for identifying all the subject categories for the calculations of the indicator. 253 unique subject categories were identified by this dataset.

Measurement of specialization / interdisciplinarity and taxonomy of journals

For measuring the interdisciplinarity of GSS&T we have used the Entropy-Based Disciplinarity Indicator (EBDI). The indicator was presented, applied and its properties theoretically tested in a 2017 publication together with the derived taxonomy (Mañana-Rodríguez, 2017).

\(\% IC\) is the percentage of citations from or to journals classified at least in the same WoS category as the unit on which the indicator is being calculated (percentage of internal citations). \(\% H_{{{\text{MAX }}\left( {{\text{EC}}} \right){ + 1}}}\) is the percentage that the entropy associated to the distribution of external citations represents respect the maximum entropy associated to the distribution of external citations (ln n, n being the maximum number of possible WC’s in the system).

The rationale behind the indicator is based on the idea that the act of citing a work implies a certain relevance of the cited work to the citing work, regardless of the discipline in which that publication has been classified in an information system. The frequency with which the citations are directed towards (or received by) items classified in the same field as the citing publication channel (% internal citation) is understood here as a proxy for the citing/cited publications’ specialization in that field. The percentage of cited references/citations received by the item under analysis by journals from fields different from that in which it has been classified are a proxy for the inter-disciplinarity of the item. The greater the number of different fields and evenness in the distribution of references/citations across fields, the greater the inter-disciplinarity. These two features are captured by the Shannon-Weiner index in the denominator of the indicator. The indicator has a numerator proportional to the item’s specialization and a denominator conversely proportional to the item’s specialization; hence its values increase with the item’s specialization and vice-versa.

The indicator can be applied to the citations received (Cited dimension) and to the cited references (Citing dimension), hence producing an overview of the values of interdiscplinarity in both dimensions. There are several reasons for the use of this indicator instead of others, including those systematized in Wang and Schneider (2019). (a) The field of G&SST seems to be, according to existing literature, a markedly interdisciplinary field. This implies that using similarity indexes such RS index (Wang et al. 2015) or the Hill-Type measures (Zhang et al., 2016). The large variety of categories in the citing and cited dimensions for the journals of this field might diminish the usefulness of indicators that use cognitive distance as a factor positively related to multidisciplinarity since the measures of distance would be greatly reduced in such a set of journals. (b) The theoretical robustness and validity of the indicator have been tested (Mañana-Rodríguez, 2018) and (c) The possible use of the indicator to create a taxonomy of journals according to their role (which is the main objective of this work) has been developed previously (op.cit., 2018) using this indicator (although it is likely that other indicators, applied to the citing and cited dimensions could be used to create a taxonomy of journals too).

The taxonomy used in this study can be summarized as follows:

-

Specialized journal: high EBDI values obtained in citing and cited dimension (most citations come from and are received by journals from the same SC, and the item is of interest primarily for specialists in the field).

-

Importer journal: high values in the cited dimension and low in values in the citing dimension (the knowledge basis of the research published is mainly outside its field, drawing knowledge from publications from other fields. Once that knowledge is integrated in the item’s corpus it becomes interesting, mainly, for specialists in its field).

-

Exporter Journal: opposite values to that of an importer journal.

-

Multidisciplinary journal: low values in cited and citing dimension (the item has its knowledge basis outside the field in which it has been classified and it is of interest for a wide variety of specialists in several fields)

Exporter and multidisciplinary are the subsets of the set of interdisciplinary journals, while specialized and importer are the subsets of the set of specialized journals (Fig. 1).

The cutting point used in this study is the median of the distribution of EBDI in each dimension. The reason for using the median instead of other central tendency statistics is the fact that the distribution of citations through WC very rarely follows a normal distribution. A Kolmogorov–Smirnov normality test was applied, finding that none of the two (EBDI_Cited nor EBDI_Citing) are normally distributed (for EBDI_Cited, D (40) = 0.222; p = 0.001 and for EBDI_Citing D (40) = ,199; p = 0.001). For non-normal distributions, such as the one that relates citation frequency and disciplines the median is a more informative statistic than its usual alternatives (mean trimmed mean and others). High EBDI translates into a value equal or higher than the median of EBDI for that dimension (cited or citing) for the set of journals in the WC and low EBDI into a value lower than the media. Considering that journals could be co-classified into different WoS Categories, a straightforward fractional counting with weight system has been applied. For instance, if a journal is classified into three subject categories a fractional weight of 1/3 is considered.

Example of the calculation of the indicator (for the citing dimension; the data is fictitious) (Table 1).

Diversity analysis

With the aim to determine diversity and interrelations between WoS categories of this dataset, a co-occurrence of WoS categories using the VosViewer tool has been conducted. Besides, a correspondence analysis (CA) to explore the relationship between WoS categories and journals was performed.

Set of JCR indicators and statistical analyses

In order to achieve objective 3, the whole set of indicators available in JCR for the journals plus the quartile of belonging of each of them in the WC was retrieved for the 2018 edition. These indicators are: Total cites / Journal Impact Factor / Impact Factor without Journal Self Cites / 5-year Impact Factor / Immediacy Index / Citable Items / Cited Half-Life / Citing Half-Life / Eigenfactor Score / Article Influence Score/ % Articles in Citable Items / Average Jorunal Impact Factor Percentile / Normalized Eigenfactor. After testing the assumption of normality with the K-S and observing that most of the variables did not follow a normal distribution it was decided to use the Mann Whitney U-Test in order to contrast the existence of statistically significant differences between the mean ranks of the values (of the indicators mentioned above) for two groups: Multidisciplinary and exporter journals on the one hand and Specialized and importer journals on the other (the grouping responds to the small number of importer / exporter journals identified). According to Mañana-Rodríguez (2017), the combination of multidisciplinary + exporter is referred to as ‘Interdisciplinary’ journals, so we will use the term ‘Interdisciplinary’ hereafter. Also, in order to get an exploratory notion of the predictive capacity or capacity for the segmentation of a sample of the taxonomy developed in this work a segmentation tree was developed, having the grouping Specialized + importer / Interdisciplinary (Multidisciplinary + Exporter) grouping and as dependant variable and the rest of the indicators as independent variables (CHAID algorithm with crossvalidation, maximum tree depth 3 [by default in CHAID], minimum cases in parent node 4, minimum cases in child node 2).

Results

Table 2 shows the distribution of journals according to the taxonomy defined based on the calculation of the EBDI. The table shows that the proportions of journals in each of the four profiles are relatively stable across the years studied, with a dominance of specialized (43.69% on average) and multidisciplinary journals (45.37% on average) and a much smaller number of importer and exporter journals (5.47% both). The predominant role of specialized journals has increased slightly over time (42.86–47.50%), while multidisciplinary journals have also increased (around 2 percentage points) during the period of study. Importer and exporter profile journals have reduced to almost half the initial percentage over the period.

Figure 2 shows the results of the application of EBDI to the WC related to sustainability science. The great majority of the journals on this set are classified into the multidisciplinary (e.g. ‘Sustainable Development’, ‘Journal of Renewable Materials’…) or specialized profiles (e.g. ‘Journal of Cleaner Production’, ‘Renewable Energy’, ‘Sustainability’…). On the other hand, we find two journals that are importers on the field (‘Energy efficiency’ and ‘International Journal of Green Energy’), while two are exporters (‘International Journal of Sustainability’ in ‘Higher Education and Sustainability Science’).

These classifications are corroboree by the Fig. 3, which shows correlation between cited and citing EBDI values (r = 0.980; R2 = 0.960), showing also how specialized journals appears with high values on cited and citing EBDI, while multidisciplinary journals are positioned on the left of the plot, with lower values for cited and citing EBDI.

Table 3 shows the evolution over time of the five-year period of the taxonomy of the journals identified. Considering the stability over time of the different profiles, it is interesting to mention that the multidisciplinary journals presents a more similar profile over the period than the specialized ones: from the 18 journals that are multidisciplinary considering the data for the whole 2014–2018 period, only one has had a different value in the taxonomy (the journal ‘Agronomy for Sustainable Development’, which was importer in 2015), whereas among the 18 specialized journals five have had a different role in the period under study. Hence, it can be said that, for this set of journals, multidisciplinary profiles tend to be more stable in their role than specialized journals. There are journals that have passed from exporter profiles to specialized journals (e.g. ‘Sustainable Cities and Society’ and ‘Journal of Sustainable Tourism’). Some other presents a more intermittent evolution. For instance, Environmental Progress & Sustainable Energy was an importer (2014–2016, 2018), and specialized one year (2017).

From now on, we are going to present the results in aggregate terms: specialized and interdisciplinary. The Mann–Whitney U tests show that there are statistically significant differences in most of the indicators considered, with the exception of cited half life, eigenfactor score, article influence scores and % of articles in citable items. In the variables Total Cites, Journal Impact Factor, 5-Year Impact Factor, and Citable Items there are statistically significant differences between the two groups. The only variable in which the mean rank is greater in the case of the interdisciplinary group than in the specialized-importer is that of the citing half-life (Table 4).

In order to analyze if the position of each journal in the distribution of impact factor in terms of the position in the impact factor distribution is independent of the two types of journals with the greatest number of cases identified in the taxonomy (specialized and interdisciplinary) a Pearson Chi-squared independence test were used (Table 5). Results show that at a significance of 0.001 being at a position equal or greater than the median for the distribution of impact factor or below that cutting point is not independent of the likelihood of being classified as specialized or interdisciplinary by the role taxonomy of journals. In fact, there is a strong association.

A CHAID tree was performed with cross-validation considering the groups Specialized + importer / Interdisciplinary as dependent variables and the rest of indicators as independent variables. These trees analysis allows the examination of the results and allows the identification of potential factors and determine their relationships. Figure 4 shows the CHAID decision tree. Each node contains three statistical values: category (node number), ‘%’ (percentage of journals) and n (number of journals disaggregated in both categories). The CHAID tree starts with the groups decision node divided into two partitions, based on the splitting number of citations (limit of 2421 cits.). Predictors were similar (48.7 in the first group vs 51.3 in the second group). The second group ‘Interdisciplinary’ shows the majority of cases associated with a below value (> 2421) whereas the group ‘Specialized + Importer’ is above. Both nodes are further split on the basis of the value “% of articles in citable items’ resulting into two more nodes with different limit values (117 for Node 1 and 7 for Node 2). In the first division, the strongest predictor was below or equal to 117 (41%) with ‘Interdisciplinary’ journals (100%). In the second segmentation, is it outstanding the values of the Node 5 (< = 7, 43.6%) among 'Specialized + importer' (100%) profile.

Table 6 shows the resubstitution and cross-validation error rate of decision tree. The resubstitution method of risk analysis shows an estimate of 0.051. This means that the risk of misclassification of the cases in the two categories using these independent variables is 5.1%. This risk is greater in the case of the cross-validation (17.9%).

The sensitivity and specificity values indicate that the tree model classifies correctly 94.9% of the cases, suggesting that results are acceptable (Table 7). This value is slightly higher in the ‘Specialized + importer’ group (95%).

Diversity in the co-classification scheme of the two main types of roles

In order to explore possible differences in the journals that have been classified as interdisciplinary and specialized in the taxonomy in their co-classification schemes, we summarized the information on the co-classification subject categories of the journals in the two groups according to the 2018 edition of JCR. The first result indicates that all the journals in the category are co-classified in a field other than G&SST. Nevertheless, there is much greater diversity in the case of the journals classified as interdisciplinary: there are 22 different fields in which the 19 interdisciplinary journals are co-classified whereas the same number is 8 for the journals classified as specialized. Despite the fact that this observation cannot be considered a form of extensive validation, the lower number of fields in which the journals classified as specialized are co-classified together with G&SST is congruent with the co-classification of journals as an indicator of their multidisciplinarity or specialization developed by Morillo et al. (2003). Results of the different co-occurrence maps by year suggests there are stronger connections between WC within specialized journals (#linkstrength of 8.20 vs 4.00) (Tables 9, 10 from Appendix). The interconnection between WC measured by strengths has increased over time in both typologies, being higher in multidisciplinary journals (0.76 vs 0.05). This denotes the topics are more 'connected' in interdisciplinary field over time.

Also, it is interesting to note that the degree of overlap between categories within both taxonomy journals. Six of twenty-one of the fields in which the interdisciplinary journals’ are co-classified appear in the list of WC’s in which the interdisciplinary journals are co-classified. Thus, specialized journals have four unique WC’s, while interdisciplinary has 15 WC that do not overlap. This observation could point out towards a different thematic structure between the two types of journals (Fig. 5).

On the other hand, co-classification of journals are also represented on the correspondence analysis of Fig. 6, which shows how specialized journals are positioned closer of the main category (GSS&T), while most interdisciplinary journals trends to take a position closer to other categories (mainly Chemistry, Energy & Fuels and Environmental Sciences).

Discussion and conclusions

The concept of sustainability science has acquired a scientific and social dimension that transcends the traditional boundaries of the scientific field. Considering the current sustainability challenges in the world (e.g. deforestation, land degradation, climate change, pandemic…) sustainability science is a bridge between natural and social sciences for seeking solutions to these complex challenges (Jerneck et al., 2011). As Fang et al. (2018) points, is a use-inspired, basic science of sustainable development, which focuses on understanding human–environment interactions and has become an increasingly interdisciplinary and integrative field which spans natural and social sciences over the past two decades. Those authors even compare it with the health system: SS can be understood as "health services (i.e., sustainability) to human-environment systems that are facing or might face “health problems” (i.e., sustainability challenges)". Therefore, this implies the involvement of multiple actors (e.g. scientists, practitioners, societal actors…) to solve real-world problems. Taking into account that interdisciplinarity is one of the most relevant features, in this work we have applied an existing indicator in order to develop role taxonomy of the journals in the field of G& SST in order to identify knowledge dissemination patterns (Leydesdorff & Ivanova, 2020). These dissemination patterns take the form, in this research, of categories in the taxonomy. This allows the analysis of the role that the journals have and have had for the last five years.

Despite the fact that a taxonomy such as the presented in this work has not been extensively applied to the study of interdisciplinarity, it is possible to extract conclusions related to its potential usefulness given the fact that a large corpus of previous research does exist on the topic of IDR.

For instance, interdisciplinarity research is characterized because it addresses complex societal problems and may directly have an effect on the policy debates (Bark et al., 2016). Hence, these papers could have a broad societal and economic impact, not captured by citations (Brown, 2018). However, one of the main challenges identified in this research is its difficulty to be published (Castellani et al., 2016). On the other hand, specialized journals are fundamental for achieving a deep scientific understanding and comprehension of specific research domain. In addition, it has linked in previous studies with a high impact factor (Castellani et al., 2016). Despite this, one of the problems of those journals is its limited audience as well as the lack of experts on the field. At an operational level, previous studies reported challenges and obstacles for researchers like communication difficulties, tensions generated, institutional barriers in conducting this research (Roy et al., 2013).

Specialized journals are distributed into 10 WoS categories while interdisciplinary in 22. On this topic, specialized journals categories are energy and engineering-related (environmental perspective). In contrast, interdisciplinary journals are composed of a wide variety, including the social (Agriculture, Agronomy, etcetera) and the economic approach (Development studies). This might suggest greater knowledge integration from across different disciplines. This is also observed in the link strength, which suggests that the set of interdisciplinary journals is more inter-connected over time. Besides, the interdisciplinary journals tend to be far more stable than the specialized ones. Considering the growing tendency of SS (Fang et al., 2018), this could suggest a disrupted change and a set of new approaches in the research published by the journals of this field. Also, this observation could suggest that ‘becoming’ interdisciplinarity from a specialized initial position might require less deliberate action on behalf of the editorial teams of the journals than the opposite, specializing after being interdisciplinary.

The two exporter journals (Sustainability Science; International Journal of Sustainability in higher education) identified in this study, presents similar characteristics regarding its profile. Both, presented in their scope and aims of the journal a interdisciplinary approach. For instance, within the scope of ‘Sustainability science’ it is highlighted that “provides a trans-disciplinaryFootnote 4 platform for contributing to building sustainability science as an evolving academic discipline focusing on topics not addressed by conventional disciplines”.Footnote 5 On the other hand, ‘International Journal of Sustainability in higher education’ seeks its multi-level actor involvement (“journal is designed to be an international forum, relevant not only to people working in the academic sector, but also to practitioners, consultants and professional writers”Footnote 6).

Importer journals profiles are energy-related profiles (green energy and energy efficiency). This could be attributed to a niche on this topic. For instance, Kajikawa et al. (2014) showed a comparison of WC between 2007 and 2014 and determined energy issues are a relatively recent development.

Regarding the relationship with bibliometric indicators

The Mann–Whitney U test found statistical differences in most of the JCR indicators considered for specialized journals. This outcome is partially in agreement with previous studies that stated that the advantages for specialized journals are not so remarkable, except for the highly-cited papers (Abramo et al. 2019). This fact contradicts previous studies in which is general-interest journals have a higher impact value than specialized journals (Sundaraman et al., 2019). In contrast, interdisciplinary journals present a mean rank lower than specialized, showing no evident advantage. This is in line with Castellani et al., (2016), which determined that those journals do not present a higher citation impact (with the exception of some journals like Nature). Moreover, as pointed Van Noorden (2015), interdisciplinary papers have a higher citation impact in the long-term. However, in other fields such as educational research has shown that interdisciplinary journals obtain a broader impact than the core journals (Zurita et al., 2016).

The decision tree has shown that the number of citations is the variable with the greatest discriminating capacity. This implies that if a single variable had to be chosen so that it maximize the number of journals classified according to their specialization, that variable would be the number of citations. Specialized journals show greater presence in the nodes with the highest number of citations (hence, these two variables are not independent). Interdisciplinary journals in this field are characterized by a lower number of citations. According to Lariviere and Gingras (2010) this could depend on specific characteristics of the disciplines. This difference could be related also to the citation delay on the journals in this field (Brown, 2018), considering the short time window (5-year) of citations selected for this study. As pointed by Yegros-Yegros et al., (2015), a lack of impact could be justified due to the risky approach of those papers, making researchers more reluctant to cite heterodox papers that mix distant bodies of knowledge.

Concerning the validity of the indicator and the derived taxonomy, despite the numerous differences between a ‘construct’ and the indicator and taxonomy developed in this research, some of the validity criteria applicable to ‘constructs’ (in the psychometric meaning of the term) might apply to this indicator. In this sense, the criterion validity in its two dimensions (concurrent validity and predictive validity; American Psychological Association, 1974) might be availed by the results obtained in this research.

On the one hand, concurrent validity entails the existence of a statistical relationship between the ‘construct’ (indicator or taxonomy in this case) and a previously validated measure at a given moment in time. The results of the statistical tests carried out in this research indicate that, regardless of the underlying explanatory factors (which are not known), the taxonomy is not independent from the already validated and well established bibliometric indicators available at Journal Citation Reports.

On the other hand, predictive validity implies the existence of a statistical relationship between the construct and the value of an already validated construct in the future, hence serving the purpose of predicting its values. Although this type of validity is less strongly supported by the tests carried out in this research, it could be said that the crossvalidation procedure used in the classification tree offers a number of testing scenarios that, in principle, would not differ too much from future states of the indicators in the database. Also, some of the indicators included in this analysis are gathered in different time windows, and the relationship between the taxonomy categories and them does not apply to those depending on the most recent data only.

Limitations and further research

This study presents certain limitations. First, the delineation of the topic and a certain lack of consensus in previous studies regarding which topics belong to or fall outside the realm of sustainability science. To overcome this issue, a WoS category in Web of Science was used, although this does not imply a full coverage of the topic and the data source is known to show specific coverage issues that also affect the results presented here. Second, only one case study was performed previously using this indicator, although the evidence found in this new application of the indicator shows new empirical validity sources. Future research using part of the methodology used in this case might entail the use of the citing / cited methodology for delineating subject categories (in example, by identifying journals which papers cite and are cited mainly by papers in journals classified in WC other than that of the journal in which they are published, helping the refinement of the WC for analysis purposes) as well as for the analysis of the variability of the relationship between specialization and impact across fields.

Notes

The triple bottom line (TBL) considers the three parts of sustainability: social, environmental (or ecological) and economic.

Information of the launch of this WC available at the following link: http://wokinfo.com/media/pdf/wos5-22-1-external-release-notes.pdf. Accessed on 3 May 2020.

This data has been downloaded and processed by the IUNE Observatory it-staff.

Interdisciplinarity is traditionally defined as the integration of theories or methods from different scientific disciplines (Klein 1990).

Information of the scope of Sustainability Science. Retrieved from https://www.springer.com/journal/11625/aims-and-scope . Accessed 29 May 2020.

References

A Pandiella-Dominique, N Bautista-Puig, D De Filippo (2018) Mapping growth and trends in the category ‘Green and Sustainable Science and Technology’. In: 23rd International Conference on Science and Technology Indicators (STI 2018), September 12–14, Leiden, The Netherlands. Centre for Science and Technology Studies (CWTS).

Abramo, G., D’Angelo, C. A., & Di Costa, F. (2019). Diversification versus specialization in scientific research: Which strategy pays off? Technovation, 82, 51–57.

Academies, N. (2004). Committee on facilitating interdisciplinarity research, committee on science, engineering, and public policy (2004) Facilitating interdisciplinarity research. National Academies Washington: National Academy Press.

American Psychological Association, American Educational Research Association, & National Council on Measurement in Education (1974) Standards for educational & psychological tests. American Psychological Association.

Bark, R. H., Kragt, M. E., & Robson, B. J. (2016). Evaluating an interdisciplinarity research project: Lessons learned for organisations, researchers and funders. International Journal of Project Management, 34(8), 1449–1459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2016.08.004

Bautista-Puig, N. (2020). Unveiling the path towards sustainability: scientific interest at HEIs from a scientometric approach in the period 2008–2017 (Doctoral dissertation). https://e-archivo.uc3m.es/handle/10016/30095

Bautista-Puig, N., Mauleón, E., & Sanz-Casado, E. (2019). The role of universities in sustainable development (SD): The Spanish framework. In higher education and sustainability. CRC Press (pp 91–116).

Bettencourt, L. M., & Kaur, J. (2011). Evolution and structure of sustainability science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(49), 19540–19545.

Braun, T., & Schubert, A. (2003). A quantitative view on the coming of age of interdisciplinarity in the sciences 1980–1999. Scientometrics, 58(1), 183–189.

Broto, V. C., Gislason, M., & Ehlers, M. H. (2009). Practising interdisciplinarity in the interplay between disciplines: Experiences of established researchers. Environmental Science, 12, 922–933.

Brown, B. (2018). Interdisciplinarity research. European Review, 26(S2), S21–S29. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1062798718000248

Buter, R. K., & Van Raan, A. F. J. (2013). Identification and analysis of the highly cited knowledge base of sustainability science. Sustainability Science, 8(2), 253–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-012-0185-1

Castellani, T., Pontecorvo, E., & Valente, A. (2016). Epistemic consequences of bibliometrics-based evaluation: Insights from the scientific community. Social Epistemology, 30(4), 398–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2015.1065929

Davé, A., Hopkins, M., Hutton, J., Krčál, A., Kolarz, P., Martin, B., Nielsen, K., Rafols, I., Rotolo, D., Simmonds, P., & Stirling A. (2016). Landscape review of interdisciplinarity research in the UK. Report to HEFCE and RCUK by Technopolis and the Science Policy Research Unit (SPRU), University of Sussex

De Filippo, D., & Serrano-López, A. E. (2018). From academia to citizenry. Study of the flow of scientific information from projects to scientific journals and social media in the field of “Energy saving.” Journal of Cleaner Production, 199, 248–256.

Digital Science (2016) Interdisciplinarity research: Methodologies for identification and assessment https://www.mrc.ac.uk/documents/pdf/assessment-of-interdisciplinarity-research/

Disterheft, A., Caeiro, S., Azeiteiro, U. M., & Leal Filho, W. (2013). Sustainability science and education for sustainable development in universities: a way for transition. In: Sustainability assessment tools in higher education institutions Springer, Cham (pp 3–27)

Fang, X., Zhou, B., Tu, X., Ma, Q., & Wu, J. (2018). What kind of a science is sustainability science? An evidence-based reexamination. Sustainability, 10(5), 1478. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10051478

Holdren, J. P. (2008). Science and technology for sustainable well-being. Science, 319(5862), 424–434.

Huang, Y., Zhang, Y., Youtie, J., Porter, A. L., & Wang, X. (2016). How does national scientific funding support emerging interdisciplinarity research: A comparison study of big data research in the US and China. PLoS ONE, 11(5), e0154509.

Huutoniemi, K., Klein, J. T., Bruun, H., & Hukkinen, J. (2010). Analyzing interdisciplinarity: Typology and indicators. Research policy, 39(1), 79–88.

Jerneck, A., Olsson, L., Ness, B., Anderberg, S., Baier, M., Clark, E., & Persson, J. (2011). Structuring sustainability science. Sustainability Science, 6(1), 69–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-010-0117-x

Kajikawa, Y., & Mori, J. (2009). Interdisciplinarity research detection by citation indicators. IEEM 2009 – In: IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management, (pp 84–87). https://doi.org/10.1109/IEEM.2009.5373422

Kajikawa, Y., Tacoa, F., & Yamaguchi, K. (2014). Sustainability science: the changing landscape of sustainability research. Sustainability Science, 9(4), 431–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-014-0244-x

Klein, J. T. (1990). Interdisciplinarity: History, theory, and practice. USA: Wayne state University Press.

Lam, J. C. K., Walker, R. M., & Hills, P. (2014). Interdisciplinarity in sustainability studies: A Review. Sustainable Development, 22(3), 158–176. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.533

Larivière, V., & Gingras, Y. (2010). On the relationship between interdisciplinarity and scientific impact. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 61(1), 126–131.

Larivière, V., Haustein, S., & Börner, K. (2015). Long-distance interdisciplinarity leads to higher scientific impact. PLoS ONE, 10(3), e0122565.

Lee, S., & Bozeman, B. (2005). The impact of research collaboration on scientific productivity. Social studies of science, 35(5), 673–702.

Leydesdorff, L. (2007). Mapping interdisciplinarity at the interfaces between the science citation index and the social science citation index. Scientometrics, 71(3), 391–405.

Leydesdorff, L., & Ivanova, I. (2020). The measurement of “interdisciplinarity” and “synergy” in scientific and extra-scientific collaborations. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24416.

Leydesdorff, L., & Rafols, I. (2011). Indicators of the interdisciplinarity of journals: Diversity, centrality, and citations. Journal of Informetrics, 5(1), 87–100.

Leydesdorff, L., & Rafols, I. (2012). Interactive overlays: A new method for generating global journal maps from Web-of-Science data. Journal of Informetrics, 6(2), 318–332.

Lubchenco, J. (1998). Entering the century of the environment: a new social contract for science. Science, 279(5350), 491–497.

Lyall, C., Bruce, A., Marsden, W., & Meagher, L. (2013). The role of funding agencies in creating interdisciplinarity knowledge. Science and Public Policy, 40(1), 62–71.

Mañana-Rodríguez, J. (2017). Disciplinarity and interdisciplinarity in citation and reference dimensions: knowledge importation and exportation taxonomy of journals. Scientometrics, 110(2), 617–642.

Martens, P. (2006). Sustainability: Science or fiction? Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 2(1), 36–41.

Morillo, F., Bordons, M., & Gómez, I. (2003). Interdisciplinarity in science: A tentative typology of disciplines and research areas. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and technology, 54(13), 1237–1249.

Mugabushaka, A. M., Kyriakou, A., & Papazoglou, T. (2016). Bibliometric indicators of interdisciplinarity: The potential of the Leinster-Cobbold diversity indices to study disciplinary diversity. Scientometrics, 107(2), 593–607. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-1865-x

Nilles, J. M. (1976). Interdisciplinarity policy research and the universities. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 2, 79–84.

Nučič, M. (2012). Is sustainability science becoming more interdisciplinarity over time? Acta Geographica Slovenica, 52(1), 215–236.

Olensky, M., Schmidt, M., & Van Eck, N. J. (2016). Evaluation of the citation matching algorithms of CWTS and iFQ in Comparison to the Web of Science. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 67(10), 2550–2564. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23590

Rafols, I., & Meyer, M. (2010). Diversity and network coherence as indicators of interdisciplinarity: case studies in bionanoscience. Scientometrics, 82(2), 263–287.

Roy, E. D., Morzillo, A. T., Seijo, F., Reddy, S. M. W., Rhemtulla, J. M., Milder, J. C., & Martin, S. L. (2013). The elusive pursuit of interdisciplinarity at the human-environment interface. BioScience, 63(9), 745–753. https://doi.org/10.1525/bio.2013.63.9.10

Schoolman, E. D., Guest, J. S., Bush, K. F., & Bell, A. R. (2012). How interdisciplinarity is sustainability research? Analyzing the structure of an emerging scientific field. Sustainability Science, 7(1), 67–80.

Sundaram, K., Warren, J., Anis, H. K., Klika, A. K., & Piuzzi, N. S. (2019). Publication integrity in orthopaedic journals: the self-citation in orthopaedic research (SCOR) threshold. European Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology, 30(4), 629–635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-019-02616-y

Thorén, H., & Persson, J. (2013). The philosophy of interdisciplinarity: Sustainability science and problem-feeding. Journal for General Philosophy of Science, 44(2), 337–355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10838-013-9233-5

Van Noorden, R. (2015). Interdisciplinarity research by the numbers. Nature, 525(7569), 306–307. https://doi.org/10.1038/525306a

Wang, J., Thijs, B., & Glänzel, W. (2015). Interdisciplinarity and impact: Distinct effects of variety, balance, and disparity. PLoS ONE, 10(5), e0127298.

Wang, Q., & Schneider, J. W. (2019). Consistency and validity of interdisciplinarity measures. Quantitative Science Studies, 2015, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00011

Weinberg, A. M. (1961). Impact of large-scale science on the United States. Science, 134(3473), 161–164.

Yegros-Yegros, A., Rafols, I., & D’Este, P. (2015). Does interdisciplinarity research lead to higher citation impact? the different effect of proximal and distal interdisciplinarity. PLoS ONE, 10(8), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0135095

Zhang, L., Rousseau, R., & Glänzel, W. (2016). Diversity of references as an indicator of the interdisciplinarity of journals: Taking similarity between subject fields into account. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 67(5), 1257–1265.

Zurita, G., Merigó, J. M., & Lobos-Ossandón, V. (2016). A bibliometric analysis of journals in educational research. Lecture Notes in Engineering and Computer Science, 2223, 403–408.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Gävle.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bautista-Puig, N., Mañana-Rodríguez, J. & Serrano-López, A.E. Role taxonomy of green and sustainable science and technology journals: exportation, importation, specialization and interdisciplinarity. Scientometrics 126, 3871–3892 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-03939-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-03939-6