Abstract

There is an ongoing debate whether police officers should be allowed to wear tattoos or piercings on visible parts of the body or not. One argument often brought forward against it is that such body modifications would cue negative evaluations of officers by citizens that would impede officers’ fulfillment of their duties. Yet, empirical evidence for this claim is missing. The present research aims to close this gap by examining how citizens perceive police officers with tattoos and piercings. In an experiment, participants saw edited photographs of police officers with and without tattoos (study 1) or piercings (study 2). They rated each officer regarding communion, agency, likability, respect, and threat. We found that, as expected, police officers with tattoos and piercings were perceived as less trustworthy and less competent, were liked somewhat less, and triggered higher perceptions of threat. In addition, police officers with tattoos (but not with piercings) were perceived as less friendly and more assertive. Regarding respect, we found no differences between officers with and without body modifications. While our empirical results cannot answer the societal and political question whether police officers should be allowed to wear tattoos and piercings or not, experimental psychological research can contribute to the respective discussions by providing an empirical basis. Our findings further have important theoretical implications, as the opposing effects on competence and assertiveness underline the importance of distinguishing between these two facets of agency in research on social perception and judgment.

Similar content being viewed by others

In 2013, a German police officer officially requested permission to get an “aloha” tattoo on his forearm. The authorities declined his request and he appealed to the administrative court, arguing that the tattoo was an expression of his personality, a right protected by the German constitution (Article 2, Basic Constitutional Law of the Federal Republic of Germany). The appeal was rejected under the reasons that police officers are obligated to observe certain rules to ensure a unified appearance (for German police officers, e.g., Henrichs 2002) and that visible tattoos may negatively affect the regard for and neutrality of police officers. The police officer again appealed against that decision and in 2020, in a third instance decision, the court ultimately rejected the officer’s request to have the right to get an “aloha” tattoo (Bayerische Staatskanzlei 2016; Spiegel 2020). In Germany (where the current data were collected), but also in many other countries like the USA and the UK, body modification policies for officers exist. However, there are also mixed regulations within national police institutions that arouse confusion and irritation among police officers (e.g., McMullen and Gibbs 2019; Schäfer et al. 2019). Thus, the “aloha” example illustrates a current discussion in society (The Guardian 2016; Spiegel 2018): Should police officers be allowed to have tattoos on visible parts of their body like the forearm or not?

While some aspects of this question involve purely legal matters (e.g., whether limits to police officers’ self-expression are unconstitutional), what (social) psychology can contribute to the discussion is an answer to the rather practical question how such body modifications affect the perception of officers by citizens, which may in turn affect officers’ ability to perform their duties. On one hand, tattoos are historically associated with specific, often negatively connotated, marginalized groups and milieus (e.g., former prisoners, punks, gang members, motorcyclists, sailors, soldiers; Adams 2012; DeMello 2000; Schildkrout 2004; Wohlrab et al. 2007). This may lead to the assumption that police officers with tattoos trigger a negative and threatening impression. On the other hand, today, tattoos are common in all classes of society and occupational groups (Stirn et al. 2006). They are rather considered to be an expression of individuality (Rohr 2009). Stated in numbers, 30% of individuals in the USA have at least one tattoo and the share rises in younger age groups (Ipsos 2019). In Germany, 12% of the population are tattooed (BfR-Verbrauchermonitor 2018). However, growing numbers of tattoos may not necessarily prevent negative effects of such body modifications, as stereotypes generally change very slowly (Vandekerckhove 2005).

The present research aims to add an empirical basis for discussions of whether police officers should be allowed to have tattoos and piercings on visible parts of the body as an expression of their individuality or if this should be forbidden to avoid a negative evaluation of officers by citizens. We therefore experimentally tested how citizens evaluate police officers with tattoos (study 1) and with piercings (study 2).

Evaluation of Tattooed Individuals

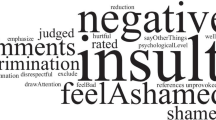

Despite the increased prevalence of tattoos, several studies found that tattooed individuals are still a stigmatized group, stereotypically associated with various negative attributes. They are, for instance, perceived as sexually promiscuous, impulsive, rebellious, aggressive, thrill-seeking, dangerous, deviant, dishonest, less trustworthy, less generous, less friendly, less caring, less intelligent, less attractive, less athletic, less artistic, and as more likely to commit crimes (Baumann et al. 2016; Burgess and Clark 2010; Dean 2010; Degelman and Price 2002; Durkin and Houghton 2000; Funk and Todorov 2013; Hawkes et al. 2004; Resenhoeft et al. 2008; Swami and Furnham 2007; Timming et al. 2017; Wohlrab et al. 2009; Zeiler and Kasten 2016). Visible tattoos also affect the attitudes towards tattooed individuals in the workplace. While consumers tend to view visible tattoos on blue-collar workers as appropriate, they are seen as inappropriate on white-collar workers (Dean 2010). Importantly, people not only hold negative attitudes towards individuals with tattoos on special, conspicuous locations like the neck that can be associated with facial disfigurement and criminal gang membership (Zestcott et al. 2017), but also towards individuals with visible tattoos on more common locations like the arm, chest, or leg (Zestcott et al. 2018).

Evaluation of Pierced Individuals

As with tattoos, the popularity of facial and body piercings has increased over the past years. Indeed, piercings of the earlobe are generally accepted in today’s western societies, called earrings instead of piercings and not even counted in piercing statistics. Stated in numbers, 14% of individuals in the USA have at least one piercing (Statisticbrain 2017). In Germany, statistics are comparable and the share again rises in younger age groups (Universität Leipzig 2017). Yet, despite the apparent mainstreaming of piercings, research on the social perception of pierced individuals remains scarce and is much scarcer than research on the perception of tattooed individuals.

However, as in the tattoo studies, research has shown that pierced individuals are stereotypically associated with numerous negative attributes. For example, they are perceived as less attractive, less agreeable, less sociable, less extraverted, of more questionable character, less credible, less trustworthy, less conscientious, less competent, less intelligent, and more neurotic (Forbes 2001; Martino 2008; McElroy et al. 2014; Seiter and Sandry 2003; Swami et al. 2012). Moreover, multiple piercings intensified the negative effects (Swami et al. 2012).

In sum, individuals with tattoos and piercings are generally evaluated rather negatively and some of the stereotypes, like criminality and questionable character, are particularly incompatible with the representative goals of police officers. However, no study has, as far as we know, experimentally tested how tattoos and piercings affect citizens’ perceptions of police officers. We are only aware of one study by Thielgen et al. (2020), who investigated how prison inmates perceive tattooed police officers and tattooed individuals without uniform. Without tattoos, targets were rated more positively in uniform than in civilian clothing. With tattoos, there was no such uniform effect. However, it remains open how citizens perceive police officers in uniform with and without tattoos or piercings. Moreover, empirical studies analyzing the evaluation of tattooed and pierced individuals have used a myriad of different individual adjectives, making it difficult to interpret the findings in a systematic way. We suggest that using the framework of the basic dimensions of social perception can help to systemize research findings and understand the bigger picture behind them.

Basic Dimensions of Social Perception: Communion and Agency

Research has consistently revealed two basic dimensions of social perception, communion and agency (reviews: Abele and Wojciszke 2014; Cuddy et al. 2008; Paulhus and Trapnell 2008). While communion refers to qualities relevant for the establishment and maintenance of social relationships, such as being friendly or fair, agency refers to qualities relevant for goal-attainment, such as being ambitious or capable. Communion and agency capture the two recurring challenges of human life: belonging to social groups (“getting along”) and pursuing individual goals (“getting ahead”; Hogan 1982; Ybarra et al. 2008).

A more recent insight is that both basic dimensions can be characterized by two closely related but distinguishable facets each (Abele et al. 2016). The communal facets are warmth and morality, as “getting along” requires both friendliness (warmth) and trustworthiness (morality). The agentic facets are competence and assertiveness, as “getting ahead” requires both skill (competence) and motivation/volition (assertiveness). Regarding communion, research has shown that morality plays a more central role in the evaluation of groups and individuals than warmth (Abele and Hauke 2019; Hauke and Abele 2019, 2020a, b; Leach et al. 2007; review: Brambilla and Leach 2014). Regarding agency, first empirical evidence shows that ascribed status is more related to assertiveness than to competence (Carrier et al. 2014; Louvet et al. 2019) as is self-esteem (Abele et al. 2016; Hauke and Abele 2020a, b). In short, communion and agency with their two facets each have proven to be a useful conceptualization of how we perceive others.

Many of the individual adjectives used in previous research on the evaluation of tattooed and pierced individuals can be assigned to the communal and agentic facets: That tattooed and pierced individuals are perceived as less friendly, caring, warm, generous, agreeable, and social can be summarized as a low evaluation in warmth. That they are perceived as less trustworthy and credible as well as more dishonest, criminal, and of questionable character corresponds to a low evaluation in morality. The perception of tattooed and pierced individuals as less intelligent and less competent stands for a low evaluation on competence, and perceptions as more rebellious and aggressive as well as associations with strong and assertive groups like soldiers indicate high assertiveness.

It seems obvious that the four communal and agentic facets are crucial for successful policing, above all competence, assertiveness, and morality. In the following description of our research project, we will use the terms trustworthiness, friendliness, competence, and assertiveness, as for police officers, we consider trustworthiness and friendliness to be the most important aspects of the morality and the warmth facet, respectively.

Further Reactions: Likability, Respect, and Threat

The perception of others regarding their communion and agency influences further reactions like likability, respect, and threat (Brambilla et al. 2012; Wojciszke et al. 2009). Likability can be understood as a response reflecting personal interests and preferences, while respect can be understood as a response which reflects high regard of and deference to a person (Kiesler and Goldberg 1968; but see Simon 2007). Likability depends on the communal qualities of a person, whereas respect depends on their agentic qualities (Wojciszke et al. 2009).

Another reaction, besides likability and respect, that we consider relevant for the present research question is how much citizens perceive police officers as a source of threat. The task of police officers is, amongst others, to help and secure citizens. Since a positive attitude towards authorities is a key prerequisite for their effective and efficient functioning (Tyler and Degoey 1996), this task would be impeded if citizens were afraid of police officers. In other words, if citizens perceive police officers as threatening, they might refrain from seeking their assistance. Threat perceptions depend on perceived negative morality (Brambilla et al. 2012). In sum, these further reactions based on perceived communion and agency are also crucial for successful policing—respect and threat perceptions in particular.

Present Research and Hypotheses

Previous research has shown that tattooed and pierced individuals are viewed as possessing a range of negative traits and attributes (see above). An open but highly important question is whether the same is true for tattooed and pierced police officers wearing uniforms. We examined experimentally how citizens evaluate police officers with body modifications: in study 1, we tested the effects of tattoos, in study 2, we tested the effects of piercings. In both studies, we showed participants edited photographs of male and female police officers with and without tattoos/piercings and asked them to rate the officers regarding friendliness, trustworthiness, competence, and assertiveness. Moreover, participants indicated how much they liked, respected, and felt threatened by the respective police officer. Based on previous research, we made the following predictions:

Citizens perceive police officers with tattoos/piercings as…

-

Hypothesis 1: less friendly

-

Hypothesis 2: less trustworthy

-

Hypothesis 3: less competent

-

Hypothesis 4: more assertive

…than police officers without tattoos/piercings.

Threat is linked to negative morality (Brambilla et al. 2012), e.g., low trustworthiness (Hypothesis 2). In addition, previous research showed that individuals with body modifications are perceived as dangerous and criminal, and tattooed individuals are stereotypically associated with dangerous groups like prisoners and gang members. We thus expect the following:

-

Hypothesis 5: Citizens feel more threatened by police officers with tattoos/piercings than by police officers without tattoos/piercings.

Since likability is linked to communion (Wojciszke et al. 2009) and police officers with body modifications should be perceived as less friendly and trustworthy (hypotheses 1–2), we predict that…

-

Hypothesis 6: citizens perceive police officers with tattoos/piercings as less likeable than police officers without tattoos/piercings.

Respect is linked to agency (Wojciszke et al. 2009). Since we anticipate that police officers with body modifications are perceived as lower on competence (hypothesis 3), but higher on assertiveness (hypothesis 4), we have no clear predictions regarding respect of tattooed and pierced police officers. We will analyze this reaction in an explorative way.

We report how we determined our sample size, all data exclusions (if any), all manipulations, and all measures in the study. Our data are available at https://osf.io/c3emk/?view_only=57dd267ab06d4f838a56fa28726548e4.

Study 1: Tattoos

Method

Participants and Design

As participants, we recruited random passers-by in a pedestrian zone in the center of a medium-sized German city and asked if they would take part in a study about the ‘perception of police officers’. They received candy as a reward. An a priori power analysis indicated that at least 97 participants were needed to detect a small to medium effect (d = 0.30) in a dependent t test with a power of 1–β = 0.90 and α = 0.05 (G*Power; Faul et al. 2007). The final sample consisted of 130 participants (84 women, 45 men, 1 non-response). The mean age was 31.39 years (SD = 15.01, range: 18–78 years). Most participants were students (54.3%) or employed (31.5%). Concerning tattoos, 21.5% of participants indicated to have at least one. The political orientation of the participants was center-left on average (M = 3.32, SD = 1.19, on a scale from 1 = left to 7 = right), a pattern commonly found in German samples (European Social Survey Round 9 2018: M = 4.39, SD = 1.91, on a scale from 0 = left, 10 = right). Previous personal experiences with the police were described as rather positive by the majority of the sample (M = 4.75, SD = 1.51, on a scale from 1 = negative to 7 = positive). The study had a 2 (tattoo: no vs. yes) × 2 (gender of police officers: male vs. female) design with repeated measures on both factors.

Materials and Procedure

After giving informed consent, participants completed a paper-pencil questionnaire. We showed them photographs of four different police officers and asked them to rate each officer regarding their communion, agency, threat, likability, and respect (details see below). Participants rated each individual officer on all dependent variables before moving on to rating the next officer. After these ratings, participants provided socio-demographic information. Finally, a two-step debriefing procedure followed: first, participants were asked if they had any comments on the study or any ideas what the aim of the study was. Then, they were fully debriefed and thanked.

Photographic Material

We used photos of four different police officers (two male, two female) who were students at the State Police Academy of Rhineland-Palatinate in Germany. All wore uniforms, had a neutral facial expression, and the same body posture (Fig. 1). Tattoos were placed on the left forearms of the officers with an image-editing software. Participants always first rated two male officers followed by two female officers. The second and third officer always wore a tattoo, while the first and forth officer did not. We counterbalanced between participants which officer appeared in which position and therefore did or did not have a tattoo (as illustrated in Fig. 1).

Dependent Variables

The communal and agentic facets were measured with an adapted version of the Agency-Communion-Inventory by Abele et al. (2016). Each facet was measured with two items (“friendly” and “warm” [friendliness], “fair” and “trustworthy” [trustworthiness], “intelligent” and “competent” [competence], “self-confident” and “assertive” [assertiveness]). The items were presented in a bipolar format with a 7-point Likert-scale (e.g., from − 3 = very unfriendly to 3 = very friendly). The negative traits were on the left side (coded as 1) of the scale while the positive traits were on the right side (coded as 7). Participants were asked to indicate how much they thought the respective traits applied to the police officer depicted in the photo.

We also measured threat, likability, and respect on bipolar 7-point scales with two items each (“threatening” and “frightening” [threat], “likable” and “pleasant” [likability], “commands respect” and “highly regarded” [respect]). Means, standard deviations, and reliabilities (Cronbach’s alpha) of all dependent variables are reported in Tables 1 and 2.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 shows the correlations of the dependent variables. Regarding the correlations of the further reactions with the agentic and communal facets, likability was, as expected, most strongly linked to trustworthiness and friendliness. Respect was most strongly linked to assertiveness and competence. Threat was only linked to assertiveness.

Hypothesis Testing

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics for the dependent variables and the results of the dependent-measures t tests that we calculated to test our hypotheses. All hypotheses were supported: participants perceived police officers with tattoos as less friendly, less trustworthy, and less competent. They also liked police officers with tattoos somewhat less than their counterparts without tattoos. In contrast, participants perceived tattooed police officers as more assertive and more threatening than police officers without tattoos.

Exploratory Analyses

For all dependent measures t tests that we calculated for additional exploratory analyses in studies 1 and 2, we adjusted the α-level by the Bonferroni-Holm correction (Holm 1979) to avoid alpha inflation. We used the online calculator by Hemmerich (2016).

Respect

Participants indicated equal respect for police officers with and without tattoos (Table 2).

Interaction Effects with Officer Gender

Agency and communion are also linked to traditional gender stereotypes with communal traits being seen as stereotypically female and agentic traits as stereotypically male (Abele and Wojciszke 2014; Donnelly and Twenge 2017). We therefore exploratively analyzed our data regarding interaction effects with officer gender. We first calculated a 2 (gender of police officers: male vs. female) × 2 (tattoo: no vs. yes) repeated measures ANOVA for each dependent variable separately. These ANOVAs showed no significant interaction effects between officer gender and tattoo status for friendliness, competence, and likability, all Fs < 1.22, all ps > 0.272, all ηp2s < 0.010. However, we did find significant interaction effects for trustworthiness, F(1,129) = 4.89, p = 0.029, ηp2 = 0.037, assertiveness, F(1, 129) = 8.21, p = 0.005, ηp2 = 0.060, threat, F(1,129) = 12.13, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.086, and respect, F(1,129) = 8.33, p = 0.005, ηp2 = 0.061.

We therefore again calculated repeated-measures t tests for these four dependent variables, but this time separately for male and female police officers. For all four variables we found significant differences for male, but not for female officers (Table 3). This means that the hypothesized effects on trustworthiness, assertiveness, and threat were stronger and only statistically significant for male officers. In addition, participants tended to respect tattooed male officers more. In sum, as predicted, tattoos caused a more negative perception of police officers, even though, unexpectedly, some of these effects were stronger for male than for female officers.

Study 2: Piercings

In study 2, we examined the perception of police officers with and without piercings. The method was similar to study 1 and we tested equivalent hypotheses.

Method

Participants and Design

As participants, we again recruited random passers-by in a pedestrian zone in the center of a medium-sized German city for a study about the ‘perception of police officers’. They again received candy as a reward for participation. A power analysis with G*Power (Faul et al. 2007) indicated at least 151 participants to achieve a power of 90% to detect a small effect (d = 0.24 which was the smallest significant effect in study 1) with a 0.05 alpha criterion in a dependent t-test. In total, 160 people took part in the study. However, we had to exclude the data of three participants: One participant was a police officer himself and two had already taken part in Study 1 on tattoos. Thus, the final sample consisted of 157 participants (99 women, 56 men, 2 non-responses). The mean age was 37.99 years (SD = 17.11, range: 18–77 years). Most participants were students (31.2%) or employed (53.9%). Concerning piercings, 9.6% of participants indicated to have at least one piercing and 5.7% of participants indicated that they used to have one but did not have it any more. The political orientation of the participants was again center-left on average (M = 4.05, SD = 1.45, on a scale from 1 = left to 9 = right). Personal experiences with the police were described as rather positive by the majority of the sample (M = 6.59, SD = 1.99, on a scale from 1 = negative to 9 = positive). The study had a 2 (piercing: no vs. yes) × 2 (gender of police officers: male vs. female) design with repeated measures on both factors.

Materials and Procedure

As in study 1, participants first gave informed consent. They then sequentially rated four police officers regarding communion, agency, threat, likability, and respect (details see below). Next, participants gave their explicit attitude on police officers wearing piercings, provided socio-demographic information, were debriefed in the same two-step procedure as in Study 1, and thanked.

Photographic Material

We used photos of four different police officers (two male, two female). All officers wore uniforms including bullet proof vests and walkie-talkies, had a neutral facial expression, and the same body posture (Fig. 2). We used two different piercings: a lip piercing and an eyebrow piercing. Both were placed in the face of the respective officers with an image-editing software. Participants again first rated a male police officer without a piercing, then a male officer with a piercing, followed by a female officer with a piercing, and finally, a female officer without piercing. Which officer appeared in which position, and therefore with versus without a piercing, was again counterbalanced between participants. In addition, we varied between participants which of the two pierced officers wore a lip piercing and which one wore an eyebrow piercing, resulting in four different picture sets that participants were assigned to randomly.

Dependent Variables

The communal and agentic facets as well as threat, likability, and respect were measured with the same instruments as in study 1. Means, standard deviations, and reliabilities (Cronbach’s alpha) of all dependent variables are reported in Tables 4 and 5.

Explicit Attitudes Towards Police Officers Wearing Piercings

For exploratory reasons, we also included two separate items to measure participants’ explicit attitudes towards police officers wearing piercings. The first item was “According to your experience, how irritating are facial piercings of police officers?” on a scale from 1 = not irritating at all to 4 = strongly irritating (Niedersächsische Polizei-Fachhochschule 2001), the second was “What is your attitude towards piercings of police officers?” on a scale from 1 = acceptable to 6 = not acceptable (Birk et al. 2001).

Results

We analyzed the data in a parallel fashion to study 1.

Preliminary Analyses

Regarding the correlations between our dependent variables (Table 4), likability was, as expected, most strongly linked to trustworthiness and friendliness, but also to competence. Respect was most strongly linked to assertiveness and competence. Threat was this time, as expected, only linked negatively to trustworthiness.

Hypothesis Testing

As shown in Table 5, 4 out of 6 hypotheses were supported: participants perceived police officers with piercings as less trustworthy and less competent. They liked police officers with piercings somewhat less than their counterparts without piercings and perceived pierced officers as more threatening. In contrast to study 1, we found no significant differences for friendliness or assertiveness. Descriptively, the means for pierced and non-pierced officers differed in the direction of our hypotheses, but only slightly.

Exploratory Analyses

Respect

Participants indicated equal respect for police officers with and without piercings (Table 5).

Interaction Effects with Officer Gender

We found no significant interaction effects between officer gender and piercing status for 6 out of the 7 dependent variables, all Fs(1, 156) < 3.24, all ps > 0.073, all ηp2s < 0.021. The only significant interaction was on trustworthiness, F(1, 156) = 4.65, p = 0.033, ηp2 = 0.029. Participants perceived male pierced officers as considerably less trustworthy, but female pierced officers as only somewhat less trustworthy than their counterparts without piercings (see Table 3).

Explicit Attitudes

Participants indicated that they were not particularly irritated by piercings of police officers (M = 2.36, SD = 1.08), comparison with the neutral scale mean of 2.5: t(152) = −1.61, p = 0.110, d = −0.18. Moreover, they saw them as rather acceptable (M = 2.90, SD = 1.77), comparison with the neutral scale mean of 3.5: t(152) = −4.19, p < 0.001, d = −0.48. That is, participants explicitly stated rather positive attitudes towards body modifications in police officers while at the same time judging police officers with facial piercings more negatively than officers without piercings.

General Discussion

Legal courts as well as public discussions have repeatedly grappled with the question whether police officers should be allowed to wear visible body modifications such as tattoos. Yet, to this date, these discussions and decisions have rarely been informed by empirical evidence. Accordingly, the main goal of this research was to (begin to) close this research gap. In two studies, participants were shown edited photographs of police officers with and without tattoos/piercings and rated them with regard to friendliness, trustworthiness, competence, and assertiveness. Moreover, participants indicated how much they liked, respected, and felt threatened by the respective police officers. Extending previous findings on the negative perception of individuals with body modifications (e.g., for tattoos: Dean 2010; Zestcott et al. 2017, 2018; for piercings: McElroy et al. 2014; Swami et al. 2012), our results clearly showed that, as expected, police officers with tattoos and piercings are also evaluated more negatively. Specifically, police officers with body modifications were perceived as less trustworthy and less competent by citizens compared to their counterparts without tattoos and piercings. Moreover, they were liked somewhat less and they triggered higher perceptions of threat. Police officers with tattoos (but not with piercings) were also perceived as less friendly and more assertive. Regarding respect, we found no differences between officers with and without body modifications. Overall, results were similar (but not identical) across studies and the effect sizes ranged from small to medium.

The major strengths of the present research are its experimental design employing standardized materials and its theoretical grounding in the well-established research on basic dimensions of social perception. More specifically, the presented photographs of officers only differed in the presence of tattoos/piercings, which allows causal inferences from differences in evaluation to the respective body modification. Moreover, we measured the perception of officers with and without body modifications as dependent variables instead of only explicitly asking for citizens’ opinion about tattooed and pierced police officers. In this way, we could reduce tendencies for socially desirable responding. In fact, even though participants explicitly stated rather positive attitudes towards pierced officers, they rated them more negatively than officers without piercings. Furthermore, by applying a basic dimensions approach, we gathered comprehensive and more systematic insights into how officers with body modifications are perceived. Interestingly, in addition to their practical implications, our results also have important theoretical implications for research on social perception. We turn to these latter implications first.

Implications for Social Perception Research

The present research offers important theoretical insights regarding research on social perception. Even though competence and assertiveness are facets of the same dimension, namely agency, we found an opposing effect of tattoos on these facets in study 1: Tattoos decreased perceived competence but increased perceived assertiveness. This demonstrates that it is not only useful to distinguish between the facets of communion and agency, it is sometimes even necessary. Previous research has, for example, shown that trustworthiness (morality) is even more important than friendliness (warmth) for positive other-evaluation (Abele and Hauke 2020; Brambilla and Leach 2014), but still both communal facets are positively related to it. Likewise, previous research has shown that assertiveness is even more important than competence for positive self-esteem (Abele et al. 2016; Hauke and Abele 2020a, b) or for status perception (Carrier et al. 2014; Louvet et al. 2019), but still both agentic facets are positively related to them. Contrasting effects in opposing directions for two facets of the same basic dimension have been discussed theoretically, but have rarely been shown empirically. In fact, we are only aware of one such set of studies. Also for the agency dimension, Methner and colleagues (2020) recently found that acknowledging criticism can cause public figures to appear more competent but less assertive. In our study 1, tattoos decreased the perception of competence, but increased the perception of assertiveness. This could be explained by the circumstance that tattoos are associated with groups that are considered as assertive (like sailors and soldiers) but at the same time also with groups that are not compatible with the role of police officers (like prisoners and gang members who rather commit than solve crimes; Adams 2012; DeMello 2000; Schildkrout 2004; Wohlrab et al. 2007). This incompatibility could decrease the perception of competence. If we would have simply measured agency as a single dimension, the effect of tattoos would have been completely disguised by these opposing effects.

Interaction Effects with Officer Gender

In some previous studies, the negative stigma associated with facial piercings was found equally for male and female pierced individuals (McElroy et al. 2014). Other research found that pierced men were rated more negatively than pierced women (Swami et al. 2012). Again, others found that perceivers viewed tattooed women more negatively than men (Swami and Furnham 2007).

In our research, we found the same results for female and male officers for most of the dependent variables across both studies. However, we did find that the negative effect of tattoos and piercings on trustworthiness was stronger for male than for female officers. Moreover, only male tattooed officers (but not female tattooed officers) were perceived as significantly more assertive, more threatening, and tended to be respected more. These stronger effects of tattoos for men could be explained by a different connotation of tattoos for the two sexes. On one hand, the stigmatized milieus which are a basis for the negative stereotypes about tattooed individuals are stereotypically male (e.g., prisoners, gang members). On the other hand, body modifications are perhaps more socially accepted for women who use make-up and wear ear rings regularly. Importantly though, the gender differences found in the present research remain explorative and the explanations for them are post hoc. Thus, they should be critically tested in future studies.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

A remaining question is the generalizability of our results. The samples we used were opportunity samples and not representative in terms of gender, age, and education. Our participants in both studies were more often women, rather young, and highly educated. Moreover, our participants were rather left-wing oriented, but a center-left political orientation is commonly found in representative German samples. For estimating how these four sample characteristics could have influenced our results, we scrutinized previous research regarding perceiver effects. The gender of the perceiver did not affect attitudes toward tattooed individuals (Baumann et al. 2016; Degelman and Price 2002; Dickson et al. 2014; Hawkes et al. 2004; Zestcott et al. 2017). However, age (Deal et al. 2010; Dean 2010; Lin 2002; Zestcott et al. 2018), being a student, (Dale et al. 2009), and a left-wing political orientation (Swami et al. 2012; Zestcott et al. 2018) have all been associated with a more positive evaluation of tattooed and/or pierced individuals. Thus, if anything, the negative effects found in our relatively young samples with high proportions of students and with left-wing oriented people would have probably been stronger in a representative sample or in more right-wing oriented parts of society. The same goes for tattoo status, as compared to the general population, a higher proportion of our participants was tattooed themselves and in past research, own tattoos were sometimes related to more favorable attitudes towards tattooed individuals (e.g., Burgess and Clark 2010; Dickson et al. 2014; Hawkes et al. 2004; Zestcott et al. 2017, 2018; but see Dean 2010; Degelman and Price 2002). Piercings were about as common as in representative samples.

Another limitation of the present research is that our data only allows reliable statements for young White police officers with rather extensive “tribal tattoos” on the forearm and with lip and eyebrow piercings. This is important, as empirical evidence suggests that stereotypes and prejudice toward tattooed individuals may vary according to the nature of the tattoo (e.g., type, size, number). The “aloha” tattoo desired by the German police officer mentioned in the Introduction could have very different effects than the tattoos used in the present research. So called “contemporary” tattoos, such as images of dolphins or hearts, are rated as more modern, friendly, cute, happy, and peaceful and as less aggressive, bold, and bad than “traditional” tattoos, such as thick blacked lined tribal patterns (Burgess and Clark 2010). As a consequence, previous research found more negative attitudes towards individuals with a tribal tattoo than towards individuals with a heart tattoo. However, the overall attitude was still negative for the heart tattoo (Zestcott et al. 2017). Future studies should test the effects of officers from different age, racial, and ethnic groups and of different types of tattoos and piercings.

Implications for Appearance Guidelines for Police Officers

Beyond the theoretical implications, our results have important practical implications regarding the appearance of police officers and their perception by citizens. The most consistent and robust finding of the present studies was that police officers with tattoos and piercings were perceived more negatively. Specifically, they were consistently seen as less trustworthy, less competent, and more threatening, all perceptions that are likely to negatively affect interactions between police and citizens. However, it would be an overinterpretation of our results to claim that they provide a clear “No” to the question whether police officers should be allowed to have tattoos and piercings on visible parts of the body. This has several reasons. First, the negative effects of body modifications were of small to medium effect sizes and the level of the positive (negative) outcome variables always stayed above (below) the neutral scale mean. (But note that as discussed above, our samples reflect a rather conservative test of the negative effects of tattoos and piercings and the true effect sizes in the population may be higher). Second, as discussed in the limitations section, it is not clear whether the negative effects we found for extensive black tribal tattoos on the forearm can be generalized to other types of tattoos like a friendly “aloha” lettering. A third point that should be considered is social change. While our data showed that participants perceived police officers with body modifications more negatively, they, at the same time, explicitly stated rather positive attitudes towards piercings on police officers. If officers would be allowed to have body modifications they could contribute themselves to social change. If citizens would have positive interactions with tattooed and/or pierced officers, maybe also the perception of officers with body modifications would improve over time. Fourth and most importantly, for an informed decision on whether police officers should be allowed to wear tattoos and piercings or not, further aspects must be taken into account that go beyond the scope of what social psychological research can contribute. Two crucial aspects are, for instance, the right of each individual to express their individuality by tattoos and piercings and safety issues regarding piercings. In a physical confrontation, a piercing can potentially be used by aggressors to hurt the officer, for example, by pulling it, one reason why piercings are forbidden in the police service in Germany (Henrichs 2002).

That being said, our research provides important empirical information regarding one argument often brought forward in discussions concerning police officers’ right to wear tattoos, namely the question how citizens perceive police officers with tattoos and piercings. The present research indicates that tattoos and piercings can in fact negatively affect how citizens perceive officers. Thus, this should be part of the respective considerations. If body modifications were allowed, the present research suggests that officers should be aware of the potentially negative perceptions triggered by tattoos and piercings, so that they can make a more informed decision to get them or not. Moreover, if tattooed and pierced officers have this potentially negative effect in mind, they can actively take countermeasures in their interaction with citizens to prevent negative consequences—keeping in mind that citizens might form a first impression before the interaction even starts (Olivola and Todorov 2010; Zebrowitz 1996).

Conclusion

The present research contributes to the public discussion on how police officers with tattoos and piercings are perceived by citizens. Using an experimental design, our studies indicate that police officers with tattoos and piercings are perceived as somewhat less trustworthy, less competent, and more threatening than the ones without tattoos and piercings, despite relatively positive explicit attitudes towards piercings for police officers. In cases of dispute, policy makers and judges decide whether a police officer is allowed to have a body modification on a visible part of the body. They need to weigh the right of each individual to express their personality against public expectations of police officers. The present research can enrich this decision making process by providing empirical data on how specific tattoos and piercings affect citizens’ perception of police officers, thus contributing to science-based policy making.

Data Availability

The data of the two studies are available at https://osf.io/c3emk/?view_only=57dd267ab06d4f838a56fa28726548e4.

References

Abele AE, Hauke N (2019) Comparing the facets of the Big Two in global evaluation of self versus other people. Eur J Soc Psychol 50(5), 969–982. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2639

Abele AE, Hauke N (2020) Comparing the facets of the big two in global evaluation of self versus other people. Eur J Soc Psychol 50:969–982. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2639

Abele AE, Wojciszke B (2014) Communal and agentic content in social cognition: a dual perspective model. Adv Exp Soc Psychol 50:195–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-800284-1.00004-7

Abele AE, Hauke N, Peters K, Louvet E, Szymkow A, Duan YP (2016) Facets of the fundamental content dimensions: agency with competence and assertiveness – communion with warmth and morality. Front Psychol 7:1810. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01810

Adams J (2012) Cleaning up the dirty work: Professionalization and the management of stigma in the cosmetic surgery and tattoo industries. Deviant Behav 33(3):149–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2010.548297

Baumann C, Timming AR, Gollan PJ (2016) Taboo tattoos? A study of the gendered effects of body art on consumers’ attitudes toward visibly tattooed front line staff. J Retail Consum Serv 29:31–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2015.11.005

Bayerische Staatskanzlei (2016) Keine Genehmigung für Tätowierung eines Polizeibeamten im sichtbaren Bereich - "Aloha". [No authorization of tattoo on visible body parts for police officer – “aloha”] Retrieved July 20, 2020, from https://www.gesetze-bayern.de/(X(1)S(uy0nk0iwqferdobuf02pfwo0))/Content/Document/Y-300-Z-BECKRS-B-2016-N-52533?hl=true&AspxAutoDetectCookieSupport=1&fontsize=large

Birk FP, Habermehl TP, Klemens RP, Lamacz FP (2001) Wirkung des äußeren Erscheinungsbildes von Polizeibeamtinnen und Polizeibeamten auf die Akzeptanz des Einschreitens. [Impact of the outer appearance of female and male police officers on the acceptance of intervention] Polizei Rheinland-Pfalz

BfR-Verbrauchermonitor (2018). Tattoos im Trend - Die Hälfte der Deutschen hält Tätowiermittel für sicher. [Tattoos as trend – Half of the Germans consider tattoo colorants as safe] Retrieved March 31, 2020, from https://www.bfr.bund.de/de/presseinformation/2018/42/tattoos_im_trend___die_haelfte_der_deutschen_haelt_taetowiermittel_fuer_sicher-207846.html

Brambilla M, Leach CW (2014) On the importance of being moral: the distinctive role of morality in social judgment. Soc Cogn 32(4):397–408. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2014.32.4.397

Brambilla M, Sacchi S, Rusconi P, Cherubini P, Yzerbyt VY (2012) You want to give a good impression? Be honest! Moral traits dominate group impression formation. Br J Soc Psychol 51(1):149–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.2010.02011.x

Burgess M, Clark L (2010) Do the “savage origins” of tattoos cast a prejudicial shadow on contemporary tattooed individuals? J Appl Soc Psychol 40(3):746–764. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00596.x

Carrier A, Louvet E, Chauvin B, Rohmer O (2014) The primacy of agency over competence in status perception. Social Psychology 45:347–356. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000176

Cuddy AJC, Fiske ST, Glick P (2008) Warmth and competence as universal dimensions of social perception: the stereotype content model and the BIAS Map. Adv Exp Soc Psychol 40:61–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(07)00002-0

Dale LR, Bevill S, Roach T, Glasgow S, Bracy C (2009) Body adornment: A comparison of the attitudes of businesspeople and students in three states. AELJ 13(1). Retrieved March 31, 2020, from https://www.questia.com/library/p150920/academy-of-educational-leadership-journal/i2591517/vol-13-no-1-january

Deal JJ, Altman DG, Rogelberg SG (2010) Millennials at work: what we know and what we need to do (if anything). J Bus Psychol 25(2):191–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9177-2

Dean DH (2010) Consumer perceptions of visible tattoos on service personnel. Manag Serv Qual 20(3):294–308. https://doi.org/10.1108/09604521011041998

Degelman D, Price ND (2002) Tattoos and ratings of personal characteristics. Psychol Rep 90(2):507–514. https://doi.org/10.2466/PR0.90.2.507-514

DeMello M (2000) Bodies of inscription: A cultural history of the modern tattoo community. Duke University Press

Dickson L, Dukes R, Smith H, Strapko N (2014) Stigma of ink: Tattoo attitudes among college students. Soc Sci J 51(2):268–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2014.02.005

Donnelly K, Twenge JM (2017) Masculine and feminine traits on the Bem Sex-Role Inventory, 1993–2012: a cross-temporal meta-analysis. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research 76(9–10):556–565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0625-y

Durkin K, Houghton S (2000) Children’s and adolescents’ stereotypes of tattooed people as delinquent. Leg Criminol Psychol 5(2):153–164. https://doi.org/10.1348/135532500168065

European Social Survey Round 9 Data (2018). Data file edition 1.2. Norwegian Centre for Research Data, Data Archive and distributor of ESS data for ESS ERIC. https://doi.org/10.21338/NSD-ESS9-2018

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A, Buchner A (2007) G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 39(2):175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Forbes GB (2001) College students with tattoos and piercings: motives, family experiences, personality factors, and perception by others. Psychol Rep 89(3):774–786. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.2001.89.3.774

Funk F, Todorov A (2013) Criminal stereotypes in the courtroom: facial tattoos affect guilt and punishment differently. Psychol Public Policy Law 19(4):466–478. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034736

Hauke N, Abele AE (2019) Two faces of the self: actor-self perspective and observer-self perspective are differentially related to agency versus communion. Self Identity 19:346–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2019.1584582

Hauke N, Abele AE (2020) The impact of negative gossip on target and receiver. A “Big Two” analysis. BasicAppl Soc Psych 42(2):115–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2019.1702881

Hauke N, Abele AE (2020) Communion and self-esteem: No relationship? A closer look at the association of agency and communion with different components of self-esteem. Personality Individ Differ 160 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.109957

Hawkes D, Senn CY, Thorn C (2004) Factors that influence attitudes toward women with tattoos. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research 50(9–10):593–604. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:SERS.0000027564.83353.06

Hemmerich W (2016) StatistikGuru: Rechner zur Adjustierung des α-Niveaus. [StatisticGuru: Calculator for the Adjustment of the α-Level] https://statistikguru.de/rechner/adjustierung-des-alphaniveaus.html

Henrichs A (2002) Zum äußeren Erscheinungsbild einer professionellen deutschen Polizei. [About the physical appearance of a professional German police] Retrieved March 31, 2020, from https://www.gdp.de/gdp/gdp.nsf/id/dp0202/$file/DeuPol0202X.pdf

Hogan R (1982) A socioanalytic theory of personality. In M. Page (ed) Nebraska symposium on motivation (pp. 336–355). University of Nebraska Press.

Holm S (1979) A Simple Sequentially Rejective Multiple Test Procedure. Scand J Stat 6(2):65–70. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4615733

Ipsos (2019) More Americans have tattoos today than seven years ago. Retrieved March 31, 2020, from https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/news-polls/more-americans-have-tattoos-today

Kiesler C, Goldberg G (1968) Multidimensional approach to the experimental study of interpersonal attraction: Effect of a blunder on the attractiveness of a competent other. Psychol Rep 22(3), 693–705. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1968.22.3.693

Leach CW, Ellemers N, Barreto M (2007) Group virtue: the importance of morality (vs. competence and sociability) in the positive evaluation of in-groups. J Pers Soc Psychol 93:234–249. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.2.234

Lin Y (2002) Age, sex, education, religion, and perception of tattoos. Psychol Rep 90(2):654–658. https://doi.org/10.2466/PR0.90.2.654-658

Louvet E, Cambon L, Milhabet I, Rohmer O (2019) The relationship between social status and the components of agency. J Soc Psychol 159(1):30–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2018.1441795

McMullen S, Gibbs J (2019) Tattoos in policing: A survey of state police policies. Policing: An International Journal 42:408–420. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-05-2018-0067

Martino S (2008) Perceptions of a photograph of a woman with visible piercings. Psychol Rep 103(1):134–138. https://doi.org/10.2466/PR0.103.5.134-138

McElroy JC, Summers JK, Moore K (2014) The effect of facial piercing on perceptions of job applicants. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 125(1):26–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2014.05.003

Methner N, Bruckmüller S, Steffens MC (2020) Can accepting criticism be an effective impression management strategy for public figures? A comparison with denials and a counterattack. Basic Appl Soc Psychol 42(4):254–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2020.1754824

Niedersächsische Polizei-Fachhochschule (2001) Leitthemenstudie ‘Erscheinungsbild der Polizei’ [Key topic study ‘Outer appearance of the police’] Polizei Niedersachsen

Olivola CY, Todorov A (2010) Fooled by first impressions? Reexamining the diagnostic value of appearance-based inferences. J Exp Soc Psychol 46(2):315–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.12.002

Paulhus DL, Trapnell PD (2008) Self-presentation of personality: An agency-communion framework. In OP John, RW Robins, LA Pervin (eds) Handbook of personality psychology: Theory and research, 3rd edn. (pp. 492–517). Guilford Press

Resenhoeft A, Villa J, Wiseman D (2008) Tattoos can harm perceptions: a study and suggestions. J Am Coll Health 56(5):593–596. https://doi.org/10.3200/JACH.56.5.593-596

Rohr E (2009) Vom sakralen Ritual zum jugendkulturellen Design. Zur sozialen und psychischen Bedeutung von Piercings und Tattoos. [From sacral ritual to a youth culture design. On the social and psychological meaning of piercings and tattoos] Retrieved March 31, 2020, from https://www.transcript-verlag.de/chunk_detail_seite.php?doi=10.14361%2F9783839412275-011

Schäfer R, Thielgen MM, Eberz S, Telser C, Wels A, Gimmler L (2019) Das Erscheinungsbild von Polizeibediensteten – Neue Erkenntnisse zur Wirkung auf die Bevölkerung. [The appearance of police officers – New insights on the effect on citizens] Die Polizei 110:289–296

Schildkrout E (2004) Inscribing the body. Annu Rev Anthropol 33:319–344. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.33.070203.143947

Seiter J, Sandry A (2003) Pierced for success?: the effects of ear and nose piercing on perceptions of job candidates’ credibility, attractiveness, and hirability. Commun Res Rep 20(4):287–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824090309388828

Simon B (2007) Respect, equality, and power: a social psychological perspective. Gr Organ 38(3):309–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11612-007-0027-2

Spiegel (2018) Gericht erlaubt Löwen-Tattoo bei Polizist. [Court authorizes lion tattoos on police officers] Retrieved March 31, 2020, from https://www.spiegel.de/karriere/duesseldorf-polizei-bewerber-mit-taetowierung-muss-eingestellt-werden-a-1206747.html

Spiegel (2020). Polizist darf sich "Aloha"-Tattoo nicht stechen lassen. [Police officer is not allowed to get “aloha” tattoo] Retrieved July 20, 2020, from https://www.spiegel.de/karriere/bundesverwaltungsgericht-polizist-darf-sich-kein-aloha-tattoo-stechen-lassen-a-1439958b-d54b-4d72-b5f6-ed3a1ec24019

Statisticbrain (2017) Body piercing statistics. Retrieved March 31, 2020, from https://www.statisticbrain.com/body-piercing-statistics/

Stirn A, Hinz A, Brähler E (2006) Prevalence of tattooing and body piercing in Germany and perception of health, mental disorders, and sensation seeking among tattooed and body pierced individuals. J Psychosom Res 60(5):531–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.09.002

Swami V, Furnham A (2007) Unattractive, promiscuous and heavy drinkers: perceptions of women with tattoos. Body Image 4(4):343–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2007.06.005

Swami V, Stieger S, Pietschnig J, Voracek M, Furnham A, Tovée MJ (2012) The influence of facial piercings and observer personality on perceptions of physical attractiveness and intelligence. Eur Psychol 17(3):213–221. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000080

The Guardian (2016) How would you react if you met a tattooed police officer? Retrieved March 31, 2020, from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/aug/31/tattooed-police-officer-police-federation

Thielgen MM, Schade S, Rohr J (2020) How criminal offenders perceive police officers’ appearance: effects of uniforms and tattoos on inmates’ attitudes. J Forensic Psychol Res Pract. https://doi.org/10.1080/24732850.2020.1714408

Timming AR, Nickson D, Re D, Perrett D (2017) What do you think of my ink? Assessing the effects of body art on employment chances. Hum Resour Manage 56:133–149. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21770

Tyler TR, Degoey P (1996) Trust in organizational authorities: The influence of motive attributions on willingness to accept decisions. In RM Kramer, TR Tyler (eds) Trust in organizations: Frontiers of theory and research. (pp. 331–356). Sage Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452243610.n16

Universität Leipzig (2017) Schönheitstrend: Tattoos und Körperhaarentfernungen werden bei den Deutschen immer beliebter. [Beauty trend: Tattoos and body hair removal get more popular with Germans] Retrieved March 31, 2020, from https://www.uni-leipzig.de/newsdetail/artikel/schoenheitstrend-tattoos-und-koerperhaarentfernungen-werden-bei-den-deutschen-immer-beliebter-2017-09/

Vandekerckhove L (2005) Tätowierung: Über die Soziogenese von Schönheitsnormen. [Tattoos: On the sociogenesis of beauty norms] Anabas.

Wohlrab S, Fink B, Kappeler PM, Brewer G (2009) Perception of human body modification. Personality Individ Differ 46(2):202–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.09.031

Wohlrab S, Stahl J, Rammsayer T, Kappeler PM (2007) Differences in personality characteristics between body-modified and non-modified individuals: associations with individual personality traits and their possible evolutionary implications. Eur J Pers 21(7):931–951. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.642

Wojciszke B, Abele AE, Baryla W (2009) Two dimensions of interpersonal attitudes: liking depends on communion, respect depends on agency. Eur J Soc Psychol 39(6):973–990. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.595

Ybarra O, Chan E, Park H, Burnstein E, Monin B, Stanik C (2008) Life’s recurring challenges and the fundamental dimensions: an integration and its implications for cultural differences and similarities. Eur J Soc Psychol 38:1083–1092. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.559

Zebrowitz LA (1996) Physical appearance as a basis of stereotyping. In CN Macrae, C Stangor, M Hewstone (eds) Stereotypes and stereotyping (pp. 79–120). Guilford Press.

Zeiler N, Kasten E (2016) Decisive is what the tattoo shows: Differences in criminal behavior between tattooed and non-tattooed people. Soc Sci 5:16–20. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ss.20160502.12

Zestcott CA, Bean MG, Stone J (2017) Evidence of negative implicit attitudes toward individuals with a tattoo near the face. Group Process Intergroup Relat 20(2):186–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430215603459

Zestcott CA, Tompkins TL, Kozak Williams M, Livesay K, Chan KL (2018) What do you think about ink? An examination of implicit and explicit attitudes toward tattooed individuals. J Soc Psychol 158(1):7–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2017.1297286

Acknowledgements

We thank Nina Wenzel and Polina Martynov for their help in data collection and the Police Academy of the State of Rhineland-Palatinate for providing the raw images of police officers used in the studies. Christine Telser at the Police Academy provided helpful comments on the materials.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Statement and Consents to Participate and for Publication

All studies reported in this paper have been performed according to APA ethical standards for the treatment of human subjects. Data collection was anonymous and participation strictly voluntary. All participants were at least 18 years old, were informed that they had the right to withdraw at any time without penalty, gave written consent for their participation and for the inclusion of their data for publication, and were debriefed after the studies. The study involved no deception and no potential harm for participants. Accordingly, no approval of an ethics committee was deemed necessary.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hauke-Forman, N., Methner, N. & Bruckmüller, S. Assertive, but Less Competent and Trustworthy? Perception of Police Officers with Tattoos and Piercings. J Police Crim Psych 36, 523–536 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-021-09447-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-021-09447-w