Abstract

The emergence of risk-based capital regulation that is allowing banks to use their internal risk models for regulatory purposes was among the main regulatory developments prior to the financial crisis. During the crisis, it became evident these models underestimated the level of risk. The post-crisis regulatory approach brought a reversal of policy by significantly reducing the scope of risk-based capital regulation and making regulations less risk-sensitive. At first glance, this appears to be a step back toward an antiquated, less sophisticated regulatory regime. This article analyses these two regulatory policy transformations: from less risk-sensitive to risk-based before the crisis and from risk-based to less risk-sensitive subsequently. Its main conclusion is that a mixed regulatory system is superior to either purely non-risk-sensitive or purely risk-based regulation, because a mixed system can help mitigate the negative incentives of both non-risk-sensitive and risk-based regulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The term ‘risk-based regulation’ is used in several ways. Regulatory scholars generally use it as a framework for prioritizing scarce regulatory resources. In this sense, risk-based regulation is a regulatory strategy that helps determine the focus of regulatory intervention. The concept is not specific to banking and has been used by regulators in several other sectors [1,2,3]. However, another meaning has emerged for the term ‘risk-based regulation’ in banking regulation, namely allowing banks to use their internal risk-management models to determine regulatory capital requirements, also known as risk-based regulation [4, 5]. Throughout this article, we have applied the latter definition to the concept of risk-based regulation, while risk-based regulation and risk-based capital regulation are used synonymously.

The global financial crisis (GFC) resulted in a shift in the regulatory approach to banking regulation. The most important aspect of this shift is without doubt the emergence of macroprudential regulation. In addition, another very important change took place in how the best practices of banks with regard to their internal risk measurement and management models are accepted for calculating regulatory capital requirements. This paper focuses on the second issue: the emergence of regulation based on banks’ internal risk models and risk management practices prior to the crisis, and the loss of confidence in the banks’ internal models during the GFC, which resulted in several limitations in using these models for regulatory purposes in the wake of the crisis, that is the ascent and descent of risk-based capital regulation of banks.

The main characteristic of pre-crisis banking regulation was its increasing reliance on banks’ internal risk-management models. This was based on the acknowledgement that banks are much more familiar with and are able to more accurately measure the risks they are taking on than regulators. As the first step of this process, the amendment to the Basel I regulatory framework in 1996 introduced capital requirements to market risk and allowed banks to use their internal value at risk (VaR) models for regulatory purposes based on several qualitative and quantitative requirements [6]. The culmination of this process was the adoption of the Basel II Capital Accord in 2006 and its implementation just before the crisis [7]. Basel II allowed banks with high-level risk awareness and risk-management practices to use their internal models for regulatory capital requirement calculations. As regarded credit risk, the regulation did not allow for full risk modeling, but several parameters of the regulatory model were permitted to be estimated by the banks themselves. In relation to operational risk, full modeling was even permitted. As a result, all three major banking risk types covered by the obligatory regulatory capital requirement (i.e., credit risk, market risk and operational risk) became at some level subject to model-based capital requirements, dependent on supervisory approval.

At first glance, from the point of view of regulatory efficiency the risk-based capital regulation appeared to be a huge step forward as it was in line with the risk absorption function of capital: higher risk demands higher capital requirements to better protect the money of depositors from banking risks [8]. In line with the supposed superiority of risk-based regulation, the declared aim of regulators was to support the development of risk management by creating a trade-off between the higher risk-management cost of advanced methods and the higher capital requirements of simpler standardized methods. However, the GFC brought into question whether the greater reliance on the risk management models of banks was really as effective as it had appeared initially. Within the Basel III framework, regulators have withdrawn the full modeling option for operational risk and have also fundamentally changed the principles of market risk modeling and incorporated several limitations to allow the use of the results provided by credit risk models. In this paper, we analyze regulatory developments only in relation to credit risk, analyzing both reversals—i.e., from simple ratio-based to risk-based regulation and then back from risk-based to less risk-sensitive regulation—not only from the point of view of efficiency but also with respect to related incentive structures, that is, whether it represents the private or public interest view of banking regulation [9, 10]. The analysis focuses on global and EU-level developments without taking account of national deviations.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 summarizes the motivations for and characteristics of the emergence of risk-based capital requirements regulation before the GFC. Section 3 highlights the limitations of the risk-based approach. Section 4 overviews the rationale for and the tools of limiting the scope of risk-based capital requirements regulation and for integrating risk-based and non-risk-sensitive regulatory tools. The final section provides conclusions.

The emergence of banks’ risk-based capital requirements regulation

According to Basel I Accord, banks had to apply four risk buckets (0%, 20%, 50% and 100%) for weighting their assets and determine their regulatory capital requirement at 8% of their risk-weighted assets (RWA). That is, comparing with the simple leverage ratio regulation, which was existed in several national regulations in the 1980s, even the Basel I Accord contained risk-sensitive items. The main critique of the Basel I Accord was easy arbitrage: increased risk per unit within the same broad asset category resulted in an unchanged capital requirement but higher risk and return, which incentivized higher risk taking. Even though the 8% capital requirement would in principle have been a risk proxy, there was no empirical justification for it. It was merely the result of a political compromise: at that time, it was relatively easy to meet for the better capitalized European and US banks, while the necessary capital increase was also acceptable to the less capitalized Japanese banks [11, 12]. As a result, the regulatory capital requirement for credit risk, referred to at the time as risk-based, did not reflect the concrete level of banking risk [13]. By 1999, around 100 countries had implemented the Basel I Accord [14]. However, studies assessing the effects of Basel I did not find evidence that banks actually increased their risk appetite for regulatory arbitrage purposes [14, 15].

Meanwhile, during the second half of 1990s, banks started to develop their own credit risk models to enable them to more precisely measure their risk. Several models became widely used and generally accepted, such as the CreditMetrics created by J.P. Morgan or the CreditRisk + established by Credit Suisse [16]. With the help of these models, banks became able to determine their own ‘economic’ capital requirement, i.e., the internally calculated level of capital they needed to absorb credit risk. The most important field of use for these models was the risk-based internal capital allocation system that allowed banks to calculate their most important profitability indicator, their risk-adjusted return on capital, known as the RAROC. The closer the regulatory capital requirement is to the economic capital held by the banks, the higher their return on equity. The higher the regulatory capital requirement compared to the level of economic capital, the lower the banks’ profit, while the excess capital represents a ‘superfluous burden’ on the banks. Accordingly, banks have a strong business interest and incentive to push the regulators toward a regulatory system based more on banks’ internal risk management practices and to let them use their own internal models to determine their credit risk capital requirements.

The collapse of several banks and other financial institutions during the second half of the 1990s also pushed regulators to reform capital requirements. As Jones and Mingo pointed out ‘…despite the difficulties with an internal model approach to bank capital, no alternative long-term solutions have yet emerged.’ [13 p.60]. As part of preparations for the development of the Basel II framework, the BCBS assessed the credit risk modeling practices of banks to support a decision on their potential application for regulatory purposes [17]. It stressed several benefits of credit risk models, especially in relation to their risk sensitivity, flexibility and the incentives they produced to advance risk management. However, despite these benefits, it concluded that several important hurdles had to be overcome before models could be used for regulatory purposes. Some months later, in June, BCBS published the first consultation paper on Basel II, which was a significant step toward accepting risk-based capital requirements for credit risk [18]. In the short run, it rejected the use of full credit risk modeling for regulatory purposes. In the longer term, however, it identified an opportunity to move toward full model-based capital requirements. At the same time, the document expressed the BCBS’s commitment to increased risk-sensitive capital regulation in the form of using banks’ internal rating systems to set regulatory capital requirements. That is, even if it did not allow full modeling, it would allow banks to model their most important risk parameters. These characteristics of Basel II did not change during the consultation period, so its final version, as well as its European version, the capital requirement directives (CRD),Footnote 1 allowed banks to use their internal risk management models to calculate credit risk parameters subject to supervisory approval.

The regulatory credit risk model was developed by the Basel Committee based on the banks’ best practices. For banks with developed, but not the most advanced, risk-management practices, only the most important risk parameter, the probability of default of the obligors (PD), was estimated by the banks under the Foundation Internal Ratings-Based (F-IRB) approach, while other parameters (the LGD, the loss given default; the EAD, the exposure at default and the M, the maturity of exposure) were determined by regulation. Under the Advanced IRB method, all these parameters are estimated by the banks. The regulatory model is a single-factor model, where the risk factor is the correlation among the assets’ default within the same asset class. That is, the correlation coefficient stands for the systematic (i.e., non-diversifiable) risk of the portfolio. The higher the correlation, the higher the capital requirement. Accordingly, both the built-in correlation coefficient and the parameters of the model play important roles in determining capital requirements. The lobbying ability of banks was clear in the process of formulating these parameters during the consultation period of Basel II. In the early consultation documents, for example, the Foundation IRB’s regulatory LGD for unsecured corporate exposures was 50% and the average maturity was three years [19]. These values significantly decreased during the consultation period. In the final version, the regulatory LGD was 45% while the average maturity was 2.5 years, so the same model resulted in significantly lower regulatory capital requirements [7]. As regards the correlation coefficients applied, their estimates were based on the G10′s supervisory data collection and analysis, and on some fairly rudimentary calculations, making them highly intuitive [20]. During the consultation period, the correlation coefficients were also decreased for two asset classes: qualifying revolving retail exposures and other retail exposures. There is no example of change in the opposite direction, i.e., for a parameter to increase during the consultation period.

The procyclical nature of the Basel II regulation was also highly debated from the very beginning of the consultation period. It is important from the point of view of the calibration of risk parameters, as well as the scaling up of capital requirements due to cyclical uncertainties. Some studies argued that it was unlikely that the Basel II rules would increase the procyclicality of bank behavior [21,22,23,24]. However, there were a significantly larger bulk of studies that stressed the highly procyclical nature of the regulation [25,26,27,28,29,30]. In the end, two relatively inconsequential items were incorporated into the regulation as countercyclical tools: the requirement to use through-the-cycle PD and downturn LGD. However, these items were not dominant elements of the regulation, they were more ‘good intentions’ than strong analytical features and were without strict calibration rules or even principles. Moreover, through-the-cycle PD, as an average value for the cycle, is by definition too low in the event of financial turbulence. The above uncertainties of the model and its unknown side effects were not addressed through the scaling of the results of the models. The regulatory model applied a scaling factor, but the 1.06 multiplier was merely symbolic. That is, the private interests of the banks to a great extent overcame the public interest of stronger capitalization in the preparatory phase of the regulation.

Limitations of the risk-based approach to banks’ capital regulation

Assessing the problems and limitations related to the risk-based capital requirement for credit risk regulatory capital, we can highlight the following three factors: (1) model inadequacy risk; (2) model accuracy and implementation risk; and (3) incentive problems. In the literature, the expression ‘model risk’ generally relates to both (1) and (2). However, as we will see in the following, some authors emphasize the inadequacy of models, while others focus on accuracy and implementation issues. Throughout this paper, we have distinguished between the two concepts. In our understanding, the model inadequacy risk is the risk that the models do not adequately describe risk, and as a result the capital requirements based on their results are not appropriate for fully absorbing potential losses. We argue that the model inadequacy risk is a type of risk that cannot be eliminated by improving the models, since it is impossible to have a fully appropriate model. Unlike model inadequacy risk, accuracy and implementation risks entail the risk that the regulatory models are not sufficiently accurate, so their explanatory and forecasting effectiveness is lacking on one hand, while banks can implement the regulatory model in different ways on the other, thereby undermining the level playing field and diluting capital calculations due to the ‘innovative’ interpretation of regulatory requirements. This type of risk can be significantly mitigated by improving the accuracy requirements of the model and standardizing implementation practices.

With regard to model inadequacy, the high risk of using models for capital calculation has been well known since the early 2000s [25]. As Danielsson wrote, ‘Such models are useful for measuring the risk of frequent small events, but not for systematically important events.’ [31 p.321]. He argues that sophistication does not imply quality, as the rules of physics are not akin to those of finance, because finance is more complex. The reason for this mismatch is the endogenous nature of risk, especially in times of crisis, when shocks come not from outside the financial system but are generated and intensified within it [27]. Besides the endogenous nature of risk in turbulent times, Danielsson also stresses the poor quality of assumptions and data used for modeling [31]. Since the models significantly simplify the number of relevant factors, newly emerged or difficult-to-model factors can fall out of the scope of the models used. He also stresses that the quality of data used for modeling can significantly change over time and that this can undermine the quality of any models based on historical data. He demonstrates these deficiencies with regard to both market risk and sub-prime credit risk models. In his view, these models are suitable for the day-to-day risk management of banks, but their aim is not to minimize but maximize the risk to capital, i.e., to develop methods which allow banks to increase their RWA-to-equity ratio, so the development of modeling best practice is by its very nature a race to the bottom.

Greenspan expresses very similar views [32]. Besides stressing the inherent deficiencies of risk models, he also calls attention to the fact that the main objective of risk managers is to maximize the risk-adjusted return on equity, which results in a strong incentive to indulge in economic euphoria. However, the models they use cannot anticipate the turning points of economic cycles, as these lie in the irrational human responses to the market that Greenspan refers to as the ‘missing explanatory variable.’ That is, he argues that insufficient input data undermines the reliability of the models. In his view, the artificial modification of the results of the models is necessary to somehow offset the missing explanatory variable. As he stresses, modification, by definition, is the implicit recognition of the deficiencies of the models.

To understand the core of the above, we should recall the classical view of Knight on risk and uncertainty [33]. Knight distinguishes between two types of unknown. Unknown outcomes that are measurable with the tools of probability theory and statistics are referred to as risk, while immeasurable outcomes are defined as uncertainty. It appears evident that even the best modeling practices can refer only to measurable factors, that is to risk in Knightian terms. However, in the theory of bank capital, as well as according to Basel thinking on risk and regulation, the concept of risk and the capacity of banking capital to absorb losses refers to all the potential losses of banks. Accordingly, risk that should be absorbed by bank capital, which is known as banking risk, can derive from both Knightian risk and uncertainty. Consequently, the level of capital high enough to absorb all losses should therefore refer also to both. Capital regulation that focuses only on measurable losses is misleading by definition, since it takes into account only Knightian risk and ignores uncertainty. Even if this dichotomy is not stressed explicitly by the Basel standards, the evolution of the standards demonstrates that this issue has been recognized through its incorporation into the Basel III regulatory framework. An important difference between the pre-, and post-GFC regulation is that the latter increasingly widely uses stress tests and several different capital buffer requirements to increase the loss-absorbing capacity of banks on the top of model-based capital requirements. However, even the stress tests and various capital buffers intended to correct the deficiencies of model-based capital requirements are also predominantly based on modeling.

Knightian uncertainty in relation to the potential losses of banks can be expressed in technical terms through dramatically increased PDs, LGDs and correlations beyond those values measured by the risk management models. The countercyclical items of Basel II, namely the through-the-cycle PDs and downturn LGDs, do not intend to refer to these extreme increases, their aim is solely to smooth capital requirements through the cycle. However, the parameters causing Knightian uncertainty can change all at once, especially in crises. As regards the correlation coefficient, it can increase significantly in turbulent times; and may approach one in extreme circumstances. At present (this remained unchanged in Basel III), the highest correlation coefficient is 24% for corporate and sovereign, and 16% for retail exposure. However, because a higher PD requires a lower correlation coefficient in the IRB model, the capital requirement is lowered by the counterbalancing effect of a decrease in correlation coefficient in times of elevated PD. The only change introduced after the GFC in this respect is that the correlation coefficient was multiplied by 1.25 for large financial institutions and unregulated financial institutions, therefore taking its maximum up to 30%.

Similarly to market risk models, the IRB models are consequently only able to measure—to a greater or lesser extent—business as usual capital requirements, not those of turbulent times with dramatically increased PDs, LGDs and correlations.

Industry representatives and even some regulatory and supervisory bodies define model risk more narrowly, i.e., in the sense of model accuracy and implementation risk. They assume that models are essentially appropriate regulatory tools but need to be refined and implemented in a more standardized manner. According to this approach, the accuracy and implementation risk of models, i.e., the risk of inappropriate modeling practice and the differences in national regulators and supervisors in model validation, can call into question the concept of a level playing field, which lies at the core of the shortcomings associated with risk-based regulation. In 2015, the European Banking Authority (EBA) published a discussion paper on the future of the IRB approach [34]. The paper does not question the general rationale of the IRB approach. Instead, it focuses solely on accuracy and implementation risk. It stresses that ‘The EBA believes that from an overall perspective the IRB framework has proven its validity as a risk-sensitive way of measuring capital requirements, which also encourages institutions to implement sound and sophisticated internal risk management practices. However, despite the positive aspects of the IRB models, the very high degree of flexibility in the IRB framework has compromised comparability in capital requirements. Some observers have therefore questioned the reliability of IRB models, which has triggered a lack of trust in the use of IRB models.’ [34 p.5]. This means that, according to the EBA, model risk is equivalent to model accuracy and implementation risk and can be mitigated by refining the modeling requirements and by standardizing the quality of data, measurement practices and the supervisory validation process. In line with this approach, the discussion paper raised 25 highly technical questions.

The EBA received 28 responses, 22 of which have been made public. The document published as a summary of the discussion also shares this view [35]. Besides the technical answers on refining the banks’ IRB parameter modeling techniques, the respondents provided strong support for the use of the IRB approach as an effective method of efficient internal capital allocation. The respondents also stressed that ‘…other less risk-sensitive frameworks are also prone to regulatory arbitrage, just as they may encourage banks to invest in riskier assets.’ [35 p.6]. That is, they argued for risk-based regulation as superior to less risk-sensitive regulation, underlining that while both types of regulation have common deficiencies, risk-based regulation has definite advantages and is more efficient. However, they focus on model accuracy and implementation risk only, and not on model adequacy risk. The same view is expressed by Resti [36].

At the same time, the BCBS and the EBA surveyed the consistency of RWAs in line with their efforts to increase the consistency of banking practice [37, 38]. These documents also refer to the high level of model accuracy and implementation risk. The BCBS collected data in relation to retail and SME exposures from 35 internationally active large IRB banks [37]. Their findings show extremely high variation in average risk weights, for example, the range is between 5.2% and 81.1% for residential mortgages, with a median of 16.9%, while the risk weighting of SMEs is in a range of 46.2% to 91.2% with a median of 59.8%. The EBA survey covered 102 IRB banks from 22 EU Member States [38]. It also found large differences in PDs of the same asset classes. However, as the document stresses, the reason for differences may lie not only in the difference in PD modeling, but as a result of the different risk characteristics of the participating banks, too. That is why the hypothetical portfolio analysis also conducted by EBA is of outstanding importance as it analyzed low default portfolios, i.e., the sovereigns, institutions and large corporates [39]. Within this exercise, more than 100 participating banks calculated the global charge (both for expected and unexpected loss, i.e., provisioning and capital charges together) for the same hypothetical portfolio. The survey found extremely high variability of global charge, with a range of between 8 and 147%. Of the differences, 61% could be explained by different risk drivers, while 39% may be the result of different modeling practices.

Incentive problems are not independent of both types of model risk. Both Danielsson and Greenspan have already connected the model adequacy risk to incentive problems [31, 32]. They emphasized that it is in the private interest of the banks to maximize their risk-adjusted return on equity. This objective is a long way from the public interest in terms of financial stability and consumer protection. Linking model adequacy risk and incentive problems with the way the Basel Committee bolstered regulation within the Basel III regulatory framework, coined the phrase ‘the illusion of measurability of risks.’ [40 p.6]. In his view, the Basel Committee is in error when it looks upon the deficiencies of risk-based regulation as a series of technical difficulties that can be improved. He argues that the sophisticated risk-management techniques developed by banking risk professionals serve the private interests of banks, since they help them to reduce the level of capital to the minimum acceptable level. Only the banks have the necessary resources to hire the best professionals and pay them considerably above the wages offered in other segments of the market to innovate risk models in the interests of saving capital. The regulators are always one step behind and are content to validate these models. However, this private interest is different from the public interest of maintaining prudent banking and protecting consumers. Admati refers to the Basel III regulatory framework as ‘the missed opportunity’ as it failed to significantly increase the level of banking capital, which turned out to be critically low during the crisis [41]. Similarly to Hellwig, and as explained in detail in their co-authored book, Admati argues that banks, like other companies, should be required to use much more equity in the form of retained profits and the issue of new shares to fund their lending [40,41,42]. The small proportion of equity lets the banks establish high levels of leverage, which in turn multiplies the gains and losses of the banks’ equity holders. This allows them to realize extraordinarily high profits in good times, while they may easily lose their investment when things turn bad. However, explicit and implicit guarantees in the form of deposit insurance and government bail-outs limits their downside risk almost without limiting the upside gains, leading to an increase in risk appetite and high leverage, and a correspondingly strong incentive to use risk-based modeling.

Model accuracy and implementation risk are also closely related to incentive problems. Several studies have pointed out that the risk weights determined by the banks themselves are too low because they are biased toward the banks’ private interests [43,44,45,46]. Accordingly, the accuracy of the models and their proper implementation are highly questionable. Some of these papers directly link the risk-modeling practice of banks and the bad incentives of risk-based regulation and measure the PD biases of banks. Plosser and Santos (2014) used the data on US syndicated loans to compare the PDs of different banks financing the same loan at the same point in time and found significant differences, with the more downward-biased PDs (i.e., underestimation of risk) characterized those banks with a weaker capital position [46]. Mariathasan and Merrouche analyzed the dataset of 115 IRB banks from 21 OECD countries, focusing on risk-weighted assets to total asset ratio before and after receipt of the IRB license [44]. Their results show that, following regulatory approval of IRB, banks report lower risks than previously, that is, they use strategic modeling for RW manipulation. For those banks with a weaker capital position, the decline of RWs after IRB adoption is significantly stronger. Using the German data, Behn et al. obtained similar results [45]. They compare the PDs of loans under IRB and those waiting for supervisory validation of IRB. They found that the estimated PD associated with the same borrower at the same point in time is significantly lower in the case of a bank already using IRB than in the case of a bank under the IRB validation procedure. At the same time, the lower PDs of IRB banks on an aggregate level were associated with higher actual loan losses, which is in contrast to the original objective of risk-based regulation, namely to ensure greater capital is required for higher risk taking. The authors explain the results by stating that it is in the interest of banks to save regulatory capital, which in turn incentivizes them to underestimate PDs.

The work conducted by the EBA and other regulators may be able to limit the banks’ ability to preserve their own self-interest through innovative use of risk management models. However, banks have always had and will always have more resources for model development than regulators, since it is in their private interest to do so. As with programmers and hackers, or safe makers and burglars, the banks’ modeling experts and the regulators are always in close competition to understand the other’s intentions and stay one step ahead. That is why risk-based regulation in itself cannot sufficiently serve the public interest of financial stability, even if model adequacy risk were to be fully eliminated, which is unthinkable. Consequently, it is necessary to incorporate non-risk-sensitive items into the regulatory tool-kit to limit private interest.

Integrating risk-based and non-risk-sensitive regulatory tools after the GFC

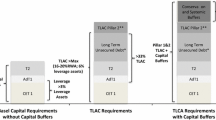

In 2017 the BCBS summarized the need for Basel III as follows: ‘… incentives exist to minimize risk weights when internal models are used to set minimum capital requirements [47 p.1]. In addition, certain types of asset, such as low-default exposures, cannot be modeled reliably or robustly. The reforms introduce constraints on the estimates banks make when they use their internal models for regulatory capital purposes, and, in some cases, remove the use of internal models.’ In relation to credit risk capital requirements, the Basel III regulation introduces three types of constraints (1) unweighted leverage ratio; (2) floors both for inputs and the outputs of the models; and (3) restrictions on the use of IRB methods for some asset classes. In the following, we analyze these three tools and attempt to answer the question of whether they can sufficiently increase banks’ loss-absorbing capacity and how they change the incentive structure of regulation.

Leverage ratio requirement

The excessive leverage built up by the banks was among the most important contributors to bank vulnerability in the run up to the GFC. As Acharya and Schnabi show, the main reason for the high degree of leverage was securitization-related regulatory arbitrage both in the form of the sale of loans to investors and of the purchase of AAA-rated CDO and CLO tranches in preference to lending [48]. They refer to these phenomena as the ‘leverage game,’ which is in truth the permanent game played between the regulators and the regulated institutions. It is not the concrete methods of pre-crisis arbitrage that are the most interesting in themselves as the innovation of increasingly sophisticated regulatory arbitrage techniques is among the inherent incentives to bankers. Within a risk-based regulatory framework, innovating products with risk weighting that is underestimated according to the prevailing regulation will, by definition, result in an increased return on equity for bank owners and increased remuneration for senior management. In order to counter regulatory arbitrage, Acharya and Schnabi suggest that a mix of indicators should be used for the purposes of regulatory assessment [48]. In Europe, where securitization was much less developed than in the US, an additional special reason for excessive leveraging emerged due to the zero sovereign risk weight within the Euro area, which incentivized European banks to buy and hold high quantities of high-risk euro-denominated sovereign bonds, for example, those issued by the Greek government.

Admati also stresses that the regulatory arbitrage inherent in a risk weighting system—in combination with low equity requirements—can result in extraordinary high degrees of leverage. She determines three factors of easy regulatory arbitrage: the ignorance of tail risk of internal models; the ability of banks to manipulate regulatory capital requirements in the IRB framework; and the preferential treatment of some exposures by regulators, such as lending to sovereigns [40]. Since banks are interested in high returns and not in financial stability, Admati and Hellwig suggest a 30% unweighted equity requirement to counterbalance the incentive to build up high leverage [42]. Of this, 20% is the minimum regulatory capital and 10% is a buffer rate contributed from retained earnings, similarly to the Basel III capital conservation buffer.

The Basel III regulatory framework recognized the deficiencies of risk weighting and set a leverage requirement as a supplementary regulatory tool. However, this requirement is much lower than that suggested by Admati and Hellwig at only 3% of non-risk weighted (on- and off-balance sheet) assets. Moreover, the capital measure of the Basel III leverage ratio is Tier 1 capital, also including additional Tier 1 items, rather than the more stringent Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital, that is roughly equivalent to equity.[49]. The final version of Basel III amended this with an additional leverage ratio buffer for the G-SIBs.Footnote 2 [50]. The extra G-SIB leverage ratio buffer requirement is equal to 50% of the risk-based G-SIB capital buffer requirementFootnote 3 of the related banks and must be implemented only by 2022 [51]. In its present form, the leverage regulation allows non-G-SIB banks to build up assets 33.3 times higher than their Tier 1 capital, i.e., 44.33 times higher than their equity (the CET1 capital), which is without doubt inefficient to offset the incentive for regulatory arbitrage. According to the list of Financial Stability Board for 2019, the risk-based capital buffer requirement is 1% for 18 out of 30 G-SIB banks, which means a total leverage requirement of 3.5% instead of 3%, i.e., those banks can have assets 28.57 times higher than their Tier 1 capital and 38 times their equity [53]. The highest leverage requirements in 2019 related only to the largest G-SIB, the JP Morgan Chase. In line with its 2.5% risk-based G-SIB capital buffer requirement, JP Morgan Chase is required to meet a leverage limit of 4.25%, i.e., it can have 23.5 times higher assets than its Tier 1 capital, which is 31.3 times higher than its equity. That is, the continuing dominance of the risk-based approach of Basel III can also be seen in the low level of the leverage ratio, which only slightly limits the use of debt in funding banks, and accordingly contributes to the continuation of the dominance of private interest.

Capital floors

To counterbalance the potential unintended general decrease in the level of banking capital due to modeling results and the differences in modeling practices, even Basel II introduced an output floor regulation, which was originally intended to be temporary. For banks using the IRB approach to credit risk measurement, the capital floor was 80% of the Basel I capital requirements. In the wake of the global financial crisis, the Basel Committee decided to permanently keep this floor regulation in place.[54]. Floor regulation is a tool to restrict the concept of risk-based regulation and partially preserve the non-risk-sensitive nature of regulation. The 2014 Consultative document of BCBS included suggestion on redesigning the system of capital floors in order to legitimize its permanent nature [49]. Moreover, alongside these output floors, BCBS issued another consultative document in 2016 on parameter floors in the IRB approach, i.e., on input floors [55]. The final version of the regulation introduced a 72.5% output floor, that is the IRB capital requirement is the higher of the IRB model result and the 72.5% of the capital requirement calculated by the new standardized approach, as well as input floors for PDs used as IRB risk parameters [50]. There is a long phase-in period for the output floors, they will be valid only from January 2023.Footnote 4 The permanent use of floors represents a significant step back from risk-based regulation toward less risk-sensitive regulation.

The concept of permanent floors, and of output floors that restrict use of the models’ results for capital calculation in particular, was hotly debated.Footnote 5 The issue of floors was so important to banks and to some national regulators that opinions in opposition to their use were widely published in the specialist media and on the banks’ own websites.Footnote 6 Deutsche Bank even argued that the introduction of floors ‘…could bring us back to the start’Footnote 7 (i.e., to the highly criticized Basel I regulation with its simple risk weighting and without the IRB approach), while, in the view of the European Banking Federation, the output floor ‘would become the major prudential constraint to finance and economic growth in the EU.’ [52].

To analyze the real impact of BCBS floor regulation, the European Parliament organized a public hearing and commissioned three papers in advance of the event with the Chair of the Single Supervision Mechanism in Economic and Monetary Affairs Committee of the European Parliament on November 9, 2016. All three papers have the same title: ‘Banks’ internal rating models—time for change?’ with the subtitle: ‘The “system of floors” as proposed by the Basel Committee,’ but they have entirely different arguments and conclusions [36, 56, 57]. According to Resti ‘…floors provide a technically flawed answer to a real problem.’ [36 p.5]. He argues that, by improving and unifying the techniques both for modeling and model validation, the quality of risk-based regulation can be improved significantly, thereby eliminating the need for additional floors. Similarly, Haselmann and Wahrenburg also argue against output floors, since they believe floors fail to address the most important problem, i.e., that the models used by the banks are highly heterogeneous [56]. They also argue that the leverage ratio is an effective backstop to complement the risk-based results of IRB models, and that there is therefore no need for a further backstop in the form of an output floor. However, they accept input floors for PDs in IRB models in cases of scarce default data to counterbalance the exaggerated optimism of banks and to help the convergence of modeling practices. Huizinga takes a different view, he looks at the output floor not as something that acts against risk management efficiency and development, but as a tool against undercapitalization due to the manipulation of RWs by banks. Additionally, he also finds input floors useful, since they can serve to decrease the effects of mismeasurement of risk parameters [57]. All in all, despite the controversial assessments of floors, it seems that the more effective the floors are, the more they are able to act against the private interest of banks to manipulate RWs. The floors have to be high enough to be effective, but low enough to maintain the incentive to develop risk management practices. The 72.5% floor level, which allows a 28.5% capital reduction when compared with the new standardized approach, lends significant scope for the reduction of capital requirements through investment in risk management. However, no precise explanation is given as to why exactly the 28.5% capital saving is appropriate, and why 20% or 10% is insufficient for this purpose, for example.

Restrictions on the use of IRB models

The idea of IRB restrictions was the last item of the non-risk-sensitive regulatory tools that the BCBS raised for consultation. The formulation of IRB restrictions during its consultation period also shows the strong lobbying power of banks. In its original consultative document, the Basel Committee proposed to fully remove the IRB option for financial institutions and large corporationsFootnote 8 and to allow the use of the Foundation IRB option only for large, but not excessively largeFootnote 9 corporates [37]. The proposals were based on the recognition of extremely high model accuracy risk related to low-default portfolios. The industry representatives strongly opposed the suggestionFootnote 10 on the grounds of a lack of risk sensitivity, increased reliance on credit rating agencies and increased capital requirements. They also argued that the proposed leverage and floor regulation also aim to be backstops for model risks, without analyzing the interaction between them. Instead, industry experts proposed to progress further toward better and more harmonized modeling and model implementation practices. The final version of Basel III is much more in line with the banks’ interests; it removes only the Advanced IRB option for banks, other financial institutions and large corporates,Footnote 11 but allows use of Foundation IRB, and the IRB option was only fully removed for equity exposure.

There is another potential tool that would have been incorporated into the post-GFC regulatory system to increase regulatory capital requirements, namely an increase in the 1.06 scaling factor of IRB function. The use of a scaling factor is similar to output floors in the sense that both increase the required level of capital above the model-based threshold. However, there is a significant difference. Since the scaling factor would preserve the model-based value as the basis for capital calculation, it would not change the risk-based nature of regulation and therefore the incentive structure of the IRB. On the positive side, it would incentivize model development and therefore better risk measurement and management. Meanwhile on the negative side, it also would stabilize the adverse incentive structure of the present system. The finalized version of Basel III with regard to the new output floor removed the scaling factor from the calculation of the RWA for IRB banks. While the debate on floors was extensive and public, the removal of the scaling factor was not widely and publicly debated. This also illustrates the strong lobbying power of banks: the capital increase of IRB banks caused by the leverage and output floor is partly counterbalanced by the 6% capital decrease due to the last-minute removal of the scaling factor.

Conclusions

The development of bank capital regulation shows a clear pattern of moving from less risk-sensitive to risk-based regulation before the GFC, and from risk-based toward mixed non-risk-sensitive and risk-based regulation in the wake of it. Complementing risk-based regulation with non-risk-sensitive items aims to mitigate the shortcomings of risk-based regulation that became apparent during the crisis. This article analyzes both reversals in relation to the regulatory approach to credit risk capital requirements.

Taking an overview of IRB-related risks, we made a clear distinction between two types of model risk: model adequacy risk and model accuracy and implementation risk. This is important to our analysis since model adequacy risk cannot be mitigated by better modeling. Moreover, while model accuracy and implementation risk can be significantly improved by more advanced modeling techniques, through the creation of more precise and detailed modeling guidelines and the development of more uniform supervisory validation techniques, the underlying incentive structures work against the mitigation, since the private interest of banks is to increase their returns, irrespective of the regulatory regime. The main motivation for banks’ investment in risk management is to be able to maximize their risk-adjusted return on equity. As a result, the pre-crisis switch from less risk-sensitive to risk-based regulation has produced a one-step-forward-one-step-backward situation. It has mitigated the problems of less risk-sensitive regulation but has created new and no less important issues. Moreover, until the emergence of the global financial crisis, the spectacular development of banking risk management practices was able to feed the illusion that regulatory capital is increasingly proportional to banking risk, making them equipped to preserve both financial stability and depositors’ money. Developing the IRB models can genuinely result in more developed risk awareness, better risk management and more consistent model implementation, which is useful for all market participants and contributes to banking stability in crisis-free times. However, in line with the Goodhart Law, as model-based regulation (risk measurement) becomes a regulatory standard, it ceases to be a good measure.

Analyzing the three non-risk-based supplementary items of Basel III regulation, namely the leverage ratio, the capital floor regulation and the restrictions to IRB use, we have shown how effective they are and how the regulatory techniques change—or do not change—the incentive structure of regulation. We have found that leverage regulation is a good complementary tool to counterbalance the adverse incentives of risk weighting and increase the general level of capital requirements. However, as its 3% level is very low, it is unlikely to help change the incentive structure of regulation and significantly increase the capital level. Similarly, the IRB output floor gives less scope for IRB parameter manipulation while simultaneously decreasing the incentive for advanced risk management techniques. It can also contribute to a reduction in the incentive for those financial innovations designed to decrease the RWA. The 72.5% level appears to be low enough to allow banks to maintain their interest in model development, but it is highly questionable that the limit is sufficiently high to be effective. The IRB restrictions in their present form, which largely apply only to the use of the advanced IRB approach for high-default portfolios, seem to be the result of a series of serious compromises and will have limited impact on both the effectiveness and the incentive structure of the regulation.

The main conclusion of our analysis is that a mixed regulatory system that incorporates both risk-based and non-risk-sensitive items is superior to either purely non-risk-sensitive or purely risk-based regulation. A mixed system can help mitigate the negative incentives of both non-risk-sensitive and risk-based regulations, or at least make regulatory arbitrage less straightforward, since the two systems have different incentive structures. However, the present system has become so complex that it is very difficult to follow, and, in accordance with this, the underlying incentive structures also remain unknown, which may result in several unknown side-effects to Basel III. Our analysis also stresses that the choice between non-risk-sensitive and risk-based regulation, or the choice of a mixture of the two, cannot be restricted to a technical question of risk management. It is at least as much an issue of politics as one of economic modeling. That is why arguments focusing only on developing models and harmonizing implementation, i.e., those that relate only to model accuracy and implementation risk and see the future of regulation solely in better modeling, are highly misleading.

Notes

Directives 2006/48EC and 2006/49EC.

Globally Systemically Important Banks, i.e., the 29 largest internationally active banks worldwide.

To increase the loss absorbing capacity of globally active large banks, G-SIBs are required to hold a special capital buffer on the top of the general capital requirements. The size of the buffer requirement is between 1% and 3.5% of the RWA depending on the level of systemic importance of a G-SIB (BCBS 2018).

Originally the introduction of the output floor was planned to January 2022 with transitional arrangements to January 2027. To respond to COVID the implementation date was revised and postponed to January 2023 with transitional arrangements to January 2028.

Comments sent to BCBS are available at: https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/comments/d306/overview.htm

Corporate group members, where the group’s consolidated total revenue is above EUR 50 billion.

Corporate group members, where the group’s consolidated total revenue is between EUR 200 million and EUR50 billion.

Comments sent to the BCBS available at: https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/comments/d362/overview.htm

Corporate group members, where the group’s consolidated total revenue is above EUR 500 million.

References

Black J (2005) The emergence of risk-based regulation and the new public risk management in the United Kingdom. Public Law (Autumn)pp. 512–549

Black, J., and R. Baldwin. 2010. Really responsive risk-based regulation. Law & Policy 32 (2): 181–213.

Black, J., and R. Baldwin. 2012. When risk-based regulation aims low: Approaches and challenges. Regulation & Governance 6 (1): 2–22.

Black, J. 2010. Risk-based regulation: Choices, practices and lessons to be learned. In Risk and Regulatory policy, 185–236. OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform: Improving the governance of risk.

Danielson, J. 2003. On the feasibility of risk based regulation. CESifo Economic Studies, CESifo 49 (2): 157–179.

BCBS (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision) (1996) Amendment to the capital accord to incorporate market risk, January

BCBS (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision) (2006) Basel II: International convergence of capital measurement and capital standards: A revised framework, June

Diamond, D., and R. Rajan. 2000. A theory of bank capital. Journal of Finance 55: 2431–2465.

Barth, J.R., G. Caprio Jr., and R. Levine. 2006. Rethinking Bank Regulation. Till Angels Govern: Cambridge University Press.

Barth, J.R., Prabha, A.P. and Lu, W. (2013) Do interest groups unduly influence bank regulation? CESifo DICE Report, 4/2013

Cook, P. 1990. International convergence of capital adequacy measurement and standards. In The Future of Financial Systems and Services, ed. E. Gardner. New York: Macmillian.

Tarullo, D.K. 2008. Banking on Basel. Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Jones, D.S., and J. Mingo. 1998. Industry practices in credit risk modeling and internal capital allocations: Implications for a models-based regulatory capital standard: summary of presentation. Economic Policy Review 4 (3): 53–60.

BCBS (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision) (1999/a) Capital Requirements and bank behavior: the impact of the Basel Accord, Working Paper No.1. April

Sheldon G. (1996) Capital adequacy rules and the risk-seeking behavior of banks: A firm-level analysis. Swiss Journal of Economics and Statistics (SJES), Swiss Society of Economics and Statistics (SSES) 132(IV): 709–734.

Gordy, M. B. (1998) A Comparative Anatomy of Credit Risk Models ; Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System FEDS Paper No. 98–47.

BCBS (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision) (1999/b) Credit risk modelling: Current practices and applications, April

BCBS (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision) (1999/c) A new capital adequacy framework, Consultative Paper, June

BCBS (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision) (2001) The New Basel capital accord: an explanatory note, January

BCBS (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision) (2005) An explanatory Note on Basel II IRB Risk Weight Functions, July

Lindquist, K-G. (2003): Banks’ buffer capital: How important is risk?. Norges Bank Working Paper, 2003/11

Ayuso, J., D. Pérez, and J. Saurina. 2004. Are capital buffers pro-cyclical? Evidence from Spanish panel data. Journal of Financial Intermediation 13: 249–264.

Gambacorta, L. and Mistrulli, P. E. (2003): Bank capital and lending behavior: empirical evidence for Italy. Banca d’Italia Termi di discussione (Economic Working Papers) No. 486

Catarineu-Rabell, E., Jackson, P. and Tsomocos, D.P. Procyclicality and the new Basel Accord – Banks’ choise of loan rating system. Bank of England Working Paper, No.181, 2003.

Danielsson, J. et al (2001) An Academic Response to Basel II, FMG Special Paper, No. 130, May

Segoviano, M.A. and Lowe, P. (2002) Internal ratings, the business cycle and capital requirements: some evidence from an emerging market economy. BIS Working Papers, No. 117.

Danielsson, J. and Shin, H.S. (2003) Endogenous Risk, In: Modern Risk Management - a History, Risk Books, pp. 297–313.

Griffith-Jones, S., and S. Spratt. 2003. The Pro-Cyclical Effect of the New Basel Accord. Institute of Development Studies: University of Sussex, Brighton.

Goodhart, C., B. Hofmann, and M. Segoviano. 2004. Bank Regulation and Macroeconomic Fluctiations. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 20 (4): 591–615.

Király, J., and K. Mérő. 2004. Basel Scepticism: From a Hungarian Perspective. In The New Basel Capital Accord, ed. B.E. Gup, 337–369. Toronto: Thomson.

Danielsson, J. 2008. Blame the Models. Journal of Financial Stability 4 (4): 321–328.

Greenspan, A. (2008) We will never have a perfect model of risk, Financial Times, March 17.

Knight, F.H. (1921) Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit. Reprint of Economic Classics, August M. Kelley Bookseller, 1964, New York

EBA (European Banking Authority) (2015) Future of the IRB Approach, Discussion Paper, EBA/DP/2015/01

EBA (European Banking Authority) (2016) The EBA’s regulatory review of the IRB approach - Conclusions from the consultation on the Discussion Paper on the future of IRB approach

Resti, A. (2016) Banks' internal rating models - time for a change? The "system of floors" as proposed by the Basel Committee. European Parliament, November

BCBS (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision) (2016/a) Regulatory consistency assessment programme (RCAP) – Analysis of risk-weighted assets for credit risk in the banking book. April

EBA (European Banking Authority) (2017/a) EBA Report on IRB modelling practices, November

EBA (European Banking Authority) (2017/b) Results from the 2017 low default portfolios (LDP) exercise, EBA Report, November

Admati, A. (2016) The missed opportunity and challenge of capital regulation. National Institute Economic Review No. 235 February

Hellwig, M. (2010) Capital Regulation after the Crisis: Business as Usual? Preprints of the Max Planck Institute for Research on Collective Goods, Bonn 2010/31

Admati, A., and M. Hellwig. 2013. The Bankers’ New Clothes: What’s Wrong with Banking and What to Do About it. Princeton University Press.

Acharya, V., R. Engle, and D. Pierret. 2014. Testing macroprudential stress tests: The risk of regulatory risk weights. Journal of Monetary Economics 65: 36–53.

Mariathasan, M., and O. Merrouche. 2014. The manipulation of Basel risk-weights. Journal of Financial Intermediation 23: 300–321.

Behn M., Haselmann R. and Vig V. (2016) The limits of model-based regulation. ECB Working Paper Series, No. 1928/July

Plosser, M. and Santos, J. (2014) Banks’ Incentives and the Quality of Internal Risk Models, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports No. 704. December

BCBS (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision) (2017/a) Finalizing Basel III – In brief

Acharya, V., and P. Schnabl. 2009. How Banks Played the Leverage Game. In Restoring Financial Stability – How to Repair a Failed System, ed. V. Acharya and M. Richardson, 83–100. Hoboken: Willey .

BCBS (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision) (2014) Capital floors: the design of a framework based on standardized approaches. Consultative Document

BCBS (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision) (2017/b) Basel III: Finalizing post-crisis reforms, December

BCBS (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision) (2018) Global systemically important banks: revised assessment methodology and the higher loss absorbency requirement, July

European Banking Federation (2016) EBF letter to the Basel Committee: Finalisation of Basel III without Output Floors. 19 December, Available at: https://www.ebf.eu/regulation-supervision/ebf-letter-to-the-basel-committee-finalisation-of-basel-iii-without-output-floors/

Financial Stability Board (2019) 2019 list of global systematically important banks (G-SIBs), November

BCBS (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision) (2009) Enhancements to Basel II framework. July

BCBS (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision) (2016/b) Reducing variation in credit risk-weighted assets: Constraints on the use of internal model approaches. March

Haselmann, R. and Wahrenburg, M. (2016) Banks' internal rating models: time for a change? The "system of floors" as proposed by the Basel Committee, European Parliament, November

Huizinga, H. (2016) Banks' internal rating models: time for a change? The ‘system of floors’ as proposed by the Basel Committee, European Parliament, November

Funding

Open access funding provided by Budapest Business School - University of Applied Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mérő, K. The ascent and descent of banks’ risk-based capital regulation. J Bank Regul 22, 308–318 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41261-021-00149-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41261-021-00149-1