Abstract

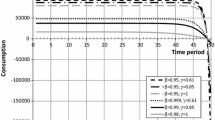

Hyperbolic utility discounting has emerged as a leading alternative to exponential discounting because it can explain time-inconsistent behaviors. Intuitively, hyperbolic discounting should play a crucial role in intergenerational models characterized by intertemporal trade-offs. In this paper, we incorporate hyperbolic discounting into a dynamic model in which parents are altruistic towards their children. Agents live for four periods and choose levels of consumption, fertility, investment in their children’s human capital, and bequests to maximize discounted utility. In the steady state, hyperbolic discounting decreases fertility, increases human capital investment, and shifts consumption towards younger ages. These effects are more pronounced in the time-consistent problem (in which agents cannot commit to a course of action) than in the commitment problem, which can be interpreted as realized and intended actions, respectively. The preference-based discrepancy between intended fertility and realized fertility has important implications for the empirical literature that compares the two.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It is relatively easier to place the education decision after the fertility decision is a static model, such as that in Nakagawa et al. (forthcoming).

References

Adsera A (2006) An economic analysis of the gap between desired and actual fertility: the case of Spain. Rev Econ Household 4:75–95

Bachrach CA, Morgan SP (2013) A cognitive–social model of fertility intentions. Popul Dev Rev 39(3):459–485

Beaujouan E, Berghammer C (2019) The gap between lifetime fertility intentions and completed fertility in Europe and the United States: a cohort approach. Popul Res Policy Rev 38(4):507–535

Becker GS, Barro RJ (1988) A reformulation of the economic theory of fertility. Q J Econ 103(1):1–25

Becker GS, Lewis HG (1973) On the interaction between the quantity and quality of children. J Polit Econ 81(2):S279–S288

Cao D, Werning I (2018) Saving and dissaving with hyperbolic discounting. Econometrica 86(3):805–857

Diamond P, Köszegi B (2003) Quasi-hyperbolic discounting and retirement. J Public Econ 87(9-10):1839–1872

Doepke M, Tertilt M (2018) Women’s empowerment, the gender gap in desired fertility, and fertility outcomes in developing countries. AEA Papers and Proceedings 108:358–362

Frederick S, Loewenstein G, O’donoghue T (2002) Time discounting and time preference: a critical review. J Econ Lit 40(2):351–401

Galor O, Zeira J (1993) Income distribution and macroeconomics. Rev Econ Stud 60(1):35–52

Gruber J, Köszegi B (2001) Is addiction “rational”? theory and evidence. Q J Econ 116(4):1261–1303

Günther I, Harttgen K (2016) Desired fertility and number of children born across time and space. Demography 53(1):55–83

Ikeda S, Kang MI, Ohtake F (2010) Hyperbolic discounting, the sign effect, and the body mass index. J Health Econ 29(2):268–284

Jones LE, Schoonbroodt A, Tertilt M (2010) Fertility theory: can they explain the negative fertility-income relationship? In: Shoven J (ed) Demography and the economy. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 43–100

Laibson D (1997) Golden eggs and hyperbolic discounting. Q J Econ 112(2):443–478

Nakagawa M, Oura A, Sugimoto Y (forthcoming) Under- and over-investment in education: the role of locked-in fertility. J Popul Econ

O’Donoghue T, Rabin M (1999) Doing it now or later. Am Econ Rev 89(1):103–124

Phelps ES, Pollak RA (1968) On second-best national saving and game-equilibrium growth. Rev Econ Stud 35(2):185–199

Pritchett (1994) Desired fertility and the impact of population policies. Popul Dev Rev 20(1):1–55

Samuelson PA (1937) A note on measurement of utility. Rev Econ Stud 4(2):155–161

Thomson E, McDonald E, Bumpass LL (1990) Fertility desires and fertility: hers, his, and theirs. Demography 27(4):579–588

van der Pol M, Cairns J (2002) A comparison of the discounted utility model and hyperbolic discounting models in the case of social and private intertemporal preferences for health. J Econ Behav Organ 49(1):79–96

Wang M, Rieger MO, Hens T (2016) How time preferences differ: evidence from 53 countries. J Econ Psychol 52:115–135

Wigniolle B (2013) Fertility in the absence of self-control. Math Soc Sci 66(1):71–86

Wrede M (2011) Hyperbolic discounting and fertility. J Popul Econ 24(3):1053–1070

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the editor, Alessandro Cigno, and three anonymous reviewers for their important comments. We also want to thank Otávio Bartalotti, Elizabeth Hoffman, Joshua Rosenbloom, Sunanda Roy, Quinn Weninger, John Winters, Wendong Zhang, and participants in the Graduate Students Seminar at Iowa State University for helpful comments. We thank Bryan Jackson for proofreading the manuscript. The authors are responsible for all remaining errors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Responsible editor: Alessandro Cigno

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Appendix 1. The proof of Proposition 1

Proof. Let λ be the Lagrangian multiplier associated with the budget constraint. Optimal consumption choices satisfy

The optimal human capital investment, fertility, and bequest conditions read

From the Envelope Theorem (ET thereafter), we have

In the steady state, the equation above and the bequest condition decide fertility

1.2 Appendix 2. The proof of Proposition 2

We use backward induction to solve the time-consistent problem: first, Self 3 chooses c3 and b′ given e′, a3 and n; then, Self 2 chooses c2, n, e′, and a3 given a2; at last, Self 1 chooses c1 and a2 given e and b. The three problems are described as follows.

Self 3 solves the following maximization problem:

subject to

The solutions to Self 1’s problem are denoted by \( {c}_3={c}_3^t\left({e}^{\prime },{a}_3,n\right),b={b}^t\left({e}^{\prime },{a}_3,n\right) \).

Self 2 solves the following maximization problem:

subject to

The solutions to Self 2’s problem are denoted by \( {c}_2={c}_2^t\left(e,{a}_2\right),{a}_3={a}_3^t\left(e,{a}_2\right),n={n}^t\left(e,{a}_2\right) \).

Self 1 solves the following maximization problem:

subject to

The solution to Self 1’s problem is denoted by \( {c}_1={c}_1^t\left(e,b\right),{a}_2={a}_2^t\left(e,b\right) \).

Self 3’s first-order condition (FOC thereafter) with respect to bequests is

Self 3’s ET conditions are

Self 2’s FOCs with respect to e′, a3, n are

Self 2’s ET conditions are

Self 1’s FOC with respect to a2 and ET conditions read

From the FOCs and ET conditions with respect to a2 and a3, we have the following equation to describe consumption:

In the steady state, we also have

Combining the two equations above to eliminate consumption, we have

1.3 Appendix 3. The proof of Proposition 3

In the commitment problem, combining the FOC and ET conditions with respect to human capital from A1 and using the fact that \( {V}_1^c\left(e,b\right)={V}_1^c\left(e^{\prime },b^{\prime}\right) \) in the steady state, we have

Rearranging the equation and using the result of Proposition 1, we have

In the time-consistent problem, combining Self 2’s FOC and all three ET conditions with respect to education,

Plugging Eq. (8) into the equation above to eliminate consumption and using the result of Proposition 2, we have

1.4 Appendix 4. The proof of Proposition 4

In both the commitment problem and the time-consistent problem, a reduction in β will lead to an increase in Φ(n)/n, and therefore will reduce n because Φ(n) is strictly increasing and concave. Hyperbolic discounting means that β < 1. So, the existence of hyperbolic discounting will reduce fertility in the steady states of both problems. From Eq. (7), we can see a negative relationship between fertility and human capital. Consequently, the existence of hyperbolic discounting will increase the steady-state human capital in both problems.

Dividing Eq. (6) by Eq. (5), we have

Combining Eq. (7) with the inequality above, we have

When β = 1, we have an exponential discounting problem with solutions ne and ee satisfying \( {\delta}^2{R}^2\frac{\varPhi \left({n}^e\right)}{n^e}=1 \) and \( \left[\frac{1}{R}+\frac{\left(1+g\right)\left(1-{n}^ex\right)}{R^2}\right]h^{\prime}\left({e}^e\right)=1 \). So, we have

Similarly, we have ec > ee.

1.5 Appendix 5. The proof of Proposition 5

From Appendix 4, we have \( \beta \frac{\varPhi \left({n}^t\right)}{n^t}=\frac{\varPhi \left({n}^c\right)}{n^c} \). Plugging \( \varPhi (n)=\frac{n^{1-\epsilon }}{1-\epsilon } \) into the equation, we have \( {n}^t={n}^c{\beta}^{\frac{1}{\epsilon }} \) which can be used to estimate \( {\beta}^{\frac{1}{\epsilon }} \) as a whole coefficient with nt and nc. Taking logs on both sides, we have \( \log \left({n}^t\right)=\log \left({n}^c\right)+\frac{1}{\epsilon}\log \left(\beta \right) \) which can be used to estimate β with nt, nc, and ϵ, or be used to estimate ϵ with nt, nc, and β.

1.6 Appendix 6. The proof of Proposition 6

Define \( \theta (c)=\frac{u^{\prime }(c)c}{u(c)},\theta (n)=\frac{\varPhi^{\prime }(n)n}{\varPhi (n)} \). From Eq. (8) and the budget constraint (4), the steady-state consumption in three periods in the commitment problem can be expressed as

where α1, α2, α3 are defined as in Proposition 6. \( {I}^c={c}_1^c+\frac{c_2^c}{R}+\frac{c_3^c}{R^2} \). We need to show the specific form of Ic. For simplicity, I will not show the superscript “c” until the end of the proof. Substituting the three equations above into Eq. (1), the maximization problem becomes

We have three new FOCs, which are given as follows:

From the first two FOCs, we have

From the third FOC, we have

Rearranging the equation above with the definition of θ(c) and θ(n),

Using Eq. (10) to rewrite the budget constraint (4),

Combining the two equations above, we have

Rewriting the third FOC to the previous period and using the fact that it’s in steady state, we have

Rewriting the equation above, we have

Substituting (14) and (15) into (11), we can get the expression for c1 in the steady state,

Combining (12) and (16), we have the steady-state bequest expression

We can see that it is the elasticities of the utility and altruism functions that matter. If utility and altruism functions show constant elasticities of substitution, their specific function forms will not influence the consumption and bequests in the steady state.

Plugging the specific functions into (16) and (17), we can get the specific form of Ic and an equation in which bequests are determined.

1.7 Appendix 7. The proof of Proposition 7

From Eq. (21) and the budget constraint,

where μ1, μ2, μ3 are defined as in Proposition 7. \( {I}^t={c}_1^t+\frac{c_2^t}{R}+\frac{c_3^t}{R^2} \). The rest of the proof is similar to that of Proposition 6.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cao, J., Li, M. Hyperbolic discounting in an intergenerational model with altruistic parents. J Popul Econ 35, 989–1005 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-021-00824-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-021-00824-7